Potential Environmental Effects of Nuclear War (2025)

Chapter: 7 Societal and Economic Impacts

7

Societal and Economic Impacts

7.1 INTRODUCTION

This report explores the environmental, societal, and economic effects that would occur in the weeks to decades following a nuclear war. The report begins by considering a plausible set of weapons employment scenarios (Chapter 2) and then traces mechanistic pathways that connect the initial weapon exchanges to the fire dynamics and emissions resulting from nuclear detonations (Chapter 3); the fate and transport of these emissions once aerosolized (Chapter 4); the subsequent effects on the climate and physical Earth system (Chapter 5); and the eventual impacts on nature and ecosystems (Chapter 6). The current chapter extends these pathways to their potential societal and economic implications, focusing on three broad categories of impacts felt by people and society: to ecosystem services, to human health, and to broader community resilience.

Precise quantification of these potential impacts is hampered by substantial limitations in our current understanding of, and ability to model, the immediate environmental impacts of nuclear exchanges as well as the dynamics of coupled human–natural systems that would transform those environmental impacts into harms to people, communities, and the economy. The complexity of the analytical challenge is daunting. There is a wide range of potential outcomes that could plausibly fit into the scenarios developed in this report, and each of those conflicts would produce a distinct set of environmental effects, depending on its magnitude, timing, geographic location, and other factors. Different regions may feel impacts more or less acutely, but as discussed later in this chapter, global teleconnections mean that even limited or regional scenarios may give rise to significant impacts worldwide.

The impacts described in this chapter thus do not map directly to any particular one of the four scenarios developed for the report. It is still useful, however, to acknowledge that, collectively, they represent a qualitatively distinct scale of conflict: a large-scale, strategic exchange between major nuclear powers, involving 2,000 warheads; a moderate-scale strategic exchange of 400 warheads; a small-scale exchange between regional nuclear powers, involving 150 warheads; and a very small-scale scenario with a single detonation. The societal consequences of nuclear war can similarly be discussed in terms of qualitatively different scales of impacts (see the different pathways of disruption outlined in Section 7.1.1). The societal consequences of these environmental effects would be mediated by a vast array of dynamic interactions and feedbacks between nature and society, many of which are poorly characterized or understood. In plainer terms, there is a fundamental lack of data, process understanding, and modeling capabilities that prevents researchers and analysts from quantitatively linking specific nuclear war scenarios to precise societal outcomes. Therefore, this chapter uses a mixed-methods approach of available quantitative and qualitative scientific data and information to assess these potential impacts and offers recommendations to address key limitations and opportunities to advance knowledge and capabilities in this critical domain.

This report seeks to integrate a contemporary understanding of the evolution of nuclear weapon technologies, nuclear war planning and strategies, and the expansion of geopolitical nuclear actors with a stronger understanding of how increased global interconnectedness may produce pathways to harm beyond a nuclear winter scenario as described in existing literature. It is important to note, however, that the ultimate impact of a nuclear detonation in a given setting is strongly determined by the magnitude of the shock, and the resilience and general health status and well-being of the impacted communities. Furthermore, while interdependencies may propagate risks beyond the immediate zone of impact, advancements in systems-driven solutions can also result in resilience, buffering of shocks, and opportunities, including rapid deployment of resources, for interventions to mitigate risks.

BOX 7-1

Key Terms

Aquaculture: Farming of aquatic organisms such as fish, crustaceans, mollusks, and aquatic plants, involving their cultivation in natural or controlled marine or freshwater environments.

Climate–carbon cycle: Interconnected processes and feedbacks between Earth’s climate system and the global carbon cycle. It involves the exchange of carbon dioxide (CO2) between the atmosphere, oceans, terrestrial biosphere, and geological reservoirs, and how these fluxes are influenced by and influence Earth’s climate.

Displacement: Forced removal or movement of people from their homes, communities, or regions, typically due to factors such as armed conflict, natural disasters, development projects, or other threats to their safety and wellbeing.

Ecosystem Services: Direct and indirect benefits that ecosystems provide to people and society. These services can include the provisioning of resources such as food, water, timber, and fiber; regulation of environmental quality through water and air purification, flood control, and climate regulation; and cultural and spiritual benefits.

Exposure: State of being subjected to something potentially harmful or hazardous. In environmental and health contexts, it typically refers to contact with pollutants, contaminants, radiation, or other agents that may pose health risks.

Fallout: Residual radioactive particles and materials that are deposited on the ground and in the environment after a nuclear explosion or accident. It can consist of various radioactive isotopes and can contaminate air, water, surfaces, and food sources, posing radiation exposure risks.

Feedbacks: Interplay between environmental changes and human systems, where impacts on societies can amplify (positive feedback) or mitigate (negative feedback) the initial changes. For example, climate-related disasters can disrupt food production, leading to poverty, conflict, and further environmental degradation—a positive feedback exacerbating vulnerability. Conversely, effective governance and behavioral changes could reduce emissions, slowing climate change impacts—a negative feedback. These complex human–environment interactions can reinforce or counteract climate and environmental pressures.

Global South: Regions and countries in lower- and middle-income countries, primarily located in Africa, Latin America, and parts of Asia.

Governance: Processes, systems, and institutions through which authority is exercised and decisions are made and implemented within a given entity, such as a government, organization, or community. It encompasses aspects such as policymaking, accountability, transparency, and the ways in which various stakeholders participate in decision-making processes.

Human Health: Holistic state of physical, mental, and societal well-being, not merely the absence of disease or infirmity. It encompasses various aspects, including physical health, mental health, emotional and psychological well-being, social relationships, and overall life satisfaction.

Migration: Movement of people from one place to another, either within a country (internal migration) or across international borders (international migration). It can be voluntary or forced and can occur for various reasons, such as economic opportunities, conflict, environmental factors, or family reunification.

Morbidity: State of being ill, diseased, or unhealthy. It is a measure of the incidence or prevalence of illness or disease within a specific population over a given period. Morbidity rates are used to assess the burden and patterns of health conditions. Morbidity associated with a nuclear detonation can occur both acutely or over time and include adverse physical and mental health effects. Acute morbidity can result in chronic adverse health conditions, potentially exacerbating existing co-morbidities and organ system functioning in vulnerable populations. Adverse mental health effects can exist for a prolonged period and are often underdiagnosed.

Mortality: Measure of the number of deaths in a particular population, scaled to the size of that population, over a specified period. Mortality rates are used to quantify the impact of different causes of death and assess overall population health. Mortality in the aftermath of a disaster can be classified as direct, indirect, and attributable. This categorization can assist in managing and predictive modeling of a nuclear event (Stoto et al., 2021).

Multisectoral Dynamics: Interconnections and interactions between different sectors or domains, such as the economy, environment, society, and governance. It recognizes that changes or decisions in one sector can have ripple effects and implications for other sectors, and that addressing complex challenges often requires a holistic, cross-sectoral approach.

Nonlinearity: Situations in which seemingly small environmental or societal shifts can trigger disproportionately large consequences due to complex interdependencies and tipping points. For instance, environmental changes could eventually render cities uninhabitable, leading to widespread displacement, economic disruptions, and potential social unrest in a nonlinear manner. Similarly, crop failures from drought could abruptly undermine food security, causing cascading health and political crises if critical thresholds are crossed.

Risk: In the context of this chapter, the potential for adverse impacts on coupled human-environment systems due to existing and emerging environmental health threats. It accounts for the interactions between physical impacts and existing societal vulnerabilities, such as economic disruptions or the susceptibility of agricultural livelihoods to drought. Risk is shaped by underlying societal factors such as poverty, governance capacity, and adaptive preparedness.

Resilience: Ability of a community or society to withstand, adapt to, and recover from adverse events or disruptions. It involves factors such as strong social networks, effective governance, and the capacity to learn and transform in response to challenges.

Social Capital: Networks, relationships, and shared norms, values, and understandings that facilitate cooperation and collective action within and among groups. It encompasses elements such as trust, reciprocity, and social cohesion, which can contribute to the well-being and resilience of individuals and communities.

Teleconnection: Term used in meteorology and climatology to describe the linkage or correlation between weather patterns or climate anomalies in geographically distant regions. The concept can also be applied to societal dynamics. In this context, societal teleconnections refer to the ways in which events, processes, or changes in one part of the world can have ripple effects or consequences for societies and communities in distant or seemingly unrelated parts of the world, for example, through globalization and social and economic interconnectedness.

Trophic Level: Position that an organism occupies in a food chain or food web, based on its feeding relationships. The trophic levels include producers (plants), primary consumers (herbivores), secondary consumers (carnivores that eat herbivores), and tertiary consumers (carnivores that eat other carnivores). Higher trophic levels represent organisms at the top of the food chain.

Vulnerability: Measure of the degree to which a system, population, or individual is susceptible to and unable to cope with the adverse effects of a hazard or stress. It is determined by factors such as exposure, sensitivity, and adaptive capacity. In the context of climate change, vulnerability encompasses the potential for adverse impacts on human or natural systems due to their degree of susceptibility and ability to adapt.

7.1.1 Drivers of Societal Effects Stemming from a Nuclear War

This chapter considers three broad categories of human impacts stemming from these environmental effects, including the impacts on essential ecosystem services such as agriculture, resource

provision, and environmental quality; the direct and indirect effects on human health and well-being; and the broader impact on community resilience.

Detonations of large magnitude may disrupt (or destroy) societies through pathways that involve global-scale climate effects. The atmospheric changes discussed in previous chapters suggest potentially widespread impacts on agriculture, water resources, and other factors that are critical for human livability in the months to years following a nuclear war. Smaller regional detonations, although not as likely to cause global-scale changes in climate, could still produce impacts on environmental quality at local and regional scales. Air pollution and environmental contamination from nuclear detonation-induced fires would have significant impacts on ecosystem services, specifically agriculture, as well as human health and economic activity. In addition, even a limited weapons exchange might still cause ripple effects throughout globally connected systems, such as trade and financial networks.

To summarize, the potential societal impacts explored in this chapter stem from two general types of disruption pathways:

- Global climatic and environmental disruption resulting from large-scale nuclear exchanges between major powers, which would directly affect people and communities worldwide.

- Local and regional-scale environmental degradation resulting from smaller-scale nuclear exchanges, which would directly affect people and communities in specific geographic areas and possibly lead to more extended impacts mediated by societal teleconnections.

The ultimate human and societal impacts resulting from either pathway would be determined by the magnitude of the shock and the resilience and health status of the affected communities.

The chapter explores the current state of scientific knowledge of the mechanisms by which the environmental impacts of nuclear wars lead to societal consequences. The unique risks posed by different geographic scales of conflict, radiological release, and resulting climate/contamination effects represent key uncertainties in precisely quantifying those societal outcomes.

7.1.2 Societal Interconnections

The potential societal impacts explored in Section 7.1.1 stemming directly from a nuclear war would be amplified and further cascade through the interconnected global system. Today’s advances in technology, communication, and trade have created intricate transnational networks that enable rapid propagation of impacts across regions. This interconnectedness leads to societal teleconnections, analogous to natural teleconnections in Earth systems, whereby a disruption in one region or sector generates cascading impacts, through societal influencing factors, that are not necessarily colocated with the initial disturbance (Viña and Liu, 2022). For instance, agricultural damage in a conflict region could reverberate through trade networks to produce global food supply disruptions. Harm to infrastructure such as ports could ripple through supply chains leading to unemployment spikes in dependent economies (Cottrell et al., 2019).

These linkages create complexity and nonlinear propagation of secondary, tertiary, and higher-order impacts over weeks to decades following the initial nuclear exchange. Breakdowns in one critical sector such as energy may disable other systems including water, food, health, and communications in unpredictable ways. This global interconnectedness also creates complexity and nonlinear behaviors as impacts propagate through societal systems. This complexity arises from the myriad of feedbacks between human and natural systems, which current models struggle to represent fully.

Individual and institutional responses to the crisis can further compound uncertainties through uncoordinated policies, unrest, hoarding, panic behaviors or instability. Ultimately, human responses to actual and perceived risks would modulate outcomes significantly following a nuclear war. Individual and collective actions taken in response to resource scarcity and instability can either worsen impacts through hoarding and unrest or enhance resilience through cooperation. Incorporating these human dimensions is

critical for holistically understanding potential risks, as societal reactions themselves become drivers shaping the progression of secondary impacts over time (Miller et al., 2024).

Holistically assessing the risks requires recognizing that potential impacts arise not just from the direct effects of nuclear war but also from societal responses to the crisis. This human feedback loop modulating risks remains a key factor not fully captured in current analytical capabilities.

The societal impacts of a nuclear exchange are interconnected and can—depending on the magnitude of the exchange and its geographic context—produce local, regional, and/or global adverse effects that occur in the immediate aftermath and over longer periods. Globalization has increased the interconnectedness of the world creating complex systems with many dependencies and links. This interconnectedness is influenced by a community’s resilience as measured by its social capital domains (NASEM, 2019). For example, communities with resilient infrastructure and financial resources can mitigate disruption in the infrastructure and supply chain of critical health services and food and can accelerate post-event response actions and recovery (Davis et al., 2021). Likewise, robust social cohesion, effective governance, and proactive preparedness actions allow an impacted community to share its resources more efficiently and effectively. This interconnectivity has also enabled economic growth and expansion as well as cross-cultural interactions across the globe.

SOURCE: DOE, n.d.

BOX 7-2

How Shocks May Affect an Interconnected World

The Hiroshima and Nagasaki bombings marked the end of the truly catastrophic World War II and the start of a significant period of economic, political, and social integration on a global scale. Post-World War II, key international institutions such as the United Nations in 1945, the International Monetary Fund, and the World Bank in 1944 were created to promote international cooperation, economic stability, and development. The General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT) was created in 1947 and later evolved into the World Trade Organization (Crowley, 2003). GATT enabled an increase in international trade by implementing policies that reduced or eliminated trade barriers. These events contributed to a rapid increase in globalization.

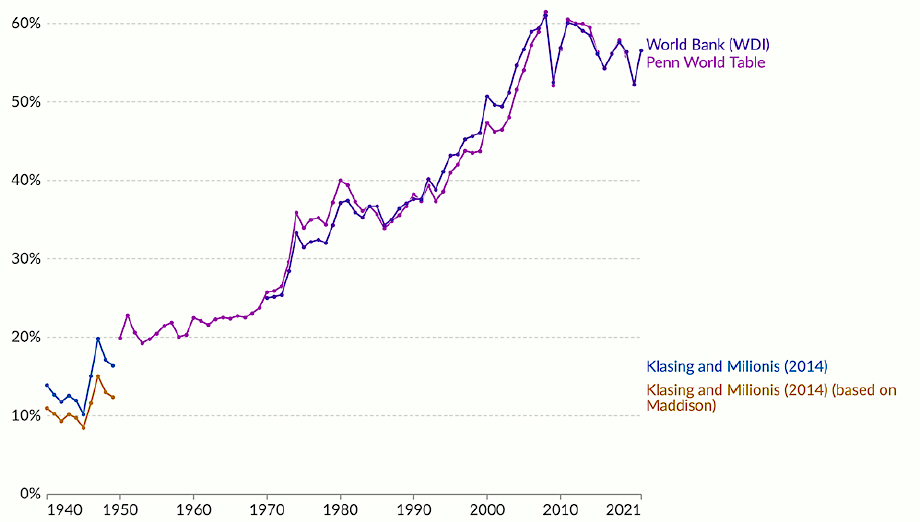

Globalization has undergone several dynamic phases since 1945, characterized by periods of rapid integration and periods of slowdown or partial reversal. The current landscape suggests a complex interconnected world, influenced by technological advancements, political decisions, and global economic shifts, a very different landscape than the conditions in 1945 (Figure 7-2). Increased trade, investment, and information flows in a globalized economy have created many opportunities for export expansion and diversification. The distribution of gains of globalization has been uneven worldwide which has led to an increased vulnerability (i.e., risk of being negatively affected by shocks). These shocks could be caused by nature (e.g., droughts), economic shocks (e.g., trade policies), health pandemics (e.g., COVID-19) or armed conflicts (e.g., Russia-Ukraine war). However, it is important to note that the interconnectedness resulting from advances in globalization can also bolster access to resources beyond the directly impacted community and mitigate disruption of the supply chain. Furthermore, the resilience and general health status and well-being of indirectly impacted communities are important determinants of ultimate risks and adverse effects.

Figure 7-3 shows the world food price index for the 1961–2024 period and the correlation with some major global events. In 1973, an oil crisis was caused by a total embargo implemented by the Organization of Arab Petroleum Exporting Countries against countries that had supported Israel during the Fourth Arab-Israeli War.

Another oil crisis was caused by the Iranian Revolution in 1979 and the drop in oil production. In both cases, the oil crisis caused an increase in global food prices. In the early 1980’s the Latin American debt crisis also influenced global food prices. Likewise, in 1997 after Thailand devaluated its currency relative to the U.S. dollar, a financial crisis spread across East Asia, disrupting economies in the region and leading to spillover effects in Latin America and Europe. This event also affected food security and global food prices. The world food price crisis between 2007 and 2008 was caused by a mix of factors, including severe droughts in grain-producing regions and increasing costs of fertilizers, food transportation, and other industrial agriculture inputs due to increases in oil prices. Another big spike in food prices occurred between 2011 and 2012, also due to severe droughts in parts of Ukraine and Russia, affecting wheat production. This was followed by a La Niña weather pattern that affected corn and soybean production in many countries. The COVID-19 pandemic created an increase in food prices around the world where low-income households were most affected. Supply chain disruptions and increased consumer demand for food raised food prices worldwide between 2020 and 2021. These conditions were worsened by the 2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine. The Russia-Ukraine war disrupted almost a third of the world’s wheat market. The 2023 escalation of the Israeli-Hamas conflict may have caused an increase in energy and fertilizer prices with corollary impacts on world food prices. Shipment bottlenecks and attacks on freight carriers in the Red Sea, a busy trade route for fertilizers, can cause fertilizer and oil price spikes (Bhattacharya, 2023; Rice and Vos, 2024).

SOURCE: © FAO 2024. World Food Situation: FAO Food Price Index - Historical Dataset of Nominal and real indices from 1961 onwards (annual). https://www.fao.org/worldfoodsituation/foodpricesindex/en/. Accessed April 11, 2025.

7.1.3 Challenges and Improvements in Modeling Environmental, Societal, and Economic Impacts of Nuclear War

Existing models used to assess environmental and societal and economic impacts, particularly those developed for climate change effects, are not well suited for evaluating the consequences of sudden

shocks such as nuclear war. Climate impact models, including partial and general equilibrium economic models, primarily focus on gradual changes over extended time horizons. However, sudden shocks introduce immediate and complex disruptions, that these models cannot capture. To better inform policy and decision making, significant improvements in modeling approaches are needed.

A key limitation of current economic models is their assumption of equilibrium or near-equilibrium conditions. Climate models often rely on long-term projections, whereas economies and societies are assumed to adapt incrementally. However, shocks such as a nuclear event, can lead to a state of short-term disequilibria, such as abrupt disruptions in trade, labor markets, infrastructure, and food production. These shocks require dynamic modeling approaches that can simulate rapid shifts in supply and demand, forced migration, and structural collapses in key sectors such as agriculture.

While climate models typically account for slow-moving variables such as temperature rise and sea-level change over time, nuclear war scenarios require modeling of cascading effects from immediate impacts, such as infrastructure loss leading to food shortages and economic collapse in terms of both time and geographic spread. Sudden shocks, such as a nuclear war, introduce geopolitical uncertainty, which traditional climate impact models and integrated assessment models do not incorporate effectively. The need for models or the integration of models that can capture both direct and indirect ripple effects through society and economies is crucial for policy planning and crisis management.

Integrating multiple large-scale, multidisciplinary and computationally demanding models requires not only significant financial and technical investment but also collaboration across different disciplines. This involves developing methods that allow these models to communicate effectively, such as standardized data formats and interoperability frameworks. Current software tools may not support such integration, thus new systems are needed to enable efficient ensemble modeling. Another challenge in assessing the impacts of nuclear war is the lack of reliable data needed for scenario-based, forward-looking models and integrated assessments. Nuclear war involves sudden, complex disruptions for which comprehensive data are scarce, which limits the ability of existing models to capture the scale and magnitude of impacts. Significant investment is needed in data collection, including experimental and scientific data, as well as gathering relevant information from past events and simulations. This will help integrated assessments to be better equipped to handle the complexities of nuclear war scenarios. Addressing these challenges is essential to ensure that improved model frameworks can provide comprehensive analysis of the societal and economic consequences of a hypothetical nuclear war.

Enhancement of models to assess impacts of a nuclear war will require a transdisciplinary approach and interdisciplinary collaboration. Existing economic impact analysis, integrated assessment models, global and national general or partial equilibrium models and systems dynamics approaches need to be improved to incorporate mechanisms that better represent the speed, scale, and interconnected nature of nuclear war-induced disruptions so that these models and approaches can provide more-accurate and -policy-relevant insights to improve preparedness and response strategies. Investing in improved modeling capabilities is essential for addressing critical policy actions to deal with food security in conflict-affected regions, economic resilience to sudden shocks, and long-term recovery pathways.

7.2 IMPACTS ON ECOSYSTEM SERVICES

7.2.1 State of Knowledge

This section reviews the current scientific understanding of the potential impacts, on timescales of weeks to decades, of nuclear war on key ecosystem services that sustain human populations and economic activity. The committee reviewed three broad categories of ecosystem services that are most relevant for analysis within the study time frame: agriculture and food production; natural resource provision; and environmental quality pertaining to air, water, and soil.

7.2.1.1 Agriculture and Food Production

The consequences of a nuclear war for agriculture and food production can be extensive and have direct and indirect impacts on food production, distribution, and consumption systems, with far-reaching consequences for immediate and long-term food security. A nuclear war can result in widespread cooling and precipitation decreases caused by soot and debris injected into the atmosphere after nuclear weapon detonation. As described in Chapter 6 (Ecosystem Impacts), this debris can block solar radiation, reducing sunlight available for photosynthesis, and cause temperature drops and changes in weather patterns that disturb the timing of crop planting, growth, and harvesting. These impacts would lead to lower crop yields, reduced livestock feed availability, and low livestock yields. Temperature changes and season length variations further limit agricultural productivity by disturbing plant growth cycles and animal breeding patterns.

Previous studies have suggested that a smaller nuclear exchange could result in a sudden decline in global mean temperature and precipitation by up to 1.8ºC and 8%, respectively, with the rapidity of the cooling effect potentially being more harmful that its magnitude. Jägermeyr et al. (2020) use this scenario to evaluate the impacts on the global food system. Their results suggest that global production losses of major production systems range between 3% and 16% on average. However, the results also suggest a high variability across the different regions (see Table 7-1). Several studies agree that the impact of a nuclear war on agriculture varies based on the locations of nuclear exchanges and magnitude of the detonations, where different regions could experience different extents of damage based on factors such as intensity of attacks, prevailing weather patterns, and other conditions such as whether the exchange is in the Northern Hemisphere main cropping season. Results suggest that the major impacts may occur on temperate regions above 30ºN latitude which includes the United States, China, and Europe. In general, areas closer to the Equator (southern latitudes) might experience comparably milder impacts owing to their more stable annual climate, although no region would remain entirely immune to the far-reaching consequences of a nuclear war. However, global trade analyses suggest that multiyear losses on major producing regions would constrain food availability, despite domestic reserves, and propagate to the Global South where the larger impacts will be on countries with high poverty and food insecurity rates (FAO et al., 2024; Glauber and Laborde Debucquet, 2023; Hochman et al., 2022; Jägermeyr et al., 2020; Puma et al., 2015; WFP and FAO, 2024).

This can be accentuated by the disruption or destruction of infrastructure, transportation systems, and supply chains which would hinder the movement of agricultural products, leading to challenges in accessing input and output markets and distributing food. These conditions can create price fluctuations due to supply-and-demand dynamics, and the limited availability of essential agricultural inputs such as fertilizers, seeds, and labor, which can become limited or entirely inaccessible due to the destruction of production facilities and transportation routes, or policies implemented in certain countries. This scarcity can further hamper crop production and food security. Figure 7-4 shows how fragile and vulnerable the global food system is to self-propagating disruptions (i.e., multiplier effect) due to the high level of interconnectedness and the amount of food that is traded across countries and continents (Puma et al., 2015).

The social and economic upheaval of nuclear war can cause large-scale migration and displacement of populations. People may be forced to leave their homes and agricultural lands due to immediate danger from the conflicts and subsequent breakdown of societal structures. This situation could lead to labor shortages affecting planting, harvesting, and other critical agricultural activities.

The environmental aftermath of nuclear war could lead to loss of biodiversity in agricultural ecosystems. Radioactive fallout, pollution, and habitat destruction could contribute to the decline of various plant and animal species, disrupting ecosystem services crucial for maintaining soil fertility, pest control, and ecosystem health. This could further challenge agricultural systems to recover and adapt to the new post-war conditions.

SOURCE: Puma et al., 2015.

7.2.1.2 Natural Resources Provision

Each of the studies that have investigated changes in the lowest marine trophic level (i.e., plankton) following nuclear war have been conducted with Earth system models (see Section 6.4 and associated references). These models were designed to simulate the coupled climate–carbon cycle, and as such, do not include representation of marine organisms at higher trophic levels, such as krill or fish. To circumvent this, Scherrer et al. (2020) used output from several simulations of an Earth system model to drive an offline fisheries model and quantify the response of marine wild-capture fisheries to nuclear war. They demonstrated that in the present-day ocean, characterized by overfishing, a nuclear war would have

devastating impacts on marine wild-capture fishery productivity, with a 30% decline in catch after a global conflict (injecting 150 Tg of soot; Scherrer et al., 2020). If a conflict were to occur in an overfished state, the increased demand on marine fisheries productivity would eventually send fisheries productivity into a decline of 70%. They note that effective prewar fisheries management could offset this decline and buffer the agricultural losses on land (Scherrer et al., 2020). Using a similar approach, Xia et al. (2022) estimated that after regional or global nuclear war that injects more than 5 Tg of soot, aquatic food production would not be able to compensate for reduced crop output, leading to large calorie deficits for global society.

Accessible freshwater within lakes and rivers represents less than one-tenth of one percent of all water on Earth. Nevertheless, estimates suggest that freshwater fisheries produce approximately 19% of globally captured fishes each year (Allison and Mills, 2018). When combined with freshwater aquaculture production, which represents approximately 68% of global aquaculture, freshwater fishes represent over 40% of annual global fish consumption. Beyond freshwater systems, discharge and nutrients from rivers also support fisheries production in estuaries and marine systems. In combination, a recent review suggested that the species comprising 77% of the total global fisheries catch are dependent on freshwater systems for at least some part of their lives (Broadley et al., 2022). Consequently, the disruptions of hydrologic processes and degradation of freshwater ecosystems caused by nuclear detonation and described in previous chapters have the potential to significantly impact global fisheries food production.

BOX 7-3

Impacts on Ecosystem Services

Several historical disasters illustrate the potential for large-scale damage to agriculture, natural resources, and environmental quality—key ecosystem services that sustain human populations.

Pakistan’s catastrophic flooding in 2022 damaged agricultural lands across 4 million hectares directly inundated by floodwaters (Nanditha et al., 2023). Early estimates suggest that the floods may have destroyed over 40% of food crops including staple commodities and 75% of fruit and vegetable crops (Ahmed and Farooq, 2022; Center for Disaster Philanthropy, 2023; Qamer et al., 2023). With agriculture central to Pakistan’s economy, the agricultural devastation threatens protracted food insecurity and economic disruption through the degradation of essential ecosystem services.

The Australian bushfires of 2019–2020 directly burned over 46 million acres of forests, farmland, and grazing lands across multiple states (Jalaludin et al., 2020; WWF-Australia, n.d.). The destruction reduced national cattle stocks by over 300,000 head and damaged fruit production. Modeling suggests that the fires may have wiped out up to 70% of timber supplies in some impacted regions (Bowman et al., 2021; Peel, 2020). By disrupting agriculture and destroying crop, timber, and livestock resources, the bushfires severely degraded natural capital providing essential ecosystem services.

The 2010 Haiti earthquake damaged irrigation systems across 3,500 hectares of farmland, destroyed crop storage and processing facilities, and generated debris that disrupted agricultural production. This severely constrained Haiti’s food production capacity in the aftermath, forcing increased dependence on imports. The breakdown of irrigation infrastructure and inability to process and store crops demonstrates the vulnerability of agricultural systems when critical built systems are damaged.

The 1991 Mount Pinatubo eruption in the Philippines ejected ash across croplands and grazing areas and generated mudflows that buried vegetation (Mercado et al., 1996). The ash fall caused US$60–90 million in damages to croplands, and the regional agricultural production index fell by over 15% in the year following the eruption. This demonstrates the disruption that volcanoes can inflict on agriculture through burial of and damage to land resources.

The Marshall Islands nuclear testing from 1946 to 1958 contaminated the local environment and marine ecosystems. Radioactive fallout introduced contaminants such as cesium-137 into foods such as coconut, fish, and produce at levels far exceeding global averages. The pollution of subsistence food sources undermined indigenous lifestyles dependent on local agriculture and fishing. This case illustrates the persistent damage nuclear events can inflict on natural resources that communities rely upon (Cartier, 2019).

SOURCE: ShiftN, 2009.

7.2.1.3 Environmental Quality (e.g., clean air, water, soil)

Nuclear war could impact environmental quality through the degradation of natural processes that remove pollutants and harmful substances from the air, water and soil pollution stemming from infrastructure damage, fires, and loss of waste management. Particulates, heavy metals, and hazardous chemicals released into the air from destroyed buildings, industrial facilities, and other infrastructure could contaminate air regionally. Toxic materials and debris from damaged infrastructure could also pollute waterways and soils. Widespread fires ignited by nuclear blasts could release dense smoke containing particulates, polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs), dioxins, and other hazardous compounds that could pose risks to human and ecological health. Loss of sanitation and waste management infrastructure could spread microbial and chemical pollutants through release of untreated sewage and industrial waste.

7.2.2 Key Uncertainties and Data Gaps

Our understanding of, and ability to model, the potential impacts on ecosystem services is limited by uncertainties and data gaps in several areas. Assessing potential risks to vital ecosystem services following nuclear wars faces substantial uncertainties across multiple domains. Estimating the magnitude and spatial patterns of reductions in yield of staple crops under various nuclear war scenarios remains highly uncertain. Quantifying impacts on livestock systems from climatic changes, feed shortages, and

supply chain breakdowns poses another challenge. Determining thresholds for ecosystem disruptions and recovery timelines from pervasive air, water, and soil contamination is difficult. Human behavioral responses and policy decisions could either exacerbate or mitigate ecosystem degradation, yet modeling such dynamics proves complex. Climate–ecosystem feedback loops may accelerate or counteract agricultural and habitat impacts, but their potential strengths remain unclear. Global food reserves, agricultural inputs, and distribution networks provide potential buffers, but assessing their vulnerabilities is limited. The extent to which adaptive capacities across agricultural, fishery, and natural resource management systems can withstand rapidly changing conditions depends on the resilience of the impacted community. Overall, sparse observational data, incomplete process understanding, and insufficient integrated modeling capabilities hamper robust impact assessments. Overcoming these uncertainties is crucial for enhancing ecosystem resilience and mitigating risks to critical ecological services.

NOTE: The results assume 5 Tg of soot injection. The colored cells indicate the proportion of contribution to global production of each specific crop. The values are the average change of the 5 years post-conflict and represent the mean of an ensemble of multiple climate scenarios and crop models. These results do not account for other yield-limiting factors such as shortages of labor, fuel, fertilizer, and seeds.

SOURCE: Data from Jägermeyr et al., 2020.

7.3 IMPACTS ON HUMAN HEALTH

7.3.1 State of Knowledge

A nuclear war would have potentially devastating consequences for human health and well-being, resulting in human mortality and morbidity in the immediate aftermath of the event and in the longer term (Baum and Barrett, 2018). This section summarizes current understanding of the direct (immediate, proximal) impacts and more complex (higher order, longer term) impacts felt at the individual and

community levels. There have been approximately 2,000 test detonations since WWII for scientific research, particularly around physical effects of nuclear detonations. However, there are gaps in information around human impacts, including effects on mental health and special populations, such as children, as the detonations were conducted mainly in isolated locations and are a smaller scale compared to effects from a larger nuclear war.

7.3.1.1 Direct Impacts

With respect to physical health, the nuclear blast itself will cause bodily harm, including hemorrhaging and embolisms, as well as disrupt local water sources. Thermal radiation can cause burn injuries and eye damage (e.g., flash blindness and retinal burn). Burn severity is dependent on the distance from the detonation (see Section 2.3.4). Although the effects of irradiation are not within the scope of this report, it is worth noting that individuals outside the fireball range may receive 1,000 times more ionizing radiation from the flash than they would from a year’s natural background exposure, dying within days of acute radiation poisoning. Radiation exposure depends heavily on the dose; large negative effects from high doses can lead to acute radiation syndrome (ARS), which includes symptoms such as nausea, vomiting, bleeding, and brain damage. Moderate doses of exposure can lead to increased risk of cancer or chronic radiation syndrome. Lower doses of exposure are less clear. In the aftermath of a nuclear exchange and resulting fires, exposure to the immediate environmental changes—in sunlight, temperature, precipitation, and atmospheric chemistry—would be expected to impact physical health. Over the longer term, physical health may be impacted by environmental changes (i.e., poor outdoor quality, less time outdoors, less exercise). Results from climate change may result in declines in crop production following a nuclear war (less nourishment affects physical health). Smoke from fires may lead to stratospheric ozone loss, increasing ultraviolet radiation which could lead to negative physical health outcomes, such as skin cancer, eye damage, and sunburn. Tropospheric ozone can also have impacts on pulmonary disease, asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and cardiovascular effects (Donzelli and Suarez-Varela, 2024). An important factor determining the severity of the direct impacts on survivors would be the availability, or lack, of continued care. Surviving and traumatized communities may cope poorly with noncommunicable diseases, such as diabetes and care for older people. Power outages create barriers in healthcare essentials in need of refrigeration, such as insulin, monoclonal antibodies, vaccines, and blood.

With respect to mental health, in addition to the expected physical health outcomes, there would be lasting impacts on survivors’ mental health (Baum and Barrett, 2018). This literature shows evidence of increased suicide rates, lower self-esteem, and fear of radiation, which can lead to poor mental health outcomes (Baum and Barrett, 2018). There is also evidence of social stigmatization from others in the community, often related to fear of ionizing radiation (Baum and Barrett, 2018). With respect to children, globally, there are findings regarding the attitude of children and adolescents, some as young or under the age of 11, on simply the threat of a nuclear war (Bachman, 1983; Beardslee and Mack, 1983; IOM, 1986; McGraw and Tyler, 1986). Moreover, evidence may suggest the growing concern about the threat of a nuclear war compared to years past (Bachman, 1983). Additionally, children and adolescents are made aware of nuclear war through the media or school, and often process the information without their parents and remain alone in their fears (Beardslee and Mack, 1983). Additionally, there is some evidence of generational ripple effects. One study (Ben-Ezra et al., 2012) indicated that grandchildren of Japanese living in Hiroshima and Nagasaki, who were exposed to the atomic bomb, showed higher fear of radiation exposure and higher levels of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) symptoms compared to a comparison group.

The environmental aftermath of a nuclear war could produce severe health impacts related to exposure to the products of the explosions, fires, and destruction of built environments (this report does not consider radiological effects, such as fallout), as well as severe burns, trauma, and radiation sickness from blast exposure and fallout. Emissions from resulting fires could also elevate concentrations of hazardous air pollutants such as particulates, ozone, and toxic chemicals that could impact cardiovascular

and respiratory health. Prolonged exposure to smoke could increase risks of cancer, organ damage, and premature mortality. Residual ash and contaminated water sources may contain heavy metals, dioxins, and other toxic substances that could have lasting health effects through ingestion, inhalation, and direct contact.

Health impacts that are more proximal to the nuclear detonations, in space and time, would be simpler and likely involve exposures to ambient environmental conditions, such as colder temperatures. Health impacts via exposures to air pollutants emitted in the initial blast and subsequent fires. These can include elevated concentrations of particulate matter, ozone, and toxic compounds such as PAHs, dioxins, metals. There has been significant work to measure the health impacts from those exposed to wildfire smoke as discussed in Chapter 3. Health outcomes include respiratory and cardiovascular impacts, premature mortality, negative health outcomes and more (e.g., mental health). In the ash remaining, there could be contaminants that impact human health. For example, reactive hexavalent chromium was measured in high levels in the soils and ash after large fires in California. Homes exposed to smoke may include prolonged exposures to volatile organic compounds (Li et al., 2023).

7.3.1.2 Complex Impacts

Over months to years, complex health impacts could emerge relating to disease transmission, malnutrition, mental illness, and broader wellbeing. Agricultural losses and water contamination could cause nutritional deficits, especially in vulnerable groups. Damage to health infrastructure could increase risks from treatable infectious diseases while population displacement could spread pathogens. Mental health disorders such as PTSD, anxiety, and depression would likely rise given trauma and loss. Breakdown of health systems and services could broadly impair care and worsen public health. Quantifying these complex, indirect impacts involves deeper uncertainties but are not necessarily unique to wars in which nuclear weapons are deployed.

Over longer timescales, populations could face compounding health burdens transcending acute impacts. Persistent exposure to environmental contamination from radioactive particles and toxic substances could elevate cancer risks and other chronic illnesses. Compromised ecosystems reeling from nuclear events may struggle to provide adequate nutrition, clean water, and other environmental provisions crucial for public health. Mental health strains could mount as trauma reverberates through communities, potentially exacerbating societal tensions and eroding social cohesion. Broader psychosocial dimensions such as personal security, social relationships, and overall wellbeing may deteriorate. Those displaced may experience disrupted access to health services and face new environmental health hazards in temporary settlements. Marginalized groups could bear disproportionate longer-term health burdens due to pre-existing vulnerabilities. Rigorously quantifying such complex, intergenerational impacts involving biological, ecological, societal and economic, and cultural factors presents immense challenges. Addressing these uncertainties is vital for enhancing societal resilience against catastrophic health crises.

7.3.2 Key Uncertainties and Data Gaps

Our understandings of, and ability to model, the potential impacts human health and well-being are limited by uncertainties and data gaps in several areas. Overall, much of the published literature on human health impacts is dated. Regarding physical health, there is limited clarity on effects of low exposure ionizing radiation caused by a nuclear disaster. Moreover, the secondary effects regarding impacts on physical health related to environmental impacts, both immediate and long-term, are not adequately studied, or, where they are, involve studies with limited sample sizes (for example, the Ben-Ezra et al., 2013 study). Related to environmental areas which may later impact physical and mental health, such as crop development, there are challenges in comparing studies using climate change conditions to changes in nuclear war.

BOX 7-4

Impacts on Human Health

Several disaster cases reveal potential risks to human health and well-being at individual and community levels, from both the immediate shock and the long-term public health consequences.

Pakistan’s 2022 monsoon flooding submerged health facilities across affected regions while also displacing millions and disrupting access to food and shelter, creating conditions for disease spread. Over 75% of patients in temporary health facilities had infectious diseases, including malaria, dengue fever, and skin infections. The disaster amplified various infectious diseases through environmental damage, habitat shifts, and population displacement.

The 2010 Haiti earthquake killed over 200,000 people instantly through structural collapse while also injuring over 300,000. In the weeks after, multitudes of earthquake victims suffered amputations due to crush injuries and post-disaster medical conditions (PBS News, 2012). The earthquake highlights the immediate mass mortality and trauma that can result from infrastructure damage.

Haiti’s earthquake also facilitated infectious disease outbreaks by disrupting water and sanitation systems. This amplified transmission of cholera, causing over 10,000 deaths (CDC, 2011). Floodwaters mixed with sewage, contaminating drinking water and causing rapid spread of the bacteria through populations lacking proper sanitation. This case reveals how disasters can indirectly amplify infectious diseases through environmental impacts.

The 1991 Mount Pinatubo eruption injected over 20 million tons of sulfur dioxide into the atmosphere, causing a decrease in global temperatures by 0.5°C. Models suggest this surface cooling may have altered disease vector habitats globally, affecting ranges for malaria and dengue fever among other diseases. This demonstrates the potential for volcanic eruptions to influence disease patterns through climate and atmospheric impacts.

Nuclear weapons testing from 1946-1958 exposed Marshall Islanders to high levels of radioactive exposure, resulting in near term radiation sickness as well as chronic health conditions over decades. The nuclear testing and resulting radiation and fallout has been shown to increases rates of cancer, thyroid disease and some congenital abnormalities in Marshall island resident descendants (NCI, n.d.; Nembhard et al., 2019). This demonstrates the severe and long-lasting health consequences that can result from nuclear contamination events.

7.4 IMPACTS ON SOCIETY

As noted above, the ultimate impact of a nuclear detonation includes the magnitude of the shock, and the resilience and general health status and wellbeing of the impacted communities both locally and potentially globally depending on the adversity affected ecosystem. Furthermore, while globalization may propagate risks beyond the immediate zone of impact, advancements in globalization can also result in resilience, buffering of shocks, and opportunities, including rapid deployment of resources, for interventions to mitigate risks.

7.4.1 State of Knowledge

7.4.1.1 Displacement and Migration

The mass displacement of people from their homes and communities will be an immediate consequence of a nuclear weapon detonation in a populated region; provision of shelter, healthcare, uncontaminated food and water, and protection from violence and discrimination will be urgently required. The challenge of meeting these needs without negatively impacting on-going humanitarian operations throughout the world is associated with potentially catastrophic consequences.

Accessible shelter will be critical to survival of the displaced. Tensions with host communities can result from the strain on local resources and stigma surrounding proximity to people exposed to radiation. This can complicate efforts to task surrounding communities with assisting evacuees. Access to basic assistance can be undermined when such conditions lead to violence and force the displaced to seek shelter again. Community reception centers, as described in CDC’s publication, Population Monitoring in Radiation Emergencies: A Guide for State and Local Public Health Planners (NCEH, 2014) present an infrastructure to address the needs of the displaced population as well as concerned citizens.

BOX 7-5

Impacts on Societal Resilience

Several disaster events highlight the potential for nuclear wars to severely disrupt critical infrastructure, cause displacement, and test the resilience of social institutions.

Pakistan’s 2022 flooding damaged over 2 million homes and displaced 6.4 million people. The destruction weakened infrastructure for communication, governance, and service delivery while amplifying poverty/inequality. However, the crisis also prompted over $1.7 billion in international aid commitments. This reveals how disasters can damage institutions but also catalyze external support.

Australia’s 2019-2020 bushfires razed over 5,900 buildings and displaced thousands. The crisis prompted over $2 billion in disaster relief payments. The fires also exacted an estimated $3.6 billion toll on domestic tourism revenues. This demonstrates impacts on housing, governance resources, and broader economic systems.

The 2010 Eyjafjallajökull volcanic eruption in Iceland severely disrupted European air travel and trade for weeks, highlighting interconnected infrastructures’ vulnerability to disruptions. The ash cloud grounded over 100,000 flights, costing airlines over $1.7 billion.

The 2010 Haiti earthquake left over 1 million people homeless with over 100,000 damaged/destroyed buildings. Communications systems, roads, hospitals and government buildings were debilitated, constraining emergency response. Mass population displacement overwhelmed local resources and governance capacity.

The 1991 Pinatubo eruption displaced over 86,000 people around the volcano while also damaging infrastructure like bridges and roads. The eruption strengthened ties between U.S./Philippine volcanological institutions through scientific exchanges during the crisis. This showcases displacement strains but also potential opportunities for international cooperation.

From 1946-1958, the US conducted 67 nuclear tests in the Marshall Islands, temporarily or permanently displacing communities, contaminating islands and altering indigenous lifestyles. The Bikini Atoll, in particular, remains uninhabitable today given radiation levels unsafe for human habitation, as is the case for a few other worldwide nuclear test locations (LLNL, n.d.). This reveals the potential for nuclear surface bursts events to fundamentally reshape social systems.

The nutritional status of the displaced can be affected by various factors including inadequate food intake; poor water, hygiene, and sanitation; and insufficient access to healthcare. Additional complication in the event of a nuclear weapon detonation is the provision of food and water uncontaminated by radioactive fallout. Healthcare needs for displaced survivors of a nuclear weapon detonation include treatment for direct impacts, including injuries. Many displaced people may have burns or been exposed to radiation, requiring resource-intensive medical diagnosis and treatment. For example, treatment of ARS may require blood transfusions, antibiotics and the use of blood-stimulating agents, or bone marrow transplants in specialized medical units. Displaced people treated for ARS would require constant monitoring. Indirect impacts that may occur in the aftermath of the event include increased rates of infectious diseases or malnutrition. In addition, there will be a need for specialist support for psychological trauma in the displaced.

A nuclear weapon detonation could be associated with prolonged duration of displacement of the impacted population and may require provision of services such as education and temporary health infrastructure to facilitate healthcare and public health services.

It may not be possible or desirable for many displaced people to return to their area of origin, for reasons including trauma, fear of residual radiation, and the absence of income-generating opportunities in areas of origin; in such cases, access to support will be required pending resettlement elsewhere. In some cases it will be more feasible to relocate communities or their remnants than to attempt reconstruction (Okada et al., 2021; Waddington et al., 2017), raising internal migration issues. Ensuring the safety of humanitarian workers, especially with regard to the effects of radioactive fallout, requires adequate training, equipment, and protocols.

A single nuclear weapon detonation has the potential to significantly stress the existing caseload of displaced people receiving humanitarian assistance and protection. Multiple detonations would result in catastrophic consequences for the humanitarian response, with negative impacts on those people who

were receiving and in need of life-saving protection and assistance prior to the detonations. The adaptive capacity and social coherence of affected communities is also influenced by voluntary displacement. Labeling a displacement as voluntary as opposed to mandatory is influenced by several factors including the voluntary nature itself and influencing factors such as governance structures, community resources, and pre- and post- disaster public relations.

7.4.1.2 Societal Fragility and Resilience

A nuclear detonation will cause widespread and profound social, psychological, and behavioral impacts that affect how the incident unfolds and the severity of consequences. Primary issues include psychological impacts on the general public, potential effects on emergency responders and other caregivers, and broader impacts on communities and society. Recent large-scale disasters, including the COVID-19 pandemic, have demonstrated the importance of the psychosocial consequences of disruptive events.

A nuclear crisis is likely to surpass the COVID-19 pandemic in terms of levels of panic, hoarding, and shortages of medical supplies. Rushes to stockpile resources such as clean water, iodine, and the equipment necessary to treat burns may occur. Lockdowns, restrictions on domestic and international travel and decrease of civil liberties may occur to facilitate management of the crisis and prevent chaos. People’s ability to access reliable information may be compromised, highlighting the importance of clear and unequivocal messaging from trusted government entities.

Nuclear winter may be one of the most far-reaching public health crisis scenarios, with effects including threats to global food security. Secondary impacts would disrupt transport, food, water, trade, energy, finance, and communication to the detriment of public health efforts.

However, if preparations are made in advance, there is significant potential to survive nuclear winter. Preparedness for nuclear winter can include developing stockpiles of food, water, vaccines, and other medicines and other resources that could aid the survival of a large portion of the human population. Building community resilience is a crucial part of this public health preparedness.

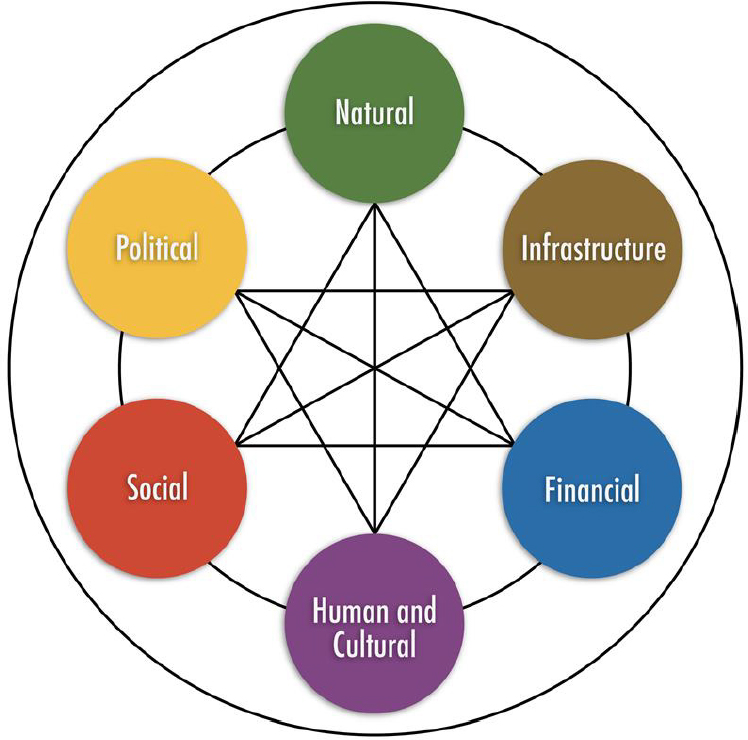

With respect to community resilience and social capital, Peregrine et al. (2021) highlighted the social resilience consequences of a nuclear winter. From a broader perspective, the science undergirding community resilience has significantly evolved through several consensus studies undertaken by the National Academies of Science, Engineering, and Medicine (NASEM, 2019 and 2023). Core to these assessments is defining social capital as a key domain influencing adaptive capacity. As depicted in Figure 7-6 there are six components influencing community capital: natural, infrastructure, financial, human and cultural, social, and political. Of note is that many vulnerable communities lack resources in each of these areas, making them less resilient to withstand as well as recover from the environmental health consequences of a nuclear event.

A previous consensus study from the National Academies (NASEM, 2019) identified five pillars of resilience building, Figure 7-7 depicts more explicitly how these interact to support a resilient community: data (collection, analysis, and integration of big data); infrastructure (beyond transportation but specifically health system functioning); funding (interdisaster not only post-event); human Capital (especially the health workforce); and governance (stability). Factors to strengthen each pillar are a set of core principles to ensure a community-tailored participatory process: collaboration, transparency, equity, community partnerships, and engagement. Preparedness for a nuclear event must embed these aspects and core components.

7.4.2 Key Uncertainties and Data Gaps

Our understandings of, and ability to model, the potential societal impacts are hampered by substantial uncertainties and data gaps in several areas. Predicting the complex human behavioral responses and emergent social dynamics that could exacerbate or mitigate disruptions poses a central challenge. Identifying the tipping points where compounding system failures trigger societal breakdowns remains elusive. Quantifying the cascading effects rippling across interconnected critical infrastructure networks such power grids, transportation, and communications systems is hindered by their intricate couplings. Insufficient data on preexisting social vulnerabilities, inequities, and community resilience obscures localized risk profiles. Furthermore, determining the long-term psychological toll and cultural upheaval across affected populations over generations proves arduous due to the confluence of diverse variables. Overcoming these uncertainties necessitates transdisciplinary modeling approaches that integrate complexity science, big data analytics, and participatory methods to strengthen anticipation of post-nuclear societal risks.

7.5 SUMMARY

The previous chapters in this report systematically review the mechanistic pathways extending from a plausible set of initial weapon exchanges through their resulting fire dynamics and emissions, and subsequent climatic and ecosystem disruptions. This chapter extends these environmental effects into potential societal and economic consequences across three categories: impacts on ecosystem services, human health, and societal resilience over weeks to decades. The immense challenges in quantifying these impacts stem from our limited understanding of the immediate environmental effects and the complex dynamics between human and natural systems. The analytical challenge is compounded by the vast array of dynamic interactions and poorly characterized feedbacks. Two key disruption pathways are identified: global climatic disruption from large exchanges between major powers and localized environmental degradation from smaller exchanges. These can be further amplified by the complex global and regional societal and economic interconnectedness.

Potential impacts on agriculture and food production could be extensive, with widespread cooling and precipitation decreases leading to lower crop yields, reduced livestock productivity, and disrupted planting and harvesting cycles. Impacts would likely vary regionally, with temperate areas above 30°N latitude facing major effects. Marine and freshwater fisheries could also experience significant disruptions. Environmental quality would deteriorate through air, water, and soil pollution from infrastructure damage, fires, and waste mismanagement. However, substantial uncertainties exist in quantifying specific outcomes such as yield reductions and determining ecosystem disruption thresholds.

Direct health impacts include blast injuries, radiation exposure, lack of continued care, and effects from environmental changes. Complex, indirect impacts over longer timescales could involve disease transmission, malnutrition, mental illness, and broader public health crises from compromised health systems. Persistent exposure to environmental contamination and psychosocial stressors may have intergenerational consequences. Gaps remain in understanding low-dose radiation effects and secondary environmental impacts on health.

Mass displacement would severely strain provision of shelter, healthcare, food, water, and protection, potentially leading to exploitation and violence. Psychological impacts on the public and responders could be profound, while broader societal effects may include panic, hoarding, and disruptions to civil liberties. Moreover, substantial uncertainties in predicting complex human behavioral responses, detecting societal tipping points, quantifying the effects of cascading failures across critical systems, and assessing long-term psychological harms will hamper development of approaches to improving preparedness and building community resilience that would mitigate risk.

However, it is important to note that key factors influencing the ultimate impact of a nuclear detonation include the magnitude of the shock and the resilience and general health status and well-being of the impacted communities both locally and potentially globally depending on the adversely affected

ecosystem. Furthermore, while globalization may propagate risks beyond the immediate zone of impact, advancements in globalization can also result in resilience, buffering of shocks, and opportunities, including rapid deployment of resources, for interventions to mitigate risks.

7.6 FINDINGS AND RECOMMENDATIONS

FINDING 7-1: The global supply chain, financial markets, and communication networks are all interconnected. A shock to these complex systems (e.g., nuclear war) could result in cascading risks beyond the directly impacted populations. Globally, the interconnected impacts on ecosystems especially food security, the economy, society, and the environment are influenced by the magnitude of the nuclear event and the directly and indirectly impacted communities’ resilience, health status, and well-being. Hence, there is a critical need for developing and investing in multidisciplinary frameworks and advanced research to anticipate and, where possible, mitigate the potential risks to and vulnerabilities of these interconnected systems.

RECOMMENDATION 7-1: Agencies such as the U.S. Departments of Health and Human Services, Defense, Energy, and Agriculture should collaborate in the development and implementation of an enterprise-wide approach to assess the potential societal and economic impacts of a nuclear detonation on food, water, and health, taking into account disruption to global trade, financial markets, supply chains, and communication networks.

FINDING 7-2: The health and well-being of people and society are deeply coupled with, and inextricably linked to, the health of ecosystems. A comprehensive characterization of the societal and economic and environmental impacts of a nuclear war is substantially hampered by limitations in observational data, process understanding, and modeling capabilities. For example, there is a critical need to invest in advanced research and modeling capabilities to assess the potential impacts on agriculture, food security, and food safety.

RECOMMENDATION 7-2: Agencies such as the U.S. Departments of Health and Human Services, Defense, Energy, and Agriculture, the Environmental Protection Agency, and the National Science Foundation should advance predictive modeling research to bolster preparedness strategies during the interdisaster period. Specifically, a multidisciplinary approach that integrates different predictive models simulating climate, crop growth, livestock dynamics, and economic factors at different scales through model intercomparison and ensembles can provide considerable insight into potential nuclear war scenarios and their consequences. These efforts can help policymakers reach informed decisions, develop contingency plans, and design strategies to mitigate the worst outcomes and ensure food resilience in the face of such events.

FINDING 7-3: Impacts of a sudden decline in mean temperature and precipitation on crop yields and fisheries production are little understood and poorly constrained. There is extensive research on effects of gradual global warming on agricultural productivity, for example, but limited information on impacts of sudden global cooling. Furthermore, existing agricultural models and freshwater ecosystem models are not well suited to capture the impacts of a sudden shock. Furthermore, an assessment of impacts of a nuclear detonation on environmental systems requires understanding the cascading effects from climate, ecosystem, and hydrologic alterations, and subsequent effects on food production, trade, and human health.

RECOMMENDATION 7-3: Model Intercomparison and Improvement: Agencies such as the U.S. Departments of Health and Human Services, Defense, Energy, and Agriculture, the National Institutes of Health, the National Science Foundation, the Centers for Disease

Control and Prevention, the U.S. Agency for International Development, and the Environmental Protection Agency should advance transdisciplinary research to develop and interpret intercomparison models as well as promote information exchange by the following key stakeholders: the Integrated Assessment Modeling Community, the Coupled Model Intercomparison Project, the Earth system model community, the Agricultural Model Intercomparison and Improvement Project, the Inter-Sectoral Impact Model Intercomparison Project, and population health predictive modeling experts. The purpose of these recommended actions is to provide key U.S. federal, state, and local authorities and the U.S. global partners with protocols and tools to prepare for, respond to, and manage nuclear events of any magnitude. Research should invest in the following key areas:

- Analysis of climate impacts (sudden cooling) on livestock, fisheries, forests, and other natural resource systems that provide food, materials, medicines, and energy.

- Atmospheric transport models to estimate the fate of pollutants from potential infrastructure damage and fires in order to quantify pollution risks to ecosystems.

- Examination of ecosystem impacts and recovery time frames for relevant air, water, and soil contaminants through toxicity testing and field studies.

- Crop models to address impacts from surface ozone, ultraviolet radiation, and freshwater availability.

- Integration of simulated climatic changes from nuclear war scenarios into crop models to strengthen projections of agricultural productivity losses for major staple crops in key producing regions.

- Evaluation of adaptive capacities and vulnerabilities of agricultural and natural resource systems to inform targeted resilience strategies such asland-use changes and policy responses (e.g. trade protection).

- Integrated modeling to capture complex connections and feedbacks between climate changes, pollution, and human systems including food trade and reserves, and consumer behaviors.

- Improvement of geographic data on global food stocks, agricultural inputs, production capacities, and supply chain infrastructures to identify buffer capacities along with vulnerabilities.

- Scenario modeling and economic analysis to guide policies that could mitigate food insecurity and ecological degradation if nuclear war occurs.

- Assessment and periodic monitoring of social capital domains in at-risk communities. These domains include natural, infrastructure, financial, human, and cultural, social, and political capital.

- Predictive modeling of the integration of data characterizing the social capital domains and the pillars of community resilience in selected vulnerable communities.

- Use of tabletop exercises, game theory, and related tools to address aspects that cannot be modeled.

FINDING 7-4: Mortality and morbidity associated with nuclear detonations can result from multipronged exposures associated with contaminated environmental media, specifically air and water, disruption of food systems, the fragility of the health system infrastructure, and the impacts on economic and societal resilience following nuclear exchanges.

RECOMMENDATION 7-4: To effectively respond to and recover from a nuclear detonation, agencies such as the U.S. Departments of Health and Human Services (HHS) and Energy, the National Institutes of Health, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and the Environmental Protection Agency should advance research to determine the differential impact on survivors and different humanitarian assistance

required after a nuclear detonation compared to a severe weather event, an environmental disaster, or the shocks and stressors related to climate change. HHS, the U.S. Department of Homeland Security, and the Federal Emergency Management Agency, in collaboration with state and local health departments, should strengthen investments in health system preparedness, including the Strategic National Stockpile, hospital preparedness, and the public health infrastructure, specifically quantitatively and qualitatively strengthening the public health and health services workforce.

FINDING 7-5: Nuclear detonations can have both short- and longer-term adverse societal impacts on each social capital domain—natural, infrastructure, financial, human and cultural, and political. Furthermore, societal effects are multisectoral in nature, amplifying the impact at the individual level. Consequently, the strength of community resilience and its social capital influences a community’s recovery in the aftermath of a nuclear detonation.

RECOMMENDATION 7-5: Agencies such as the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, the National Institutes of Health, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and the Environmental Protection Agency, in collaboration with state and local health departments, should advance community-engaged implementation research to determine how disparities, inequities, and other social determinants of health influence the impact of nuclear detonations at the societal level.

7.7 REFERENCES

Ahmed, M., and M. Farooq. 2022. Pakistan floods raise fears of hunger after crops wrecked. The Associated Press, APNews.com.

Allison, E. H., and D. J. Mills. 2018. Counting the fish eaten rather than the fish caught. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 115(29):7459-7461. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1808755115.

Bachman, J. G. 1983. American High School Seniors View the Military: 1976-1982. Armed Forces and Society 10(1):86-104. https://doi.org/10.1177/0095327x8301000104.

Baum, S., and A. Barrett. 2018. A Model for the Impacts of Nuclear War. Working Paper 18-2. Global Catastrophic Risk Institute.

Beardslee, W. R., and J. E. Mack. 1983. Adolescents and the threat of nuclear war: the evolution of a perspective. Yale J Biol Med 56(2):79-91.

Ben-Ezra, M., Y. Palgi, Y. Soffer, and A. Shrira. 2012. Mental health consequences of the 2011 Fukushima nuclear disaster: are the grandchildren of people living in Hiroshima and Nagasaki during the drop of the atomic bomb more vulnerable? World Psychiatry 11(2):133. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wpsyc.2012.05.011.

Ben-Ezra, M., Y. Palgi, O. Aviel, Y. Dubiner, B. Evelyn, Y. Soffer, and A. Shrira. 2013. Face it: Collecting mental health and disaster related data using Facebook vs. personal interview: The case of the 2011 Fukushima nuclear disaster. Psychiatry Research 208(1):91-93. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2012.11.006.

Bhattacharya, S. 2023. Economic, Social and Geopolitical Impact of Israel Hamas Conflict in 2023. International Journal of Multidisciplinary Research and Publication 6(6):330-334.

Bowman, D. M. J. S., G. J. Williamson, R. K. Gibson, R. A. Bradstock, and R. J. Keenan. 2021. The severity and extent of the Australia 2019–20 Eucalyptus forest fires are not the legacy of forest management. Nature Ecology & Evolution 5(7):1003-1010. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41559-021-01464-6.

Broadley, A., B. Stewart-Koster, M. A. Burford, and C. J. Brown. 2022. A global review of the critical link between river flows and productivity in marine fisheries. Reviews in Fish Biology and Fisheries 32(3):805-825. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11160-022-09711-0.

Cartier, K. M. S. 2019. Marshall Islands Nuclear Contamination Still Dangerously High. Eos 100. https://doi.org/10.1029/2019EO128905.

Center for Disaster Philanthropy. 2023. 2022 Pakistan Floods., September 6. https://disasterphilanthropy.org/disasters/2022-pakistan-floods/ (accessed July 2, 2024).

CDC (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention). 2011. Haiti Cholera Outbreak. https://www.cdc.gov/orr/responses/haiti-cholera-outbreak.html#:~:text=On%20October%2020%2C%202010%2C%20the,cases%20and%20nearly%2010%2C000%20deaths (accessed July 24, 2024).

Cottrell, R.S., Nash, K.L., Halpern, B.S., Remenyi, T.A., Corney, S.P., Fleming, A., Fulton, E.A., Hornborg, S., Johne, A., Watson, R.A. and Blanchard, J.L., 2019. Food production shocks across land and sea. Nature Sustainability, 2(2), pp.130-137.

Crowley, M. 2003. An introduction to the WTO and GATT. Economic Perspectives 27(Q-IV):42-57.

Davis, K.F., Downs, S. & Gephart, J.A. Towards food supply chain resilience to environmental shocks. Nat Food 2, 54–65 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s43016-020-00196-3