Data Integration, Sharing, and Management for Transportation Planning and Traffic Operations (2025)

Chapter: 11 Uses of Smart Work Zone Devices for Work Zone Data Feeds: Five Case Studies

CHAPTER 11

Uses of Smart Work Zone Devices for Work Zone Data Feeds: Five Case Studies

Introduction

Roadway work zones are dangerous locations for motorists, for pedestrians, and for highway workers. In 2020, there were an estimated 102,000 work zone crashes, which resulted in an estimated 44,000 injuries and 857 deaths (ARTBA Transportation Development Foundation n.d.). Highway workers accounted for 117 of those deaths (FHWA 2022a).

Better, more accurate, and more timely data can reduce the risks of driving in work zones. Collecting, consolidating, and distributing this information, however, has been an ongoing challenge, for the following reasons: multiple agencies may be responsible for various work zones; emergency repairs and other unplanned work zones do not show up in work zone planning systems; and planning data may be very general, providing only a guide as to the time of operations or the precise location of active work zones. For example, a plan may indicate that a 10-mile-long work zone will be active for 3 weeks between the hours of 11 p.m. and 6 a.m., but on a particular day, active work may only occur along 3 of those miles, and the work may extend until 6:30 a.m.

Historically, the lack of work zone information (including work zone presence, type, duration, limit, and more) has hindered the ability of many transportation agencies to actively manage work zones and their operational impacts (e.g., establishing alternative routes and providing timelier and more accurate traveler information). The main challenges that agencies face include the lack of up-to-date information about dynamic construction and maintenance events as well as a lack of common data standards and mechanisms for publishing work zone data.

This chapter discusses two tools for addressing the lack of timely and accurate data. The first is the use of smart work zone devices. These devices use the Global Positioning System (GPS) and contain communications back to a central server and, often, additional sensors. They may include smart traffic cones and barrels, traffic sensors, cameras, flagging batons, and other devices. In some cases, the electronics that make the device smart may be built in; in other cases they may be add-ons. In addition to these temporary infrastructure devices, smartphone apps for worker check-in and automated image recognition from dashcams may be used. These devices help to identify whether and when a work zone is operational and its precise location.

Providing these data at the roadside (e.g., through portable message signs) and to traffic management operators adds value and improves safety. However, the benefits are greater if they can be provided more universally to human drivers as well as to advanced driver assistance systems (ADAS). This requires standardized, open, and widely available work zone data. The Work Zone Data Exchange (WZDx) Specification is a standard for providing this information (WZDWG n.d.-b).

The use of timely and accurate data from smart work zone devices combined with the WZDx improves accuracy by merging all work zone data, including planned and active work zones.

Smart devices minimize the need for human interaction. Standardized data feeds allow for the development of various applications that can be used across the country. With automated information on work zone locations and specific information on lane closures and speed limit changes, human drivers and driver assistance systems can alter their behavior and, thus, improve safety. Providing information far in advance of the work zone allows travelers to adjust their routes or change modes, thereby reducing delays (Felice et al. n.d.).

Overview

This chapter presents five case studies regarding the current or planned use of smart work zone technology as an information source for data sharing with the WZDx Specification. The research and interviews conducted for these case studies were done primarily in 2022 and represent a snapshot of the status of the five programs at that time. The field is evolving at a rapid pace, with public agencies changing and expanding their use of both smart work zone devices and work zone data feeds. For example, Iowa is expanding its use of smart arrow boards to also require the use of smart temporary traffic control devices, beginning in October 2024 (Iowa DOT 2022). The status of the WZDx Specification has been updated in this report to reflect the transition from an FHWA-sponsored project to one jointly sponsored by the Institute of Transportation Engineers (ITE) and SAE.

While there are additional benefits from smart work zone devices, the focus of this report is on their role as information sources for work zone data feeds. Each case study explores one of five public agencies: the Minnesota Department of Transportation (MnDOT), the Kentucky Transportation Cabinet (KYTC), the Regional Transportation Commission of Southern Nevada (RTC), the Iowa Department of Transportation (Iowa DOT), and the Massachusetts Department of Transportation (MassDOT). Four of the five agencies are in the process of implementing WZDx feeds and recognize the value in smart work zone devices. However, they each have taken a different approach regarding prioritizing the incorporation of information from smart work zone devices into their WZDx feeds, and each is also prioritizing different smart work zone devices.

Each case study describes past, current, and planned work activities, along with the project’s goals and lessons learned. Each case study also includes a discussion of the technologies used; the type of data being collected; and how the data are integrated, managed, and applied and lists available resources. The different agency approaches to obtaining work zone data through different technologies are then compared and emerging issues explored.

The final section of the chapter discusses the relationship between the WZDx and three other, related, types of data feeds:

- Existing public agency traveler information data feeds,

- The HAAS Alert Safety Cloud®, and

- The newly launched Real Ontime Accurate Data (R.O.A.D.)™ for Work Zones initiative.

The references cited are listed at the end of the chapter.

Intended Audience

The intended audience for this chapter includes state, regional, and local agencies seeking to use smart work zone technologies as well as those looking to establish a WZDx feed and those integrating real-time data with other data sources, such as work zone planning and tracking systems. This chapter will assist agencies by highlighting recent and ongoing efforts by peer agencies; summarizing their challenges, lessons learned, and recommendations; and providing additional resources.

The Technologies

This section provides an overview of the two classes of technologies the five case studies focus on: smart work zone devices and the WZDx Specification. The former automate the process of collecting current, accurate information on the location and status of active work zones, while the latter provides a standard data format that utilizes planned and active work zone data to enable cross-jurisdictional applications to be developed.

Smart Work Zone Devices

One of the major challenges for providing timely and accurate work zone data is collecting live data on what is happening in the field versus what the work zone planning records indicate. Attempts to have maintenance workers manually provide updates on work status and location—including when work begins, when it is completed, and precisely where the work is being conducted—have often proved to be unreliable and unsuccessful, as the workers’ primary focus is on the road work. Smart work zone devices automate reporting and address this problem.

Smart work zone devices are primarily work zone equipment (e.g., arrow boards, barrels, cones, speed sensors, cameras) that is furnished with GPS positioning, the ability to communicate its location and status back to a central server, and, often, other sensor data. While smartphone apps that enable highway workers to log a work zone as active or inactive are not technically smart work zone devices, they are included for the purposes of this discussion. Similarly, this chapter also discusses automated image processing of dashcam video data used to identify work zone equipment and, hence, the location of work zones.

Multiple vendors now produce a wide variety of smart work zone devices. In addition, they produce aftermarket kits that can turn traditional work zone devices into smart devices. Among the most widely used devices are smart arrow boards. These are arrow boards that can transmit their location, orientation, the arrow board mode being displayed (e.g., flashing left arrow, sequential right chevron), and sometimes their speed and direction of travel (Figure 11-1). The last two parameters help identify arrow boards that have been left turned on and are moving between locations. Smart features only add a few hundred dollars per arrow board (S. Knickerbocker, Codirector, Real-Time Analytics in Transportation Laboratory, Iowa State University, interviewed by B. Pecheux, E. Rista, and K. Klaver March 3, 2021) and existing boards can be retrofitted in just 60 to 75 minutes (Freehling 2021).

In addition to smart arrow boards, there are similarly equipped construction barrels, which can report their location and traffic speeds, and flagging batons, which transmit their position and, by reading a switch, whether traffic is being signaled to stop or to proceed slowly. There are also simple devices that can be inserted into traffic cones to simply report back their location. These can be used to mark the beginning or end of construction zones or define a two-dimensional work zone area or used in construction vehicles. One of the primary advantages of these various devices is that they require little or no additional action to activate. Devices such as smart arrow boards automatically report their information whenever they are powered on. There is not even an additional switch required to have them begin sending information. Other devices, such as smart barrels, may require minimal additional actions, such as being pointed in the right direction and activation of an additional power switch.

At least two vendors, Nexar and Blyncsy, are using machine vision to process video data from dashcams to detect and locate work zones. Nexar sells networked video dashcams that are used for a variety of purposes, including vehicle and liability insurance. They apply artificial intelligence to analyze the image data for several additional purposes, including detecting and locating active work zones. The geolocated images sent back from any Nexar dashcam-equipped

Source: Iowa DOT (2019).

vehicle are analyzed to detect work zone hardware, such as barricades, drums, and traffic cones (Nexar n.d.). Nexar’s work with the RTC is described later in this chapter.

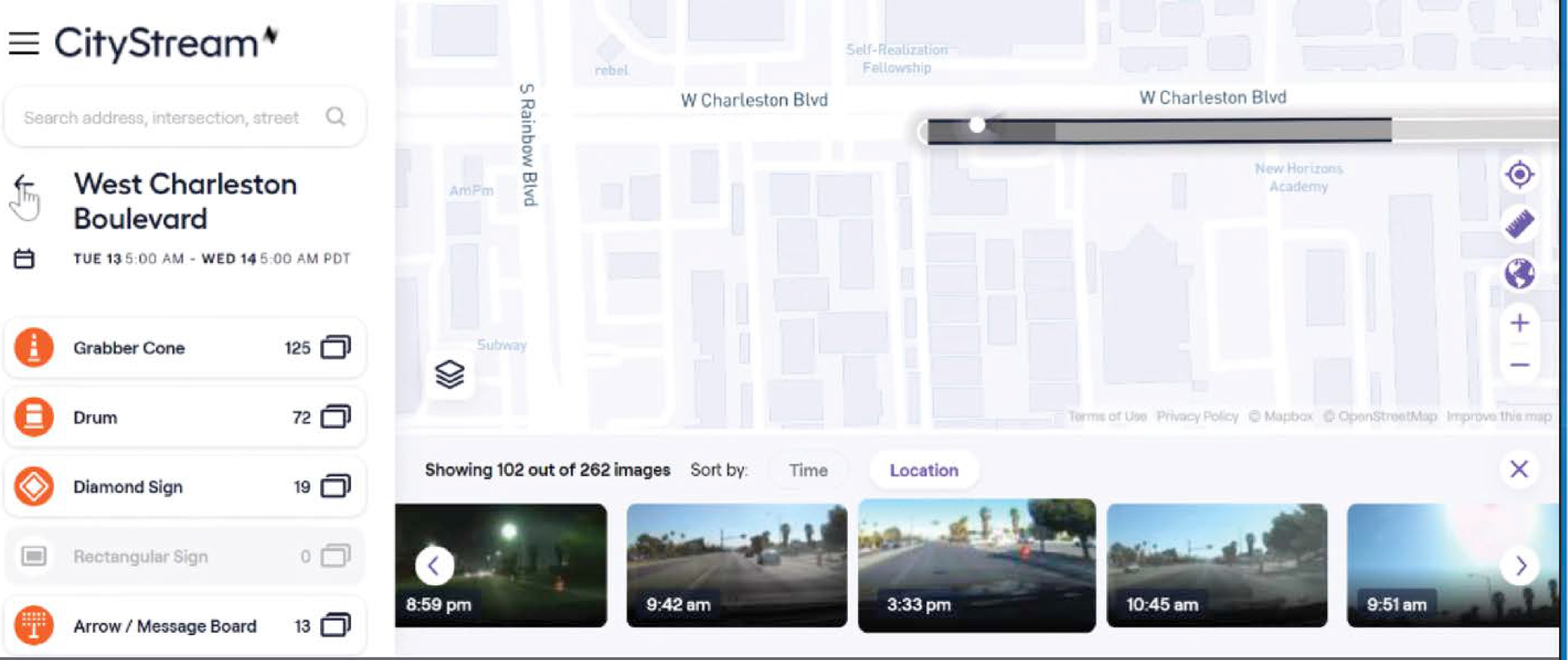

Blyncsy’s Payver system also processes video data from dashcams. Unlike Nexar, Blyncsy does not itself sell dashcams, but instead licenses images from multiple dashcam vendors. Blyncsy currently can pull data from about 400,000 dashcams, and the dashcam market is growing by 300% per year. Payver can be used for multiple applications, including assessing pavement conditions; inventorying road assets; monitoring bus stop status; and detecting work zone devices, including barrels, cones, variable message signs, static signage, and impact attenuators (Blyncsy n.d.). Payver is not being used for smart work zones in any of the case study areas included in this chapter but has been used for this purpose in New York City, and Blyncsy recently won an award to work with North Texas on using Payver to generate information for a WZDx feed. Another innovative use is for remote, visual inspection of work zones. New Mexico has a 20-mile long project on I-40 and a requirement that the work zone be inspected three times per day. Rather than dedicating staff to travel to the site to perform these inspections, the state does this remotely. This does not involve machine vision but still uses geolocated dashcam images. A PDF of the work zone is overlaid on a map to determine the geographic coordinates, and then dashcam images are pulled for that location to walk through the work zone and compare the location of equipment, such as barrels, with where they are specified in the plan (Figure 11-2) (J. Halu, Sales and Customer Experience Manager, interviewed by M. McGurrin Nov. 8, 2022).

Regardless of the technology in use, smart work zones can (Kimley-Horn 2020):

- Relieve traveler frustrations by providing dependable information,

- Inform drivers about alternate routes,

- Reduce congestion,

- Clear incidents more quickly, and

- Improve work zone safety for workers and motorists.

Source: Blyncsy (n.d.).

The Work Zone Data Exchange Specification

Smart work zone devices automate the timely collection of information from work zones. However, to maximize the value of this and other work zone information, data need to be distributed beyond transportation agencies to third parties, who then further distribute it to drivers and to ADAS. These third parties, such as Waze, Apple, Google, and automakers, want these data, but not if the data and format are inconsistent across the 50 states or thousands of localities. The WZDx Specification addresses this issue. The purpose of the WZDx is described as follows (WZDWG n.d.-b):

The Work Zone Data Exchange (WZDx) Specification aims to make harmonized work zone data provided by infrastructure owners and operators (IOOs) available for third party use, making travel on public roads safer and more efficient through ubiquitous access to data on work zone activity.

The goal of WZDx is to enable widespread access to up-to-date information about dynamic conditions occurring on roads such as construction events. Currently, many IOOs maintain data on work zone activity. However, a lack of common data standards and convening mechanisms makes it difficult and costly for third parties such as original equipment manufacturers (OEMs) and navigation applications to access and use these data across various jurisdictions. WZDx defines a common language for describing work zone information. This simplifies the design process for producers and the processing logic for consumers and makes work zone data more accessible.

Specifically, WZDx defines the structure and content of several GeoJSON documents that are each intended to be distributed as a data feed. The feeds describe a variety of high-level road work-related information such as the location and status of work zones, detours, and field devices.

The WZDx Specification was initially developed by the U.S. DOT’s FHWA and Intelligent Transportation Systems Joint Program Office (ITS JPO). Later, in 2019, the Work Zone Data Working Group (WZDWG) was established under the Federal Geographic Data Committee Transportation Subcommittee, and this group has been responsible for updating the WZDx Specification since that time. The working group included representatives from several U.S. DOT agencies, along with state DOTs and the private sector. In 2023, following the completion of Version 4.2 of the specification, future work was transferred to the Connected Work Zones (CWZ) initiative. Going forward, the work is under joint leadership of the ITE, working with AASHTO and the National Electrical Manufacturers Association and SAE (U.S. DOT n.d.-a). The next update to the specification is likely to be released in late 2024, and information will be available on the CWZ web page (ITE 2023).

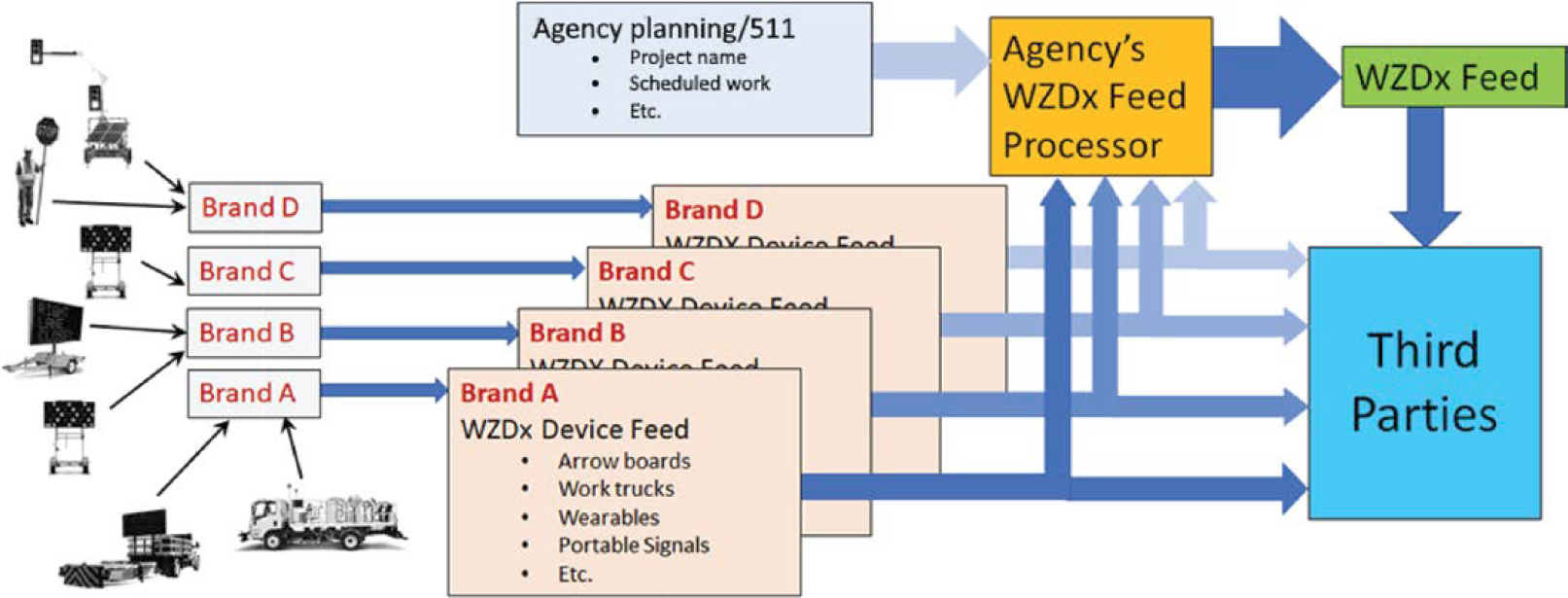

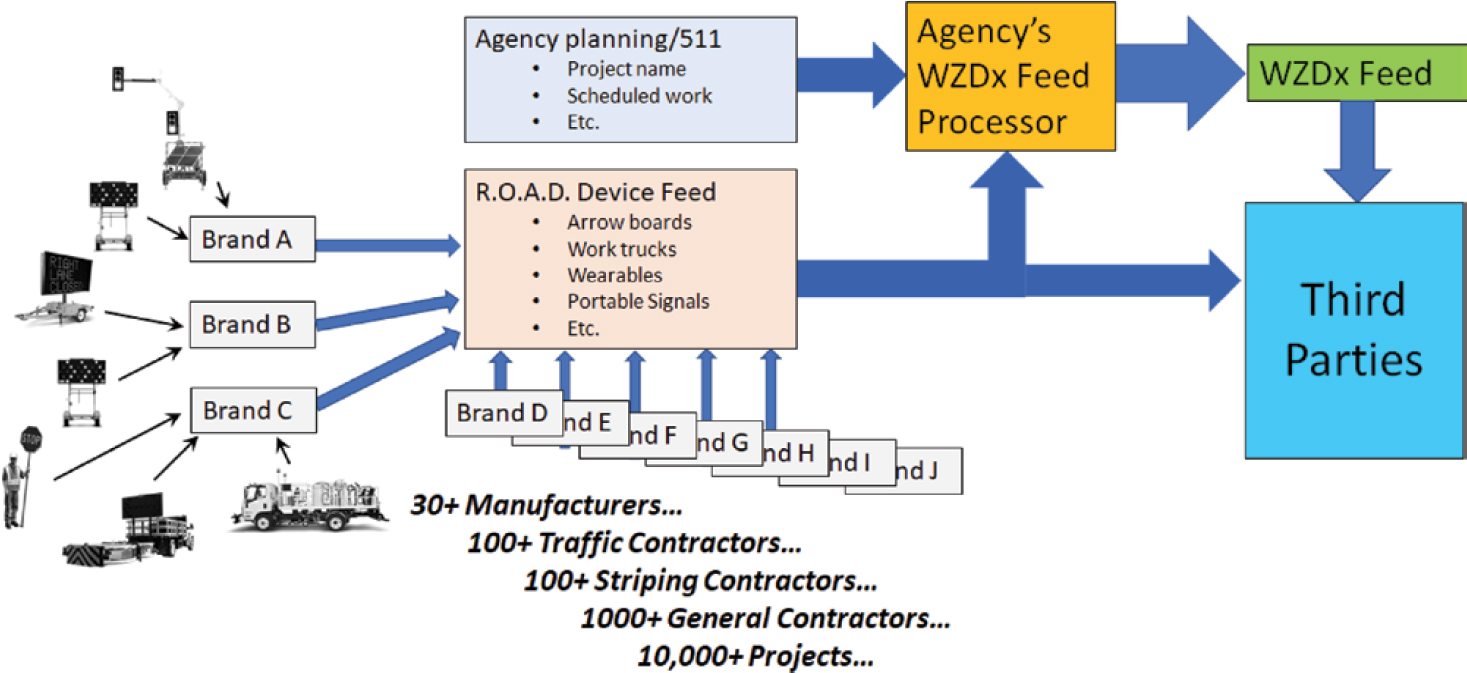

The WZDx Specification defines two feeds: the Work Zone Feed and the Device Feed (WZDWG n.d.-a). [These are the names current as of Version 4.1 of the WZDx Specification. The Work Zone Feed was previously named the Work Zone Data Exchange Feed (WZDxFeed), and the Device Feed was previously named the Smart Work Zone Device Feed (SWZDeviceFeed). The Road Restriction Feed was moved out of the WZDx effort into a separate program.] The Work Zone Feed is used to send data from transportation authorities to third parties, while the Device Feed allows vendors of smart work zone equipment to relay data from smart work zone devices to public agencies. Third parties, such as mapping companies and automakers, may also be interested in receiving the Device Feed. Additional information on each of these feeds is shown in Table 11-1. The Device Feed was primarily developed under a grant from FHWA to MassDOT (see the section on current work in the MassDOT case study below) with input from committee volunteers, including the Iowa DOT (HAAS Alert 2022). For additional information on uses for the Device Feed, see the final section in this chapter, “Relationship Between WZDx Feeds and Other Feeds with Work Zone Information.”

As stated in the README document for the specification (WZDWG n.d.-b), the format for WZDx feeds is GeoJSON. GeoJSON is a data format used to exchange geospatial data, including geolocated objects, such as smart work zone devices and their attributes (Butler et al. 2016). It is based on JSON (JavaScript Object Notation), an open, language-independent, human readable data format based on hierarchical attribute-value pairs and lists. Examples of GeoJSON-encoded

Table 11-1. Data feeds in the WZDx Specification.

| Feed Name | Description | Producer | Consumer | Uses | Content |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Work Zone Feed | Provides high-level information about events occurring on roadways (called road events), primarily work zones, that affect the characteristics of the roadway and involve a change from the default state (such as a lane closure). The Work Zone Feed is the original work zone data exchange feed. | Agencies responsible for managing roadways and road work, typically state and local DOTs | Traveling public via third parties, such as mapping companies and CAVs | Route planning; increased awareness; putting work zones on the map | Work zone and detour road events |

| Device Feed | Provides information (location, status, live data) about field devices deployed on the roadway in work zones. | Work zone equipment manufacturers or vendors | Agencies responsible for managing roadways and permitting work, typically state and local DOTs (third parties, such as mapping companies and CAVs, may also be interested in field device information) | Simplifies design process for agencies wanting to interface with equipment manufacturers; aids in dynamically generating a Work Zone Feed with accurate information; reduces effort for manufacturers to conform to different agencies’ requirements | Field devices |

Source: WZDWG (n.d.-b).

Note: CAV = connected and automated vehicle.

work zone data can be found at https://github.com/usdot-jpo-ode/wzdx/tree/main/examples. A simpler example to provide the flavor of the format is the following JSON representation of an address book entry:

{

"firstName": "John",

"lastName": "Smith",

"address": {

"streetAddress": "21 2nd Street",

"city": "New York",

"state": "NY",

"postalCode": "10021-3100"

},

"phoneNumbers": [

{

"type": "home",

"number": "212 555-1234"

},

{

"type": "office",

"number": "646 555-4567"

}

],

}

As shown, there are simple attribute-value pairs, such as “firstName”: “John”, as well as hierarchical data where an “address” consists of multiple subattributes such as “streetAddress” and

“city”. Also shown is how a value can be a list of attribute-value pairs, as shown for the list of two types of phone numbers.

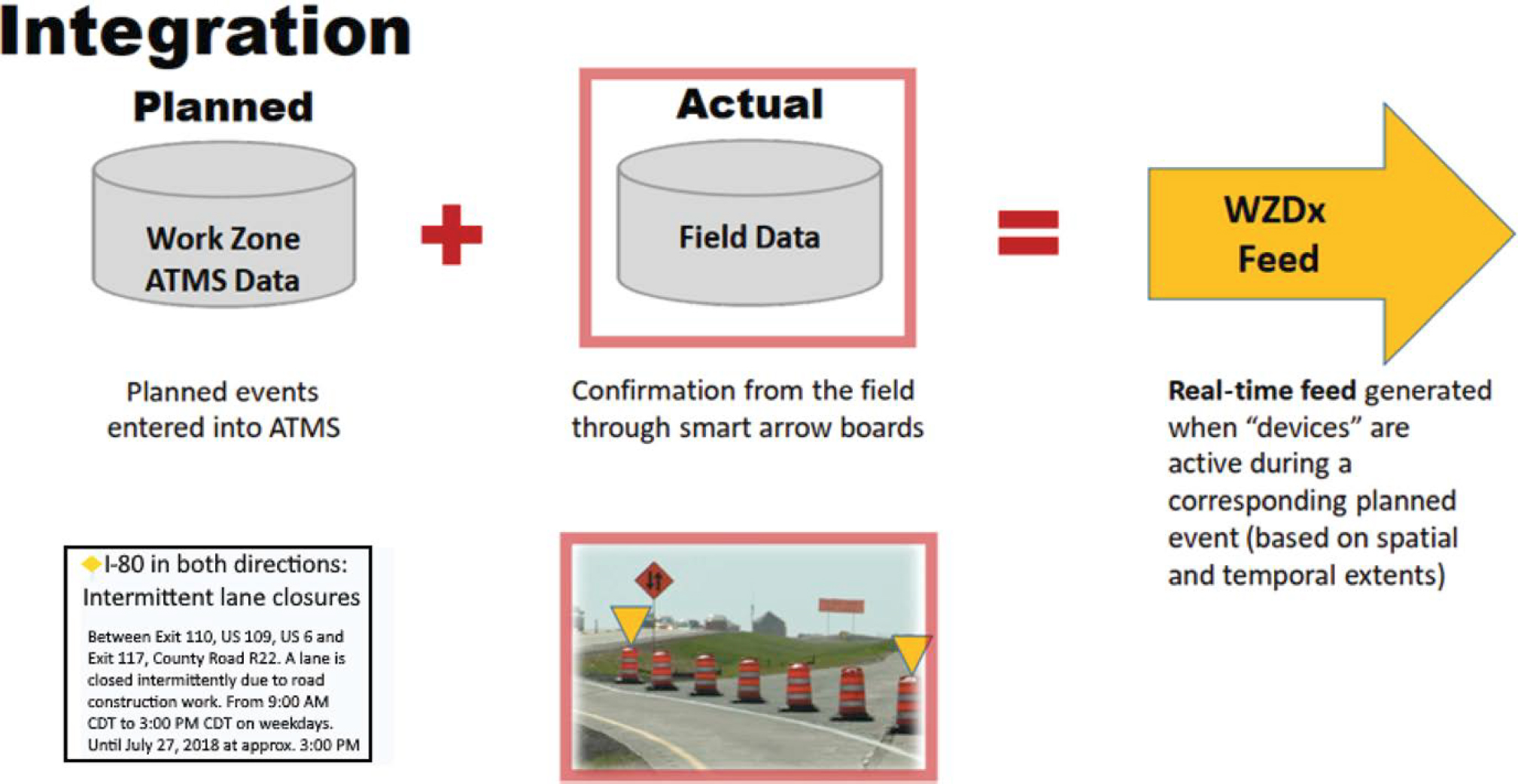

Integration of Smart Work Zone Device Data with Work Zone Data Feeds

The integration of accurate, current work zone information from smart devices with the information from planning and permitting systems, as well as the sharing of this information with third-party stakeholders (e.g., navigation apps, emergency dispatch, ADAS vendors), has the potential to add considerable value to previously available work zone information. Benefits may include traffic management center operators’ increased situational awareness of real-time lane closures, improved information to the traveling public on lane closures, more detailed data on work zone activities for analysis, and improved construction management opportunities (e.g., verification of contractor work status, enforcement of restricted hours) (Roelofs et al. 2020).

Providing this integrated information to third parties via a standardized data feed enables additional benefits, including

- Real-time data about lane closures that can be integrated by third-party navigation apps (e.g., Google Maps, Waze), emergency dispatch, transit, or other systems that route travelers and workers through the transportation network and

- Accurate and precise real-time data on work zones that can be incorporated into ADAS, such as alerting the driver and disengaging cruise control (Roelofs et al. 2020).

However, the WZDx Specification is relatively new. The five case studies in this chapter highlight five agencies that are just beginning to implement WZDx feeds. For a variety of reasons, each is at a different stage of integrating information from smart work zone devices into its feeds. In addition, there are other types of feeds, beyond WZDx-conformant feeds, that may contain information about work zones, either with or without data provided by smart work zone devices. These include existing traveler information feeds provided by many public agencies as part of their 511 traveler information programs and two private-sector initiatives: the HAAS Alert Safety System and iCone Products’ R.O.A.D. Feed. These are discussed in detail in the last section of this chapter.

Case Studies

The activities of five public agencies—MnDOT, KYTC, RTC, Iowa DOT, and MassDOT—were examined. Each has a different history with and is taking different approaches to the use of smart work zone devices and WZDx information feeds. Each case study describes prior work the agency has conducted as well as the ongoing work, including three FHWA WZDx demonstration grants (MnDOT, Iowa DOT, and MassDOT), an FHWA state-based innovation deployment grant (KYTC), and a local project (RTC). Finally, follow-on work that each agency would like to undertake, as well as challenges and lessons learned, is documented.

Minnesota DOT

Previous Work

In 2009 and 2010, MnDOT tested the use of smart barrels to automatically measure traffic speeds upstream of work zones and report it back to the vendor’s servers. The servers, in turn, generated an XML-formatted data feed for use by MnDOT. The use of these smart work zone devices was evaluated for four applications:

- Examination of any congestion to determine whether modifications should be made to a construction project’s traffic control plan;

- Tracking of mobility and delay impacts of the work zone;

- Integration with traffic management and traveler information systems to provide accurate, real-time information to drivers; and

- Determination of the times, if any, that speeding occurred at the work zone and targeted enforcement, so that the historical data could be used to evaluate the effectiveness of enforcement activities at reducing speeds.

However, for these tests, no actual links to MnDOT’s advanced traffic management system (ATMS) or traveler information system were implemented. Instead, for work zones with smart devices, MnDOT’s 511 website linked to the vendor’s website, where the data were publicly available.

Another pilot test, this time of smart arrow boards, was conducted for 1 year, beginning in 2018 and ending in 2019 (Knickerbocker et al. 2021). This was a pilot project that added smart modules to 20 arrow boards (Roelofs et al. 2020). These were deployed in the Twin Cities Metro District from April 2018 to March 2019 on permanent truck-mounted arrow boards and attenuator trailer-mounted arrow boards. These arrow boards were equipped on DOT-owned equipment and were used primarily in urban settings for shorter-duration maintenance activities that only last several hours, including mobile work zones.

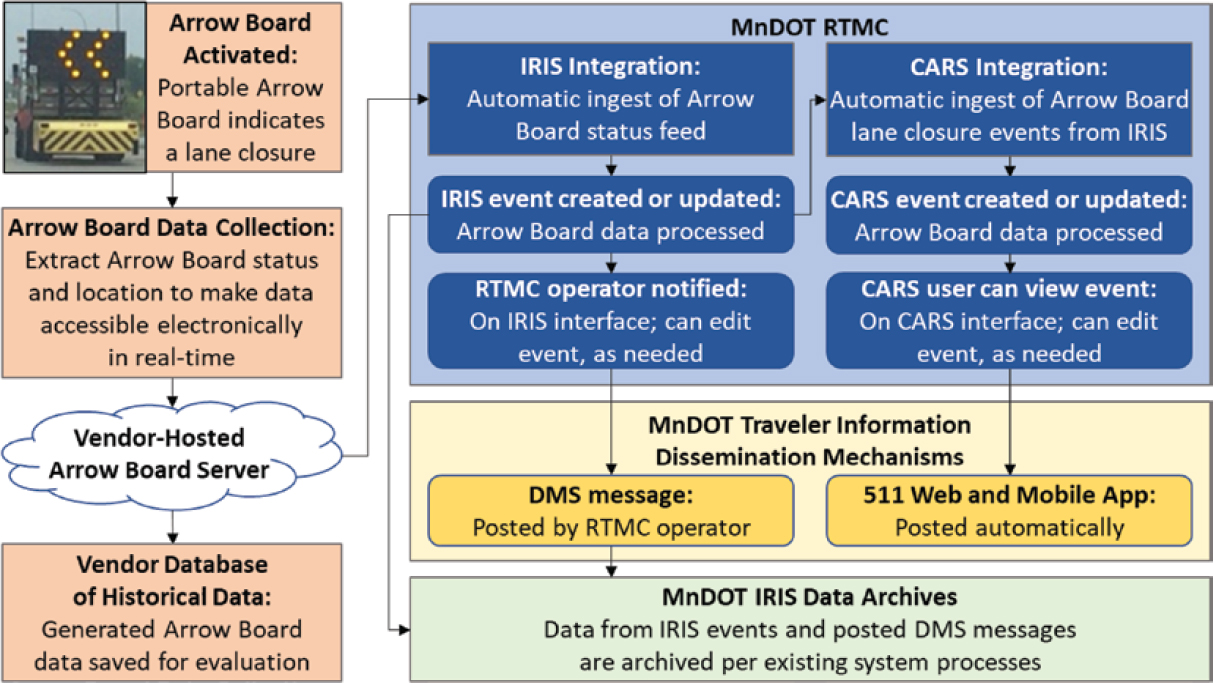

The data reported back by the smart arrow boards were integrated into the state’s ATMS and Advanced Traveler Information System (ATIS); however, they were logged and displayed as independent entries. MnDOT did not attempt to integrate the data with information from its planned work zones entries. Operators could manually add missing information, such as the duration of the closure and any vehicle restrictions (Knickerbocker et al. 2021). The overall system and information flows for the pilot are shown in Figure 11-3. The Intelligent Roadway

Source: Athey Creek Consultants 2018.

Note: RTMC = Regional Transportation Management Center; IRIS = Intelligent Roadway Information System; CARS = Condition Acquisition and Reporting System; DMS = dynamic message sign.

Information System (IRIS) shown in the figure is MnDOT’s ATMS, and the Condition Acquisition and Reporting System (CARS) is MnDOT’s road condition reporting system, which feeds its 511 system.

The smart devices on the arrow boards monitored the status of the boards and provided this information back to the vendor’s system in response to polling messages (Roelofs et al. 2020). The vendor’s central system processed the reported latitude and longitude to associate them with a road and offset and added this information. This processed information, in turn, was made available to MnDOT via a web interface. In addition, the vendor generated an incident feed file that MnDOT’s ATMS could ingest. This was generated whenever there was an active lane closure.

Although this pilot test was considered successful, the smart devices were removed from the 20 arrow boards at the conclusion of the test. MnDOT does not currently use any smart work zone devices. Both this and the smart barrel project were operational tests that did not proceed past that stage into routine use (MnDOT, email, July 2022).

MnDOT does provide work zone information to third parties as one of many types of information that it makes available through its CARS 511 system. Currently, at least 75 MnDOT staff enter data into the CARS system through its web-based user interface. This includes information on current and planned work zones (“Work Zone Data Exchange Demonstration Plan: Minnesota DOT Work Plan,” unpublished work). CARS also ingests information provided by Waze. Once data are entered into CARS, they are published through the state’s 511 phone system, its map-based 511 website, and 511 mobile apps for iOS and Android smartphones. An XML-formatted data feed from CARS is also shared with third parties and neighboring agencies.

Current Work

As of the writing of this report, MnDOT is using its WZDx demonstration grant funding for its CARS eXchange Project (“Work Zone Data Exchange Demonstration Plan: Minnesota DOT Work Plan,” unpublished work). CARS is an event management and road condition reporting system used by multiple states, including Minnesota. The project will provide three enhancements to the state’s existing CARS system:

- WZDx Publisher: The WZDx Publisher will convert existing Minnesota CARS work zone reports into a WZDx-compliant data feed. This will be Minnesota’s first WZDx-compliant data feed and will cover all Interstates, U.S. highways, and state routes in Minnesota. The first step in the project is mapping the data elements in the current CARS system to the WZDx data elements and data structures. Once that is completed, the necessary translation software will be written so that the CARS application programming interface (API) can be expanded to include a WZDx feed in addition to the XML feed currently in use for 511 data. This translation function will take place automatically and the feed will be updated at least once every minute.

- WZDx Import and Fusion Engine: Regional Transportation Management Center (RTMC) operators entered work zone data into the CARS system, and there had been no integration between CARS and IRIS, the state’s ATMS system (MnDOT, email, July 2022). The WZDx Import and Fusion Engine will allow MnDOT to use WZDx-compliant feeds from smart devices and vehicles to generate work zone reports automatically within its system. The system will ingest work zone information from a database of work zones in the CARS system, automatic vehicle location (AVL)-equipped MnDOT maintenance vehicles, and worker check-ins from existing work zones (MnDOT, email, July 2022). This feature will also be able to ingest and process WZDx feeds from neighboring states. For each imported work zone, it will automatically check whether a report for that work zone already exists within CARS. If it does, the system will update that report with any additional information. If it does not, the system will create a new report.

-

Mobile Entry Tool App: A mobile entry tool app, Work Zone/Worker Presence (WZWP) will enable roadway workers to check-in at MnDOT work zones. This iPhone app will be used by workers to report work zone data to the system as well as to capture worker presence. The system will be designed to minimize the amount of information that the user needs to input to create a work zone report. The location will be obtained from the smartphone. The user will confirm the location and input the direction of travel covered by the work zone. They will also check in or out of the work zone. This latter piece of information will be used to populate the optional Worker_Presence field in the WZDx feed.

The projected benefits of the app include increasing coverage of reported work zones in the system, especially short-term work zones. It is also expected to reduce staff time, as it will reduce the need for RTMC operators to create or update work zone events. Finally, the system should also reduce errors that can result when information is verbally related from field staff to RTMC operators.

The projected benefits from the project are as follows (“Work Zone Data Exchange Demonstration Plan: Minnesota DOT Work Plan,” unpublished work):

- Help MnDOT establish its WZDx standardized feed, benefitting data consumers today and connected and automated vehicles and drivers in the future.

- Increase the number, accuracy, and quality of reported work zone lane closures.

- Publishing more detailed work zone data to travelers and third-party providers.

- Establish a standardized process for MnDOT systems to receive work zone event data from other states (and other systems within the state).

- Increase safety by decreasing worker exposure with automating entry. Support additional CARS member agencies in establishing and operating their WZDx feeds at a lower cost.

Potential Follow-On Work

If MnDOT resumes use of smart work zone devices, it anticipates incorporating the data from these devices into the production of the WZDx feed (“Work Zone Data Exchange Demonstration Plan: Minnesota DOT Work Plan,” unpublished work). In addition, if the mobile entry tool app proves successful, MnDOT plans to develop a version for Android phones (the initial version is only for iPhones).

Opportunities, Challenges, and Lessons Learned

MnDOT learned several lessons from the pilot deployment of smart arrow boards in 2018–2019 (NOCoE 2019). It found that there was a learning curve for the agency in determining which applications provided the greatest benefits. It also found that, since the smart work zone technology was new to many contractors and construction crews, there was a need for greater lead time before the road work started to (1) understand the smart work zone equipment and how best to deploy it and (2) allow time for installation and testing. For these reasons, MnDOT recommends that agencies that have not used this technology start by deploying it on simpler projects as a pilot before using it on more complicated projects.

MnDOT identified several lessons learned from the work being conducted with its WZDx demonstration grant (MnDOT, email, July 2022):

- It found that a project champion who regularly liaisons with targeted end users was essential throughout the project.

- MnDOT’s contractor identified that design review meetings in which end users were engaged and invited to provide input and feedback helped establish enthusiasm and buy-in. However, the agency also found that, with the mobile entry app, different end user groups came into the process with “different operational perspectives, incentives, and concerns” (MnDOT, email,

- July 2022). It decided to focus initially on the stakeholders with the most straightforward path to participation (MnDOT-employed work zone inspectors) and developed an easy-to-pilot product tailored to their needs. The app can be expanded in the future to address the use cases of other stakeholders.

- MnDOT’s contractor had some issues with integrating the AVL feeds and recommends that developers seek documentation and sample feeds early in the development process. They found that the documentation might not always match what is deployed. They also recommend that, when entering into data rights contracts with AVL providers, DOTs push for open data that can be used without restriction across multiple DOT projects.

Resources

Agencies may find the following resources to be useful:

- Real-Time Integration of Arrow Board Messages into Traveler Information Systems: Model Concept of Operations (Athey Creek Consultants 2017a), and Real-Time Integration of Arrow Board Messages into Traveler Information Systems: Model Requirements (Athey Creek Consultants 2017b). Provide the concept of operations and requirements for the smart arrow board pilot, covering all user perspectives and the arrow board devices as well as the Real-Time Management and CARS systems.

- Real-Time Integration of Arrow Board Messages into Traveler Information Systems: Final Requirements Testing Report (Athey Creek Consultants 2018). Provides the results of tests run on the smart arrow board pilot system in 2018, including test plans, requirements checklists, and identified issues.

Kentucky Transportation Cabinet

Previous Work

KYTC has, for several years, used smart work zone devices in some work zones. For example, in 2016, it used smart barrels on a project along I-65. These devices include vehicle speed sensors, GPS for locating themselves, communications equipment for transmitting their location and speed data, as well as a solar panel for power. Highway workers only need to position the barrel and flip a switch to turn it on (KYTC 2017).

For that deployment, KYTC used four barrels for each approach direction, spaced 2.5 miles apart. An alert indicating a potential incident was sent when reported speeds dropped below a threshold. In addition, queue warning messages were automatically triggered on an upstream variable message board when speeds slowed below another threshold. The data collected could be stored for later analysis. KYTC does not currently use the WZDx Device Feed as the format for getting data from smart work zone devices and has no current plans to switch to that format.

In addition to receiving data from roadside sensors, such as smart barrels, KYTC also deploys a limited number of smart arrow boards and obtains vehicle probe data for the entire state from HERE, Waze, and its own fleet of 5,500 state-operated vehicles. It also planned to evaluate data from Wejo during the 2022–2023 snow and ice season. The HERE data can provide speed data over very short subsections of roadway and by lane. Therefore, KYTC does not plan to invest in additional speed sensors for work zones. The speed data, regardless of their source (smart devices or probe data feeds) are used for incident monitoring and for queue alerts. The agency has an internal automated email distribution for incidents, and queue alerts are sent out whenever the speed for the work zone drops below 25 mph (C. Lambert, Systems Consultant, interviewed by M. McGurrin and K. Klaver June 14, 2022).

KYTC also implemented a big data analytics system that includes the ingestion of data from smart work zone devices (Stout and Grindle 2019). Although this system ingests data from smart

work zone devices and uses the information for monitoring work zone speeds and crashes, only planned work zone data and data from Waze, not data from these sensors, are provided to the public and to third parties via a website (https://goky.ky.gov/) and data feed. This current feed is not in the WZDx format.

Current Work

In 2021, KYTC received a $100,000 State Transportation Innovation Councils (STIC) State-Based Innovation Deployment incentive grant to develop and deploy a WZDx feed (FHWA 2022b). The funding for this grant became available for use in March 2022. The state received a similar $100,000 grant the previous year to expand the deployment of smart work zones in the state. STIC incentive grants are FHWA grants intended to foster a culture for innovation and make innovations standard practice in the recipient states. Through the program, funding up to $100,000 per state per federal fiscal year is made available to support or offset the costs of standardizing innovative practices in a state transportation agency or other public-sector STIC stakeholder.

As of the writing of this report, KYTC’s goal for the grant project is to implement as complete a WZDx feed as it can, including as many optional fields as possible, by the December project end date and within the funding limits of the grant (C. Lambert, Systems Consultant, interviewed by M. McGurrin and K. Klaver June 14, 2022). This effort is complicated by the fact that KYTC is still completing the transition of its statewide ATMS to the same system that Traffic Response and Incident Management Assisting the River Cities (TRIMARC) uses in Louisville, KY.

To guide the project, KYTC set up a series of ongoing workshops, held once or twice a week, to walk through each field in the WZDx Specification with the various stakeholders to identify currently available data, where these data reside, and what data are missing. On that basis, a level of effort is determined for obtaining each element and a dollar cost assigned. Once this is completed, the data entry tools will be updated to capture missing information. Obtaining the data from various sources is the most difficult part of the project and is expected to take through November 2022. Once this work is completed, it is expected that implementing software to generate a WZDx-compliant feed will take less than a week. The work is being performed by Peraton, the current contractor for KYTC’s ATMS.

At least initially, the WZDx will contain only information on active work zones. Work zones that are planned but not active will not be included. Although Kentucky uses smart work zone devices, information from these devices will not be used initially to populate the WZDx data fields. The data on active work zones will primarily come from KYTC’s AASHTOWare Project SiteManager software (AASHTO n.d.). This software captures the location and active times of all work zone projects within KYTC’s financial purview. However, the SiteManager software defines a work zone as including only the active work area and excludes upstream and downstream signage and lane closures. Construction personnel in the field will provide the locations for the actual start and end of the work zones as defined for the WZDx. Traffic management center staff will import these data (beginning and end times, general location, and general description) and add other information (e.g., lane blockages, closed shoulders).

KYTC did not use the optional Worker_Presence field. The agency did not perceive value in this field and believes that all active work zones should be treated with the same caution.

KYTC perceives multiple benefits from the WZDx effort. The data will be useful for connected and automated vehicle operations. In addition, the agency envisions that the use of a common format will better enable center-to-center and state-to-state communications as well as information exchanges between state and local agencies such as local DOTs and metropolitan planning organizations.

Potential Follow-On Work

Although the initial deployment of the WZDx feed will not include information from smart work zone devices (C. Lambert, Systems Consultant, interviewed by M. McGurrin and K. Klaver June 14, 2022), KYTC expects to integrate these information sources at some point in the future. KYTC is working on how to address the use of the smart work zone device input, as there could be errors in locating the smart devices in the field, and, currently, only a small number of projects in the state use smart work zone devices. The agency plans to analyze logged data to determine whether and how to use data from smart work zone devices in the process. Also, the initial feed will include only active work zones. Including inactive work zones has been discussed and may be added later.

KYTC has considered contracting with a vendor for dashcam video data and machine vision outputs (C. Lambert, Systems Consultant, interviewed by M. McGurrin and K. Klaver June 14, 2022). However, state law currently prohibits the agency from storing video data, thereby limiting their utility. KYTC is working to have the law changed so that it can retain video data for the purpose of training models.

Opportunities, Challenges, and Lessons Learned

One issue that has come up is what defines the beginning and end of a work zone. KYTC’s project management system tracks the actual beginning and end of the section of roadway being worked on, which is smaller than the area where lane closures and warnings may be posted. Therefore, the data from the SiteManager system must be modified to include the actual start and end locations of the work zone. This is currently provided by field personnel.

If the data are available, formatting them to match the WZDx Specification is simple. KYTC estimates that it will take less than a week to develop the software to take the information from the ATMS, once that portion of the project is done, and reformat it into a WZDx-compliant feed (C. Lambert, Systems Consultant, interviewed by M. McGurrin and K. Klaver June 14, 2022).

Resources

Agencies may find the following resources to be useful:

- “Work Zone Monitoring” (KYTC 2021), a presentation on work zone monitoring in Kentucky, and

- Intelligent Transportation System (ITS) Data (Stout and Grindle 2019), a KYTC report on its data program, including work zone data.

Regional Transportation Commission of Southern Nevada

Previous Work

RTC is a unique regional entity with an unusually broad scope. It oversees public transportation, traffic management, and roadway design and construction funding as well as transportation and regional planning for southern Nevada, including Las Vegas (RTC 2022).

RTC undertook a multitrack effort with smart work zones and work zone data feeds (J. Penuelas, Director of Engineering, RTC of Southern Nevada, interviewed by K. Klaver, B. Pecheux, and E. Rista August 30, 2021). Three tracks had been underway for some time:

- Automated machine vision to recognize and geolocate work zones and work zone equipment;

- Development of a work zone ITS specification that would specify required smart work zone devices, processes, and procedures that contractors would be required to implement; and

- The HAAS Alert Safety Cloud system, which uses smart devices to allow the locations of construction vehicles, first response vehicles, construction equipment, and construction workers to be provided to the public over third-party systems such as the Waze traffic app and in-car navigation and information systems (RTC n.d.-a).

A fourth track, described in the section on current work, has recently started.

Machine Vision for Locating Work Zones. The first track was a contract with Nexar to collect information on the location of active work zones (Nexar n.d.) that utilized an entirely different approach than smart work zone equipment. The contract used machine vision to identify and geolocate work zone equipment observed on roadways. Nexar sells dashcams to commercial companies and individuals. These may be used for many purposes, including insurance reporting, fleet management, parking security, and emergency alerts. In addition to these applications, which serve the equipment purchasers, Nexar collects and stores the image data in the cloud, anonymizes it, and applies artificial intelligence technology to automatically process the data to turn it into information for public agencies. This effort includes recognizing work zone equipment and using that information to report work zones. According to Nexar, there are 100,000 active drivers using Nexar cameras in the United States on the road every week, and they process 100 million images per month. Nexar’s Road Inventory software detects, monitors, and maps traffic signals and street signs in addition to work zone devices (Nexar 2021). For work zones, it can detect, identify, and geolocate traffic cones, drums, barricades, barriers, diamond work zone signs, and arrow boards. In addition to geolocating the active portions of planned work zones, the system also finds unpermitted work zones and work zones that are outside the specification of their permits.

Figure 11-4 shows the active work zones detected by Nexar on a particular day. Figure 11-5 shows a work zone captured by the Nexar CityStream system, which analyzes, displays, and provides the data that it captures. RTC currently uses CityStream data but is working to use CityStream’s API to integrate the data into its existing ATMS. Figure 11-6 shows orphaned equipment—equipment left behind—identified by CityStream at a completed work zone. This is one of the applications of CityStream.

RTC began with a proof of concept in 2019 (Nexar 2021). At that time, Nexar had about 2,500 dashcam-equipped vehicles operating in the area (J. Uravich, Senior Project Engineer, RTC, interviewed by K. Klaver, B. Pecheux, and E. Rasta April 28, 2021). That system was later expanded; however, while the system was successful at identifying out-of-compliance work zones and enforcing work zone fees, the contract was not renewed, as it was not a priority for the local agencies. The Nexar data were not integrated into RTC’s Waycare (now Rekor) traffic management system; however, a new demonstration was planned for the latter part of 2022 (J. Penuelas, email, Oct. 2022).

Work Zone ITS Specification. The second track was the development of a draft work zone ITS specification for deploying and operating smart work zone devices. In contrast with the Iowa DOT, which started with just smart arrow boards, RTC’s draft specification called for extensive instrumentation of work zones with multiple types of devices. According to the draft specification, each smart work zone device must have real-time GPS tracking and use XML to provide the data, with the data schema to be approved by the RTC. These data must be updated at least every 15 minutes, and the positional accuracy must be within 3 meters of the actual location. All cameras at the work zone must be capable of remote viewing at designated times or provide video streams. There are also requirements for devices to be deployed to detect and count vehicles, as well as to measure vehicle speeds and volumes, at the beginning and the end of the work zone. These data must be archived into a cloud-based system every 3 minutes. To manage the system, the responsible work zone contractor must identify both primary and

Source: Nexar (2021).

secondary work zone ITS systems managers. There are additional requirements for system and acceptance testing, as well as for training field personnel and other project stakeholders.

RTC hoped to have the work zone ITS specification finalized by the end of 2021 and to make it a requirement for every work zone in the region. However, the specification met resistance and had not been finalized as of June 2022. The draft specification is being used on a voluntary basis, and feedback is being used to improve it. The data that come back from the smart work zone devices are not currently integrated into the RTC traffic management system.

HAAS Alert Safety Cloud. The third track was a pilot test of the HAAS Alert Safety Cloud system to help alert the traveling public to active construction zones. HAAS Alert, a private company, partners with multiple equipment vendors to provide data to its Safety Cloud service (HAAS Alert 2022). The Safety Cloud collects location and alert information from a wide variety of devices, including smart work zone devices and transponders on work crews. The information

Source: Nexar (2021).

Source: Nexar (2021).

is then distributed to third parties, such as Waze, Apple Maps, or automakers, for transmission to drivers. HAAS Alert works with equipment vendors to integrate its transponders directly into the equipment and produces aftermarket transponders that can be used to retrofit equipment.

Other Smart Work Zone Devices. As part of a pilot effort beginning in late 2017, RTC has been operating smart modules on contractor- and city-owned trailer-mounted arrow boards as well as smart pins (Roelofs et al. 2020). The data are not currently integrated into the ATMS nor into a traveler information system, as this is managed by the Nevada DOT, not the RTC. The data are available to RTC staff and the public on a Regional Project Coordination Map (RTC n.d.-b).

Current Work

As a new, fourth track (as of this writing on hold pending input from RTC’s member agencies), RTC plans to develop a smartphone app that would be provided to construction workers and work zone inspectors. The app would allow users to take a picture of the work zone, geolocate it, and connect to work zone permit data so that they could associate the picture, location, and time with a specific permit. This information would then be sent to the traffic management center. This would allow for cross-checking between the plan and conditions of the permit and what was in place in the active work zone.

Opportunities, Challenges, and Lessons Learned

The use of dashcams and machine vision to identify and geolocate work zones and work zone devices has proven to be technically successful. The initial proof of concept led to operational use. However, the system involved new processes, and while it eventually may have reduced workloads, it was not a priority and the program was discontinued (J. Penuelas, email, Oct. 2022).

The work zone ITS specification effort yielded mixed results. It did not receive the widespread acceptance that RTC had hoped for, and an equipment suite conforming to the specification has only been deployed in a few locations. It has worked well in those locations, yet the complexity has discouraged broader use. In addition, as has been the case with some other smart work zone deployments, the major benefits are seen by those responsible for traffic management and operations, while the funding for such initiatives often comes from roadway maintenance budgets.

Developing a WZDx-compliant feed remains a long-term goal for the agency, but in the absence of a funding source, such as a federal grant (which the agency competed for but did not win), it is not a near-term priority.

Resources

Agencies may find the following resources to be useful:

- The RTC Work Zone ITS Specification (available by request from RTC);

- Nexar website with information on its products and services (Nexar n.d.); and

- HAAS Alert website with information on its Safety Cloud system (HAAS Alert 2022).

Iowa Department of Transportation

Previous Work

The Iowa DOT has been working with smart work zone devices for several years and has actively participated in the development of the WZDx Specification. Iowa has taken a very focused approach with smart work zone devices, concentrating on the use of smart arrow boards to automate the collection of the starting locations of active work zones. The efforts

were successful, and, after beginning with five smart arrow boards in 2019, the Iowa DOT expanded the program in 2021 to include all projects with lane closures on Interstate highways. As of 2022, the Iowa DOT had expanded the program yet again to all state highway projects involving lane closures.

The agency began this initiative after identifying several issues with collecting and disseminating information about work zones (Iowa DOT 2019):

- Collecting and reporting timely information was time consuming for staff and competed with other project administration duties.

- Road construction and maintenance activities that required lane or shoulder closures were not always reported to operations staff, which resulted in inaccurate or no dissemination of information to traveler information systems and the traveling public.

- Stakeholders desired more detailed records on the start time, end time, and location of lane closures for improved post–work zone analysis of the transportation management plan and performance measurement.

Iowa was an early participant in the WZDx effort. The agency recognized that without a work zone data feed, information dissemination was limited to dynamic message signs (DMS), 511 systems, and social media. However, a standardized data feed for third parties

allows this information to get to a larger audience when the driver/vehicle need[s] the information most, directly before encountering a lane closure or restriction within an upstream work zone. . . . By distributing these data to a larger audience, drivers, ADS [automated driving systems] . . . , or both are aware of the work zone through audible or other alerts, which supports work zone safety in general.” (Knickerbocker et al. 2021).

However, smart work zone devices themselves do not provide all the information needed, whether for a work zone data feed or for other applications. Data from smart devices must be integrated with data from work zone planning and permitting systems in order to include critical information such as the expected end time of the work zone and any width/height/axle restrictions associated with the work zone; if not marked by a smart device, the location of the end of the work zone can be included (Knickerbocker et al. 2021). To address these issues, Iowa began to deploy smart work zone devices and explore integrating the data from these devices with data from its work zone planning system to generate a work zone information feed for use by third parties.

The Iowa DOT decided to begin small, demonstrate success, and then build upon that success. It focused primarily on using smart arrow boards to mark the beginning of work zones that included lane closures. The agency focused on smart arrow boards because they are easy to incorporate and do not require training for contractors, nor do they impose an additional burden on highway workers. The smart features are automatically activated when the message board is turned on. Roadways maintained by the Iowa DOT were chosen for initial testing because the work zone information on state-maintained roadways was more accurate, the work zone events were easier to identify, and more information on work zone attributes (e.g., length, restrictions, types of lanes) was available.

The current work zone feed, which uses an XML format, is a proof of concept developed and implemented by Iowa State University (S. Knickerbocker, Codirector, Real-Time Analytics in Transportation Laboratory, Iowa State University, interviewed by M. McGurrin and K. Klaver June 27, 2022). Iowa State takes the output feed from the DOT’s 511 system and links the smart arrow board information to work zone information in that feed. A U.S. DOT WZDx demonstration grant is being used to integrate the smart work zone device data with the agency’s ATMS. The integrated data will be used to produce a WZDx-compliant feed and as input to the state’s 511 system, thereby ensuring data consistency.

Implementation Details

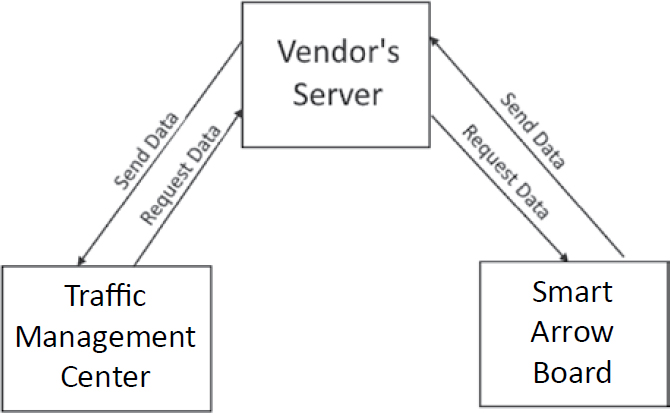

The Iowa DOT and the Iowa State University Institute for Transportation developed the Smart Arrow Board Protocol (SABP) for providing information from field devices to the DOT (Iowa DOT 2019). The SABP provides two options. In Option 1, smart arrow boards communicate with a vendor’s server, and the vendor’s server fulfills data requests from the traffic management center (Figure 11-7). Hypertext Transfer Protocol Secure (HTTPS) rather than Hypertext Transfer Protocol (HTTP) can be used to enhance security. The communication follows a three-step process:

- The traffic management center client software uses a static URL provided by the vendor to submit an HTTP-GET request to the vendor’s server.

- The server responds by sending a JSON document that follows the SABP specification.

- The connection is terminated.

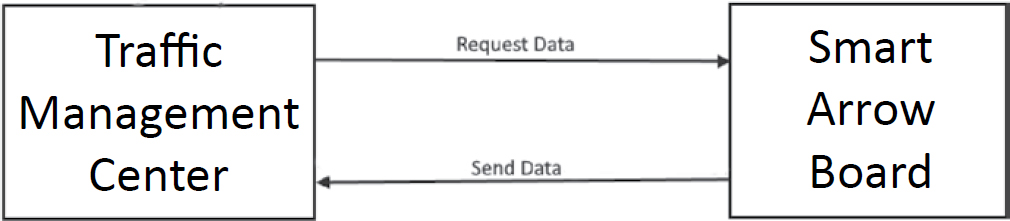

Option 2 is direct communication between each smart arrow board and the traffic management center. The traffic management center (or a human operator) sends GET commands to obtain status information and SET commands to set parameters on the smart message board. The commands and responses are simple, human-readable ASCII text transmitted via transmission Control Protocol/Internet Protocol (Figure 11-8).

Although the specification provides two options, in practice, only Option 1 is being used. Option 2 was provided as a fallback for vendors, but vendors have not been interested. It requires less effort for vendors and for the state DOT to implement Option 1.

Pattern changes on each smart arrow board are updated within 2 minutes, as are notifications if the smart arrow board moves 500 feet or more (Iowa DOT 2019). Each device provides a health check report every 30 minutes. The current work zone feed to external third parties is updated every 30 minutes. In addition to defining the communications methods and the format in detail, the protocol documentation includes a simple, one-page, 10-step testing protocol that applies to either communications option.

Smart work zone devices report back position by latitude and longitude. To simplify the processing needed to associate the geocoded reports with other information related to the roadway, the latitude and longitude data are used to determine the location in terms of the state’s linear referencing system (LRS), that is, the roadway, direction, and distance along the roadway (Knickerbocker et al. 2021). In addition to being computationally more efficient, the LRS is already used to geocode most of the Iowa DOT’s assets, including number of lanes, speed limit, and annual average daily traffic.

Once the data from the smart arrow boards are integrated with data from the planning tools, the data from the boards are used to update the existing information on the location of the start of the work zone events. At that point, the work zone location is updated in the data feed with the location listed as “verified” instead of “estimated.”

Current Work

As of the writing of this report, the Iowa DOT is updating its work zone data feed and bringing it into compliance with the latest WZDx Specification. In addition, the agency is expanding its use of smart work zone devices.

WZDx Demonstration Grant. The Iowa DOT’s WZDx demonstration grant from the U.S. DOT (Iowa DOT n.d.-d) is being used to update its ATMS to integrate the information from the agency’s smart arrow boards and use the fused data to produce a WZDx feed (Figure 11-9) (“Work Zone Data Exchange Demonstration Plan: Iowa DOT Work Plan,” unpublished work). The state’s Q-Free OpenTMS system will be updated to integrate the smart arrow board information. The SABP format will be used to obtain the information. Within the ATMS, planned events/work zones will be combined with the actual field data from the smart arrow boards to produce the WZDx feed. The data from the smart arrow boards will initially be manually linked with the planned work zone data. An operator will assign a reporting arrow board to the location of the planned work zone. At this point, the beginning location of the work zone is marked as verified. Once the smart arrow board is linked with the work zone, they are associated with one another, so any changes are automatically captured, including when the arrow board is transitioned out of active status (i.e., when it is turned off or moved outside of the work zone area).

The optional Worker_Presence field will not be populated. The Iowa DOT has not found a method that it considers good enough for accurately verifying the presence or absence of workers. Testing and evaluation of several options was planned for later in 2022.

The project has three outcome goals:

- Improve the safety of work zones by providing a WZDx data feed with planned and active work zones that can be ingested by third-party data consumers to reach an expanded number of users.

- Improve the quality of work zone data by verifying location and status through the use of connected temporary traffic control devices beginning with smart arrow boards.

- Minimize the workload of contractors/field staff by automating the collection of data.

Expanded Use of Smart Work Zone Devices. The Iowa DOT is working on connected temporary traffic signals that will provide their location information, similarly to the smart arrow boards. The agency originally planned to develop its own specification for these devices, as it did with the SABP. However, since the national WZDx committee was adding the Device Feed format for field devices, the Iowa DOT changed directions and worked with the WZDx committee to ensure that smart traffic signals were included in the new specification and will use this standard going forward. This has caused some delay in rolling out the specification yet aligns the Iowa DOT with national standards going forward. In addition, it is testing other smart work zone devices, including smart connected pins and Ver-Mac message panels.

Source: Institute for Transportation, Iowa State University, Ames, IA.

Potential Follow-On Work

The Iowa DOT hopes to expand the system to include additional work zones on nondivided roadways. Since these projects often do not use arrow boards to mark lane closures, other smart work zone devices will need to be used (e.g., smart batons, smart temporary traffic signals, connected pins, connected barrels) (“Work Zone Data Exchange Demonstration Plan: Iowa DOT Work Plan,” unpublished work).

The Iowa DOT also hopes to revise its work zone planning and permitting system to add automation. This should increase accuracy and reduce the amount of time required from traffic management center staff (“Work Zone Data Exchange Demonstration Plan: Iowa DOT Work Plan,” unpublished work). Today, district DOT or contractor staff must call in lane closure information, which an operator then enters into the ATMS. Once that automation is completed, they will instead enter the data into a new lane closure system that will do quality checks and capacity analysis of the proposed closures. That data will then be automatically provided to the ATMS (S. Knickerbocker, Codirector, Real-Time Analytics in Transportation Laboratory, Iowa State University, interviewed by M. McGurrin and K. Klaver June 27, 2022).

Another concept, which is not yet tested, is to use the smart work zone device data from local agencies to aid in traffic incident management. The Iowa DOT has alternate routes preplanned for major incidents. The concept is to equip local agencies with smart pins that would identify when active maintenance occurs on local roads, so that traffic would not be diverted to those roads.

Opportunities, Challenges, and Lessons Learned

Overall, the Iowa DOT has had significant success with smart work zone devices as well as with integrating the data from smart work zone devices with work zone planning data for multiple applications, including providing a work zone data feed for third parties.

These projects offer several lessons for other states (S. Knickerbocker, Codirector of the Real-Time Analytics in Transportation Laboratory, Iowa State University, interviewed by B. Pecheux, E. Rista, and K. Klaver March 3, 2021, and by M. McGurrin and K. Klaver June 27, 2022). First, push a requirement for smart devices and implement a system for ingesting the data they provide. Iowa started by requiring smart arrow boards because they are simple to operate and inexpensive. It phased in implementation on all Interstates over 3 years and then expanded the requirement to all state highways over an additional year. The arrow boards were a good starting point, as they require no additional actions for workers, needing only to be powered on. The Iowa DOT has also investigated smart devices for marking the end of work zones, including smart pins, but has not found a solution it considers satisfactory. It would require devices that workers must place, power on, and ensure are powered, and the Iowa DOT found that this often does not happen.

Iowa previously offered its SABP standard for use by other states. Iowa recommends that states just starting out use the national standard (the Device Feed portion of the WZDx Specification). Iowa plans to use the Device Feed for new types of devices but will continue to use the SABP for smart arrow boards. Both vendors and the state have already implemented SABP and do not see a need to change at this time.

The WZDx Specification requires that latitude and longitude be provided for specifying the location of the work zone and optionally has fields to provide the road name and linear reference along the road. While the Iowa DOT maintains an LRS for its roadways, in the agency’s experience, the users of its feed are primarily concerned with the latitude and longitude data (S. Knickerbocker, Codirector, Real-Time Analytics in Transportation Laboratory, Iowa State University, interviewed by M. McGurrin and K. Klaver June 27, 2022). It is not uncommon for different organizations to reference roadways by different names, and some stretches of road

have multiple route numbers. Therefore, data consumers want the latitude and longitude data that they can then snap to their own mapping. They may use the route name for additional confirmation.

In addition to providing a feed for commercial third parties, the information provided by smart work zone devices aids in performance analysis. These devices aid in verifying when work zones are active and which lanes are closed: information that can change performance analysis results. For example, whether the throughput, in actual practice, is higher with one lane at full width or with two narrower lanes.

Iowa has done little testing of location accuracy since its first small-scale tests, but it has not run into any issues. Anecdotally, the devices are accurate enough to determine which side of the road they are on, which is more precision than needed for locating the start of work zones and an improvement over what was previously available.

While highly successful, the pilot effort was not without its challenges. Private-sector consumers of the data feed want accurate, current information on the end as well as the beginning of each work zone. The Iowa DOT attempted to test the use of smart devices at the end of the work zone; however, it did not receive positive feedback from work zone contractors. Although they understood the benefits, contractors in Iowa were not very receptive to the idea of installing smart devices at the end of work zone locations. There is no standard protocol for locating these devices, and contractors would often forget to set them up (S. Knickerbocker, Codirector, Real-Time Analytics in Transportation Laboratory, Iowa State University, interviewed by B. Pecheux, E. Rista, and K. Klaver March 3, 2021).

An additional challenge, which was overcome, was mismatches between the location reported by the smart arrow board and the work zone start location in the planning records, as the actual start of a work zone in the field does not always precisely match the location in the permit. This resulted in some of the arrow boards being located outside of the nominal limits of the work zone as defined by the permit. The project staff addressed this discrepancy by adding a buffer of 1 mile before and after the work zone boundaries defined in the permit to account for those arrow boards that kept appearing outside the boundaries of work zone projects.

The project staff also reviewed smart device reports from areas well outside any active Interstate work zone. Over a two-and-a-half month period, they identified 500 events coming from such devices, such as a pattern change or device moving more than 500 feet. The hypothesis is that these reports are coming from devices being used on local projects (S. Knickerbocker, Codirector, Real-Time Analytics in Transportation Laboratory, Iowa State University, interviewed by B. Pecheux, E. Rista, and K. Klaver March 3, 2021). This is a positive development. Since smart devices are required for Interstate projects, and they aid construction companies’ asset tracking and management, many local projects in Iowa are already using smart devices, which will make it easier to expand the scope of the work zone data feed.

A minor challenge the Iowa DOT experienced was the use of different authentication processes by different equipment vendors (S. Knickerbocker, Codirector, Real-Time Analytics in Transportation Laboratory, Iowa State University, interviewed by M. McGurrin and K. Klaver June 27, 2022). The SABP specifies the format for data, but not the API used to access it. Some vendors implemented additional security measures and placed an upper bound on the number of arrow boards that could be asked about in a single request. This required some additional changes on the DOT side, but it was handled by a small change order and without changing the project budget.

Finally, quantifying the impacts of the WZDx feed is a challenge (S. Knickerbocker, Codirector, Real-Time Analytics in Transportation Laboratory, Iowa State University, interviewed by M. McGurrin and K. Klaver June 27, 2022). With DMS, one can assume that most drivers

going past the sign have at least seen the message that is displayed. This isn’t the case for WZDx feeds. One of the biggest challenges for estimating benefits will be determining, or at least estimating, how many vehicles and their drivers receive the information through third parties.

Resources

Agencies may find the following resources to be useful:

- Iowa DOT Smart Arrow Board Specifications and Requirements (overall requirements) (Iowa DOT n.d.-b);

- Iowa Smart Arrow Board Specifications, Appendix B: Needs/Requirements Analysis: Iowa DOT Arrow-Board Communications Protocol (contains the SABP specification, including testing requirements) (Iowa DOT 2020);

- Iowa’s Approved Product List for smart arrow boards to be used on Interstates (select “Traffic Control, Smart Arrow Board” as material name) (Iowa DOT, n.d.-a);

- “Deploying and Integrating Smart Devices to Improve Work Zone Data for Work Zone Data Exchange” (research paper with detailed information on Iowa’s approach, particularly with regard to location referencing) (Knickerbocker et al. 2021);

- Iowa’s Comprehensive Work Zone Program (case study by Iowa DOT) (Iowa DOT n.d.-c); and

- “Iowa Making Smart Use of Arrow Boards” (magazine article about Iowa’s program) (Freehling 2021).

Massachusetts Department of Transportation

Previous Work

MassDOT has a long history of using smart work zones. It utilized a smart system to provide travel time for a work zone that reduced the capacity of a bridge from four lanes (two in each direction) to only two (one lane in each direction) (N. Boudreau, email exchange, Sept. 2022). In 2011, the agency implemented smart work zones as part of the larger-scale Fast 14 Project (Moran 2012). This project replaced aging infrastructure at 14 bridges along I-93 in just 10 weekends. In 2013 and 2014, MassDOT purchased smart work zone equipment to deploy as needed and developed standards specification and design standards for smart work zones.

MassDOT deploys smart work zones on large, long-term construction projects; the primary goal is to alert road users about construction activity. MassDOT uses its categorization of the expected impact of the work zone project to determine the area to be covered by smart work zone devices and the types of applications to deploy (MassDot Highway Division 2017). This process is shown in Table 11-2.

Table 11-2. MassDOT-recommended smart work zone applications as a function of impact level.

| Project Impact | Extent of ITS Coverage | Travel Time and Delay Notifications | Alternate Route Advisory | Congestion Warning | Video Surveillance | Site Traffic Data | Approach Traffic Data | Capacity Estimate |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Levels 1 and 2 | Work site | Y | Y | N/A | Y | Y | N/A | Y |

| Level 3 | Work site and vicinity | ✓ | ✓ | Y | ✓ | ✓ | Y | ✓ |

| Level 4 | Work site, vicinity, and approaches | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

Key: Y = recommended for some cases; N/A = not applicable; ✓ = recommended for all.

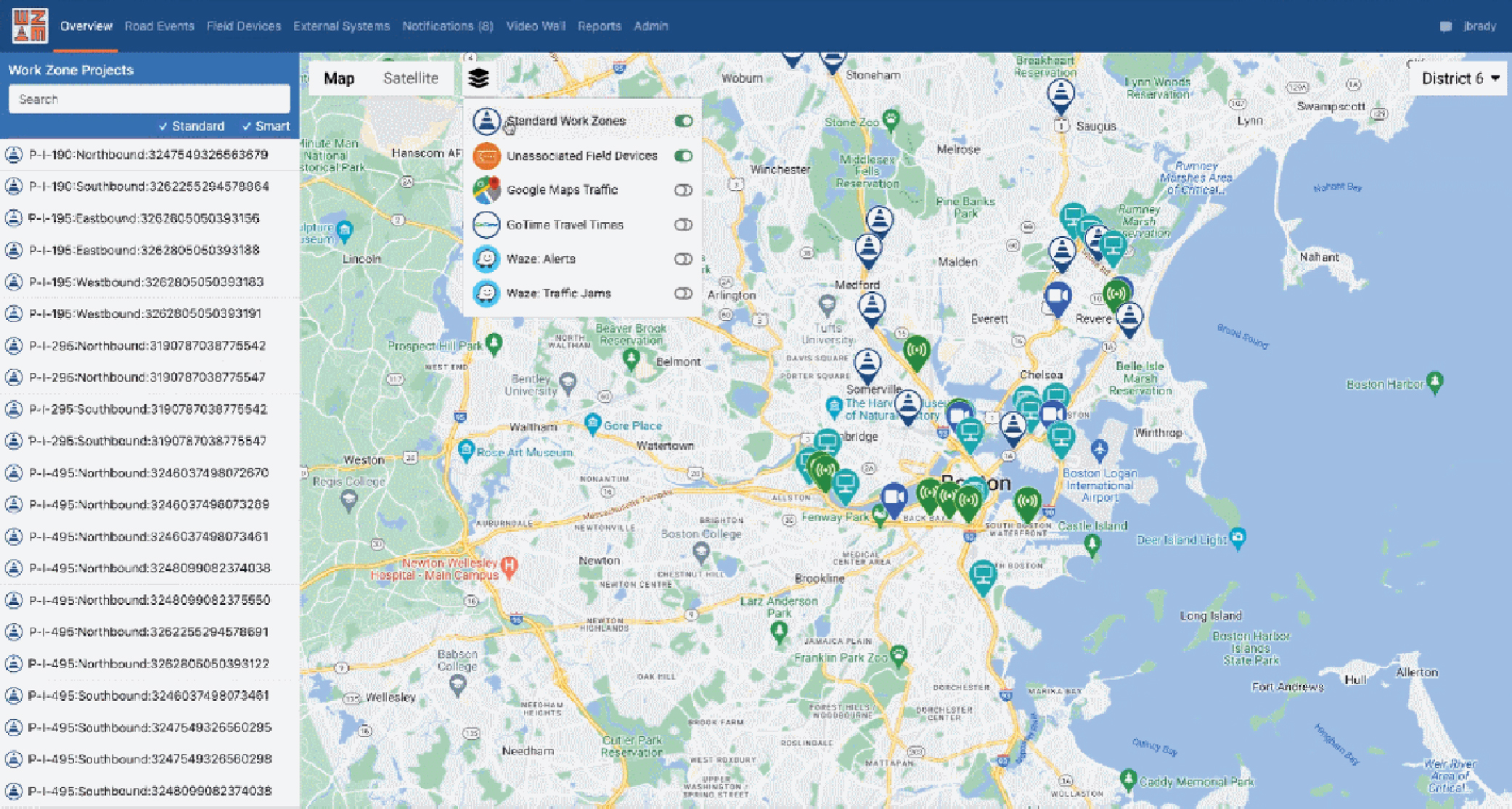

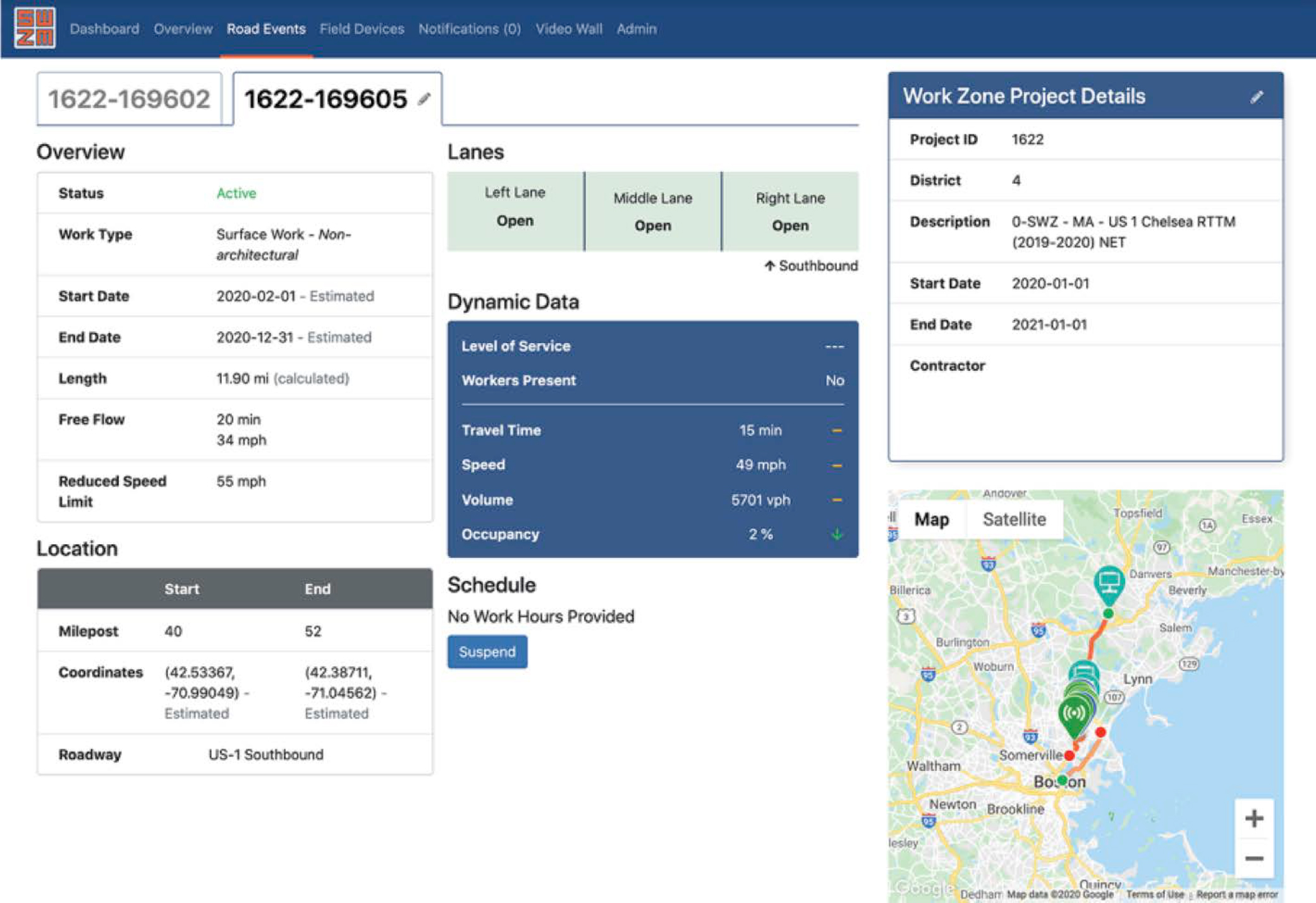

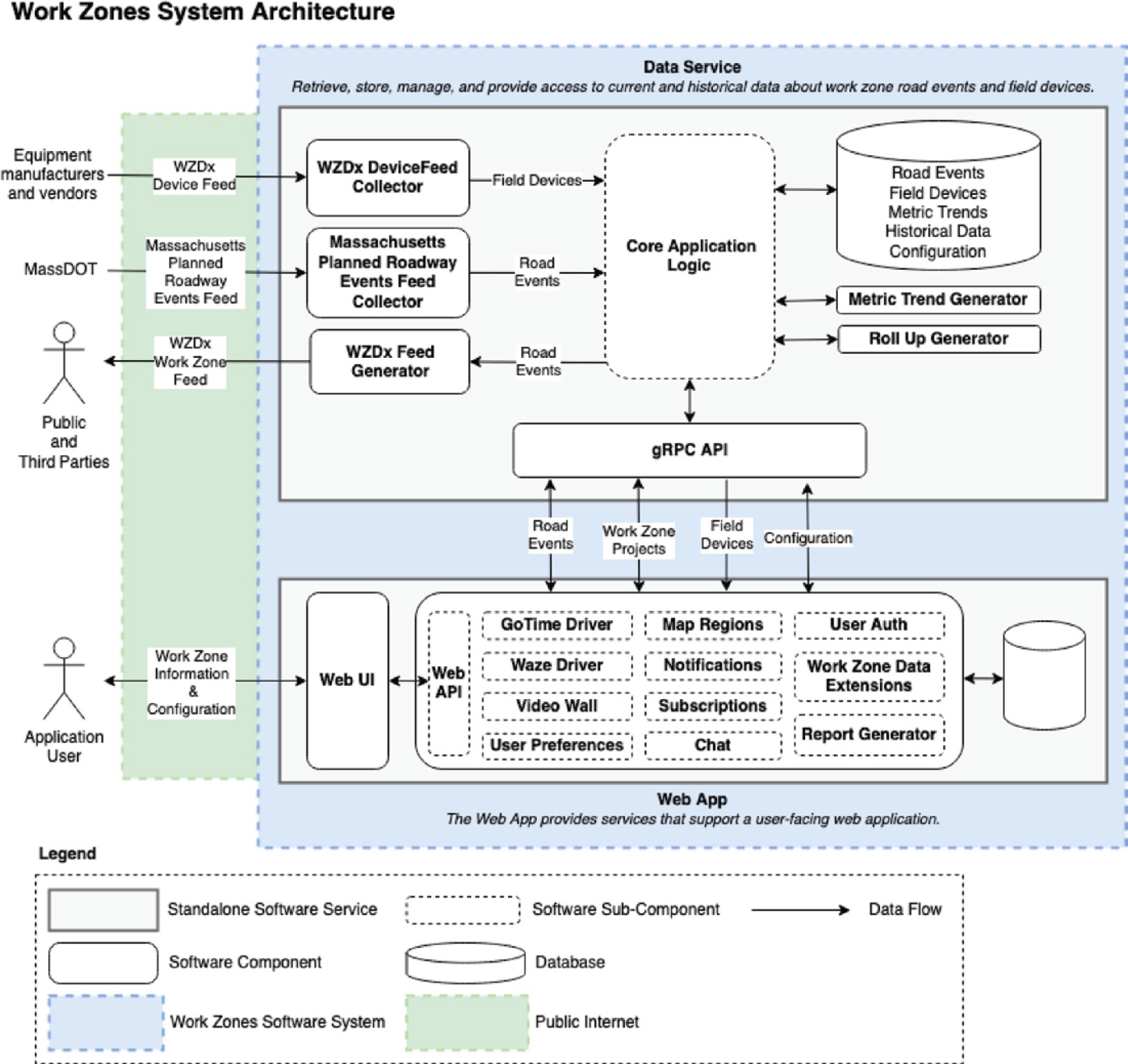

One component of MassDOT’s work is the Smart Work Zone Manager Application Project (Boudreau 2022). (The Smart Work Zone Manger has been renamed the Work Zone Manager, as it will incorporate information on a wider variety of work zones, including those without smart work zone equipment.) This application pulls data from smart work zone sensors and equipment and allows operators to configure, manage, and monitor smart work zones located across the state. The application stores the information in a data warehouse and supplies data to a 511 traveler information system, a mobile app, and an XML feed for use by third parties. The application originally only contained data for smart work zones, which tend to be larger, longer-term, projects. However, as described in the next section, it now incorporates data from other work zones and produces a WZDx feed.

Information from Waze and Google Maps, as well as MassDOT’s own Go Time travel time system, can be selected for display as map layers on the Smart Work Zone Manager’s user interface, as shown in Figure 11-10. Clicking on a work zone brings up additional information on that work zone, as shown in Figure 11-11.

Work on the Smart Work Zone Manager began before MassDOT was aware of the WZDx initiative (National States Geographic Information Council 2021). MassDOT became aware of the WZDx initiative just after the design stage was complete. However, it reworked the design to be consistent with the data elements in the WZDx. In addition to producing a WZDx data feed, MassDOT developed an open, Massachusetts-specific API that vendors must implement to provide data from smart work zone devices to the MassDOT application. The API defined both optional and mandatory elements that vendors must supply.

The API specified that the response data be formatted as JSON data. Communications would use a Representational State Transfer (REST) approach rather than HTTP. Data exchanges followed a request–reply model, with the Smart Work Zone Manager functioning as the client and initiating all communications. A simple username/password authentication process was used to provide security.

Unlike some other initiatives, such as the Iowa DOT’s, which focuses on smart arrow boards, the initial MassDOT work was focused on DMS, closed-circuit television (CCTV) systems, and portable sensors that monitor speed, volume, and occupancy and can provide information on travel times and the location of the back of any queues. MassDOT’s API included, as an optional feature, the ability for the Smart Work Zone Manager to send commands to the field devices. If implemented, the Smart Work Zone Manager could post new messages or delete the current message on DMS and command CCTV cameras to move to a previously defined preset.

Current Work

MassDOT proposed to use its Massachusetts-specific API as the foundation for a national standard that would become part of the WZDx Specification. It received a WZDx Demonstration Grant from FHWA to fund this effort. MassDOT originally envisioned integrating its API directly into the existing Work Zone Feed specification, but as work went on, the agency realized that it made more sense to develop a separate section devoted to collecting information from smart work zone devices, which became the Device Feed.

MassDOT worked as part of the WZDWG (U.S. DOT, n.d.-b) to develop the Device Feed. Much of the resulting specification was built upon the earlier work done by MassDOT for its state-specific specification with input from others, including Iowa, which contributed much of the material relating to smart arrow boards (M. Boucher and J. Brady, interviewed by M. McGurrin and K. Klaver Sept. 16, 2022). Once the WZDx Device Feed specification was completed, MassDOT switched from using its state-specific specification to this new national specification.

Source: MassDOT.

Source: MassDOT.

Massachusetts’ original specification included an optional capability for operators to use the work zone manager system to send commands to field devices, such as setting messages on a DMS or moving a camera to a preset position. However, this two-way data exchange would add significant complexity to the interface, and no vendor implemented the option. This capability was not included in the WZDx Device Feed specification.

As mentioned previously, the role of the Smart Work Zone Manager was expanded to include all work zones and to include information on planned work zones through the addition of an input from MassDOT’s event management system. As part of this effort, the now retitled Work Zone Manager will parse the text fields in the work zone planning data to provide greater scheduling granularity to specify the times a work zone is or is not active. The system architecture for the current system is shown in Figure 11-12.

Potential Follow-On Work