Enhancing Airport Access with Emerging Mobility (2025)

Chapter: 7 Strategizing and Planning Airport Access

CHAPTER 7

Strategizing and Planning Airport Access

Developing an Airport Access Strategy

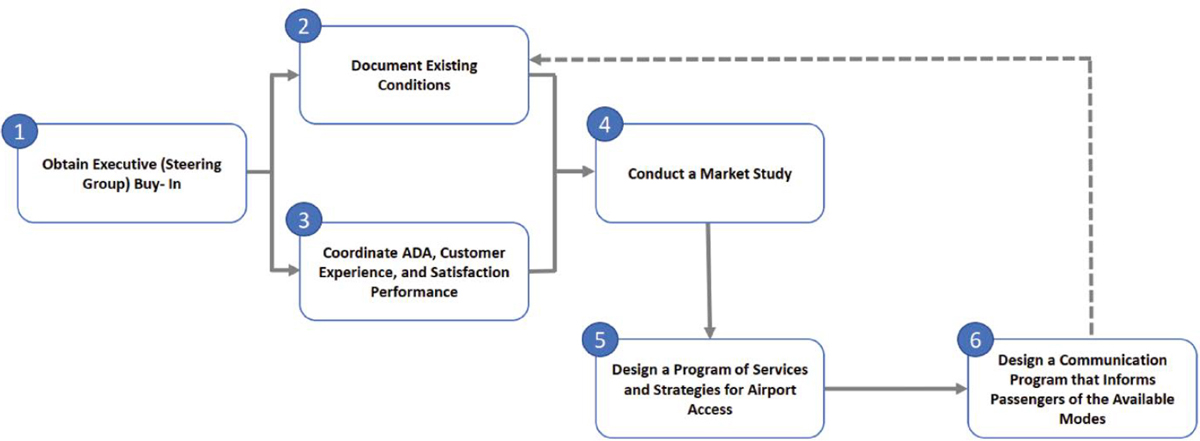

In the passenger transportation system, the role of airports as interchange nodes—where local and regional transportation systems interface with those for national and international travel—is critical. Planning to incorporate new ground access modes brings new stakeholders to the discussion table, which in turn brings more challenges, as more voices and a more diverse set of priorities need to be addressed. In response, MarketSense Consulting LLC et al. (2008) recommend developing a market-based strategy for airport ground access. This process can be expanded to address the challenges of emerging modes and technologies. The revised process is depicted in Figure 53 and features six steps:

- Obtain executive (steering group) buy-in. This step requires identifying the key stakeholders, bringing them to the project group, gaining agreement on the public policy goals of the proposed policies, and establishing a basic understanding of the local ground access context. These stakeholders should represent the airport and transportation operators, while state departments of transportation (DOTs), local governments, and metropolitan planning organizations (MPOs) may be involved depending on whether the ground transportation initiative will be local or regional. During this phase, strategic goal-setting performance metrics (e.g., travel time, level of service [LOS], accessibility, and affordability) and operational objectives should be set.

- Document existing conditions. The project group should identify and gather relevant information that relates to existing infrastructure for these ground access modes; this allows for proper communication, cooperation, and coordination to occur. Airport master plans require an inventory of existing conditions for both physical attributes and operational and performance characteristics of the airport, as well as related facilities and infrastructure. The inventory of existing conditions includes documenting any ground access infrastructure and identifying existing operators, if applicable.

|

Strategic goals. High-level goals for the desired end-state of airport access at the visible horizon. They address the following questions: How can we improve airport access? What are our focuses? What do we want to achieve? |

|

Operational objectives. These objectives translate the strategic goals into practical, implementable targets that are going to structure the strategic plan. They address the following questions: What should we do first to achieve the strategic goals? What are our priorities for the years to come? |

Source: MarketSense Consulting LLC et al. (2008); Le Bris et al. (2021)

- Coordinate ADA, customer experience, and satisfaction performance. The inclusion of all travelers in program design and implementation allows the airport to show its commitment to accessibility and equitable services for travelers with disabilities, older adults, and families with young children. To do so, the project group should include representation of all traveler segments in program design and implementation. This includes a disability advisory board; Van Horn et al. (2020) have developed guidelines on setting up these boards.

-

Conduct a market study. Create surveys to reveal key market characteristics that highlight an accurate market segmentation for air passengers, airport employees, and general visitors. Key market data that could be provided by surveys include exact origin of the ground access trip (when passengers are willing to share this information), time of day and day of the week, trip purpose, and demographics. These market segments can be applied as an approach to predicting behaviors. As analyzed in ACRP Report 4: Ground Access to Major Airports by Public Transportation (MarketSense Consulting LLC et al. 2008), successful strategies offer a variety of public-mode services at various prices.

- At a given airport, a multi-stop bus service for less than $5 will appeal to a different market than a door-to-door shared-ride service for $20. At Baltimore/Washington International Thurgood Marshall Airport (BWI) during peak hours, travelers are offered multi-stop Maryland Area Regional Commuter (MARC) rail services to Union Station for $5 or Amtrak Acela service for more than $30. Some travelers will choose the first train out (at the higher cost), while others will wait for the lower-priced rail service; their choice is influenced by their demographic market segment.

- Design a program of services and strategies for airport access. During this stage, it is essential to understand the quality attributes achieved by successful services so that modes can be matched with markets. The role for dedicated higher-cost services should be considered. With an analysis of travelers’ needs, a set of candidate modal services can be determined. This decision-making may be driven more by the overall public transportation strategy of the region rather than by airport access needs in isolation. When a region has already invested heavily in modes—such as rail and other regional connections—throughout the system, the extension of that system to cover the airport can be part of the regional transportation strategy. Depending on the situation of each individual airport, this stage might warrant planning studies, including the development and evaluation of technical and service options, as well as the selection of one or more preferred solutions. While this decision-making process should not ignore the future of transportation, it also should consider the availability and readiness of the modes and technologies associated with each option. For instance, legacy modes might be better suited to address short- and medium-term needs than solutions that rely on emerging technologies still under development.

- Design a communication program that informs passengers of the available modes. Consider developing programs for integrated passenger information and ticketing that provide basic service descriptions to users. A mobile app or website could be developed for passengers to have convenient access; this could include automated, itinerary trip-planning that encompasses all modes available to and from the airport, as well as the transportation modes traditionally used in the area, compared to the modes that mainly work around the airport.

Ground Access in Airport Master Planning and Aviation System Planning

Long-term airport development is guided through airport master plans. By assessing short-, medium-, and long-term needs; the solutions necessary to respond to them; and the cost of implementing these solutions, airport master plans can support cost-effective and efficient airport development while also considering potential environmental and socioeconomic impacts. These efforts will output a long-term plan for incremental and flexible development, with the resulting

projects integrated into the airport’s capital improvement plan. FAA’s AC 150/5070-6B Change 2: Airport Master Plans (Federal Aviation Administration 2015) provides guidance for preparing an airport master plan.

As emerging ground transportation modes are introduced in the coming years, airport master plans must consider these new landside users. Curbside congestion is a key issue for many medium and large airports; additionally, interactions between multiple modes of transport in the area can present safety concerns, which will be augmented by rising passenger and airport employee volumes. A potential solution to this curbside issue at large airports with different modes is a ground transportation center (GTC), a platform for all transportation modes to interact away from the airport curbside. GTCs promote multimodality and enhance connectivity during the passenger journey. For smaller airports, separate curbsides and associated pedestrian walkways can allow more modes to interact with each other with less of an increase in congestion.

The following list (a) identifies the airport access component of each element of an airport master plan and (b) outlines the implications of new airport access options and the introduction of emerging technologies for this process:

-

Preplanning: establishes the need for an airport master plan based on potential future shortcomings, conducts procurement and consultant selection, and determines the study’s scope and level of detail.

- – Airport access features: Scoping and goal setting of the preplanning phase should consider and address airport access, as well as the landside more generally.

-

Public involvement: development of a program that informs and involves stakeholders (air operators, airport tenants, community members, etc.) and allows them to contribute their opinions and concerns. Early involvement of stakeholders is crucial to consider public opinion before any major decisions are made.

- – Airport access features: Airport access can be an important item of conversation with communities if, for instance, the activity forecast or future plans significantly impact major roadways; mass transit systems potentially benefiting communities are being considered; or new technologies are being introduced, such as urban air mobility (UAM).

-

Environmental considerations: a clear understanding of the environmental requirements needed to move forward with each project in the recommended development program.

- – Airport access features: Environmental considerations should include requirements for the landside.

-

Existing conditions: an inventory of the existing facilities within the airport environment and its surroundings, including the airside, passenger terminal, and landside facilities, and identifies current challenges that could be addressed in the airport master plan. The regional setting of an airport and the land use patterns around it should be examined, and an environmental overview should be included.

- – Airport access features: This inventory also documents existing airport access solutions.

-

Aviation forecast: assesses the forecasted levels of aeronautical activity, namely passenger enplanements, cargo volumes, and aircraft operations. This item requires FAA approval.

- – Airport access features: The passenger activity forecast can inform further discussions on airport access requirements. UAM operations are not currently forecasted by the FAA as part of its terminal area forecast or aerospace forecasts.

-

Facility requirements: evaluates whether the airport’s functional elements can handle future demand—as determined in the aviation forecast—and identifies required additional facilities, if any. These requirements can also stem from new or updated regulatory requirements (i.e., FAA design standards and TSA and Federal Inspection Service security rules), aging infrastructure, and stakeholders’ strategic visions for the airport.

- – Airport access features: Incorporation of new access mode requirements based on projected increases in passenger traffic. For ground access modes that share the right-of-way with

-

- personal vehicles, these interactions would need to be considered when determining curbside requirements.

-

Alternatives for development and assessment: For functional elements that would require new or expanded infrastructure, multiple alternatives to meet facility requirements are proposed. After assessing each alternative with a wide range of evaluation criteria (including operational, environmental, and financial impacts), a preferred alternative for each element is selected and refined.

- – Airport access features: During this stage, airport sponsors and planners should develop alternatives to address the landside requirements, including new airport access options featured in the airport access strategy, as appropriate. Evaluation criteria for these alternatives can include compatibility with other existing and future facilities, environmental impact, financial feasibility, and how users can reach their final destination within the airport (i.e., intra-airport connectivity).

-

Airport Layout Plan (ALP): development of a set of drawings representing the long-term development plan for an airport. These drawings depict existing and future conditions for the airport’s facilities, nearby land use and property information, and the airspace associated with the airport. Requires FAA approval—issued as “conditional” until National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) approval is given.

- – Airport access features: Items associated with airport access technologies’ infrastructure must be depicted in the ALP drawing set, per FAA’s ARP SOP 2.00: Standard Procedure for FAA Review and Approval of Airport Layout Plans (ALPs) (Federal Aviation Administration 2013).

-

Facilities implementation plan: enumerates the construction projects required for implementing the preferred alternative and the necessary enabling projects for each functional element. Afterward, an implementation schedule for these projects is established, and construction costs are estimated.

- – Airport access features: The implementation timetable for ground access infrastructure shall be determined in a manner consistent with the network strategies and expansion plans of MPOs and transit operators (see Chapter 10).

-

Financial feasibility analysis: presents the financial plan for future airport developments and their funding, including eligible funding sources and project delivery methods.

- – Airport access features: Potential funding sources are reviewed in Chapter 10.

Metropolitan and Regional Transportation Planning Process

Transportation systems work as a consolidated effort of different stakeholders; when transferred to the airport environment, it is important to have a plan to communicate with all the parties involved. According to U.S. DOT, transportation planning is a cooperative, performance-driven effort that allows communities to coordinate future projects that help people and goods get where they are going. The transportation planning process typically follows these steps, as mentioned by the FTA as part of the planning essentials:

- Engage: engaging the public and stakeholders to establish shared goals and visions for the community.

- Monitor: monitoring existing conditions and comparing them against transportation performance goals.

- Forecast: forecasting future population and employment growth, including assessing projected land uses in the region and identifying major corridors of growth or redevelopment.

- Identify: identifying current and projected transportation needs by developing performance measures and targets.

- Analyze: analyzing various transportation improvement strategies and their related trade-offs using detailed planning studies.

- Develop plans and programs: developing long-range plans and short-range programs of alternative capital improvement, management, and operational strategies for moving people and goods.

- Estimate: estimating how recommended improvements to the transportation system will impact achievement of performance goals, as well as impacts on the economy and environmental quality, including air quality.

- Develop financial plan: developing a financial plan to secure sufficient revenues that cover the costs of implementing strategies and ensure ongoing maintenance and operation.

Sponsors of federally funded programs and projects are responsible for ensuring that their plans, programs, policies, services, and investments benefit everyone in their jurisdictions. TCRP Research Report 214: Equity Analysis in Regional Transportation Planning Processes, Volume 1: Guide (Twaddell and Zgoda 2020) provides a guide to analyzing and addressing equity in regional transportation planning.

Transportation Planning: How to Plan with Stakeholders

A large portion of most access trips are contained in the metropolitan area and use the same transportation facilities as intra-urban travelers. Furthermore, the same state, regional, and local planners who are responsible for urban transportation system planning are also responsible for providing good airport access, at least to the extent that airport travelers use urban streets, highways, and urban transportation systems. It is thus unlikely that major capital system investments will be justified, either economically or politically, unless the systems serve the intra-urban travel market in addition to airport access travel. Therefore, any planning for airport access systems should consider the relationship between airport access and other intra-urban trip making (Paules et al. 1971).

Emerging technologies at airports involve a wide range of stakeholders with different purposes and objectives. The potential stakeholders that will be involved with or affected by these technologies can be internal or external and may vary significantly from one technology to the other.

It is crucial for the stakeholders to be identified so they can work together to develop an inventory of existing conditions, which allows for transportation needs to be recognized. This is followed by an analysis and forecast of the future of transportation growth, strategies for future improvements, and the development of plans and programs that lead to the foundation of a cooperative transportation plan.

Engaging with the public and stakeholders is the first step of the transportation planning process and the first opportunity for participation of all relevant transportation agencies, including pertinent state and public transit operators. Similar to an interstate highway system, where different transit operators cooperate, the airport has an opportunity for this type of interaction with these emerging modes. ACRP Research Report 244: Advancing the Practice of State Aviation System Planning (Schnug et al. 2022) suggests that any ground access system identified in state aviation system planning should be coordinated with highway and transit planners and MPOs in addition to airport sponsors.

These emerging modes create opportunities for airports to contribute with many public transportation operators, as shown in Table 22. Common stakeholders for metropolitan and regional planning at the airport include public agencies as well as government-chartered authorities that deliver transit services to the general public (e.g., bus, airport, and other transit operators).

Table 22. Common Stakeholders for Metropolitan and Regional Planning at the Airport

| Stakeholder Group | Definition and Roles at the Airport | Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Airport operators | This category includes the internal stakeholders of the airport operator that are concerned with airport operations and management. | Airport operations; emergency management; engineering; maintenance, etc. |

| Vehicle manufacturers and repairers | This category includes the organizations that develop, manufacture, or repair specific modes and their parts or accessories. | Hyperloop Transportation Technologies (HyperloopTT) (U.S.); The Boring Company (U.S.); Leitner-Poma; Arup |

| Operators (mode-specific) | Mode-specific operators are responsible for transport services and overseeing these operations. | Transit authorities; private corporations/companies (Virgin Hyperloop, Arrivo, etc.) |

| Electric power industry and regulators | The electric power community includes the producers, providers, and suppliers of electricity, as well as the federal and state regulators and local energy commission. | Power generation companies; electricity suppliers and providers; utility commissions; U.S. DOE, etc. |

| Federal agencies or organizations | Federal agencies include organizations within the U.S. DOT that support state and local government in the design, construction, and maintenance of transportation infrastructure. | Federal Railroad Administration; FHWA; FTA |

| State transportation agencies | State transportation agencies are local entities that regulate and provide transportation systems for their communities. | State DOTs |

| Local and regional agencies or organizations | This category includes the local government concerned with the specific regulations of the area. | Regional transportation planning organizations; city governments; transportation agencies; and permitting authorities |

| Infrastructure | Infrastructure includes the specific facilities necessary for these technologies. | Utility companies; private companies (Leitner-Poma, etc.) |

| Finance | Developing the means to generate finance for these transportation modes. | Insurers; financers (private, local, state, federal) |

| Users and neighborhood associations | This category includes users of the mode and the neighborhood associations, which are part of the surrounding area and advocate for the well -being of the community. | Passengers; community; public |

The key programs of the transportation planning process, illustrated in Table 23, require agencies to deliver several plans and programs that are developed by a combination of efforts. As listed in The Transportation Planning Process Briefing Book, developed by FHWA’s Transportation Planning Capacity Building Program (2019), the key groups of documents that are typically part of the transportation planning process are

- Planning Work Programs, which include Unified Planning Work Programs prepared by MPOs and State Planning and Research Work Programs prepared by states;

- Long-Range Transportation Plans, which include Metropolitan Transportation Plans prepared by MPOs and Long-Range Statewide Transportation Plans prepared by states; and

- Transportation Involvement Plans, which include Transportation Improvement Programs prepared by MPOs and Statewide Transportation Improvement Programs prepared by states.

Table 23. Key Programs of the Transportation Planning Process

| Plan/Program | Who Develops? | Who Approves? | Time/Horizon | Contents | Update Requirements |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unified Planning Work Program | MPO | MPO/FHWA/FTA | 1–2 Years | Planning Studies and Tasks | At least once every 2 years |

| State Planning and Research Work Program | State DOT | FHWA | 1–2 Years | Planning Studies and Tasks | At least once every 2 years |

| Metropolitan Transportation Plan | MPO | MPO | 20 Years | Future Goals, Strategies and Projects | Every 5 years |

| Transportation Improvement Program | MPO | MPO | 4 Years | Transportation Investments | Every 4 years |

| Long-Range Statewide Transportation Plan | State DOT | State DOT | 20 Years | Future Goals, Strategies, and can include Projects | Not specified |

| Statewide Transportation Improvement Program | State DOT | FHWA/FTA | 4 Years | Transportation Investments | Every 4 years |

Source: FHWA/FTA (n.d.)