Ending Unequal Treatment: Strategies to Achieve Equitable Health Care and Optimal Health for All (2024)

Chapter: Summary

Summary1

The way the U.S. health care system is organized, financed, delivered, and held accountable does not live up to its potential. Despite being the country that spends the most money on health care among all high-income countries, the United States has some of the worst population health outcomes and is far from achieving optimal health for all. Its health care system is broken and by its very design, delivers different outcomes for different populations, resulting in persistent and profound health care inequities. The inadequacy of the system disproportionately affects minoritized populations, with stark racial and ethnic inequities in life expectancy at birth, maternal and infant mortality, and many chronic diseases. The poorly performing system and negative repercussions of health inequities go far beyond each individual’s health and specific medical conditions to significant economic consequences for the entire nation. Persistent health and health care inequities lead to excessive health care expenditures and lost labor market productivity.

In 2003, the Institute of Medicine (IOM) issued, Unequal Treatment: Confronting Racial Bias and Ethnic Disparities in Health Care (IOM, 2003). That report, requested by Congress as a follow up to the 1985 Report on Black and Minority Health, assessed the extent of racial and ethnic differences in health care not otherwise attributable to known factors such as lack of insurance and access to care. In the 2 decades, progress has been made in generating awareness, conducting research that documents

___________________

1 This Summary does not include references. Citations for the discussion presented in the Summary appear in the subsequent report chapters, as does a detailed discussion of the evidence reviewed to support the committee’s conclusions and recommendations.

inequities, passing legislation and creating policies with positive intent, and narrowing gaps in some health care inequities for some populations some of the time. However, no sustained trend shows year after year that inequity gaps have narrowed across racially and ethnically minoritized groups. More work is needed to identify successful interventions for eliminating these inequities.

Addressing inequities and improving the health of individuals in the nation’s most disadvantaged communities improves the quality of care for everyone and advances population health. Poor outcomes for minoritized communities lead to poor outcomes for everyone. It is not a zero-sum game. Because inequitable policies and barriers make it difficult for minoritized populations to regularly access quality health care, they are often only able to access care when disease symptoms have advanced, and emergency department (ED) care is frequently their only option. This limited access to care can result in an overreliance on ED care, which is one of several contributors to ED overcrowding. That overcrowding and subsequent ED boarding leads to poor outcomes for all patients but disproportionately for minoritized patients. Similarly, barriers to accessing health insurance disproportionately impacts minoritized populations. Expansions facilitated by the Affordable Care Act (ACA) extended coverage to many uninsured and underinsured individuals and has been associated with improved access to the full range of health care services for all racial and ethnic groups. The Medicaid expansions have been of particular benefit in improving access to health care services and addressing health inequities for all people in participating states.

Inequities persist across all states. This is true even in those states that have been found to have better health system performance or where health outcomes have improved over time. Because much work remains to be done to eliminate health care inequities and advance optimal health for all in the United States, the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality and the National Institutes of Health requested that the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine conduct a study to review the major drivers of health care inequities, provide insight into successful and unsuccessful interventions, identify gaps in the evidence base, propose strategies to close those gaps, consider ways to scale and spread effective interventions to reduce racial and ethnic inequities in health care, and make recommendations to advance health equity.

THE COMMITTEE’S GUIDING FRAMEWORK

The statement of task to the committee specifies that “the committee will consider ways to scale and spread effective interventions to reduce racial and ethnic disparities in health care and make recommendations to

advance health equity.” It also directed the committee to “apply its expert judgment in order to develop recommendations with a focus on advancing health equity.” In its deliberations, the committee recognized that “health” and “health care” are different but inextricably linked. Health is a state of complete physical, mental, and social well-being and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity, while health care refers to the services provided to individuals, families, and communities to promote, maintain, or restore health across settings of care. Furthermore, the committee acknowledges that reductions in health disparities will require simultaneous improvements to health care as well as the many factors beyond health care that influence health, as shown in the committee’s conceptual framework. For the purpose of this report, the committee frequently uses “health care” and “health” together, because interventions to reduce racial and ethnic health care inequities also commonly advance health equity.

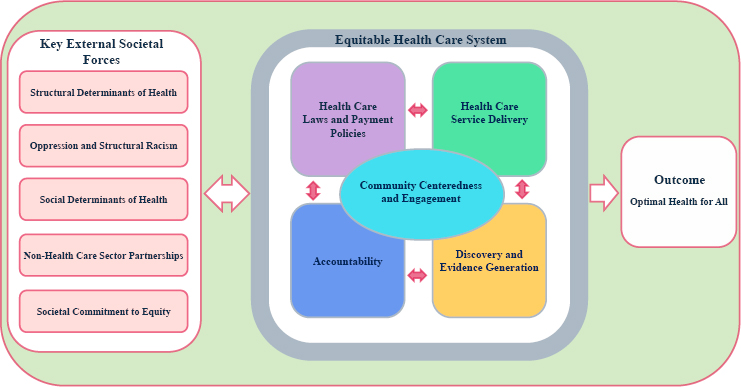

To guide its deliberations, the committee focused on the health care system broadly (including public health and community-partnered care) and developed a conceptual framework (see Figure S-1) to serve as a unifying basis for its approach to the report organization and recommendations for action. Because the health care system exists within the larger society, the conceptual framework highlights five key societal external forces, each representing a significant influence on equitable health care: structural

NOTE: The key external societal forces act individually, intersect with one another, and constantly interact with the domains in the health care system that are also constantly interacting with each other to significantly influence equitable health care.

determinants of health; oppression and structural racism; social determinants of health (SDOH); non–health care sector partnerships; and societal commitment to equity. These key external societal forces act individually, intersect with one another, and constantly interact with the domains in the health care system to pose significant influence on equitable health care.

- Structural determinants of health influence the distribution of health-related social needs (HRSNs) (social and economic needs that affect individuals’ ability to maintain their health and well-being) across different populations to either reinforce or mitigate health care inequities.

- Oppression and structural racism through historical and continued policies such as residential segregation, systemic oppression, or any form of bias, harm health through multiple pathways. These pathways result in adverse physical, social, behavioral, and economic impacts that directly and indirectly affect the health care system.

- Deprivation of resources and adverse SDOH (conditions in the environments in which people live, learn, work, play, worship, and age that affect a wide range of health, functioning, and quality-of-life outcomes and risks) disproportionately impact minoritized populations and manifest as unmet health-related social needs, which many health care systems are unable to address, further exacerbating inequities in care access, quality, and outcomes.

- The interest of partners outside the health care sector, such as social service agencies, can shape priorities and programs of health care systems, either negatively, by exacerbating inequities and widening inequity gaps, or positively, by unlocking long-term opportunities to advance health care equity.

- Societal commitment to identify and remove barriers and create equitable access to resources to achieve equal opportunities positively impacts health and health care; the lack thereof reinforces health and health care inequities.

Within the health care system, the committee identified four key intersecting domains—each with subdomains—that are critical mechanisms by which the system can reinforce or mitigate health care inequities. All four domains intersect within local communities where health care systems operate, and care delivery ultimately happens. As discussed throughout this report, community plays a vital role in health and health care; it is a critical determinant of health and can produce mechanisms central to advancing equity. Health care systems operate within communities and should be accountable to them and accountable for their health.

- Health Care Laws and Payment Policies. Policies to support equitable health care access, quality, and affordability serve as the foundation to remove persistent barriers and ensure that all individuals receive equitable health care services.

- Health Care Service Delivery. This domain focuses on the delivery of high-quality, culturally sensitive care to all and maximizing the health care system’s potential to eliminate racial and ethnic inequities in health and health care.

- Discovery and Evidence Generation. Data and research are critical resources needed to implement, evaluate, and enforce strategies to eliminate racial and ethnic health care inequities and advance health equity.

- Accountability. It is critical that goals to create an equitable health care system are achieved and that the system remains responsive to the needs of all communities. Systematic standards and procedures should exist to enable periodic comprehensive reviews of interventions and their implementation.

STUDY APPROACH

For the purposes of this study and the specific task, the committee did not extensively examine the evidence base related to achieving health equity broadly but focused more narrowly on racial and ethnic inequities in the health care system, especially in terms of care access, use, and quality. The committee, however, notes areas of overlap between advancing health care equity and advancing health equity. In addition, the terms used in this area of research have evolved over time and will continue to evolve as further insights are gained and society and demographics shift. In developing this consensus report, the committee made an intentional choice to use “inequitable treatment” rather than “unequal treatment.” Although they sound interchangeable, they are based on different concepts. In a health care treatment context, “equity” best captures that different individuals need different supports or treatments to achieve similar health outcomes. By contrast, “equality,” which is central to the foundational purpose of civil rights law and policy, could lead people to mistakenly believe that equal opportunity for optimal health is achieved only when everyone receives identical supports or treatment.

The committee also chose to use “inequities” rather than “disparities” except when citing a publication that explicitly measured disparities. It had several reasons for this update in language when discussing health care treatment. First, although many definitions exist for the term “health inequities,” the committee preferred to draw attention to those definitions that focus on these differences being avoidable, unfair, unjust, and affected

by social, economic, and environmental conditions. This intentional use of “inequities” highlights the committee’s emphasis on the role of SDOH and economic conditions in producing health and health care disparities. Second, the committee emphasized that the differences in health that this report discusses are not inevitable or acceptable. Moreover, this report uses “health care system” (activities related to the delivery of care across the continuum of care) to describe the U.S. health care system as a whole and individual health care systems and “health” when discussing outcomes. The committee recognizes that health and health care are very different concepts but inextricably linked.

A variety of sources informed the committee’s response to the study charge. The committee reviewed the literature relevant to the statement of task. To supplement the literature review, the committee commissioned three papers. To obtain insights on racial and ethnic inequities in health care and current and new approaches to alleviate racial and ethnic inequities, the committee conducted virtual public workshops. In January 2024, a “Proceedings”2 was released summarizing the presentations and discussions that took place at the three virtual workshops and highlighting individual participants’ suggestions to advance racial and ethnic health care equity. Additional input came from members of the public, who were given an opportunity to share their experiences, thoughts, and comments about racial and ethnic inequities in health care for the committee’s consideration through the project website during the study.

OVERARCHING CONCLUSIONS

Based on the materials and conclusions presented in the chapters of this report, the committee makes these overarching conclusions:

- The nation has made little progress in advancing health care equity. Racial and ethnic inequity remains a fundamental flaw of the U.S. health care system.

- Racial and ethnic health care inequities are driven by a complex interaction between health care and key external societal forces that serve as enablers or barriers to achieving equitable health care and optimal health. Achieving optimal health for all requires substantive changes in the larger societal forces that influence health and health care.

- Over the past 20 years the nation has experienced profound changes in laws and policies, with implications for health care

___________________

2 Available at https://nap.nationalacademies.org/catalog/27448/unequal-treatment-revisited-the-current-state-of-racial-and-ethnic.

- access, coverage, affordability, workforce, and the drivers of health care equity. Some changes in laws and policies have advanced health care equity significantly, while other changes have slowed down progress toward advancing this important goal.

- A diverse health and science workforce, representative of the communities that it serves, is essential to health care equity. The nation has made little progress addressing this goal. Recent court decisions concerning diversity, equity, and inclusion are likely to further limit progress in achieving a diverse workforce.

- Comprehensive and sustained efforts to improve health care across the continuum of care, from primary to quaternary care, including mental health care, have often been the most beneficial to minoritized populations facing the deepest inequities. In contrast, time-limited and/or incremental reforms often fall short of improving health care equity and may trigger unintended consequences that widen inequity gaps.

- Emerging approaches to achieving health care equity show promise and are poised for increased investment, implementation, and expansion so that progress is translated into long-term improvement in outcomes. This requires leadership and definitive action to implement sustainable policies and programs that maintain and continue to advance progress in an ever-evolving health care system.

- Continual research and evaluation are needed to measure and drive improvements in health and health care equity. Research findings need to be widely disseminated, and successful interventions need to be rapidly implemented and translated into practice and policy.

- Accountability is essential to advancing health and health care equity. Inadequate enforcement of current laws and policies that promote equitable health care to advance health equity has hindered progress. Enhancing systems of accountability throughout the health care system, with a focus on achieving equity and optimal health, are required.

GOALS AND RECOMMENDED IMPLEMENTATION ACTIONS

The committee’s recommended goals and implementation actions are not presented in order of priority or scale of impact. Instead, they are presented in a logical sequence of steps, recognizing that transformative change does not follow a linear process but is most often iterative, bidirectional, and circular. The recommendations are also presented to provide a narrative on what could be done immediately within the current legal and political environment, and how momentum can build from

one recommendation to the next. First (and continuously), accurate and timely data are needed to describe the health and health care inequities, to inform the development and implementation of effective and sustainable interventions. Next, health care systems need to be equipped with the information and capabilities to make sustainable change and iteratively measure progress in partnership with a research enterprise that continues to discover and rigorously evaluate promising new interventions that can be widely implemented. This ongoing progress needs to be supported by systems of accountability and enforcement. Finally, delivery and financing mechanisms need as their central goals to ensure access to equitable health care and to achieve optimal health for all.

Based on the overarching conclusions, the committee provides a range of recommended implementation actions. The goals of these recommendations are to:

- Generate accurate and timely data on inequities;

- Equip health care systems and expand effective and sustainable interventions;

- Invest in research and evidence generation to better identify and widely implement interventions that eliminate health care inequities;

- Ensure adequate resources to enforce existing laws and build systems of accountability that explicitly focus on eliminating health care inequities and advancing health equity and;

- Eliminate inequities in health care coverage, access, and quality.

Goal 1: Generate Accurate and Timely Data on Inequities

Only what is measured can get done, and timely and accurate data are essential for progress. However, the health care system is lax and uneven in gathering, correlating, interpreting, and using race and ethnicity data such that many decisions are not data driven or informed by data that could lead to applying and expanding successful interventions to eliminate inequities. In addition, efforts are underway nationwide to inhibit data collection and reporting by race and ethnicity. Without data, it will be impossible to know if health care inequities have been eliminated or health equity has been advanced. An intensive effort should be made to continue the collection, evaluation, and dissemination of health and health care equity data to ensure systemwide accountability for eliminating inequities in health care and advancing health equity. To achieve this goal, the committee recommends the following actions:

Implementation Actions:

1-1. The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) should fully implement Executive Order 13985 to build accountability for equity through data collection and reporting for the agencies and programs under HHS oversight.

- Revise the standard clinician and hospital billing forms, using Office of Management and Budget standards, to routinely capture patient race and ethnicity across all payers.

- Institute a process for routinely collecting race and ethnicity data on the health care workforce.

1-2. The Office of Management and Budget should set an administration-wide requirement for the routine collection of race, ethnicity, tribal affiliation, and language data by all agencies overseeing federal health care and research programs and should regularly monitor and report on agency compliance.

Goal 2: Equip Health Care Systems and Expand Effective and Sustainable Interventions

The health care system has failed to adopt at scale many of the known solutions for improving health care equity. The ACA set in motion long-term changes in how health care is organized and delivered, spurring greater emphasis on integrating health care with services aimed at addressing health-related social needs. However, structural limitations and legal challenges to the law have stalled broad implementation for many of its provisions. In addition, linguistically appropriate health care services do not meet the needs of the nation’s diverse patient population, partly because the health care workforce is not representative of that population. Emerging health care delivery models and multilevel interventions that involve the community show promise to advance equity and need to be scaled for broad implementation.

No widely agreed-upon systematic standards and procedures exist for acceptable performance measures to achieve equitable health care and optimal health for all, regardless of race and ethnicity and socioeconomic background. The variation in performance measures for health care equity impedes efforts to hold health care systems, organizations, and clinicians accountable for their performance in promoting equitable health care outcomes. Health equity should become an expectation of the entire health care delivery system and expectations of high-quality care should include equity as a core value at the organizational level. To ensure that this goal is achieved across the entire nation, federal leadership is essential to create consistency across the health care system. Just as health care professionals and clinical decision-making tools are subject to biases that contribute to health care inequities, so are the

algorithms and emerging technologies used in the application processes and acceptance of individuals, families, and communities into social programs.

Therefore, to achieve this goal, the committee recommends the following actions:

Implementation Actions:

2-1. Congress should increase funding for effective health care delivery programs shown to improve access and quality and reduce health care inequities.

2-2. The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services agencies overseeing federal health care programs should set clear, enforceable standards applicable to grantees that design and administer programs that will

- Ensure the provision of person-centered, whole person care that prioritizes prevention and health promotion rather than solely focusing on the treatment of advanced diseases.

- Foster strong clinician–patient relationships, shared decision-making, and improved communications.

- Ensure that measures of quality and performance reflect the sociocultural populations served rather than being generalized to the population as a whole.

- Emphasize the use of interprofessional teams that include community health workers and other multidisciplinary health care workers who possess the knowledge, competencies, and skills needed to tailor services to meet patients’ clinical and social needs.

- Promote equitable access to technologies that reduce barriers to effective care and are designed to eliminate systemic bias in clinical decision making.

2-3. The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services should expand the number of Section 1115 demonstrations designed to address adverse social determinants of health by combining clinical care with investments in health-related social needs as an element of care delivery. Health equity should be incorporated explicitly as a goal of program design, payment structure, and evaluation.

2-4. The Department of Health and Human Services should lead an agencywide effort to eliminate structural inequities in the design and application of standards, payment systems, and clinical diagnostic tools and algorithms that perpetuate health inequities and to ensure that tools and algorithms used to administer health and social service programs are accurate, unbiased, and reliable.

Goal 3: Invest in Research and Evidence Generation to Better Identify and Widely Implement Interventions that Eliminate Health Care Inequities

Important shifts in the funding and conduct of health equity research have occurred in the 20 years since Unequal Treatment. However, progress has been slow and incremental due to historically underfunded health equity research, exclusion of racially and ethnically minoritized groups from the research workforce, persistent limitations in data on race and ethnicity, and inadequate infrastructure and partnerships to rigorously conduct the necessary types and scale of health equity research and translate findings into policies and practice. Given the magnitude of the problem and years of life lost due to inequities, the paucity of resources devoted to studying successful “treatments” and implementation strategies for scaling up effective interventions is profound. Furthermore, the majority of studies in the health equity literature are observational, with fewer studies specifically testing multilevel and structural interventions. New approaches, including community-based research and studies in primary care settings, show promise to advance interventions to improve health and health care equity, but few implementation studies or comparative effectiveness studies have occurred to facilitate adoption of the most effective interventions. To achieve this goal, the committee recommends the following actions:

Implementation Actions:

3-1. National Institutes of Health and other federal and non-federal research funders should expand funding for research aimed at addressing health care inequities, structural racism, and health-related social needs, and exploring the various approaches, strategies, and policies needed to eliminate health care inequities. Advancing health equity will require major investment in health equity research project funding, workforce, data, and infrastructure.

- These expanded funding opportunities should invest in increasing the diversity of the pool of researchers in health and health care equity research and in the infrastructure needed to conduct community-based and community-engaged research, including addressing institutional barriers to community partnerships.

- These efforts should be coordinated by the National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities, as mandated by Congress.

3-2. The Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) and other relevant federal agencies should ensure that the programs they

administer are the focus of ongoing, rigorous evaluations of the impact of policies and interventions aimed at reducing inequities in health care and advancing health equity. HHS should ensure the findings from the research are effectively disseminated, implemented, and continuously evaluated for broader impact.

Goal 4: Ensure Adequate Resources to Enforce Existing Laws and Build Systems of Accountability that Explicitly Focus on Eliminating Health Care Inequities and Advancing Health Equity

Many current laws and regulations have been underused. The Office for Civil Rights (OCR) of the Department of Health and Human Services, as one example, is under resourced, limiting its efforts to enforce civil rights statutes and address the complaints it receives from individuals. A reported problem can only be addressed if the system ombudsman has the resources to do so. Several ACA provisions that could significantly advance racial and ethnic equity in health care are underenforced or unenforced. For example, Section 1557 of the ACA is a broad nondiscrimination policy that reinforces the long-standing protections prohibiting discrimination based on race, color, national origin, age, disability, or sex (including sexual orientation and gender identity). The goal was to bring all civil rights protections for health care into one section; it applies to any health care program or activity administered by an executive agency, which includes HHS, the Department of Defense, the Department of Veterans Affairs, and federal employee health benefit programs. OCR has implementation and enforcement authority under Section 1557. However, Section 1557 remains largely a promise.

The ACA amended the Internal Revenue Code to expand the duties of hospitals as a condition of tax exemption. However, the 2010 amendments did not explicitly require hospitals to tie their community benefit expenditures to their community health needs assessments, establish minimum expenditures, or end the hospital practice of allocating these expenditures to their Medicaid shortfall. The Internal Revenue Service enforcement of the 2010 amendments has been limited. Therefore, to achieve this goal, the committee recommends the following actions:

Implementation Actions:

4-1. Congress and the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) should ensure adequate resources are available to enable the HHS Office for Civil Rights to enforce Section 1557 of the Affordable Care Act (42 U.S.C. § 1811), which prohibits discrimination on the basis of race, color, national origin, age, disability, or sex (including sexual orientation and gender

identity), in covered health programs or activities. As part of this enforcement effort,

- OCR should revise the Section 1557 complaint and investigation process to improve accessibility, usability, and transparency. OCR should also increase technical assistance resources essential to supporting the complaint process available to individuals who believe that they have experienced one or more prohibited forms of discrimination in care.

- OCR should rapidly complete and publish the results of its investigations in order to promote confidence in system accountability, greater clarity regarding the types of policies and practices that constitute discrimination, and the actions taken when discrimination is found.

4-2. The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) Secretary should ensure that all health care programs administered or overseen by HHS include funding for costs associated with language access compliance, and that language access standards are enforced.

4-3. The Internal Revenue Service and Treasury Department should create clear enforceable standards aimed at maximizing hospital investment in community health improvement.

4-4. The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services should establish and enforce provider network standards across all federal programs in a manner that ensures equitable access to providers.

Goal 5: Eliminate Inequities in Health Care Coverage, Access, and Quality

Progress toward achieving all of these goals and recommendations depends on a foundation of equity for the health care system, which has structural inequities in its very design. The United States is the only industrialized nation without universal health insurance coverage and with substantial disparities in payments for services between payers (commercial, Medicaid, and Medicare). These structural inequities result in unequal access to health care services. This means that the system is inherently separate and unequal. These inequities affect all patients because they threaten the fiscal viability of the entire system, lead to the loss of years of avoidable productive life and of economic productivity, and decrease health care affordability for everyone, including populations that are not

publicly insured. These inequities disproportionately impact minoritized populations but addressing them benefits everyone. The ACA expanded health care coverage to millions of low-income individuals and set in motion long-term changes in how health care is organized and delivered, spurring greater emphasis on integrating it with services aimed at addressing HRSNs. However, structural limitations, lack of enforcement, and Supreme Court rulings on ACA provisions have stalled broad implementation and even sometimes reversed the trajectories intended. Health insurance enrollment and affordability barriers also continue to disproportionately affect minoritized groups.

Medicaid disproportionately serves children and nonelderly adults from racially and ethnically minoritized populations, but all enrollees (the majority of whom identify as non-Hispanic White) have more limited access to needed medical care than those covered by Medicare or private insurance. The variation in health care provider (HCP) payment rates across public and private third-party payers is associated with variation in HCP participation, with low participation especially prevalent for Medicaid. Moreover, social and economic policies that have implications for health care equity vary across states, which means that racially and ethnically minoritized populations in different states do not equitably benefit from such reforms. In particular, the Indian Health Service continues to be underfunded despite evidence of extensive unmet need and service capacity shortages and the long-standing treaty-based obligations on which its financing rests. The evidence suggests that inadequate funding has perpetuated inequities.

Implementation Actions:

5-1. Congress should establish a pathway to affordable comprehensive health insurance for everyone.

5-2. Congress should establish a pathway to the adoption and implementation of Medicaid payment policies that ensure equality with Medicare.

5-3. In order to meet its treaty obligations, Congress should fully fund the Indian Health Service on a mandatory spending basis to improve access to care for Indigenous populations.

5-4. Congress and the administration should work to achieve an equitable and permanent solution to the inadequate Medicaid funding for U.S. territories to address the disparities in fiscal support for their health care services.

5-5. The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services should use its demonstration powers to incentivize states to test changes in scope of practice, provider payments and other mechanisms to expand access to health care providers for underserved populations.

Eliminating health care inequities and advancing health equity are achievable and feasible goals. Many of the tools needed to reach these goals are already available and need to be fully used. With concerted national efforts and adequate resources, the health care system can be transformed to deliver high-quality, equitable care to all and contribute to the larger societal goal of achieving optimal health for all. We are all in this together.

This page intentionally left blank.