Enhancing Airport Access with Emerging Mobility (2025)

Chapter: 10 Implementation and Funding

CHAPTER 10

Implementation and Funding

Considerations and Challenges

As airport sponsors and consultants plan for the integration of emerging ground transportation systems at airports, infrastructure changes will be required to enable these modes to access the areas or facilities where they will operate. While prior chapters highlight the importance of future airport planning and forecasting, the successful integration of these modes highly depends on the ability of airport operators to overcome complex challenges at the time of implementation. Some of the key challenges to consider include

- Phasing and timing,

- Constructability (roadway and curb engineering, etc.),

- Infrastructure and capacity upgrades (power and grid requirements, utility planning, etc.),

- ADA compliance,

- Airport staffing and training requirements,

- Curbside management and enforcement,

- Coordinated integration between the various modes serving an airport,

- Guest experience implications,

- Safety (micromobility, traffic split between connected and automated vehicles [CAVs] and non-CAVs, vehicle-pedestrian interactions, etc.),

- Stakeholder coordination (internal and external),

- Technology standardization, and

- Community engagement (neighbors, increased traffic, additional construction or development, etc.).

This chapter analyzes some of these challenges across emerging modes of ground access while providing examples of recent case studies that highlight the mode-specific challenges encountered.

Infrastructure and Capacity Upgrades

Integrating emerging ground access technologies into airports during early stages of planning would require an overview of facility requirements that focuses on the infrastructure and capacity upgrades needed to accommodate these modes, as described in Chapter 8 of this report.

While electric charging infrastructure is a primary requirement in the electrification of many of these transportation modes, installation would primarily depend on the varying power demand for each of these modes, including advanced air mobility (AAM) aircraft, electric vehicles (EVs), electrified buses, and rail. Furthermore, the rise in electrification across a broader range of airport facilities (airside, terminal, and landside) could result in a strain on existing power grids and could require some airports to upgrade their overall power supply and connection to the power

grid. ACRP Research Report 236: Preparing Your Airport for Electric Aircraft and Hydrogen Technologies (Le Bris et al. 2022) provides guidelines for developing planning-level implementation scenarios that cover infrastructure upgrades. While focused on the charging needs for electric aircraft integration at airports, the report’s toolkit can also be used to estimate the potential impacts of integrating electrified landside transportation modes on the power supply requirements at airports.

Since each airport’s existing power supply, connection to the grid, distributed generation solutions, and power management are different, implementation challenges for system upgrades and additional power infrastructure to meet the high electrical loads will vary and would be determined by size and scale of operation, current power capabilities, and the density of the expected electric traffic. As a result, accommodating the load demand from the different types of transportation modes can range from upgrading or setting up new transformers, switches, transmission, and charging stations to more extensive projects warranting the building of new infrastructure that costs more, such as substations and microgrids.

Many airports cite electrical infrastructure capacity as a key barrier to meeting charging demand for EVs (passenger vehicles, transportation network companies [TNCs], taxi fleets, etc.) and accelerating airports’ EV adoption and infrastructure developments (Carreon et al. 2022). Therefore, continuous utility planning and engagement with utility companies for existing and anticipated power loads would help airports obtain the necessary capacity information to ensure that infrastructure upgrades are operationally and economically feasible. Furthermore, consider existing and future government mandates and policies that may accelerate the electrification of fleets servicing the airport. For instance, in 2021, the California Air Resources Board and the California Public Utilities Commission adopted the Clean Miles Standards, regulation that requires electrification of ride-hailing companies starting in 2023 and 90 percent of passenger-miles to be fully electric by the year 2030 (California Public Utilities Commission 2018).

A recent study by the Rocky Mountain Institute (Carreon et al. 2022) examined common implementation challenges for EV infrastructure development that were faced by 10 airports surveyed. Among those challenges is determining the accurate EV-charging demand and on-site capacity given the lack of standardized EV-demand measurement tools. Moreover, demand estimation for future electrification needs may have high uncertainty when assessing needs for different users or tenants, such as ride-hailing, or the estimates of other emerging electric modes’ operators and airport-owned fleets. Additionally, it is important for airport owners to consider building infrastructure capacity that can accommodate future use cases and demand at the airport to ensure that infrastructure built in place can accommodate long-term needs. Therefore, forecasting demand over the planning horizon and for a diverse group of users and tenants is critical when identifying utility upgrades required to accommodate future needs.

Connectivity and Communication Capabilities of Automated Vehicles

Automated vehicles (AVs) require and rely on automotive connectivity and communication capabilities defined by vehicle-to-everything (V2X) to establish safe operations on the roads. The two common types of automotive connectivity for V2X are vehicle-to-vehicle (V2V) and vehicle-to-infrastructure (V2I). V2I is particularly important when considering infrastructure upgrades and changes at airports to accommodate AVs.

V2I technology, mentioned earlier in Chapter 6 and Chapter 8, is a communication framework that allows connected vehicles to share information and exchange data with the surrounding infrastructure and devices—such as signage, cameras, and lane makers—to help coordinate driving

speed with traffic light regulations, maximize fuel economy, and prevent dangerous road situations (Airports Council International 2019).

As the functions of road signs and signals may be replaced with V2I communication and high-definition 3D mapping (Dennis et al. 2017), infrastructure still needs to accommodate non-CAVs, bicycles, and other users of airport access roads. Therefore, since safety is considered a prime objective during and after the integration of new emerging transportation modes at an airport, integration of V2I infrastructure with existing intelligent transportation system (ITS) equipment in the airport’s access areas needs to be phased in a manner that preserves safety and efficient operation for all users, including CAVs and non-CAVs.

Implementation and Constructability of Emerging Technologies Within an Airport Environment

Since airport sponsors want to ensure that the passenger and user experience will be preserved to the best extent possible during the implementation phase and early stages of operation, stakeholders need to consider several constructability and implementation challenges that may need to be mitigated to minimize temporary traffic-related impacts and inconveniences to the traveling public.

A seamless integration of ground access modes into the airport’s footprint is important to ensure a good passenger experience and efficient connectivity of the traveling public across modes. However, the restricted available footprint at some airports can lead to complicated phasing or hinder the ability to integrate ground access technologies into the airport’s main terminal access area.

Furthermore, integrating emerging ground access modes and technologies at airports requires significant planning and coordination efforts to bring a concept from its initial envision stage to successful implementation, all while causing minimal disruptions and interruptions to the daily operations of an airport. The latter is particularly challenging when working on brownfield sites or within a condensed airport footprint, requiring a phased implementation and constructability approach that does not significantly impact the guest experience.

The physical terrain on and near the airport’s footprint, as well as the limited footprint and land available for development for airports located in urban environments, may also add to the complexities of construction of new ground access modes at airports. As explained in Chapter 8, an average corridor width of heavy rail is between 25 and 33 feet, not including space for stations or potential widening at turns. During construction of tracks on exclusive rights-of-way not entirely located on airport property and at grade, there exist myriad constructability challenges to consider, including elimination of level crossings, acquisition of right-of-way, changes to geometric roadway configurations to satisfy certain turn-radii requirements, modernization of safety and traffic management systems, and maintaining minimum vertical and horizontal clearance. Furthermore, in the case of light rail transit (LRT) systems operating on semi-exclusive rights-of-way that allow vehicle traffic, pedestrians, and bicycle activity to mix with LRT at designated locations, implementation of infrastructure should consider each crossing’s physical specificities as well as the drivers’ and pedestrians’ commuting patterns to identify the traffic control systems and traffic management needed to prevent incursions and potential collisions.

In multi-airport regions—with average fares, airline air service offerings, and other factors being equal—providing new mobility options at an airport may change a passenger’s preference in selecting their airport of choice to depart from or arrive at. This is largely driven by the cost to access the airport and the door-to-door travel time. Therefore, airports need to consider how implementing infrastructure changes to accommodate emerging ground technologies may shape the passenger’s experience during and after the completion of construction.

Rarely, the integration of long-distance intercity rail links at airports is conceptualized in a greenfield context (i.e., the construction of an airport rail station and connection was planned when the airport was designed). In most cases, the rail line connection is integrated into the existing terminal complex and must address the decentralized patterns of separate airport landside terminals (Coogan et al. 2015). Physical integration of rail systems into the airport terminal buildings may require rerouting the main-line alignment into an airport, which can be very challenging and expensive to build. As an alternative, some concepts bring the rail as close as possible to the terminals and provide moving walkways from the station to the airport terminal building (e.g., Manchester Airport [MAN] in the United Kingdom).

Cases studies from major transit investments in Washington, DC, and San Francisco, California, demonstrate the importance of high-quality solutions designed for the transferring public-mode traveler. At the reconstructed Ronald Reagan Washington National Airport (DCA), the elevated Metrorail station is connected to the concourse level of Terminal 2 through two enclosed pedestrian bridges and is located closer to the terminal than the major parking garage facility is (MarketSense Consulting LLC et al. 2008). In San Francisco, passengers who are departing from the new International Terminal or accessing the airport through the Bay Area Rapid Transit (BART) train disembark from the train at the San Francisco International Airport (SFO) BART station, located on the same level as departures and the ticketing level of the International Terminal, without needing to go through any bridges, elevators, or escalators.

At some airports, a shared ground transportation center (GTC) can offer a solution to combine multiple shared modes for accessing the airport. When planning and constructing a GTC, designers need to account for the height clearance of vehicles and modes accessing the facility. For instance, some GTCs consist of both an outdoor surface lot to accommodate tall buses and an enclosed space integrated into the main parking garage.

Another significant feature to consider when implementing ground access at airports is the passenger experience for those who are carrying luggage. ACRP Report 61: Elimination or Reduction of Baggage Recheck for Arriving International Passengers (Wong et al. 2012) reported that air travelers with few or no checked bags are more likely to use rail service, while large family groups are less likely to use rail. Therefore, consider travelers’ characteristics and access to the airports when implementing new ground access solutions at airports that can improve the check-in and baggage drop-off experience of passengers. Furthermore, implementing off-site check-in services at transit stations or multimodal transportation hubs, provided by airlines, may contribute to a more seamless travel experience for passengers accessing the airport through a type of mass transit system (i.e., LRT, high-speed rail, personal rapid transit [PRT], or vactrain).

Curbside Management and Enforcement

Traffic management and monitoring is another challenge when it comes to implementing ground access solutions at airports. Airport operators must ensure that automated systems are in place to monitor ground access activity by mode and control access to restricted areas, while also controlling for dwell times for modes idling near the terminal curbside. Traffic access management is particularly important for airports implementing access fees. Moreover, airport operators can regulate shared micromobility operations at their facilities by establishing permit agreements with micromobility providers, similar to the agreements set out with TNCs (e.g., Uber and Lyft).

Airports have been able to monitor TNC activity on their property through the use of geofencing technology. This technology allows operators to track TNC drivers as they enter into, travel within, and exit from the boundaries of the airport, defined as the “geofence” boundaries, which are typically identified by the landside operations manager. Geofencing helps ensure that TNC drivers do not loiter within the boundaries of the geofence while waiting for a passenger

to request a ride. The geofence information collected by the operator should generally be available to the airport per the terms set in the operating agreement, available for audit at any time. Furthermore, Los Angeles World Airports (LAWA) uses Mobility Data Specification, a data standard that facilitates two-way communication between vehicle operators and the airport, to track ground operators on LAWA’s property; they could use this technology to communicate dynamic fees levied from those same operators for accessing the airport’s terminal area.

Stakeholder Coordination and Engagement

Similar to the implementation of large capital projects at airports, ground access projects require a high level of coordination, both internally and externally, from the early stages of planning. Early in the project planning stage, airport sponsors must identify the stakeholders that are likely to be involved or impacted by the project. Stakeholders may include

- Airport executives;

- Airport planning and engineering staff;

- Airport operations staff;

- Airport tenants and airlines;

- Transportation network operators (taxis, TNCs, EV operators, etc.), depending on the ground access technology being implemented;

- Government oversight agencies (FAA, FTA, local transit agencies, etc.);

- Political stakeholders (city council, mayors, etc.);

- Business community;

- Environmental agencies (U.S. EPA, state historic preservation offices, etc.);

- Airport users; and

- Neighboring communities.

Identifying and engaging the relevant stakeholders to gather their support early in the process helps navigate potential issues and challenges that may come up during the implementation stage and mitigate potential schedule delays. As sources and uses of funding must be identified and a funding plan must be established, obtaining stakeholders’ buy-in and support is critical to ensure that a project’s implementation is successful.

Furthermore, during one of the workshops held as part of this research, stakeholders engaged in the working group indicated the importance of coordinated integration, specifically at older facilities, to determine how electrified modes will interact with other modes and where these modes’ transfer points would be at older airports. For instance, Seattle-Tacoma International Airport (SEA) had to dedicate a level of their parking garage to be able to accommodate activity from TNCs. SEA representatives also highlighted their seven-step process, from idea inception to project completion, involving internal coordination among the airport’s different departments (planning, capital program, finance and budgeting, properties, procurement and engineering) to ensure a successful implementation process.

ACRP Research Report 216: Guidebook for Assessing Collaborative Planning Efforts Among Airport and Public Planning Agencies (Meyer et al. 2020) highlighted the importance of collaborative planning between airport sponsors and among different transportation and regional planning agencies on a periodic basis instead of a project-by-project basis. A case study from Hartsfield–Jackson Atlanta International Airport (ATL) indicated that airport staff have interacted with the Atlanta Regional Commission and local agency planning staff on a project-by-project basis. These projects include (1) the extension of the Metropolitan Atlanta Rapid Transit Authority (MARTA) rail line into the airport terminal, which included extensive collaboration between the airport and MARTA, as well as (2) the expansion of airport road capacity and connection to the interstate system, which involved extensive coordination between airport planners and the state department of transportation (DOT) throughout the design and construction of the project,

given the impact of this project on non-airport highways. The Atlanta case study highlights the challenges facing collaborative transportation planning, where airport staff may primarily view interaction with local and planning agencies as necessary on a project-by-project basis rather than engaging with these agencies on a periodical basis to foster an integrated, collaborative culture.

Metropolitan planning organizations (MPOs) prefer a more formal and active participation of airport staff in their planning activities to exchange information on upcoming projects and recent studies, given the important role that airports play in a region’s transportation system. Furthermore, collaboration between airport staff and MPO planners in identifying airport access issues when developing the region’s transportation plan and the airport master plan would be beneficial considering the emergence of new technologies, such as CAVs, that affect both types of studies (Meyer et al. 2020).

Economic Impact and Funding

Considerations for Capital Investment

Integration of new ground transportation modes at airports is considered a major capital investment that can enhance capacity, convenience, and access to the airport. In addition to constructability challenges, other challenges to implementation exist from a financial planning perspective. Moreover, advancing the planning and design of related infrastructure projects is necessary to obtain reliable cost estimates for construction and to determine funding and financing mechanisms to move forward with long-range development and capital investments (Coogan et al. 2015).

Significant investment will be required to deploy and grow electrification at airports, as well as deliver the charging infrastructure needed to support emerging vehicle technologies, which can be capital-intensive. They may require thorough investment planning and return on investment (ROI) studies to determine the potential economic implications while considering potential disruption in mobility trends over the lifespan of the project. For instance, as airports move from a master plan into advanced planning and continue into designing a new parking garage, stakeholders need to reassess parking requirements and capacity needs in light of future mobility trends, changes in access modes, and growth in mobility-as-a-service (MaaS) usage (Streeing et al. 2018).

The cost to provide infrastructure to accommodate emerging ground access technologies at airports could be considerable. As a developing industry necessitating significant investment in physical infrastructure and business operations, airports could leverage state, federal, and local grant programs as well as loan programs in place that can mitigate part of the development cost. Furthermore, since utility upgrades make up a major portion of capital expenditure costs when it comes to integrating ground access modes—such as EVs—at airports, costs can be minimized through strategically siting large EV-charging hubs, investing in load management, and engaging utility companies early in the planning process to determine potential cost share. Moreover, utility electric service upgrades constitute a significant share of the overall project cost, including line extension and transformers, and they represent a one-time capital expenditure with decades of service life.

Funding and Financing Sources

While airport funds and reserves consisting of airport-generated revenues from parking, terminal concessions, leases, rental car revenues, and other sources can be used by airports to fund ground transportation–related improvements, these funds can also be used to leverage investments by using airport revenue bonds payable from airport-generated revenues pledged

to pay back debt service. This chapter provides an overview of available funding and financing sources beyond airport reserves and airport revenue bonds, which may be restricted in availability or capacity at some airports.

Several agencies, including the FAA and FHWA, provide federal funding programs in support of transportation projects at the state and local levels, which can be applicable to ground access projects at airports. Each program—such as the Airport Improvement Program (AIP) and the Surface Transportation Block Grant (STBG) Program—establishes well-defined criteria for eligible applicants and projects.

Airport Improvement Program

Traditional funding programs, such as AIP, exist to help cover the costs of implementing capital projects at airports. AIP provides grants to public agencies and, in some cases, to private entities for the planning and development of public-use airports that are included in the National Plan of Integrated Airport Systems. Surface transportation and ground transportation projects are eligible for funding under AIP, subject to certain conditions and restrictions.

Most ground access projects follow the eligibility requirements of access roads per the FAA’s (2019) AIP handbook. For instance, bike lanes are allowable as part of access road development subject to access road requirements. Furthermore, access rail projects are treated similarly to access roads when it comes to AIP funding eligibility; therefore, they are considered terminal development. As such, a surface transportation project must meet the following conditions:

- The road or facility may only extend to the nearest public highway or facility of sufficient capacity to accommodate airport traffic.

- The access road or facility must be located on the airport or within a right-of-way acquired by the sponsor (i.e., showing on the Airport Layout Plan).

- The access road or facility must exclusively serve airport traffic (i.e., limited to only serving passengers and employees traveling to and from the airport, with the facility experiencing no more than incidental use by non-airport users).

Under AIP, there are several programs to promote clear air and airport emissions reduction initiatives. Airport sponsors can fund projects as part of these programs using AIP grants, including both entitlement and discretionary AIP funds. A summary of these programs is provided as follows:

- In 2004, the FAA founded Voluntary Airport Low Emissions (VALE), a program to assist airports located in designated ozone and carbon monoxide (CO) air quality nonattainment and maintenance areas. Through VALE, airport sponsors can use AIP funds to fund projects that improve the air quality of airports. Since its inception, VALE grants have funded projects such as electric shuttle buses, gate electrification power and air units, electrical ground support vehicles, ground service charging equipment, and solar panels.

- Another key program that allows the use of AIP funds is the Zero Emissions Vehicle and Infrastructure Program, established in 2012. This program enables airport sponsors to purchase airport-owned, on-road zero-emissions vehicles (ZEVs), limited to those with all-electric or hydrogen-powered drivetrains, with the most commonly funded vehicle type being vehicles that transport airport passengers and employees. Eligible projects also include constructing infrastructure needed to use and operate ZEVs, including refueling stations, rechargers, on-site fuel storage tanks, and other equipment required for station operations.

Passenger Facility Charges

Another source of funding that can be used for airport ground access projects are passenger facility charges (PFCs). These funds represent airport-imposed fees on eligible enplaning passengers, capped at $4.50 per flight segment at commercial airports, and they can be used toward

the nonfederal share of project costs under an AIP grant. PFCs can be used by airports to fund FAA-approved projects that increase safety, security, capacity, or air carrier competition at an airport or reduce noise. More specifically, PFCs can be used to fund ground access projects at airports, such as guided modes and connections on the airport, that meet the objective of preservation or enhancement of capacity of the national air transportation system or benefit competition among airlines. That is, ground access projects can provide a more reliable and faster access time to an airport, resulting in a reduced total trip time, and can result in a passenger choosing between air carriers operating at different nearby airports. The FAA also recommends that agencies coordinate early in the planning process with both the FAA and FTA for rail access–related projects to establish justification for a PFC-funded project.

In 2004, the FAA published a policy on the eligibility of ground access projects for PFC funding that involved the FAA determining the eligibility of these projects on a case-by-case basis after a review of the particulars associated with each unique project, regardless of the technology proposed (e.g., road, heavy or light rail, water). Furthermore, the policy restates that the conditions for eligibility for rail and fixed-guideway systems would mimic the eligibility for access roads under AIP. The policy also states that while the public agency must retain ownership of the completed ground access transportation project, the sponsor may choose to operate the facility on its own or to lease the facility to a local or regional transit agency for operation within a larger local or regional transit system (Federal Aviation Administration 2004).

In 2021, the FAA Office of Airport Planning and Programming published a memorandum providing updated guidance (Federal Aviation Administration 2021b) on the use of PFCs for eligible on-airport rail access, amending the 2004 FAA policy to expand eligibility of rail lines that do not exclusively serve an airport eligible for PFC and providing methodologies to calculate PFC-eligible costs. Under the 2004 policy, if a road or facility is intended to serve and be used by both airport and non-airport users, only the physical segments that exclusively serve airport users and terminate at the terminal could be funded with AIP or PFC funds. That is, if a railway is a through line where the on-airport station is not the terminus, then it was not eligible since it does not meet the exclusive use criteria. An example includes the 5.5-mile LRT extension to the existing Red Line in Portland, Oregon, connecting Downtown Portland to Portland International Airport (PDX) via a station at the airport. The project was built through a unique public-private partnership, and the Port was able to fund its $28.3 million portion for the on-airport segment through its PFC funds.

The PFC memorandum amends FAA’s (2001) PFC order, which stated that airport ground access projects, similar to road access projects, must be for the exclusive use of airport patrons and employees. The memorandum, “Information: PFC Update, PFC 75-21,” states that a portion of rail access projects may be eligible even if the rail project does not exclusively serve airport traffic, which helps to provide more transit options to travelers and promotes intermodal connections. The proposed methodology uses a prorated ridership approach in which the eligible cost is based on the forecast ratio of airport-to-non-airport ridership. After this policy was introduced, air carriers’ representatives commenting on this policy voiced their concerns that a sponsor’s grant assurances prevent revenue from being used for non-aviation purposes and that the expanded eligibility for through-airport rail access would shift user fees collected from being used for on-airport systems to non-airport-related infrastructure. However, FAA restated that airports must ensure their airside needs (runways, taxiways, aircraft gates, etc.) are met before imposing a PFC collection above $3.00 for use on terminal and landside projects. Furthermore, rail access projects must be justified per the criteria established previously (e.g., reducing traffic congestion) to make an airport more attractive to airline passengers.

While the recent PFC update applies to the use of PFCs for on-airport rail access projects, all other ground access projects’ eligibility continues to follow the 2004 Notice of Policy regarding the Eligibility of Airport Ground Access Transportation Projects for Funding Under the Passenger

Facility Charge Program (Federal Aviation Administration 2004). Furthermore, the PFC update differentiates rail line eligibility from AIP funds that continue to follow the AIP eligibility policy on ground access, summarized previously. Rail stations located on-airport remain fully eligible for PFC funding.

Bipartisan Infrastructure Law

The recent passage of both the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law (BIL) and the Inflation Reduction Act has created an unprecedented opportunity to invest in U.S. infrastructure and energy security. Under the BIL, airport infrastructure grants consisting of $15 billion will remain available until September 30, 2030, with $3 billion made available each fiscal year from 2022 through 2026 for airport-related projects as defined under the existing Airport Improvement Grant and Passenger Facility Charge criteria. The funds can be invested in runways, taxiways, and safety and sustainability projects, as well as terminal, airport-transit connections, and roadway projects. The federal share of the costs covered by this grant mirrors the match requirements set for the AIP and is the percent for which a project for airport development is eligible under Section 47109 of U.S. Code (U.S.C.) Title 49.

The BIL also provides a unique opportunity for airport sponsors to fund ground access projects at airports through the new Airport Terminal Program. This program consists of $5 billion, available until September 30, 2030, to provide competitive grants for airport terminal development projects that address aging infrastructure at U.S. airports. Discretionary funds of $1 billion will be made available each fiscal year from 2022 through 2026, with additional consideration given to airport size for the allocation of funds. Projects eligible under this program mirror PFC eligibility and include access roads exclusively servicing airport traffic that lead directly to or from an airport passenger-terminal building, as well as on-airport rail access projects as identified in PFC Update 75-21. Among grants awarded to terminal development projects, priority is given to projects that increase capacity and passenger access and improve airport access for historically disadvantaged populations. The federal share of costs of projects carried out from funds made available under this program is 80 percent for large- and medium-hub airports and 95 percent for small-hub, non-hub, and non-primary airports. In 2023, Louis Armstrong New Orleans International Airport (MSY) was awarded an $8 million Airport Terminal Program grant to fund a portion of the site preparation work and construction of a road between the north terminal and south campus parking and rental car facilities. This new road will also connect the terminal to a stop for a planned Amtrak rail line to Baton Rouge. Part of a larger state DOT multimodal community/airport project, the road will allow passengers on the proposed rail line to connect to the terminal.

Surface Transportation Grants

Surface transportation grants include programs that provide a nexus to surface transportation at airports and could potentially fund large ground access infrastructure projects. Some of those programs include the Rebuilding America program and the Rebuilding American Infrastructure with Sustainability and Equity (RAISE) program, one of several avenues of funding for projects in the BIL. In 2022, eligible projects under the RAISE program were expanded to include the surface transportation components of an airport project eligible for assistance under Part B of subtitle VII, which will have significant local or regional impacts. Grants under this program are awarded on a competitive basis, and each grant may not exceed $25 million, with additional limitations imposed on grants in urbanized areas (i.e., not less than $5 million) and rural areas (i.e., not less than $1 million).

In 2022, the City of Pullman in Washington State was awarded a $1.05 million planning grant to complete the planning for the reconstruction of 2.1 miles of airport road for multimodal and regional access improvements, including a shared-use bike path. This project will enable the separation of motorized and non-motorized activities and provide a bus stop that connects the

airport to the regional bus system (U.S. Department of Transportation 2022c). In 2011, under the Transportation Investment Generating Economic Recovery Grant Program (predecessor to RAISE), the Dallas Area Rapid Transit (DART) authority received a $5 million grant for the DART Orange Line extension to extend light rail service 5.17 miles from the Belt Line station to the Dallas Fort Worth International Airport station between Terminals A and B.

The STBG Program provides flexible funding apportioned to states that may be used by states and localities for projects to preserve and improve the conditions and performance on any federal-aid highway, bridge and tunnel projects on any public road, pedestrian and bicycle infrastructure, or transit capital projects, including intercity bus terminals. The passage of the BIL expanded eligible activities under this program to include planning and construction of projects that facilitate intermodal connections between emerging transportation technologies, such as magnetic levitation (maglev) and hyperloop, installation and deployment of current and emerging intelligent transportation technologies, and capital projects for the construction of a bus rapid transit (BRT) corridor or dedicated bus lanes.

Transportation Infrastructure Finance and Innovation Act

The Transportation Infrastructure Finance and Innovation Act (TIFIA) program provides subsidized loans designed to fill market gaps and leverage substantial private co-investment by providing supplemental and subordinate capital to public entities and private firms. It is a key federal financing program that supports the nation’s largest and most complex transportation infrastructure projects by offering long-term, flexible, and low-cost financing. The program offers three distinct types of low-interest-rate financial assistance: (1) secured loans, (2) loan guarantee, and (3) line of credit. The BIL adds to the scope of eligible projects under the TIFIA program by including airport-related and PFC-eligible projects as defined in Section 40117(a) of U.S.C. Title 49. As a result, airports are eligible for TIFIA funds, providing them with highly attractive subordinated debt financing that can lower the total cost of projects. However, funding from TIFIA loans can only cover up to 33 percent of eligible project costs.

Examples of ground access projects previously financed through TIFIA include the construction of the Miami Intermodal Center, adjacent to Miami International Airport (MIA). The original TIFIA commitment amounted up to $539 million, to be repaid from fuel tax revenues and fees levied on rental car users (Federal Highway Administration 2010). Interlink, formerly referred to as the Warwick Intermodal Station project, provides another example of an intermodal project at Rhode Island T. F. Green Airport (PVD) in Warwick, Rhode Island, that was funded partly with a $42 million TIFIA loan. This loan was secured by customer facility charges imposed by the Rhode Island Airport Corporation and payments by rental car companies for tenant improvements in the intermodal facility. The project consisted of an intermodal facility that connects air, rail, buses, automobiles, and rental cars at the airport and serves Massachusetts Bay Transportation Authority (MBTA) commuter trains traveling on a rail platform that is integrated within a consolidated rental car (CONRAC) facility (Federal Highway Administration 2010).

Section 5309 Capital Investment Grants

The Fixing America’s Surface Transportation Act authorized $2.3 billion per year until fiscal year 2020 for the FTA Capital Investment Grants (CIG) program. The BIL authorized $3 billion per year through fiscal year 2026. The CIG program divides the funding available into separate programs:

- Small Starts provides funding up to $150 million for projects with a total estimated cost of $400 million or less.

- New Starts provides funding over $150 million and up to 50 percent of the total project cost for projects with a total estimated cost above $400 million.

Both Small Starts and New Starts have unique sets of procedures, FTA-approval steps, and project evaluation criteria. Challenges and issues to pursuing Section 5309 CIGs include the following:

- CIG funds are discretionary, with no guarantee that the funds will be awarded. Pursuing and completing pre-grant steps and grant proposal would be carried out “at-risk.”

- Any project with an application for either Small Starts or New Starts funding would need to receive at least a “medium” rating on FTA’s project justification and local financial commitment criteria. Justification criteria include mobility improvements, environmental benefits, congestion relief, land use, economic development, and cost-effectiveness.

Title 23 Flexible Funding

Federal laws 23 U.S.C. § 104(f) and 49 U.S.C. § 5334(i)(1) allow the FTA to have funds for administration transferred to public transportation projects from the Federal-Aid Highway Program. This provides additional flexibility in funding sources that are available through federal means. Examples of programs eligible for flexible funding, per the FTA (2022) website, include

- Congestion Mitigation and Air Quality (CMAQ) Improvement Program: flexible funding for local or state governments to support transportation projects and programs that meet Clean Air Act standards and requirements.

- STBG Program: provides flexible funding to best address state and local transportation needs.

- Tribal Transportation Program: provides flexible funding to support safe and reliable transportation and public road access to and within Indian reservations, Indian lands, and Alaska Native Village communities.

- Flexible Funding for Transit Access: a joint effort between FHWA and FTA to promote safer routes to transit and help local policymakers better connect their communities through Complete Streets.

Public-Private Partnership

Engaging private-sector funding and utilizing public-private partnerships (P3s) can offer numerous benefits by sharing the costs and risks and supplementing the capital investment needed to plan for the implementation of ground access technologies and modes at airports. While private participation is common at European airports, starting with the British Airport Authority being sold in 1987 in a $2.5 billion public offering, full privatization of commercial U.S. airport operations has not taken hold. Instead, privatization in the U.S. aviation sector is better explained through the context of asset monetization through long-term P3s rather than full privatization and sale of assets.

Through a P3 delivery, a private entity may provide financing with the expectation of being repaid over time through revenue generated from the project or availability payments from the airport. The private operator may also be providing design and construction of the project or operating the facility being developed under a long-term lease (Wolinetz et al. 2021). When evaluating a project for suitability for P3 project delivery and access to private funding, the airport owner must evaluate the overall project’s financial plan and how private funding may help achieve the agency’s goals in transferring revenue risk or retaining debt capacity or funding for other planned capital projects. Furthermore, private capital is most likely more expensive than capital funds accessed through public sources, such as General Airport Revenue Bonds. As such, it is important for airports to consider the costs and benefits of private funding and financing mechanisms by conducting financial feasibility analyses that can help determine whether private funding through a P3 delivery is appropriate (Wolinetz et al. 2021).

In addition, projects that may have significant challenges to implementation during phasing and construction could benefit from specialized expertise and innovative design ideas brought by P3s—while sharing risks and financial responsibility, the private entity is incentivized to

ensure the design and construction can provide substantial cost savings and a potential increase in revenues, depending on the infrastructure being developed. An example ground access project delivered through a P3 is the $5.5 billion Landside Access Modernization Program at Los Angeles International Airport (LAX), consisting of an automated people mover (APM) with 2.25 miles of elevated guideway and six stations that would also connect the LAX central terminal area (CTA) with the regional transportation system (light rail and Metro bus) via the future Airport Metro Connector station being built by LA Metro (Figure 81). The program, scheduled to open in 2024 under a $4.9 billion contract, was the first P3 contract awarded at LAX for a 30-year lease for the selected joint venture to design, build, finance, operate, and maintain the project.

Heathrow Express, a nonsubsidized private rail company, provides an example of a £450 million ground access mode financed and operated entirely from the private sector, consisting of a high-speed rail-air link operating between Heathrow Airport (LHR) and central London and two dedicated stations at LHR. Since its service initiation in 1998, Heathrow Express captured market share over the taxi service and the London Underground to the airport from central London.

Airports and public agencies can incorporate social and environmental value into P3s. This can start with the development of the agreement between parties, including price negotiation under the concession model. Jin and Liu (2022) talk about the importance of evaluating the social benefits of a project (to assess its social and environmental value) in addition to its financial performance in order to include social benefits in the concession price negotiation. This process helps improve payoffs for the government and corporate social responsibility–oriented concessionaires. However, the process requires metrics to quantify social benefits. For instance, the social ROI is a framework to measure and account for the value created by a project or program in terms of social, health, environmental, and economic costs and benefits (Nicholls et al. 2009).

Social benefits can also be incorporated through outcomes-based contracting. Social impact bonds (SIBs), also known as pay-for-success bonds, are a non-tradeable version of social policy bonds. Unlike traditional bonds, SIBs do not offer a fixed rate of return; repayment to investors is contingent upon the achievement of specified social outcomes. In other words, SIBs can be considered a form of P3 funding of social benefits through a performance-based contract.

Airport access projects focused on sustainable initiatives or developing mobility solutions that benefit underserved communities could also seek financial support from private investors through impact-driven funding programs. Impact investing is defined by the Global Impact Investing Network as investments made into companies, organizations, or funds with the intention of generating a measurable and beneficial social or environmental impact alongside a financial return. Identifying clear outcomes and establishing impact metrics for transportation projects can be an obstacle, since the mobility sector is a critical—but often little-acknowledged—component for providing access to health, education, and employment (Tun et al. 2021).

Financing and Other Funding Opportunities

To incorporate EVs at airports, business models from the surface transportation sector—such as EvGo and other fast-charging infrastructure for cars as well as Tesla superchargers—demonstrate the value that private companies place on providing electrification infrastructure. Similar P3 structures could be utilized for infrastructure related to other emerging ground access modes. Since upgrades to power capacity will need to support additional loads, depending on current capacity and existing demands, third-party entities—such as energy service companies and renewable energy providers—may also be able to offer alternative modes of project delivery and power generation to offset capital and infrastructure needs at airports. However, consider whether equipment or infrastructure funded with private capital will be owned by the private sector or provided for the exclusive use of private companies, such as AAM or uncrewed aerial

![The legend shows Metro rail and station (under construction); L A X and Metro Transit Center station [design in progress]; and Los Angeles World Airports (L A W A) automated people mover (A P M] route and station [design in progress]. All are subject to change. The metro rail will extend along Aviation, with a station at Century. There will also be a stop at L A X and metro transit center station, near the metro maintenance facility. The proposed A P M will begin at L A W A conrac; make stops at L A W A international transportation facility (I T F) east and L A W A, I T F west; then continue to Los Angeles International Airport.](https://uwnxt-test.nasx.edu/read/28600/assets/images/img-217.jpg)

system (UAS) operators, since grants and loans will be more restricted (as further described in the section on grant assurances).

Cities and states may also fund capital projects for micromobility systems, such as docked bikeshare systems, through major donors in the city, or these projects may be city-funded with small donors. Venture capital funding also largely supports micromobility capital investments. Other federal funding programs that provide funding for shared micromobility facilities include the STBG Program and the CMAQ Improvement Program.

For water transportation systems, FHWA has a Ferry Boat and Terminal Facilities Construction Program to provide grant assistance. According to Title 23 of the U.S.C. Section 129, such funding applies to projects for which

- It is not feasible to build a bridge, tunnel, or other normal highway structure instead of a ferry;

- The vessels and the terminal facility shall be at least publicly owned or operated, or majority publicly owned;

- The operating authority and the fares charged shall be under the control of the state or another public entity; and

- All revenues shall be applied to actual costs, including operation, maintenance, and repair.

Grant Assurances and Compliance

Airports receiving federal funding are subject to additional applicable statutory or regulatory requirements, such as general procurement, Buy American Act, and domestic preference requirements. These obligations are referred to as grant assurances, and some are specific to the implementation of awarded projects. The AIP handbook (Federal Aviation Administration 2019) specifies three sets of grant assurances for AIP-funded projects, categorized by sponsor and project type:

- Airport sponsors.

- Planning agency sponsors, such as metropolitan planning agencies and state planning agencies.

- Airport sponsors undertaking noise-computability program projects.

Airport sponsors that are part of a State Block Grant Program may be subject to additional grant assurances.

Airport owners using federal funds to fund the implementation of emerging ground access infrastructure projects at airports must understand the applicability of specific grant assurances and potential compliance challenges, since the duration and applicability for each set of assurances vary with the project’s progress; some assurances last for the useful life of the project, up to 20 years from the grant acceptance date (except for land acquisition grants, for which assurance obligations do not expire).

Table 35 summarizes the duration and application of grant assurances for airport sponsors as outlined in the AIP handbook.

This section highlights a selection of grant assurances that are meaningful in the context of implementing ground access transportation modes at airports. Since several agencies and local authorities may have an influence on transportation access projects implemented at the airport, the grant assurances listed as follows reiterate the need to engage with stakeholders early in the process (Federal Aviation Administration 2022a):

- Grant Assurance 6, Consistency with Local Plans: “The project is reasonably consistent with plans (existing at the time of submission of this application) of public agencies that are authorized by the State in which the project is located to plan for the development of the area surrounding the airport.”

Table 35. Duration and Application of Grant Assurances for Airport Sponsors

| Applicability Period | Grant Assurance |

|---|---|

| Must be met before a grant is offered | #2 Responsibility and Authority of the Sponsor #3 Sponsor Fund Availability #4 Good Title #6 Consistency with Local Plans #7 Consideration of Local Interest #8 Consultation with Users #9 Public Hearings #12 Terminal Development Prerequisites |

| Applies until the grant is closed | #1 General Federal Requirements (except for 49 CFR Part 23) #10 Air and Water Quality Standards #14 Minimum Wage Rates #15 Veteran’s Preference #16 Conformity to Plans and Specifications #17 Construction Inspection and Approval #18 Planning Projects #32 Engineering and Design Services #33 Foreign Market Restrictions #34 Policies, Standards, and Specifications #35 Relocation and Real Property Acquisition |

| Applies for 3 years after the grant is closed | #13 Accounting System, Audit, and Record Keeping Requirements #26 Reports and Inspections |

| Applies for the useful life of the project (not to exceed 20 years from the grant acceptance date) except in the case of a land acquisition grant, for which the useful life is indefinite, and the assurance obligations do not expire | #5 Preserving Rights and Powers #11 Pavement Preventive Maintenance (This applies to all of the airfield pavement on the airport, not just the specific pavement in the grant.) #19 Operations and Maintenance #20 Hazard Removal and Mitigation #21 Compatible Land Use #22 Economic Nondiscrimination #24 Fee and Rental Structure #27 Use by Government Aircraft #28 Land for Federal Facilities #29 Airport Layout Plan #36 Access by Intercity Buses #37 Disadvantaged Business Enterprises (See 49 CFR Parts 23 and 26, since certain program requirements may extend the obligation beyond the 20-year period, while the Disadvantaged Business Enterprise requirements for the project apply until the project is closed.) #38 Hangar Construction #39 Competitive Access |

| Lasts for as long as the airport is owned and operated as an airport | #23 Exclusive Rights #25 Airport Revenue #30 Civil Rights #31 Disposal of Land |

Source: FAA (2019), Table 2-5: Duration and Applicability of Grant Assurances (Airport Sponsors)

- Grant Assurance 7, Consideration of Local Interest: “It has given fair consideration to the interest of communities in or near where the project may be located.”

- Grant Assurance 8, Consultation with Users: “In making a decision to undertake any airport development project under Title 49, United States Code, it has undertaken reasonable consultations with affected parties using the airport at which project is proposed.”

Furthermore, Grant Assurance 25, Airport Revenue, restricts airport revenue from being diverted to non-airport projects, such as landside access projects beyond the airport’s property line: “All revenues generated by the airport and any local taxes on aviation fuel established after December 30, 1987, will be expended by it for the capital or operating costs of the airport; the local airport system; or other local facilities which are owned or operated by the owner or operator of the airport and which are directly and substantially related to the actual air transportation of passengers or property; or for noise mitigation purposes on or off the airport” (Federal Aviation Administration 2022a).

Additionally, Grant Assurance 36, Access by Intercity Buses, states that airport owners or operators will permit, to the maximum extent practicable, intercity buses or other modes of transportation to have access to the airport; however, airports are not obligated to fund the construction of special facilities for intercity buses or for other modes of transportation.

Potential Impact on Airport Financial Performance

As airport sponsors may be looking at potential funding and financing programs to fund ground access infrastructure at airports, there are several potential financial impacts for deploying emerging ground access infrastructure and equipment at airports to consider. Shifts in airport access by ground transportation mode as airports work to implement new ground access technologies at their facilities may have significant impacts on the financial performance and infrastructure investment planning of airports. As such, airport stakeholders need to consider the long-term revenue stream for operating and maintaining these ground access facilities.

Parking revenues represent a primary source of revenue for many airports, and more often than not they are the largest source of non-aeronautical operating revenues; therefore, any reduction in revenue will have a direct impact on an airport’s operating budget. As AVs enter the market, this will have an impact on traditional parking fees typically collected, and airports will need to explore ways to offset or replace lost parking-related revenues and examine opportunities for alternative revenue generation.

Alternative revenue sources can help offset revenue leakage from increased ridesharing and use of AVs at airports. Some of these alternatives may include implementing landing fees on urban air mobility (UAM) operators as they use parking roof decks or other on-airport facilities to build and operate their vertiports. Furthermore, establishing creative user service fees for using electric charging stations can help recoup investment in charging infrastructure for EVs. For instance, in 2017, ATL installed over 100 new electric charging stations in the parking deck. More specifically, airports can develop business plan agreements with electric vehicle–charging service providers (EVSPs) to provide charging hubs at their facilities. Depending on the agreement, this may also provide land lease revenue to an airport through leasing its property to EVSPs. Other methods could include partnering with local utilities companies in exchange for carbon credits needed by the utility company, similar to states with credit trading mechanisms for clean fuels (e.g., California’s Low-Carbon Fuel Standard) (Carreon et al. 2022).

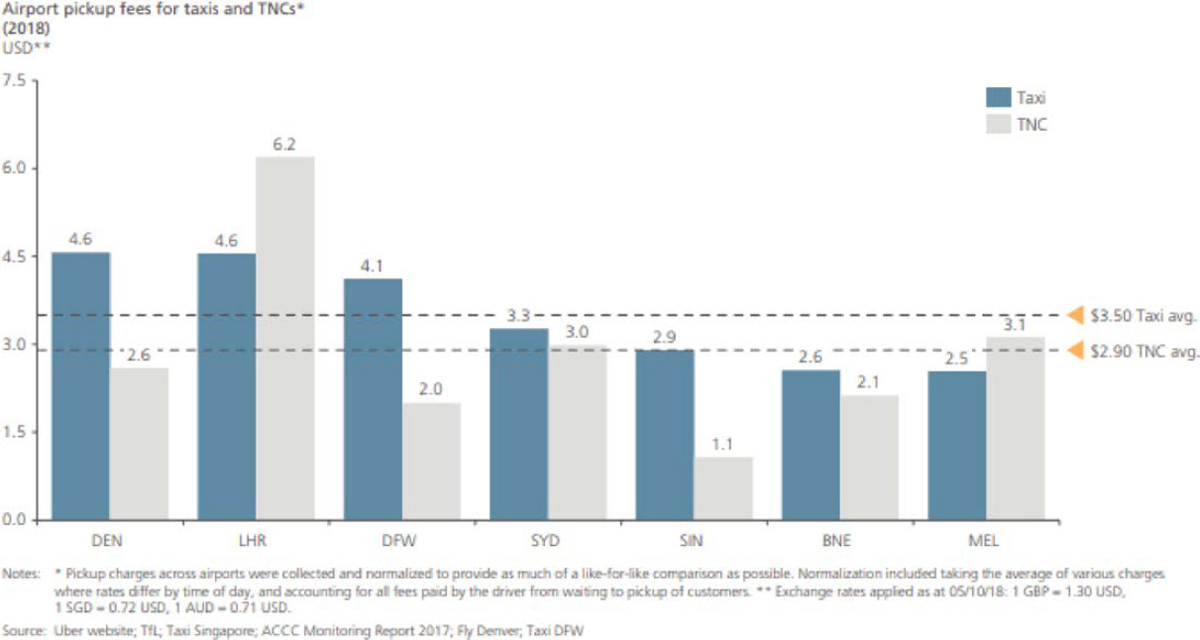

In addition, permitting fees collected from various operators (ride-hailing, future AV operators, and BRT operators) can help airports generate additional revenue as well as ground access fees collected from transport operators (e.g., TNCs). However, access charges vary by mode. According to a report published by L.E.K. Consulting on the future of airport ground access (Streeing et al. 2018), TNCs generated less revenue per passenger than parking, rental cars, and taxis at several airports because TNC access charges were lower than charges levied from taxis or short-term parking (Figure 82). As a result, airports’ financial performance may be negatively impacted in the absence of dynamic financial and feasibility studies that consider all ground transport operators at an airport, as well as flexible rate structures and dynamic parking pricing that capture changes and shifts in ground access modes. However, emerging ground access may also result in a positive financial impact as travelers shift from private pick-up and drop-off (considered nonrevenue-generating) to using TNCs instead, resulting in a potential net increase in ground transport revenues collected.

Airports can also consider implementing ground access vehicle fees in their CTAs as another potential method to offset lost parking revenues while reducing congestion in CTAs at heavily congested airports. When implementing curb pricing and vehicle fees in the CTA, consider technological support requirements and operational costs (credit card fees, agency staffing costs,

Source: Streeing et al. (2018)

consultant and contracted services, general facility maintenance, routine operating and maintenance [O&M] costs for revenue collection, etc.), business case feasibility, certain exemptions to ground access fees (e.g., ADA vehicles, government vehicles, high- occupancy vehicles [HOVs], airport employees), and public acceptance toward implementing the chosen fee structure. Furthermore, a variety of pricing strategies and feasible fee scenarios should be examined for qualified vehicles based on the identified travel markets at the airport. Recently, LAX has been looking at implementing a ground access vehicle fee, for both privately owned and commercial vehicles, as a strategy to reduce traffic congestion in the CTA by promoting HOV use, manage vehicle travel across multiple access points, reduce vehicle miles traveled through mode shift, and provide a source of revenue to offset investments in ground transportation management at the airport.