Ending Unequal Treatment: Strategies to Achieve Equitable Health Care and Optimal Health for All (2024)

Chapter: 5 Health Care Service Delivery

5

Health Care Service Delivery

This chapter focuses on the organization and delivery of health care services within the U.S. health care system to achieve equitable health care and optimal health for all. The chapter discusses current and emerging care delivery models, the health care workforce, the health care environment, integrating medical and social care, factors influencing individual care-seeking behavior and medical mistrust, health literacy, and health information technology. It also explores interventions that have shown to be promising for achieving equitable health care and optimal health for all. Although it is not an exhaustive review of all aspects of health care services delivery and promising interventions, this chapter discusses specific issues most relevant to health care equity. As mentioned in previous chapters, this report uses “inequities” instead of “disparities” except when citing a publication that explicitly measured disparities. In addition, the committee is aware that health—a state of complete physical, mental, and social well-being and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity—and health care—the services provided to individuals, families, and communities for the purpose of promoting, maintaining, or restoring health across settings of care—are different but inextricably linked. Furthermore, this report uses “health care system” (activities related to the delivery of care across the continuum of care) to describe the U.S. health care system as a whole and also individual health care systems. Institutional racism is reflected both at the level of the health care system as a whole and within specific health care organizations and manifests as unequal treatment and care outcomes.

HEALTH CARE DELIVERY MODELS

Public health, preventive care, and primary care in the United States have been chronically undervalued and underresourced, and most payment structures have traditionally rewarded care settings and providers who treat the sickest people. This incentive structure drives health care organization and delivery to be top heavy, with a narrow foundation of primary care and a wide array of secondary, tertiary, and quaternary care built on top, leading some experts to characterize it as a “sick care” system (Marvasti and Stafford, 2012). The deprioritization of primary care is particularly concerning given that investment in high-quality and accessible primary care is associated with improvements in population health and health care equity (NASEM, 2021a; Stange et al., 2023). This upside-down structure has long been associated with marked inequities in service access, quality, and outcomes (Dickman et al., 2017), while simultaneously increasing economic costs and worsening population-level health outcomes relative to other high-income countries (Shrank et al., 2019). The dominant paradigm in U.S. health care remains focused on the individual, centered on the clinical workforce and biomedical interventions, and characterized by a highly medicalized view that prioritizes diagnosing and treating disease (Lantz et al., 2023).

As detailed in Chapter 3, racial and ethnic inequities persist in health care access, quality, and outcomes (Doubeni et al., 2021; Lavizzo-Mourey et al., 2021). The system’s lack of progress in narrowing these inequities suggests that to achieve health care equity, the U.S. health care system requires substantive structural reforms that shift away from traditional paradigms for health care organization and delivery. Emerging models and approaches have shown early promise in reducing inequities but have not yet been implemented and evaluated across the entire system. This next section provides examples of promising models. It is worth noting that many of the promising models highlighted here are complex interventions that leverage a wide range of actors, components, and mechanisms of change. Therefore, close monitoring of fidelity for all promising models and interventions brought to scale is critical.

Person-Centered Care Delivery

Patient-centered care (PCC) represents a key element of high-quality health care service delivery and is recognized as a stand-alone dimension of health care quality (AHRQ, 2023; IOM, 2001). In addition, health care payers are increasingly prioritizing the PCC concept as part of value-based, care-oriented payment reforms (NEJM Catalyst, 2017). PCC prioritizes shared decision making (SDM) informed by open provider–patient

communication, engagement of families in the care process, care delivery aligned with cultural preferences, and consideration of the whole person, including for example psychosocial stressors in designing and implementing care plans (Epstein and Street, 2011; NEJM Catalyst, 2017), as opposed to sole reliance on physician-led decision making. Related to patient-centered care, person-centered care goes beyond collaborative care design and management of a specific condition by adopting a focus on advancing wellbeing for the whole person. The goal of patient-centered care is a functional life for the patient, while person-centered care is designed to achieve a meaningful life for the patient (Eklund et al., 2019). Person-centered care most closely aligns with the Committee’s vision for equitable health care in the United States and is adopted as terminology in subsequent sections of the report.

Research has documented racial and ethnic inequities in person-centered care domains, suggesting that broader implementation across the U.S. health care system may be a promising intervention to reduce inequities. For example, minoritized patients frequently report worse patient–provider communication (Hagiwara et al., 2019), and the prevalence of culturally and linguistically misaligned care is a well-established barrier to health equity (Bau et al., 2019).

The American Heart Association reviewed the evidence of person-centered programs for shaping a range of cardiovascular outcomes, including both clinical and functional outcomes (Rossi et al., 2023). Two such lifestyle interventions, the DREAM Project and Project IMPACT, were effective at reducing blood pressure in patients with comorbid diabetes and uncontrolled hypertension (Beasley et al., 2021). Participants received sessions with discussions with community health workers (CHWs) around individualized care needs, shared goal-setting for health behaviors, referrals to wraparound services, and materials tailored to their cultural and religious practices and beliefs about blood pressure and diabetes management (Beasley et al., 2021). Other promising person-centered interventions are effective in shaping cardiac outcomes. For example, patients who received the STROKE-CARD disease management intervention—providing digital tracking for comorbidities, cardiovascular warning signs, education, counseling, and self-empowerment—had reduced cardiovascular risk and enhanced quality of life compared to patients in the standard-of-care group (Willeit et al., 2020).

Team-Based Care

Team-based care can refer to engaging health care teams to provide integrated person-centered care, particularly for those with complex needs; expanding the workforce to include additional members of the team, such as behavioral health professionals, social workers, and CHWs; and having

team members work in innovative ways to maximize patient care. Team-based care is a central feature of high-quality primary care: “the provision of whole-person, integrated, accessible, and equitable health care by interprofessional teams who are accountable for addressing the majority of an individual’s health and wellness needs across settings and through sustained relationships with patients, families, and communities” (NASEM, 2021a).

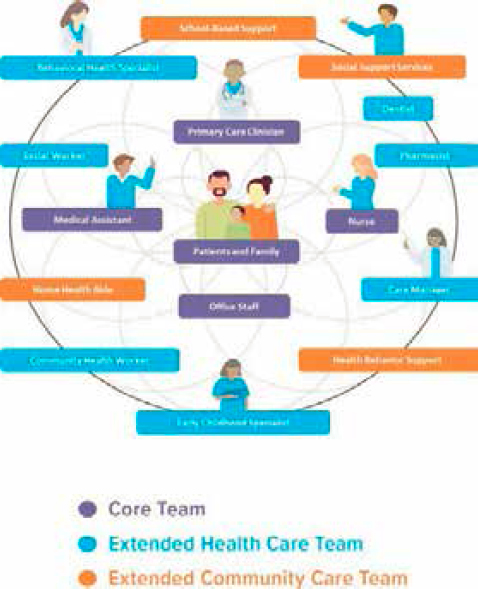

Evidence suggests that a team-based care approach may reduce health care inequities, especially when it includes members who are racially or ethnically concordant with the patient. Multidisciplinary, team-based care has been a feature of many successful interventions designed to improve health outcomes among racially minoritized populations; this strategy is one of the core features of the Roadmap to Reduce Racial Disparities in Health Care (Chin et al., 2012). Team-based care has been associated with improved care measures in the inpatient setting. Examples of improved care include increased satisfaction among hospitalized patients, reduced hospital readmission rates among high-risk populations, and reduced emergency department (ED) use. In the outpatient setting, team-based models have improved access to care, care coordination, and the quality and safety of care delivery and decreased pharmacy costs. Teams that include case managers, social workers, and behavioral health workers are better able to coordinate care, address HRSNs, provide health education, and deliver socioculturally tailored care for racially and ethnically minoritized populations (Fink-Samnick, 2019; NASEM, 2019). Teams that include CHWs, behavioral health specialists, case managers and care coordinators, pharmacists, and others who can address complex needs are more effective at providing the comprehensive, whole-person care that racially and ethnically minoritized populations disproportionately lack. Substantial evidence also indicates that patient navigators (PNs), CHWs, peer navigators, lay health advisors, promotores de salud, and similar personnel can be value-added members of the medical care team and are a particularly effective model for reaching the “hardly reached” (Knowles et al., 2023; Lohr et al., 2018; Patel et al., 2018; Sokol and Fisher, 2016). Figure 5-1 shows the composition of multidisciplinary primary care teams.

Teams that involve nurses collaborating with CHWs have been very effective at improving health outcomes, particularly in managing chronic diseases, such as diabetes. Examples include CHWs and a nurse case manager (NCM) working to control diabetes in American Samoa (DePue et al., 2013) and a CHW/nurse team working with African American patients with diabetes (Gary et al., 2009). In the first intervention, the NCM focused on high-risk patients, oversaw the CHW visits, and was the physician liaison. The CHWs helped patients with socioculturally tailored health education and self-management support. At 12 months, the intervention group had twice the adjusted odds of a clinically significant improvement in

SOURCE: NASEM, 2021a.

HbA1c of at least 0.5 percent. The second intervention randomly assigned 542 African American patients with Type 2 diabetes to either a minimal intervention group (who received reminders about preventive care) or an intensive group (who received those reminders plus individualized, culturally tailored care from an NCM and a CHW, using evidence-based clinical algorithms with feedback to primary care providers) (Gary et al., 2009). At 24 months, those in the intensive intervention group were 23 percent less likely to have ED visits.

Community-based PNs have been shown to reduce or eliminate racial and ethnic inequities in colorectal cancer screening for diverse populations. In a randomized controlled trial (RCT) of bilingual and bicultural PNs working with low-income adults served by CHCs, screening rates more than doubled for Black patients and those whose primary language was not English (Lasser et al., 2011). Similarly, significant racial and ethnic inequities in colorectal cancer screening in New York City in 2003 were eliminated by 2014 through a multifaceted citywide program in which PNs played a central role (Itzkowitz et al., 2016).

Studies have demonstrated the effectiveness of including pharmacists as part of the clinical team to improve health outcomes. One example is the Caring for Asthma in our Region’s Schoolchildren program targeting high-risk pediatric populations (Elliott et al., 2022) and a collaborative care program for veterans with depression treated at community-based primary care clinics in the Department of Veterans Affairs (Davis et al., 2011). Caring for Asthma was a pharmacist-led, multidisciplinary team program that delivered comprehensive asthma care in six elementary schools in Greater Pittsburgh (Elliott et al., 2022). Over the 3-month study period, inhaler use increased, asthma control improved, quality of life increased, and the number of children requiring oral steroids or an ED visit decreased. In the second program, veterans were randomized to usual care or collaborative care consisting of video chats with the team, supervised by a psychiatrist, and phone contact with a clinical pharmacist and registered nurses (RNs) to address medication adherence and side effect management (Davis et al., 2011). In total, 72 percent were White, 18 percent were African American, 3 percent were Native American, and 3.6 percent were from other minority groups. The usual care group had no racial differences in response rate, but in the collaborative care group, racially minoritized groups had a higher response rate than White participants. Thus, having nurses and pharmacists on clinically integrated teams is an evidence-based approach to improving racially minoritized populations’ health care and health outcomes.

Socioculturally Tailored Interventions: Bridging Health Equity and Quality Improvement

Overall, general quality improvement efforts do not improve the health of racially and ethnically minoritized populations and may exacerbate health inequity because those with more social capital and resources can access health care innovation more quickly. Health care that is socioculturally tailored (e.g., responding to the lived experience and needs of marginalized patients) and delivered by a multidisciplinary team has significant potential to reduce inequities in health care and health outcomes. Sociocultural tailoring has been a primary mechanism of improving health equity within quality improvement interventions. In a review of interventions to reduce inequities in pulmonary disease, researchers found that telehealth interventions that did not include direct contact with someone (e.g., peer, nurse educator) were often unsuccessful. In contrast, socioculturally tailored interventions delivered by CHWs, nurse coordinators, health educators, and peers aimed at leveraging telehealth were often effective (Harper et al., 2023).

In a systematic review of interventions to reduce racial and ethnic inequities in prostate cancer, all socioculturally tailored cognitive-behavioral intervention

identified to improve treatment were successful for enhancing the quality of life among racially and ethnically minoritized men (Sajid et al, 2012). Quality of life is an essential metric because of the many long-term side effects of prostate cancer treatment and the lower returns to physical and social functioning of non-White prostate cancer patients in comparison to White patients.

Culturally centered models of care are an avenue to enact systems-level approaches to advance health equity. Community birth centers, for example, are well positioned to provide culturally centered care to improve maternal health and birth outcomes for racially and ethnically minoritized populations. Roots is a community birth center that provides accessible, flexible, culturally centered, relationship-centered, out-of-hospital midwifery care and education to racially and ethnically diverse individuals and Medicaid beneficiaries (Hardeman et al., 2020). Roots is in North Minneapolis, a community with a predominantly Black or African American population, the largest racial inequities in birth outcomes in Minnesota, and the highest infant mortality rate. Half of the center’s staff are community members and identify as Black or African American, and half of midwives identify as racially or ethnically minoritized. All employees are screened and receive ongoing training to ensure they have a comprehensive understanding of structural racism and culturally centered care and experience working with marginalized communities. Roots still offers nonclinical support if health complications arise that requiring transfer to specialist settings. Roots staff stay with patients assigned to clinical teams that cannot provide culturally concordant care. In 4 years, Roots treated 284 families with zero preterm births. However, reimbursement is a significant challenge for birth centers; reimbursement systems and payment models for maternal health care are not well suited. New policies propose payment systems that can bolster support for birth centers and expand access to midwifery care, but research is needed to examine the effectiveness of these policy changes on outcomes.

Linguistically Appropriate Care

Approximately 8 percent of the population have limited English proficiency (LEP).1 LEP is defined as a limited ability to read, speak, write, or understand English.2 A large evidence base documents the potential harms to patients with LEP who face language barriers in health care settings, including inequitable health care delivery, lower patient satisfaction, and

___________________

1 See https://www.census.gov/content/dam/Census/library/publications/2022/acs/acs-50.pdf#page=4.14 (accessed March 29, 2024).

2 See https://www.lep.gov/faq/faqs-rights-lep-individuals/commonly-asked-questions-and-answers-regarding-limited-english (accessed March 29, 2024).

worse health outcomes (Pandey et al., 2021; Twersky et al., 2024). The use of bilingual clinicians and professional interpreters, rather than family or untrained interpreters, has been shown to improve health care quality, use of preventive care, and patient satisfaction. In a 2019 systematic review of patient–physician language concordance for non-English patients, 76 percent of the studies reported that at least one of the outcomes was improved (Diamond, 2019). However, 15 percent of the studies demonstrated no difference in outcomes, and 9 percent reported worse outcomes. The authors concluded that language-concordant care improved health care in the vast majority of situations.

Federal regulations have required health care organizations to make language services available to LEP patients as part of Title VI of the Civil Rights Act, which prevents discrimination on the basis of national origin, including primary language.3 Health care organizations receiving federal funds through Medicare or Medicaid should make efforts to provide services in a language accessible to LEP patients. Standards around culturally and linguistically appropriate services (CLAS) were developed in 2000.4

A national study assessing hospital compliance with CLAS standards found that it was inadequate (Diamond, 2010). For example, hospitals frequently provided information about patients’ right to receive language services, but this notification was only in English. Hospitals opted to use family members or untrained staff as interpreters. Only 13 percent of the hospitals surveyed met all CLAS standards, and 19 percent met none at all (Diamond, 2010). Accountability measures for CLAS standards will be important to enhancing language access for LEP patients and improving health equity.

Family and Life-Course Perspectives in Care

Family members represent important, yet frequently overlooked, actors intersecting with the delivery of health care services, programs, and interventions (Cheng and Solomon, 2014). Incorporating family and life-course perspectives in health services represents a key opportunity for reducing inequities and optimizing patient outcomes, particularly when health care–family partnerships can address harmful socioenvironmental influences. Several models for leveraging families in health care and health promotion exist and warrant more widespread implementation. Family-centered care models rely on health service delivery to individuals but explicitly take the family context into account at each step of designing care plans (Kokorelias et al., 2019). Whole-family service

___________________

3 See https://www.ojp.gov/program/civil-rights-office/limited-english-proficient-lep (accessed March 29, 2024).

4 See https://thinkculturalhealth.hhs.gov/clas/standards (accessed March 29, 2024).

delivery models rely on delivering health services to the family unit instead of only to the individual (Guagliano et al., 2020). Family-based intervention models are specifically designed to change family-level health behavioral norms, such as to promote healthy dietary patterns (Champion et al., 2022).

Research highlights the important role of families in shaping health outcomes (NASEM, 2016; Viner et al., 2012). Research documenting the role of family influences has been particularly robust within areas such as HIV/AIDS prevention, substance use prevention and treatment, sexual and reproductive health and, most recently, the COVID-19 pandemic response (Guilamo-Ramos, 2021; Widman et al., 2016). For example, The Families Talking Together clinic is a triadic intervention that partners health care providers (HCPs), parents, and adolescents to support adolescent sexual and reproductive health (Guilamo-Ramos et al., 2011, 2020). It demonstrated efficacy in reducing sexual risks in a clinic-based RCTs (Guilamo-Ramos et al, 2020). Numerous family-based interventions for a diverse set of health conditions could be optimized for greater impact in eliminating health inequities. This is particularly evident with populations that have documented improved efficacy of family-based intervention relative to a more individualized approach (Gallegos and Segrin, 2022).

Community-Based Care

The appreciation of the unique role that hospitals and health care systems play in addressing health and health care inequities in their surrounding communities is growing (Franz et al., 2023; Horwitz et al., 2020; Puro and Kelly, 2022). Managed care health plans and public payers, such as Medicaid, are increasingly reimbursing providers to screen patients and connect them with needed social services. As discussed in Chapter 4, the Affordable Care Act created new requirements for nonprofit hospitals to demonstrate community benefits of their operations by conducting community health needs assessments (CHNAs) every 3 years. CHNAs need to include goals and plans to address identified needs and assessment of progress metrics and need to be shared with the public. Through CHNAs, hospitals are required to channel resources to address communities’ unmet health and HRSNs. Examples of hospital and health care system initiatives that can improve community health range from collaborations with social service agencies, such as for housing, transportation, and food insecurity, to economic interventions, such as hiring community members and contracting with local businesses (Franz et al., 2023; Horwitz et al., 2020; Puro and Kelly, 2022).

However, the evidence on the impact of CHNA requirements on increased hospital community benefit spending is mixed (Fos et al., 2019; Owsley and Lindroth, 2022; Sun and Spreen, 2022). Research suggests that improving

measures of hospital contributions to community health could incentivize greater investments in community health and equity (Plott et al., 2022).

CHNA and other community-focused programs led by hospitals are not sufficient to advance health equity. Evidence is emerging that decentralizing health care delivery—shifting away from current models that bring patients into hospitals and other traditional clinical setting. Instead, care needs to be moved outside of the hospital and into the community in order to clinical sett narrow equity gaps (Abimbola et al., 2019; CMS, 2021). Some health care organizations are increasingly adopting consumer-friendly, flexible, and personalized services delivered in a growing range of non-traditional care settings (KauffmanHall, 2021), and more than half of all health care positions are projected to be in ambulatory care settings (Center for Health Workforce Studies, 2021).

Community-based care more often emphasizes prevention, health promotion, and wellness (NASEM, 2017). A systemic review affirms the utility of community-based care and highlights the importance of leveraging it particularly in minoritized populations and those experiencing the greatest health inequities (Nickel and von dem Knesebeck, 2020). Characteristics typical of community-based health care include better alignment with the needs of the target communities, engagement with communities, and the ability to integrate traditional clinical expertise with attention to social care that also addresses HRSNs (NASEM, 2017, 2019). Community-oriented primary care (COPC) is a long-standing example of this care approach. COPC was developed in the 1940s and places the focus on community-oriented care, rather than clinic-oriented care (NASEM, 2021a). By focusing on the individual over their lifetime in the context of family and community, rather than on a specific health issue, COPC aims to emphasize prevention and well care, rather than sick care. Over time, COPC has evolved to be a guiding framework for equity-focused, sustainable health system–community partnerships and has been successfully applied in various communities nationwide for decades (Hoggard et al., 2023). COPC deepens the understanding of what a specific community needs to be healthy and how individuals can achieve optimal health within their community context (NASEM, 2021a).

Scaling up community-based care models and approaches, such as COPC, will bring care closer to communities and help to ameliorate the negative health impacts of adverse SDOH. These models work to heal communities and individuals. When communities are healthier, individuals are less likely to experience adverse SDOH. When health care services are located in communities and operated in partnership with communities, it enables the integration of clinical care and social care. Chapter 6 further discusses community-centered and community-engaged care and strategies to integrate health and social care.

Multilevel Interventions

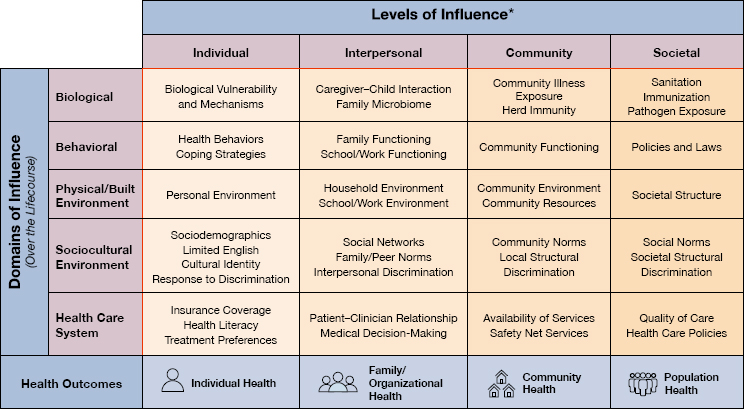

Multilevel interventions, by definition, address two or more levels of influence and may be delivered simultaneously or in sequence (Agurs-Collins et al., 2019; Brown et al., 2019). Multilevel interventions that target the causes of health inequities by focusing on the levels of influence that affect health including individual, interpersonal, community (discussed in Chapter 6), and societal levels, as outlined in the NIMHD Research Framework (see Figure 5-2), are essential to achieving health care equity and optimal health for all. They often involve collaborations between health care delivery systems, community-based organizations, public health departments, and social service agencies. Recognizing the need to intervene at various levels to more comprehensively address the complex interplay between determinants of health, NIH has called for more research that uses a multilevel approach to improve the health of vulnerable populations (Stevens et al., 2017).

In many cases, multilevel interventions will be most promising for effectively eliminating population-level inequities. For example, research on the mechanisms of SDOH demonstrates multiple levels, beyond the

NOTE: *Health Disparity Populations: Racial and Ethnic Minority Groups (defined by OMB Directive 15), People with Lower Socioeconomic Status, Underserved Rural Communities, Sexual and Gender Minority Groups, People with Disabilities. Other Fundamental Characteristics: Sex and Gender, Disability, Geographic Region.

SOURCE: https://www.nimhd.nih.gov/about/overview/research-framework/nimhdframework.html (accessed February 23, 2024).

individual-level, at which health-promoting or harming activities can occur, including the community, organizational/institutional, or broader societal levels (Guilamo-Ramos, et al., 2024). These levels are interconnected and work synergistically to affect the overall health of individuals. For example, people with asthma may fully adhere to their medication regimen yet have poorly controlled asthma if they live in neighborhoods with low air quality due to environmental pollutants. Health inequities result from interacting social and structural determinants of health. Although it is increasingly recognized that multilevel interventions are required to address health inequities, designing, implementing, and measuring the effects of multilevel interventions remains challenging. Also, more robust science is needed to determine how to best conduct multilevel interventional studies to truly know their impact on achieving health care equity and advancing optimal health for all.

THE HEALTH CARE WORKFORCE

Discussions of promising care delivery models are moot without a discussion of the health care workforce implementing those models. The health care workforce is structured to support the sick care paradigm referenced at the beginning of this chapter and does not represent the diversity of the U.S. population. As models of health care evolve to prioritize keeping people healthy and narrow equity gaps, it will be necessary to redefine the workforce to reach all segments of the demographically changing population; identify priorities for recruiting, retaining, and supporting a more diverse and representative workforce; and anticipate new workforce demands within a health care system undergoing structural reform (Pittman et al., 2021).

Traditional definitions of the health care professions focus on clinicians who deliver and bill for services, including physicians, nurses, nurse practitioners (NPs), physician assistants (PAs), and dentists. However, providers of color remain underrepresented in most clinical health care professions (AAMC, 2022; NCCPA, 2022; Smiley et al., 2023). The following section characterizes major segments of the U.S. clinical health care workforce.

Physicians

The United States has slightly more than one million active physicians, including approximately 500,000 primary care physicians and approximately 575,000 specialists (KFF, 2024). A significant shortage of primary care professionals exists, with particularly severe shortages in rural and underserved areas (Jabbarpour et al., 2024). The rapid decline in the percentage of physicians entering a primary care specialty suggests that the primary care workforce crisis (Jabbarpour et al., 2024; NASEM, 2021a).

Furthermore, there are no accountability levers in place for ensuring that Medicare graduate medical education funding is spent to ensure that adequate physicians are trained in areas shown to reduce health and health care inequities, such as public health, primary care, and mental health care (NASEM, 2021a). According to the Association of American Medical Colleges’ 2022 Physician Specialty Data Report, nearly half of U.S. physicians are 55+ years old, and 37 percent are female. Fewer than four in every 10 identified as a person of color, with the lowest rates among NHPI, American Indian and Alaska Native (AIAN), people of multiple races, Black, and Hispanic individuals at 0.1, 0.3, 1.3, 5.7, and 6.9 percent, respectively. Asian individuals had rates that were greater than any of the minoritized populations at 20.6 percent (AAMC, 2023a).

Nurses

Nurses make up the largest segment of the workforce,5 with more than 6 million active nurses (Smiley et al., 2023), and play a critical role in delivering and coordinating primary, specialty, acute, and long-term health care across the health care system (NASEM, 2021a, 2021b). There are approximately 5.2 million RNs, with 8.6 percent (369,972) as NPs and more than 950,000 LPNs/LVNs (Smiley et al., 2023). The average age for nurses is 46–47, and 88.5 percent are female. In 2022, White individuals made up the highest proportion of RNs at 80 percent, with 2 in 10 RNs identifying as a person of color. Asian and Black individuals were the next highest at 7.4 and 6.3 percent, respectively; 6.9 percent of RNs are of Hispanic or Latino ethnicity. As for LPNs/LVNs, White individuals made up about 66 percent, with about 34 percent identifying as racially and ethnically minoritized populations (Smiley et al., 2023).

Physician Assistants (PA’s)

PAs are trained and licensed to diagnose and treat a wide range of health conditions and have prescriptive authority. PAs practice both as primary care generalists and in nonprimary specialty care. The United States has approximately 141,000 PAs in the United States (BLS, 2023e). Approximately a quarter of certified PAs practice in primary care (NCCPA, 2023). According to the National Commission on Certification of Physician Assistants’ (NCCPA) 2022 Statistical Profile of Certified PAs, the mean age of U.S. PAs is 38 years, 70 percent are female, and only approximately 1 in 5 PAs identify as a racially and ethnically minoritized person.

___________________

5 See https://www.aacnnursing.org/news-data/fact-sheets/nursing-workforce-fact-sheet (accessed February 28, 2024).

Expanding the Definition of the Health Care Workforce

Equity-focused health care transformation requires an increased focus on health promotion, prevention, and restorative care services that can offset the adverse effects of structural health inequity drivers. Moving toward reforming the health care system, including by expanding traditional care locations and models for service delivery, will require reconsidering the traditional clinician-focused definition of the workforce. Clinicians are part of a larger care team that includes health care support professionals, such as nursing assistants, medical assistants, dental assistants, and phlebotomists. A large cadre of allied health professionals, including dietitians, medical technologists, occupational therapists, physical therapists, respiratory therapists, and speech language pathologists, also provides crucial services for expanding a comprehensive care focus on health promotion, prevention, and restorative care, beyond sick care.

In addition, mental, behavioral, and addiction health professionals are key workforce for addressing growing population-level health challenges associated with mental illness and substance use (Alegría et al., 2021). The behavioral and addiction workforce includes clinical and counseling psychologists; substance use, behavioral disorder, and mental health counselors; and social workers specializing in mental health, substance use, and health care (Torpey, 2023)

Pharmacists represent an increasingly important segment of the workforce, as scope-of-practice regulations in many jurisdictions increasingly allow for them to deliver select health care services and procedures, such as initiation, renewal, adjustment or substitution of prescriptions; order and interpretation of laboratory tests; and administration of injections and vaccines (Sachdev et al., 2020). Community-based home health aides and health education specialists are valuable contributors to the U.S. health care workforce. Consumer assisters or navigators have been deployed as part of the ACA to improve outreach to and enrollment of eligible racially and ethnically minoritized individuals and families in Medicare (ASPE, 2021, 2022), and research suggests that uptake of these services is particularly high among Latino/a people, for whom language and immigration-related barriers more frequently represent concerns (Garcia Mosqueira and Sommers, 2016).

Overlooking the important contributions of the nonclinical health workforce would represent a missed opportunity to achieve health care equity and optimal health for all. For this report, the committee uses an expanded definition of health care workforce that includes all clinical and nonclinical health care workers.

Community Health Workers (CHWs)

CHWs are frontline public health workers who are trusted members of the community they serve. This relationship enables CHWs to act as an intermediary between health and social services and the community to

facilitate access to services and improve the quality and cultural competence of service delivery. CHWs also build individual and community capacity by increasing health knowledge and self-sufficiency through a range of activities, such as outreach, community education, informal counseling, social support, and advocacy. CHWs reflect the values, culture, and experiences of the communities in which they work.

A growing body of evidence accumulated over 60 years shows that CHWs can play a critical role in addressing the nonmedical causes of health inequities, particularly SDOH, through a community-centered approach sensitive to local cultural and historical contexts (Cosgrove et al., 2014; Ignoffo et al., 2022; Kangovi et al., 2017; Vasan et al., 2021). For example, the CHW-delivered Individualized Management for Patient-Centered Targets (IMPaCT) intervention achieved higher patient-reported quality of care and fewer days spent in hospital among predominantly Black chronic disease patients residing in a neighborhood characterized by elevated poverty (Kangovi et al., 2018). During the pandemic, the Department of Homeland Security deemed them essential critical infrastructure workers because of their ability to address health inequities (National Academy for State Health Policy, 2020), and in 2021, the White House proposed employing 100,000 more CHWs as part of the American Rescue Plan Act.6

Reducing Practice Barriers

Despite the importance of optimally leveraging the health care workforce to improve access to services in underserved communities, important barriers to these efforts persist in many jurisdictions. In particular, scope-of-practice restrictions are worth examining. Some oppose removing regulatory restrictions across all states despite compelling evidence of the societal benefits of better leveraging the entire qualified workforce at the highest level of competencies, license, and education. Research suggests that overly restrictive scope-of-practice limitations worsen health care in underserved racially and ethnically minoritized communities. For example, a large body of research points to advantages for more equitable access to care associated with removing overly restrictive NP scope-of-practice limitations. NPs are more likely than physicians to provide primary care in medically underserved and health professional shortage areas and to Medicaid-insured patients (Grumbach et al., 2003). At the state level, scope-of-practice limitations for NPs were associated with reduced health care availability in communities experiencing health inequities (Poghosyan et al., 2017).

___________________

6 See https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/statements-releases/2022/09/30/fact-sheet-biden-harris-administration-announces-american-rescue-plans-historic-investments-in-community-health-workforce/ (accessed April 29, 2024).

Furthermore, in states with full practice authority, the NP workforce is on average more racially/ethnically representative of the overall population, compared to states with restrictions (Plemmons et al., 2023). Review articles also suggest that full state-level practice authority is associated with improvements across several measures of access to care, particularly for underserved populations (Kona et al., 2022; Patel et al., 2019a). In addition, researchers found that full practice authority is associated with higher supply of NPs in rural and primary care health professional shortage counties (Xue et al., 2018, 2019).

The discourse about scope-of-practice restrictions for various health professions is frequently influenced by “turf wars” between disciplines over authority, autonomy, and protected revenue streams (Chen et al., 2023; Chesney and Duderstadt, 2017), alongside substantive concerns regarding care access, quality, patient safety, and cost. For advancing health equity, it is therefore necessary to center the discussion on evidence for which workforce segments are most effectively serving populations affected by harmful SDOH and health inequities and ensure they are able to practice at the highest level of their education, training, and license.

HCPs frequently cite lack of autonomy or access to professional opportunities as a reason to resign (Schlak et al., 2022). This includes feelings of lack of empowerment in decision making, career advancement opportunities, continuing education, and overall inability to innovate (Marufu et al., 2021). Therefore, as part of efforts to remove scope-of-practice restrictions, other dimensions of HCP autonomy warrant consideration, including redesigning the workflow to enable more frequent collaboration with colleagues both within and across licenses and disciplines, providing flexible working hours, competitive salaries, and benefits packages, and offering opportunities for ongoing professional development and leadership to provide input to and directly shape their work environments, such as through involvement in governing boards.

Diversifying the Health Care Workforce

Racially and ethnically minoritized populations remain significantly underrepresented among practitioners and trainees in a wide range of health care professions (Salsberg et al., 2021), which research has identified as a contributor to health care inequities (Cole et al., 2023; Pittman et al., 2021; Salsberg et al., 2021). Since Unequal Treatment called for diversifying the workforce, research has further strengthened evidence linking increased workforce diversity with reductions in key drivers of inequity. For example, HCP shortages frequently contribute to unequal access to health care for underserved communities (Tzenios, 2019). Research also suggests

that HCPs from racially and ethnically minoritized communities are most likely to practice in underserved areas (Salsberg et al., 2021; Xierali and Nivet, 2018).

With respect to trends in the workforce, 2003–2019 saw no significant improvements in race-based differences in graduates of MD, DO, DDS/DMD, or PharmD programs. For MD programs, the representation quotient (which is relative to the proportion of that subgroup comprising the U.S. census population) for Black/African American, Hispanic or Latino, AIAN, and NHPI was less than 1, signifying underrepresentation (Majerczyk et al., 2023). The proportion of medical school graduates who were Black was 6.2 percent in 2019 and 6.7 percent in 2023; these data are not adjusted for changes in the U.S. population, and statistical testing was not performed (AAMC, 2023b). Also, data from the 2020 National Nursing Workforce Survey indicate that Black individuals were 6.7 percent of the workforce in 2020 (compared to 6.2 percent in 2017) but decreased to 6.3 percent in 2022, and the proportion of Hispanic individuals increased by 1.6 percent from 2017 to 2022. AIAN and NHPI populations made up the lowest percentage of the nursing workforce at 0.4 percent each in 2022. Interventions to increase diversity in the workforce continue to be critical (Smiley et al., 2023).

Beyond the paucity of health care providers in underserved communities, the unequal use of health services among racially and ethnically minoritized communities has also been linked to a low trustworthiness of the health care system resulting from historical patterns and lived experiences of bias, discrimination, and culturally misaligned health service delivery (Jaiswal and Halkitis, 2019; Newman, 2022). Patients with a racially and ethnically concordant HCP have reported lower levels of mistrust, higher levels of satisfaction, and better communication with their provider (Shen et al., 2018). Similarly, studies have found improved care outcomes for patients receiving care from a racially and ethnically concordant HCP (see Box 5-1). International medical graduates also help to diversity the physician workforce and provide high-quality care, but data are lacking on potential differences in outcomes in their minoritized patients (Norcini et al., 2008).

Recruiting, training, and retaining a more diverse cadre of HCPs who are representative of and familiar with the communities they serve is a direct approach to strengthen a sense of association and facilitate perspective-taking between racially and ethnically minoritized patients and their HCPs. However, admission to health professional education programs represents a primary barrier to a career as an HCP for underrepresented, minoritized (URM) students. A 2024 systematic review examined the admission barriers and facilitators for URM students, with a particular emphasis on Black students, in medical education (Rattani et al., 2024). The researchers

BOX 5-1

Racially Concordant Care

Racially and ethnically minoritized patients who receive care from racially and ethnically concordant health care providers generally have better health outcomes. For example, in a study that randomized 1,300 Black men to a racially concordant male physician (versus one who was not), patients were more likely to select preventive services, particularly invasive services, after consultation with Black male providers (Alsan et al., 2019). The researchers estimated that diagnosis and control of these cardiovascular risk factors could translate into a 19 percent reduction in the Black–White male cardiovascular mortality gap. These results align with a 2022 study of the US Military Health System, which found that an increase in the proportion of Black physicians led to a 15 percent relative decline in mortality among Black patients with cardiovascular and other chronic diseases (Frakes and Gruber, 2022). Studies have also demonstrated a reduction in racial inequities in newborn in hospital mortality. For example, researchers examined 1.8 million hospital births in Florida, 1992–2015, with the unadjusted Black newborn mortality three times higher than that of White newborns. Although the rate for White newborns was the same regardless of physician race (White versus Black), the Black–White mortality gap was decreased by 58 percent when Black newborns were cared for by Black physicians (Greenwood et al., 2020). Snyder and colleagues (2023) were the first to examine population-level outcomes related to physician racial diversity, measuring the associations between the representation of Black PCPs and the mortality and survival rates within counties and between counties. A 10 percent increase in Black representation was associated with a 30.6-day increase in life expectancy for Black individuals, a reduction in all-cause mortality among Black persons by 12.7 deaths per 100,000, and a 1.2 percent reduction in the Black–White inequity in all-cause mortality.

Evidence is also emerging for benefits of racially/ethnically concordant patient–provider relationships for non-Black minoritized populations. For example, Ma et al. (2019) found that Latino/a, Asian, and Black patients all had a higher likelihood of seeking preventive care services if they had a racially/ethnically concordant HCP. Latino/a and Asian patients also had a greater likelihood of seeking care for new health problems and staying engaged in care for ongoing health problems. Jetty et al. (2022) found lower health care expenditures for Latino/a, Asian, and Black patients with a racially/ethnically concordant HCP, indicating better overall health outcomes.

Despite evidence about the effectiveness of racial/ethnic patient–provider concordance in improving the health of minoritized patients, creating a diverse workforce has remained a challenge facilitated by structural inequities, such as racial inequities in the quality of education and parental employment and income.

identified several barriers, including financial and socioeconomic burdens, lack of access to preparatory materials and academic enrichment programs, lack of exposure to the medical field, inadequate mentoring and advising experiences, systemic and interpersonal racism, and limited support systems (Rattani et al., 2024).

To address this underrepresentation among AIAN populations in medical education, the Cherokee Nation, together with Oklahoma State University, launched the first tribally affiliated medical school in 2020 to train physicians in culturally directed medical care in rural and tribal communities.7 Although most medical schools teach about barriers that can make it difficult for rural or Indigenous patients to get care and improve their health, these students experience these barriers firsthand by studying and working on the Cherokee Nation and doing rotations in facilities run by the Indian Health Service.

THE HEALTH CARE ENVIRONMENT

Institutional Racism

Institutional racism in health is defined as “a systematic set of patterns, procedures, practices, and policies that operate within institutions so as to consistently penalize, disadvantage, and exploit individuals who are members of non-White groups” and adversely affects quality of care, patient experiences, the organizational climate, as well as staff satisfaction and morale (Griffith et al., 2007). It has been conceptualized as mediating aspects of the harmful impact of structural racism on health inequities (Adkins-Jackson et al., 2021) and operates with a degree of independence from the intent and attitudes of organizational leadership and staff (Elias and Paradies, 2021).

Factors external to individual health care organizations, such as laws, rules, guidelines, and customs shaped by the government, regulatory agencies, health care payers, and in health professional education, are reflected in how health care institutions deliver care (Adkins-Jackson et al., 2021; Elias and Paradies, 2021; Griffith et al., 2007). Within individual institutions, policies, practices, and norms on how resources (including provider time) are allocated, information is communicated, and care decisions are made can result in systematically inequitable care and experiences for patients. Importantly, the harmful impacts of institutionally racist policies, practices, and norms are not necessarily restricted to departments engaged in direct patient care but also aspects of organizational administration (Griffith et al., 2007). Nevertheless, some aspects of institutionally racist policies, practices, and norms can shape direct patient–provider clinical interactions.

___________________

7 See https://medicine.okstate.edu/cherokee/ (accessed March 29, 2024).

Research has identified care practices and norms that are accepted at health care institutions but perpetuate racial and ethnic inequities in care quality and experiences. Lim and colleagues examined categories of procedural discrimination in health institutions experienced by racially and ethnically minoritized patients (2021). The researchers documented, for example, care plans frequently being altered without consultation of patients, care-related documents’ being changed by the institution without offering explanation to patients, and institutional practices offering little responsiveness to non-Western cultural norms and customs, including after requests for accommodation (Lim et al., 2021). Additionally, health care institutions play a role in maintaining pre-existing health inequities by not recognizing and counteracting structural disadvantages and injustices impacting their patients, staff, and partners at all levels, thereby perpetuating the status quo (Elias and Paradies, 2021). For example, eliminating institutional and structural racism in health care also necessitates elimination of inequities in hiring, evaluation, and promotion of staff, including equal starting pay and raises, and increasing the diversity and representativeness in the organizational leadership ranks (Dent et al, 2021; Griffith et al., 2007).

Biases In Clinical Decision Making

Sound clinical decision making is one of the foundations of good medical care. It requires clinicians to collect data from and about individual patients and apply medical knowledge and judgment to arrive at the right therapeutic decisions. Clinicians, like most people, may have personal experiences, biases, or stereotypes of minoritized populations that may negatively influence their perceptions and clinical decision making, leading to inequitable care decisions (Hall et al., 2015; Maina et al., 2018). Some of these beliefs are conscious and acknowledged; others are unconscious. Although less evidence has examined the impact of conscious (explicit) biases in health care, evidence for the impact of unconscious (implicit) biases is growing.

Implicit Bias Within the Health Care Environment

Patients can receive inequitable care as a result of racism in the health care environment. Nearly half of health care workers say they have witnessed racism against patients (Fernandez et al., 2024). Several studies document that discrimination is common across minoritized populations (Bleich et al., 2019; Findling et al., 2019a, 2019b; McMurtry et al., 2019). About one in five Hispanic or Latino/a and Native American individuals have experienced discrimination in clinical care, and about one in six have

forgone health care services for themselves or a family member because they anticipated discrimination (Findling et al., 2019a, 2019b). Similarly, 13 percent of Asian individuals have experienced discrimination in health care (McMurtry et al., 2019). Among Black individuals, approximately one-third reported experiencing discrimination, with nearly a quarter having forgone health care services for themselves or a family member because they anticipated discrimination (Bleich et al., 2019).

Research has identified the negative impact of implicit biases on health care decision making in a wide variety of clinical situations, from treatment of pain to care for acute and chronic diseases such as COVID-19, heart disease, diabetes, HIV, and across the spectrum of patient ages (Burton et al., 2023; FitzGerald and Hurst, 2017; Maina et al., 2018; Simons, 2020). Research has demonstrated that HCPs can hold the same types of negative biases against racially and ethnically minoritized groups that non–health care providers do, and these biases can affect medical decision making and treatment (Hall et al., 2015; Maina et al., 2018).

The main primary strategy to address implicit bias in health care delivery has been unconscious bias trainings (UBTs), typically implemented in medical school and health care settings (Gino and Coffman, 2021). UBTs aim to enhance awareness of implicit bias, reduce both implicit and explicit bias, and change behavior. However, most UBTs focus on raising awareness of bias in a check-the-box type seminar and do not show long lasting effect on reducing implicit bias (NASEM, 2024). Multisession implicit bias trainings have shown to be effective (Devine et al., 2012; Ruben and Saks, 2020). Priority areas for further developing and improving implicit bias interventions include specifically tailoring programs to clinical specialties and populations of focus; identifying effective curricular elements, learning objectives, content areas, and frequency/length of training; and improving trainers’ qualifications (Cooper et al., 2022).

Another strategy to eliminate bias is clinical algorithms, which are intended to assist clinicians with medical decision making by helping them objectively choose the best pathways for diagnosis and treatment. However, they are often subject to the same biases, stereotypes, and limitations of the humans who develop them, depending on the data used to train them. A growing body of evidence shows that poorly designed algorithms can contribute to health inequities (Cary Jr. et al., 2023; Chin et al., 2023; Nazer et al., 2023; Obermeyer et al., 2019; Rajkomar et al., 2018). Those that use race as a proxy for biological differences that are not race based risk distorting medical decision making in ways that are not scientifically justifiable and are harmful to minoritized populations. Algorithms based on data that are biased or insufficient to represent the racial and ethnic diversity of the population also risk inappropriate medical decision making. These drawbacks raise the risk that they will exacerbate rather than improve racial and ethnic

health inequities. Efforts in some clinical guidelines (e.g., renal transplantation) have purposefully incorporated equity of historically marginalized groups (e.g., racially and ethnically minoritized populations, rural residents), with evidence of impact already seen in epidemiological studies (Ku et al., 2021). Reviewing algorithms for fairness needs to be one of the principal tests before they are deployed in clinical settings (Rajkomar et al., 2018).

Promising Interventions

Antibias interventions can result in short-term increases in awareness about provider bias and increases in provider engagement regarding establishing egalitarian goals for care delivery, but few result in behavior changes that can address interpersonal and institutional racism (FitzGerald and Hurst, 2017; Vela et al., 2022). In addition, few have studied long-term impact. For example, in a cluster RCT of primary care clinicians caring for Black patients with diabetes, cultural competency training and quality performance reports did not improve control of glucose, blood pressure, or cholesterol (Sequist et al., 2010). A promising intervention from 2012 aimed to reduce implicit bias through 12 weeks of habit-breaking, antibias interventions geared toward psychology students (Devine et al., 2012). It consisted of several components aimed at increasing awareness of implicit biases, providing information about the consequences of such biases, and teaching strategies to reduce and manage biases. These techniques included counterstereotypic imaging, individuation (seeing people as individuals rather than representatives of a group), perspective-taking (empathizing with the experiences of others) and increasing opportunities for contact with members of other races. Over the intervention, participants expressed increase levels of awareness of bias and concern about bias. Other promising bias management interventions include a program based on values affirmation, which improves communication with patients (Havranek et al., 2012), and a common identity intervention that led to greater improvements in patient trust and adherence than a control intervention (Penner et al., 2013). Other novel programs such as simulation-based learning have been developed but not yet evaluated (Tjia et al., 2023).

Two interventions, geared toward HCPs, implemented promising strategies for sustained changes in beliefs and behaviors. Both used the Transformative Learning Theory (TLT), transforming the individuals’ existing paradigm by disrupting assumptions and engaging in critical reflection and dialogue to interpret the disruptions (Mezirow, 1997). An intervention examined the effects of implicit bias training in a residency program. It consisted of two 60–90-minute workshops for family medicine residents and faculty. The first addressed race, racism, White centrality and normativity in

society, and implicit bias. The second offered practical, applied recommendations for how to address implicit bias; it facilitated a group discussion by a national expert on the barriers to addressing bias (e.g., the myth of meritocracy, aversive racism) and then provided tangible tools to overcome the obstacles (e.g., find allies, take a health equity time-out). In focus groups 4 months after the intervention, participants reported an increased awareness of biases and a sustained commitment to address racial bias, challenge their clinical decision making, and engage leadership in dialogue about bias (Sherman et al., 2019).

Another intervention incorporated TLT into a program of “implicit bias recognition and management” to promote conscious awareness of biases and foster behavioral changes. This intervention consisted of nine 90-minute sessions for preclinical medical students enrolled in an elective course. The first six sessions focused on students’ direct participation in interpersonal encounters with patients and peers; the last three focused on students’ responses to perceived bias in the learning environment (e.g., during a structured role-play, “identify and implement one strategy to debrief with supervisors or peers in clinical encounters when implicit bias may have been playing a role”). The evaluation included direct observation of skills during role-plays and qualitative analysis of student focus groups. The authors noted that direct engagement was enhanced through the program, the instruction was empowering, and addressing bias in clinical settings can successfully be done, even by health professional trainees (Sukhera et al., 2020).

These participatory interventions suggest that teaching about how both individual biases and institutional inequities contribute to structural racism and using skills-based methods about managing implicit biases in health care settings show promise as a strategy to change clinician behaviors sustainably. Interventions to mitigate interpersonal racism (e.g., bias) have generally been ineffective at changing attitudes or behaviors long term, and cultural competency training had been proven ineffective at improving health care delivery or outcomes for racially and ethnically minoritized populations. However, there appears to be promising training based on TLT. It involves interactive, in-depth discussions that teach providers about racism/structural inequities and provide them with tools to address it within their health care organizations.

Patient–Clinician Relationships in Health Care

Patient–clinician relationships are important to optimizing the health care environment and the care experience for patients. Strong and positive patient–clinician relationships are characterized by ongoing care provided by the same clinician or care team, confidence in HCPs prioritizing their

patient’s best interest, mutual trust, and SDM (Montgomery et al., 2020). SDM, in particular, represents a cornerstone for building strong and positive patient–clinician relationships. Evidence suggests that when patients and clinicians share equally in the decision-making process, outcomes improve.

Promising Interventions

Several interventions have shown promise in improving clinicians’ SDM skills and the delivery of culturally tailored services. Peek and colleagues evaluated an intervention of SDM skills training and culturally tailored diabetes education among urban African Americans (Peek et al., 2012). Significant improvements were noted in patients’ decision–medicine confidence, behaviors in information-sharing and decision making, and report of physician behaviors in SDM. In addition, patients increased the frequency of their diabetes self-management behaviors, and diabetes control improved at 3 months.

Another study evaluated the impact of a patient-centered hypertension control intervention by providing physicians with communication training and patients with coaching by CHWs. Compared to the control group, the trained group of physicians had more positive communication scores. After 12 months, the intervention group reported significantly better physician participatory decision making and patient involvement in care (Cooper et al., 2011). Alegría and colleagues evaluated the DECIDE intervention, which seeks to improve patient decision making and patient–provider interactions, in an RCT with mostly racially and ethnically minoritized adults (Alegría et al, 2018). It was delivered by care managers and significantly increased patient activation and self-management in behavioral health care.

Raue and colleagues (2019) conducted an RCT to evaluate the effectiveness of training clinicians to use SDM for elderly minoritized primary care patients with depression. It involved training nurses to discuss depressive symptoms, experiences, and concerns with the participants to determine appropriate treatment plans. Participants were also provided psychoeducation and assistance in scheduling appointments and overcoming logistical barriers to care (e.g., lack of transportation). SDM nearly doubled the rates of participants initiating mental health treatment. However, it did not affect antidepressant initiation or adherence, and both SDM and usual care participants had clinically significant reductions in depression severity. Social service or case management needs were not addressed, which, the authors speculate, may have related to the null findings for medication adherence and depression. These findings highlight the importance of holistic care and addressing social service needs to improve the health care and health outcomes of minoritized populations (Raue et al., 2019).

INDIVIDUAL CARE-SEEKING BEHAVIOR AND MEDICAL MISTRUST

As discussed earlier in this report, research has shown a range of barriers precluding individuals from accessing health care, including partial or complete lack of insurance coverage and associated costs, lack of access to transportation, and geographic unavailability of services, particularly in rural areas.8 Even when are accessible, individuals make different decisions about whether and the degree to which they seek and engage with care. Factors related to decisions about care-seeking behavior include cultural norms, particularly related to gender (Weber et al., 2019); experiences with discrimination (Ben et al., 2017); and the degree to which individuals perceive HCPs and organizations to be trustworthy (LaVeist et al., 2009).

Medical mistrust is an important SDOH shaping engagement across the health service continuum (Jaiswal and Halkitis, 2019). It is rooted in historical hierarchies and relationships between systemic structures, institutions, and communities and individuals associated with lived experiences of discrimination, bias, and harm among racially and ethnically minoritized communities and other marginalized groups, including LGBTQ individuals and people who use drugs (Jaiswal and Halkitis, 2019; Newman, 2022). Studies suggest that it is more common among racially and ethnically minoritized individuals (Benkert et al., 2019; Newman, 2022). Interest is increasing in developing evidence-based interventions to address medical mistrust in racially and ethnically minoritized communities, including at the federal level. For example, CDC launched Project Confianza, a large-scale multistudy national initiative designed to identify the root causes of medical mistrust among Latino men who have sex with men and opportunities to implement interventions that can make HIV-related services trusted and acceptable.9

Addressing Medical Mistrust

A large body of evidence documents medical mistrust and distrust among minoritized patients as a barrier to health care use, treatment adherence, patient–clinician relationships, and other factors that impact health (Bazargan and Assari, 2021; El-Krab et al., 2023; Hall and Heath, 2021). However, evidence from interventions that effectively address

___________________

8 See https://health.gov/healthypeople/priority-areas/social-determinants-health (accessed March 29, 2024).

9 See https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2024/02/27/2024-03884/proposed-data-collection-submitted-for-public-comment-and-recommendations. (accessed March 29, 2024).

medical mistrust or increase the trustworthiness of health care institutions is limited. Engaging community members in a variety of ways, from CHWs to CPBR, has been the one evidence-based approach known to increase trust among racially minoritized and other patient populations. Socially concordant providers (e.g., by race, gender) have also been shown to increase trust. However, additional strategies, and more granularity, are needed. The North Carolina Survivors Union was an example of a successful collaboration between people who use drugs (PWUD) and academic research institutions (Salazar et al., 2021). Because PWUD often mistrust the medical community, trusted community-led harm reduction organizations can serve as bridge builders to facilitate research and community-based health care. Community involvement in the research process also served to diversify the employment opportunities for PWUD and implement principles of equity, collaboration, and trust-building in direct service provision.

Smirnoff and colleagues (2018) created a conceptual model, based on qualitative research, that provides insight into how factors impacting trust are interrelated and can provide a foundation for interventions and implementation science. The research team identified four specific domains of trust/mistrust, each of which was associated with different demographic variables: general trustworthiness (older age, not living with a disability), perceptions of discrimination (African American, Latino, Spanish language preference), perceptions of deception (prior research experience, African American), and perceptions of exploitation (less education). Because medical mistrust and stigma are barriers to accessing sexual health information and services for sexual and gender minorities, particularly men who have sex with men, virtual avatar technology has emerged as a way for people to anonymously practice skill building, foster relationships, and seek information. In a review of the literature about this technology and HIV prevention and treatment (Orta Portillo, 2023), it was found to create an environment in which participants felt comfortable discussing and addressing their sexual behaviors. It helped build rapport with populations put at high risk and provided assistance in searching for information, preventive services, or treatment for HIV or other sexually transmitted infections. Identifying more strategies to address medical mistrust among marginalized populations and increase the trustworthiness of the health care institutions that serve them will be critical to advancing health equity.

HEALTH LITERACY

Personal health literacy is defined as “the degree to which individuals have the ability to find, understand, and use information and services to inform health-related decisions and actions for themselves

and others.”10 Increased health literacy positively increases health and health outcome been shown to improved health outcomes (Coughlin et al., 2020; Logan et al., 2015; Miller, 2016). However, lower levels of health literacy tend to cluster with other social inequities, including with income, educational attainment, minoritized racial and ethnic group membership, and exposure to harmful SDOH11 (Fleary and Ettienne, 2019). Interventions designed to improve health literacy among individuals frequently include a strong basis in theories of behavior, cultural and contextual tailoring, personalization to individual needs, interactive communication methods, and goal-setting.

Health literacy is not an attribute of the individual alone and should be contextualized in relation to available health information (López et al., 2022). The ability to understand and appropriately act on health information depends on personal health literacy and how health care and public health agencies, organizations, and practitioners communicate health information (López et al., 2022). Healthy People 2030 defines organizational health literacy as “the degree to which organizations equitably enable individuals to find, understand, and use information and services to inform health-related decisions and actions for themselves and others.”12 Several principles and best practices for health literate organizations and health systems have been identified in the literature. Key strategies for improving organizational health literacy include executive leadership buy-in and organizational culture alignment, proactive workforce training and development, conceptualization of organizational health literacy as preventive and whole-person care services, inclusion of organizational health literacy in accreditation criteria and policy/regulatory incentivization, and measurement of and accountability for specific health literacy metrics (López et al., 2022; Palumbo, 2021).

Promising Interventions

Community-based participatory research approaches were also used to develop Insuring Good Health, a multimedia intervention that addresses health insurance literacy and links individuals with insurance enrollment assistance (Patel et al., 2019b). It was conducted in collaboration with

___________________

10 See https://health.gov/healthypeople/priority-areas/health-literacy-healthy-people-2030 (accessed March 29, 2024).

11 The National Academies has a Round Table on Health Literacy that serves as a venue for experts to identify high-priority issues to support developing, implementing, and sharing evidence-based practices and policies. See https://www.nationalacademies.org/our-work/roundtable-on-health-literacy.

12 See https://health.gov/healthypeople/priority-areas/health-literacy-healthy-people-2030 (accessed March 29, 2024).

Detroit organizations involved in ACA-related outreach or providing direct care or services to target populations, including African American, Arab American or Middle Eastern, and Hispanic/Latino/a urban populations. The intervention included videos on navigating health insurance and care to provide information on the issues the target populations commonly face. At the 9-month follow-up, the intervention group expressed a stronger belief in preventive care and more intention to seek health insurance navigation assistance than the control group. Hispanic/Latino/a participants reaped the most benefits in gains in knowledge of eligibility and confidence in navigating health insurance, which indicates the importance of culturally sensitive outreach for the intervention’s success.

HEALTH INFORMATION TECHNOLOGY (HIT)

The HIT landscape has been dramatically transformed since the 2003 report. Among the many key changes has been the widespread adoption of HIT and electronic health record (EHR) systems, which have fundamentally changed access to patient data, information, and knowledge. This shift was a direct result of legislation, the Health Information Technology for Economic and Clinical Health provision in the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009.13

The new availability of EHRs provides not only timely access to comprehensive information about an individual at the point of care but also aggregate data on communities and populations that can be analyzed to assess the quality and outcomes of health care. Such analyses have been pivotal in identifying racial and ethnic inequities in outcomes and disparities based on geography and insurance coverage, among other SDOH (Rasmussen et al., 2023). Differences in medical decision making may reflect implicit racial and ethnic biases (Dehon et al., 2017; Vela et al., 2022) and differing outcomes of chronic disease management may reflect differences in treatment decision equity. Race-based clinical risk scores and physiology-performance estimates (e.g., estimated glomerular filtration rate [eGFR]) may bias treatment decisions and referral patterns that disadvantage patients’ access to care (Vyas et al., 2020).

EHRs can also be a vehicle for mitigating health care inequities—if these considerations are built into their design and use. For example, by learning from population-level observational EHR data, precision cohorts can be constructed to show what treatment plans have generated the best outcomes for a cohort of people similar to a specific patient instead of

___________________

13 See https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/BILLS-111hr1enr/pdf/BILLS-111hr1enr.pdf (accessed March 30, 2024).

relying on studies conducted on homogeneous cohorts that do not match the individual patient (Tang et al., 2020). One size does not fit all patients. In addition, integrating small-area deprivation indexes into the EHR could enable providers and practices to identify patients’ potential needs based on their geographic location (Bazemore et al., 2016) and may be more feasible than capturing data on individual-level SDOH for all patients in a health care system.

Telemedicine and Telehealth

HIT and networked access to information offer new opportunities for delivering care and could narrow inequities in access to care. The use of telemedicine during the COVID-19 pandemic showed how effective virtual care could be as a modality both for routine outpatient care and to monitor the care of COVID-19 patients isolated at home. This approach can help overcome access barriers, such as geographic isolation, limited transportation options, and work-loss consequences, which disproportionately affect low-income and racially minoritized groups (Chauhan et al., 2020). Research has also shown that interventions for management of chronic conditions using mobile health platforms can improve outcomes (Doshi et al., 2017). The temporary policy waivers in state-based licensing and payment restrictions that were authorized during the COVID-19 emergency has highlighted the need for permanent policy and payment reforms to sustain the benefits of telehealth.

Translating this opportunity into health benefits for marginalized populations will also require addressing technology-access obstacles, such as unequal broadband access, lack of technology availability, and technology literacy challenges—collectively known as the “digital divide” (López et al., 2011). Furthermore, many resources and applications are accessible only in English. More than direct-translation services, culturally appropriate native-language communication needs to be available. For example, patients most at risk for COVID-19 infection used telemedicine the least because of racial and ethnic, language, and economic barriers (Qian et al., 2022). Patients who used telemedicine during the pandemic were more likely to choose telephone visits versus video visits if they had less education, were older, were unemployed, or had a disability (Aziz et al., 2021). Regardless of the efficacy of HIT demonstrated in a clinical trial, effective implementation in settings that matter is essential to reach the “last mile” (Anaya et al., 2021; Rodriguez et al., 2023; Williamson et al., 2024).

An example program that explicitly addressed technology access barriers was implemented in the Veterans Health Administration. The Digital Divide Consult worked to ensure that veterans who wish to participate in