Ending Unequal Treatment: Strategies to Achieve Equitable Health Care and Optimal Health for All (2024)

Chapter: 1 Unequal Treatment: 20 Years After

1

Unequal Treatment: 20 Years After

Twenty years after the Institute of Medicine’s1 2003 report entitled Unequal Treatment: Confronting Racial Bias and Ethnic Disparities in Health Care, unequal treatment persists, and much work remains to advance health care equity in the United States. Thus, the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality and the National Institutes of Health (NIH) asked the National Academies of Science, Engineering, and Medicine (National Academies) to create a consensus report that updates Unequal Treatment. This consensus committee was charged with highlighting current drivers of racial and ethnic health care disparities, providing insight into successful and unsuccessful interventions, identifying gaps in the evidence base, proposing strategies to close those gaps, considering ways to scale and spread effective interventions to reduce racial and ethnic disparities in health care, and making recommendations to advance health equity.

Unequal Treatment was mandated by Congress as a follow-up to the 1985 Report on Black and Minority Health, requested by the Secretary of Health and Human Services (HHS). The foundational 2003 report assessed the extent of racial and ethnic differences in health care that are not otherwise attributable to known factors, such as and lack of health insurance and access to care, and explored potential sources of racial and ethnic disparities in health care.

___________________

1 As of March 2016, the Health and Medicine Division of the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine (NASEM) continues the consensus studies and convening activities previously carried out by the Institute of Medicine (IOM). The IOM name is used to refer to reports issued prior to July 2015.

Based on an extensive and systematic review of the evidence, the 2003 committee concluded that racial and ethnic disparities were widespread and played a central role in certain racially and ethnically minoritized populations receiving inferior care, which was associated with poor health outcomes. The 2003 report also found that a critically important contributing factor was racial and ethnic stereotyping and prejudice by clinicians. Even when unconscious, consistently caused clinicians to misdiagnose and under-treat minoritized individuals. The 2003 report made a series of recommendations for eliminating health and health care disparities (Box 1-1).

BOX 1-1

Summary of Recommendations from the 2003 Unequal Treatment Report

General

- Recommendation 2-1: Increase awareness of racial and ethnic disparities in health care among the general public and key stakeholders.

- Recommendation 2-2: Increase health care providers’ awareness of disparities.

Legal, Regulatory, and Policy Interventions

- Recommendation 5-1: Avoid fragmentation of health plans along socioeconomic lines.

- Recommendation 5-2: Strengthen the stability of patient–provider relationships in publicly funded health plans.

- Recommendation 5-3: Increase the proportion of underrepresented U.S. racial and ethnic minorities among health professionals.

- Recommendation 5-4: Apply the same managed care protections to publicly funded health maintenance organization (HMO) enrollees that apply to private HMO enrollees.

- Recommendation 5-5: Provide greater resources to the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services’ Office of Civil Rights to enforce civil rights laws.

Health Systems Interventions

- Recommendation 5-6: Promote the consistency and equity of care through the use of evidence-based guidelines.

- Recommendation 5-7: Structure payment systems to ensure an adequate supply of services to minority patients, and limit provider incentives that may promote disparities.

- Recommendation 5-8: Enhance patient–provider communication and trust by providing financial incentives for practices that reduce barriers and encourage evidence-based practice.

- Recommendation 5-9: Support the use of interpretation services where community need exists.

- Recommendation 5-10: Support the use of community health workers.

- Recommendation 5-11: Implement multidisciplinary treatment and preventive care teams.

Patient Education and Empowerment

- Recommendation 5-12: Implement patient education programs to increase patients’ knowledge of how to best access care and participate in treatment decisions.

Cross-Cultural Education in the Health Professions

- Recommendation 6-1: Integrate cross-cultural education into the training of all current and future health professionals.

Data Collection and Monitoring

- Recommendation 7-1: Collect and report data on health care access and utilization by patients’ race, ethnicity, socioeconomic status, and where possible, primary language.

- Recommendation 7-2: Include measures of racial and ethnic disparities in performance measurement.

- Recommendation 7-3: Monitor progress toward the elimination of health care disparities.

- Recommendation 7-4: Report racial and ethnic data by Office of Management and Budget (OMB) categories but use subpopulation groups where possible.

Research Needs

- Recommendation 8-1: Conduct further research to identify sources of racial and ethnic disparities and assess promising intervention strategies.

- Recommendation 8-2: Conduct research on ethical issues and other barriers to eliminating disparities.

SOURCE: IOM, 2003.

IMPACT OF THE 2003 UNEQUAL TREATMENT REPORT

The most significant legacy of the 2003 report is framing the problem of unequal treatment and associated calls for action to address it. That report catalyzed research to better understand the root causes of health care inequities and their effects. Equally important, it was widely read by diverse audiences and established common ground for discussions. Front-page stories and editorials about it appeared in the national and local press. Many health care professional organizations and health care systems began conducting implicit bias training and raising awareness among their workforces that improvements were imperative.

The 2003 report also stimulated considerable research documenting both the persistent patterns and understanding of the drivers of health care inequities; it also triggered efforts to increase the diversity of the health care workforce (Mateo et al., 2024). Thus, from this committee’s assessment of the recommendations from the 2003 report, those that have seen the most progress have been the recommendations on awareness creation for the general population (Table 1-1, recommendation 2-1) and for health care providers (Table 1-1, recommendation 2-2), but these are still far from reaching their full potential. Furthermore, evidence on whether implicit bias training has led to meaningful behavior change is mixed. Table 1-1 summarizes the committee’s assessment on the progress toward implementing the 2003 report’s recommendations. Detailed discussions on implementation status for some specific recommendations are included in relevant chapters.

To move the nation closer to the goal of an equitable health care system to achieve optimal health outcomes for all people, the National Academies ad hoc committees have authored multiple additional consensus reports since 2003. Several themes have emerged in discussions on advancing health care equity (see Appendix B for examples of the reports). Prominent among these themes is the importance of the following:

- Increasing awareness and understanding of health care inequities among actors in the health care ecosystem;

- Standardizing and providing guidance on the collection of data on race, ethnicity, socioeconomic status, acculturation, and language use in all health and health care data systems;

- Increasing diversity in and strengthening the health care workforce through accessible professional education and incorporating culturally competent education and training;

- Adopting alternative payment models to aid payment reform;

- Implementing approaches to address factors that influence health;

- Using data and data systems to their full potential to advance health equity research;

| Recommendation | Status of Implementation | Relevant Chapter |

|---|---|---|

| General | ||

| 2-1 | Less than half of the general population recognize the influence of social and physical factors and their differential impact on health. | 2 |

| 2-2 | Training on implicit bias has been broadly adopted, but the evidence that this leads to meaningful behavior changes is limited. | 5 |

| Legal, Regulatory, and Policy Interventions | ||

| 5-1 | Insurance enrollment and affordability barriers continue to disproportionately affect minoritized groups. | 4 |

| 5-2 | There are interventions aimed at strengthening patient–clinician relationships in the health care system, but their effectiveness in publicly funded health plans is unknown. | 5 |

| 5-3 | Available data shows that the existing health care workforce is not representative of the diverse U.S. population it serves. | 5 |

| 5-4 | Different payment policies have shown mixed results in reducing racial and ethnic health care inequities. | 4 |

| 5-5 | The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Office for Civil Rights remains underfunded. This has limited its efforts to enforce civil rights statutes and address the complaints it receives from individuals. | 4 |

| Health Systems Interventions | ||

| 5-6 | Some clinical practice guidelines used to provide consistent standards for health professionals are subject to the expertise of convened panels that often lack diversity and representation of racial and ethnically minoritized health professionals. | 5 and 8 |

| 5-7 | The Affordable Care Act has helped to expand primary health care in medically underserved communities, created new public health financing streams, and established new types of teaching programs aimed at expanding access to primary care in underserved communities. Significant shortages and access barriers remain. | 4 |

| 5-8 | Interventions aimed at enhancing patient–clinician communication and trust exist, but financial incentives for practices that reduce barriers and encourage evidence-based practice are lacking. | 5 |

| 5-9 | Emerging health care delivery models that include community health workers (CHWs) who deliver socioculturally tailored care have been effective in many settings and for multiple conditions. However, barriers to widespread and sustainable CHW programs persist. | 5 |

| Recommendation | Status of Implementation | Relevant Chapter |

|---|---|---|

| 5-10 | Use of CHWs has increased, but they are not well funded or integrated into the U.S. health care system. | 5 and 7 |

| 5-11 | Emerging health care delivery models include teams of clinicians and non-clinicians to coordinate care, address health-related social needs, provide health education, and deliver socio-culturally tailored care. These models have not been widely implemented and have no long-term sustainability plans. | 5 and 6 |

| Patient Education and Empowerment | ||

| 5-12 | There are interventions aimed at delivering culturally tailored education to patients to increase their knowledge and participation in shared decision making. These have not been widely implemented. | 5 |

| Cross-Cultural Education in the Health Professions | ||

| 6-1 | The design and implementation of anti-racism and cross-cultural education work has increased in some professional training programs. It is not standardized and has been scaled back or eliminated in some places due to legal and political actions. | 5 |

| Data Collection and Monitoring | ||

| 7-1 | Health data granularization and access to the data are still lacking for some minoritized populations. | 7 |

| 7-2 | Metrics that measure and track progress to advance racial and ethnic inequities have been created and adopted by health care systems, health insurance payers, professional organizations and accrediting bodies, and researchers, but wide variation exists in many of the equity performance measures. | 8 |

| 7-3 | The Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality has published the National Healthcare Quality and Disparities Report over the past 2 decades to highlight trends in inequities across health care settings. | 1 and 8 |

| 7-4 | Several studies report racial and ethnic data by OMB categories, but data are still lacking for some minoritized populations. | 7 |

| Research Needs | ||

| 8-1 | Research to document and track racial and ethnic inequities has increased. The research on multilevel and structural interventions focused on eliminating these inequities is limited. Significant research is still needed. | 7 |

| 8-2 | A limited number of implementation and comparative effectiveness studies have focused on promising health care intervention strategies. The research infrastructure, including data sources, is insufficient to support the types and scale of health equity research needed. | 7 |

- Establishing public-private stakeholder coordination for community-level engagement; and

- Conducting and funding more research to understand and reduce inequities in health and health care.

The committee reviewed these reports, their recommendations, and supporting evidence in depth during its deliberations. Additional details about that process are described later in this chapter.

THE U.S. HEALTH CARE SYSTEM CONTINUES TO PERFORM POORLY

The U.S. health care system fares poorly compared to similarly high-income countries (Schneider et al., 2021) in terms of most performance measures, despite spending at least double the amount of money per person of peer wealthy countries (Schneider et al., 2021). Even after accounting for age, sex, body mass index, income, employment status, education, alcohol consumption, and smoking history, the United States has a significantly higher prevalence of chronic diseases and individuals with multiple chronic diseases compared to Canada, United Kingdom, and other similarly industrialized countries (Hernández et al., 2021). (Chapter 3 offers extensive details about the racial and ethnic inequities across many of these multiple disease categories.) The United States has the largest proportion of people without health insurance among high-income countries (Schneider et al., 2021). The uninsured rate ranges from 8.4 percent (CDC, 2023a) to 9.6 percent (Tolbert, et al., 2023). Nearly 90 percent of U.S. health care spending is on chronic physical and behavioral health conditions, leaving limited funding for disease prevention and health promotion (CDC, 2023b). The poor performance of the nation’s health care system impacts everyone: The United States ranks last among high-income countries in life expectancy at birth, maternal and infant mortality, suicide, and preventable and treatable mortality (OECD, 2023).

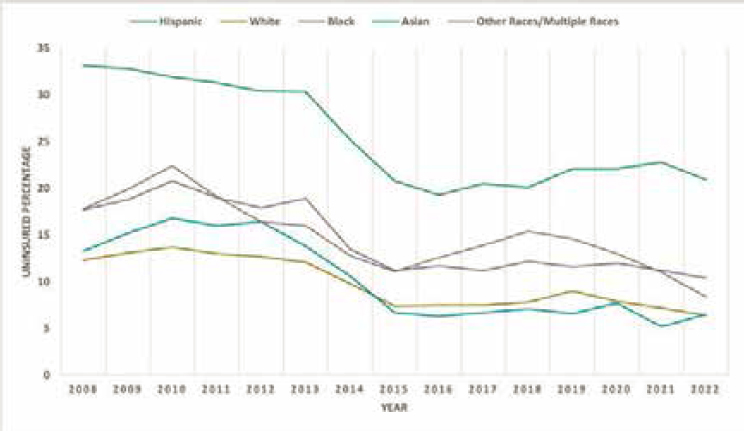

The U.S. health care system is not working perfectly for anyone. However, its inadequacy disproportionately affects minoritized populations. Looking at one metric, the percentage of the population that lacks health insurance, rates have remained high across all populations but are highest for minoritized populations. As of 2022, the rate among Hispanic individuals is 20.9 percent; it is 10.4 percent for Black (non-Hispanic Black), 6.4 percent for White (non-Hispanic White), and 6.5 percent for Asian (non-Hispanic Asian) groups. The rate for all others (“Other”) is 8.4 percent (see Figure 1-1).

NOTES: Rates are shown for age under 65, based on annual data from CDC. “Hispanic” is Hispanic or Latino; “White” is non-Hispanic White, single race; “Black” is non-Hispanic Black, single race; “Asian” is non-Hispanic Asian, single race; and “Other” is non-Hispanic other races and multiple races. CDC data are not available for 2003–2007.

SOURCES: For 2008–2013, the data are from this aggregate report: https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nhis/earlyrelease/insur201406.pdf. For 2014–2018, the data are from this aggregate report: https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nhis/earlyrelease/insur201905.pdf For 2019–2022, the data were obtained from Table V of this report: https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nhis/earlyrelease/insur202305_1.pdf.

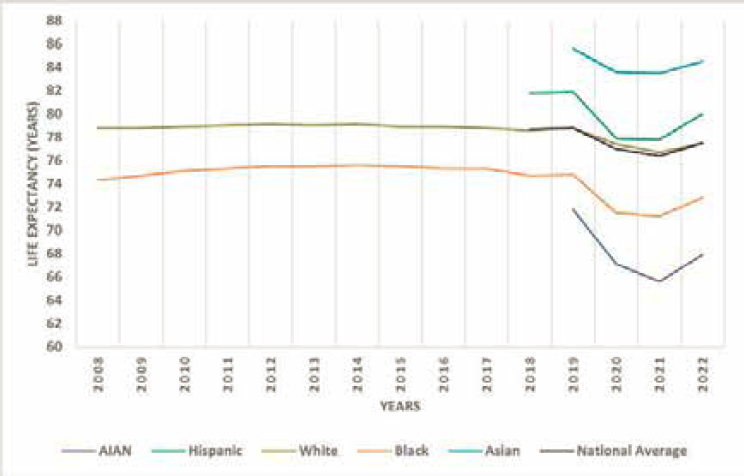

The inadequacy of the system also impacts life expectancy2 and potential years of life lost3 by race and ethnicity. Figure 1-2 shows stark differences. White life expectancy increased from 77.2 years in 2003 to 78.8 years in 2019 before declining to 77.0 years in 2020 and increasing to 77.5 years in 2022. By contrast, Black life expectancy was 72.4 years in 2003 before rising to 74.8 years in 2019, declining to 71.5 years in 2020, and increasing to 72.8 years by 2022. Hispanic life expectancy was not tracked by the U.S. Centers for Disease Control (CDC) until 2006, when it was 80.3 years; it rose to 81.9 years in 2019. In 2020, it dropped to 77.9 years; by 2022, it was

___________________

2 The average number of years of life a person who has attained a given age can expect to live.

3 The estimated average time a person would have lived had they not died prematurely.

NOTES: Life expectancy at birth is calculated in years. “White” refers to non-Hispanic White for 2008–2022. “Black” refers to non-Hispanic Black for 2008–2022. The calculations for Asian and AIAN populations are not available before 2019. AIAN: American Indian and Alaska Native.

SOURCES: For 2008–2019, the data are from https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/hus/contents2020-2021.htm#Table-LExpMort. The 2020 data are from https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nvsr/nvsr71/nvsr71-01.pdf table 19; 2021 data are from https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nvsr/nvsr72/nvsr72-12.pdf; and 2022 data are from https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/vsrr/vsrr031.pdf.

at 80.0 years, just below its 2006 level. American Indian or Alaska Native (AIAN) life expectancy was reported by CDC beginning in 2019 and is the lowest across all tracked categories; it dropped from 71.8 years in 2019 to 67.1 years in 2020 and only increased to 67.9 years in 2022. Asian life expectancy was also reported by CDC beginning in 2019 and is the highest across all categories. It was 85.6 years in 2019, dropped to 83.6 years in 2020, then increased to 84.5 in 2022. The significant drops in life expectancy for all people in 2020 sounded the alarm of a failing health care system, unable to respond to a public health crisis, but were most drastic for minoritized populations. One recent analysis over a 22-year period also reported that Black populations had over 80 million potential years of life lost compared to their White counterparts (Caraballo et al., 2023).

THE ECONOMIC BURDEN OF PERSISTENT INEQUITIES

The poor performance of the U.S. health care system and negative repercussions of health and health care inequities go far beyond each individual’s health and specific medical conditions, with significant economic consequences for the entire nation. LaVeist and colleagues (2023) estimated the economic burden of racial and ethnic health inequities in the United States. They found that the overall economic burden of heath inequities in 2018 was $1.03 trillion (LaVeist et al., 2023). The economic burden of racial and ethnic health inequities was $421.1 billion for minoritized population (American Indian and Alaska Native, Asian, Black, Latino, and Native Hawaiian and Other Pacific Islander populations). Nearly two-thirds of the estimated economic burden was attributable to premature death with the remaining portion attributable to excess medical care costs and lost labor market productivity. The economic burden for White population was estimated to be $608.7 billion. Minoritized population experienced the highest per-capita economic burden after accounting for population size. Addressing health care inequities will improve personal and population health and could also produce significant economic benefits.

Addressing Inequities Benefits All People

Addressing inequities and improving the health of individuals in the most disadvantaged communities improves the quality of care for everyone and advances population health. This goes beyond the individual and extends to their children, whole communities, and society at large. Parents too sick to work, for example, will earn less money and be less able to provide for their children. Unemployed, low-income families will have more social service needs and be less likely to have access to private health insurance. Their continued inability to afford necessary health care may lead to them becoming sicker, making them even less able to find a new job; getting healthy and keeping their families out of poverty becomes increasingly more difficult.

Some feel that health and health care is a zero-sum game (Norton and Sommers, 2011) and that supporting governmental health care programs would primarily benefit minoritized populations and lead to discrimination and loss for majority populations (Wetts and Willer, 2018). Significant evidence suggests that this is not true for health care and other sectors of society. Implementing interventions for minoritized populations will improve health outcomes for everyone (McGhee, 2022).

Population health and public health approaches can enable targeting health care resources to specific populations in ways that benefit all people. This rationale was advanced in an IOM report on the consequences of

uninsurance (IOM, 2009). That report noted that when community-level uninsurance rates are relatively high, insured people have greater difficulty obtaining needed health care. Because uninsurance and other barriers contributing to health care inequities are concentrated in communities with more minoritized individuals, these barriers are likely to have adverse spillover effects on other individuals in these communities, such as longer waits for care of major trauma and other acute emergencies; delayed diagnosis and treatment leading to greater spread of infectious diseases, such as COVID-19 and influenza; more fragmented systems of chronic disease care; and more instability of all health care providers in the area who rely on consistent rates of insurance coverage in the community to keep their doors open.

Poor health outcomes for minoritized communities contribute to lower-quality care and outcomes for everyone. Because inequitable policies and barriers make it difficult for minoritized populations to regularly access quality health care, they are often only able to access care when disease symptoms have advanced, and emergency department care is frequently their only option (Rust et al., 2008). This limited access can result in overreliance on emergency department care, which is a contributor to emergency department overcrowding (IOM, 2007; Kelen et al., 2021). Overcrowding and subsequent emergency department boarding could lead to poor outcomes for everyone but disproportionately for minoritized patients (IOM, 2007; Liu et al., 2011). Similarly, barriers to accessing health insurance disproportionately impact poor and minoritized populations. Expansions facilitated by the Affordable Care Act (ACA) extended coverage to many uninsured and underinsured individuals and has been associated with improved access to the full range of health care services for all racial and ethnic groups (Wehby and Lyu, 2018). The Medicaid expansions have been particularly beneficial in improving access to health care services and addressing inequities for all people in those states that have participated (Allen et al., 2017; Mazurenko et al., 2018). Inequities still persist across all states. This is true even in those states that have been found to have better health system performance or where health outcomes have improved over time (Radley et al., 2024).

STUDY CHARGE

It has been over 20 years since the Unequal Treatment report, and much work remains to advance U.S. health care equity. Thus, NIH charged the National Academies with conducting a study to highlight the major drivers of health care disparities, provide insight into successful and unsuccessful interventions, identify gaps in the evidence base, propose strategies to close those gaps, consider ways to scale and spread effective interventions to reduce racial and ethnic disparities in health care, and make recommendations to advance health equity (see Box 1-2).

BOX 1-2

Statement of Task

An ad hoc committee of the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine will examine the current state of racial and ethnic health care disparities in the United States. This work will include support for the infrastructure and activities required to update the 2003 Unequal Treatment report. The update will highlight the major drivers of health care disparities, provide insight into successful and unsuccessful interventions to reduce disparities, identify gaps in the evidence base, and propose strategies to close those gaps. The committee will consider ways to scale and spread effective interventions to reduce racial and ethnic disparities in health care and make recommendations to advance health equity.

National Academies will conduct a scoping review of the literature on racial and ethnic health care disparities in the years since the Unequal Treatment report (2003–2022). This task will also provide a comprehensive status update on the implementation of the IOM report recommendations, as well as whether specific health care disparities have improved, remained the same, or worsened. The topics will include but are not limited to:

- Societal factors such as bias, racism, discrimination, intersectionality, stereotyping and intersectionality at the individual (clinical and non-clinical staff), interpersonal, institutional, and health system levels.

- Technology factors, such as bias in diagnostic tools and algorithms used in clinical practice and decision-making, and variability in access to broadband Internet and other telecommunication technologies, as well as digital inequality.

- Geographic factors, such as variability in the social determinants of health, language and English proficiency, and access to both social services (including those not directly related to health care), language, and health care services for acute and chronic conditions in different communities.

- Policy factors, such as federal and state laws and regulations and public health programs.

- Health care factors, such as the coverage and design of health plans, institutional or clinic-based access, and the demographic and specialty profile of the clinical workforce.

- The impact of clinical training and education in perpetuating disparities, and ways to improve training, enhance cultural competency, and diversify the health care workforce.

- The committee will also consider ways to scale and spread effective interventions to reduce racial and ethnic disparities in health care.

The review and summary of findings will focus on the Office of Management and Budget (OMB) defined racial and ethnic groups, report disaggregated findings where possible (e.g., by country of origin or national heritage). The literature review should also:

- Incorporate evidence on racial and ethnic disparities in health care measured by access, utilization, and quality of care given that major advancements related to health care policy (e.g., ACA), demographic shifts, and public health emergencies (e.g., COVID-19) have differentially impacted people from racial and ethnic groups and may have exacerbated disparities.

- Examine health care disparities across the spectrum of health care settings with an emphasis on primary care in the continuity outpatient setting but also including specialty outpatient care, emergency or urgent care, and hospital care.

- Examine racial and ethnic health care disparities across the lifespan (e.g., between racial and ethnic minority children and older adults compared with their White counterparts and the relationship between adverse childhood experiences [ACEs] and how these pathways develop into health disparities in later life).

- Determine the interventions that have been most effective at the local, state, and federal levels for reducing racial and ethnic disparities in health care using the intervention strategies outlined in the previous report as a guide.

- Identify the institutional, community based, or community engaged approaches that have addressed racial and ethnic disparities in health care access, utilization, and quality of care and quantify those with the most positive impact.

- Determine the community engaged research approaches that are most replicable and scalable.

Drawing on this detailed literature review, and supplemented by public input, the committee will apply its expert judgement in order to develop recommendation with a focus on advancing health equity.

STUDY APPROACH

The National Academies appointed a 17-member multidisciplinary committee. The Committee on Unequal Treatment Revisited: The Current State of Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Health Care included experts in health and social policy, social determinants of health (SDOH), social justice, health inequities, minoritized populations, public health, primary care, health economics, health technology, health care services research, health care financing, community-engaged research, health professions education, health law, and ethics (see Appendix E for the biographies of the committee members).

A variety of sources informed the committee’s response to the study charge. First, the committee conducted a review of the literature relevant to the statement of task, focused on peer-reviewed articles, government documents, and white papers published since 2003. The search focused mainly on studies conducted in the United States, but for interventions to reduce health care inequities, the committee was interested in worldwide publications. To supplement the literature review, the committee commissioned three papers, documenting evidence on racial and ethnic inequities in health care measured by access, use, and quality of care; the evolution of U.S. health care and civil rights laws since 2003 that pertain to the study task; and policy initiatives that have been effective for reducing racial and ethnic inequities in health care.

The committee conducted a series of virtual public workshops4 to obtain insights on racial and ethnic inequities in health care and current and new approaches to alleviate them. A proceedings summarizing the discussions and highlighting individual participants’ suggestions was published by the National Academies Press in January 2024 (NASEM, 2024). Statements, recommendations, and opinions expressed in the proceedings are those of individual presenters and participants and not endorsed or verified by the committee, and they should not be construed as reflecting any group consensus. Additional input was provided by members of the public, who were given an opportunity to share their relevant experiences, thoughts, and comments for the committee’s consideration through the project website at any time during the study period.

Study Parameters

The committee recognizes that inequities in health care are complex, multifactorial, and interconnected with social and public policies, including structural racism and other social inequities, topics discussed extensively

___________________

4 The virtual workshops were held on July 12–13, 2023, August 16–17, 2023, and September 6, 2023.

in consensus reports from National Academies (NASEM, 2019, 2023). Furthermore, the committee recognizes that the most effective interventions for health care inequities may require efforts outside the health care system. Therefore, the committee emphasizes that changes to health care systems and clinical care are essential but will be insufficient to advance racial and ethnic health equity. In addition, the committee acknowledges that certain populations, including immigrants, people with disabilities, and sexual and gender minorities, experience differential and disproportionate effects of inequitable treatment that intersect with and extend beyond their race and ethnicity (NASEM, 2020). For this study and its specific task, the committee did not extensively examine the evidence base related to achieving health equity broadly but focused on racial and ethnic inequities in the health care system, especially in terms of care access, use, and quality. The committee, however, notes areas of overlap between advancing health care and health equity.

Definitions of Key Terms

The terms used in this area of research have evolved over time and will continue to do so as further insights are gained and society and demographics shift. Thus, it is necessary to provide some conceptual clarity for key terms to ensure that the report audiences are starting from the same place in how the committee defines them. The committee chose to use “health” when discussing outcomes and “health care” when discussing the system that delivers care. The committee’s rationale for this approach is summarized in Box 1-3.

The committee made an intentional choice to use “inequities” rather than “disparities” and “inequitable treatment” rather than “unequal treatment.” Box 1-4 presents its reasoning.

Description of Racial and Ethnic Groups

As attitudes toward different cultures and conceptions of race and ethnicity have evolved, so have the terms used to describe various populations. This evolution is perhaps most notable in changes the U.S. Census Bureau has made in the methods and language used to record race and ethnicity. Revisions or additions are made each decade, underscoring the complexity of collecting data on identity and classification and the resulting challenges in comparing demographic data over time. In addition, on March 28, 2024, OMB released revised standards to how the federal government collects data on race and ethnicity that updated those in use by the federal government since 1997. Changes in the revised standards include combining race and ethnicity into one question and adding a category of Middle Eastern

BOX 1-3

Health, Health Care, and Health Care System

The study statement of task to the committee specifies that “the committee will consider ways to scale and spread effective interventions to reduce racial and ethnic disparities in health care and make recommendations to advance health equity.” The statement of task also directed the committee to “apply its expert judgment in order to develop recommendations with a focus on advancing health equity.”

In its deliberations, the committee recognized that health and health care are different but inextricably linked. “Health” is a state of complete physical, mental, and social well-being and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity, while “health care” refers to the services provided to individuals, families, and communities for the purpose of promoting, maintaining, or restoring health across settings of care. Furthermore, the committee acknowledges that reductions in health inequities will require simultaneous improvements to health care as well as the many factors beyond health care that influence health, as shown in the committee’s conceptual framework. In this report, the committee frequently uses the terms health care and health together, because interventions to reduce racial and ethnic health care inequities also commonly advance health equity.

Additionally, the committee recognizes that when addressing health care equity, the most effective interventions may depend not on the health care system, but rather on efforts outside of it. Thus, the committee argues that changes to health care systems and clinical care alone are insufficient to advance racial and ethnic health equity. A society with a perfect health care system could still have significant health inequities.

This report also uses “health care system” (activities related to the delivery of care across the continuum of care) to describe the U.S. health care system as a whole as well as to describe individual health care systems and uses “health” when discussing outcomes.

BOX 1-4

Inequities Versus Disparities; Inequitable Versus Unequal Treatment

Inequities Versus Disparities

The original Unequal Treatment report defined disparities in health care as “racial or ethnic differences in the quality of health care that are not due to access-related factors or clinical needs, preferences, and appropriateness of intervention” (IOM, 2003). More specifically, that committee focused on two main areas as the drivers of health care disparities: the legal and regulatory climate in which health care systems operate and discrimination at the individual, patient–provider level. In the 20 years since, research has provided a better understanding about these drivers and identified several other important factors that contribute to inequitable outcomes in health and health care. The Healthy People 2030 report defined a health disparity as the following:

a particular type of health difference that is closely linked with social, economic, and/or environmental disadvantage. Health disparities adversely affect groups of people who have systematically experienced greater obstacles to health based on their racial or ethnic group; religion; socioeconomic status; gender; age; mental health; cognitive, sensory, or physical disability; sexual orientation or gender identity; geographic location; or other characteristics historically linked to discrimination or exclusion. (HHS, 2024)

The Healthy People 2030 report defined health equity as the following:

the attainment of the highest level of health for all people. Achieving health equity requires valuing everyone equally with focused and ongoing societal efforts to address avoidable inequalities, historical and contemporary injustices, and the elimination of health and health care disparities.

Health inequity refers to a state of being in which someone is denied the possibility of being healthy by belonging to a group that historically has been economically and socially disadvantaged. In that context, it is an avoidable, unnecessary, and unjust health difference (Whitehead, 1992). Health disparities are the metric for measuring progress toward achieving health equity and reducing them is a step toward greater health equity (Braveman, 2014). Achieving health equity requires valuing

everyone equally with focused and ongoing societal efforts to address avoidable inequalities and historical and contemporary injustices and eliminate health and health care disparities due to past and present causes.

This report uses the term “inequities” instead of “disparities” in most cases (except when citing a publication that explicitly measured disparities). The committee had several reasons for updating this language when discussing health care. First, although many definitions exist for “health inequities,” the committee preferred to draw attention to those definitions that focus on these differences being avoidable, unfair, unjust, and affected by social, economic, and environmental conditions. This intentional use of “inequities” highlights the committee’s emphasis on the role of SDOH and economic conditions in producing health and health care disparities. Second, the committee emphasized that the differences in health outcomes that this report discusses are not inevitable or acceptable. Instead, they are caused by many unfair circumstances, including the legal and regulatory climates, structural racism, and policy and political decisions made by those in power. This language shift is necessary because not using the most precise terminology can lead to not considering solutions that address the full scope of the problem.

Inequitable Versus Unequal Treatment

Although “inequitable” and “unequal” sound interchangeable, they are based on different concepts. In a health care treatment context, the term “equity” best captures the fact that different individuals need different supports or treatments to achieve similar outcomes. By contrast, the term “equality,” which is central to the foundational purpose of civil rights law and policy, could lead people to mistakenly believe that equal opportunity for optimal health is achieved only when everyone receives identical supports or treatment.

Unequal Treatment identified numerous social factors, including race and ethnicity, that lead to “unequal treatment.” Using “unequal treatment” implied that health care inequities could be eliminated by providing the same treatment to all patients regardless of their race or ethnicity. However, with the availability of electronic health record systems and the ability to analyze observational population data, it is clear that equal treatment is not necessarily equitable. For example, different individuals with the same condition, such as hypertension and diabetes, often have different prognoses and responses to treatment, largely resulting from genotypic and phenotypic variation and social and environmental differences. Applying the same (i.e., equal) treatment to all patients with the same health condition diagnosis overlooks these crucial factors, underscoring the need for personalized treatment that may not be the same treatment for every person.

To address this, the current committee focused on an equitable process of making treatment decisions. This entails having a full understanding of the determinants of health—many of which are social determinants—when making treatment recommendations that do not disadvantage an individual based on race, ethnicity, or social position. Health equity programs should focus on achieving optimal outcomes for individuals, including careful attention to implicit biases associated with race and ethnicity and other SDOH. By recognizing and promoting effective strategies to address these harmful biases, the nation can work toward a health care system that prioritizes individual needs and reduces inequities, moving closer to health care equity for all.

or North African, which was previously in the “White” category. This is discussed in detail in Chapter 7. Box 1-5 summarizes specific racial and ethnic terms and other key definitions and terms used in this report. The committee drew and adapted key terms and definitions from other National Academies5 and government agency reports.6

“American Indian Alaska Native” (AIAN) is used when discussing individuals or populations having origins in any of the original peoples of North America, South America, and Central America, who maintain tribal affiliation or community attachment. The committee also acknowledges that “Hispanic” is widely used in policy and research discussions when referring to this group. Nonetheless, the committee recognizes that Latin America and the Caribbean are home to many colonial and Indigenous languages and cultures. Therefore, the committee chose to use “Latino/a” unless the data specifically denote Hispanic. The committee acknowledges that the terms “African American” and “Black” are used interchangeably in research and that “non-Hispanic Black” also appears, but it uses “Black” unless the data specifically denote “African American.” The committee acknowledges that “non-Hispanic White” is used in research, but it refers

___________________

5 See NASEM. 2023. Federal policy to advance racial, ethnic, and tribal health equity. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; NASEM. 2023. Advancing antiracism, diversity, equity, and inclusion in STEMM organizations: Beyond broadening participation. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

6 HHS. 2024. Healthy people 2030 social determinants of health. https://health.gov/healthy-people/priority-areas/social-determinants-health (accessed April 29, 2024); HHS Office of Minority Health. 2024. American Indian/Alaska Native Health. https://minorityhealth.hhs.gov/american-indianalaska-native-health (accessed April 29, 2024). CDC. 2022. What is health equity? https://www.cdc.gov/healthequity/whatis/index.html (accessed April 29, 2024).

BOX 1-5

Key Terms

Specific Populations

- African American: U.S.-born people who have African ancestry, typically used for descendants of people from Africa who were enslaved in the United States as well as all people of African ancestry who are now citizens or permanent residents.

- American Indian or Alaska Native: This population includes people having origins in any of the original peoples of North America, South America, and Central America, who maintain tribal affiliation or community attachment. Although these individuals are also often described along with other racial and ethnic groups, the phrase “American Indian and/or Alaska Native” is distinct because it is used in the context of legally enforceable obligations and responsibilities of the federal government to provide certain services and benefits to members or citizens (and, in some cases, descendants) of federally recognized Tribal Nations. “Indigenous” and “Native American” are also commonly used but not specific enough to describe the special political status of American Indian and Alaska Native Tribal Nations. These people may be served by policies or programs that relate to the U.S. federal government’s trust responsibility and government-to-government relationship with federally recognized Tribal Nations.

- Asian American: a resident of the U.S who self-identifies as Asian or as one of the ethnic or detailed origin groups classified by the U.S. government as Asian; an individual does not need to be a U.S. citizen or permanent resident.

- Asian: a person having origins in any of the original peoples of the Far East, Southeast Asia, or the Indian subcontinent. The committee recognizes that the term “Asian” is commonly used in research and acknowledges that it is inadequate to describe the diversity among these groups of people.

- Black: a person who was born in or outside of the United States and has origins in any of the Black ethnic groups of Africa. An umbrella term including African American, African, Afro-Caribbean, and other people of African descent.

- Hispanic or Latino/a/e: refers to a person of Mexican, Puerto Rican, Salvadoran, Cuban, or other Latin American and Caribbean cultural origin, regardless of race.

- Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander: a person having origins in any of the original peoples of Hawaii, Guam, American Samoa, Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands, or other Pacific Islands, including all sovereign/independent Pacific Island countries, including the Compact of Free Association States.

- White: a person having origins in any of the original peoples of Europe or the Middle East or North Africa.

- Middle Eastern or North African (MENA): refers to a person from Middle East or North Africa. Until the OMB update in March 2024 on how the federal government collects and reports data on race and ethnicity, the MENA category was included under the “White” reporting category.

- Race: a socially constructed, shorthand concept dating to the 15th century, that categorized populations into an arbitrary, hierarchical classification framework, largely based on phenotypic characteristics, such as skin color. Although race is not a valid biological concept the construct of race has profound implications on how the health care system is designed and operates in the United States. It influences the outcome of the individuals experiencing the care (as discussed in Chapter 3), laws and policies pertaining to health care (discussed in Chapter 4), and how health care is delivered (discussed in Chapter 5). It is also a social construct that is linked to racism that gives or denies benefits and privileges to racially minoritized people and groups.

- Ethnicity: In contrast to race, ethnicity has a stronger relationship with place. It is a socially constructed term used to describe people from a similar national or regional background who share common national, cultural, historical, and social experiences.

- Multiracial: people who identify with more than one race.

- Tribal: describes Tribal Nations in the United States but is also used as an adjective to describe circumstances related to them, such as tribal communities or tribal policies. It is not appropriate for Native Hawaiians or Pacific Islanders.

- Community: Any configuration of individuals, families, and groups whose values, characteristics, interests, geography, and/or social relations unite them in some way.

Other terms

- Health-related social needs (HRSNs): Social and economic needs that affect individuals’ ability to maintain their health and well-being. These include employment, affordable and stable housing, healthy food, personal safety, transportation, and affordable utilities.

- Implicit bias: the neurobiologically based, automatic attitudes and beliefs about particular social groups and their members.

- Institutional racism: policies and practices within institutions that, intentionally or not, produce outcomes that chronically favor White individuals and put individuals from minoritized racial and ethnic groups at a disadvantage.

- Oppression: a state in which people have unequal power and the process by which dominant groups use power to subjugate dominated groups.

- Optimal health: a dynamic balance of physical, emotional, social, spiritual, and intellectual health.

- Racism: the combination of policies, practices, attitudes, cultures, and systems that affect individuals, institutions, and structures unequally and confer power and privilege to certain groups over others, defined according to social constructions of race and ethnicity.

- Social determinants of health (SDOH): Conditions in the environments in which people live, learn, work, play, worship, and age that affect a wide range of health, functioning, and quality-of-life outcomes and risks. SDOH can both promote and harm health. In this report, SDOH are organized by the Healthy People 2030 domains: economic stability, education access and quality, health care access and quality, neighborhood and built environment, and social and community context.

- Social risks: Specific adverse social conditions associated with poor health and health care–related outcomes.

- Structural determinants of health: Macrolevel factors, such as laws, policies, institutional practices, governance processes, and social norms, that shape the distribution (or maldistribution) of SDOH, such as housing, income, employment, exposure to environmental toxins, and interpersonal discrimination, across and within social groups. Structural determinants of health, also referred to as the “determinants of the determinants of health,” include structural racism and other structural inequities and thus influence not only population health but also health equity.

- Structural or systemic racism: the totality of ways in which a society fosters racial and ethnic inequity and subjugation through mutually reinforcing systems, including housing, education, employment, earnings, benefits, credit, media, health care, and the criminal legal system. These structural factors organize the distribution of power and resources differentially among racial, ethnic, and socioeconomic groups, perpetuating racial and ethnic health inequities. The key difference between institutional and structural racism is that they happen within versus across institutions, respectively.

- Xenophobia: Attitudes, prejudices, and behavior that reject, exclude, and often vilify persons, based on the perception that they are outsiders or foreigners to the community, society, or national identity.

to these populations as “White.” Finally, the committee acknowledges that “Asian” is widely used in policy and research discussions but recognizes that it is inadequate to describe the diversity among the populations categorized in this group. Unfortunately, much of the research uses this term and does not include subpopulations. Therefore, the committee chose to use “Asian” except when citing a publication that explicitly captures data on subpopulations.

In addition, rather than referring to “racial and ethnic minorities,” “members of minority groups,” or “underrepresented minorities,” the committee uses “minoritized”7, which refers to people from groups that have been historically and systematically socially and economically marginalized or underserved based on their race or ethnicity as a result of racism. The committee wishes to make the distinction that being minoritized is about not the number of people in the population but rather power and equity.

LOOKING BACK AND LOOKING FORWARD

Since 2003, the U.S. health care system has made progress on developing infrastructure to monitor inequities, including numerous performance measures. Mandated by Congress, the federal government now reports on health care quality and inequities experienced by racial and ethnic groups. A growing body of research has documented continuing inequities that marginalized and minoritized populations experience in the health care system. For example, the National Healthcare Disparities Report (NHQDR), published by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) since 2003, has revealed the persistent inequities in health care for marginalized and minoritized populations. These inequities exist across all states and persist even in situations where health outcomes have improved over time (Radley et al., 2024) (see Chapter 3 for detailed discussion on evidence on racial and ethnic inequities in health care).

Federal, state, local, tribal, and territorial governments have made efforts (see Chapter 8) to address these inequities through laws, policies, and programs. For example, executive orders issued in the past few years have sought to strengthen racial equity throughout the federal government, including health care. Multiple federal health agencies, including NIH, CDC, and the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS), have increased their commitment to promoting racial health and health care equity. CDC declared racism a public health threat (CDC, 2023c). These actions, bolstered by

___________________

7 This term was also used in the 2023 National Academies report Federal Policy to Advance Racial, Ethnic, and Tribal Health Equity.

extensive evidence, have created a continuing impetus for research aimed at developing and implementing effective interventions to advance racial and ethnic equity and identify strategies to mitigate systemic racism in health care. However, policy statements and research findings have not reduced racial and ethnic health care inequities, and critical laws and policies have not been implemented.

Recommendations 7-1, 7-2, 7-3, and 7-4 of the 2003 report pertained to measuring inequities and monitoring progress toward eliminating them. Many reports, such as the NHQDR, have been created over the past 20 years. However, our committee concluded that the 2003 recommendations calling for data and monitoring have not been fully implemented due to the lack of consistent and comprehensive standards for race and ethnicity data—no standards for which data are to be collected, by whom, and in what settings and who is accountable for data collection, accuracy, and analysis and taking actions based on the findings.

Access to equitable health care remains a significant problem, driven at its core by a continued lack of universal, stable health insurance. An increase in the design and implementation of antiracism and cross-cultural education work in health professional training programs as called for in Recommendation 6-1 of Unequal Treatment spurred little action to address the fundamental social and economic inequities that contribute to inequitable health care.

Looking Back: Why Substantial Progress Has Not Been Made

The past 2 decades have witnessed major policy strides toward greater equity in health care, particularly the ACA in 2010. Setbacks have also occurred, chiefly resulting from judicial developments that weakened some ACA provisions designed to address health care inequities, ended the constitutional right to accessing reproductive health care services, and disrupted efforts to achieve greater educational diversity.

The ACA was informed by evidence documenting where and how discrimination appears in the health care system and the urgent need for far-reaching policy solutions. This evidence demonstrates persistent patterns of inequity and their underlying drivers and an increasing awareness and understanding of how social conditions shape health care inequities. However, in the committee’s deliberations and research, it found that forward motion has yet to yield long-term gains. Most racial and ethnic health care inequities have persisted, and some have worsened. This report documents the lack of clear pathways to translate promising approaches into real and permanent change, which is especially significant because progress on key measures of racial and ethnic equity in health care has stagnated and is sometimes deteriorating.

The committee identified multiple factors contributing to this lack of progress, summarized as follows:

- Policies that fall short of the changes needed or are weakly implemented: The past 2 decades have seen major strides in policy, moving closer to a system of affordable coverage for all. Investments have expanded support for primary care clinics in underserved rural and urban communities. Nonprofit hospitals have been nudged toward greater community accountability. The nation has a landmark civil rights framework for health care. However, owing to the structural limitations of key policy reforms, millions of people remain uninsured and underserved. Primary care workforce shortages have worsened, and access is severely strained. Furthermore, some civil rights reforms have not been implemented, with no accountability or penalty when measures are not obtained.

- Continuing racism in health care and society, at large: Unequal Treatment documented pervasive racism in health care, deeply embedded in the very structure of the system. Since 2003, the nation has gradually acknowledged the problem more explicitly, punctuated by outpourings of societal rage immediately after horrific events, such as the murder of George Floyd. In recent times, many organizations are attempting to measure racism and define its characteristics. Yet, many of the factors, institutions, and structures that produce racism remain in place.

- An overemphasis on treating sickness and incentivizing those who treat sickness: The health care system is designed to treat people who are sick. The sicker someone becomes, the more money the system makes. Payments are designed to incentivize curing disease, not preventing it. The financial gains reaped when people get sick are even greater when health inequities worsen. When sick people (many with preventable illnesses) fill a hospital, the hospital makes more money, but anyone who needs emergency care cannot get it efficiently.

- A complex and fragmented health care system: The system is extraordinarily complex, dominated by fragmentation in care financing and delivery. This presents overwhelming challenges for individuals, families, and communities and provides little or no assistance in navigating these challenges.

- Failure to invest in promising solutions: Extensive documentation points to highly promising models of health care, especially solutions that engage communities and are integrated into community settings. Many of these demonstration programs combine health care and social services essential to addressing underlying

- problems that contribute to poor health, have adapted operations in communities in responsive ways, and are staffed by health care professionals recognized for providing and enabling accessible and culturally competent care. Yet, underfunding of such programs persists, and many have not been able to scale up or achieve sustainability.

- Failure to pursue promising avenues of research: A wealth of evidence documents the inequities across health care settings and over the life course. Yet, the nation has not adequately pursued promising avenues of research that can help identify, scale, and spread solutions.

The effect of these factors has been magnified by a series of shocks to the nation, including an opioid epidemic and the COVID-19 pandemic. The committee predicates its conclusions and recommendations on the conviction that the nation knows how to address the problem of inequitable health care. What is needed is both a firm belief that the situation needs to change and the will to make the right investments.

Looking Forward: A Conceptual Framework to Guide Future Steps

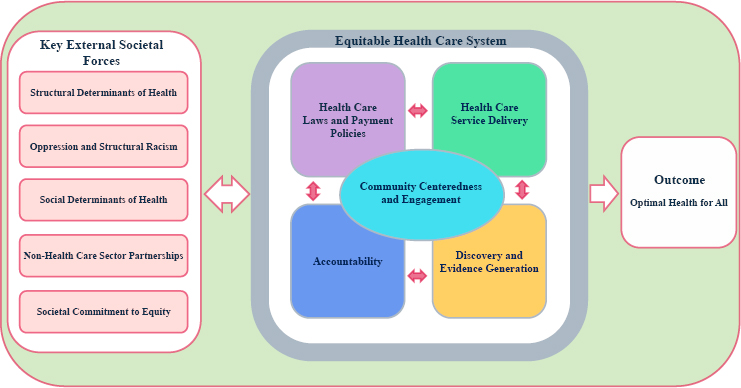

To guide its deliberations, the committee focused on the health care system broadly (including public health and community-partnered care) and developed a conceptual framework to serve as a unifying basis for its approach to the report organization and recommendations for action (see Figure 1-3).

Because the health care system exists within the larger society, the conceptual framework highlights five key societal external forces, each representing a significant influence on equitable health care: structural determinants of health; oppression and structural racism; social determinants of health (SDOH); non–health care sector partnerships; and societal commitment to equity. These key external societal forces act individually, intersect with one another, and constantly interact with the domains in the health care system to pose significant influence on equitable health care.

- Structural determinants of health influence the distribution of HRSNs (social and economic needs that affect individuals’ ability to maintain their health and well-being) across different populations to reinforce or mitigate health care inequities.

- Oppression and structural racism, through historical and continued policies such as residential segregation, systemic oppression, or any form of bias, harm health through multiple pathways. These pathways result in adverse physical, social, behavioral, and economic impacts that directly and indirectly affect the health care system.

NOTE: The key external societal forces act individually, intersect with one another, and constantly interact with the domains in the health care system that are also constantly interacting with each other to significantly influence equitable health care.

- Deprivation of resources and adverse SDOH conditions in the environments in which people live, learn, work, play, worship, and age that affect a wide range of health, functioning, and quality-of-life outcomes and risks) disproportionately impact minoritized populations and manifest as unmet HRSNs, which many health care systems are unable to address, further exacerbating inequities in care access, quality, and outcomes.

- The interest of partners outside the health care sector, such as social service agencies, can shape priorities and programs of health care systems, either negatively, by exacerbating inequities and widening inequity gaps, or positively, by unlocking long-term opportunities to advance health care equity.

- Societal commitment to identify and remove barriers and create equitable access to resources to achieve equal opportunities positively impacts health and health care; the lack thereof reinforces health and health care inequities.

Within the health care system, the committee identified four key intersecting domains—each with subdomains—that are critical mechanisms by which the system can reinforce or mitigate health care inequities. All four domains intersect within local communities where health care systems

operate, and care delivery ultimately happens. As discussed throughout this report, community plays a vital role in health and health care; it is a critical determinant of health and can produce mechanisms central to advancing equity.

- Health Care Laws and Payment Policies. Policies to support equitable health care access, quality, and affordability serve as the foundation to remove persistent barriers and ensure that all individuals receive equitable health care services. Factors in this domain include health care reforms, legal, and political environment that have implication for achieving health care equity and optimal health for all.

- Health Care Service Delivery. This domain focuses on delivering of high-quality, culturally sensitive care to all and maximizing the health care system’s potential to eliminate racial and ethnic inequities in health and health care. Factors in this domain include health care delivery models, health care workforce, clinical decision making, implicit bias, integrating health and social care, individual care seeking behavior and medical mistrust, health literacy, and health information technology.

- Discovery and Evidence Generation. Data and research are critical resources needed to implement, evaluate, and enforce strategies to eliminate racial and ethnic health care inequities and advance health equity. Factors in this domain include advancing health equity research, historical and current health equity research funding, the research workforce, health equity research data, health equity research infrastructure, and moving health equity research from observation to interventions.

- Accountability. Goals to create an equitable health care system need to be achieved, and the system needs to remain responsive to the needs of all communities. Legislative oversight needs to ensure that laws have their intended impact and identify actions necessary to improve their performance. In addition, systematic standards and procedures should exist to enable periodic comprehensive reviews of interventions and their implementation.

The ultimate goal is to create an accountable system that achieves health care equity and promotes optimal health outcomes for all individuals regardless of their race, ethnicity, or other demographic factors influencing their ability to receive equitable health care and achieve optimal health. Individual elements of the framework and the role of the variables in each element are discussed in more detail throughout the first half of this report.

Recognizing the Current Legal and Political Environment

The legal and political environment has substantially changed since Unequal Treatment. Over the 2 decades since, Congress has enacted legislation aimed at mitigating the discriminatory impact of policies and laws and establishing new protections against discrimination. These laws have and could have had far-reaching positive effects toward the goals of eliminating health care inequities and achieving health equity. However, these reforms have significant structural limitations. For example, as noted earlier and discussed in detail in Chapter 4, the ACA implemented a comprehensive set of health reforms, including large expansions in health insurance coverage. However, its constitutionality and scope of implementation continue to face multiple legal and political challenges (Jost and Keith, 2020; Keith and McElvain, 2020; Musumeci and Rosenbaum, 2023). These developments have weakened some of its provisions that could help to address health care inequities.

Other recent decisions by the courts could perpetuate and even worsen racial and ethnic inequities in health care. Perhaps most notably for this report, a shifting political, social, legal, and cultural environment since the 2003 report underlies a decision by the Supreme Court in Students for Fair Admissions, Inc. v. President and Fellows of Harvard College.8 This decision could severely diminish the ability of federal government, using its constitutional powers under the 14th Amendment and educational institutions bound by Title VI of the 1964 Civil Rights Act, to remedy past and ongoing discrimination by using statistical evidence to fashion broad, race-conscious policies across health care and social welfare programs. Although the decision focuses specifically on undergraduate education, its implications potentially extend to university admissions programs more generally, although its limitations have yet to be tested. Furthermore, because it raises questions about the validity and reliability of government race and ethnicity data more generally, the Harvard ruling may reach more broadly into government and institutional efforts aimed at creating policies to mitigate past and ongoing inequities in a broad range of contexts, including policies aimed at overcoming the effects of racial and ethnic discrimination in health care and social services. These developments could affect the training of health care professionals to meet the needs of the diverse U.S. population and not just current research but future innovation and implementation to advance health and health care equity.

Additionally, the concept of structural racism is understood to include more than private prejudice and actions; it also is found within the laws and policies that order society (Bailey et al., 2021). However, political views differ

___________________

8 See https://www.supremecourt.gov/opinions/22pdf/20-1199_hgdj.pdf (accessed April 29, 2024).

on the existence of racism in the nation. The majority of the public does not believe that racism is an issue (Hurst, 2023). Also, less than half of the population recognize the existence of SDOH and their differential impact on health (Carman et al., 2019). These disparate views create barriers to efforts aiming to address racial and ethnic inequities in health care. Furthermore, helping the public to understand how implementing interventions that benefit minoritized populations actually benefit everyone may be challenging in the current legal and political environment.

STRUCTURE OF THE REPORT

Chapter 1 serves as an introduction, outlining the committee’s approach to the study task, presents historical context and an overview of the developments since Unequal Treatment, and introduces the committee’s conceptual framework that underpins its approach to the study task and serves as a unifying basis for its consensus recommendations. Chapter 2 discusses the larger society in which the health care system exists and how key societal external forces interact to contribute to health care inequities. Chapter 3 documents the evidence on racial and ethnic inequities measured by health care access, use, and quality and delves into the intersectionality of race and ethnicity with sexual and gender identity, disability, and immigrant status. Chapter 4 explores the evolution of U.S. health care and civil rights laws as they affect the complexities of health care inequities and discusses developments and shortcomings of some of the most significant policy and law interventions aimed at addressing inequities and advancing health equity. The chapter also discusses health care payment policies. Chapter 5 delves into health care service delivery, discussing topics such as the state of the workforce, different care settings, patient–clinician relationships, and innovative care delivery models. Chapter 6 discusses the central role communities play in creating equitable health care systems and highlights some of the most promising community-based interventions. Chapter 7 discusses discovery and evidence generation, covering evidence to support recommendations regarding the resources and infrastructure needed to advance health and health care equity research. Chapter 8 addresses accountability at various levels, emphasizing the need for a multifaceted approach involving federal lawmakers, agencies, professional entities, and researchers. Chapter 9 presents the report’s overarching conclusions and recommendations for reducing racial and ethnic inequities in health care and advancing health equity. The appendixes provide additional resources, including a glossary; previous relevant National Academies reports; and study committee, staff, and consultants’ biographical information.

REFERENCES

Allen, H., A. Swanson, J. Wang, and T. Gross. 2017. Early Medicaid expansion associated with reduced payday borrowing in California. Health Affairs 36(10):1769-1776.

Bailey, Z. D., J. M. Feldman, and M. T. Bassett. 2021. How structural racism works—racist policies as a root cause of U.S. Racial health inequities. New England Journal of Medicine 384(8):768-773.

Braveman, P. 2014. What are health disparities and health equity? We need to be clear. Public Health Reports 129(Suppl 2):5-8.

Caraballo, C., D. S. Massey, C. D. Ndumele, T. Haywood, S. Kaleem, T. King, Y. Liu, Y. Lu, M. Nunez-Smith, H. A. Taylor, K. E. Watson, J. Herrin, C. W. Yancy, J. S. Faust, and H. M. Krumholz. 2023. Excess mortality and years of potential life lost among the Black population in the US, 1999–2020. Journal of the American Medical Association 329(19):1662-1670.

Carman, K. G., S. Weilant, C. Miller, A. Chandra, and M. Tait. 2019. 2018 national survey of health attitudes: Description and top-line summary data. RAND. https://www.rand.org/content/dam/rand/pubs/research_reports/RR2800/RR2876/RAND_RR2876.pdf (accessed April 29, 2024).

CDC (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention). 2023a. U.S. Uninsured Rate Dropped 18% During Pandemic. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/pressroom/nchs_press_releases/2023/202305.htm (accessed April 29, 2024).

CDC. 2023b. Health and economic costs of chronic diseases. https://www.cdc.gov/chronicdisease/about/costs/index.htm (accessed April 29, 2024).

CDC. 2023c. CDC declares racism a public health threat. https://www.cdc.gov/minorityhealth/racism-disparities/expert-perspectives/threat/index.html (accessed April 29, 2024).

Hernández, B., S. Voll, N. A. Lewis, C. McCrory, A. White, L. Stirland, R. A. Kenny, R. Reilly, C. P. Hutton, L. E. Griffith, S. A. Kirkland, G. M. Terrera, and S. M. Hofer. 2021. Comparisons of disease cluster patterns, prevalence and health factors in the USA, Canada, England and Ireland. BMC Public Health 21(1):1674.

HHS (Department of Health and Human Services). 2024. Healthy People 2030. Building a healthier future for all. https://health.gov/healthy-people/priority-areas/health-equity-healthy-people-2030 (accessed April 29, 2024).

Hurst, K. 2023. Americans are divided on whether society overlooks racial discrimination or sees it where it doesn’t exist. Pew Research Center. https://www.pewresearch.org/short-reads/2023/08/25/americans-are-divided-on-whether-society-overlooks-racial-discrimination-or-sees-it-where-it-doesnt-exist/ (accessed April 29, 2024).

IOM (Institute of Medicine). 2003. Unequal treatment: Confronting racial and ethnic disparities in health care. Washington, DC: National Academies Press.

IOM. 2007. Hospital-Based Emergency Care: At the Breaking Point. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

IOM. 2009. America’s Uninsured Crisis: Consequences for Health and Health Care. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

Jost, T. S., and K. Keith. 2020. The ACA and the courts: Litigation’s effects on the law’s implementation and beyond: A review of the history of litigation over the Affordable Care Act and what this experience might mean for the future of health reform efforts in the United States. Health Affairs 39(3):479-486.

Keith, K., and J. McElvain. 2020. Health policy by litigation. The Journal of Law, Medicine & Ethics 48(3):443-449.

Kelen, G. D., R. Wolfe, G. D’Onofrio, A. M. Mills, D. Diercks, S. A. Stern, M. C. Wadman, and P. E. Sokolove. 2021. Emergency department crowding: The canary in the health care system. NEJM Catalyst Innovations in Care Delivery 2(5).

LaVeist, T. A., E. J. Pérez-Stable, P. Richard, A. Anderson, L. A. Isaac, R. Santiago, C. Okoh, N. Breen, T. Farhat, A. Assenov, and D. J. Gaskin. 2023. The economic burden of racial, ethnic, and educational health inequities in the US. Journal of the American Medical Association 329(19):1682-1692.

Liu, S. W., S. J. Singer, B. C. Sun, and C. A. Camargo Jr. 2011. A conceptual model for assessing quality of care for patients boarding in the emergency department: Structure–process–outcome. Academic Emergency Medicine 18(4):430-435

Mateo, C. M., K. Furtado, M. V. Plaisime, and D. R. Williams. 2024. The sociopolitical context of the unequal treatment report. The Urban Institute. https://www.urban.org/research/publication/sociopolitical-context-unequal-treatment-report (accessed April 29, 2024).

Mazurenko, O., C. P. Balio, R. Agarwal, A. E. Carroll, and N. Menachemi. 2018. The effects of Medicaid expansion under the ACA: A systematic review. Health Affairs 37(6):944-950.

Musumeci, M. and S. Rosenbaum. 2023. The ACA’s promise of free preventive health care faces ongoing legal challenges. The Commonwealth Fund. https://www.commonwealthfund.org/blog/2023/acas-promise-free-preventive-health-care-faces-ongoing-legal-challenges (accessed April 29, 2024).

McGhee, H. 2022. The sum of us: What racism costs everyone and how we can prosper together: London, UK: OneWorld Publications.

NASEM (National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine). 2019. Integrating social care into the delivery of health care: Moving upstream to improve the nation’s health. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

NASEM. 2020. Understanding the well-being of LGBTQI+ populations. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

NASEM. 2023. Federal policy to advance racial, ethnic, and tribal health equity. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

NASEM. 2024. Unequal treatment revisited: The current state of racial and ethnic disparities in health care: Proceedings of a workshop. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

Norton, M. I., and S. R. Sommers. 2011. Whites see racism as a zero-sum game that they are now losing. Perspectives on Psychological Science 6(3):215-218.

OECD (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development) 2023. Avoidable mortality (preventable and treatable). https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/sites/ec2b395b-en/index.html?itemId=/content/component/ec2b395b-en (accessed April 29, 2024).

Radley D. C., A. Shah, S. R. Collins, N R. Powe, L. C. Zephyrin. 2024. Advancing Racial Equity in U.S. Health Care The Commonwealth Fund 2024 State Health Disparities Report. The Commonwealth Fund. https://www.commonwealthfund.org/publications/fund-reports/2024/apr/advancing-racial-equity-us-health-care (accessed April 29, 2024).