Enhancing Airport Access with Emerging Mobility (2025)

Chapter: 8 Facility Requirements

CHAPTER 8

Facility Requirements

Purpose

This chapter provides an overview of the facility requirements associated with the integration of each mode or group of modes at aviation facilities. It does not pretend to be a “go-to manual” for the planning and design of non-aviation transportation infrastructure, but rather it is a resource to understand the overall requirements for strategic decision-making, programming, and coordination purposes. Resource documents for planning and design purposes are referenced throughout the chapters. Additional references can be found in the searchable electronic library of the companion toolkit of the report, which is available on the National Academies Press website (nap.nationalacademies.org) by searching for ACRP Research Report 269: Enhancing Airport Access with Emerging Mobility.

Micromobility

Overall Requirements

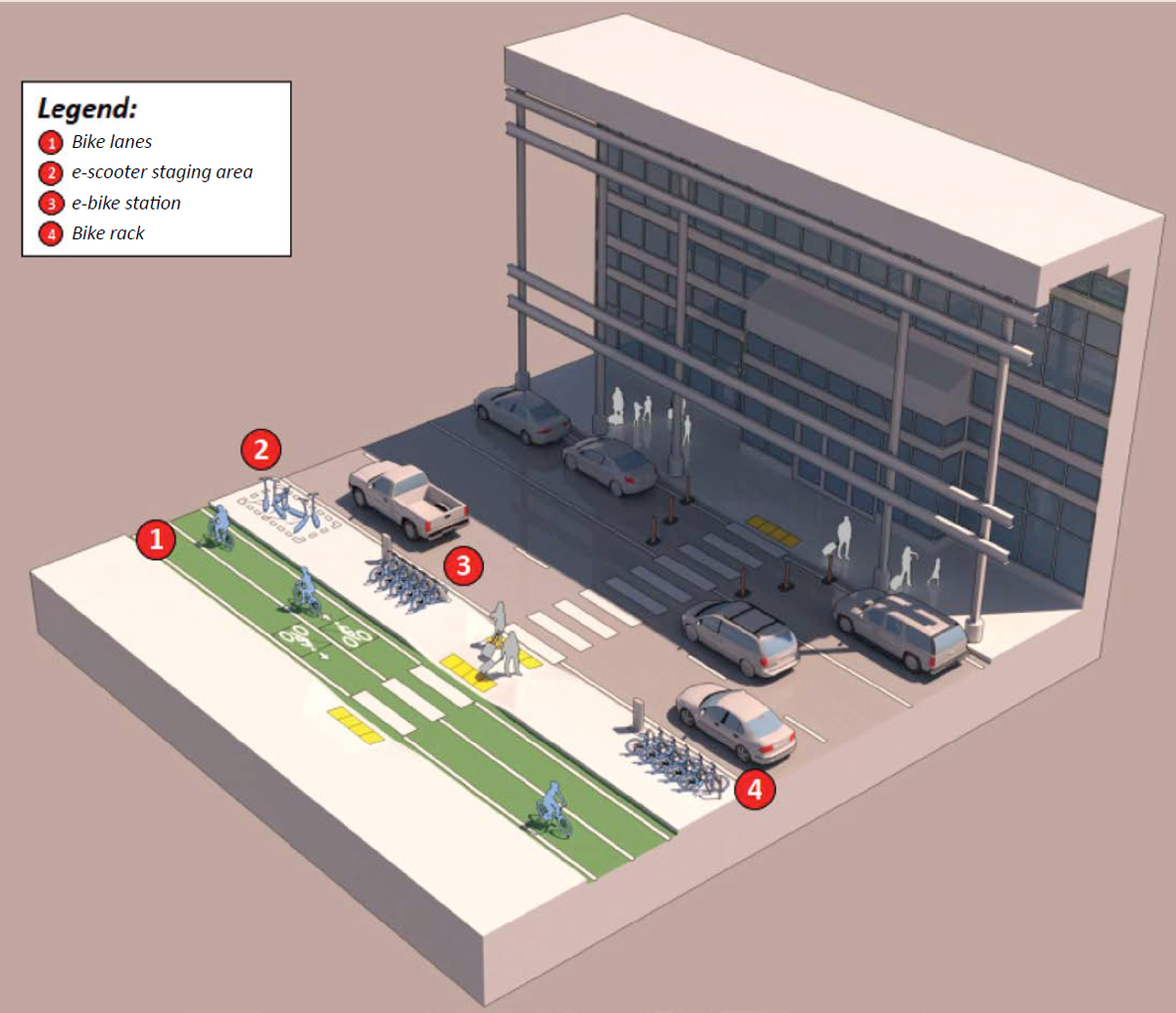

Figure 54 depicts the main infrastructure for micromobility. Micromobility facilities are generally divided into two types: on-street and off-street. Facilities may be shared with other users, such as lanes shared between bicyclists and motorized traffic or pathways shared between bicyclists and pedestrians.

- On-street bicycle facilities are defined as facilities where users travel on roadways with motorized traffic, either by sharing a travel lane with motor vehicles or by having dedicated on-street bike lanes, paved roadway shoulders, or bike lanes separated from motorized vehicles by a painted island buffer. Factors to consider when designing for on-street micromobility facilities include safety, traffic volumes and speeds, presence of on-street parking, frequency of right-turning vehicles, and the degree to which bicyclists are separated from motor vehicle traffic. When bicycle traffic shares the same facilities as motor vehicles, the flow and speed of bicyclists can be significantly impacted because they must maneuver through constrained space and often wait behind queues of vehicles, which limits the ability to travel at free-flow speeds.

- Off-street bicycle facilities are facilities that may be located parallel to roadways or completely independent from the roadway network, such as recreational trails. These facilities may include pathways for the exclusive use of bicyclists or pathways shared with pedestrians. Factors to consider when designing for off-street micromobility facilities include the presence of opportunities for passing maneuvers, frequency of crossing pedestrians, and presence of intersections along the path.

Key Design Features

In planning for micromobility vehicle–space requirements, there are various elements that constitute the operational footprint. The design of safe and efficient micromobility infrastructure is essential to ensure that users are comfortable enough to commute via micromobility services and for micromobility to succeed as a viable transportation mode (National Association of City Transportation Officials 2019a). This requires an encompassing design of various elements, including designated lanes, cycle tracks, intersection treatments, signals and wayfinding signs, pavement markings and parking, and storage and docking space. The National Association of City Transportation Officials (NACTO) has published several guidelines for designing and implementing micromobility, including Urban Bikeway Design Guide and Bike Share Station Guide.

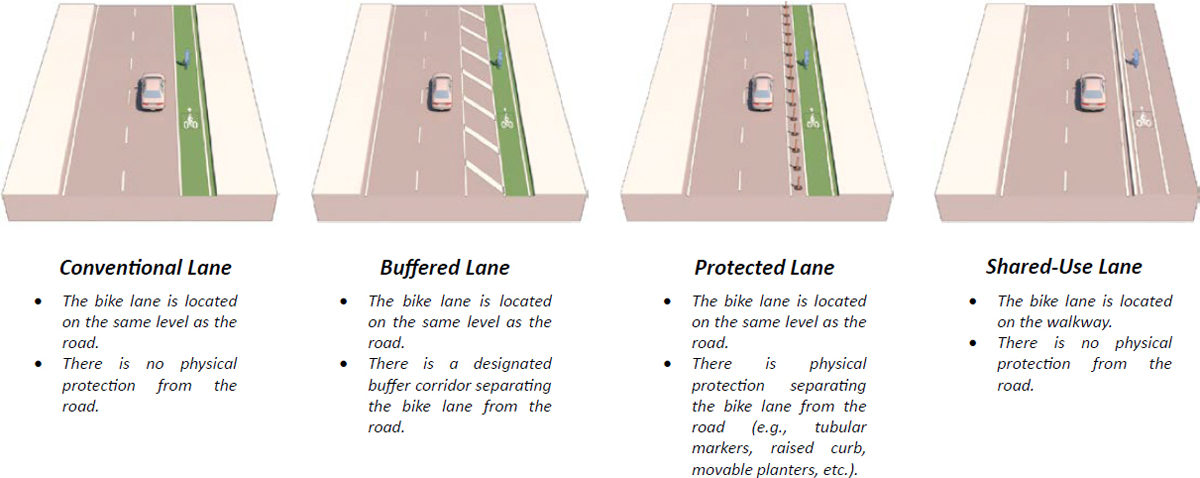

Bike lanes are defined as a section of the roadway designated by pavement marking and signage to indicate preferential or exclusive use for bicyclists or other forms of micromobility vehicles. Bike lane width typically ranges between 4 and 6 feet. The Highway Capacity Manual: A Guide for Multimodal Mobility Analysis, 7th Edition (HCM7) (2022) recommends a standard width for an effective bicycle lane of 3.5 to 4 feet. In the case of off-street bicycle pathways, AASHTO recommends a width of 10 feet; this allows users to travel at the maximum allowable speed without mixing with motorized traffic. Typically, bike lanes run near the curb and adjacent to parked cars in the same direction of traffic, but they may be designed for the contraflow direction in the case of low-volume traffic segments.

In the case where a physical barrier, such as a median or raised curb, is provided to eliminate encroachment of motorized traffic and provide more safety, these are referred to as cycle tracks. Robert Schneider from the University of Wisconsin–Milwaukee recommends having designated lanes for micromobility vehicles starting within a mile from the designated parking facility at the airport, with well-communicated wayfinding signs to help guide users in advance of the traveled path. These signs increase their comfort level with using this mode of transportation and promote compliance with regulated operations at the airport. Figure 55 depicts the four main bike lane configurations.

Capacity

According to HCM7, the capacity of a bicycle facility depends on the number of effective lanes used by bicycles. Shared-lane facilities typically consist of one effective lane, while designated bicycle lanes, shoulder bikeways, and cycle tracks may include more than one effective lane (based on lane width), and therefore, they can provide greater capacity. Furthermore, a greater number of effective lanes at bicycle facilities provides a higher level of service (LOS) since it offers more opportunities for passing and maneuvering around other users (bicyclists and pedestrians).

In designing for bicycle lanes, HCM7 also recommends a saturation flow rate of 2,000 bicycles per hour per lane for a one-direction bicycle lane under interrupted-flow conditions, equivalent to 1,000 bicycles per hour per lane when the bicycle lane receives a green signal during 50 percent of the signal cycle at signalized intersections.

Parking Footprint

Parking facilities and vehicle storage to accommodate parked or docked vehicles are among the main challenges faced when planning for shared micromobility, and they are an important aspect of the footprint of these vehicles. There are two main types of shared micromobility: station-based and dockless systems. The former dictates the assigned station locations where users can start or end their trip, while the latter allows users to start or end their trip almost anywhere. In practice, some cities allow shared micromobility operators, using public rights-of-way, to leave the vehicles in in-street corrals or designated parking zones in highly congested areas or in designated zones of sidewalks. Designating the drop-off location provides more control over the start and end of these vehicles’ usage and reduces encroachment on the public right-of-way. However, if vehicles are parked on the sidewalk, it is important to ensure that they do not impede the movement of people walking on the sidewalk and that they are compliant with ADA requirements.

In Santa Monica, California, where one of the largest e-scooter operators started, staging areas for shared e-scooters were created by utilizing a curb bulb-out space at a mid-block crosswalk, as seen in Figure 56 (Transportation for America 2020).

A key difference between parking requirements for private and shared use is that for private micromobility vehicles, storage space needs to be provided for passengers using their own bikes or e-scooters to get to the airport and storing their micromobility vehicles for the duration of their trip. In contrast, shared micromobility vehicles may require docking space for users to drop off or pick up their vehicle, or users may need designated zones at the airport to park their micromobility vehicles for other users to pick up. Furthermore, regular bicycles require more space than foldable and compact bicycles or e-scooters. Nonetheless, shared micromobility has greater flexibility with space needs since micromobility vehicles occupy less space than motorized vehicles.

Integration at Airports

Micromobility (e.g., bikes and e-scooters) can be integrated into airport ground access, especially at downtown airports and with the emergence of additional urban airports that can be incorporated into advanced air mobility (AAM) networks. Driven by the need to reduce curb congestion and vehicle-related emissions, especially at congested airports, operators may be considering methods to increase multimodal transportation at their airports. However, when designing for micromobility access at airports, many factors come into play. The layout and location of the airport can be a physical barrier if it is located in a remote area, and the absence

of multimodal connectivity to transit can also become a challenge for commuting over large segments. In many cases, the traveling public may be weighed down with luggage that prevents them from using micromobility vehicles.

A study by Orrick and Frick (2012) presented several case studies of airport operators that have incorporated employee bicycle access into their airport ground access in an effort to reduce single-occupancy vehicle travel at the airport. The following is a summary of various micromobility facilities among the airports studied:

- Portland International Airport (PDX): trail access through a multiuse path, bicycle racks, secure parking for passengers and employees, in-terminal assembly station for passengers’ boxed bikes, and conventional bicycle parking.

- San Francisco Bay Oakland International Airport (OAK): trail access, bicycle parking, and a bicycle lane constructed on the airport access road by eliminating a traffic lane in each direction.

- Los Angeles International Airport (LAX): bicycle lane on a service road, providing a connection to recreational bicycle paths; bicycle lockers heavily used by airport employees; and showers and a changing area.

- San Francisco International Airport (SFO): trail access, a bicycle lane on a service road that was constructed by replacing vehicle lanes with bike lanes, and bicycle parking.

Several factors contribute to the cycling quality of service, including the volume and speed of adjacent vehicles sharing the same facilities, presence of on-street parking, pavement quality and the frequency of street sweeping, inclement weather, and snow clearing in the case of heavy snow events. These factors, among others, contribute to the safety of using micromobility facilities and can impact the variation of trip demand. Users of micromobility vehicles are more exposed to weather elements—Nosal and Miranda-Moreno (2014) found that precipitation events have a significant negative impact on cycling flows.

In planning for micromobility integration at airports, it is important to consider all the applicable planning and land use requirements based on the owner and operator of the airport, such as state, city, or county planning requirements. In addition, when planning for future facilities, planners can use forms of public outreach, such as surveys or open houses, to better understand the needs of users and commuters. If existing facilities already exist, planners should consider using public surveys to evaluate user satisfaction with existing facilities and assess any enforcement or safety issues encountered to improve these facilities.

In addition, FHWA published a guide for local and state agencies to promote and support the development of safe and complete pedestrian and bicycle networks. The document features guidance and best practices on policies and practical implementation (Louch et al. 2016). In addition, BTSCRP Research Results Digest 1: E-Scooter Safety: Issues and Solutions provides important lessons learned on e-scooter safety management practices (Sandt et al. 2022).

Personal Rapid Transit

Overview

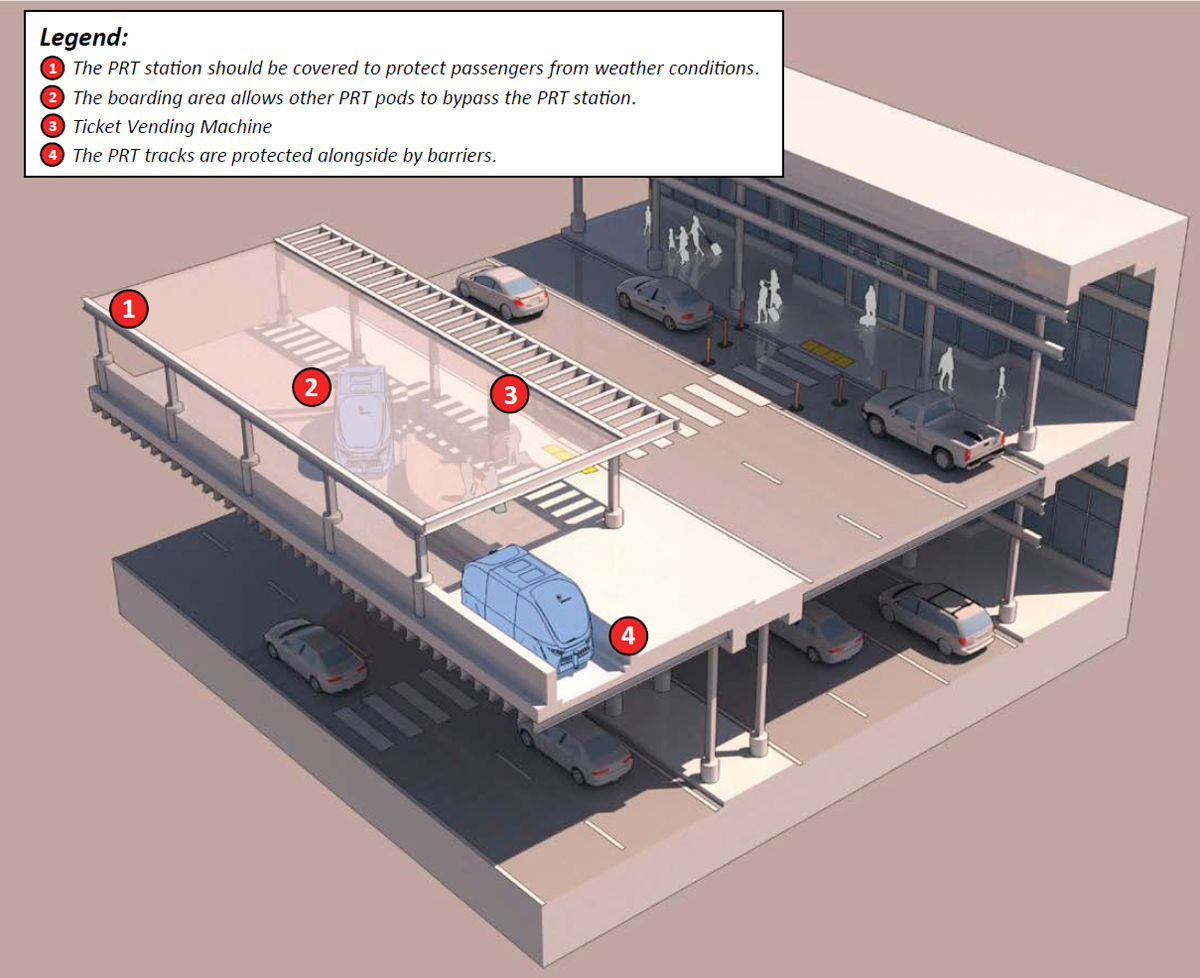

Personal rapid transit (PRT) is a type of guided transportation system made of guideways and “pods” that provides on-demand, point-to-point connections (Figure 57). While similarities exist between PRT and automated people movers (APMs)—defined as “a guided transit mode with fully automated operation, featuring vehicles that operate on guideways with exclusive right of way” (American Society of Civil Engineers 2002)—APMs are more widely used for passenger conveyance and transfers, such as circulation between terminals and access to parking garages,

ground transportation centers (GTCs), and consolidated rental car (CONRAC) facilities. This project focuses on airport ground access and draws on similarities between the two modes to discuss existing standards and facility requirements.

A set of standards does not currently exist for PRT system specifications; however, since PRT is considered a type of Automated Transit Network, standards for PRT systems are deferred to ASCE’s APM standards. These standards establish the minimum set of requirements necessary to achieve an acceptable level of safety and performance for APM systems.

ASCE Standard 21 includes minimum requirements for the design, construction, operation, and maintenance of APM systems.

The main infrastructure components of PRT systems include

- Guideways: can be elevated, at-grade, or below-grade and can be built for two-way operations in case of high demand.

- Vehicles: driverless electrically powered vehicles with onboard batteries or wayside third rails that can carry up to 8 passengers per vehicle, or up to 24 passengers per vehicle in the case of group rapid transit (GRT).

- Stations: located offline and on sidings. The number of vehicle positions determines the capacity of the system and the configuration of the station itself.

FAA’s AC 150/5360-13A: Airport Terminal Planning (2018) includes key factors to consider when planning APM systems. Although these factors focus mostly on intra-airport ground mobility for transportation between a landside terminal building and airside concourses (post-security) or between a terminal building and a parking structure (pre-security), many of these factors can apply when exploring APM or PRT systems for airport ground access. These factors include

- The capacity of each car to account for large pieces of baggage per person accessing the airport.

- Peak-hour loads on the busiest guideway segment or station-to-station link. The number of required pods (and train size) depends on the peak load, vehicle capacity, and desired headways.

- Guideway geometry and alignment, which is established by the type of APM system (e.g., rubber tire or steel wheel systems).

- Station design that allows for separation of boarding and alighting passengers; space for waiting passengers; and escalators and elevators, which are frequently needed to connect to elevated or underground stations.

- Vehicle maintenance and storage yards, which are often located at the end of the line.

Vehicles

The vehicle passenger design capacity is defined by the number of people based on a preferred standard of comfort. The total passenger area is equivalent to the entire area available to seated and standing passengers in the vehicle, with a standing floor area equal to the total passenger area less 4.5 square feet for each nonremovable seat position.

Station Clearance

Slow-speed people movers are defined as vehicles traveling no more than 20 miles per hour (mph) at any location on their route during normal operation.

For slow-speed people movers, the horizontal gap between the station’s platform and the vehicle door when the doors are open for boarding shall be no greater than 1 inch, and the height of the vehicle floor shall be within 0.5 inches of the platform height under all normal static-load conditions. For all other people movers, such as vehicles not covered by the slow-speed definition, the horizontal gap shall not exceed 2 inches and the height of the vehicle should not exceed 0.625 inches of the platform height under all normal static-load conditions.

Footprint and Right-of-Way

PRT systems are similar to horizontal elevators, and they operate on exclusive guideways, separated from other traffic and pedestrians. Guideways can be arranged linearly, in interconnected loops, or in a network setting with all stations being offline on sidings with spaced merge and diverge points (Robinson et al. 2011). This layout allows PRT systems to operate nonstop and offer point-to-point service.

The footprint for PRT systems is significantly less than the footprint needed for light rail transit (LRT), bus rapid transit (BRT), and APM systems. For example, an APM has columns that are typically 6 to 9 feet in diameter, while the Ultra’s PRT columns are 20 inches in diameter, similar to light poles.

Connected and Automated Vehicles

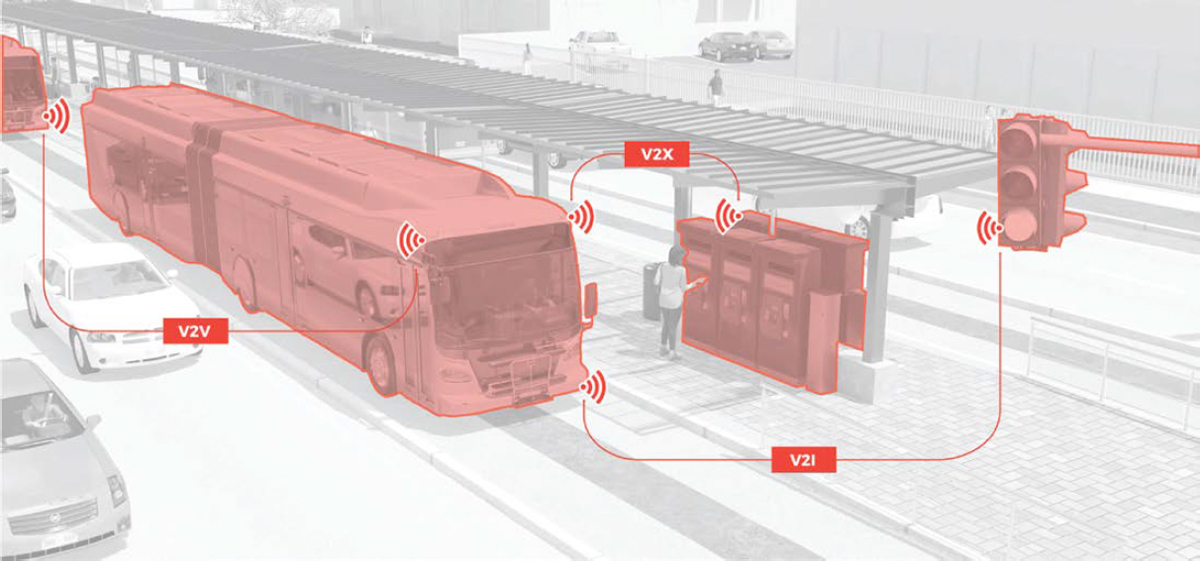

Roadway Requirements for Connected and Automated Vehicles

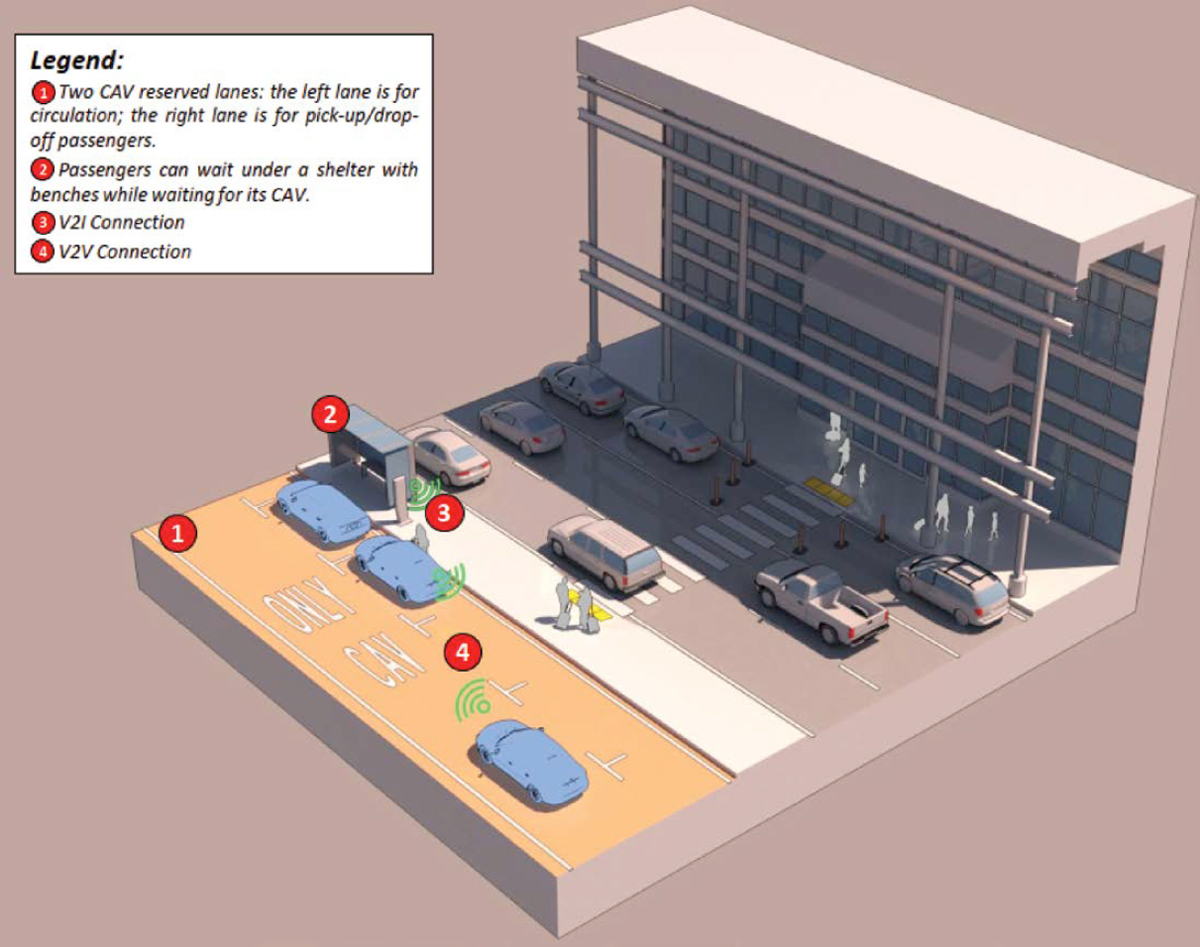

The existing road and highway infrastructure was developed to meet the needs and demands of human-driven cars without automation. As a result, modifications to lane width, road capacity, roadway markers, signage, and signalization may be necessary or opportune to accommodate or optimize roadways for self-driving connected and automated vehicles (CAVs) (Figure 58).

Lane Width and Road Capacity

Vehicle-to-vehicle (V2V) and vehicle-to-infrastructure (V2I) applications will enable smoother traffic by adjusting speeds to optimum levels according to the phase of traffic signals (Dennis et al. 2017). Vehicles will be able to follow other cars more closely while still being safe, improving throughput. Other benefits may include a reduced number of collisions, which now account for

Note: V2I = vehicle-to-infrastructure; V2V = vehicle-to-vehicle.

25 percent of traffic congestion, and possibly further advantages (Federal Highway Administration 2015).

Since CAVs can navigate more congested highway portions using lane-guidance technology without having to alter their speed or distance from other vehicles, lanes designated for only CAVs may not need to be wider to account for human mistakes. If vehicle dimensions essentially remain constant, lane width might be lowered by up to 20 percent to be closer to real vehicle width (Dennis et al. 2017).

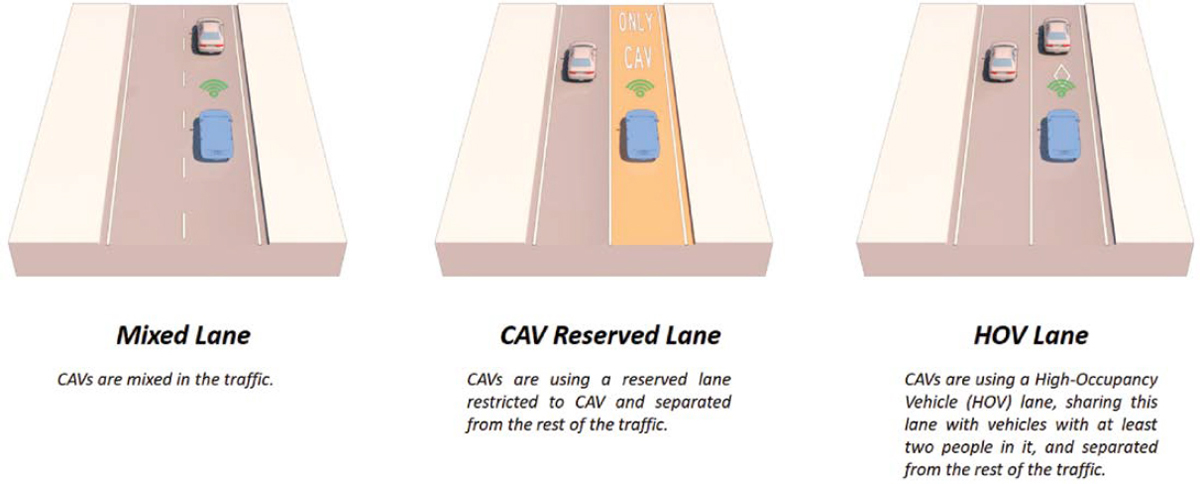

Furthermore, medians on CAV-only roads may be shortened or removed in the long term since there would no longer be a requirement for a safety buffer between traffic in opposing directions. Sidewalks, bike lanes, green space, and other uses for the conserved area might be considered. Figure 59 depicts the main CAV lane configurations.

Road Markings

With the use of machine learning systems, such as radars and cameras, some automated vehicles (AVs) rely significantly on identifying road markers. In order to maximize the effectiveness of lane departure prevention (LDP)—which prevents vehicles from drifting out of their lane—for currently available cars equipped with advanced driver assistance systems (ADAS) or automated driving systems (ADS), three factors for road pavement–marking areas have been identified: uniformity, design, and maintenance (Gopalakrishna et al. 2021).

Uniformity

The lack of pavement-marking uniformity throughout the United States is the most talked about issue from the automated vehicle sector when it comes to the highway infrastructure’s ability to accommodate these vehicles. U.S. highway authorities often follow the national Manual on Uniform Traffic Control Devices (MUTCD), but it is flexible enough to accommodate different approaches. Moreover, the MUTCD falls short in various respects, such as contrast-marking patterns, which can impact the effectiveness of LDP. Recently, the National Committee on Uniform Traffic Control Devices (NCUTCD) accepted certain proposed amendments to the MUTCD that were intended to tighten pavement-marking consistency across the country.

Design

As of June 2019, the NCUTCD CAV Task Force, in conjunction with AASHTO, Auto Alliance, American Traffic Safety Services Association, and the Automotive Safety Council, developed the following pavement-design recommendations that will support CAV technology as well as promote marking uniformity:

- Use 6-inch-wide longitudinal markings on freeways and interstate highways.

- Use 6-inch-wide edge lines on roadways with posted speeds under 40 mph.

- Use dotted edge line extensions along entrance and exit ramps.

- Include chevron markings in gore areas.

- Use continuous markings at the beginning of work zones and in all tapers.

- Eliminate the use of Botts’ dots (i.e., round, nonreflective raised pavement markers) as a substitute for markings.

- Use contrast markings on light-colored pavements.

- Use 15-foot-long lane lines with 25-foot gaps.

- Use only arrow shapes approved in the MUTCD.

Pavement markings must also be visible and identifiable in both dry and rainy situations, as well as during the day and at night. Pavement-marking visibility is typically seen as acceptable when the marking is present, especially under ideal circumstances like clear and dry weather. However, depending on brightness and pavement-marking contrast relative to the concrete surface adjacent to the pavement marking, LDP detection of pavement markings under daylight conditions—dry and wet—can be particularly difficult.

According to FHWA, key factors have been identified that will enhance the visibility of pavement marking. These factors include using markings that are

- Durable,

- High contrast,

- Able to maintain their colorfastness,

- Visible under wet conditions,

- Visible under glare conditions (certain sun angles), and

- Compatible with lidar technologies.

Maintenance

Although the development of minimum retroreflectivity requirements and maintenance for pavement markings in the United States is presently underway, these standards are meant to offer human-driven cars minimal visibility criteria; they are not explicitly made to accommodate ADAS LDP technology or future ADS road-perception technology demands. However, minimum maintenance requirements for pavement markings for LDP detection have been established by the European Union Road Federation. These requirements include

- Maintaining dry retroreflectivity to a minimum level of 150 millicandelas per square meter per lux (mcd/m2/lx),

- Maintaining wet recovery retroreflectivity to a minimum level of 35 mcd/m2/lx, and

- Maintaining contrast to a minimum level of 3:1, with a preferred level of 4:1.

Additional Methods to Keep Vehicles in Lane

Although road markers are essential to CAV operations, using lane markers alone to control automated driving is not a viable strategy (Dennis et al. 2017). Realistically, not all roads will always have lane markers in great condition. Therefore, CAV manufactures are investigating additional methods to keep vehicles in their lanes—such as placement in relation to vehicles, guardrails, and other objects with information from a variety of sensors and 3D maps—in order to develop a self-driving car capable of operating on any road at any time. Improving road

markings may be helpful to promote early adoption and increase the potential safety advantages of these vehicles.

An NCHRP research project is investigating pavement-marking performance parameters that may impact how well machine learning systems can read them (Pike et al. 2017). The findings from this study may help key stakeholders, including transportation officials, professional associations, members of the automobile industry, and owners and operators of infrastructure, to define the standards and rules for road markings.

Finally, NCHRP Research Report 891 (Booz Allen Hamilton et al. 2018) suggests that separation devices are not warranted between dedicated highway lanes shared with high-occupancy vehicles (HOVs) and general purpose lanes. However, separators should be considered with CAV-reserved lanes if the market penetration rate of these vehicles is low. While separation devices are not required under high market penetration rates, buffer-separated double solid lines may provide additional safety. This advice is based on an analysis using lane friction (difference of average speed) between the dedicated lanes and general purpose lanes as the performance measure.

Signage and Signalization

The functions of road signs and signals may be replaced with V2I communication and high-definition 3D mapping (Dennis et al. 2017). Vehicles may receive road indicators via cellular communication or dedicated short-range communications (DSRC). However, as signs and signals are still necessary for humans-driven cars, bicycles, and pedestrians, discarding them will not be a feasible option during initial stages. To support V2I applications, traffic signs may also need to be modified.

These applications could facilitate faster intersection crossing and better traffic flow, hence minimizing needless braking and accelerating. Another factor to consider for CAVs and signs are work zones on the road. Construction workers might use wireless beacons that send AVs instructions from a predefined list to reduce the likelihood of errors (Dennis et al. 2017). NCHRP Research Report 1051: Preparing Transportation Agencies for Connected and Automated Vehicles in Work Zones (Neurauter et al. 2023) provides further information on the expected impacts of CAV technologies on work zone environments. It features guidelines that prepare transportation agencies to support and expedite the implementation of these technologies in work zones.

Electric Charging Infrastructure

All-electric and plug-in hybrid vehicles use charging stations, called electric vehicle supply equipment (EVSE), to replenish their batteries’ power. EVSE can be available to the public or for private use (i.e., home charger), and these ports are not all created equal: Level 1 EVSE provides about 5 miles of range per hour of charge at 120V, while Level 2 EVSE uses 240V to replenish 25 miles of range in an hour. Recent EVSE also supports direct current or “fast” charging at 480V or greater, which can deliver more than 200 miles of range in 30 minutes; however, the connector technology offered at an EVSE port (Combined Charging System, CHAdeMO, or North American Charging Standard) might not be compatible with some battery-electric vehicles (BEVs) or plug-in hybrid-electric vehicles (PHEVs). Due to the substantially faster charge times, the share of public direct current “fast” chargers is steadily increasing, from 16.7 percent in Q4 2019 to 20.1 percent in Q2 2022 (Brown et al. 2022). While driving, electric vehicle range can be extended by up to 10 percent through regenerative braking, which transforms excess kinetic energy into electric energy that can charge the EV’s batteries (Chau 2014).

Electric vehicles will also challenge the energy grid locally in the midst of a general increase in electricity demand with the “electrification of everything.” While this warrants new investments in infrastructure for electricity production and distribution, demand vs. supply tensions might appear in the meantime. In the summers of 2021 and 2022, the California Independent System Operator—which oversees the operation of California’s bulk electric power system, transmission lines, and electricity market—issued a voluntary alert advising California residents to conserve energy to “help balance supply and demand” on the power grid during an extreme heatwave event (California Independent System Operator 2023). Unplugging electric vehicles during peak usage times was one measure among various recommended power-saving actions. In November 2022, the Swiss Federal Council issued a notice for proposed rulemaking proposing a federal power-saving plan in case of a national electricity shortage—in the context of the Russian aggression against Ukraine (Federal Council of Switzerland 2022). Stage 3 of the plan restricts utilization of private (i.e., personal) electric vehicles to trips that are absolutely necessary, such as professional obligations, groceries and medical appointments, religious attendance, and court orders. According to the impact assessment joined to the notice, a 6 percent energy savings is expected from all the restrictions on mobility (Département Fédéral de l’Economie, de la Formation et de la Recherche 2022).

Communications and Information Systems

Self-driving CAVs rely on a variety of communication systems to exchange information with other vehicles and infrastructure, as well as cloud-based, power grid, and other relevant connections. Some of the key communication systems used are

- Dedicated short-range communications: This is a wireless communication technology that allows vehicles to exchange information with other vehicles and roadside infrastructure at short ranges.

- Cellular networks: CAVs can also use cellular networks, such as 4G and 5G, to communicate with other vehicles as well as infrastructure. Unlike DSRC, cellular networks have a wider coverage area and can support a higher data rate. However, they are more vulnerable to congestion and signal interference.

- GPS: This is a satellite-based navigation system that provides precise positioning information to vehicles.

These communication systems are critical for the safe and efficient operation of CAVs. They allow vehicles to share information about their speed, location, and intended path, which can help prevent collisions and improve traffic flow. Furthermore, they will be equipped with the necessary firewalls and other security measures to safeguard the security and integrity of data transfer (Wishart et al. 2022).

Vehicle-to-Infrastructure

V2I refers to the communication between vehicles and fixed infrastructure, such as traffic signals, road signs, and weather sensors. V2I communication devices collect data generated by moving vehicles and wirelessly transmit alerts on environmental, mobility, and safety issues to the vehicle. State and local government organizations will likely build V2I infrastructure next to or integrated with current intelligent transportation system (ITS) equipment. ITS is a set of advanced technologies and systems that are used to improve the safety, efficiency, and sustainability of transportation. ITS equipment consists of

- Roadside units: These are devices installed along roads to provide communication and positioning services for CAVs. They use technologies such as DSRC and cellular networks to

- provide real-time updates about traffic conditions, road closures, and other relevant information to vehicles. As stated by the Federal Transit Administration (2015), according to FHWA, the unit communicates information such as

- – Red Light Violation Warning,

- – Stop Sign Gap Assist,

- – Reduced Speed/Work Zone Warning,

- – Curve Speed Warning,

- – Spot Weather Impact Warning, and

- – Pedestrian in Signalized Crosswalk Warning (Transit).

Roadside units (RSUs) can also be used to support the deployment of advanced traffic management systems, such as cooperative adaptive cruise control and platooning, which can help improve traffic flow and safety on the road.

- Traffic signal controllers: These are devices that communicate with vehicles and adjust the timing of traffic signals by generating the signal phase and timing message (green, yellow, red, and the amount of time left until the next phase) to the vehicles or RSUs.

- Traffic management center: These are facilities that use information from RSUs and other sources to monitor traffic conditions and optimize traffic flow.

Bus and BRT Systems

Overview

Both conventional bus and BRT systems are among the easiest mass transit systems to implement, since they can make use of existing roadways to operate. Conventional bus systems are associated with minimal necessary infrastructure (e.g., depots and bus stops), onboard fare collection, and nonexclusive operations along existing traffic lanes. BRT has adapted some of the features of LRT systems to improve service quality and average speed, such as using semi-exclusive or exclusive rights-of-way, larger stations with more amenities, off-board fare collection, and traffic signal priority (Federal Transit Administration 2015). This section presents facility requirements for both ground access modes while also highlighting mode-specific requirements.

Running Ways

A key distinction between conventional bus systems and BRT is that running ways for BRT tend to separate its services from other ground transportation methods, thus increasing the system’s speed and throughput. These running ways can provide exclusive (Class I), semi-exclusive (Classes II–IV), and nonexclusive (Class V) rights-of-way, but running ways do not need to be of the same class system-wide. Since BRT running ways are designed to provide expedited flow for system buses and are not as affected by traffic congestion as other lanes, their usage can be appealing to non-BRT vehicles. Barriers and monitoring systems should be put in place to prevent the use of BRT facilities by unauthorized vehicles; penalties for misuse of BRT lanes should be high enough to dissuade unauthorized use. However, emergency vehicles should have access to BRT lanes when necessary. There shall be a minimum of two bus lanes (one for stopping and one for passing), each at least 11 feet wide but ideally 13 feet wide.

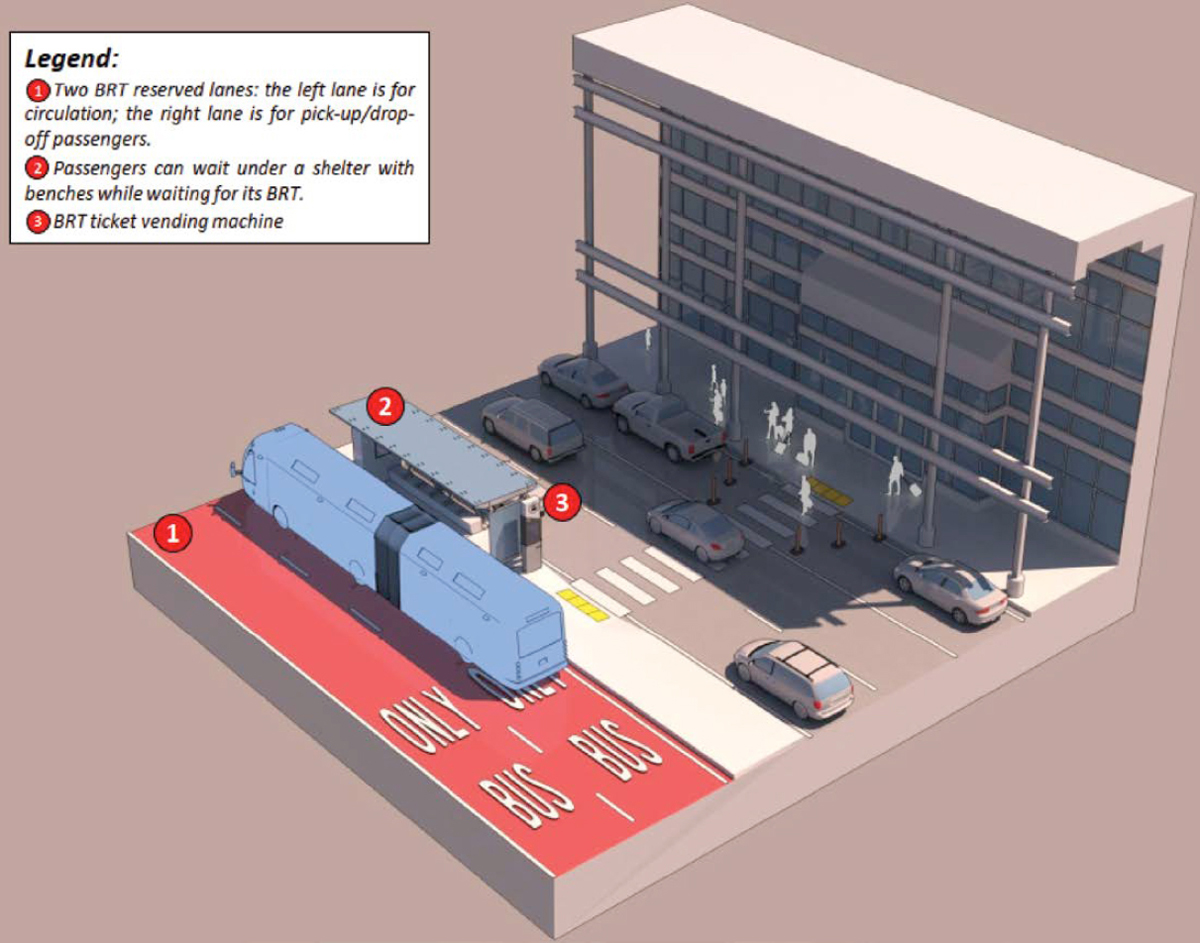

BRT systems are expected to perform better with Class I running ways, but these would require grade-separated infrastructure that would be more expensive to implement and would occupy a larger footprint; transit planners (including at airports) need to consider when and where these running ways would be cost-effective. Off-street, at-grade dedicated busways can also provide good BRT system performance. Off-street busways, if designed with sufficient corridor width, can be transformed into LRT rights-of-way should ridership demand require it. Introducing this kind of running way at airports as means of ground access would require additional roadways to separate BRT operations from other ground vehicles (Figure 60).

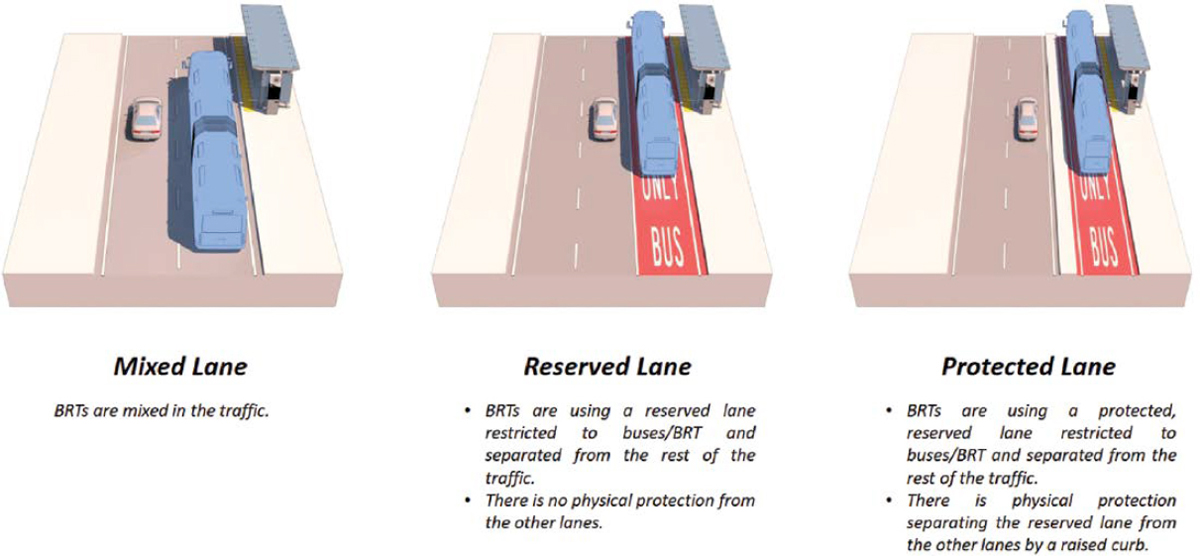

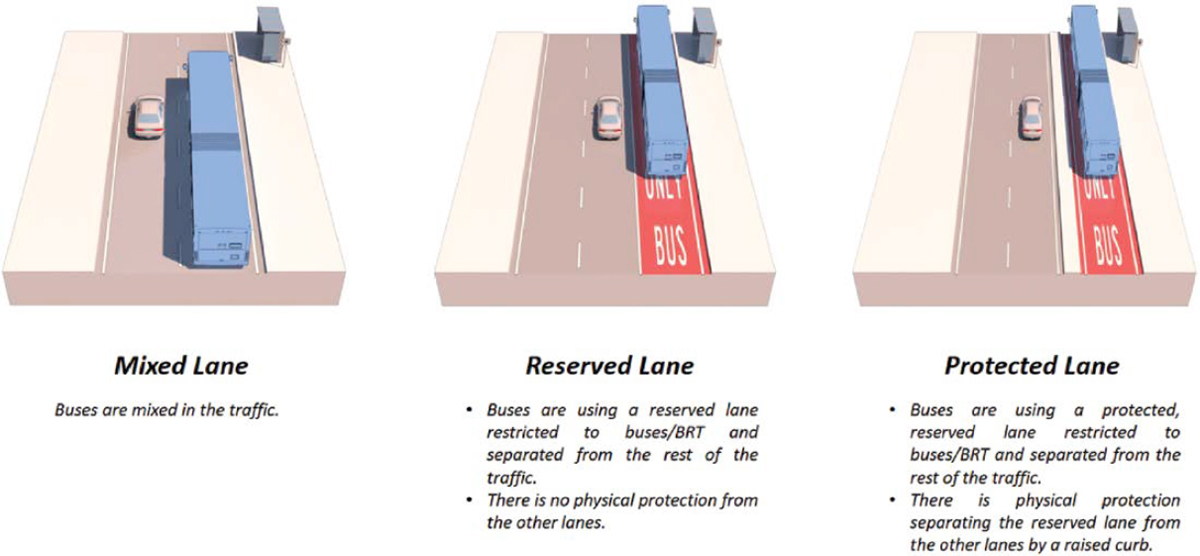

Off-street running ways might not be feasible in smaller or space-constrained airport environments, with BRT systems operating on the same streets as general traffic but with separate lanes and sufficient space for berthing (i.e., exiting the travel lane to collect and drop off passengers). These lanes should at least be clearly identifiable and distinguishable by using different pavement coloring or other signage, and barriers can be erected to separate BRT lanes from other traffic. To avoid curbside congestion, taxis, shuttles, and private vehicles should be loaded and unloaded on the opposite side of the road as BRT. Figure 61 and Figure 62 depict the main BRT and bus lane configurations, respectively.

System Operations

As is the case with most means of transport, one indicator of service reliability is delay—the difference between scheduled and actual times. Service reliability, among other factors, is directly correlated with ridership potential. TCRP Report 165: Transit Capacity and Quality of Service Manual, 3rd Edition (Kittelson & Associates, Inc. et al. 2013) divides causes for delay into two categories: delays at the bus stop and delays between stops.

Delays at bus stops are either intrinsic to the system’s operations or consequences of capacity being exceeded:

- Acceleration and deceleration into and out of bus stations.

-

Dwell time: time the bus spends loading or unloading passengers, including opening and closing doors. This timing is influenced by the number of passengers onboarding and alighting at each stop, onboard fare collection (or lack thereof), the number of doors available (e.g., in multi-door buses, passengers may board through the front door and alight through the rear one), and the need to accommodate passengers with reduced mobility (PRMs).

- – BRT improvements: on-station fare collection, multi-door fleets, accessibility.

-

Reentry and traffic signal delays: time during which the bus cannot advance while waiting for a green traffic signal or waiting to merge into the travel lane.

- – BRT improvements: semi-exclusive or exclusive running ways, traffic signal priority.

-

Boarding lost time: time spent by passengers finding the correct loading areas (only occurs at larger stops with multiple loading areas).

- – BRT improvements: line-specific loading areas, visual and aural announcement systems.

-

Bus stop failure: when buses are required to idle on travel lanes because all bus loading areas are occupied.

- – BRT improvements: real-time monitoring and metering.

Operations between stops can also be subject to delays, such as

-

Stop spacing: Reduced distances between stops leads to buses having lower running speeds or sustaining normal running speeds over shorter periods of time. However, reduced spacing between stops may be necessary in high-density areas where walking is the primary means of access.

- – BRT improvements: Stops are further apart; outside high-density areas, park-and-ride lots are used to encourage arrival by car.

-

Interaction with other traffic: Bus systems that run alongside other modes of transport can also be affected by road congestion or other delays.

- – BRT improvements: Exposure to other traffic is eliminated (grade-separated) or reduced (at-grade exclusive and semi-exclusive rights-of-way). BRT flow at at-grade exclusive and semi-exclusive sections can be further enhanced through signal control.

-

Stop location: On-street bus stops can be located immediately after crossing an intersection (far-side), immediately prior to crossing an intersection (near-side), and mid-block. Each of these can facilitate or hinder pedestrians, other buses, and general traffic; siting should be considered on a case-by-case basis.

- – BRT improvements: Stations can also be either grade-separated or off-street, which minimizes their effect on traffic flow.

-

Passing capabilities: A bus’s passing capabilities are its ability to change lanes to overtake an obstruction. Congestion or the lack of passing lanes can increase unnecessary idling times.

- – BRT improvements: BRT busways may include passing lanes.

- Near-saturation: Average bus speeds start decreasing at around 50 percent of lane capacity; these decreases become sharper beyond 70 percent due to inter-bus interactions and an increase in passing maneuvers.

TCRP Synthesis 110: Commonsense Approaches for Improving Transit Bus Speeds identified measures that can offset some of these delays, and these measures have led to a −0.45 percent annual change in average bus speeds nationwide. Some of these measures are design features of BRT systems that are now being implemented for conventional bus systems as well (Boyle 2014):

- Traffic engineering efforts to prioritize mass transit, such as signal priority and timing adjustments, bus-only lanes, and laws requiring yielding to buses.

- Maintaining transit routes along major corridors with few deviations and sharp turns, while also increasing distances between stops.

- Speedier boarding and alighting processes by using all doors that permit safe access to the bus and changing to prepaid ticketing models.

- Deployment of low-floor buses with ramps to reduce the time required by PRMs to safely board.

- Requiring buses to hold at stops when ahead of schedule, as well as optimizing schedules based on historic delay data and projected changes in ridership volume.

Automated Buses

Bus systems and other non-guided ground vehicles could potentially be automated by introducing connected vehicle technologies that are already available in private vehicles with SAE Level 2 technology (e.g., adaptive cruise control, lane keeping, speed adjustment in curves, and stopping for pedestrians and vehicles) and incorporating vehicle-to-everything (V2X) communications with roadway and station infrastructure, as shown in Figure 63.

Implementing platooning—multiple automated buses traveling in single file within close proximity while using internal technologies, such as radar, lidar, and cameras, or connected technologies, such as V2V communications, to keep a safe following distance—can maximize bus lane utilization and increase system capacity. At stops, automated driving technology would allow buses to pull into, stop at, and exit from precisely defined loading areas; automated passenger counting technologies can also be used to track load factors and enforce vehicle capacity constraints. The increased capacity achieved by platooning might translate into requirements for longer station-boarding areas (WSP 2022a).

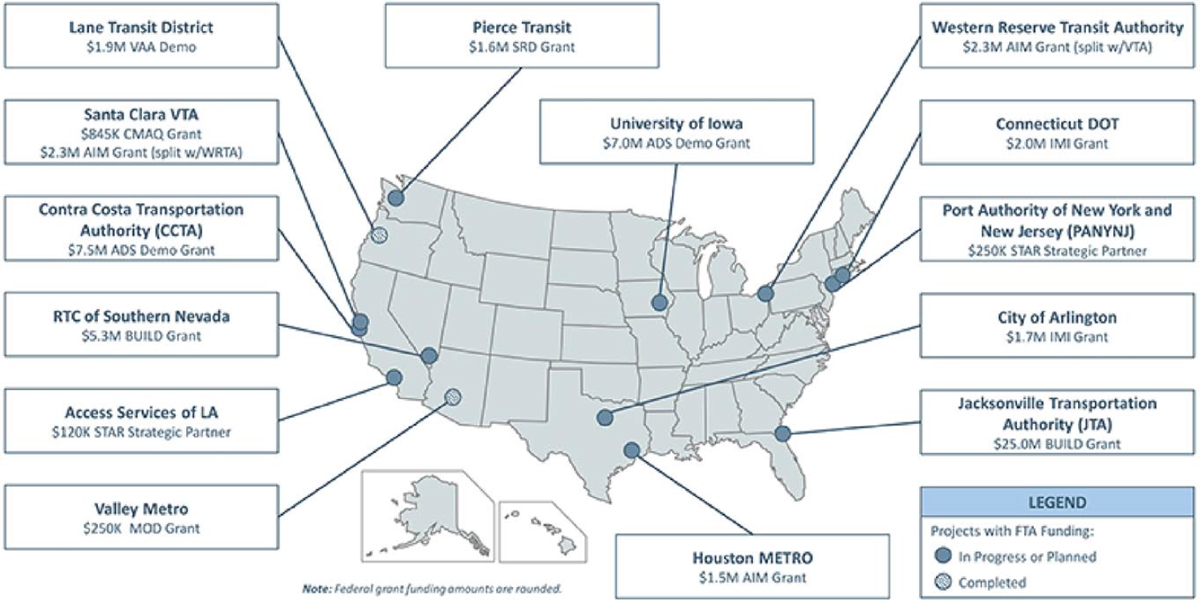

Adoption of automated buses will require testing to prove these vehicles’ safe operating potential to transit operators, potential riders, and the general public. To that end, the FTA is funding several pilot and demonstration programs across the country, as depicted in Figure 64.

Source: WSP (2022a)

Source: Federal Transit Administration (2021)

Note: AIM = Accelerating Innovative Mobility; BUILD = Better Utilizing Investments to Leverage Development; CMAQ = Congestion Mitigation and Air Quality; IMI = Integrated Mobility Innovation; MOD = Mobility on Demand; SRD = Safety Research and Demonstration; VAA = Vehicle Assist and Automation; VTA = Valley Transportation Authority; WRTA = Western Reserve Transit Authority.

Abroad, Scotland’s CAVForth program started revenue service demonstrations on a 14-mile bus line operating under SAE Level 4 automation in May 2023 (CAVForth 2023).

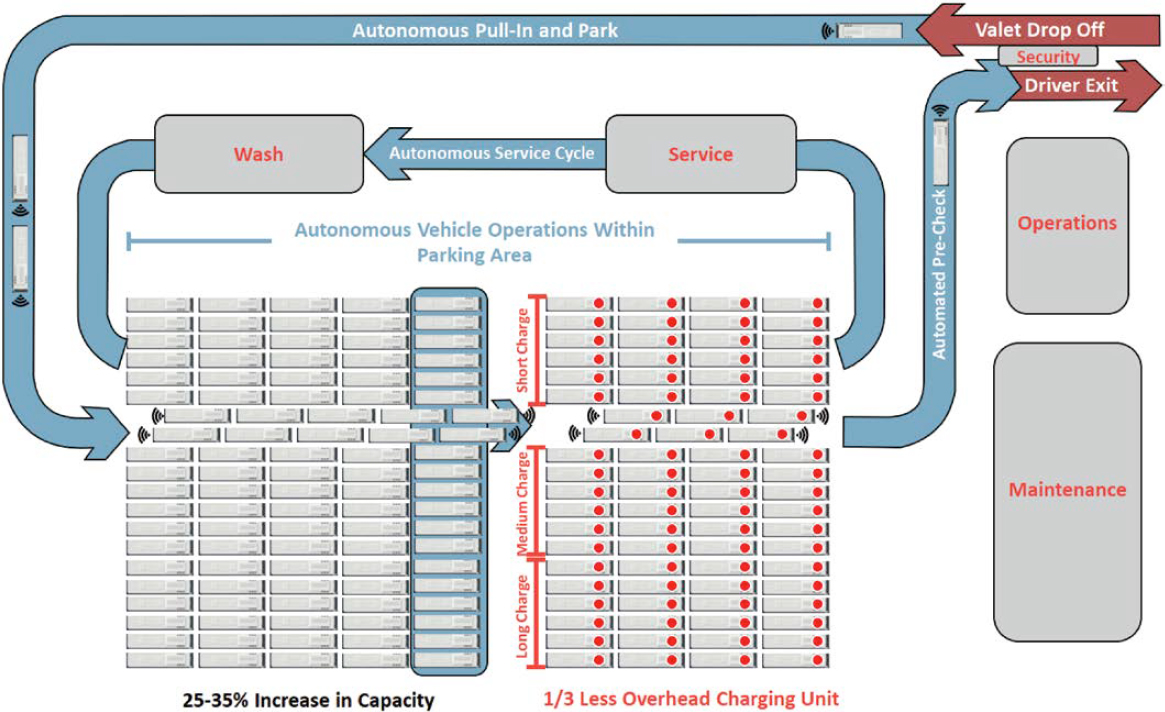

Benefits are also expected at yard facilities. Inside an automated bus yard (ABY), buses move in automated mode through the bus wash, charging stations, maintenance bays, and parking locations as necessary, as shown in Figure 65. Besides improving safety for bus yard personnel, these operations provide transit operators and bus manufacturers with continuous opportunities to verify operational safety and resolve issues that might be identified during the testing process (WSP 2022a).

Station Design

Station design for bus and BRT systems depends in part on the running way that the system will use at the station site and on the square footage available for station placement. Curbside platforms should be at least 10 feet wide and island platforms should have a minimum width of 20 feet to comply with ADA Accessibility Guidelines (ADAAG). Platforms should also be wide enough to accommodate 15-minute peak affluence for a planning horizon of 5 to 10 years. Both buses and platforms must be at an adequate height that allows easy ingress and egress for PRMs. Pedestrian crossings can be grade-separated or at-grade, with stoplights controlling traffic flow for the latter.

The simplest and least expensive implementation of a passenger loading area involves buses stopping on the travel lane closest to the bus stop to serve it. This approach leads to a linear loading area where buses follow a first-in, first-out sequence; buses cannot leave the station

Source: WSP (2022a)

until the bus ahead has done so. A variation of this is the “bus bulb,” where a section of the curb otherwise used for parking or pedestrian movements is reserved for buses to board and alight without impeding the flow of traffic in travel lanes. BRT stations and larger bus stops are more likely to use nonlinear loading areas, where buses will park in delineated locations outside traffic lanes and at an angle to them, allowing freer access between the travel lane and the loading area. Germany conducted research and development of docking guidance concepts where rail-like features guide buses into and out of the loading area to minimize the gap between the bus and the platform, facilitating access to the bus for PRMs and passengers with luggage or strollers (Leigh Fisher Associates et al. 2000).

BRT is characterized by an increased LOS relative to conventional bus systems, including additional infrastructure for passenger safety and security. “Sheltered” waiting areas, with at least one wall—and preferably three—are expected to provide passengers with protection from winds and precipitation while waiting for their bus. The walls in these waiting areas should be transparent to allow passengers within the waiting area to see outward, and vice versa. Basic facilities, such as trash bins, should be provided.

For BRT systems, fare collection is carried out at the station—not onboard the bus—to reduce boarding times from 2–5 seconds per person for on-bus fare collection to 1.75 seconds per person for off-bus collection (Kittelson & Associates, Inc. et al. 2013). Kiosks can be made available for single-ticket or ridership card acquisition and to reload ridership cards. Tickets can also be purchased through authorized mobile apps that use QR codes or near-field communication for pass validation. Enforcement of fares is possible through physical barriers that limit access to only riders with valid tickets. However, this strategy requires additional infrastructure investments and additional floor space to separate the boarding area from the rest of the station. An alternate strategy involves random inspection of tickets by system staff onboard the bus, which entails additional manpower and operating costs.

Bus signage should be consistent along the transit system. While states and municipalities may have their own standards—such as the North Carolina Department of Transportation’s Bus Shelter & Bus Stop Guidelines (2017)—they are expected to meet the criteria in the MUTCD. Stops should be clearly identified by name and include route maps for the bus lines serving them, connection information, and route frequencies. If specific bus lines stop at different loading areas, this should also be indicated to prevent boarding lost time. Signage should allow for progressive wayfinding (i.e., turn-by-turn guidance, when not obvious), be illuminated in low-light conditions, and be accessible to people with visual disabilities (e.g., braille or other haptic aids, differentiated pavement textures, color palettes distinguishable to people who are color-blind, aural announcements). Display boards indicating next arrivals and corresponding loading areas should also be provided, if possible (National Association of City Transportation Officials n.d.).

Implementation at Airports

Travelers using bus systems to and from airports are likely to arrive at bus stops and stations by foot. TCRP Report 90: Bus Rapid Transit, Volume 2: Implementation Guidelines (Levinson et al. 2003) states that BRT stations are typically spaced between ¼ and ⅓ of a mile apart from each other. Smaller airports might only require one station, but airports with longer curbsides or multiple terminals should consider implementing multiple stations. At the same time, stations should be spaced far enough to reduce trip times and maintain high operational speeds.

One specificity of airport bus riders is that they are more likely to travel with luggage than riders who commute by bus. This creates line-specific design challenges that would require level entry into buses (either by low-floor or elevated platforms, or a combination thereof) to reduce dwell times associated with riders carrying luggage up and down steps. Level entry would also

improve ADA compliance within these systems. Luggage storage options should also be provided to prevent passenger luggage from occupying or blocking access to otherwise open seats (Leigh Fisher Associates et al. 2000).

Signage between bus or BRT stations and airport terminals should provide clear wayfinding from the station to the airlines’ check-in desks as well as from the baggage claim areas to the station, following the parameters described in the previous section on station design. The airport terminal signage may have a different yet standardized appearance that is also inspired by the MUTCD. Icons and nomenclature between signage for the airport and transit systems should be consistent to avoid confusion (Harding et al. 2011).

Heavy Rail

Corridor

Heavy rail is characterized by fully grade-separated rights-of-way; high-level platforms; and high-speed, electric multiple-unit cars (Kittelson & Associates, Inc. et al. 2013). Unless grade separation is achieved through an elevated structure, tunnels, or wall above 6 feet in height, the right-of-way should be fenced because heavy rail transit systems should prohibit all access to their rights-of-way. Basic security fencing includes chain link fence that is at least 6 feet high and other fences that provide similar or improved intrusion protection. Access to the right-of-way should be controlled by locked gates (American Railway Engineering and Maintenance-of-Way Association 2021).

Based on project examples provided by the FTA and manufacturer specifications, consolidated by the Florida Department of Transportation Office of Freight, Logistics, and Passenger Operations, an average corridor width of heavy rail is between 25 and 33 feet. The average corridor width does not include space for stations or potential widening at turns. Additionally, unlike other types of passenger rail, heavy rail is unable to operate on freight tracks per restrictions by the Federal Rail Administration, eliminating the possibility for a shared corridor between heavy rail transit and freight rail systems (Florida Department of Transportation 2017).

Right-of-Way

Right-of-way is the term for all property interests and uses necessary to build, maintain, safeguard, and run a transportation system (Skanska 2013). Some right-of-way requirements are temporary, while others are permanent and driven by operational requirements. The following are guidelines for determining the right-of-way limit according to the Metro Rail Design Criteria (Skanska 2011):

-

Underground (below grade):

- – Upper limit: The upper limit is the vertical distance between the top of the rail line and the object or structure above; and 10 feet is the minimum requirement for the vertical distance.

- – Horizontal limit: The horizontal limit is a lateral distance of 5 feet (for earth tunnels) or 10 feet (for rock tunnels) from the surface of the tunnel. Allowances shall be made for rock bolting or grouting, which may be required.

- – Lower limit: Lower limits are usually not applicable to underground rail systems.

-

At grade:

- – Upper limit: An upper limit is usually not required for at-grade rail lines. When required, the minimum distance between the top of the rail line to the upper surface should be 16 feet, 6 inches.

-

- – Horizontal limit: The following conditions determine how far the nearest track’s centerline must be from the right-of-way limit when using an exclusive right-of-way:

- With walkways outside of the track, utilize the dynamic envelope of the rail car, the horizontal track construction tolerance on both tangent and curved alignments, as well as the individual state’s Public Utilities Commission minimum clearance standards.

- With walkways between the tracks, utilize the dynamic envelope plus the running clearance of the rail cars as well as the horizontal track construction tolerance.

- – Lower limit: Lower limits are usually not applicable to at-grade rail systems.

- – Horizontal limit: The following conditions determine how far the nearest track’s centerline must be from the right-of-way limit when using an exclusive right-of-way:

-

Above-grade:

- – Upper limit: Similar to at-grade rights-of-way, the minimum distance from the top of the rail line, when required, to the upper surface should be 16 feet, 6 inches.

- – Horizontal limit: The horizontal limit is a lateral distance of 25 feet from the track’s centerline. For the upkeep and repair of structures, easements would be required.

- – Lower limit: The lower limit shall be the ground level, with particular usage limits when they are necessary due to local conditions and as ordered by state or county, with the exception of when crossing other rights-of-way.

Signal and Communication Systems

A heavy rail signal and communication system involves many or most of the same components as for other rail systems. A heavy rail system should operate with an automatic train control (ATC) system in place, which is “designed to address train safety, control train operations, and direct train movements on the main line and in the yard” (Skanska 2013). System design objectives should include safety, operational efficiency, cost-effectiveness, and upgradability.

The ATC system includes four major subsystems, according to the 2010 Metro Rail Design Criteria (Skanska 2013):

- Automatic train protection (ATP) enforces speed restrictions when actual speed is greater than maximum safe operating speed for any given section of track. Speeds are transmitted to the train through either track circuits or wire loops from the wayside equipment.

- Automatic train supervision controls and directs train movements on the main line and in the yard. This subsystem monitors train operation and provides controls, indications, automatic route initiation, and automatic dispatching to maintain the intended traffic patterns and operations schedule.

- Highway crossing warning system (HCWS) provides an interface between the wayside signal equipment and the crossing warning devices. The interface between the two should provide timely information about, and protection from, an approaching train.

- Train-to-wayside communication system communicates between trains and vehicle equipment or wayside interrogators at appropriate points along the route. Information communicated may include vehicle identification, routing information, establish or cancel routes, and activate or deactivate HCWS.

As noted previously, the systems should be designed for upgradability, which includes building for easy expansion of the system should future needs outpace existing infrastructure or should future upgrades to the existing system be required. As such, ATC subsystems should be developed as a building block design with minimal modifications at the outset so they can be modified or added to with minimal complications.

Stations

Heavy rail systems use platform stations, and typical spacing is less than 1 mile between stations for heavy rail operating within a city and 1–5 miles or more between stations for heavy

rail operating in the immediate suburbs (Florida Department of Transportation 2017). Any planning for an underground or elevated system should consider the potential for future growth since these stations, located above or below grade, are difficult to lengthen once constructed.

Site Development

To begin site planning, factors such as existing building relationships, future joint developments, as well as ethnic and cultural characteristics of neighborhoods should be considered.

Accessibility

The design must adhere to all applicable accessibility requirements, such as ADAAG, published by the FTA. As far as practicable, all accessible entrances must be similar to those utilized by the majority of the general public. Signage that complies with ADAAG requirements must be provided to identify and lead people to the accessible entry and route if the circulation pattern is different. Platform barriers must be available and meet ADAAG standards.

Entrances

- The following factors must be considered when designing a station’s entrance:

- – For the convenience of the public—especially passengers—as well as for operational and maintenance needs, entrance designs must maintain a clear, highly visible, and unique identity.

- – Provide direct and safe pedestrian access.

- – Entrance canopies must be provided to offer weather protection.

Circulation

- When designing passenger circulation, encourage a “user friendly” mindset, with simplicity of use and easy route identification. These factors should also be considered when designing passenger circulation:

- – People tend to keep to the right, thus right-hand flows are recommended, although not mandatory.

- – Any crossflow of passengers is highly undesirable, and the layout should ensure that passenger flows moving in the opposite direction will be separated at all times.

- – Dead-end conditions shall be avoided wherever possible.

- – Whenever there is more than one opening, people tend to move toward the nearest one, even if they are not sure whether it is the right one.

- – People will tolerate longer delays in entering than exiting stations, but designs of stations should attempt to eliminate waiting.

- – Circulation patterns and station layouts should enable passengers to know where they are and where they are going at all times.

- – Queuing distances shall be maintained at all stations to promote and guarantee ease in circulation and access to trains.

Platform Configuration

Station platforms are designed for the longest train that the system plans to operate, which optimizes the flow capacity of the train doors. For station platforms that are shorter than the train length, passengers must exit and enter from selected cars at the beginning or end of the train, which is not desirable practice and is atypical for new systems (Kittelson & Associates, Inc. et al. 2013). To meet ADA requirements, platforms should have tangent (straight) edges and the surface of the platform level with the train vestibule. Additionally, there should be no more

than a 3-inch gap between train door and platform edge. Space planning for platforms should include space for boarding passengers to queue and space for alighting passengers to exit the train to transfer to vertical circulation elements. The following factors must be considered when designing a station’s platform:

- All platforms, whether center or side platforms (depending on traffic conditions, site constraints, or layout of station), should be raised.

- All platforms should have a 24-inch safety edge.

- Freestanding columns within 10 feet of the platform edge shall be located away from vehicle doors during station stops to minimize congestion.

- Platforms should accommodate the peak 15-minute departing passenger volume at 10 square feet per person or the peak 15-minute departing and arrival passenger volume at 7 square feet per person.

- The warning line or “stand behind” line shall be drawn or embedded into the platform.

Concourse

The concourse serves as a passageway between the station’s entrance and access points to the train platforms. Additionally, the concourse also serves as a location for a number of conveniences for passengers, such as fare gates, passenger waiting areas, concessions, and other amenities. Concourses can either extend the full length of the station or occupy a portion of the station.

Station Dwell Times

As a factor in operational efficiency and a typical primary factor in the number of trains that can operate at a time, station dwell times are an important component of the system to consider. According to TCRP Report 165 (Kittelson & Associates, Inc. et al. 2013), factors affecting dwell times include

- The volumes of passengers boarding and alighting from trains during peak hours;

- The physical configuration of the platform: its width, length, curvature, usable area for passenger queuing and circulation, and configuration and capacity of vertical circulation;

- The rate at which passengers alight from and board the train;

- The extent of any horizontal gaps between train door sill and the platform edge or differences in elevation between the platform and the car floor, which affect the rate at which passengers board and alight;

- The time required to open and close the train doors; and

- Operational procedures affecting the boarding process.

Support Facilities

Zoning for support facilities, such as shop and yard facilities, should ideally be light industrial and located away from residential neighborhoods. Support facilities generally take on a rectangular shape for buildings, thus the most desirable siting parcel would be either rectangular or trapezoidal. Land for yards and shops needs to “accommodate car storage tracks, inbound service and inspection tracks and shop buildings” and should allow sufficient width to provide a turning loop on the property (American Railway Engineering and Maintenance-of-Way Association 2021). A list of facility functions that are needed to support rail transit are provided in American Railway Engineering and Maintenance-of-Way Association’s (AREMA’s) 2021 Manual for Railway Engineering.

Implementation at Airports

According to TCRP Report 62: Improving Public Transportation Access to Large Airports (Leigh Fisher Associates et al. 2000), for airports the main elements of a successful airport rail system are

- Service to downtown metropolitan area: For an effective and efficient rail service to the downtown area, focusing on either rail line speed from downtown to the terminal and vice versa or the quality of services as well as limiting the headway caused by joint operation with other regularly scheduled services should be priorities. Both approaches aim to generate a door-to-door travel time that rivals that of a taxi or a private automobile.

- Service to national destinations beyond the metropolitan area: Most airport rail connections to national destinations are integrated with other rail services and are not provided by a special dedicated service. The size of the national rail network into which an airport has been linked is crucial because the lack of such a network will make these initiatives difficult or impossible.

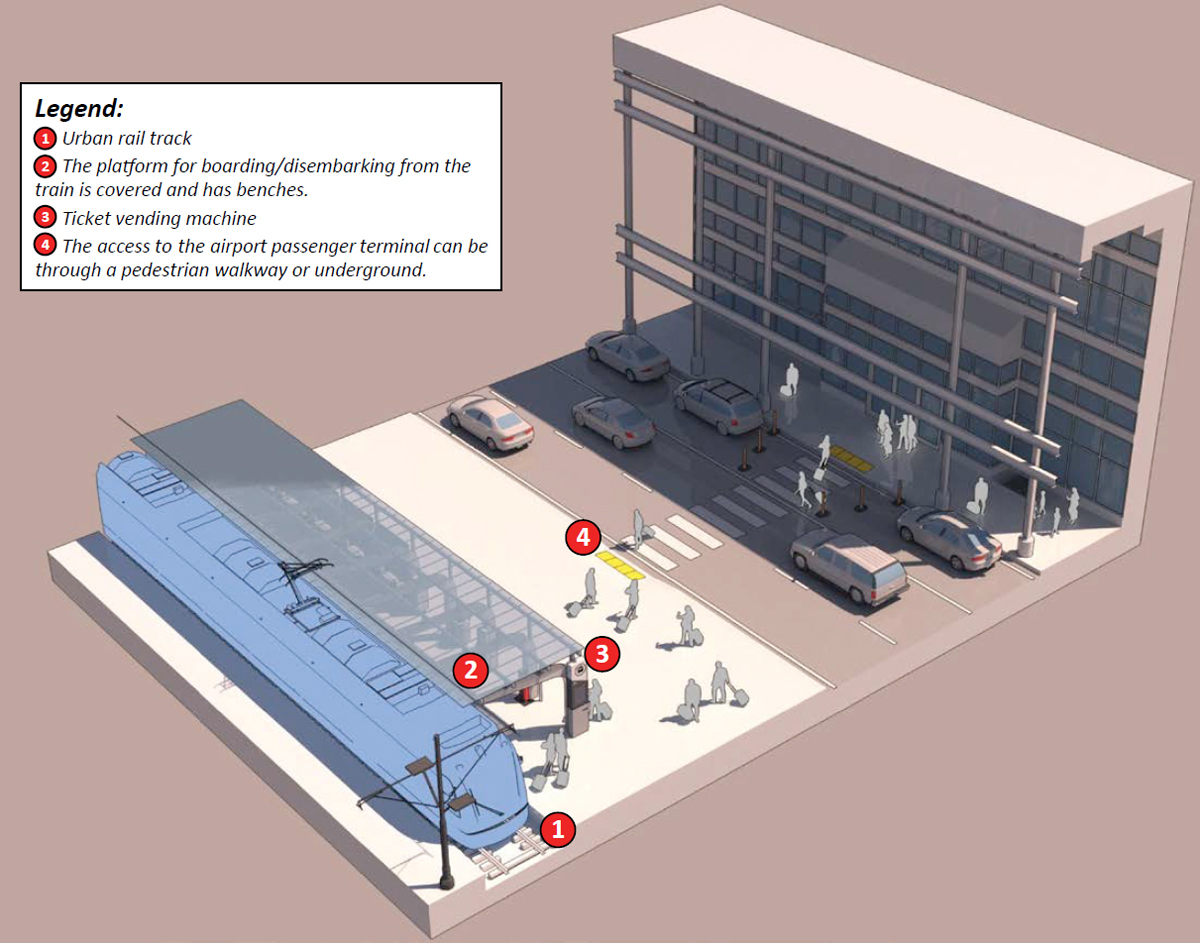

- Quality of rail connections at the airport or airport-railway interface: Important considerations to ensure a quality rail connection are the quality of service offered by the train, the quality of the boarding experience, and the quality of the experience when connecting to other modes to reach the final destination. Another relevant factor is the ease of finding the rail station and the seamlessness of the connection to that rail platform. A high level of collaboration between the rail system designer and the airport designer is frequently necessary to create a high-quality, multimodal transfer facility (Figure 66).

-

Baggage-handling strategies and off-site facilities: For all designers and developers of airport ground access systems, developing a plan to address the issue of baggage is a challenge. Various solutions to the issue have been developed, ranging from making minimal changes to building expensive, full-service, off-site check-in facilities. However, a number of less expensive options are being tested globally. Off-site baggage-handling services can be divided into two main groups:

- – Full-service downtown check-in locations: This service is based on the idea that airlines will offer complete check-in services, including issuance of airline tickets and accepting luggage at off-airport rail stations. These services are performed by airline personnel.

- – Nationwide programs to handle numerous off-site check-in options: Instead of individual airline personnel staffing the baggage-handling services at off-site locations, a third party is employed to handle all baggage check-in services nationwide at all off-side facilities.

Light Rail

Trackway and Vehicle Compatibility

When determining how and where to position rail tracks, several design components need to be considered. Track grading needs to be shallow enough to allow vehicles to ascend under their own power and to descend without applying excessive loads on braking systems. Conversely, tracks also need to be steep enough to allow drainage to occur, unless alternative means to do so are provided. For LRT systems, TCRP Report 155: Track Design Handbook for Light Rail Transit, 2nd Edition proposes a maximum sustained grade of 4.0 percent without distance limitations, which can be increased up to no more than 9.0 percent or the vehicle’s operating limitations (whichever is less) for shorter distances; a minimum grade of 0.5 percent is also recommended (Parsons Brinckerhoff, Inc. et al. 2012). These requirements have been incorporated into the design codes for local LRT projects, such as Sound Transit’s project in the Seattle metropolitan area (Sound Transit 2021).

LRT is unique among urban rail systems in that it may operate at-grade along city center streets, thus it can be constrained by the geometry of streets and adjacent land use (buildings, parks, etc.). A minimum turn radius for horizontal tracks of 82 feet is recommended; this is derived from European practices, which accommodate usual train car lengths and widths. This is not a formal standard—manufacturers have developed cars with turn capabilities as low as 42 feet, and transportation agencies in Philadelphia, San Francisco, Boston, and elsewhere have permitted tighter curve radii (Graebner et al. 2007). Consecutive curves in opposite directions (reverse or “S” curves) need to be separated by a minimum length of straight track to remain within wheels’ performance envelope and to avoid passenger discomfort. LRT vehicles can be designed to be articulated to improve their handling, but the functionality improvements are related to the length of the articulation—longer articulations result in smaller improvements in minimum turn radii. Speed limits are set to keep lateral acceleration below 0.1g (g = gravity of Earth), which is considered the maximum acceleration that can be comfortably experienced by riders; in curves, this also accounts for the effects of superelevation, a difference in elevation between the outer and inner rails in a turn that can neutralize centripetal acceleration forces (Parsons, Brinckerhoff, Quade and Douglas, Inc. 1999).

A typical modern LRT vehicle is approximately 82 feet long, 9.5 feet wide and runs along straight tracks (articulated vehicles’ effective width may increase up to 11.7 feet during turns). Vehicle cars also have a street-to-ceiling height of approximately 11.5 feet, not including current collector systems (National Association of City Transportation Officials 2016). The most demanding physical parameters that govern the dimensions and configuration of the train’s rolling stock are the system’s tracks.

Right-of-Way

The MUTCD specifies that LRT systems can have either exclusive, semi-exclusive, or mixed-use rights-of-way (Federal Highway Administration 2023). Exclusive rights-of-way can be attained by grade separation (through underground or elevated tracks) or barriers to control access (fences, traffic barriers, or a combination of both). In the rights-of-way for LRT systems, neither motor vehicles, pedestrians, nor bicycles are allowed. Semi-exclusive rights-of-way allow access for motor vehicles, pedestrians, and bicycles but only at crossings and designated locations, while mixed-use rights-of-way allow other traffic to operate alongside it. Exclusive and semi-exclusive rights-of-way are more likely to exist outside of downtown areas, while mixed-use rights-of-way may become necessary within downtowns due to street space limitations.

When LRT systems operate in semi-exclusive rights-of-way, the MUTCD calls for implementation of traffic control systems to prevent unauthorized incursions when a trainset is passing. These systems can consist of aural and visual alerting systems and movable barriers. Implementation of these systems needs to be carried out on a case-by-case basis that accounts for the specificities of each crossing (Federal Highway Administration 2023). When planning rights-of-way, consider drivers’ and pedestrians’ habits: Longtime residents might not register the changes in rights-of-way early in the implementation process, which could lead to not noticing traffic control devices and potentially result in collision situations.

LRT systems generally require a minimum running clearance of 2 inches, applied horizontally, from other obstructions and vehicles; these clearances increase to 6 inches along aerial decks and between LRT vehicles. Vertical clearances are predicated on a margin between 4 and 6 inches from the clearance envelope, including the effects of superelevation (Parsons, Brinckerhoff, Quade and Douglas, Inc. 1999). LRT operations in mixed-traffic conditions should take place in lanes that are at least 11 feet wide for straight segments; additional width shall be provided for curved tracks to accommodate the train’s envelope. For LRT systems that operate with overhead power, catenary wires are located between 17 and 20 feet above street level; these need to be kept clear of other tall features (e.g., trees and traffic signals) and not hinder traffic signal visibility (National Association of City Transportation Officials 2016). Rolling stock, whether purchased, leased, or remanufactured, must be accessible to and usable by individuals with disabilities, as mandated in 49 Code of Federal Regulations (CFR) Part 37, Sections 79, 81, and 83.

Stations

Rail infrastructure requirements are more restrictive at stations than along the transit corridor to ease passenger boarding and alighting and to comply with ADA requirements: Track grades should be between 0.5 and 1.0 percent at stations, compared to 4.0–9.0 percent elsewhere. LRT platforms, like those of other mass transit modes, should be sized relative to the estimated peak 15-minute affluence of the station—offering at least 15 square feet of waiting room per person. Sound Transit’s standards recommend that platforms should have at least 380 feet of available length for boarding and alighting a four-car train.

Platforms can be either centered (island) or on the side; the decision of which type to build should be based on expected peak affluence and integration with the urban environment

(streets and other transit systems, such as BRT), with the ultimate goal of improving system efficiency. At-grade platforms’ minimum widths vary according to their configuration: Center platforms should be at least 20 feet wide, while side platforms should have an edge-to-wall width of no less than 12 feet. Neither columns nor walls should be placed within 8 feet of the platform edge since these could interfere with the safe operation of train doors; station components such as vertical circulation nodes can encroach onto the platform width if this width is never reduced below 8 feet. The 2 feet area closest to the platform edge should have haptic aids (dome pavers) to comply with ADA requirements; passengers should not wait in this zone. To facilitate drainage, platforms should have a 1 percent cross-slope toward the trackway. Like other means of transport, LRT stations should also have three-walled, roofed shelters or windscreens to protect waiting passengers during weather events.

Because LRT stations might be placed at-grade among dense city streets, unlike heavy and commuter rail, reduced available station space might preclude the placement of fare gates and their division of station space into free and paid areas. Rather, LRT systems are more likely to operate on proof-of-payment, where train access is not controlled but manual ticket inspection takes place onboard; this option is also more feasible due to the smaller vehicle size and thus lower personnel requirements.

Implementation at Airports

TCRP has described the factors involved in developing a successful rail system at airports, which also concerns LRT. Integration of LRT at airports might be suitable at airports where the forecasted ground access ridership is too large for BRT service to operate but too low for heavy or commuter rail systems. Since right-of-way and platform requirements between BRT and LRT have some similarities, airports could receive BRT services initially and then switch to LRT as passenger demand increases. At-grade LRT can also be integrated into the airport’s roadway system, minimizing construction costs.

However, there might be situations where running LRT systems at-grade is not efficient and grade-separated rights-of-way would be necessary, such as the Seattle-Tacoma International Airport (SEA) station. At this station, elevated rails near the airport and its runways could become obstacles to air navigation, so land use coordination with the airport is imperative; and transit planners should be open to rerouting the LRT’s tracks or reducing the track elevation, or both.

As is the case with other modes of ground access, signaling should be standardized, and routing to and from the airport terminal needs to be simple and unambiguous.

Commuter Rail

Corridor

Since building new infrastructure is cost prohibitive, commuter rail typically runs on a shared corridor with freight railroads. According to the American Association of Railroads (2023), half of all commuter systems operate at least partially on freight-owned track. Typical maximum operating speeds range from 60 to 90 mph (97 to 145 kilometers per hour [km/h]) with average speeds between 20 to 45 mph (32 to 72 km/h), depending on the route length, number of stations, and types of service. The Federal Railroad Administration’s Highway-Rail Grade Crossing Guidelines for High-Speed Passenger Rail mentions that “for speeds less than 80 mph, standard and supplemental safety devices should be used to maintain safety at highway-rail grade crossings along lines used for passenger systems” (Federal Railroad Administration 2009b). Table 24 is a summary of highway crossing guidelines for various passenger-rail operations based on operational speed.

Table 24. Summary of Grade Crossings for Passenger Rail

| Commuter Rail | Emerging High-Speed Rail | High-Speed Rail Regional | Additional High -Speed Rail | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Max Speed | 0–79 mph (0–127 km/h) | 80–110 mph (129 –177 km/h) | 111 –125 mph (179 –201 km/h) | >125 mph (>201 km/h) |

| Public Highway-Rail Grade Crossings, Generally | Automated warning: supplementary measures were warranted | Sealed corridor; evaluate need for presence detection and positive train control (PTC) feedback | Barriers above 110 mph (129 km/h), see 49 CFR § 213.247; presence detection tied to PTC above 110 mph (129 km/h) | None above 125 mph (201 km/h) |

| Private Highway-Rail Crossings, Generally | Automated warning or locked gate preferred; crossbuck and stop or yield sign where conditions permit | Automated warning with gates or locked gates (interlocked with signal system at higher speeds) | None or as above | None above 125 mph (201 km/h) |

Right-of-Way

Per the NorthStar Commuter Rail Project Design Criteria (Kimley-Horn and Associates, Inc. 2006), the following guidelines are provided for determining the right-of-way:

- Fixed obstructions greater than 8 inches above top of rail shall be a minimum of 15 feet from track centerline, except where an exemption is agreed on.

- Along the main line, a minimum of 18 feet from track centerline to track centerline (double tracks) shall be maintained, except where the relevant authority grants an exemption.

- In the station areas, a 15-foot center-to-center distance with inter-track fencing and concrete ties extending 100 feet from the end of the platform shall be standard.

- Maintain a minimum of 23 feet overhead clearance from top of rail to a fixed overhead obstruction.

- No landscaping except turf grass and ground covers is allowed within 25 feet of track centerline (exemptions can be made for small-leaf trees separated from the tracks by intervening buildings), and landscaping must not impede visibility at grade crossings. Provision must be made for removal of runoff from the track area.

- A walking surface is to be provided and maintained along both sides of every railroad track. It extends 8 feet, 6 inches from track centerline.

Rolling Stock

The two most common types of commuter rail trains are diesel-powered trains and electric-powered trains that run on tracks with electric overhead catenary wires or third rails. In the United States, commuter rail trains typically consist of a single locomotive and several passenger coach cars. Depending on the train’s capacity, a commuter rail trainset typically has three to eight cars that are either single- or bi-level. Approximately 115 persons can sit comfortably in single-level coaches. Bi-level coaches may accommodate about 180 passengers and include seats on two separate levels.

- Locomotive equipment: Locomotive trains have a powered rail vehicle that is used to pull the whole train. For commuter trains, this vehicle could be powered by either electricity or a diesel engine (earlier forms used steam).

- Multiple-unit equipment: Multiple-unit trains have individually powered cars or carriages, also known as self-propelled vehicles. This means each car or carriage has a motor (traction electrical motor or diesel generator) that is controlled by a single system and driver. With multiple-unit systems, there can be a dedicated cab car or every car can be equally equipped with a driving console (meaning any car can be used as a driving cab).

Signal and Communication Systems

Because commuter rail agencies typically seek to use existing infrastructure that is primarily owned by private freight railroads, the communication and signal infrastructure is already installed for use. Commuter, intercity, or high-speed rail share the following signal and communication system considerations:

- Essential communications include communication between moving trains and wayside stations and control centers, as well as track-to-train communications. Moving-train-to-station communication includes both digital and voice radio and extends to dispatcher and train crew communications as well. Digital data links are used to transmit data between moving trains and control centers, including transmission from moving train to wayside station to control centers via radio over fiber optic cable, microwave, ultrahigh frequency, or very high frequency radio station segments. Track-to-moving-train communication uses inductive communication technology via a beacon, inductors, or transponders. Coded track circuits in the rail assets also transmit signaling data, speed commands, and more to the train cab, while systems that do not use coded track circuits can use digital radio links.

-

Onboard communications

- – Various visual signs, including station announcements, are required by federal regulation to aid disabled passengers.