Enhancing Airport Access with Emerging Mobility (2025)

Chapter: 2 New Paradigm in Airport Access

CHAPTER 2

New Paradigm in Airport Access

Airport Access at the Threshold

Role of New Transportation Technologies

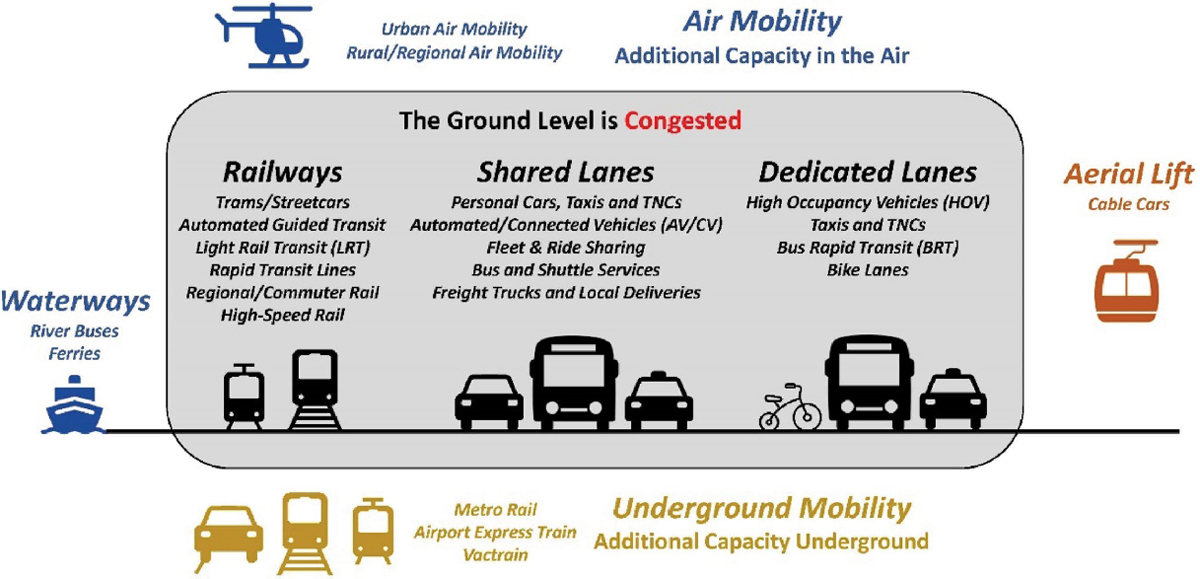

Airport access presents opportunities and challenges similar to those encountered by other forms of transit across the nation. There is a growing need to fix old problems and meet new expectations by using a customized blend of legacy and innovative solutions to provide a holistic response to local issues, as shown in Figure 4.

Roadway congestion in large metropolitan areas has been identified as a potential hinderance to future airport growth since the early 1970s. The development of the interstate highway system in the 1970s and 1980s improved travel times and provided temporary congestion relief for many areas. However, the sustained growth of many large metropolitan areas that developed around car-centric transportation patterns has created bottlenecks that can reduce airport attractivity.

Recently, various transportation innovations have emerged that could enhance airport access. For instance, connected and automated vehicle (CAV) technologies may alleviate curbside congestion at airports. They could also be used to bring new, on-demand service to underserved areas. Once these technologies mature, they might also enhance roadway safety (see Chapter 5). However, automated vehicles (AVs) will not solve traffic issues in large cities but rather they could worsen it and reduce transit ridership.

Leveraging Legacy Modes to Address Congestion

Other innovations are intended to solve urban congestion by bypassing roadways and going underground, in the air, or on water. Some of them, such as urban air mobility (UAM) and advanced water taxis, rely on small vehicles carrying two to six passengers to provide on-demand mobility. However, the typical passenger throughput of the 10 largest U.S. hub airports is over 50,000 daily passengers. This is comparable to the entire population of a small urban area, according to the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (n.d.). In 2019, the world’s busiest airport, Hartsfield–Jackson Atlanta International Airport (ATL), accommodated nearly 300,000 passengers—the approximate number of inhabitants of the City of Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania—each day.

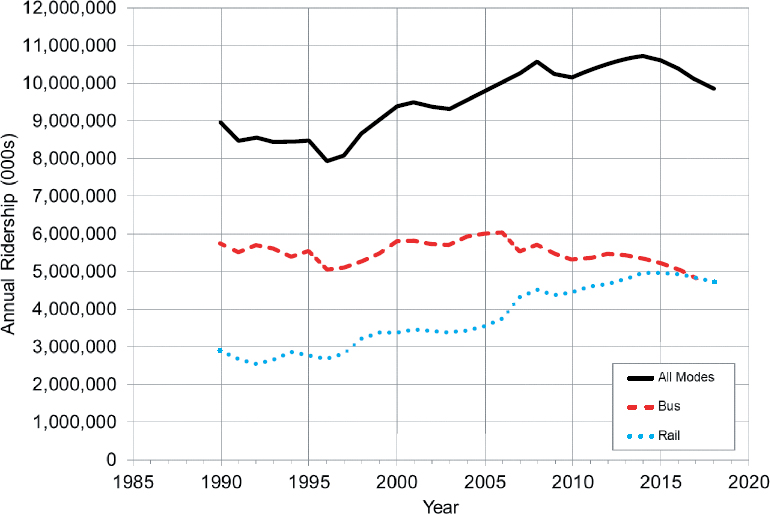

Figure 5 illustrates the change in annual ridership for bus, rail, and all modes of transportation in the United States since the 1990s.

While on-demand ridesharing can be used to transport some passengers and create new services, ridesharing alone will not be able to handle a significant portion of such passenger

Source: Le Bris et al. (2020)

Source: Watkins et al. (2020)

volumes without displacing the congestion elsewhere. Moreover, the actual cost of transit from the doorstep to the airport is the prime concern for many passengers and airport workers. Affordable mass transit should be considered as part of any commercial service airport’s access strategy that aims to tackle congestion. The immediate success of the Silver Line to Washington Dulles International Airport (IAD)—representing about 10 percent of passenger flows to and from the airport after a few weeks of operations—shows that mass transit can be a meaningful solution for areas suffering from acute congestion.

Consequently, innovation in transportation cannot be reduced to its technological components. Legacy modes, including buses, light rail transit (LRT), and cableways, combined with new technologies constitute a reservoir of untapped opportunities that can provide efficient and inclusive access to aviation facilities. Furthermore, innovation in airport access can be conceptual or organizational. Airports and their stakeholders can leverage nontraditional solutions to provide new access options, provide widespread access, and create revenue streams.

Mode Choice and Emerging Expectations

As part of transit demand analyses, mode choice studies can elucidate mobility decisions through a detailed review of key drivers that influence mode choice. There are many methodologies and tools for studying mode choice at individual airports or across aviation systems.

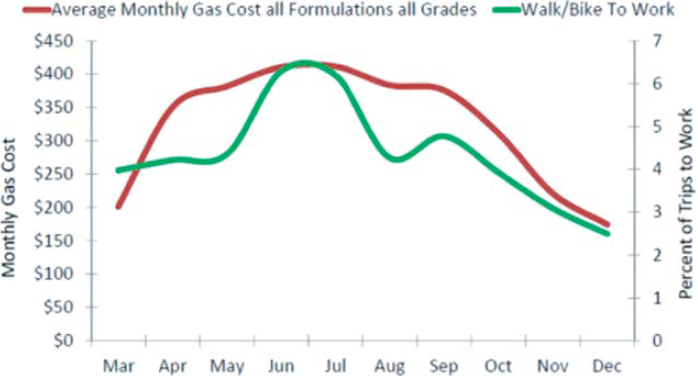

Typical mode choice drivers include the total cost of the trip—from the doorstep to the airport curbside—as well as total travel time and the level of service (LOS), including availability, comfort, safety, and amenities. For example, Figure 6 shows how rising gas prices affect the choice of mode by comparing walking or biking to work to average monthly gas cost in 2008. Commuting by foot or bicycle peaked during the summer months, when the average monthly cost of gas was at its highest for the year. As temperatures dropped with colder months, this percentage gradually diminished.

Accessibility is also a core preoccupation for a growing number of riders with reduced mobility and other disabilities. The Americans with Disabilities Act of 1990 features extensive provisions on transportation facilities and services. However, these requirements and their implementation in the field are not always sufficient to provide equal access to everyone.

Source: Adapted from FHWA (2014)

According to a 2021 survey by the Pew Research Center on U.S. adults, two-thirds of respondents say that climate should be the top priority to ensure a sustainable planet for future generations. Seventy-one percent say the United States should prioritize alternative energy development over expanding fossil fuel production (Funk 2021).

Intermodality in Airport Access

First and Last Miles

First and last miles (FLM) are the segments of the passenger journey that require travelers to find an additional mode of transportation—besides the plane—to reach the airport from their local origin or to arrive at their final destination from the airport. FLM is an essential aspect of the passenger journey—difficulties with FLM can impact the overall customer experience, prevent passengers from reaching the airport within acceptable travel time and cost, and adversely impact the LOS that the airport provides to its community. This can potentially lead to a loss of air service when passengers choose to use another airport, shift to another mode of transportation, or not use air travel.

To tackle FLM, some airlines have proposed alternative ground access services, both on scheduled and on-demand bases. In the United States, such programs have historically focused on first-class services. For instance, New York Airways was operating connections between the New York Pan Am Building in downtown Manhattan and John F. Kennedy International Airport’s (JFK’s) WorldPort. Passengers could check in at the Pan Am Building up to 40 minutes before their flight departure at JFK. A few years after the crash of a Sikorsky S-61L on the roof of the Pan Am Building, which precipitated the permanent closure of the heliport, a new Pan Am helicopter service was operated by Omniflight Helicopter Services with twin-engine Bell 222 and Westland WG-30 helicopters from the East 60th Street Heliport (dubbed “Pan Am Metroport”). The airline had various promotions, such as offering free helicopter connections for its international business travelers (Scott and Farris 1974). This service was terminated in 1988.

Intermodal Chain

The passenger journey involves a succession (or chain) of facilities, equipment, vehicles, and services that passengers will use from their origin to their final destination. Even the simplest journey, from the doorstep of someone’s home to the airport curbside via taxi or ridesharing, assumes there are street, curbside, and roadway facilities to the airport, as well as drop-off and pick-up agreements with transportation network companies (TNCs). When going to the airport with their personal cars, passengers typically park their vehicle at a parking facility, either at the airport or at a third-party, off-airport facility. At larger commercial service airports, automated people movers (APMs), moving walkways, or other modes might be used to go from remote landside facilities—such as a consolidated rental car (CONRAC) facility or ground transportation center (GTC)—to the passenger-terminal facility.

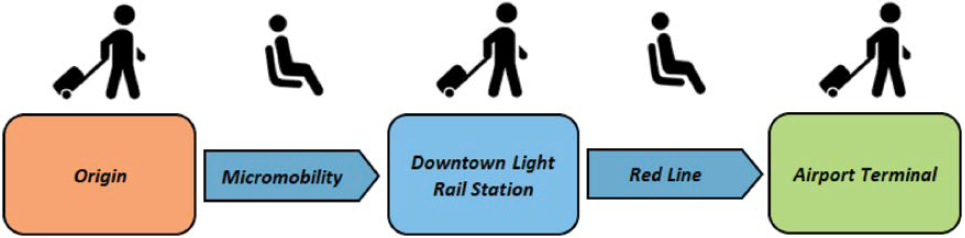

Mass transit options typically feature more steps. For instance, passengers can start their journey from home by using a micromobility service to access a nearby mass transit station and connect with their local LRT to the airport. In this scenario, passengers use services, equipment, and facilities provided by different stakeholders by

- Riding the micromobility service provider’s electric scooter (e-scooter) on bike lanes maintained by the local department of transportation (DOT);

- Connecting at the mass transit station to an LRT service, both of which are operated by a local transit authority or rail operator; or

- Accessing the passenger-terminal facility at the airport after going through an airport train station, potentially hosted with other modes within a GTC.

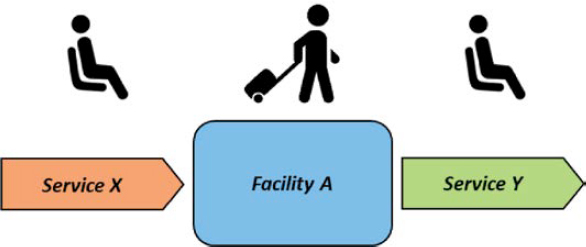

The intermodal chain described in this report adapts Rodrigue’s (2020) “Intermodal Transport Chain” concept of freight transport for passenger use. The intermodal chain is a step-by-step depiction of this transportation chain, created to provide a simple tool with common language for internal and external stakeholders. In this model, each fundamental element (also called “step” or “link”) of the chain is made of two transportation modes or mobility services connected by a facility (Figure 7).

This model can be used for a specific succession of mobility options: from origin to the airport terminal, from the terminal to the final destination, and from the curbside or GTC to the airline gates. The chain can be unidirectional (Figure 8) or bidirectional.

This intermodal chain can be used as the basis of various analyses as well as collaborative decision-making, supporting integrated facility planning, operations planning, and continuous improvement. For instance, Table 2 shows the potential for a spreadsheet-based tool to use the intermodal chain model to perform reviews as part of an integrated management system (IMS) across airport access stakeholders.

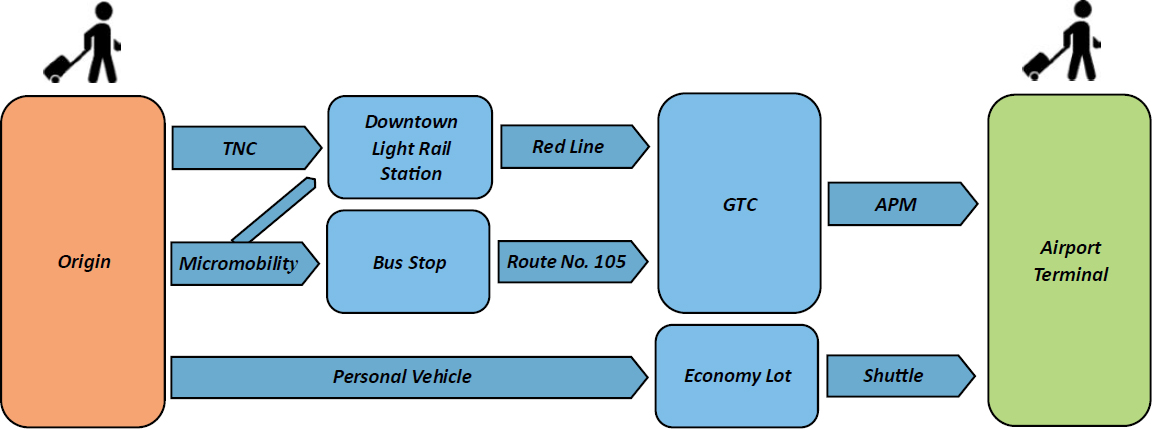

Multimodal Web

The intermodal chain may vary greatly from one trip to another depending on point of origin and destination, a passenger’s budget, and time constraints, among other variables. Some examples include:

- A passenger arriving at the airport for an early morning flight or leaving the airport after a late-night flight might use a taxi service or TNC app, as many mass transit systems do not have 24/7 operations.

Table 2. Example: Intermodal Chain Model for Performance Review

| Origin/Departure | Micromobility (Scooters) | Downtown Light Rail Station | Red Line | Airport Terminal | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Owner/Operator | 0 | Lime/Gotcha/Spin | Transit Authority | Transit Authority | Airport Operator |

| Avg. Transit Time | 0 | 7 min. | 5 min. | 26 min. | NA |

| Quality | 0 | NSTR | NSTR | NSTR | Difficulties reported with wayfinding from airport station to ticketing |

| Safety | 0 | E-scooters left at the middle of walkways in the vicinity of train station | E-scooter drop-off area to be defined with micromobility operators | NSTR | NSTR |

| Security | 0 | NSTR | NSTR | +25% increase in incidents reported between stations X and Y over past three months | NSTR |

| Sustainability | 0 | NSTR | NSTR | NSTR | NSTR |

Note: NA = not applicable; NSTR = nothing significant to report.

- A similar choice might be made by business travelers, who often have more stringent time requirements and travel expenses covered by their employers.

- Itineraries that are not as time-sensitive can be covered by a combination of transportation modes. For example, using heavy rail to leave the airport and head toward a bedroom community, then taking a bus, micromobility, or park-and-ride services to reach a residence. Depending on the range of modes available for use and the transit system’s complexity, numerous combinations may be possible to develop an intermodal trip—these combinations can be visually represented through a flowchart of the multimodal web (Figure 9).

While each passenger journey is unique, expanding the intermodal chain model into a multimodal web provides a tool to depict the different mode options and combinations of mobility available to and from the airport (Figure 9). This tool can be leveraged to deliver important data, such as conveying key findings from mode choice studies to decision-makers, which can help airports and metropolitan planning organizations (MPOs) size their transportation facilities accordingly.

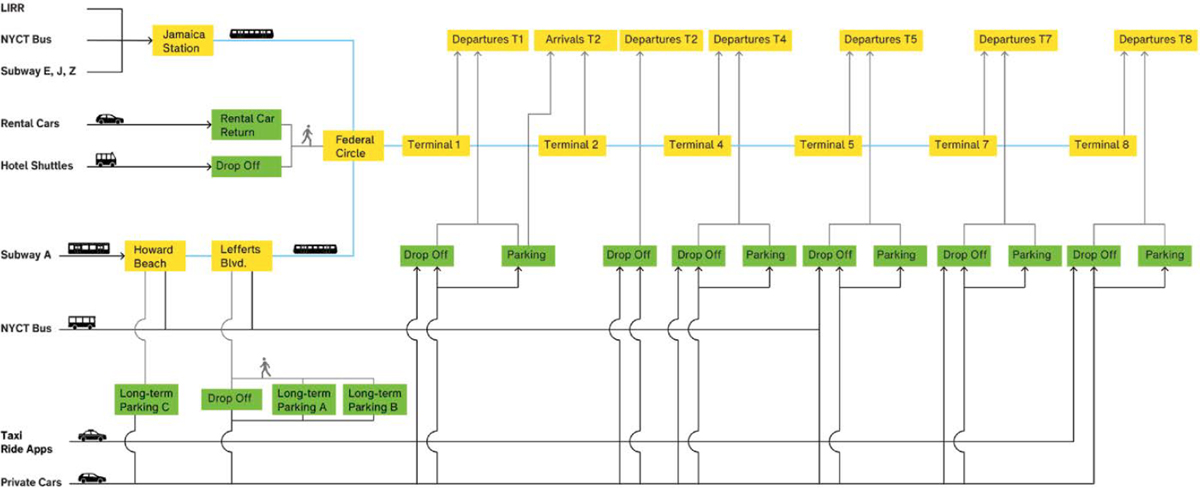

Similar tools can be developed to support the design process. For instance, the Port Authority of New York and New Jersey’s (PANYNJ’s) wayfinding manual (2020) specifies the “process diagram” as a programming tool that provides a high-level understanding of a general user’s needs along the steps of the transportation journey. This diagram is the first step of signage projects and the basis of subsequent plans (i.e., information diagram, flow plan, and sign plan), as depicted in Figure 10.

Integrated Approach of Intermodality

Fostering Intermodality

The passenger journey from the doorstep to the destination uses a succession of different modes, and the flight segment is just one part of this journey. To address these challenges, consider providing ground access for the trip from the origin to the gate and better access to transit for multiple modes and technologies, rather than focusing on one specific solution. Also, good integration of these modes should enable a relatively seamless integrated intermodal chain from the doorstep to the gate. For instance, mass transit systems serving the airport should provide large racks for bags, and bicycle compartments on trains can foster intermodality (i.e., the use of multiple types of transportation mode to reach a destination) with micromobility by encouraging passengers and airport employees to use bikes (Figure 11).

Airports as Intermodal Nodes and Multimodal Facilities

To achieve the integrated and inclusive vision of ground access presented throughout this chapter, specific provisions must be made at the airport to accommodate different ground transportation modes and services, as well as to provide an adequate LOS and satisfying user experience for all.

Various modes may serve an airport to accommodate FLM, daily commutes, and logistics. When several modes converge at the airport and interconnect, airports become intermodal nodes that users may leverage to access non-aviation mobility services (e.g., local community members going to the airport to ride mass transit or other travelers from farther locations going to the airport to take an intercity train).

Some airports have become fully multimodal by hosting different modes of transportation within their confines. In the future, more passengers might come to airports to connect between modes that do not include flights. Airports reaching this level of multimodality serve as a multimodal transportation facility, where non-aviation modes represent a significant activity and are accommodated with a similar LOS across “multiports” (i.e., facilities where different modes are completely integrated and interconnected). Different facility operators may coexist under the

Source: PANYNJ (2020)

Note: LIRR = Long Island Rail Road; NYCT = New York City Transit.

Source: Le Bris (2022)

same roof or operate out of contiguous transportation facilities within a multiport. A combined multiport facility is used by passengers of different transportation modes, with the option for passengers to connect with other services. Smaller aviation facilities may follow this trend as well, and the emergence of advanced air mobility (AAM) may lead some of them to become local mobility hubs.

Table 3 proposes six novel levels of multimodal maturity, from airports that are only accessible by car to fully integrated multiports.

Airports may want to address this diversification of modes and technologies, along with their emerging energy needs, in the context of new fuels and energy sources in ground transportation. According to Houalla and Le Bris (2022), airports need to develop new services and add value to communities by developing local, circular economy projects that leverage airports as intermodal nodes. They also need to work with communities, local governments, and transit agencies to rethink local transportation plans as mobility master plans. This vision cannot be implemented without questioning the status quo for metropolitan and regional transportation planning.

Barriers to Mode Integration

TRB Special Report 337: The Role of Transit, Shared Modes, and Public Policy in the New Mobility Landscape (2021) identifies several barriers to fully integrating transportation services in the United States. This analysis, performed in the broader context of transit and shared modes in the new mobility landscape, is relevant to airport access. The main barriers listed in the report are the following:

- Public agencies are unable to systematically gather data on the availability and real-time performance of all public and private shared-mode options.

Table 3. Levels of Multimodal Maturity

| Level | Definition | Examples |

|---|---|---|

| (1) Car-Accessible Only | Level 1 airports are only accessible by cars and on-demand ridesharing services. Other nonpublic transit services, such as hotel shuttles, may be offered. | GSP, LFT |

| (2) Public Transit Connected | Level 2 airports provide public transit through scheduled or on-demand services (mainly by bus). | RDU, SAT |

| (3) Mass Transit Connected | Level 3 airports are served by mass transit systems, such as BRT and light rail. | LAX, ORD |

| (4) Advanced Multimodal Access | Level 4 airports are served by more than three modes of transportation, including mass transit. They provide access to active transportation modes (e.g., micromobility) as well. | BWI, DCA, SEA |

| (5) Intermodal Node | Level 5 airports integrate multiple modes of transportation. Some passengers leverage this opportunity to access or connect with modes other than air transportation. These modes are interconnected, but the primary purpose is to provide air service. | AMS, ORY |

| (6) Multiport | Level 6 airports provide fully interconnected facilities for different modes of transportation. The airport serves as a multimodal transportation facility. Different facility operators may coexist under the same roof. The combined multiport facility is used by passengers of different transportation modes, and passengers have the option to connect with other services. | CDG, BER, FRA, MCO |

Note: AMS = Amsterdam Airport Schiphol; BER = Berlin Brandenburg Airport; BWI = Baltimore/Washington International Thurgood Marshall Airport; CDG = Paris Charles de Gaulle Airport; DCA = Ronald Reagan Washington National Airport; FRA = Frankfurt Airport; GSP = Greenville-Spartanburg International Airport; LAX = Los Angeles International Airport; LFT = Lafayette Regional Airport; MCO = Orlando International Airport; ORD = Chicago O’Hare International Airport; ORY = Paris-Orly Airport; RDU = Raleigh-Durham International Airport; SAT = San Antonio International Airport; SEA = Seattle-Tacoma International Airport.

- Because of fragmented governance, regions lack common goals and shared strategies to facilitate intermodal trips across jurisdictional borders.

- Local, regional, state, and federal laws and policies underprice road use when accounting for congestion and emissions, and they promote the use of personal cars over other modes.

- There is a lack of integrated transit fares, routes, and schedules across the multiple transit providers at the regional level, funding is often tied to local revenue sources, and service is often intended only for local taxpayers.

- Shared mobility offerings are rapidly evolving, with services regularly arriving, leaving, and changing as private providers seek profitable markets.

Intermodal Facilities

Potential Impacts of Mobility-as-a-Service

Mobility-as-a-service (MaaS)—digital apps and related technologies that enable users to plan, book, and pay for different offers and combinations of mobility services—is another emerging innovation that could significantly impact mode choice. MaaS promotes better integration of the various segments of the intermodal chain, and it could enhance interconnectivity, accessibility of alternative modes, and overall competition between transportation services. With

MaaS, both public and private mobility providers can offer transportation through unified digital portals that allow users to plan their journey, compare available offers based on customized criteria (e.g., time, cost, comfort, accessibility, waiting times, greenhouse gas [GHG] emissions, and number of mode changes), and pay for different offers with a single account at once.

End-to-end, integrated trip-planning can offer personalized information to users and more transparency on the real cost of mobility. Criteria for comparing trip options may include departure/arrival times, travel time, total cost, passenger experience, accessibility, climate impact, and customized items requested by users. MaaS might also remove some barriers to intermodality and remove transfers between different transportation services. The impact of MaaS on airport ground access could include improved user choice, increased efficiency and utilization of mass transit, decreased cost of trips for users, enhanced access to mobility, and promotion of greener travel options.

Under FTA’s 2016 “Mobility on-Demand Sandbox Program,” demonstrations were conducted in different parts of the country (e.g., “Adaptive Mobility with Reliability and Efficiency” in Palo Alto, California, and the Puget Sound First/Last Mile Partnership in Washington State). Since 2020, FTA’s Integrated Mobility Innovation program has been supporting more demonstration projects and effective implementation across the United States. Southern Nevada, Central Ohio, Tri-County Metropolitan District (Oregon), and other public transportation providers have developed integrated mobility apps with MaaS features. The rise of CAVs may enable a new era of personal on-demand mobility that could accelerate the implementation of MaaS platforms. UAM could leverage MaaS to compete with TNCs and combine its offerings with ground transportation services to integrate the FLM to and from vertiports into a single purchase (Mallela et al. 2023).

The impact of MaaS platforms on airports could be similar in aspect and amplitude to the advent of TNCs. MaaS could reshape how passengers and airport employees commute to the airport and change modal choice, especially where several options—including mass transit—are available. Furthermore, MaaS could increase the connectivity and accessibility of smaller airports. By combining offers from different public and private providers, MaaS can foster intermodal trips. Because of the potential implications of MaaS, local governments might elect to regulate this service or decide to provide MaaS in lieu of or along with the private sector. In 2017, Transport for Greater Manchester, United Kingdom, proposed six models to characterize the regulation of the MaaS market:

- Model A: Public sector is the MaaS operator and uses in-house resources.

- Model B: Public sector is the MaaS operator but outsources all of its responsibilities (i.e., external provision of services).

- Model C: Public sector is the MaaS operator but outsources all of its responsibilities, except financial transactions (i.e., operational commissioning).

- Model D: Public sector is the MaaS operator but brings in a partner to manage and operate the system (e.g., public-private partnerships [P3s]).

- Model E: Public sector is the MaaS operator but shares platform/resources with other providers to generate financial savings and efficiency (spin-out, mutual).

- Model F: Private sector is the MaaS operator and has full control of its operation.

To account for the policy and infrastructure program aspects of service-centric MaaS, U.S. DOT developed an operational program called Mobility on Demand (MOD). TRB Special Report 337 (2021) proposes the concept of “mobility management” and focuses on providing information to consumers that can help them make informed choices.

Ground Access for Urban Air Mobility

One of the expected early use cases for emerging UAM is to provide airport access from urban and suburban vertiports. However, there will likely be even broader applications for UAM in intra-urban mobility, and new vertiports are likely to emerge in metropolitan areas to accommodate this traffic. In addition, existing general aviation facilities and potential new STOLports (for short takeoff and landing [STOL] aircraft) could enable regional air mobility (RAM) offerings for intercity transportation (Mallela et al. 2023).

The demand for ground access at facilities served by AAM may exhibit characteristics shared by both commercial and general aviation airports. For instance, while the passenger activity at vertiports is expected to be significantly higher than at existing heliports, it should remain modest compared to most commercial service airports—especially in the early years of AAM implementation. Moreover, most UAM traffic will be on demand (i.e., unscheduled), with inbound flights only carrying a few passengers.

Availability of efficient ground access for the FLM will be crucial for the commercial success of UAM. If operators want to offer a competitive mobility proposition from door to door and deliver a service consistent with initial fares—likely higher than fares for mass transit and ridesharing services—passengers should be able to enjoy a seamless and time-efficient experience along the entire journey.

In other words, the connectivity of UAM services with other ground mobility services (Yedavalli and Cohen 2022) to provide for FLM will be key to UAM’s successful implementation. This connectivity can be facilitated by the availability of other modes at the vertiport or in its immediate vicinity, and the possibility to book an entire trip at once from the same app or self-service device. Connectivity also requires coordination and information sharing between the stakeholders of this intermodal chain to ensure transparency, flexibility, and resilience—a role that MaaS can fill.

Furthermore, while vertiports might create negative externalities by increasing acoustic and visual activity and by raising privacy and social equity concerns (Cohen et al. 2021), the AAM community has pledged to deliver equity and has worked on leveraging the emergence of this industry for this purpose (Le Bris et al. 2022; HYSKY Society 2022). Communities could benefit from the creation of local vertiports through projects that achieve these goals and include conversations on mobility enhancement in the area they serve. Some of these facilities could foster intermodal transit and serve as local community mobility hubs, accommodating bus stops, ridesharing curbs, micromobility stations, as well as amenities for users and shared public spaces.

Developing balanced networks of facilities will be crucial for the implementation of AAM. Siting vertiports must be both a demand-driven and equitable exercise, with vertiports that are serving communities and also strategically distributed across markets. A collaborative approach to vertiport development with considerations for ground transportation planning is in the interest of both commercial viability and public desirability of UAM. ACRP Research Report 243: Urban Air Mobility: An Airport Perspective (Mallela et al. 2023) proposes an integrated AAM planning process to include communities in planning efforts and address ground access and local mobility issues.

A similar pathway must be followed for RAM. One promise of AAM is to deliver equity improvements to rural and isolated communities through increased connectivity and access to larger mobility hubs. Therefore, RAM projects at general aviation airports (including new STOLports) in such areas should consider connections to existing rural and regional transit options (see Appendix B) or the creation of new on-demand ground transportation services to provide FLM rides. In the near future, CAVs could make on-demand rural transportation systems more cost-efficient and easier to implement (see Chapter 5).

Consolidated Rental Car Facilities and Ground Transportation Centers

A frequent near-curbside landside concern at legacy airports is congestion. With growing vehicular traffic and demand from landside tenants, available space in the immediate vicinity of the terminal area has become a rarity. Airports have addressed this issue by moving some of the ground access traffic away from the curbside with the creation of CONRAC facilities, GTCs, and remote curbsides connected to the main terminal area by intra-airport mobility systems (e.g., mobile walkways, people movers).

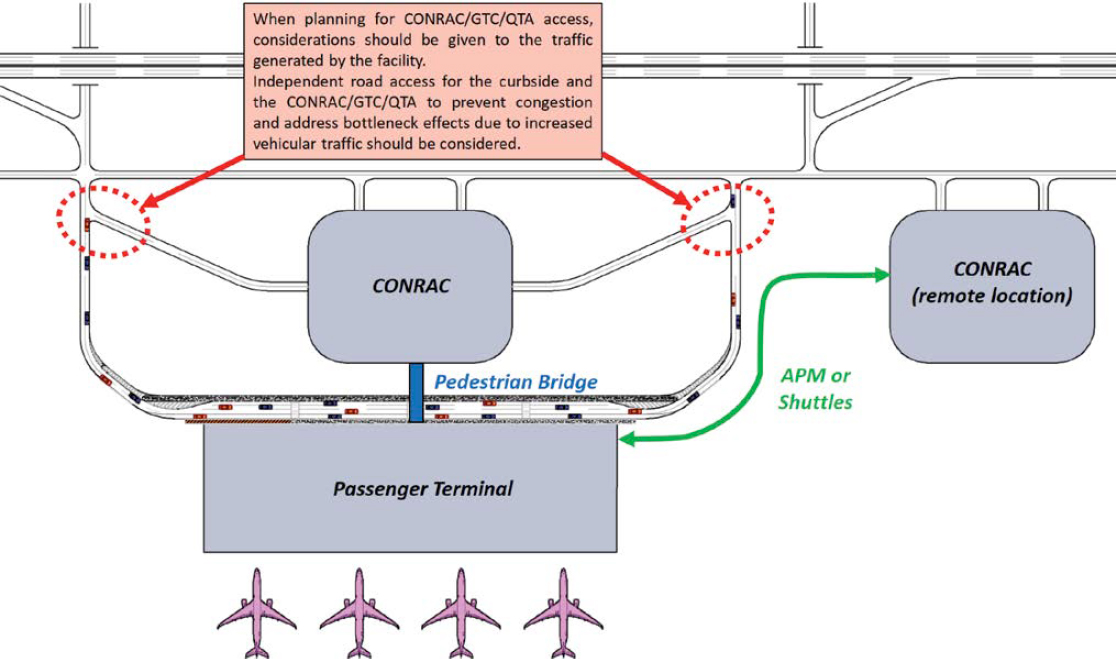

A CONRAC facility, sometimes abbreviated “CRCF,” has multiple rental car agencies in a single site, with large-scale operations designed to efficiently serve travelers and reduce roadway traffic congestion. Consolidating all rental car amenities in a unified location creates more opportunities for expansion on previously designated rental car premises. Instead of rental car agencies being located across the airport or off-site, CONRACs are a one-stop area where travelers can access all rental car companies. Some common features of these facilities include a dedicated parking lot or deck with electric chargers or other options for alternative fuels, shuttle service if the path to the terminal is a long walking distance, and quick turnaround areas (QTAs) for rental car companies to service and maintain their fleet. CONRACs may provide common amenities, such as restrooms and lounges. Initially established so far from terminal facilities that another mode was required to access them, CONRACs are increasingly located as close to the terminal as possible to prioritize customer convenience. Figure 12 depicts two location alternatives for a CONRAC facility: (1) across the terminal road, connected to the terminal by a pedestrian bridge, and (2) a remote location, necessitating the use of an APM or shuttles for passenger transfer.

Some advantages of this type of facility include:

- Improved parking: With a CONRAC, airports can maximize parking areas by placing rental car companies in a centralized location, which reduces rental car traffic from airport roadways. Rental car companies are usually consolidated in designated parking lots, and airports may integrate rental car parking with public parking or keep them in separate areas, depending on the property layout.

- Shorter wait times: Passengers have convenient access to the facility and reduced wait times. They can compare different rental car companies’ rates and availability at one location. If the facility is within a reasonable walking distance or accessible via an APM, CONRACs may eliminate the need for rental car transfer altogether.

- Reduced congestion of airport roadways: Vehicular access to the CONRAC facility can be implemented separately from the main terminal curbside, alleviating traffic from the main curbside roadway system. CONRACs also may reduce congestion by using separate shuttles for each rental car company, typically alleviated by an APM, or a single, unified shuttle with a higher LOS (i.e., more frequent service for individual passengers). The need for transfers is removed altogether if the CONRAC is within walking distance of the terminal.

- Opportunity for more commercial space: Moving all car rental facilities into one location creates valuable revenue space for other businesses that the airport might otherwise not be able to accommodate.

As part of its Landside Access Modernization Program, Los Angeles International Airport (LAX) is developing a remote CONRAC facility away from the airport curbside (Figure 13). Set to be commissioned in 2024, it will remove about 3,200 daily shuttle trips around the central terminal area (CTA) and will be served by an APM. This building will also accommodate ridesharing drop-off and pick-up, as well as a QTA facility for vehicle maintenance such as car washing, oil changes, and tire rotation. This QTA facility will help alleviate congestion by keeping operations within the footprint of the CONRAC/QTA.

A ground transportation center (GTC) is a combined facility that accommodates different modes of transportation (e.g., parking garage, TNCs, taxis, buses, and light rail) to improve passenger experience and address vehicular and spatial congestion. In cases of acute congestion in the terminal facility, GTCs can be leveraged to create remote curbsides, including for passenger pick-up. Typically, GTCs include modes of transportation that would benefit from being isolated or located away from the congested curbside.

For example, at Bradley International Airport (BDL) in Connecticut, the GTC is located adjacent to the airport’s main terminal and has five floors that include dedicated space for rental

Source: Los Angeles World Airports, 2022

cars, public parking, and bus access to direct service to downtown Hartford and links to regional rail. The rental car area includes a customer service space, a vehicle drop-off and pick-up zone, and a QTA. Because this GTC is located within walking distance of the main terminal, shuttle operations are not needed for passengers to go to and from the terminal.

Long Island MacArthur Airport (ISP) in New York recently inaugurated their new GTC, which includes rental cars, taxis, buses, ride-hailing services, hotel courtesy shuttles, and local bus services.

Finally, the rooftops of garages, CONRAC facilities, and GTCs are also potential candidates for future “landside vertiports” that enable UAM services with electric vertical takeoff and landing (eVTOL) aircraft (Mallela et al. 2023).

Additional Services to Passengers

Off-Airport Passenger Check-In and Processors

Downtown passenger services, where available, conveniently enable passengers to check in for their flights, drop off their bags, and request special services. Passenger bags can be picked up at their home or hotel and delivered to their final destination. In some countries, it is also possible to clear immigration and customs at downtown facilities. Different combinations of these services can be offered by airlines, third-party service providers and facility operators, and mass transit operators. Such services are provided at certain hotels in Las Vegas, Nevada, allowing passengers to check in for their flight and register checked bags that will transfer to their final destination.

Some dedicated airport train services (or airport rail links) offer passenger check-in and baggage drop-off services at their downtown central stations. Example rail links listed in Table 4 are all located outside of the United States in countries within Western Europe, Southeast Asia, or East Asia. Bags are typically transported by train or trucked separately and transferred into the inbound baggage-handling system at the airport. With the exception of the Swiss Federal Railways (SBB) service in Zurich, Switzerland, bags do not need to be rechecked by passengers at the airport.

In addition, as of this writing, there are cities outside the United States with downtown facilities of various complexities that provide passenger processing and transfer services off-airport:

- In the Al Zahiyah district of downtown Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates, a city terminal allows check-in and bag drop-off for a fee of about $12 for adults.

- The City Airport Terminal in downtown Seoul, South Korea, is a public facility that accommodates check-in services as well as immigration for departing passengers. It has the following features:

- – Part of the larger COEX complex, which includes a convention center and events venue.

- – Opened in 1990 and designated as an airport service facility by the Ministry of Construction and Transportation in 1993.

- – Operated by City Air Logistics & Transportation, South Korea.

- – City Airport Terminal services are also provided at two train stations: the Korean Train Express from Gwangmyeong station as well as the Airport Railroad Express from Seoul Station B2 City Airport Terminal.

Off-airport passenger processing was previously considered for Toronto Pearson International Airport (YYZ) and IAD. At IAD, a processor facility would have been built in the Foggy Bottom area. Passengers would have checked in and had their bags processed at the downtown facility. They would have been transported to their flight via buses from the city terminal. A slightly

Table 4. Airport Rail Links with Off-Airport Check-In Services

| Airport | Ground Access Service | Departing Passengers: Downtown Check-In | Arriving Passengers: Drop-Off at Airport Station | Immigration Clearance Available? | Mode/Technology |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hong Kong International Airport (HKG) | MTR | Yes | Yes | No | Train |

| Kuala Lumpur International Airport (KUL), Malaysia | KLIA Ekspres | Yes | Yes | No | Train |

| Incheon International Airport (ICN), Seoul, South Korea | City Airports | Yes | Yes | Yes | Bus |

| Vienna International Airport (VIE), Austria | City Airport Train | Yes | Yes | No | Train |

| Zurich Airport (ZRH), Switzerland | Select SBB stations | Bags are picked up by SBB at origin; passengers collect them at airport station and check them at the airport. | Check in bags at departure airport; bags will be delivered to passengers’ address. | No | Train |

different concept of city terminal was envisioned in the 1980s for the expansion of Mexico City’s Benito Juárez International Airport (MEX). One proposed alternative involved construction of a new runway system with remote satellites on the Texcoco Lake, northeast of the existing facility. The existing passenger terminal (current Terminal 1) would have been used as a processor for the new airport, with passengers and their bags being carried to the satellites by bus and then via APM.

Opportunities for Bag Transfer Services

Passengers with only carry-on bags will most likely check in from their portable electronic devices or from a kiosk at the airport. A 2022 survey of 1,700 U.S.-based travelers who used the travel organizing application TripIt showed that 41 percent of respondents avoid checking a bag. Ninety-three percent of respondents said they have changed their behavior when it comes to preparing for a trip in the context of disruptions experienced during the COVID-19 recovery period. Additionally, the now common practice of airlines charging for checked bags has increased the amount of carry-on baggage. Bag transfer services for a fee may also be relevant to this increase.

Many cruise lines, hotels, and resorts provide passengers with bag transfer or other bag delivery services that send baggage directly to their destination early in the journey. For instance,

many cruise lines in the Port of Miami, Florida, allow passengers to check in their luggage with their airline the night before disembarking. The luggage is sent directly to the airport and checked with the airline from the cruise cabin to the aircraft. Passengers taking advantage of this service see their bags again upon reaching their destination airport.

This service is also provided by some airlines, such as American Airlines or United Airlines, as well as some casinos in Las Vegas, for an additional fee. Passengers that choose to pay for this extra service can skip baggage claim and go straight to their desired location, and their bag will be sent to their address of choice no more than 6 hours after the flight lands. Furthermore, the American cruise line Royal Caribbean offers luggage delivery service for specific routes on journeys of 7 days or longer. This service transfers the guests’ bags from their rooms to the airport. This company only provides this service for U.S. destinations and select airlines (Royal Caribbean International 2019). Some hotels and resorts provide similar services, such as certain Disney vacation packages that send passengers custom bag tags from Disney or a specific travel agent, with bags delivered directly from the airport to the hotel (Walt Disney World 2018).

Transfers between Airports in Multi-airport System Areas

The need to transfer (landside) between airports in the United States is quite marginal and virtually nonexistent outside the largest airport systems. These transfers might nonetheless be required for passengers transitioning from airports that focus on domestic service to larger international airports—such as Ronald Reagan Washington National Airport (DCA) to IAD or Baltimore/Washington International Thurgood Marshall Airport (BWI) in the Washington, DC, area or LaGuardia Airport (LGA) to John F. Kennedy International Airport (JFK) or Newark Liberty International Airport (EWR) in the NYC area—or by passengers opting to self-connect by traveling on multiple tickets with different carriers. No major air carrier in the United States offers inter-airport transfer services; even within multi-airport systems, U.S. airlines tend to consolidate their operations at one airport and discourage inter-airport transfers by warning passengers during ticket purchase that the connecting flight departs from another airport. However, shuttle services between specific airports, such as shuttles that link IAD, DCA, and BWI or connect LGA and JFK, are available and operated by private companies. Table 5 shows examples of transfers between airports within a multi-airport system.

Table 5. Inter-airport Transfer Services Within Multi-airport Systems

| Ground Access Service Between Airports | Direct Transfer Service (Operator) | More Space for Bags | Sterile Bus/Train | Bag Transfer |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DCA-IAD | Heavy rail (WMATA) | No | No | No |

| LGA-JFK LGA-EWR | None | N/A | No | No |

| SFO-OAK | Heavy rail (BART) | No | No | No |

| CGH-GRU-VCP | Bus (Azul, EMTU, GOL) | N/A | No | No |

| CDG-ORY | Regional rail (RER B) | No | No | No |

| ICN-GMP | Bus (Korean Air) | N/A | No | No |

| Greater London airports | Bus (private operators) | N/A | No | No |

Note: BART = Bay Area Rapid Transit; CDG = Paris Charles de Gaulle Airport; GMP = Gimpo International Airport; GOL = Gol Linhas Aéreas Inteligentes; GRU = São Paulo/Guarulhos International Airport; ICN = Incheon International Airport; N/A = not available; OAK = San Francisco Bay Oakland International Airport; ORY = Paris-Orly Airport; SFO = San Francisco International Airport; WMATA = Washington Metropolitan Area Transit Authority.

However, some airlines in other countries do offer inter-airport transfer services:

- Air France used to operate bus lines between its two hubs of Paris Charles de Gaulle Airport (CDG) and Paris-Orly Airport (ORY) and to downtown Paris. This service was initiated in 1930, transferred to the airport operator Groupe ADP in 2016, and terminated in 2020.

- In Western Europe, a subsidiary of low-cost carrier easyJet, easyBus, operates several routes from towns to airports in the United Kingdom, with similar routes in other European countries.

- In São Paulo, Brazil, Azul Linhas Aéreas Brasileiras operates Azul Bus, which connects its hub of Viracopos-Campinas International Airport (VCP) with São Paulo/Congonhas Airport (CGH), the Barra Funda bus terminal in São Paulo, and the Shopping Tamboré in Barueri.

- Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, Gol Linhas Aéreas Inteligentes (GOL) operated a free shuttle service between CGH and São Paulo/Guarulhos International Airport (GRU). The service was available to its own passengers as well as customers of certain airlines (i.e., Air France-KLM and Delta). Buses had air conditioning, restrooms, live television, and free Wi-Fi.

Flights Operated with Buses and Codesharing with Train Operators

Some airlines have developed agreements with ground transportation service providers to reduce operating costs and still provide services along specific, shorter routes where passenger demand is too low to warrant regular air service. This requires all stakeholders to think beyond the traditional transport mode boundaries and gain some insights into the value of integrated air-bus services in regional transportation, where air services often represent “lifeline services” and significantly contribute to economic and social development in the region (Merkert and Beck 2020).

Instead of providing services between airports by plane, United Airlines, American Airlines, and other air carriers are providing this service by bus through a partnership with Landline, a bus company. When using these services, passengers board the bus from a conventional airport gate. United Airlines has implemented such service between Denver International Airport (DEN) and Northern Colorado Regional Airport (FNL), with a bus-operated “flight” marketed and sold by the airline. Passengers and bags are securely transferred from plane to bus at a gate at DEN (United Airlines n.d.). However, passengers from FNL to DEN must undergo security screening when arriving at DEN. United Airlines is considering expanding this alternative as a potential opportunity to solve capacity issues at one of their hubs, EWR, with a bus connection to and from Lehigh Valley International Airport (ABE).

American Airlines has deployed bus services between its hub at Philadelphia International Airport (PHL) to ABE and Atlantic City International Airport (ACY). Passengers and bags from ACY to PHL are screened at the departure airport, and passenger boarding and deplaning have both been conducted airside since the TSA (2023a) issued a short-term security program amendment to assess the security effectiveness of this program. PHL has a dedicated gate for these buses at Terminal F. The buses are considered sterile areas by the TSA, and to comply with this agreement, the security process includes sealing the windows and doors on the motor coach, as well as monitoring its journey from airport to airport through GPS. Thus, passengers only need to clear security screening once, at the origin airport (American Airlines n.d.). Figure 14 depicts one of these buses operated by Landline at PHL.

These bus services count as flights for ticketing purposes—with their own “flight” number—and can be added to flight tickets, providing passengers with the same protection and resources in case of delays, cancellations, or missed connections as other flight tickets. These agreements can provide airlines with access to new markets, while passengers can take advantage of these “flights” operated through other modes of transport as a reliable complement to their flight

itineraries through partner carriers. However, to date, these operations do not count as enplanements, and airport operators cannot collect the passenger facility charge (PFC).

In Europe, several air carriers have established similar partnerships with rail operators; as with the United-Landline and American-Landline agreements, these trips are marketed under a single ticket and offer delay/cancellation protections. Example partnerships are presented in Table 6.

Table 6. Examples of Air-Rail Partnerships in Europe

| Partnership | Contract Parties | Characteristics |

|---|---|---|

| Rail&Fly |

|

|

| AIRail (Germany) |

|

|

| Partnership | Contract Parties | Characteristics |

|---|---|---|

| AIRail (Austria) |

|

|

| City Airport Train (CAT) |

|

|

| Fly Rail Baggage Check-In |

|

|

| Train+Air |

|

|

Source: Babic et al. (2022)

Note: SNCF = Société Nationale des Chemins de fer français.