Data Integration, Sharing, and Management for Transportation Planning and Traffic Operations (2025)

Chapter: 9 Vehicle Probe Data Primer

CHAPTER 9

Vehicle Probe Data Primer

Transportation agencies have historically relied on intelligent transportation systems (ITS) technology to provide the information needed to plan for and operate their facilities. ITS infrastructure has been used to monitor traffic volumes and speeds, detect traffic incidents, and provide traveler information. The use of ITS infrastructure for these and other applications requires significant investment in deployment and maintenance to provide adequate system coverage and reliability.

State and local transportation agencies are increasingly turning to vehicle probe data, which provide more reliable traffic speed data over a wider geographic area as compared with traditional ITS infrastructure. In doing so, agencies are improving their ability to plan for and operate their transportation systems. For example, the National Performance Management Research Data Set (NPMRDS), a national database of archived vehicle probe speeds, is used by state departments of transportation (DOTs) to meet federal requirements of monitoring and reporting congestion and freight performance enacted in the Moving Ahead for Progress in the 21st Century Act (MAP-21). Agencies use vehicle probe data in real time to deliver quantitative traveler information, detect roadway incidents, monitor work zone queuing, and support broader situational awareness. They access archives of vehicle probe data for many uses, such as more cost-effective before-and-after studies, traffic signal timing, project prioritization, and investment decisions.

Vehicle probe data include information from mobile cellular devices, fleet vehicles with embedded Global Positioning System (GPS) devices, connected vehicle telematics, and mobile applications (e.g., cell phone, tablet) that track user location. These data, which are typically provided by third-party vendors who capture, manage, analyze, and anonymize the data, provide cost-effective visual and numeric information throughout the transportation system that is not limited to facilities with traditional sensor devices.

This chapter is intended to serve as a primer on vehicle probe data, including the sources and applications for probe data, the challenges agencies need to address to effectively use the data, and current and future opportunities for using vehicle probe data. The chapter is organized into the following sections:

- Data Availability,

- Data Uses,

- Data Management,

- Data Quality,

- Data Integration,

- Agency Vehicle Probe Data Applications, and

- Future of Vehicle Probe Data.

Of note, probe data related to pedestrians, bicyclists, micromobility, and other transport modes constitute an emerging area. The availability, management, quality, integration, and use considerations of emerging probe data may be significantly different and are not covered in this chapter.

The references cited are listed at the end of the chapter.

Data Availability

Vendors of vehicle probe data offer numeric and visualization products for road segment speed, origin–destination (O-D) proportions, and vehicle trajectory. Real-time, minute-by-minute, speed and travel time data are available along with historical average speeds for freeway and arterial road segments from vendors. Data fields for numeric speed probe data typically include the following:

- Reference speed (expected speed on a segment without traffic);

- Estimated (current) average speed;

- Historical average speed;

- Time required to travel across a segment;

- Road segment [traffic message channel (TMC) segment (TMCid) or XD segment (XDid)];

- Congestion level (relationship between volume and capacity);

- Score, which represents the source of speed data (historical or real-time); and

- Confidence level for real-time data.

Providers of vehicle probe data also make traffic tiles available in real time. Traffic tiles are visual images that contain color-based congestion graphics that can be layered on top of map tiles. Traffic tiles are typically used on traveler information sites.

Vendors also offer probe-based O-D data that include an estimate of the proportion of trips between geographic zones. Data provided on the number of trips between zones are based on regional modeling. Likewise, while some vendors offer vehicle volume or vehicle type compositional data, these are modeled estimates and not ground truth as measured by roadway sensors. Providers of vehicle probe data are also challenged with lane-specific speed estimates, such as distinguishing speeds in high-occupancy vehicle (HOV) and general-purpose lanes.

Data Uses

There is a variety of uses for vehicle probe data. Real-time applications are generally focused on the operation and management of facilities through monitoring, detection, trend analysis, and route assessment. Using vehicle probe data to monitor traffic in real time or near real time can provide operators and travelers with timely information on traffic conditions. Speed data can support winter weather operations and the detection of traffic incidents. These data can be used to monitor the impacts of work zones and detect the end of the traffic queue. They also help operators manage evacuations and other significant events. Freeway service responders can monitor these data to support their routing and response.

Real-time traffic data can be analyzed to notify traffic management center operators of potential incidents. This information is based on detected changes in traffic speeds and significant changes in traffic patterns. Used in conjunction with traditional monitoring devices such as cameras, these data help traffic management center operators make more timely and informed response decisions. Monitoring congestion in real time allows agencies to provide travelers with travel time information on their current route or direct them to alternative routes. Speed, O-D, and

trajectory data can be displayed in real time on dashboards to allow effective system monitoring and operations.

Archived data are used for a variety of critical transportation agency functions, including performance management, planning, investment and programming decisions, and research. Performance management evaluates system performance metrics over time to support operations, management, planning, and investment decisions. Travel time, reliability, bottleneck locations or hot spots, and changes in vehicle trajectory trends can be used to support system planning and project planning. Historical patterns and changes can be measured and reported to support system planning and investment prioritization through automated reporting, dashboards, heat maps, O-D data, and trajectory maps and regional or systemwide bottleneck mapping. Travel times, reliability measures, and bottleneck locations can inform project planning and development by providing insights into potential alternative solutions.

Speed, O-D, and trajectory data can also be used for traffic signal studies. Vehicle probe data, including approach speeds, intersection delay, and speeds through the intersection, can inform the timing and operation of signalized intersections. Research applications of vehicle probe data include O-D analysis, waypoint analysis, safety studies, evaluation of truck operations and policies, and multimodal studies. Other studies that use vehicle probe data include before-and-after studies that evaluate infrastructure projects and after-action reviews of major traffic incidents.

The research for NCHRP Synthesis 561: Use of Vehicle Probe and Cellular GPS Data by State Departments of Transportation conducted a survey of state DOTs and found that 88% of agencies use vehicle probe speed data for federal performance reporting (Pack and Ivanov 2021). It identified the following common uses of vehicle probe and cellular GPS data:

- Corridor studies,

- Reliability measurement,

- Bottleneck ranking,

- Traveler information,

- Before-and-after studies,

- Model calibration,

- Travel time on dynamic message signs (DMS),

- Situational awareness,

- After-action incident reviews,

- O-D analytics,

- Real-time work zone management,

- Arterial performance measures,

- Project prioritization and scoring, and

- User delay cost analysis.

Table 9-1 shows the percentage of DOTs that indicated specific uses of these data. Of note: these percentages are likely far greater now than in year 2020, when the survey was conducted.

Data Management

Vehicle probe data and other emerging data sources create new data management challenges for transportation agencies. These big datasets require a transition from traditional data management practices to more modern data management practices to handle the enormous amount of data. NCHRP Research Report 952: Guidebook for Managing Data from Emerging Technologies for Transportation offers a big data management framework and roadmap to help transportation agencies shift from traditional data management to modern systems that can effectively manage

Table 9-1. Uses of vehicle probe and cellular GPS data in 2020.

| Use by State DOTs | Percentage of States |

|---|---|

| Planning | 42 |

| Performance management | 41 |

| Real-time operations | 35 |

| Research | 26 |

| Public relations/media | 14 |

| Maintenance | 9 |

| Asset management | 3 |

the increasing data available from emerging technologies (Pecheux et al. 2020). Agencies must consider how they will access, store, analyze, and share big datasets available from vehicle probe data. This often requires the acquisition and application of new systems, resources, and capabilities or reliance on third-party contractors or vendors for data management.

Access and Sharing

Vehicle probe data can be used to support a data-driven agency culture that uses access tools and applications. Vendors of third-party vehicle probe data offer web and mobile applications to provide real-time traffic data through REST APIs, an application programming interface used to control data access. [A REST API is an application programming interface (API) that conforms to the design principles of the Representational State Transfer (REST) architectural style.] These APIs provide access to traffic data, including speeds, safety alerts, routing, and traffic cameras; web services such as geocoding and search, routing, tracking, and positioning; and suites of services designed to allow developers to create web and mobile applications. These data feeds can be accessed online with proper credentials and authentication.

The extent to which vehicle probe data can be shared beyond the agency purchasing the data is a function of the procurement agreement. Some agreements enable the procuring agency to share the unprocessed data with research and consultative services, while others may extend data sharing between a state and its local public entities. Agreements may also specify data use attributions in the processing and visualizing of vehicle probe data as well as in integrating these data with other agency data.

Storage and Analytics

Managing big data in transportation agencies can be done internally on agency servers, in the cloud by using cloud services, or by third-party data consolidators. Various tools are used for distributed storage and processing of big data—a collection of open-source or proprietary systems designed to run on group services and distribute large-scale data analytics.

Commercial cloud services and third-party data managers have a market presence and are now more frequently used by DOTs. Traditionally, agencies relied on solutions such as relational database management systems (RDBMS), commercial database management software, and Structured Query Language (SQL) to manage, integrate, and analyze data. The decision to use a specific data management tool varies by the agency’s use cases, policies, and capabilities. Agencies can use a variety of proprietary and open-source tools to develop in-house applications. More recently, data management solutions also provide analytics and visualization features; thus, storage and analytics may need to be considered together to find a cost-effective solution of the right size. There are also off-the-shelf third-party tools for managing and analyzing vehicle probe data, each offering different latencies and analytics.

Privacy and Security

Privacy and security are necessary considerations for nearly all transportation data and analytics. Vehicle probe data are typically sourced and anonymized by private entities that aggregate data both from the perspective of the individual traveler and the enterprise providing data (e.g., a commercial fleet operator). Thus, public agencies that access vehicle probe data generally do not need to take additional steps to address privacy concerns from the perspective of identity (e.g., driver license, name, vehicle registration number), behavior (e.g., frequency or timing of trips from origin to destination of an individual or enterprise), and location (e.g., physical and temporal position of a vehicle or individual).

While ITS has both physical and information security considerations, considerations regarding the security of vehicle probe data center on information security associated with acquiring, storing, using, and sharing these data. These considerations are no different from security considerations for any real-time streaming or archived data and protocols. Secure use of these data should be consistent with broader agency protocols for security.

Data Quality

One of the most common concerns transportation agencies have with the use of vehicle probe data is the quality of the data. Each vendor of vehicle probe data has its proprietary approach to collecting, managing, and analyzing the data, making data source and integration a black box. Data quality may vary by roadway facility and time of day. Agencies have addressed this challenge by performing assessments of data quality and validity to evaluate the quality of the data, mainly as it relates to travel speed and time. Currently, there is no reliable way of assessing O-D or trajectory data. The Eastern Transportation Coalition (TETC) is looking at this issue from the perspective of quality assurance and quality control rather than that of field data collection. The National Household Travel Survey or a travel demand model can be used to assess O-D data, although the comparisons are not appropriate for calculating quantitative error measures.

Many states have performed ad hoc comparisons of vehicle probe speed and congestion data against spot sensor data or Bluetooth reader data. Vendors may not notify agencies when their data sources or integration change, which changes the quality of the vehicle probe data. Consequently, shifts in data quality may go unnoticed unless the agency conducts routine assessments.

A few providers of vehicle probe data now procure connected car data to complement their traditional GPS-based individual vehicle or fleet-based data. This additional source data accessed by some vendors of vehicle probe data has likely enhanced the quality and geographic coverage of their data; thus, older quality assessments may not reflect the data quality and validity of current vendor products. Following are examples of data assessments by TETC and Iowa State University.

The Eastern Transportation Coalition

TETC (formerly the I-95 Corridor Coalition) began its Transportation Data Marketplace with the Vehicle Probe Project in 2008 to support coalition members’ ability to acquire reliable, real-time travel time and speed data without relying on sensors and other ITS installations (Haghani et al. 2009). TETC continues to evaluate commercial probe data on both freeway and arterial facilities through its Transportation Data Marketplace and provides data validation reports dating from 2009 to current study reports (TETC n.d.). The data validation program focuses on ensuring the quality and accuracy of traffic data through independent evaluation of the data. It collects data in the field, processes the data to establish ground truth traffic conditions, and compares the data with data reported by vendors through the Transportation Data Marketplace.

The validation process uses wireless re-identification traffic monitoring (WRTM) sensors placed in defined roadway segments to collect data. Travel time and speed data are validated by using a sample of vehicles passing the sensors and comparing it with travel time data provided by the vendors. TETC deploys portable WRTM sensors on selected road segments to collect unique electronic signatures [media access control (MAC) IDs] from in-vehicle electronic equipment. The sensors record and time-stamp the MAC ID as the vehicle passes. Each sensor has an embedded GPS location device that enables it to be precisely located. The data are uploaded and analyzed from a series of sensors to establish travel time samples. TETC started the travel time validation on freeway segments and is increasing its emphasis on arterials and in other complex traffic flow scenarios. TETC’s Traffic Data Market Place Data Validation Program 2021 Version 2.0, provides an overview of the validation process and methods (TETC 2021). In addition to travel time, speed, slow down, and latency measures, the document lays out an approach (not currently in place) for developing traffic volume validation. It discusses considerations for validating additional datasets, such as O-D data.

Iowa State University

In Evaluation of Opportunities and Challenges of Using INRIX Data for Real-Time Performance Monitoring and Historical Trend Assessment, Sharma and colleagues (2017) looked at the opportunities and challenges of using INRIX data in Nebraska. They evaluated the reliability and accuracy of the data streams by comparing them with fixed sensor data and reporting real-time and historical trend assessments. The assessment of INRIX data considered the availability of data, speed bias between datasets, incident detection and detection latency, and performance measures such as hours of congestion, buffer time index, and reliability. The study outlines findings from a literature review and data assessment at 16 sites along Nebraska Department of Roads facilities. The researchers found that confidence scores for speed data were high on Interstates and lower on non-Interstates. Additionally, daytime confidence levels were generally higher than for nighttime data. The study reported several advantages and limitations of the INRIX data and found that the data for geographic coverage on and off Interstates were reliable. INRIX was determined to be reliable for detecting incidents and congestion, although there were latency issues. Study recommendations on the use of probe data noted that it is important for DOTs to conflate probe data segments to a linear referencing system; consider the granularity of probe data needed to support the intended use, such as incident detection; be aware of reliability difference by the time of day, biases in traffic speed data, and latency issues; and be prepared to handle a very large volume of data.

Data Integration

Integrating vehicle probe data with agency road network data, advanced traffic management systems (ATMS), and other data systems is one of the most significant deterrents to its use by state DOTs. To be useful, vehicle probe data must be conflated temporally and spatially to a roadway network. Initial commercial offerings relied on TMC codes. TMC codes communicate location by breaking the roadway network into links and nodes. Commercial traffic data providers use TMC codes to relay traffic data with low-bandwidth channels. Using TMC codes to integrate vehicle probe data into agency databases or traffic management software can be a challenge. Segment lengths may offer a level of granularity that may not be useful for certain applications. TMC codes may not be available for all roadway types or may omit newer roads. These issues can make it difficult to conflate the data to an agency’s GPS data. Vehicle probe data may also provide more precise location information than the agency’s linear referencing system (Pack and Ivanov 2021).

To address these limitations, traffic data vendors have developed and control alternative segmentation schemes to be more responsive to their clients, including creating new segments quickly and with higher granularity. However, these vendor-specific schemes are not standard, may be proprietary, and may not be easily ported to new data sources or maps (FHWA n.d.-a).

Integration of vehicle probe data with other programmatic and enterprise data systems provides an opportunity to enhance operations and decision-making with real-time and archived data. The TETC Data Marketplace uses a provider that supports data conflation. Areas for integration in transportation agencies include performance management, work zone management, incident detection and situational awareness, and asset management.

Agency Vehicle Probe Data Applications

State and local DOTs are using vehicle probe data from a variety of sources for a variety of applications. This section highlights vehicle probe data applications for three agencies: the Indiana DOT (INDOT), Tennessee DOT (TDOT), and the District of Columbia DOT (DDOT).

Indiana DOT

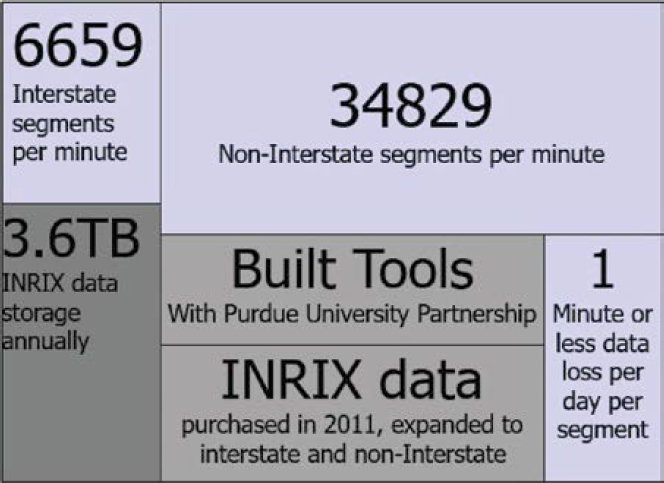

INDOT has used INRIX data since 2011 to support a variety of functions on freeways and roadways on and off the Interstate system. INDOT archives data for more than 6,600 Interstate road segments as well as nearly 35,000 non-Interstate road segments every minute from INRIX, resulting in nearly 4 terabytes of annual data, as illustrated in Figure 9-1. The data are used for situational awareness, incident detection and monitoring, work zone monitoring, snow and ice management, signal timing, travel time calculations, and selection of capital projects. INDOT worked with Purdue University to develop a custom suite of tools that is also used by law enforcement officers to monitor work zones. The agency is developing applications for variable speed limits and ramp metering.

The adoption of vehicle probe data has provided numerous benefits and cost savings to INDOT. The data have allowed INDOT to significantly increase the geographic area and density of monitoring, reduce incident detection times, provide quantitative traveler information, and improve operational capabilities. In 2020, INDOT increased the number of individual travel

Source: Cox (2020).

time calculations reported to travelers. At that time, travel times were calculated with only one probe data source. Since then, the department has worked to blend field devices and two probe data sources for enhanced reliability. An INDOT tool integrates traffic flow and probe data to estimate freeway delay and rank the slowest interchanges. These data are used to inform investment decisions in capital projects (Young 2016).

INDOT uses vehicle probe data to support traffic signal timing. These data are used for performance-based prioritized signal retiming and have replaced costly floating car studies, traditionally conducted on a 3- to 5-year cycle for corridor retiming. The benefits of this approach are evident in an arterial retiming project on US-31. The DOT’s cost–benefit analysis for this effort found savings of 116,000 hours of travel time, equivalent to $2.75 million, and a 980-ton reduction in carbon dioxide emissions, equivalent to $21.5 thousand.

Through using vehicle probe data, INDOT has realized significant cost savings, eliminating 130 existing and 650 planned roadside infrastructure sites. This resulted in $28 million in cost savings on infrastructure deployment and savings of $750 thousand per year on communications and maintenance costs (Cox E. 2020).

Tennessee DOT

TDOT began using live INRIX probe data and the Regional Integrated Transportation Information System (RITIS) Probe Data Analytics Suite in 2020. In 2021, a routine inspection of the I-40 Hernando DeSoto bridge over the Mississippi River found significant cracks in the structure. The emergency bridge closure necessitated the implementation of a 2-month detour for approximately 40,000 daily users traveling on I-40 between Arkansas and Tennessee. Working with the Arkansas DOT (ARDOT), TDOT used crowdsourced data to complement ITS technologies to inform travelers and improve travel reliability and safety. RITIS Probe Data Analytics and INRIX vehicle probe data were used to review travel time and congestion analytics to develop diversion routes. Throughout the 2-month bridge closure, daily meetings of staff from FHWA, ARDOT, the City of Memphis, TDOT, and other affected agencies were held to review traffic flow, congestion, and event data. This monitoring and review of ITS and probe data supported collaborative signal-timing plans, adjustments to lane configurations, timely response to incidents along the diversion route, and enhanced interagency coordination. The experience of using crowdsourced data for the emergency diversion of I-40 initiated a broader use of probe data as an important part of TDOT’s approach to regional traffic management and operations (FHWA n.d.-b).

District DOT

DDOT uses INRIX XD and TMC data to support the management and operations of Interstates, freeways, and arterials. It uses real-time data to monitor travel times and speeds and archived data to support the District Mobility study, report quarterly key performance indicators, inform future infrastructure investment decisions, identify locations for automated speed enforcement, and for broader planning and operations applications. DDOT uses vehicle probe data through RITIS, Google Traffic, Waze, floating car/GPS, bicycle travel time, and other data with a Synchro simulation model to retime the network. The agency maintains an internal data lake for Waze alerts and traffic jams and a Mobility Data Specification (MDS) for bike and scooter–share data. DDOT reported an annual savings of $2.4 million in mainline traffic delay and $5.8 million for all traffic approaches.

The DDOT Data Governance Council meets regularly to advance data accessibility across the agency. Traffic monitoring uses RITIS and DDOT ATMS, with queries and analysis primarily through the RITIS Probe Data Analytics Suite and Tableau. Training is offered in lunch-and-learn

training sessions and informally among staff to enhance internal awareness of tools for additional use cases. DDOT’s lessons learned related to data procurement note the importance of very clearly defined use cases and sufficient, capable resources for data storage, processing, and analysis. The agency found that speed is not a proxy for volume and that the aggregation of speeds and predefined roadway segments can limit the ability to view more granular time/space trends. In general, DDOT found that vehicle probe and broader crowdsourced data can complement traditional data collection but do not replace it (“Probe Vehicle Data—DC’s Experience,” FHWA Every Day Counts Round 5, Crowdsourcing Vehicle Probe Peer Exchange, unpublished presentation, Sept. 24, 2020).

Future of Vehicle Probe Data

Vehicle probe data have become available at greater geographic fidelity and data quality as vendors ingest greater volumes and diverse sources of data. These diverse sources may include

- Traditional personal vehicle and fleet sources, including transportation network companies (TNCs),

- Connected car data from original equipment manufacturers (OEMs) and from OEM-data integrators, and

- Navigation applications.

Commercial connected car data products include real-time and historical traffic information, vehicle movements and O-D patterns, and event information such as seatbelt or windshield wiper use. The addition of new products and partnerships with vehicle manufacturers continues to grow. The evolution of vehicle probe data means continued integration of new data sources and provision of analytics services for greater precision and accuracy of speed, trip, and path data. Moreover, some data generators (e.g., TNCs, navigation app providers) also may make available their data and analytics as a product directly to transportation agencies. To be sure, the present and future of vehicle probe data are no longer limited to vehicle probes, but rather encompass a large set of diverse data integrated and curated by vehicle probe providers using proprietary black box processes.

These vendors offer new and expanded applications of vehicle probe data, such as approximate traffic volume and fleet composition. Other future applications will determine lane-specific speeds and other more granular data applications. These advances will continue to enhance the usefulness of vehicle probe data for real-time operations, system planning, and investment prioritization.

References

Cox, E. (2020). Indiana DOT Crowdsourcing Business Case. Adventures in Crowdsourcing Webinar Series: Business Case for Crowdsourced Data. https://transportationops.org/ondemand-learning/adventures-crowdsourcing-business-case-crowdsourced-data.

FHWA. (n.d.-a). Crowdsourcing for Operations Case Study: Indiana Department of Transportation. FHWA-HOP-20-053. https://www.fhwa.dot.gov/innovation/everydaycounts/edc_6/docs/crowdsourcing_case_study_indiana.pdf.

FHWA. (n.d.-b). Crowdsourcing for Operations Case Study: Tennessee Uses Crowdsource Data to Collaborate and Improve Travel During the I–40 Bridge Repair. FHWA-HOP-22-048. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Transportation. https://www.fhwa.dot.gov/innovation/everydaycounts/edc_6/docs/crowdsourcing_case_study_tennessee.pdf.

Gettman, D., Toppen, A., Hales, K., Voss, A., Engel, S., and El Azhar, D. (2017). Integrating Emerging Data Sources into Operational Practice: Opportunities for Integration of Emerging Data for Traffic Management and TMCs. FHWA-JPO-18-625. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Transportation, FHWA. https://transportationops.org/publications/integrating-emerging-data-sources-operational-practice.

Resources

NCHRP Synthesis 561: Use of Vehicle Probe and Cellular GPS Data by State Departments of Transportation (Pack and Ivanov 2021)

This synthesis provides a summary of how different transportation agencies are applying vehicle probe and cellular GPS data for monitoring, planning, and real-time information. Additionally, the report provides short case examples from a diverse set of agencies covering a wide range of topics.

NCHRP Research Report 952: Guidebook for Managing Data from Emerging Technologies for Transportation (Pecheux et al. 2020)

This guide focuses on assisting transportation agencies in applying large datasets from emerging technologies and sources, such as connected vehicles and mobility data initiatives.

Considerations of Current and Emerging Transportation Management Center Data (Pack et al. 2019)

https://ops.fhwa.dot.gov/publications/fhwahop18084/fhwahop18084.pdf

This FHWA report looks at using emerging data from third parties for transportation management. Fundamental considerations include what data are available, private-sector data sources and their business models, and possible data use cases.

The Eastern Transportation Coalition Transportation Data Marketplace

https://tetcoalition.org/projects/transportation-data-marketplace/

This website provides users with contract documents and coverage information, data validation reports, and other reference documents and presentations related to vehicle probe data.

Vehicle Probes and Crowdsourced Data (ITS JPO 2020)

https://www.itskrs.its.dot.gov/sites/default/files/doc/08_Crowdsourced%20Data_FINAL_12_04_20.pdf

This ITS Deployment Evaluation Executive Briefing provides an overview of probe and crowdsourced data, their benefits and costs, best practices, and case studies. It includes links to more-detailed studies and sources for the information provided.

Integrating Emerging Data Sources into Operational Practice:

Opportunities for Integration of Emerging Data for Traffic Management and TMCs (Gettman et al. 2017)

https://transportationops.org/publications/integrating-emerging-data-sources-operational-practice

This FHWA report, the second in a three-part series, looks at how big data tools and technologies can be used for traffic management, assesses the use of connected vehicle and traveler-related data, analyzes the impacts of data sharing and agency processes and systems on system performance, and discusses challenges to and options for data management.

Integrating Emerging Data Sources into Operational Practices: Capabilities and Limitations of Devices to Collect, Compile, Save, and Share Messages from CAVs and Connected Travelers (Sumner et al. 2018) https://rosap.ntl.bts.gov/view/dot/34985

This FHWA report is the third in a series that looks at the integration of emerging data into transportation operations. It focuses on how data may be handled, future capabilities and future needs for traffic management, and the capabilities required to aggregate, assimilate, and transfer data from roadside units to traffic management centers.

Work Zone Performance Measurement Using Probe Data (Mudge et al. 2013)

https://ops.fhwa.dot.gov/wz/resources/publications/fhwahop13043/fhwahop13043.pdf

This FHWA report assesses the potential of vehicle probe data for use in work zone monitoring and presents summaries of projects that made use of probe data for work zone performance measures or examined the capabilities and limitations of vehicle probe data.

FHWA Every Day Counts Rounds 5 and 6 Adventures in Crowdsourcing Webinars

https://transportationops.org/edc6/adventures-crowdsourcing-webinar-series

These webinars focus on the use of crowdsourced data, such as vehicle probe data, for advancing transportation operations. The following webinars are pertinent to the use of vehicle probe data: July 2022; August 2022; August 2021; October 2020; September 2020; August 2020; April 2020; and February 2020.

Haghani, A., Hamedi, M., and Sadabadi, K. F. (2009). I-95 Corridor Coalition Vehicle Probe Project: Validation of INRIX Data July–September 2008. I-95 Corridor Coalition. https://tetcoalition.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/02/I-95-CC-Final-Report-Jan-28-2009.pdf.

ITS JPO (Intelligent Transportation Systems Joint Program Office). (2020). Vehicle Probes and Crowdsourced Data. ITS Deployment Evaluation Executive Briefing. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Transportation. https://www.itskrs.its.dot.gov/sites/default/files/doc/08_Crowdsourced%20Data_FINAL_12_04_20.pdf.

Mudge, R., Mahmassani, H., Haas, R., Talebpour, A., and Carroll, L. (2013). Work Zone Performance Measurement Using Probe Data. FHWA-HOP-13-043. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Transportation, FHWA. https://ops.fhwa.dot.gov/wz/resources/publications/fhwahop13043/fhwahop13043.pdf.

Pack, M. L., and Ivanov, N. (2021). NCHRP Synthesis 561: Use of Vehicle Probe and Cellular GPS Data by State Departments of Transportation. Washington, D.C.: Transportation Research Board. https://www.trb.org/Publications/Blurbs/181749.aspx.

Pack, M. L., Ivanov, N., Bauer, J. K., and Birriel, E. (2019). Considerations of Current and Emerging Transportation Management Center Data. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Transportation, FHWA. https://ops.fhwa.dot.gov/publications/fhwahop18084/fhwahop18084.pdf.

Pecheux, K. K., Pecheux, B. B., Ledbetter, G., and Lambert, C. (2020). NCHRP Research Report 952: Guidebook for Managing Data from Emerging Technologies for Transportation. Washington, DC: Transportation Research Board. https://www.trb.org/Publications/Blurbs/180826.aspx.

Sharma, A., Ahsani, V., and Rawat, S. (2017). Evaluation of Opportunities and Challenges of Using INRIX Data for Real-Time Performance Monitoring and Historical Trend Assessment. Lincoln: Nebraska Department of Roads. https://dr.lib.iastate.edu/server/api/core/bitstreams/114085fd-2e03-4904-852c-2875c4f2fc19/content.

Sumner, R., Gettman, D., Toppen, A., and Obenberger, J. (2018). Integrating Emerging Data Sources into Operational Practices: Capabilities and Limitations of Devices to Collect, Compile, Save, and Share Messages from CAVs and Connected Travelers. https://rosap.ntl.bts.gov/view/dot/34985.

TETC (The Eastern Transportation Coalition). (2021). Traffic Data Market Place Data Validation Program 2021 Version 2.0. College Park, MD. https://tetcoalition.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/02/2021-ETC_TDM_Validation_Attachment_V2-00_FINAL.pdf.

TETC. (n.d.). Transportation Data Marketplace. https://tetcoalition.org/projects/transportation-data-marketplace/.

Young, S. (2016). Traffic Message Channel Codes: Impact and Use within the Coalition. Presentation. https://tetcoalition.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/02/YOUNG_TMC_Presentation_V5B_201605_MAY_11.pdf?x70560.