Data Integration, Sharing, and Management for Transportation Planning and Traffic Operations (2025)

Chapter: 13 Managing Sensitive Shared Mobility Data

CHAPTER 13

Managing Sensitive Shared Mobility Data

Introduction

Shared mobility is “the shared use of a vehicle, motorcycle, scooter, bicycle, or other travel mode; it provides users with short-term access to a travel mode on an as-needed basis” (SAE J3163_201809). The scope of shared mobility includes micromobility services such as bikesharing and electric scooter services as well as car sharing, microtransit, paratransit, transportation network companies (TNCs), ridesharing (carpooling and vanpooling), and traditional ride-hailing (taxi) services. These services are typically provided by private-sector entities that this chapter refers to as “mobility service providers.”

Public agencies need data from mobility service providers to manage the public right-of-way and improve decision-making with regard to public policies and investments. The public-sector agency use cases for these data can be grouped into three categories—operations, planning and analysis, and enforcement:

- Operations use cases deal with subjects such as right-of-way management, vehicle utilization, fleet sizes, prohibited zones for operations or parking, and identifying areas that may be under-or overserved.

- Planning and analysis use cases examine how the service fits into the larger transportation ecosystem and include using data to understand demand patterns for shared mobility, what physical infrastructure is being used (e.g., for parking), what routes are being taken (and, hence, where and what kind of new infrastructure might be suitable), what the right price for curb space is, and the relationship with transit stations or other transportation options.

- Enforcement use cases involve monitoring and auditing provider operations to ensure that both mobility providers and their customers are complying with established regulations. Specific activities may include determining whether service providers are accurately reflecting the status of their fleets, how well providers are rebalancing and maintaining their fleets, and when and where people are riding or parking vehicles in prohibited areas.

The public sector needs data in sufficient detail and with sufficient timeliness to fulfill its operations, planning, and enforcement functions. At the same time, agencies want to protect proprietary data that mobility service providers want to ensure is protected from release, as well as other data that may have the potential to reveal private information regarding individual users. Hence, there is a need for public agencies to have policies, procedures, and mechanisms to adequately protect these data.

Purpose and Intended Audience

The purpose of this chapter is to inform public agency managers and staff about issues relating to protection of sensitive information that may be gathered as part of a locality’s shared mobility

programs. Specifically, sensitive data include data that may be able to be associated with specific individuals as well as data that mobility service providers consider proprietary.

The goal is not to turn readers into information privacy experts, but rather to provide sufficient depth so that they can become familiar with the issues and approaches for resolving them and to enable readers to have more productive discussions, both with interested parties (e.g., mobility service providers, academic researchers, and public advocacy groups) and with domain experts such as information technology (IT) staff, cybersecurity specialists, and lawyers.

This chapter is intended to be easily read in its entirety and to provide a comprehensive guide to recommended practices. It can also be used as a reference to find information on specific topics as they arise.

The references cited are listed at the end of the chapter.

Scope

This chapter provides recommendations and specific guidelines for protecting sensitive information related to shared mobility services, including both micromobility (e.g., shared scooter and bike services) and other shared services, such as free-floating carshare, ridesharing, and ride-hailing (taxi) services. It provides a step-by-step process, beginning with determining the use cases for which data are needed. It then addresses determining what types of data need to be collected, analyzed, or retained to meet these use cases. This involves identifying the subset of data likely to contain proprietary or sensitive personal information, developing guiding principles and policies for managing sensitive data, and describing specific protection mechanisms that should be considered to protect the data, both when they are used by the collecting agency and when they are shared with others.

Those responsible for shared mobility programs should work with their agency’s IT department and others responsible for agencywide security and privacy policies, both to ensure that the specific need for shared mobility programs is addressed and that the shared mobility programs comply with all relevant agency requirements.

Overview

This section provides background information on why certain data used to regulate and manage shared mobility services are sensitive, some of issues that arise, and the relationship between privacy protection and cybersecurity. These topics are then addressed in more detail in the later sections of the chapter.

Sensitive Information

In this chapter, sensitive information refers to information whose loss, misuse, unauthorized access, or modification, could adversely affect the private organizations that own the information or adversely affect the privacy rights of individuals. There are two primary types of sensitive information that a public agency may need from mobility service providers: personal information and proprietary information.

Personal Information

Personal information, is categorized as personally identifiable information (PII) and potentially identifiable personal information. The former is “any representation of information that permits the identity of an individual to whom the information applies to be reasonably inferred

by either direct or indirect means” (NIST n.d.-b). The latter, and the type of information that this chapter is mostly concerned with, is “information that has been de-identified but can be potentially re-identified” (NIST n.d.-c). To operate, mobility service providers must maintain PII, such as billing information for their customers. Customer PII is not needed by government agencies overseeing shared mobility operations. However, these agencies may often need detailed geolocation data, including information on the origin and destination of individual trips. When combined with other information, these data can potentially be re-identified and associated with an individual. Therefore, this information is potentially identifiable personal information and must be treated as sensitive data.

Data can be assigned to one of four categories regarding their personal nature, as shown in Table 13-1. The table provides examples of data that fit into each category, the relevance of the data category to shared mobility, and whether the data need to be treated as sensitive.

As discussed later in the section “Protection Controls and Methods,” care must be taken when de-identifying data, whether through aggregation, obfuscation, or other methods, to ensure there is little chance that, when combined with other available data, the data cannot be relinked to an individual.

De-Identification and Re-Identification

In the 1990s, the state of Massachusetts released summary records of every state employee’s hospital visits. The data were scrubbed of names, addresses, and Social Security numbers and were believed to be adequately de-identified so that the records could not be linked to any individual.

Each record, however, still included the patient’s zip code, date of birth, and gender. With the knowledge that the governor had recently been hospitalized, a graduate student combined these data with public voting records to identify the governor’s medical records, including his medical history, diagnosis, and prescriptions.

Source: Lubarsky (2017).

Proprietary Information

Proprietary information is “sensitive information that is owned by a company and which gives the company certain competitive advantages” (USLegal, n.d.). Proprietary information “can include secret formulas, processes, and methods used in production. It can also include a company’s business and marketing plans, salary structure, customer lists, contracts, and details of its computer

Table 13-1. Categories of personal information.

| Data Category | Common Examples | Relevance to Shared Mobility |

|---|---|---|

| Direct identifier |

|

|

| Indirect identifier |

|

|

| Data that cannot be linked to any individual |

|

|

| Data not related to individuals |

|

|

systems” (USLegal, n.d.). Some, but not all, of these data may fall into the category of trade secrets. In the case of shared mobility, proprietary data may include cost data, trip volumes, trip origins and destinations, equipment outage rates, and more. Publication of or access to this private information may give an advantage to the service provider’s competitors.

Interrelationship Between Privacy and Cybersecurity

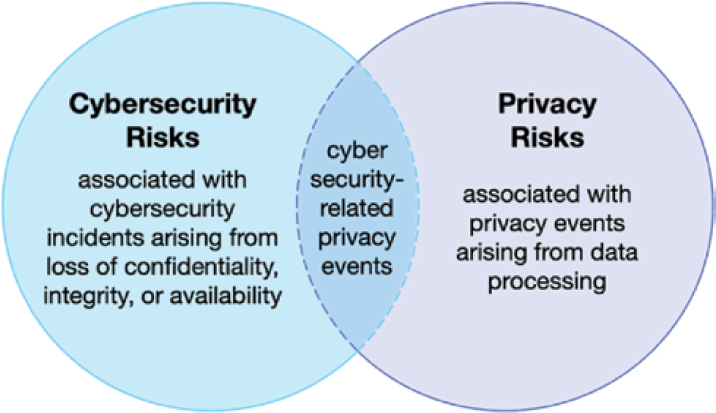

Cybersecurity and the protection of privacy are separate but overlapping domains, as shown in Figure 13-1. An organization’s risks from cyber incidents are broader than privacy incidents alone and include ransomware, denial-of-service attacks, and financial theft. Similarly, while it is critical to provide adequate cyberprotection for privacy-related data, there are other risks to privacy, including re-identification, as discussed in the previous section, and policies that allow data to be used by third parties for additional purposes beyond those for which the data were originally collected (NIST 2020a).

It is necessary, but not sufficient, to provide proper information security policies and methods. Therefore, shared mobility offices need to work closely with the IT and cybersecurity staff in their agencies, as well as with policy staff and agency lawyer(s) dealing with privacy issues.

The Context for Exchanging Mobility Data

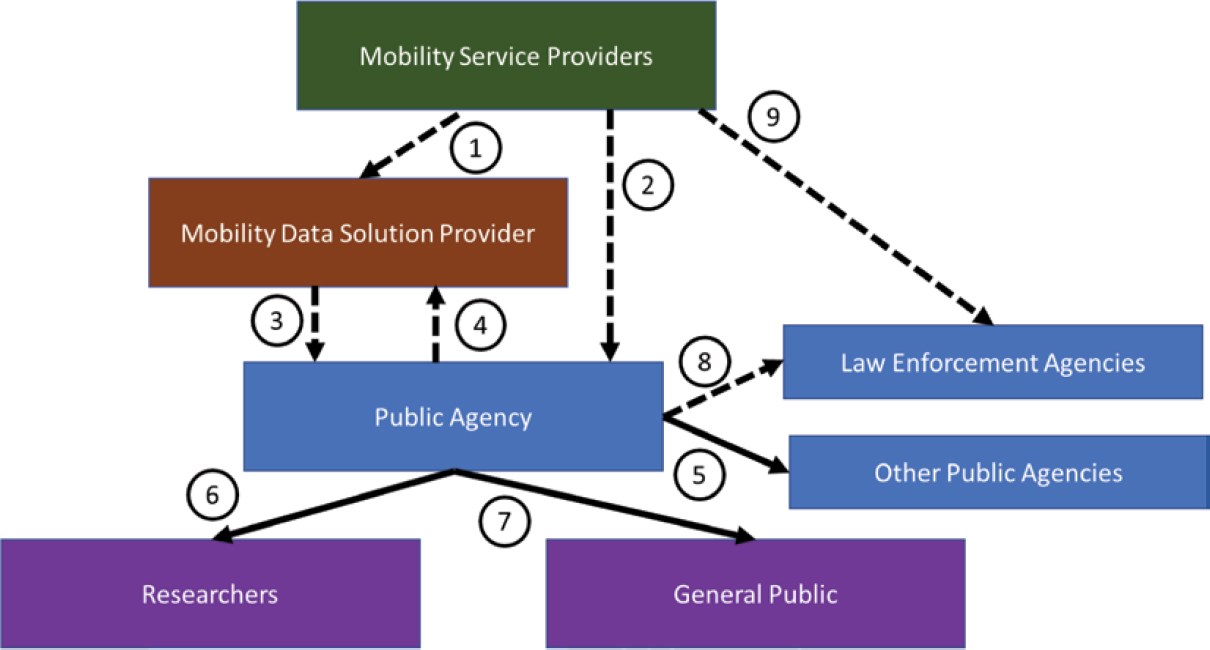

As shown in Figure 13-2, the original sources for shared mobility data are the mobility service providers. In the simplest case, they provide data directly to the responsible public agencies (Data Flow 2). The public agency stores, manages, and analyzes the data. It will likely share some processed subset of information with other public agencies, including transportation planning (Data Flow 5). The public agency may also provide processed subsets of data to researchers and publish other data for use by the public (Data Flows 6 and 7). Law enforcement agencies may also request data from a public agency (Data Flow 8). Often, what a law enforcement agency is seeking is PII data, which, in many cases, a public agency will not have but the mobility service provider might (Data Flow 9). As discussed later in this chapter, an agency should determine how it will respond to requests from law enforcement and what legal documents (e.g., warrants) it may require before turning over information.

For multiple reasons, an agency may choose to contract out data management and analysis as a service, which is provided by a mobility data solution provider (MDSP). MDSPs are organizations that an agency contracts with to provide some combination of data collection, management,

Source: NIST (2020a).

analysis, and reporting of shared mobility data on its behalf. There are for-profit, nonprofit, and university entities that have been established to fulfill this role. An MDSP may get the data either directly from service providers (Data Flow 1) or from the public agency (Data Flow 4), which received the data from the mobility service providers. In either case, a processed subset of data and analysis results is passed back from the MDSP to the public agency (Data Flow 3).

The rest of this chapter walks through the recommended steps for managing sensitive data and makes recommendations on approach and best practices for each step:

- Determining data needs:

- Determine the use cases,

- Determine the data needed for each use case, and

- Identify sensitive data.

- Develop principles and policies for managing sensitive data.

- Implement appropriate controls and mechanisms for protecting sensitive data.

One can make a case for reversing Steps 1 and 2; however, by first determining its needs, an agency will have defined the scope of topics that need to be addressed by its principles and policies.

Determining Data Needs

A good rule of thumb is to collect only data that the agency and other internal partner agencies (e.g., transportation planning offices) need and to collect these data in the least sensitive manner. There are no privacy or proprietary data risks relating to data that the agency never collected: “Adhering to appropriate anonymization practices and ensuring a local government does not collect more information than is needed is the best way to safeguard against potential legal challenges” (NACTO and IMLA 2019). An agency should resist the urge to collect all available data with the intent of later figuring out whether it is needed. If the agency wishes to conduct exploratory analyses to determine whether more granular or other data might add value, then collection of the more detailed data for a limited period, with policies for data destruction or anonymization upon completion of the experiment, should suffice.

The initial steps are to determine what questions, analyses, and actions the agency needs data for—that is, to define the specific use cases—and then identify the data needed to support each use case. Use cases can be defined broadly, providing flexibility, or narrowly, providing more specific guidance on what information is needed. It is not necessary to define every use case to the same level of detail (OMF 2020b, n.d.-c).

Determine the Use Cases

Data from mobility service providers may be needed to oversee and regulate operations, for transportation planning and analysis, and to enforce related laws and regulations. When identifying the use cases, an agency should consider internal use cases and uses other agencies may have for the data as well as use cases for publication of data to provide information both to the public and to researchers (e.g., public reporting of geographic equity of service).

Operations

Operations use cases are associated with day-to-day operations, including monitoring and managing the total number of vehicles in operation, right-of-way management, vehicle utilization rates, vehicle parking, and identification of under- or overserved areas. Following are operational questions an agency might seek to answer:

- Where and when are there clusters of vehicles, and how did they get there?

- Where and when are there not enough, or too many, vehicles in an area and why (e.g., lack of infrastructure or vehicle availability)?

- How many vehicles are on the street but unavailable due to a maintenance issue or low battery?

- Which parts of the city are ride-hail services and micromobility serving and not serving?

- Were dockless micromobility or ride-hail vehicles involved in crashes?

Along with other data sources, the specific types of data from mobility providers that might be needed include time-dependent origin–destination data, routes taken, trip duration, number of vehicles by service type and status within specified geographic and time boundaries, the number of trips taken per vehicle per day, and parking area usage.

Planning and Analysis

Planning and analysis use cases deal with issues that are more long term than daily operations as well as with broader topics, such as transportation planning, overall impact on the streets or city, or the impact of micromobility on street design and infrastructure investments. Following are some questions that public agencies may seek to answer:

- What are the impacts on street, curb, and sidewalk safety?

- What is the impact on economic development?

- How do ride-hail services and micromobility trips connect with or substitute for existing transit services?

- Which routes and streets are most used by people on shared micromobility vehicles?

- How efficiently are ride-hail services using the streets?

- What share of total transportation emissions and local air pollution is coming from ride-hail services?

- How do vehicle utilization and pooling relate to congestion by geography?

- How many nonrevenue vehicle miles traveled occur on the street (e.g., TNC vehicles deadheading or distribution of dockless micromobility vehicles being rebalanced)?

- What is the right price for curb space?

Usage, demand, and trip-level data can be used to determine the location of new bike/scooter lanes and vehicle parking areas and to allocate curb usage, all of which offer value to the service

providers as well as the general community. Another area of interest for most localities is the interrelationships and interactions between various shared mobility modes and public transit operations, such as the use of shared mobility to address last mile issues or the extent to which shared mobility services compete with transit for usage and ridership. These types of analyses can help service providers demonstrate the value that they are providing to the community.

Enforcement

Enforcement use cases include enforcing both service provider and user compliance with regulations. The two are interrelated, as enforcement policies may hold the service provider responsible for the actions of its users. Enforcement may include

- Regulations related to operations in restricted areas, speed violations, parking or riding on restricted sidewalks, and restricted hours of operation;

- Calculation of any fees due from operators, which may be based on the number of vehicles deployed, the number in use per day, or other criteria; and

- Verifying the accuracy of data from providers with independently measured ground truth data to identify and resolve discrepancies. This can include using check rides, independent observations, and data auditing tools.

Use Case Resources

There are several sources that can be used to help determine the use cases that your agency may be interested in. The Open Mobility Foundation provides a database of use cases that various agencies have for using micromobility data (OMF 2020b) provided through the Mobility Data Specification (MDS) (OMF n.d.-d). The New Urban Mobility alliance (NUMO) provides an interactive web-based tool for use cases related to policy goals, including those associated with safety, environmental, and usage outcomes (NUMO n.d.).

Comprehensive examples for use cases related to free-floating carshare, TNCs, and ride-hailing services are not available, but ideas can be reverse engineered from examining a combination of the regulatory reporting requirements that some states and cities have put in place along with the publicly released analysis and datasets. Links to examples of reporting requirements are provided in Appendix 13-A, “Examples of Taxi and TNC Data-Reporting Requirements and Publicly Released Data.”

Determine the Data Needed for Each Use Case

Once the use cases have been enumerated and defined, the next step is to determine the data needed for each one. This involves identifying the data elements needed and the fields within each element. For micromobility, an agency should work from the standardized data elements found in the MDS and the General Bike Feed Specification (GBFS), two complementary standards, one focused primarily on providing data from mobility service providers to public agencies (MDS) and the other focused primarily on providing data from mobility service providers to the public (GBFS). For example, an agency that has a use case to track the volume of vehicles traveling on each street might determine that it should be collecting /trips data via the MDS standard. The /trips element has 13 required fields, including vehicle_id, start_time, end_time, and route, along with five optional elements, including standard_cost and actual_cost. If trip data are only needed for this single use case, the agency would likely determine that there was no need for the optional cost elements; however the agency might have other use cases that require those elements.

For other types of shared mobility, the data structures specified for micromobility services in the MDS and GBFS are still a useful guide to what is needed for the same types of use cases.

For example, Populus and Lime teamed up to use the MDS as the format for collecting data on Lime’s free-floating carshare service for the city of Seattle (Populus 2018). The current version of MDS (Version 2.0) now supports passenger services (e.g., taxis, ride hailing), car sharing, and delivery robots in addition to shared e-scooters and bikes (OMF 2023, n.d.-i).

In addition to leveraging existing standards, an agency can examine what other agencies have required for reporting other types of shared mobility service data (see Appendix 13-A “Examples of Taxi and TNC Data-Reporting Requirements and Publicly Released Data”). Another question for an agency to consider is whether it needs raw, detailed data in every case or if some of its use cases could be met by having the mobility service providers send only preaggregated or preobfuscated data. If the data an agency receives cannot be linked to individuals, the requirements for safeguarding the data are greatly reduced. One issue to consider when choosing to receive only aggregated data from a provider is that this makes it more difficult to audit the data being reported. Raw, granular data can be more easily spot-checked by using field observations.

While an agency should use established standards for data sharing where possible, the MDS was originally created to provide raw, detailed data to public agencies rather than for sharing less-detailed or aggregated data. However, the MDS is evolving to help support these needs in a standardized manner. Additional details on how the MDS is being revised can be found in Appendix 13-B, “The Mobility Data Specification and Improved Privacy by Design.”

Another option, which is discussed later under “Policies Regarding Sensitive Data” is to use an MDSP. The MDSP gets the raw, detailed data from the mobility service provider and is responsible for safe storage, management, and analysis of the data. Only the results of the analyses, along with aggregated or obfuscated data, are forwarded on to the public agency.

Identify Sensitive Data

Proprietary Data

After an agency has determined its data needs, it should next assess the integrated and consolidated set of data requirements to determine which elements may be proprietary to a provider or contain identifiable or potentially identifiable personal information. Mobility service providers will identify which data they consider to be proprietary and to require protection from sharing or public release, including via public records requests. The laws protecting proprietary data are not absolute. For example, in the state of Washington, the state supreme court has ruled that, to be redacted from a public records request, data must meet two conditions: they must be proprietary, and the disclosure must not be in the public interest and pose substantial and irreparable harm (Supreme Court of the State of Washington 2018). State and local public records and freedom-of-information laws vary across the country, and an agency should work with its legal counsel to determine whether it agrees with the scope of the proprietary data claims of its mobility service providers and on the protections that it can commit to.

PII Containing Direct Identifiers

Micromobility services need to maintain PII on their customers, but there is no need for public agencies or their MDSPs to collect these data. The best practice is to clearly state in any agreements or permitting requirements that no such information is to be provided by service providers.

In the case of taxis and TNCs, again, no PII on passengers is needed; however, many agencies collect—and some both collect and publish—lists of taxi or TNC drivers by name. While these agencies collect sensitive information that associates each driver with specific companies

and trips, these data are not released to the public, and data fields that could be used to relink these data (e.g., medallion number) are either redacted or replaced with a pseudo-ID. Specific policies on what is collected and what is publicly released vary by locality. Each public agency needs to review state and local laws and its broader organization’s policies and then determine its own policies concerning these data. For example, Chicago, IL, collects driver information for both taxis and TNCs but only publishes the names of licensed taxi drivers; New York City, in contrast, publishes the names of both.

Proprietary Ridesharing Data

Uber and Lyft claim that the identity of their drivers is proprietary information, and the city of Chicago, IL, agreed, denying a Freedom of Information Act request for the data.

Isaac Reichman, a spokesman for Chicago’s Business Affairs and Consumer Protection department, stated that the information was provided to the city “under the claim that the data is proprietary and confidential in nature and that its disclosure would cause significant harm to the businesses that submitted it.”

Source: Eidelson and Bloomberg (2019).

Potentially Identifiable Personal Information with Indirect Identifiers and Anonymized Data

The final category of sensitive information is information that does not directly identify an individual but could be combined with other data to identify individuals, including data that have been anonymized in some fashion to prevent this from happening. As discussed previously, for shared mobility, potentially identifiable personal information refers primarily, but not exclusively, to geolocation data. The guide Managing Mobility Data guide states,

Geospatial mobility data can be combined with other data points to become PII (sometimes referred to as indirect or linked PII). For example, taken by itself, a single geospatial data point like a ride-hail drop-off location is not PII. But, when combined with a phonebook or reverse address look-up service, that data becomes easily linkable to an individual person. (NACTO and IMLA 2019).

Agencies should look at the data elements and the data fields they contain to identify data that could, when combined with other information, reveal an individual’s identity and, potentially, other sensitive information about the individual, such as the person’s travel destination. To do this, one needs to think creatively, looking not just at the intended purpose for collecting the data but at what unintended purposes the data could be put to. For example, it was determined that, for dockless bikeshare services, the bike_id element in the GBFS could be used to recreate trip origins and destinations and possibly identify trips taken by specific individuals. Therefore, the specification for the bike_id element in GBFS was changed from a static value to one that randomly changes after each trip.

Like security, privacy is never absolute, and there are trade-offs that need to be made between the value of the data collected and the potential privacy risks that the data represent (Ohm 2010). Agencies should examine the risks; their likelihood of occurrence; and the potential impact of improper use, unauthorized disclosure, and re-identification. There are several approaches and tools that an agency can use to conduct this analysis. A privacy impact assessment (PIA) is one of those tools. A PIA is

an analysis of how information is handled to ensure handling conforms to applicable legal, regulatory, and policy requirements regarding privacy; to determine the risks and effects of creating, collecting, using, processing, storing, maintaining, disseminating, disclosing, and disposing of information in identifiable form in an electronic information system; and to examine and evaluate protections and alternate processes for handling information to mitigate potential privacy concerns. A privacy impact assessment is both an analysis and a formal document detailing the process and the outcome of the analysis (NIST n.d.-d).

PIAs go beyond identifying and estimating risks to also ensure that legal requirements are met and to identify mitigation measures that will be or have been put in place to reduce the identified risks. Multiple federal agencies have standard templates for PIAs that can be borrowed from and used as a model. The U.S. Department of Homeland Security (n.d.) provides a model template, and

the U.S. General Services Administration (n.d.) a completed template. In addition, there are other examples that are more directly related to shared mobility that can be used as models, including the following:

- Oakland, CA’s, Draft Anticipated Impact Report: Data Sharing Agreement with Dockless Mobility Service Providers for Program Management and Enforcement (Oakland Department of Transportation 2019);

- The San Diego Association of Governments’ Privacy Impact Assessment for Micromobility Data (Kutak Rock 2020);

- City of Seattle Open Data Risk Assessment, especially Appendices C and D (Future of Privacy Forum 2018), which specifically focuses on publicly released data; and

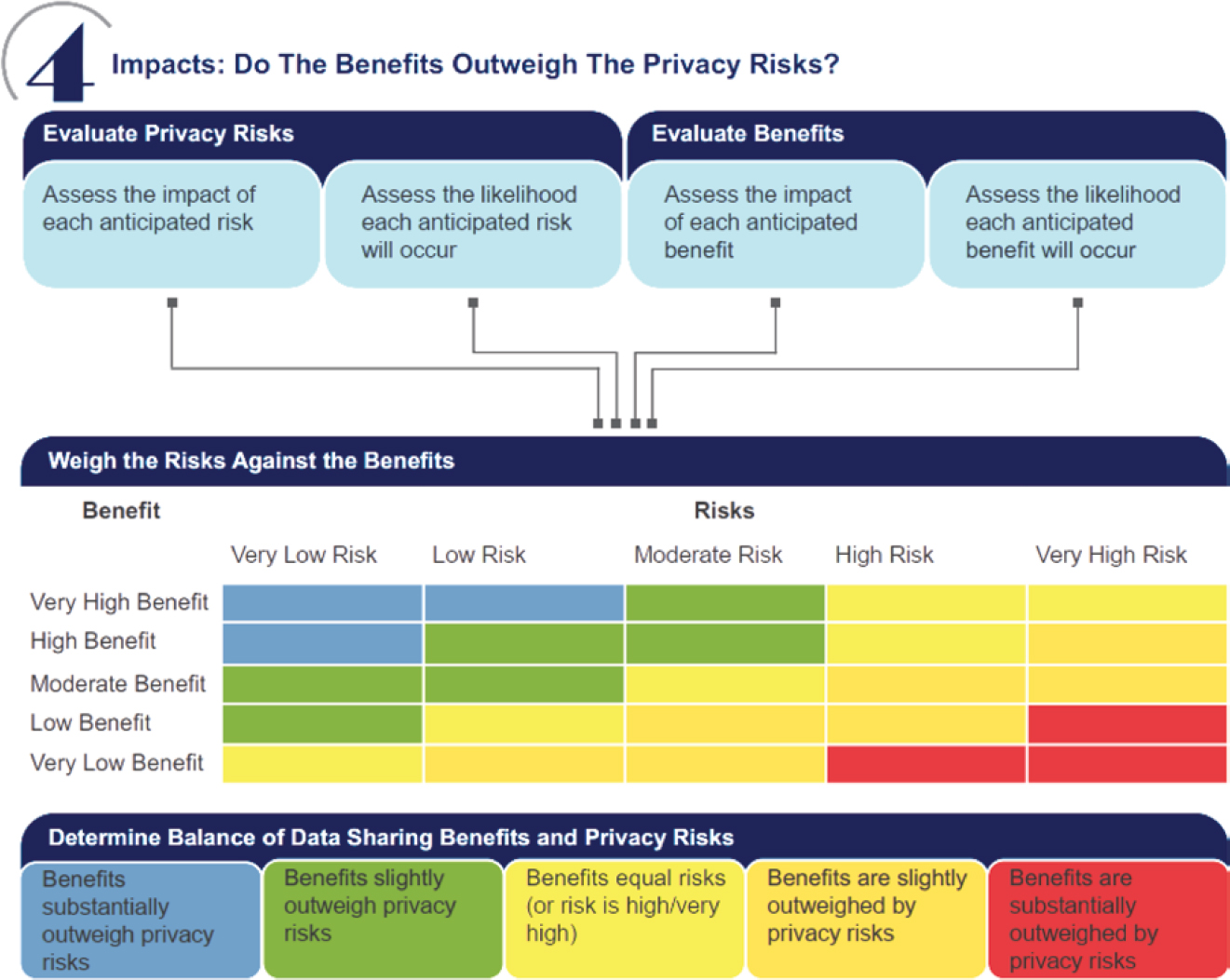

- The SAE ITC Mobility Data Collaborative’s Mobility Data Sharing Assessment tool, guide, and infographic (Mobility Data Collaborative 2022; Mobility Data Collaborative and Future of Privacy Forum 2021a, 2021b). The Collaborative is looking for agencies to try out the tool and provide feedback. An excerpt from the infographic explaining the methodology is shown in Figure 13-3.

In addition, the Open Mobility Foundation has written “Understanding the Data in MDS,” which discusses privacy and the MDS and lists the specific data elements and data fields in the MDS that contain sensitive information (OMF 2021).

Source: Mobility Data Collaborative and Future of Privacy Forum 2021a. © SAE ITC. All rights reserved.

Anonymized data are also a potential concern because of multiple examples in which improper anonymization has enabled the identification of individuals and the association of private information with them. In one case, the medical records of the governor of Massachusetts were identified. In another well-known instance, the New York City Taxi and Limousine Commission (TLC) responded to a Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) request to provide historical information on more than 173 million individual taxi trips. As a result of improper anonymization, the records were quickly de-anonymized and sensitive personal information on multiple individuals was derived. For this reason, aggregated, obfuscated, redacted, or otherwise anonymized data should be identified at this stage, so that it can be later be analyzed to ensure that it has indeed been adequately anonymized.

Improperly Anonymized Data Can Yield Private Information

In response to a Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) request, the New York City Taxi and Limousine Commission (TLC) released detailed trip records on more than 173 million taxi trips. Prior to releasing the information, the TLC attempted to anonymize the driver’s medallion number and taxi number. Unfortunately, it used an algorithm that fails if one has information about what the original information looks like (it is known that taxi licenses in New York City are all either 6-digit numbers or 7-digit numbers staring with a 5). A researcher de-anonymized the complete, 20 GB dataset in one hour (Pandurangan, 2014).

Another researcher then combined these data with other publicly available information to reveal, by name, where celebrities stayed in New York and how large a tip they left via their credit cards. He also analyzed trips departing an adult entertainment facility and from the drop-off locations was able, in several cases, to identify with high probability the individual traveler by name. In one case, he was able to identify the name and address, other destinations visited by the same person, the property value of his residence, his ethnicity, relationship status, and court records and to obtain a picture.

Source: Tockar (2014).

Policies Regarding Sensitive Data

Guiding Principles

An agency or city is likely to have privacy principles in place already as well as policies on handling proprietary data. Working with the appropriate agency staff, clerk’s office, open records office, and legal counsel is recommended to determine how applicable laws, regulations, and policies relate to the data that the agency will be collecting and whether additional policies are needed (OMF 2020a).

A good starting point for developing an agency’s principles and policies is “Privacy Principles for Mobility Data” (NUMO, NABSA, and OMF 2021), which provides a set of values and priorities for managing data while protecting individual privacy:

- We will uphold the rights of individuals to privacy in their movements.

- We will ensure community engagement and input, especially from those that have been historically marginalized, as we define our purposes, practices and policies related to mobility data.

- We will clearly and specifically define our purposes for working with mobility data.

- We will communicate our purposes, practices, and policies around mobility data to the people and communities we serve.

- We will collect and retain the minimum amount of mobility data that is necessary to fulfill our purposes.

- We will establish policies and practices that protect mobility data privacy.

- We will protect privacy when sharing mobility data.

The document provides recommendations for how to put each principle into practice.

Learning from the Past

In the early days of traveler information systems, many public agencies entered into data licensing agreements with private-sector information providers who utilized their own systems for collecting data. Several years later, some of the public agencies discovered that when they wished to provide data to the public via 511 websites and telephone systems, the licensing agreements prohibited such uses. The data could only be used for their own internal purposes; it could not be shared with the public, even in combination with other, public-sector data.

If an agency’s agreements do not transfer ownership of the data to the agency, the agreements should ensure that the agency has all the usage and sharing rights that it needs, both now and in the future.

A second useful reference that presents a set of principles, discusses issues that arise, and then offers specific recommendations is the NACTO policy document Managing Mobility Data (NACTO and IMLA 2019), which identifies four high-level principles that cover somewhat different aspects of privacy:

- Public good: Cities require data from private vendors operating on city streets to ensure positive safety and mobility outcomes, among others, on streets and places in the public right-of-way.

- Protected: Cities should treat geospatial mobility data as they treat personally identifiable information (PII). It should be gathered, held, stored, and released in accordance with existing policies and practices for PII.

- Purposeful: Cities should be clear about what they are aiming to evaluate when requiring data from private companies. This may include, but is not limited to, questions related to planning, analysis, oversight, and enforcement.

- Portable: Cities should prioritize open data standards and open formats in procurement and development decisions. Data sharing agreements should allow cities to own, transform, and share data without restriction (so long as standards for data protection are met).

While some agencies believe it is important for the agency to own the data, including full rights to sell and share it as they see fit, others take issue with the ownership portion of the fourth principle, arguing that mobility service providers may retain ownership of some or all the data, provided the public agency obtains a sufficiently broad and standardized license for use, including the sharing of appropriate data with other agencies and with the public (Franklin-Hodge 2019). Sharing and reuse provisions, especially the sharing of nonproprietary and appropriately anonymized data with the public, are especially important. Specific recommendations regarding the scope of use that should be included in licenses for shared mobility data can be found in “An Updated Practical City Guide to Mobility Data Licensing” (Zack 2019).

Selected Aspects

The scope of policies should include all types of sensitive data as well as each entity and interface in the shared mobility data context, as shown in Figure 13-2. This section discusses a subset of the elements that need to be considered when data management policies are being implemented. It is not a comprehensive discussion of all elements.

Transparency

As stated in Principle 4 of the “Privacy Principles for Mobility Data,” transparency with the public regarding privacy principles and practices is very important (NUMO, NABSA, and OMF 2021). Section 5.3 of the Mobility Data Sharing Assessment: Operator’s Manual introduces the

concept of a social license (Mobility Data Collaborative and Future of Privacy Forum 2021b). Since individual consent is not always feasible for data collection, meaningful and comprehensive public engagements that allow stakeholder input to decision-making can secure general community support. A social license is not a formal agreement; rather, a social license exists when a project has ongoing approval or broad social acceptance within the local community and other stakeholders.

Data Collection by Mobility Service Providers

State and federal privacy laws are a patchwork and tend to focus on specific areas, such as health records or financial data, with few general restrictions. An agency may want to serve the public by regulating what data mobility service providers can collect from their customers, what consent is required, and how it must be safeguarded. This can be done through the permit or license process for the providers. This may include what data are collected, how long they are retained, who can share the data, and why they can be shared and may also address requirements for fully informing customers of the providers’ data practices and requirements for disclosing security breaches (OMF 2020a). For example, for Minneapolis, MN’s, pilot scooter projects, the city required that providers offer transparency regarding their terms of use, privacy, and data sharing policies. They also required that users had to opt in to permit third-party data sharing or third-party access to location-based data and that the providers adequately protect any PII that was collected (City of Minneapolis, MN n.d.-a). Other localities, such as Austin, TX, and San Francisco, CA, have similar requirements that users must affirmatively opt in to agree to provide any data beyond those needed to operate the service or for their data to be shared with third parties (City of Austin, TX, Transportation Department n.d., City of San Francisco, CA 2019).

Use of Data by MDSPs

Rather than collect, manage, and analyze shared mobility data in-house, many transportation agencies outsource these functions to third parties, which are sometimes referred to as MDSPs. MDSPs typically obtain data directly from the mobility service providers (Data Flow 1 in Figure 13-2), although, in some cases, the agency may get the data from the mobility service providers and send them on to the MDSPs (Data Flows 2 and 4). Agency license or permit agreements with mobility service providers should call out the requirement for those providers to share data with the designated MDSPs.

These third parties receive raw data from mobility providers but do not provide the raw data to government agencies or to any other organizations. They securely store whatever data need to be kept and conduct the analyses that public agencies need to manage mobility providers. The public agencies receive the results of the analyses along with anonymized and aggregated data.

MDSPs typically work with multiple public agencies and multiple service providers, enabling them to often have a better understanding of the issues relating to data than a public agency. Some agencies, especially smaller ones, may simply lack the specific skills and resources needed to effectively manage and analyze the large volumes of data. In addition, some existing state laws do not adequately protect potential PII from FOIA requests or other types of disclosure, and similar concerns exist for proprietary data. Use of a third-party MDSP may reduce disclosure risks—for example, from FOIA requests—since the public agency never possesses such data (however, checking with the agency’s legal counsel as to whether disclosure requirements would pass through to the hired MDSP is recommended).

An agency should include contract terms in its agreement with any MDSP to limit use of the data to those specifically authorized by the agency and to mandate specific data security and handling controls. The Privacy Guide for Cities (OMF 2020a) recommends that the contract should:

- Mandate the right for the city to compel deletion of all stored data and access credentials upon request or when the agreement ends,

- Establish privacy and security provisions that limit how data is used and require it to be adequately protected, and

- Prohibit the reselling or monetization of the data.

The agreement should also identify who owns the data.

The data security and handling controls recommended for discussion with an MDSP and considered for incorporation into the agency’s formal agreement are described in more detail under “Protection Controls and Methods” later in this chapter.

See Data Flows 1 and 2 in Figure 13-2.

Data Sent from Mobility Service Providers to Public Agencies or Their MDSPs

On the basis of the use cases and data needs it has previously determined, an agency should specify what data should be provided by mobility service providers, the (preferably standardized) formats for those data, and how the exchange should be protected [e.g., limited access to application programming interfaces (APIs), encryption of the data in transit]. As discussed earlier, the goal is for the agency or its MDSP to be able to obtain all the data necessary to carry out the use cases and only the data needed for that purpose. If a subset of the agency’s needs can be met by aggregated data, then those data should be aggregated.

The sharing agreement, which may be incorporated into the licensing or permit agreements or be a stand-alone document incorporated by reference, should specify that directly personally identifiable customer information will never be provided by the service provider to either the public agency or its MDSP. Depending upon the type of shared mobility and the use cases, PII concerning drivers or vehicle operators may be needed.

Regardless of whether an agency currently uses an MDSP, its agreements with service providers should allow for it to use one and require that, if directed by the agency, the service provider send the specified data to the MDSP.

In most localities that use an MDSP, arrangements are made for the data to be sent directly between the service provider and the MDSP (Data Flow 1). This is generally the preferred approach, as it maximizes the advantages of using an MDSP. However, some agencies may choose to get the data and relay it to the MDSP (Data Flow 4).

See Data Flow 3 in Figure 13-2.

Data Sent from the MDSP to the Agency

One of the benefits of using an MDSP is that it has the expertise and systems in place to safely manage sensitive data. A second benefit is that service providers often already have existing relationships with MDSPs in other markets and trust them to handle proprietary data more than they trust a public agency. This can help resolve the tension between providing information adequate for public agencies to perform their functions while ensuring adequate protection of private and proprietary information. In some localities, this may also help avoid a requirement to disclose sensitive information as part of open records requests. For these reasons, if an agency uses an MDSP, the agency should have the MDSP keep any raw data that cannot be disposed of, especially sensitive data, and provide only anonymized or aggregated data to the agency, along with the analysis results needed.

Agency’s Internal Data Management

The extent to which an agency handles sensitive information will depend upon whether it uses an MDSP. However, even if an agency uses an MDSP, the agency is still likely to need and hold more information than would be appropriate for public release. For example,

city staff responsible for street operations need to know about the volume of pick-up/drop-off activity at specific locations to adjust curbside regulations accordingly. However, in public release of pick-up/drop-off data, that information should be aggregated, based on population density and land use characteristics, to create a general picture without identifying a specific building or residence. (NACTO and IMLA 2019)

Therefore, it is important to have the appropriate data management systems and policies in place to protect the data. The Privacy Guide for Cities recommends that an agency work with its IT department, legal counsel, and open records office before beginning implementation and, especially if the agency lacks experience managing sensitive information, that it talk to other agencies that may have more expertise, “such as health, law enforcement, or human resources” (OMF 2020a). Specific techniques for protecting sensitive data are provided later under”Protection Controls and Methods.”

One subject that agencies will certainly have to deal with is responding to public records requests. Depending on state and local government, laws allowing for requests and mandating release of certain data may be called public records laws, sunshine laws, freedom-of-information acts, or freedom-of-information laws. There are typically personal privacy and public interest exceptions to the data that must be released. An agency should work with its clerk’s office or legal counsel to determine the appropriate response to these requests and identify what data should not be released, what should be released, and what should be released only in anonymized and/or aggregated form. In general, agencies should avoid releasing data that could be linked to an individual or easily re-identified and linked. As discussed earlier, incorrectly “anonymized” taxi data released in response to a New York State FOIA request were easily re-identified and revealed private information (Tockar 2014).

Similar principles apply to proprietary data; however, some proprietary data may not be protected, and this will depend upon state and local laws. For example, in Lyft, Inc. and Rasier, LLC v. City of Seattle and Jeff Kirk, the Washington State Supreme Court ruled that while the data in question constituted trade secrets, they should only be withheld from a public records response if their release is “clearly not in the public interest and would result in substantial and irreparable harm to any person or vital government interest” (Supreme Court of the State of Washington 2018).

Agencies should consider, in their permitting or licensing rules for operators, a provision that the agency will inform mobility service providers of any open records requests for its data, so that it can review the request and file a legal objection should it choose.

See Data Flow 5 in Figure 13-2.

Data Sharing with Other Public Agencies

Most agencies likely collaborate with other departments and agencies as a routine part of their work. For example, the data the agency has collected or the results of analysis of the data likely need to be shared with transportation planners and with emergency and special events managers. These uses should be included in the use cases that the agency identifies, and only shared for approved uses. The use case analysis should also have determined whether the other agency needs detailed, granular data or if the need can be met by sharing desensitized aggregated data. If the datasets do include sensitive information, it is appropriate for the agency to identify the sensitive information, to require a documented understanding of what protections the receiving agency will provide for the data, and to require that the receiving agency seek permission prior to any further sharing or publication of the data (OMF 2020a).

See Data Flows 8 and 9 in Figure 13-2.

Data Sharing with Law Enforcement Agencies

Law enforcement agencies are a special type of public agency. There are different rules and regulations for requests for data from law enforcement, which may be specifically seeking sensitive information. Historically, the third-party doctrine has held that warrants are not required for private information that is voluntarily shared with third parties, such as mobility service providers. However, this is an evolving area of the law. In Carpenter v. United States, the U.S. Supreme Court held that government acquisition of historical cellphone locational records is entitled to Fourth Amendment protection; thus, collection of such information requires a warrant (Supreme Court of the United States 2018). Agencies should consider whether it is appropriate, or legal, to respond to informal requests for sensitive data or whether a court order or warrant should be required as a matter of agency policy, even if the agency could legally share the data without such an order. This is an area where transparency with the community is important, and an agency may want to socialize its proposed policy as part of achieving the social license discussed earlier under “Transparency.”

Often, law enforcement is seeking PII that the agency does not have. The law enforcement agency can be referred to the mobility service provider, who may have such data and can, given the appropriate court order or warrant, provide the data.

See Data Flow 6 in Figure 13-2.

Data Sharing with Researchers

The data that an agency collects has value for many researchers, whose research can be of benefit both to the agency and to the broader community. At the same time, whenever sensitive data are shared, the risk of their inappropriate use or disclosure increases. The preferred approach, if it can meet the needs of the researchers, is to direct them to data that are shared with the public, as these data will already have been appropriately anonymized and aggregated. However, there are sometimes legitimate research needs for more granular data. To handle such cases, an agency may want to draft standard data sharing agreements, such as those used when sharing with other agencies, that specify the limited uses that are being permitted and the protective controls and mechanisms that must be implemented and that prohibit any attempt to re-identify the data. The data sharing agreement that the District of Columbia used with university researchers wanting access to data from its 2020 dockless shared mobility program is available online as one model (District Department of Transportation n.d.).

See Data Flow 7 in Figure 13-2.

Data Sharing with the General Public

There are multiple benefits from sharing appropriate data with the public, especially in the form of human and machine-readable datasets on open data portals. Sharing data helps provide transparency, reduces the need for individually handling what would otherwise be open records requests or requests from researchers, and may be required by state or local open records rules. As with other topics discussed in this section, agencies are advised to review local regulations, discuss plans for public data with legal counsel, and learn from other agencies that routinely publish data for the community.

As the Privacy Guide for Cities states, “MDS data should not be shared publicly in its original form because it contains individual trip records that could potentially be combined with other datasets to identify a person” (OMF 2020a). Instead, the data need to be aggregated, obfuscated, or otherwise modified to significantly reduce the possibility of re-identification. Specific techniques are discussed later under “Protection Controls and Methods.”

Many localities have set up open data portals for various types of shared mobility. In some cases, the data are provided as part of larger city-wide open data portals. In other cases, the MDSPs have standardized approaches for providing these portals as part of their set of services. Examples include the following:

- Chicago Taxi Trips (City of Chicago, IL n.d.-b). The city’s data portal also includes information on TNC and scooter use.

- New York City Trip Record Data (New York City TLC n.d.-b). These extensive datasets cover taxis as well as for-hire vehicles, which include TNCs.

- Minneapolis Scooter Availability 2021 (City of Minneapolis, MN n.d.-c). One of several datasets related to shared mobility on Minneapolis’ open data portal. The data appear to be limited to the city’s shared scooter programs.

- Louisville, KY, Dockless Vehicles (City of Louisville, KY n.d.-b). The data appear to be limited to dockless vehicles.

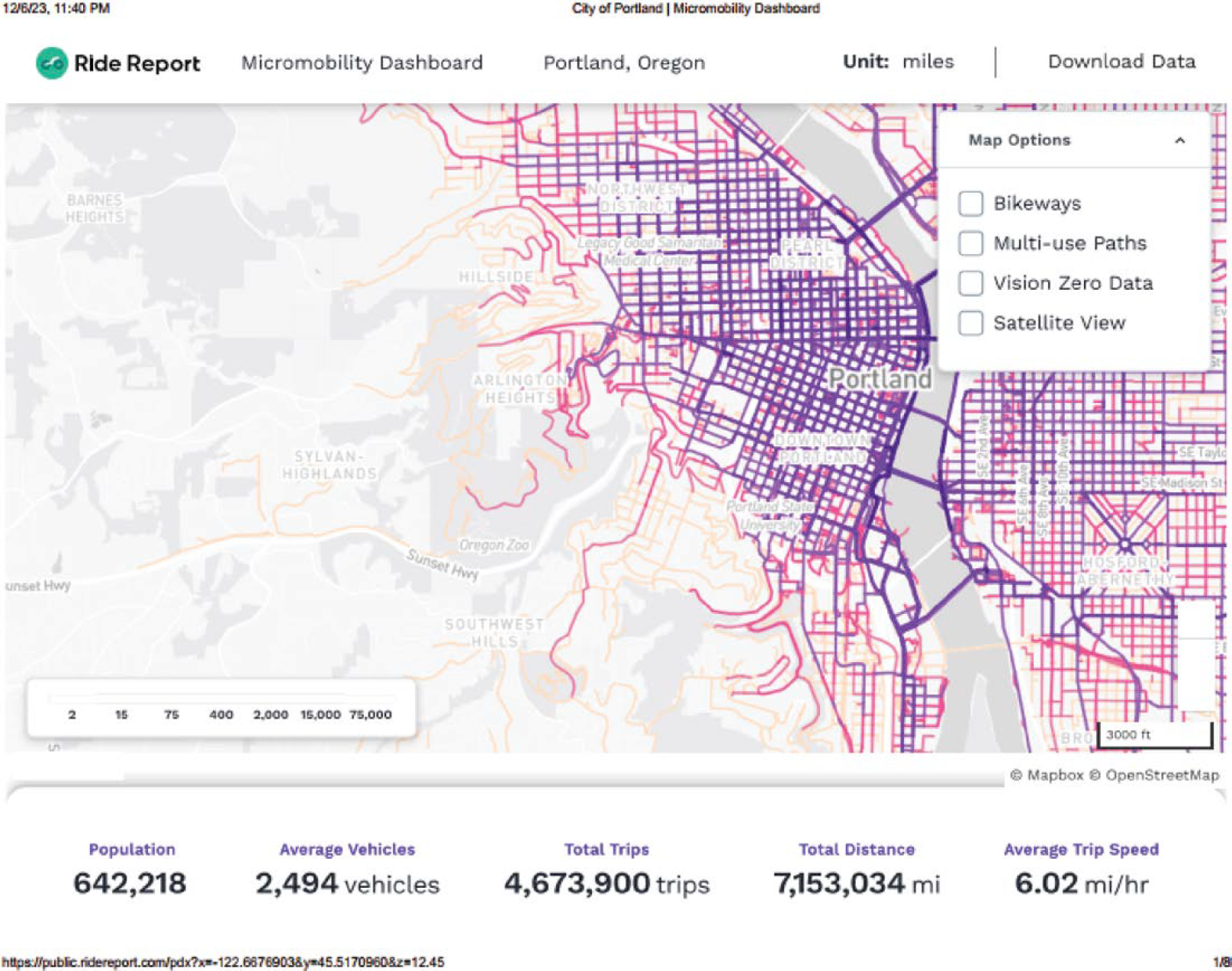

- Portland, OR, Micromobility Dashboard (Ride Report n.d.). This is an example of the types of data dashboard and visualization that can be included in public data portals. A screenshot of one of the visualizations is shown in Figure 13-4. When visualizations and dashboards are being provided, best practice is to also provide access to the underlying data, as Portland does.

Source: Ride Report (n.d.).

Examples of Privacy Principles and Policies

In addition to the global recommendations on privacy principles and policies found in “Privacy Principles for Mobility Data” (NUMO, NABSA, and OMF 2021) and Managing Mobility Data (NACTO and IMLA 2019), there are numerous published examples of specific community principles and privacies that an agency can draw from. Following are a few examples:

- Los Angeles, CA: LADOT Data Protection Principles (City of Los Angeles, CA 2019);

- Minneapolis, MN: Proposed Data Privacy Principles (City of Minneapolis, MN n.d.-b);

- Portland, OR: 2019 E-Scooter Findings Report, “Appendix A: Managing Mobility Data” (City of Portland Bureau of Transportation 2020); and

- San Jose, CA: Shared Micro-Mobility Permit Data Protection Principles (City of San Jose, CA n.d.).

For additional examples, see the list provided by the Open Mobility Foundation’s Mobility Data State of Practice (OMF n.d.-h).

Protection Controls and Methods

This section provides recommendations for controls that agencies should consider putting in place to protect the sensitive data they store and analyze as well as the data they share with others. Like the other sections of this chapter, it is not a deep dive, and readers should seek more information by consulting security and privacy professionals and the literature referenced in this section. In addition, MDSPs need to implement an appropriate subset of these methods to safeguard the data entrusted to them.

The federal Office of Management and Budget defines a security control as “a safeguard or countermeasure prescribed for an information system or an organization to protect the confidentiality, integrity, and availability of the system and its information,” whereas it defines a privacy control as “an administrative, technical, or physical safeguard employed within an agency to ensure compliance with applicable privacy requirements and to manage privacy risks” (Office of Management and Budget, The White House 2016). Some controls are both security and privacy controls, as shown in Figure 13-1. Controls can include administrative aspects, technical aspects, and physical aspects. An extensive list and discussion of controls can be found in Security and Privacy Controls for Information Systems and Organizations (NIST 2020b).

Some of the administrative controls, such as determining the data that are sensitive and the risks posed by their inappropriate use or disclosure, are discussed above. This section discusses some of the main types of privacy controls to consider for sensitive shared mobility data. It is usually both simpler and more effective to develop a system that incorporates privacy protection from the start (privacy by design) than to retroactively add controls and methods later (Mixson 2021).

Access Controls

Agencies should implement controls to limit who has access to sensitive data, including individual trip records and proprietary data. Only those whose job functions give them a legitimate need should be granted access. The same applies to staff at other agencies. Best practices for controlling access include the following (OMF 2020a, NACTO and IMLA 2019):

- Establishing rules for when and why sensitive data can be accessed;

- Providing special training on how to handle such data to those with access;

- Utilizing role-based access control, in which individuals are assigned to roles on the basis of their responsibilities and access is determined on the basis of a set of rules associated with each role. A desirable goal is to limit access to raw, detailed data more heavily, with most staff needing, and having, access only to obfuscated and aggregated data. This applies both to staff within the agency and to external access, such as by other agencies and MDSPs.

Data Retention

Agencies should establish policies for what data need to be retained and for how long those data should be kept. Procedures should be put in place to ensure that data are deleted at the appropriate time. The goal is to keep the minimum amount of data, particularly sensitive data, consistent with use cases and regulatory requirements. Data should be kept only until they are no longer needed for an established use case or until the regulatory retention requirements are met, whichever is longer. For example, LADOT Guidelines for Handling of Data from Mobility Service Providers specifies that “to the extent that Confidential data is used for transportation policymaking, it will be stored unobfuscated for no less than two years and in accordance with the City of Los Angeles Information Handling Guidelines” (City of Los Angeles, CA 2018). When determining data retention requirements, an agency should consider whether its retention needs can be met by retaining only aggregated or obfuscated data, as these datasets are less likely to contain sensitive data. A good rule of thumb when establishing retention policies is that data should be saved for as long as needed but not a minute longer.

In addition to establishing policies, agencies should track all data stores that may include sensitive information and implement routine checks to ensure that the policies are being followed and that data that are no longer required are deleted from all systems.

Encryption

Encryption is the transformation of data into a form that conceals the data’s original meaning to prevent it from being known or used by anyone except authorized users, who have the means to decrypt it (NIST n.d.-a). Encryption may have a role to play in data, especially sensitive data, stored by mobility service providers, MDSPs, and agencies. It may also have a role to play in the exchange of information between entities. Encrypting sensitive data provides protection because, even if an unauthorized person obtains access or intercepts the data transmission, he or she cannot read the data and no sensitive information is revealed. Agencies should consider where to require encryption and how to implement it. For example, Shared Mobility Data: A Primer for Oregon Communities recommends that mobility service providers be required to protect personal data by “using industry accepted encryption” (Trillium Solutions, Inc. 2020). San Jose’s “Shared Micro-Mobility Permit Data Protection Principles” requires that MDSPs encrypt all data, both at rest and in transit, and “apply and support encryption solutions that are certified against U.S. Federal Information and Processing Standard 140-2, Level 2, or equivalent industry standard” (City of San Jose, CA n.d.). The City of Los Angeles places the same requirement on its data solution providers, and LADOT itself encrypts all data it receives through the MDS both at rest and in transit (City of Los Angeles DOT 2020).

Data Desensitization: Anonymization, Data Redaction, Aggregation, and Fuzzing

The concept of collecting only the data that are needed and minimizing the collection of sensitive information is discussed above. However, use cases will almost certainly require the collection and analysis of sensitive information, whether directly by the agency or by the MDSP.

Where use cases permit, and when sharing that data with others, agencies should minimize the risk by desensitizing the data in such a way that they still serve their purpose but are less likely to reveal sensitive information. There are multiple techniques for achieving this, and it is likely that an agency should employ several of these methods.

Anonymization

Anonymization is any process that removes the association between the data and individuals. For most shared mobility applications in public agencies, this is done by having mobility service providers remove (redact) any unique identifiers, especially for customers, before the agency ever receives the data. However, agencies sometimes need data that identify individual taxi and TNC drivers, and these data should be anonymized whenever possible before being shared or publicly released. The safest method is to simply redact the data fields that might be used to identify or re-identify an individual. Sometimes, however, the use case involves analyses that need, for example, to identify which trips were made by each driver, but the driver’s actual identity is not needed. This is often done by replacing a unique identifier (e.g., name, patient number, Social Security number, or credit card number) with a different value that, at least in theory, cannot be reassociated with the individual. However, as seen in the example of the New York City taxi dataset, this must be done correctly, or else re-identification is possible.

A related technique is used when the use of unique, unchanging IDs (e.g., a unique vehicle ID associated with a bike or scooter) may enable someone to recreate a trip chain. A dataset that provided vehicle availability information by location could, by allowing tracing of where vehicles appeared and disappeared, be used to identify trip origins and destinations, which are sensitive data, even in the absence of individual trip data. As discussed earlier, the GBFS switched its use of vehicle ID from a static value to a value that changed at the end of every trip to minimize this threat.

Aggregation

Aggregation is the concept of combining similar data points into groups, or “bins.” This is often a necessary step for several types of analyses, but it also reduces the potential for re-identification. There are multiple tools and techniques for aggregating data, and the best approach will vary, depending upon the specific use case. For many shared mobility use cases, the bins are sized geographically or temporally, or both. The appropriate bin size depends upon the use case. For example, analysis of curb use may require data at the block level. If an agency’s use cases only require aggregated data, the agency can protect sensitive data by aggregating it at the earliest opportunity and deleting the raw data. In other cases, the agency or its MDSP may need to retain raw data for some applications but can aggregate data before sharing it, whether publicly, in response to open records requests; with other agencies; or with law enforcement. For example, while LADOT retains raw data used for transportation policymaking for 2 years, its data protection principles state that “LADOT will aggregate, de-identify, obfuscate, or destroy raw data where we do not need single vehicle data or where we no longer need it for the management of the public right-of-way” (City of Los Angeles 2019). Following are examples of how some agencies aggregate data for various purposes:

- The city of Chicago, for its publicly released open datasets, rounds all start and end times to 15-minute windows and aggregates data geographically by census tract, the smallest of which is about 89,000 square feet, and by community area, which averages 3 square miles in size (City of Chicago, IL 2019).

- The city of Portland aggregates data prior to its own internal use. Portland divides the city into 250-foot squares and remaps the origins and destinations of each trip to the center of

- the square. The city does not store the raw geospatial information (City of Portland Bureau of Transportation 2020).

- LADOT aggregates data for measures such as vehicle counts by status, trips counts, and public right-of-way use. It uses both temporal bins and a variety of geographic bins, depending upon the application. Geographic bins include city council district, census tract, and TAZ. Trip origin and destination data are also aggregated by time by rounding trip start and end times into hourly time intervals. For other applications, trip paths are first split into street segments and then aggregated by time and direction of travel (City of Los Angeles DOT 2020).

- The city of Louisville uses detailed, raw micromobility data internally but aggregates it before releasing it to the public (Bird Cities Blog 2020). Trip start and end times are rounded to the nearest 15-minute increment. The location data, expressed in latitude and longitude, are then truncated to three decimal places, which, for Louisville, results in a grid that is about 100 meters by 80 meters.

- The New York City TLC aggregates pick-up and drop-off to the taxi zones for the city (of which there are several hundred) before releasing the data to the public. They do not aggregate the pick-up and drop-off times (New York City TLC 2021).

- The city of Minneapolis, for its 2018 scooter pilot, rounded all trip start, end, and route polling times to the nearest half hour. Trip start and end points were aggregated by mapping them to a street segment start point, middle point, or end point, whichever was closer. Locations along a trip were trimmed so that only one point was kept per street segment, both to reduce the size of the files and to enhance privacy (City of Minneapolis, MN n.d.-a).

k-Anonymization

Some of the agencies given as examples of aggregating data in the previous subsection also utilize a process called k-anonymization to further protect the data. Aggregation into fixed bins, by itself, will often not provide sufficient protection against re-identification. Once the data are binned, there will be a different number of data points in each bin. If a particular bin includes only a few data points, it poses a risk of re-identification. In the example referenced earlier of the Massachusetts governor’s health records, the combination of zip code, birth date, and male gender for the bin matching the governor’s known public information, which was obtained from voter rolls, produced a bin size of one. This enabled the governor’s medical records to be re-identified (Barth-Jones 2012). The way to reduce this risk is to not report data for bins that contain only a small number of data points. A common approach is k-anonymization, in which data are not provided for bins with fewer than k entries. Unfortunately, there is no general agreement on what value of k to use for shared mobility datasets. Following are some examples of the values and approaches various organizations are using, both for internal use and for publicly released data:

- The City of Chicago uses a k-value of 3 for its published, open datasets related to TNC and taxi trips (City of Chicago, IL 2019). Census tracts with two or fewer values are left blank, but the data are used for reporting at the larger community area level. About one-third of the data at the census tract level end up being redacted by this process.

- The City of Portland further aggregates the data by combining bins if there are fewer than 10 housing units or employment opportunities in the square and remaps the trip origins and destinations to the center of the resulting polygons (City of Portland Bureau of Transportation 2020).

- LADOT appears to currently use a k-value of 10 but provides flexibility in its policy, stating that LADOT “can set ‘k’ to 10 minimum trips per census tract per week” (City of Los Angeles DOT 2020). LADOT analyzes data on both the census tract level and the city district level. It redacts census tract data that do not meet the threshold but includes these data in the city district level.

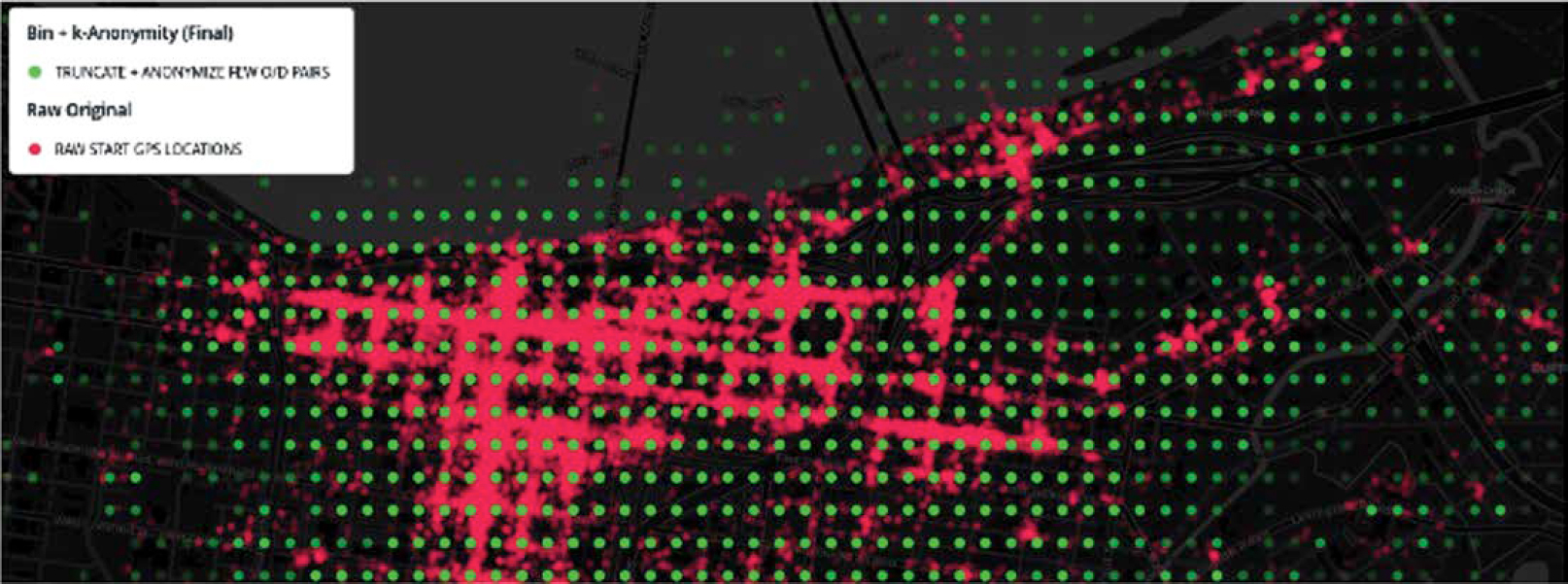

- The City of Louisville, KY, after binning geographically and temporally, uses a k-value of 5 (City of Louisville, KY n.d.-a). Rather than redacting the data or combining bins, it fuzzes the geographic data for origin–destination pairs. For these data points, Louisville moves the location of both the original trip start and trip destination in a random direction by a random distance of up to 400 meters, thereby moving the location by up to five bins. The result is a grid of points with no way to trace a location back to its original location and no way to determine whether a particular record has been binned and fuzzed or just binned, while still maintaining enough accuracy for many use cases. Figure 13-5 illustrates this process. Figure 13-5 shows the starting points (in red) of 100,000 dockless vehicle trips from one provider selected randomly from raw Louisville data and zoomed into downtown for detail. After the locations are binned to about 100 meters, a k-anonymity generalization method is used to arrive at the final open data (point grid in green).

The current version of the MDS provides for two types of aggregated reports: provider reports and metrics. It specifies that service providers should redact any data for bins with fewer than 10 entries (k = 10), and the discussion states that, although values of k = 5 are often used in other applications, a conservative k-value of 10 was selected because shared mobility is a relatively new area. Bins that contain fewer data points than the threshold, including empty bins, are redacted and not reported (OMF n.d.-b).

As the examples given above illustrate, there are several approaches that can be taken when a data bin fails to meet the k-value threshold. The easiest approach is to redact the data and not report on that bin. Doing so, however, also totally discards data and has the most potential to negatively impact analyses. In the LADOT and Chicago examples, the data are not totally discarded, as data are analyzed on two levels of geographic aggregation, and the data are kept at the more aggregated level. Another common approach is to combine bins that fail to meet the threshold with neighboring bins, as Portland does. This adds a level of complexity but keeps all the data, sacrificing a level of detail only when necessary. Finally, another approach is to fuzz the data by changing the values according to a predetermined algorithm in such a way that the data remain useful for analysis, as Louisville does.

Source: City of Louisville, KY (n.d.-a).

Differential Privacy

Differential privacy is an emerging technique for protecting privacy. It provides a mathematical definition for privacy loss associated with a dataset and introduces a certain level of noise into the data. It does this by adding extra information to the dataset in such a way that re-identification becomes more difficult while analyses using the dataset can still produce meaningful results (Burns 2022). Beginning in 2020, the U.S. Census Bureau moved from older techniques such as data redaction, k-anonymization, and swapping (another form of adding noise) to differential privacy (U.S. Census Bureau 2021). Agencies may wish to explore differential privacy and consider using it in the future.

Summary of Protection Controls and Methods

Agencies will likely need to utilize a variety of the protection controls and mechanisms discussed in this chapter to protect sensitive information. LADOT’s “Data Protection Principles/Use and Retention (CF #19-1355)” describes how LADOT implemented many of these techniques, including retention policies, data minimization, encryption, and aggregation and provides examples of mapping defined use cases to data needs (City of Los Angeles DOT 2020). The Open Mobility Foundation’s Mobility Data State of Practice provides links to examples of both policies and practices implemented by agencies to protect sensitive data (OMF n.d.-h).

Summary

Public agencies have a need to obtain data from shared mobility providers. Some of these data may be sensitive because they could reveal either the PII of users of these services or proprietary data, including trade secrets, of the service providers. By implementing appropriate policies and procedures, agencies can appropriately protect sensitive data while using the appropriate data to meet their goals and objectives.

This chapter lays out a process for managing sensitive shared mobility data with recommended best practices for each step. The steps are as follows:

-

Determine data needs.

- Determine the use cases. Agencies should determine what questions, analyses, and actions they need data for; that is, they should define the specific use cases and then identify the data needed to support each use case. Data from mobility service providers may be needed to oversee and regulate operations, for transportation planning and analysis, and to enforce related laws and regulations. When identifying the use cases, agencies should consider internal use cases and uses other agencies may have for the data as well as use cases for publication of data to provide information both to the public and to researchers.

- Determine the data needed for each use case. A basic rule of thumb is to collect only the data that an agency and other internal agencies (e.g., transportation planning offices) need and to collect it in the least sensitive manner. The data elements needed and the fields within each element should be identified. For micromobility, agencies should work from the standardized data elements found in the MDS and the GBFS. For other types of shared mobility, the data structures specified for micromobility services in the MDS and GBFS are still useful guides as to what is needed for the same types of use cases. In addition, an agency can examine what other agencies have found a need to collect. Another question to consider is whether the agency needs raw, detailed data in every case or if some use cases could be met by having mobility service providers send only preaggregated or preobfuscated data.

-

- Identify sensitive data. Determine which data elements and data fields contain proprietary data, PII, or potential PII. Conduct a privacy impact assessment to examine the risks posed by unauthorized access or release of this information and the negative impacts that this would have.

- Develop principles and policies for managing sensitive data. As a starting point, look at consensus statements of principles, such as the “Privacy Principles for Mobility Data” (NUMO, NABSA, and OMF 2021) and Managing Mobility Data (NACTO and IMLA 2019), and at the privacy principles and policies put in place by other agencies across the country. The scope of the policy that an agency develops should include all types of sensitive data as well as how the data are exchanged and internally handled by each entity shown in Figure 13-2.

-

Implement appropriate controls and mechanisms for protecting sensitive data. Determine, implement, and audit the administrative, technical, and physical controls that each entity will put in place to safeguard sensitive information. Consider

- Access controls;

- Data retention;

- Encryption;

- Data desensitization, including anonymization, data redaction, aggregation, and fuzzing; and

- Differential privacy.

By following these practices, agencies can appropriately protect sensitive data, including both personal private data and proprietary data.

Appendix 13-A: Examples of Taxi and TNC Data-Reporting Requirements and Publicly Released Data

There are currently no established industry standards for service providers sending information to public agencies (although the Open Mobility Foundation has begun work to expand the Mobility Data Specification to handle these types of services). Examples of what other agencies are requiring may assist an agency in determining both the use cases and data needs for overseeing these types of services. Listed below are links to several examples of data-reporting requirements that public agencies have placed on taxi companies and transportation network companies (TNCs), along with links to publicly released analysis and datasets from these agencies.

Data-Reporting Requirements

- The California Public Utilities Commission’s reporting requirements for TNCs (CPUC n.d.).

- Chicago’s rules for transportation network providers, including reporting requirements (City of Chicago, IL 2020b), along with the city’s detailed TNP Reporting Manual (City of Chicago, IL 2020a).

- Seattle’s data-reporting requirements for taxis and TNCs (City of Seattle, WA n.d.).

- The New York City Taxi and Limousine Commission’s reporting requirements (New York City TLC 2021). The data are collected on both taxis and for-hire vehicles (FHVs), with TNCs as a subset of FHVs.

Publicly Released Analyses and Datasets

- Aggregated and summarized data on TNCs from the California Public Utilities Commission (CPUC 2015).