Ending Unequal Treatment: Strategies to Achieve Equitable Health Care and Optimal Health for All (2024)

Chapter: 4 Health Care Laws and Payment Policies

4

Health Care Laws and Payment Policies

The legal and political landscape has changed significantly since Unequal Treatment. This chapter explores the legal and political environment, including U.S. health care and civil rights laws as they pertain to the complexities of health care inequities. It discusses these developments and the achievements and shortcomings of some of the most significant policy and law interventions aimed at advancing health care and health equity. The chapter also discusses health care payment policies and their implications for advancing equity. As noted in previous chapters, the committee is aware that health—a state of complete physical, mental, and social well-being and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity—and health care—the services provided to individuals, families, and communities for the purpose of promoting, maintaining, or restoring health across settings of care—are different but inextricably linked. Therefore, this report uses “health care system” (activities related to the delivery of care across the continuum of care) to describe the U.S. health care system as a whole and individual health care systems and “health” when discussing outcomes.

HEALTH CARE LAWS

As discussed in Chapter 1, the legal and political environment has evolved in important ways since Unequal Treatment. The Affordable Care Act (ACA) was the most comprehensive federal legislative instrument for these health care reforms. However, the ACA contained certain structural limitations that carry important health equity implications. Furthermore, some of its most important provisions intended to advance equity have

faced multiple legal and political challenges. Decisions by the U.S. Supreme Court weakened the ACA’s impact by removing policies aimed at mitigating the effects of racial and ethnic health care inequity. For example, it overturned the mandatory requirement for states to expand their Medicaid programs. Other decisions eliminated the constitutional right to abortion, with far-reaching implications for health and health care, and severely restricted efforts in higher education to diversify the workforce.

The U.S. legal and political system rests on a federal model. As a result, laws and policies at the federal and state levels can advance or impede racial and ethnic health care equity. This is especially the case for federal health care programs serving low-income and minoritized populations because of states’ major role in designing and administering health care payment and delivery programs. Tribal, territorial, and local governments are also important. Detailed analyses of federal, tribal, state, territorial, and local laws and policies are beyond the scope of this report. Given resource and time constraints, the committee focused on federal health care laws and policies, while also describing a few key state decisions that are directly relevant to the goals and provisions of the ACA.

THE AFFORDABLE CARE ACT (ACA)

The ACA’s1 fundamental purpose was to achieve greater health equity. It expanded access to affordable health insurance, strengthened the scope of insurance coverage, launched potentially far-reaching changes in health care and public health, and established sweeping, expansive health care civil rights protections (Rosenbaum, 2011). In addition, the ACA ushered in an era of expanded focus on the concept of health care as responsive to not only medical conditions but also underlying social, economic, and environmental risks that act as drivers of health.

The ACA, the laws that followed, and federal and state agency implementation efforts have generated far-reaching changes in access to affordable health insurance for those without affordable employer plans or public insurance, free preventive coverage benefiting nearly all with private insurance or Medicare, and the scope and quality of coverage itself. These changes included the following:

- Strengthening the federal regulatory framework for private health insurance and employer-sponsored health plans in eligibility, benefit design, and coverage;

- Establishing a new pathway to affordable health insurance for individuals and small businesses;

___________________

1 See https://www.govinfo.gov/app/details/STATUTE-124/STATUTE-124-Pg119 (accessed on April 29, 2024).

- Transforming Medicaid eligibility and the process for enrolling in and renewing coverage;

- Expanding Medicare benefits;

- Introducing reforms to incentivize growing health care systems’ capabilities to address both medical and social needs, including establishing a new Center for Medicare and Medicaid Innovation (now known as the “CMS Innovation Center)” charged with testing new approaches to payment and service delivery to improve patient care, reduce health care costs, and promote greater alignment across payment systems to strengthen care delivery;

- Expanding access to primary health care in underserved communities;

- Introducing a new model for funding public health;

- Reforming the legal framework defining the relationship between tax-exempt hospitals and the communities they serve; and

- Restructuring civil rights accountability within the health care system.

KEY ACA PROVISIONS

Private Insurance Reforms

The ACA introduced important structural reforms in private insurance markets that established an overarching framework for the plans that working-age individuals purchase for themselves and their families. These reforms set extensive standards for the types of comprehensive insurance plans that employers sponsor. The ACA also preserved state authority to expand beyond federal minimums, and a number do so, while also preserving considerable regulatory autonomy for self-insured employer plans governed by the Employee Retirement Income Security Act.2

Prohibiting Insurer Policies That Limit Access to Coverage

The ACA bars certain types of barriers to coverage access that have characterized private insurance. These prohibitions apply to plans of all sizes, whether insured or self-insured, and are designed to make insurance more accessible and fairer for people experiencing greater health burdens and attendant health costs. Federal law now prohibits insurers and employer plans from refusing to offer or renew policies or rescinding coverage. These reforms also eliminate insurers’ ability to impose preexisting condition exclusions, unreasonable waiting periods before coverage begins, annual and lifetime dollar limits on coverage, and (with certain

___________________

2 See https://www.dol.gov/general/topic/retirement/erisa (accessed April 29, 2024).

limited exceptions) coverage discrimination linked to health status. The law also extended dependent coverage to age 26, a reform that enabled about 2.5 million young adults to maintain coverage.3

Strengthening Health Care Coverage

Essential health benefits (EHBs). The ACA established an EHB coverage standard for insurance plans in the individual and small group markets. It is meant to mirror a “typical” employer plan and covers 10 distinct, broad benefit categories with specified modifications to ensure coverage of benefits not typically found in employer plans, such as pediatric dental care. Federal mental health parity rules and prohibitions against coverage limits and exclusions based on age, disability, or expected length of life apply. Unless regulated or prohibited by state law, insurers remain free to use their specific internal treatment guidelines.

Preventive benefits without cost sharing. The ACA requires non-grandfathered private plans, both insured and self-insured, to cover a comprehensive range of preventive benefits without cost sharing. To determine the types and scope of this guarantee, the ACA adopts a dynamic model that relies on evolving, evidence-informed recommendations made by the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practice, Health Resources and Services Administration for women’s and children’s preventive services, and U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF).

Health Insurance Exchanges

The ACA established health insurance exchanges, popularly known as “ACA marketplaces,” to support enrollment and renewal through online tools and insurance navigators. They also enable people to enroll in alternative affordability programs, such as Medicaid or Child Health Insurance Program (CHIP), as eligibility for one of these other types of benefits precludes eligibility for marketplace plans. They allow low- and moderate-income people who lack affordable employer insurance and are ineligible for Medicare, Medicaid, or CHIP to purchase qualified health plans subject to the EHB coverage standard, which includes comprehensive preventive benefits without cost sharing. Federal rules established the marketplace, but states can operate their own exchanges. States can also use the federal exchange platform for some functions, including enrollment, plan selection, and determination of affordability eligibility, while retaining control over other aspects of their exchanges, such as regulating and certifying

___________________

3 See https://aspe.hhs.gov/reports/25-million-young-adults-gain-health-insurance-due-affordable-care-act-0 (accessed April 29, 2024).

qualifying health plans (QHPs). States vary substantially in how they approach exchange operation (KFF, 2024a); in 2024, 19 states fully operate their own exchanges, and another three states partner with the federal government (CMS, 2023).

Qualified Health Plans (QHPs) Sold in the Marketplace: Provider Network Standards

Under ACA regulations, marketplace plans should meet limited provider network inclusion standards, although these are significantly less robust than those applicable to Medicare Advantage. The Biden administration has taken steps to improve network adequacy criteria, but standards remain substantially more limited than those used for Medicare advantage plans (Pollitz, 2022). The marketplace standards require including at least some essential community-based providers, such as community health centers, but plans are held only to an unreasonable delay standard regarding network sufficiency. Under this federal standard, QHPs can exclude essential community providers if they otherwise meet the unreasonable delay standard, although state insurance laws can specify more robust network inclusion and adequacy standards. QHPs are not required to recognize accessibility costs incurred by essential community providers, including transportation, translation, or patient support services designed to address the needs of certain populations at high risk of exclusion from health care.

Affordability of Coverage and Care

The ACA’s affordability provisions address both premiums and cost sharing. (The “No Surprises Act,” enacted in 2021 as part of the Consolidated Appropriations Act, added further protections against high out-of-pocket costs by significantly limiting the ability of health care providers to engage in out-of-network balance billing.4) The ACA entitles low- and moderate-income people to advance premium tax credits and cost-sharing assistance, although the latter is capped at a family income level substantially lower than the premium assistance to promote affordability. The ACA offers further protection by capping premiums as a percentage of household income for all eligible enrollees in a qualified health plan offered by their employers or purchased individually, whether on or off the marketplace; that is, plans that satisfy all ACA access, coverage, and cost-sharing requirements.

___________________

4 See https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/FR-2022-08-26/pdf/2022-18202.pdf (accessed April 29, 2024).

Premium subsidies are tax credits paid directly to plans, with the size of the credit depending on household income. Citizens and lawfully present immigrants can qualify for credits that enable people with a modified adjusted gross income (MAGI) of 100–150 percent of the federal poverty level (FPL) to pay no premium.5,6 As a result of legislative reforms in the American Rescue Plan Act (Pub. L. 117-2), until 2025, people with incomes up to 150 percent of FPL pay no premiums for marketplace plans, while premiums are capped at 2 percent of MAGI for people with incomes of 150–200 percent of FPL. The law also ensures that premiums can rise only to a maximum of 8.5 percent of MAGI when MAGI reaches 400 percent of FPL or greater (KFF, 2023a). The ACA offers further protection by capping premiums as a percentage of household income for all who enroll in a QHP offered by their employers or purchased individually, whether on or off the marketplace; that is, plans that satisfy all ACA access, coverage, and cost-sharing requirements.

The ACA also provides cost-sharing subsidies, but these are limited to the lowest-income plan members. A QHP is set at an actuarial value of 70 percent, which leaves people responsible for 30 percent of allowed costs for covered services. For the lowest-income people, the actuarial value rises to 94 percent (KFF, 2023a). In October 2022, the Biden administration lifted a restriction that barred workers with affordable, self-only workplace coverage from using the marketplace to claim tax credits and secure coverage for their children and spouses through a subsidized marketplace plan.

Medicaid

The ACA introduced fundamental structural reforms in Medicaid. The single most important was establishing a uniform, nationwide coverage pathway for working-age adults with incomes up to 138 percent of FPL, who would otherwise not be eligible for Medicaid (benefits were traditionally based on pregnancy, disability, or status as a parent or caretaker of one or more minor children). This reform was intended to eliminate the most serious limitation—an eligibility framework that varied widely across states and excluded most low-income working-age adults without severe disabilities. The ACA envisioned that the poorest people would be insured through Medicaid, and once income reached 138 percent of FPL, seamlessly transition to marketplace plans using an integrated eligibility determination system with coverage accessible through generous premium subsidies

___________________

5 See https://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/text/42/18081 (accessed April 29, 2024).

6 Lawful residents barred from Medicaid during the applicable 5-year waiting period can qualify for premium assistance even if their incomes fall below the 100 percent marketplace threshold.

(Keith, 2022). Legal immigrants who are excluded from Medicaid until they have satisfied a 5-year waiting period can also use the marketplace and qualify for subsidized marketplace coverage even if their incomes place them below the income threshold that otherwise applies to income eligibility for marketplace subsidies.7

Continuing to rely on Medicaid to cover the poorest adults and children has had certain drawbacks. Most notably, segregating the poorest people into insurance plans with lower provider payment rates had eligibility rules still sufficiently tied to welfare to require constant verification of income, family status, health status, and other factors. In addition, the ACA Medicaid reforms omitted mandatory preventive benefits for the traditional population of working-age adults eligible for Medicaid and eliminated cost sharing for preventive services that applied only to the Medicaid expansion population. In 2022, Congress added mandatory, free immunization coverage for all adults covered by Medicaid. States continue to have the option, however, to exclude most ACA free preventive benefits for adults outside of the expansion population other than family planning, although some states cover family planning only and with more restrictions than ACA allows for the expansion population (Ranji et al., 2022).

The ACA’s adult coverage expansion rectified Medicaid’s structural inequity created by excluding many low-income working-age adults (Broaddus et al., 2016; Yearby et al., 2022). By recognizing working-age adults as a distinct coverage category and setting financial eligibility at the same level applicable to children, ACA expansion represented an important achievement in health equity, addressing decades of exclusion and financial eligibility standards for low-income parents and caretakers that could be as low as 16 percent of the FPL (KFF, 2023b).

The ACA contained other important Medicaid reforms, including mandatory coverage for low-income young adults aging out of foster care, eliminating an asset test for beneficiaries eligible based on poverty alone, and simplifying enrollment and renewal by using automated data, which reduced paperwork and eliminated the need for in-person reviews (MACPAC, 2017). Other reforms included expanded long-term services and support options for beneficiaries who are elderly or have severe disabilities and revisions to better coordinate and integrate Medicare and Medicaid for those in both programs, known as “dual enrollees” (Davis et al., 2015).

Despite these sweeping changes in eligibility and coverage, the reforms had certain important limits. First, omitting mandated free preventive services for traditional Medicaid leaves that as a state option with modest federal financial enhancements. Second, the residual effects of Medicaid as

___________________

7 See https://www.healthcare.gov/immigrants/lawfully-present-immigrants/ (accessed April 29, 2024).

a companion to cash welfare assistance mean that the risks of coverage loss as a result of even slight changes in income or family status remain (Tolbert and Ammula, 2023). Third, although the reforms streamlined enrollment and renewal procedures, they did not establish annual guaranteed enrollment as a means of reducing churn defined as the “temporary loss of coverage in which enrollees disenroll and then re-enroll within a short period of time” (Corallo et al., 2021). Churn remains a problem, not only in and out of Medicaid, but for people who, because of slight fluctuations in income, need to move between Medicaid and marketplace plans to find affordable coverage (Sommers and Rosenbaum, 2011).

Medicare

The ACA made important reforms to Medicare coverage, including expanding preventive benefits to overcome long-standing program limitations and modifying Part D prescription drug coverage to phase out the “doughnut hole,” the gap that occurs once covered costs reach a certain upper threshold and limits coverage until beneficiary costs reach catastrophic levels (Davis et al., 2015). Paralleling the reforms for the under-65 population, the ACA added preventive benefits without cost sharing to Medicare as well as an annual wellness visit.

Reforming Health Care

Beyond coverage, ACA reforms aimed to change health care itself. Three principal changes were codified. The first aimed to use Medicare financing incentives to test new ways to use payment to improve health care and patient centeredness and align payment structures to strengthen health care delivery. The second was designed to incentivize the growth of entities known as “accountable care organizations” (ACOs) and health homes, whose purpose was to develop and expand new models of coordinated service delivery responsive to both medical and health-related social needs (HRSNs). The third authorized major new investments in clinicians who practice in health professional shortage areas and increased support for comprehensive primary care clinics that anchor care in medically underserved rural and urban communities and teaching programs specializing in primary care to medically underserved populations (Rosenbaum, 2011).

ACOs and Health Homes Accountable Care Organizations (ACOs) and Health Homes

ACOs use shared savings to incentivize the growth of clinical practice groups accountable for health care quality and cost. A key model feature is its integration of clinical care with services aimed at meeting HRSNs.

ACOs contract with traditional Medicare, Medicare Advantage plans, and other insurers, with compensation tied to measures of efficiency and quality.8 In 2024, over 480 ACOs participated in Medicare and served about 11 million people.9 Congress encouraged the growth of Medicaid pediatric but not adult ACOs. Research suggests that one barrier to the growth of Medicaid ACOs has been insufficient health information technology systems that ACOs need to track systemwide expenditures for assigned members (Rosenthal et al., 2023).

Medicare ACOs remain a limited option for underserved populations, suggesting that incentives may be insufficient for the model to take hold in poorer communities with high proportions of beneficiaries of color. The Biden administration has sought to use the model to improve health equity by requiring ACOs to develop health equity plans and creating payment models to better respond to the heightened needs of residents of medically minoritized communities.10,11 No comparable requirement exists for integrated service delivery arrangements as in Medicaid managed care (Patel and Zephyrin, 2022).

The ACA also encouraged the growth of Medicaid health homes, a primary-care-based model focusing more holistically on patient health needs (Paradise and Nardone, 2014). The principal focus is serving beneficiaries with serious and chronic conditions, such as diabetes, hypertension, and depression, who can be managed effectively in primary care. As of 2019, 22 states and the District of Columbia had added health homes to their Medicaid programs (CMS, 2019).

The CMS Innovation Center

The CMS Innovation Center has focused on improving health care itself, promoting person-centered care, and aligning payment across the nation’s multipayer system to make systematic improvements in care delivery.12 In recent years, the Innovation Center has emphasized embedding health equity into the design, operation, and evaluation of its models (Jacobs et al, 2023). Special attention is paid to rural and underserved

___________________

8 See https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/USCODE-2011-title42/html/USCODE-2011title42-chap7-subchapXVIII-partE-sec1395jjj.htm (accessed April 29, 2024).

9 See https://www.cms.gov/newsroom/press-releases/participation-continues-grow-cms-accountable-care-organization-initiatives-2024 (accessed April 29, 2024).

10 See https://www.hhs.gov/about/news/2022/08/30/medicare-shared-savings-program-saves-medicare-more-than-1-6-billion-in-2021-and-continues-to-deliver-high-quality-care.html (accessed April 29, 2024).

11 See https://www.cms.gov/newsroom/fact-sheets/accountable-care-organization-aco-realizing-equity-access-and-community-health-reach-model (accessed April 29, 2024).

12 See https://www.cms.gov/priorities/innovation/data-and-reports/2022/cmmi-strategy-refresh-imp-report (accessed April 29, 2024).

communities and assuring that the responsiveness of system reforms to all populations is measured via demographic data and patient health outcomes.13

Community Health Centers (CHCs), Teaching Health Centers, the National Health Service Corps, and the Indian Health Service

The ACA permanently authorized the CHC program, increased National Health Service Corps funding, and established teaching health centers to directly anchor primary care residencies in community settings to increase the supply of primary care health professionals working in underserved communities with shortages.14 In addition, the ACA created a mandatory spending authority, the CHC Fund, to supplement the annual discretionary appropriations process.15 The goal of the fund, which must be renewed periodically, is to make a mandatory health equity investment in expanded primary care services in underserved communities to ensure that as the insurance reforms increased the demand for care, primary care access points were readily available. Without permanent funding, however, this program is limited in its ability to create sustainable and lasting change.

The CHC Fund, coupled with major growth in insurance revenue to health centers resulting from Medicaid expansion and subsidized marketplace insurance coverage, spurred sizable CHC growth, particularly in expansion states where the financial impact of the Medicaid reforms was greatest. From 2010 to 2021, patients served rose from 19.5 million to over 30 million (GAO, 2023). By 2023, the Teaching Health Centers program provided residencies for over 2,000 primary care physicians, mental health clinicians, and dentists (HRSA, 2023). Congress has also added billions of dollars in supplemental appropriations to help health centers expand COVID-19 treatment capacity in the hardest-hit communities and expand mental health services (Sharac et al., 2022) and addiction treatment and recovery (Corallo et al., 2020).

Although the CHC Fund has substantially improved access, challenges remain with Medicaid payment for covered services, two principal sources of CHC financing. Many states fail to adhere to Medicaid’s “federally qualified health center” (FQHC) payment rules, which require updates for medical inflation and changes in scope of services as health centers add

___________________

13 See https://www.cms.gov/priorities/innovation/innovation-models/ahead (accessed April 29, 2024).

14 See https://uscode.house.gov/view.xhtml?path=/prelim@title42/chapter6A&edition=prelim (accessed April 29, 2024).

15 See https://uscode.house.gov/view.xhtml?req=granuleid:USC-prelim-title42-section254b&num=0&edition=prelim (accessed April 29, 2024).

covered physical or mental health care. Payment lags also can be considerable (Rosenbaum et al., 2023a). Furthermore, while CMS policy allows FQHC payments for separate medical and mental health services furnished on the same day, no similar policy exists for multiple medical diagnostic and treatment services; as a result, for payment to occur, health centers need to require patients in need of medical treatment provided by more than one specialty (e.g., primary care, podiatry, optometry, addiction medicine) to make separate visits.16 These shortcomings in third-party financing policy and practice increase grant CHC dependence, depress needed revenue, and add to patients’ access barriers.

Despite evidence of extensive unmet need and service capacity shortages, and the long-standing treaty-based obligations on which Indian health care financing rests, Congress took no comparable action under the ACA to create a mandatory funding base for the Indian Health Service. The Biden administration has proposed to move the program onto a mandatory funding model beginning in FY 2025 and full funding by FY 2033.17

Prevention and Public Health

The ACA established a public health and prevention fund as a permanent and mandatory spending authority, the first time that federal public health investments have been put on such financial footing.18 According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, such funds have been invested in “public health programs to reduce the leading causes of death and disability, support early detection of and response to health threats, and expand evidence-based strategies” (CDC, 2021) such as “community and clinical prevention initiatives; research, surveillance and tracking; public health infrastructure; immunizations and screenings; tobacco prevention; and public health workforce and training” (HHS, 2020).

Strengthening the Community Obligations of Tax-Exempt Hospitals

The ACA amended the Internal Revenue Code to expand the duties of tax-exempt hospitals as a condition of tax exemption (Rosenbaum and Margulies, 2011). Along with reforms aimed at ensuring reasonable billing

___________________

16 See https://www.cms.gov/medicare/payment/prospective-payment-systems/federally-qualified-health-centers-fqhc-center (accessed April 29, 2024).

17 See https://www.ihs.gov/newsroom/pressreleases/2023-press-releases/statement-from-ihs-director-roselyn-tso-on-the-presidents-fiscal-year-2024-budget/ (accessed April 29, 2024).

18 See https://www.govinfo.gov/app/details/USCODE-2010-title42/USCODE-2010-title42-chap6A-subchapXV-sec300u-11 (accessed April 29, 2024).

and collection practices and compliance with federal emergency care laws,19 the amendments require each facility to align programs and services with communitywide health needs and priorities.20 Under the amendment, each hospital needs to prepare a triennial community health needs assessment (CHNA) that incorporates community input and is formally adopted by its board. The CHNA, accompanied by an implementation strategy, should focus on the needs of everyone residing in its service areas, not only those who receive care at the hospital.21

However, the 2010 amendments contained significant limitations. First, they did not explicitly require hospitals to tie community benefit expenditures to CHNAs. The Internal Revenue Service (IRS), which administers federal tax laws governing tax-exempt organizations, did not interpret the law as requiring this. Thus, hospitals remain free to allocate their community benefit expenditures to activities that, although of value to them and their patients, may not be responsive to the deeper health needs identified by communities themselves. Second, they did not establish a minimum community benefit expenditure level for hospitals subject to the requirement. Third, they failed to end the hospital practice of allocating these expenditures to their Medicaid shortfall, the difference between their costs and what Medicaid pays (MACPAC, 2023). As a result, while hospitals may be required to undertake a public planning process focusing on the communities they serve, they can capture community benefit expenditures as offsets to Medicaid discounts and revenue-enhancing services such as advanced cancer treatment centers. These are of value to patients but perhaps not to communities in need of access to basic health care, which tend to include a disproportionate percentage of minoritized populations. Some states have imposed stricter limits on hospitals’ community benefit expenditure and accountability practices, but federal law remains highly permissive (Atkeson and Higgins, 2021).

IRS enforcement of the 2010 amendments has been limited. The agency also has not taken steps to pursue more rigorous community benefit spending rules, place limits on the expenditures that can be allocated to Medicaid shortfall, or ensure that hospital community benefit expenditures align with the communitywide health needs identified in CHNAs. Evaluations of community benefit and health improvement activities show wide variation in hospital community benefit performance (Lown Institute, 2024). Among tax-exempt nonprofit hospitals in 2018, increased spending on community

___________________

19 See https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/STATUTE-100/pdf/STATUTE-100-Pg82.pdf, (accessed April 29, 2024).

20 See https://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/text/26/501 (accessed April 29, 2024).

21 See https://www.law.cornell.edu/cfr/text/26/1.501(r)-3 (accessed April 29, 2024).

benefits was associated with provision of more patient-focused and total social care services (Iott and Anthony, 2023). Medicaid shortfalls continue to make up a considerable proportion of total community benefit spending by nonprofit hospitals, even those with substantial positive financial margins (Bai et al., 2022).

The Civil Rights Amendments

The ACA included landmark reforms to civil rights laws for health care. The amendments address all forms of discrimination, both intentional discrimination and the far more extensive problem of what the law calls “disparate impact,” the policies and practices that appear neutral but have a discriminatory effect (Chandra et al., 2017). For example, when a hospital relocates from an urban area to a more affluent suburb, the result is less access to care for publicly insured and uninsured inner-city residents. Similarly, hospital systems may close less profitable hospitals serving rural minoritized communities. An intent to discriminate may be missing, but the impact is real. Thus, disparate impact principles would focus not on preventing the move but rather on mitigating discriminatory impact, such as ensuring that the population remains anchored to care with a community facility that is integrated into the hospital system.

The ACA civil rights amendments did not alter the concept of disparate impact or lessen the challenges associated with proving disparate impact claims. But they were powerful, nonetheless. The ACA not only incorporated laws barring health care discrimination based on age, disability, race, color, or national origin into a new framework exclusively focused on health care but also broadened the range of protected classes to include sex, excluded from earlier health care discrimination laws. Second, the amendments brought a higher degree of intersectionality to civil rights and health care, which was a key advance given the special discrimination risks faced by people who are disadvantaged by multiple characteristics related to race and sex.

Third, to ensure that all parts of the health care system would be subject to civil rights protections, the amendments expanded the scope of nondiscrimination laws to encompass any part of the health care system receiving any federal financial assistance (Ziama, 2022), including individual facilities and activities that receive federal funding, such as hospitals, nursing homes, or state Medicaid programs, and entire enterprises, such as nationwide insurance companies, if any part of them receives federal funding. Thus, the law applies to nationwide health benefits companies that insure or administer health plans across multiple markets if those markets include federally

funded activities, such as Medicaid managed care, subsidized marketplace, CHIP, or Medicare Advantage plans. Finally, the amendments preserved all remedies available under civil rights laws, extending them to the newly expanded range of discriminatory practices.

Although the intent of the amendments was to reduce and eliminate inequities, little progress has been made in implementing and enforcing them. Successive rules have been subject to repeated legal challenges by covered entities seeking to limit the scope of the law and advocates focused on full implementation (Musumeci et al., 2020), and chronic underfunding has left the Office for Civil Rights (OCR) with a massive complaint backlog (NASEM, 2024). Over the years, presidential administrations have varied in the degree of emphasis placed on civil rights and health care matters, ranging from the scope of the meaning of discrimination and curbing discrimination on the basis of religion, sexual orientation, or gender identity.

This absence of ongoing routine data collection that captures disability, race, sex, and age characteristics of people served by covered entities has increased the challenges facing the federal government or private claimants as they attempt to identify potentially discriminatory patterns of health care that merit closer examination. The absence of routinely collected data at the point of care also makes ongoing analysis challenging. The Office of Management and Budget has updated the official race and ethnicity classification system used by all federal programs.22 However, this initiative alone, although important, does not address the underlying failure of agencies charged with enforcing nondiscrimination in federal health care programs to require covered entities to routinely provide race and ethnicity data on an ongoing basis.

For this reason, civil rights claims alleging disparate treatment (the vast majority of civil rights claims in recent decades) needs to rely on specialized, isolated studies or data collection efforts rather than routinely collected information that would enable documenting inequality of access or availability. The absence of enforcement and funding also means that the HHS OCR maintains no ongoing, published complaint system comparable to the routine data collection systems that characterize civil rights oversight of educational activities (NASEM, 2024). The investigation process itself remains opaque and withholds information regarding complaints, ongoing investigations and findings, and resolution.

Table 4-1 lists ACA provisions and effects on racial and ethnic health care inequities.

___________________

22 See https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/FR-2024-03-29/pdf/2024-06469.pdf (accessed April 29, 2024).

| Key Provision | Implications for Racial and Ethnic Health Inequities |

|---|---|

| Private Insurance Reforms |

|

| Medicaid |

|

| Medicare |

|

| Reforming Health Care |

|

| Prevention and Public Health |

|

| Key Provision | Implications for Racial and Ethnic Health Inequities |

|---|---|

| Strengthening the Community Health Obligations of Tax-Exempt Hospitals |

|

| Civil Rights Amendments |

|

Structural Limitations of the ACA

Although the ACA introduced far-reaching changes to the nation’s health care system, it contains important structural limitations.

First, it built on the existing incomplete and fragmented multipayer health insurance system, rather than attempting to replace it with a single, uniform source of health care financing for all. As a result, insurance coverage remains fragmented, with lower-income people—disproportionately people of color—more likely to depend on Medicaid, which has had lower payment rates compared to other forms of health insurance. This limits the number of health care providers willing to treat its beneficiaries, with notable gaps in specialty care access and care concentrated in a relatively small number of high-participation providers. Although comprehensive and structured to protect people from high-cost sharing, Medicaid also has greater enrollment instability (churn) related to enrollees’ fluctuating

___________________

23 On April 26, 2024, OCR released a final rule that serves to clarify the standards that HHS applies in implementing Section 1557. See https://www.hhs.gov/civil-rights/for-individuals/section-1557/index.html (accessed April 29, 2024).

incomes and periodic redeterminations of eligibility (MACPAC, 2021) Eligibility churn, which also affects people who must move between Medicaid and the marketplace, means that many people face frequent gaps in coverage (Sommers et al., 2016). The ACA sought to reduce churn by shifting Medicaid to an annual renewal process for people enrolled based on low income, and laws now mandate annual enrollment periods for children and permit states to provide 12 months of continuous postpartum coverage, matching the law’s long-standing, mandatory annual enrollment period for newborns. However, the ACA’s attempts at administrative streamlining apply only to beneficiaries covered based on low income alone (as opposed to coverage tied to disability or age as well). Nor does streamlining address the underlying problem of highly restrictive eligibility rules that cause enrollment disruptions even for small changes in financial or family status.

Second, the ACA partially mitigated but did not fully address the problem of health care affordability. Despite major advances in preventive care financing, expanded coverage, and a ban on annual and lifetime coverage caps, insurance often fails to adequately protect people against high health care costs (Collins et al., 2023). These costs, which disproportionately affect lower-income individuals, especially those in poorer health, result from arbitrary coverage exclusions and limits, tight networks that may force people to seek necessary care out of network (and thus uncovered), and high out-of-pocket costs via high deductibles, copayments, and coinsurance. Although Medicaid offers comprehensive coverage and provides the strongest cost-sharing protections, coverage exclusions for adults are common, particularly for routine vision, dental, and hearing care. Medicaid is principally administered through managed care plans, which maintain narrow networks and exclude out-of-network coverage for otherwise-covered services except for family planning and emergency care, narrowly defined.

Third, the ACA continues to leave more than 20 million people ineligible for affordable coverage. Although it established a pathway for recently arrived legal immigrants excluded from Medicaid as a result of the 1996 welfare reform legislation,24 immigrants remain disproportionately uninsured. Unauthorized immigrants remain without a pathway to affordable coverage25 other than for narrowly defined emergency care. Because they are excluded from the health insurance marketplace, they cannot secure its coverage at any price; their only recourse is to buy full-priced insurance off the marketplace. As of July 2023, 12 states plus the District of Columbia provide comprehensive state-funded coverage to income-eligible

___________________

24 See https://aspe.hhs.gov/reports/personal-responsibility-work-opportunity-reconciliation-act-1996 (accessed April 29, 2024).

25 See https://aspe.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/migrated_legacy_files//43811/ib.pdf (accessed April 29, 2024).

children regardless of immigration status, and five states plus the District of Columbia cover income-eligible adults regardless of immigration status (KFF, 2023c).

Fourth, the ACA contained extensive authorized revisions to a wide range of health professions training programs; however, unlike the public health and CHCs and teaching health centers reforms, the workforce amendments were not attached to a mandatory spending source. Some gains likely have occurred through the discretionary appropriations process in the years since enactment, although whether these gains have kept pace with inflation is unclear. But the lack of designated, mandatory funding has hindered the ACA’s vision of comprehensive change in how health professionals are defined, trained, and prepared to work in a dramatically changed system serving a multiracial, multicultural population through integrated, patient-centered approaches spanning health care, social services, and population health.

Implementation Shortcomings of ACA

Beyond structural limitations, the ACA implementation process has also limited the law’s effectiveness. Many challenges have arisen with implementing a complicated, high-profile law. For its civil rights protections, serious underfunding has limited enforcement, and repeated litigation aimed at stopping implementation has essentially left the law without a comprehensive regulatory policy for implementation, a critical step given its complexity (NASEM, 2024).

Overall, since 2010, the nation has witnessed over 2,000 judicial challenges aimed at slowing implementation or overturning key aspects of the law (Gluck et al., 2020). Some of its most far-reaching elements have been blunted by the courts, most notably the 2012 decision by the Supreme Court that preserved the ACA while effectively converting the Medicaid expansion from a nationwide reform with universal adoption into a state option (Lyon et al., 2014). Similarly, the Court for the first time recognized religious freedoms in corporations and upheld their claim of exemption on religious grounds from ACA’s contraceptive coverage guarantee, a decision with important implications for other preventive benefits to which more than 150 million people are entitled. The reach of the contraceptive case may be tested in a separate case, eventually expected to reach the Supreme Court, that challenges the constitutionality of the ACA’s free preventive benefit guarantee, particularly pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) for people who are HIV positive (Sobel et al., 2023).

Furthermore, the law’s civil rights protections against discrimination based on sex and other aspects of this reform have yet to be implemented through federal regulation. Despite these challenges, the ACA has succeeded

in bending the federal health care legal framework toward greater health equity. Through executive orders, the Biden administration has made its health equity aspects a principal theme of efforts to implement and enforce its provisions.26

Post-ACA Legislative and Regulatory Developments

Beyond the ACA, federal laws have continued to evolve, not only to strengthen the ACA but also in response to major public health challenges, including the COVID-19 pandemic and its aftermath; maternal and child health issues, especially maternal mortality; and the worsening addiction and mental health crises. Reforms include a state option, in response to the maternal mortality crisis (Hoyert, 2023), to provide 12 months of postpartum coverage (Clark, 2023), and establishing mandatory annual enrollment periods for children under 19 to prevent coverage and care disruption (Vasan et al., 2023). Legislation enacted in 2020 restored Medicaid eligibility for citizens of Compacts of Free Association27 communities, which include the Republic of the Marshall Islands, Federated States of Micronesia, and Republic of Palau (KFF, 2023d).

Medicaid reforms as part of the Families First Coronavirus Response Act during the COVID-19 assured that throughout the federal Public Health Emergency (PHE) period (Tolbert and Ammula, 2023), Medicaid beneficiaries would remain continuously enrolled without risk of coverage loss owing to normal coverage “churn” tendencies (even slight changes in family income or living circumstances can lead to coverage loss). With the end of the PHE, federal legislation at the end of 2022 ordered a major unwinding of continuous enrollment. That process began in April 2023, yielding large-scale coverage losses surpassing 19 million children and adults as of March 2024 (KFF, 2024b). The substantial loss of Medicaid coverage for beneficiaries in every state (some to a far greater degree than others) may be especially significant for minoritized populations because of their disproportionate reliance on Medicaid as their principal (or exclusive) source of health insurance. The impact of unwinding may be especially severe in the Medicaid nonexpansion states, which have chosen not to offer Medicaid for all low-income working-age adults. This has certain populations, such as young adults and postpartum women, losing coverage without any remaining coverage pathway.

___________________

26 See https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/presidential-actions/2021/01/20/executive-order-advancing-racial-equity-and-support-for-underserved-communities-through-the-federal-government/ (accessed April 29, 2024).

27 See https://crsreports.congress.gov/product/pdf/IF/IF12194 (accessed April 29, 2024).

Congress also strengthened Medicaid coverage for addiction treatment and recovery28 and in 2014 established Certified Community Behavioral Health Clinics (McMullen and Roach, 2020) to more comprehensively address the mental health and addiction needs of Medicaid beneficiaries and other minoritized populations. In addition, Congress enacted changes aimed at easing the transition from incarceration back to the community by enabling states to commence coverage prerelease and arrange for care continuity once released (National Conference of State Legislatures, 2023). For children in correctional institutions, these changes are mandatory and designed prevent losing preincarceration coverage while assuring immediate reinstatement upon release (National Conference of State Legislatures, 2023).

Beyond legislative reforms, the Biden administration also has used demonstration authority to promote health care reforms that build systems that can better address both clinical needs and HRSNs, such as housing supports and nutrition (Guth, 2022). The administration also has encouraged states to invest in reforms that can strengthen health and health care during and after the transition from incarceration to the community. In 2023, the administration launched a prison reentry demonstration initiative29 that provides states with additional resources to develop community reintegration programs serving Medicaid beneficiaries released from carceral settings to address physical and mental health conditions, such as substance use disorder (SUD), that significantly increase the risk of incarceration.

Section 1115 Medicaid Demonstrations

In addition to the ACA expansion demonstrations, successive administrations have used Section 1115 authority to achieve other goals. The prison reentry demonstrations offer an example of how Section 1115 can be used to enhance health equity. By contrast, demonstrations launched between 2017 and 2021 enabled states to impose work requirements as a condition of Medicaid eligibility. Before being enjoined by the federal courts, the work demonstrations were criticized in several respects: for resting on a faulty premise regarding low-income people and their alleged failure to work; permitting states to adopt demonstration models that lacked basic operational safeguards to guard against erroneous coverage denial and loss; and failing to adhere to evaluation protocols, such as collecting reliable baseline measures (MACPAC, 2018). As the federal courts intervened, a landmark study

___________________

28 See https://www.congress.gov/115/plaws/publ271/PLAW-115publ271.pdf (accessed April 29, 2024).

29 See https://www.cms.gov/newsroom/press-releases/hhs-releases-new-guidance-encourage-states-apply-new-medicaid-reentry-section-1115-demonstration (accessed April 29, 2024).

of Arkansas’s initial demonstration of Medicaid work requirements (which lasted 7 months before being enjoined by a federal court) showed that it produced no employment gains and that over 95 percent of those who lost coverage, principally because they could not navigate the state’s complex work requirement reporting rules, remained entitled to coverage because they either were working or qualified for an exemption (Rosenbaum, 2018; Rosenbaum et al., 2019; Sommers et al., 2019).

The Biden administration ended all work experiments except in Georgia, which was allowed to proceed with a Medicaid expansion demonstration that couples ACA expansion with compelled work rules (Rosenbaum, 2023). A federal court rejected the administration’s termination because, unlike earlier demonstrations in states that already had expanded Medicaid, the Georgia experiment was part of its limited expansion of Medicaid. In defending its decision to end the Georgia experiment, the Biden administration cited health equity concerns. The court decision specifically rejected health equity as a legal basis for approving or denying Section 1115 demonstration projects, and health equity has since fallen away as a specific, stated goal or condition of Section 1115 demonstration approvals (Rosenbaum, 2023). Compelled work remains a subject of legislative debate. Work as a Medicaid requirement was an element of the 2017 Congressional debate over the future of the ACA, and in 2023, the House of Representatives included this condition as part of its federal debt ceiling negotiations.

Beyond efforts to promote community integration following incarceration, the Biden administration has used Section 1115 to pursue HRSN demonstrations that offer states additional federal funding to develop systems of care that can integrate health and social services, along with the flexibility to invest this funding in services outside the traditional scope of medical assistance for which federal funding is available (e.g., nutrition services, housing supports, and other HRSNs).30 Recognizing the problem of low physician payment rates, CMS, in approving state HSRN demonstrations, has set certain minimum expectations regarding payment for primary care, obstetrics, and behavioral health (80 percent of the applicable Medicare rate).

Medicaid Managed Care

Most state Medicaid programs administer their state plans through contracts with companies that offer comprehensive coverage and operate on a financial risk basis. Known as “managed care organizations” (MCOs), these companies undertake both coverage and care duties according to

___________________

30 See https://www.cms.gov/newsroom/press-releases/cms-approves-new-yorks-groundbreaking-section-1115-demonstration-amendment-improve-primary-care (accessed April 29, 2024).

detailed contractual requirements that rest on a broad federal regulatory framework that offers considerable flexibility to both states and plans to shape their systems. In 2021, MCOs served 74 percent of all Medicaid beneficiaries across 41 states and the District of Columbia; 33 states and the District of Columbia rely exclusively on comprehensive MCOs (Hinton and Raphael, 2024). Additionally, MCO payments accounted for over half of total Medicaid spending. MCOs also effectively function as the nation’s pediatric health care system for the poorest children; in 36 states, at least 75 percent of all Medicaid-insured children were enrolled in managed care (Hinton and Raphael, 2024).

In contrast to Medicare Advantage, the federal government regulates Medicaid managed care relatively lightly, leaving considerable discretion to states and plans themselves (Rosenbaum et al., 2023b). States, in turn, vary in their approach to regulation and oversight. Systematic evidence on performance in crucial matters of health care access, quality, and health equity is lacking, as are detailed, systemwide data on use and health outcomes. One study by federal investigators has documented extensive constraints imposed by some of the largest MCOs on access to covered services through use management strategies (Office of Inspector General, 2023). The Department of Justice has sued one state for failing to ensure that plan. Members with disabilities receive coverage to which they are entitled.31 In general, states tend to take a deferential approach to plan operations and oversight. They give contractors considerable discretion over coverage and care, similar to regulatory oversight of qualified health plans sold in the subsidized marketplace.

Immigrant Access to Health Care

Immigrants experience high rates of health care discrimination and exclusion. They are significantly less likely to have a usual source of care or report a physician visit within the previous 12 months, go without needed medical care (KFF, 2023b), and remain one of the most uninsured groups. Even among fully documented immigrants, the uninsurance rate is three times higher than for citizens. Nearly half of undocumented immigrants lack coverage (KFF, 2023b), and their only option is full-priced insurance plans outside the marketplace, where regulatory standards are effectively nonexistent for coverage and cost sharing, unless states have chosen to more aggressively regulate their general insurance markets.

Fear of deportation for using public benefits to which immigrants may be entitled escalated as a result of a Trump administration rule broadening

___________________

31 See https://www.justice.gov/opa/pr/court-finds-state-florida-violates-americans-disabilities-act-institutionalizing-children (accessed April 29, 2024).

the conditions under which the lawful use of Medicaid could be considered evidence of being a deportable “public charge.”32 Ultimately, the rule was overturned by a federal court (Howe, 2022), but not before its adoption had a “chilling effect” on the use of essential health and social services that persists (Batalova et al., 2018; Bernstein et al., 2020; Chen et al., 2023).

The ACA provided an important benefit by making subsidized health plans available to legal immigrants, including otherwise-eligible immigrants barred from Medicaid because of the 5-year waiting period. In 2023 the Biden administration expanded the definition of legal status to include DACA recipients who had been considered undocumented and therefore ineligible for Medicaid and marketplace coverage (Rosenbaum and Casoni, 2023).

Federal law permits states to waive the 5-year waiting period for legal immigrant children and during the pregnancy and postpartum period and to insure undocumented pregnant people through a special unborn child option under CHIP (Clark, 2020). Most states now use a combination of these options to insure immigrant pregnant people and children, but many states have not acted. The DACA policy changes are mandatory and nationwide (KFF, 2023c).

Medicaid barriers go beyond excluding undocumented immigrants from all but emergency care and the 5-year waiting period for legal immigrants. The Bush administration imposed new legal status documentation requirements as part of the Medicaid enrollment process (GAO, 2007). The rules were associated with immediate and widespread loss of coverage in multiple states among children living in immigrant households. This approach was replaced by a more streamlined and less intrusive documentation process, but the problem of documentation remains a barrier to use of health services for eligible immigrants.

IMPACT OF POLICIES AND LEGAL INTERVENTIONS

In the context of the vast legal and policy landscape and their substantial changes since 2003, this section briefly summarizes the impact of political, legislative, and judicial action at the federal, state and territorial levels that address health care inequities.

Over the past 2 decades, many states have recognized racial and ethnic inequities in insurance coverage and attempted to extend coverage to uninsured or unstably insured individuals. Policy makers have expanded their Medicaid programs to narrow these gaps. One such expansion that has been studied extensively was Oregon’s pre-ACA initiative. The state randomly

___________________

32 See https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/FR-2019-08-14/pdf/2019-17142.pdf (accessed April 29, 2024).

selected low-income uninsured adults through a lottery and invited them to apply for Medicaid coverage in 2008, which became known at the Oregon Health Insurance Experiment. Findings show that Medicaid coverage reduced financial burden and improved health care outcomes (Baicker et al., 2013; Finkelstein et al., 2012), increased health care use, including for primary and preventive care services (Baicker et al., 2013; Finkelstein et al., 2012); prescription medication use (Baicker et al., 2013; Baicker et al., 2017; Baicker and Finkelstein, 2018; Finkelstein et al., 2012); and emergency department visits (Taubman et al., 2014). While Medicaid coverage did not significantly improve some physical health outcomes (Baicker et al., 2013), it did significantly improve mental health (Baicker et al., 2013; Baicker and Finkelstein, 2018) and self-reported health (Finkelstein et al., 2012). Findings from Oregon and other early state Medicaid expansions such as in Massachusetts provided much of the evidence that informed the ACA Medicaid expansions.

For minoritized populations who use Medicaid and other public insurance at higher rates than White populations, Medicaid expansion has substantially narrowed, but not eliminated, racial and ethnic disparities in coverage and access to care (Buchmueller and Levy, 2020; Buchmueller et al., 2016; Chen et al., 2016; Hill et al., 2024; McMorrow et al., 2015). The expansion has been shown to shrink racial and ethnic inequities in preventable hospitalizations and ED visits between Black and White nonelderly adults (Moriya and Chakravarty, 2023). Black and Hispanic individuals were much more likely than White individuals to report that the ACA had personally helped them (Sommers et al., 2017). However, they reported continuing worse quality of care than White individuals. A review of 43 methodologically rigorous studies documented evidence of improvements in health status, chronic disease, maternal and neonatal health, and mortality (Soni et al., 2020) and improvement in perceptions of care among racial and ethnic minoritized populations (Soni et al., 2020), but it is important to emphasize that many studies show that inequities in access to care and health persisted following Medicaid expansions (Buchmueller and Levy, 2020; Courtemanche et al., 2019; Lee et al, 2021). However, no studies were identified that found increased clinically meaningful inequities as a result of the ACA Medicaid expansion.

Thus, studies suggest that ACA coverage expansions had positive impact on many, but not all, racial and ethnic inequities in health care. Evidence is substantial of improved equity in health insurance coverage and in health care access and use. Furthermore, some evidence shows improved health outcomes, including reduced mortality among middle-aged adults (Miller et al., 2021). The research on the impact of ACA policies on inequities is more limited than that on overall effects across all individuals regardless of race and ethnicity, partly as a result of data and methodological limitations.

In addition, a number of studies have sought to quantify the impact of ACA provisions that eliminate cost sharing for preventive services in both private insurance and Medicaid expansion. A report from the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation estimated that in 2020, the ACA provision benefited more than 150 million people with private insurance, 20 million enrollees in Medicaid expansion, and 61 million Medicare beneficiaries.33 A substantial body of literature has demonstrated reductions in use of health services in response to cost sharing generally (Artiga et al., 2017), and patients in low-income areas may be particularly responsive to modest changes in cost sharing (Chernew et al., 2008). Since the ACA, studies on the effects of this mandate on use have shown varied results across specific services based on a variety of study designs. Norris and colleagues (2022) reviewed 35 articles and found that a majority reported increased use of services associated with eliminating cost sharing; the review noted that “low-socioeconomic groups and those who experience the greatest financial barriers to care appear to benefit the most from cost-sharing elimination” (Norris et al., 2022).

Health Care Provider (HCP) Payment Policies

HCP payment policies are potentially integral to health equity through public insurance programs (Medicare and Medicaid), private insurance provided through employers or ACA marketplace plans, and other private insurance plans purchased by individuals. These policies include adjusting health care provider payment rates, payment for specific services, uniform payments across groups (e.g., capitation), pay-for-performance (P4P), P4P payments that adjust for social risk scores, and incorporating health equity in value-based payment systems.

CMS has begun to focus explicitly on ways that health equity can be advanced via Medicare and Medicaid payment policies related to quality and value through its “Rewarding Excellence for Underserved Populations” initiative announced in 2023 (Jacobs et al., 2023). Until recently, however, payment policies—including traditional fee-for-service payments and more recent alternative payment models—have rarely focused on promoting health equity by race, ethnicity, or socioeconomic status. In 2016, for example, a systematic review of 27 studies published between 1980 and 2013 assessed how reimbursement policies affect socioeconomic and racial inequities in access, use, and quality of primary care and found little evidence that they had influenced primary-care-related inequities (Tao et al., 2016).

___________________

33 See https://aspe.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/documents/786fa55a84e7e3833961933124d70dd2/preventive-services-ib-2022.pdf (accessed April 29, 2024).

Medicaid Provider Payment Rates

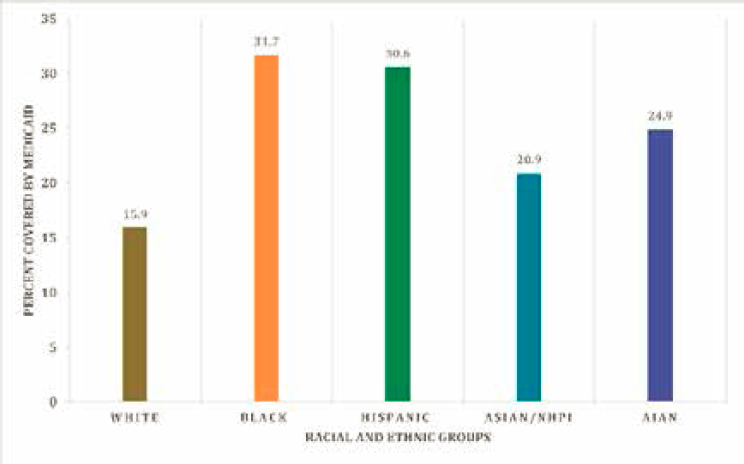

As shown in Figure 4-1, Medicaid disproportionately serves children and nonelderly adults who are Black, Hispanic, American Indian or Alaska Native (AIAN), and NHPI (Donohue et al., 2022). Medicaid enrollees have more limited access to physicians for primary care and specialty care than enrollees in most private insurance plans, partly because payment rates are substantially lower than Medicare or private insurance payments to HCPs (Tipirneni et al., 2019) with the Medicaid-to-Medicare fee ratio often 0.50–0.80 (Zuckerman et al., 2021). HCP payment gaps between Medicaid and private insurance are substantially larger.

In a few instances, policy has increased Medicaid payment rates to match other payment rates (rate parity), and limited evidence on equity is available from these efforts, particularly related to the temporary change in Medicaid payment rates for primary care to match Medicare levels in

NOTE: Numbers calculated from nonelderly population estimates by race/ethnicity, 2021.

SOURCES: U.S. Census Bureau 7/1/2021 National Population Estimates released June 2022 at https://www2.census.gov/programs-surveys/popest/datasets/2020-2021/national/asrh/, together with Medicaid coverage estimates from CPS ASEC reported at https://www.kff.org/medicaid/state-indicator/medicaid-distribution-nonelderly-by-raceethnicity

2013 and 2014 (MACPAC, 2024). Early research found that this policy did not expand the number of physicians accepting Medicaid patients (Decker, 2018), but it did increase the likelihood that those already accepting Medicaid patients would accept more (Polsky et al., 2015). In a subsequent study of the ACA-authorized Medicaid primary care fee increase, individuals dually eligible for Medicaid and Medicare experienced a substantial increase in primary care services, nearly eliminating the gap for low-income adults relative to higher income Medicare beneficiaries not enrolled in Medicaid (Cabral et al., 2021). A more recent study of the ACA-authorized Medicaid primary care fee increase eliminated a substantial portion of the disparity in access among adults and fully removed it among children; it was also associated with improvements in health care use and in self-reported health (Alexander and Schnell, 2019).

Payment for Specific Services

Payment to increase access to specific services has had mixed results regarding racial and ethnic inequities. For example, Medicaid direct payment to hospitals to increase automatic long-acting reversible contraception after delivery increased access for women (Steenland et al., 2022). A study of an Oregon law that mandated coverage for reproductive health services showed that state policies ensuring no-cost comprehensive coverage can mitigate ethnic disparities in contraception use (Cohen et al., 2023), but Medicare’s implementation of cost-sharing parity for mental health and SUDs did not narrow gaps and eliminating drug caps exacerbated racial differences in antidepressant use among certain dual enrollees.

Risk-Adjusted Capitation Payments in Medicare

The use of risk-adjusted payments in Medicare Advantage, that is, payments that take into account a range of health conditions, has had mixed effects on racial inequities. Between 2006 and 2011, managed care plans in the West, particularly Kaiser health plans, eliminated disparities between Black and White beneficiaries for blood pressure control for hypertension (Ayanian et al., 2014), glucose control for diabetes, and cholesterol control for heart disease while achieving the highest overall quality of any region on these measures. In contrast, managed care plans in the Northeast, Midwest, and South had substantial and persistent racial disparities in these key outcomes and lower levels of quality for both Black and White beneficiaries (Ayanian et al., 2014). An earlier study found that benefits and costs for minoritized individuals in Medicare managed care were comparable to those in traditional fee-for-service Medicare (Balsa et al., 2007).

Financial Incentives to Promote Equity in Medicaid Managed Care

A few state Medicaid programs have begun to incorporate health equity measures and incentives in their managed care payment systems (Crumley and McGinnis, 2019). In Michigan, for example, Medicaid managed care plans must use equity measures related to social determinants of health (SDOH) and inequities in low birth weight as part of value-based payments. In Oregon, Medicaid coordinated care organizations (CCOs) are required to track disparities in ED use among beneficiaries with mental illness (Crumley and McGinnis, 2019). Consistent with the concept of building race and ethnicity measures into routine health care data collection, Louisiana is requiring Medicaid managed care plans to stratify performance measures by race, ethnicity, and disability status. For each of these recent changes in state policies, evidence is not yet available to assess whether racial and ethnic inequities have narrowed.

Pay-for-Performance (P4P)

Payment policies that reward performance may incentivize providers to avoid serving patients with more complex health needs for whom achieving high-performance scores may be more difficult and may also lead to financial difficulties for providers serving those patients (Shakir et al., 2018). For example, a study of the Medicare Merit-Based Incentive Payment System, Medicare’s largest P4P program, found in 2019 that provider groups disproportionately serving racially minoritized patients were more likely to receive financial penalties (Johnston et al., 2021). Similarly, a study of the Medicare Value-Based Payment Modifier identified that it may worsen health care disparities by penalizing clinicians who care for greater numbers of low-income beneficiaries who are dually eligible for Medicare and Medicaid (Roberts et al., 2018).

Incorporating Health Equity in Value-Based Payment Systems

Adjusting for social risk factors in payment can help overcome the P4P pitfalls, narrow equity gaps (Ash et al., 2017), and better match payments to address the care needs of minoritized populations (Alcusky et al., 2023), particularly if financial resources are allocated to support organizations serving minoritized populations. Medicare’s traditional ACO models have not focused on providing such support for underresourced provider groups but rather emphasized controlling costs (Gondi et al., 2022). In the new Medicare ACO Realizing Equity, Access, and Community Health program, up-front investments have been incorporated in payments to provider groups serving more disadvantaged beneficiaries, which will be critical to enable them to devote resources early on to addressing HRSNs.

CMS has begun encouraging states to use innovative payment policies to address the HRSNs of Medicaid beneficiaries, mainly through Section 1115 demonstration projects, and outlined plans to incorporate health equity in value-based payment programs (Jacobs et al., 2023). In the Oregon Medicaid program, value-based payment through coordinated care organizations has shown promise in reducing disparities in primary care and preventive services for Black and AIAN enrollees relative to White enrollees (McConnell et al., 2018). However, these types of payment policies may also contribute to structural inequities. For example, in communities with more Black Medicare beneficiaries, physicians are less likely to participate in Medicare ACOs (Yasaitis et al., 2016). Similarly, double-bonus payments are lower for Medicare Advantage plans in counties with more Black and Hispanic enrollees, which may increase cost sharing and reduce benefits for them (Markovitz et al., 2021, 2022). Adjusting value-based provider payments for the social risk burden of their patients may help to counter long-standing structural inequities in payment policies (ASPE, 2016; Buntin and Ayanian, 2017; Joynt et al., 2017).

State and Federal Policies Related to Social Determinants of Health (SDOH)

Many state policies affect SDOH in ways that may affect health care equity, such as by reducing income inequities. State policies related to family cash payments under the Temporary Assistance to Needy Families program (the 1996 successor to Aid to Families with Dependent Children, a legal entitlement program that was replaced with a highly flexible state block grant) can reflect racist legacies of cash assistance, with more Black children living in states with less generous assistance policies (Heffernan et al., 2018; Thompson et al., 2023). In contrast to welfare cash assistance, financial gains since the 1993 expansion of the earned income tax credit (EITC) were concentrated among Black families (Hardy, 2022). As a result, EITC expansions are associated with statistically significant improvements in children’s health among Black families only (Batra et al., 2022; Komro et al., 2019). Research shows that the child tax credit (CTC), was available to more White than Black children pre-2021 because of eligibility criteria (Goldin and Michelmore, 2022). The 2021 expansion extended eligibility to those without reported earnings, but this did not eliminate disparities in CTC receipt (Pilkauskas et al., 2022). However, parents of Black children have evidence of improved mental health related to the CTC (Batra et al., 2023).

In summary, health care payment policies of public and private insurers are evolving in numerous ways to address racial and ethnic inequities in health care. However, their impact on health equity remains mixed when evaluated and more often unclear for policies that have not yet been well studied. Thus, rigorous studies of the equity effects of these policies are an important priority moving forward.

HEALTH CARE EQUITY AND THE COURTS

Historically, U.S. courts have played a crucial role in defining and enforcing federal and state laws bearing on equity in health and health care. This has become more pronounced since Unequal Treatment, as the judiciary has chosen to more strongly weigh in on a range of issues, including national health reform; the exercise of governmental power during public health emergencies; judicial oversight of agency action; remedies for past discrimination based on race, color, and national origin; and the scope of individual rights related to health care access.

Several cases decided by the U.S. Supreme Court merit special consideration in this report because of not only their legal significance but also their far-reaching implications for health care equity. In National Federation of Independent Business v Sebelius,34 the Court upheld the constitutionality of the ACA individual coverage mandate. (This ultimately was repealed in 2017 as a proper use of taxing powers to incentivize purchasing affordable health insurance but struck down the nationwide Medicaid expansion). The Court ruled that it was an unconstitutional coercion and exceeded Congress’s powers to condition federal funding on state choices over the structure of their Medicaid programs. The decision effectively transformed the nationwide ACA Medicaid expansion into a state option.

Nearly 12 years after the decision, 10 states have declined the expansion despite significant financial incentives (KFF, 2024c). Texas and Florida account for nearly two-thirds of all people left without a pathway to coverage because their household incomes are below the 100 percent of FPL threshold for marketplace subsidies, but they fail to qualify under traditional Medicaid programs. Many of these are people of color. An estimated 1.5 million people would qualify if their states expanded Medicaid eligibility, and those excluded from Medicaid in the remaining nonexpansion states are disproportionately minoritized people (Drake et al., 2024).

In Burwell v Hobby Lobby Stores,35 the Supreme Court extended religious freedom rights to corporations for the first time. Several religious employers objected on religious grounds to including ACA’s free contraceptive coverage guarantee in their health benefit plans arguing that it would make them complicit in sexual activity they opposed on religious grounds. In ruling for the employers, the Court first held that corporations opposing federally mandated health care benefits on religious grounds could invoke the federal Religious Freedom Restoration Act (RFRA) enacted in 1993 to guarantee individuals a heightened level of religious freedom protection against government regulation. Second, the Court held

___________________

34 See https://www.loc.gov/item/usrep567519/ (accessed April 29, 2024).

35 See https://www.law.cornell.edu/supremecourt/text/13-354 (accessed April 29, 2024).

that even if the federal government could satisfy RFRA’s compelling interest standard and demonstrate its heightened concern about the need for unfettered access to family planning services, it nonetheless failed to show that a contraceptive coverage mandate represented a narrowly tailored law that reflected the least restrictive means of ensuring contraceptive access. The Supreme Court decision in Little Sisters of the Poor v Commonwealth of Pennsylvania (2019) extended and reinforced the Burwell v Hobby Lobby Stores decision, allowing employers to claim not only a religious exemption but a moral one (Keith, 2020).

An additional ACA case—now at the appellate court stage before the Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit and likely to reach the Supreme Court—is Braidwood Management v Becerra.36 Several individuals have sought to overturn the entire ACA preventive benefit guarantee for both themselves and the nation as a whole. The basis for many of their claims is constitutional—that U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommendations could not be legally binding on insurers because the Task Force structure and operations violated the Constitution, the HHS Secretary lacks the power to cure the constitutional violation by adopting the recommendations as binding coverage standards, and Congress exceeded its own powers by delegating detailed coverage decisions to HHS. In a specific challenge to covering free HIV preventive services, the plaintiffs also make statutory religious freedom claims paralleling the Hobby Lobby case.

Should the plaintiffs prevail, virtually all privately insured individuals would lose free preventive benefits as a basic coverage guarantee, including over 150 million children and adults.37 Insurers and employer plans could respond by eliminating preventive benefit coverage entirely or reimposing cost sharing; both responses would have a significant, deterrent effect on use of evidence-based preventive care. Apart from the challenge to preventive care generally, coverage of treatment for people living with HIV could be lost on religious freedom grounds, with objectors given the power to refuse to cover PrEP just as they now can refuse to cover some or all contraceptives under the Hobby Lobby decision.

Affirmative Action and Higher Education