Enhancing Airport Access with Emerging Mobility (2025)

Chapter: 3 Airport Access for All

CHAPTER 3

Airport Access for All

Accessibility

Reduced Mobility and Other Disabilities

During the congressional debate for the ADA in the 1980s, it was stated that 43 million Americans had a physical or mental disability. This number has likely increased since, owing to population growth, an improved life expectancy, increased median age (aging of the U.S. population), and reduced stigmatization and increased diagnosis of mental disabilities (National Council on Disability 2022). The ADA defines “disability” with respect to an individual as

- A physical or mental impairment that substantially limits one or more of the major life activities of such individual;

- A record of such an impairment; or

- Being regarded as having such an impairment. (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services 1973)

There is no clear consensus on what terminology is considered adequate to accurately describe the impairments faced by people protected by the ADA without also providing negative connotations that might be disagreed upon. The terms “disabled” and “handicapped” were used historically, and the latter is no longer preferred. The expression “special needs” gained traction in the 1960s, during the advent of the Special Olympics and education programs for learning disabilities, but people with disabilities perceive the term as condescending and pejorative. Gernsbacher et al. (2016) noticed that the term “special needs” is seldom used in federal law, while the term “individual(s) with disabilities” is extensively used. In this section, terminology used in the ADA (federal law) will be prioritized: “individual(s), person(s), or people with disabilities.” This terminology is considered more appropriate, as it acknowledges people’s disabilities while separating people from the disabilities they possess.

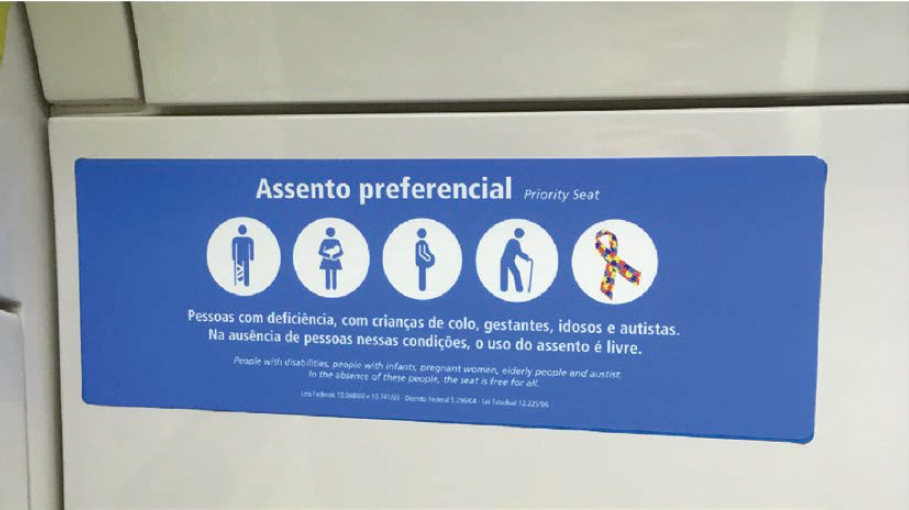

The universal symbol for disability accessibility consists of a person using a wheelchair, but this symbol falsely suggests that all disabilities are visible; rather, people with certain disabilities might not exhibit any indication that they have one. Disabilities can be physical (e.g., reduced mobility, blindness, deafness, or short stature) or developmental (e.g., brain injuries, epilepsy, Down syndrome, or speech impairments). Additionally, the term “neurodiversity” has been introduced to include atypical cognitive functioning, such as people on the autism spectrum and people with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder or ADHD, dyslexia, and beyond. Disabilities are quite diverse—whether hidden or apparent, transit and airport stakeholders need to provide a range of solutions and accommodations that represent this diversity. For example, Figure 15 shows the symbols used by the Metro of São Paulo, Brazil, to acknowledge priority seating areas for people with disabilities, whether visible or invisible. At the same time, people with hidden disabilities might choose to not identify them in public because they fear potential stigmatization or a lack of acknowledgment/recognition.

Source: Le Bris (2022)

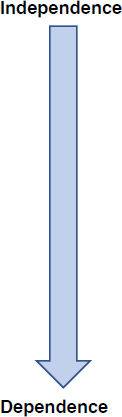

Disabilities can lead to increased dependence in daily life, such as when traveling through airports or on any of the ground access technologies presented in this report. Dependence refers to the need for assistance to carry out tasks that people without disabilities can perform unaided, ranging from using certain tools to requiring specialized and complete assistance. Design elements, such as ramps, elevators, and braille signage, can support travelers with some physical disabilities, while cognitive training of transit staff members can support users with mental disabilities or neurodivergence. Airports and ground access systems need to provide travelers with disabilities with sufficient resources or aids that allow for accessibility requirements to always be met wherever travelers are located within the ground access system or at the airport. Table 7 summarizes the assistance requirements for accessible transportation.

Accessibility from the Doorstep to the Gate

Airports might be connected to city centers via mass transit systems, but they may still have accessibility issues if these transportation systems are limited in terms of coverage, serving stations that are inaccessible, or priced too high for most users to afford the entire trip. Considering the first and last miles (FLM) and different populations of users, it is vital to provide accessible airport ground access. This approach should embrace the different steps of the airport user journey, from their origin to the gate and from the gate to their destination.

Passengers might use different transportation modes from their doorstep to the airport. For instance, a traveler could be dropped off at the nearest bus station by a relative, take a bus to connect with a bus rapid transit (BRT) line, and walk from the final BRT station to the terminal building. Obstacles to accessibility should be removed holistically on each step of the journey and at interfaces between steps. Frye (1996) called a seamless succession of accessible steps the “accessible journey chain.” Figure 16 provides two examples of a passenger journey from the doorstep to the gate.

Accessibility in planning and design is discussed throughout this report. Some barriers that can break the accessible journey chain for a multimodal trip to the airport (Figure 9) include the following:

Table 7. Passenger Dependence Categories and Requirements for Accessible Transportation

| Category | Assistance Requirements | Example | Mitigation in Transportation | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

No assistance. | User can travel alone without assistance. | Fully independent ride. | None. |

| Technical assistance. | User can travel alone only if supported by a technical aid of some sort. | User who is blind or has low vision using a cane or a service dog. | Audible walk indications. | |

| Personal assistance (localized). | User can travel alone if they have limited personal assistance at specific milestones of the journey. | User is in a wheelchair and needs to call an agent to board and leave the train. | Elevators and elevated walkways can make the journey wheelchair compatible. | |

| Personal assistance (full trip). | User cannot travel without someone accompanying them throughout the journey. | Severe subjective cognitive disorder that requires user to be accompanied. | Device-based. | |

| Full assistance. | User cannot travel without specialized assistance for every step of the trip throughout the journey. | User with tetraplegia requiring a specialized chair and personal assistance at every step. |

- A user’s boarding bus stop is not easily accessible by foot and is deemed unsafe at night for vulnerable riders.

- A user’s boarding bus stop is not designed in accordance with ADA practices and does not provide for accessible boarding.

- Connections are not seamless. For instance, a user’s alighting bus stop is not conveniently located for enabling easy connections with BRT service since there is no obvious pathway to the BRT station, and users need to cross a busy road without a pedestrian walkway to access it.

- The BRT ride to the airport is too expensive for most passengers and airport employees or is accessible through an app that is only compatible with newer and more expensive models of smartphones and electronic devices.

While the airport does not have control over most of these obstacles, it can engage stakeholders involved with each step of the journey chain to foster conversation on removing barriers to accessibility. The coordination and planning approach proposed later in this report has specific provisions for enhancing accessibility. A similar vision could be implemented for facilitating access for employees and enabling job opportunities across communities.

Accessible Design Standards and Guidance Documents

According to the University of Washington’s (2022) Disabilities, Opportunities, Internetworking, and Technology Center, accessible design is “a design process in which the needs of people with disabilities are specifically considered.”

Title II of the ADA, also known as 28 Code of Federal Regulations (CFR) § 35, was initially signed into law in 1990 to prohibit discrimination on the basis of disability in state and local government services, while Title III (28 CFR § 36) prohibits discrimination on the basis of disability by public accommodations and in commercial facilities. Title II and III requirements for new construction and alterations, which specify what is required for a building or facility

to be physically accessible to people with disabilities, were incorporated into 2010 ADA Standards for Accessible Design developed by the Civil Rights Division of the U.S. Department of Justice (2010a). Guidance on the 2010 ADA Standards for Accessible Design (U.S. Department of Justice 2010b) is a separate document that addresses changes to the standards, the reasoning behind the changes, and responses to public comments that were received on these topics. Additional guidance on accessible design is available with the U.S. Access Board (2023).

U.S. DOT’s 2006 ADA Standards for Transportation Facilities contains scoping and technical requirements for accessibility to sites, facilities, buildings, and elements by individuals with disabilities for public transportation facilities covered by the ADA in new construction and alterations. U.S. DOT’s ADA standards apply to facilities used by state and local governments to provide designated public transportation services.

Additional documents providing technical guidance for accessible design are available with local agencies, research institutions, as well as advocacy groups (e.g., American Council of the Blind’s [2022] Pedestrian Safety Handbook). Also, Airports & Persons with Disabilities Handbook (Airports Council International 2018) provides recommendations on how to consider persons with disabilities when designing new aviation facilities and improving existing ones. It features definitions and information on types of disabilities, discussions on infrastructure and architectural measures, and recommendations on operational and organizational measures.

From Accessible Design to Universal Design

The Center for Universal Design (1997) at North Carolina State University defined universal design as “the design of products and environments to be usable by all people, to the greatest extent possible, without the need for adaptation or specialized design.” Moreover, the International Organization for Standardization (ISO) (2018) defined usability in ISO 9241-11:2018 as “the extent to which a system, product or service can be used by specified users to achieve specified goals with effectiveness, efficiency and satisfaction in a specified context of use.”

The Center for Universal Design (1997) proposed seven principles of universal design:

- Equitable use: The design is useful and marketable to people with diverse abilities.

- Flexibility in use: The design accommodates a wide range of individual preferences and abilities.

- Simple and intuitive use: The design is easy to understand and use, regardless of the user’s experience, knowledge, language skills, or current concentration level.

- Perceptible information: The design communicates necessary information effectively to the user, regardless of ambient conditions or the user’s sensory abilities.

- Tolerance for error: The design minimizes hazards and the adverse consequences of accidental or unintended actions.

- Low physical effort: The design can be used efficiently and comfortably, with a minimum amount of fatigue.

- Size and space for approach and use: Appropriate size and space is provided for approach, reach, manipulation, and use, regardless of user’s body size, posture, or mobility.

Universal design principles can be helpful for developing and leveraging solutions that enhance accessibility for everyone. For instance, making the passenger journey accessible to specific user categories can enhance the overall experience and usability for other users as well. According to Tyler (2016), bus stops in close proximity to users may remove the need for some passengers to use a wheelchair while improving access for all. Some people might change dependence categories as a result of a change in required capabilities, such as an improvement in public transport. Some users might need a wheelchair because the bus stop is too far from their

origin, but an improved network design that brings the bus closer to their origin could allow them to make the journey without the assistance of a wheelchair.

As part of this approach, designers should consider all implications, including potential conflicting requirements arising from the various needs of different categories of users. For instance, Tyler (2016) explained that some users may dislike pedestrian crossings with tactile surfaces—wheelchair users might find tactile paving uncomfortable, visually impaired pedestrians might dislike the slope, and ambulant older adults might find the combination of the slope and surface reduces their contact with the ground, which can be a hazard, especially when the street is wet.

Ultimately, accessibility is not only a design issue; programs for all stakeholders can develop activities to raise awareness and facilitate communications about specific needs, such as the Hidden Disabilities Sunflower (n.d.) program. Practitioners can also find useful guidelines on accessibility measures for ground transportation in NCHRP Research Report 1000: Accessibility Measures in Practice: A Guide for Transportation Agencies (Karner et al. 2022), as well as tools for assessing airport programs for travelers with disabilities and older adults in ACRP Research Report 239: Assessing Airport Programs for Travelers with Disabilities and Older Adults (Ryan et al. 2023).

Wayfinding for Airport Access

Recurrent Challenges with Wayfinding

In this report, “wayfinding” is defined as the process of orienting passengers to travel from one place to another. The wayfinding process from doorstep to aircraft seat, from aircraft disembarkation to destination, and back again is never fully straightforward for all users; the same journey can be planned and experienced differently depending on the user. Routes go across the delineation of individual facilities, comprise many decision points along the way, and feature several signs that follow different codes and design principles. Also, each person will experience the same journey differently based on factors such as physical mobility and independence, cognitive or vision impairment, cultural and linguistic background, and familiarity with the facility.

Airports can become complex spaces that, despite the best efforts of planners, architects, and designers, are difficult to navigate for at least some user categories. For instance, making signage visible and intelligible to all users is difficult when an area or corridor features different points of entry. Decision points can become saturated by situational and directional signs, especially when they are also used for advertisement opportunities. These difficulties can be exacerbated in situations where the typical path of one’s journey is temporarily changed (e.g., construction work). In addition, airports with facilities built or rehabilitated over long periods of time may have outdated or inconsistent signage that does not comply with the newer standards applied elsewhere.

Studies consistently show the importance of wayfinding and give it significant weight in determining a terminal’s overall level of service (LOS). Although signage cannot overcome physical limitations and geometric complexities of airport terminals or ground transportation facilities, a well-planned wayfinding system can improve the efficiency and safety of the space. Table 8 shows a list of common issues with signage and potential solutions.

With airport access, the presence of signs that are governed by different priorities and standards—for example, from the airport operator and from the transit authority—contribute

Table 8. Common Signage Issues at Airports

| Common Issues | Potential Solutions |

|---|---|

| Signs are hidden from certain locations in the terminal. | Sign location must be considered. Signs must be located at visible decision points that are clear from obstructions. |

| Signage is not understood by certain user categories. | The meaning of the sign should be clear to all users; evaluations with representatives from each user category should be performed. |

| Signage does not provide guidance all along the journey. | Signs must communicate with different types of passengers; even when users have different origins and destinations, signs should be located at visible decision points. All origination and destination points need to connect with the wayfinding system. |

| Signage does not indicate all options. | Signs must be located at decision points where the user has the option of taking different paths. Signs should provide alternative information for users with different needs when traveling from point A to point B, such as signs with elevator locations that are visible when approaching stairs. |

to the challenge of developing an efficient system that is straightforward for all. Signage is one of the few domains that has not been extensively codified by industry organizations in aviation. Therefore, each operator has its own design standards. These standards and guidelines can vary widely—some are elaborate and comprehensive, others are neither. Airports with design standards range from non-primary commercial service airports (e.g., La Crosse Regional Airport [LSE]) to large-hub airports (e.g., LAX, Dallas Fort Worth International Airport [DFW], Seattle-Tacoma International Airport [SEA]). Transit authorities and operators of mass transit systems typically have their own design standards.

Key Principles in Sign Design and Location

As mentioned in ACRP Report 52: Wayfinding and Signing Guidelines for Airport Terminals and Landside (Harding et al. 2011), the cognitive limitations of users, how they acquire knowledge and understanding, impact sign design. Thus, when human factors are taken into consideration, these principles allow for signage to be effective:

- Continuity: Unbroken and consistent existence or operation, which in this case refers to the stability of the wayfinding process. Some airports have developed their own signage standards for continuity and identity in their respective facilities. As described in ACRP Report 52 (Harding et al. 2011), there are different ways of applying the continuity concept, and a common method includes thinking of each decision point as a wayfinding chain. This applies mostly to linear wayfinding scenarios. When the user reaches a decision point and the message they are following is missing, the wayfinding chain is broken, and they become lost. The Port Authority of New York and New Jersey (PANYNJ) describes wayfinding as more than signage—it is about all the ways that people find their way. Lighting, architectural, and interior design enhance spatial legibility and provide navigation and orientation cues (Port Authority of New York and New Jersey 2020). Unique landmarks, such as prominent architectural features or art installations, can serve as reference points for orientation and navigation, as shown in Figure 17.

- Connectivity: Signage must be able to clearly guide users, regardless of their origin and destination. To do so, all possible origin and destination points need to be connected to one

Source: Harding et al. (2011)

- another in the wayfinding system. Passenger groups by type should be considered, including departing and arriving passengers as well as arriving passengers who are terminating or connecting.

-

Consistency: Signs should be consistent with the airport’s wayfinding strategy and with proven wayfinding design principles that consider specific locations, architecture, codes, languages, demographics, and other factors. Consistency becomes visible to passengers through the following elements:

- – Terminology and message hierarchy,

- – Visibility and legibility,

- – Typography and symbology, and

- – Format and color.

- Comprehensiveness: The meaning of a sign should be clear to users. Although the sign might be clear for the designer, it is important to evaluate with representative users to make sure signs are understood. For example, an arrow pointing upward could be interpreted ambiguously as either “straight ahead” or “go up one level.”

- Clarity: Passengers are unlikely to spend more than a few seconds trying to extract information from a sign. Signs should be clear and comfortably legible from the distance at which the user is first likely to look for them. For complex displays, such as terminal maps, simultaneous use by several users should be considered. PANYNJ uses a custom typeface called Helvetica Now, which has been optimized for legibility in wayfinding.

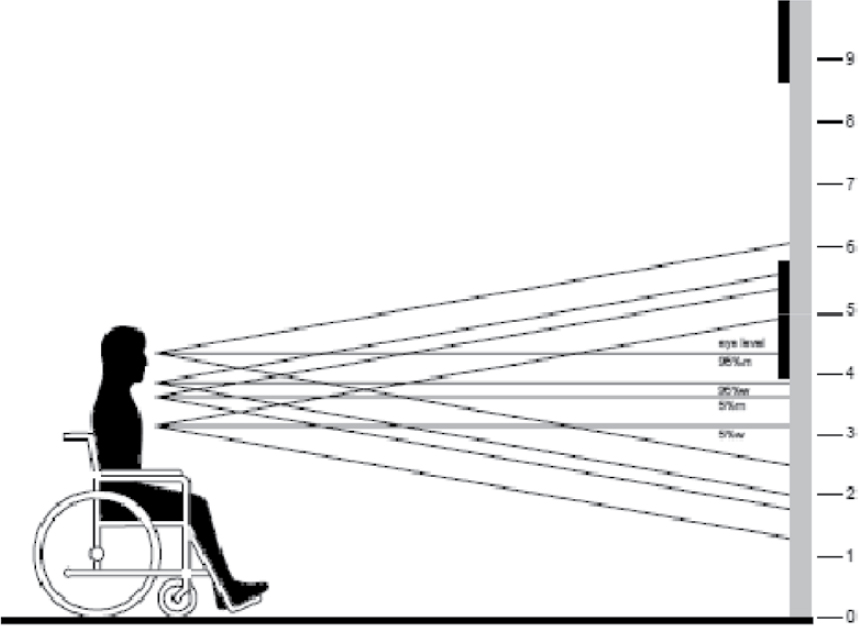

- Accessibility: The location of the sign should be accessible and take into consideration users with different needs. For example, designers should consider the various possible pathways to reach an area as well as the signage mounting height for a seated person and users in wheelchairs given the 10 degrees viewing angle from line of sight, as shown in Figure 18. Signs must be located at decision points where the user has the option of taking different paths, and signs should provide alternative route information for users with disabilities or other mobility requirements, such as making signage about elevators visible near stairs.

Inclusive design is about making services accessible to everyone by accounting for the needs of all users. PANYNJ’s inclusive design practices account for both different users and different abilities. PANYNJ divides user groups into foreign, families, assisted, senior, leisure, business, premium, connecting, drivers, visitors, meeters/greeters, and well-wishers and addresses visual, auditory, physical, cognitive, and language abilities.

Source: Harding et al. (2011)

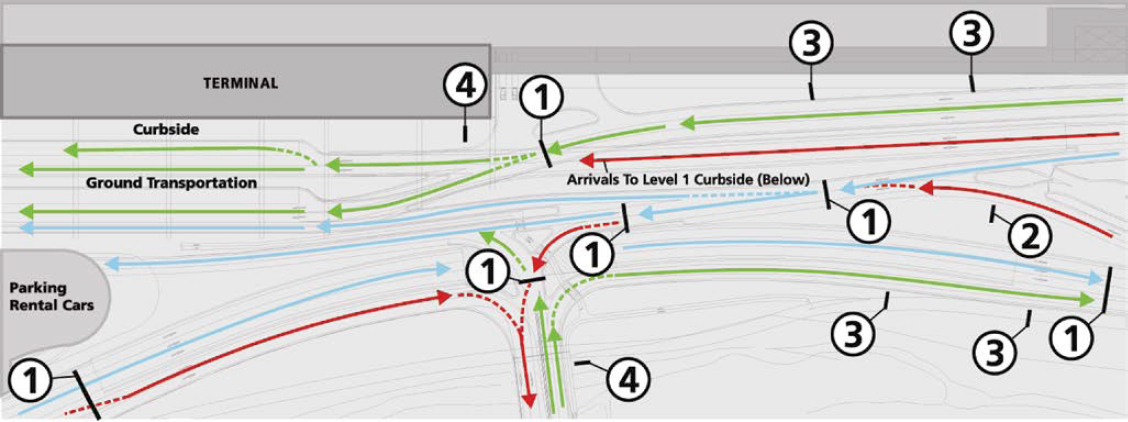

Giving Visibility to Mass Transit

Passengers should be able to access wayfinding information easily and accurately, so it is important to plan a consistent sign system for each route from roadway to gate and vice versa. By using circulation trees, airport planners can map out the expected passenger routing between the airport terminal and ground infrastructure; these routings can be used to determine wayfinding signage locations and distribution. For instance, a departure circulation tree should include passengers arriving by rental car, taxi, shuttle, mass transit, and other options specific to the airport. At first, passengers will search for different information, but ultimately, they will be searching for the same destination: the terminal. For an arrival circulation tree, users share an origin, but they will need signage to find the different transportation modes available and arrive at their specific destination.

Customers expect to have to find their way through the airport, so they will be looking for information that will guide them to the correct destination. Some airports use mass transit to reduce curbside congestion, which is only possible if mass transit offers are visible. An example of visible mass transit offers can be seen at John F. Kennedy International Airport (JFK), where the signs throughout the terminal use a specific background and foreground color combination to guide users to the AirTrain and other ground transportation, as shown in Figure 19; this pattern is also used at PANYNJ’s other airports.

Wayfinding Assistance from Doorstep to Terminal

ACRP Report 52 (Harding et al. 2011) describes consistency as the backbone of an airport wayfinding system. From the moment users enter an airport until they board a plane, information

should be presented in a uniform, consistent manner. This principle ties back to the primary objective of wayfinding: to give facilities a logical flow for passengers and to achieve coherent application of visual identity and design standards across all medias. Consistent presentation of information extends to other forms of communication as well, like maps, directories, applications, and websites. Communication itself, whether verbal or written, must be consistent so the public is not confused by different terms for the same concept.

Airports can work together with ground transportation providers, especially mass transit operators, to make sure that commuters and others traveling to and from their facility get adequate and consistent wayfinding information all along the journey. For instance, any discontinuity in the provided information due to a connection between two transit services that are operated by different entities, with their own design standards, should be addressed (e.g., place signage ahead of the next decision point or transition to new signage standards). Mass transit lines serving airports should provide clear visual indications of such service in trains and at stations that show which stop goes to the airport and next steps toward the final airport destination, if any (e.g., connection with people mover). Airplane pictograms are a simple, efficient, and universally recognized way to identify the airport station. When an airport name is too long to fit on a route map, designers may be tempted to use the airport’s three-letter FAA code instead. However, these codes are not always known by passengers, especially out-of-town visitors.

Transit authorities in metropolitan areas served by a multi-airport system should provide comprehensive and clear signage in stations. For instance, on the monolith depicted in Figure 20, it is not clear that only the Silver Line toward Ashburn serves Washington Dulles International Airport (IAD). Passengers who are not familiar with the Washington Metropolitan Area Transit Authority (WMATA) network might mistake the Orange Line toward Vienna-Fairfax-GMU for a service that stops at IAD. Also, the totem does not mention Ronald Reagan Washington National Airport (DCA), which is served by the Blue Line toward Franconia-Springfield.

Multilingual Wayfinding Assistance Options

Airports receiving foreign passengers may consider multilingual wayfinding assistance options to enhance accessibility and the overall passenger experience. Most U.S. international airports have their wayfinding signage in English only. Some large-hub airports (e.g., JFK and Miami

Source: Courtesy of Edward Russell

International Airport [MIA]) feature a Spanish language translation of select items of signage information.

One reason for the overall monolingual signage situation in our country could be that the English language has become a global lingua franca. For instance, Frankfurt Airport (FRA) in Germany has all its signage in both German and English because the airport intends to be a global hub, and less than 3 percent of the world’s population speaks German. Most international visitors coming to the United States understand at least some basic English. When combined with pictograms provided on the signs, most passengers can navigate airports and find their way; if not, most commercial service airports provide additional assistance, such as maps and help desks.

Consequently, U.S. airports do not face the same dilemma as some international airports located in non-English-speaking countries. However, offering multilingual wayfinding assistance can still enhance the passenger experience and improve the comfort of foreign passengers. This can be especially important for passengers in the context of airport access, particularly off-airport information that does not rely on the same terminology and pictograms, as well as mobility providers with applications that may not enable the same languages. Multilingual wayfinding can also target specific markets with a larger proportion of tourists who have more frequent difficulties with the English language. For instance, the terminal signage at both Paris Charles de Gaulle Airport (CDG) and Paris-Orly Airport (ORY) in France is available in French, English, and Simplified Mandarin Chinese.

Decision-making regarding the implementation of multilingual support can be informed by passenger surveys and market studies. When considering such a move, critical parameters will be the cost of the operation, technical feasibility, and implementation. While changing all physical signs may be a complex and expensive project, targeted interventions can also bring

more inclusion. In particular, enabling different languages on digital signage might be more straightforward than with traditional static signs. For example, the automated people movers (APMs) serving the various terminals and concourses of Hartsfield–Jackson Atlanta International Airport (ATL) have color video displays that provide system information on the platforms and inside the trains, with translations available in English, French, German, Spanish, Japanese, Chinese, Arabic, and Korean, as shown in Figure 21.

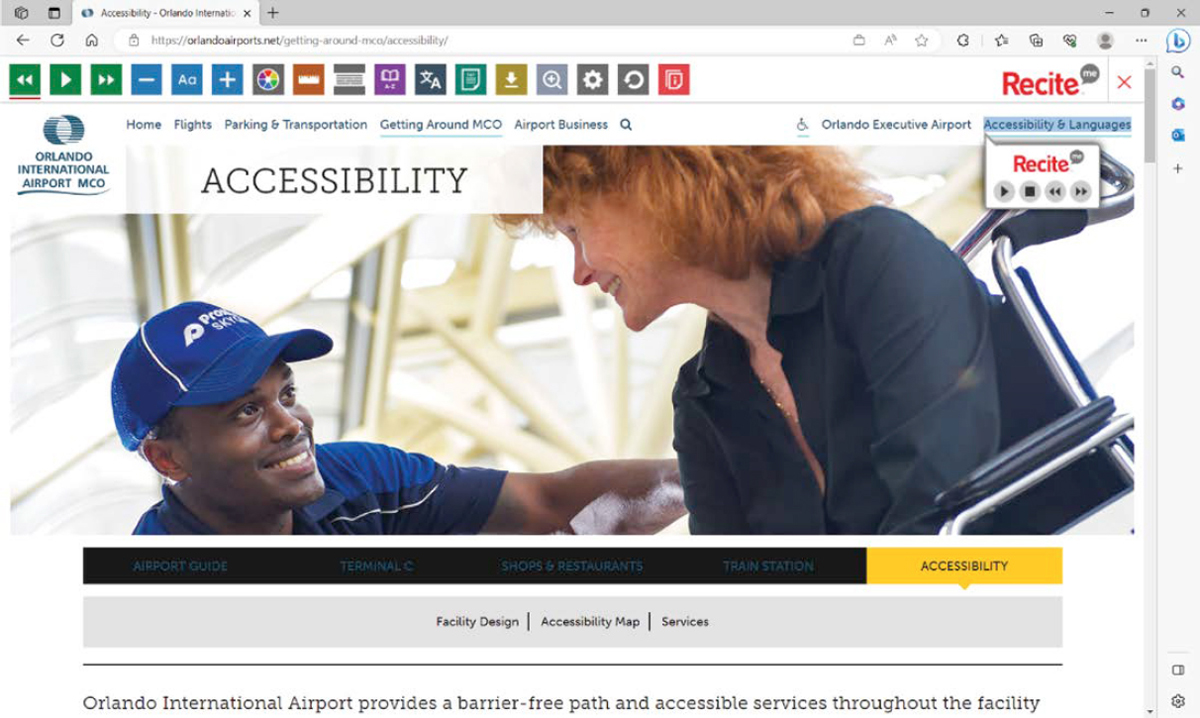

Also, websites and applications for mobile devices can be tremendously helpful for offering a multilingual experience with minimum cost and virtually no impact on operations (i.e., by updating an app or loading new content). This is an opportunity for airports to acknowledge the linguistic diversity of their passengers, especially with the broader dissemination of smartphones and airport apps that offer wayfinding tools (e.g., dynamic maps) to help users find their way throughout the facilities. For example, on the website for Orlando International Airport (MCO), clicking on the Accessibility & Languages tab will open a toolbar with accessibility options for users to customize their experience (e.g., text size and dictation tools) and also translate the website in about 100 different languages, as depicted in Figure 22. The mobile app provides contents in English, Arabic, French, German, Japanese, Portuguese, Simplified Mandarin Chinese, and Spanish. Leveraging these technologies will enable airports to follow the evolution of their passenger demographic and open new international routes without having to prepare for costly and complex upgrades to their physical signage.

Multilingual wayfinding information can serve domestic purposes as well. According to the 2006–2008 American Community Survey of over 280.6 million speakers who are at least 5 years old, 24.5 million respondents declared that they speak English “less than ‘Very Well’”—this included 16.1 million people speaking Spanish or a Spanish-Creole language at home. Spanish is by far the primary non-English language appearing on multilingual signage at U.S. airports.

Wayfinding assistance can be also a way to give visibility to local languages. For instance, while Native American communities are fully fluent in English, providing airport information in their Indigenous languages gives them visibility and helps preserve their culture and legacy.

Source: Hartsfield–Jackson Atlanta International Airport’s (ATL’s) Plane Train

Source: Orlando International Airport (MCO) (2023)

Moreover, languages that are not practiced in daily life are subject to rapid decline and can ultimately go extinct. According to the U.S. Census Bureau (2019), all Indigenous American languages but two (Eastern Keres and Central Yupik) are showing indications of demographic decline.

While English is the de facto lingua franca of the United States, there are approximately 430 languages spoken or signed across the country. In addition to the Indigenous languages of the Americas, other languages spoken in the United States should not be considered “foreign,” as they have a long and rich history on this land. In Louisiana, about 200,000 people speak French languages—for example, Louisiana French, Indian French, and Louisiana Creole. These languages are part of the state’s identity, and they are home languages of many communities, including tribal communities (e.g., United Houma Nation and Point-au-Chien).

Furthermore, local governments identify and recognize limited-English-speaking populations. They offer guidance and tools for providing accessible communications to limited-English-speaking populations in order to lift barriers to meaningful access of the information for all constituents.

While it is not possible for airports to translate all information into all languages across all media, digital materials and translation tools provide new capabilities. Artificial intelligence and machine learning are opening doors to further broaden the outreach, enable more languages, and lower the cost of multilingualism. These efforts can enhance the way airports connect with the complex web of communities flying through, working at, doing business with, and living near these facilities.

Leveraging Technologies for Enhancing Wayfinding

It is common for some passengers to have difficulty locating their destination by physical signage alone. Airports have developed many strategies and tools to support passengers in need, including airport ambassadors, digital maps, and personal help, as depicted in Table 9.

Digital applications for smartphones and other mobile devices can offer powerful alternatives for wayfinding. Airport apps can provide georeferenced information to guide users throughout the facility. Developers can make such functionalities customizable to deliver information in a format that fits the specific needs of user groups (e.g., people who are visually impaired). Also, apps can easily accommodate additional language options without the hurdle and cost of having to change all physical signage throughout the airport and with minimal impact on user experience (i.e., via app update). Finally, apps can be leveraged to develop strategies for using the airport’s wayfinding features that are tailored to specific user groups. For instance, an app could suggest lower-intensity pathways to people with hidden disabilities that can make navigating crowded areas challenging, such as agoraphobia or certain forms of autism.

Applications can also provide information on the airport access options available—such as their location at the airport—as well as pricing, availability, congestion level, disruptions, and more. Furthermore, an airport app could either redirect to the website or app of the mobility provider or integrate these offers with a mobility-as-a-service (MaaS) approach to enable trip-planning and booking.

Table 9. Wayfinding Assistance Options at Airports

| Wayfinding Assistance | Key Features |

|---|---|

| Physical signs |

|

| Digital signs |

|

| Public address systems |

|

| Airport ambassadors |

|

| Wheelchair and guided assistance |

|

| Digital apps |

|