Data Integration, Sharing, and Management for Transportation Planning and Traffic Operations (2025)

Chapter: 10 Improving the Sharing, Quality, and Management of Data to Support Traffic Incident Management Use Cases: A Guide

CHAPTER 10

Improving the Sharing, Quality, and Management of Data to Support Traffic Incident Management Use Cases: A Guide

Introduction

Traffic incidents can have an impact on transportation system performance by causing delays and decreasing travel time reliability for the public and the movement of goods. One of the essential responsibilities of transportation and public safety agencies is to ensure the safe and quick clearance of traffic incidents. According to FHWA, “Traffic Incident Management (TIM) consists of a planned and coordinated multidisciplinary process to detect, respond to, and clear traffic incidents so that traffic flow may be restored as safely and quickly as possible” (FHWA n.d.-b).

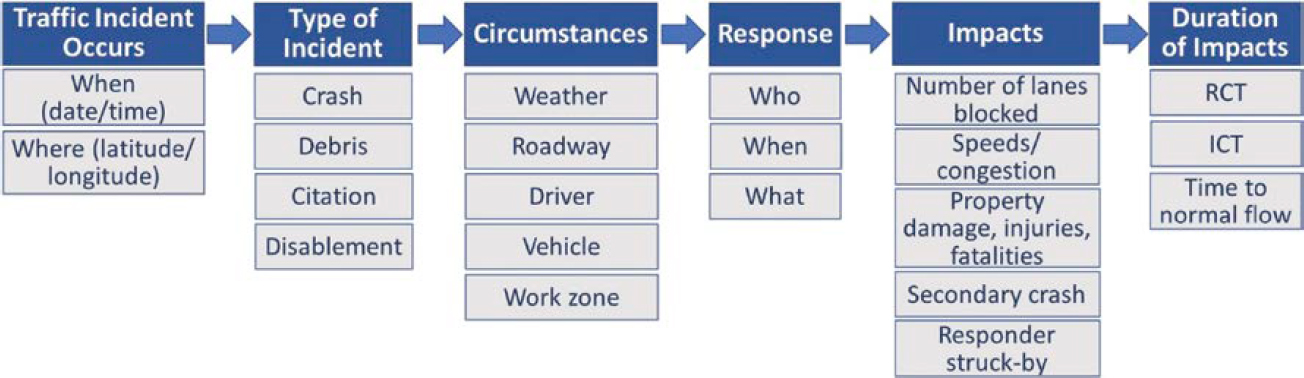

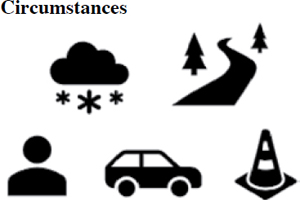

Agencies need data about incidents and incident response to understand how traffic incidents affect system performance as well as the performance and associated impacts of TIM activities. Ideally, a host of data associated with incidents would be available, including when and where incidents occur, the type of incidents, the environment and circumstances surrounding incidents, who arrives or departs the scene of an incident and when, what services are provided, and the impacts and duration of incidents. Figure 10-1 depicts these types of data.

Traditionally, data on traffic incidents and TIM activities have been collected in a variety of ways, including crash reports, advanced traffic management systems (ATMS), computer-aided dispatch (CAD) systems, safety service patrol (SSP) programs, and traffic citation systems. Data on traffic incidents exist; however, many of the data are not available and ready for use in analyses. Therefore, agencies and TIM programs infrequently use these data to enhance their understanding of how they could improve TIM practices and policies to reduce system impacts of traffic incidents. There are three primary challenges that contribute to this limitation in traffic incident data:

- Lack of data sharing: The multidisciplinary nature of TIM creates challenges for data availability. Transportation agencies are responsible for managing the performance of transportation systems, yet partner agencies, including law enforcement, fire and rescue, emergency medical services (EMS), and towing, are often involved in responding to and clearing traffic incident scenes. Most of these partners collect data on their response activities via their own methods and systems. Sharing data between agencies is relatively new and is limited by several factors, including disparate data systems, sensitive data, and agency culture.

- Data quality issues: Traditionally, traffic incident data are collected manually by humans, which can contribute to data quality issues such as missing data and erroneous data. Manual data collection can also lead to data inconsistencies (e.g., where free text is allowed). Timeliness of traffic incident data is also an issue. Data made available months or years after collection have less value than data made available immediately after collection. Finally, because data are collected and stored in silos, they are often difficult to integrate, as they lack a common unique identifier.

Note: RCT = roadway clearance time; ICT = incident clearance time.

- Traditional data management: Traditionally, transportation agencies, as well as TIM partner agencies, have managed internal data in silos with various tools, including spreadsheets and relational database systems. More recently, some agencies have begun to look beyond their traditional sources of incident data to emerging data sources, such as navigation systems data, crowdsourced data, and vehicle probe data, to better understand the impacts of traffic incidents on transportation system performance and TIM performance. These data can be voluminous and structured in a way that does not fit well with an agency’s traditional data management systems.

To maximize the potential for data to improve TIM and to reduce the impacts of traffic incidents on transportation systems, agencies must improve the sharing, quality, and management of traffic incident data.

Background

For nearly two decades, FHWA has sponsored research, outreach, and implementation projects to increase the collection and use of data to improve TIM performance. Within the last decade, TRB’s NCHRP and other programs have also supported work to further the use of data to improve TIM.

The FHWA Focus State Initiative (FSI), conducted from 2005 to 2007, was the first multistate effort to address TIM performance measurement. Through this effort, participating states identified, agreed on, and defined three core TIM performance measures: roadway clearance time (RCT), incident clearance time (ICT), and secondary crashes (Owens et al. 2009).

Following the FSI, FHWA sponsored the TIM Performance Metric Adoption Campaign to encourage adoption of the three nationally recognized TIM performance measures (Carson and Brydia 2011). This project involved an inventory of existing TIM performance measurement practices across states, outreach to decision-makers and TIM stakeholders to encourage the collection of the data to measure TIM performance, and development of a TIM performance measurement spreadsheet to track progress over time.

In 2013, TRB sponsored NCHRP Project 07-20, “Guidance for Implementation of Traffic Incident Management Performance Measurement,” which provided guidelines for the consistent use and application of TIM performance measures in support of the overall efforts of TIM program assessment. These guidelines also include an in-depth discussion of the development, implementation, and application of a model TIM performance measurement database as well as a dictionary of data elements, a model database schema, database scripts, and example analyses of performance objectives or strategic questions that might be of interest to an agency or TIM program (Pecheux et al. 2014).

In 2014, FHWA sponsored additional work toward the institutionalization of TIM performance measurement nationally. Efforts included two national webinars, three multistate workshops, outreach materials, and a document that outlines a process for establishing, implementing, and institutionalizing a TIM performance measurement program (Pecheux 2016).

In calendar years 2017–2018, TIM data were the focus of an FHWA Every Day Counts innovation: Round 4, “Using Data to Improve TIM” (EDC-4). Over that 2-year period, 20 states reported advancing their collection or use of TIM data by at least one implementation stage. States improved the quantity and quality of TIM data and advanced the state of the practice during the EDC-4 period in multiple ways, including via state crash reports, traffic management centers, SSP, and CAD systems integration. In addition, multiple states demonstrated advancements in the use of TIM data for performance measurement and management (e.g., development and deployment of TIM dashboards) (FHWA 2019).

Over the past 6 years, there has been a focus on moving beyond traditional TIM data sources alone to the use of emerging data sources, as well as the integration of multiple data sources for TIM. Examples of such projects include the following:

- The EDC-5 and EDC-6 Crowdsourcing for Operations innovations (FHWA n.d.-a),

- NCHRP Research Report 904: Leveraging Big Data to Improve Traffic Incident Management (Pecheux et al. 2019), and

- NCHRP Research Report 1071: Application of Big Data Approaches for Traffic Incident Management (Klaver et al. 2023).

These projects examined and demonstrated how nontraditional sources of data can be integrated and leveraged to capture not only data on more incidents but also more details about incidents and in a timelier manner.

Purpose and Organization

The purpose of this guide is to provide lessons learned and recommendations for transportation agencies on improving the sharing, quality, and management of data for TIM use cases. Table 10-1 lists example TIM use cases that require a wide range of data.

This chapter is meant to be a quick reference guide that provides agencies an overview and points them toward more detailed information on the basis of their needs. The remainder of the chapter is organized into four sections:

- TIM Data Sharing,

- TIM Data Quality,

- TIM Data Management, and

- Opportunities.

This chapter should help agencies better understand the limitations of the data, the benefits of change, and what steps they can make to improve the data to support TIM use cases.

The references cited are listed at the end of the chapter.

TIM Data Sharing

This section presents common barriers, lessons learned, recommendations, and benefits associated with sharing and gaining access to data from internal department of transportation (DOT) groups, external TIM partner agencies, and private data providers in support of a range of TIM use cases.

Table 10-1. Example TIM use cases.

| Category | Example Use Cases |

|---|---|

| TIM performance |

|

| TIM planning and resource management |

|

| Mobility impacts of incidents and TIM |

|

| Safety impacts of incidents and TIM |

|

| Traveler information |

|

| Advanced technology and data for TIM |

|

| TIM policies and practices |

|

TIM-Relevant Data

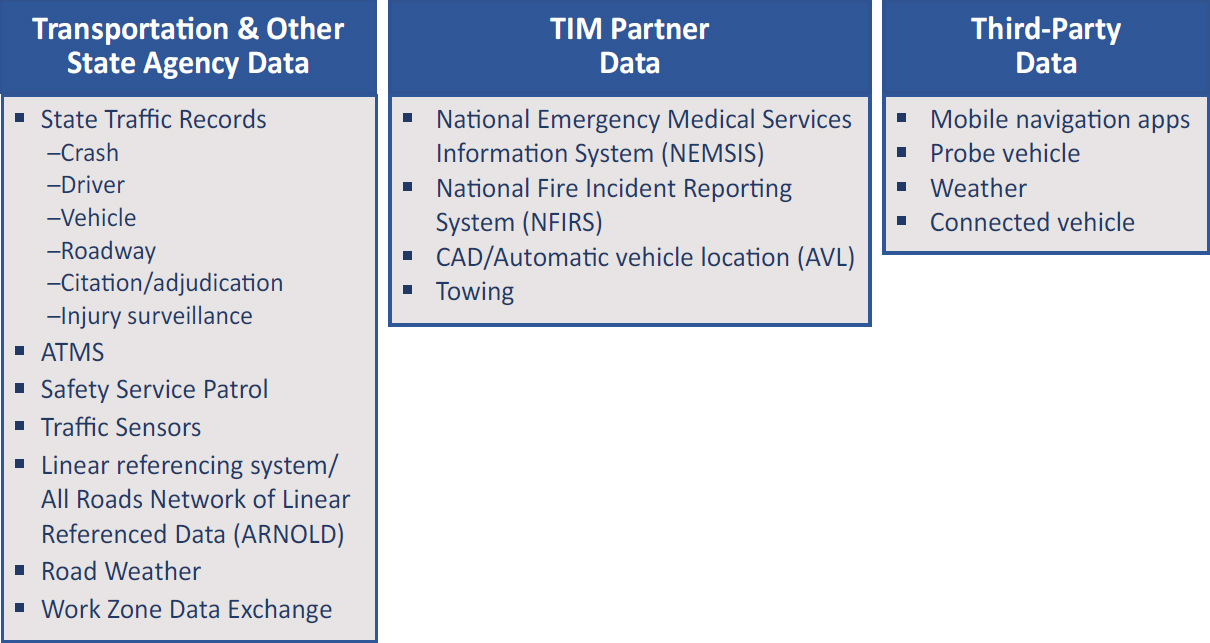

Figure 10-2 shows examples of data from transportation and other state agencies, TIM partners, and third parties that are relevant to TIM use cases.

Data from Transportation and Other State Agencies

- State traffic records systems: State traffic records comprise six core data systems—crash, vehicle, driver, roadway, citation/adjudication, and EMS/injury surveillance. All states collect these data, which contain many data elements of interest regarding incidents.

- ATMS: Traffic data collected and processed in real time from intelligent transportation system (ITS) field devices (e.g., cameras, speed/occupancy sensors), operators of traffic management centers, and field personnel. Some transportation agencies have worked with their law enforcement partners to integrate their ATMS with public safety CAD systems to streamline incident detection, communications, and response.

- SSP programs: Incident assist information collected by field staff present at incident scenes via paper forms and logs, mobile devices, radio communications, and CAD systems. This information documents when and where the incident occurred and what services were provided.

- Traffic sensor data: Includes various detection technologies (e.g., inductive loops; magnetic sensors; video image processors; and microwave, laser, and infrared detectors) that provide direct information concerning vehicle passage (i.e., speed) and presence (i.e., occupancy).

- Linear referencing system (LRS) data: A method of spatial referencing that describes the locations of physical features along a linear element in terms of measurements from a fixed point, such as a roadway mile post. An LRS stores and relates disparate data without

- segmenting and subdividing the underlying centerline data or performing complex geospatial searches.

- All Roads Network of Linear Referenced Data (ARNOLD): The FHWA requirement for state DOTs to include all public roads in their LRS as part of the Highway Performance Monitoring System (HPMS). The goal of ARNOLD was to overcome the lack of a nationally endorsed or industry-wide LRS standard; it consists of the locations of all roads in the United States and a limited set of road segment attribute data.

- Road weather data: Road weather data provide information as to the safety and mobility impacts of weather events on the road. These data are collected at roadway locations via environmental sensor stations (ESS) known as road weather information systems as well as via mobile observations from trucks equipped with automatic vehicle location (AVL) systems. The data describe atmospheric conditions and may also include pavement and water level conditions. The U.S. DOT’s development of Clarus was an attempt to standardize, integrate, quality check, and provide timely, accurate, and reliable weather and road condition information (U.S. DOT n.d.). FHWA collaborated with the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) to transition all Clarus functionality into the Meteorological Assimilation Data Ingest System (MADIS) (NOAA n.d.). The Weather Data Environment (WxDE) is an FHWA research project that collects and shares transportation-related weather data, with a particular focus on weather data related to connected vehicle (CV) applications (FHWA n.d.-c). WxDE incorporates the Clarus data and functionality as well as ways to use CV data and applications to augment station data. WxDE collects data in real time from both fixed ESS and mobile sources and computes value-added enhancements to these data, such as quality-check values for observed data and weather parameters inferred from vehicle data (e.g., precipitation inferred on the basis of windshield wiper activation). WxDE supports subscriptions for access to data in near real time generated by individual weather-related CV projects.

- Work Zone Data Exchange (WZDx): A voluntary work zone data specification to improve the consistency and real-time availability of data on dynamic work zone activities. The WZDx defines the structure and content of several GeoJSON documents that are intended to be distributed as a data feed. The feeds describe a variety of high-level roadwork-related information, such as the location and status of work zones, detours, and field devices.

TIM Partner Data

- National Emergency Medical Services Information System (NEMSIS): A framework and standard for collecting, storing, and sharing patient care information resulting from emergency 911 calls. EMS run reports form the basis for injury surveillance. Local EMS collect the data via standard software from multiple vendors, and the data are then aggregated at the state level. The states then send a subset of data to the NEMSIS national repository (NEMSIS n.d.).

- National Fire Incident Reporting System (NFIRS): The standard used by fire departments to report on the full range of activities. Housed by the U.S. Fire Administration’s National Fire Data Center, NFIRS is the world’s largest national annual database of fire incident information (FEMA n.d.).

- AVL system data: A means for automatically determining and transmitting the geographic location of a vehicle. Transportation, law enforcement, fire, EMS, and towing use AVL to manage vehicle fleets. AVL data include real-time temporal and geospatial data (polled every few seconds), as well as vehicle logs (e.g., vehicle number, operator identification, route, direction, arrival/departure times).

Third-Party Data

- Mobile navigation applications: Community-based platforms that allow users to report traffic events (e.g., crashes, construction/work zones, police presence, road hazards, traffic jams) in real time along their routes and capture confirmation of information by other users (e.g., yes/no, thumbs-up emoji).

- Weather service data: A variety of third-party data providers repackage weather data and forecasts from government data sources into mobile apps; web application programming interfaces (APIs); and real-time, historical, and forecast meteorological data. These data are derived from multiple national and international meteorological data sources and are available via data-as-a-service solutions.

- Vehicle probe data: Vehicle probe data are generated by monitoring the position of individual vehicles (i.e., probes) over space and time. Most vehicle probe data in use by transportation agencies are captured through mobile devices (e.g., smartphone apps) with the Global Positioning System (GPS) that track vehicle movements and, more recently, through capturing data from CVs.

- Connected and automated vehicle (CAV) data: CAV technologies use a variety of sensors, cameras, and communication technologies to collect data about the state of the vehicle and to communicate with the driver, other vehicles on the road (vehicle-to-vehicle), roadside infrastructure (vehicle-to-infrastructure), and the cloud (vehicle-to-cloud). The data are captured and recorded by the system and stored in an onboard or cloud-based system. CAV technologies and data that provide opportunities for incident detection, response, and analysis include vehicle data (e.g., speed, acceleration/deceleration, hard braking, seat belt status), technologies that deliver real-time alerts/notifications (e.g., vehicle infotainment centers, mobile navigation applications), and digital video (e.g., onboard cameras).

TIM Data Sharing Challenges and Limitations

While there is no shortage of data relevant to the analysis and assessment of TIM, as previously stated, the multidisciplinary nature of TIM creates challenges to the availability of data for these purposes. Transportation agencies typically rely on their own data, as sharing data between TIM agency partners is limited and creates challenges. The following list summarizes the primary challenges and limitations in sharing TIM data:

- Disparate data systems and data silos: Disparate data systems and data silos limit the ability to share data because they usually cannot effectively exchange data:

-

- Different systems contain distinct types of incidents (e.g., crashes, citations, CAD).

- Most incident datasets lack a unique incident identifier, which limits the ability to match incidents across systems and may result in duplicate incidents within the merged data.

- Most of these data systems are proprietary systems with proprietary data standards and formats and an absence of shared data elements between systems.

-

Proprietary systems and nonstandard data: Data sharing relies on consistent and compatible data formats, elements, and feeds. Examples in which inconsistencies across systems, agencies, and disciplines exist include georeferencing systems and taxonomies of incident data elements and attributes, which often require additional coding and analytics to resolve. Proprietary data formats also make it difficult to share and integrate data across systems. Other issues related to data standardization include the following:

- There is little or inconsistent formatting, for example, no unified standard for column names and data types or standardized cell values.

- Different standards used across responder disciplines may or may not overlap and may be customized to the culture and habits of responder groups. Examples include the Integrated Justice Information Systems (IJIS) Institute, the National Information Exchange Model (NIEM), and the Global Justice XML Data Model (GJXDM).

- Free-text entries lead to inconsistencies and additional time to search for data entered as text.

- Data may not conform to industry best practices, including data types and data file and export formats.

- Incident data often use dated standards that require additional processing to be integrated with emerging datasets. For example, third-party data, such as Waze, use different coordinate referencing systems than most CAD systems. To integrate CAD data with these third-party datasets requires that the CAD data be reprojected to fit the referencing systems of the other datasets prior to integration. This can be costly, especially with real-time systems.

- Sensitive data/data security: There are concerns about sharing data that contain sensitive information, including personally identifiable information (PII), location information (e.g., AVL system data), and criminal justice information. These data must be protected (e.g., filtered, encrypted) when datasets are shared across agencies; however, the risks associated with protecting sensitive data often result in an unwillingness to share data with or accept data from others.

- Agency culture: Oftentimes, data sharing is not so much a technical challenge as an institutional and cultural challenge. Traditional policies and processes developed decades ago are often no longer appropriate in today’s fast-paced, technology and data-driven environment; however, it can be particularly challenging to change these longstanding and engrained approaches within agency cultures.

- Proprietary data: Business-sensitive data can also create challenges to sharing and integrating data, particularly from private and third-party sources.

- Lack of real-time, automated data sharing: Many TIM-relevant datasets are historical in nature and, even when the data are collected in real time (e.g., ATMS, CAD), the systems lack the ability to share the data for real-time consumption and use (e.g., API). Data are not readily available for modern data analysis applications and real-time analytics, as the data are not machine readable but are provided in bulk downloads for specified time periods.

Keeping TIM-relevant data in silos due to system incompatibilities, sensitive and proprietary data, and agency culture limits the ability to better understand the impact of incidents on network performance and how TIM activities help improve incident clearance. For example, having AVL data about when various responders arrive at and depart from an incident scene would help paint a clearer picture of the response required and the associated performance measures. Similarly, having better access to state traffic records (e.g., driver, vehicle, citation, injury surveillance)

would reduce the amount of data collected by law enforcement and would add greater detail and more information on incident impacts.

These and other challenges, however, have been overcome in the past. The next section provides examples of successful data sharing within TIM and the associated benefits.

Examples of Successful Data Sharing in TIM

The most common TIM data sharing occurs between traffic management centers and public safety communication centers. FHWA’s publication, Integrating Computer-Aided Dispatch Data with Traffic Management Centers (Burgess et al. 2021), looks at integrating data from public safety CAD systems with transportation operating systems to improve incident response and the safety of responders and travelers. It includes case studies of successful data sharing partnerships that improved operational information and traveler decision-making as well as best practices to advance data sharing relationships between public safety and transportation agencies.

The 2020 report, TMC-PSAP Data Integration (ITE and Pat Noyes & Associates 2020), provides examples of successful data sharing between CAD and traffic management center systems. In 2008, the Minnesota Department of Transportation (MnDOT) and the Minnesota State Patrol (MSP) signed an interagency agreement to share data between their systems. MnDOT’s regional traffic management center receives a clear text XML feed from the MSP CAD system that is ingested by the ATMS software. Traffic management center operators “receive a linked copy of traffic related events created by MSP dispatchers that includes location, event type, remarks, and related incident times” (ITE and Pat Noyes & Associates 2020). A firewall restricts access to the law enforcement database to address privacy issues. The system allows traffic management center operators to gather key benchmarks, including response times and lane and roadway clearance times. The data sharing eliminates duplicate entries, reduces data entry, and increases interagency coordination. MnDOT indicated that more than 70% of events that the DOT responds to are from the state police CAD system (Burgess et al. 2021).

Table 10-2 summarizes the key benefits of integrating CAD data into transportation operations systems, as documented in FHWA’s Integrating Computer-Aided Dispatch Data with Traffic Management Centers (Burgess et al. 2021). That report provides specific examples of benefits from the Oregon DOT (ODOT), which experienced a 30% reduction in response time and a 38% reduction in incident duration from integrating CAD data. ODOT also reported a 60% reduction in calls to the traffic management center after it integrated data from the state police into the traffic management center system, which freed operators to monitor, respond to, and coordinate incident response.

Table 10-2. Benefits of integrated CAD.

| Benefits for Law Enforcement Agencies | Benefits for Transportation Agencies |

|---|---|

|

|

Source: Burgess et al. (2021).

Other transportation agencies have benefited from improved awareness of incidents through integration of CAD data. The Virginia DOT (VDOT) reported that the CAD system provided 88% of the crashes in the ATMS. MnDOT indicated more than 70% of incidents were reported via the MSP CAD system, a significant increase as compared with 10% detection through closed-circuit television (CCTV) cameras. In the Phoenix metropolitan area, state and local agencies can access 90% of arterial incidents through an interface with Phoenix Fire and Mesa CAD systems.

Similarly, the Florida DOT’s (FDOT’s) SunGuide system has integrated Florida Highway Patrol (FHP) data through a one-way feed from FHP’s CAD system into a centralized, statewide database. Two FDOT districts are also working to integrate data from local public safety answering point (PSAP) CAD systems. The Niagara International Transportation Technology Coalition (NITTEC) began work to integrate county CAD data with its ATMS in 2006. The CAD system automatically sends data to the NITTEC ATMS to provide better information about incidents faster, to support faster response and quick clearance (ITE and Pat Noyes & Associates 2020).

Another example of successful data sharing is the Waze for Cities data sharing program. Access to Waze data has helped agencies improve incident detection and situational awareness across a wider geography than was achieved with ITS systems alone. Waze provides free crowdsourced data for real-time operations, and integrating Waze data into ATMS and traffic management center operations has proved to be effective in reducing incident detection and notification times. For example, the Iowa DOT found that in one out of every four events over the years 2018 and 2019, the first notification of the incident was from Waze (FHWA 2020).

Recommendations to Improve Sharing of TIM Data

This section provides recommendations on how TIM partner agencies can improve data sharing both internally and externally. These recommendations are based on lessons learned from previous efforts to share TIM data and from recommendations published recently in NCHRP Research Report 1071: Application of Big Data Approaches for Traffic Incident Management (Klaver et al. 2023), which examined the data sharing needs of agencies in the context of preparing for the use of big data. The recommendations include the following:

- Standardize the data. A standardized, consistent data format is essential for intra- and interagency data sharing and to support national initiatives to share and analyze incident data. Facilitate interoperability between datasets by mapping the variable names within each dataset to existing data standards or specifications [e.g., Model Minimum Uniform Crash Criteria (MMUCC), Model Inventory of Roadway Elements (MIRE), World Geodetic System 1984 (WGS84)].

- Use common data file formats. Systems built on newer technologies may not support aging and proprietary data formats. The use of common data formats such as CSV and JSON and open-source formats such as Apache Parquet make it easier to share and ingest data across systems.

- Develop common/shared data elements. Common/shared data elements are critical to integrating different data sources. These unique identifiers can help to match incidents across data systems and to reduce duplicate incidents when data sources are merged.

- Digitize and automate data. Digitized and automated data are easier to share, are of higher quality, and are timelier.

- Use a common data store. Storing data in a common environment (preferably in the cloud for flexibility and scalability) and making the data accessible by TIM partners breaks down data silos and supports easier and more timely access to data. Cloud data lakes allow for the storage and management of large datasets as well as the development of curated datasets and data pipelines that can be easily shared with partners.

- Make incident data available in real time with APIs. For traffic operations and incident management, data need to be available in real time to provide the most value to analysts, operators, and field personnel. Develop APIs to share data internally and externally with partners.

- Remove or obfuscate personal/sensitive information. Sensitive information, such as PII, medical information, or criminal activity, can be managed by opening and sharing modified versions of the data, limiting access to certain data elements within the dataset, and obfuscating or encrypting sensitive data.

- Limit data not related to traffic. Limiting data not relevant to traffic (e.g., criminal activity in CAD, business-sensitive data from towing) reduces the magnitude of data and focuses specifically on information relevant to TIM and traffic operations.

TIM Data Quality

The quality of TIM data affects its usefulness in analysis, performance measurement, and investment decision-making. This section discusses TIM data quality assessments, identifies quality issues and limitations with certain datasets, and offers recommendations for agencies to improve data quality.

TIM Data Quality Challenges and Limitations

NCHRP Research Report 904 (Pecheux et al. 2019) and NCHRP Research Report 1071: Application of Big Data Approaches for Traffic Incident Management (Klaver et al. 2023) provide findings from comprehensive assessments of data quality for a wide range of data relevant to TIM. NCHRP Research Report 904 contains assessments of 31 data sources within six domains: state traffic records, transportation, public safety, crowdsourcing, advanced vehicle systems, and aggregated data providers. The researchers assessed and scored the data sources on nine assessment criteria and two data maturity assessment models/frameworks (one on openness and one on readiness). In NCHRP Research Report 1071, the researchers assessed 16 types of data (as well as multiple data sources within each data type) including traffic incident, traffic, location reference, weather, and third-party CV data. The assessments were based on six dimensions of data quality: completeness, accuracy, conformity, consistency, integrability, and timeliness, each of which can affect the usefulness of data for TIM use cases, particularly big data applications.

Global Data Quality Issues

The findings from the aforementioned data assessments included both global and data-specific issues with respect to quality that limit or affect the ability to effectively use the data, specifically for more modern big data applications. Global data quality issues include the following:

- Incident locations: Methods and technologies used to identify and record incident locations vary (e.g., GPS coordinates, nearest mile marker or intersection, crowdsourcing), and this variation leads to challenges in matching incidents across data sources. Few sources of incident data contain a common/unique identifier to match records.

- Human data collection: Human data collection contributes to quality issues such as limited/missing data, erroneous data, typos, inconsistent/inaccurate coding, and text entries. Data collected manually exhibit various levels of completeness and subjectivity.

- Inconsistencies in structure and content: For example, standardized data types versus a mix of standardized data types and free text can create variations of the same information that lead to data inconsistencies. Data that do not follow a standard or specification can be messy and difficult to work with.

- Data timeliness: Delays in the availability of TIM data, sometimes months or years after collection, limit the usefulness of the data, particularly for real-time operations.

- Lack of metadata: Lack of information such as the referential system used for latitude and longitude requires additional documentation for correct parsing and ingestion of the data.

Data-Specific Issues

Table 10-3 lists common data quality challenges and limitations associated with ideal traffic incident data (as shown in Figure 10-1).

Table 10-3. Data quality challenges/limitations specific to ideal traffic incident data.

| Ideal Traffic Incident Data | Data Quality Challenges/Limitations |

|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Ideal Traffic Incident Data | Data Quality Challenges/Limitations |

|---|---|

|

|

|

|

Note: T7 = time normal traffic flow returns.

Recommendations for Improving TIM Data Quality

The following recommendations suggest ways to improve TIM data quality.

- Automate data collection. Automating data collection and incident reporting where possible can improve data quality. Automatically collecting or recording the times and locations of incidents and the TIM timestamps as well as pulling in data from other systems would help to reduce redundant information, subjectivity, rounding, and human error and would help to improve data completeness, accuracy, and consistency.

- Conduct training on data collection. Regularly scheduled training for law enforcement and other responders could help to improve data quality through more consistent and complete incident reporting.

- Take a modern data approach to data quality. Modern data systems address data quality differently than traditional data systems. These systems consider various aspects of data and tag data elements with quality scores rather than removing “bad” data before they are stored. Data-crawling tools continuously measure data quality trends across each stored dataset. This allows analysts to better understand where data quality might be an issue.

- Develop and adopt standard definitions. Consistent use of terms improves data quality and integrability. Variations in terminology can occur as a result of agency culture or tradition (e.g., the 10 codes used by law enforcement agencies) or different standards for location data. Agencies that use landmark descriptions rather than latitude and longitude should automatically snap landmarks to standard geospatial coordinates to enhance data quality. The MMUCC identifies a minimum set of crash data elements and their attributes that states should consider for their crash data systems. Other existing standards include the WGS84 and MIRE.

When assessing TIM data quality, agencies should consider the six dimensions of completeness, timeliness, consistency, conformity, accuracy, and integrability. Table 10-4 lists questions to ask when assessing data quality on each of these six dimensions (Klaver et al. 2023).

Table 10-4. Data assessment questions.

| Data Quality Dimension | Assessment Questions |

|---|---|

| Completeness: expected comprehensiveness |

|

| Timeliness: whether information is available when it is expected and needed |

|

| Consistency: the data are published the same way across their entire history and geographic coverage |

|

| Conformity: the data follow the same set of standard data definitions, such as data type, size, and format, across their history and geographic coverage |

|

| Accuracy: the degree to which the data correctly reflect the real-world events being described |

|

| Integrability: the ability of the data to be easily integrated with other datasets |

|

TIM Data Management

Traditionally, transportation agencies, as well as TIM partner agencies, have managed internal data in silos by using various tools, including spreadsheets and relational database systems. More recently, agencies have begun to look beyond their traditional sources of incident data to emerging data sources, such as navigation systems data, crowdsourced data, and vehicle probe data, to better understand the impacts of traffic incidents on transportation system performance and TIM performance. These data can be voluminous and structured in a way that does not fit well with an agency’s traditional data management systems.

Key considerations in managing TIM data include opening and sharing data internally within the DOT and externally with TIM partners, making data available in real time, and not getting caught up in one source of truth. This requires effective data governance to manage the security, usability, integrity, and availability of the data, as well as the standards and policies needed to control data and data use (Stedman n.d.-b). Data architecture design should be the first step in the data management process. Without this initial effort, inconsistent environments that need to be harmonized as part of a data architecture arise. Additionally, data architectures must evolve as data and business needs change, making them an ongoing concern for data management teams (Stedman n.d.-a).

Data Management Challenges and Limitations

In the conduct of research for NCHRP Project 08-116 “Framework for Managing Data from Emerging Transportation Technologies to Support Decision-Making” 24 survey responses were received, 11 telephone interviews were conducted, and a workshop was held with 17 stakeholders representing local, regional, and state transportation agencies to understand data management practices, challenges, and limitations (Pecheux et al. 2020a, 2020b). The findings of this research showed that data management challenges are often related more to cultural and institutional barriers than to technical barriers. The challenges identified include the following:

- Data silos. Data collected by agencies or business units are often stored in separate databases and not readily shared with the rest of the organization or other agencies. Agencies struggle to break down these silos, which are often a result of differing agency goals, priorities, and policies. Some agencies’ cultures even encourage business units to keep to their lanes. Business units are reluctant to share their data, and there is a lack of trust in external data sources as well as some internal data sources.

- Tradition and rigid data management practices. Traditional data management practices and processes are rigid and specific to each business unit, which makes them difficult to reconcile. Traditional data governance approaches often involve locking down the data rather than opening them up for expanded uses.

- Reliance on proprietary systems. Reliance on proprietary systems with proprietary database schemas, data formats, and software makes it difficult or impossible for an organization to move away from traditional vendors.

- Budgeting and procurement. Budgeting, procurement, and other interdepartmental friction create additional barriers to coordinating efforts to share and manage data more effectively. For example, hardware-based budget line items are perceived as easier to bill and manage than on-demand charges common with cloud (modern data management) services. Agencies have reported procurement periods of 18 to 24 months or longer for critical data and data infrastructure.

- Real-time data. Real-time data are seen as unvetted and nonauthoritative.

Data Management Recommendations

As previously stated, research shows that culture, not technology, is the biggest barrier to transportation agencies adopting more modern data management practices that could help overcome many of the existing challenges and limitations involved with accessing and using data to improve TIM. Information and guidelines have been developed for transportation agencies to begin making the shift, including three recent projects and reports on modern, big data management that are highly relevant to TIM. This section discusses these products and provides a high-level summary of key data management recommendations.

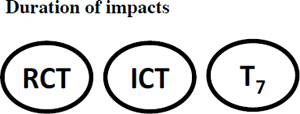

NCHRP Research Report 904: Leveraging Big Data to Improve Traffic Incident Management

NCHRP Research Report 904 reviews and assesses current and emerging sources of data that, if leveraged, could help to improve TIM and the associated impacts of incidents on network performance (Pecheux et al. 2019). This report describes potential opportunities to leverage data in a way that could advance the TIM state of the practice, identifies potential challenges (e.g., security, proprietary, or interoperability issues) for agencies exploring big data applications for TIM, and provides guidelines for TIM partner agencies. Guidelines include collecting and leveraging more data, adopting modern data management practices (e.g., cloud and common data storage environments), using data for decision-making, opening and sharing data and data

products, and using open-source software. The report outlines eight general guidelines for agencies to effectively manage data for TIM:

- Adopt a deeper and broader perspective on data use. Develop big data within a collaborative environment;

- Collect more data. Augment internal datasets with external datasets;

- Open and share data. Share data internally and externally—this is essential;

- Use a common data storage environment. Collocate datasets in a cloud environment;

- Adopt cloud technologies for the storage and retrieval of data. Adopt cloud technologies for data storage and management to provide scalability, agility, affordability, redundancy, and protocols for safe sharing of TIM data;

- Manage the data differently. Store raw data, maintain access, structure the data for analysis, ensure data are uniquely identifiable, and protect data without locking them down;

- Process the data differently. Process the data where they are located and use open-source software; and

- Open and share outcomes and products to foster data user communities. Support the development of data user communities by opening the data, code, data pipelines, and data products.

NCHRP Research Report 952: Guidebook for Managing Data from Emerging Technologies for Transportation

NCHRP Research Report 952 provides guidelines, tools, and a modern data management framework based on the big data management life cycle (Pecheux et al. 2020a). The guidelines include the following:

- Create: Data creation involves collecting data from sensors; identifying internal and external datasets; and assessing, tagging, and monitoring data as they are collected.

- Store: Storage of data should be secure in an architecture that is scalable, resilient, efficient, and built for data formats. Cloud-based storage allows raw data storage and accessibility through open-file formats.

- Use: The use phase focuses on data analysis and the development of products such as dashboards and reports and should be based on a distributed approach to data processing and moving data tools to where the data reside.

- Share: Sharing involves disseminating data, analytics, and products to all internal and external users. It must balance security, liability, and privacy with providing the most use of the data.

The guidebook offers more than 100 data management recommendations across the data life cycle that will help agencies modernize their data management practices to make better use of data for TIM use cases and decision-making. The guidebook introduces new concepts and methodologies concerning data management, along with industry best practices for big data. This guidebook offers experiences from transportation agencies that have navigated the implementation of modern data management practices to extend beyond traditional siloed use cases, including their challenges and successes.

NCHRP Research Report 952 also presents a roadmap for transportation agencies on implementing the framework and recommendations to begin shifting—technically, institutionally, and culturally—toward effectively managing existing data and data from emerging technologies.

NCHRP Research Report 1071: Application of Big Data Approaches for Traffic Incident Management

NCHRP Research Report 1071 demonstrates the feasibility and practical value of big data approaches to improve TIM (Klaver et al. 2023). The team identified TIM big data use cases,

Source: Klaver et al. (2023).

gathered and assessed data required for the use cases, and built data pipelines using modern data management and big data practices and techniques. While this was feasible, there were challenges and limitations with the data available, particularly the data provided by public agencies (e.g., quality issues related to completeness and consistency, lack of standardization of the datasets, data not being machine readable or delivered in ways that facilitated ingestion). While fewer challenges and limitations may exist when getting data directly from third-party data vendors, these data usually come at a price, and agencies have little control over how the data are collected, served (standards used), and controlled for quality. Figure 10-3 shows a summary of recommended guidelines from this project.

Opportunities

With new technologies emerging frequently, the data landscape is changing rapidly, creating promising opportunities, some of which cannot yet be imagined. Transportation agencies need to explore innovative approaches for collecting, sharing, managing, and using data and must remain flexible to quickly adopt new sources of data as they become available.

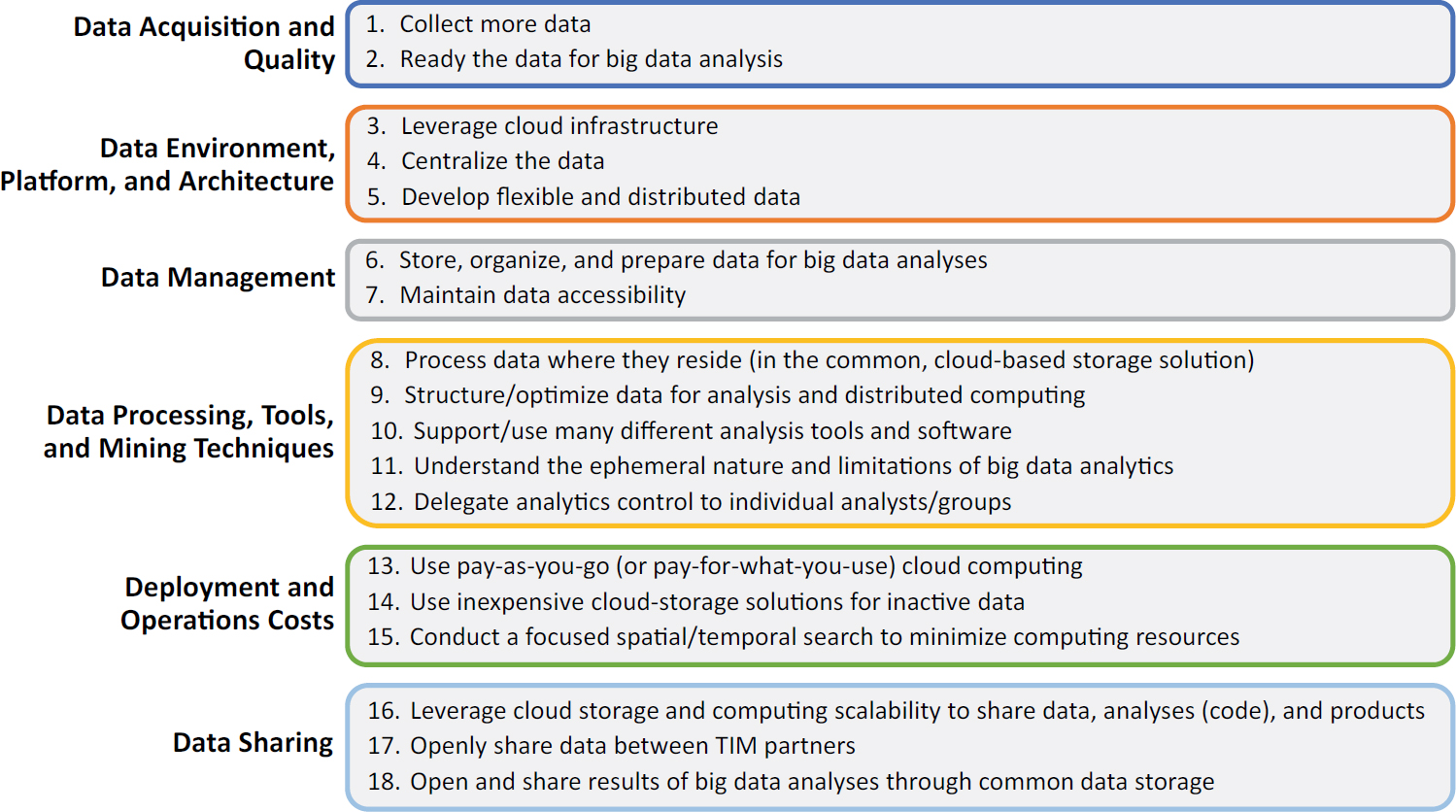

Figure 10-4 illustrates opportunities for TIM agencies to accelerate the collection, sharing, and use of data to improve TIM practices, policies, and performance and to reduce the overall impacts of traffic incidents on transportation networks. These opportunities include

- Leveraging existing data,

- Addressing data quality and standards,

- Taking a collaborative approach to data, and

- Adopting modern data management practices.

As seen in the figure, these opportunities are interdependent and synergistic. Leveraging existing data will require working collaboratively both internally and externally and will require agencies to address data quality and standards. Likewise, addressing data quality and standards will require collaboration with groups internal to DOTs as well as with partner agencies. At the center of these efforts is the opportunity to leverage modern data management practices that will facilitate the sharing of existing data, improvements in data quality, and further collaboration. This section addresses each of these opportunities individually.

Leverage Existing Data

There are numerous sources for TIM data that could be leveraged to enhance incident management. FHWA’s report on sources of traffic incident data (Klaver and Gray forthcoming) examined various sources of TIM data. State DOTs and TIM programs may consider the following existing data sources, which could provide immediate opportunities for TIM:

- Data systems for state traffic records: Data systems for state traffic records include crash, vehicle, driver, roadway, citation/adjudication, and EMS/injury surveillance. These data offer potential, as they are collected by all states and include many of the data elements needed on incidents (e.g., crashes, citations, roadway, driver, vehicle). As states improve their traffic records data systems and move toward real-time data exchange, opportunities exist to leverage these data in support of traffic incident identification and analysis that could reduce the burden of manual data collection (e.g., collecting detailed driver and vehicle data on crash reports), reduce the collection of redundant data, and improve data quality. The Traffic Records Program Assessment Advisory, 2018 Edition asserts that states should maintain a traffic records system that “supports the data-driven, science-based decision-making necessary to identify problems; develop, deploy, and evaluate countermeasures; and efficiently allocate resources” (NHTSA 2018). This advisory describes the contents, capabilities, and data quality of an effective traffic records system that supports high-quality decisions and leads to cost-effective improvements in highway and traffic safety. The benefit for states that align with the ideal traffic records system described in the advisory would be to ensure that complete, accurate, and timely traffic safety data are collected, analyzed, and made available for decision-making.

- AVL system data: Most public safety and private responders, such as EMS and towing, have fleet vehicles equipped with AVL. AVL technology provides the geolocation of fleet vehicles,

- including the associated timestamps of the geolocation information. These systems automatically capture who responds to traffic incidents, including incident scene arrival and departure times. These data could contribute to understanding response activities and timelines without manual collection of this information, which is often estimated and rounded, if collected at all.

- Waze data: Waze is a third-party data source that provides a national, standardized, and free source of data on various traffic disruptions (e.g., crashes, incidents, work zones) on all types of roads across all hours of the day. Given the gaps in incident data and the challenges associated with integrating data from many different and varied sources, Waze becomes an interesting option. Waze is currently the best source of national, real-time data on all kinds of traffic incidents. While many transportation agencies make use of Waze data for various applications (mostly incident detection), there are additional opportunities to leverage Waze data, particularly to integrate Waze data with other real-time datasets, such as probe vehicle and CAD data, to get a more complete picture of the incident response timeline and associated operational and safety impacts of incidents.

Address Data Quality and Standards

Sharing and integrating TIM data require addressing different standards used across response disciplines and variations in data quality in terms of completeness, accuracy, conformity, consistency, integrability, and timeliness. To effectively integrate disparate data sources, common data elements, expressed using the same format or standards, must be present. This applies to temporal and geospatial elements as well as to incident categories and response activities. TIM partners should conduct comprehensive data inventories, identify commonalities and differences among the data and data quality issues, establish data quality processes and targets, and discuss ways to harmonize the data to improve data sharing and integration.

The U.S. DOT is working to develop data exchanges aimed at managing disruptions to roadway operations. The U.S. DOT intends to develop the data exchanges by using a model like the open and iterative specification development model of the WZDx specification. Incident management will be the focus of one of these data exchanges. A national TIM data exchange would provide an open data system to allow agencies to share TIM data more readily for operations, planning, and assessment (NOCoE 2024).

Take a Collaborative Approach to Data

TIM requires collaborative efforts among responding disciplines and agencies, and this collaborative approach should be extended to the use of data to improve TIM practices and policies. A collaborative approach requires that the stakeholders work together to identify shared interests and data needs and to build on these common interests to address data-sharing challenges and enhance opportunities. A collaborative approach requires that agencies and business areas overcome their traditional institutional and cultural barriers to share data that have long been siloed for their exclusive efforts, develop common data formats that facilitate data integration, and protect or obfuscate sensitive data without locking down complete datasets. The sharing and integration of ATMS and CAD data is an example of how agencies have overcome cultural, mission, and system differences, as well as legal limitations on data sharing, through strong collaboration and shared interests and is a success story that TIM partners should leverage and build upon in future data collaboration efforts.

State DOTs need to continue to explore opportunities to work collaboratively with their law enforcement, fire and rescue, EMS, and towing and rescue partners to find ways to break down silos associated with the collection, sharing, and use of data to improve TIM practices and policies.

Adopt Modern Data Management Practices

A collaborative approach goes hand in hand with the modern approach to data management. Adopting a modern approach to data management requires agencies to shift the way they have traditionally thought about data. Shifting from traditional data management (e.g., relational database management systems) to modern data management approaches could help TIM agencies improve the sharing, quality, and management of relevant datasets by storing, accessing, and analyzing disparate data across TIM partner agencies. Furthermore, the bigger and more complex datasets become, the bigger the challenges and the opportunities for TIM agencies. Modern data management approaches would allow transportation and partner agencies to contribute to and leverage a common data environment (i.e., the cloud), create and share data pipelines and products (e.g., dashboards) for a wide range of TIM use cases, and leverage the data pipelines and products created by partner agencies to improve upon them and add value.

Moving from traditional relational databases to a centralized data store in a cloud environment requires technical, institutional, and cultural shifts in the way agencies manage data. The modern approach to data management presents substantial changes from the way most transportation agencies have operated traditionally. State DOTs need to build organizational capability and knowledge to effectively share, manage, and use data from a wide range of data sources to improve TIM.

References

Burgess, L., Garinger, A., and Carrick, G. (2021). Integrating Computer-Aided Dispatch Data with Traffic Management Centers. FHWA-HOP-20-064. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Transportation, FHWA. https://ops.fhwa.dot.gov/publications/fhwahop20064/index.htm#toc.

Carson, L. J., and Brydia, E. R. (2011). Traffic Incident Management Performance Metric Adoption Campaign. FHWA-HOP-10-009. Washington, DC: FHWA, United States Department of Transportation. https://ops.fhwa.dot.gov/publications/fhwahop10009/tim_fsi.htm.

FEMA. (n.d.). National Fire Incident Reporting System. Retrieved April 3, 2023, from https://www.usfa.fema.gov/nfirs/.

FHWA. (2019). Every Day Counts: An Innovation Partnership with States. EDC-4 Final Report. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Transportation. https://www.fhwa.dot.gov/innovation/everydaycounts/reports/edc4_final/.

FHWA. (2020). Innovation of the Month: Advanced Geotechnical Methods in Exploration (A-GaME). EDC News. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Justice. https://www.fhwa.dot.gov/innovation/everydaycounts/edcnews/20201029.cfm.

FHWA. (n.d.-a). Crowdsourcing for Advancing Operations. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Justice. https://www.fhwa.dot.gov/innovation/everydaycounts/edc_6/crowdsourcing.cfm.

FHWA. (n.d.-b). Traffic Incident Management. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Justice. https://ops.fhwa.dot.gov/tim/.

FHWA. (n.d.-c). Weather Data Environment. U.S. Department of Transportation. Retrieved March 30, 2023, from https://wxde.fhwa.dot.gov/.

ITE (Institute of Transportation Engineers) and Pat Noyes & Associates. (2020). TMC-PSAP Data Integration. https://www.ite.org/technical-resources/topics/transportation-system-management-and-operations/transportation-safety-advancement-group/products/tmc-psap-data-integration-white-paper/.

Klaver, K., and Gray, C. (forthcoming). Advancing Analytics and Reporting of Traffic Incident Management (TIM) Data—TIM Data Status Maps. FHWA-HOP-23-031. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Transportation, FHWA.

Klaver, K., Pecheux, B. B., Carrick, G., Smith, K., and Liu, O. Y. (2023). NCHRP Research Report 1071: Application of Big Data Approaches for Traffic Incident Management. Washington, DC: Transportation Research Board. https://doi.org/10.17226/27300.

NEMSIS. (n.d.). National Emergency Medical Services Information System. Retrieved April 3, 2023, from https://nemsis.org/.

NHTSA (National Highway Traffic Safety Administration). (2018). Traffic Records Program Assessment Advisory, 2018 Edition. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Transportation. Retrieved April 6, 2023, from https://crashstats.nhtsa.dot.gov/Api/Public/Publication/812601.

NOAA (National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration). (n.d.). Road Weather Information System (RWIS) & Clarus. NCEP Central Operations. Retrieved April 3, 2023, from https://madis.ncep.noaa.gov/madis_rwis_clarus.shtml.

NOCoE (National Operations Center of Excellence). (2024). Work Zone Management and TSMO Peer Exchange Report. Washington, DC: National Operations Center of Excellence. https://transportationops.org/system/files/uploaded_files/2024-04/NOCoE%20Work%20Zone%20Management%20and%20TSMO%20Peer%20Exchange%20Report.pdf.

Owens, D. N., Armstrong, H. A., Mitchell, C., and Brewster, R. (2009). Federal Highway Administration Focus States Initiative: Traffic Incident Management Performance Measures—Final Report. Washington, DC: United States Department of Transportation. Retrieved April 3, 2019, from https://ops.fhwa.dot.gov/publications/fhwahop10010/fhwahop10010.pdf.

Pecheux, K. K. (2016). Process for Establishing, Implementing, and Institutionalizing a Traffic Incident Management Performance Measurement Program. Washington, DC: United States Department of Transportation. https://ops.fhwa.dot.gov/publications/fhwahop15028/fhwahop15028.pdf.

Pecheux, K. K., Holzbach, J., and Brydia, R. E. (2014). Guidance for Implementation of Traffic Incident Management Performance Measurement. Final Guidebook, NCHRP Project 07-20, Applied Engineering Management Corporation, Herndon, VA. https://apps.trb.org/cmsfeed/TRBNetProjectDisplay.asp?ProjectID=3160.

Pecheux, K. K., Pecheux, B. B., and Carrick, G. (2019). NCHRP Research Report 904: Leveraging Big Data to Improve Traffic Incident Management. Washington, DC: Transportation Research Board. http://www.trb.org/Main/Blurbs/179756.aspx.

Pecheux, K. K., Pecheux, B. B., Ledbetter, G., and Lambert, C. (2020a). NCHRP Research Report 952: Guidebook for Managing Data from Emerging Technologies for Transportation. Washington, DC: Transportation Research Board. https://www.trb.org/Publications/Blurbs/180826.aspx.

Pecheux, K. K., Pecheux, B. B., Ledbetter, G., Schneeberger, J. D., Hicks, J., Campbell, M., and Burkhard, B. (2020b). NCHRP Web-Only Document 282: Framework for Managing Data from Emerging Transportation Technologies to Support Decision-Making. Washington, D.C.: Transportation Research Board, Retrieved April 6, 2023, from https://www.trb.org/main/blurbs/181365.aspx.

Pecheux, K. K., Carrick, G., and Pecheux, B. B. (2023). Secondary Crash Research: A Multistate Analysis. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Department of Transportation, FHWA. https://ops.fhwa.dot.gov/publications/fhwahop23043/fhwahop23043.pdf.

Pecheux, K. K., Carrick, G., Rista, E., Pecheux, B. B., Grabbe, B., and Porter, R. (2024). Assessment of Data Sources for First Responder Struck-By Crashes. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Transportation, FHWA. https://highways.dot.gov/media/56731.

Stedman, C. (n.d.-a). What Is Data Architecture? A Data Management Blueprint. TechTarget. Retrieved March 27, 2023, from https://www.techtarget.com/searchdatamanagement/definition/What-is-data-architecture-A-data-management-blueprint.

Stedman, C. (n.d.-b). What Is Data Governance and Why Does It Matter? TechTarget. https://www.techtarget.com/searchdatamanagement/definition/data-governance.

U.S. DOT. (n.d.). ITS Joint Program Office. Retrieved March 29, 2023, from https://www.its.dot.gov/research_archives/clarus/index.htm.