Enhancing Airport Access with Emerging Mobility (2025)

Chapter: 5 Connected and Automated Vehicles

CHAPTER 5

Connected and Automated Vehicles

Introduction

Connected and automated vehicles (CAVs) are the product of decades-long research and development efforts to improve road travel safety and comfort. CAVs have emerged as an integration of two technologies into a single product: connected vehicles—which use both internet and local networks to allow data exchanges with cloud servers and nearby vehicles, pedestrians, and infrastructure—and automated vehicles (AVs), which can automate some or all driving tasks (e.g., steering, acceleration/deceleration, traffic signal compliance, and object detection and avoidance) through sensory inputs and specialized algorithms (Ha et al. 2020). CAVs leverage both connectivity and automation to remove human operators from the driver’s seat, thereby removing the likelihood for human error. Human choices such as speeding, distracted driving, and driving under the influence have been linked to 94 percent of serious motor vehicle crashes (National Highway Traffic Safety Administration 2017).

While promising, advanced CAV technologies are still nascent and remain under progressive development, with only limited driving assistance features now available in newer personal vehicles. Truly “driverless” vehicles, where all occupants of the vehicle are always passengers, are undergoing initial testing in urban environments but are not projected to be a significant part (>25 percent) of the U.S. traffic mix until 2045 (Bansal and Kockelman 2017).

Use Cases

The development and implementation of more advanced connected and automated driving technologies will have a significant impact on the larger transportation industry and users’ daily life. With the growth of the transportation sector and CAV technology, potential use cases have also been evolving and advancing rapidly. CAV technologies can be applied in five main areas, according to the SAE International’s Fundamentals of Connected and Automated Vehicles (Wishart et al. 2022):

- Long-haul trucking: The first application for CAVs is expected to be in the long-haul trucking sector because (a) the additional cost of the automation system is less of a barrier for commercial trucks, which can already cost hundreds of thousands of dollars, and (b) long-haul trucks typically travel through environments like freeways and highways, which are less complex than environments frequently encountered in urban driving. Long expanses of flat, straight roads may be driven in long-haul trucking for days on end, which can lead to driver tiredness and inattention. While these factors impact driver recognition errors and judgment mistakes, which are the primary cause of traffic accidents on roads (National Highway Traffic Safety Administration 2015), the same circumstances make automated driving possible.

- Delivery: CAVs can reduce the number of work hours for human drivers of delivery vehicles, which can save money, and they can also eliminate the necessity for occupant safety precautions. For instance, some CAV delivery vehicles have been granted a temporary exemption by U.S. DOT to eliminate features that are typically used to protect passengers and aid drivers, like side-view mirrors and the windshield. Many of the current laws governing vehicle safety are less relevant to CAVs because these low-speed delivery vehicles are not designed to transport passengers. Some organizations are investigating the use of smaller CAVs on sidewalks or bike lanes, which would reduce car collisions but add new bike and pedestrian safety concerns.

- Last-mile connections: CAV shuttles and circulators can provide efficient and effective last-mile connections between transportation hubs—such as railway stations, transit hubs, and parking facilities—and nearby locations that are too far away to be safely or comfortably covered on foot. As of 2021, there are already instances of this kind of service being provided in communities, in business parks, and on university campuses across the world. CAVs acting as last-mile connections often travel a set of predetermined routes inside a restricted geographic region and frequently at low speeds, which reduces their localization and perception challenges. Several businesses, such as Local Motors, EasyMile, May Mobility, and Navya, are creating vehicles made especially for these kinds of services.

- Robo-taxis: Similar to last-mile connectivity, robo-taxis will be a fleet of cars operated by bigger corporations instead of being privately owned automobiles. Most of today’s privately owned cars and taxis offer point-to-point transportation across short distances. Even though CAVs are still too expensive for most individual owners, they could be economically viable as taxis and ride-hailing cars since they do not require human drivers and can operate around the clock, with just periodic stops for refueling (or recharging, depending on the powertrain). In the Phoenix, Arizona, metropolitan region, Waymo One provides limited automated taxi services without a safety driver (i.e., not all Waymo One cars have a safety driver); and as of 2021, it is one of the most well-known robo-taxi providers.

- Personally owned vehicles: Personally owned CAVs will most likely be the last use case implemented. Fleet-based and commercially owned CAV systems are now the focus of much of the industry. To make individually owned CAVs a reality, there will need to be considerable changes in the law, performance, price, and public opinion. Aside from newer difficulties, Tesla has made some of the most advanced deployments to far, prepping many of the cars it is now selling for automatic driving with over-the-air software upgrades when they become ready. By the end of the decade, according to General Motors Chief Executive Officer Mary Barra, General Motors will be selling personal CAVs (Korosec-Serfaty et al. 2021). While the time frame for personal CAVs has been the subject of many similar assertions, for economic, technological, and regulatory reasons, the future of these vehicles appears to be far less certain than that of the other areas mentioned.

Key Concepts and Definitions

Automated Vehicles

Vehicle manufacturers have gradually introduced technology into their products that enhance driving safety, either by increasing driver awareness or by performing specific driving tasks. At the degree of automation available in 2022, the object design domain (ODD)—a set of operating conditions that automation systems have been designed to function in—remains limited, but it is expected to expand as vehicles evolve from having driver support features (driver performs some driving tasks) to automated driving features (either driverless or with a driver in a supervisory role) (SAE International 2021).

Vehicles with driver support features are equipped with advanced driver assistance systems (ADAS), which comprise a wide range of features that improve driving safety but still require drivers to remain aware of their driving environment and provide adequate responses to events (i.e., object and event detection and response [OEDR]). Vehicles with automated driving features, by comparison, are equipped with automated driving systems (ADS), which can provide sustained execution of all operational and tactical tasks required for a vehicle in on-road traffic conditions (i.e., the entire dynamic driving task [DDT]). These vehicles should require no human input for steering, accelerating, and braking, but some still require a driver to monitor the performance of ADS and, if necessary, intervene (Minnesota Department of Transportation n.d.).

While the terms “autonomous vehicle” and “automated vehicle” have been used interchangeably in the past, SAE International (2021) has deprecated the former term. This is based on two definitions of autonomy. From a functional perspective, autonomous systems must be able to perform tasks and make decisions independently and self-sufficiently; however, CAVs that rely on any external entities to aid decision-making (e.g., other CAVs or traffic infrastructure) cannot be considered self-sufficient. Likewise, the legal definition of autonomy argues that such a system should be capable of self-governance; CAVs do not pass that test either, as they are limited to obeying the commands of their developers (algorithms) and their users (input). This report follows this guidance and uses the term “automated vehicle” exclusively.

Levels of Driving Automation

The automation in CAVs is defined based on ADAS/ADS capability levels as well as system performance. SAE International (2021) maintains a classification of these levels in Surface Vehicle Recommended Practice J3016: Taxonomy and Definitions for Terms Related to Driving Automation Systems for On-Road Motor Vehicles, which have been adopted by federal and state agencies for policymaking purposes. These levels of automation are outlined in Table 18 and are limited to assessing the “actual” driving of the vehicle: Planning tasks—such as setting destinations and departure times—are not considered.

Levels 0–2 include some automation, but the driver oversees all or a portion of the DDT. (The DDT comprises all of the tactical and operational tasks needed to drive a vehicle in on-road traffic in real time.) In Levels 0–2, a human driver is still performing the DDT, but depending on the feature, the system may monitor, inform the driver, or intervene. The driver is responsible

Table 18. SAE’s Levels of Driving Automation

| Level | Level Name | ADAS/ADS Capabilities | System Performs All Driving Tasks |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | No Driving Automation | ADAS: Driver carries out all driving tasks but may be aided by active safety systems. | No |

| 1 | Driver Assistance | ADAS: System handles either lateral or longitudinal motion control, but not both. | No |

| 2 | Partial Driving Automation | ADAS: System handles lateral and longitudinal motion controls. Driver remains responsible for OEDR. | No |

| 3 | Conditional Driving Automation | ADS: System can carry out tasks within its ODD but may require and notify a human driver to intervene (fallback). | Yes |

| 4 | High Driving Automation | ADS: System can carry out tasks within its ODD with no expectation for the user to intervene. | Yes |

| 5 | Full Driving Automation | ADS: System can carry out tasks within its ODD as well as tasks not specific to it, without needing human intervention. | Yes |

Source: SAE International (2021)

for driving the vehicle. In Levels 1–2, the system performs steering or acceleration and braking when engaged, thus providing driver support features.

In Levels 3–5 of automation, the ADS oversee the entire DDT when activated and provide automated driving features. These vehicles are referred to as self-driving vehicles or highly automated vehicles (HAVs), but these terms are neither uniformly nor officially defined. Vehicles with Level 3 automation are conditionally “self-driving,” but they cannot be considered “driverless” since they will require the human driver to take control when specific operating conditions are met. Conversely, vehicles with Levels 4 and 5 ADS fit the criteria of “driverless automobile” because humans are not expected to intervene; instead, they can all be passengers in these vehicles. NHTSA (2021) specifies that vehicles with automation Levels 3–5 are not available for consumer purchase in the United States; Germany and Japan have enacted regulations sanctioning circulation of vehicles with ADS Level 3 manufactured by Mercedes-Benz and Honda, respectively (Sugiura 2021). Waymo in the United States is testing limited ADS Level 4 operations (Ackerman 2021).

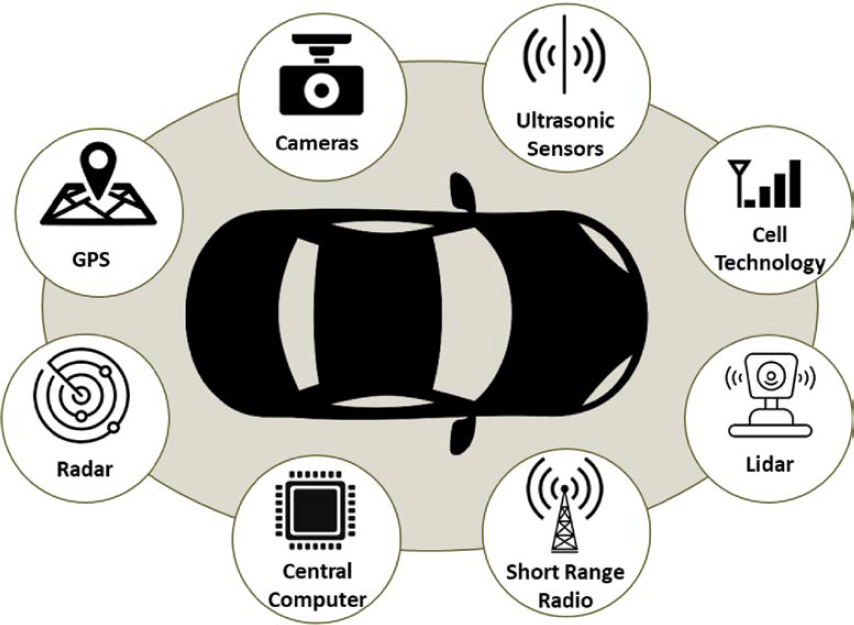

Automated driving features require a combined group of complementary sensor hardware and software to be installed on a vehicle and designed to provide the required information. Figure 42 displays examples of typical CAV systems that support automated driving features.

Table 19 provides an interpretation of the SAE levels of driving automation in terms of potential driving implications when riding within or outside of compatible service areas. A service area is a geofenced area where certain driving automation features can be safely activated. This area can be associated, for instance, with georeferenced data—an adapted digital and physical infrastructure—vehicle-to-everything (V2X) communication, and minimum equipment requirements for vehicles to safely perform all driving tasks autonomously. Table 19 outlines the transition from human-driven vehicles to fully autonomous vehicles and indicates the evolving role of automation for vehicles located inside a compatible service area.

Table 19. Potential Driving Implications of Automated Driving Features

| SAE Level | Outside of Automated Driving Service Area | Within Automated Driving Service Area |

|---|---|---|

| Level 0 | Human driving (no assistance) | Human driving (no assistance) |

| Level 1 | Human driving with ADAS | Human driving with ADAS |

| Level 2 | Human driving with ADAS | Human driving with ADAS |

| Level 3 | Human driving with ADS | Self-driving ADS, with human override when necessary |

| Level 4 | Human driving with ADS | Self-driving ADS (autonomous driverless mode) |

| Level 5 | Not accessible | Self-driving ADS (autonomous driverless mode) |

Note: This table assumes the automated driving service area is compatible with the SAE level of the vehicle equipment and systems, at minimum, and that such features are activated when possible.

Connected Vehicles

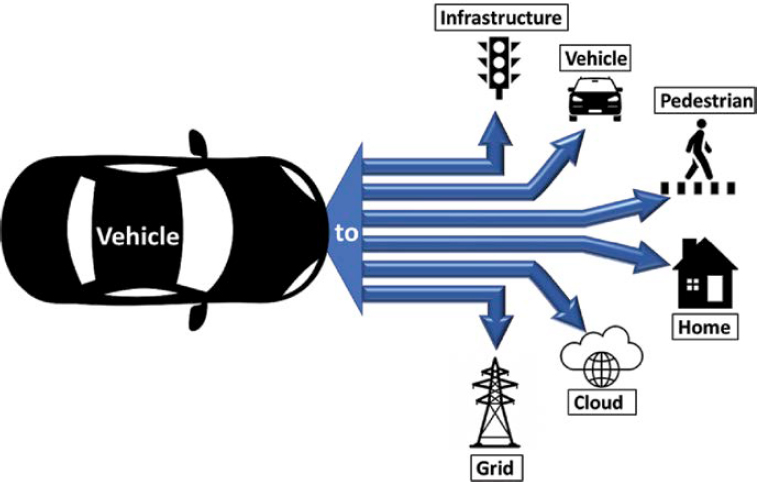

Connected vehicles use technology to interact with other connected vehicles, as well as bicycles, pedestrians, and other infrastructure and roadside objects. Traffic flow and safety will both be enhanced by the interchange of information (Minnesota Department of Transportation n.d.). The six main types of CAV connectivity, as shown in Figure 43, are

- Vehicle-to-infrastructure: technology that uses cameras and dedicated short-range communications (DSRC) to detect, parse, and exchange data with roadway infrastructure (traffic signals, roadway signs, lane markers, etc.).

- Vehicle-to-vehicle: allows for the exchange of movement information between connected vehicles. This connection can improve safety, traffic flow, and environmental impact by providing passengers with real-time information about traffic conditions, which could eliminate unnecessary stops and reach optimal fuel-efficiency. According to NHTSA (2014), this technology can avoid up to 600,000 crashes and up to 1,080 roadway deaths per year if fully implemented in the U.S. vehicle fleet.

- Vehicle-to-pedestrian: vehicles that can detect and respond to vulnerable road users’ actions as communicated via their smartphones or similar devices. Vulnerable road users are not limited to pedestrians but also include cyclists and operators of motorized two-wheelers (Sewalkar and Seitz 2019).

- Vehicle-to-home: vehicle batteries that can be used to power users’ homes as either backup power sources or as alternatives to utility power grids.

- Vehicle-to-cloud: connectivity to internet services, which facilitates software, map, and weather updates.

- Vehicle-to-grid: vehicle batteries can not only receive electricity from the power grid but also act as suppliers to the grid during peak demand.

These types of connectivity are components of the broader V2X communications framework.

Electric Vehicles

An electric vehicle (EV) is defined as “a vehicle that can be powered by an electric motor that draws electricity from a battery and is capable of being charged from an external source. An EV includes both a vehicle that can only be powered by an electric motor that draws electricity from a battery [or fuel cell] (all-electric vehicle) and a vehicle that can be powered by an electric motor . . . and an internal combustion engine,” that is, hybrid-electric vehicles (HEVs) and plug-in hybrid-electric vehicles (PHEVs) (U.S. Department of Energy 2021).

-

All-electric vehicles: All-electric vehicles include battery-electric vehicles (BEVs) and fuel cell–electric vehicles (FCEVs). (Fuel cell–electric vehicles are also called FCVs, but this report uses “FCEVs.”) The battery or fuel cell provides power to the electric powertrain.

- – Battery-electric vehicles: The battery is charged by plugging the car into a charging station or by regenerative braking. BEVs do not produce tailpipe emissions; however, the generation of power does have “life cycle” emissions, as the source of electricity can have associated emissions from generation to distribution. The driving ranges of BEVs are often shorter per battery charge than those of vehicles with conventional internal combustion engines (ICEs) per tank of gas. Depending on the model, most all-electric vehicles are built to have a battery charge last between 150 and 400 miles. The full recharge of the battery can take several hours with Levels 1 and 2 chargers, while most Level 3 devices can complete this task in less than an hour (i.e., typically 10 to 30 minutes).

- – Fuel cell–electric vehicles: Fuel cells combine hydrogen stored in a high-pressure tank with oxygen from the air to produce electricity supplied to the electric powertrain. The only tailpipe emission of this process is water vapor. Indirect emissions come from the hydrogen supply chain, from production to delivery to local hydrogen stations. Refueling the car takes about 5 minutes. Because of the weight of current battery systems, fuel cells are good candidates for long-haul, heavy-duty operations and use cases where prolonged downtime is not suitable (e.g., trucking and urban transit). However, BEVs are typically more efficient than FCEVs for short distances and light-duty operations.

- Plug-in hybrid-electric vehicles: A PHEV’s ICE and its electric motor, which draws power from a battery, can both provide propulsion. All-electric (or charge-depleting) operation is a possibility with PHEVs. PHEVs need a larger battery, which can be plugged into an electrical power source to charge, to enable operation in all-electric mode. Most PHEVs can go between 20 and 40 miles on electricity alone to satisfy a driver’s usual daily travel demands, and then they just use gasoline to continue driving, similar to a traditional hybrid.

- Hybrid-electric vehicles: An HEV is propelled by an ICE and one or more electric motors that draw electricity from a battery. Gasoline is used to power the vehicle’s ICE, which is used to recharge the battery. Since their batteries cannot be recharged from external sources, HEVs do not meet the DOE definition of an EV, but they do apply some EV operating principles.

Depending on the type of electric vehicle, batteries can be recharged in four different ways:

- Charging units/stations (BEVs and PHEVs): An external charging source supplies electricity to the EV’s batteries.

- Coasting: While an EV moves forward without using battery power, the kinetic energy generated by the wheels’ rotation is transformed into electricity.

- Regenerative braking: The motor converts some kinetic energy into electricity, whereas traditional brake pads cause energy loss through heat.

- Internal combustion engine (HEVs): Since HEVs cannot be charged externally, the ICE uses gasoline to recharge HEV batteries.

Key Components of Automated Driving Systems

Wishart et al. (2022) identify three interconnected systems that allow for ADS operations:

- Perception system: This system is required to detect objects in the environment, classify and locate objects, and determine the speed and direction of each safety-relevant object. A vehicle’s perception system must also be able to locate the vehicle on its detailed, 3D map of roads within the conditions and function of its driving automation system, as well as determine speed, acceleration, and orientation. Maps can be locally stored or provided by outside sources, with real-time updates also contemplated.

- Path planning system: Once the vehicle’s surroundings are “perceived,” the path planning system determines a path to be followed based on the vehicle mission and characteristics of the identified objects. Unlike broader applications of route planning, generated paths are developed to obey traffic rules (e.g., lane following and speed limit compliance) and maintain safe distances from other objects (e.g., vehicles, pedestrians, and construction equipment). Path planning systems are also programmed to identify and adequately respond to different traffic scenarios, such as four-way stops and uncontrolled intersections.

- Actuation system: This system uses the vehicle’s motion controls (i.e., steering, acceleration, and deceleration) to follow the path developed by the planning system.

Traffic and Roadway Engineering Aspects

Integration and Impact of CAVs in the Roadway Environment

Mass introduction of CAVs in U.S. roads is expected to take several decades to occur; Gopalakrishna et al. (2021) estimates that HAVs (Level 3 and above) will account for 10 percent of the global vehicle market by 2030. However, studies on their potential impact on traffic flow are still being conducted. Theoretically, CAVs operate under close communication with their environment, have a higher situational awareness than human drivers, and are capable of significantly faster reactions than humans—these factors should all lead to shorter headways between multiple CAVs.

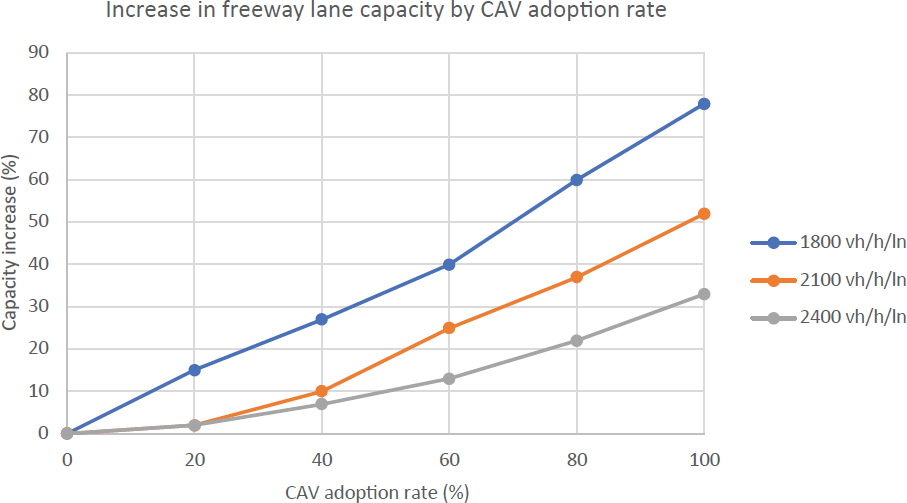

The Highway Capacity Manual: A Guide for Multimodal Mobility Analysis, 7th Edition (HCM7) (2022) incorporated—for the first time—considerations on potential changes to freeway capacity because of increased proportions of CAVs in roadways. With specific concern to headways, HCM7 postulates these assumptions:

- The average bumper-to-bumper gap between two conventional vehicles is approximately 1.1 seconds.

- The average gap between cars in a “platoon” (i.e., a group led by a CAV and followed by other CAVs in the same lane, with a maximum size of 10 cars) ranges between 0.6 and 1.1 seconds,

- with an average of 0.71 seconds. These times were computed based on technical analyses and users’ safety preferences.

- The average gap between CAV platoons is 2.0 seconds.

These assumptions suggest that low adoption of CAVs would lead to an increase in vehicular congestion compared to a baseline of no CAVs, and increasing returns in freeway capacity should be expected, as shown in Figure 44.

The results of Guériau and Dusparic’s (2020) research on the introduction of CAV technology to highways appear to match the trends presented by HCM7. Their study concluded that while penetration levels up to 7.5 percent generally increase congestion, the benefits of automated driving are palpable at penetration levels between 20 and 40 percent. Likewise, Ye and Yamamoto (2019) also suggest that increased CAV penetration results in consistent travel speeds and smoother vehicle travel, as well as an increase in time-to-collision (i.e., the time necessary for a collision to occur if no intervention takes place) metrics. Finally, Maurer et al. (2015) proposed alternative headway times of 0.3 to 0.5 seconds (required reaction time of an ADS) for CAVs and 2 seconds for human drivers (legal recommendation).

Segregating CAV traffic from other vehicles is a prospective solution that could offset the congestion caused by CAVs at lower penetration rates, since these vehicles can operate at a higher density than conventional traffic. Ye and Yamamoto (2018) determined that at low CAV penetration rates, dedicated CAV lanes will reduce roadways’ flow rates if the speed limit for these lanes is the same as for the “conventional” traffic lanes. However, implementing dedicated CAV lanes on higher-density roads (>30 vehicles per mile per lane) with increased speed limits within those lanes does improve throughput for penetrations beyond 20 percent, while modest benefits can be also observed on more congested roads (>45 vehicles per mile per lane) starting at 10 percent CAV penetration.

Source: HCM7 (2022)

Note: vh/h/ln = vehicles per hour per lane.

Adapting Airport Curbsides for CAVs

As ADS technology is enhanced to reach higher levels of automation and the CAV share of the U.S. roadway fleet increases, airports will become stakeholders in the integration process. Specifically, airports tend to own (or at least operate) their curbside roadways and part of the access roads leading to and from them. These infrastructure owner-operators (IOOs) will be responsible for mapping their roadways, passenger drop-off and pick-up areas, and staging facilities into CAV geographical databases to facilitate an orderly integration of these vehicles into the airport traffic mix. More importantly, airports will need to ensure that their roadway data are current and reflective of medium- and long-term disruptions, such as construction work. At the same time, airport signage must be updated to improve compatibility with CAVs, such as applying uniform markings within roadways and increasing lighted signs’ refresh rates above 200 hertz to improve readability by CAV’s detection systems (Gopalakrishna et al. 2021).

CAV implementation is not expected to substantially alleviate concerns that airport operators might have about curbside congestion. While CAVs are expected to operate in a manner that can reduce the incidence of traffic accidents within airport curbsides, and thus can improve safety in the airport environment, the most significant improvements in traffic flow through CAV adoption are expected in high-speed (i.e., highway and freeway) environments. On the contrary, substantial adoption of Levels 4 and 5 (driverless) CAVs might instead increase congestion, as travelers might prefer to be dropped off or picked up curbside by a CAV over other ground access modes (e.g., transit, conventional vehicle drop-off, or park-and-fly).

The introduction of CAVs as a mode for ground access to airports would significantly impact how airports plan and monetize their curbside facilities. Since CAVs with Level 4 and higher ADS do not require drivers, they can drive themselves to the airport to drop off or pick up travelers and immediately return home or go to their next destination. These vehicles no longer need to dwell at airport parking lots, depriving airports of a valuable revenue source—valued at 19 percent of all airport revenue in 2018 (Piacenza 2018). Wang and Zhang’s (2019) study projected that at Tampa International Airport (TPA)—which has an underdeveloped transit network but a highly developed highway network—parking revenues would start to sharply decrease as the market penetration of CAVs reaches 10 percent, with a loss of over 75 percent of parking revenue at a 60 percent penetration rate. The framework that airports have developed to mitigate the effects of curbside congestion and the loss in parking revenues caused by transportation network company (TNC) operations—additional curbside drop-off and pick-up lanes for TNC use and the addition of an airport surcharge—can be extended to future CAV operations as well, especially since TNCs are likely to be among the first users of commercial CAV technology. Parking lots at airports—especially those nearest to the curbside—should be redesigned to accommodate CAVs through the creation of additional pick-up and drop-off lanes (at the expense of a portion of the parking areas), “minute” parking lots for short dwell times, or both lanes and lots (Kaltenbronn et al. 2019). Staging areas that have been put in place for TNC drivers to wait between rides should be expanded to match the increased affluence of CAV traffic.

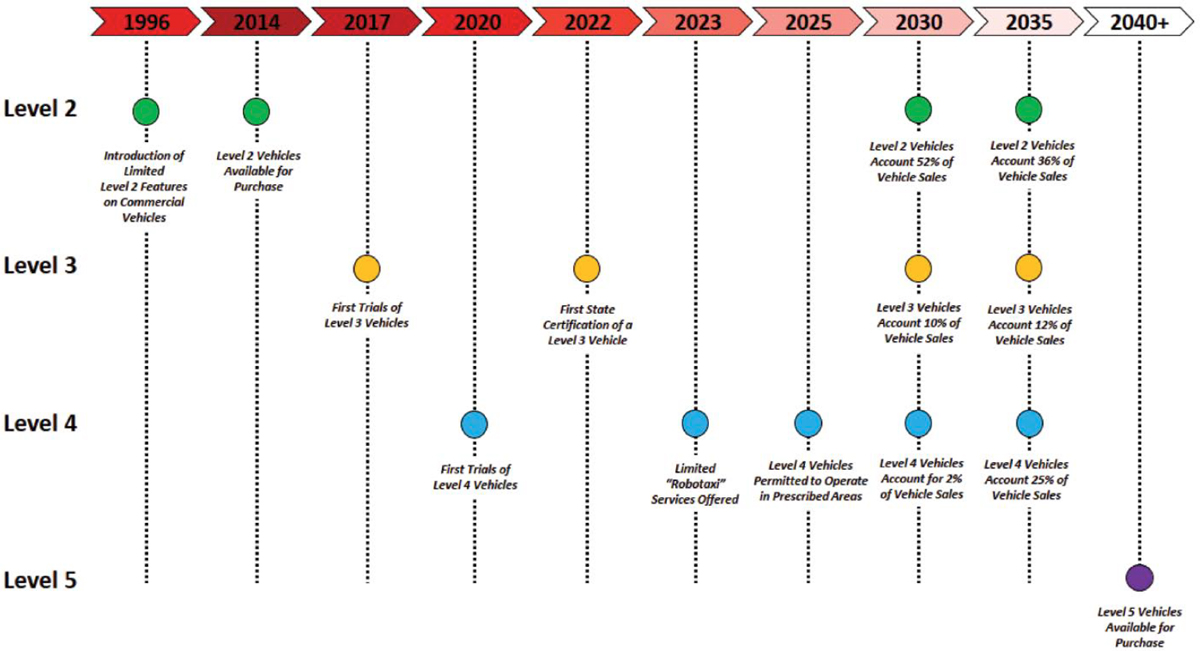

Timeline and Penetration Scenarios

Widespread implementation of CAVs depends on two aspects: affordability and desirability. Initial CAVs will be released in a market with little competition, limited supply chains, and manufacturers seeking a return on their research and development investments, leading to price premiums. These increased prices also extend to higher insurance premiums, due to both the increased value of the CAV and the complexity of maintenance and repair work. However, between 2030 and 2040, massification of CAV production should ultimately lower the costs of

ownership and operation below traditional vehicles per economy-of-scale principles (Intelligent Transportation Systems Joint Program Office 2018). Affordability thus becomes a challenge to the introduction of CAVs, especially considering that over 55 percent of respondents in a study by Bansal and Kockelman (2017) showed zero willingness to pay for Level 3 or 4 CAVs.

Roadblocks to the desirability of CAVs can also be identified from concerned responses to potential issues with CAVs. Polling conducted by Schoettle and Sivak (2014) found that over 75 percent of U.S. respondents were moderately or very concerned with the safety implications of component failure, the question of legal liability in case of an accident, and riding in vehicles without driver controls. When gauging Americans’ sentiment toward safety, privacy, and data security, Lee and Hess (2022) found disparities along ethnic, political, and gender lines. They found that women and ethnic minorities exhibit increased caution regarding safety; Hispanic Americans are more likely to be concerned about privacy; and non-white respondents are apprehensive about the data security implications of using a CAV. At the same time, politically conservative respondents are also wary of privacy and security issues, especially concerning the government’s access to driver and vehicle data. Bansal and Kockelman’s (2017) polling results showed that 58.4 percent of respondents are afraid of CAVs, and only 40 percent of respondents would be willing to use CAVs on an everyday basis.

Successful CAV adoption is dependent on the resolution of factors on the supply side (e.g., mass production, competition, technological availability, regulatory approval, and post-purchase support network) and the demand side (e.g., low willingness to pay, premium pricing, consumer concerns about CAVs); the large number of factors makes estimating CAV adoption in the long term challenging. Bansal and Kockelman (2017) combine the results from their polling with previous estimations on CAV adoption to suggest that nearly 25 percent of the U.S. light vehicle fleet would be at least Level 4 by 2045 if vehicle prices drop 5 percent each year and consumer willingness to pay remains unchanged. An optimistic scenario that includes a 10 percent annual price drop and a 10 percent increase in consumers’ willingness to pay could result in an 87 percent share of Level 4 CAVs on U.S. roads.

Figure 45 provides a potential timeline for the development and rollout of CAV technologies based on SAE levels of driving automation.

Standards and Policies

As with other novel technologies, efforts to regulate CAV systems’ design and operation are ongoing. SAE International has been one of the leading developers of standards for CAVs. SAE’s publication R-489, Fundamentals of Connected and Automated Vehicles (Wishart et al. 2022), is their flagship publication on the subject, summarizing the design objectives and requirements for different components of CAV systems as well as testing policies to convince regulators, drivers, and the public of these systems’ safety and advantages over conventional vehicles. Some of SAE’s standards, such as the levels of automation for CAVs, have been incorporated in regulation in the United States and worldwide.

All CAVs are motor vehicles and thus must comply with NHTSA’s Federal Motor Vehicle Safety Standards. ADS are not subject to binding regulation at the federal level; during the 115th Congress (2017–18), two bills were introduced in the House of Representatives and the Senate to regulate CAVs: H.R. 3388 (SELF DRIVE Act) and S. 1885 (AV START Act). Neither of these bills made it out of committee. U.S. DOT and NHTSA have nonetheless published guidance and policies for use by the states, including the federal AV policy (September 2016), Automated Driving Systems 2.0: A Vision for Safety (U.S. DOT/NHTSA 2017), and Preparing for the Future of Transportation: Automated Vehicles 3.0 (U.S. DOT/NHTSA 2018); the latter expands these policies to include other on-road systems.

Source: NHTSA (2021); McKinsey (2023)

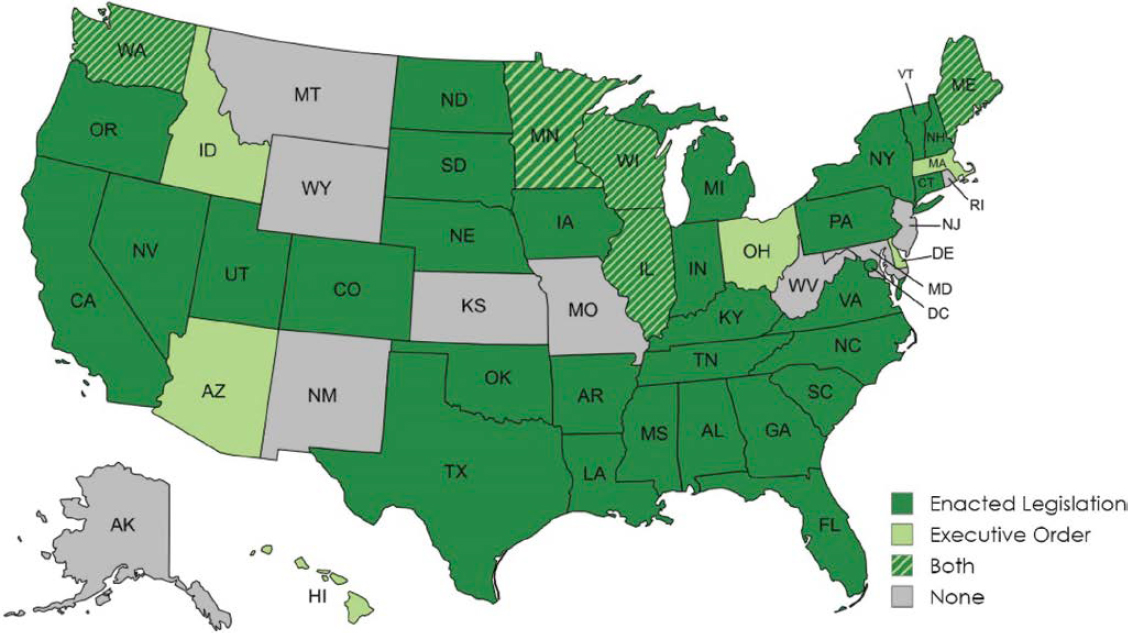

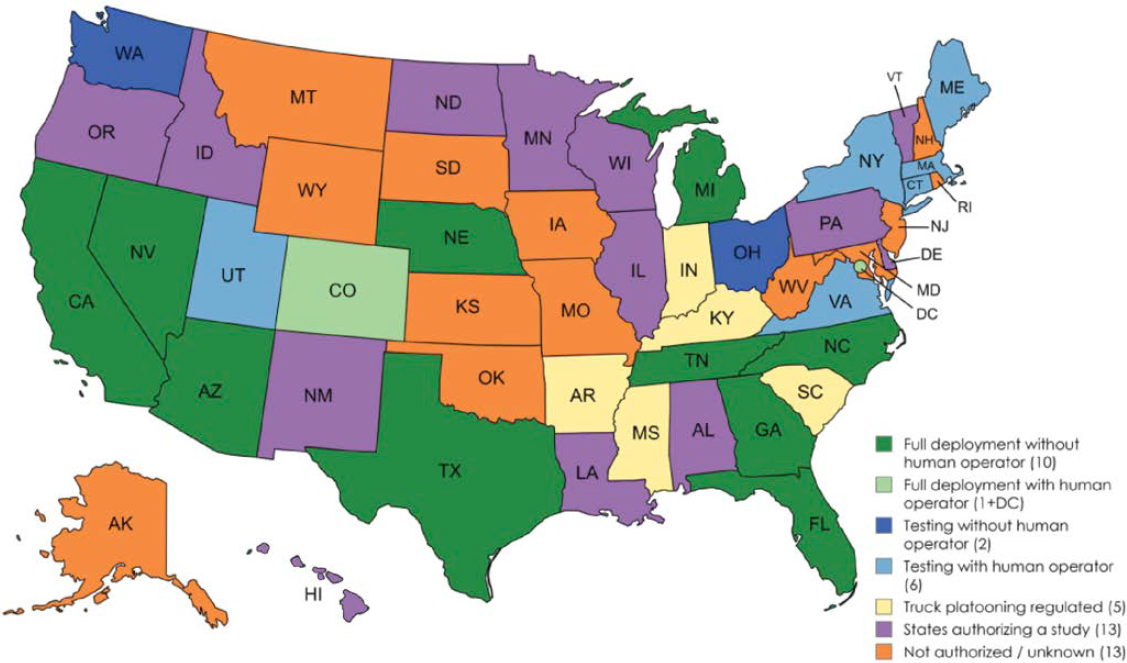

At the state level, governors’ offices, departments of transportation, and legislatures have enacted mandatory standards for CAVs within their jurisdiction. A report by the National Conference of State Legislatures (2020) on AV legislation recorded that 40 states and the District of Columbia have enacted legislation or issued executive orders—or have done both—concerning AVs, as depicted in Figure 46. As of 2018, 10 of these states allow full deployment of AVs without a human operator (Levels 4 and 5), while Colorado and the District of Columbia require a human operator for full deployment (Level 3), as shown in Figure 47.

Legal and regulatory guidelines focus on bridging the gap between conventional vehicles and AVs. NHTSA published a final rule in 2022 amending the Federal Motor Vehicle Safety Standards concerning occupant protection to include cars with neither human drivers nor steering wheels (National Highway Traffic Safety Administration 2022b), while emphasizing that these vehicles must provide the same level of safety as their conventional counterparts. Since Level 3 AVs will significantly alter vehicle-driver interactions, driver education programs must be adjusted to include the role of drivers as supervisors and how to respond when the ADS disengages itself. Liability questions in case of accidents, collisions, or traffic infractions remain: Are the vehicle and its manufacturer fully liable, or is the user considered liable by providing consent as a condition of automated vehicle use (Pattinson et al. 2020)? Finally, in the interconnected environment where CAVs operate, tracking a vehicle’s movement data—and by extension, its driver and passenger location information—is a possibility, which could raise data privacy concerns. These regulatory questions align strongly with the concerns expressed by Americans about CAVs in the Schoettle and Sivak (2014) and Lee and Hess (2022) studies.

At the state level, there may be efforts to regulate specific components of CAV operation, such as traffic enforcement, insurance, registration, and licensing. CAV technologies that enable driving automation Level 3 and above are still largely emerging. The operations associated with

Source: National Conference of State Legislatures (2020)

Source: Governors Highway Safety Association (2018), adapted by WSP

CAVs, the behavior of these vehicles in complex situations, and the driving rules they will follow are still a work in progress, as some of the incidents observed during operational trials have shown. Delivering advanced CAV technologies to the public will require collaborative work across stakeholders to adopt minimum standards that ensure interoperability and to develop the digital infrastructure required for these systems to dialogue. An example of common framework is U.S. DOT’s Architecture Reference for Cooperative and Intelligent Transportation, which is a vehicle-centric reference architecture serving as a common basis for planning, defining, and integrating intelligent transportation systems.