Potential Environmental Effects of Nuclear War (2025)

Chapter: 6 Ecosystem Impacts

6

Ecosystem Impacts

6.1 INTRODUCTION

This report explores the environmental and societal and economic effects that would occur in the weeks-to-decades following a nuclear war. The report begins by considering a plausible set of weapons employment scenarios (Chapter 2) and then traces mechanistic pathways that connect initial weapons exchanges to the fire dynamics and emissions resulting from nuclear detonations (Chapter 3); the fate and transport of these emissions once aerosolized (Chapter 4); and the subsequent changes in the climate and physical Earth system (Chapter 5). The current chapter considers the potential impacts of these changes on ecological systems and sets up a discussion, in Chapter 7, of societal and economic consequences. This report does not quantitatively link the weapons employment scenarios to specific environmental and societal and economic consequences. Instead, general scientific principles were applied, existing studies were synthesized, and appropriate historical analogs were examined to reach its conclusions.

BOX 6-1

Key Terms

Biodiversity: Variety of life forms, including plants, animals, and microorganisms, that exist in a particular ecosystem, biome, or on the entire planet. It encompasses diversity at the genetic, species, and community levels.

Biomass: Total mass of living organisms within a given area of an ecosystem. It can be measured for different trophic levels (e.g., producer biomass, consumer biomass) or for the entire ecosystem.

Biome: Major regional group of distinctive plant and animal communities adapted to the prevailing climate and other environmental conditions.

Consumers: Organisms that obtain energy and nutrients by feeding on other living organisms or their remains. Consumers can be herbivores (feeding on plants), carnivores (feeding on animals), omnivores (feeding on both plants and animals), or detritivores (feeding on dead organic matter).

Ecosystem: Community of living organisms (plants, animals, and microbes) interacting with each other and with the nonliving components of their environment (solar radiation, air, water, and mineral soil) considered as a unit.

Evapotranspiration: Combined process of water evaporation from land and water surfaces, and transpiration from plants.

Freshwater Ecosystems: Aquatic environments with low salt concentrations, such as lakes, rivers, and wetlands.

Marine ecosystems: Aquatic environments with high salt concentrations, such as oceans, seas, and estuaries.

Net Primary Production (NPP): Rate at which ecosystems convert carbon dioxide and radiant energy into organic compounds through photosynthesis, minus the amount lost through heterotrophic and autotrophic respiration. It provides energy to support consumer organisms in the ecosystem.

Nutricline: Vertical zone in a body of water where the concentration of dissolved nutrients increases rapidly with depth.

Nutrients: Chemical elements and compounds essential for the growth, metabolism, and overall functioning of living organisms. Major nutrients include carbon, nitrogen, phosphorus, potassium, and various micronutrients.

Photosynthesis: Process by which green plants, algae, and some bacteria use the energy from sunlight, water, and carbon dioxide to produce oxygen and energy-rich organic compounds (such as glucose) that can be used as food.

Photosynthetically Active Radiation (PAR): Total solar radiation at wavelengths between 400 (violet) and 700 nm (red) that is available for photosynthetic activity, also referred to as photosynthetically available radiation.

Phytoplankton: Microscopic aquatic organisms that photosynthesize and form the base of the marine food chain.

Producers: Organisms, such as green plants, algae, and some bacteria, that can produce their own organic compounds from inorganic materials through photosynthesis or chemosynthesis, serving as the primary source of energy and nutrients for other organisms in an ecosystem.

Trophic Structure: Organization of the ecosystem into different trophic levels (producers, herbivores, carnivores, decomposers) and the flow of energy and nutrients between these levels.

Thermocline: Layer in a body of water (e.g., the interior of the ocean) with a high gradient of temperature with depth.

Upwelling/Downwelling: The vertical movement of water in oceans or lakes, with upwelling bringing cold, nutrient-rich waters to the surface, and downwelling pushing surface waters downward.

Ultraviolet Radiation: Portion of the electromagnetic spectrum with wavelengths shorter than visible light but longer than X-rays that can damage DNA and cellular structures.

6.2 DRIVERS OF ECOSYSTEM FUNCTIONING UNDER NUCLEAR WAR INDUCED ENVIRONMENTAL CHANGE

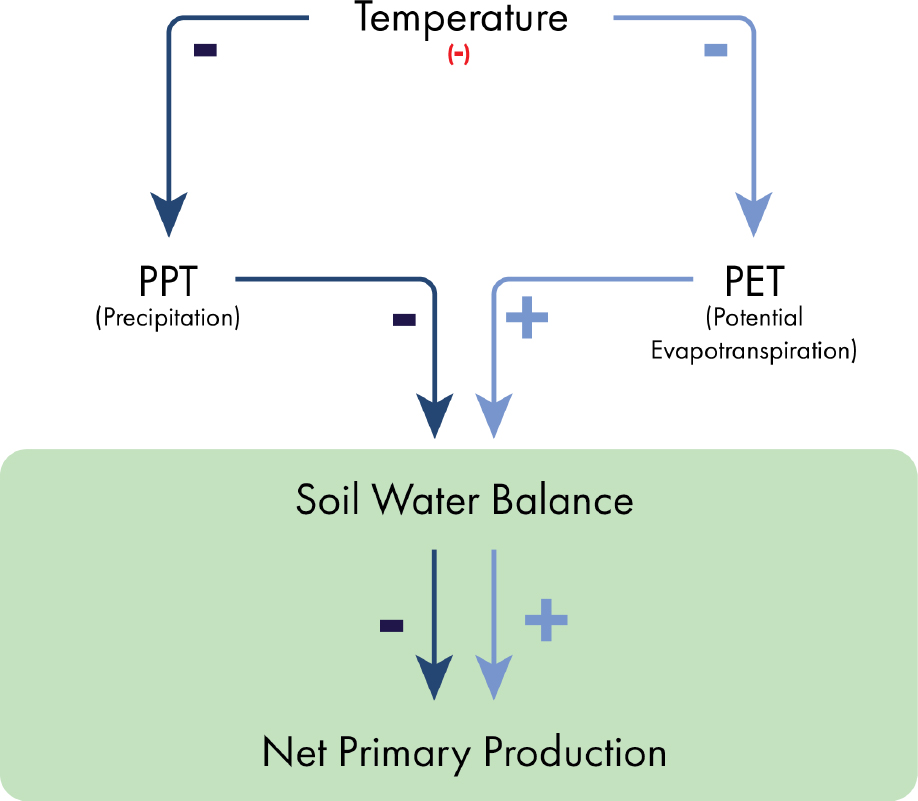

Impacts on ecosystem structure and functioning resulting from nuclear war would be driven largely by the changes in solar radiation, both directly, and indirectly via temperature and precipitation. The extent of these impacts are largely determined by the magnitude of different weapons employment scenarios which would also dictate whether these are local or global effects. Figure 6-1 illustrates some of the major pathways connecting the nuclear war–induced changes in the physical environment to ecological consequences in terrestrial (left) and oceanic (right) settings, focusing on net primary production (NPP) as a key indicator of ecosystem functioning. In terrestrial ecosystems, the effects will be dominated by the decrease in temperature that would slow the water cycle. Specifically, it means simultaneous reduction in precipitation and potential evapotranspiration (PET). In terrestrial ecosystems, NPP depends on soil-water availability, which in turn depends on the input, mostly as precipitation, and the output evapotranspiration, which is driven mostly by temperature.

Ultimately, the ecological impacts of nuclear war on terrestrial ecosystems will depend on the relative importance of temperature on decreasing demand and decreasing supply. The relative importance of these two competing forces depends on the location on planet Earth. In general terms, higher-latitude and low-temperature areas, such as temperate and cold forests, will be negatively impacted by decrease in temperature. The impact on drylands and low-latitudes savannas, which are water limited, is uncertain because it will depend on the relative changes in precipitation and temperature.

The impact of nuclear war–induced climate change on ecosystems is related to the decrease in temperature and duration of the change in climate. Further, the effects of changes in temperature and their duration would be modulated by the geographical extent. We expect that the larger the change in climate and its duration the broader will be the impact. As the nuclear exchange scenarios described in Chapter 2 increase from small to very large, the cooling of the atmosphere will increase, the duration will be longer and the spatial impact broader, shifting from regional to global phenomena.

The impacts of stratospheric aerosols on global temperatures can be evaluated using general circulation model studies and by examining appropriate historical analogs. Nuclear war is expected to produce rapid reductions in temperature, as indicated by models and analyses of past volcanic eruptions (Sigl et al., 2015). Past volcanic eruptions can be used as a model of the type of climate effect expected from a nuclear war scenario. It is clear evidence that past volcano eruptions have reduced global temperature between 0.5 and 1°C and up to 2.7°C. These eruptions and the associated changes in climate have apparently caused large impacts on human society (Sigl et al., 2015). The volcano-eruptions effects are relatively small when compared to the hypothetical climatic effects following nuclear war soot injections (5–150 Tg) reported by the National Research Council (NRC, 1985) and by Xia et al (2022) that ranged from –1 to –15°C, reaching a peak temperature decrease approximately 3 years post-soot injection. The 1991 eruption of Mount Pinatubo is one of the largest volcanic eruption events in the last

100 years with a TNT equivalent burst of 70 Mt. The event injected roughly 15 million tons of sulfur dioxide into the stratosphere which subsequently reacted with other atmospheric compounds resulting in significant terrestrial impacts (Tahira et al., 1996; Guo et al., 2004). Diffuse sunlight increased by 20% but direct sunlight decreased by 21% resulting in a net 2.5% reduction in total global sunlight (1991-1993). This equates to over a 6 W/m2 decrease in net solar radiation (Proctor et al., 2018). Global temperatures dropped by 0.5 °C between 1991 and 1993 and precipitation over land decreased resulting in a record decrease in runoff and river discharge into the ocean from 1991 to 1992 (Aquila et al., 2021).

The amount of solar radiation that would reach Earth’s surface following a nuclear exchange is a function of the quantity of sunlight-blocking particles released into the atmosphere and the lifetime of these particles in the stratosphere. Photosynthesizing organisms in terrestrial, aquatic, and marine ecosystems use the visible wavelengths of the electromagnetic spectrum (400–700 nm), so-called photosynthetically available radiation (PAR). Sunlight in the ultraviolet portion, (UV, 200- to 400-nm wavelengths), however, is potentially harmful, with cell damage increasing as wavelength decreases. Ozone in the stratosphere strongly absorbs UV radiation at the shortest wavelengths (UV-C, 200–280 nm) as well as a large fraction of the UV radiation at the mid-UV wavelengths (UV-B, 280–320 nm), preventing a large fraction of this radiation from reaching the surface and harming life.

Recent studies using general circulation modeling approaches have described the potential changes in surface shortwave radiation after atmospheric soot injections (Robock et al., 2007a; Toon et al., 2008), but this research does not explicitly decompose these radiation changes into PAR and UV components. Using a fully coupled Earth system model, a recent study demonstrates that global mean surface PAR decreases from 62 W/m2 to 25 W/m2 in the year following a simulated nuclear war that injects as a worse-case scenario 150 Tg of black carbon into the atmosphere, with a gradual recovery to preconflict PAR values ~10 years following the conflict (Harrison et al., 2022). Coupe et al. (2021) report PAR values for the Eastern Equatorial Pacific (a highly productive ocean biome) from a coupled Earth system model simulating nuclear war. Annual-mean PAR in this biome is ~78 W/m2, decreasing to ~62 W/m2, 52 W/m2, and 35 W/m2 1-2 years after nuclear wars that inject 27.3 Tg of soot, 46.8 Tg of soot, and 150 Tg of soot respectively. The recovery back to annual-mean PAR here takes 6, 8, and 10 years, respectively, in the 27.3-, 46.8-, and 150-Tg soot simulations (Coupe et al., 2021).

The amount of UV radiation that reaches Earth’s surface following nuclear war is determined by the magnitude and duration of stratospheric ozone depletion (see Sections 5.2 and 5.7). Whereas multiple studies have simulated a reduction in solar radiation following nuclear war due to elevated concentrations of soot in the stratosphere (e.g., Robock et al., 2007a,b; Toon et al., 2008), only two studies report on the UV changes that may occur post-conflict. Mills et al. (2014) find summer enhancements of UV indexes of 30–80% over midlatitudes 3 years after a simulated conflict that injects 5 Tg of black carbon into the atmosphere. Using an Earth system model with interactive chemistry and inline photolysis and actinic flux calculations, Bardeen et al. (2021) illustrate that, following a regional nuclear war (5 Tg black carbon), surface UV increased 5–10% that persists for 2–6 years post-conflict. Whereas, following a large-scale nuclear exchange (and the worst-case amount of 150 Tg black carbon from the study), a pulse of surface UV radiation (10–20% increase) begins ~8 years post conflict and persists for ~4 years, during the period when the soot has cleared but stratospheric ozone has not yet recovered (Bardeen et al., 2021).

In addition to PAR and UV, photosynthesizing organisms are sensitive to the availability of nutrients such as nitrate, phosphate, and iron. In marine ecosystems, the supply of these nutrients would be expected to change significantly under climate conditions caused by a large-scale nuclear war. In the ocean, nutrients are generally more abundant in deeper waters, so photosynthesis occurs most readily in locations where light is plentiful (i.e., surface waters) and where vertical mixing and circulation bring up nutrients from depth or winds and currents can transport nutrients horizontally. In a cooler climate following a large-scale nuclear war, waters at the surface of the ocean would become colder and denser, destabilizing the water column and enhancing vertical mixing (see Section 5.5.1), with consequences for nutrient delivery. Harrison et al. (2022) found that global ocean surface nitrate concentrations increase by ~30% 2–3 years following a global nuclear war (150 Tg black carbon), driven by increases in the vertical nutrient flux from the deep to the surface ocean. Enhanced global surface nutrient concentrations persist

well beyond the atmospheric soot perturbation. Approximately 10 years post-conflict, the ocean enters a new state, characterized by elevated nitrate concentrations in the upper 500 m and lower nitrate concentrations below, with the magnitude of the anomaly proportional to the radiative forcing across a range of nuclear war scenarios (5–150 Tg black carbon; Harrison et al., 2022).

The global cooling associated with nuclear war would also drive changes in ocean carbonate chemistry and acidity, as measured by the calcium carbonate saturation state (Ωarag and Ωcalc, for aragonite and calcite, respectively) and pH (a measure of hydrogen ion concentration; pH = –log[H+]). Shifts in ocean acidity would thus have consequences for the many organisms that precipitate shells of calcium carbonate, since shell dissolution is enhanced at lower pH and Ω values. Using a coupled Earth system model with fully resolved ocean carbonate chemistry, Lovenduski et al. (2020) simulated the response of surface ocean acidity to regional and global nuclear wars that inject 5, 27, 47, and 150 Tg of black carbon into the atmosphere. They found increases in globally averaged surface ocean pH of 0.005 Ω 0.05 units that peak 2 Ω 4 years after nuclear war and persist for ~10 years, driven by changes in the temperature-sensitive carbonate chemistry equilibrium constants. In the North Atlantic, North Pacific, and Equatorial Pacific, surface ocean pH increases by 0.6 units in the largest regional conflict (47 Tg black carbon). Such changes in pH would alleviate the low pH values brought on by ocean acidification, providing a temporary reprieve for shell-building organisms. However, Lovenduski et al. (2020) reported that approximately 1–2 years after the pH anomalies, globally averaged surface ocean Ω arag decreases by 0.1, 0.2, and 0.35 units in the 27-, 47-, and 150-Tg nuclear war scenarios, respectively, and does not recover for at least 15 years post-conflict. Changes in Ωarag are an indirect consequence of cooler surface waters, enhanced solubility of carbon dioxide, and thus increased dissolved inorganic carbon concentrations in the surface ocean (Lovenduski et al., 2020). Large regional decreases (on the order of 0.5 unit in the 47-Tg simulation) in surface Ωarag occur in regions that support diverse coral reef ecosystems, such as the western tropical Pacific and Caribbean (Lovenduski et al., 2020), which has the potential to engender coral skeleton dissolution.

6.3 IMPACTS ON ECOSYSTEM STRUCTURE AND FUNCTIONING

6.3.1 Terrestrial Ecosystems

NPP and aboveground net primary production (ANPP) and their controls at multiple scales from the plot to the global scales have been reported several times (Maurer et al., 2020). The major control of terrestrial ANPP and NPP is soil-water availability that is modulated by the precipitation input and the potential evapotranspiration (Figure 6-2).

Under scenarios of a nuclear war, a reduction in temperature is expected with a magnitude associated with the size of the weapon exchange as depicted in Chapter 2 and subsequent chapters. A reduction in temperature will slow the water cycle and reduce global precipitation. Simultaneously, it will decrease the PET, which represents the demand for water that occurs through plant-leaf transpiration and bare-soil evaporation. So, the impacts of nuclear war–induced cooling on soil water will depend on the relative change in precipitation and PET. The relative effect of changes in precipitation and PET would vary regionally. Regions that currently receive abundant precipitation, such as temperate forests, would not exhibit large changes in the soil-water balance. On the contrary, water-limited regions such as grasslands, steppes, and deserts will benefit by reduction in PET. It is likely that these regions would experience an increase in soil-water availability.

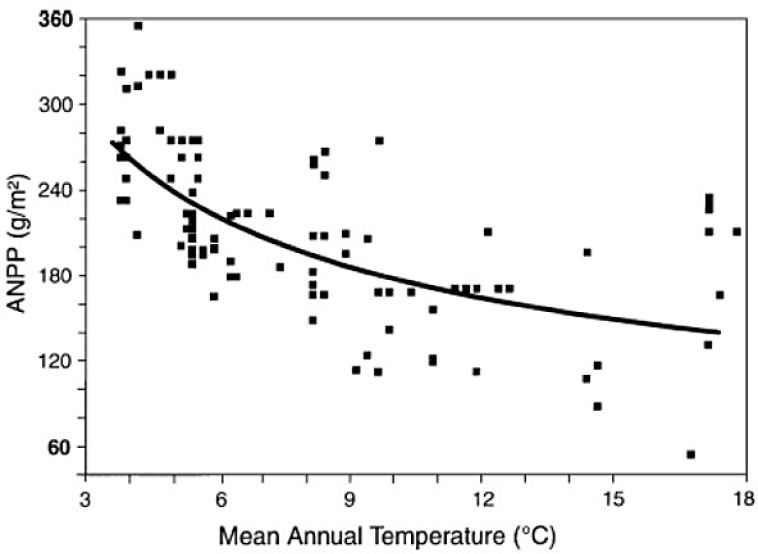

Epstein et al (1996) analyzed results of ANPP, mean annual temperature and mean annual precipitation from 296 locations in the Great Plains of the United States. Statistical models separated the positive effects of mean annual precipitation from the negative effects of increasing mean annual temperature. This analysis suggests that in this region a reduction in temperature resulting from a nuclear war may increase ANPP.

Under nuclear war–driven climate change, other variables may have impacts on NPP. Reductions in direct radiation and temperature may decrease the length of the growing season in higher-latitude regions that are not limited by water availability. Shortening of the growing season will have negative effects on NPP. Most of our current understanding is based on studies of the opposite phenomenon, climate warming. Simulation of climate warming between 2000 and 2099 using five models for 14 basins in the United States found an increase in growing season length between 27 and 47 days (Christiansen et al., 2011).

6.3.2 Aquatic Ecosystems

Like terrestrial ecosystems, climate and solar radiation are important regulators of freshwater ecosystem structure, and functioning. However, unlike terrestrial systems, the influence of climate on freshwater systems is realized through processes associated with the local physical environment and the

impacts of air temperature and precipitation on the hydrologic cycle. The amount of water in rivers as well as the variability in river flows, which are regulated by climate, are important predictors of ecosystem structure and variation in biodiversity (Bunn and Arthington, 2002; Poff et al., 1997). River flows and water quality in rivers and lakes are also highly dependent on surrounding landscape vegetation, which controls the rate at which precipitation enters surface water systems as runoff and the amount of particulate matter (e.g., soils, ash, contaminants) entering these systems during precipitation events. The influence of solar radiation, which is a principal determinant of productivity in freshwater systems, is dependent on water clarity and depth, both of which regulate the amount of light penetrating lakes and rivers and supporting plant growth.

While the impacts of nuclear detonation on freshwater systems have not been modeled, volcanic eruptions and wildfires can serve as surrogates for understanding local impacts of intense fires. Volcanic eruptions result in changes in climate, including reductions in air temperature and precipitation. Fires result in a loss of vegetation cover and destabilization of soils, which increases erosion of soils into surface waters, which increases turbidity (Shakesby and Doerr, 2006). In addition to atmospheric deposition of ash, particulate black carbon from fires will also enter rivers and lakes as runoff and increase water turbidity, thus reducing primary production with cascading effects on the entire ecosystem. Consequently, any nuclear detonation has the potential to alter climate and landscape characteristics that can fundamentally alter freshwater ecosystems.

Temperature and nutrients interact with light availability to regulate primary production in freshwater systems. The sensitivity of water temperature to fluctuations in air temperature is governed by an array of physical processes, including the volume of water in the system, the relative contributions of surface water and groundwater, and the vegetation characteristics of the surrounding landscape. Aquatic systems will be affected by both decreases in solar radiation and increases in UV radiation (Harrison and Smith, 2009).

SOURCE: Epstein et al., 1996.

Volcanic eruptions can also serve as a model to understand the local impacts of ash from fires produced by nuclear detonations. The deposition and surface runoff of volcanic ash into surrounding freshwater systems can increase turbidity in lakes and rivers, reducing the penetration of sunlight into the water. This decrease in light availability can in turn reduce photosynthesis, limiting the growth of primary producers such as algae, phytoplankton, and aquatic plants, consequently affecting the overall productivity of freshwater ecosystems. As an example, during the peak eruption period of Mount Saint Helens in the United States in 1980, approximately 540 million tons of ash were released from the volcano into the surrounding area. The resulting ash and erosion and mudslides associated with loss of vegetation led to irreversible alterations to the freshwater landscape (Lee, 1996), erasing stream channels while leading to the formation of new waterways. The chemical composition of deposited ash from volcanic eruptions can alter water chemistry in freshwater systems, and resulting fires can transform soil structure and chemistry (Brucker et al., 2022; Ferrer and Thurman, 2023; Ortiz-Bobea et al., 2021). Precipitation events then result in the mobilization of soil, ash, and contaminants into aquatic systems. Moreover, export of nitrogen and phosphorus after fires has been shown to increase by 250 to 400 times comparted to pre-fire conditions (Bladon et al., 2014; Rhoades et al., 2019), which can result in toxic algal blooms, disruption of ecosystem processes and harming drinking water (Brucker et al., 2022). While long-term recovery (10-30 years) of pre-detonation primary production is likely, the immediate negative impacts to ecosystem productivity would have negative effects on water quality and the provisioning of ecosystems services (e.g., fisheries) to humans)(Hallema et al., 2018; Moazeni and Cerdà, 2024D).

6.3.3 Ocean Ecosystems

In marine ecosystems, primary productivity occurs through photosynthesis by marine phytoplankton in the sunlit upper ocean. This productivity varies greatly across the global ocean owing to variations in local environmental conditions such as temperature, nutrient supply, surface mixed-layer depth, and the presence of sea ice (Fay et al., 2014). At regional scales the patterns of productivity mirror the larger patterns of ocean circulation and the biogeography of phytoplankton. Subtropical biomes, characterized by downwelling and a depressed thermocline and/or nutricline, tend to have low rates of productivity. Whereas subpolar biomes are eutrophic, associated with seasonally deep mixed layers and high productivity rates when light is plentiful, equatorial biomes, characterized by surface divergence and shallow nutriclines, tend to support high productivity rates. Productivity in polar biomes can be very high during the ice-free season.

Studies conducted with Earth system models that include representation of the lowest marine trophic levels (phytoplankton and zooplankton) suggest that certain nuclear war scenarios demonstrate substantial changes in marine primary productivity (Coupe et al., 2021; Harrison et al., 2022; Toon et al., 2019). For a range of regional nuclear war scenarios that inject between 5 and 46.8 Tg of black carbon into the atmosphere, models indicate that the globally integrated ocean NPP declines by 3–20%, with regional decreases of 25–50% for an intermediate conflict (27.3 Tg) in the typically productive North Atlantic and Pacific subpolar biomes (Toon et al., 2019).

Phytoplankton NPP is also responsive to the “nuclear Niño” event induced by the conflicts simulated in the Community Earth System Model (Coupe et al., 2021). Nuclear Niño induces changes in the shape of the tropical Pacific thermocline; it shoals in the western Pacific and deepens in the eastern Pacific, owing to conflict-driven westerly wind anomalies (Coupe et al., 2021). This causes two changes that have impacts on NPP: the eastern Pacific surface becomes anomalously warm (increasing NPP), and iron upwelling slows (decreasing NPP). At the same time, global PAR is reduced due to stratospheric absorption of solar radiation (decreasing NPP). Ultimately, the PAR reductions dominate the phytoplankton response, leading to overall reductions in NPP in the eastern equatorial Pacific biome following nuclear war (Coupe et al., 2021). Changes in NPP here scale with the size of the nuclear war: modeled NPP in this region is typically ~245 g C / m2 yr; with NPP decreasing to 185, 175, and 125 g C / m2 yr, respectively, for the 27.3-Tg, 46.8-Tg, and 150-Tg conflicts simulated in their model.

Global and regional phytoplankton NPP changes and their drivers following nuclear war were explored by Harrison et al. (2022), who analyzed the simulated ocean NPP response to a global nuclear war (150 Tg of soot). Their study demonstrates seasonally and regionally varying responses of NPP to the conflict. In the subpolar North Atlantic 1-2 years post-conflict, they report >50-mmol C / m2 day reduction in NPP in the typically productive spring and summer months. These NPP anomalies are maintained up to 6 years post-conflict, driven by severe light limitation, owing to reduced PAR and deeper mixed layers, and despite the relief in nutrient limitation brought on by the entrainment of nutrients associated with these deeper mixed layers (Harrison et al., 2022). In the Sargasso Sea, on the other hand, the initial NPP reduction of 10 mmol C / m2 day due to light limitation is quickly overcome by 2 years post-conflict, with more intense summertime blooms that persist for 5 additional years owing to a relief in nutrient limitation brought on by post-impact mixed-layer deepening (Harrison et al., 2022).

6.4 BIODIVERSITY CHANGE

6.4.1 Terrestrial Ecosystems

Biodiversity encompasses phenomena at different spatial and temporal scales. Local diversity, or α diversity can be measured as species richness which is the number of species per unit area of a plot. Similarly, ecologists define β and γ diversity as species richness in between plots or regions. Biodiversity at all these levels decreases due to local extinctions and increase due to invasions from other communities. Local extinctions are reversible since plots can be reinvaded. Global extinctions are irreversible.

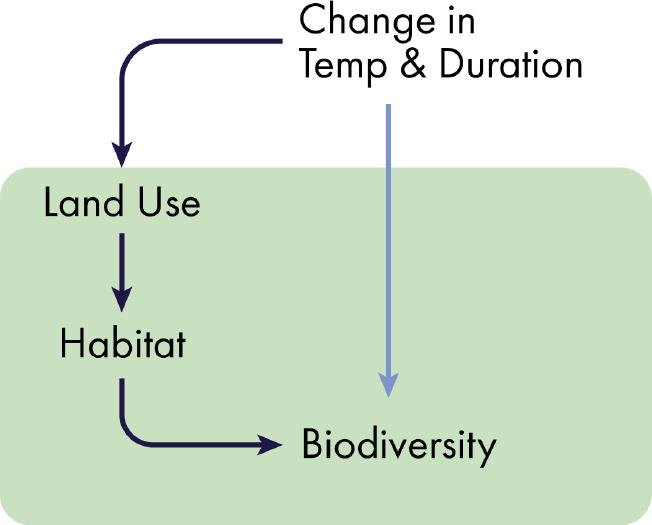

As mentioned in the previous section, the most important variables for evaluating the environmental effects of a nuclear war on the functioning of ecosystems and biodiversity are the change in temperature and the duration of the cooling.

Very cold, punctuated events rarely have a persistent effect on plant communities. Plants and most organisms have numerous strategies for persisting during punctuated disturbance events. Plants have seeds and belowground organs that can allow plants to regrow after severe disturbances. Similarly, animals have forms for resistance such as eggs or larvae and larger mobile animals can rapidly migrate and reintroduce themselves. A remarkable example was a very severe cold episode in New Mexico drylands of –31°C in the early XXI century that lasted only a week and had no effects on abundance and plant community composition (Ladwig et al., 2019).

Duration of the cooling is the important variable when assessing the effects of a nuclear-war climatic effect. It is unknown how long it will take for seed banks or resistance organs to be exhausted. One would expect an interaction between the intensity and the duration of the cooling. Similarly, one would expect a diversity of organismal responses.

Major drivers of biodiversity loss are land use and climate change (Sala et al., 2000). Land use affects biodiversity through reductions in habitat availability. Deforestation and transformation of grasslands into croplands have had a major impact on biodiversity by drastically reducing habitat size for many species. Nuclear war–induced climate change, if it is prolonged, may force abandonment of higher-latitude croplands. Severe cooling may make impossible to continue cultivating traditional crops. Abandonment of these lands may open new habitat for species migrating from cooler regions. Sudden increase in habitat for some species may slow current extinction trends. The other side of this phenomenon is that abandonment of high-latitude cropland may accelerate deforestation in the tropics to offset for croplands lost at high latitudes and sustain food production.

6.4.2 Aquatic Ecosystems

Patterns of global freshwater biodiversity are generally similar to those of terrestrial taxonomic groups. Higher species richness tends to occur in tropical regions with relatively lower species richness occurring at higher latitudes. However, these patterns vary among taxonomic groups (Tisseuil et al., 2013), and local environmental conditions serve as a critical filter regulating biodiversity in rivers and lakes (Heino, 2011). Impacts of nuclear detonation on biodiversity will likely be realized locally through immediate catastrophic impacts of the blast, subsequent shorter-term effects of fires and atmospheric deposition on water quality and primary production, and longer-term impacts on the hydrologic cycle due to alterations in climate. The immediate effects of the blast would likely be largely indiscriminate in terms of taxonomic or trophic position of species; however, some research on fires suggests that species living in deeper waters of lakes may be resilient to immediate and shorter-term impacts of a nuclear exchange.

6.4.3 Ocean Ecosystems

Only a single study has investigated potential biodiversity changes brought on by nuclear war. Harrison et al. (2022) used a fairly simple ecosystem model to document the change in phytoplankton biomass following a global nuclear war (highest limiting amount of 150 Tg of soot). Immediately following the conflict, when PAR is at a minimum, there is a decline in the global biomass of small phytoplankton, such as diatoms, and diazotrophs, the two types of phytoplankton simulated in the model (Harrison et al., 2022). Approximately 1–2 years post-conflict, the surface ocean nutrient concentrations are anomalously elevated, relieving nutrient limitation in the surface ocean. Diatoms, the largest of the phytoplankton types simulated in the model, begin to dominate the global community composition; they briefly have more biomass than small phytoplankton globally before the nutrients are drawn down and small phytoplankton dominate once again (Harrison et al., 2022).

Field and laboratory studies indicate that large shifts in phytoplankton community composition can be expected from sudden environmental change. For example, ocean iron fertilization studies conducted in the 1990s and 2000s suggest that, following the addition of iron, the community shifts away from small phytoplankton and toward larger phytoplankton such as diatoms (e.g., Boyd et. al., 2000).

BOX 6-2

Case Study: Terrestrial Impacts from Mt. Pinatubo

The 1991 eruption of Mount Pinatubo is one of the largest volcanic eruption events in the last 100 years with a TNT equivalent burst of 70 Mt. The event injected roughly 15 million tons of sulfur dioxide into the stratosphere which subsequently reacted with other atmospheric compounds resulting in significant terrestrial impacts:

- Diffuse sunlight increased by 20% but direct sunlight decreased by 21%, resulting in a net 2.5% reduction in total global sunlight (1991–1993) (Proctor et al., 2018).

- This equates to over 6 W/m2 decrease in net solar radiation.

- Global temperatures dropped by 0.5°C between 1991 and 1993.

- Global precipitation decreased substantially over land, and there was a record decrease in runoff and river discharge into the ocean from 1991 to 1992 (Aquila et al., 2021).

- Net primary production (NPP) trends were more complex and varied based on biome and latitude. Biomes that rely more of diffused light saw positive NPP whereas other biomes saw decreased NPP (Krakauer and Randerson, 2003).

BOX 6-3

Case Study: Terrestrial Impacts from Krakatoa

The 1883 eruption of Krakatoa is considered one of the largest eruptions in history, releasing 200 Mt of TNT equivalent energy and destroying roughly 70% of the surrounding area. Following the eruption, the volcano collapsed into the sea resulting in underwater explosions and the displacement of large volumes of water, contributing to the generation of tsunamis. Because of limited historical sampling at that time the full extent of Krakatoa’s 1883 eruption on marine ecosystems remains somewhat speculative, but the resulting emissions from the volcano and the major changes in topography due to explosions and tsunamis would likely have resulted in changes in chemical composition in the marine water and overall biodiversity for some time following the eruption.

SOURCE: “Harvard University | The Harvard Map Collection Presents: Krakatoa, 1883” (accessed November 22, 2023).

BOX 6-4

Case Study: Freshwater Impacts from Mt. Saint Helens

The 1980 eruption of Mt. Saint Helens had a profound impact on the regional freshwater systems surrounding the volcano. Loss of protective vegetation led to more runoff entering waterways. Consequently, massive amounts of debris and sediment clogged river channels, causing a dramatic change in water flow. This additionally caused changes in chemical concentrations in the water, leading to adverse effects on the biodiversity in the area. While the local ecosystems were able to recover in the years following, the immediate impacts caused by these changes resulted in landscape changes still present decades later. The 1980 eruption of Mt. Saint Helens is considered one of the most disastrous volcanic eruptions in U.S. history, releasing roughly 26 Mt of TNT equivalent in thermal energy. During the peak eruption period approximately 540 million tons of ash were released from the volcano into the surrounding area. The resulting ash and destruction of vegetation in the surrounding areas has profound impacts on regional freshwater systems:

- Irreversible changes to waterways occurred leadings to a change in the freshwater landscape (Major et al., 2020).

- Although regional biodiversity was impacted by the eruption there was little lasting change to biodiversity after a 5 years.

- Net primary production was not substantially impacted by the eruption when compared to that from yearly fluctuations in weather (Pfitsch and Bliss, 1988).

Small phytoplankton tend to dominate in oligotrophic regions due to their larger surface area-to-volume ratios, but once nutrients become available, larger phytoplankton can outcompete the smaller plankton. Similarly, laboratory experiments suggest that the optimal growth rates of different phytoplankton species occur at different temperatures (Eppley, 1972); thus one can expect that the sudden temperature changes brought on by nuclear war will also modify phytoplankton community composition. The sudden decrease in □calc that occurs in the surface ocean a few years after nuclear war (Section 6.1.4.2; Lovenduski et al., 2020) is likely to be detrimental to coccolithophores (a type of phytoplankton with calcium carbonate shells) and may cause their populations to decline in favor or other types of phytoplankton. Finally, laboratory studies suggest that the sudden changes in post-nuclear UV radiation (Section 6.1.2; Bardeen et al., 2021) may have a disproportionately negative impact on non-shell-making phytoplankton (see, e.g., Aguirre et al., 2018; Xu et al., 2011, 2016) disrupting biodiversity.

6.5 KEY UNCERTAINTIES AND DATA GAPS

Sudden cooling and its consequences are phenomena that have received relatively little attention compared with the multiple studies of global warming. Most of our understanding of the effects of a nuclear war–induced cooling derives from retrofitting our studies of global warming. However, the cooling from such a nuclear war and the warming from accumulation of greenhouse gases are two different phenomena. The cooling will be sudden with a gradual subsequent warming akin to that which Earth is currently experiencing. The progressive warming would provide multiple opportunities for adaptation by population and communities of organisms. Similarly, society has a window for developing new technologies and governance structures to ameliorate the impact of global warming. Conversely, there would be little or no time for communities of organisms and society to adapt to the sudden onset of planetary cooling.

Our understanding of the effects of a nuclear war on terrestrial ecosystems is limited by the availability of models that simulate rapid planetary cooling. The physics of the relationship of radiation reduction and climate cooling are reasonably clear. However, the impact on terrestrial ecosystems remains unclear because of their broad geographical distribution ranging from temperature-limited to water-limited ecosystems. High-latitude and temperature-limited ecosystems will be negatively impacted by the nuclear-war cooling. However, lower-latitude and water-limited ecosystems may be negatively or positively impacted depending on the seasonality and duration of the changes in climate. Furthermore, terrestrial ecosystems under nuclear war will be directly affected by complex human responses. These land-use changes will range from abandonment of cold and now colder regions to enhanced deforestation in temperate and tropical regions. The speed of the human response is unclear and will depend mostly on the duration of the altered climate.

Little is known about the potential response of freshwater ecosystems to nuclear detonation. The primary inferences that can be made are based on research on the impacts of volcanic eruptions on freshwater systems. While these inferences are useful, a greater understanding of how nuclear war will alter climate, and how these changes will alter the hydrologic cycle, is critical to estimating the impacts of nuclear war on freshwater ecosystems. Moreover, a greater understanding of how contamination resulting from nuclear blasts will become entrained in the hydrologic cycle and the extent of this contamination is fundamentally important to assessing the longer-term environmental and social impacts of nuclear war. This understanding is critical due to the importance of freshwater ecosystems to water and food provisioning as well as human health.

Each of the studies that have investigated changes in marine phytoplankton primary production and biodiversity following nuclear war have been conducted with Earth system models. These models were designed to simulate the modern-day, coupled carbon–climate system and to capture the response of this coupled system to anthropogenic climate change in the coming centuries. The use of these models to probe the sensitivity of phytoplankton to nuclear war introduces a number of uncertainties. Modeled parameters are tuned to present-day ocean conditions and may not accurately simulate the response to the sudden environmental changes brought on by nuclear war. Further, while some models have the capacity

to represent the impact of simultaneous, nuclear-related environmental changes on phytoplankton (e.g., PAR limitation and acidification impacts on NPP; Krumhardt et al., 2019), most Earth system models are unable to capture the response to the multiple, diverse environmental changes simultaneously brought on by nuclear war (e.g., acidification and UV inhibition). Further, the biogeochemical-ecological model components in Earth system models are set within a physical model that itself is an uncertain representation of ocean circulation. Finally, while some ocean ecological models have the capacity to simulate adaptation and evolution in organisms (e.g., Follows et al., 2007), these are rarely included in Earth system models, challenging our ability to accurately predict ecosystem structural changes and biodiversity following nuclear war.

6.6 SUMMARY

The current state of knowledge regarding the ecosystem impacts of nuclear war is primarily based on simulations using Earth system models and analogies to past events such as volcanic eruptions. These studies suggest that nuclear war would lead to substantial reductions in temperature and PAR reaching ecosystems, along with potential increases in harmful UV radiation due to stratospheric ozone depletion. The magnitude and duration of these climatic perturbations would depend on the scale of the nuclear war as described in Chapter 2 scenarios.

For terrestrial ecosystems, the overall impact on NPP is uncertain: cooling may reduce NPP in temperature-limited high-latitude forests by shortening growing seasons but increase NPP in water-limited drylands by lowering evaporative demand more than precipitation declines. In the oceans, cooling would be expected to enhance vertical mixing, transiently increasing surface nutrient levels. Simulations also indicate ocean pH rising initially but calcium carbonate saturation state decreasing on longer timescales. Simulations suggest that regional NPP in the ocean could decline due to severe light limitation from reductions in PAR, despite some temporary blooms in other areas from enhanced nutrient supplies. In freshwater systems such as rivers and lakes, major impacts such algal blooms, biodiversity losses, and disruption of ecosystem services are likely through complex pathways such as ash deposition, shifting hydrology, and changes in water quality.

The impacts on biodiversity remain highly uncertain, but could include local extinctions, habitat shifts, and even new colonization as higher-latitude croplands are abandoned. Abandonment of higher-latitude croplands may stimulate deforestation in lower latitude to offset food supply deficits and with larger negative biodiversity consequences. In freshwater ecosystems, biodiversity would face major pressures from direct blast effects, fires, altered hydrology, and water contamination. In the oceans, modeling studies indicate potential for major restructuring of phytoplankton communities, with some suggestions that larger diatom species could outcompete smaller species during the nutrient-replete but low-light conditions after conflicts owing to their higher nutrient requirements.

Major uncertainties and data gaps persist in assessing the full ecosystem impacts. Key limitations stem from the use of models that are calibrated based on modern conditions and may poorly represent responses to the abrupt, severe perturbations such as prolonged cooling and UV radiation increases. There is also a lack of observational data to validate models of processes such as adaptation, food web disruptions, and synergistic effects of the multiple environmental stressors.

The impacts described here will directly translate into harm to people and society, as elaborated in Chapter 7. Changes in ecosystems and the services they provide, will strongly determine impacts on human health and well-being at the scale of individuals, communities, and societies.

6.7 FINDINGS AND RECOMMENDATIONS

FINDING 6-1: The interactive effects of stratospheric aerosol loading on ultraviolet radiation, photosynthetically active radiation, and diffuse versus direct radiation remain unclear. There is a need for data that can be used to characterize shorter- and longer-term post-detonation

environmental conditions, which can then be applied to ecosystem modeling efforts to project the impacts of detonation on ecosystem functioning and biodiversity.

RECOMMENDATION 6-1: EENW researchers should improve characterization of ultraviolet radiation, photosynthetically active radiation, and diffuse versus direct beam radiation that result from stratospheric aerosol loading and atmospheric chemistry changes following a nuclear detonation scenario.

FINDING 6-2: Most of our studies on climate-induced environmental change are focused on studying implications of slow (century-scale) warming and its consequences on environmental conditions. However, the modeling research groups are short of studies of sudden cooling, as could result from a nuclear exchange scenario, and the associated effects on ecosystems and their components.

RECOMMENDATION 6-2: EENW researchers should develop models that can capture key ecosystem responses to abrupt changes in environmental conditions including sudden decreases in temperature, photosynthetically active radiation, and acidity, and sudden increases in ultraviolet radiation. Key ecosystem processes in this context include net primary production and organismal mortality with the potential to affect community composition. This new generation of models should be able to capture the ecosystem responses to volcanic eruptions and rare climatic extremes including cooling scenarios.

FINDING 6-3: As the intensity and number of nuclear weapon detonations increase, the differential sensitivity across regions is expected to decrease. Similarly, there are differences in irreversibility of ecosystem characteristics after a nuclear event. The impacts on ocean ecosystems are relatively insensitive to the location of the conflict whereas terrestrial and aquatic responses are relatively more sensitive.

RECOMMENDATION 6-3: EENW researchers should focus on the differential response across regions based on their relative sensitivity to detonation-induced variation in environmental factors including water, temperature, precipitation, and solar radiation.

FINDING 6-4: Terrestrial ecosystems responses to nuclear-war climate change will be modulated by current geographical location. Higher-latitude and cold ecosystems will be negatively affected by the cooling and shortening of their growing season expected under nuclear-war climate. However, a large fraction of terrestrial ecosystems that are currently limited by soil-water availability may exhibit an increase in net primary production as a result of regional cooling.

RECOMMENDATION 6-4: EENW researchers should explore the sensitivity of different terrestrial ecosystems to simultaneous changes in precipitation and evapotranspiration, including their location in environmental space.

FINDING 6-5: Under nuclear-war conditions, terrestrial ecosystems will be directly affected by changes in climate and indirectly by changes in land-use.

RECOMMENDATION 6-5: EENW ecologists and social scientists should collaborate in the study of the interactions between nuclear-war climate change and the social response driving deforestation and land abandonment.

FINDING 6-6: Each model of climate warming effects on ecosystems is constructed differently. Exercises in which models were compared while using similar starting condition have been

enlightening. Using this approach to model nuclear exchange scenarios would be similarly informative.

RECOMMENDATION 6-6: The Earth system modeling community should increase the number of models used to explore radiative climate and ecosystem responses to a nuclear event and increase the availability of model simulation output following findable, accessible, interoperable, and reusable data principles through a coupled modeled intercomparison project, in support of accelerating studies of the response of organisms and populations to abrupt changes in environmental conditions including a cooling scenario.

6.8 REFERENCES

Aguirre, L. E., L. Ouyang, A. Elfwing, M. Hedblom, A. Wulff, and O. Inganäs. 2018. Diatom frustules protect DNA from ultraviolet light. Scientific Reports 8(1):5138. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-21810-2.

Aquila, V., C. Baldwin, N. Mukherjee, E. Hackert, F. Li, J. Marshak, A. Molod, and S. Pawson. 2021. Impacts of the Eruption of Mount Pinatubo on Surface Temperatures and Precipitation Forecasts With the NASA GEOS Subseasonal-to-Seasonal System. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 126(16):e2021JD034830. https://doi.org/10.1029/2021JD034830.

Bardeen, C. G., D. E. Kinnison, O. B. Toon, M. J. Mills, F. Vitt, L. Xia, J. Jägermeyr, N. S. Lovenduski, K. J. N. Scherrer, M. Clyne, and A. Robock. 2021. Extreme Ozone Loss Following Nuclear War Results in Enhanced Surface Ultraviolet Radiation. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 126(18):e2021JD035079. https://doi.org/10.1029/2021JD035079.

Bladon, K. D., M. B. Emelko, U. Silins, and M. Stone. 2014. Wildfire and the Future of Water Supply. Environmental Science & Technology 48(16):8936-8943. https://doi.org/10.1021/es500130g.

Boyd, P. W., A. J. Watson, C. S. Law, E. R. Abraham, T. Trull, R. Murdoch, D. C. E. Bakker, A. R. Bowie, K. O. Buesseler, H. Chang, M. Charette, P. Croot, K. Downing, R. Frew, M. Gall, M. Hadfield, J. Hall, M. Harvey, G. Jameson, J. LaRoche, M. Liddicoat, R. Ling, M. T. Maldonado, R. M. McKay, S. Nodder, S. Pickmere, R. Pridmore, S. Rintoul, K. Safi, P. Sutton, R. Strzepek, K. Tanneberger, S. Turner, A. Waite, and J. Zeldis. 2000. A mesoscale phytoplankton bloom in the polar Southern Ocean stimulated by iron fertilization. Nature 407(6805):695-702. https://doi.org/10.1038/35037500.

Brucker, C. P., B. Livneh, J. T. Minear, and F. L. Rosario-Ortiz. 2022. A review of simulation experiment techniques used to analyze wildfire effects on water quality and supply. Environmental Science: Processes & Impacts 24(8):1110-1132. https://doi.org/10.1039/D2EM00045H.

Bunn, S. E., and A. H. Arthington. 2002. Basic Principles and Ecological Consequences of Altered Flow Regimes for Aquatic Biodiversity. Environmental Management 30(4):492-507. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00267-002-2737-0.

Christiansen, D. E., S. L. Markstrom, and L. E. Hay. 2011. Impacts of Climate Change on the Growing Season in the United States. Earth Interactions 15(33):1-17. https://doi.org/10.1175/2011EI376.1.

Coupe, J., S. Stevenson, N. S. Lovenduski, T. Rohr, C. S. Harrison, A. Robock, H. Olivarez, C. G. Bardeen, and O. B. Toon. 2021. Nuclear Niño response observed in simulations of nuclear war scenarios. Commun Earth Environ 2(1). https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-020-00088-1.

Eppley, R. 1972. Temperature and Phytoplankton Growth in the Sea. Fishery Bulletin 70(4):1063-1085.

Epstein, H. E., W. K. Lauenroth, I. C. Burke, and D. P. Coffin. 1996. Ecological responses of dominant grasses along two climatic gradients in the Great Plains of the United States. Journal of Vegetation Science 7(6):777-788. https://doi.org/10.2307/3236456.

Fay, A. R., G. A. McKinley, and N. S. Lovenduski. 2014. Southern Ocean carbon trends: Sensitivity to methods. Geophysical Research Letters 41(19):6833-6840. https://doi.org/10.1002/2014GL061324.

Ferrer, I., and E. M. Thurman. 2023. Chemical tracers for Wildfires–Analysis of runoff surface Water by LC/Q-TOF-MS. Chemosphere 339:139747. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chemosphere.2023.139747.

Follows, M. J., S. Dutkiewicz, S. Grant, and S. W. Chisholm. 2007. Emergent Biogeography of Microbial Communities in a Model Ocean. Science 315(5820):1843-1846. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1138544.

Guo, S., G. J. S. Bluth, W. I. Rose, I. M. Watson, and A. J. Prata (2004), Re-evaluation of SO2 release of the 15 June 1991 Pinatubo eruption using ultraviolet and infrared satellite sensors, Geochem. Geophys. Geosyst., 5, Q04001. https://doi.org/10.1029/2003GC000654.

Hallema, D.W., Sun, G., Caldwell, P.V. et al. Burned forests impact water supplies. Nat Commun 9, 1307 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-018-03735-6.

Harrison, C. S., T. Rohr, A. DuVivier, E. A. Maroon, S. Bachman, C. G. Bardeen, J. Coupe, V. Garza, R. Heneghan, N. S. Lovenduski, P. Neubauer, V. Rangel, A. Robock, K. Scherrer, S. Stevenson, and O. B. Toon. 2022. A New Ocean State After Nuclear War. AGU Advances 3(4):e2021AV000610. https://doi.org/10.1029/2021AV000610.

Harrison, J. W., and R. E. H. Smith. 2009. Effects of ultraviolet radiation on the productivity and composition of freshwater phytoplankton communities. Photochemical & Photobiological Sciences 8(9):1218-1232. https://doi.org/10.1039/B902604E.

Harvard University. n.d. The Harvard Map Collection Presents: Krakatoa, 1883. https://archive.blogs.harvard.edu/wheredisasterstrikes/volcano/krakatoa-1883/ (accessed July 29, 2024).

Heino, J. 2011. A macroecological perspective of diversity patterns in the freshwater realm. Freshwater Biology 56(9):1703-1722. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2427.2011.02610.x.

Krakauer, N. Y., and J. T. Randerson. 2003. Do volcanic eruptions enhance or diminish net primary production? Evidence from tree rings. Global Biogeochemical Cycles 17(4):1118. https://doi.org/10.1029/2003GB002076.

Krumhardt, K. M., N. S. Lovenduski, M. C. Long, M. Levy, K. Lindsay, J. K. Moore, and C. Nissen. 2019. Coccolithophore Growth and Calcification in an Acidified Ocean: Insights From Community Earth System Model Simulations. Journal of Advances in Modeling Earth Systems 11(5):1418-1437. https://doi.org/10.1029/2018MS001483.

Ladwig, L. M., S. L. Collins, D. J. Krofcheck, and W. T. Pockman. 2019. Minimal mortality and rapid recovery of the dominant shrub Larrea tridentata following an extreme cold event in the northern Chihuahuan Desert. Journal of Vegetation Science 30(5):963-972. https://doi.org/10.1111/jvs.12777.

Lee, D. B. 1996. Effects of the Eruption of Mount St. Helens on Physical, Chemical, and Biological Characteristics of Surface Water, Ground Water, and Precipitation in the Western United States. U.S. Department of the Interior.

Lovenduski, N. S., C. S. Harrison, H. Olivarez, C. G. Bardeen, O. B. Toon, J. Coupe, A. Robock, T. Rohr, and S. Stevenson. 2020. The Potential Impact of Nuclear Conflict on Ocean Acidification. Geophys. Res. Lett. 47(3):e2019GL086246. https://doi.org/10.1029/2019GL086246.

Major, J. J., C. M. Crisafulli, and F. J. Swanson. 2020. Lessons from a post-eruption landscape. 101: 34-40.

Maurer, G. E., A. J. Hallmark, R. F. Brown, O. E. Sala, and S. L. Collins. 2020. Sensitivity of primary production to precipitation across the United States. Ecology letters 23(3):527-536. https://doi.org/10.1111/ele.13455.

Mills, M. J., O. B. Toon, J. Lee-Taylor, and A. Robock. 2014. Multidecadal global cooling and unprecedented ozone loss following a regional nuclear conflict. Earth’s Future 2(4):161-176. https://doi.org/10.1002/2013EF000205.

Moazeni, S., & Cerda, A. (2024). The impacts of forest fires on watershed hydrological response. A review. Trees, Forests and People, 100707. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tfp.2024.100707.

NRC (National Research Council). 1985. “The Effects on the Atmosphere of a Major Nuclear Exchange.” Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. https://doi.org/10.17226/540.

Ortiz-Bobea, A., T. R. Ault, C. M. Carrillo, R. G. Chambers, and D. B. Lobell. 2021. Anthropogenic climate change has slowed global agricultural productivity growth. Nature Climate Change 11(4):306-312. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41558-021-01000-1.

Pfitsch, W. A., and L. C. Bliss. 1988. Recovery of net primary production in subalpine meadows of Mount St. Helens following the 1980 eruption. Canadian Journal of Botany 66(5):989-997. https://doi.org/10.1139/b88-142.

Poff, N. L., J. D. Allan, M. B. Bain, J. R. Karr, K. L. Prestegaard, B. D. Richter, R. E. Sparks, and J. C. Stromberg. 1997. The Natural Flow Regime. BioScience 47(11):769-784. https://doi.org/10.2307/1313099.

Proctor, J., S. Hsiang, J. Burney, M. Burke, and W. Schlenker. 2018. Estimating global agricultural effects of geoengineering using volcanic eruptions. Nature 560(7719):480-483. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-018-0417-3.

Rhoades, C. C., A. T. Chow, T. P. Covino, T. S. Fegel, D. N. Pierson, and A. E. Rhea. 2019. The Legacy of a Severe Wildfire on Stream Nitrogen and Carbon in Headwater Catchments. Ecosystems 22(3):643-657. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10021-018-0293-6.

Robock, A., L. Oman, and G. L. Stenchikov. 2007a. Nuclear winter revisited with a modern climate model and current nuclear arsenals: Still catastrophic consequences. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 112(D13):D13107. https://doi.org/10.1029/2006JD008235.

Robock, A., L. Oman, G. L. Stenchikov, O. B. Toon, C. Bardeen, and R. P. Turco. 2007b. Climatic consequences of regional nuclear conflicts. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 7(8):2003-2012. https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-7-2003-2007.

Sala, O. E., F. S. Chapin, 3rd, J. J. Armesto, E. Berlow, J. Bloomfield, R. Dirzo, E. Huber-Sanwald, L. F. Huenneke, R. B. Jackson, A. Kinzig, R. Leemans, D. M. Lodge, H. A. Mooney, M. Oesterheld, N. L. Poff, M. T. Sykes, B. H. Walker, M. Walker, and D. H. Wall. 2000. Global biodiversity scenarios for the year 2100. Science 287(5459):1770-1774. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.287.5459.1770.

Shakesby, R. A., and S. H. Doerr. 2006. Wildfire as a hydrological and geomorphological agent. Earth-Science Reviews 74(3-4):269-307. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.earscirev.2005.10.006.

Sigl, M., M. Winstrup, J. R. McConnell, K. C. Welten, G. Plunkett, F. Ludlow, U. Büntgen, M. Caffee, N. Chellman, D. Dahl-Jensen, H. Fischer, S. Kipfstuhl, C. Kostick, O. J. Maselli, F. Mekhaldi, R. Mulvaney, R. Muscheler, D. R. Pasteris, J. R. Pilcher, M. Salzer, S. Schüpbach, J. P. Steffensen, B. M. Vinther, and T. E. Woodruff. 2015. Timing and climate forcing of volcanic eruptions for the past 2,500 years. Nature 523(7562):543-549. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature14565.

Tahira, M., M. Nomura, Y. Sawada, and K. Kamo. 1996. Infrasonic and acoustic-gravity waves generated by the Mount Pinatubo eruption of June 15, 1991. Fire and Mud: eruptions and lahars of Mount Pinatubo, Philippines 601-614.

Tisseuil, C., J.-F. Cornu, O. Beauchard, S. Brosse, W. Darwall, R. Holland, B. Hugueny, P. A. Tedesco, and T. Oberdorff. 2013. Global diversity patterns and cross-taxa convergence in freshwater systems. Journal of Animal Ecology 82(2):365-376. https://doi.org/10.1111/1365-2656.12018.

Toon, O. B., A. Robock, and R. P. Turco. 2008. Environmental consequences of nuclear war. Phys. Today 61(12):37-42. https://doi.org/10.1063/1.3047679.

Toon, O. B., C. G. Bardeen, A. Robock, L. Xia, H. M. Kristensen, M. G. McKinzie, R. J. Peterson, C. S. Harrison, C. S. Harrison, N. S. Lovenduski, and R. P. Turco. 2019. Rapidly expanding nuclear arsenals in Pakistan and India portend regional and global catastrophe. Science Advances 5(10):eaay5478. https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.aay5478.

Xia, L., A. Robock, K. Scherrer, C. S. Harrison, B. L. Bodirsky, I. Weindl, J. Jägermeyr, C. G. Bardeen, O. B. Toon, and R. Heneghan. 2022. Global food insecurity and famine from reduced crop, marine fishery and livestock production due to climate disruption from nuclear war soot injection. Nature Food 3(8):586-596. https://doi.org/10.1038/s43016-022-00573-0.

Xu, J., L. T. Bach, K. G. Schulz, W. Zhao, K. Gao, and U. Riebesell. 2016. The role of coccoliths in protecting Emiliania huxleyi against stressful light and UV radiation. Biogeosciences 13(16):4637-4643. https://doi.org/10.5194/bg-13-4637-2016.

Xu, K., K. Gao, V. Villafañe, and E. Helbling. 2011. Photosynthetic responses of Emiliania huxleyi to UV radiation and elevated temperature: roles of calcified coccoliths. Biogeosciences Discussions 8:1441-1452. https://doi.org/10.5194/bg-8-1441-2011.