Potential Environmental Effects of Nuclear War (2025)

Chapter: Summary

Summary

At the outset of the Cold War era, the United States and the Soviet Union rapidly built up large nuclear arsenals as part of the prevailing doctrine of deterrence, under which each nation attempted to amass enough destructive nuclear capability to discourage the other from ever using their weapons first, out of fear of prompting a catastrophic retaliatory attack. As stockpiles of nuclear arms grew larger and more destructive, however, public concerns escalated over the potentially devastating humanitarian, environmental, and societal consequences of a future nuclear war. These mounting concerns spurred diplomatic initiatives to prevent further proliferation of nuclear weapons, limit weapons development and deployment, and restrict nuclear testing. In addition, pioneering scientific research sought to understand and assess the broader and longer-term impacts of potential nuclear wars beyond the immediate effects of nuclear detonations themselves.

A series of major scientific studies conducted in the 1980s issued warnings about the potential for a “nuclear winter” scenario—in which the immense firestorms ignited by a large-scale nuclear exchange between the superpowers might inject massive amounts of light-blocking soot and particulates into the upper atmosphere. It was projected that sufficiently high levels of these particles could reduce incoming sunlight for long enough to cause global cooling effects that could disrupt agriculture and ecosystems worldwide for several years. A key implication of this research was that virtually every country would be impacted regardless of involvement in the conflict. While negotiated frameworks such as the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty have succeeded in limiting the growth of global nuclear stockpiles, concerns about potential undeclared nuclear programs in some signatory states persist. Moreover, the emergence of multiple minor nuclear powers has raised the possibility of smaller, regionalized nuclear conflicts.

In the more than 35 years since the “nuclear winter” concept first emerged, there have been profound military, political, and technological shifts in the nuclear landscape, as well as significant advances in the scientific understanding of, and ability to model, Earth system processes. These developments have raised questions about many of the key assumptions underlying earlier projections of the impacts of nuclear war. They have also created an opportunity to pose new research questions that can explore novel nuclear war scenarios, integrate improved understandings of physical and natural processes, and consider more diverse pathways connecting nuclear weapons employment to the harm experienced by ecosystems, people, and society.

It is in this context that the U.S. Congress, through the National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2021, called for a study that would comprehensively reevaluate the scientific understanding of the longer-term and broader impacts of nuclear wars. The formal Statement of Task called for the expert committee to author a report providing an authoritative, independent review of the potential environmental effects and societal and economic consequences that could unfold in the weeks to decades after various scenarios of nuclear war—ranging from small regional exchanges to larger-scale nuclear wars between major powers. Importantly, an evaluation of the effects of radioactive fallout was not included in the scope of the work.

The study itself was structured into two phases. The first phase required access to classified information to evaluate the computer modeling of “source terms” describing the particulate emissions expected from nuclear detonations and their resultant fires. The second, unclassified, phase reviewed the scientific understanding across the full sequence of cause and effect, or “causal pathway,” that could connect the weapons employment scenarios to their impacts across natural and human systems.1 For this

___________________

1 In the context of this report, a “system” refers to a set of interacting elements that can be physical, biological, social, or economic in nature, and which function together as a larger whole. A key attribute of the various systems described in this report (such as the climate system or an ecosystem or societal system), is the deep interconnections and interdependencies that exist between their subcomponents, as well as between individual systems. The complex and unpredictable behavior of natural and human systems arises from dynamic

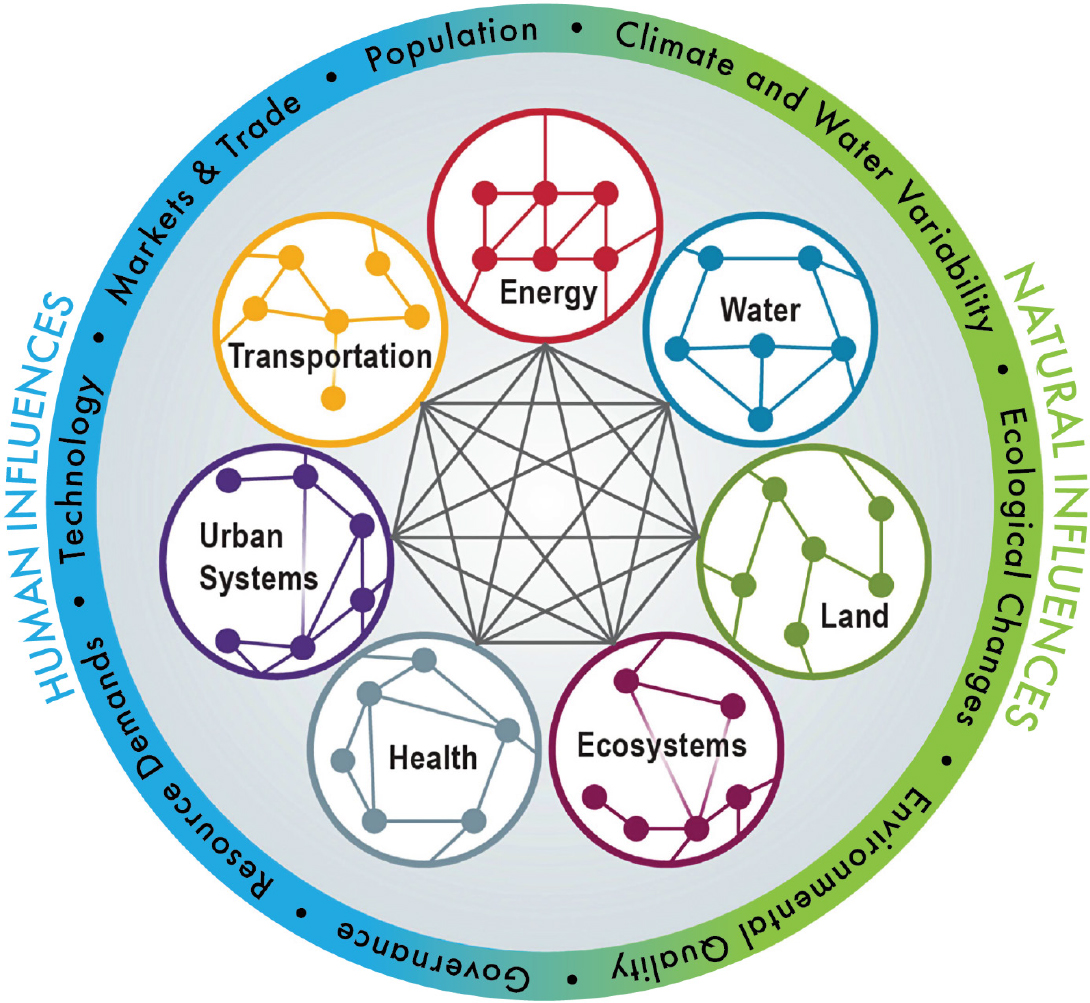

phase, the committee focused its work on evaluating the current scientific research, identifying key uncertainties, and providing recommendations to strengthen future research and analyses. Importantly, the committee did not perform any quantitative modeling itself, nor does their report specifically connect different nuclear employment scenarios to their potential outcomes. The causal pathway described in this report is mapped in Figure S-1. The figure shows key interactions and linkages that would connect, in sequence, the detonation of nuclear weapons, the subsequent firestorms and their attendant emissions of soot and other particles, the physical transport and chemical evolution of this particulate matter in the atmosphere, the resulting impacts on the physical climate system and the environment, and, finally, the effects felt by ecosystems and society.

The figure showcases the highly complex nature of pathways within this interconnected system, where each step from the nuclear weapons exchange to societal and economic impacts introduces its own types of uncertainties. While the level of uncertainty within each step may vary, the overall uncertainty for the outcome increases monotonically and accumulates over the entire assessment pathway. Nuclear employment scenarios and societal and economic impacts are particularly dominated by complex human behavioral responses, for example, decision making during a nuclear war or the reaction of societal systems such as financial markets and trade networks to physical and economic shocks. With these considerations in mind, the following sections summarize key findings, uncertainties, and data needs within the subsystems that would enhance understanding of the potential environmental effects of nuclear war.

EMPLOYMENT SCENARIOS AND WEAPONS EFFECTS: KEY UNCERTAINTIES, FINDINGS, AND RECOMMENDATIONS

Modeling studies of the environmental effects of nuclear war require, as a foundation, a set of realistic weapons employment scenarios that can be used to estimate “source terms’ describing the

___________________

interactions and feedbacks, occurring across scales, that can create cascading effects and unforeseen outcomes in response to an initial shock. A “systems approach” to understanding the environmental and societal and economic effects of nuclear war thus requires us to consider the interconnectedness of the social, economic, political, and environmental factors that create the potential for harm to ecosystems, people, and society.

characteristics of the materials released into the atmosphere by the nuclear blasts and the fires that they create. The committee has provided four scenarios that represent plausible baselines for source terms in future modeling studies, with each scenario representing a qualitatively distinct scale of conflict: a large-scale, strategic exchange between major nuclear powers, involving 2,000 warheads; a moderate-scale strategic exchange of 400 warheads; a small-scale exchange between regional nuclear powers, involving 150 warheads; and a very small-scale scenario with a single detonation. Similar to earlier research approaches, these scenarios are based on currently available estimates of nuclear stockpiles worldwide and apply basic assumptions that reflect current weapons employment doctrines related to targeting patterns, weapons usage factors, and heights of burst. Uncertainties in the employment scenarios that would likely impact the accuracy of modeling of the environmental effects of nuclear war include the following:

- The number of detonations in each plausible baseline weapon employment scenario above could be considerably lower or higher in number depending on each adversary’s choice.

- The spatial and temporal distribution of detonations would be highly dependent on the individual geographic context of a given conflict. Relatedly, weather, time of day, and season could factor into tactical considerations and will likely affect the predicted climate impact.

For any employment scenario, nuclear detonations would release their energy in three main forms: thermal energy, kinetic energy creating an air shock wave, and initial and residual radiation (which is not considered in this study). The thermal energy travels through the atmosphere and can cause burns and ignite materials kilometers away, though it can be blocked by opaque materials or particles in the air. The shock wave creates overpressure that causes structural damage and creates secondary fire ignitions. For surface bursts or low-altitude airbursts, the combination of shock and thermal effects can pulverize buildings and loft debris into the characteristic mushroom cloud, resulting in highly radioactive local fallout within 24 hours and longer-lasting global fallout from smaller particles. The combined thermal and blast effects can generate large fires that produce emissions many times greater than the material in the nuclear cloud itself. Uncertainties in weapons effects that would likely impact the accuracy of modeling of the environmental effects of nuclear war include the following:

- The thermal energy of the detonation would be attenuated by the atmosphere and subject to shielding by terrain and other objects as it travels from the point of detonation to potential fuel sources. Blast waves would also be affected by terrain and materials, as well as atmospheric and meteorological factors.

- The combustibility of materials in areas at risk of fire will be highly variable.

- The role of blast waves in the development of a fire, or interactions with fires that were started by the earlier arrival of thermal energy, is not well understood. The blast can extinguish flames but can also leave smoldering material and rubble, which can grow into larger fires. Blast waves can cause damage that results in secondary ignitions, thus being an additional source of fire starts.

An evaluation of the construction of plausible nuclear weapons exchange scenarios indicates that many previous studies examined extremely large exchanges involving tens of thousands of high-yield warheads, which is no longer reflective of current worldwide stockpiles. To address this problem, the National Nuclear Security Administration (NNSA) should convene experts to produce a more comprehensive set of employment scenarios involving a realistic mix of urban and non-urban targets aligned with modern military use strategies.

An evaluation of weapon employment scenarios further reveals that, while some prior analyses assumed 100% of an adversary’s nuclear arsenal would be employed, previous National Academies studies and military use strategies suggest that around 50% usage is more likely. EENW researchers

should incorporate credible estimates from military experts on the fractions of stockpiles that could realistically be used in different scenarios. Another finding highlights limitations in available weapon effects models based on existing empirical data and oversimplified physics. To overcome this problem, weapon effects modelers should develop higher-fidelity three-dimensional models capable of more accurately simulating real-world weapon detonation impacts in complex environments such as urban areas and terrain.

FIRE DYNAMICS AND EMISSIONS: KEY UNCERTAINTIES, FINDINGS, AND RECOMMENDATIONS

Nuclear detonations generate significant fires through both thermal pulses, which vaporize nearby materials and ignite combustible materials at greater distances, and blast waves, which create rubble and secondary ignition sources. The resulting emissions can be understood through three key factors. First, characteristic fuel loadings and consumption involve the density and composition of available fuels including buildings, vehicles, structures, roads, and vegetation, with different parameters determining what percentage of these fuels burn. Second, ignition and fire spread define the burned area, with sufficient fuel loading and favorable atmospheric conditions potentially allowing individual fires to merge into firestorms with strong convective columns, while areas with lower fuel loading may experience line-like fire fronts driven by ambient winds and topography. Third, emission factors determine the specific pollutants released, including particulate black carbon, organic carbon, particulate matter (PM), and reactive gases such as carbon monoxide and nitrogen oxides, with these emissions potentially reaching the stratosphere where they can have long lifetimes and significant environmental impacts on regional and global scales.

Uncertainties that would likely affect the accuracy of estimates of characteristic local fuel loadings and fuel consumption, ignition and fire spread, and emission factors include the following:

- Historical urban fires may be poor analogs for modern scenarios because of changes in building materials, urbanization patterns, and fire safety standards, while uncertainties remain about fuel characteristics across different land uses and regions worldwide.

- Uncertainties exist regarding fuel characteristics needed for ignition, the relative importance of thermal versus blast-related ignition sources, and limitations in fire spread models, particularly for urban areas.

- Fire spread models often fail to accurately predict behavior because of limited fuel data, inadequate parameterization of physical processes, and questions about oxygen-limited combustion zones.

- The burning behavior of rubblized versus standing fuels is poorly understood, as are the potential interactions between multiple detonations and environmental conditions.

- The effectiveness of modern firefighting capabilities in limiting fire spread after nuclear detonations remains unknown, particularly given possible infrastructure damage.

- The combination of urban and vegetative fuels creates significant uncertainty in determining what actually burns and the resulting emissions.

An evaluation of the current state of knowledge of fire dynamics and emissions reveals that fuel composition and loading in urban, suburban, and industrial zones are poorly characterized compared to rural or wildland areas, yet this information is vital for estimating fire spread, fuel consumption, emissions, and plume heights. To resolve these uncertainties, NNSA should coordinate efforts across agencies to improve urban fuel mapping and modeling approaches. Circumstances such as rubblization, humidity, and topography will significantly affect fire ignition and spread, but existing fire models lack the fidelity needed to capture these effects, especially in complex urban environments. Further model development and experimental studies would strengthen understanding of urban and WUI fire behavior.

Emission factors for important species such as particulate black carbon (BC) and organic carbon (OC) from fires are highly uncertain, and other potential trace gas and toxic emissions have not been studied. EENW researchers should include realistic emissions data in models and support new field measurement campaigns to determine fire emissions in urban, suburban, and wildland–urban interface (WUI) areas.

PLUME RISE, FATE AND TRANSPORT OF AEROSOLS, AND GAS-PHASE CHEMISTRY: KEY UNCERTAINTIES, FINDINGS, AND RECOMMENDATIONS

The emissions from nuclear detonation fires depend critically on plume dynamics, where injection height—determined by factors such as fuel loading, fire area, and conditions—dictates the severity of any environmental impacts, though challenges remain in predicting whether fires will inject soot into the upper troposphere or the stratosphere. In the troposphere, aerosols rise rapidly via heat-induced buoyancy, undergo efficient lateral mixing through weather systems and circulation cells within a month, and face relatively quick removal through dry deposition (settling onto surfaces) or wet deposition (precipitation-related processes). Conversely, in the stratosphere, the inverted temperature profile inhibits vertical mixing, allowing aerosols to persist for years rather than days or weeks, while lateral transport occurs more slowly through the Brewer-Dobson circulation with 3-year overturning times, leading to prolonged environmental impacts through altered Earth radiation balance, especially from scenarios involving numerous large fires producing substantial stratospheric particulates.

Uncertainties that would likely affect the accuracy of estimates of the fate and transport of fire emissions and their gas-phase chemistry include the following:

- Despite atmospheric models being capable of simulating fire plume-rise, major uncertainties persist in time-varying fire parameters (size, geometry, heat fluxes) especially in built environments, making plume height prediction difficult despite evidence that intense fires can inject material into the upper troposphere/lower stratosphere.

- Significant uncertainties exist regarding aerosol properties from fire emissions (effective density, morphology, BC/OC ratios, organic compound composition, particle size distribution), affecting accurate determination of atmospheric fate, transport, and environmental consequences.

- Wet removal processes of particles produced by nuclear detonation or triggered fires remain a major unknown.

- Major wet removal uncertainties include soot morphology, the BC/OC ratios, organic coating compounds affecting hygroscopicity, particle size distribution, and vertical distribution of soot aerosols.

- The quantity and speciation of aerosol and gas emissions from nuclear blasts and subsequent fires are highly uncertain, impacting potential air quality degradation through increased tropospheric ozone, PM concentrations, and toxic emissions.

- Changes in radiation due to aerosol loadings may affect tropospheric chemistry through altered photolysis rates and OH radical concentrations, potentially increasing lifetimes of organic compounds and changing secondary aerosol formation.

- While smoke and NOx injection depends on weapon yield and burst height, subsequent stratospheric transport is sensitive to uncertainties in particle scavenging, self-lofting, convective processes, and large-scale circulation.

- The amount of smoke produced from urban fires varies between studies based on assumptions about burnable material and fire characteristics, with BC/OC ratio being highly uncertain yet crucial for determining radiative properties, lofting potential, stratospheric residence time, and climate impacts.

SOURCE: Kremser et al., 2016. Stratospheric aerosol—Observations, processes, and impact on climate. Reviews of Geophysics 54(2):278-335. 10.1002/2015RG000511.

An evaluation of the current state of knowledge of the fate and transport of fire emissions and their gas-phase chemistry reveals that plume height predictions are important for quantifying impacts, but existing fire models are often inadequate, especially for intense urban fires from nuclear detonations. Further fire model development coupled to atmospheric plume-rise models would ameliorate this. Including atmospheric moisture, cloud microphysics, aerosol–cloud interactions, and removal processes is likewise important for accurate projections which most current plume-rise models lack the capability to represent. The use of high-resolution models with full atmospheric physics and chemistry and collection of observational data for model development and validation would address these needs. On tropospheric impacts, there is a lack of research into the potential air quality, health, and environmental effects from nuclear explosion emissions besides radioactive fallout. Full tropospheric chemistry, deposition impacts, and chemistry coupling between the stratosphere and troposphere should be incorporated in future EENW modeling efforts. Finally, the EENW research community should move beyond simplistic assumptions of initial smoke injection heights used in many previous studies and perform model sensitivity studies across a range of plausible injection parameters such as height, quantity, and compositional variations.

PHYSICAL EARTH SYSTEM IMPACTS: KEY UNCERTAINTIES, FINDINGS, AND RECOMMENDATIONS

The emissions from fires caused by nuclear detonations could create significant disruptions across the physical Earth system. The response of global climate to a nuclear exchange would occur on a range of timescales, involving processes ranging from weeks to over a decade. Beginning with the most rapid effects, particulate loading in the upper atmosphere would immediately decrease solar radiation reaching Earth’s surface, with effects potentially saturating (not scaling linearly) once smoke optical depth exceeds certain thresholds. Stratospheric ozone would be depleted by injected nitrogen oxides and smoke, leading to increased ultraviolet radiation reaching Earth’s surface with subsequent ecosystem damage. Temperature changes would follow radiative alterations, with land surfaces cooling rapidly while oceans respond more slowly, potentially persisting for decades after smoke particles have cleared. Hydrologic cycle disruptions would occur within 10–14 days as altered radiation and surface cooling change radiative-convective equilibrium, affecting rainfall patterns and freshwater availability. Ocean circulation would be disrupted through changes in wind stress, thermohaline convection, and surface salinity from altered freshwater inputs. Cryosphere impacts would result from changes in heat transport from equatorial to polar regions and from carbonaceous aerosol deposition on snow and ice surfaces, potentially triggering long-lasting ice age conditions through albedo feedback mechanisms.

Uncertainties that would likely affect the accuracy of estimates of the impacts on the physical Earth system include the following:

- Uncertainties in aerosol distribution, extinction properties (size, composition, mixing state), and single-scattering albedo make it difficult to accurately predict changes in solar radiation reaching Earth’s surface.

- Temperature predictions are complicated by propagated solar radiation uncertainties, potential alterations to cloud radiative effects, and different feedback mechanisms depending on where smoke resides in the atmosphere.

- Complex relationships between exchange intensity and temperature reductions, coupled with challenges in modeling watershed-level responses, create significant uncertainty in predicting both global and local hydrological changes.

- Ocean response predictions are limited by reliance on a single Earth system model, inadequate representation of mesoscale circulation features, and poor understanding of how slower-evolving ocean dynamics would respond to nuclear exchange conditions.

- Uncertainties exist in how competing processes (short-term warming from BC deposition versus longer-term cooling from stratospheric aerosols) would affect cryosphere dynamics and their teleconnections to broader Earth systems.

- Knowledge gaps regarding stratospheric material transport, composition, chemical reactions involving OC, and effects on stratospheric water vapor limit accurate prediction of ozone depletion following nuclear exchanges.

The committee highlights several key sources of uncertainty that need to be addressed through further research and model development efforts. The committee notes the simplified aerosol microphysics and optical properties in many Earth system models (ESMs), recommending ensemble modeling across plausible parameter ranges. There are uncertainties in modeling cloud–aerosol interactions at extreme aerosol loadings and the subsequent hydrological cycle impacts, which improved targeted cloud-resolving modeling and hydrological process studies could resolve. On the ocean response, most studies have focused only on certain soot injection cases resulting from significant escalation of nuclear weapons exchange and targeting fuel-dense population centers rather than exploring sensitivity across a broader range of plausible nuclear employment scenarios. Systematic multimodel assessments of the ocean sensitivity would improve understanding of the range of impacts. Finally, previous ozone depletion

studies lack appropriate treatment of organic aerosols and varying BC/OC ratios. The committee advocates modeling the influence of the full range of injected stratospheric and tropospheric gas and particles on chemistry, circulation, and ozone loss.

ECOSYSTEM IMPACTS: KEY UNCERTAINTIES, FINDINGS, AND RECOMMENDATIONS

Nuclear war would disrupt ecosystems through changes in solar radiation, temperature, and the hydrologic cycle. Ecosystem functioning would be significantly altered as decreased solar radiation reduces temperatures and slows the water cycle. Net primary production (NPP) would likely decrease in temperature-limited higher-latitude forests while effects on water-limited drylands remain uncertain due to competing factors of reduced precipitation and evaporative demand. Marine ecosystems would experience severe reductions in photosynthetically available radiation (up to 50% in worst-case scenarios) along with complex changes in ocean chemistry: initial increases in pH followed by prolonged decreases in calcium carbonate saturation states threatening coral reefs. Ocean cooling would enhance vertical mixing, temporarily increasing surface nutrient concentrations by approximately 30% and altering phytoplankton community structure, potentially favoring larger diatom species. Biodiversity impacts, though highly uncertain, could include local extinctions, habitat shifts, and colonization of abandoned croplands. Humans might respond by increasing deforestation in lower latitudes to compensate for agricultural losses, further threatening biodiversity. Freshwater ecosystems could face multiple stressors including direct blast effects, fires, altered hydrology, and contamination. Our understanding remains limited by models that may inadequately represent biological responses to the abrupt, severe environmental perturbations characteristic of post-nuclear war conditions, including potential increases in harmful UV radiation from stratospheric ozone depletion.

Uncertainties that would likely affect the accuracy of estimates of the impacts on the physical Earth system include the following:

- Unlike gradual global warming which allows time for adaptation, nuclear war would cause sudden cooling with little opportunity for organisms and society to adapt, making it difficult to accurately predict ecological responses by simply inverting warming studies.

- Models simulating rapid planetary cooling are limited, and while radiation-climate physics are relatively well understood, ecosystem impacts remain unclear due to varying responses across different geographical regions and complex human land-use changes that would follow.

- Knowledge about freshwater ecosystem responses to nuclear detonation is severely limited, with assessments relying primarily on volcanic eruption analogs, despite crucial gaps in understanding how nuclear war would alter the hydrologic cycle and contaminate water systems.

- Marine ecosystem impact studies rely on ESMs calibrated for present-day conditions that may inadequately represent responses to sudden environmental changes, fail to capture simultaneous stressors (such as photosynthetically active radiation (PAR) limitation and UV inhibition), contain uncertainties in physical ocean circulation modeling, and rarely include adaptation or evolutionary mechanisms needed to predict biodiversity changes.

The committee highlights several key uncertainties and areas requiring further research. There is a need for better characterization of the post-detonation UV, PAR, and radiation profiles to inform ecosystem modeling. There is a lack of models capturing abrupt cooling impacts compared to the wealth of warming scenarios studied, and development of this new model capability and an intercomparison effort is recommended. Additionally, there is a need to examine relative sensitivities and responses across different regions and ecosystem types, accounting for factors such as water availability, and to explore terrestrial ecosystem interactions with climate changes as well as potential human-driven land-use changes such as deforestation. Overall, improved process understanding, experimentation, and observations are needed to reduce uncertainties in modeling these severe ecosystem disruptions.

SOCIETAL AND ECONOMIC IMPACTS: KEY UNCERTAINTIES, FINDINGS, AND RECOMMENDATIONS

A nuclear conflict would have significant societal and human impacts that extend far beyond the immediate blast zone. Ecosystem services such as agriculture and food production would be disrupted by cooling and changes in precipitation, which would reduce crop yields and livestock productivity. Environmental quality, in general, would be expected to decrease due to widespread air, water, and soil pollution from infrastructure damage and fires. Human health would suffer both from direct effects, such as from blast injuries or lack of emergency medical care, and indirect effects involving disease transmission, malnutrition, and mental illness. Persistent environmental contamination and psychosocial stressors could potentially create intergenerational health consequences. The broader societal impacts would include mass displacement straining shelter and resource systems, profound psychological trauma, behavioral disruptions such as panic and hoarding, potential curtailment of civil liberties, and cascading failures across interconnected critical systems—all of which would be modulated by community resilience factors, with global interconnectedness potentially both amplifying harm through teleconnections and providing opportunities for intervention and recovery.

Uncertainties that would likely affect the accuracy of estimates of the impacts on the physical Earth system include the following:

- Uncertainties in data, modeling, and complex feedbacks limit our ability to assess how nuclear war would affect ecosystems, agriculture, and food systems on a global scale.

- Gaps in up-to-date research and limited understanding of both direct and indirect health impacts make it difficult to predict how nuclear war would affect physical and mental health over time.

- Predicting societal outcomes is challenging due to the unpredictability of human behavior, system interdependencies, and long-term psychological and cultural consequences.

SOURCE: DOE, n.d. DOE Explains…Multi-Sector Dynamics Modeling. https://www.energy.gov/science/doeexplainsmulti-sector-dynamics-modeling.

The committee highlights the interconnected vulnerabilities across global supply chains, financial systems, and communication networks, which could allow localized shocks from a nuclear event to catalyze cascading broader risks. The committee calls for a collaborative multiagency effort to assess these interconnected societal and economic impacts. Noting that comprehensive impact assessments are hampered by limited data, process understanding, and modeling capabilities, especially around critical areas such as agriculture and food security, the committee advocates investing in improvement of modeling that integrates climate, crop, livestock, and economic factors to bolster preparedness strategies.

There are major research gaps around quantifying the impacts of abrupt cooling and environmental shocks on crop yields, livestock, fisheries, pollution exposure pathways, and ecosystem recovery timelines. A broad, multimodal approach would help address these gaps, including model intercomparisons, observational constraints, scenario analyses, and evaluations of adaptation capacities across food, water, trade, and ecological systems. On public health, there is significant potential for mortality, morbidity, and health system disruptions from environmental degradation, food and water insecurity, and loss of societal and economic resilience after nuclear weapon exchanges. The extent to which this occurs is highly variable, and the committee calls for research quantifying the differential health burdens and strengthening health system preparedness. Nuclear weapon detonations and the resulting impacts will propagate through the multiple domains of social capital and community resilience. The committee advocates implementation research examining how social and health disparities and vulnerabilities influence societal-level impacts and recovery trajectories.

CONCLUSION

Many uncertainties remain and could be reduced with a more coherent and comprehensive approach to modeling. The study committee has developed the following overarching Finding S-1 and Recommendation S-1 which, along with a proposed Environmental Effects of Nuclear War Model Intercomparison Project, identifies needs for addressing uncertainties and data gaps across the entirety of the causal pathway.

FINDING S-1: There is insufficient modeling effort, organization of modeling (based on choice of employment scenario; wargaming), and comprehensive testing of models, and a need to acknowledge:

- the importance of integrating teleconnected impacts and risks;

- the importance of integrating geographic context, the key underlying conditions, and structural vulnerabilities that interact with the environmental effects;

- the importance of a multisectoral dynamics approach, and our ability to model amplification or amelioration across systems and sectors, ability to model shocks, and nonlinearities; and

- the importance of understanding human behavior and decision making and human response as a determinant of risk.

Early global climate modeling documented substantial differences among different climate models, motivating in-depth model intercomparison projects (MIPs)2 to accurately characterize uncertainties, both structural (model design and components) and statistical. MIPs are motivated by the critical role that robust and well-quantified information plays for decision making by the public and private sectors as they confront climate change. Given the importance of nuclear war

___________________

2 CMIPs have been repeatedly carried out as models have become more complete (e.g., including coupled water cycle and ecosystems) and as scenarios for future greenhouse gas emissions have evolved. While generally applied to models, MIPs also have been applied to observational datasets. A catalog of MIPs carried out or underway (available at https://www.clivar.org/clivar-panels/former-panels/aamp/resources/mips) describes over 30 different activities, including for example, an El Niño–Southern Oscillation (ENSO) intercomparison project, an ocean-carbon cycle model intercomparison project, a sea-ice model intercomparison project. MIPs ensure open scrutiny of how different models perform and differences in observations, building trust and credibility for climate science.

to security policy, it is important that a series of MIPs be similarly applied, to ensure an appropriate level of confidence and robustness in the underlying science.

RECOMMENDATION S-1: Relevant U.S. agencies should coordinate the development of and support for a suite of model intercomparison projects (MIPs) to organize and assess models to reduce uncertainties in projections of the climatic and environment effects of nuclear war. This effort should employ stress testing where appropriate (human factors) and parametric variations, support data availability and integration, and use an enterprise approach with a system of systems.

The current framing of MIPs is summarized in Table S-1, which is categorized by the process/component, input, modeling needs, modeling community, and outcome, mapping back to specific recommendations from the report. The table is framed around a Coupled Model Intercomparison Project (CMIP)-type MIP, starting (from top to bottom) with rows describing work (or MIPs) that may inform the CMIP, then what the CMIP would investigate, and then what other work (or MIPs) that would be informed by the CMIP.

Because of the vast array of systems interactions involved and the complexity and uncertainty of each system and their interactions and responses to others, the suggested map of MIPs will be most effective if each suggested MIP is able to identify crucial characteristics of its components and the lower and upper bounds of their outputs, to inform a suite of prescribed forcings for the next MIP that is representative of the parameter space needed to be explored. By determining a suite of prescribed inputs for the next MIP to constrain the forcings for different component models, the suggested work can prevent propagation of uncertainties across systems to isolate the sources of uncertainty within the next system and focus on exploring its response to the previous system in a robust way.

Key to evaluating the potential environmental effects of nuclear war is understanding the uncertainties of various processes and how the uncertainties propagate across the causal pathway beginning with the choice of the nuclear weapon employment scenario evaluated. To then accurately determine downstream environmental impacts of a given employment scenario, one would need to know the fuel in the region of the blast, characterize the emissions from resulting fires, project the transport and fate of these emissions, and how these would impact the global climate systems as well as regional environmental processes, and through these, various ecosystems. The societal and economic consequences will be strongly determined by the resilience of the impacted communities. The resilience with which communities across the world respond to the stressors from such nuclear detonation scenarios will depend on the scale of the impacts and on underlying vulnerabilities in health, societal systems, and global teleconnections and the actions taken by researchers and society at large to reduce them.

The size and extent of the set of recommendations presented in this report is daunting, as are the uncertainties involved in determining which of these recommendations are most pressing or consequential to improving the modeling and prediction of the effects of a nuclear conflict. As is described in earlier sections, however, there are clear segments along the causal pathway in which uncertainties are relatively greater - namely in sections related to fire and emissions, where there are many specific questions related to the physical processes of fire and emissions, and in sections related to ecosystems services and socioeconomic effects, where human behavior and decision-making come into play. Moreover, overall uncertainty accumulates and propagates over the entire causal pathway. These observations may collectively offer insight into where research priorities may lie -- however, given the breadth of the disciplines and federal agencies involved in this topic, this report does not offer an explicit scheme for prioritizing or sequencing its recommended actions.

TABLE S-1 Environmental Effects of Nuclear War Model Intercomparison Project

| Recommendation | Process | Input | Research Needs | Research community | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2-1, 2-2* | Employment scenarios |

|

Wargaming and tabletop exercises, perspectives from military experts and policymakers | Military/intelligence | Usable set of plausible scenarios for modeling inputs (Inform CMIP) |

| 2-3 | Weapon effects | Weapon employment as specified in scenarios | Development and validation of 3-D models of nuclear weapon effects | Weapon effects modelers, emergency response planning | Understand interaction of weapon effects (thermal and blast) with emplacement and environmental conditions for improved fire ignition modeling (Inform CMIP) |

| 3-1* | Fuel loading | Mix and range of target area type | Data and focused modeling studies | Fire science and engineering and wildland fire communities | Increased accuracy in predictions of fire ignition, spread, and emissions (Inform CMIP) |

| 3-2, 4-1 | Ignition, spread | Consider potential environmental and physical factors that amplify or dampen | Improved understanding of physics and chemistry of fire ignition and spread; development of fire models for urban environments | Fire science and engineering and coupled atmosphere–fire modeling communities | Increased understanding of fire fluxes, spread, and chemistry (Inform CMIP) |

| 3-3*, 3-4*, 3-5 | Emissions |

|

Better understanding and quantification of composition of emissions from urban and suburban fires | Fire inventory and fire modeling communities | More accurate emissions (e.g., BC/OC ratio), including gaseous chemistry (Inform CMIP) |

| 4-1*, 4-2, 4-3 | Plume rise | Fuel loading, emissions factors; realistic atmospheric conditions, atmospheric physics and chemistry | Coupled atmosphere–fire ignition and spread models, including both fire and atmospheric chemistry and cloud–aerosol interactions; validation with observational data | Coupled atmosphere–fire modeling community | Improved quantification of heterogeneous fire fluxes and understanding of resulting plume height, interactions with the ambient atmosphere, aerosol properties within the plume, and in-plume removal mechanisms (such as wet scavenging) (Inform CMIP) |

| 4-4, 4-5 | Atmospheric chemistry | Emissions, physicochemical characteristics of plumes | Fully coupled models of the troposphere and stratosphere with full chemistry and radiative transfer | Atmospheric chemistry community | Impacts on tropospheric chemistry due to tropospheric emissions and stratospheric changes |

| 4-6 | Climate model sensitivity to plume height | Injection height, smoke quantity and composition | Sensitivity studies of climate models to injection height, smoke quantity and composition | Earth system modelers | Improved understanding of climate sensitivity to plume height, smoke quantity and composition (Inform CMIP) |

| 5-1* | Aerosol properties | Estimates and range from upstream models leading to aerosol forcing | Prescribe aerosol properties using new observations, and sensitivity studies of the Earth system to these properties | Plausible range of aerosol optical, physical, and microphysical properties for a given scenario (Inform CMIP) | |

| 5-2 | Cloud–aerosol interactions | Realistic aerosol quantities and properties | More simulations with cloud-resolving models with large aerosol loadings | ESM development | Better understanding of cloud–aerosol microphysical interactions following large aerosol loadings (Inform CMIP) |

| 5-2 B | Global cooling | Input from upstream models | Global climate models that can handle abrupt change | ESM development | Improve understanding of cooling intensity and duration across regions and seasons |

| 5-3 | Hydrologic cycle | Suite of scenarios to explore Earth system response to prescribed aerosol forcing varying in amount, injection height, composition, and seasonal timing and latitude of injection | Sensitivity studies; scenarios of water management in controlled waterways | A new ESM intercomparison for nuclear war scenarios similar to CMIP | Better understanding of possible changes in precipitation (location, timing, intensity, duration) |

| 5-4 | Ocean response | Sensitivity studies; range of representation of the ocean-impact drivers (acidity, thermal structure, currents, oxygen) | A new ESM intercomparison for nuclear war scenarios similar to CMIP | Better understanding of ocean state changes | |

| 5-5* | Stratospheric ozone | Systematic modeling as a function of model structure, resolution, treatment of aerosols, and forcing scenario | A new ESM intercomparison for nuclear war scenarios similar to CMIP | How compounds influence atmospheric circulation, chemistry, and ozone depletion rate | |

| 6-1 | Radiation effects on climate | Direct radiation effects and recovery (CMIP informed) | Interactive effects of aerosol on UV, PAR, and diffuse vs. direct radiation | AgMIP, ISIMIP | Better understanding of ecosystem impacts as a result of radiation response to realistic scenarios |

| 6-2*, 6-5, 7-3 | Environmental conditions from sudden cooling (CMIP informed) | Sensitivity studies of organisms to the resulting environmental shocks, coupled to models with key natural resource systems that provide food, materials, medicines, and energy | AgMIP, ISIMIP | Sensitivity of organisms, ecosystems, and ecosystem services to potential sudden environmental shocks | |

| 6-3* | Differential response | Suite of realistic scenarios (radiation and temperature changes and duration) (CMIP informed) | Sensitivity studies of different regions with respect to scale of scenario | Regional sensitivity and differential response to induced variation in environmental factors |

| Recommendation | Process | Input | Research Needs | Research community | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 6-4* | Differential limitation of precipitation and temperature | Regional sensitivity and differential response to induced variation in environmental factors | Sensitivity studies of different ecosystems to simultaneous change in precipitation and evapotranspiration | CMIP, AgMIP, ISIMIP | Sensitivity of different terrestrial ecosystems to simultaneous changes in precipitation and evapotranspiration |

| 7-3* | Ecosystem response | New experiments and models that unravel the effects of sudden environmental change | Use of climate models that can handle rapid radiation changes | ISIMIP | Impacts of sudden and lasting cooling on drylands and forests of the world |

| 7-3* | Crop response | Suite of climate, environmental, societal, and economic scenarios (CMIP, AgMIP Informed) | Understanding of impacts on crops from surface ozone, ultraviolet radiation, and freshwater availability and improved projections of agricultural productivity changes for major staple crops in key producing regions due to changing climatic conditions and trade implications in the short and long terms. | AgMIP | Identification of regions and agricultural systems that are most vulnerable or resilient to nuclear war-induced climate effects, as well as opportunities to enhance resilience |

| 7-1*, 7-2*, 7-3* | Food system resilience | Suite of climate, environmental, societal, and economic scenarios (CMIP, AgMIP Informed) | Evaluation of adaptive capacities, technological limits, and vulnerabilities of regional agricultural systems (crops and livestock); analysis of changing requirements for land, water, energy, and financial resources; capture of complex connections and feedbacks between climate changes, pollution, and human systems and improvement in geographic data on global food stocks, agricultural inputs, production capacities, and supply chain infrastructures; identification of exacerbations of inequality and differential vulnerabilities | IAMC, AgMIP, ISIMIP | Understanding how the system effects of food impacts can cascade through value chains and trade, impacting producers and consumers, and influencing competitive balances |

| 7-1*, 7-2*, 7-3*, 7-4, 7-5 | Community resilience | Suite of climate, environmental, societal, and economic scenarios (CMIP, AgMIP Informed) | Scenario modeling and economic analysis to guide policies that could mitigate food insecurity and ecological degradation if nuclear war occurs; advancing the assessment and periodic monitoring of social capital domains in at-risk communities; research on predictive modeling of the integration of data characterizing the social capital domains and the pillars of community resilience in selected vulnerable communities; exploring dietary/nutritional effects of differential impacts on proteins, cereal crops, and nutrient-rich fruits and vegetables. | IAMC, AgMIP, ISIMIP | Solutions and opportunities to build and enhance resilience and reduce inequalities in vulnerability and health exposures and outcomes from nuclear war-induced climate responses, scaled to decisions and system exposure |

NOTES: AgMIP (Agricultural Model Intercomparison and Improvement Project), BC (black carbon) CMIP (Coupled Model Intercomparison Project), ESM (Earth system model), IAMC (Integrated Assessment Modeling Community), ISIMIP (Inter-Sectoral Impact Model Intercomparison Project), OC (organic carbon), PAR (photosynthetically active radiation).

* Key Recommendations