Enhancing Airport Access with Emerging Mobility (2025)

Chapter: 1 State of Airport Access

CHAPTER 1

State of Airport Access

Defining Airport Access

According to U.S. DOT, airport access is “the process by which people and goods travel from their local origins to nearby airports. The people include air passengers, airport and airline employees, persons accompanying the air passenger to the airport, and casual visitors. The goods include freight, mail, fuel, and items used at the airport” (Gorstein et al. 1978).

In this report, “airport ground access” may also include on-airport mobility (e.g., transfer between terminals) as well as the cut-through traffic generated by non-airport users (e.g., members of communities living near the airport) using the airport’s ground transportation services, primarily developed for airport access, to reach their destinations.

Airport access is a critical component of the airport ecosystem and capacity chain. Inadequate ground access can become a serious bottleneck that can undermine the capacity and efficiency of the whole airport. In June 1977, the Senate Committee on Appropriations’ (1977) Report No. 95-268 directed the FAA to “undertake a comprehensive study on the constraints imposed on air travel and airport capacity by inadequate ground access.”

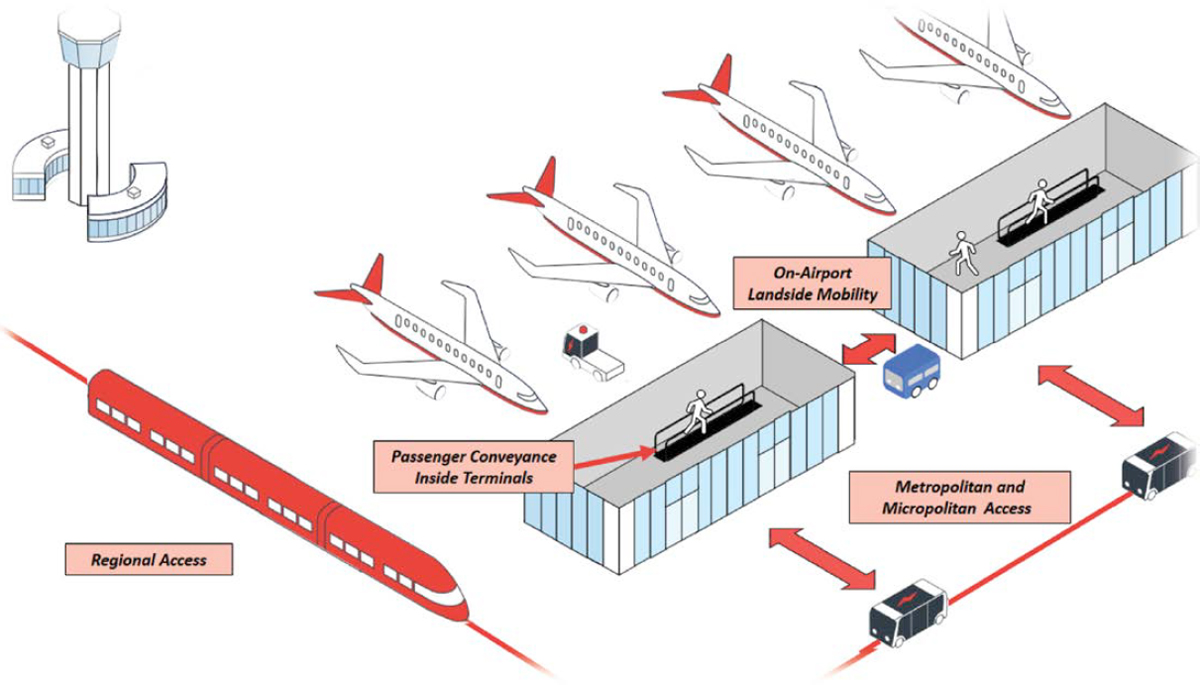

According to Ross (1975), there are four categories of airport access systems: (1) distribution within the airport, (2) circulation between airport complexes and environs, (3) access to the airport complex from remote points in urban areas, and (4) regional high-speed systems. For this report, the categories were expanded to account for rural areas and adapted to focus on the more user-centric concept of mobility rather than transportation systems. These categories, shown in Figure 1, are as follows:

- Passenger conveyance inside terminals: moving people and goods between different parts of the passenger-terminal area, mostly within the sterile area.

- On-airport landside mobility: connecting different facilities across airport property (e.g., passenger-terminal building, parking facilities, employee lots, and rental cars).

- Metropolitan and micropolitan access: providing access from the various points of the primary catchment area served by the airport.

- Regional access: expanding the outreach of the airport beyond a metropolitan or micropolitan area, and without consideration for state or county limits. Per the U.S. Census Bureau (2021), a micropolitan area is an urban cluster or area with a population of at least 10,000 but fewer than 50,000 people.

This report on airport ground access primarily focuses on metropolitan/micropolitan and regional access systems. Chapter 13 investigates how ground access modes and technologies can be leveraged to provide passenger conveyance and on-airport landside mobilities.

Use Cases of Airport Access

There are many reasons why people and goods might use various airport access modes and services. Airport users and employees can be grouped under these categories:

- Airline passengers going to the airport to take a flight or leaving the airport to reach their final destination.

- “Meeters and greeters” dropping off or picking up passengers.

- Airport employees, including airline, concession, and tenant employees, commuting between their home and the airport for work.

- Commercial pilots and crews, either commuting to and from home or shuttling to and from a hotel.

- Private pilots and their guests, including based and transient aircraft (Germolus 2020).

- Attendees of special events, such as air shows (Prather 2013).

- Plane spotters, which include plane photography hobbyists and individuals and families visiting observation decks and other spotting areas around the airport.

- Non-aviation users of the airport, such as those attending conferences at the airport or participating in another community use (Kramer and Seltz 2011; Karaskiewicz and Swanson 2022). A subset of this category is non-aviation passengers, with some airports being used as multimodal facilities where users might connect between different modes of ground transportation.

Non-airport users can also leverage airport access. These users include

- Community members benefiting from the convenience of mass transit systems developed for airport access;

- Mass transit users who commute on transportation services that serve the airport but disembark at a stop along the way; and

- Patrons and employees of “airport cities” and “aerotropolises” when offices, businesses, residential areas, as well as retail, entertainment, and cultural centers are built at or in the immediate vicinity of the airport.

Airport access is likewise vital to bring freight and deliveries to the airport:

- Freight access processed at the airport, such as

- – Air-freight items brought to the airport for shipment by plane,

- – Ground freight items arriving at the airport that are processed at logistic warehouses and leave the airport by truck, and

- – Parts and large payloads delivered at industrial sites located at the airport (e.g., aerospace manufacturing).

- Deliveries of goods and supplies required to operate the airport facilities, including

- – Refrigerated and non-refrigerated food and beverages for airport concessions and airline catering;

- – Other goods for airport retail;

- – Materials and special equipment for construction projects, maintenance, etc.; and

- – Fuel deliveries for ground vehicles and aircraft, either by tanker truck or pipeline.

Needs and expectations often vary by use case, potentially leading to different mode choices for each one.

What Is a Mode of Transportation?

The term “mode of transportation” is typically used to distinguish between different ways of transporting people and goods. Its definition varies depending on the context, purpose, and need. For instance, the Administrative Code of the State Oil and Gas Board of Alabama, Section 400-1-1-.05, states that “mode of transportation shall mean any waste transportation method including trucks, rail cars, barges, maritime vessels, aircraft, or any other means of transportation acceptable to the [State Oil and Gas] Supervisor” (Alabama Administrative Code 2010). On the other hand, the Utah Code provides a broader definition in which “‘mode of transportation’ means a device or animal in, on, or by which a person may be transported” (Utah State Legislature 2016).

A mode is often defined by the type of media used to support the movement (e.g., ground, water, air, space, cable, pipeline) or the technology itself (e.g., car, light rail, train, plane). While such definitions satisfy most occasions, they do not always address the diversity, versatility, and fluidity of certain use cases. For instance, the tram-train (e.g., Rhônexpress, France; Kassel RegioTram, Germany; and Puebla-Cholula Tourist Train, Mexico) is a hybrid light rail transit (LRT) vehicle that provides both urban and regional rail transportation. It can operate on LRT and intercity rail tracks with different operating rules and equipment to address conurbations—extended urban areas that typically consist of several towns merging with the suburbs of one or more cities—and “rurban” patchworks of small communities located around larger urban centers. Bus rapid transit (BRT) systems have typical LRT features, but they are operated with bus vehicles.

Le Bris (2018) proposed a new definition of mode that approaches “mode of transportation” as a specific combination of a need, a technology, a concept of operation, and a business model, on the basis that any variation in these parameters can completely change the way a technology is used, the way a market is served, or a community’s access to mobility. In this definition, transportation technology is an enabler of the transportation mode.

From Transportation to Mobility

Movement is the physical displacement required to reach an activity (i.e., the act of moving). This can be achieved through one or multiple means of transport, including walking, personal transport (e.g., bicycles, scooters), public transit, or private vehicles.

Mobility describes the ease of movement between locations, using one or more means of transport, to meet daily needs. Mobility depends on several factors, including average travel time, travel time variation, and travel costs; high mobility is attained when travel times and costs are low. Mobility systems are networks that determine which locations can be accessed from a starting location at a specific point in time (European Local Transport Information Service 2019; National Research Council 2002; Tyler 2016).

Accessibility is the ability to approach, reach, and enter (i.e., access) a desired activity, the ultimate goal of transportation. Accessibility has two components: mobility (i.e., how easily people can travel) and land use (i.e., whether the location itself facilitates access). For an activity to be accessible, an “unbroken chain of movement” must exist for all travelers—especially people with disabilities and elders—and planning improvements such as mixed-use development, walkability, and multimodality are recommended. If some members of society are unable to access an activity, then the activity is effectively nonexistent for them (Litman 2003; World Bank 2022; Tyler 2016).

Connectivity describes whether it is possible to access one location from another location, either directly or through intermediate locations within a transportation network (i.e., nodes). Public transit network planning is strongly driven by the potential for connectivity through interchanges between multiple system lines and different modes of transport (Rodrigue 2020). Connectivity enhancements benefit travelers by increasing the range of activities available to them (accessibility) and reducing the cost and time required to access them (mobility).

Mode Availability at Commercial Service Airports

For operational efficiency and customer experience, the first and last miles (FLM) are the “last frontier” for commercial service airport operators and air carriers. Airports and airlines typically do not have direct control over this segment of the passenger journey. Also, many metropolitan areas have endemic roadway congestion. This is not a new problem—Paules et al. (1971) reported that “access links to the airport are a prime cause of airport congestion. [. . .] The traveler must build large time/safety factors into his schedule because of the uncertainties of road congestion.” This statement is still true for many travelers. As these authors predicted in 1971, “Undoubtedly, the airport access problem will continue to be closely related to the urban problem. For instance, airport access systems must be fairly extensive in order to collect and distribute passengers having widely dispersed origins and destinations.”

In the United States, personal vehicles are the primary mode of transportation used to access airports. However, most large-hub airports are connected to their primary service area through at least one mass transit system that has connections to a larger metropolitan public transportation network. In November 2022, the Washington Metropolitan Area Transit Authority (WMATA) opened the Silver Line extension to Washington Dulles International Airport (IAD), connecting the Metrorail system to one of the few large U.S. hubs that previously had no option for direct rail transit.

Public transit alternatives are important to passengers, providing an affordable and convenient mode of transportation to the airport. Transit alternatives also improve resilience, since diversifying mobility options reduces the public’s reliance on a single transportation system.

Table 1. Availability of Mass Transit Services at the Top 10 Busiest U.S. Airports

| Airport | Public Bus | Bus Rapid Transit | Light Rail | Heavy Rail (Metro/Subway) | Commuter & Regional Rail | Intercity & High-Speed Rail |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ATL | ✔ | ✔ | ||||

| LAX | ✔ | Under constructiona | ✔ | |||

| ORD | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | |||

| DFW | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | |||

| DEN | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | |||

| JFK | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | |||

| SFO | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | Under constructionb | ||

| SEA | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | |||

| MCO | ✔ | ✔ | ||||

| LAS | ✔ |

Source: Bureau of Transportation Statistics (2020)

Note: ATL = Hartsfield–Jackson Atlanta International Airport; DEN = Denver International Airport; DFW = Dallas Fort Worth International Airport; JFK = John F. Kennedy International Airport; LAS = Harry Reid International Airport; LAX = Los Angeles International Airport; MCO=Orlando International Airport; ORD = Chicago O’Hare International Airport; SEA = Seattle-Tacoma International Airport; SFO = San Francisco International Airport.

a Metro Line K extension.

b California High-Speed Rail.

Mass transit can improve the commute for airport workers, increase the attractivity of airport jobs, and broaden the pool of potential job candidates. Table 1 summarizes the available mass transit services at the top 10 busiest U.S. airports.

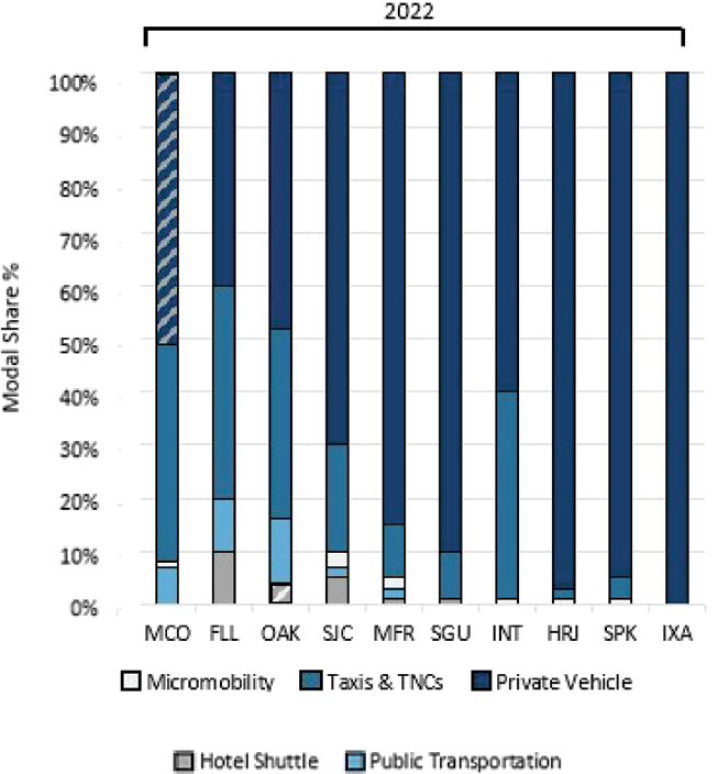

Nevertheless, most U.S. airports lag behind their foreign counterparts in mass transit use for multiple reasons, including the affordability of car transportation (compared to other nations), perception that mass transit offers a low level of service (LOS), limited accessibility of mass transit, and inadequate frequency and number of stops. In other words, mode choice is highly dependent on mode affordability, accessibility, and availability. Better dissemination of more efficient and consistent mass transit technologies, a greater focus on the LOS from transit authorities, increasing costs of private vehicle ownership, and evolving social expectations can challenge the status quo. Figure 2 depicts landside mode statistics at 10 U.S. airports.

Ground Access at Smaller Airports

Ground access is vital for large and small airports alike. According to ACRP Synthesis 111: Last Mile in General Aviation—Courtesy Vehicles and Other Forms of Ground Transportation (Germolus 2020), providing connectivity to the local community or region served by a general aviation airport is essential for serving airport users and generating economic benefits, regardless of the facility’s size. Users of small airports rely on ground transportation alternatives for many reasons, and a lack of alternatives can illustrate a disconnect from the airport and the community. Limited ground access can even be a determining factor in whether a traveler chooses to land at one airport over another.

Note: FLL = Fort Lauderdale/Hollywood International Airport; HRJ = Harnett Regional Jetport; INT = Smith Reynolds Airport; IXA = Halifax-Northampton Regional Airport; MCO = Orlando International Airport; MFR = Rogue Valley International–Medford Airport; OAK = San Francisco Bay Oakland International Airport; SGU = St. George Regional Airport; SJC = Norman Y. Mineta San José International Airport; SPK = Spanish Fork Municipal/Woodhouse Field Airport; TNCs = transportation network companies.

Ground access needs and expectations for general aviation airports are also different from those of most commercial service airports. Understanding the needs and developing adequate solutions for the full range of user categories and use cases is an important step in addressing the demand. Pilots and passengers might fly to general aviation facilities for refueling or a break between flights, but they may also need to go to nearby towns to eat a meal, work, or attend an event. In a 2020 survey performed for ACRP Synthesis 111 (Germolus 2020), the highest needs identified for ground transportation at general aviation airports were for business (84 percent), dining (78 percent), and lodging (59 percent).

Some general aviation airports are in underserved communities or “mobility deserts,” where both public transportation and on-demand rides are difficult to access. ACRP Synthesis 111 (Germolus 2020) identifies several strategies taken by airports, some in collaboration with third parties, to provide first- and last-mile alternatives, including diverse initiatives such as borrow-a-bike programs, courtesy vehicles, and on-demand public transportation. Figure 3 provides an example of such an initiative, developed by the Idaho Aviation Association. Airports can also use rural transit programs or develop demand-responsive transport; such accessibility solutions are often well-suited for rural and smaller communities (Vanasse Hangen Brustlin, Inc. 2019).

Source: Germolus (2020)