Data Integration, Sharing, and Management for Transportation Planning and Traffic Operations (2025)

Chapter: 15 Opportunities and Challenges in Improving the Use of Data in Integrated Corridor Management Systems

CHAPTER 15

Opportunities and Challenges in Improving the Use of Data in Integrated Corridor Management Systems

Introduction

During the initial phase of NCHRP Project 08-119, integrated corridor management (ICM) was identified as an area where agencies could benefit from guidance on data sharing, integration, and management practices. It was also evident that the capabilities of data management systems have changed significantly since the rollout of the U.S. DOT Integrated Corridor Management Initiative in 2006.

Analysis revealed that since the U.S. DOT ICM pilot demonstrations, and the development of several new ICM systems, the architecture for these new ICM data constructs had only been conceptualized rather than fully designed. By the time the pilots began, the budget would have needed to be significantly expanded to develop these architectures after the fact. As ICM systems were built, more and more unanticipated costs and complexities resulted from the merging and integration of the multitude and sheer quantity of data types and sets in these corridors. The center-to-center (C2C) communications and required infrastructure, which utilized standards, were less challenging than the data themselves. At the core of these C2C interfaces are institutional agreements and memoranda of understanding (MOUs) that are established in conformance with regional Transportation Systems Management and Operations (TSMO) plans (Hardesty and Hatcher 2019).

Standardization did not address all the integration issues that system builders faced. For example, as revealed in an earlier phase of the project, in which the research team interviewed an integrator for the San Diego I-15 ICM Demonstration project, the ICM utilized the Traffic Management Data Dictionary (TMDD) standards, but several customized add-ons were developed that were not addressed by the standards. This was due to the introduction of new types of data exchanges with new products that the TMDD did not address. The standard, at face value, was an essential starting point, but customization was necessary to meet the needs of the project (Miller et al. 2008).

Many ICM systems have been limited to the integration and use of more traditional intelligent transportation system (ITS) elements, but there has been a strong desire to integrate new mobility data sources such as electric scooters and bicycles into the next generation of ICM deployments.

Overall, the challenges identified in the initial phase of the NCHRP 08-119 research were as follows:

- Systems are conceptualized without consideration of data architecture and computational needs for data fusion.

- Agencies are concerned (and fearful) of security challenges with field communications networks, cloud storage, integration with other agencies, and data retrieval.

- The development of an open-source data system that intends to utilize raw data is more difficult to realize when the sources of such data have commercial interests in retaining raw data. Instead, they offer “cleaned” data as a part of their service offering.

- Traveler behaviors (such as mode shift from personal vehicle to transit) are difficult to change dynamically through information and data.

Furthermore, the research team identified several key data needs for consideration as potential future focal areas of study:

- Real-time transit passenger counts, which are essential to understanding the volume and capacity of a facility or segment of roadway;

- Data fusion guidelines, which tend to be customized by corridor;

- Decision support systems standards or guidance;

- Formalization of agreements or MOUs, which are essential to ICM success; and

- Integration of new mobility data sources.

The following sources were referenced during the initial phase of research:

- Integrated Corridor Management: Implementation Guide and Lessons Learned (Blake et al. 2015);

- Final Report: Dallas Integrated Corridor Management (ICM) Demonstration Project (Miller et al. 2015);

- Advances in Strategies for Implementing Integrated Corridor Management (ICM) (Spiller et al. 2014);

- System Requirement Specification for the I-15 Integrated Corridor Management System (ICMS) in San Diego, California (San Diego, CA, Pioneer Site Team 2008); and

- Data Hub (UC Berkeley 2020).

On the basis of the initial ICM review, the team identified a potential opportunity to conduct a pilot study through LA Metro and Caltrans District 7. The goal of this pilot was to explore the challenges and demonstrate the integration of transit ridership data into the ICM being developed along I-405 at the Sepulveda Pass. Bus occupancy data, schedule information, and automatic vehicle location (AVL) data would be integrated to establish an improved flow of transit system information on the corridor. However, while the pilot concept showed promise, the available transit data were not useful. Data from the transit agencies could only provide aggregated passenger counts in two bins: weekdays and weekends. No data on the hour-by-hour passenger counts were available, as might be collected on the transit vehicle.

Consequently, the team developed this chapter to identify the opportunities and challenges regarding the use of data on ICM deployments, based on a review of recent literature and interviews with two agencies that recently completed ICM deployments. This chapter is recommended for transportation system managers and agencies currently operating existing or exploring new ICM systems to better understand the data architecture and management considerations of peer agencies.

Research Approach

The team focused the research on documentation produced since 2019, as many of the recommendations prior to this date had become outdated. The emphasis of the review was on effective practices in the management and use of data for ICM deployments. The team conducted telephone interviews with a few personnel involved directly with the I-24 SMART Corridor [Tennessee Department of Transportation (TDOT)] and the I-76 ICM [Pennsylvania Department of Transportation (PennDOT)].

Organization

The remainder of this chapter is organized as follows:

- The “Information Gathering” section summarizes key findings from the literature review and agency interviews.

- The “Recommendations” section provides insights on common challenges and recommended approaches to improve data management and use for ICM deployments.

The references cited are listed at the end of the chapter.

Information Gathering

This section of the paper includes summaries of relevant recent literature and of interviews conducted with two agencies implementing ICM systems.

Literature Review

The following three reports were reviewed:

- Integrated Corridor Management (ICM) Program: Major Achievements, Key Findings, and Outlook (Hardesty and Hatcher 2019);

- Mainstreaming Integrated Corridor Management: An Executive Level Primer (Hatcher et al. 2019); and

- Build Smart, Build Steady: Winning Strategies for Building Integrated Corridor Management Over Time (Wunderlich and Vasudevan 2019).

Each of these reports is described in more detail in the following subsections.

Integrated Corridor Management (ICM) Program: Major Achievements, Key Findings, and Outlook

This report by Hardesty and Hatcher (2019) reviews the progress of the two pioneer ICM sites for the U.S. DOT’s ICM Initiative (I-15 in San Diego, CA, and US-75 in Dallas, TX) as well as 13 other sites that received planning grants around 2015. Both pioneer deployments included the integration of a decision support system (DSS). A DSS collects and synthesizes data inputs to detect anomalies in traffic patterns, develop recommended response plans, and communicate with operators and responders on the basis of the data and a set of predefined business rules and information flows. A DSS can have varying levels of complexity and automation, depending on the application.

The key findings that emerged from the evaluation of the pioneer sites include the following data-centric benefits:

- Data sharing between stakeholders significantly improved regional operational awareness of corridor congestion and incidents.

- The DSS at both pioneer sites proved to be valuable for better situational awareness, decision-making, and response coordination.

In Dallas, stakeholders discovered that there were gaps in arterial data due to outdated equipment and other systems issues. This caused discrepancies between measured speed data and actual field conditions. It is interesting to note that, after 1 year of operation, Dallas stakeholders abandoned the use of the DSS, as they had already learned the system’s approach to response plans and felt that minor incremental revisions to the data model were not necessary. They determined that the benefit was not worth the cost of the DSS and that they could better address decision

support through human intervention. In this case, funding of the DSS was not considered cost effective. The Dallas team has been able to maintain effective management of the corridor without the need for a dedicated ICM technician.

As of the publication of the report in 2019, Dallas’s data management system, EcoTraffic, was still in operation and fused traffic and other data from nearly 30 agencies along the corridor. EcoTraffic has expanded throughout the region by leveraging the statewide 511 platform. The information learned from the DSS informs the current, manual, real-time operations on response plans at each of the agencies and provides improved regional situational awareness for participating agencies. One of the key positive takeaways from the pilot program was the improved coordination between the various stakeholders that the implementation of the ICM provided.

Conversely, the DSS in San Diego offered automated implementation of the response plan across jurisdictional boundaries, which included schemes such as ramp metering control and signal system timing changes on arterials. The system was able to predict the impact of the proposed response plans with the aid of a traffic simulation tool. On the basis of the desired thresholds, the system was able to automatically select the best response plans. As with the Dallas implementation, interagency coordination in San Diego was greatly improved by virtue of implementing the ICM.

Common feedback from each of the ICM sites reviewed was that there were significant gaps in the availability of before-and-after data because of the infrequent nature of large-scale events necessitating a detour or mode shift. Comments also indicated a challenge in being able to discern whether perceived benefits were due to ICM implementation or other concurrent incident response or infrastructure improvements. Additionally, system operators reported that their real-time situational awareness of corridor operations could still be improved. Many of the pioneer sites have been successful in integrating third-party data from companies such as Waze, Inrix, and Here.

The proliferation and success of ICM could be accounted for by the recent advent of big data analysis. As ICM systems have been developed over the past decade, new data constructs, tools, and process-enabled systems such as DSS have resulted in more automated ICM deployments.

Regarding data, the report defines three recommendations for ongoing DSS improvement and research to be considered by the broader ICM industry:

- Prior to DSS development, form a corridor data sharing policy through interagency agreements. These allow agencies to define how and what data might be shared between agencies in the same way that a corridor system might indicate shared operations and maintenance responsibilities.

- Add to the TMDD standards so that they can meet ICM and DSS requirements. There is a general need for nomenclature harmonization.

- Develop guidance for how and what data can be displayed publicly versus data that are sensitive and could raise security implications.

Mainstreaming Integrated Corridor Management: An Executive-Level Primer

The successes of ICM may have been made possible in part by the mining of big data, which was not widely used at the beginning of ICM system development. Real-time and historical data are vital to developing scenarios for incident management. A traffic management center or centralized data hub makes it easier to organize and analyze the data collected to derive potential ICM strategies (Hatcher et al. 2019).

The regional ITS architecture, if available, should be referenced for any other data integration or sharing opportunities. The report further stipulates that the DSS role in ICM is to receive data from an information exchange, evaluate multiple options for response plans, and provide a recommended plan to the ICM coordinator, partner agencies, and an information exchange system. As of the date of the Primer, there were no off-the-shelf DSS, and DSS had to be developed in coordination with regional stakeholders in consideration of agency rules and data granularity and format. Optimally, a DSS should make use of historical as well as real-time data. In addition, the following considerations are key in the development and implementation of a DSS in the ICM context:

- A DSS should be developed in an incremental fashion. It is recommended that business rules be tested individually prior to being incorporated into the DSS. The incremental development of the DSS can ensure that ICM operations assume a greater level of autonomy over time.

- DSS cost and resources are key. The cost and time required for model updates and recalibration need to be incorporated into the overall project cost.

- Traffic-modeling tools need to be harmonized. If possible, the same modeling tools should be used for the DSS as are used for other efforts throughout the region.

- Consider other uses for DSS modeling enhancements. In many cases, the advanced modeling required for the operation of the DSS can have beneficial uses in other regional applications. Identifying and documenting these benefits can increase the overall impact of the ICM project and further justify the additional modeling costs.

- Get stakeholder buy-in for business rules. This will enhance the stakeholder acceptance of the ICM deployment.

- Use multimodal corridor-level performance measures from both a predictive and a retrospective viewpoint.

The Northern Virginia ICM project established a data warehouse and provides real-time and archived data on roadway operations, signals, transit, parking, bikes and pedestrians, freight, and incidents as well as probe and connected vehicle data. The data warehouse directly interfaces with the DSS, which allows for modeling of the data. Utilizing modeling, simulation, and other analysis tools is helpful in both selecting the ICM strategies to implement and testing the operational impacts of the business rules and ICM operational parameters during design and operation. The report’s discussion of funding notes that adding ICM to proposals for larger infrastructure project grants can lead to success, due to the ability of ICM-level data to better demonstrate overall project performance measures.

Build Smart, Build Steady: Winning Strategies for Building Integrated Corridor Management Over Time

This report by Wunderlich and Vasudevan (2019) stipulates that ICM systems are meant to address surges or nonrecurring events rather than day-to-day traffic (which was substantiated by TDOT staff in the team’s interview with them on their SMART Corridor project). However, corridor partners that tend to gravitate toward operating exclusively rather than wholistically continue to create challenges. Most ICM systems do not have an over-arching entity responsible for operating the corridor as one cohesive corridor. In many cases, the freeways, transit system, arterial traffic signal network, and incident response are all operated by separate entities.

Despite these challenges, success is more likely when performance and changes in demand can be identified through system monitoring. ICM is not a set-it-and-forget-it approach, and performance measures need to be evaluated on an ongoing basis to account for changes in travel demand, weather, driver behavior, data quality and availability, and other factors. Agencies are

trying to be more proactive and are considering how emerging technologies can address their evolving needs.

Wunderlich and Vasudevan’s report proposes a three-step process for stakeholders to undergo to better ensure successful ICM deployment and ongoing operations and maintenance:

- Conduct an ICM Capability Maturity Model (CMM) assessment annually. The CMM is described in detail (including examples) in Chapter 2 of the report but generally allows a stakeholder group to assess its ability to deploy ICM and identifies areas for improvement for an existing ICM. The CMM, used in conjunction with performance measures, allows for a more rational and data-driven decision-making and management process.

- Conduct regular stakeholder planning meetings to review ICM performance and identify high-priority strategic actions to move the ICM deployment forward. Chapters 3 to 5 of the report provide further discussion on how strategic planning should be facilitated at different stages of ICM implementation and complexity.

- Use the results of the first two steps to update and adapt the arrangements between ICM stakeholders.

The report identifies three arrangements that define a successful ICM: institutional, organization/operational, and technical. Under technical, data management arrangements are recommended that document agreements among stakeholders regarding data sharing, privacy, and data ownership. These data management arrangements are critical for building trust among stakeholders to engage beyond simple coordination and are essential for complex ICM strategies, which often require the ingestion and dissemination of significant data resources.

An effective practice identified was the formation of several task forces, regardless of the arrangement type, that address data needs as follows:

- Performance measurement: Use a data-driven approach to measure performance periodically and report out at ITS strategic planning meetings.

- Data sharing: Communicate required actions to the ICM corridor manager and the corridor’s software engineering and systems engineering teams.

- Investment planning: Use a data-driven approach to assess what specific enhancements (DSS, performance measurement approach, applications/strategies, data fusion) can be implemented incrementally, and when.

- Analytics: Use a data-driven approach to periodically conduct a benefit–cost analysis of competing alternatives for a no-resource-constrained scenario and a resource-constrained scenario and report out at ITS strategic planning meetings.

In the assessment of capabilities of an ICM and a measure of the maturity of the organization and data structure, it is recommended that task forces explore the following questions (Wunderlich and Vasudevan 2019):

- Is the lead agency initiating regular CMM assessments and stakeholder meetings and using these efforts to identify incremental enhancements to the ICM?

- Is performance being measured for the corridor using, at a minimum, historical data?

- If this capability exists, should the current capability be enhanced to measure performance using real-time data for one or more modes?

- Are data being shared between stakeholders participating in a coordinated response to an event?

- Do corridor stakeholders share a common operating view of the traffic conditions in the corridor?

- Are data being shared manually or through an automated data feed between stakeholders?

- If a data feed is possible, should a central system be built to integrate near real-time data from multiple sources?

Agency Interviews

The research team interviewed staff from two agencies that had recently implemented ICM strategies. These agencies provided insights on effective practices, challenges, and opportunities in the use of data in ICM systems.

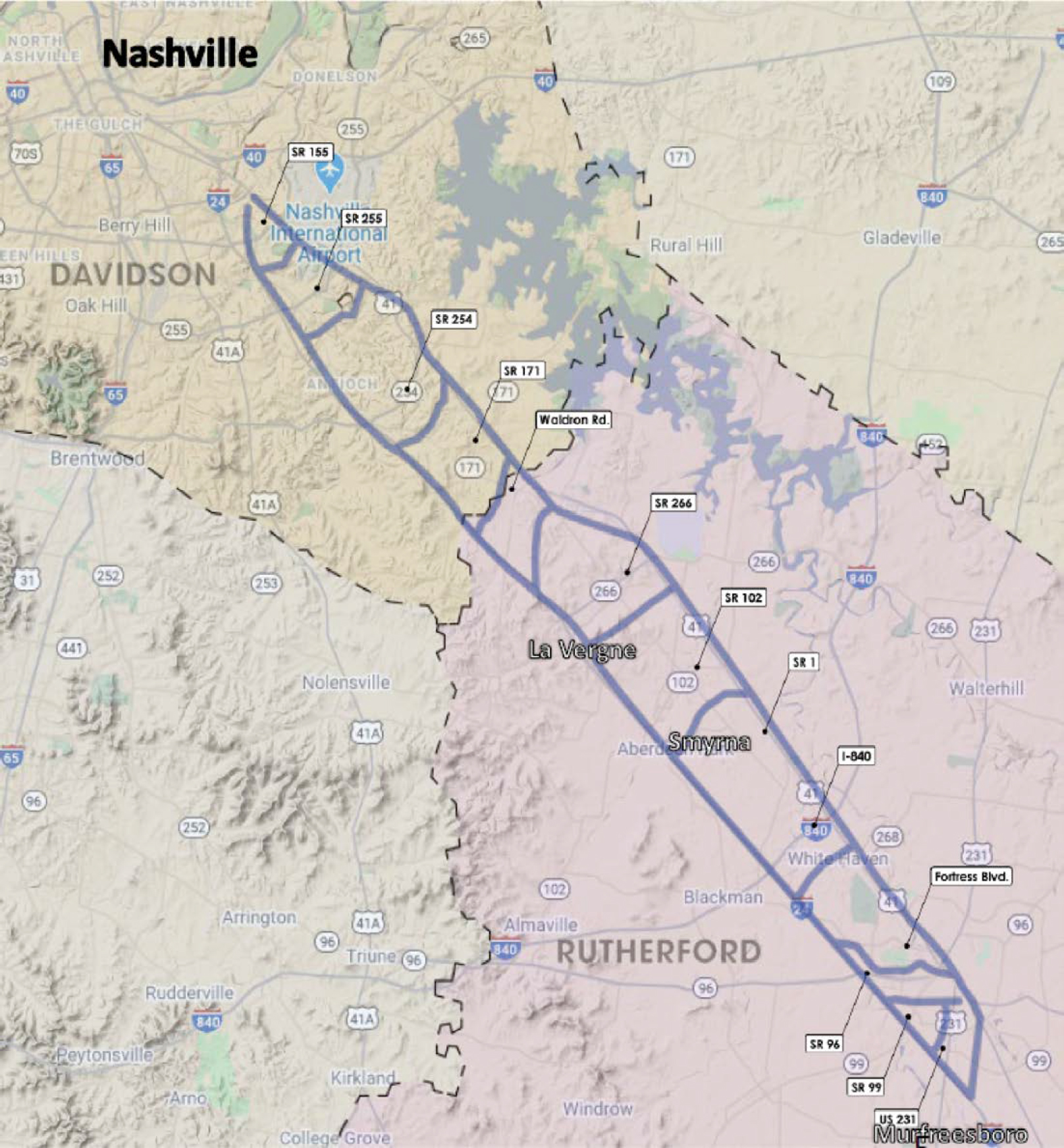

Tennessee DOT I-24 SMART Corridor

TDOT has planned and implemented portions of the I-24 SMART Corridor, which is intended to address congestion on I-24 between Davidson County (primarily Nashville) and Rutherford County (primarily Murfreesboro to the south of Nashville). Information was obtained from a phone interview with three TDOT employees. The corridor, shown in Figure 15-1, is 28 miles and includes I-24 and the parallel US-41/SR-1. These routes serve heavy commuter and freight traffic. The improvements envisioned for the entire I-24 corridor program include the following:

- Emergency pull-offs,

- Ramp meters,

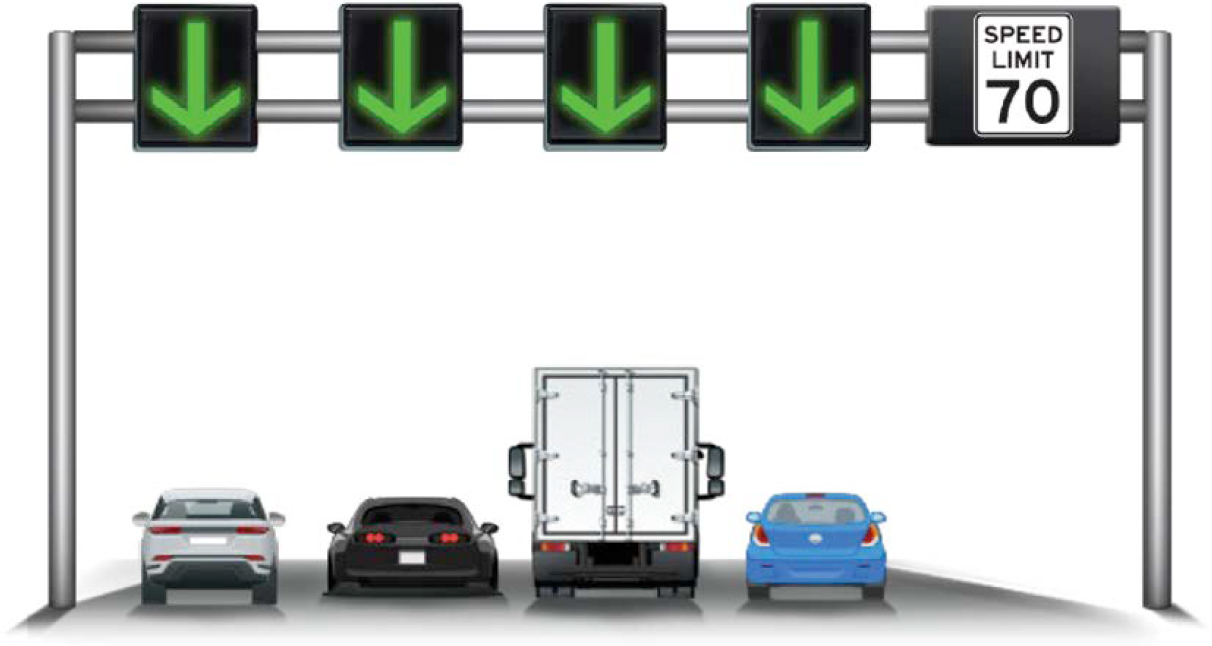

- Active traffic management (ATM) gantries (67 in total) which provide

- Lane arrows and

- Speed limit recommendation,

- Closed-circuit television (CCTV) cameras,

- Communications,

- Traffic signals, and

- Bluetooth monitoring to monitor impacts to arterial streets.

TDOT is planning to phase the implementation of the ICM improvements. Phase 1 is complete, and construction on Phase 2 began in 2022. Phase 3, the final phase, is currently in design and will include communications, CCTV, and dynamic message sign (DMS) improvements on the arterials as well as an automated DSS for ATM for the entire corridor. The ATM, illustrated in Figure 15-2, provides lane arrows for normal operations and uses “X” for incident ahead and lane closure scenarios.

The DSS provides response plans that recommend speed limits, lane or road closures, and messages for the yet-to-be-deployed dynamic signs and ramp signals. Currently, integration of the DSS includes recommended signal-timing plans for US-41, the arterial street that parallels I-24. Other data interfaces to the DSS include smart corridor traffic sensors, local weather, 511, regional ITS, and INRIX data. All responses require human interaction from a traffic management center operator and shift supervisor. Grant funding is being used to develop an artificial intelligence module to operate the lane controls for the ATM.

This corridor includes five agencies that operate various traffic signal systems. One of the biggest initial challenges was that every stakeholder along the corridor had separate and disparate data and asset management systems and followed different communication protocols and standards. Stakeholder challenges were compounded by differences in maturity, as identified in their CMM exercise, that complicated data exchanges. Some interfacing agencies were at much lower levels of maturity and did not have the awareness, systems, or staff available to effectively interface with the I-24 system. These issues have mostly been resolved through postconstruction intergovernmental agreements. Some of the smaller municipalities along the corridor received grants to improve their systems (e.g., signal controllers). TDOT recommended spending more time on agency engagement, planning, and development of the concept of operations (CONOPs) to ensure agency buy-in and to better account for differences in maturity before moving forward into implementation.

Source: TDOT.

Source: TDOT.

The system, as originally designed, was focused on managing nonrecurring congestion caused by incidents and more recently has added the management of recurring congestion. The smaller municipalities along the corridor are still adjusting to the signal-timing changes being implemented by the TDOT system. Negative feedback on these changes is being mitigated through a more staggered approach to signal-timing changes as traffic increases at each signal rather than less-frequent, larger changes. The overall goal is to provide a traffic-responsive approach to signal operations along the corridor. Challenges associated with the deployment of the City of Nashville’s transit signal priority, which is not yet fully up and running, have resulted in challenges in providing and integrating consistent signal-timing response plans to the I-24 system.

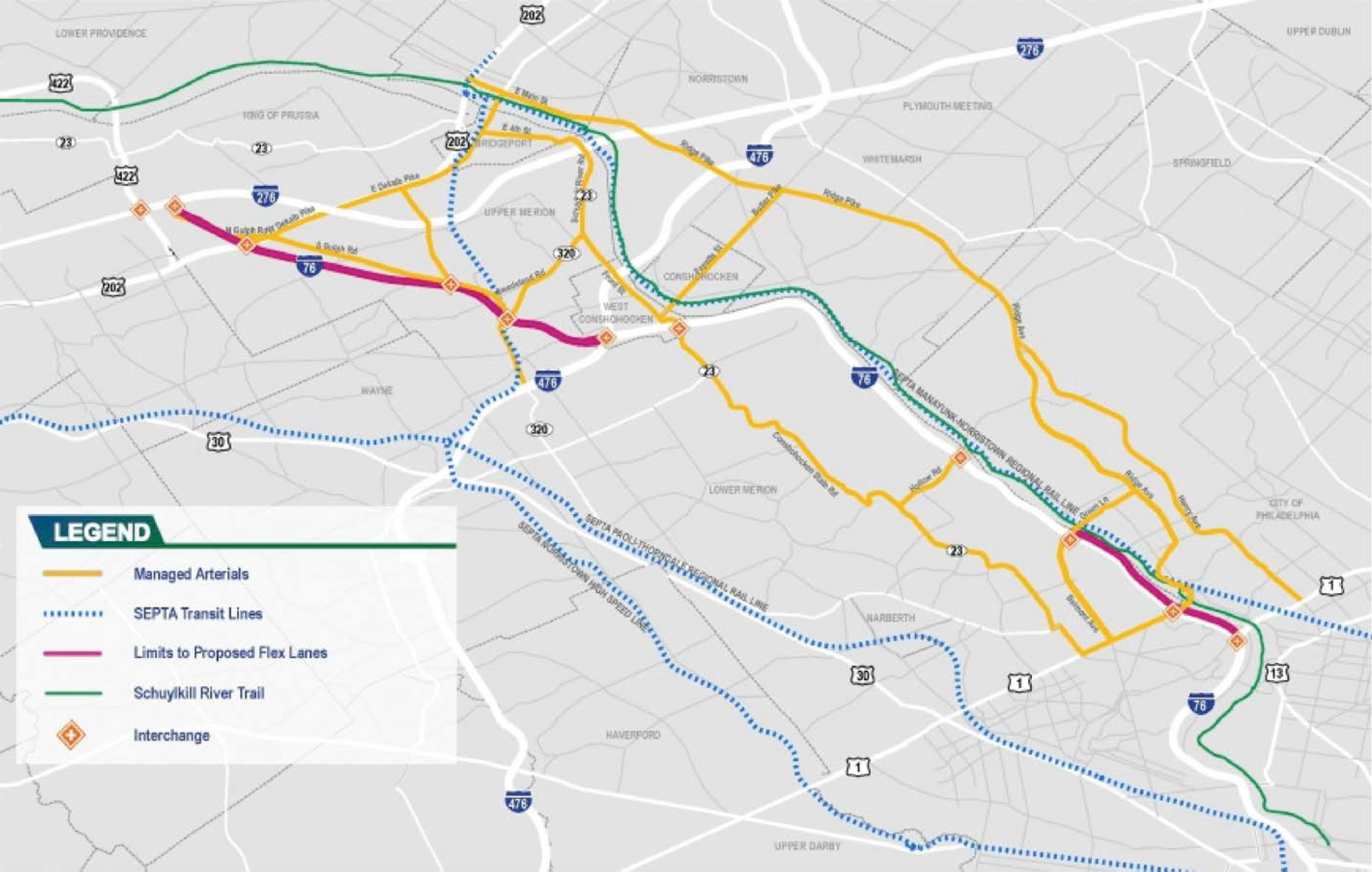

Pennsylvania DOT I-76 ICM

The Schuylkill Expressway, a segment of I-76, is the primary freeway between Philadelphia and its northwestern suburbs (Figure 15-3). The arterial corridors near and parallel to I-76 carry significant commuter traffic. The ICM system will implement various technologies to improve operations along the roadway [e.g., variable speed limits (VSL), queue detection/warning, dynamic junction control, flex lanes/part-time shoulder use, and ramp metering]. The ICM system will also include multimodal improvements (transit routes, bike paths) and proactive management of traffic signals along adjacent corridors. The initial phase of the project included installing VSL and queue detection/warning along the roadway, both of which were activated in 2021. In addition, PennDOT assumed ownership and operational and maintenance control of 60 traffic signals along key arterials from the local municipalities. Upcoming phases will include more-complex, longer-term strategies, including dynamic junction control, flex lanes, and ramp metering.

The full ICM will be multimodal and will coordinate and partner with other regional agencies to make transit, bicycle, and pedestrian trips more accessible and desirable along the corridor. However, measuring data from these other modes presents significant challenges. There is no continuous information on pedestrian or bicycle trips. The agency wishes to have an overarching software interface to monitor usage of the parallel trails, for which the requirements and concepts are being investigated through systems engineering efforts.

Source: PennDOT.

Regarding transit, the Southeastern Pennsylvania Transportation Authority (SEPTA) has had challenges sharing data with PennDOT. These challenges are related to network security requirements and concerns within each agency as well as to challenges with data integration. The information technology departments within each agency often do not see the benefits of interconnection and data sharing for ICM as superseding their mandates to maintain security and minimize potential threats to their networks. Though there have been improvements in the capture of data from SEPTA through public-facing application programming interfaces (APIs), further enhancements will require the establishment of a C2C connection between SEPTA and PennDOT that overcomes security challenges.

Some transit data are shared by SEPTA through a public feed that is scraped by PennDOT to disseminate train arrival information. These data include regional rail train arrival and travel time information. Additionally, PennDOT has installed its own equipment at some transit hubs to provide smart parking information. The intent is to post transit times on expressway and arterial DMS, but, in cases where transit travel times are longer than freeway driving times, travel time comparisons would not be posted. There is a desire to create improved data exchanges to derive bus occupancy data to better understand traveler throughput on the corridor.

The VSL/queue warning system includes a network of 72 VSL signs, 13 DMS (nine of which are new), and 49 microwave vehicle detectors (27 of which are new) that dynamically respond to traffic and safety conditions in real time. All devices were integrated into a new VSL module in PennDOT’s advanced traffic management system (ATMS) software, and the existing corridor module was enhanced to include a real-time algorithmic control system to operate the VSL/queue warning system automatically. The VSL/queue warning algorithm constantly collects data from the network of vehicle detectors, as well as vehicle probe data, and scans for the following:

- The algorithm looks downstream of each VSL device to determine whether there is a slowdown or stopped condition. If there is, the ATMS begins to reduce the speed limit in increments of up to 10 mph per mile (two consecutive signs) to a minimum speed of 35 mph. Queue warning signs are also activated to alert motorists that there is a reduced speed limit or slow/stopped traffic ahead and approximately how far away it is.

- If traffic is generally moving but headways between vehicles are small (conditions that have proven more likely to lead to a rear-end collision), the ATMS lowers the speed limit to a safe speed for the prevailing vehicle headways within and approaching the subject location(s).

VSL operation is automated but can also operate in a DSS fashion with system-generated speed limit recommendations. There are data archiving requirements for the VSL/queue warning, which will be expanded for the upcoming enhancements and will include hard shoulder running (branded flex lanes), lane use control, dynamic junction control, and ramp metering.

Recommendations

On the basis of the papers on ICM deployment reviewed for this chapter as well as the interviews conducted with two agencies implementing ICM systems, there are five revised key recommendations as a follow up to the initial phase of the NCHRP 08-119 research project. These recommendations characterize the most shared stories or advice on effective practices from agencies working on ICM systems. Several of the following recommendations were also identified in earlier phases of study on this project:

- Consider legacy equipment challenges. An ICM CONOPs lays out observed gaps and needs, but the operation of the ICM is at risk if the technicalities of legacy equipment used on the corridor are not fully considered in the follow-up planning and systems development phases. This issue was brought up by TDOT in the team’s interview and is present in some of the

- literature. For example, if communication is required between a central software ICM hub and municipal signal controllers along the corridor, it is essential that these controllers have the capability to provide data interfaces that the hub can use. This misstep could happen if developers move from CONOPs to design without the necessary development of system requirements.

- Consider DSS on a case-by-case basis. In the literature review and the interviews conducted, several ICM practitioners claimed that the use of DSS was essential to the success of their systems. However, this tended to be the case on more complex corridors that require sophisticated transportation system operations and that do not necessarily follow time-of-day regularity. The Dallas ICM did not find the DSS to be any better than human intervention as a long-term solution. Some deployments of DSS, such as in Caltrans District 7, have been determined to require a significant amount of customization. Additionally, DSS business rules, data inputs, and effectiveness should be reviewed and modified regularly to ensure that the ICM is performing optimally. On the basis of the needs and requirements of the ICM, the use of an analysis model (modeled or online) in conjunction with the DSS is also recommended so that the DSS can be evaluated outside of the low-frequency events when the ICM is activated.

- Develop a corridor data policy. A common complication that occurs early in the development of an ICM, after the development of a CONOPs, is that the sponsor agency does not fully vet the data sharing and security policies internally and with participating corridor agencies. As with legacy equipment challenges, if an ICM developer moves straight to design without considering the data interface requirements of the agencies sharing data, this may lead to unattainable expectations that could hinder the development of the ICM. Data policies need to include requirements on the dissemination and sharing of data between ICM stakeholder agencies. Key considerations include the security requirements of the participating agencies, network and data storage needs, and the level of automation that data dissemination needs to achieve.

- Review TMDD standards early in the systems engineering process. TMDD standards are high level and, while not necessarily providing a level of detail that is needed in design, are an essential starting point with customizations that must be considered before implementation. As concepts and design are iterated through the design process, TMDD standards should be reviewed. Estimates of development costs should consider this process and potential customizations.

- Create a central physical or virtual data hub. A challenge that ICM practitioners have encountered is that some ICM deployments lack the over-arching, controlling entity of an ICM network or data hub. This is inherent in the fact that an ICM must interface with several different contributing agencies. Ultimately, however, a central location, physical or virtual, should be created. This could also manifest itself through an existing facility or cloud service. This will allow for the proper archiving of data and postprocessing analytics such as modelling.

References

Blake, C., Hardesty, D., Hatcher, G., and Mercer, M. (2015). Integrated Corridor Management: Implementation Guide and Lessons Learned. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Transportation, Research and Innovative Technology Administration, ITS Joint Program Office. Retrieved June 4, 2020, from https://connected-corridors.berkeley.edu/sites/default/files/fhwa_implementation_guide_v2.pdf.

Hardesty, D., and Hatcher, G. (2019). Integrated Corridor Management (ICM) Program: Major Achievements, Key Findings, and Outlook. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Transportation, FHWA. Retrieved March 6, 2023, from https://ops.fhwa.dot.gov/publications/fhwahop19016/fhwahop19016.pdf.

Hatcher, S. G., Campos, J., Hardesty, D., and Hicks, J. (2019). Mainstreaming Integrated Corridor Management: An Executive Level Primer. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Transportation, FHWA. Retrieved March 6, 2023, from https://ops.fhwa.dot.gov/publications/fhwahop19040/fhwahop19040.pdf.

Miller, K., Bouatourra, F., Macias, R., Poe, C., Minh, L., and Plesko, T. (2015). Final Report: Dallas Integrated Corridor Management (ICM) Demonstration Project. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Department of Transportation, Research and Innovative Technology Administration, ITS Joint Program Office. Retrieved June 4, 2020, from https://rosap.ntl.bts.gov/view/dot/3573.

Miller, M., Novick, L., Li, Y., and Skabardonis, A. (2008). San Diego I-15 Integrated Corridor Management (ICM) System: Phase I. University of California, Berkeley: California Partners for Advanced Transportation Technology.

San Diego, CA, Pioneer Site Team. (2008). System Requirement Specification for the I-15 Integrated Corridor Management System (ICMS) in San Diego, California. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Transportation, Research and Innovative Technology Administration, ITS Joint Program Office. Retrieved March 31, 2023, from https://rosap.ntl.bts.gov/view/dot/3300.

Spiller, J. N., Compin, N., Reshadi, A., Umfleet, B., Westhuis, T., Miller, K., and Sadegh, A. (2014). Advances in Strategies for Implementing Integrated Corridor Management (ICM). Scan Team Report, NCHRP Project 20-68A, Scan 12-02. Retrieved June 20, 2020, from http://onlinepubs.trb.org/onlinepubs/nchrp/docs/NCHRP20-68A_12-02.pdf.

UC (University of California) Berkeley. (2020). Data Hub. Connected Corridors Program. Retrieved from https://connected-corridors.berkeley.edu/developing-system/icm-system-architecture-and-design/data-hub.

Wunderlich, K., and Vasudevan, M. (2019). Build Smart, Build Steady: Winning Strategies for Building Integrated Corridor Management Over Time. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Transportation, FHWA. Retrieved March 6, 2023, from https://ops.fhwa.dot.gov/publications/fhwahop19039/fhwahop19039.pdf.