Potential Environmental Effects of Nuclear War (2025)

Chapter: 1 Introduction

1

Introduction

1.1 BACKGROUND AND STUDY MOTIVATION

At the outset of the Cold War and the dawn of the era of nuclear competition, the United States and the Soviet Union worked quickly to develop large stockpiles of weapons and to demonstrate the power of their nuclear arsenals as a means of deterring a future nuclear war. In time, public concerns over the large numbers of nuclear weapons gave impetus to diplomatic efforts to reduce the threat of a nuclear war and to scientific and research activities to better understand the broader consequences of such a conflict, including ancillary environmental, health, and societal and economic effects beyond just the immediate military outcomes.

In the diplomatic sphere, concerns over the health and environmental effects of nuclear testing, particularly the radioactive fallout from aboveground detonations, led the United States, the Soviet Union, and the United Kingdom to negotiate the Limited Test Ban Treaty in 1963, prohibiting nuclear testing in the atmosphere, outer space, and underwater. To limit the further spread of nuclear weapons to additional countries, the international community also negotiated the Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons (NPT) in 1968. Since its entry into force in 1970, the NPT has remained a central pillar of international efforts to prevent the spread of nuclear weapons, promote cooperation on peaceful uses of nuclear energy, and advance the goal of global nuclear disarmament. Subsequent major frameworks, such as the Comprehensive Nuclear-Test-Ban Treaty in 1996 (which has not entered into force) and the series of Strategic Arms Reduction Treaties (START) between the United States and Russia, have built on the NPT’s foundations (DOS, 2023). Despite being widely adopted by 191 state parties, the NPT ultimately did not succeed in halting nuclear proliferation entirely, and Russia has recently suspended its participation in the New START Treaty (DOS, 2024). Additional countries have gone on to develop nuclear arsenals outside the NPT framework, and international concerns persist about potential undeclared nuclear programs in some NPT signatory states. These stockpile numbers underpin scenarios used for modeling nuclear exchanges in studies starting in 1975.

In parallel to these developments, scientific research was also spurred by the growth of environmental and antinuclear movements in the 1960s–1970s, which raised concerns about widespread, deleterious effects on people and society resulting from the immediate destruction and ensuing radioactive fallout and pollution caused by nuclear detonations and a potential global nuclear war. American and Soviet scientists independently began studying the potentially irreversible, detrimental effects of nuclear war, and seminal studies in the 1980s introduced the concept of “nuclear winter,” in which the particulate emissions from the immense fires generated by a large-scale nuclear exchange were projected to blanket the upper atmosphere, reflect incoming solar radiation back into space, and create a catastrophic global cooling effect (Aleksandrov and Stenchikov, 1983; Crutzen and Birks, 1982; NRC, 1985; Pittock et al., 1986; Turco et al., 1983). Such resulting disruptions to agriculture and ecosystems could potentially debilitate societies across the planet, even in regions far removed from the conflict itself (Harwell and Hutchinson, 1986).

The Treaty between the United States of America and the Russian Federation on Measures for the Further Reduction and Limitation of Strategic Offensive Arms (also called the “New START”; Arms Control Association, 2024) entered into force in February 2011 and was extended through February 4, 2026, although Russia and the United States are no longer fulfilling all of its provisions. The treaty placed verifiable limits on Russian- and U.S.- deployed intercontinental-range nuclear weapons, both warheads and delivery vehicles, to enhance U.S. and Russian national security. New START limits each country to no more than 1,550 deployed strategic warheads. These do not include weapons in reserve or nonstrategic

BOX 1-1

Historical Nuclear Bombings

The atomic bombings of the Japanese cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki in World War II provide foundational, historical examples of the direct urban devastation and harm to the environment resulting from the use of nuclear weapons, along with the follow-on consequences for people and society. From these events it is clear that nuclear war will result in the destruction of infrastructure, vegetation, and human life in and around the blast zones, and that these blasts will generate fires and associated emissions of particulates and pollutants into the atmosphere. The evolution and transport of these emissions will depend on the energetics and chemistry of the fires, potentially producing environmental effects at regional and global scales. Similarly, the pollutants produced by the fires will contaminate soil and water regionally with the potential for dispersion farther afield.

Although it is unclear whether the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki had global environmental effects (Robock, 2018), they did produce acute and prolonged local environmental impacts with very substantial societal, economic, and health consequences. Even though this report does not focus on radiation health effects or the deaths directly attributable to the blasts from nuclear weapons, the committee would have been remiss if it did not somberly acknowledge the human repercussions of the bombings in Japan. The immediate death toll of the events is still disputed, but it is estimated to have been on the order of 100,000 to 200,000 people, with subsequent health effects due to radiation exposure and fallout contamination pushing that number even higher (Atomic Archive, n.d.; The New York Times, 1949; Ozasa et al., 2018). Survivors of the atomic bombings experienced statistically significant long-term adverse health effects including excess in both cancerous and noncancerous outcomes from their exposure to nuclear weapon radiation (Atomic Archive, n.d.). The sociopolitical outcomes of these bombings were such that the current global practices and policies on nuclear war reflect the hope that it is never experienced again.

nuclear weapons. Each country verified the other’s compliance with these limits through inspections and other means. On February 21, 2023, Russian President Vladimir Putin announced Russia’s suspension of participation in the treaty, although not withdrawal from it, citing the U.S. stated goal of strategic defeat of Russia in its war on Ukraine (Reuters, 2023). Weapons inspections are no longer conducted for treaty verification.

In its annual treaty compliance report, the U.S. Department of State (DOS, 2024) stated “Although the United States cannot certify that the Russian Federation is in compliance with the terms of the New START Treaty, the United States does not determine … that Russia’s noncompliance specified in this report threatens the national security interests of the United States.”

In the intervening years since the concept of nuclear winter was first introduced, the geopolitical, military, and technological landscape surrounding nuclear weapons has shifted profoundly. The number of nuclear-armed nations has grown, and the nature of nuclear weapon stockpiles and systems has evolved such that smaller and more regionalized nuclear exchanges have become a plausible scenario in addition to the prospect of a large-scale global conflict (Mills et al., 2014). Moreover, modern warfare tactics and strategies, urban development patterns, and land-use dynamics have transformed the likely target environment substantially from its Cold War era conditions used to determine emissions in earlier nuclear winter studies, as discussed in Chapter 2. At the same time, the scientific understanding of complex Earth system processes such as climate variability and change, the fate and transport of environmental contaminants, and human–ecosystem interactions has also advanced significantly.

Recent assessments of the potential environmental and societal and economic consequences of nuclear war have made use of higher-fidelity modeling and improved process knowledge (Bardeen et al., 2021; Mills et al., 2014; Redfern et al., 2021; Tarshish and Romps, 2022; Wagman et al., 2020). Fundamental questions remain, however, around many of the key assumptions and mechanisms factored into nuclear war projections, including the basic parameters of nuclear weapons employment in a given conflict. Another continuing area of uncertainty is the amount, composition, and evolution of particulate matter injected into the stratosphere, as such suspended material can persist for years and spread globally, with widespread and long-lasting impacts on sunlight, temperature, climate and weather patterns, ozone, and air quality.

BOX 1-2

Statement of Task

An ad hoc committee will provide an independent review of the potential environmental effects and socioeconomic consequences that could unfold in the weeks-to-decades following nuclear wars. It will explore scenarios ranging from small-scale regional nuclear exchanges to large-scale exchanges between major powers. The study will consider non-fallout atmospheric, terrestrial, and marine effects and their consequences, including changes in climate and weather patterns, airborne particulate concentrations, stratospheric ozone, agriculture, and their impacts on ecosystems.

The committee will conduct the study in two phases, which will proceed in parallel.

Phase 1: The first phase will require access to classified information, and thus will involve only those members of the committee who have necessary clearances. An interim report (classified version and unclassified summary) will be produced addressing the following elements of the task:

- Evaluate the modeling and assumptions that may be used to generate the source terms for particulates and other material released or mobilized into the atmosphere as a result of nuclear detonations.

The unclassified summary of the interim report will use a parametric approach to present results, and will not include information about specific scenarios.

Phase 2: The second phase will be fully unclassified, using the unclassified summary of Phase 1 as input where needed. A final report of the committee will be issued, addressing the following:

- A representative set of explosive yields, general type, and number of nuclear weapons.

- Review the understanding of and tools for simulating the characteristics of fires such explosions may cause and quantity and characteristics of soot and other material mobilized by the explosions.

- Review the understanding of and tools for simulating the characteristics and mechanisms for transport of the source material to the troposphere and stratosphere including the quantities, altitudes, and durations of the flow of materials.

- Review the understanding of and tools for simulating the climate and environmental effects of nuclear explosions months to decades after the event, at regional to global scales.

- Review the understanding of and methods to estimate the socio-economic consequences of environmental effects from such nuclear explosion events including implications for agriculture, terrestrial and marine ecosystem services, and human health.

- Discuss the capabilities and limitations of the models above, including:

- identification of the relevant uncertainties;

- listing of the key data gaps; and

- recommendations for how such models can be improved to better inform decision making.

In light of these uncertainties and the contradictions that exist across the recent scientific literature and given the profound changes that occurred over more than 35 years in both the nuclear and scientific landscapes, the U.S. Congress called for a comprehensive review of the tools and knowledge base for evaluating potential environmental consequences of nuclear war. Section 3171 of the National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2021 directed the U.S. Department of Energy’s National Nuclear Security Administration to commission a study by the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine that reevaluates and updates the body of scientific knowledge on this critical issue. The study’s formal statement of task, outlined in Box 1-2, calls for an authoritative assessment of modern data, research, and modeling capabilities to understand the large-scale environmental effects and societal and economic consequences across different nuclear war scenarios. With growing risks of nuclear proliferation and evolving warfare doctrines, this renewed scientific examination aims to quantify the grave global stakes should such hostilities occur in the current and future security environments. This report aims to contextualize existing literature and identify uncertainties in models that can be and have

been used to describe the causal pathway of impacts from nuclear weapon exchanges and to highlight gaps in data and process understanding.

1.2 STUDY SCOPE AND APPROACH

BOX 1-3

Crosscutting Terms

Aerosol: Any solid or liquid droplets suspended in the atmosphere.

Nuclear Detonation: Premeditated deliberate use and blast of a nuclear weapon.

Nuclear Employment Scenario: Context and framework for how a single or multiple nuclear weapon exchange(s) between countries could play out.

Nuclear Exchange: Employment of one or more nuclear weapons between nuclear weapon states.

Nuclear Explosion: Large blast resulting from the rapid nuclear reactions and uncontrolled release of energy from nuclear materials inside a nuclear weapon capable of fission and fusion reactions.

Nuclear Weapon: Explosive device that derives its destructive force from nuclear reactions, either through the splitting of atomic nuclei (a fission reaction) or the fusing of atomic nuclei (a fusion reaction). Fission weapons, commonly known as atomic bombs, release energy by splitting heavy atomic nuclei such as uranium or plutonium. Fusion weapons, also called thermonuclear or hydrogen bombs, use fission reactions to initiate the subsequent fusion of light atomic nuclei from isotopes of hydrogen, releasing far more energy. The energy released by a nuclear weapon is often expressed in terms of mass of TNT equivalence, with units of kilotons (kt) or megatons (Mt).

Particulate Black Carbon (BC): Black carbon particles, or aerosol. This material absorbs light.

Smoke: Airborne solid and liquid particulates and gases evolved when a material undergoes pyrolysis or combustion, and often used as an informal term for a fire-emitted aerosol (NFPA, 2021).

Soot1: Black particles of carbon produced in a flame (NFPA, 2021).

With this report, the committee has specifically addressed Phase 2 of the study statement of task (see Box 1-2) and has constrained its work in two important respects. First, the committee has not addressed the direct effects of radiation and radioactive fallout produced by nuclear detonations, except insofar as they alter relevant environmental processes. Second, while the committee was charged with identifying “a representative set of explosive yields, general type, and number of nuclear weapons” that may be plausibly employed in nuclear weapon exchanges, it has not explicitly connected any of the described nuclear employment scenarios to their environmental or societal and economic outcomes. That is, the committee has not performed any modeling or quantification of the emissions from potential fires resulting from nuclear detonations; any of the climatic or ecosystem effects; or any specific consequences for agriculture, ecosystem services, or human health. In evaluating the current scientific understanding

___________________

1 There is a diversity of technical terminology used to identify combustion products across multiple disciplines. The definitions used in this report are sufficiently broad to be applicable across different chapters, however, the committee acknowledged that practitioners in specific research communities may use more precise definitions. For example, in the field of soot formation, soot is, “carbonaceous particles formed during the incomplete combustion or pyrolysis of hydrocarbons, including incipient soot particles, mature soot particles, and all of the intermediate particulate stages between inception, maturity, and complete oxidation to gas-phase species” (Michelsen et al., 2020).

and ability to simulate the outcome of a given nuclear employment scenario, this report focuses its discussion on examining the current state of knowledge, identifying key uncertainties, and offering findings and recommendations for best practices for future research.

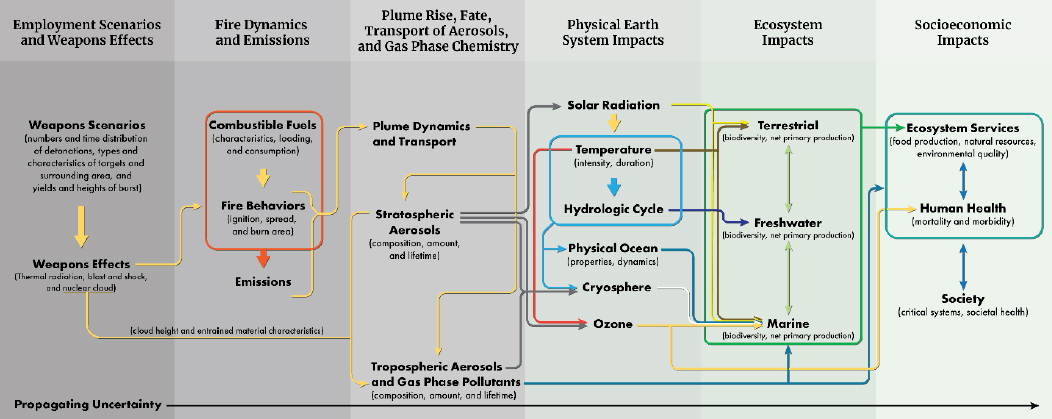

It is important to bear in mind that uncertainties are involved in the analysis of every step of the causal pathway that leads from a nuclear weapons exchange to its environmental and societal and economic endpoints (see Figure 1-1). Moreover, these uncertainties will take different forms at every step and will also interact with each other and propagate along the pathway, such that, regardless of the relative certainty of knowledge at any one point, the overall analytical uncertainty will always increase along the pathway. Fundamentally, uncertainties arise from the lack of observational data, from inadequate understanding of complex natural and human processes, and from basic limitations in modeling capabilities. With respect to observational data, there are, fortunately, few examples of nuclear weapons use in a conflict (see Section 1.3), and so this report relies instead on analogs from various disasters—including wildfires, volcanic eruptions, and famines—that have occurred throughout history. These analogs provide important insights that have informed the committee’s recommendations, but they are inherently imperfect representations of the natural and human systems behavior that would follow from a nuclear war.

In the course of its work, the committee invited speakers to present on existing research that has analyzed the potential environmental effects of a nuclear weapons exchange and related phenomena. These speakers included David Bader, Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory; Lee Glascoe, Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory; Alexander Brown, Sandia National Laboratories; Manvendra Dubey, Los Alamos National Laboratory; Alan Robock, Rutgers University; Owen Brian Toon, University of Colorado Boulder; Feroz Khan, Naval Postgraduate School; Christopher Yeaw, National Strategic Research Institute; Pengfei Yu, Jinan University; Charles Bardeen, National Center for Atmospheric Research; Tami Bond, Colorado State University; Alex Ruane, NASA Goddard Institute for Space Studies; Jonas Jägermeyr, Columbia University and NASA Goddard Institute for Space Studies; Fernando Rosario-Ortiz, University of Colorado Boulder; Channing Arndt, International Food Policy Research Institute; Jae Edmonds, Pacific Northwest National Laboratory; James Cooley, Los Alamos National Laboratory; and Jon Reisner, Los Alamos National Laboratory.

BOX 1-4

Causal Pathway

The causal pathway from a nuclear weapons exchange to societal and economic impacts has been divided into six categories: employment scenarios; fire dynamics and emissions; plume rise, fate, transport of aerosols and gas-phase chemistry; physical Earth system impacts; ecosystem impacts; and societal and economic impacts.

The weapons effects, or outcomes of a weapons employment scenario depend on number and time distribution of the detonations, types and characteristics of targets and the surrounding area, and the weapons yield and height of burst. The weapons effects of relevance to this study include thermal radiation, blast and shock, and nuclear cloud.

Weapons effects have both direct and indirect effects on atmospheric aerosols. Direct effects come from the nuclear cloud and may result in tropospheric particulates or, in a yield-dependent manner, direct injection into the stratosphere. Indirectly, depending on the combustible material in the target location and resultant fire behavior, a fire plume can also inject particulate matter into the troposphere or stratosphere.

Stratospheric aerosols have a direct impact on solar radiation, attenuating the sunlight, which has immediate effects on surface temperature and the hydrologic cycle. At a longer timescale, this then affects the physical properties and dynamics of the ocean as well as the cryosphere. The temperature changes and stratospheric aerosols also have a direct effect on ozone chemistry. Each of these physical Earth systems have direct effects on one or more of the major ecosystems (terrestrial, freshwater, and marine). Tropospheric aerosols can also impact the cryosphere and ecosystems (terrestrial, freshwater, and marine) more locally as well as directly affecting ecosystem services and human health.

The major ecosystems have feedback impacts on each other, directly or indirectly, and all impacts on them will affect ecosystem services. Ecosystem services also interplay with human health and society writ large.

1.3 PREVIOUS WORK ON ENVIRONMENTAL EFFECTS OF NUCLEAR WAR

As noted above, there have been many efforts over the last 50 years to evaluate the potential environmental outcomes of nuclear weapon exchanges. These investigations have varied significantly in terms of the employment scenarios used and analytical techniques applied, particularly as computational tools and process understanding have improved and the actors, strategies, and nature and number of weapons have changed. A detailed technical comparison between the historical analyses is therefore difficult to make, and additional analyses are indicated.

The investigation of the environmental and societal and economic consequences of a nuclear war entails two basic tasks: (1) evaluating the creation, transport, and fate of particulate matter, or source terms, from the nuclear detonations and resulting fires into the atmosphere and (2) evaluating the impact of this particulate matter on the physical Earth system, ecological systems, and, ultimately, society. Given the large intrinsic uncertainties surrounding nuclear exchange scenarios, insights can be gleaned by evaluating the latter for a wide range of results from the former. Existing studies have not yet explored the whole parameter space and results are not always comparable.

In 1982, through an invited contribution to a nuclear war effects project sponsored by the Swedish Academy of Sciences to the journal Ambio, Paul Crutzen and John Birks triggered a new interest in the potential environmental and climatic effects of the smoke generated by nuclear weapon detonations and resulting fires (Crutzen and Birks, 1982). Crutzen and Birks evaluated two scenarios, one with 5,750 Mt total yield and a NOx distribution described by a table of latitudes and altitudes; and the other with a total yield of 10,000 Mt distributed evenly between 20º and 60º in the Northern Hemisphere with equal quantities of NOx in the troposphere and stratosphere. Based on wildland fires lasting 2 months and resulting smoke emissions, Crutzen and Birks projected 200-400 Tg of aerosol over half of the Northern Hemisphere, decreasing average penetration of sunlight to the ground by a factor ranging from 2 to 150 at noon during the summer.

Turco et al. (1983) extended the analysis to characterize urban fires and smoke, carrying out a series of climate perturbation calculations based on radiative transfer techniques. Turco et al. evaluated scenarios ranging from 100 to 25,000 Mt of total yield, including both dust raised by surface bursts (varying from 0.1 to 0.3 Tg/Mt2), and smoke emissions from urban and wildland fires (a total of about 225 Tg of smoke in their baseline scenario of 5,000 Mt, with about 52% of the smoke from urban-suburban fires, 6% from firestorms in city centers, another 6% from long-term fires at fossil fuel sources, and 34% from wildfires; roughly 5% of all the smoke was injected at stratospheric heights, with 30% of the smoke consisting of black carbon [BC] and 70% organic carbon [OC]).3 The baseline case resulted in predicted temperature minimums of about −23ºC on continental landmasses in the Northern Hemisphere, (corresponding to a maximum absolute temperature drop of ~35ºC at continental interiors taken to be moderated by ocean influences by 30%). The near-term vertical optical depths ranged from ~0.5 to 20, persisting for roughly 3–4 weeks after a major exchange, depending on the scenario and smoke/dust scavenging assumptions (noting that optical depth is a useful measure of the capacity for atmospheric particulates to block sunlight).

The 1985 NRC report used a baseline nuclear exchange case of 6,500 Mt total weapon yield and projected that 0.2-0.5 Tg/Mt of dust would be lofted into the atmosphere for surface bursts, with the most likely value of roughly 0.3 Tg/Mt for 0.5 to 1.0 Mt yields (NRC, 1985). Additional scenarios were considered that varied the number of detonations from both the U.S. and USSR stockpiles, studying a range of 3,890–10,600 Mt total weapon yields. Smoke emission was evaluated based on fuel loading whether urban or forest fires, resulting in 20–650 Tg from smoke for all scenario, with 180 Tg of smoke generated from the baseline scenario. Similarly to assessments by Pittock et al. (1986), the modeled temperature decrease ranged from 10 ºC to 20 ºC, reaching these minima at times ranging from 10 to 25 days after the initial nuclear exchange.

In 1984, the International Council of Scientific Unions tasked the Scientific Committee on Problems of the Environment to conduct a study of the Environmental Consequences of Nuclear War. The resulting report was published in two comprehensive volumes: Pittock et al. (1986) and Harwell and Hutchinson (1986). The first volume considered scenarios and physical consequences of a major nuclear war involving the nuclear arsenals of that era. The second volume addressed the human and environmental sequela of such a war, including the direct and indirect effects on agriculture, the biosphere, and national populations worldwide. The reader is referred to these reports for further details. A subsequent review and update of these early nuclear winter research studies was published by Turco et al. (1990).

Toon et al. (2007) evaluated smoke emissions based on a fuel burden per person of 1.1 × 107 g/person,4 assuming 100 weapons (50 detonated in each country) with 15-kt yield each are detonated in highly populous urban areas such that total area burned covers 13 km2, to mimic what happened in Hiroshima. The study projected soot generation for this weapons use scenario in 13 different countries, producing a range of soot generated varying from 0.85 to 5.22 Tg, in Israel and China, respectively. For such an employment on U.S. urban centers it was estimated that 1.2 Tg of elemental carbon would be generated. In all scenarios it was predicted that most of the soot would reside in the middle or upper troposphere where it could potentially self-loft into the stratosphere. The Robock et al. (2007) paper building on Toon et al. (2007), used 5 Tg of BC injected into the upper troposphere, projected a maximum global-average surface shortwave radiation change of −15 W/m2 reaching this peak roughly 6

___________________

2 The standard measure of mass in nuclear war climate studies has been the teragram, or Tg. One teragram equals 1 × 1012 grams, 1 × 109 kilograms, or 1 × 106 metric tonnes (or simply, ton). The abbreviation Mt is reserved throughout this report to indicate explosive yield, as defined in the text (i.e., 1 Mt = 1 × 1015 calories).

3 Lynn Eden’s (2003) book Whole World on Fire includes an accessible summary that discusses the need for improved research on the topic of firestorms that may result from nuclear war.

4 The fuel burden of 1.1 × 107 g/person is approximately 12 U.S. tons/person. This conversion was not included in the narrative as it might be confused with the units of kiloton and megaton used for nuclear weapon yield. The committee decided to leave this value with the original published units of g/person.

months after the nuclear exchange. This had an associated global average surface cooling of −1.25ºC minima with the most rapid and intense cooling occurring over the first 3 years after the nuclear exchange and lasting roughly 10 years. Additionally, due to global cooling there was a roughly 10% global average reduction in precipitation.

Reisner et al. (2018) employed a fire dynamics model to determine the outcome of a nuclear exchange scenario analogous to that of Toon et al. (2007). Using available information about fuel quantities in a U.S. city chosen as a generic suburb, the model resulted in most of the BC generated staying below 12 km and 0.20–0.24 Tg of BC reaching above 12 km. This height was chosen because they found that this was the approximate maximum height of weather systems. For this scenario, they saw statistically insignificant anomalies for near-surface atmospheric temperature, net solar radiation flux, and precipitation rate. This work additionally evaluated the 5-Tg stratospheric soot injection scenario and saw maximum decreases in near-surface atmospheric temperature of −2ºC, net solar radiation flux of −13 W/m2, and precipitation rate of −0.26 mm/day all occurring within the first 5 years after the BC injection.

In addition to work directly on environmental consequences of nuclear war, the National Academies has published consensus reports laying out research agendas that support the science in question, namely The Chemistry of Fires at the Wildland–Urban Interface (NASEM, 2022), Next Generation Earth System Prediction: Strategies for Subseasonal to Seasonal Forecasts (NASEM, 2016a), The Future of Atmospheric Chemistry Research: Remembering Yesterday, Understanding Today, Anticipating Tomorrow (NASEM, 2016b).

1.4 ORGANIZATION OF THIS REPORT

The structure of this report follows the causal pathway of potential impacts, shown in Figure 1-1, first exploring a plausible set of weapons exchange scenarios (Chapter 2) and then addressing how fire dynamics and emissions would result from nuclear detonations (Chapter 3), the fate and transport of these emissions once aerosolized (Chapter 4), the subsequent effects on the climate and physical Earth system (Chapter 5), and the eventual impacts on nature and ecosystems (Chapter 6). The last chapter (Chapter 7) extends these pathways to their potential societal and economic endpoints, focusing on three broad categories of impacts felt by people and society: to ecosystem services, to human health, and to broader societal resilience.

REFERENCES

Aleksandrov, V. V., and G. L. Stenchikov. 1983. “On The Modeling Of The Climatic Consequences of The Nuclear War.” The Proceeding of Applied Mathematics. Moscow, Russia: The Computing Center of the USSR Academy of Sciences.

Arms Control Association. 2024. “Adapting the U.S. Approach to Arms Control and Nonproliferation to a New Era.” https://www.armscontrol.org/2024AnnualMeeting/Pranay-Vaddi-remarks. (accessed August 8, 2024).

Atomic Archive. n.d. “The Atomic Bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki.” (accessed March 31, 2025). https://www.atomicarchive.com/resources/documents/med/med_chp10.html.

Bardeen, C. G., D. E. Kinnison, O. B. Toon, M. J. Mills, F. Vitt, L. Xia, J. Jägermeyr, N. S. Lovenduski, K. J. N. Scherrer, M. Clyne, and A. Robock. 2021. “Extreme Ozone Loss Following Nuclear War Results in Enhanced Surface Ultraviolet Radiation.” Journal of Geophysical Research: Atmosopheres 126(18):e2021JD035079. https://doi.org/10.1029/2021JD035079.

Crutzen, P.J. and J.W. Birks.1982. “The Atmosphere After a Nuclear War: Twilight at Noon.” Ambio 11(2-3):114-125.

DOS (Department of State). 2023. “New START Treaty.” https://www.state.gov/new-start/ (accessed July 26, 2024).

DOS. 2024. “2023 Report to Congress on Implementation of the New START Treaty.” https://www.state.gov/bureau-of-arms-control-deterrence-and-stability/releases/2024/01/2023-report-to-congress-on-implementation-of-the-new-start-treaty.

Eden, L. 2003. Whole World on Fire. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

Harwell, M. A. and T. C. Hutchinson. 1986. “Environmental Consequences of Nuclear War (SCOPE 28), Vol. 2: Ecological and Agricultural Effects.” New York, NY: John Wiley and Sons.

Michelsen, H.A., M.B. Colket, P.E. Bengtsson, A. D’anna, P. Desgroux, B.S. Haynes, J.H. Miller, G.J. Nathan, H. Pitsch, and H. Wang. 2020. “A review of terminology used to describe soot formation and evolution under combustion and pyrolytic conditions.” ACS nano, 14(10): 12470-12490. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsnano.0c06226.

Mills, M. J., O. B. Toon, J. Lee-Taylor, and A. Robock. 2014. “Multidecadal Global Cooling and Unprecedented Ozone Loss Following a Regional Nuclear Conflict.” Earth’s Future 2(4):161-176. https://doi.org/10.1002/2013EF000205.

NASEM (National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine). 2016a. “The Future of Atmospheric Chemistry Research: Remembering Yesterday, Understanding Today, Anticipating Tomorrow.” Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. https://doi.org/10.17226/23573.

NASEM. 2016b. “Next Generation Earth System Prediction: Strategies for Subseasonal to Seasonal Forecasts.” Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. https://doi.org/10.17226/21873.

NASEM. 2022. “The Chemistry of Fires at the Wildland-Urban Interface.” Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. https://doi.org/10.17226/26460.

New York Times. 1949. “Toll at Hiroshima Placed at 210,000 - Mayor of First Atomic Target in Japan Reports Casualties Far Above Earlier Totals.” The New York Times.

NFPA (National Fire Protection Association). 2021. “NFPA 921, Guide for Fire and Explosion Investigations National Fire Protection Association.”

NRC (National Research Council). 1985. “The Effects on the Atmosphere of a Major Nuclear Exchange.” Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. https://doi.org/10.17226/540.

ODNI (Office of the Director of National Intelligence). 2023. “Annual Threat Assessment of the U.S. Intelligence Community.” https://www.dni.gov/files/ODNI/documents/assessments/ATA-2023-Unclassified-Report.pdf.

Ozasa, K., E. J. Grant, and K. Kodama. 2018. “Japanese Legacy Cohorts: The Life Span Study Atomic Bomb Survivor Cohort and Survivors’ Offspring.” Journal of Epidemiology 28(4):162-169. https://doi.org/10.2188/jea.JE20170321.

Pittock, A. B., T. P. Ackerman, P. J. Crutzen, M. C. Maccracken, C. S. Shapiro, and R. P. Turco. 1986. “Environmental Consequences of Nuclear War (SCOPE 28), Vol. 1: Physical and Atmospheric Effects.” New York, NY: John Wiley and Sons.

Redfern, S., J. K. Lundquist, O. B. Toon, D. Muñoz-Esparza, C. G. Bardeen, and B. Kosović. 2021. “Upper Troposphere Smoke Injection from Large Areal Fires.” Journal of Geophysical Research: Atmospheres 126(23):e2020JD034332. https://doi.org/10.1029/2020JD034332.

Reisner, J., G. D’Angelo, E. Koo, W. Even, M. Hecht, E. Hunke, D. Comeau, R. Bos, and J. Cooley. 2018. “Climate Impact of a Regional Nuclear Weapons Exchange: An Improved Assessment Based On Detailed Source Calculations.” Journal of Geophysical Research: Atmospheres 123(5):2752-2772. https://doi.org/10.1002/2017JD027331.

Reuters. 2023. “Putin: Russia Suspends Participation in Last Remaining Nuclear Treaty with U.S.” Reuters. https://www.reuters.com/world/europe/putin-russia-suspends-participation-lastremaining-nuclear-treaty-with-us-2023-02-21/.

Robock, A., and B. Zambri. 2018. Did smoke from city fires in World War II cause global cooling? Journal of Geophysical Research: Atmospheres, 123, 10314-10325. https://doi.org/10.1029/2018JD028922

Robock, A., L. Oman, G. L. Stenchikov, O. B. Toon, C. Bardeen, and R. P. Turco. 2007. “Climatic Consequences of Regional Nuclear Conflicts.” Atmospheric Chemistry and Physics 7(8):2003-2012. https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-7-2003-2007.

Toon, O. B., R. P. Turco, A. Robock, C. Bardeen, L. Oman, and G. L. Stenchikov. 2007. “Atmospheric Effects and Societal Consequences of Regional Scale Nuclear Conflicts and Acts of Individual Nuclear Terrorism.” Atmospheric Chemistry and Physics 7(8):1973-2002. https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-7-1973-2007.

Turco, R. P., O. B. Toon, T. P. Ackerman, J. B. Pollack, and C. Sagan. 1983. “Nuclear Winter: Global Consequences of Multiple Nuclear Explosions.” Science 222(4630):1283-1292. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.222.4630.1283.

Turco, R. P., O. B. Toon, T. P. Ackerman, J. B. Pollack, and C. Sagan. 1990. “Climate and Smoke: an Appraisal of Nuclear Winter.” Science 247(4939):166-176. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.11538069.

Wagman, B. M., K. A. Lundquist, Q. Tang, L. G. Glascoe, and D. C. Bader. 2020. “Examining the Climate Effects of a Regional Nuclear Weapons Exchange Using a Multiscale Atmospheric Modeling Approach.” Journal of Geophysical Research: Atmospheres 125(24):e2020JD033056. https://doi.org/10.1029/2020JD033056.