Data Integration, Sharing, and Management for Transportation Planning and Traffic Operations (2025)

Chapter: 12 Shared Mobility Data: A Resource Guide

CHAPTER 12

Shared Mobility Data: A Resource Guide

Introduction

This chapter provides readers with an overview of the public-sector applications of shared mobility data and directs them to information sources where additional detailed information can be found on specific topics of interest. It includes summaries of relevant literature and online documents; sample documents and agreements relating to provision, management, and sharing of shared mobility data; relevant data standards and open-source software related to these standards; organizations that are active in these topic areas; and examples of public datasets and dashboards provided by public agencies across the country.

Background

Shared mobility is “the shared use of a vehicle, motorcycle, scooter, bicycle, or other travel mode; it provides users with short-term access to a travel mode on an as-needed basis” (SAE J3163_201809). Its scope includes micromobility services such as bikesharing and electric scooter services, as well as car sharing, microtransit, paratransit, transportation network companies (TNCs), and traditional ride-hailing (taxi) services.

Shared mobility services have grown rapidly within just a few years. They help solve the last mile problem by providing links to and from mass transit stations and can replace car trips. They also may substitute for walking and transit trips. Some shared services can address longer trips, such as the use of microtransit, where there is insufficient demand for efficient use of fixed route transit, or car-sharing services, for occasional or periodic trips where a car is desirable.

When available, public agencies use the data from these providers for operations, planning and analysis, and enforcement. Operations applications include evaluating performance and deal with subjects such as vehicle utilization, vehicle caps, prohibited zones for operations or parking, and identifying areas that may be under- or overserved. Planning and analysis applications examine how the service fits into the larger transportation ecosystem and include using data to understand demand patterns for shared mobility, what physical infrastructure is being used (e.g., for parking), what routes are being taken (and, hence, where new bicycle infrastructure might be suitable), what the right price for curb space is, and the relationship with transit stations. Enforcement activities involve monitoring and auditing provider operations to ensure that both mobility providers and their customers are complying with established regulations. Specific activities may include determining whether service providers are accurately reflecting the status of their fleets, how well providers are rebalancing and maintaining their fleets, and when and where people are riding scooters in prohibited areas. In addition, there are topics of interest that cut across these application areas. Crosscutting topics include data sharing policies and practices (including privacy protection), the use of third parties for data management and analysis, and topics closely related to shared mobility, such as curb management.

Just as some cities were taken by surprise by TNCs and struggled to put in place regulatory frameworks, many localities have had the same experience with dockless bikes and scooters. There is a clear need for public agencies to have data to better understand how all these services fit into the overall transportation network. However, there is tension between public agencies and service providers over the sharing of data. Shared mobility providers possess proprietary data as well as personally identifiable information (PII) relating to their customers. They understandably wish to protect these data. At the same time, the public sector needs some of the data in sufficient detail and with sufficient timeliness to fulfill its operations, planning, and enforcement functions. This has created tension and a lack of trust. There is a need for model data governance agreements, adequate protection of proprietary and personal data, and a better understanding of needs and issues between the public and private sectors to increase trust.

There is also a variation in the amount of standardization and data sharing across the many shared mobility modes. For example, the General Bikeshare Feed Specification (GBFS) (NABSA n.d.) and the Mobility Data Specification (MDS) (OMF n.d.-d) provide a fairly comprehensive, widely used standard for micromobility data, but no similar standards yet exist for TNCs or other shared mobility services. State and local data-reporting laws are often also very different for micromobility and TNC operators.

Purpose and Intended Audience

The purpose of this chapter is to provide public-sector agencies with a curated guide to resources to help them plan for, manage, and utilize shared mobility data. The guide is intended not to be a comprehensive encyclopedia, but rather to provide an overview on the data management needs related to each topic and provide readers with summaries of resources where more detailed guidance and reference information can be found. The content of each resource is categorized and summarized to enable readers to determine those that best address their specific issues.

The primary intended audience includes management and staff of public agencies responsible for shared mobility, including those that use data for regulating shared mobility operations and those who use this type of data for broader planning purposes, such as implementing bike lanes or integrating shared mobility with transit operations. Both agencies that are taking on the challenge of internally managing shared mobility data and those looking to contract these services out to a third party will find material to assist them.

Scope and Organization

The organization of this chapter is intended to help readers easily locate the specific sections relevant to their topics of interest. More than 40 resources on data management are summarized in this chapter. Some of the summaries also list additional related resources. The bulk of the resources deal with micromobility; however, many of these have information or recommendations that are equally applicable to other shared mobility services, such as TNCs, ride hailing, and microtransit. The following topic areas are covered:

- Applications:

- Operations,

- Planning and analysis, and

- Enforcement.

- Crosscutting practices:

- Data sharing policies and practices,

- Use of third parties for data management,

- Communicating with the public, and

- Curb management.

The next section of the chapter discusses each of the seven topic areas, and the discussion of each topic area is accompanied by a table that lists all the resources for that topic by type of resource. The section on topic areas is followed by the catalog of resources, the primary section of the guide. The resources are organized according to type, as follows:

- Literature or online resource,

- Sample document or agreement,

- Standards effort or software tool (grouped together because standards efforts almost always include software tools that support their implementation and use),

- Organization, or

- Dataset.

For each resource, the following information is given: title, author (if applicable), type of resource, where to obtain it, topic areas covered, a short summary of the content, and a more detailed description. In some cases, links to additional closely related resources are also provided.

The references cited are listed at the end of the chapter.

Topics

This section provides a summary of each topic and a cross-reference to the resources that contain information on each topic. The two broad topic categories are applications, which are the primary reason the data are needed and why they are analyzed, and crosscutting practices.

Applications

Applications can be further divided into operations, planning and analysis, and enforcement.

Operations

This application topic deals with the day-to-day operations of shared mobility services, which include monitoring and managing the total number of vehicles in operation and vehicle utilization and identifying under- or overserved areas. Operational questions that an agency might seek to answer include the following:

- How does the driver pay rate change on the basis of trip type, location, and time of day?

- Where/when are there clusters of vehicles? (Vehicles, particularly micromobility vehicles, are sometimes referred to as “devices” in the literature. The term “vehicle” is used throughout this guide to refer to all types of shared mobility vehicles and devices, both powered and unpowered, ranging from bicycles and e-scooters to shared automobiles and microtransit vehicles.)

- When/where are there not enough vehicles in an area? When/where are there too many?

- How many vehicles are on the street but unavailable because of a maintenance issue or low battery?

- Which parts of the city are served by ride-hail services and micromobility?

- Were dockless micromobility or ride-hail vehicles involved in crashes?

The data that are needed include

- The total number of vehicles deployed as well as in-use by each operator,

- The distribution of vehicles by geographic area and by time,

- The number of trips taken per vehicle per day and their origins and destinations,

- Accident reports, and

- Surveys of user satisfaction.

In addition to collecting data from service providers, public agencies also need to provide data to service providers. Especially with regard to dynamic information, there is a benefit to standardizing and automating this information flow, and the MDS is one standard that addresses this need. The types of information that may flow from agencies to service providers include

- Areas where usage is forbidden,

- No-parking areas,

- Areas with reduced speed regulations,

- Preferred parking locations, and

- Temporary rules to address both planned and unplanned events, as well as emergencies.

However, apart from MDS, there is little other material addressing the information flows from public agencies, and most of the references in this guide deal only with information coming from service providers.

Resources for the topic of operations are indexed by type in Table 12-1.

Planning and Analysis

This topic deals with issues that are more long term than daily operations as well as broader topics, such as transportation planning, overall impact on the streets or city, or the impact of micromobility on street design. Following are some questions that public agencies may seek to answer:

- What are the impacts on street and sidewalk safety?

- What is the impact on economic development?

- How do ride-hail services and micromobility trips relate to existing transit services?

- Which routes/streets are most used by people on shared micromobility vehicles?

Table 12-1. Resources on the topic of operations, by type of resource.

| Literature and Online Resources | Sample Documents and Agreements | Standards Efforts and Software Tools | Organizations | Datasets |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

None specific to this topic |

|

|

None specific to this topic, though some may contain data elements useful for analyzing operations |

- How efficiently are ride-hail services using the streets?

- What share of total transportation emissions and local air pollution is coming from ride-hail services?

- How do vehicle utilization and pooling relate to congestion by geography?

- How many nonrevenue vehicle miles traveled occur on the street (e.g., Lyft/Uber deadheading or rebalancing dockless micromobility vehicles)?

- What is the right price for curb space?

Data on usage, demand, and trip-level can be used to determine the location of new bike/scooter lanes and vehicle parking areas and to allocate curb usage, all of which provide value to the service providers as well as the general community. Another area of interest for most localities is the interrelationships and interactions between various shared mobility modes and public transit operations, such as the use of shared mobility to address last mile issues or the extent to which shared mobility services compete with transit for usage and ridership. These types of analyses can help service providers demonstrate the value that they are providing to the community.

Along with other data sources, the specific types of data from mobility providers that might be needed include time-dependent origin–destination data, routes taken, trip duration, number of vehicles by service type and status within specified geographic and time boundaries, number of trips taken per vehicle per day, and parking area usage.

Resources for planning and analysis are indexed by type in Table 12-2.

Enforcement

These types of applications include enforcing both service provider and user compliance with regulations. The two are interrelated, as enforcement policies may hold the service provider

Table 12-2. Resources on the topic of planning and analysis, by type of resource.

| Literature and Online Resources | Sample Documents and Agreements | Standards Efforts and Software Tools | Organizations | Datasets |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

None specific to this topic |

|

|

None specific to this topic |

responsible for the actions of its users. These policies may include regulations related to operations in restricted areas, speed violations, parking or riding on sidewalks, and restricted hours of operation.

This topic also includes information needed to calculate any fees due from operators, which may be based on the number of vehicles deployed, the number in use per day, or other criteria.

Another important aspect of enforcement and fee collection is verifying the accuracy of provider data with independently measured ground truth data to identify and resolve discrepancies. This can include using check rides, independent observations, and data auditing tools.

Resources for enforcement are indexed by type in Table 12-3.

Crosscutting Practices

Crosscutting practices discussed in this section include the following:

- Data sharing policies and practices,

- Use of third parties for data management,

- Communicating with the public, and

- Curb management.

Data Sharing Policies and Practices

This topic deals with data sharing agreements and policies that public agencies put in place for getting data from shared mobility providers and storing and using that data as well as how private and proprietary data will be protected. In some cases, the requirements are included in operating agreements, permits, or licenses, while in other cases they are separate documents incorporated by reference. They may cover items such as what data must be reported, how frequently, and in what format(s); allowed uses for the data; who owns the data; and requirements for privacy protection.

Most of the material available in this area addresses micromobility services rather than other forms of shared mobility such as TNCs. This came about for a combination of reasons. First, micromobility services came later, and, by that time, cities were better prepared and had a better understanding of what information they needed as well as the legal structures to insist that it be provided. In addition, at the urging of TNCs, several states preempted the ability of local

Table 12-3. Resources for the topic of enforcement, by type of resource.

| Literature and Online Resources | Sample Documents and Agreements | Standards Efforts and Software Tools | Organizations | Datasets |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

None specific to this topic |

|

|

None specific to this topic, though some may contain data elements useful for enforcement |

governments to collect data from TNCs. Despite this, TNCs and traditional ride-hailing (taxi) operators may have similar data sharing requirements. For example, Seattle specifies the data that must be collected by taxicab associations, for-hire vehicle companies, and TNCs. The regulations cover what data must be collected, the data retention requirements (2 years), and the reporting requirements (quarterly) (City of Seattle, WA n.d.). Similarly, the California Public Utilities Commission lays out annual reporting requirements for TNCs (California Public Utilities Commission n.d.) and the New York City Taxi and Limousine Commission (TLC) requires regular reporting by both TNCs and ride-hailing companies (New York City TLC n.d.).

Resources for data sharing policies and practices are indexed by type in Table 12-4.

Use of Third Parties for Data Management

This topic is closely related to and overlaps with data sharing policies and practices but is distinct enough to warrant being called out into a separate topic. Third parties are hired by the public agency. They have experience working in multiple cities and with multiple service providers, which enables them to often have a better understanding of the issues relating to data than a public agency. These third parties can audit data provided by operators and ensure that consistent definitions are used for reporting. The use of third parties to obtain, store, and analyze shared mobility data is also one method for resolving the tensions between providing information that is adequate for public agencies to perform their functions while ensuring adequate protection of private and proprietary information.

Public agencies have a legitimate need for data to effectively plan their transportation systems, to develop regulations for the best use of shared mobility, and to enforce those regulations. Some of this analysis requires the use of the type of trip-specific information that raises privacy concerns. At the same time, the collection, storage, and use of such data by public agencies raises multiple legitimate concerns. Some agencies, especially smaller ones, may simply lack the specific skills and resources needed to effectively manage and analyze the large volumes of data. In addition, some datasets, such as trip-specific data, raise privacy concerns that require special handling, for which requirements sometimes come into conflict with existing state freedom-of-information laws. This occurs because, although location-specific data are not considered (PII), such data can often be combined with other public data to enable re-identification and, thereby, reveal sensitive information about individual activities. Some existing state laws do not adequately protect such data from Freedom-of-Information Act (FOIA) requests or other types of disclosure. Finally, the mobility providers themselves are rightfully protective of their proprietary data as well as their customers’ privacy and see risks with sharing data with public-sector agencies, since disclosure to competitors could harm their business. Care must be taken even with aggregate data to ensure that they cannot be disaggregated (e.g., if there are only two providers for a given service type).

One approach for dealing with these issues is for an agency to contract with a trusted third party to manage and analyze the data. These third parties receive raw data from mobility providers but do not provide the raw data to government agencies or to any other organizations. They securely store whatever data need to be kept and conduct the analyses that public agencies need to manage mobility providers. The public agencies receive the results of the analyses along with anonymous aggregated data. There are currently nonprofit universities and private for-profit corporations providing these services.

Resources for the use of third parties for data management are indexed by type in Table 12-5.

Communicating with the Public

This topic covers the use of information to communicate with the public as well as elected government officials, community groups, and researchers. This communication may include

Table 12-4. Resources for the topic of data sharing policies and practices, by type of resource.

| Literature and Online Resources | Sample Documents and Agreements | Standards Efforts and Software Tools | Organizations | Datasets |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

Table 12-5. Resources for the topic of use of third parties for data management, by type of resource.

| Literature and Online Resources | Sample Documents and Agreements | Standards Efforts and Software Tools | Organizations | Datasets |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

None | While standards and tools may be used by public and private agencies, none that relate specifically to the interface between public agencies and third parties providing data management as a service |

|

None that relate specifically to the exchange of data between public agencies and third parties providing data management as a service |

publishing real-time availability data for various services as well as providing aggregated data, dashboards, and reports that show how shared mobility services are being used throughout the jurisdiction. This topic also includes collecting, investigating, and resolving resident complaints related to operations, parking, speeding, and so forth and may include the use of user surveys to collect information from the public.

Resources for communicating with the public are indexed by type in Table 12-6.

Curb Management

Curb management and the geotagged digitization of curb usage and regulations is a topic of growing importance for towns and cities. Its applications are far broader than shared mobility, but, because of its important role within shared mobility, it has been included as a topic.

Table 12-6. Resources for the topic of communicating with the public, by type of resource.

| Literature and Online Resources | Sample Documents and Agreements | Standards Efforts and Software Tools | Organizations | Datasets |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

None specific to this topic |

|

|

|

Table 12-7. Resources for the topic of curb management, by type of resource.

| Literature and Online Resources | Sample Documents and Agreements | Standards Efforts and Software Tools | Organizations | Datasets |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

None specific to this topic |

|

|

None specific to this topic |

Curb space is a limited resource with increasing demands for use as pick-up and drop-off space for both people and goods, scooter corrals, and other uses. Multiple communities are digitizing the data associated with curb rules as well as fees that some communities are beginning to charge for curb access. The data include the georeferenced rules and regulations applying to various sections of curb in a municipality, as well as to pricing of curb access, whether for parking, pick-up and drop-off, or the delivery of freight.

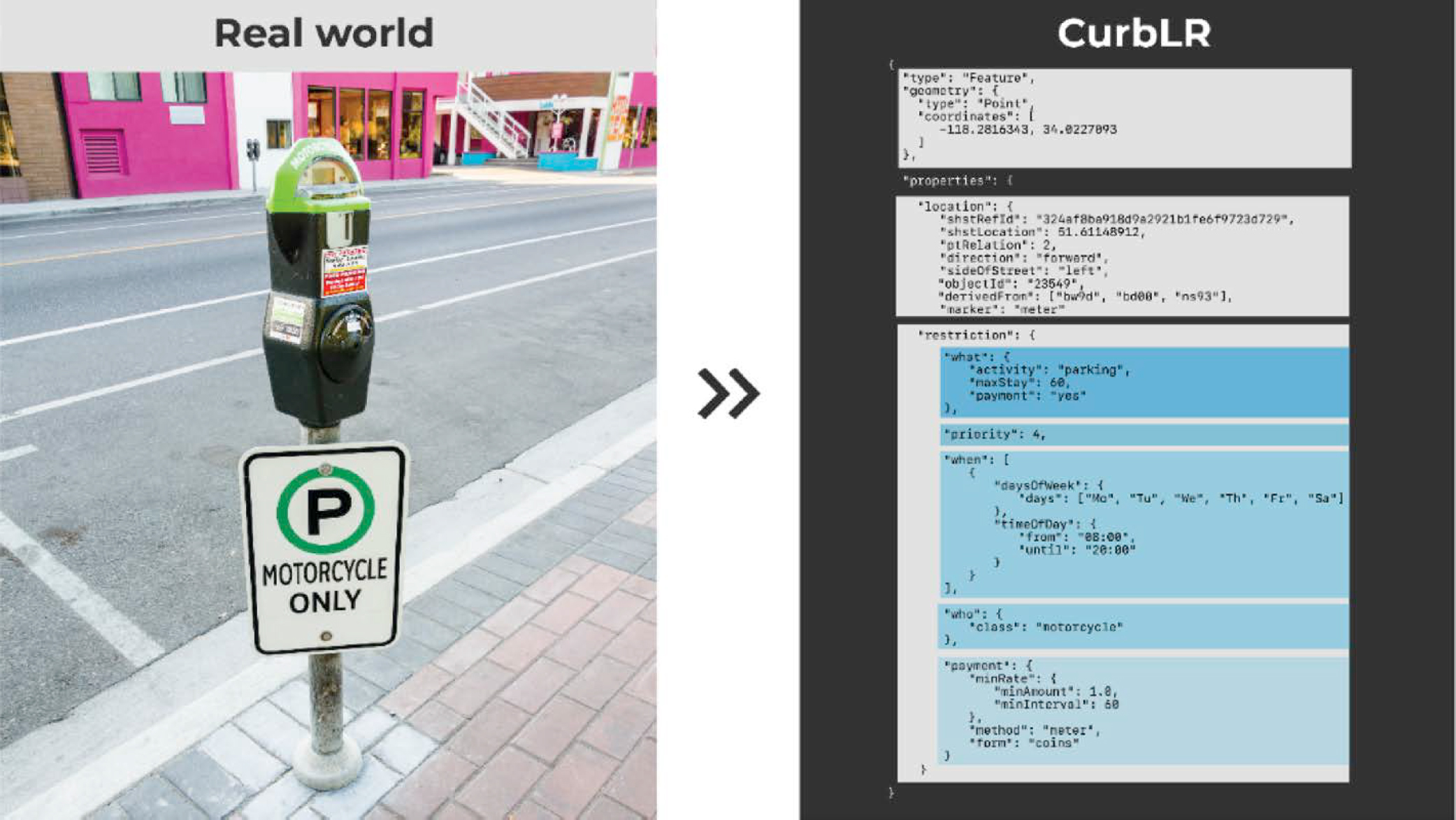

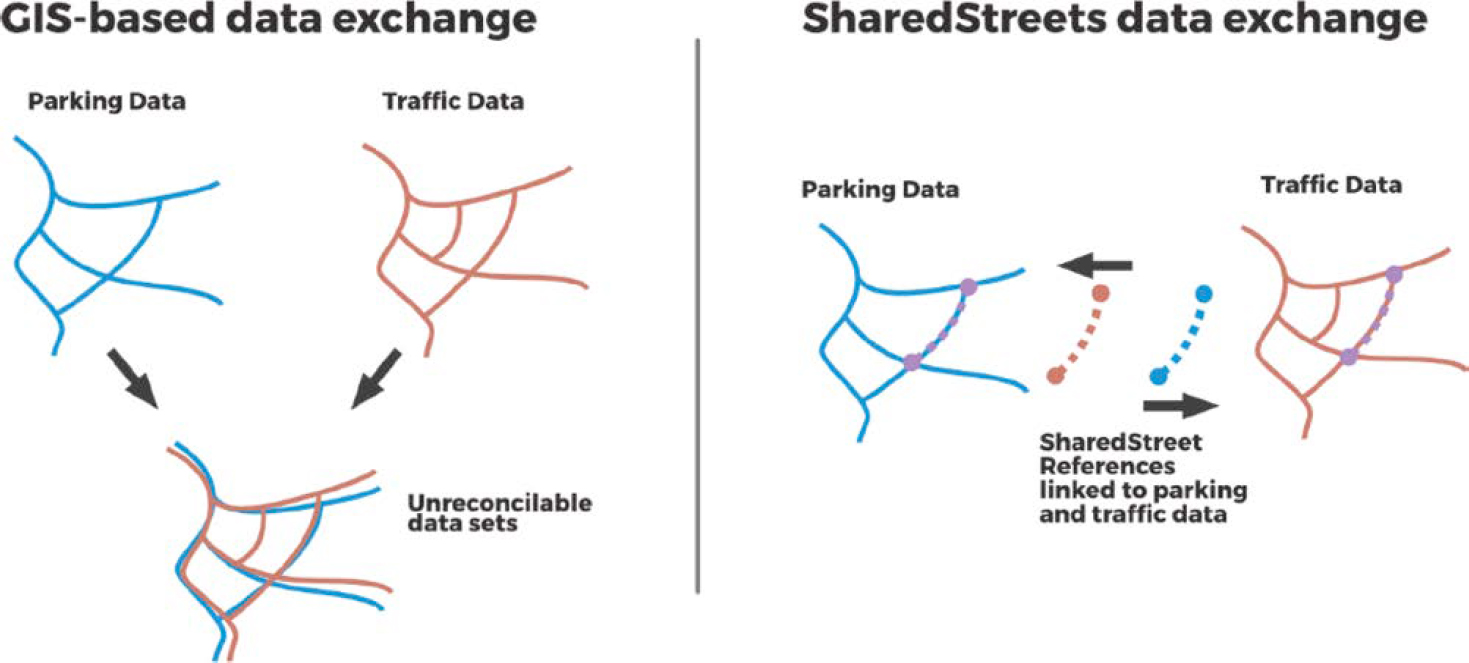

One example is Los Angeles’ Code the Curb initiative, which was launched in 2016 (LADOT n.d.). Code the Curb provides a digital, geocoded reference for all the city’s traffic signs, painted curbs, and other regulatory tools. Private-sector and nonprofit entities are also working in this area. SharedStreets, for example, has created CurbLR, a proposed standard for describing curb regulations such as those in the Code the Curb initiative (SharedStreets n.d.-a). Safari AI works with public agencies and delivery operators to better manage, coordinate, and schedule curb access (Safari AI 2024). The Open Mobility Foundation has also begun to look at developing a common specification as part of the MDS for digitized curb data and is coordinating with SharedStreets (OMF 2020a), among numerous other public agency and private-sector stakeholders.

Resources for curb management are indexed by type in Table 12-7.

Resources

This section provides a short description of each resource, including its title and author, the type of resource, where to obtain it, and the topic areas covered, and a short summary of the content. In some cases, information on additional related resources is also provided.

Literature and Online Resources

This section catalogs articles and websites on shared mobility data management. The resources, which range from short articles or summaries to extensive guides, are as follows:

- A Practical City Guide to Mobility Data Licensing

- Mobility Brief #2: Micromobility Data Policies: A Survey of City Needs

- Data Sharing Glossary and Metrics for Shared Micromobility

- Guidelines for Mobility Data Sharing Governance and Contracting

- Privacy Guide for Cities

- Mobility Data State of Practice

- Leveraging Data to Achieve Policy Outcomes

- Urgent Privacy Concerns with City’s Decision to Collect Traveler Mobility Location Information

- Civic Analytics Network Dockless Mobility Open Letter

- Brief for Justin Sanchez and Eric Alejo v. Los Angeles Department of Transportation and the City of Los Angeles

- Objective-Driven Data Sharing for Transit Agencies in Mobility Partnerships

- Mobility Data Methodology and Analysis

- Dockless Open Data

- Managing Mobility Data

- Shared Mobility Data: A Primer for Oregon Communities

- Shared Mobility Data Sharing: Opportunities for Public–Private Partnerships

- Protecting Rider Privacy in Micromobility Data

- Prioritizing Privacy When Using Location in Apps

- Using Micro-Mobility Data to Drive Transportation Policy Investments in Greater Boston

- Effectively Managing Connected Mobility Marketplaces

- CDS-M Use Case: From Policy Needs to Use Cases

- Charlotte Takes E-Scooter Data for a Test Ride

Resource: A Practical City Guide to Mobility Data Licensing

Author: Jascha Franklin-Hodge

Date: 2019

URL: https://medium.com/remixtemp/city-guide-to-mobility-data-licensing-71025741ae2c

Description: Short online article.

Summary: The article provides guidance, from a public agency’s perspective, on drafting data sharing agreements. Topics covered include types of licenses, considerations regarding the right to further share data, and integration with data from other sources. The author is the former chief information officer for the City of Boston and is currently the executive director of the Open Mobility Foundation.

Topic Area(s):

Data Sharing Policies and Practices

Use of Third Parties for Data Management

Resource Type:

Literature or Online Resource

The article does not provide specific language for agreements; rather, it provides specific recommendations on what should be considered for inclusion in any agreement as well as what should be avoided. The information is presented on a topic-by-topic basis.

This article is an excellent resource for understanding the importance of data sharing agreements and identifying what public agencies should and should not include when drafting, reviewing, or entering into any sort of data sharing agreement with private-sector mobility providers regarding sharing mobility data.

Additional Details: The recommendations are divided into three major parts, each of which includes several focus areas. The article discusses the various types of licenses and recommends that data sharing agreements be either embedded in permit agreements or incorporated by reference. It also recommends the use of a standard agreement with all providers rather than negotiating different agreements with each provider. Other topics discussed include but are not limited to the following:

- Rights of use;

- Access to raw versus preaggregated data—ability to share data with other public agencies, third-party data management organizations, and the public;

- Integration with other datasets;

- Requirements on the public agency to adequately protect the data;

- Privacy protection;

- Relations of the data to state-level freedom-of-information laws; and

- Liability issues.

Additional Resources: An Updated Practical City Guide to Mobility Data Licensing (Zack 2019).

Resource: Mobility Brief #2: Micromobility Data Policies: A Survey of City Needs

Author: Michael Migurski

Date: 2018

URL: https://medium.com/remixtemp/micromobility-data-policy-survey-7adda2c6024d

Description: Ten-page survey of data sharing policies across multiple U.S. cities.

Summary: The author surveyed the data sharing policies of more than a dozen U.S. cities, including Nashville, TN; Chicago, IL; Santa Monica, CA; San Francisco, CA; Pittsburgh, PA; Austin, TX; and Dallas, TX. Some of these cities had pilot programs, some had postpilot operational programs, and one had an emergency data sharing rule in place.

Topic Area(s):

Data Sharing Policies and Practices

Resource Type:

Literature or Online Resource

On the basis of the survey results, the author identified four major findings:

- Universal agreement on the need for trip data and fleet availability data,

- A wide range of requirements regarding the frequency of data reporting,

- Multiple approaches for handling customer feedback information, and

- The need for formal data sharing agreements.

Note that at the time the survey was conducted, the MDS was a newly emerging standard being developed by the Los Angeles Department of Transportation (LADOT). The subsequent widespread adoption of the MDS may change some of the findings.

Additional Details: The report includes a comprehensive table of 12 cities and the types of data collected by each city (trips, fleet, customer survey, parking, maintenance, safety/incidents, and data validation). All 12 cities required trip data, and 11 of the 12 required fleet data. Only two specifically addressed data validation.

For trip and fleet data, the report provides details, walking through an overview of the findings, why the data type is important, and how it is being collected across the surveyed cities. The results for the other data types are covered more briefly. In addition, there is a good discussion on reporting frequency and the use of application programming interfaces (APIs) versus static, periodic reports. Since the report was published, the widespread adoption of the MDS makes the case for APIs even stronger than what is included in the report.

Additional Resources: None.

Resource: Data Sharing Glossary and Metrics for Shared Micromobility

Author: Mobility Data Collaborative

Date: 2020

URL: https://www.sae.org/standards/content/mdc00002202004/

Description: Glossary that “provides a consensus-based set of definitions for terms and metrics that are commonly used. It outlines key vehicle, trip, and geospatial definitions and metrics to reduce discrepancies in the terminology used across jurisdictions and sectors and allow public agencies to clarify policies related to shared micromobility.”

Topic Area(s):

Data Sharing Policies and Practices

Operations

Policy and Analysis

Resource Type:

Literature or Online Resource

Summary: The 19-page glossary focuses on vehicle and trip-level data. It provides standardized, often hierarchical, definitions of terms as well as vehicle-based and trip-based performance metrics and standardized methods for calculating these metrics.

Additional Details: The definitions are short textual descriptions in English. For example, vehicle is “a motorized or human-powered vehicle [that] could include an automobile, motorcycle, (e-)bike, e-scooter, or moped that is used for transportation.” At the highest level, a vehicle may be in “Deployed,” “Removed,” or “Unknown” status. Deployed vehicles may be “Operational” or “Non-Operational.” Operational Vehicles may be “In-Use” or “Available.” Both “Available” and “Non-Operational” vehicles are in the “Idle” state.

To fully define vehicle and trip terms, several geographic terms (e.g., “service area,” “waypoint”) and time-related terms (e.g., “available time,” “operational time”) are also defined.

The glossary then defines many vehicle and two trip-based performance metrics and presents mathematical formulas for how they should be calculated. For example, the average number of vehicles of a specified status in a specified geographic area over a specified time is given as

where

avgveh = average number of vehicles of a specified status,

vehi = number of vehicles of a specified status at i,

i = sampling frequency (e.g., time units in minutes), and

T = time of interest (i.e., total number of i samples).

Additional Resources: None.

Resource: Guidelines for Mobility Data Sharing Governance and Contracting

Author: Mobility Data Collaborative

Date: 2020

URL: https://www.sae.org/standards/content/mdc00001202004/

Description: Recommended guidelines for data sharing.

Summary: Presents recommended guidelines for data sharing that consider the goals of both public agencies and mobility service providers as well as the need to protect consumer privacy.

Topic Area(s):

Data Sharing Policies and Practices

Use of Third Parties for Data Management

Resource Type:

Literature or Online Resource

This resource is a short (10-page) document intended to be used as discussion input when specific agency policies and agreements are being formulated across disciplines (e.g., planning, legal, policy, data, and information system professionals).

Additional Details: The document lays out 10 guidelines, defines each guideline’s objective, and provides actionable recommendations to which all parties should commit. The discussion, however, is at a rather high level as opposed to including specifics. The 10 guidelines are as follows:

- Address benefits and challenges associated with mobility data sharing.

- Evaluate consumer-facing risks through standard impact assessments.

- Consider anonymization and de-identification techniques for mobility data sharing.

- Engage consumer groups in conversations about privacy and mobility data.

- Establish data governance frameworks to support mobility data sharing.

- Determine and incorporate appropriate role of third parties around management and analysis of mobility data.

- Develop a consistent approach to open records requests.

- Develop policies for compliance with law enforcement requests.

- Allocate resources for training on applicable laws and best practices for safeguarding data.

- Develop workable liability frameworks to mitigate risks.

Additional Resources: None.

Resource: Privacy Guide for Cities

Author: Open Mobility Foundation

Date: 2020

Description: Fourteen-page guide to aid cities in developing policies and procedures for managing sensitive mobility data, particularly data collected using the MDS.

Summary: While MDS data, as well as most shared mobility data collected by public agencies, contain information about vehicles rather than individuals, there are risks that these data could, in combination with other data, be used to re-identify individual users and violate their privacy. This publication provides specific recommendations on factors, policies, and techniques to consider for protecting privacy.

Topic Area(s):

Data Sharing Policies and Practices

Use of Third Parties for Data Management

Communicating with the Public

Resource Type:

Literature or Online Resource

Additional Details: After explaining why MDS and similar shared mobility data should be considered sensitive, the guide addresses five major topics, most of which are further broken down into subtopics:

- Planning Your Implementation:

- Identify Your Use Cases,

- Review Applicable Laws and Regulations,

- Assess Your Readiness,

- Consider a Mobility Data Solution Provider (MDSP), and

- Provide for Transparency;

- Managing Risk:

- Minimization,

- Retention,

- Access Controls, and

- Obfuscation and Aggregation;

- Working with Mobility Service Providers;

- Sharing MDS Data:

- Sharing Through Open Data Portals,

- Sharing with MDSPs,

- Sharing with Academic Institutions or Researchers, and

- Sharing with Other Agencies; and

- Disclosure Based on Public Records Requests.

Additional Resources: None.

Resource: Mobility Data State of Practice

Author: Open Mobility Foundation

Date Accessed: January 26, 2021

Description: Set of links to policy and technical resources relating to the handling and protection of shared mobility data.

Topic Area(s):

Data Sharing Policies and Practices

Use of Third Parties for Data Management

Communicating with the Public

Resource Type:

Literature or Online Resource

Summary: This document provides a collection of links to diverse resources organized by topic. These include samples of data licensing and policy documents from various localities, guidance and methodology guides, open-source software, risk assessment documents, open mobility datasets, guides for publishing mobility data, and data visualizations.

Additional Details: The document provides a wide-ranging categorized list of resources, some of which are included in this chapter, but many of which are not. The content ranges from sample policies [e.g., the LADOT Data Protection Principles (City of Los Angeles, CA 2019)], to sample permit requirements [e.g., Louisville, KY’s, Dockless Vehicle Policy (City of Louisville, KY n.d.-a)] to data protection methodologies [ranging from Minneapolis, MN’s mobility-specific Mobility Data Methodology and Analysis (City of Minneapolis, MN n.d.) to the National Institute of Standards and Technology’s general De-Identification of Personal Information (Garfinkle 2015)], to open source code (e.g., interface for retrieving anonymized and aggregated dockless mobility trip data, deployable reference implementation for working with MDS data, front-end for ingestion and analysis of MDS data), and more, including a half dozen open mobility datasets, guides for publishing mobility data, and examples of data visualizations. Unlike this chapter, only the source and title are identified, without any descriptions. The categories of resources are as follows:

- Privacy principles, policies, and guidelines;

- Permit and licensing requirements;

- Data sharing;

- Data processing, aggregation, and anonymization;

- Risk assessment;

- Open data;

- Data visualization; and

- Outreach and education.

Additional Resources: None.

Resource: Leveraging Data to Achieve Policy Outcomes

Author: New Urban Mobility alliance (NUMO)

Date Accessed: March 2, 2021

URL: https://policydata.numo.global/

Description: Interactive web-based tool for cities to use in evaluating micromobility services against policy goals that foster safe, sustainable, and equitable communities.

Topic Area(s):

Planning and Analysis

Operations

Enforcement

Communicating with the Public

Resource Type:

Literature or Online Resource

Summary: This document is a tool for identifying metrics addressing equity, safety, environment, and usage. It defines outcomes, metrics for each outcome, the data required for each metric, and the data source.

Additional Details: The guide covers metrics for a dozen outcomes:

- Access to necessities,

- Infrastructure,

- Operations,

- Access to platforms,

- Observation and enforcement,

- Lifespan,

- Access to vehicles,

- Vehicle condition,

- General usage,

- Safety,

- Environment, and

- Education.

For each outcome, the following is provided: a short definition; one or more questions to answer to assess the outcome measure; and evaluation, policy, and equity metrics that relate to each question. The data required for each specific metric are then identified. For example, one question under access to vehicles is “How far does the average user have to travel to find a vehicle?” A policy metric associated with that question is the “percentage distribution coverage” (total area covered by a quarter-mile radius around each vehicle divided by the total service area). A goal might be “50% coverage 75% of the time.” The data required would be

- device_id,

- event_type,

- event_location,

- service area spatial file,

- event_time,

- event_type_reason, and

- neighborhood spatial file.

All but the two spatial files are data that are specified in the MDS. The spatial data are expected to be found in a locality’s open data.

Additional Resources: Micromobility & Your City Webinar: Leveraging Data to Achieve Policy Outcomes (NUMO 2020).

Resource: Urgent Privacy Concerns with City’s Decision to Collect Traveler Mobility Location Information

Author: Center for Democracy and Technology

Date: 2020

Description: Two letters from the Center for Democracy and Technology—one to the District (Washington, DC) Department of Transportation (DDOT) and the other to the LADOT—raising privacy issues and concerns with data provided by using the MDS.

Topic Area(s):

Data Sharing Policies and Practices

Resource Type:

Literature or Online Resource

Summary: The first letter expresses concerns over DDOT’s decision to require trip reporting via MDS and to require the data to be reported in near real time. The letter references the second letter to LADOT, which goes into much more detail, with references, over the privacy concerns raised by the collection of detailed trip-level data and makes specific policy recommendations.

Additional Details: The first letter cites the U.S. Supreme Court’s finding that time-stamped location data “provides an intimate window into a person’s life, revealing not only his particular movements, but through them his ‘familial, political, professional, religious, and sexual associations.’ ” It urges DDOT to use aggregated data to meet its needs for planning data.

The second letter acknowledges LADOT’s recognition that data collected via the MDS should be classified as “confidential” data under the city’s information handling guidelines but calls on LADOT to be more specific as to how the data will be safeguarded, including data retention policies; the uses to which the data will be put; and how access will be controlled. The letter cites specific examples, with references, on how confidential location-specific data can and have been misused and explains why trip data raise serious privacy concerns. The letter then lays out specific privacy policy recommendations for the city to consider.

Additional Resources: None.

Resource: Civic Analytics Network Dockless Mobility Open Letter

Author: Civic Analytics Network

Date Accessed: December 2018

URL: https://datasmart.hks.harvard.edu/news/article/civic-analytics-network-dockless-mobility-open-letter

Description: Short letter authored by chief data officers from 13 urban municipalities laying out recommendations both on dockless mobility policies in general and data policies in particular.

Topic Area(s):

Data Sharing Policies and Practices

Use of Third Parties for Data Management.

Communicating with the Public

Resource Type:

Literature or Online Resource

Summary: The letter provides a set of recommendations for communities that are embarking on micromobility programs. It discusses the types of reporting that should be required; what types of data should be made available to the public; how privacy should be maintained through data aggregation before publishing data; and more general recommendations, such as recommendations related to equity, compliance tracking, and the use of surveys. The guidance is specific but not comprehensive.

Additional Details: Interestingly, this letter recommends against the use of third parties for data management and lists a variety of reasons for this recommendation. This recommendation runs counter to all other references included in this chapter that address the topic. All the other references recommend that this option at least be given consideration, depending upon the circumstances of the locality.

The letter includes a link to a public spreadsheet showing the various fees that cities charge providers of dockless mobility services, including per-vehicle fees, annual fees, application fees, and bonding requirements. As of February 2021, 20 communities were listed. It is not clear how up to date the spreadsheet is, but many of the rows include online links to the original sources.

The letter also recommends considering that service providers be required to distribute a city-designed survey to their users to provide insight into behavior patterns, preferences, and customer satisfaction. The survey used by Portland, OR, is linked to and recommended as a good model.

Additional Resources:

- Dockless Vehicle Fees, a spreadsheet of vehicle fees by community (Civic Analytics Network n.d.).

- 2018 E-Scooter Findings Report (City of Portland, OR 2018).

Resource: Brief for Justin Sanchez and Eric Alejo v. Los Angeles Department of Transportation and the City of Los Angeles

Authors: M. Tajsar, J. Snow, J. Lynch, D. E. Mirell, and T. J. Toohey

Date: 2020

URL: https://www.eff.org/document/sanchez-v-ladot-complaint

Description: Legal brief challenging the legality of LADOT requiring the provision of detailed, location-specific trip data from dockless mobility providers.

Topic Area(s):

Data Sharing Policies and Practices

Resource Type:

Literature or Online Resource

Summary: The brief challenges the legality of the collection of these data under the Fourth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, the California state constitution, and the California Electronic Communication Privacy Act (CalECPA).

The brief is included in this chapter because it provides an excellent, detailed discussion of the privacy concerns raised by the collection of detailed, location-specific trip data, including numerous references that further demonstrate or discuss these concerns. It is included for its comprehensive discussion of legitimate privacy issues rather than the legal arguments.

Additional Details: The legal brief explains how location-specific individual trip data can be combined with other, publicly accessible data (such as who lives at a given address or what business is at an address) to reveal both the individual who took the trip and why the trip was taken (e.g., to visit a reproductive health clinic). The brief explains that these data are sensitive regardless of whether they are collected in real time or provided after the fact.

The brief also provides examples of how such de-anonymized data can harm an individual and examples of how location information has been abused in the past, as when automatic license plate reader information was used by stalkers and domestic abusers. Citations to research and reports with additional detail are provided.

Additional Resources: In February 2021, this case was dismissed on legal grounds by the judge, who ruled that collecting MDS data did not constitute a search in legal terms and that, even if it did, it was not an unreasonable one. As of June 2021, that ruling was being appealed. See Justin Sanchez et al. v. Los Angeles Department of Transportation, et al. (Gee 2021).

Resource: Objective-Driven Data Sharing for Transit Agencies in Mobility Partnerships

Author: Shared Use Mobility Center

Date: 2019

Description: Twenty-five-page white paper intended to support the decision-making of

Topic Area(s):

Data Sharing Policies and Practices

Use of Third Parties for Data Management

Operations

Analysis

Resource Type:

Literature or Online Resource

transit agencies that are considering implementing mobility on demand (MOD) or a similar integration with private mobility service providers, with a focus on data exchange requirements.

Summary: The paper outlines the types of information transit agencies might need, depending upon the type of project and its objectives. The paper then discusses the challenges that agencies have faced in attempting to obtain the data, including concerns over privacy, proprietary data, security, level of aggregation, data needed for the National Transit Database and to support federal funding, and the limitations of the agencies’ capabilities.

The paper then presents project-level, regulatory, and legislative options for overcoming these challenges. It includes a decision tree to aid agencies with sequential decision-making to determine the best approaches based on project type, project objectives, and constraints.

Additional Details: The paper states that reaching data sharing agreements between the public and private partners was one of the primary challenges of projects under FTA’s MOD Sandbox Program (FTA n.d.). Throughout the paper, specific MOD Sandbox projects are discussed as examples of data needs, challenges, and solutions. Much of the content is based on lessons learned from the MOD Sandbox Program.

The decision tree at the end of the paper addresses two types of projects: MOD service projects and Multimodal Trip Planning App (Smart Columbus n.d.) projects. Project- and policy-level decisions are identified in the tree, and the advantages and disadvantages of each decision are presented in a table. Decisions include whether to pursue modernizing public record laws, whether to manage data in-house versus by using a third party, and whether to establish a common API or pursue individual API agreements with each service provider.

Additional Resources: Webinar: Objective-Driven Data Sharing for Transit Agencies in Mobility Partnerships (Shared-Use Mobility Center 2019).

Resource: Mobility Data Methodology and Analysis

Author: City of Minneapolis, MN

Date Accessed: October 2018

URL: https://www2.minneapolismn.gov/media/content-assets/www2-documents/departments/wcmsp-218311.pdf

Description: Short (seven pages) but detailed description of the methodology followed by Minnesota to manage and analyze data collected as part of a motorized scooter pilot program that ran from July through November 2018.

Topic Area(s):

Data Sharing Policies and Practices

Resource Type:

Literature or Online Resource

Summary: The focus is on how the state protected privacy and minimized any potential use or release of sensitive information through anonymization and aggregation. The license agreements between the city and scooter operators prohibited the city from obtaining any PII and required service providers to put good security practices in place to protect any PII that they collected as part of their operations. The agreements also laid out the city’s purpose in collecting the data, how the data were to be provided, what data the city would make publicly available, and what data each provider had to make available to the public.

Although no PII data were collected by the city, location-specific trip-level data were collected, and these data are potentially re-identifiable. The report describes the methods used by the city to minimize this possibility.

The methodology was developed to be consistent with the Minnesota Government Data Practices Act (Gehring 2010).

Additional Details: The city used a Python front end and a Microsoft SQL server to consume and store the data. Server access was restricted, as was access to the API authorization tokens. Python, R, and Tableau were used for analysis and visualizations.

The paper describes seven techniques that were used to anonymize the data, including the following:

- Python was used to process all incoming API data in memory. Only anonymized data, no raw data, were stored.

- The trip IDs sent from the MDS, while already hashed into a unique value intended for anonymization, were discarded, and a new ID was generated to make it more difficult to link back to the providers’ data.

- Trip times and locations were binned and the original trip times and locations discarded.

The report describes several specific issues that arose, such as differing interpretations of standards, the absence of historical data in the GBFS (the project did not initially use the MDS), and bad data. The project used only GBFS data in the beginning. The MDS standard became available midway through the project, and this was incorporated into the data-reporting requirements. The specific MDS and GBFS data fields used in the pilot are provided and discussed in the two appendices to the document.

Additional Resources: None.

Resource: Dockless Open Data

Author: City of Louisville, KY

Date Accessed: February 3, 2021

URL: https://github.com/louisvillemetro-innovation/dockless-open-data

Description: Short technical guide covering “how and why cities can convert MDS trip data to anonymized open data, while respecting rider privacy.”

Topic Area(s):

Data Sharing Policies and Practices

Communicating with the Public

Resource Type:

Literature or Online Resource

Summary: The MDS standard does not support collecting PII; however, it does support collecting detailed trip data that could potentially be combined with other data to re-identify individuals. This guide describes a method for ensuring data collected using the MDS is sufficiently anonymized so that it cannot be used for this purpose. The resulting datasets can be published or released via open data requests without fear that individuals can be identified from the data.

Additional Details: Trip start and end time data are binned into 15-minute increments. The geographic location data are both binned and fuzzed. The data are first binned by truncating the latitude and longitude data to three decimal places. The data are then fuzzed using a k-anonymity generalization function that groups multiple similar trips together and replaces their individual origins and destinations with the prototypical origin and destination for that group. This fuzzing is only done for trips for which fewer than five trips were made between the origin and destination bin pair. The entire process is described in detail, with SQL and other sample code provided and described. The processed data can be seen on Louisville’s public dashboard (City of Louisville, KY n.d.-b). The guide also provides links to open data from six other localities and a general description of how each anonymizes its published data.

Additional Resources:

- Louisville Dockless Trips Dashboard (City of Louisville, KY n.d.-b).

- How Chicago Protects Privacy in TNP and Taxi Open Data (City of Chicago, IL 2019).

Resource: Managing Mobility Data

Author: National Association of City Transportation Officials (NACTO) and the International Municipal Lawyers Association (IMLA)

Date: 2019

URL: https://nacto.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/NACTO_IMLA_Managing-Mobility-Data.pdf

Description: Fourteen-page document that sets out “principles and best practices for city agencies and private-sector partners to share, protect, and manage data to meet transportation planning and regulatory goals in a secure and appropriate manner. While this document focuses mainly on the data generated by ride-hail and shared micromobility services, the data management principles can apply more broadly.”

Topic Area(s):

Data Sharing Policies and Practices

Operations

Planning

Enforcement

Resource Type:

Literature or Online Resource

Summary: The document discusses the challenges of balancing the need for information with providing adequate privacy protection. It has an excellent discussion on how geospecific trip data can become PII—the reason such data need to be treated as sensitive information.

The document defines and discusses four principles for managing mobility data: public good, protected, purposeful, and portable. Specific, actionable best practices for public agencies are provided to put each principle into practice. Additional, more detailed best practices for data governance and data management are also provided. The document concludes with examples of the types of questions that public agencies wish to address through the collection of mobility data, broken out into planning, oversight, analysis, and enforcement topics.

Additional Details: As an example, the “purposeful” principle is defined as the need for clear definition of the types of questions the organization is seeking to answer and to map data requests to those needs. Four high-level recommendations are discussed, including developing an internal capacity to audit the data to ensure their accuracy.

Specific, bulleted examples of best practices, such as “aggregate all geospatial data before committing it to permanent storage” are provided for seven areas: storage, sharing, access, oversight, expanding staff capacity, data aggregation, and common data queries.

Additional Resources: Guidelines for Regulating Shared Micromobility (NACTO 2019, Chapter 5, Mobility & User Privacy).

Resource: Shared Mobility Data: A Primer for Oregon Communities

Author: Trillium Solutions, Inc.

Date: 2020

URL: https://www.oregon.gov/odot/RPTD/RPTD%20Document%20Library/Shared-Use-Mobility-Data-Primer.pdf

Topic Area(s):

Data Sharing Policies and Practices

Resource Type:

Literature or Online Resource

Description: Thirty-seven-page primer on data policies and practices for shared mobility systems.

Summary: While written for Oregon communities, the content is applicable to any locality, the guide is easy to read and provides an excellent introduction to the topic while giving specific, actionable advice.

Additional Details: The guide consists of an executive summary, a glossary of terms, five chapters (“Understanding Shared Mobility Data,” “Policy Development,” “Collection of Recommended Mobility Data Practices,” “Summary of Third-Party Data Analysis Tools,” and “Information Resources”), and an appendix that provides sample licensing terms for various types of shared mobility services across the country. The first chapter provides an explanation of open data specifications and open data that is very easy to read and understand and then describes the roles and capabilities of the GBFS and MDS. The second chapter draws on the decision tree in Objective-Driven Data Sharing for Transit Agencies in Mobility Partnerships (Shared Use Mobility Center 2019a) to lay out and define a four-step process for developing data sharing policies: (1) lay the groundwork, (2) establish the purposes for shared mobility data, (3) clearly define the data scope and data protection policies, and (4) draft the data policies. Guidance is provided on each of these steps. The third chapter goes into some detail on seven recommended practices:

- Strategic requests for proposals,

- Pilot programs,

- Codified data requirements,

- Using open data specifications,

- User surveys,

- Privacy risk assessments, and

- Using shared mobility data to manage sidewalk space.

The fourth chapter contains a unique table of six shared mobility data management dashboard products. The table includes the distinguishing features of each product, the cost for some of the products, and examples of locations that are using each product. The final chapter briefly describes eight references to investigate for additional information, many of which are also described in this chapter.

Additional Resources: None.

Resource: Shared Mobility Data Sharing: Opportunities for Public–Private Partnerships

Author: Rainer Lempert

Date: 2019

Description: Twenty-nine-page report written for TransLink, the Vancouver, Canada, area’s transportation authority, to help the agency plan a path forward with respect to developing a data sharing policy and data sharing agreement.

Topic Area(s):

Data Sharing Policies and Practices

Use of Third Parties for Data Management.

Resource Type:

Literature or Online Resource

Summary: The report discusses issues associated with data sharing in some detail and includes good examples of each. It also presents overviews of the GBFS and MDS standards and the rationale and state of the practice at the time for third-party data management. The report concludes with a set of specific recommendations and options for TransLink to consider.

The shared mobility data sharing environment is evolving rapidly. Although this study is only a few years old, its somewhat negative view of the MDS reflects the then-new and not yet widely adopted status of the standard. This had changed over the 2 years between the publishing of Lempert’s report and the writing of this chapter; however, the concerns expressed on the viability of some of the third-party data providers remained accurate as of early 2021.

Additional Details: The report discusses two major sets of issues with data sharing: the private sector’s concerns with sharing its proprietary data and privacy concerns. The report includes several instructive real-world examples of how location data can be re-identified and why location data may reveal sensitive personal information. It describes how bike- and scooter-sharing services have generally been more willing to share data than TNCs.

The report then introduces the GBFS and MDS standards, their relationship to one another, and their uses as well as their benefits and challenges. The MDS has evolved somewhat since the summary provided in the report. The discussion and examples of the challenges with implementing MDS are good but also dated. For example, it cites Washington, DC’s, initial decision that MDS was too complex to implement; however, this decision was changed in 2020, with a new requirement that service providers implement an MDS API for obtaining data.

The report’s discussion of SharedStreets provides a good introduction to the SharedStreets Referencing System in addition to discussing SharedStreets’ roles as a data aggregator and analytics provider.

Additional Resources: None.

Resource: Protecting Rider Privacy in Micromobility Data

Author: Tarani Duncan

Date: 2019

URL: https://blog.mapbox.com/protecting-rider-privacy-in-micromobility-data-81f6c93c868e

Description: Brief article describing privacy concerns with detailed trip-level data and examples of how aggregated trip data can be used for operations, planning and analysis, and enforcement.

Topic Area(s):

Data Sharing Policies and Practices

Operations

Planning and Analysis

Enforcement

Resource Type:

Literature or Online Resource

Summary: After a brief description of the privacy concerns raised by location-specific trip data, the article talks about how aggregated data can be used to demonstrate the usage and value of bike lanes, identify popular areas for trip origins and destinations for planning micromobility parking and mobility hubs, and monitor compliance.

Additional Details: The compliance discussion is further broken out to discuss monitoring of out-of-service vehicles and inspection data, tracking fleet size, identifying vehicles in prohibited areas in real time, and ensuring equitable distribution across their jurisdiction.

Additional Resources: Dockless Open Data (City of Louisville, KY n.d.-a), Ride Report, April 8, 2020, is a very good introductory webinar to the value of data sharing between providers and public agencies as well as the need for security. It consists of approximately 30 minutes of presentation, including seven best practices, and 30 minutes of questions and answers.

Resource: Prioritizing Privacy When Using Location in Apps

Author: Tom Lee

Date: 2019

URL: https://blog.mapbox.com/prioritizing-privacy-when-using-location-in-apps-f31cdec85fc9

Description: Short article that provides five specific recommendations for preserving privacy when dealing with location data, such as that associated with shared mobility trips.

Topic Area(s):

Data Sharing Policies and Practices

Resource Type:

Literature or Online Resource

Summary: The article discusses five specific recommendations for any use of location data:

- De-identification and anonymization. Specific suggestions are to remove any obvious identifiers (vehicle ID may be a linkable identifier in the MDS), break trip data down into shorter segments (useful for traffic data but likely not a viable strategy for many applications of shared mobility data), and discard the origins and destination end points for trips (again, not a viable strategy for many of the use cases for shared mobility data).

- Fuzzing and aggregation. Aggregation groups individual trips with some similarity together into larger groups of trips. Fuzzing can shift trip origins or destinations (perhaps by simply truncating the latitude and longitude data) while still maintaining the level of fidelity needed for a specific use case. Both practices are relevant to shared mobility data and are being used today.

- Encryption of data, both at rest and in transit. Location data should be routinely encrypted, and the process should use widely adopted and vetted libraries. While not discussed in this article, New York taxi data that had been released under a Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) request were deanonymized because a poorly chosen hashing algorithm was used to encrypt the medallion IDs (Hern 2014).

- Access control. Data access should be limited to those who need it, and procedures should be put in place for onboarding and offboarding staff who require access.

- Providing user choice. This recommendation is partially relevant for shared mobility. It is likely that neither individual users nor service providers will be given a choice about providing data to the public agency; however, agencies should make clear and transparent what data will be collected and how the data will be used.

Additional Details: None.

Additional Resources: Dockless Open Data (City of Louisville, KY n.d.-a) goes into detail on how Louisville fuzzes and aggregates the shared mobility data it collects, down to the level of code examples. That document is summarized in this report.

Resource: Using Micro-Mobility Data to Drive Transportation Policy Investments in Greater Boston

Author: Stephen Goldsmith and Matthew Leger

Date: 2020

Topic Area(s):

Data Sharing Policies and Practices

Planning and Analysis

Resource Type:

Literature or Online Resource

Description: Short article describing the dockless bikeshare program run by the Boston area Metropolitan Area Planning Council (MAPC) as well as MAPC’s approach to data sharing with Lime, the bikeshare service provider.

Summary: The goal for data sharing was to better understand how dockless bikesharing was being used and then to use the results to inform policy and investment decisions. After 18 months, MAPC analyzed 300,000 trips covering 380,000 miles.

Additional Details: The analysis showed that about 20% of trips were on “very high stress roadways” with high traffic volumes, multiple lanes in each direction, and no protected bike lane infrastructure. In many cases, there were few or no alternate routes for these portions of a trip. These results are being used to prioritize infrastructure investments.

More than half of the riders were not primarily bike riders, that is, they either had not ridden their own bike in more than 30 days or did not own a bicycle. Fifteen percent of trips began or ended at a transit station, which indicates that while last mile trips were a significant minority, they were not the primary reason for choosing a bikeshare. One-third of trips began and ended in different localities, which shows the importance of coordination across jurisdictions. The full report on the analyses is listed under “Additional Resources.”

Additional Resources: First Miles: Examining 18 Months of Dockless Bikeshare in Metro Boston (MAPC 2019).

Resource: Effectively Managing Connected Mobility Marketplaces

Author: Stephen Goldsmith and Matthew Leger

Date: 2020

URL: https://dash.harvard.edu/handle/1/42556710

Description: Twenty-three-page white paper recommending the implementation of data-driven investment and regulatory policies for mobility.

Topic Area(s):

Operations

Planning and Analysis

Enforcement

Curb Management

Resource Type:

Literature or Online Resource

Summary: The paper addresses the policies and regulations that government agencies can put in place to ensure equity, enforce regulations, make investment decisions, plan zoning and land use, and protect sensitive data. The scope of the paper is broader than shared mobility, encompassing transit and freight movement as well.

Additional Details: The paper is written at a high level, with broad recommendations on the types of policies that should be put in place and on the role of data in informing and enforcing these policy decisions. The paper includes the following sections:

- Investments in Physical and Digital Infrastructure,

- Regulating and Licensing,

- Public Safety,

- Zoning and Land Use Planning,

- Regulating the Digital Realm (specifically, dealing with private apps routing vehicles onto low-volume residential streets),

- Advancing Equitable Access, and

- Public-Private Mobility Partnerships.

Additional Resources: “Moving Beyond Mobility as a Service: Interview with Seleta Reynolds” (Gardner 2019).

Resource: CDS-MUseCase:FromPolicyNeeds to Use Cases

Author: POLIS Network

Date Accessed: April 14, 2021

URL: https://www.polisnetwork.eu/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/Use-cases-G-52.pdf

Description: Fifteen-page paper that begins to describe the application data needs for the City Data Specification for Mobility (CDS-M) under development in the Netherlands.

Topic Area(s):

Operations

Planning and Analysis

Enforcement

Resource Type:

Literature or Online Resource

Summary: The CDS-M is a proposed alternative or modification to the MDS that is under development in the Netherlands. It is intended to address specific European needs, including use of standardized European vehicle classification systems and compliance with the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR).

The paper describes needs for quantitative data from each of five Dutch cities, so that these can be turned into requirements that the CDS-M standard must address. The use cases are divided into policy, planning, and enforcement. For each sufficiently defined policy question, the paper then provides the purpose of the need, the type of analysis (at an extremely high level), and the specific data that the standard would require to be provided. The paper dives deeper into a specific use case in Utrecht, which is interested in the extent to which shared electric carrier bikes will save on short car trips. The relevant need definitions are mapped to this use case.

Additional Details: The needs are formatted in the form of policy questions. Examples of the included use cases include the following:

- How are the existing parking areas being used, and which parking areas need to be enlarged/reduced/removed or made more visible?

- At what places is shared mobility creating nuisance/unsafe situations in the public space?

- Do the vehicles have the correct speed limits built in?

Additional Resources: Dutch Cities Develop New Mobility Data Standard (POLIS n.d.-b).

Resource: Charlotte Takes E-Scooter Data for a Test Ride

Author: Stephanie Kanowitz

Date: 2020

Description: Short article describing Charlotte, NC’s, e-scooter pilot program and how data are used to make decisions on how to move forward.

Summary: In 2018, the city of Charlotte, NC, began an e-scooter pilot program. The City used a private third party, Passport (https://www.passportinc.com/), to manage and analyze the data. In addition to investigating how much the system was used and how it was being used,

Topic Area(s):

Operations

Planning and Analysis

Use of Third Parties for Data Management

Resource Type:

Literature or Online Resource

Charlotte implemented a 6-month trial period of a dynamic pricing system for service providers rather than a flat per-vehicle charge.

Additional Details: For the dynamic pricing pilot, the city was divided into different zones with different prices to incentivize access to transit and discourage overconcentration in congested areas. In addition, the fee varied by how long each vehicle was parked. Hot spot visualizations of the data helped the city determine where scooter corrals should be located.

Additional Resources: None.

Sample Documents or Agreements

This section includes examples of permitting or license agreement terms that public agencies are using to regulate the exchange of information between shared mobility service providers and public agencies. Some localities include the terms within the general permit or license document, while others use separate agreements related specifically to data sharing that are incorporated by reference. The examples included in this section cover requirements for TNCs and taxi operators as well as micromobility service providers. In addition, this section also includes the LADOT Data Protection Principles, which are the principles that LADOT has placed upon itself to securely handle the data it collects.

The section contains the following resources:

- Transportation Network Companies: Data Reporting,

- Required Reports for Transportation Network Companies,

- LADOT Data Protection Principles,

- 2019 E-Scooter Pilot Program Permit Application and Administrative Rules for Shared Electric Scooters,

- Director Rules for Deployment and Operation of Shared Small Vehicle Mobility Systems,

- Shared Mobility Data Sharing Specifications Policy, and

- Data Sharing Section of Minneapolis, MN, Licensing Agreement.

Resource: Transportation Network Companies: Data Reporting

Author: City of Seattle, WA

Date Accessed: January 2021

Description: City regulations.

Topic Area(s):

Data Sharing Policies and Practices

Resource Type:

Sample Document or Agreement

Summary: City regulations specifying the data collection, maintenance, and reporting requirements for taxicab associations, for-hire vehicle companies, and TNCs.

Additional Details: The document lays out the following requirements:

Taxicab associations, for-hire vehicle companies and transportation network companies must compile accurate and complete operational records and keep these records for two years. The records must include:

- The total number of rides provided by each taxi, for-hire vehicle license holder or transportation network company.

- The type of dispatch for each ride (hail, phone, online app, etc.).

- The percentage or number of rides picked up in each ZIP code.

- The pickup and drop off ZIP codes of each ride.

- The percentage by ZIP code of rides that are requested by telephone or applications but do not happen.

- The number of collisions, including the name and number of the affiliated driver, collision fault, injuries, and estimated damage.

- The number of rides when an accessible vehicle was requested.

- Reports of crimes against drivers.

- Records of passenger complaints.

- Any other data identified by the director of the Department of Finance and Administrative Services to ensure compliance.

Records may be maintained electronically.

Data must be reported quarterly to the director of the Department of Finance and Administrative Services. Reports are to be made electronically on forms provided by the director.

Additional Resources: None.

Resource: Required Reports for Transportation Network Companies

Author: California Public Utilities Commission

Date Accessed: March 3, 2021

Description: State regulation.

Topic Area(s):

Data Sharing Policies and Practices

Resource Type:

Sample Document or Agreement

Summary: This regulation defines the annual data-reporting requirements for TNCs. It provides a data dictionary reference and Excel templates for reporting. Numerical reports must be filed in Excel or CSV format, while narrative reports must be provided in PDF format.

Additional Details: The reporting requirements are extensive, with the following 20 report types listed:

- Driver Names & IDs,

- Accessibility Report (Confidential),

- Accessibility Report (Public),

- Accessibility Complaints (Confidential),

- Accessibility Complaints (Public),

- Accident & Incidents,

- Assaults & Harassments,

- 50,000+ Miles,

- Number of Hours,

- Number of Miles,

- Driver Training,

- Law Enforcement Citations,

- Off-platform Solicitation,

- Aggregated Requests Accepted,

- Requests Accepted,

- Aggregated Requests Not Accepted,

- Requests Not Accepted,

- Suspended Drivers,

- Total Violations & Incidents, and

- Zero Tolerance.

Additional Resources: None.

Resource: LADOT Data Protection Principles

Author: City of Los Angeles, CA

Date: 2019

URL: https://ladot.lacity.gov/sites/default/files/documents/2019-04-12_data-protection-principles.pdf.pdf

Description: LADOT policies for protecting data collected from providers of dockless mobility services.

Topic Area(s):

Data Sharing Policies and Practices

Resource Type:

Sample Document or Agreement

Summary: Specifies that providers of dockless mobility service are required to use the MDS standard to provide data and lays out how LADOT will protect the data as well as user privacy.