Potential Environmental Effects of Nuclear War (2025)

Chapter: 5 Physical Earth System Impacts

5

Physical Earth System Impacts

5.1 INTRODUCTION

This report explores the environmental effects and societal and economic consequences that would follow in the weeks-to-decades after a nuclear war, beginning with a description of a plausible set of scenarios for the employment of nuclear weapons (Chapter 2); an exploration of the fire dynamics and emissions resulting from the nuclear detonations (Chapter 3); and a discussion of the fate and transport of these emissions once aerosolized (Chapter 4). The current chapter examines the effects on the climate and physical Earth system and sets up an exploration in later chapters of the impacts on ecological and societal and economic systems (Chapters 6 and 7).

This chapter largely focuses on the consequences of the nuclear weapon exchanges with larger numbers of weapons that may result in decreased solar radiation globally through the atmosphere. As discussed in Chapter 2, work is needed across the range of possible weapon employment scenarios to better understand conditions that would lead to such a decrease. This chapter steps through impact on Earth systems, beginning with changes in solar radiation and the follow-on impacts that those changes have on stratospheric ozone, temperature, and the hydrological cycle. The chapter then shifts to considering how these changes impact ocean systems, and the cryosphere.

BOX 5-1

Key Terms

Aerosol Single-Scattering Albedo (SSA): Ratio of scattering efficiency to total extinction efficiency of a particle. A lower SSA means more light-absorbing material (e.g., black carbon), whereas a higher SSA means a more light-scattering particle.

Albedo: Reflectivity of Earth’s surface, measured as a fraction. An albedo of zero means all incident sunlight is absorbed, and an albedo of 1 means all incident sunlight is reflected.

Albedo Feedback: Positive feedback in which a temperature-induced change in the area of highly reflective snow cover, glaciers, land ice, and/or sea ice alters Earth’s albedo and hence amplifies the change in Earth’s surface temperature.

Ash: Solid particulate remnants resulting from fire, either temporarily persisting in the atmosphere or immediatel deposited on the landscape.

Backscattering Fraction: Fraction of sunlight scattered backward (in the direction of incidence) when sunlight scatters off an aerosol or cloud droplet. Larger backscattering fractions reduce the amount of sunlight transmitted to Earth’s surface.

Cloud Radiative Effect: Net effect of two competing processes in which clouds can both (1) trap the outgoing longwave terrestrial radiative flux at the top of the atmosphere to warm Earth and (2) reflect incoming shortwave solar radiative flux back to space to cool Earth. This effect depends on cloud height, type, and optical properties.

Earth System Model (ESM): Model composed of a set of equations describing atmospheric and oceanic circulation and thermodynamics, incorporating the biological and chemical processes that feedback on to the physics of climate, all solved for a number of locations in space that form a three-dimensional grid over the surface of Earth and underneath the surface of the oceans.

General Circulation Model: Numerical model for computing the evolution of the atmosphere and/or ocean using the fundamental equations that govern geophysical fluid dynamics.

Hysteresis: Phenomenon in which the physical response of a system to an external influence depends on both the present magnitude of the influence and the previous history of the system. External influences are often associated with irreversible thermodynamic changes or internal friction, and hysteretic responses are often characterized as lagging. Systems with hysteresis that are driven to evolve from one state to another need not revert to their original state when the driver is removed.

Lapse-Rate Feedback: Negative feedback in which a temperature-induced change in Earth’s surface temperature induces a thermodynamically driven change in the rate at which atmospheric temperature decreases with height and thereby alters the thermal component of the greenhouse effect so as to dampen further changes in Earth’s surface temperature.

Longwave (or Infrared or Terrestrial) Radiation: Electromagnetic radiation emitted by Earth’s surface, atmosphere, and clouds. Longwave radiation lies in the infrared part of the spectrum, with wavelengths typically ranging from 4 to 30 microns.

Optical Depth: Unitless measure of absorption and scattering of sunlight. The amount of sunlight transmitted downward decreases exponentially with the total optical depth of the overlying atmosphere.

Photosynthetically Active Radiation (PAR): Total solar radiation at wavelengths between 400 (violet) to 700 nm (red) that is available for photon capture by chlorophyll and other light harvesting pigments in plants, also referred to as photosynthetically available radiation.

Shortwave (or Solar) Radiation: Electromagnetic radiation emitted by the sun, which lies in the visible, near-ultraviolet, and near-infrared range of the spectrum. Shortwave radiation typically occurs between wavelengths of 0.1 to 5.0 microns.

Spectral Irradiance (also Insolation): Power per unit area (surface power density) received from the sun in the form of electromagnetic radiation.

Surface Mixed Layer: Uppermost layer of the ocean that has been mixed and hence homogenized by active turbulence.

Thermocline: Layer in a body of water (e.g., the interior of the ocean) with a high gradient of temperature with depth.

Thermohaline Circulation: Large-scale ocean circulation driven by global density gradients caused by surface heat and freshwater fluxes that affect the density of seawater.

Ventilation: Transport of surface waters into the interior of the ocean.

Water Vapor Feedback: Positive feedback in which a temperature-induced change in sea-surface temperatures alters the rate of evaporation of water vapor from the ocean surface, thereby altering the amount of water vapor in Earth’s atmosphere and its attendant (and dominant) greenhouse effect, and hence further amplifies the change in sea-surface temperature.

5.1.1 Description of Drivers and Physical Earth System Thresholds

Connecting the estimates of smoke from Chapters 2 through 4 to projections of the response of the climate system is challenging and requires computing the response under a very wide range of

scenarios for the severity and scale of the nuclear exchange. The current issue of anthropogenic climate change offers an analogous challenge, since projections of the climate system response are tied to a similarly broad range of scenarios of greenhouse gas emissions and other human actions. In the climate change context, the climate system response is judged to be approximately linear to the magnitude of the anthropogenic forcing. The most important example is the change in the global and annual-mean surface air temperature (GSAT) relative to its preindustrial value and the relationship of that change to the enhanced greenhouse effect caused by anthropogenic carbon dioxide. The change in GSAT since 1850 is nearly linearly related to the total cumulative anthropogenic emissions of carbon dioxide over the same time period (IPCC, 2023). This implies that the response of GSAT under a wide array of scenarios for additional emissions in the 21st century could be accurately approximated by a normalized response of GSAT to baseline cumulative emissions times the ratio of the actual to the baseline cumulative emissions.

There are multiple reasons why it is not clear that this normalization procedure will work for estimating the climatic response to a broad spectrum of nuclear exchanges. The first reason is that the insolation reaching Earth’s surface depends nonlinearly on the optical depth of the atmosphere, a measure of how many times a solar photon will interact with smoke particles in the air before reaching the ground. Once the mass of smoke is sufficient to drive the optical depths to values well above 1, the effects of the smoke on surface insolation begin to saturate (or reach an asymptote). Hence, the effects of smoke on surface insolation and GSAT cannot scale linearly with mass of smoke produced in this limit.

The second reason is that some of the nuclear exchange scenarios produce perturbations large enough that the linearity of the response of the climate system is no longer guaranteed by recent historical experience. In the following discussion on sunlight effects on Earth, insolation is the amount of solar radiation on Earth and albedo is the fraction of sunlight that is reflected. The most evident nonlinearity is the abrupt increase in surface albedo and resulting reduction in insolation absorbed by the surface once precipitation changes phase at the freezing point of water from rain to snow. Some recent literature on EENW has suggested that sufficiently large injections would effectively trigger a centennial-length ice age due to this nonlinear physics (Harrison et al., 2022). This chapter considers further departures from linear climate system responses to various forms of abrupt climate change associated with expansion of the cryosphere and long-lived alterations to ocean circulation.

5.1.2 Timescales of Physical Earth System Response

The response of the climate system to a nuclear exchange is complex in part because key processes in the climate system respond to perturbations on a range of timescales ranging from weeks to over a decade, that is, periods much longer than the triggering nuclear exchange. This chapter is sequenced roughly in order of fast to slow processes, starting with the effects of smoke on solar insolation (effectively instantaneous) to the decadal-scale responses of the upper ocean and cryosphere. The presence of such long response times in core components of the climate system implies that the effects of a nuclear exchange on the physical, chemical, and biogeochemical states of the climate system could, scenario dependent, persist decades after the fires following a nuclear exchange have been quenched and the smoke aerosols have disappeared from Earth’s atmosphere.

5.1.3 Key Processes and Interactions

The relevant components of the physical climate system implicated in the response to a nuclear exchange are the atmosphere, ocean, land surface, and cryosphere, which comprises glaciers, land ice sheets, and sea ice. The evolution of the climate system is governed by the physical states and processes of these components combined with the chemistry of Earth’s atmosphere and the biogeochemical processes intrinsic to terrestrial and oceanic ecosystems. Interactions among the climate system components frequently involve atmospheric exchanges as the transfer mechanisms since the atmosphere is in direct contact with all other components. Long-range teleconnections between ocean basins are supported by changes in atmospheric circulation on timescales of weeks to years.

The atmosphere is strongly coupled to the ocean surface through the exchange of energy, mass, and momentum. This coupling induces several important internal modes of variability including the El Nino–Southern Oscillation in the Pacific Ocean Basin, the Pacific Decadal Oscillation, the Atlantic Multidecadal Oscillation, and the Inter-decadal Pacific Oscillation. Internal modes of atmospheric variability include the Pacific/North American pattern, the Annual Mode and Southern Annular Mode, and the North Atlantic Oscillation. The combination of all these modes of variability explains less than 10% of the temporal variance in rainfall over the continental United States (CONUS) (Risser et al., 2021). Despite the widespread and well-publicized effects of the record high temperatures worldwide in 2023, the effects of these modes of variability on CONUS surface temperature and rainfall are dwarfed by several published estimates of the effects of a nuclear exchange on the same key quantities.

5.1.4 Chapter Organization

The chapter is organized following the causal sequence of interactions in the climate system in response to the smoke and other pollutants resulting from a nuclear exchange. The clouds of smoke and attendant radiatively active gases will immediately reduce the solar insolation at Earth’s surface beneath those clouds (Section 5.2). In addition to these physical effects, injection of smoke and other chemical compounds into the stratosphere can affect the ozone layer, with potentially significant implications for the amount of ionizing ultraviolet (UV) radiation reaching Earth’s surface (Section 5.3). In response, the land surface will cool rapidly, and the ocean much more slowly, until the surface layers come back into thermal equilibrium with the greatly reduced insolation (Section 5.4). The resulting alteration of the infrared cooling and solar heating of Earth’s atmosphere, together with the reduction in surface evaporation as the atmosphere cools with the surface, will alter the hydrological cycle by perturbing the radiative-convective equilibrium (RCE) that sets global rainfall rates (Section 5.5). These alterations will manifest on the characteristic timescales of RCE of between 10 days and 2 weeks. Alteration in the hydrological cycle will affect both the tropical and subtropical atmospheric circulation systems that exert wind drag on the ocean surface, and it will also affect the salinity of the ocean surface by perturbing freshwater inputs. The combination of altered wind stress, thermohaline convection, and mixing in the oceanic mixed layer could appreciably alter the ocean physical state and circulation (Section 5.6). The fundamental physics of the climate system implies that the atmosphere and ocean both transport heat from the equatorial region to the poles. The same physics dictates that the alteration of solar insolation absorbed by the climate system by the widespread introduction of smoke aerosols will alter these transports, with potentially significant implications for the subsequent state and evolution of the cryosphere (Section 5.7). Wet and dry deposition of carbonaceous aerosols onto the snow and ice in the cryosphere could also enhance the tendency of these frozen surfaces to heat and possibly melt (also Section 5.7).

For each of these processes and systems, the state of present knowledge is followed by key sources of uncertainty, such as lack of process understanding or modeling ability, and by the data and understanding needed to address these uncertainties.

5.2 SOLAR RADIATION

5.2.1 State of Knowledge

The physics of radiative transfer, which includes the propagation of sunlight from the top of Earth’s atmosphere to the surface, is known to first principles. The equations used in all Earth system models (ESMs) used to simulate EENW are highly accurate approximations to the fundamental Maxwell equations for classical optics and electromagnetism. Therefore, the accuracy and physical fidelity of the solutions to these equations is entirely governed by the accuracy and fidelity of the inputs to these solutions. Because sunlight passes through the atmosphere in less than a millisecond, the insolation at Earth’s surface varies instantaneously with these input conditions.

The inputs comprise of two boundary conditions and three atmospheric optical properties. The boundary conditions are the spectral insolation at the top of the atmosphere, and the spectral reflectance properties of Earth’s surface. The atmospheric optical properties, which vary in space and time, are the extinction optical depth, a measure of visibility; the backscattering fraction, which is the percentage of sunlight reflected upward by atmospheric constituents; and the single-scattering albedo (SSA), which is the fraction of sunlight scattered rather than absorbed by atmospheric constituents. These optical properties are known to a high degree of precision for the gaseous constituents of Earth’s atmosphere, for example, water vapor and ozone, and are highly uncertain for the condensed matter in Earth’s atmosphere, namely clouds and aerosols. Since the optical depths of aerosols in many EENW scenarios are 1 to several orders of magnitude larger than the optical depths of the typical atmospheric gaseous constituents, the uncertainty in the amount of sunlight reaching Earth’s surface is completely dominated by the uncertainty in the aerosol optical properties. Even knowing the column-integrated mass of atmospheric aerosol per unit area of Earth’s surface is insufficient. The reason is aerosol optical properties

depend strongly on the size distributions of the aerosol particles, the geometrical shapes of the aerosol particles (e.g., spheres versus coagulant chains), their heterogeneous chemical composition, and the internal arrangements of constituents in each aerosol particle. These microphysical properties are, in turn, determined in detail by the formation and evolution of the aerosols and their interactions with atmospheric gases, water vapor, ambient aerosols, clouds, and precipitation, that is, the processes considered in detail in Chapter 4. While ESMs tend to have highly simplified treatments of these processes, the fact that more exact models of aerosol formation, evolution, and interaction require essentially unattainable amounts of empirical data greatly complicates the task of making robust generalizable and quantitative connections between aerosol precursors and resulting effects on insolation. However, the signs of these effects (e.g., higher aerosol optical depth always implies lower surface insolation) are dictated by the fundamental physics of radiative transfer and hence can be confidently predicted.

Aerosols can both scatter and absorb sunlight. While both processes reduce the insolation at Earth’s surface, absorption also heats the atmosphere, making the airmass containing the aerosols more positively buoyant, and can therefore alter atmospheric dynamics (e.g., the self-lofting of stratospheric aerosols discussed in Section 4.3). The strongest determinant of which process dominates is the SSA optical property discussed above. The amount and effects of the absorption are strongly affected by the vertical profile of absorbing aerosols in relation to the other optically thick constituents of Earth’s atmosphere, specifically clouds and water vapor.

At a global scale, aerosol mass is projected to peak in the stratosphere in the first year following a nuclear exchange. Consequently, downward surface shortwave radiation also shows the largest decrease during the first year, as aerosols within the stratosphere disperses widely within the hemisphere of injection (Robock et al., 2007; Turco et al., 1983). In subsequent years, stratospheric aerosol mixes more widely (across both hemispheres), and its mass decreases, often linearly or following an exponential decay function, due to aerosol loss processes and stratosphere-troposphere mixing at middle and high latitudes. In a widely studied model setup in which 5 Tg of black carbon (BC) aerosol is injected into the upper troposphere at mid-latitudes in the Northern Hemisphere, the e-folding lifetime of the stratospheric aerosol varies widely across studies, ranging from about 2 to 3 years in the Energy Exascale Earth System Model version 1 (E3SM-v1) (Wagman et al., 2020) to about 8 years in Whole Atmosphere Community Climate Model version 4 (WACCM-v4) (Mills et al., 2014; Reisner et al., 2019). These lifetimes, summarized by Wagman et al. (2020), dictate the timescale of the perturbation to global downward surface shortwave radiation.

To explore the relationship between aerosol load and surface radiation, recent atmospheric model estimates of global stratospheric aerosol mass and downward surface shortwave radiation during the second year following atmospheric injection (i.e., from 13 to 24 months following the initial simulated nuclear exchange) were compiled. This period was selected so that aerosol mass was more uniformly distributed across the stratosphere in the Northern and Southern hemispheres. For studies that report the anomaly in net downward shortwave radiation at Earth’s surface, these estimates were converted to downward surface shortwave radiation using the radiation budget developed by Trenberth et al. (2009). This analysis revealed that for injections up to about 5 Tg BC, there is a mostly linear relationship between aerosol mass and the global surface shortwave radiation response consistent within and across models. The slope of the relationship is about −2.7 ± 0.2 W/m2 per Tg of BC (Figure 5-2). For larger injections, from the work of Toon et al. (2019), there is evidence for a nonlinear (saturating) impact of increasing BC aerosol load on surface radiation and a power law equation with an intercept term that best explains the model simulations (Figure 5-3).

Strong hemispheric asymmetries exist in the initial surface radiation response for the northern mid-latitude aerosol injection study case. Within several months, strong winds in the upper troposphere and lower stratosphere mix aerosols widely in the east-west direction, creating a more uniform zonal distribution of aerosol mass and surface radiation attenuation (Pausata et al., 2016; Wagman et al., 2020). After 6-12 months, the maximum aerosol loading migrates northward, likely due to atmospheric transport within the stratosphere (Reisner et al., 2018; Stenke et al., 2013). The build-up of aerosol in the Southern

Hemisphere (SH) stratosphere shows a delayed response relative to the Northern Hemisphere (NH). Although some aerosol accumulation is visible in low latitudes of the SH after 6 months (Reisner et al., 2018; Stenke et al., 2013), concentrations typically do not reach a maximum in southern midle and high latitudes until about 2 years after injection (Mills et al., 2014; Reisner et al., 2018; Robock et al., 2007; Stenke et al., 2013; Wagman et al., 2020). Thus, the surface radiation perturbation in the first year is confined mostly to the NH, with a growing influence in the SH in year 2. After 2-3 years, aerosol mass and surface radiation impacts are nearly symmetric across the NH and SH. During this latter recovery phase, a strong meridional pattern exists in aerosol optical depth and surface radiation, with stratospheric aerosol concentrations and negative surface radiation anomalies lowest near the Equator and highest in a latitude band between 50° and 70° (Mills et al., 2014; Reisner et al., 2018; Robock et al., 2007; Stenke et al., 2013; Wagman et al., 2020).

Several studies have explored the radiative effects of BC and particulate organic matter (POM) aerosol mixtures (Pausata et al., 2016; Wagman et al., 2020). Pausata et al. (2016) show that in the first year following the nuclear exchange, adding 15 Tg of POM to a 5-Tg BC simulation decreases shortwave radiation at the surface by about an additional 20%, and adding 45 Tg of POM decreases surface radiation by an additional 50%. Wagman et al. (2020) find that a combination of 5 Tg BC and 15 Tg POM aerosol mass reduces surface shortwave radiation by about an additional 75% in the first year after injection relative to a BC-only simulation. Besides radiative effects, POM may influence rates of aerosol coagulation and settling (Pausata et al., 2016) and atmospheric heating and self-lofting (Yu et al., 2021). Thus, the composition of a POM plus BC aerosol mixture also likely influences the residence time of aerosol masses resulting from nuclear detonations within the stratosphere through at least two separate pathways.

Nearly all modeling studies exploring the environmental effects of nuclear war focus on the net downward (longwave and shortwave) or net surface shortwave radiation anomalies, since radiative fluxes in these ranges of the electromagnetic spectrum are critical for regulating Earth’s surface energy budget and near-surface temperature and climate. In contrast, there has not been a systematic exploration of the impacts of a nuclear exchange on the portion of the electromagnetic spectrum that includes photosynthetically active radiation (PAR) in the 400- and 700-nm wavelength band. Chlorophyll a and b and carotenoid pigments only absorb PAR photons, and thus, radiation in this part of the spectrum is a key driver of the light reactions in photosynthesis. Although PAR can be explicitly computed from the broader surface shortwave radiation response within ESMs in order to estimate nuclear war impacts on land and ocean net primary production (Scherrer et al., 2020; Xia et al., 2022), relatively little is known about the specific response of PAR to forcing from a nuclear exchange. If much of the fire-emitted aerosol that enters the stratosphere is BC, which is widely absorbing across much of the electromagnetic spectrum, then the PAR response may be similar in magnitude to the predicted (and extensively documented) decrease in surface shortwave radiation. However, mixtures of absorbing and scattering aerosols in the contemporary atmosphere, including sulfates and organic carbon (OC), are known to have disproportionately large effects on PAR relative to shortwave radiation (Lozano et al., 2021). Scattering

aerosol, such as volcano-derived sulfate, also significantly increases the fraction of PAR that reaches the surface as diffuse light (Farquhar and Roderick, 2003). Since many studies exploring nuclear war effects on the biosphere have focused on scenarios either primarily or entirely focusing on BC aerosol, it is likely that impacts on both the magnitude and composition (diffuse/direct ratio) of PAR have been underestimated.

5.2.2 Key Uncertainties and Data Gaps

The key uncertainties are in the inputs to the radiative transfer equations:

- The column integrated mass of aerosol per unit area of Earth’s surface, as a function of space and time;

- The extinction cross-section per unit mass of the aerosol, which depends on aerosol sizes, composition, and mixing state; and

- The single scattering albedo (SSA) of the aerosols.

The product of the column integrated mass and the extinction cross-section per unit mass gives the extinction optical depth. The backscattering fraction is typically of lesser importance.

Given the appreciable uncertainty in simulations of historical anthropogenic sulfate (a comparatively much simpler aerosol species than smoke) despite three decades of research on it, it seems unrealistic to expect models of smoke from a nuclear exchange to exhibit faster gains in physical realism and process fidelity.

5.3 STRATOSPHERIC OZONE

5.3.1 State of Knowledge

Following elucidation of the possibility of nuclear winter, studies began to examine possible impacts of nuclear war on stratospheric ozone depletion. Early studies focused on the role of reactive nitrogen (NOx) produced thermally by detonation of the large numbers of nuclear weapons, which would be injected into the stratosphere and could, in principle, catalytically destroy stratospheric ozone (e.g., Stephens and Birks, 1985). A global nuclear exchange of about 6500 Mt was estimated to yield an average global total column ozone loss of around 17% within a year, decreasing to about 8.5% by the third year (NRC, 1985) using a one-dimensional model of the stratosphere. In such models, vertical transport is purely diffusive, with a slow rate of transport of NO. Later studies used more realistic three-dimensional frameworks (e.g., Kao et al., 1990) to study global nuclear war, and obtained greater transport of NO into the ozone layer. More important, they also included heating due to the absorption of radiation by smoke and the impacts of higher temperatures on ozone chemistry, as well as through changes in the stratospheric circulation. The Kao et et al. (1990) study obtained stratospheric warming of more than 50°C over large regions. While this early study was limited by computing resources of the day, they obtained resulting declines of the ozone layer—as much as 15% of the overhead column in just 20 days. Such ozone losses would have major consequences for UV radiation at the ground. A scenario forcing 150 Tg BC into the atmosphere could result in a 10-20% increased pulse of surface UV radiation approximately 8 years post-conflict and persisting for approximately 4 years during ozone recovery (Bardeen et al., 2021). This range of UV radiation has the potential to alter algal biochemical composition and productivity, subsequently impacting the persistence and abundance of species at higher trophic levels (Harrison and Smith, 2009).

Later studies have focused largely on the ozone depletion that would be expected from regional nuclear wars with smaller inputs of NO and smoke, including for the first time the lofting of material due to absorption of sunlight by the BC in the particles. Mills et al. (2008) considered inputs of 1 and 5 Tg of smoke, which they assumed to be composed of pure BC. Note that the assumption that the particles are

pure BC greatly influences the results and is discussed further below in the context of recent wildfire studies. Mills et al. (2008) suggest that about 20% of the smoke would be lost before reaching the stratosphere. They suggested that the heating of pure BC particles once in the stratosphere would transport material as high as the upper stratosphere, where removal rates are very slow, leading to a half-life of the BC perturbation on the order of 3–6 years for the 1- and 5-Tg cases, respectively. Local heating near the stratopause was on the order of 80°C. Calculated ozone losses in the 5 Tg case were dominated by the heating and its effects on photochemistry: about 10% of the column in the tropics during the first 3–4 years, increasing to 40% at mid-latitudes. Calculated ozone losses declined but remained significant for about 10 years of simulation. They noted that both the tropical and mid-latitude ozone losses would have major biological impacts through increases in UV radiation.

Similar calculations were carried out by Stenke et al. (2013) using a different global chemistry–climate model. A larger fraction of the initial smoke was lost in these calculations (up to about a third), but the impacts of the remaining material that reached the stratosphere were found to be largely similar to those of Mills et al. (2008). Residence times of the BC in the stratosphere ranged from about 3 to 5 years for 1–5 Tg of input. Ozone losses were broadly similar to the results of Mills et al. (2008) after accounting for the difference in smoke inputs.

A later study by Mills et al. (2014) employed a more comprehensive ESM, with components to represent sea ice, land surface, and ocean processes in a more realistic fashion. Ozone depletion results were largely unchanged from Mills et al. (2008). In this later study, a more detailed look at UV impacts at Earth’s surface was undertaken, accounting for scattering of the BC particles along with absorption and the increased transmission due to ozone losses (and the latter was found to be the dominant effect within a few years or less after the war).

Finally, a later study by Bardeen et al. (2021) further refined the approach to ozone photochemistry by including the impact of the smoke on photolysis rates. For a global nuclear war of 150 Tg of smoke input, they calculated global ozone losses growing to as much as 75%, with 65% in the tropics over a timescale on the order of 15 years total. These decreases followed a few years of small increases in global ozone losses (about 5%) due to NOx chemistry and photolysis rate changes. In the regional 5 Tg case, Bardeen et al. (2021) suggested a global total column ozone loss of 25%, with a half-life on the order of 5 years.

The 2020 Australian wildfires were a major event that put substantial amounts of smoke into the stratosphere and provides an important benchmark against which nuclear war impact studies can be compared. Satellite observations suggest that about 1 Tg of smoke was injected, similar to that in the low injection cases for regional war studies noted above (see Box 4.2). Isolated bubbles of smoke were indeed found to rise as high as 35 km (Kablick et al., 2020; Khaykin et al., 2020). Lofting was also evident in satellite data of particle extinction on the broader scale (Yu et al., 2021), but the bulk of the plume did not rise above about 22 km, and peak warming produced by the smoke was less than 4°C. Yu et al. (2021) showed that this implied that the wildfire smoke particles must have been composed of about 2.5% BC, with the rest largely organics. Whether the BC percentage and associated lofting in nuclear war-generated particles resemble these wildfire particles is critical for calculations of their altitude reached, lifetime in the stratosphere, radiative heating, and related ozone losses. Further studies are needed to better estimate the black carbon production and the high-temperature/low-oxygen conditions under which urban fires that could follow nuclear blasts occur so it is not clear how much wildfire smoke represents a good analog. It is, however, noteworthy that studies of the Australian fires demonstrate unexpected impacts of the smoke on atmospheric composition (see Bernath et al., 2022, and references therein) and provide strong evidence for heterogeneous chemistry on organic aerosols in the stratosphere that has not been included in nuclear war studies to date. Solomon et al. (2023) suggest that the 1 Tg of smoke injected by the Australian fire in 2020 led to about a 3–5% ozone depletion over southern mid-latitudes. Linear scaling suggests that 10–25% mid-latitude ozone loss for a 5-Tg injection from nuclear war is plausible, while larger ozone losses would be expected if the particles have a higher proportion of BC and hence a longer residence time in the stratosphere.

Stratospheric ozone losses following nuclear war events have long been known to depend on the amount of material reaching the stratosphere and its surface area, chemistry, and composition (particularly their absorbing properties, which affect lofting of the particles and their duration in the stratosphere). If the stratospheric particle loading following nuclear events and BC content were lower, the resulting ozone depletion would be less; on the other hand, observations following the 2020 Australian fires clearly demonstrated unexpected chemistry and ozone destruction due to smoke. Recent modeling suggests that the organic species in the 2020 wildfire particles enhanced midlatitude SH ozone loss, due to effective surface chemistry (Solomon et al., 2023), and similar reactions can be expected on particles from fires due to nuclear detonations. Further work would better quantify the composition and amount of material reaching the stratosphere from nuclear war events and the resulting net ozone changes, including all factors (potentially less BC and lofting, but inclusion of organic particle chemistry).

5.3.2 Key Uncertainties and Data Gaps

Although work has been done to model various amounts of stratospheric smoke injections and drawing analogs to historical wildfire events, more work is needed to improve understanding of the impacts of different nuclear weapons exchange scenarios on stratospheric ozone. Uncertainties still remain around important aspects that determine the fate of ozone in these different scenarios, including how much material is injected into the stratosphere, how high the material reaches, the chemical composition and mixing ratio of the materials, and what happens to the material as time evolves. More work is needed to learn about the amount of BC and OC resulting from initial blasts of various scenarios, and any pyroCb that may develop later in a massive fire. Improved understanding of these characteristics will help elucidate uncertainties around how much lofting of particles occurs from the resulting heating, and the impacts on ozone loss. How heating of the tropopause by smoke may impact stratospheric water vapor and potentially surface climate is also uncertain. Importantly, the amount of OC in the particles still remains unclear, as well as the chemistry that occurs in the OC particles and any soot particles. Uncertainties in the chemistry of smoke particles containing OC and BC from nuclear events will require laboratory studies, similar to those undertaken when polar stratospheric cloud chemistry was elucidated following the discovery of the ozone hole.

5.4 TEMPERATURE

5.4.1 State of Knowledge

The temperature of Earth’s surface is set by basic principles of thermodynamics (specifically, the first law of thermodynamics) together with the heat capacities and net energy inputs into the terrestrial and oceanic surface layers adjacent to the atmosphere. The surface layers exchange energy with the layers below through thermal diffusion and, in the ocean, through transmission of sunlight. The surface exchanges energy with the atmosphere through the net (downward minus reflected upward) solar radiation, net (downward minus upward) infrared radiation, latent heat flux associated with the evaporation or condensation of water vapor, and sensible heat flux due to conduction of heat from the surface to the atmosphere. Globally, the solar radiation adds energy to the surface layer while the infrared radiation and latent and sensible heat fluxes remove energy from the surface layer.

The first law dictates that the temperature of the surface layer will respond to an imbalance between the exchanges of energy with the atmosphere and the layers below the surface. If the surface layer gains energy through such an imbalance, it will heat, thereby increasing the energy lost through all fluxes, including net infrared radiation and surface sensible and latent heat fluxes, until balance is restored at a higher surface temperature. Likewise, if the surface layer loses energy, it will cool to reduce the energy lost through net infrared radiation, until balance is restored at a lower surface temperature. This dynamic is manifest in the diurnal and annual cycles in surface temperature in response to diurnal and

annual cycles in surface insolation. The physics is very well understood and can be modeled accurately given the solar (shortwave), infrared (longwave), and surface heat fluxes, which include both the sensible and latent heat fluxes1 exchanged with the atmosphere together with the thermal heat capacity and thermal diffusion properties of the surface layer. The fluxes exchanged with the atmosphere can in turn be accurately computed given the downwelling solar shortwave and infrared longwave fluxes in the atmospheric boundary layer together with surface properties that govern solar reflectivity, infrared emissivity, evaporative capacity, and thermal conductivity.

This physics dictates that the surface will cool in a predictable manner subject to an abrupt and enduring reduction in solar insolation at Earth’s surface due to smoke aerosols resulting from a nuclear exchange. This cooling will likely be amplified by two relatively well understood climate feedbacks. The first, the albedo feedback, will be triggered where the surface is cooled enough to increase the areal extent and/or duration of snow (over land) and sea-ice cover (over ocean). Snow and sea ice are much more reflective (higher surface albedo) than the underlying darker (lower surface albedo) land and ocean surfaces, thereby further reducing the solar insolation inputs into the surface layer and cooling it further. The second, the combined water vapor and lapse-rate feedback, results from the cooling of the atmosphere in response to surface cooling combined with a reduction in its water vapor content governed by the basic thermodynamics relating saturation vapor pressure to temperature, described by the Clausius-Clapeyron relationship. The combination of these two responses to surface cooling will reduce the downwelling infrared radiation from the atmosphere to the surface layer, thereby cooling it further. All these processes are included in ESMs and have relatively low uncertainties.

The key distinction between the land and ocean is that the response time of the land surface to changes in insolation is about two orders of magnitude shorter (faster) than the response time of the upper ocean. The reason is that the global mean effective heat capacity of terrestrial soils, which is comparable to 1 m of seawater,2 is an order of magnitude smaller than that of the uppermost ocean mixed layer, which corresponds to nearly 70 m of seawater. As a result, the land surface can respond to abrupt changes in surface insolation on submonthly timescales while the ocean mixed layer responds to identical changes on timescales of roughly a decade. The differences in response times means that the land will cool much more quickly than the ocean under an abrupt reduction in surface insolation, and likewise will warm much more quickly once the insolation is restored to its climatological norms. The differences in the timescales for the terrestrial and oceanic surface layers to major perturbations in surface insolation are theoretically very well understood and empirically copiously observed.

Surface air temperature is projected to begin cooling 1–3 months after a regional northern midlatitude nuclear exchange, with most of the cooling confined to temperate and tropical regions of the NH between 0° and 40°N (Pausata et al., 2016). After 6–9 months, the cooling intensifies and becomes widespread across all NH land. South America, southern Africa, and Australia also begin to experience significant cooling at this time as aerosols entrained across the tropical tropopause are mixed throughout the SH stratosphere (Mills et al., 2014; Reisner et al., 2018; Stenke et al., 2013).

For a nuclear exchange event in the NH3 that injects several teragrams of BC into the upper troposphere, widespread cooling has been projected across both the NH and SH. Global cooling would reach a maximum level about 24 to 48 months after the nuclear exchange. Cooling during this time over land would be two- to fourfold larger than over the ocean. Cooling on land would be stronger in the NH than in the SH, stronger in continental interior regions than near coasts, and particularly strong during

___________________

1 Solar flux refers to the absorption of incoming shortwave radiation by Earth’s surface. Infrared heat flux is the cooling of Earth from emitted infrared radiation. Sensible and latent heat fluxes are the transfer of heat between Earth’s surface and atmosphere by conduction and condensation / evaporation of surface water, respectively.

2 Typical soil layers are 2 m thick. The heat capacity of 1 m of water (per unit area) is 4.184 × 106 J/K. The specific heat capacity and the density of silty gravely sand are 1.279 × 103 J/kg K and 2.182 × 103 kg/m, respectively. Therefore, 2 m of soil would have the heat capacity (per unit area) of approximately (2 m)*(1.279 × 103 J/kg K)*(2.182 × 103 kg/m3) = 5.542 × 106 J/K.

3 Nuclear war in the SH has never been discussed.

winter months in high northern-latitude regions, likely as a consequence of water vapor and snow-ice-albedo feedbacks (Mills et al., 2014; Reisner et al., 2018; Stenke et al., 2013; Toon et al., 2019). For example, in response to a 5-Tg BC aerosol injection in the upper troposphere studied by Mills et al. (2014) using version 1 of the Community Earth System Model (CESM-v1), much of the global surface ocean would cool by 0.5 to 1.0°C for the period 2–6 years following the nuclear exchange. Tropical and SH land would cool more intensely than nearby ocean regions (by 0.5 to 1.5°C), while northern mid- and high-latitude land areas between 30°N and 60°N would experience the largest climate effects, cooling by 1.5 to 5.0 °C during summer and 2.0 to 8.0°C during winter. A similar but considerably stronger spatial pattern of the mean annual temperature response is shown by Toon et al. (2019) for year 2 following a 27-Tg BC injection. A similar but considerably weaker spatial pattern is shown by Reisner et al. (2018) for a simulation, in which about 0.8 Tg of BC initially enters the stratosphere following the nuclear exchange.

The maximum global cooling anomaly has a 2- to 3-year delay behind the maximum global perturbation to surface solar radiation, which would occur in the first year following the nuclear exchange and then decay in subsequent years. The delay is consistent with the thermal inertia and well-known response time of the ocean mixed layer to climate change (Hansen et al., 1985; Held et al., 2010), and as a result, climate models using a slab ocean model (including no ocean dynamics) (Robock et al., 2007; Toon et al., 2007) tend to yield an evolution of near-surface climate in the first few years following a nuclear exchange similar to that of fully coupled ESMs (including full ocean dynamics) (Mills et al., 2014; Pausata et al., 2016; Reisner et al., 2018; Toon et al., 2019).

The discernable impact of a nuclear exchange on Earth’s surface shortwave radiation budget are described to last for about 7 to 10 years, with shorter intervals for smaller injection events and longer intervals for larger events (Reisner et al., 2019; Toon et al., 2019). This period is defined as the time interval over which the ESM simulation with the aerosol perturbation differs visibly from an envelope created from an ensemble of control simulations designed to capture internal climate variability. The perturbation to global surface air temperature would occur over a similar timescale, but with a delay of several years that likely reflects a positive albedo feedback with snow and sea ice in high-latitude regions (Mills et al., 2014; Stenke et al., 2013) and the persistence of negative heat anomalies at the base of the ocean mixed layer (Mills et al., 2014).

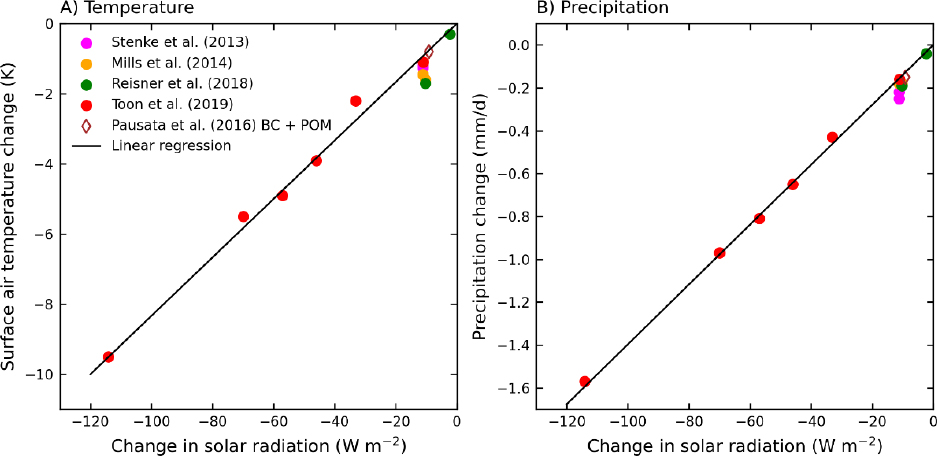

Across different scenarios and models, the maximum level of annual mean cooling is closely related to the magnitude of the downward surface shortwave radiation anomaly in year 2 (Figure 5-4A) This relationship may be useful in extrapolating to scenarios that have yet to be fully explored using ESMs. For the widely studied case in which 5 Tg of BC is injected into the upper troposphere at midlatitudes of the NH, about 3.5 ± 0.6 Tg (70 ± 11%) remains during year 2 (Mills et al., 2014; Reisner et al., 2019; Stenke et al., 2013; Toon et al., 2019; Wagman et al., 2020). This aerosol generates a downward surface shortwave radiation anomaly in year 2 of about −10.2 ± 1.1 W/m2 and a maximum negative annual surface temperature anomaly of −1.4 ± 0.2°C within fully coupled ESMs (Mills et al., 2014; Reisner et al., 2019; Toon et al., 2019). Thus, for smaller aerosol injection events, a maximum cooling rate of −0.27 ± 0.06°C per Tg of BC initially injected into upper troposphere may be a reasonable scale factor. Similarly, as a function of the year-2 downward surface shortwave radiation anomaly, a slope of 0.14 ± 0.03 °C per W/m2 may be useful for extrapolation. Although the relationship between maximum cooling and the year-2 downward surface shortwave radiation appears linear for larger injection events up to 150 Tg BC, as shown in Figure 5-4A, overall, the slope is weaker at 0.083 ± 0.003°C per W/m. This latter relationship is determined primarily from a single set of ESM simulations reported by Toon et al. (2019) using the WACCM-v4 and integrated with ocean, land, and sea-ice model components from the CESM-v1. As a function of stratospheric aerosol mass in year 2, maximum temperature and precipitation responses show some degree of saturation (Figure 5-5), which is expected given that downward surface shortwave radiation also shows a similar nonlinear response (Figure 5-3).

5.4.2 Key Uncertainties and Data Gaps

It is important to note that the uncertainties in solar insolation (Section 5.2) propagate here. Another important source of uncertainty relates to the feedback on the surface energy budget associated with systematic changes in the effects of clouds on solar and infrared fluxes, known collectively as cloud radiative effects (CREs). In the current climate, these radiative effects are an order of magnitude larger than the sum-total anthropogenic radiative forcing, and hence any relatively small perturbations to CRE could have appreciable climatic effects (Collins et al., 1993). The net cloud feedback is the least certain of the feedbacks operating in the climate system since it exhibits the largest range in published estimates. Even the sign of the feedback is still uncertain, although the 1-sigma range is entirely positive.

If the bulk of the smoke produced by a nuclear exchange is injected into and resides in the stratosphere, and hence perturbs the troposphere primarily by altering the downwelling radiative fluxes at the tropopause, then it is reasonable to assume that the cumulative cloud radiative feedbacks will operate as expected and will amplify cooling of Earth’s surface (Forster, 2021). If, however, an appreciable amount of smoke remains in the troposphere, then aerosol–cloud interactions operating on the same fast timescales as cloud formation could become important. These interactions can alter CRE both by altering the bulk optical properties of the clouds and by affecting the lifetimes and areal extents of cloud formations, and these alterations are superimposed on the strong cloud-type dependence of CRE (Chen et al., 2000). The net effect of these aerosol-cloud interactions on the solar and infrared fluxes at Earth’s surface is highly uncertain.

5.5 HYDROLOGIC CYCLE

5.5.1 State of Knowledge

The hydrologic cycle describes the movement of water throughout Earth with multiple processes regulating patterns from global to local scales. The amount of water on the planet is stable, but the partitioning between its three forms (ice, water, and water vapor) varies based on global temperature. Temperature regulates the hydrologic cycle at all scales either directly through phase (ice, water, water vapor) or indirectly through changes to convection and large-scale circulation patterns, suggesting the importance of climate to the water cycle. Moreover, varying impacts of climate across geographic space are due to the physical characteristics of the local environment. Because climatic responses to a nuclear exchange would be complex, in part, due to temporal variation in climate system responses, estimating detailed impacts of a nuclear exchange on the hydrologic cycle is a challenge. Nevertheless, because water touches all parts of social and environmental systems, some estimation of the potential effects of nuclear detonation on the hydrologic cycle is critical.

At the global scale, evaporation, atmospheric transport, and precipitation are all directly regulated by temperature. As evidence, recent increases in air temperature driven by increases in atmospheric greenhouse gas concentrations have resulted in intensification of the hydrologic cycle (Forster, 2021). The mechanism driving these changes is described by the Clausius–Clapeyron relationship that estimates the vapor pressure for substances at different temperatures, which indicates that an increase in air temperature results in an exponential increase in the amount of moisture that the air can hold (Denbigh, 1981). The resulting increase in precipitation has been estimated to be from 3% to 7% per degree Celsius (Allen and Ingram, 2002). The lower bound on the increase follows from the physics of RCE governing global mean rainfall rates, and the upper bound follows from the maximum possible increase in extreme rain rates set by the thermodynamical laws governing surface evaporation. Conversely, short-term decreases in air temperature associated with reduced solar radiation resulting from nuclear detonation would potentially slow the hydrologic cycle by reducing evaporation rates and the amount of moisture in the atmosphere (Figure 5-4B). Short-term increases in tropospheric aerosols may increase the droplet number and decrease the droplet size in liquid-phase clouds, thereby inhibiting the growth of large raindrops and subsequently reducing rainfall (Boucher et al., 2013). Longer-term decreases in

temperature, while reducing the amount of moisture in the atmosphere, would also likely increase the timing and areal extent of over-land snow and sea-ice, further altering the movement of water through the hydrologic cycle, and likely reducing the amount of surface water in liquid or gaseous forms. Resulting thermally driven changes in large-scale atmospheric circulation may also alter the seasonality (timing), spatial distribution, and amount, frequency, and intensity of precipitation.

Although the effects of nuclear detonation on the hydrologic cycle are not well-understood, the impacts of volcanic eruptions (e.g., localized fires, regional atmospheric aerosol injections, decreased air temperatures) may provide insights into potential hydrologic responses to a nuclear exchange. Iles and Hegerl (2014) used a modeling approach, supported by observational data, to demonstrate that large volcanic eruptions (e.g., Mount Pinatubo in 1991) generally result in significant decreases in precipitation over both land and oceans, particularly in wet tropical regions. Several additional studies have also reported decreases in global precipitation following volcanic eruptions in tropical regions, with these reductions particularly pronounced during the summer in monsoon regions (Paik and Min, 2017, 2018; Trenberth and Dai, 2007). These precipitation changes are then proposed to contribute to reductions in river discharge in northern South American, central Africa, and northern Asian rivers, along with increases in discharge in rivers in southern South American and southwestern U.S. rivers.

At the local scale, surface water, and groundwater flows, transpiration, and surface storage in lakes, reservoirs, and wetlands are all important components of the hydrologic cycle. While processes at this scale are dependent on the global hydrologic cycle, smaller-scale processes generally dictate the local impacts of nuclear detonation on contaminant deposition and dispersal, and the subsequent impacts on human activities and welfare, including human health, freshwater availability, and food production. In the shorter-term, reductions in precipitation are expected due to reduced vertical moisture advection (Paik et al., 2022). Ash particles near the detonation site may also absorb moisture and impede the coalescence of water droplets, causing a localized decrease in rainfall.

While alterations in precipitation will have direct impacts on surface waters, groundwater, and soil moisture, the landscape impacts from detonation (blast, fire) and subsequent impacts on surface waters will almost certainly have catastrophic effects on local freshwater systems (Smith et al. 2011). Ash and other contaminants are primarily transported through surface waters by diffusion (lakes and reservoirs), with rates dependent on concentrations, or transport by flowing water, with watershed physical characteristics dictating transport dynamics (Smith et al. 2011). After a blast, the landscape will quickly be inundated with ash from fires. As noted previously, removal of atmospheric materials from nuclear detonation by precipitation will likely then occur for submicron particles over a period of several months, with larger particles removed through sedimentation. Surface ash and deposited particles will become entrained in the hydrologic cycle as precipitation falls on the land surface and surface runoff washes ash and contaminants into surface waters and eventually groundwater. The impacts of detonation and subsequent wildfires will have immediate and detrimental effects on water security, human health, and economies in regions where populations are reliant on surface water for drinking water (Wibbenmeyer 2023), and may result in the need for rapid transition to groundwater reserves.

Groundwater accounts for approximately 100 times more water than what is contained in lakes (Gleeson et al., 2016), supplies approximately 40% of the water used for agriculture (Siebert et al., 2010), and is an important source of local drinking water in all parts of the world. Jasechko et al. (2017) identified the relatively recent contamination of fossil groundwater (>10,000 years old) by tritium, a radioactive isotope of hydrogen with a half-life of 12.33 years, suggesting the likelihood that contamination from a nuclear detonation could have pervasive and long-term impacts on groundwater supplies. While contamination of groundwater is highly likely to result from a nuclear exchange, the location and intensity of the exchange and the groundwater dynamics will dictate the degree of impact to freshwater resources.

The location of detonation will also be important. For example, detonation near the headwaters of the Ganges River in India could potentially transfer ash and contaminants downstream to the mouth of the basin in Bangladesh, impacting water resources and ecosystems in an area supporting 650 million people. Detonation near the mouth of a basin will have more localized effects on surface waters and

groundwaters; however, the discharge to ocean systems may be more intense compared to a detonation farther inland. In either case, water supplies will be contaminated and freshwater ecosystems in the blast region will be severely degraded, potentially destroying fisheries and agricultural production and decreasing ecosystem services.

Water is fundamentally important to all aspects of human existence and supports human health, food and energy production, and economic activities. A nuclear exchange has the potential to alter the global hydrologic cycle to some degree and severely damage local freshwater resources, resulting in significant impacts to ecological and societal and economic systems. Identifying these impacts on freshwater resources then provides the foundation to investigate local impacts on human well-being as well as global disruptions in food production, supply chains, and human migrations.

5.5.2 Key Uncertainties and Data Gaps

While the combination of aerosols resulting from a nuclear exchange and the subsequent albedo feedback and combined water vapor and lapse-rate feedback will reduce surface temperatures, the degree of this reduction is unclear and dependent on the intensity of the exchange. Moreover, the climate system response to smoke from nuclear detonation may not be predictable due to the nonlinear effects of smoke on surface insolation, as noted previously. Consequently, uncertainties in temperature and precipitation changes present a significant challenge in terms of estimating global changes in hydrologic processes. Local hydrologic processes are regulated by the interplay of climate and local physical systems.

Because of climate uncertainty, estimating local watershed responses to a nuclear exchange is also a challenge. This is a critical need, as the watershed response will dictate the transfer of ash, soil, nutrients, and contaminants from the landscape into rivers, lakes, and reservoirs, thus impacting freshwater ecosystems and water quality.

Reasonably accurate estimates of the climate response to nuclear detonation are needed to characterize hydrologic processes after a nuclear exchange. These climate projections can then be used to characterize watershed-level hydrologic processes, which represent the nexus of atmospheric deposition, terrestrial landscape dynamics, and water quality.

In the case of a regional or smaller nuclear exchange, which would not be expected to produce significant stratospheric aerosol loads (and, therefore, a global climate signal) but might produce significant aerosol loading in the lower atmosphere, the potential meteorologic and hydrologic response is deeply uncertain.

5.6 OCEAN PHYSICAL PROPERTIES AND CIRCULATION

5.6.1 State of Knowledge

The movement of water in the ocean, called ocean circulation, has two main drivers: surface wind forcing and buoyancy forcing, both of which are set at the ocean surface and are likely to be influenced by nuclear war. Surface wind transfers momentum to the ocean surface, producing horizontal surface currents that can extend to depths of about 750 m, as well as vertical mixing that can extend hundreds of meters downward in weakly stratified waters. Changes in atmospheric temperature (both its horizontal and vertical structure) associated with a nuclear war can affect the large-scale atmospheric circulation strength and spatial pattern, and hence the surface winds, which are coupled to the ocean circulation. Solar radiation absorption and theexchanges of heat and freshwater between the atmosphere and ocean affect the buoyancy of surface waters and drive the slow movement of waters in the deep ocean (thermohaline circulation; below 1000 m). The temperature and salt content (salinity) of the ocean determine the density of seawater and are the key determinants of buoyancy, with temperature playing a primary role in the density stratification of the water column: the surface is characterized by warm, light water; the deep is characterized by cold, heavy water; and the

surface and deep are separated by the thermocline. Nuclear war has the potential to alter the thermohaline determinants of buoyancy by cooling the ocean surface and altering the patterns of precipitation.

The responses of physical ocean properties and ocean circulation to potential nuclear exchange have been probed in a small number of studies using coupled ocean-atmosphere climate models (also known as general circulation models). These models provide a numerical solution to the governing equations of motion on large spatial scales (100–500 km) across the globe and include the representation of processes occurring on smaller spatial scales via mathematical parameterizations that can differ from one model (version) to another.

The first study to simulate the coupled atmosphere–ocean response to nuclear war (Robock et al., 2007) reported changes in the atmospheric state and described implications for the ocean. Following the injection of 50 and 150 Tg of smoke using the NASA Goddard Institute for Space Studies ModelE (Schmidt et al., 2006) at 4o × 5o spatial resolution, they find reductions in both surface air temperature and precipitation over the ocean that scale with the magnitude of the smoke injection (Robock et al., 2007). Mills et al. (2014) used the National Center for Atmospheric Research CESM-v1 in its WACCM configuration, an atmospheric chemistry–climate model (~2o spatial resolution) coupled to interactive dynamical ocean (~1o), sea ice (~1o), and land (~2o) components, to simulate Earth system response to a limited nuclear exchange between India and Pakistan that produces 5 Tg of BC. In their model experiment, the upper 100 m of the ocean experiences anomalous cooling that peaks at −0.6oC and persists for at least a decade, with the deep ocean continuing to cool for at least 25 years after the nuclear exchange (Mills et al., 2014).

Nuclear war also has the potential to perturb internal modes of climate variability, and in doing so, influence the ocean state and circulation (Coupe et al., 2021). Using a similar configuration of CESMv1 (WACCM) as in Mills et al. (2014), Coupe et al. (2021) simulate the Earth system response to six nuclear exchange scenarios with injections ranging from 5 to 150 Tg of soot. In all but the smallest injection in this study, the nuclear war produces a multiyear El Niño event, dubbed a “Nuclear Niño” by the study’s authors. In the smallest injection case (5 Tg), the nuclear war produces anomalous westerly winds over the Equatorial Pacific that persist for 2 years. These El Niño conditions drive reduced upwelling of cold water in the Eastern Equatorial Pacific, producing warm surface ocean temperature anomalies (Coupe et al., 2021).

A hysteretic response of the ocean to the global cooling following nuclear exchange was reported by Harrison et al. (2022), who analyzed the same CESM-v1 (WACCM) simulations described by Coupe et al. (2021). In the Harrison et al. (2022) study, nuclear war-induced cooling drives surface ocean cooling, a stronger thermohaline circulation in the Atlantic, and intensified ocean vertical mixing that is expanded, deeper, and longer lasting. Though they focus their study on the high-end soot injection case (150 Tg), they note that hysteresis in surface and subsurface temperature occurs in temperature across the full range of the six simulations (5 – 150 Tg soot), wherein the ocean temperature never returns to its initial unperturbed state. Instead, the ocean evolves toward a new equilibrium, characterized by a shallower thermocline and ventilated deepwater masses. In the most extreme simulation (150 Tg soot), their calculations reveal that ocean recovery from the conflict is decades at the surface and hundreds of years at depth.

5.6.2 Key Uncertainties and Data Gaps

To date, only a single ESM has been used to assess the impact of nuclear war on ocean physical properties and circulation: the CESM (Coupe et al., 2021; Harrison et al., 2022; Mills et al., 2014).

Mesoscale circulation features, such as eddies, play a key role in the transport of heat in the ocean, yet these features are represented using parameterizations in large-scale global climate and ESMs. Such parameterizations were developed to capture the effect of small-scale processes in the present-day ocean, and their utility has not been evaluated for markedly different climate states, such as those brought on by nuclear war.

While the ocean’s response to nuclear war is unlikely to be particularly sensitive to the location or time of year of the conflict (owing to the ocean’s relatively slow response to perturbations), studies suggest that the response is highly sensitive to the total amount of soot injected into the atmosphere. There are a range of other dynamics—such as the wind-driven circulation, water-mass formation, and circulation at intermediate and lower depths—that play an important role in the ocean’s interactions with other components of the climate system and provide important controls on marine ecosystems. These dynamics are relatively slower-evolving and their responses to nuclear exchanges are highly uncertain.

5.7 CRYOSPHERE

5.7.1 State of Knowledge

The cryosphere plays an important role in Earth’s climate due to teleconnections to the large-scale atmospheric circulation (through the meridional temperature gradient, thermal wind balance, and jet stream) and ocean circulations (through surface winds and buoyancy changes from sea-ice changes). A nuclear weapons exchange may affect the cryosphere through two potential pathways. An immediate response may result from the deposition of soot on the cryosphere surface, darkening the surface and decreasing the amount of solar radiation reflected, potentially allowing for a local warming effect and possible melting. This effect, however, is one-time and short-lived, as it will cease once fresh precipitation covers or removes the soot layer. A prolonged response revolves around the cooling following a nuclear exchange due to the decreased solar insolation from increased atmospheric albedo and/or absorption from the stratospheric aerosols (depending on the stratospheric aerosol chemical composition). Cryosphere feedbacks intensify and prolong this cooling in high northern-latitude regions following a nuclear exchange. Mills et al. (2014) found, in response to a 5-Tg BC injection a 10–25% increase in Arctic sea ice that peaks in years 4–7 and persists, relative to the variability observed in a control simulation, for up to 15 years. The Antarctic sea-ice response is considerably larger than the Arctic response, with a 20–75% peak increase occurring 7–15 years after aerosol injection. In both hemispheres, earlier onset of sea ice happens during fall (Mills et al., 2014; Stenke et al., 2013). Snow cover on land also likely increases on similar timescales, although most existing ESM simulations do not directly report on the magnitude of this response. Indirect evidence of an increase in snow cover includes significant decreases in the length of the frost-free growing season in temperate and boreal forest ecosystems 2–6 years after aerosol injection (Mills et al., 2014; Pausata et al., 2016). Over a cooler land surface, a more significant fraction of annual precipitation is expected to occur in the form of snow, and snow is likely to accumulate faster and persist longer in spring.

The build-up of sea ice and snow will amplify surface cooling through two separate pathways. First, planetary albedo is enhanced and, consequently, the surface absorbs less solar radiation, particularly during spring and fall shoulder seasons (Stenchikov et al., 2009). Second, the cooler atmosphere and ice-driven decrease in surface evaporation reduce atmospheric water vapor content, leading to more efficient longwave radiative cooling in high-latitude regions (Ghatak and Miller, 2013). These positive feedbacks with the cryosphere are integrated within contemporary ESM simulations of nuclear war. They may be partly responsible for the longer-duration negative temperature and precipitation anomalies observed for larger-magnitude aerosol simulations described by Toon et al. (2018). For existing simulations considering aerosol injections of up to 150 Tg BC, however, there is no evidence of a runaway positive feedback with the cryosphere that would keep Earth cool for decades or centuries.

A stronger and more sustained aerosol forcing may be required to trigger a more permanent, multidecade, or multicentury Earth system response. For example, modeling and paleoclimate observations of the Little Ice Age may provide insight into the magnitude of such a forcing. Miller et al. (2012) describe radiocarbon evidence for rapid ice-cap expansion between 1275 and 1300 CE following a period of intense volcanism. Within a 50-year interval in the mid-1200s, four volcanic eruptions injected over 60 Tg of SO2 within the stratosphere, and an additional event emitted 258 Tg. In a simulation with the CESM forced with the stratosphere SO2 time series derived from the ice core record, a series of

positive feedbacks increased Arctic ice cover and freshwater export into the North Atlantic, which, in turn, weakened the thermohaline circulation and northward heat transport. Cooling in the North Atlantic Arctic sector persisted for nearly a century at a level approaching 0.75°C (Miller et al., 2012).

5.7.2 Key Uncertainties and Data Gaps

While previous simulations suggest that feedbacks within the cryosphere in response to a nuclear weapons exchange are not very strong and do not appear to significantly affect recovery time, the interplay of short-term and long-term responses remains unclear. An immediate short-term warming effect from the deposition of BC and a longer-term cooling effect from stratospheric aerosol are expected, however, it remains unclear which effect dominates the anomalies in the short term. The warming and cooling effects, their interplay, and the potential role of seasonality may affect other components of the physical Earth system through teleconnections, which remains to be further explored.

While several paleoclimate ice age events have been explored to gain insights into cryosphere feedbacks regarding large-scale and prolonged cooling, their longer timescales may reduce their applicability to the relatively rapid cooling following a nuclear weapons exchange. There may be additional potential opportunities to draw analogs between the rapid cooling associated with a nuclear exchange event and unique rapid cooling events in the paleoclimate. Although the timescale of fluctuations of Milankovitch cycles (Earth’s orbital cycles) are too long to be applicable, the Younger Dryas (YD) was a rapid cooling event, triggered in the Arctic, and spread to the Antarctic through cryosphere teleconnections to large-scale atmospheric and ocean circulations (Cheng et al., 2020). The extent to which the YD may be used as an analog for the cryosphere response to rapid cooling following a nuclear exchange is worth exploring further.

5.8 SUMMARY

Earth system processes will respond to possible perturbations from a nuclear weapons exchange at different timescales and rebound at different rates.

Particulate loading into the upper atmosphere will change Earth’s radiative balance and decrease solar radiation nearly instantaneously. Stratospheric ozone will be depleted in the presence of injected NO and smoke from nuclear blast and fires, with the OC and BC playing an important role in chemistry and radiative processes, likely increasing the radiative effects for the troposphere and potentially losses of ozone and other chemistry. Decreases in ozone lead to increases in UV and expected damages to ecosystems. It is as yet unclear as to whether OC will yield larger declines in PAR and UV radiation than what has been reported for shortwave radiation. In the absence of triggering cryospheric tipping points, global temperatures will respond linearly to these radiative changes with a lag and response times in the ocean system and cryosphere will be longer. The hydrologic cycle response to these radiative changes will have a fast component directly from the solar radiation changes and a slow component because of temperature changes in the surface ocean. Impacts will be felt at the watershed scale, yielding concern about water access. There will be an immediate need for clean water and a potential need to pivot between water banks—snowbanks (short-term storage), aquifers and groundwater (long-term water storage)—as a result of possible contamination.

At varying timescales, particulate loading will also impact ocean state and circulation directly through its three main physical drivers (solar radiation absorption, surface heat exchange, and wind stress) and indirectly through its impact on internal climate variability. Changes in the cryosphere will be driven by radiative effects as well as albedo effects from deposition of soot. Stratospheric ozone will be depleted in the presence of injected NO and smoke from nuclear blast and fires, with the OC and BC playing an important role in chemistry and radiative processes, likely increasing the radiative effects for the troposphere and potentially losses of ozone and other chemistry. Decreases in ozone lead to increases in UV and expected damages to ecosystems. It is as yet unclear as to whether OC will yield larger declines in PAR and UV radiation than what has been reported for shortwave radiation.

These impacted systems will directly translate into ecosystem impacts, elaborated on in Chapter 6. Changes in temperature, PAR, and UV in particular, are important parameters used to evaluate net primary production and impacts on biodiversity of terrestrial and marine systems. Additionally, smaller exchange scenarios, while they play less of a role in Earth systems, can affect ecosystems discussed in Chapter 6.

5.9 FINDINGS AND RECOMMENDATIONS

FINDING 5-1: Current Earth system models must highly oversimplify the aerosol microphysics governing optical properties of smoke, and more detailed process models require an amount of data that is generally unavailable except from brief, site-specific field campaigns or laboratory experiments and these are generally directed at wildfires rather than urban and wildland–urban interface fires, which are more likely to be of concern following a nuclear detonation.

RECOMMENDATION 5-1: The Earth system modeling community should develop “rule-of-thumb” estimates of the plausible range of aerosol optical, chemical, physical, and microphysical properties, as well as

- The mass of aerosol generated per unit mass of source material;

- The altitude of its injection into Earth’s atmosphere and subsequent lofting;

- Its extinction cross section;

- Its single-scattering albedo;

- Its size distribution; and

- Its black carbon and organic carbon content.

Also, Earth system models should be run in a “perturbed parameter ensemble” across this full range of uncertainties for each of these parameters to determine whether the findings regarding environmental effects are robust to these unavoidable uncertainties.

FINDING 5-2: The uncertainty in understanding of cloud–aerosol interactions stems from the paucity of generalizable observations of these interactions together with the lack of high (cloud-resolving) resolution atmospheric models with sufficient fidelity to model both cloud and aerosol microphysical processes under extremely large aerosol loadings such as may occur as a result of detonation of a nuclear weapon.

RECOMMENDATION 5-2: The Earth system modeling community should support systematic campaigns to run cloud-resolving models of cloud–aerosol interactions to model the response of key cloud systems to very large injections of aerosols from a nuclear exchange.

FINDING 5-3: Uncertainty in projecting temperature alterations associated with nuclear detonation contributes to additional uncertainties in estimating global to local impacts on the hydrologic cycle. Based on outcomes from volcanic eruptions, decreases in temperature associated with nuclear detonation are generally expected to decrease regional precipitation with cascading impacts on surface water availability.

RECOMMENDATION 5-3: The Earth system modeling community should pursue research to address uncertainties in characterizing hydrologic processes tied to changes in Earth’s radiation budget as a result of a nuclear exchange.

FINDING 5-4: Many of the modeling studies describe the response of the ocean following considerable climate impact after the very large soot injection scenario, rather than testing sensitivity using a collection of small soot injection scenarios.

FINDING 5-5: While inferences can be drawn about the potential ocean response in other models using geoengineering or volcanic eruption simulations, additional nuclear war studies are needed using alternative model structures and should be executed for a greater range of nuclear exchange scenarios.

RECOMMENDATION 5-4: The Earth system modeling community should develop coordinated and systematic modeling studies to assess the sensitivity of the ocean response to nuclear war as a function of model structure, model resolution, and forcing scenario (particularly for smaller, regional conflicts).