The Age of AI in the Life Sciences: Benefits and Biosecurity Considerations (2025)

Chapter: Appendix A: Mapping the Landscape of AI-Enabled Biological Design

Appendix A

Mapping the Landscape of AI-Enabled Biological Design1

Author: Brian L. Hie

Affiliations: Department of Chemical Engineering, Stanford University, Stanford, CA, USA; Stanford Data Science, Stanford University, Stanford, CA, USA; Arc Institute, Palo Alto, CA, USA

ABSTRACT

This review provides an overview of artificial intelligence–enabled biological models, focusing on their applications in designing biological molecules and systems. We review foundation models that learn data distributions, generative models that sample from these distributions, predictive models that map between biological modalities, and design models that produce desirable biological outputs. The review highlights substantial advances in protein engineering while noting emerging areas in genomic and transcriptomic modeling. We explore these models’ potential to accelerate biological design and reveal new fundamental insights, emphasizing their role in augmenting traditional experimental approaches. We also survey diverse biological datasets underlying these models, emphasizing their crucial role in model development. We also discuss the integration of large language models with biology-specific tools as a promising frontier. Finally, we speculate on future developments, envisioning a synergy between computational simulation and experimental validation in biological discovery and design.

___________________

1 The author is solely responsible for the content of this paper, which does not necessarily represent the views of the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine.

GLOSSARY

Important technical terms, which are italicized throughout the text, are also collected with brief definitions in this glossary, in the order in which they appear in the text:

- Supervised machine learning: A type of machine learning in which models are trained on labeled data to predict specific outputs from given inputs.

- Unsupervised machine learning: A type of machine learning in which models learn patterns and structures from unlabeled data without predefined outputs.

- Scaling hypothesis: An empirical finding that language modeling performance improves predictably as the size of the model, dataset, and computational resources increases.

- Foundation models: Large-scale unsupervised models trained at scale on vast datasets that exhibit broad capabilities across various downstream tasks.

- Multilayer perceptron (MLP): A basic type of neural network with fully connected layers of artificial neurons.

- Convolutional neural networks (CNNs): Neural networks designed to process data dominated by local interactions among features using convolution operations.

- Graph convolutional neural networks (GNNs): Neural networks that operate on graph-structured data, capturing relationships between nodes in the graph.

- Transformer architecture: A neural network architecture that uses self-attention mechanisms to process sequential data, allowing for efficient modeling of long-range dependencies.

- State space models (SSMs): A class of sequence modeling architectures inspired by techniques from signal processing that can be configured to learn local or long-range interactions while maintaining efficient computational scaling.

- Hybrid architectures: Neural network designs that combine different layer types, such as transformer layers or SSM layers, to leverage their respective strengths.

- Autoregressive language modeling: A training objective in which models predict the next token in a sequence given the previous tokens.

- Masked language modeling: A training objective in which models predict masked or corrupted tokens in an input sequence.

- Discrete diffusion modeling: A generative modeling approach that progressively removes and reconstructs artificially corrupted discrete tokens.

- Mean squared error (MSE): A common loss function that measures the average squared difference between predicted and actual values.

- Variational autoencoders (VAEs): Generative models that learn to encode inputs into a latent space and decode them back, often used for generating new data.

- Continuous diffusion modeling: A generative modeling approach that gradually adds and removes noise from continuous data.

- Protein language models: Foundation models trained on large datasets of protein sequences to learn patterns of protein structure and function.

- Single-cell foundation models: Unsupervised models trained on single-cell RNA sequencing data to learn cell-type-specific gene expression patterns.

- Genomic language models: Foundation models trained on DNA sequences to capture patterns of regulatory DNA, RNA, and proteins, as well as their interactions that create systems and organisms.

- One-hot encoding: A simple but effective method of representing categorical data as binary vectors. For a protein sequence, each amino acid is assigned a unique 20-dimensional binary vector in which one element corresponding to that amino acid is 1 and all others are 0.

- Neural sequence embedding: A representation based on using a large pretrained neural network to generate dense vector representations of a sequence, potentially capturing complex patterns within the sequence data learned during pretraining.

INTRODUCTION

From molecular interactions to multicellular organisms, biological complexity has required researchers to develop increasingly sophisticated computational approaches both to understand fundamental biological principles and to engineer new biological systems. Rapid progress in artificial intelligence (AI) also promises to improve our ability to do biological discovery and design and has led to a proliferation of tools with applications that span diverse areas of biological research and engineering. The diversity of these tools, alongside an equally diverse set of applications, creates the need for a comprehensive review that catalogues these innovations and provides a structured framework for understanding their relationships. This paper aims to present a systematic overview of AI-enabled biological models as well as the biological datasets that enable these models. By organizing these tools and tasks coherently, we aim to provide researchers, policymakers, and industry professionals with a clear overview of the current landscape, facilitating more effective

utilization of these technologies and identifying promising areas for future development.

In this review, we begin with an overview and taxonomy of (1) biological foundation models, (2) predictive models, and (3) biological design tools. Our discussion of foundation models will cover biological sequence models within the central dogma, foundation models of biological representations beyond sequences, multimodal models, and generative approaches. We will then explore prediction tools, with special attention to protein structure and function prediction from sequence, as well as multi-omic prediction models. We will then examine biological design tools that generate new sequences with desired properties, which are often aided by property prediction tools. Here, we highlight problems in protein design, structure-based sequence generation, and DNA promoter sequence design. Throughout, we will emphasize the role of generative models and modern deep learning techniques.

We will then consider the datasets used to train these models, assessing their quality and information richness. These include comprehensive sequence databases; structural repositories; large datasets that measure function; and multi-omic datasets spanning genomics, transcriptomics, and proteomics. Finally, we will explore how developments in large language models (LLMs) can be integrated with biology-specific tools. While this integration is still in its early stages, we will speculate on both the potential synergies and challenges in combining general-purpose language models with specialized biological tools, considering applications in scientific literature analysis, experimental design, and biological knowledge integration.

BIOLOGICAL MODELS I: FOUNDATION MODELS

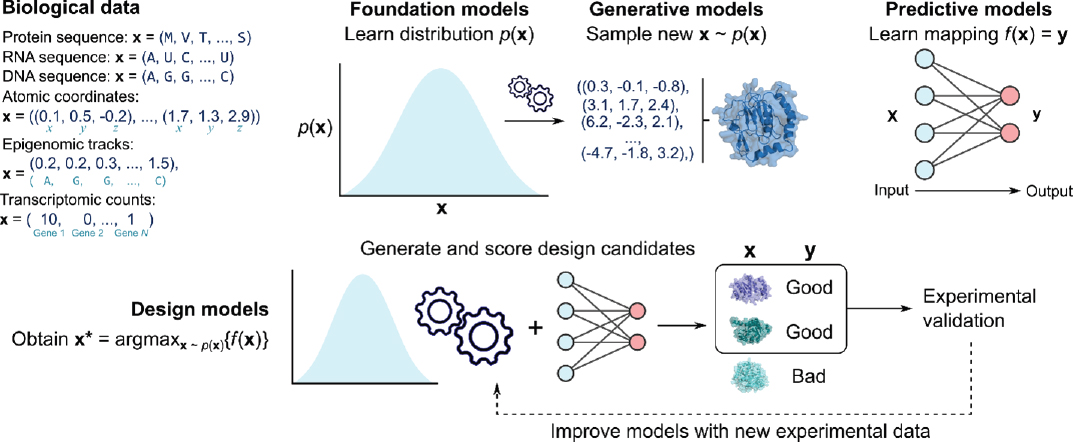

In this review, we define foundation models (Bommasani et al., 2021) using two criteria: (1) the model is trained with an unsupervised objective that attempts to reconstruct the underlying data distribution; and (2) when trained on a sufficiently large and complex dataset, the model demonstrates generalist capabilities across a broad set of downstream tasks, with performance improving as both model and data scale increase (see Figure A-1).

Unlike traditional supervised machine learning, which maps inputs to different types of outputs (e.g., predicting a caption text given an image), unsupervised machine learning models aim to reconstruct their input as accurately as possible (Hastie et al., 2009). This approach encourages the model to learn fundamental patterns and structures within vast amounts of unlabeled data. When trained on sufficiently large and complex datasets (e.g., internet-scale text or images), modern deep learning architectures (Goodfellow, Bengio, and Courville, 2016; Vaswani et al., 2017) have shown the ability to acquire generalist capabilities applicable to a wide

NOTES: Data types include discrete sequences (protein, RNA, and DNA), continuous atomic coordinates (molecules represented as a set of three-dimensional atomic coordinates), continuous epigenomic tracks (epigenomic markers at each genomic position), and discrete transcriptomic count vectors (dimensions corresponding to different genes). Foundation models learn complex data distributions at scale (image illustrates a one-dimensional probability density, but biological distributions are much higher-dimensional), while generative models enable efficient sampling from these distributions (image illustrates a generated set of atomic coordinates that forms a protein structure). Predictive models map between different biological data types, potentially with complex structured outputs. Finally, design models often leverage both generative and predictive models to generate and score design candidates for experimental validation, with new experimental data potentially being used to subsequently improve the models. The image illustrates three protein designs produced by a generative model, two of which are labeled as “good” by a predictive model, which are then selected for experimental validation.

range of downstream tasks, which often differ substantially from the original training objective (Brown et al., 2020). As these models increase in size, they demonstrate improved performance on both the unsupervised reconstruction task and specific downstream tasks. This relationship between model scale and performance is often referred to as the scaling hypothesis or scaling laws (Kaplan et al., 2020; Hoffmann et al., 2022).

Unsupervised models that exhibit these scaling properties are often referred to as foundation models (Bommasani et al., 2021). The ability to learn generalist information across various tasks from a single large-scale unsupervised model distinguishes foundation models from smaller task-specific unsupervised models. The term “foundation” refers to how the information learned through a single unsupervised training objective can transfer to many task-specific downstream applications. Foundation models for text, code, images, and speech have made significant progress in their respective domains. In this review, we examine the current landscape of foundation models for biological data, discussing their progress and potential opportunities.

Preliminaries: Model Architectures and Objectives

Foundation models in biology use neural networks based on a common set of architectures and training objectives. Architectures define how neural connections are arranged within the model, while training objectives are loss functions that guide the optimization of the model. Understanding the distinction between a model’s architecture (e.g., a transformer) and its training objective (e.g., a diffusion model) is crucial for understanding the model’s capabilities and limitations.

Architectures

Several key architectures are fundamental to modern deep learning models and to foundation models in particular. The most standard deep learning architecture is the fully connected neural network, sometimes referred to as a deep neural network or as a multilayer perceptron (MLP) (Rumelhart, Hinton, and Williams, 1986; Goodfellow, Bengio, and Courville, 2016), which consists of an input layer of artificial neurons that receives data, one or more fully connected hidden layers to process the data, and an output layer to generate the final predictions. Convolutional neural networks (CNNs) (LeCun et al., 1989; Goodfellow, Bengio, and Courville, 2016) process information organized by position (e.g., one-dimensional text or two-dimensional images), focusing on interactions between nearby elements. Graph convolutional neural networks (GNNs) (Scarselli et al., 2009; Wu et al., 2019), a subvariant of CNNs, model elements as nodes

and consider interactions only between connected nodes, making them useful for graph-representable data. These architectures excel when the data distribution is dominated by local interactions. The transformer architecture (Vaswani et al., 2017), based on an operation called self-attention (Bahdanau, Cho, and Bengio, 2014), allows each element in an input sequence to interact with all others, regardless of distance. This enables the capture of both local and long-range dependencies, proving remarkably effective for many tasks. However, its all-by-all element comparison leads to quadratic computational scaling with sequence length. State space models (SSMs) (Gu and Dao, 2023; Poli et al., 2023) are an emerging class of architectures that can be configured to prefer learning local or long-range interactions while maintaining near-linear computational scaling with sequence length. Hybrid architectures combine different layer types (e.g., a mixture of CNN layers, transformer layers, or SSM layers) within a single deep neural network, potentially benefiting from the strengths of each constituent architecture (Poli et al., 2024).

Objectives

A foundation model can be trained with different objectives that all attempt, in some way, to reconstruct the input. Different objectives are used depending on whether the underlying data are discrete or continuous. When data samples are sequences of discrete tokens (e.g., a sequence of DNA base pairs), a typical language model is trained via autoregressive language modeling in which the model is asked to predict the next token given a sequence prefix, enforcing a left-to-right order (Radford et al., 2019). An alternative training objective for discrete sequence models is masked language modeling in which a model is asked to predict the true values of positions that are masked or corrupted in the input (Devlin et al., 2018). A generalization of masked language modeling is discrete diffusion modeling in which a model is trained to progressively remove artificially masked or corrupted tokens in its input (Lou, Meng, and Ermon, 2023). When the input takes the form of continuous data (e.g., an image containing pixels along a color spectrum), a common objective is to simply minimize the mean squared error (MSE) separating the prediction value from the ground truth value (Hastie et al., 2009). For example, MSE loss is frequently used in a class of models called variational autoencoders (VAEs) (Kingma and Welling, 2014), which encode the input as a Gaussian latent variable encouraging a smooth representation of the data, combined with an MSE loss that compares the output of a decoder with the original sample. While VAEs can successfully represent some simple data distributions, more powerful recent models have been trained with continuous diffusion modeling (Ho, Jain, and Abbeel, 2020) in which, as in the discrete

case, the model is trained to iteratively remove artificial noise from an input sample. Importantly, any architecture can be trained with any objective, though certain architectures are commonly paired with certain objectives (e.g., autoregressive transformer models).

Generative Models

Some objectives are particularly suited for efficient sampling from learned probability distributions. Autoregressive models, for example, enable left-to-right sampling based on the model’s next-token predictions. A VAE enables decoding of Gaussian noise into new samples. Both continuous and discrete diffusion models facilitate iterative denoising or reconstruction of purely noised or corrupted samples. Models trained with these sampling-friendly objectives are often referred to as generative models.

Modeling the Distribution of Sequences

We first consider a major class of biological foundation models in which the underlying data are a sequence of discrete tokens, where each token corresponds to a DNA base pair, an RNA base pair, or a protein amino acid. We describe notable models, along with their corresponding model architecture and objective, in the sections below and in Table A-1.

TABLE A-1 Foundation Models of Biological Data

| Category | Model name | Architecture | Training objective | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| General protein sequence | ESM-1b | Transformer | Masked language modeling | Rives et al., 2021 |

| General protein sequence | ESM-1v | Transformer | Masked language modeling | Meier et al., 2021 |

| General protein sequence | ESM-2 | Transformer | Masked language modeling | Lin et al., 2023 |

| General protein sequence | ESM3 | Transformer | Discrete diffusion modeling | Hayes et al., 2024 |

| General protein sequence | ProGen | Transformer | Autoregressive language modeling | Madani et al., 2021 |

| General protein sequence | ProGen2 | Transformer | Autoregressive language modeling | Nijkamp et al., 2023 |

| General protein sequence | CARP | CNN | Masked language modeling | Yang, Fusi, and Lu, 2024 |

| Category | Model name | Architecture | Training objective | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| General protein sequence | ProteinBERT | Transformer | Masked language modeling | Brandes et al., 2023 |

| General protein sequence | TAPE | Transformer | Masked language modeling | Rao et al., 2019 |

| General protein sequence | ProtTrans | Transformer | Autoregressive language modeling | Elnaggar et al., 2022 |

| General protein sequence | ProtGPT2 | Transformer | Autoregressive language modeling | Ferruz, Schmidt, and Höcker, 2022 |

| General protein sequence | RITA | Transformer | Autoregressive language modeling | Hesslow et al., 2022 |

| Antibody protein sequence | AbLang | Transformer | Masked language modeling | Olsen, Moal, and Deane, 2022 |

| Antibody protein sequence | IgBERT | Transformer | Masked language modeling | Kenlay et al., 2024 |

| Antibody protein sequence | IgT5 | Transformer | Autoregressive language modeling | Kenlay et al., 2024 |

| Antibody protein sequence | AntiBERTa | Transformer | Autoregressive language modeling | Leem et al., 2022 |

| Antibody protein sequence | AntiBERTy | Transformer | Autoregressive language modeling | Ruffolo, Gray, and Sulam, 2021 |

| Antibody protein sequence | Sapiens | Transformer | Masked language modeling | Prihoda et al., 2022 |

| Coding RNA sequence | CaLM | Transformer | Masked language modeling | Outeiral and Deane, 2024 |

| Coding RNA sequence | CodonBERT | Transformer | Masked language modeling | Ren et al., 2024 |

| Noncoding RNA sequence | RiNALMo | Transformer | Masked language modeling | Penić et al., 2024 |

| Noncoding RNA sequence | RNA-FM | Transformer | Masked language modeling | Chen et al., 2022 |

| Noncoding RNA sequence | Uni-RNA | Transformer | Masked language modeling | Wang et al., 2023 |

| Noncoding RNA sequence | RNAErnie | Transformer | Masked language modeling | Wang et al., 2024 |

| Genomic DNA sequence | GenSLM | Transformer | Autoregressive language modeling | Zvyagin et al., 2023 |

| Category | Model name | Architecture | Training objective | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Genomic DNA sequence | Nucleotide Transformer | Transformer | Masked language modeling | Dalla-Torre et al., 2023 |

| Genomic DNA sequence | GPN | CNN | Masked language modeling | Benegas, Batra, and Song, 2023 |

| Genomic DNA sequence | regLM | Transformer | Autoregressive language modeling | Lal et al., 2024 |

| Genomic DNA sequence | HyenaDNA | SSM | Autoregressive language modeling | Nguyen, Poli, Faizi, et al., 2024 |

| Genomic DNA sequence | Caduceus | SSM | Autoregressive language modeling | Schiff et al., 2024 |

| Genomic DNA sequence | Evo | Hybrid (SSM + Transformer) | Autoregressive language modeling | Nguyen, Poli, Durrant, et al., 2024 |

| Molecular structure | RFdiffusion | Hybrid (GNN + Transformer) | Continuous diffusion | Watson et al., 2023 |

| Molecular structure | Chroma | GNN | Continuous diffusion | Ingraham et al., 2023 |

| Molecular structure | Protpardelle | Transformer | Continuous diffusion | Chu et al., 2024 |

| Cellular transcriptomes | Geneformer | Transformer | Masked language modeling | Theodoris et al., 2023 |

| Cellular transcriptomes | scBERT | Transformer | Masked language modeling | Yang et al., 2022 |

| Cellular transcriptomes | scFoundation | Transformer | Masked language modeling | Hao et al., 2024 |

| Cellular transcriptomes | scGPT | Transformer | Specialized autoregressive language modeling | Cui et al., 2024 |

NOTE: Summary of various foundation models across different categories of biological data, including protein sequences, antibody sequences, RNA sequences, genomic DNA sequences, molecular structures, and cellular transcriptomes. For each model, the architecture, training objective, and citation are also provided.

General Protein Sequence

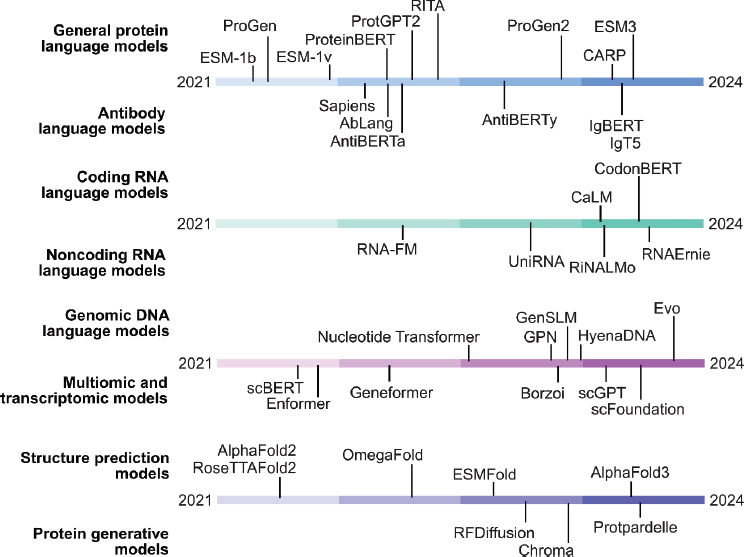

Many biological sequence models have been trained on large corpora of protein amino acid sequences across diverse protein families and have been shown to learn properties of both structure and function (Bepler and Berger, 2021). By learning which positions in a sequence input are useful when predicting values at other positions, protein language models identify covarying positions across protein evolution, which typically reflects structural proximity. By learning which amino acids are more likely (or unlikely) at given positions, they also learn which mutations are better (or worse) tolerated. A notable suite of protein language models is the ESM family of models, including the first-generation ESM-1b model (released as a general-purpose foundation model) (Rives et al., 2021) and ESM-1v models (specialized to the task of variant effect prediction) (Meier et al., 2021) and the second-generation ESM-2 models (released at different scales from 6 million to 15 billion parameters) (Lin et al., 2023); we discuss ESM3, the third-generation ESM model (Hayes et al., 2024), under the subsection on multimodal models below. ESM-1 and ESM-2 models are trained with masked language modeling and use a standard transformer architecture. Another notable class of models is the ProGen family of models, including the first ProGen model (Madani et al., 2021) and ProGen2 (released at different scales from 151 million to 6 billion parameters) (Nijkamp et al., 2023). ProGen models are also transformers trained on diverse protein families using an autoregressive language modeling objective and have been used to sample diverse sequences from enzyme families while retaining catalytic activity (Madani et al., 2023). Several other notable masked language models, which are evaluated and used as general-purpose protein language models, include CARP (Yang, Fusi, and Lu, 2024), ProteinBERT (Brandes et al., 2023), and TAPE (Rao et al., 2019). Other notable autoregressive language models include ProtTrans (Elnaggar et al., 2022), ProtGPT (Ferruz, Schmidt, and Höcker, 2022), and RITA (Hesslow et al., 2022).

Antibody Protein Sequence

Several protein language models have been developed specifically for antibody sequences. These include AbLang (Olsen, Moal, and Deane, 2022), IgBert and IgT5 (Kenlay et al., 2024), AntiBERTa (Leem et al., 2022), AntiBERTy (Leem et al., 2022), and Sapiens (Prihoda et al., 2022). The ProGen2 suite also contains a version that is fine-tuned on antibody sequences. These models typically train on sequence datasets of the heavy chain variable region (VH) and light chain variable region (VL), which form the antigen-binding part of antibodies and are highly diverse. The largest antibody sequence database is the Observed Antibody Space (OAS),

containing ~2.4 billion VH and VL sequences from animal immune cells. Interestingly, specializing models on antibody datasets like OAS often results in degraded performance on tasks like mutational effect prediction compared to general protein language models, suggesting that some antibody-specific models may lose general structural and functional information learned by training on many protein families (Nijkamp et al., 2023; Hie et al., 2024).

Coding RNA Sequence

Each protein amino acid is encoded by an RNA codon with three base pairs, where 64 codons encode the 20 canonical amino acids plus three stop codons. Rather than train on sequences with an amino acid vocabulary, some models train on sequences with a codon vocabulary. Codon models can capture structural and functional information similar to protein language models while also incorporating codon biases that contain species-related information. In turn, these codon biases can have functional effects on biological processes like translation rate or fidelity. Codon language models include CaLM (Outeiral and Deane, 2024) and CodonBERT (Ren et al., 2024), which can be competitive with or even outperform protein language models on function prediction tasks and transcript abundance datasets.

Noncoding RNA Sequence

Sequence models are also trained on large databases of noncoding RNA (ncRNA) sequences, such as sequences of transfer RNAs (tRNAs), ribosomal RNAs (rRNAs), or regulatory ncRNAs. Many ncRNAs rely on functionally relevant secondary or tertiary structure formation, and mutations can substantially affect their functional activity. Inspired by the success of protein language models at learning analogous aspects of structure and function, ncRNA language models are evaluated on similar tasks. Notable ncRNA models include RiNALMo (Penić et al., 2024), RNA-FM (Chen et al., 2022), Uni-RNA (Wang et al., 2023), and RNAErnie (Wang et al., 2024). These models are smaller than typical protein language models (the largest is RiNALMo at 650 million parameters) and have made some early-stage progress on structure and function prediction tasks.

Genomic DNA Sequence

DNA sequence, the fundamental layer of information in molecular biology, encodes proteins, RNA, and regulatory elements. The vast scale of genomic data presents substantial challenges for sequence modeling, leading

to the development of various genomic sequence models with different architectures. These range from models that combine nucleotides into larger tokens, such as GenSLM (Zvyagin et al., 2023) or Nucleotide Transformer (Dalla-Torre et al., 2023), to those maintaining single nucleotide resolution that operate at shorter sequence lengths, such as GPN (Benegas, Batra, and Song, 2023) or regLM (Lal et al., 2024), with recent architectures like Hyena or Mamba offering longer context windows (Nguyen, Poli, Faizi, et al., 2023; Schiff et al., 2024). Genomic sequence models have diverse applications, including fitness prediction of genetic variants using models like GPN-MSA (Benegas et al., 2024) (similar to how protein sequence models are used for fitness prediction). Another major application is generative, with models like regLM or DNA-Diffusion (DaSilva et al., 2024) emphasizing novel sequence design via autoregressive sampling or discrete diffusion. Models like GenSLM and Nucleotide Transformer emphasize transfer learning for tasks such as gene annotation and chromatin accessibility prediction using the embeddings learned by the DNA language model. More capable language models, trained with billions of parameters on hundreds of billions of base pairs with long context, such as Evo (Nguyen, Poli, Durrant, et al., 2024), have the capacity to make progress on both predictive and generative tasks and at multiple levels of biological complexity.

Modeling the Distribution of Other Biological Modalities

While sequence models have dominated much of the recent progress in biological foundation models, there are notable efforts to model distributions of other biological data modalities that also leverage modern architectures, training objectives, and scale. These non-sequence modalities provide complementary insights into biological systems beyond the genetic information contained in DNA, RNA, and protein sequences.

Molecular Structure

Recent advancements in generative models have expanded to encompass atomic-level protein structures, most notably in the realm of de novo protein design, in which the goal is to design proteins with structures that are unconstrained by the natural repertoire of protein structures and folds. Fundamentally, these molecules are represented as a set of atoms, where an atom is defined by its (x, y, z) coordinates. Early generative models of protein structure based on VAEs were proposed to generate the backbone atomic coordinates of proteins (Lin et al., 2021). Diffusion modeling, which led to more powerful generative models of images, has also shown particular promise in protein structure generation. An early protein diffusion model demonstrating the feasibility of this approach was proposed

by Anand and Achim (2022); more advanced protein backbone diffusion models, such as RFdiffusion (Watson et al., 2023) and Chroma (Ingraham et al., 2023), apply progressive noise to known protein backbone coordinates during training and learn to reverse this process, generating diverse and realistic protein backbones. Recent models such as Protpardelle (Chu et al., 2024) have extended this approach to generating all of the atoms in a protein structure (both the backbone atoms and side-chain atoms). These generative models are either applied unconditionally (simply generating a complete structure from scratch) or conditionally (fixing a part of the structure and generating a compatible completion of the structure). Conditional generation is particularly useful for generating a protein that binds to another target protein (Bennett et al., 2024), where the user conditions on the target and the binder are generated by, for example, a diffusion model. Beyond proteins, conditional diffusion models have also been used to design small molecules or peptides that bind to a given protein, which has applications in small molecule drug design (Peng et al., 2022; Huang et al., 2024).

Cellular Transcriptomes

Ideas from sequence modeling have influenced models of transcriptomic data collected by single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) technologies. In this formulation, each sample represents a single cell described by a vector of integer RNA molecule counts, corresponding to expression levels of different genes. Single-cell foundation models adapt concepts from autoregressive and masked language modeling, applying analogous objectives to these gene expression vectors. Several of these single-cell foundation models have been proposed, including Geneformer (Theodoris et al., 2023), scBERT (Yang et al., 2022), scFoundation (Hao et al., 2024), and scGPT (Cui et al., 2024), which all learn patterns in scRNA-seq data by predicting gene expression levels of some genes based on the gene expression levels of other genes. Consequently, these models can generate realistic expression profiles, impute missing data, and provide insights into cell types and states. While these models could theoretically also learn complex genetic interactions and regulatory networks, the extent to which these higher-order concepts are learned directly by the current models during pretraining appears to be more limited (Kedzierska et al., 2023). An important challenge in this domain is the lack of pretraining data available compared to protein or genomic language models. While there are 50–100 million publicly available single-cell transcriptomes, these represent around several thousand underlying cell types; and while a transcriptome is theoretically high-dimensional (~20,000 genes in the human transcriptome), many of these dimensions are highly correlated and can be well represented by tens of principal components. Progress in

single-cell transcriptomic modeling is most likely data limited compared to other domains.

Multimodal Foundation Models

While we have primarily discussed single-modality foundation models, a growing trend is the development of multimodal foundation models in biology. These models are trained with unsupervised objectives to learn information about multiple biological modalities simultaneously. Some models, like the genomic sequence model Evo (Nguyen, Poli, Durrant, et al., 2024), use a single fundamental data type (DNA) to capture information across multiple modalities (RNA and protein), enabling multimodal generative tasks across the central dogma. Others, such as ESM3 (Hayes et al., 2024), explicitly combine data from disparate modalities, taking protein sequence, structure, and function as input and training with a masked reconstruction objective across all three.

The motivation for multimodal learning extends beyond capturing different facets of biological processes. Integrating multiple data modalities allows for the incorporation of additional constraints in the learning process, potentially reducing the number of learned parameters and leading to more compact yet equally capable models. This approach holds promise for democratizing access to powerful models, making them more accessible to academic laboratories and individual researchers.

Furthermore, multimodal models offer an opportunity to incorporate biological priors that encode physics and expert knowledge. This is crucial because data alone may never be sufficient to fully capture complex biological processes occurring at various timescales. By integrating these priors, models could learn more robust and biologically relevant representations. For instance, recent work has demonstrated that while language models trained solely on sequence data can capture some structural information, they still struggle at remote homology prediction, highlighting that sequence-only approaches could benefit from additional data modalities (Kabir et al., 2024).

However, significant challenges remain in multimodal biological modeling. Current models often do not fully account for the disparate processes, timescales, granularities, and varying fidelities of different biological data types. Resolving these discrepancies and effectively integrating diverse data sources remains an open area of research.

Despite these challenges, the development of multimodal foundation models represents a promising direction for complex biological modeling. The ability of these models to learn joint data distributions, incorporate diverse constraints, and potentially yield more efficient models aligns well with biology’s inherently multimodal and multiscale nature. As the field

progresses, we anticipate further advancements in integrating multiple data modalities and biological priors, leading to more comprehensive and robust models of biological systems.

BIOLOGICAL MODELS II: PREDICTIVE MODELS

Predictive models in computational biology serve a crucial role by mapping one biological modality to another (see Figure A-1), often aimed at simulating complex biological processes or experimental outcomes. Unlike foundation models, which are unsupervised and learn general patterns, prediction models are typically supervised and designed for specific tasks. These models aim to transform input data, such as biological sequences, into output predictions of properties, structures, or functions that are often experimentally challenging or resource-intensive to determine. This approach has led to advances in various areas of biology, from protein structure prediction to functional annotation and epigenomic profiling.

There are many supervised or predictive modeling efforts in biology, often using lightweight models either with simple input features or input features derived from a foundation model. In this review, rather than attempting to document all examples of supervised learning in biology, we instead focus on challenging prediction tasks that are widely used as part of biological design workflows. These prediction tasks are largely focused on biomolecular applications given the large amount of research focused on protein design, though we also review prediction of epigenomic features that is used in DNA regulatory design as well. We also focus mostly on prediction tasks involving complex structured outputs that often require specialized neural network architectures and information-rich training datasets. We also provide a summary of these predictive models in Table A-2.

| Category | Model name | Input data type | Output data type | Citation(s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sequence to structure | AlphaFold | Protein sequence | 3D protein structure | Senior et al., 2020 |

| Sequence to structure | AlphaFold2 | Protein sequence | 3D protein structure | Jumper et al., 2021 |

| Sequence to structure | AlphaFold3 | Biomolecular sequence | 3D biomolecular structure | Abramson et al., 2024 |

| Sequence to structure | ESMFold | Protein sequence | 3D protein structure | Lin et al., 2023 |

| Category | Model name | Input data type | Output data type | Citation(s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sequence to structure | OmegaFold | Protein sequence | 3D protein structure | Wu et al., 2022 |

| Sequence to structure | RoseTTAFold All-Atom | Biomolecular sequence | 3D biomolecular structure | Krishna et al., 2024 |

| Image to structure | CryoDRGN | Cryo-EM images | 3D protein volume | Zhong et al., 2021 |

| Image to structure | cryoSPARC | Cryo-EM images | 3D protein volume | Punjani et al., 2017 |

| Image to structure | tomoDRGN | Cryo-ET images | 3D protein volume | Powell and Davis, 2024 |

| Image to structure | CryoDRGN-ET | Cryo-ET images | 3D protein volume | Rangan et al., 2024 |

| Protein fitness | Low-N supervision | Protein sequence | Fitness score | Biswas et al., 2021; Hsu, Nisonoff, et al., 2022 |

| Protein fitness | General language models | Protein sequence | Fitness score | Livesey and Marsh, 2020, 2023; Meier et al., 2021 |

| Viral protein fitness | Constrained Semantic Change Search (CSCS) | Viral protein sequence | Escape score | Hie et al., 2021 |

| Viral protein fitness | EVEscape | Viral protein sequence | Escape score | Thadani et al., 2023 |

| Viral protein fitness | Early-Warning System | Viral protein sequence | Escape score | Beguir et al., 2023 |

| Viral protein fitness | CoVFit | Viral protein sequence | Epidemiological fitness | Ito et al., 2024 |

| Multi-omic prediction | Enformer | DNA sequence | Epigenomic tracks | Avsec et al., 2021 |

| Multi-omic prediction | Borzoi | DNA sequence | Gene expression tracks | Linder et al., 2023 |

NOTE: This table summarizes various predictive models across different categories, including sequence-to-structure prediction, image-to-structure reconstruction, protein fitness prediction, viral fitness prediction, and multi-omic prediction. For each model, the input and output data types are provided, illustrating the diverse range of prediction tasks using modern machine learning methods.

Notable Prediction Task 1: Molecular Structure Prediction

Sequence to Structure

Protein structure prediction, exemplified by AlphaFold, represents a notable breakthrough in computational biology. This task involves determining a protein’s three-dimensional (3D) structure from its amino acid sequence. Notable modeling efforts that advanced this field incorporated physical information, coevolutionary statistical data, and deep learning architectures. Building on these ideas and the preliminary success of an initial AlphaFold model (Senior et al., 2020), AlphaFold2 achieved prediction performance that approaches or matches experimental accuracy for many important proteins, reducing reliance on time-consuming experimental methods like X-ray crystallography (Jumper et al., 2021). The latest iteration, AlphaFold3, extends molecular structure prediction beyond proteins to include other modalities such as small molecules, nucleic acids, and lipids from their sequence descriptions (Abramson et al., 2024). Complementing these advancements, language models like ESM have also contributed to structure prediction models. Trained on vast protein sequence datasets, these models capture deep evolutionary relationships and form the basis for single-sequence structure prediction tools such as ESMFold (Lin et al., 2023) and OmegaFold (Wu et al., 2022). By leveraging the rich information encoded in protein language models, these tools can predict structures accurately without requiring multiple sequence alignments of evolutionarily related proteins that are critical to AlphaFold’s performance. However, language model–based approaches to protein structure prediction have not yet matched the level of accuracy achieved by AlphaFold2 or AlphaFold3. Aside from AlphaFold3, other notable models attempt to predict multimodal biomolecular structures. RoseTTAFold All-Atom (Krishna et al., 2024) models the structures of proteins alongside nucleic acids, metal ions, small molecules, and post-translational modifications, though with lower accuracy than AlphaFold3. Diffusion modeling approaches have been applied to predicting the structural pose of small molecules that bind to proteins (Corso et al., 2023), which is an important problem in small molecule drug design.

Image to Structure

Complementing sequence-based structure prediction, an important area of research focuses on inferring protein volumes from cryo-electron microscopy (cryo-EM) and cryo-electron tomography (cryo-ET) images (Benjin and Ling, 2020). A protein volume is a 3D representation of the electron density distribution within a protein, depicting the spatial

arrangement of its mass. Notable work in this field includes CryoDRGN (Zhong et al., 2021) and cryoSPARC (Punjani et al., 2017; Punjani and Fleet, 2021), which use deep learning techniques to reconstruct (potentially heterogeneous) 3D protein volumes from cryo-EM data, and tomoDRGN (Powell and Davis, 2024) and CryoDRGN-ET (Rangan et al., 2024) for 3D reconstruction from cryo-ET data. Although these volumes do not directly provide atomic-level details, they serve as crucial intermediates in structure determination; to derive the actual protein structure from a volume, researchers employ computational methods that fit atomic models into the density map, leveraging prior knowledge of the protein’s sequence and secondary structure predictions (Benjin and Ling, 2020). CryoDRGN and similar approaches are particularly valuable for capturing protein dynamics, as they can reveal conformational heterogeneity and structural flexibility. By leveraging advanced machine learning algorithms to generate and interpret these volumes, these methods enhance the determination of structures for challenging protein targets and improve understanding of protein behavior in near-native environments.

Notable Prediction Task 2: Protein Fitness Prediction

Many supervised machine learning models predict protein fitness as a scalar value, trained on existing datasets that map protein sequences to fitness values. These models input protein sequences, represented either through simple one-hot encoding (where each amino acid is assigned a unique binary vector) or more advanced neural sequence embeddings from foundation models. The choice of input representation can substantially impact model performance. Most supervised models use straightforward approaches such as linear regression, Gaussian process regression for predictions with uncertainty estimates, random forest regressors, or small MLPs or CNNs. The choice of features and the regression model often depends on factors like dataset size, fitness landscape complexity, and requirements for interpretability or uncertainty quantification (Biswas et al., 2021; Hsu, Nisonoff, et al., 2022).

Unsupervised models of protein sequences, trained on large datasets of naturally occurring proteins, have demonstrated remarkable success in zero-shot prediction of mutational effects on protein fitness (Livesey and Marsh, 2020, 2023). These models leverage sequence likelihoods to predict the impact of mutations, with lower likelihoods generally indicating more deleterious effects. This computational approach can be thought of as an in silico version of deep mutational scanning (DMS), an experimental technique that measures the functional effects of thousands of small mutations in a protein (e.g., all possible single-amino-acid substitutions) (Fowler and Fields, 2014). DMS data are used to evaluate

these unsupervised models and, in some cases, to train supervised models for comparison.

Interestingly, unsupervised models often outperform supervised models at mutational effect prediction tasks, particularly in zero-shot scenarios. For example, the likelihoods from language models like ESM-1v and ESM-2 are competitive mutational effect predictors across many DMS datasets (Meier et al., 2021) and across datasets of clinically relevant human disease variants (Brandes et al., 2023), though there is still room for improvement in variant effect prediction (Bromberg et al., 2024). This advantage likely stems from the unsupervised models capturing broad evolutionary information across protein families, providing a strong prior for fitness effects (Hie et al., 2024). In contrast, supervised models may overfit to assay-specific nuances, limiting their generalizability. To assess the effectiveness of these approaches, benchmark suites such as ProteinGym (Notin et al., 2024) and FLIP (Fitness Landscape Inference for Proteins; Dallago et al., 2021) compile diverse DMS datasets, allowing for comprehensive evaluation of predictive models across various proteins and experimental conditions.

Predicting Viral Infectivity or Escape

Building on the broader fitness-prediction applications of protein sequence models, these approaches have found critical relevance in virology. Unsupervised protein language models have shown promise in predicting viral infectivity and escape, utilizing high-throughput DMS data that measure how amino acid changes affect these properties (Haddox, Dingens, and Bloom, 2016; Haddox et al., 2018; Lee et al., 2018; Starr et al., 2020; Wu et al., 2020; Starr et al., 2022). Viral escape refers to mutations allowing viruses to evade immune responses, while infection is mediated by specific proteins interacting with host cell receptors. Initial work demonstrated that statistical properties learned by protein sequence models correspond to viral escape characteristics (Riesselman, Ingraham, and Marks, 2018; Hie et al., 2021; Thadani et al., 2023). Subsequent work showed that larger protein language models like ESM, either zero-shot or when fine-tuned on viral proteins, can competitively model various aspects of viral evolution (Hie, Yang, and Kim, 2022; Beguir et al., 2023; Ito et al., 2024; Lamb et al., 2024). These diverse methods offer promising tools for studying mutational effects on near-term infectivity or escape, but their ability to predict long-term viral evolution remains limited. Viral evolution across multiple generations and long evolutionary trajectories inherently has substantial levels of uncertainty. Better models are needed to forecast viral evolution accurately over the long term, highlighting the ongoing challenges in translating these insights into reliable vaccine design and pandemic preparedness strategies.

Notable Prediction Task 3: Multi-omic Sequence Prediction

Another notable direction in biological prediction tasks relevant to design workflows is the development of tools that infer complex genomic and epigenomic features directly from DNA sequences. Enformer (Avsec et al., 2021) predicts multiple epigenomic tracks from raw DNA sequence, capturing regulatory interactions across long genomic distances. These tracks typically include data on chromatin accessibility, histone modifications, and transcription factor binding, often measured experimentally through techniques like ATAC-seq (Assay for Transposase-Accessible Chromatin using sequencing). Extending these models, Borzoi (Linder et al., 2023) focuses on predicting gene expression tracks, which reflect the activity levels of genes across different cell types or conditions, usually measured by RNA-seq. Both models use CNN deep learning architectures to learn the intricate relationships between DNA sequence and functional genomic readouts. These approaches are valuable as they provide insights into gene regulation and expression without requiring extensive experimental data when given new DNA sequences, and are therefore used as part of DNA regulatory element design pipelines (which we review below) to evaluate if a given design produces the desired impact on the downstream epigenomic sequence. However, like other predictive models in computational biology, the predictions of these models, and subsequent designs, should be interpreted cautiously and validated experimentally when possible.

BIOLOGICAL MODELS III: DESIGN MODELS

We have so far considered foundation models that learn unsupervised information (e.g., learning the distribution of sequences) and predictive models that map sequences to functions. We now consider biological design, which benefits from combining both generative and predictive models (see Figure A-1). This section examines the landscape of machine learning–guided biological design tools; their underlying principles; and their potential to transform key processes in drug discovery, enzyme engineering, and synthetic biology. We begin with a general discussion on how advancements in both generative models and predictive models can be combined to improve biological design pipelines. As protein design has been a primary focus of biological design efforts, we then review two major categories in this field: function-guided adaptive protein design, which relies on iterative rounds of experimental testing and evaluation, and de novo protein design, which emphasizes the creation of structurally novel proteins. We conclude by exploring machine learning–guided biological design beyond protein molecules.

Generative Models, Predictive Models, and Biological Design

In the earlier section on foundation models, we described how generative models enable a user to efficiently sample from a complex data distribution. While generative models play a crucial role in biological design tasks, they are often insufficient on their own. These models learn to capture the distribution of naturally occurring biological sequences or structures, providing a foundation for generating plausible new designs. However, generating designs with specific desired functions requires additional steps. Typically, generative models are coupled with predictive models in a rejection sampling framework (Hastie et al., 2009); in this approach, the generative model proposes candidate sequences, which are then evaluated by a predictive model. Only sequences predicted to have the desired function are selected for experimental testing, while the remainder are “rejected.” This combination allows for efficient exploration of the vast sequence space while focusing on promising candidates. This strategy not only increases the likelihood of discovering sequences with desired properties but also significantly reduces the experimental burden by prioritizing the most promising candidates for laboratory validation (Hie and Yang, 2022).

Beyond rejection sampling, a predictive scoring function could be used to directly bias the generative model’s samples using algorithms like supervised fine-tuning (SFT), reinforcement learning techniques, or direct preference optimization (DPO) (Rafailov et al., 2024). SFT involves further training the generative model on a curated dataset of high-scoring sequences to shift its distribution. Reinforcement learning techniques, such as proximal policy optimization (Schulman et al., 2017; Ouyang et al., 2022), iteratively update the model to maximize a reward signal derived from the scoring function. DPO aligns the model’s outputs with desired preferences without explicit reward modeling, often using pairwise comparisons between positively and negatively labeled samples (Rafailov et al., 2024). These approaches aim to align the generative model’s output more closely with the desired functional properties, potentially increasing the efficiency of the design process compared to simple rejection sampling.

Notable Design Task 1: Function-Guided Adaptive Protein Design

Function-guided biological design specifies a desirable biological function and aims to produce a sequence that exhibits that desirable function. In recent years, adaptive machine learning approaches have emerged as powerful tools for function-guided biological design, particularly in the realm of protein engineering to navigate the vast and complex landscape of possible sequences. These methods combine computational predictions with iterative experimental validation to search efficiently for proteins with desired properties (Hie and Yang, 2022).

At the heart of many of these approaches is Bayesian optimization, a strategy for finding the global optimum of an unknown function. In the context of protein engineering, this function might map protein sequences to a desired property like enzyme activity or stability. Bayesian optimization typically uses a probabilistic surrogate model, often a Gaussian process, to approximate this unknown function (Rasmussen and Williams, 2005). Gaussian processes are flexible, nonparametric models that can capture complex relationships and provide uncertainty estimates for their predictions.

The optimization process iterates between using the surrogate model to select promising candidates and experimentally testing these candidates to refine the model. This selection is guided by an acquisition function, which balances the exploitation of designs predicted to be good with the exploration of uncertain regions of the sequence space. A common acquisition function is the upper confidence bound, which combines the predicted value with the uncertainty of that prediction (Rasmussen and Williams, 2005). Several studies have used Gaussian process predictions and uncertainty estimates to guide iterative rounds of experiments (Romero, Krause, and Arnold, 2013; Hie, Bryson, and Berger, 2020; Greenhalgh et al., 2021).

Generative models, such as VAEs or protein language models, are often used to propose new candidate sequences. These models can learn the distribution of valid protein sequences and generate novel sequence designs that can then be tested for functional activity. For example, Madani and colleagues (2023) use an autoregressive protein language model to generate lysozyme proteins with active catalytic activity and as low as 40 percent sequence identity to natural lysozymes. Similarly, Hayes and colleagues (2024) use a masked language model combined with rounds of experimental data collection to design a green fluorescent protein (GFP) homolog with less than 60 percent sequence identity to natural GFPs.

Adaptive sampling techniques can further refine these generative models based on the results of the surrogate model, steering the generation process toward more promising regions of the sequence space. A key advantage of these methods is their ability to learn and improve over multiple rounds of experimentation. This iterative process, sometimes called active learning, allows the models to become increasingly accurate and efficient at identifying promising designs (Hie and Yang, 2022).

Because active learning often requires multiple rounds of experimental data collection, a recent trend has been to augment these processes with automated experimental platforms. For example, Rapp, Bremer, and Romero (2024) use multiple rounds of Bayesian optimization with a Gaussian process combined with an experimental pipeline with a heavy use of automation to design a suite of more active enzymes. These approaches could accelerate the design-build-test cycle in biological engineering, but

laboratory automation pipelines are still difficult to set up and are less reliable for more complex biological assays. While relatively robust binding measurements or enzymatic activity assays are amenable to laboratory automation in the immediate term, improvements in laboratory automation technologies could improve the generalizability of this approach.

Other challenges to function-guided adaptive learning strategies remain. Protein sequences are discrete and high-dimensional, which can pose difficulties for traditional optimization techniques. Additionally, biological experiments often involve large batch sizes and limited rounds of testing, which require careful consideration in the design of optimization strategies. Despite these challenges, adaptive machine learning approaches are becoming a more regular part of a protein engineering pipeline.

Notable Design Task 2: Structure-Guided De Novo Protein Design

While adaptive machine learning techniques have been developed mainly to enhance existing proteins through iterative rounds of experimentation, structure-guided “de novo design” aims to create entirely new proteins using computational methods with structures that are substantially different from the structures of natural proteins (Chu, Lu, and Huang, 2024). The sophistication of de novo design has increased by replacing early approaches based on physical principles with recent advances in machine learning.

The modern protein design workflow often uses a two-step process. First, structure generation models like RFdiffusion (Watson et al., 2023) create protein backbones, allowing designers to specify constraints such as binding interfaces or symmetry. Then, inverse folding methods like ProteinMPNN (Dauparas et al., 2022) or ESM-IF1 (Hsu, Verkuil, et al., 2022) determine amino acid sequences likely to fold into the generated structures. Designs are typically evaluated using a “self-consistency” metric, which assesses whether a designed sequence is likely to fold into the intended structure under a structure prediction model like AlphaFold or ESMFold.

De novo protein design to engineer proteins with useful functions, in addition to novel structures, typically still uses parts of natural proteins that are involved in a specific function (e.g., an enzyme active site or a binding interface) but replaces other components of the protein with a nonnatural protein scaffold. These developments have enabled the creation of de novo proteins with complex functions, including enzymes, protein binders, and designed proteins that can form large assemblies or span cell membranes (Courbet et al., 2022; Wang et al., 2022; Watson et al., 2023).

While progress has been substantial, challenges remain, particularly in areas where fine control over chemical interactions and conformational dynamics is crucial. The field is moving toward more integrated approaches

that consider multiple states, dynamics, and the co-design of sequence and structure (Chu, Lu, and Huang, 2024). Future advancements likely will come from a combination of data-driven approaches and first-principles reasoning (e.g., directly incorporating biophysical principles or experimental data into protein design tools), potentially leading to greater versatility of de novo designed proteins.

Other Design Tasks

Machine learning–guided biological design has extended beyond proteins to other biological modalities, albeit to a more limited extent. One notable example is the work by Nguyen and colleagues, who developed a genomic language model, Evo, that learns sequence information underlying DNA, RNA, and proteins from raw genome sequences (Nguyen, Poli, Durrant, et al., 2024). This model enables the design of multimodal biological systems, including CRISPR-Cas systems (involving protein-RNA co-design) and transposon systems (focusing on protein-DNA co-design). Another notable area is machine learning–guided promoter design, which is often used in synthetic biology applications to control levels of gene expression in E. coli or to control cell-type-specific gene expression in mouse or human cells (LaFleur, Hossain, and Salis, 2022; Zhang et al., 2023; DaSilva et al., 2024; Reddy et al., 2024). The approach here parallels that of protein design: either a generative model produces promoter sequences, or a large collection of promoters is utilized as a starting point. These candidate promoters are then evaluated using a promoter activity prediction model. The designs are subsequently tested in the laboratory, with the results feeding back into the system to refine future predictions and designs. This iterative process allows for continuous improvement in the design of promoters with desired activities. As generative and predictive machine learning models improve, we can expect to see further integration of machine learning across various aspects of biological design, potentially leading to more efficient approaches to engineering biological systems.

BIOLOGICAL DATASETS

Biological datasets are crucial for training foundation models, as they provide the raw material from which these models learn complex patterns. When training foundation models by leveraging the scaling hypothesis, the scale, quality, and complexity of data are as important as the model size and the amount of compute used to train the model (Kaplan et al., 2020; Hoffmann et al., 2022). This review focuses on large-scale public datasets representing a diverse range of biological data types, including genetic sequence data (spanning proteins, RNA, DNA, and whole genomes),

molecular structures, molecular properties, epigenomic information, and transcriptomic data, which we also describe in Table A-3. We also summarize ways to link information across multiple modalities when training multimodal language models.

Genetic Sequence Datasets

Genome Sequence

Genomic sequencing data form the foundation for databases of proteins, RNAs, and regulatory DNA sequences. Most genome sequences are obtained through shotgun sequencing, where short DNA fragments are sequenced, quality-filtered, and assembled into longer contiguous sequences called contigs. These contigs can be derived from a single species’ genomic DNA (or RNA for some viruses) or from mixed species samples (metagenomic data) (Giani et al., 2020). Bioinformatic tools then identify potential genes, protein-coding sequences, and other functional elements, though annotation quality can vary by species (Yandell and Ence, 2012). The primary repositories for these genomic sequences and annotations are GenBank from the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) (Sayers et al., 2019) in the United States and the European Nucleotide Archive (ENA) from EMBL-EBI.2 Specialized databases often curate subsets of NCBI and ENA data and offer additional metadata. For instance, RefSeq is a high-quality subset of NCBI genome data with annotations (O’Leary et al., 2016); the Ensembl and EnsemblGenomes databases likewise curate ENA genomes along with annotations (Yates et al., 2022; Martin et al., 2023), while the Genome Taxonomy Database (GTDB) focuses on high-quality prokaryotic genomes (Parks et al., 2022). Specialized protein and RNA sequence databases also heavily leverage the annotated sequences in these larger genomic sequence databases. Metagenomics databases, which are often also deposited into NCBI or ENA, include the following: Unified Human Gastrointestinal Genome (UHGG) (Almeida et al., 2021), Joint Genome Institute Integrated Microbial Genomes (JGI IMG) (Markowitz et al., 2006), Human Gastrointestinal Bacteria Genome Collection (Forster et al., 2019), MGnify (Richardson et al., 2023), Youngblut and colleagues’ (2020) animal gut metagenomes, and the Tara Oceans Project (Pesant et al., 2015). Genomic sequence models often train on a much smaller subset of the terabytes of sequences found in these databases. Many genomic sequence models have only been applied to the human reference genome. Evo, a genomic language model trained on prokaryotic genomes, was mostly trained on GTDB.

___________________

2 See https://www.ebi.ac.uk/ena/ (accessed November 17, 2024).

TABLE A-3 Biological Databases

| Category | Database name | Type of data stored | Citation or URL |

|---|---|---|---|

| Genome sequence | GenBank | Genomic sequences and annotations | Sayers et al., 2019 |

| Genome sequence | European Nucleotide Archive (ENA) | Genomic sequences and annotations | https://www.ebi.ac.uk/ena/browser/home |

| Genome sequence | RefSeq | Genomic sequences and annotations | O’Leary et al., 2016 |

| Genome sequence | Ensembl | Genomic sequences and annotations | Martin et al., 2023 |

| Genome sequence | Ensembl Genomes | Genomic sequences and annotations | Yates et al., 2022 |

| Genome sequence | Genome Taxonomy Database (GTDB) | Prokaryotic genome sequences | Parks et al., 2022 |

| Genome sequence | Unified Human Gastrointestinal Genome (UHGG) | Metagenomic sequences | Almeida et al., 2021 |

| Genome sequence | JGI IMG | Microbial genome and metagenome sequences | Markowitz et al., 2006 |

| Genome sequence | Human Gastrointestinal Bacteria Genome Collection | Gut microbiome metagenomic sequences | Forster et al., 2019 |

| Genome sequence | MGnify | Metagenomic sequences | Richardson et al., 2023 |

| Genome sequence | Youngblut et al. | Animal gut metagenomic sequences | Youngblut et al., 2020 |

| Genome sequence | Tara Oceans Project | Marine metagenomic sequences | Pesant et al., 2015 |

| Protein sequence | UniProt | Protein sequences and annotations | UniProt Consortium, 2019 |

| Protein sequence | UniRef50/UniRef90 | Clustered protein sequences | Suzek et al., 2007 |

| Protein sequence | Pfam | Protein domain sequences and annotations | El-Gebali et al., 2019 |

| Protein sequence | Observed Antibody Space (OAS) | Antibody variable region sequences | Olsen, Boyles, and Deane, 2022 |

| Viral sequence | GISAID | Influenza and SARSCoV-2 sequences | Shu and McCauley, 2017 |

| Viral sequence | BV-BRC | Bacterial and viral sequences | Olson et al., 2023 |

| Category | Database name | Type of data stored | Citation or URL |

|---|---|---|---|

| Viral sequence | Influenza Research Database | Influenza virus sequences | Zhang et al., 2017 |

| Viral sequence | LANL HIV database | HIV sequences | Foley et al., 2018 |

| Noncoding RNA sequence | Rfam | RNA family sequences | Kalvari et al., 2021 |

| Noncoding RNA sequence | RNAcentral | Noncoding RNA sequences | Sweeney et al., 2019 |

| Biomolecular structure | Protein Data Bank (PDB) | 3D structures of biological macromolecules | Berman et al., 2000 |

| Biomolecular structure | CATH | Protein domain structures and classifications | Knudsen and Wiuf, 2010 |

| Biomolecular structure | CASP | Protein structure prediction targets | repasted https://predictioncenter.org/ |

| Biomolecular structure | AlphaFoldDB | Predicted protein structures | Varadi et al., 2022 |

| Biomolecular structure | ESM Metagenomic Atlas | Predicted metagenomic protein structures | Lin et al., 2023 |

| Protein function | ProteinGym | Protein mutational effect datasets | Notin et al., 2024 |

| Protein function | FLIP | Protein fitness landscape datasets | Dallago et al., 2021 |

| Protein function | ClinVar | Genetic disease variants and phenotypes | Landrum et al., 2018 |

| Protein function | SKEMPI | Protein-protein interaction affinity changes | Jankauskaitė et al., 2019 |

| Protein function | PDBbind | Biomolecular binding affinity data | Wang et al., 2005 |

| Protein function | BindingDB | Protein-small molecule interaction data | Liu et al., 2007 |

| Protein function | BRENDA | Enzyme and enzyme-ligand data | Chang et al., 2021 |

| Protein function | Binding MOAD | Protein-ligand binding data | Wagle et al., 2023 |

| Protein function | 2P2Idb | Protein-protein interactions targetable by small molecules | Basse et al., 2016 |

| Category | Database name | Type of data stored | Citation or URL |

|---|---|---|---|

| Protein function | ProThermDB | Protein stability data | Nikam et al., 2021 |

| Protein function | STITCH | Protein-chemical interactions | Szklarczyk et al., 2016 |

| Protein function | DrugBank | Drug-target interactions | Knox et al., 2011 |

| Protein function | Gene Ontology (GO) | Gene and protein function annotations | Aleksander et al., 2023 |

| Epigenomic datasets | ENCODE | Epigenomic data for human and mouse | ENCODE Project Consortium, 2012 |

| Epigenomic datasets | Roadmap Epigenomics Project | Human epigenomic data | Kundaje et al., 2015 |

| Epigenomic datasets | PsychENCODE | Brain epigenome data | Akbarian et al., 2015 |

| Epigenomic datasets | 4D Nucleome Project | 3D genome organization data | Dekker et al., 2017 |

| Epigenomic datasets | FANTOM | Transcription start sites and enhancers | Andersson et al., 2014 |

| Transcriptomic datasets | Human Cell Atlas (HCA) | Human single-cell transcriptomic data | Regev et al., 2017 |

| Transcriptomic datasets | Tabula Sapiens | Human single-cell transcriptomic data | Jones et al., 2022 |

| Transcriptomic datasets | Tabula Muris | Mouse single-cell transcriptomic data | The Tabula Muris Consortium, 2018 |

| Transcriptomic datasets | Fly Cell Atlas | Fruit fly single-cell transcriptomic data | Li et al., 2022 |

| Transcriptomic datasets | CELLxGENE | Aggregated single-cell data | CZI Single-Cell Biology Program et al., 2023 |

| Transcriptomic datasets | Broad Single Cell Portal | Aggregated single-cell data | https://singlecell.broadinstitute.org/single_cell |

NOTE: This table provides an overview of major biological databases related to biological model training, organized by category of biological data. It includes databases for genome sequences, protein sequences, coding and noncoding RNA sequences, biomolecular structures, protein functions, epigenomic data, and transcriptomic data. For each database, we provide a brief description of the type of data stored. Datasets of sufficient diversity and quality to train foundation models are highlighted in light blue.

TABLE A-4 Example Training Datasets and Associated Models

| Model | Model type | Training datasets |

|---|---|---|

| ESM-2 | Protein sequence model | UniRef90 |

| Evo | Genomic sequence model | GTDB, IMG/PR, IMG/VR |

| AlphaFold2 | Structure prediction model | PDB |

| ProGen2 | Protein sequence model | UniRef90, metagenomic sequences, Observed Antibody Space (OAS) |

| AbLang | Antibody protein sequence model | Observed Antibody Space (OAS) |

| CaLM | Codon sequence model | Coding sequences from European Nucleotide Archive (ENA) |

| RiNALMo | Noncoding RNA sequence model | Rfam, RNAcentral, NCBI |

| GenSLM | Genomic sequence model | GenBank |

| Enformer | Multi-omic prediction model | ENCODE datasets |

| scGPT | Transcriptomic count model | CELLxGENE |

NOTE: Example models and their corresponding training datasets. These datasets are typical for each of the types of models in the table. Some models draw from multiple publicly available data sources for training.

Protein Sequence

Protein sequence datasets are primarily sourced from UniProt (Universal Protein Resource), which is a high-quality database that includes many manually annotated and experimentally validated sequences (UniProt Consortium, 2019). UniRef50 and UniRef90 provide clustered versions of UniProt at 50 percent and 90 percent sequence identity thresholds, respectively, which removes redundant proteins to ensure that protein language models are trained on diverse sequences (Suzek et al., 2007). Another highly curated protein database is Pfam, which uses hidden Markov models to identify and classify recurring structural and functional units within proteins; all protein sequences in Pfam have an associated Pfam domain categorization (El-Gebali et al., 2019). Metagenomics databases such as MGnify (Richardson et al., 2023) and databases maintained by the Joint Genome Institute (JGI) (Markowitz et al., 2006) identify potential protein sequences from prokaryotic genomes by locating open reading frames, which are DNA sequences between start and stop codons that potentially encode proteins. While potentially lower quality than UniProt, metagenomic databases help to expand the known protein sequence space greatly. Antibody language models primarily make use of the Observed Antibody Space (OAS) dataset (Olsen, Boyles, and Deane, 2022), containing ~2 billion antibody variable domain sequences. Viral protein language models use protein sequences identified during viral surveillance (primarily directed at the highly mutable

pandemic viruses such as influenza A, HIV, and severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 [SARS-CoV-2]) and deposited into databases such as NCBI RefSeq (O’Leary et al., 2016), GISAID (Global Initiative on Sharing All Influenza Data) (Shu and McCauley, 2017), the Bacterial and Viral Bioinformatics Resource Center (BV-BRC) database (Olson et al., 2023), Influenza Research Database (Zhang et al., 2017), and the Los Alamos National Laboratory (LANL) HIV database (Foley et al., 2018).

Coding RNA Sequence

Codon language models are trained on coding sequences extracted from natural genomes, utilizing the coding sequence annotations found in NCBI or ENA databases. In prokaryotic genomes, these coding sequences are contiguous. However, in eukaryotic genomes, coding sequences are noncontiguous due to the presence of introns. Eukaryotic gene expression involves splicing, a process in which introns are removed and exons are joined to form the mature mRNA. Thus, eukaryotic coding sequence datasets require annotations specifying which genomic regions are retained in the final transcript. Notable codon language models include CaLM, which is trained on coding sequences from ENA, and CodonBERT, which utilizes coding sequences from NCBI (Outeiral and Deane, 2024; Ren et al., 2024).

Noncoding RNA Sequence

Several language models are specifically trained on ncRNA sequences. As with protein coding sequences, many ncRNA sequences are derived from annotated ncRNA data in GenBank and Ensembl, and eukaryotic ncRNA sequences must account for splicing. Additional ncRNA-specific databases include Rfam (Kalvari et al., 2021), which organizes ncRNA sequences into RNA families (analogous to Pfam for proteins), and RNAcentral (Sweeney et al., 2019), a comprehensive collection of ncRNAs that incorporates sequences from various sources, including GenBank and Ensembl.

Biomolecular Structure Datasets

Decades of experimental work in structural biology, resulting in large curated datasets of molecular structures, have been instrumental in driving the progress in biomolecular structure prediction represented by AlphaFold. The Protein Data Bank (PDB) serves as the primary repository for experimentally determined 3D structures of biological macromolecules, including proteins and nucleic acids (Berman et al., 2000). The structures in the PDB are primarily determined through experimental methods such as X-ray crystallography, nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy, and

cryo-EM. X-ray crystallography provides high-resolution structures by analyzing X-ray diffraction patterns from protein crystals. NMR spectroscopy determines structures in solution, offering insights into protein dynamics. Cryo-EM, which has seen significant recent advancements, images flash-frozen proteins using electron microscopy, allowing for the determination of large complex structures and conformational states.

Many additional datasets are built off of data that have been deposited in the PDB. CATH (Class, Architecture, Topology, Homology) offers a hierarchical classification of protein domains based on their 3D structures, organizing PDB entries into structurally related groups (Knudsen and Wiuf, 2010). CASP (Critical Assessment of protein Structure Prediction)3 is a biannual competition that assesses the state of the art in protein structure prediction method; as part of CASP, new protein structures are experimentally determined and used as a test set for structure prediction models. Both CATH and CASP are particularly valuable for developing machine learning models for structural biology, as they provide splits of protein structures based on structural similarity and, in the case of CASP data, temporally held-out data with respect to different versions of the PDB. Ensuring proper held-out structures during model development helps mitigate data leakage, a common issue in machine learning where information from the test set inadvertently influences the training process, leading to overly optimistic performance estimates. By using structural similarity-based splits, researchers can more accurately assess generalization capabilities to new protein folds.