Potential Environmental Effects of Nuclear War (2025)

Chapter: 2 Employment Scenarios and Weapons Effects

2

Employment Scenarios and Weapons Effects

2.1 INTRODUCTION

This report explores the environmental effects and societal and economic consequences that would be expected to follow in the weeks-to-decades after a nuclear war. The exploration begins in this chapter (Chapter 2) with the consideration of four plausible scenarios for the employment of nuclear weapons, along with a description of the immediate effects of the energy release and blast from a nuclear detonation. As noted in the report introduction (Chapter 1), radioactive fallout is beyond the scope of this study and is therefore not addressed. Additionally, the consensus study’s efforts herein are to provide plausible baseline scenarios to facilitate sensitivity analyses in modeling the potential environmental effects of nuclear war. Note, examining and providing an analysis of the environmental and societal and economic outcomes of the four scenarios is beyond the scope of this study. The narrative in this chapter leads directly into an exploration in the next chapter of the fire dynamics and emissions that may result from nuclear detonations (Chapter 3) and the larger impacts in the remaining chapters.

BOX 2-1

Key Terms

Fission-Based Weapon: Weapon in which part of the explosion energy results from fission reactions.

Height of Burst (HOB): Height above Earth’s surface at which the nuclear weapon detonates in the air (Glasstone and Dolan, 1977).

Nuclear Cloud: A cloud that results after a nuclear detonation and contains radioactive fission products and often entrained environmental debris and condensed water.

Nuclear Detonation: Premeditated deliberate use and blast of a nuclear weapon.

Nuclear Employment Scenario: Context and framework for how a single or multiple nuclear weapon exchange(s) between countries could play out.

Nuclear Exchange: Employment of one or more nuclear weapon(s) and subsequent detonations between nuclear weapon states.

Nuclear Explosion: Large blast resulting from the rapid nuclear reactions and uncontrolled release of energy from nuclear materials inside a nuclear weapon capable of fission and fusion reactions.

Nuclear Weapon: Explosive device that derives its destructive force from nuclear reactions, either through the splitting of atomic nuclei (a fission reaction) or the fusing of atomic nuclei (a fusion reaction).

Overpressure: Increase above atmospheric pressure at the front of an explosion-produced shock wave in the air.

Source Term: For a modeling study of the atmospheric and climatic effects of a nuclear detonation, the initial amounts of particulates and other material released or mobilized into the atmosphere.

Thermonuclear Weapon: Weapon in which part of the explosion energy results from thermonuclear fusion reactions. The high temperatures required are obtained by means of a fission explosion (Glasstone and Dolan, 1977).

Weapon Yield: Total effective energy released in a nuclear explosion, usually expressed in terms of the equivalent tonnage of TNT required to produce the same energy release in an explosion.

Nuclear weapons employment scenarios are needed to estimate the source terms of particulates and other material released or mobilized into the atmosphere—in particular, their quantity and vertical distribution. The four general scenarios described in this chapter are organized by the total number of warheads detonated in each major scenario (see Table 2-1). These numbers are also compared with detonation scenarios appearing in previous studies of the potential climate impacts from nuclear detonations and subsequent weapon-initiated fires. Although yield classes of weapons are summarized, the types of warheads such as fission versus thermonuclear are not pertinent to this review because the potential impact on the environment is independent of the details of the nuclear device. By contrast, the details that are necessary for this review include the numbers and yields of warheads, generalized target locations, and heights-of-burst (HOBs), which would vary depending on whether the goal is to maximize the damage area or to attack a specific point target (e.g., at the surface or underground). The discussion of these scenarios concludes with the uncertainties arising from the use of general employment scenarios when specific military goals are not presented.

Following the introduction of the committee’s generalized employment scenarios, the discussion turns to the immediate physical effects of nuclear detonations, or “weapons effects,” which include the thermal energy from the initial fireball and air blast effects from the atmospheric shock wave. Generally, nuclear detonations and HOBs that maximize the area of a damaging air blast tend to also minimize the amount of radioactive fallout.1 Finally, the discussion considers key sources of uncertainty identified by the committee, including the coupling between air blast effects and the resulting fires in rubblized damage zones (areas where freestanding buildings have collapsed); the effects of terrain and related factors in urban areas, including shadowing by large buildings; and the role of weather in modulating weapons effects.

2.2 EMPLOYMENT SCENARIOS

2.2.1 Past Studies of Climate Effects from Nuclear Weapon Detonations

The most recent major studies of large- and regional-scale nuclear warhead detonations include a 1985 National Research Council study that considered a hypothetical U.S.-Soviet World War III (WWIII)-type exchange with a total of 25,100 detonated weapons (of up to 8,500 Mt total yield) (NRC, 1985), and a 2019 academic study analyzing a hypothetical regional conflict between India and Pakistan involving the detonation of 250 warheads (of up to 25 Mt total yield) (Toon et al., 2019). An earlier NRC study also considered a worst-case scenario of up to 5,500 nuclear detonations of very high-yield thermonuclear weapons for a similar WW3-type Soviet-U.S. exchange (of up to 10,000 Mt total yield) (NRC, 1975). Notably, each of the employment scenarios in these studies assumed the use of one-half of the available weapons against a range of military, industrial, and civilian targets. This 50% usage factor was considered reasonable based on several operational and technical considerations (Koch, 2018; NRC, 1985) including: a portion of warheads being in reserve or inactive status and not immediately available for employment;2 a portion of delivery systems being in maintenance status or some other force status that made them unavailable for immediate use; and the use of an escalating approach to weapons use.3

___________________

1 This refers to what is generally known as the “fallout-free HOB,” whereby the detonation fireball containing bomb debris does not touch and interact hydrodynamically with activated ground debris that can be lofted by the produced shock waves and thermal buoyancy effects (FEMA, 1987; 2022; Spriggs et al., 2020).

2 The reasoning for one-half is described in the later study (NRC, 1985). “The fraction of one-half has been applied to take into account the following factors that would reduce the number of weapons actually delivered on target: weapons destroyed by counter force attacks, weapons destroyed by defenses, weapon systems unreliable under combat conditions, and weapons held in reserve. This assumption should be within a factor of 2 of the exchange in a general nuclear war.” See also Koch (2018) that discusses changes made to the nuclear weapons programs during the George H. W. Bush administration.

3 It is generally accepted in nuclear deterrence and warfighting doctrine that a series of escalation steps in weapons use would precede the next step with the theory that escalation will stop when one side does not wish to continue up the escalation ladder to full use of all available nuclear weapons Carter et al., (1987), Glaser et al. (2022).

Starting with the scenarios to provide the source terms for the number of nuclear detonations and with use of the fire and target fuel models available in the 1985 and 2019 studies, including from Glasstone and Dolan (1977), black carbon and soot production were estimated and input into atmospheric and climate models.

In this National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine (NASEM) study, plausible nuclear employment scenarios are based on recent cited estimates of nuclear weapon stockpiles. These estimates of the total nuclear weapons have fallen dramatically (by approximately 90%4) relative to estimated global stockpiles at the time of the earlier 1985 and 1975 studies as shown in Figure 2-1 and Table 2-1. The committee also notes that technological advances in both missile and aircraft delivery and guidance systems coupled with improvements in warhead design and reliability of each system, have led to substantial reductions in the “yield on target” required to achieve military objectives (Carter et al., 1987; Glaser et al., 2022).

To summarize, the following parameters were considered in constructing generalized nuclear employment scenarios:

- Yield, HOB, and number of nuclear warheads,

- Generalized locations of targets,

- Time distribution of the explosions,

- Atmospheric conditions, and

- Other factors that may have a significant impact on the effects that create the initial conditions for the fires and production of smoke, for example, weather and time of year.

2.2.2 Current Study Nuclear Employment Scenarios and Considerations

This National Academies’ study considers four plausible scenarios as described in detail in Table 2-2 and include:

- Large-scale strategic exchange of 2000 warheads.5

- Moderate-scale strategic exchange of 400 warheads.6

- Small-scale regional exchange of 150 warheads.7

- Very small-scale use of a single warhead, to “demonstrate resolve” and a willingness to employ nuclear warheads.

The warhead yields shown in the table are rounded into four general classes, that is, 1 Mt, 500 kt, 100 kt, and 20 kt, consistent with estimates found in the openly available literature (DOE, 2015; Glasstone and Dolan, 1977; Mikhailov, 1996; SIPRI, 2020), and do not necessarily reflect the actual

___________________

4 Estimates in the open literature of total worldwide nuclear weapon inventory as of 2023 is approximately 12,500 weapons, versus 48,000 and 65,000 weapons in 1975 and 1985, respectively (as described in DOS (2024), Kristensen et al. (2023a).

5 This large-scale employment scenario is based on approximately one-half of the openly estimated U.S. and Russian weapons in each country’s actively deployed strategic weapons (of 1550 each under New START) and a smaller number of nonstrategic weapons (consistent with CACNP [2020b], Fink [2024], Kristensen et al., [2023a], and NNSA [2024]) that might precede use of the strategic weapons in a regional precursor exchange scenario leading to a larger strategic exchange, that is, 500 regional nonstrategic weapons followed by use of 1,500 strategic weapons, for a total employment of 2,000 weapons. However, New START has been suspended as noted in Chapter 1 with uncertain implications for these assumptions.

6 This moderate-scale employment scenario is based on approximately half of China’s estimated weapons inventory, that is, 500 weapons (CACNP, 2020d; Kristensen et al., 2024; DoD, 2023), and an equivalent number of U.S. weapons in response.

7 This regional employment scenario is based on the Toon et al. (2019) India-Pakistan nuclear employment study, using approximately half of the 2024 estimated Indian and Pakistani inventory numbers of 160 and 170 respectively, reported by (CACNP 2019a,b, 2021b; Kristensen and Korda, 2022a; Kristensen et al., 2023c).

yields of current weapons in any stockpile. From an uncertainty standpoint and for use in studying the effects of varying the key parameters, the number of warheads used for each employment scenario could be higher or they could be lower, just as the yield class for warheads could have a similar variation in numbers deployed, higher or lower, and the effects of which then can be ascertained in various parametric studies.

The United States released its nuclear weapons stockpile numbers dating back to 1945 as shown in Figure 2-1. The maximum number of weapons for the United States was in 1967 when the country possessed 31,255. The Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR) numbers peaked in the 1980’s with ca. 39,000 (UN, 2024). As noted in Chapter 1, with New START, the United States and Russia agreed to limit the number of operationally deployed and accountable strategic nuclear warheads to 1,550 for each country (Arms Control Association, 2022). In effect the stockpile of each country has decreased by approximately 90% since the end of the Cold War. As mentioned previously, this reduction, which resulted in starkly lower stockpile numbers than those contemporaneous to the previous studies of the 1970s and 1980s, is reflected in the scenario values employed by this committee.

SOURCE: DOS (2024).

Although the stockpiles for the United States and Russia have decreased, other states, in particular the People’s Republic of China (PRC) and the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea (DPRK), now maintain growing nuclear stockpiles. Estimated values and additional references for these stockpiles from 2019 to 2024 are given in Table 2-1 and historic values plotted in Figure 2-2. Of note, the number of weapons in the DPRK is estimated to be steadily increasing, and it is understood that the PRC could reach 1,000 weapons by 2030 as they seek to reach parity with the United States (DoD, 2023; Gill, 2024).

TABLE 2-1 Current Estimated Stockpiles

| (a) United Kingdom | (b) France | (c) India | (d) Pakistan | (e) China* | (f) North Korea* |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 225 | 290 | 160 | 170 | 500 | 50 |

NOTE: *The number of weapons for China and North Korea are presumed to be increasing.

SOURCES: (a) CACNP 2020c; Kristensen and Korda, 2021; Mills, 2024. (b) CACNP, 2020a; Horovitz and Wachs, 2023; Kristensen et al., 2023b. (c) CACNP, 2021b; Kristensen and Korda, 2022a. (d) CACNP, 2019a; Kristensen et al., 2023c. (e) CACNP, 2020d; DoD, 2023. (f) CACNP, 2021a; Kristensen and Korda, 2022b; Nikitin, 2023; Rai, 2024.

SOURCES: Kristensen and Norris, 2015; Kristensen and Korda, 2020; Kristensen et al., 2023a; Norris and Kristensen, 2010; and references cited in Table 2-1.

2.2.3 Employment Scenario Details

Each employment scenario (Table 2-2) portrays a notionally determined number of warheads for each yield class based on current openly available estimated stockpile numbers (as seen in Figure 2-2), by general target location, and the general HOB for each detonation. The majority of detonation locations are assumed to be on military targets (“counterforce” targeting), as the assumed highest priority in order to deny an adversary the ability to use its stockpile for continued escalation or to make future weapons.8 Most, but not all military targets, under a counterforce targeting doctrine are assumed to lie outside urban areas. The committee noted that while some military targets are likely in or near urban areas, present-day weapons are generally more accurate and are of lower yields, which would likely reduce the impact on civilian structures.9 In this section, through a compilation of open published literature and information gathering, four hypothetical scenarios are proposed herein with plausible estimates of nuclear warheads as a suggested baseline for researchers and stakeholders to use in future analyses of nuclear war scenarios (Table 2-2). The numbers in these scenarios are meant to be indicative of relative scale for the different types of deployment scenarios and should not be interpreted as indicating the number of warheads in any given country’s stockpile.

Similarly, the National Security Report by Frankel et al. (2015) arrived independently at four general scenarios listed here:

- United States-Russian Unconstrained Nuclear War.

- Regional Nuclear War Between India and Pakistan.

- Chinese High-Altitude EMP Attack on Naval Forces.

- A single weapon detonated in a city.

Scenarios 1, 2, and 4, above, align with those described in this report. The remaining scenario required a slightly different approach in consideration of the present time in which Great Power Competition is recognized as a driving force for U.S. policy makers and public sentiment (Friedman, 2019; Miles and Miller, 2019; Savoy and Staguhn, 2022). With the current modernization and expansion of the nuclear weapon programs in China (Talmadge, 2019), this report poses number 3 of these scenarios as an exchange between the United States and China having a number of weapons greater than an India-Pakistan exchange but smaller than a U.S.-Russian war. These scenarios were also limited to the current estimated and cited stockpile numbers and not potential stockpiles in the future, or the possibility of a tripolar war with the United States, China, and Russia.10 These numbers are much smaller than what they would have been in the 1980s, and future numbers might be different based on the unknown realities at that time.

This study ascribes no probability to any given scenario but proposes these as a range of inputs with which to study potential environmental impacts and recommends further development of a more comprehensive set of scenarios. Recognizing that the number of warheads in an exchange could exceed those in the table by more than 100% or be limited to less than 50%, in the different cases, parametric

___________________

8 The goal of counterforce targeting would thus be to force an adversary to terminate weapons use or, better yet, to be deterred from using nuclear weapons entirely or moving up the nuclear escalation ladder. Counterforce targets are defined as vulnerable military targets including military bases, missile silos, command-and-control facilities, and transportation hubs. Countervalue targeting is understood to be civilian and cultural targets, population centers, and infrastructure. In some sense, countervalue targets can be understood to be punitive or for revenge (Lieber and Press, 2023); however, these terms are currently considered outdated and inappropriate with the current U.S. nuclear strategy.

9 In the seminal study by Turco et al. (1983), the scenarios described had 20% of the targets in urban or industrial areas, 57% of those being surface bursts. The NRC (1985) report proposed a baseline large-scale scenario for consideration with 28% of the weapons targeting urban sites and 20% of the weapons being surface explosions. These values are similar to those in Table 2-2.

10 Dr. Christopher Yeaw discussed this topic in this presentation to the EENW committee, March 24, 2024. Recordings of public meetings are available through the National Academies. For more information contact PARO@nas.edu.

studies with different source terms will be valuable to model how the impacts from these possible uncertainties propagate through the causal pathway in Figure 1-1 to the climate models and ecosystem and societal and economic impacts (Recommendation 2-1). Predicting the environmental outcomes from representative employment scenarios bring significant uncertainties for different reasons, and the impact will scale with the size of the nuclear employment scenario.

| Yield Classes in kt | HOB Options | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Target Area Characteristica | 1000 | 500 | 100 | 20 | Fallout Free/Optimum for Blast | Low-Altitude/Surface | |

| Large Scale = 2,000 | Adjacent to or within urban areas | - | 120 | 280 | - | 250 | 150 |

| Outside urban areas | 390 | 540 | 670 | - | 670 | 930 | |

| 100% of predicted detonations between 70N and 20N latitude | |||||||

| Moderate Scale = 400 | Adjacent to or within urban areas | 20 | 120 | 40 | - | 30 | 150 |

| Outside urban areas | - | 120 | 100 | - | 200 | 20 | |

| 100% of predicted detonations between 65N and 20N latitude | |||||||

| Regional Scale = 150 | Adjacent to or within urban areas | - | - | - | 20 | 20 | - |

| Outside urban areas | - | - | - | 130 | 130 | - | |

| 100% of predicted detonations between 35N and 8N latitude | |||||||

| Limited = 1 | Adjacent to or within urban areas | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Outside urban areas | - | - | - | 1 | 1 | - | |

| 100% of predicted detonations between 50N and 45N latitude | |||||||

NOTES: Presented are two target types, generalized yields, and logical estimates for HOB based on a distribution of target classes from military to key strategic locations. Further explanations as to how Table 2-2 was derived are provided in Section 2.2.2. As previously mentioned, warhead yields are rounded into four general classes consistent with estimates found in the openly available literature and do not necessarily reflect the actual yields of current weapons in any stockpile.

a Urban areas are those with a population center of greater than 100,000. Dashes (-) indicate zero values have been added for clarity.

2.2.4 Employment Factors That Affect Fire Dynamics and Emissions

The amount of smoke that is emitted and lofted into the atmosphere for each weapon detonation at a given target (in Table 2-2) constitutes one major element of the “source terms,” or initial conditions for the subsequent transport and persistence of the smoke emissions in the stratosphere. Climate models use these source terms to predict the resultant effects on the climate and temperature at Earth’s surface (NRC, 1985; Toon et al., 2019). Note that removal of particles and the lofting of smoke containing black carbon are also important and are discussed elsewhere in this report. The employment factors affecting fire dynamics and emissions include weapon yields and types; target types and location parameters; and HOB parameters.

2.2.4.1 Weapon Yields and Types

These scenarios were predicated on assumed Hiroshima- and Nagasaki-type detonations of approximately 20-kt for the lowest yield class fission-based weapons, and it assumed 100- and 500-kt and 1-Mt yields for larger-sized detonations based on a sampling of open literature sources (DOE, 2015; Glasstone and Dolan, 1977; Mikhailov, 1996; SIPRI, 2020). Detonations have not been characterized as being either fission-based or thermonuclear weapons, as it is assumed to first order that explosion yield

and the resultant fireball characteristics are what provide the dominant thermal pulse that can ignite fires and generate strong air blasts that rubblize structures. The thermal radiation impinges on areas that have combustible fuel therein that can burn, such that thermal buoyancy from the generated fire’s heat flux uplifts a plume of smoke emissions long after the nuclear explosion has occurred (Glasstone and Dolan, 1977). This topic is addressed in detail in Chapters 3 and 4.

2.2.4.2 Target Type and Location Parameters

The committee assumed ex-urban targets (located away from cities, but with heavy industry, forested, agricultural, etc.) likely have lower fuel loading in the blast-damaged ignition zone than urban targets (in cities, but including some suburbs with military/industrial targets) that have higher fuel loading in the blast-damaged ignition zone (discussed further in Chapter 3). Some, but not all urban targets are considered soft targets that could be destroyed by higher so-called fallout-free HOBs with air blast as the predominant damage mode. A distinction is not drawn between point targets and area targets, or between desert and temperate target locations. Overlap in any of the ground-level nuclear weapon effects curves or footprints between nearby burst points is an area of uncertainty that would influence estimates of the amount of smoke produced (uncertainties are described and discussed in Chapter 3).

2.2.4.3 Height-of-Burst parameters

As with previous studies, it is assumed that airburst HOBs are optimal for maximizing the area of blast overpressures on the ground to do structural damage against “soft” targets, and which generally reduces the lofting of environmental materials and the effects of fallout (sometimes referred to as fallout-free HOBs). Harder targets generally require lower-altitude and surface bursts to “kill” them by stronger air blast effects. Some of the assumed hard targets in remote ex-urban locations (locations away from urban targets) require much lower HOB or ground-level bursts to damage them (Glasstone and Dolan, 1977).

2.2.5 Key Uncertainties and Data Gaps

Some of the associated uncertainties in the employment scenarios and assumptions above will likely affect the accuracy of modeling potential EENW.

The number of detonations for each plausible baseline weapon employment scenario above could be considerably lower in number based on an a priori unknown escalation ladder dynamic whereby one adversary may wish to terminate weapon use early. Alternatively, higher values would occur should each adversarial country decide to employ every weapon that is plausibly available to use. A scenario where use of weapons does not escalate—where very few or zero weapons are employed—would represent deterrence at work.

Temporal and geographic distribution of detonations are highly situationally dependent. It is unclear to what extent detonations minutes to hours or days to week apart would interact such that they amplify or dampen the impacts of ensuing fires. Relatedly, weather, time of day, and season can factor into tactical considerations and will likely affect the predicted climate impact.

There are many open questions regarding the way that the thermal ignition contours on the ground compare to the overpressure contours for a given yield detonation. These uncertainties lie with the aftermath of the HOB and how much effect that the blast wave that follows the thermal pulse have on the ignition and sustainment of fires. These fires may be instantaneously started by the prompt thermal pulse in certain target fuel loads/configurations.

As discussed below and in Box 2-2, Glasstone and Dolan (1977) provided what are still considered to be the authoritative weapon effects models. It is worth considering whether these empirical models are still appropriate to first order to estimate thermal, blast, fireballs, nuclear cloud dynamics, etc., or if there are more advanced and more accurate models (e.g., newer three-dimensional model

calculations using large-scale high-performance computers) that should be used or developed for determining damage and smoke production given a weapon detonation yield, HOB, location, and target set (see Finding 2-3, Recommendation 2-3).

As noted earlier, one might consider that a complementary report to the present study is that of Frankel et al. (2015). In discussing potential scenarios, the authors outline similar uncertainties with nuclear war planning and weapons employment:

- Design and yield of weapons,

- Strategic or tactical use,

- Accuracy or reliability,

- Height of burst,

- Weather,

- Topography.

As Frankel et al. (2015) write, “some answers to these questions are imponderable; others are likely to be better known to one side—generally the attacker—than to the other prior to nuclear weapons use. Many are evident to all after an attack has taken place.”

BOX 2-2

Perspective on the Use of The Effects of Nuclear Weapons by Glasstone and Dolan in This Study

The Glasstone and Dolan book on Nuclear Weapon Effects has been heavily used by researchers since it was published in 1977 as a source of authoritative technical data on nuclear weapon effects. Many of the effects models provided in the book, such as those for air blast, are empirical in nature and based on detailed test data measurements from past U.S. nuclear weapons tests, mostly during the atmospheric tests of the 1950s. Some models are based on theoretical one-dimensional physics-based models, such as those for thermal radiation effects. The empirical models describe a set of thresholds for general first-order blast and fire damage characteristics at the target as a function of range to the target. None of these simple models take into account three-dimensional effects that can significantly modify or attenuate the effect at the target. More detailed weapons effects information exists within controlled DoD and DOE/NNSA work areas, which over time are and can be made available for broader use, through established channels for identifying and releasing such information for broader use.

A few other earlier DoD released unclassified reports also used by researchers include Brode (1968), Defense Nuclear Agency (1972), and Office of Civil Defense (1967).

2.3 WEAPON EFFECTS AND ENERGY DISTRIBUTION

2.3.1 Overview of Weapon Effects

This section focuses on the effects from a nuclear detonation within the troposphere (the lower atmosphere, below about 12 km), including initial and residual nuclear radiation and a release of both thermal energy and kinetic energy that results in an air shock wave. These detonations release approximately 35% of their energy as thermal energy, while production of a strong air shock wave accounts for another 50% of the energy release. The remaining 15% of energy is released as initial prompt and residual radiation (Glasstone and Dolan, 1977), the effects of which are not examined in this report. The bomb components and environmental material within the expanding fireball are vaporized and form particulate matter as they cool, condense, and solidify. Thermal energy is transmitted through the atmosphere and can be of sufficient intensity to cause burns and ignite materials up to many kilometers away; however, the transport of thermal radiation can also be reduced or blocked by opaque materials, solid structures, terrain, or by transport through particle- or water-vapor-laden air. Shock waves travel

through the air and other materials, both heating them and causing an increase above atmospheric pressure at the shock front, known as “overpressure.” Heating of the air forms oxides of nitrogen (NOx), while the overpressure can cause structural damage that becomes a secondary source of fire ignitions. When weapons are detonated as surface bursts or low-altitude airbursts, the strong hydrodynamic shock and thermal effects from these detonations rubblize buildings and loft rock, soil and other matter near ground zero, which are then entrained and lofted farther by the thermally buoyant fireball, ultimately becoming a nuclear "mushroom" cloud that can contain a significant amount of material. In these cases, activated debris and fission products are highly radioactive. Much of this activity is on larger particles and deposits within the first 24 hours and is known as “local” fallout; however, smaller particles can stay aloft longer and are known as “global” fallout.

Nuclear clouds from the higher-yield weapons, that is, 100 kt to 1 Mt in these plausible scenarios,; have the potential to directly inject gases and particulates (bomb and entrained debris) into the stratosphere, where fine particulate matter can have a long lifetime and NOx can deplete ozone (O3) (Chapter 5). High-yield surface bursts may inject material from the fireball as mentioned above, as well as entrained material into the stratosphere; however, airbursts at the fallout-free height of burst or above do not entrain or loft significant amounts of surface material and only have the potential to inject gases and particulates from the detonation. For both surface bursts and airbursts (excluding high-altitude airbursts), interaction of thermal and kinetic energy with the ground surface is significant and can result in large fires and significant blast damage. Fires from the thermal effects and blast damage can generate significant emissions that are many times the mass of the material within a nuclear cloud. If these fires have sufficient intensity, they have the potential to inject the emissions into the upper tropopause or lower stratosphere. At these altitudes, soot in the fire emissions will be heated through absorption of solar radiation and will further loft air parcels whose volume will include other smoke aerosols and gases, in addition to the soot. These aerosols can block sunlight at Earth’s surface and have a long lifetime in the stratosphere, especially as lofting from solar heat absorption counteracts sedimentation (Chapter 5). Furthermore, heating of the surrounding atmosphere and heterogeneous chemistry will lead to destruction of ozone at some altitudes. The recent literature (from approximately 1985 onwards) on nuclear winter has been more concerned with fire emissions than those from the detonation. This is because as weapon yields have decreased over time, nuclear clouds are less likely to deposit significant masses of material in the stratosphere, meaning that large fires could inject much more aerosol mass into the stratosphere when compared to the mass entrained in a nuclear cloud. Additionally, aerosols that absorb sunlight, such as black carbon from fire emissions, are required for self-lofting. Finally, it is critical to note that fires can result from detonations in any of the scenarios, while only the largest-yield weapons (generally in the 100-kt to megaton class) have the ability to directly inject material from the detonation into the stratosphere (see Table 2-2).

Airbursts significantly above the blast-optimized HOB and high-altitude bursts will have limited surface interactions and are unlikely to cause fires or blast damage from overpressure. Detonations at these higher HOBs are not included in the employment scenarios, nor are underground or water bursts (detonations over water). While outside the scope of this study, high-altitude bursts remain a concern and are often referred to as high-altitude electromagnetic pulse attacks (DHS, 2025.; Malekos Smith, 2024).

2.3.2 Height of Burst

The plausible employment scenarios in Section 2.1 specify detonations to be airbursts at heights that minimize fallout or maximize blast effects, or surface bursts, used for damaging hardened targets. The so-called fallout-free height of burst (FFHOB) is the detonation height at which early fallout ceases to be a serious problem, such that the fallout is small enough to be tolerable under emergency conditions. The FFHOB is approximated by:

| H = 180 × W0.4, | Equation 2-1 |

where H is HOB in feet and W is the weapon yield in kilotons, (Glasstone and Dolan, 1977, eqn. 2.128.1). The FFHOB is included in Table 2-3 for the yields in the employment scenarios and range from 181.8 m for a 20-kt detonation to 869.5 m for a 1-Mt detonation.

TABLE 2-3 Example FFHOB Values for Weapon Yields in the Employment Scenarios

| Yield, kt | FFHOB, ft | FFHOB, m |

|---|---|---|

| 20 | 596.6 | 181.8 |

| 100 | 1,135.7 | 346.2 |

| 500 | 2,162.0 | 659.0 |

| 1,000 | 2,852.8 | 869.5 |

When the HOB is specified to optimize air blast effects, the HOB maximizes the area on the ground of a specified overpressure, which is generally chosen based on the target’s hardness. Below is an example calculation of the НОВ to maximize the area of 140 kPa (20 psi) overpressure, a level associated with heavy blast damage against structures. For reference, atmospheric pressure is 101.325 kPa (14.7 psi) and the overpressure discussed here is 140 kPa above atmospheric pressure. Data for peak overpressure is used in combination with scaling laws, following the procedure outlined by Glasstone and Dolan (1977), to calculate the НОВ required to maximize the area of peak overpressure. For a weapon with a 1-kt yield, an overpressure above 140 kPa can be obtained up to a distance of 280 m radially outward from the ground-zero location when the НОВ is 180 feet (see Glasstone and Dolan, 1977, fig. 3.73b). Values for alternative yields can be calculated using the scaling laws:

| d = d1ktW1/3, | Equation 2-2 | |

| HOB = HOB1kt W1/3, | Equation 2-3 |

where d is the distance from ground zero and W is the weapon yield, given the values d1kt and HOB1-kt for a 1-kt weapon. Table 2-4 provides the HOB required to maximize the area above 140 kPa overpressure at the surface and the resulting radial distance.

| Yield, kt | HOB, ft | HOB, m | Ground Range, km |

|---|---|---|---|

| 20 | 1,628.7 | 496.4 | 0.76 |

| 100 | 2,785.0 | 848.8 | 1.30 |

| 500 | 4,762.2 | 1,451.4 | 2.23 |

| 1,000 | 6,000.0 | 1,828.7 | 2.80 |

HOBs from these tables are used later in Section 2.3.4 for calculating the range of thermal effects. Corrections for meteorological conditions are available and may be needed, especially for larger yields where the shock wave will travel for significant distances in the atmosphere.

2.3.3 Gases and Particles from the Detonation

After a detonation, gases and debris particles can be lofted high into the atmosphere by the rising thermally buoyant cloud; however, detonations can also result in fires, whose plumes separately inject gases and aerosols into the atmosphere. Particles in the nuclear cloud that are directly from, or entrained by, the detonation itself, as opposed to being emitted by a resulting fire, are described in Box 2-3.

Airbursts with heights of burst that minimize fallout or optimize blast effects have fireballs with limited or no surface interactions, resulting in little mixing between particles in the cap and those lofted from the surface. This phenomenon was observed in the Hiroshima and Nagasaki nuclear (“mushroom”) clouds (see Figure 2-3). The cloud cap contains small particles, with diameters in the range of 0.01 to 20 µm, formed by the vaporized and resolidified bomb components, while condensed water causes the white color. The darker stem contains material with diameters ranging from sub-micron to millimeters lofted from the surface by the buoyant nuclear cloud. The observed air gap between the cap and stem illustrates the limited mixing between these two types of particles. In contrast, for a detonation near the surface, mixing between the debris particles from the weapon and particles entrained from the surface occurs quickly, and these particles are incorporated throughout the vertical extent of the debris cloud. Surface detonations are also capable of lofting significantly more entrained material mass into the atmosphere.

SOURCE: FEMA, 2022.

For reference, Peterson (1970) shows the approximate top and bottom of a stabilized nuclear cloud at equatorial and polar latitudes as a function of yield, though the final height will vary due to atmospheric conditions, entrained mass, and other factors. Although debris from a weapon with tens of kilotons yield is not expected to deposit a significant portion of the cloud in the stratosphere, clouds from larger weapons can penetrate the tropopause and deposit material directly in the stratosphere. In the event of a surface burst of a high-yield weapon, the injected debris mass could be significant. In addition to particles, heat from the thermal energy release and shock-heating of the air can produce NOx gases, which if introduced into the stratosphere can cause О3 loss (Johnston et al., 1973). The largest ozone loss is expected from detonations with yields of 10s of Mt, as those weapons have stabilized cloud heights that overlap the stratospheric ozone layer. As weapon yields have decreased, direct injection of nuclear cloud gases and particulates into the stratosphere has become less of a concern than in previous studies (e.g., the largest yield in the employment scenarios presented herein is 1 Mt), and climate modelers have shifted their concerns to the possible injection of particulates into the stratosphere from the fires following a nuclear detonation.

BOX 2-3

Radioactive Aerosol Formation Resulting from a Nuclear Detonation

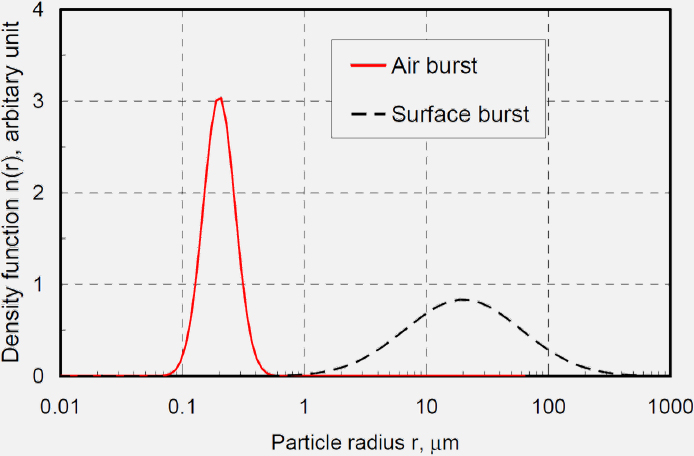

The particle size distribution of aerosols produced during detonation strongly contributes to potential long-term (weeks-to-decades) environmental effects following a nuclear weapons exchange. The initial size distribution affects the aerosol dynamics (nucleation, coagulation, sedimentation, and removal), optical properties, and interactions with solar radiation, which in turn determine the atmospheric residence time. Use of different aerosol particle size distributions in environmental impact models is a source of uncertainty that can lead to highly variable results in model simulations and assessments.

The high initial temperature within the fireball will cause complete vaporization of the constituents of the weapon, fissile materials, and part of the surrounding structures depending on the detonation scenario. Formation of particles by a nuclear detonation can be generally described as a two-stage process where spontaneous nucleation occurs first, and then gives way to condensation on existing particles. As the fireball temperatures decrease, initially by radiation, and subsequently by entrainment of cooler ambient air, the gas-phase constituents condense into droplets and particles within seconds after the detonation. The order in which these phase transformations occur is dictated by the intrinsic volatility of the species, their vapor concentration, and the existing condensed phase. The combination of the radioactive decay process and chemical kinetics leads to a temporal and spatial dependence of the composition of the system, thus affecting the level of supersaturation and the ability of the constituents of a given mass chain to condense. The rate of the initial phase transformation is also determined by the available material, as the saturation vapor pressure at the surface of particles will depend on their size and composition. These time-dependent condition changes in the fireball lead to an evolving population of debris particles described previously, with size-dependent compositions and distributions that can be multimodal.

The formation of particles from a nuclear detonation was described by Storebo (1974) as resulting from vaporized materials by nucleation, condensation, and coagulation. The size distribution was assumed to follow a lognormal function as Eq. (2-4):

Equation 2-4

where N is the particle density as a function of particle diameter, Dp, µ is the geometric mean diameter, and σ is the geometric standard deviation of the size distribution. The µ and σ were estimated to be 0.4 µm and 1.35, respectively for the Hiroshima bomb cloud particles (Imanaka, 2012; Nathans et al., 1970).

Investigation of radioactive aerosol particle size distributions from nuclear weapon tests based оn the detonation yield and НОВ led to two distinct types of particle populations and therefore separate distributions (Heft, 1970). These two types of aerosol populations are:

(1) The radioactive particle population consisting of environmental materials introduced into the fireball as preexisting particles. These may be completely or partially melted, but if vaporized, they do not reappear as an identifiable part of the particle population.

Land surface bursts, including tower burst tests, produced this type of particle population. These types of particles have a size range from a few tens of micrometers to thousands of micrometers (i.e., millimeters).

(2) The radioactive particle population consisting of metal oxide spheres formed by condensation from the vapor state of metallic constituents of the detonated device.

This type of particle population generally lies in the 10-nm to 20-µm range and is produced by airbursts. Density is generally in the range of metal oxides of condensable materials vaporized by the detonation.

A bimodal lognormal distribution has also been suggested to describe the particle population in a nuclear cloud (Baker, 1987). One distribution was attributed to bomb materials (from high-temperature history) and the other to unmelted or partially melted (low-temperature history) surface materials. Once the aerosol particles were

formed in the thermal processes immediately after detonation, the size distribution of particles stayed constant in time. Aggregation or agglomeration process on the particles was insignificant. Figure 2-5 shows an illustrative bimodal distribution of radioactive aerosol particles produced by a nuclear detonation; it is not representative of the mass of each source, as an airburst would have a very small overall mass of particles compared to that of a surface burst.

SOURCE: Imanaka, 2012.

Researchers have assessed whether the gases or particles that are directly injected into the stratosphere have the potential to cause climate impacts through either the destruction of ozone or attenuation of sunlight, a topic that will be also addressed later in the report (Chapter 5). Stratospheric heating due to the presence of soot emitted by fires, which absorbs solar radiation, and changes to stratospheric chemistry are additional causes of О3 loss, along with changes to atmospheric transport and circulation patterns (Kao et al., 1990), and reactions with NOx emitted by the fire. Bardeen et al. (2021) used a global earth system model to examine the effects of soot emissions alone and in combination with NOx formed by both the fireball and fire. Soot emissions dominated their calculated large stratospheric ozone losses, with a peak global average loss of 25% for a regional (India and Pakistan) nuclear war scenario with 5 Tg of stratospheric soot loading and 75% for a global (U.S. and Russia) war scenario with 150 Tg of stratospheric soot (Bardeen et al., 2021). The additional NOx emissions had a smaller relative effect on stratospheric ozone loss in the regional scenario, while in the global scenario, they resulted in a 5% increase in ozone loss for the first 3 years. In these studies, losses were primarily due to the presence of soot and heating from its absorption of solar energy, not from NOx emissions that are transported to the stratosphere. Furthermore, in both the regional and the global scenarios most of the NOx emissions were attributed to fire emissions, not the nuclear fireball. However, more recent studies on the chemistry of wildfire smoke have identified additional ozone depletion mechanisms involving organic aerosols; these have not yet been included in nuclear war simulations. A detailed discussion is available in Chapter 5.

Researchers have also investigated whether the nuclear cloud can inject enough surface debris into the stratosphere to attenuate sunlight. The 1985 NRC report estimated that a nuclear cloud from a surface burst has the potential to entrain 0.2 to 0.5 Tg of debris per megaton of weapon yield (NRC,

1985), an amount consistent with current fallout models. The expected mass of debris injected into the stratosphere can be determined by considering the number of surface bursts, the weapon yield, the percent of the stabilized cloud injected in the stratosphere, and the percentage of the particle size distribution in the submicron range. Following analysis consistent with the NRC (1985) report, the large-scale scenario described in Section 2.2.2 could inject 5 to 12.5 Tg of submicron particles in the stratosphere, while the moderate-scale exchange has the potential to inject 0.5 to 1.25 Tg. The regional and limited exchanges are not expected to inject debris into the stratosphere due to the lower yields and thus lower stabilized cloud heights. Glasstone and Dolan (1977) note that for radioactive debris particles in the lower stratosphere, below 70,000 ft (~21 km), the observed half-residence time is 10 months. Notably, this residence time is in the absence of fire emissions and soot, which could cause further lofting of air parcels and particles.

2.3.4 Thermal Radiation Effects

Fires occurred after the detonations in Hiroshima and Nagasaki, caused by both direct ignition of materials from thermal radiation and from secondary ignitions due to structures and local infrastructure damaged by the shock wave and blast, for example from broken gas lines and damaged electrical equipment. Thermal (radiant) exposure (Q, cal/cm2) can be calculated by considering the spread of energy as it expands in a sphere of area 4πD2 (where D is the distance from the explosion, often called the “slant range”) and the attenuation in the atmosphere during transport. As the thermal energy spreads outward over the area of the growing sphere, the magnitude decreases as the inverse of the distance squared, so that the thermal energy at a point 2 km from the detonation source will experience one-fourth of the radiant exposure of a point at a 1-km distance. Attenuation during transport over this distance is due to absorption and scattering in the atmosphere, later represented by the transmittance, τ (i.e., the fraction of thermal radiation transmitted).

Ignition of material due to impinging radiant exposure is dependent on the material properties, including thickness, moisture content, albedo, etc. Exposure time is also a consideration, and the duration of the thermal pulse is related to the yield. The effective thermal pulse is the time at which 80% of the thermal energy has been emitted, which is about 10 times longer than the time of the maximum power output (tmax). The duration of the thermal pulse for surface bursts and airbursts below 15,000 ft (4,572 m) can be calculated as t = 0.417 W0.44 seconds, where W is the weapon yield in kilotons (Glasstone and Dolan, 1977, section 7.85). Thermal pulse durations for weapon yields in the employment scenarios are provided in Table 2-5.

TABLE 2-5 Duration of Thermal Pulse

| Yield, kt | Duration of Thermal Pulse, s |

|---|---|

| 20 | 1.6 |

| 100 | 3.2 |

| 500 | 6.4 |

| 1000 | 8.7 |

Ignition of material following a nuclear detonation is generally associated with the radiant exposure, but ignition is a complex process that includes other factors including the critical, material, environmental specific conditions along with ambient temperature, presence of moisture, the duration of the heat exposure, and other factors. Focusing on radiant exposure as a nuclear effect for this chapter, Tables 7.35 and 7.40 in Glasstone and Dolan (1977) provide approximate radiant exposures required for the ignition of various materials considering the length of the thermal pulse at three different weapon yields, ranging from 35 kt to 20 Mt. For example, referring to radiant exposure, flaming in Douglas fir plywood is expected at a radiant exposure level of 9, 16, or 20 cal/cm2 for a 35-kt, 1.4-Mt, or 20-Mt

detonation, respectively. This dependence on yield is due to the rate at which the energy is delivered. A higher-yield weapon with a longer thermal pulse will deliver the energy over a longer duration, meaning the exposure level must be higher to obtain a given thermal response in a material.

Radiant exposure from an airburst is expressed by the following equation:

| Q = fWτ/4πD2 | Equation 2-5 |

where Q is the radiant energy, f is the thermal partition factor (0.35 for HOBs less than 15,000 feet or approximately 4.6 km), W is the yield in kilotons, τ is transmittance, and D is the slant range (Glasstone and Dolan, 1977, eqn. 7.96.1). The slant range for a given radiant exposure level cannot be calculated directly from this equation because the transmittance is also a function of slant range. Figure 2-5 plots the slant range (D) as a function of weapon yield for radiant exposure levels ranging from 3 to 50 cal/cm2 as calculated for airbursts (HOB = 200 W0.4 ft).

SOURCE: Glasstone and Dolan, 1977.

The surface area subject to a specified minimum radiant energy level, and thus the possible area of fire ignition for a given material, can be calculated by combining the radiant energy curves with a simple geometry. The Pythagorean theorem can be used to calculate the ground range, given the НОВ and the slant range for a specified radiant energy level. Table 2-6 provides example values of the ground range and ground area exposed to 12 cal/cm2, a value chosen due to its being the highest value on the plot, for the yields in the employment scenarios. In reference to this value of Q, 5 cal/cm2 corresponds to the fires in Hiroshima; however, 12 cal/cm2 is more commonly used by researchers as the higher value corresponds to modern urban settings. Glasstone and Dolan (1977) note that thevalues in Table 2-6 are generally appropriate for airbursts with HOBs greater than 180W0.4 ft and below 15,000 ft. Ignition criteria for a fire could be higher or lower than 12 cal/cm2 depending on the fuel and conditions.

TABLE 2-6 Ground Range and Area Where Q Is Greater than 12 cal/cm2 for a Range of Weapon Yields Detonated as Airbursts as Determined from Figure 2-5a

| Yield (kt) | Ground Range (km) | Ground Area (km2) |

|---|---|---|

| 20 | 2.1 | 13.3 |

| 100 | 4.1 | 52.7 |

| 500 | 7.9 | 194.2 |

| 1000 | 10.2 | 326.0 |

NOTES: There is a trend with the values that should be mentioned, the smaller yield weapons more are more efficient with the fire ignition are per unit of yield ranging from 0.66 km2/kt for a 20 kt weapon to 0.33 km2/kt for the 1000 kt weapon.

a Figure 2-5 is the same as fig. 7.4.2 in Glasstone and Dolan (1977).

In a surface burst, the thermal energy at a specified distance is expected to be one-half to three-fourths of that from an airburst. The reduction is due to lower transmittance at the surface where the air is denser and is also expected to be more heavily laden with material after a surface burst. For surface bursts, it is suggested that the thermal partition f is reduced from 0.35 to 0.18 to compensate for these factors.

The ability for a fire to start and spread will be dependent on the fuel type, condition, and density in the vicinity of the fire start locations, as well as on the atmospheric conditions. Conflagrations can spread if there is sufficient fuel; however, under certain conditions fires can merge into a mass fire or firestorm. Glasstone and Dolan (1977) note that a density of at least 3.9 g/сm2 (8 lb/ft2) of combustibles is required to support a firestorm, along with fire in more than half of the structures, low windspeeds (less than ~3.58 m/s), and a minimum area of combustible material of at least 1.3 km2 (0.5 mi2), which are unlikely to be present in all scenarios.

2.3.5 Blast and Shock Effects

Kinetic energy from the detonation forms a shock wave that damages structures as it travels radially outward from the blast location. Figure 2-6 shows the expected light, moderate, and severe damage zones for surface bursts at various weapon yields (FEMA, 2022). In the severe damage zone, most buildings will sustain substantial damage. In the moderate damage zone heavy structures may remain intact, while light structures are destroyed. In the light damage zone broken glass and flying debris are expected.

SOURCE: FEMA, 2022.

From the perspective of examining environmental effects of a detonation, it is important to understand the role of the shock on fire ignition and propagation; however, this role is complex and highly uncertain. In most detonations the ground area of potential fire ignition will be larger than the area of rubblized buildings. Most thermal energy propagates from the weapon in advance of the shock wave, such that there is the possibility that the passing shock wave can extinguish fires, but it can also leave behind smoldering debris from which fires can grow, the nature of which is found in Chapter 3. Damage to structures and surrounding infrastructure (e.g., electrical equipment, gas lines, and other sources of fuel) within the blast region can also be a source of fire starts and it was estimated that after the detonation in Hiroshima, more than half of the fires were due to indirect fire starts (i.e., not due to thermal output from the weapon). Damage within the blast radius will also affect the ability of a fire to spread, with additional dependency on construction type and materials. In some cases, blast damage can make structures more susceptible to fire spread by damaging fire-resistive construction elements, while in other cases damaged buildings and rubble burned more slowly than expected. Although fires occurred after the detonations in Hiroshima and Nagasaki, it is not well understood what role blast effects played in fire spread after the detonations.

2.3.6 High-fidelity Models for Prompt Weapons Effects

Current studies of climate effects from nuclear detonations rely on empirical models for the ground range of thermal radiation effects when determining the possible area of fire ignition after a detonation. These models were developed for flat terrain and are inaccurate when applied within complex or urban terrain and when atmospheric conditions (e.g. visibility) vary from the observations used in development of the empirical model. Three-dimensional models, capable of accounting for the effects of complex and urban terrain, exist for prompt effects, but are rarely used due to the increased computational expense, required expertise in running the model, and limited availability of the models. However, three-dimensional models will give more accurate results for a broader range of scenarios and employment conditions.

Incident energy on the urban terrain of San Francisco is shown in Figure 2-7 (from Marrs et al., 2007) for a 10 kt detonation near the surface (top) and as an airburst (bottom). Importantly, the yellow dashed line indicates a contour level of 5 cal/cm2 when terrain effects are not considered. By viewing the difference between the yellow dashed line and the extent of the yellow surface shading, this figure illustrates the much-reduced ground area subject to a given level of radiant energy when shielding from the urban terrain is considered. The area subject to fire starts is expected to substantially decrease when higher-fidelity models are used for prompt effects modeling in urban environments, indicating that the fire area used in current climate effects studies may be overestimated. As mentioned in the conclusions for this study, however, “adjacent buildings and device emplacement could affect the early fireball and its thermal radiation. Although there is no accurate model for these effects, the additional mass and debris from an enclosed burst reduce the radiated thermal energy compared to a free air burst. Attenuation by fog, rain, and haze could be important at distances greater than the visibility range. In some cases, reflection from buildings and clouds could contribute significant heat to areas that are shielded from direct radiation” Marrs et al. (2007).

2.3.7 Key Uncertainties and Data Gaps

Extant studies related to the environmental effects of nuclear warfare reflect a limited number of use scenarios, with each scenario being limited to specific actors and attendant numbers, types, and capabilities of their nuclear forces. These scenarios also make specific assumptions related to nuclear weapon employment strategies. The effect of exploring only a limited range of employment scenarios is likely to produce incomplete conclusions.

SOURCE: Marrs et al., 2007.

For example, the number and characteristics of nuclear weapon systems have changed substantially since the first EENW studies of the mid-1970s and 1980s in that more nations possess nuclear weapons (India, Pakistan, and North Korea, in addition to China, the UK, and France, now have nuclear weapons). The U.S. and Russian stockpile sizes have notably decreased, and technological advances have led to improved delivery system accuracy. These advances enabled a commensurate reduction in warhead yields needed to achieve military objectives. These improvements in the precision–yield relationship also enabled refinements in nuclear policy strategies. Updated information presented in this report provides a basis for a more up-to-date set of scenarios. Note that emerging nuclear weapon states have greatly increased their current number of warheads; however, these numbers are still dwarfed by the absolute number of warheads at the height of the Cold War.

Thermal energy is attenuated by the atmosphere as it travels from the point of detonation to potential fuel sources, such as built-up areas. The atmosphere absorbs and scatters the thermal radiation, which will depend on the presence of moisture and particles in the air. Shielding fгom terrain and other objects is also expected to affect the transport of the thermal radiation.

Discussed in greater detail in Chapter 3, materials in areas at risk for fire will be highly variable. These diverse materials will require varying amounts of thermal energy to ignite. The thermal flux required to start fires is uncertain and the role of secondary ignitions (those from sources other than the thermal energy of the detonation) is not well characterized or quantified.

The role of blast waves in the development of a fire is not well understood. Most thermal radiation reaches material in advance of the blast wave. The blast can extinguish flames but can also leave smoldering material and rubble, which can grow into larger fires. Blast waves can cause damage that results in secondary ignitions, thus being an additional source of fire starts. The way in which blast-damage affects fire-resistive construction has been shown to be variable.

Terrain effects, building density, and meteorological conditions are often cited as the reasons for the differing fire outcomes in Hiroshima and Nagasaki. The fire in Hiroshima consumed an area of approximately 11.4 km2 (4.4 mi2), 4 times greater in size than the fire in Nagasaki. The extent and characterization of the fire damage at Hiroshima and Nagasaki are notably different Within the city limits at Hiroshima, 92% of all the buildings were damaged or destroyed, with 63% completely destroyed and burned, 24% partially destroyed and burned, and only 5% completely destroyed (without notable fires) (Ishikawa and Swain, 1981). The comparable numbers at Nagasaki were 36%, 23%, 11% and 3%, respectively. Fires were believed to have been started primarily by the ignition of thin fuels, such as paper and fabric, and then spreading within a structure. However, it is not known what the importance was of direct and secondary ignitions, respectively, or if blast damage hindered or helped the fire starts and spread.

The spread of fires will depend on weather, combustibility of the material and buildings, fuel or building density, discussed further in Chapter 3. An additional consideration could be blast damage and the rubblization of the materials.

Scaling laws for the blast waves are developed for flat terrain. Outside of these idealized conditions, terrain will increase blast effects in some areas, while decreasing the effects in others (shielding behind terrain features should not be expected for blast effects). Interactions between meteorological conditions and blast waves can occur. Glasstone and Dolan (1977) cite inversions, high-speed winds, an ozonosphere, and high temperatures in the ionosphere. The blast wave can also be modified by the presence of material, primarily increasing the dynamic pressure due to the increase in material loading over that of an idealized atmosphere.

2.4 SUMMARY

This chapter proposes four general scenarios, to provide a baseline for researchers and stakeholders to build from in future nuclear war scenario analyses and climate modeling. These four scenarios are based on the current estimated and cited nuclear stockpiles available to the nuclear weapon countries. The scenarios proposed are defined by the number of nuclear warheads exchanged in descending order and titled large-scale exchange (2,000 warheads), moderate (400), regional (150), and limited (1). The numbers and yield ranges of weapons are again based on reasonable approximations of the estimated and cited worldwide nuclear stockpile inventories, and the distribution between urban and ex-urban targets is similar to earlier reports acknowledging a range of strategic and military targets. The number of detonations feed into the following chapters as source terms for fires and the resulting effects of these fires. Numerous uncertainties are summarized in the chapter including location, number, yield, HOB, timing, and weather. One of the key takeaways is that future climate modeling efforts to predict environmental effects could include better and more representative scenarios by utilizing such resources as war-gaming exercises, including perspectives from military experts and policymakers.

Following the development and presentation of the nuclear exchange scenarios, this chapter subsequently describes the effects of nuclear detonations, and in particular the thermal radiation that can ignite combustible material and the blast wave that can destroy buildings. Information on the immediate atmospheric effects is noted as well. Much of this information is derived from Glasstone and Dolan (1977) in preparing this report as it leads into Chapter 3 and the description of the fires arising from nuclear weapons detonation.

2.5 FINDINGS AND RECOMMENDATIONS

FINDING 2-1: Studies reflecting very large exchanges of tens of thousands of warheads with multi-megaton yields are no longer reflective of current worldwide nuclear stockpiles. In the same vein, scenarios that reflect an informed mix of nuclear weapon employment on both targets within urban areas and military targets outside urban areas, versus only in urban areas, would likely better reflect military strategies and outcomes.

RECOMMENDATION 2-1: The National Nuclear Security Administration should empanel appropriate experts to employ stochastic modeling and war games to produce a more comprehensive set of plausible scenarios and input for subsequent environmental modeling and make the set of scenarios available for the EENW research community, enabling use of a realistic range of employment scenarios to support a more complete understanding of potential environmental effects.

FINDING 2-2: Some extant studies of weapon exchange scenarios have assumed that up to 100% of an adversaries’ nuclear weapons stockpile would be employed against the other country. Given historical military behaviors, employment of 100% of a large stockpile is unlikely; therefore, an employment assumption of closer to 50% of an adversary’s stockpile is more plausible from a military strategy perspective and is consistent with past National Research Council studies.

RECOMMENDATION 2-2: EENW researchers should use a representative understanding, from military experts and policymakers, of a reasonable range in percentages of each adversary’s nuclear weapons stockpile that could be used in different exchange scenarios.

FINDING 2-3: Most available weapon effects models are based on empirical formulas derived from limited data from earlier weapon tests or from simple theoretical one-dimensional physics-based constructs. These models are highly idealized, neglecting important effects from topography and structures, and likely overpredict the ground range of single-weapons effects for realistic use cases, especially those in urban areas or complex terrain. Furthermore, these models predict primary ignitions and need to be combined with models of secondary ignitions and fire spread for improved prediction of fire damage.

RECOMMENDATION 2-3: EENW researchers should develop and validate high-fidelity, three-dimensional models designed to generate greater spatial and temporal resolution of nuclear weapon effects, to better understand fire ignition and spread, as well as the role of secondary ignitions, concomitant with the impacts of air blast and thermal weapons effect on a range of natural and built environments.

2.6 REFERENCES

Arms Control Association. 2022. U.S.-Russian Nuclear Arms Control Agreements at a Glance. from https://www.armscontrol.org/factsheets/us-russian-nuclear-arms-control-agreements-glance.

Baker, G. H., III. 1987. Implications of Atmospheric Test Fallout Data for Nuclear Winter. Air Force Institute of Technology, Wright-Patterson AFB, OH. PhD: 183.

Bardeen, C. G., D. E. Kinnison, O. B. Toon, M. J. Mills, F. Vitt, L. Xia, J. Jägermeyr, N. S. Lovenduski, K. J. N. Scherrer, M. Clyne, and A. Robock. 2021. Extreme Ozone Loss Following Nuclear War Results in Enhanced Surface Ultraviolet Radiation. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 126(18):e2021JD035079. https://doi.org/10.1029/2021JD035079.

Brode, H. L. 1968. Review of Nuclear Weapons Effects. Annual Review of Nuclear and Particle Science 18(18):153-202. 10.1146/annurev.ns.18.120168.001101.

Carter, A. B., J. D. Steinbruner, and C. A. Zraket, eds. 1987. Managing Nuclear Operations. Washington, DC: Brookings Institution Press.

CACNP (Center for Arms Control and Non-Proliferation). 2019a. Fact Sheet: Pakistan’s Nuclear Inventory. Dated August 29, 2019. (Updated May 2025.) https://armscontrolcenter.org/pakistans-nuclear-capabilities/.

CACNP. 2019b. Factsheet: Escalating Tensions over Kashmir. August 29, 2019. (Updated December 2024). https://armscontrolcenter.org/escalating-tensions-over-kashmir/.

CACNP. 2020a. Fact Sheet: France’s Nuclear Inventory. Dated March 27, 2020. https://armscontrolcenter.org/fact-sheet-frances-nuclear-arsenal/.

CACNP. 2020b. The United States’ Nuclear Inventory. Dated July 2, 2020. https://armscontrolcenter.org/fact-sheet-the-united-states-nuclear-arsenal/.

CACNP. 2020c. Fact Sheet: The United Kingdom’s Nuclear Inventory. Dated April 22, 2020. (Updated July 2021). https://armscontrolcenter.org/fact-sheet-the-united-kingdoms-nuclear-arsenal/.

CACNP. 2020d. Fact Sheet: China’s Nuclear Inventory. Dated April 2, 2020. (Updated December 2024). https://armscontrolcenter.org/fact-sheet-chinas-nuclear-arsenal/.

CACNP. 2021a. Factsheet: North Korea’s Nuclear Inventory. Dated May 20, 2021. (Updated September 2022). https://armscontrolcenter.org/fact-sheet-north-koreas-nuclear-inventory/.

CACNP. 2021b. Fact Sheet: India’s Nuclear Inventory. Dated August 29, 2019. (Updated May 2025). https://armscontrolcenter.org/indias-nuclear-capabilities/. CACNP. 2019b. Escalating Tensions over Kashmir.

Defense Nuclear Agency. 1972. Capabilities of Nuclear Weapons. Defense Nuclear Agency Effects Manual Number 1 (EM-1 Manual). Washington D.C.

DHS (Department of Homeland Security). 2025. Electromagnetic Pulse (EMP) / Geomagnetic Disturbance (GMD). Retrieved July 29, 2024, 2024, from https://www.dhs.gov/science-and-technology/electromagnetic-pulse-empgeomagnetic-disturbance.

DOS (Department of State). 2024. Transparency in the U.S. Nuclear Weapons Stockpile. from https://2021-2025.state.gov/transparency-in-the-u-s-nuclear-weapons-stockpile-2/.

DoD (U. S. Department of Defense). 2023. Military and Security Developments Involving the People’s Republic of China 2023 Annual Report to Congress. https://media.defense.gov/2023/Oct/19/2003323409/-1/-1/1/2023-military-and-security-developments-involving-the-peoples-republic-of-china.pdf.

DOE (Department of Energy). 2015. United States Nuclear Tests, July 1945 through September 1992, September 2015. United States: Las Vegas, Nevada.

FEMA (Federal Emergency Management Agency). 1987. Attack Environment Manual: Chapter 5 - What the Planner Needs to Know About Initial Nuclear Radiation. Federal Emergency Management Agency.

FEMA. 2022. Planning Guidance for Response to a Nuclear Detonation. 3rd Edition. Version June 12, 2023. https://www.fema.gov/sites/default/files/documents/fema_nuc-detonation-planning-guide.pdf

Fink, A. S. 2024. Russia’s Nuclear Weapons. Washington, DC: Congressional Research Service.

Frankel, M. J., J. Scouras, and G. W. Ullrich. 2015. The Uncertain Consequences of Nuclear Weapons Use. NSAD-R-15-020. Laurel, Maryland: The Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory.

Friedman, U. 2019. The New Concept Everyone in Washington is Talking About. The Atlantic.

Gill, Bates. Meeting China’s Nuclear and WMD Buildup. NBR Special Report #109, The National Bureau of Asian Research, May 2024. https://www.nbr.org/wp-content/uploads/pdfs/publications/sr109_meeting_chinas_nuclear_and_wmd_buildup_may2024.pdf.

Glaser, C., A. Long, and B. Radzinsky, eds. 2022. Managing U.S. Nuclear Operations in the 21st Century. Washington, DC: Brookings Institution Press.

Glasstone, S., and P. J. Dolan. 1977. The Effects of Nuclear Weapons. TID-28061; TRN: 78-014841. United States: United States Department of Defense and the United States Department of Energy. DOI: https://doi.org/10.2172/6852629.

Heft, R. E. 1970. Characterization Of Radioactive Particles From Nuclear Weapons Tests. Radionuclides in the Environment 93:254-281. 10.1021/ba-1970-0093.ch014.

Horovitz, L., and L. Wachs. 2023. France’s nuclear weapons and Europe: Options for a better coordinated deterrence policy. Stiftung Wissenschaft und Politik (SWP), German Institute for International and Security Affairs. https://doi.org/10.18449/2023C15.

Ishikawa, E. and Swain, D.L. trans. 1981. Hiroshima and Nagasaki: The Physical, Medical, and Social Effects of the Atomic Bombings. New York: Basic Books.

Imanaka, T. 2012. Initial process of the nuclear explosion and cloud formation by the Hiroshima atomic bomb. IPSHU English Research Report Series (28):10-17. https://doi.org/10.15027/33619.

Johnston, H., G. Whitten, and J. Birks. 1973. Effect of nuclear explosions on stratospheric nitric oxide and ozone. Journal of Geophysical Research (1896-1977) 78(27):6107-6135. https://doi.org/10.1029/JC078i027p06107.

Kao, C.-Y. J., G. A. Glatzmaier, R. C. Malone, and R. P. Turco. 1990. Global three-dimensional simulations of ozone depletion under postwar conditions. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 95(D13):22495-22512. https://doi.org/10.1029/JD095iD13p22495.

Koch, S. J. 2018. The Presidential Nuclear Intiatives of 1991-1992. Toda Peace Institute.

Kristensen, H. M., and R. S. Norris. 2015. Russian Nuclear Forces, 2015. Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists 71(3):84-97. https://doi.org/10.1177/0096340215581363.

Kristensen, H. M., and M. Korda. 2020. Russian nuclear forces, 2020. Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists 76(2):102-117. https://doi.org/10.1080/00963402.2020.1728985.

Kristensen, H. M., and M. Korda. 2021. United Kingdom nuclear weapons, 2021. Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists 77(3):153-158. https://doi.org/10.1080/00963402.2021.1912309.

Kristensen, H. M., and M. Korda. 2022a. Indian nuclear weapons, 2022. Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists 78(4):224-236. https://doi.org/10.1080/00963402.2022.2087385.

Kristensen, H. M., and M. Korda. 2022b. North Korean nuclear weapons, 2022. Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists 78(5):273-294. https://doi.org/10.1080/00963402.2022.2109341.

Kristensen, H. M., M. Korda, and E. Reynolds. 2023a. Russian nuclear weapons, 2023. Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists 79(3):174-199. https://doi.org/10.1080/00963402.2023.2202542.

Kristensen, H. M., M. Korda, and E. Johns. 2023b. French nuclear weapons, 2023. Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists 79(4):272-281. https://doi.org/10.1080/00963402.2023.2223088.

Kristensen, H. M., M. Korda, and E. Johns. 2023c. Pakistan nuclear weapons, 2023. Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists 79(5):329-345. https://doi.org/10.1080/00963402.2023.2245260.

Kristensen, H. M., M. Korda, E. Johns, and M. Knight. 2024. Chinese nuclear weapons, 2024. Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists 80(1):49-72.

Lieber, K. A., and D. G. Press. 2023. US Strategy and Force Posture for an Era of Nuclear Tripolarity. Atlantic Council.

Malekos Smith, Z. L. 2024. The Specter of EMP Weapons in Space - U.S. Global Engagement Initiative. Carnegie Council for Ethics in International Affairs.

Marrs, R. E., W. C. Moss, and B. Whitlock. 2007. Thermal Radiation from Nuclear Detonations in Urban Environments. Livermore, California: Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory. https://doi.org/10.2172/912675.

Mikhailov, V. N. 1996. USSR Nuclear Weapons Tests and Peaceful Nuclear Explosions: 1949 through 1990.

Miles, M. D., and C. R. Miller. 2019. Global Risks and Opportunities: The Great Power Competition Paradigm. Joint Force Quarterly 3rd Quarter (94):80-85. https://ndupress.ndu.edu/Media/News/News-Article-View/Article/1913010/global-risks-and-opportunities-the-great-power-competition-paradigm/.

Mills, C. 2024. Nuclear Weapons at a Glance: United Kingdom. House of Commons Library. https://commonslibrary.parliament.uk/research-briefings/cbp-9077/.

Nathans, M. W., R. Thews, W. D. Holland, and P. A. Benson. 1970. Particle size distribution in clouds from nuclear airbursts. Journal of Geophysical Research (1896-1977) 75(36):7559-7572. 10.1029/JC075i036p07559.

NFPA (National Fire Protection Association). 2021. NFPA 921, Guide For Fire And Explosion Investigations National Fire Protection Association.

Nikitin, M. B. D. 2023. North Korea’s Nuclear Weapons and Missile Programs [July 21, 2023]. Congressional Research Service.

NNSA (National Nuclear Security Administration). 2024. Transparency in the U.S. Nuclear Weapons Stockpile.

NRC (National Research Council). 1975. Long-Term Worldwide Effects of Multiple Nuclear-Weapons Detonations. Washington, DC: National Academy Press.

NRC. 1985. The Effects on the Atmosphere of a Major Nuclear Exchange. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. https://doi.org/10.17226/540.

Norris, R. S., and H. Kristensen. 2010. Global nuclear weapons inventories, 1945-2010. Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists July/August 2010. https://doi.org/10.2968/066004008.

Office of Civil Defense. 1967. Nuclear Weapons Effects: Self Teaching Materials. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office.

Peterson, K. R. 1970. An Empirical Model for Estimating World-Wide Deposition from Atmospheric Nuclear Detonations. Health Physics 18: 357-378. https://doi.org/10.1097/00004032-197004000-00007.

Rai, A. 2024. The Alarming Numbers Behind North Korea’s Growing Nuclear Arsenal.

Savoy, C., and J. Staguhn. 2022. Global Development in an Era of Great Power Competition. Center for Strategic & International Studies, CSIS.org.

SIPRI (Stockholm International Peace Research Institute). 2020. SIPRI Yearbook 2020: Armaments, Disarmament and International Security: Oxford University Press.

Spriggs, G. D., S. J. Neuscamman, J. S. Nasstrom, and K. B. Knight. 2020. Fallout Cloud Regimes. Countering WMD Journal (21).

Storebo, P. B. 1974. Formation of radioactivity size distributions in nuclear bomb debris. Journal of Aerosol Science 5(6):557-577. https://doi.org/10.1016/0021-8502(74)90117-7.