Ending Unequal Treatment: Strategies to Achieve Equitable Health Care and Optimal Health for All (2024)

Chapter: 7 Discovery and Evidence Generation

7

Discovery and Evidence Generation

The past 2 decades have witnessed important shifts in equity research, with a significant increase in the number of researchers involved, grants awarded, and publications. In addition, the tools and resources have evolved (Boulware et al., 2022; Brown et al., 2019). A growing body of evidence continues to document racial and ethnic health care inequities across many conditions. Yet, the promise of health equity research, especially the discovery of successful interventions, has yet to be fully realized for myriad reasons. Advancing health equity will require major investment in research project funding, workforce, data, and infrastructure. This chapter discusses aspects of the health care equity research landscape, including the state of those four factors. It ends with a summary of some potential areas where further efforts are needed. As noted in previous chapters, the committee is aware that health—a state of complete physical, mental, and social well-being and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity—and health care—the services provided to individuals, families, and communities for the purpose of promoting, maintaining, or restoring health across settings of care—are different but inextricably linked. Therefore, this report uses “health care system” (activities related to the delivery of care across the continuum of care) to describe the U.S. health care system as a whole and individual health care systems and “health” when discussing outcomes.

ADVANCING HEALTH EQUITY RESEARCH

Historically, biomedical research has not focused on addressing health care inequities and advancing health equity. Health disparities and health equity topics have not been prioritized compared to other research topics

(Hoppe et al., 2019). For decades, health equity topics have been undervalued and underfunded, and this disproportionately affects researchers from minoritized racial and ethnic groups, who are more likely to propose health equity topics compared to their White counterparts (Chen et al., 2022; Hoppe et al., 2019). Furthermore, academic research enterprises have not incentivized the activities associated with health equity research, especially community engagement and community-based endeavors, which require long-term investments, demonstrating trustworthiness, and engaging individuals who have lived experience with inequities, and collaborating with health care settings based in communities (Boulware et al., 2022; Griffith et al., 2020; Wilkins and Alberti, 2019).

Advancing the field of health equity research requires acknowledging the research abuses that racially and ethnically minoritized groups have experienced and additional efforts to repair and demonstrate trustworthiness. Historical and ongoing research mistreatment are well documented, and the toll on racially and ethnically minoritized people is difficult to quantify (Garrison, 2013; Heart and Chase, 2016; Scharff et al., 2010; Skloot, 2017; Washington, 2006). Unfortunately, researchers and research institutions often fail to acknowledge these harms or distance themselves without recognizing the further marginalization of these communities. These scientific and medical injustices continue to occur. For example, research has shown that racial bias in pulse oximetry has negatively impacted Asian, Black, and Hispanic patients (Sjoding et al., 2020; Valbuena et al., 2022); and algorithmic bias has resulted in White people receiving greater access to health care than Black people who were sicker (Geneviève et al., 2020; Obermeyer et al., 2019). Progress in health equity research requires viewing equity as a fundamental goal, not an afterthought, of all health-related research (Lett et al., 2022; Wailoo et al., 2023). To address inequities, research needs to also acknowledge the impact of scientific racism, including the role of scientists and health professionals in using eugenics and creating flawed systems of categorizing people (Davis, 2021; Jackson et al., 2005).

HISTORICAL AND CURRENT HEALTH EQUITY RESEARCH FUNDING

NIH Health Equity Research Funding

From 2004 to 2023, the total direct costs for all research topic awards by NIH to improve the health of the nation totaled over $352 billion in direct costs. Out of this amount, the total direct cost for awards that used projects terms such as “health equity,” “health inequity,” “health inequities,” “health disparity,” or “health disparities” totaled about $15 billion (see Table 7-1).

| Administering Institute or Center | Total Direct Costs for Health Equity Related Awards | Number of Health Equity Projects | Total Direct Costs for All Topics Awards | Percentage of Budget Awarded to Health Equity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NCI | $3,633,196,443 | 7,036 | $50,726,900,420 | 7.2 |

| NEI | $27,120,902 | 85 | $8,381,334,414 | 0.3 |

| NHLBI | $1,051,514,037 | 2,799 | $39,092,240,320 | 2.7 |

| NHGRI | $203,935,010 | 409 | $6,373,526,235 | 3.2 |

| NIA | $1,327,904,762 | 2,595 | $24,210,131,963 | 5.5 |

| NIAAA | $182,132,345 | 679 | $5,476,135,533 | 3.3 |

| NIAID | $258,907,649 | 408 | $49,344,168,010 | 0.5 |

| NIAMS | $46,012,673 | 205 | $6,441,219,915 | 0.7 |

| NIBIB | $67,322,688 | 88 | $4,521,320,123 | 1.5 |

| NICHD | $671,550,878 | 2,519 | $15,402,249,730 | 4.4 |

| NIDCD | $40,502,284 | 148 | $5,073,980,391 | 0.8 |

| NIDCR | $231,472,970 | 575 | $4,815,559,200 | 4.8 |

| NIDDK | $429,132,793 | 1,578 | $24,483,467,647 | 1.8 |

| NIDA | $596,265,144 | 1,763 | $14,274,619,347 | 4.2 |

| NIEHS | $302,245,040 | 702 | $2,692,726,097 | 11.2 |

| NIGMS | $1,023,448,278 | 1,596 | $33,506,241,573 | 3.1 |

| NIMH | $578,335,226 | 1,660 | $19,560,578,914 | 3.0 |

| NIMHD | $2,728,565,462 | 4,782 | $3,870,222,116 | 70.5 |

| NINDS | $171,692,885 | 296 | $22,640,507,803 | 0.8 |

| NINR | $244,052,667 | 1,079 | $1,855,582,023 | 13.2 |

| NLM | $51,917,677 | 265 | $1,036,060,501 | 5.0 |

| FIC | $25,809,223 | 192 | $1,103,031,702 | 2.3 |

| NCATS | $1,043,275,287 | 473 | $5,633,108,052 | 18.5 |

| NCCIH | $30,549,993 | 163 | $1,587,586,575 | 1.9 |

| Total | $14,966,862,316 | 32,095 | $352,102,498,604 | 4.3 |

NOTES: The health equity funding in this table includes funding for health-equity-based research, program project/center, and resource grants. NCI: National Cancer Institute; NEI: National Eye Institute; NHLBI: National Heart: Lung, and Blood Institute; NHGRI: National Human Genome Research Institute; NIA: National Institute of Aging; NIAAA: National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism; NIAID: National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases; NIAMS: National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases; NIBIB: National Institute of Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering; NICHD: Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development; NICDC: National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders; NIDCR: National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research; NIDDK: National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases; NIDA: National Institute on Drug Abuse; NIEHS: National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences; NIGMS: National Institute of General Medical Sciences; NIMH: National Institute of Mental Health; NIMHD: National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities; NINDS: National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke; NINR: National Institute of Nursing Research; NLM: National Library of Medicine; FIC: Fogarty International Center; NCATS: National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences; NCCIH: National Center For Complementary and Alternative Medicine. The following NIH institutes and centers did not have data meeting the topic and year search parameters used in the NIH RePORTER: Clinical Center, Center for Information Technology, and Center for Scientific Review. NCATS only had data available starting 2012, as it was established in 2011.

SOURCE: NIH RePORTER Database.

BOX 7-1

NIH Research Funding Methodology Using NIH RePORTER

The committee used NIH RePORTER, an online database to determine the proportions of funding for health equity research. It used the “Text Search” option, which allows for “Project Terms” instead of “health disparities” as a spending category to show the trend in health equity funding. “Health Disparities” only captures data starting at 2020. Specifically, the advanced project search conducted in RePORTER included fiscal years (FYs) 2004–2023 for the project terms “health equity,” “health inequity,” “health inequities,” “health disparity,” or “health disparities” for all NIH institutes and centers (ICs). Search results were exported into Excel along with optional variables (activity code, direct cost IC, funding IC, FY, project terms). Because a maximum of 15,000 projects can be downloaded from RePORTER each time, over 150 Excel files were downloaded and combined.

Some projects may be funded for more than one year and by more than 1 IC. Steps were taken to avoid double counting. For example, a project funded for 3 years appears three times in the dataset. The direct cost was assigned to each IC for each FY. For projects funded by more than IC, the proportion of direct cost provided by each IC was identified and assigned to the IC.a

__________________

a On May 14, 2024, NIH published an update to its minority health and health disparities research, condition, and disease categorization categories. (See https://www.nimhd.nih.gov/about/directors-corner/messages/nih-improves-minority-health-and-health-disparitiesreporting.html; accessed on May 15, 2024.)

(See Box 7-1 for how the NIH RePORTER1 was used to evaluate the funding discussed in this chapter).

The National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities (NIMHD), that leads scientific research to improve minority health and eliminate health disparities,2 funded over 4,700 projects at nearly $2.8 billion. Of the ICs and offices with the highest percentages of these health equity awards, NIMHD, National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, and the National Institute on Nursing Research fund a larger proportion

___________________

1 RePORTER is a dynamic database that is updated weekly. Updates include the addition of new projects as well as revisions to prior awards, which may prevent an exact replication of the data used in this report.

2 See https://www.nih.gov/about-nih/what-we-do/nih-almanac/national-institute-minority-health-health-disparities-nimhd (accessed March 29, 2024).

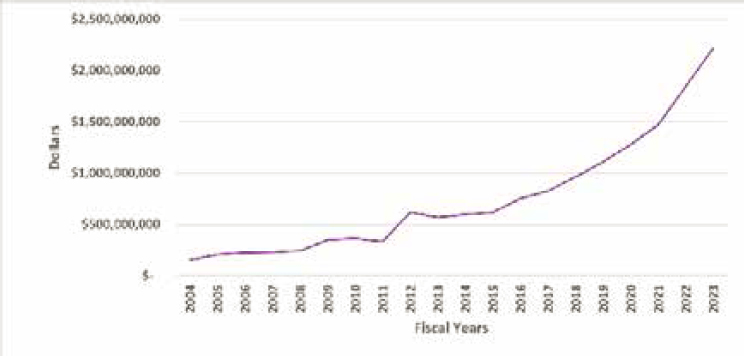

NOTE: The health equity funding represented in this figure includes funding for health equity-based research projects (R), research program projects and centers (P), cooperative agreements (U), fellowship programs (F), research career development programs (K), institutional training program (T), research-related programs, (S) resource programs (G), research construction programs (C) institutional training and director program projects (D), and other transactions (O).

SOURCE: Data from this figure were retrieved from https://reporter.nih.gov/.

of such awards relative to their total budgets, 70.5, 18.5, and 13.2 percent, respectively. Seventeen out of the 27 NIH ICs dedicate less than 5 percent of their budgets to health-equity-related research.

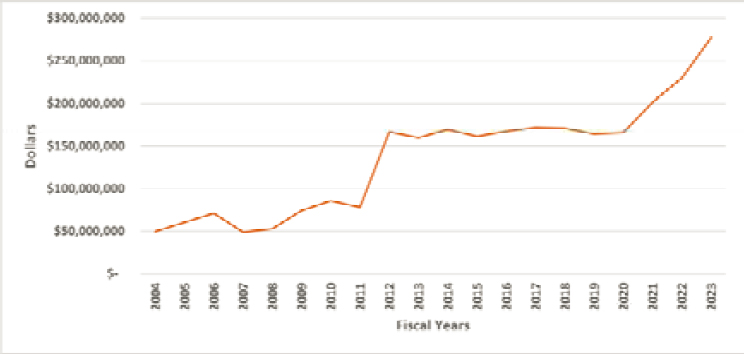

Over time, NIH’s commitment to funding health-equity-related research has increased but is still low relative to the total direct costs for all other research topics. From 2004 to 2011, the funding increased slowly, and then quickly from 2011 to 2012. There was a slight decrease from 2012 to 2013 and a gradual increase after 2013 (see Figure 7-1). NIMHD’s funding also fluctuated until 2011 and then increased sharply from 2011 to 2012. From 2012 to 2020, it remained steady, before increasing again from 2020 to 2023 (see Figure 7-2).

Health Equity Funding from Other Department of Health and Human Services Agencies and Nongovernmental Organizations

Over the past 2 decades, funding from other HHS agencies, philanthropic organizations, and other federal agencies toward health equity has increased substantially (Aluko et al., 2023). These investments have been more broadly devoted to health equity and not necessarily research. The Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality and PCORI have launched a

NOTE: The health equity funding represented in this figure includes funding for health equity-based research projects (R), research program projects and centers (P), cooperative agreements (U), fellowship programs (F), research career development programs (K), institutional training program (T), research-related programs (S) resource programs (G), research construction programs (C) institutional training and director program projects (D), and other transactions (O).

SOURCE: Data from this figure were retrieved from https://reporter.nih.gov/.

5-year, $80 million initiative to train researchers and scientists to conduct system-focused research to advance health equity and enhance workforce diversity.3 Similarly, the Office of the National Coordinator for Health Information Technology, through its Public Health Informatics & Technology Workforce Development Program, has awarded over $75 million in cooperative agreements to strengthen public health information technology efforts, improve COVID-19 data collection, and increase representation of underrepresented communities within that workforce.4 In 2023 alone, the Health Resources and Services Administration awarded over $13.1 billion in grants to improve and expand health care services for underserved people, focusing on areas such as primary care, health workforce training, maternal and child health and rural health.5 Moreover, several nongovernmental organizations have also made significant investments in health equity (Aluko et al., 2023).

___________________

3 See https://www.ahrq.gov/sites/default/files/wysiwyg/cpi/about/health-equity/health-equity-factsheet.pdf (accessed March 29, 2024).

4 See https://www.healthit.gov/topic/interoperability/investments/public-health-informatics-technology-phit-workforce-development (accessed March 29, 2024).

5 See https://data.hrsa.gov/topics/grants (accessed March 29, 2024).

THE RESEARCH WORKFORCE

Lack of Diversity in the Health Equity Research Workforce

Racial and ethnic diversity among the nation’s scientific research faculty remains low at 4 percent African American, 4 percent Hispanic, 0.2 percent Native American, and 0.1 percent Hawaiian/Pacific Islander (Valantine and Collins, 2015). Despite recent gains in the diversity of biomedical graduate students and postdoctoral fellows, few minoritized researchers are becoming faculty members (Gibbs Jr. et al., 2016; Meyers et al., 2018). At current rates, faculty diversity would not improve significantly until 2080 (Gibbs Jr. et al., 2016). Systemic issues related to faculty hiring, retention, and promotion maintain homogeneity among the faculty at the expense of increasing diversity (Gibbs Jr. et al., 2016; Sensoy and DiAngelo, 2017). Other factors contributing to the underrepresentation and exclusion of individuals from racially and ethnically minoritized groups include passive recruitment strategies, bias in evaluations, insufficient start-up funding, and inadequate mentoring. Systemic racism also contributes to isolation, marginalization, delayed promotion, inequities in compensation, and inequities in NIH funding (Davies et al., 2021; Gibbs Jr., 2014; Whittaker et al., 2015).

Unclear Standards and Criteria for Defining the Health Equity Research Workforce

The COVID-19 pandemic shone a bright light on racial and ethnic health inequities (NASHP, 2021). Along with the increased awareness and additional funding opportunities came new researchers with limited, if any, training, experience, or commitment to health equity. This phenomenon of “health equity tourism” has led to calls for establishing standards, competencies, and training for research in health equity (Lett et al., 2022). For example, health equity research competencies should include mastering the skills needed to meaningfully engage communities experiencing health inequities, identify and integrate social and structural drivers of health frameworks into study design, and employ equity-focused analytic approaches (e.g., analysis does not require a White control or comparison group).

Funding researchers who are ill-prepared and untrained to conduct health equity research has numerous consequences. “Without an appreciation of these challenges, ‘tourists’ are at risk of polluting the health equity landscape and riddling the academic record with ineffectual, and potentially harmful studies that mischaracterize root causes of health inequities and obfuscate potential solutions” (Lett et al., 2022). In

addition to potentially harmful science, the influx of new researchers pivoting from other topic areas could outnumber and further marginalize health equity researchers who have been conducting research on inequities for decades with limited funding opportunities. Although the new competition for health equity research funds might be presumed to increase the quality of the resulting science, scientific review committees may be overwhelmed with new proposals and lack specific criteria for appropriately assessing them.

Supporting the Health Equity Research Workforce

Increasing Diversity in the Future Health Equity Research Workforce

Increasing the diversity of the research workforce has been a long-standing challenge, and lack of progress negatively affects innovation, scientific discovery, and ultimately public health (Hofstra et al., 2020). In September 2021, NIH Common Fund announced the initial set of awards in the Faculty Institutional Recruitment for Sustainable Transformation program.6 This program aims to help research institutions become more inclusive and diverse by using a cohort or cluster model for hiring faculty. Focused specifically on early-career, tenure-track faculty committed to inclusive excellence, it offers multilevel mentoring and professional development opportunities to change the culture of research institutions. Each awardee must establish integrated, institution-wide systems to address bias, faculty equity, mentoring, and work–life issues and work with the NIH-funded Coordination and Evaluation Center for independent program evaluation of the effect at the faculty and institutional level. In the first three rounds of awards, the program issued more than $150 million.7 Although the program is not solely focused on health equity, several awardees have identified that as a theme for faculty recruitment.

Training the Future Health Equity Research Workforce

Many colleges, universities, and research institutions lack the resources and infrastructure required to train researchers in the conceptual models, frameworks, study design, engagement strategies, and analytic approaches required to conduct health equity research (Lett et al., 2022). Generally, Historically Black Colleges and Universities are less funded compared to

___________________

6 See https://commonfund.nih.gov/FIRST (accessed March 29, 2024).

7 See https://commonfund.nih.gov/FIRST/highlights (accessed March 29, 2024).

others (Joseph et al., 2023). Overarching priorities for training the health care workforce on social determinants of health (SDOH) was discussed in Chapter 5 of this report. Many aspects of these priorities also apply to the training of the future cadre of health equity researchers and scholars. In addition, health equity researchers need training and experience in several foundational areas:

- understanding and applying social determinants frameworks and models to research study design,

- using research techniques and tools that measure inequities and social disadvantages

- developing interdisciplinary or transdisciplinary research collaborations that engage and partner with communities affected by health inequities, and

- developing approaches that center the voices and needs of marginalized and minoritized groups.

Fundamental Methods to Conducting Health Equity Research

Focus on Social Drivers

As discussed throughout this report, a large body of research describes the inequitable distribution of health and health care outcomes across the U.S. population and the characteristics of groups affected by health inequities in terms of race and ethnicity, income, education, socioeconomic status, community and housing conditions, access to health care, insurance status, and other demographic classifications. However, more research is needed to establish the unique mechanisms through which these influences affect health in specific communities and develop evidence regarding effective programs and interventions to reduce harmful social drivers and their effects on health. To meaningfully address health and health care inequities, research should be grounded in and include SDOH frameworks and researchers be trained in the principles of community engagement and cultural humility (Ovbiagele et al., 2023).

Tools That Assess and Address Social Disadvantage

Discovering interventions that successfully eliminate health and health care inequities requires unique tools and resources to understand socially disadvantaged populations and address SDOH. For example, researchers should understand how to define and collect self-identified

race and ethnicity data and how and when it is appropriate to use race and ethnicity to stratify data. Health equity researchers need to measure key drivers of racial and ethnic health inequities, such as racism, and be knowledgeable about and experienced in developing and using such measurement tools (Carlos et al., 2022; Dean and Thorpe, 2022). They also require training in equity-centered study design and antiracism (Wilkins et al., 2023).

Interdisciplinary and Transdisciplinary Research

Health research and health care delivery remain characterized by siloed specialty areas. However, it has become increasingly evident that the persistent health and health care inequities are driven by dynamic, multilevel factors that operate through social, political, economic, behavioral, and biological mechanisms. To more effectively address these multilevel and multidimensional mechanisms, collaborative health equity research across a wide range of disciplines is needed; teams need to include individuals from diverse scientific backgrounds and be adept at partnering with communities using mutually respectful, bidirectional strategies.

Centering the Needs and Perspectives of Minoritized Groups

Health equity research requires researchers to develop and continuously refine their health equity lens, which needs to be grounded in justice. Developing an equity lens is tied intrinsically to the researcher’s identity and lived experience, and using and refining it requires self-awareness, humility, and acknowledging one’s positionality (Lett et al., 2022). Health equity researchers benefit from training and experience in approaches that recognize power and privilege and elevate the voices of those often left behind. Several training programs are designed to enhance scholars’ knowledge, skills, and networks in health equity. The majority of these provide opportunities to supplement individual research training and require researchers to actively apply to enroll in the program. Table 7-2 offers examples of health equity research training programs designed for professionals across various career stages.

TABLE 7-2 Examples of Health Equity Research Training Programs by Career Stage

| Program Type | Program Title and Institution | Program Focus | Eligibility |

|---|---|---|---|

| Any Career Stage | |||

| Specialization program | Social Determinants of Health: Data to Action, University of Minnesota8 |

|

Open to the public |

| Trainee program | Center for Health Equity Trainee Program, Johns Hopkins University, Center for Health Equity9 |

|

Open to trainees across all levels of experience, including high school students, undergraduate and graduate students, post-docs, and early-, mid-, and late-career faculty |

| Health Professional Trainees | |||

| T37 training program | T37 Minority Health and Health Disparities Research Training Program, University of Miami, School of Nursing & Health Studies10 |

|

Open to undergraduate, graduate, and postgraduate nursing, public health, health sciences, or students from other disciplines interested in health inequities research |

| Certificate program | Certificate in Health Disparities and Health Equity Research, New York University, Grossman School of Medicine11 |

|

Open to NYU Langone–affiliated health care professionals, including dental, medical, and nursing school trainees and faculty, and individuals from other institutions affiliated with NIH Clinical and Translational Science Awards |

___________________

8 See https://online.umn.edu/social-determinants-health-data-action (accessed February 19, 2024).

9 See https://publichealth.jhu.edu/center-for-health-equity/what-we-do/education-and-training/trainee-program (accessed February 19, 2024).

10 See https://mhrt.sonhs.miami.edu/ (accessed March 29, 2024).

11 See https://med.nyu.edu/departments-institutes/clinical-translational-science/education/certificate-training-programs/certificate-health-disparities-health-equity-research (accessed March 29, 2024).

| Program Type | Program Title and Institution | Program Focus | Eligibility |

|---|---|---|---|

| Doctoral/Postdoctoral Researchers | |||

| Early-career training institute | Health Disparities Research Institute, National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities12 |

|

Open to early-stage investigators who have completed their postgraduate clinical training or terminal degree within the past 10 years; hold a position as a postdoctoral fellow, assistant professor, or comparable research position, and are planning to submit an F, K, or R01 grant to NIH within the next 12 months |

| Early-career training program | Global Alliance for Training in Health Equity Research Program, Drexel University, Dornsife School of Public Health13 |

|

Open to doctoral and postdoctoral researchers (requirement: identify as belonging to an NIH-designated health inequities population) |

HEALTH EQUITY RESEARCH DATA

Current State of the Data

Inaccurate and Incomplete Race, Ethnicity and Tribal Affiliation Data

The U.S. Office of Management and Budget (OMB) first developed standardized classification categories for race and ethnicity (SPD 15) in the 1977 to provide consistent data on race and ethnicity for federal statistical, administrative, and compliance reporting. The impetus for creating them arose, in large part, from new federal responsibilities for monitoring and enforcing civil rights laws.14 The standard defined racial categories as American Indian or Alaskan Native, Asian or Pacific Islander, Black, and White and defined the ethnic categories as Hispanic origin and not of Hispanic origin. OMB revised these categories in 1997. The “Asian or Pacific

___________________

12 See https://www.nimhd.nih.gov/programs/extramural/training-career-dev/hdri/ (accessed March 29, 2024).

13 See https://drexel.edu/dornsife/global/global-health-training/gather/ (accessed March 29, 2024).

14 See https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2016/09/30/2016-23672/standards-for-maintaining-collecting-and-presenting-federal-data-on-race-and-ethnicity (accessed March 29, 2024).

Islander” racial category was separated into two racial groups: “Asian” and “Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander.” Two major limitations of the categories were that they obscure substantial heterogeneity within each of these groups, and many individuals do not identify with these broad options, which results in potentially missing and/or erroneous data (NASEM, 2023a; Pellegrin et al., 2016).

To address these concerns, on March 28, 2024, OMB released a revised standard for federal agencies on maintaining, collecting, and presenting data on race and ethnicity.15 It will require race and ethnicity data to be collected using a single question with multiple responses. Hispanic or Latino will be listed as one race/ethnicity category, replacing the requirement to collect Hispanic ethnicity as a separate question. Moreover, the revision adds Middle Eastern or North African (MENA) as a minimum reporting category. The revised standard has seven minimum race/ethnicity categories: American Indian or Alaska Native, Asian, Black or African American, Hispanic or Latino, MENA, Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander and White. It will also require federal agencies to collect more detailed race, ethnicity, and tribal affiliation information beyond the seven minimum reporting categories.

Concerns About How Data Are Organized and Reported

Although a number of federal surveys collect race and ethnicity data that are more granular than the minimum standards, concerns with both the current and newly revised OMB standards lie in not only how the data are collected but also how they are reported (NASEM, 2023b). Even when more granular data are collected, these are often collapsed into the minimum categories for reporting. OMB provides guidelines on how these more granular data should be handled, but these recommendations are subjective and often do not reflect individual self-identities (Holup et al., 2007; Maghbouleh et al, 2022). Furthermore, although OMB requires federal agencies to use the minimum reporting categories for both data collection and reporting, certain categories are still often combined or aggregated in reports due to small sample sizes.

Other national surveys have small sample sizes for certain minoritized populations (especially those identifying as American Indian or Alaska Native (AIAN) and Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander [NHPI]) lead to the data being collapsed into nonspecific and arbitrary categories, such as “other,” or even omitted entirely (Friedman et al., 2023; NASEM, 2023b). The 2023 NASEM report Federal Policy to Advance Racial, Ethnic, and Tribal Health Equity notes that omitting these data “perpetuates inequities

___________________

15 See https://www.federalregister.gov/public-inspection/2024-06469/statistical-policy-directive-no-15-standards-for-maintaining-collecting-and-presenting-federal-data (accessed March 29, 2024).

and promotes inaction—particularly when people are invisible in federal datasets” and that data on smaller minimum OMB categories are often biased due to “incomplete representation, poorly designed sampling frames, inadequate collection approaches, language barriers (including failure to administer instruments in a person’s primary language), and culturally inappropriate question design.” Additionally, the federal definition of AIAN is limited to those registered in federally recognized Tribal Nations, which leads to further underestimation and misclassification (NASEM, 2023b). Dedicated federal funding is needed to support more robust survey sampling for certain minoritized populations to ensure equitable representation of these populations in national surveys.

Data Complexities

Substantial complexities also exist regarding how best to tabulate and present data for those individuals reporting more than one race, which in the 2020 Census represented roughly 10 percent of the U.S. population, a 276 percent increase from 2010 (Jones et al., 2021). OMB recommends providing a detailed breakdown of multiple race responses whenever possible; if data are collapsed, at a minimum, the total number of respondents reporting “more than one race” needs to be provided. Researchers and subject matter experts have expressed concerns that collapsing more than one race into a single nonspecific category obscures vast heterogeneity (Rubin et al 2018; Zambrana et al., 2021). Furthermore, with this approach, over half of the population of those who identify as AIAN and NHPI would be assigned to the “two or more races” category, which would have the unintended consequence of driving down or masking critical tabulation of and accounting for these smaller, historically marginalized populations.16 A third potential approach, allowable since the 1997 revision to the current standard, involves reporting all of those who identify with a given racial group “alone or in combination” with one or more other races. A respondent who reports being both White and Black or African American would be categorized as both “White alone or in combination” and “Black or African American alone or in combination.” A 2022 OMB Memorandum on flexibilities and best practices for implementing the current standard notes that the best approach in a given situation depends on the objective of analyses, sample size, and whether prior reporting approaches need to be maintained to assess temporal trends.17

___________________

16 See https://www.whitehouse.gov/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/Flexibilities-and-Best-Practices-Under-SPD-15.pdf (accessed March 29, 2024).

17 See https://www.whitehouse.gov/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/Flexibilities-and-Best-Practices-Under-SPD-15.pdf (accessed March 29, 2024).

Strategies for Improving Data and Data Infrastructure

Need for Granular Race and Ethnicity Data

Although much of the spotlight on data has focused on collecting a minimum dataset, the racial and ethnic categories are tied to continents, and the populations are heterogenous, reflecting many different cultures and backgrounds. For example, people of Asian descent represent 60 percent of the world’s population, and those who might identify as Asian/Asian American could be Chinese, Indian, Filipino, or from dozens of Asian subgroups (McFarling, 2023). Failure to collect and use detailed or granular race and ethnicity data masks meaningful subgroup differences and renders populations becoming invisible (Islam et al., 2010). The use of broad racial and ethnic categories impacts Latino/a, Black, AIAN, Asian, NHPI, and White populations (Alcántara et al., 2021; Becker et al., 2021; Larimore et al., 2021; Read et al., 2021; Shimkhada et al., 2021). Presumed homogeneity within these broad categories limits the ability to identify and address population- and community-level inequities and reinforces false narratives that the social category of race is tied to innate biological and genetic differences (Davis, 2021).

Detailed accurate data on Hispanic/Latino/a, Asian, Pacific Islander, Black/African American, and AIAN subgroups are needed across the full spectrum of socioeconomic status to understand and address health inequities (IOM, 2006; NASEM, 2023b). Unfortunately, few studies collect detailed racial and ethnic data about subgroups. One example is All of Us, NIH’s precision medicine program, which intends to enroll at least one million people.18 It provides the opportunity to select from eight or more subgroups in each racial and ethnic group and indicate Tribal affiliation. This approach allows individuals to select both broad categories and subgroups, and multiple groups can be selected to more accurately reflect the increasing number who identify as multiracial and multiethnic.

Datasets Capturing Social Determinants, Drivers, and Needs Data

As highlighted throughout this report, understanding and addressing social factors is critical to addressing racial and ethnic health and health care inequities. National Academies reports have recommended systematically collecting social, economic, and historical data to provide context and understanding for these inequities. Unfortunately, progress has been slow and inconsistent. In May 2020, 19 SDOH protocols were added to the PhenX toolkit to facilitate collecting SDOH data using common

___________________

18 See https://allofus.nih.gov/ (accessed March 29, 2024).

measurements (Krzyzanowski et al., 2023). Since then, additional individual- and structural-level protocols have included collecting data on race, ethnicity, gender identity, income, English proficiency, access to care, housing stability, and discrimination.

Opportunities for data linkages across administrative and national survey data

The Census Bureau’s Enhancing Health Data (EHealth) Program19 is developing novel linkages between Census datasets and federal and external administrative health data to address sociodemographic and economic data gaps in administrative health data, including for Medicaid and Medicare. The National Center for Health Statistics has also linked several national surveys to Medicare and Medicaid20 enrollment and claims records data, but opportunities for such linkages remain underused and could be supported further with NIH and CMS funding. The Medicaid and CHIP Payment and Access Commission has additionally recommended that CMS field an annual Medicaid beneficiary survey21 to collect information on beneficiary perceptions and experiences with care. Such a survey would also allow for collecting beneficiary-reported race and ethnicity, which could be used to validate and improve the quality of race and ethnicity data in Medicaid administrative datasets.

Improving Data and Methods for Measuring Racism

Increasing recognition of the role of racism on influencing health care and health outcomes has highlighted a gap in the understanding of how to measure racism. A 2023 review of studies published from 1992 to 2022 examining race and racial inequities identified 63 reporting approaches for personally mediated racism, internalized racism, structural racism, and the multiple integrated measures to encompass racism (Wizentier et al., 2023). Through these four domains, more than 60 different measures for identifying racism are identified. Types of racism covered include implicit bias, explicit bias, institutional discrimination, spatial segregation, and redlining practices. The authors conclude that racism measurement does not always fit into a single category, and they advocate for methodological triangulation to better capture multiple perspectives. A 2018 review identified 20 papers with quantitative methods for measuring structural racism (Groos et al., 2018), which primarily focused on housing, residential segregation, criminal justice, immigration policies, perceived racism, and political participation.

___________________

19 See https://www.census.gov/programs-surveys/ehealth.html (accessed March 29, 2024).

20 See https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data-linkage/medicaid.htm (accessed March 29, 2024).

21 See https://www.macpac.gov/wp-content/uploads/2022/06/Chapter-1-A-New-Medicaid-Access-Monitoring-System.pdf (accessed March 29, 2024).

In addition to broader use of measures of racism in research, new tools are needed to measure structural racism that reflect the multifaceted ways that a culture of White supremacy operates and maintains systems of oppression (Hardeman et al., 2022).

HEALTH EQUITY RESEARCH INFRASTRUCTURE

Current State of Health Equity Research Infrastructure

In addition to accurate and complete data and data infrastructure resources, health equity researchers require infrastructure to support high-quality research, which is analogous to the brick-and-mortar laboratories provided for basic science research. These are the resources required to build and sustain long-term relationships with community partners to ensure that research is relevant and responsive to community needs. These resources are needed to rebuild trust with minoritized communities who have suffered research abuses and lost faith in the research enterprise (and the health care enterprise, in many cases). This infrastructure can sometimes be difficult to define and quantify; however, these challenges do not make it any less essential to conducting the science that is needed to advance health equity.

No Continued Support to Build and Sustain Long-Term Relationships with Community Partners

When health equity researchers are funded by NIH and others, they bring the same indirect rate to their academic institution as scientists funded on other areas of science; yet there are often no tangible ways to see and measure the indirect investments being made to provide ample health equity research infrastructure. The resources supporting the establishment of community-partnered and -centered initiatives across the academic enterprise are also widely variable. Building and funding this infrastructure is often believed to be the responsibility of individual investigators, which is not the case with laboratory buildings and equipment supported by shared resources and central offices. The lack of sustained, community-based infrastructure for health equity research is also concerning given that patients in academic health centers do not represent the general population (Giusti et al., 2021). Successful models exist to build infrastructure in community settings and in partnership with community members. One potential model is a practice-based research network (PBRN) (Davis et al., 2012; Getrich et al., 2013; Tierney et al., 2007; Westfall et al., 2007). PBRNs are most often made up of community-based primary care practices working together to ask and answer questions that come from patients, clinicians, and policy makers in local communities. They are instrumental in translating research into community practice (evidence-based practice) and ensuring that it is

relevant to community practice (practice-based evidence). PBRNs are made up of clinics on the front lines of care delivery who are acutely aware of health (Davis et al., 2012; Getrich et al., 2013; Westfall et al., 2019) and health care inequities in their communities (Westfall et al., 2019). By working together over decades, PBRNs build trust and partnerships and can be instrumental in scaling up effective interventions to advance health equity and sustain the interventions over time (Tolley et al., 2021; Westfall et al., 2019).

More recently, PBRNs have been able to aggregate electronic health record data from hundreds of health care settings to enable rapid observational and interventional research (e.g., PCORnet) (Forrest et al., 2021; McTigue et al., 2020). These “real-world” health care laboratories require sustained investment in infrastructure.

Minoritized and low-income populations are more likely to get care in safety-net settings (e.g., city- and county-funded health care systems), which face unique and significant challenges to participate in research of any kind (DeVoe and Sears, 2013; Heintzman et al., 2014; Likumahuwa et al., 2013; Mehta et al., 2021). In addition to supporting the inclusion of safety-net systems in PBRNs, additional resources are needed for research in these settings, such as managing grants and IRB submissions, requirements for studies to be conducted within safety-net clinics, consortium arrangements for research infrastructure, and support for embedding clinician-researchers (Mehta et al., 2021).

Lack of Diversity in Research Participation

In 2022, the National Academies Improving Representation in Clinical Trials and Research: Building Research Equity for Women and Underrepresented Groups consensus report documented that investments in clinical trials have contributed significantly to treating and preventing diseases to improve the health and well-being of the nation (NASEM, 2022).

However, it concluded that representation has been limited for people in racially and ethnically minoritized populations. Various factors influence that spanning individuals, institutions that fund and design clinical trials, organizations that protect the rights and welfare of people recruited to participate in research activities, journals that publish the results, and national policies and practices governing research.

The report highlighted this the lack of representation imposes immense social and economic costs on individuals and the nation, including worsened inequities in health care and lack of access to effective therapies for some populations, limited generalizability of research findings to the whole U.S. population, and an undermining of trust of the clinical research enterprise and the medical establishment. In addition, the lack of representation

could compound low recruitment issues that cause many clinical trials to fail, stifle innovation and new discoveries, and cost billions of dollars. All of these may indirectly contribute to increased health care expenditures. The report also emphasized that diverse representation within clinical research can help make strides toward health equity. PBRNs, as described, can partner with academic researchers to recruit members of the community into trials (Westfall et al., 2019). Other potential networks for diversifying recruitment have been formed around specific diseases or studies. One example is the NCI Community Oncology Research Program, a national network that brings cancer clinical trials and care delivery studies to people in their own communities (NCI, 2024). It is composed of seven research bases and 46 community sites,22 14 of the latter are designated as minority/underserved.23 Improving Representation in Clinical Trials and Research (NASEM, 2022) identified several actions the U.S. government, academia, industry, communities, and other participants in the clinical trial ecosystem can take to increase the inclusion of minoritized populations (see Box 7-2).

Strategies to Improve Health Equity Research Infrastructure

Invest in Community Engagement

A robust evidence base demonstrates that CBPR approaches are effective in increasing clinical research participation and retention. For example, the Center for Asian Health at Temple University partnered with the Asian Community Health Coalition to recruit CHWs and Chinese community-based organizations (CBOs), such as religious and human services organizations, to provide clinical trial education to Chinese Americans (Ma et al., 2014). The researchers found that participants’ clinical trial knowledge increased in 15 areas, including understanding blinding procedures (from 17.8 to 38.9 percent), the opportunity to withdraw (from 68.0 to 88.7 percent), and that clinical trials improve cancer outcomes (from 75.3 to 83.8 percent). Although some areas did not see improvement, including motivation for participation, the investigators attributed the overall success to the CBPR practices used (Ma et al., 2014).

Similarly, CBPR practices can impact participant retention. For example, investigators conducted a pilot study using a CBPR approach to evaluate the retention of older minoritized women with urinary incontinence, compared with a traditional strategy for research retention (Pearson et al., 2022). For the experimental group, the research team

___________________

22 See https://ncorp.cancer.gov/findasite/community-sites.php (accessed March 29, 2024).

23 See https://ncorp.cancer.gov/findasite/minority-sites.php (accessed March 29, 2024).

BOX 7-2

Recommendations from the 2022 National Academies Report Improving Representation in Clinical Trials and Research: Building Research Equity for Women and Underrepresented Groups

Reporting

- HHS should establish an intradepartmental task force on research equity charged with coordinating data collection and developing better accrual tracking systems across federal agencies.

- The NIH should standardize the submission of demographic characteristics for trials to ClinicalTrials.gov beyond existing guidelines so that trial characteristics are labeled uniformly across the database and can be easily disaggregated, exported, and analyzed by the public.

- Journal editors, publishers, and the International Committee on Medical Journal Editors should require information on the representativeness of trials and studies for submissions to their journals.

Accountability

- The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) should require study sponsors to submit a detailed recruitment plan no later than at the time of Investigational New Drug and Investigational Device Exemption application submission that explains how they will ensure that the trial population appropriately reflects the demographics of the disease or condition under study.

- In grant proposal review, the NIH should formally incorporate considerations of participant representativeness in the score-driving criteria that assess the scientific integrity and overall impact of a grant proposal.

- The Office of Human Research Protections (OHRP) and the FDA should direct local institutional review boards (IRBs) to assess and report the representativeness of clinical trials as one measure of sound research design it requires for the protection of human subjects.

- The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) should amend its guidance for coverage with evidence development to require that study protocols include a plan for recruiting and retaining participants representative of the affected beneficiary population and a plan for monitoring achievement of representativeness and a process for remediation if coverage with evidence development studies are not meeting goals for representativeness.

Federal Incentives

- Congress should direct the FDA to enforce existing accountability measures and establish a taskforce to study new incentives for new drug and device for trials that achieve representative enrollment.

- The CMS should expedite coverage decisions for drugs and devices that have been approved based on clinical development programs representative of the populations most affected by the treatable condition.

- CMS should incentivize community providers to enroll and retain participants in clinical trials by reimbursing for the time and infrastructure that is required.

- The Government Accountability Office should assess the impact of reimbursing routine care costs associated with clinical trial participation for both Medicare (enacted in 2000) and Medicaid (enacted in 2020).

Remuneration

- Federal regulatory agencies, including OHRP, NIH, and FDA, should develop explicit guidance to direct local IRBs on equitable compensation to research participants and their caregivers.

- All sponsors of clinical trials and clinical research—federal, foundation, private, and industry—should ensure that trials adequately compensate research participants.

Education, Workforce, and Partnerships

- All entities involved in the conduct of clinical trials and clinical research should ensure a diverse and inclusive workforce, especially in leadership positions.

- Leaders and faculty of academic medical centers and large health systems should recognize research and professional efforts to advance community-engaged scholarship and other research to enhance the representativeness of clinical trials as areas of excellence for promotion or tenure.

- Leaders of academic medical centers and large health systems should provide training in community engagement and in principles of diversity, equity, and inclusion for all study investigators, research grants administration, and IRB staff as a part of the required training for any persons engaging in research involving human subjects.

- HHS should substantially invest in community research infrastructure that will improve representation in clinical trials and clinical research.

collaborated with the National Hispanic Council on Aging, a CBO, and its local community, Casa Iris, a nonprofit senior housing (non-nursing) facility. The CBPR group received education on urinary incontinence by Spanish-speaking research staff that adapted and implemented a randomized clinical trial multimodal rehabilitation intervention for the Casa Iris community center staff. In contrast, the control group received fliers, a study website, and letters and phone reminders. All participants recruited using the CBPR approach were Hispanic; those recruited with the traditional approach were primarily Black (62.5 percent). Participants in the CBPR group had significantly higher rates and increased odds of retention, compared to the traditional group, during screening (76.9 versus 40.6 percent), consent (80 versus 44.3 percent), and randomization (50.0 versus 14.8 percent). The research team also saw differences in the ability to reach people at the initial stages of recruitment, with 59.4 percent of the traditional research group unable to be contacted versus only 23.1 percent of those in the CBPR group.

Using a CBPR approach helped recruit Middle Eastern/Arab American and Latino/a adults of all ages for a study on Alzheimer’s disease and dementia (Ajrouch et al., 2020). The Michigan Center for Contextual Factors in Alzheimer’s Disease’s Community Liaison and Recruitment Core was responsible for community engagement with Middle Eastern/Arab American and Latino/a communities. It used a logic model for its recruitment process and built from assumptions that including community members in recruitment efforts would increase the participant pool. To achieve this goal, the research team worked with community advisory boards, including those from CBOs, caregivers, and health professionals. The advisory boards also included bilingual community liaisons, community and professional organizations, and universities to implement a health education learning series, conduct outreach on social media and via newsletters, and hold regular community advisory board meetings and community events. During these events, the team successfully recruited more minoritized participants than their goal. The investigators emphasized the importance of connecting with and empowering community leaders to ensure sustainable community engagement, attending to the diversity within marginalized populations (e.g., religious diversity in the Middle Eastern/Arab American community), and working with community members to ensure appropriate and meaningful language translation. Similarly, the Wisconsin Registry for Alzheimer’s Project, a longitudinal observational cohort study for adult children of people with Alzheimer’s disease, used an innovative CBPR approach to increase the representation of Black caregivers and elders (Green-Harris et al., 2019) after the team made several attempts to recruit via more traditional methods (e.g., clinical referrals, newspaper advertisements, e-mails to alums).

Specifically, the research team implemented asset-based community development approaches, addressing the community’s needs by connecting members with culturally tailored programs and services (Kretzmann and McKnight, 1993). The investigators proposed that community resources are necessary for academic research projects to reach their utmost potential (Green-Harris et al., 2019). Their recruitment effort involved identifying key African American stakeholders through grassroots networks, creating a community advisory board, and establishing the Milwaukee Health Services Memory Diagnostic Clinic to provide health education. This clinic proved essential for building trust and credibility and helped the researchers position themselves as a trusted community resource. These efforts successfully increased African American participation. Meeting community needs through service rather than research is a promising and innovative approach to build trusting relationships with community members and have a more transparent and firsthand understanding of the community’s needs on the ground.

Research has also shown that PhotoVoice is another example of a CBPR technique that effectively engages minoritized youth in the research process to develop community-based interventions addressing community needs and issues (Alegría et al., 2022; NeMoyer et al., 2021; Perez et al., 2016; Sarti et al., 2018). One research team, for example, used this methodology with urban low-income and deprived youth, allowing them to create compelling narratives about their community environments and reach local policy makers (Sarti et al., 2018). Other investigators used the methodology with Latina adults living in central North Carolina to guide discussions of community factors impacting mental health and present common themes in community forums to local policymakers (Perez et al., 2016). One finding was that participants wished they had received more training in photography, public speaking, and organizational structure. However, PhotoVoice was viewed as an innovative way to identify community issues and create sustainable partnerships in the community that can be leveraged for social action.

MOVING HEALTH EQUITY RESEARCH FROM OBSERVATIONS TO INTERVENTIONS

Although the literature has many studies documenting differential outcomes and treatment of racially and ethnically minoritized groups in health care settings, few studies have tested interventions to improve these outcomes (Agurs-Collins et al., 2019; Alegría et al., 2021). Some initiatives have targeted individuals—primarily those working in health care settings. For example, anti-bias training and cultural competence/humility training have been developed for health care professionals (Baumann et al., 2023). However, widely implementing these interventions and studying them in diverse practice settings has remained challenging. The ongoing lack of

progress toward reducing racial and ethnic health care inequities has heightened calls for more research on interventions—specifically multilevel and structural—that go beyond individuals and health care settings.

Implementation Science Research

Implementation research—“the scientific study of methods to promote the systematic uptake of research findings and other evidence-based practices into routine practice, and, hence, to improve the quality and effectiveness of health services and care”—has emerged as an important field over the last few decades (Eccles and Mittman, 2006). Unfortunately, many evidence-based practices, policies, and interventions may not be relevant to racial and ethnic groups experiencing health inequities (Baumann et al., 2023; Emmons and Chambers, 2021; Mistry et al., 2023). The evidence underlying many practices and interventions was created in clinical and research settings without substantial racial and ethnic diversity and often in high-resource settings where individuals are not experiencing social and structural barriers to health and health care (Baumann et al., 2023; Mistry et al., 2023). Therefore, evidence-based health care interventions may fail to achieve health equity because of gaps in knowledge and translation as well as failure to consider the systems that influence health inequities and care delivery (Chinman et al., 2017; Kwan et al., 2022; Mistry et al., 2023; Osuji et al., 2023).

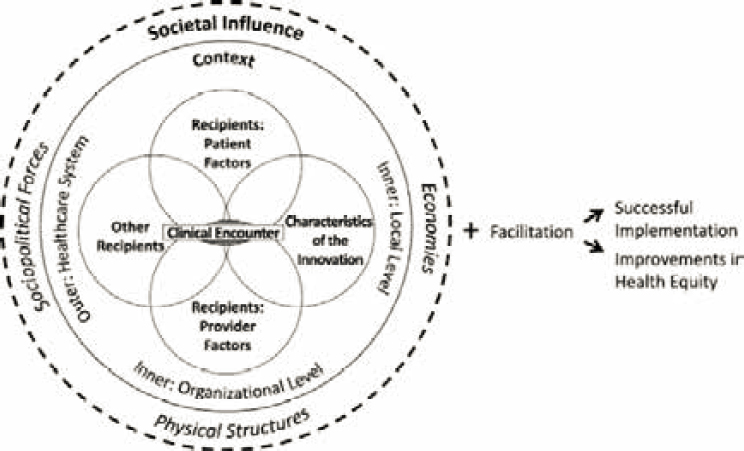

Broadening the scope of health equity research to include assessing the factors leading to successful implementation and sustainment of interventions may help eliminate inequities (Cooper et al., 2021; McNulty et al., 2019; Proctor et al., 2023; Shelton et al., 2021). To do so will require the integration of equity and antiracism lenses, which recognize racism as a fundamental driver of health care inequities and that solutions require multisector partnerships and meaningful engagement of communities (Baumann et al., 2023; Peek et al., 2023; Shelton et al., 2021). More recently, evidence and tools have emerged to increase opportunities for implementation science to be used to address health and health care inequities. Figure 7-3 provides one framework with pre-implementation guidance to enhance opportunities to achieve health equity (Woodward et al., 2019). The widely used Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research was recently updated based on user feedback and added constructs to better assess equity (Damschroder et al., 2022). Specifically, it urges collaborating with equity experts and using equity, justice, and antiracist theories. These developments show promise for broader dissemination and rigorously evaluated implementation of health equity evidence.

SOURCE: Woodward et al., 2019; used with permission under CCBY.

Centering Equity for Emerging Health Care Technologies

As described in Chapter 6, technological innovations have significantly changed the health care delivery landscape in the past 20 years. It is important to thoroughly consider the implications for racial and ethnic health care inequities. Innovations can either reduce or exacerbate existing inequities, which requires deliberate and strategic research approaches, generating evidence to guide development of new health care technology (HIT) with explicit attention to their likely effects on inequities.

A range of key elements should inform priorities for innovation in HIT. First, equity should be an explicit core objective, such that investments are directed toward innovation that can reduce rather than worsen inequities. Second, affected communities need to be engaged in identifying needs to guide HIT development and deployment. Third, priorities for technological innovations should account for SDOH that drive current inequities and include considering the implementation and delivery strategies that will ensure equitable benefits from innovation.

Within particular areas of innovation, several examples point to the opportunity to more actively address inequities through technology. Telehealth and digital health can promote accessibility and usability for individuals from diverse socioeconomic backgrounds, although realizing this

potential will require addressing digital literacy and infrastructure barriers to extend equitable access to telehealth services. Within the domain of artificial intelligence and precision medicine, an important requirement for these innovations to produce equitable population benefits is to address representation in the genomic databases used to train precision medicine algorithms (Hendricks-Sturrup et al., 2023). Some minoritized communities may, however, resist greater representation in genomic databases due to concerns with how these data may be used. The legacies of abuses associated with genomic research contribute to this resistance, including commercialization of biospecimens (Lee et al., 2019), breaches of confidentiality (Xu and Zhang, 2019), eugenics (Watson et al., 2022), and traumatizing interpretations of data that violate Indigenous beliefs (Havasupai Tribe) (Blanchard et al., 2017; Garrison, 2013; Garrison et al., 2019). Additionally, the complexities of genomics, use of DNA as criminal evidence in justice systems that unjustly harm minoritized groups, and disparities in privacy risks contribute to distrust in genomic research (Watson et al., 2022).

Finally, regarding technological innovations in diagnostics, therapeutics, and preventive interventions, it is important to recognize unmet needs among disadvantaged groups and ensure that groups with greatest advantage do not drive research and development priorities. A key component of this is to consider the availability of delivery platforms that prioritize both new technologies and the capacity to ensure equitable access and affordability.

HIGH-PRIORITY AREAS FOR FUTURE RESEARCH

Many areas remain to address in health equity research endeavors. The areas of highest priority should be gaps in the current understanding of underlying causes of inequities and should promote the development of successful interventions to eliminate inequities and the evidence to support widespread implementation and translation into practice. Box 7-3 presents some examples of these high-priority areas of research.

CHAPTER SUMMARY

Important shifts in funding and conduct of health equity research have occurred in the 20 years since Unequal Treatment. Yet, progress has been slow and incremental due to historically underfunded health equity research projects, programs, and investigators; exclusion of racially and ethnically minoritized groups from research; incomplete and inaccurate race, ethnicity, and SDOH data; and inadequate infrastructure and partnerships to rigorously conduct this research and translate findings into policies and practice. New research approaches, funding opportunities, and training programs

BOX 7-3

High-Priority Areas for Future Research

- Linking macro-level policies with the lived experiences of racially and ethnically minoritized populations to fully understand the various pathways that lead to inequitable outcomes.

- Integrating and sustaining interventions to address health-related social needs into the health care delivery system.

- Developing and testing new care models designed to improve equity in health care access and outcomes, and implementation and health policy research to promote and accelerate adopt and scaling up effective new models.

- Continuing to advance Indigenous governance and self-determination using Indigenous and decolonial methodologies and Indigenous research ethics.

- Transitioning from interventions to change individual health behaviors to efforts targeting other levels of change and combining multiple levels (i.e., interventions at the community and societal levels).

- Identifying and delineating best practices for cross-organizational partnerships.

- Developing sustainable models and approaches that effectively build community empowerment and capacity.

- Expanding basic social science research, which focuses on understanding human behavior, is fundamental to developing interventions. (Although investment in applied social science research has incrementally increased, support for basic research has been limited.)

- Comparative effectiveness research, which compares two or more interventions, offers a framework for integrating health equity into research. Identifying appropriate comparators and studying effectiveness in racially and ethnically minoritized groups could advance the field.

- Understanding health across the lifespan is vital to reducing inequities. Marginalized racial and ethnic groups are often underrepresented in large-scale lifespan studies. Longitudinal studies focused exclusively on marginalized racial and ethnic groups exist (e.g., Jackson Heart Study, Black Women’s Health Study, Hispanic Community Health Study), but are under resourced.

- Research to understand the impact of racism is emerging; however, interventions to address racism, specifically structural racism, need to be developed and tested.

- Implementation science research should prioritize studying evidence that could impact policy (e.g., discovering the most effective implementation strategies to support community health workers in reducing racial and ethnic health care inequities could impact policies for certifying and funding them).

for health equity researchers show promise for developing evidence that reduces racial and ethnic health care inequities and advances health equity.

Based on the materials in this chapter, the committee offers these conclusions:

Conclusion 7.1. A comprehensive review of the NIH portfolio finds that health disparity and health equity research account for only 4.3 percent of direct costs of NIH awards between 2012 and 2023. Although funding trends have increased in recent years, health equity and health inequities research funding are not evenly distributed across NIH Institutes and Centers.

Conclusion 7.2. Community-engaged and community-driven research represents a small fraction of NIH-funded research.

Conclusion 7.3. Researchers from minoritized racial and ethnic groups are significantly underrepresented in the scientific workforce. Structural barriers for health and health care equity research disproportionately impact researchers from racially and ethnically minoritized groups.

Conclusion 7.4. Despite a recent influx of researchers into the health equity field, partly the result of more funding opportunities, there is a paucity of programs to provide health equity training and no standard/certification to ensure someone has ample training.

Conclusion 7.5. Critically evaluating health equity research has been hindered by inconsistent practices in analyzing and reporting health equity research, lack of collection and use of common data elements across studies, and conflation of race and ethnicity with genetics.

Conclusion 7.6. The current research infrastructure, including data sources, is insufficient to support the types and scale of health equity research needed.

Conclusion 7.7. There are a limited number of interventional studies focused on eliminating racial and ethnic health care inequities and very few of them have been implementation science and comparative effectiveness studies testing multilevel and structural interventions.

REFERENCES

Agurs-Collins, T., S. Persky, E. D. Paskett, S. L. Barkin, H. I. Meissner, T. R. Nansel, S. S. Arteaga, X. Zhang, R. Das, and T. Farhat. 2019. Designing and assessing multilevel interventions to improve minority health and reduce health disparities. American Journal of Public Health 109(S1):S86-S93.

Ajrouch, K. J., I. E. Vega, T. C. Antonucci, W. Tarraf, N. J. Webster, and L. B. Zahodne. 2020. Partnering with Middle Eastern/Arab American and Latino immigrant communities to increase participation in alzheimer’s disease research. Ethnicity & Disease 30(Suppl 2): 765-774.

Alcántara, C., S. F. Suglia, I. P. Ibarra, A. L. Falzon, E. McCullough, T. Alvi, and L. J. Cabassa. 2021. Disaggregation of Latina/o child and adult health data: A systematic review of public health surveillance surveys in the United States. Population Research and Policy Review 40:61-79.

Alegría, M., R. G. Frank, H. B. Hansen, J. M. Sharfstein, R. S. Shim, and M. Tierney. 2021. Transforming mental health and addiction services. Health Affairs 40(2):226-234.

Alegría, M., K. Alvarez, A. NeMoyer, J. Zhen-Duan, C. Marsico, I. S. O’Malley, R. Mukthineni, T. Porteny, C. N. Herrera, and J. Najarro Cermeño. 2022. Development of a youth civic engagement program: Process and pilot testing with a youth-partnered research team. American Journal of Community Psychology 69(1-2):86-99.

Aluko, Y., S. Garfield, P. Kasen, and B. Minta. 2023. Why America’s Health Equity Investment Has Yielded a Marginal Return. https://www.ey.com/en_us/health/america-s-health-equity-investment-marginal-return (accessed March 29, 2024).

Baumann, A. A., R. C. Shelton, S. Kumanyika, and D. Haire-Joshu. 2023. Advancing healthcare equity through dissemination and implementation science. Health Services Research 58:327-344.

Becker, T., S. H. Babey, R. Dorsey, and N. A. Ponce. 2021. Data disaggregation with American Indian/Alaska Native population data. Population Research and Policy Review 40:103-125.

Blanchard, J. W., G. Tallbull, C. Wolpert, J. Powell, M. W. Foster, and C. Royal. 2017. Barriers and strategies related to qualitative research on genetic ancestry testing in Indigenous communities. Journal of Empirical Research on Human Research Ethics 12(3):169-179.

Boulware, L. E., G. Corbie, S. Aguilar-Gaxiola, C. H. Wilkins, R. Ruiz, A. Vitale, and L. E. Egede. 2022. Combating structural inequities—diversity, equity, and inclusion in clinical and translational research. New England Journal of Medicine 386(3):201-203.

Brown, A. F., G. X. Ma, J. Miranda, E. Eng, D. Castille, T. Brockie, P. Jones, C. O. Airhihenbuwa, T. Farhat, and L. Zhu. 2019. Structural interventions to reduce and eliminate health disparities. American Journal of Public Health 109(S1):S72-S78.

Carlos, R. C., S. Obeng-Gyasi, S. W. Cole, B. J. Zebrack, E. D. Pisano, M. A. Troester, L. Timsina, L. I. Wagner, J. A. Steingrimsson, and I. Gareen. 2022. Linking structural racism and discrimination and breast cancer outcomes: A social genomics approach. Journal of Clinical Oncology 40(13):1407.

Chen, C. Y., S. S. Kahanamoku, A. Tripati, R. A. Alegado, V. R. Morris, K. Andrade, and J. Hosbey. 2022. Systemic racial disparities in funding rates at the National Science Foundation. ELife 11:e83071.

Chinman, M., E. N. Woodward, G. M. Curran, and L. R. Hausmann. 2017. Harnessing implementation science to increase the impact of health disparity research. Medical Care 55(Suppl 9 2):S16.

Cooper, L. A., T. S. Purnell, M. Engelgau, K. Weeks, and J. A. Marsteller. 2021. Using implementation science to move from knowledge of disparities to achievement of equity. The Science of Health Disparities Research 289-308.

Damschroder, L. J., C. M. Reardon, M. A. O. Widerquist, and J. Lowery. 2022. The updated consolidated framework for implementation research based on user feedback. Implementation Science 17(1):75.

Davies, S. W., H. M. Putnam, T. Ainsworth, J. K. Baum, C. B. Bove, S. C. Crosby, I. M. Côté, A. Duplouy, R. W. Fulweiler, and A. J. Griffin. 2021. Promoting inclusive metrics of success and impact to dismantle a discriminatory reward system in science. PLoS Biology 19(6):e3001282.

Davis, L. 2021. Human genetics needs an antiracism plan. Scientific American 17:2021.

Davis, M. M., S. Keller, J. E. DeVoe, and D. J. Cohen. 2012. Characteristics and lessons learned from practice-based research networks (PBRNs) in the United States. Journal of Healthcare Leadership 107-116.

Dean, L. T., and R. J. Thorpe, Jr. 2022. What structural racism is (or is not) and how to measure it: Clarity for public health and medical researchers. American Journal of Epidemiology 191(9):1521-1526.

DeVoe, J. E., and A. Sears. 2013. The OCHIN community information network: Bringing together community health centers, information technology, and data to support a patient-centered medical village. The Journal of the American Board of Family Medicine 26(3):271-278.

Eccles, M., and B. Mittman. 2006. Welcome to implementation science. Implementation Science 1:1.

Emmons, K. M., and D. A. Chambers. 2021. Policy implementation science—An unexplored strategy to address social determinants of health. Ethnicity & Disease 31(1):133.

Forrest, C. B., K. M. McTigue, A. F. Hernandez, L. W. Cohen, H. Cruz, K. Haynes, R. Kaushal, A. N. Kho, K. A. Marsolo, V. P. Nair, R. Platt, J. E. Puro, R. L. Rothman, E. A. Shenkman, L. R. Waitman, N. A. Williams, and T. W. Carton. 2021. Pcornet® 2020: Current state, accomplishments, and future directions. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology 129:60-67.

Friedman, J., H. Hansen, and J. P. Gone. 2023. Deaths of despair and Indigenous data genocide. The Lancet 401(10379):874-876.

Garrison, N. A. 2013. Genomic justice for Native Americans: Impact of the Havasupai case on genetic research. Science, Technology, & Human Values 38(2):201-223.

Garrison, N. A., M. Hudson, L. L. Ballantyne, I. Garba, A. Martinez, M. Taualii, L. Arbour, N. R. Caron, and S. C. Rainie. 2019. Genomic research through an Indigenous lens: Understanding the expectations. Annual Review of Genomics and Human Genetics 20:495-517.

Geneviève, L. D., A. Martani, D. Shaw, B. S. Elger, and T. Wangmo. 2020. Structural racism in precision medicine: Leaving no one behind. BMC Medical Ethics 21:1-13.

Getrich, C. M., A. L. Sussman, K. Campbell-Voytal, J. Y. Tsoh, R. L. Williams, A. E. Brown, M. B. Potter, W. Spears, N. Weller, and J. Pascoe. 2013. Cultivating a cycle of trust with diverse communities in practice-based research: A report from Prime Net. The Annals of Family Medicine 11(6):550-558.

Gibbs, K., Jr. 2014. Beyond “the pipeline”: Reframing science’s diversity challenge. Scientific American Blog Network. https://www.scientificamerican.com/blog/voices/beyond-the-pipeline-reframing-science-s-diversity-challenge/ (accessed March 29, 2024).

Gibbs, K. D., Jr., J. Basson, I. M. Xierali, and D. A. Broniatowski. 2016. Decoupling of the minority Ph.D. talent pool and assistant professor hiring in medical school basic science departments in the U.S. Elife 5:e21393.

Green-Harris, G., S. L. Coley, R. L. Koscik, N. C. Norris, S. L. Houston, M. A. Sager, S. C. Johnson, and D. F. Edwards. 2019. Addressing disparities in Alzheimer’s disease and African-American participation in research: An asset-based community development approach. Frontiers in Aging Neuroscience 11(C7):125.

Griffith, D. M., E. C. Jaeger, E. M. Bergner, S. Stallings, and C. H. Wilkins. 2020. Determinants of trustworthiness to conduct medical research: Findings from focus groups conducted with racially and ethnically diverse adults. Journal of General Internal Medicine 35:2969-2975.

Groos, M., M. Wallace, R. Hardeman, and K. P. Theall. 2018. Measuring inequity: A systematic review of methods used to quantify structural racism. Journal of Health Disparities Research and Practice 11(2):13.

Giusti, K., R. Hamermesh, and M. Krasnow. 2021. Addressing demographic disparities in clinical trials. https://hbr.org/2021/06/addressing-demographic-disparities-in-clinical-trials (accessed March 29, 2024).

Hardeman, R. R., P. A. Homan, T. Chantarat, B. A. Davis, and T. H. Brown. 2022. Improving the measurement of structural racism to achieve antiracist health policy. Health Affairs 41(2):179-186.

Heart, M. Y. H. B., and J. Chase. 2016. Historical trauma among indigenous peoples of the Americas: Concepts, research, and clinical considerations. Wounds of History 270-287.

Heintzman, J., S. Likumahuwa, C. Nelson, M. P. Eiff, R. Gold, J. E. Carroll, J. Muench, C. Hill, M. Mital, and J. E. DeVoe. 2014. “Not a kidney or a lung”: Research challenges in a network of safety net clinics. Family Medicine 46(2):105.

Hendricks-Sturrup, R., M. Simmons, S. Anders, K. Aneni, E. W. Clayton, J. Coco, B. Collins, E. Heitman, S. Hussain, and K. Joshi. 2023. Developing ethics and equity principles, terms, and engagement tools to advance health equity and researcher diversity in AI and machine learning: Modified delphi approach. Journal of Medical Internet Research AI 2(1):e52888.

Hofstra, B., V. V. Kulkarni, S. Munoz-Najar Galvez, B. He, D. Jurafsky, and D. A. McFarland. 2020. The diversity–innovation paradox in science. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 117(17):9284-9291.

Holup, J. L., N. Press, W. M. Vollmer, E. L. Harris, T. M. Vogt, and C. Chen. 2007. Performance of the U.S. Office of Management and Budget’s revised race and ethnicity categories in Asian populations. International Journal of Intercultural Relations 31(5):561-573.