The Age of AI in the Life Sciences: Benefits and Biosecurity Considerations (2025)

Chapter: Summary

Summary

Artificial intelligence1 (AI) applications in the life sciences have the potential to enable biological discovery and design at a much-accelerated pace and volume when combined with classical experimental approaches. AI models in biology are currently trained on existing biological datasets built from experimental data. For example, AlphaFold, which predicts protein structures from sequence data with significant accuracy, was developed and trained on experimentally derived structures of about 200,000 unique protein sequences in the publicly accessible database Protein Data Bank (PDB). The convergence of AI and biology is a relatively new and emerging area of research—particularly in large neural network models—that spans several disciplines and affects much of the research workflow from hypothesis generation to data analysis. Current AI applications in the life sciences and biomedical research include analysis of genomics and other -omics, synthetic biology,2 drug discovery, and healthcare delivery, among many others. The promise of these developments was recognized in 2024

___________________

1 Artificial intelligence refers to “a machine-based system that can, for a given set of human-defined objectives, make predictions, recommendations, or decisions influencing real or virtual environments.” See https://csrc.nist.gov/glossary/term/artificial_intelligence (accessed December 30, 2024).

2 Synthetic biology, also known as engineering biology, refers to “the intentional design, manufacture and deployment of living cells, cell systems, and other biological processes to create materials and products that benefit us, like crops that resist drought and pests, renewable energy sources, advanced medicines, and more.” See https://www.nist.gov/engineering-synthetic-biology (accessed December 30, 2024).

with the Nobel Prize for Chemistry for the development of computational protein design and protein structure prediction.

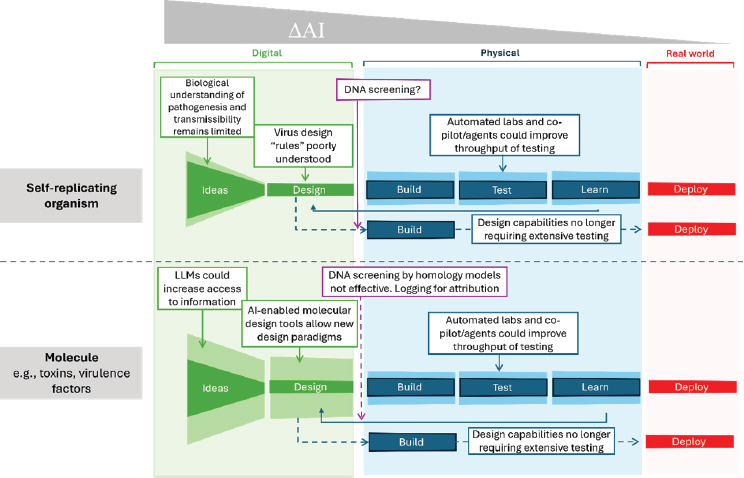

However, some concerns have been raised that AI-enabled biological tools trained on biological data and intended for beneficial applications may be misused for harmful applications, particularly by facilitating the design of transmissible biological agents that could pose an epidemic- or pandemic-scale threat. Questions regarding the impact of AI on biosecurity risks are highlighted in Executive Order 14110 on the Safe, Secure, and Trustworthy Development and Use of Artificial Intelligence. The creation of biological weapons is not a new concept or concern; however, whether AI-enabled biological tools could appreciably affect that risk is. The focus of the report is assessing how AI-enabled biological tools can uniquely enable biosecurity risks, or the capability uplift referred to as ∆AI and how AI in biology can be used to mitigate such biosecurity risks.

This report represents the outcome of a technical assessment by the committee of the capabilities of AI-enabled biological tools, which can be utilized in conjunction with the framework developed in the National Academies’ 2018 report Biodefense in the Age of Synthetic Biology (hereafter referred to as “the 2018 framework”) for a full consideration of the threat landscape and risk assessment. The 2018 framework comprehensively identified the different risk factors associated with synthetic biology capabilities but can be applied more broadly to other biotechnologies.

AI-ENABLED BIOLOGICAL DESIGN

Synthetic biology is typified by ideation followed by the process of Design-Build-Test-Learn (DBTL). The most significant capability uplift of AI-enabled biological tools, ∆AI, is in the ideation and design phases. AI-enabled biological tools can accelerate and optimize research design and discovery by providing data-driven guidance for experimental validation, generating novel hypotheses and ideas, and discovering patterns in large datasets. In addition, AI may facilitate data analysis and enhance insights gained from experimental data in the “Learn” phase of the DBTL cycle, subsequently enabling continuous refinement of the DBTL cycle and knowledge generation in a feedback loop. Importantly, AI-enabled design does not replace the need for experimental validation; rather, it enhances the process by combining in silico modeling with experimental approaches.

As previously mentioned, there is concern that AI-enabled biological tools could be misused to design transmissible biological agents with epidemic or pandemic potential. The committee explored DAI in the context of three harmful applications (see Figure S-1): (1) design of biomolecules, such as proteins and toxins; (2) modification of existing pathogens for increased virulence; and (3) de novo design of a virus. These three applications

NOTE: LLM = large language model.

exemplify both the biological nature of the problem and the capabilities of AI-enabled biological tools—ranging from simple to complex. The committee’s assessment of the DAI for each of the three applications is summarized below:

- Design of biomolecules, such as toxins. Available AI-enabled biological tools currently are capable of designing and redesigning toxins using different amino acid building blocks, but the scale of potential threats likely would be limited to the local level rather than elevated to an epidemic or pandemic level.

- Modification of existing pathogens for increased virulence. Available AI-enabled biologicals tools may be capable of modeling very specific features that may predict phenotypes related to virulence. However, certain limitations impact model performance, including insufficient datasets and the complex challenge of modeling networks of interactions and evolutionary pressures.

- De novo design of a virus. No available AI-enabled biological tool currently possesses the capability to design a virus de novo. Furthermore, no biological datasets that can be used to train such models are known to exist. However, developments that could lead to this capability would represent the most significant AI-enabled capability uplift risk of a potential epidemic- or pandemic-scale threat.

Importantly, AI-enabled biological tools do not necessarily reduce the bottlenecks and barriers to crossing the digital–physical divide (i.e., the physical production of AI-designed experiments or outputs). However, future improvements in automated laboratories may reduce the bottlenecks and barriers at the “Build” and “Test” phases of the DBTL cycle.

AI-ENABLED APPLICATIONS FOR BIOSECURITY

AI-enabled biological tools can improve biosecurity and mitigate biological threats by enhancing prediction, detection, prevention, and response. This includes improving biosurveillance and accelerating the development of medical countermeasures (e.g., vaccines, antibodies) in response to both intentional biological threats and naturally occurring infectious disease outbreaks. AI-driven acceleration of countermeasure design is especially critical in an emergency response to a biological threat. Research programs for understanding the biology of infectious agents are important to support the development of vaccines and therapeutics to prevent and treat diseases caused by biological agents, whether resulting from natural occurrences or intentional threats.

Recommendation 1-1: The U.S. Department of Defense, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA), U.S. Department of Energy, U.S. Department of Homeland Security, and other agencies that support and conduct research should continue to invest in vigorous research programs to understand the biology of infectious agents. As a part of these programs, agencies should also invest in and implement biosurveillance networks through the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and USDA in cooperation with public health agencies globally.

Recommendation 1-2: Entities within the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (e.g., National Institutes of Health, Biomedical Advanced Research and Development Authority, and Advanced Research Projects Agency for Health) and the U.S. Department of Defense (e.g., Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency and Chemical and Biological Defense) should fund approaches using AI-enabled design tools for application in medical countermeasure development, especially in the face of an epidemic, pandemic, or other biological threat.

Recommendation 1-3: As part of a national preparedness strategy, the Biomedical Advanced Research and Development Authority, U.S. Department of Energy, and U.S. Department of Defense should establish a public–private partnership, analogous to Operation Warp Speed and the COVID-19 High-Performance Computing Consortium, that can both leverage and provide access to AI-enabled tools and computational resources and be activated rapidly in an emergency response.

Associated biological datasets and insight from such research will be useful and necessary for training AI models to accelerate the development of such medical countermeasures, biosurveillance, and other biosecurity applications previously mentioned. A risk-benefit assessment may be useful to carefully balance the need to invest in critical research intended to protect against harm from biological agents with the potential for misuse of the information or tools by malicious actors with harmful intent.

Unlike in other domains where AI in the digital world can directly generate nefarious products that can immediately be used for harm (e.g., misinformation, deep fakes, discriminatory practices), the risk of AI-related biological threats materializes in the physical world only when biological agents are produced. Given the production requirement of any AI-enabled design of transmissible biological threats, nucleic acid synthesis screening has been recognized as an important checkpoint for actors that uses synthesis services. AI-enabled biological tools also may be used to screen and thereby prevent the creation of biological threats by augmenting current nucleic acid screening methods. However, this specific application of AI is an emerging area and thus needs more research and development.

Conclusion: More research in new methodologies for nucleic acid synthesis screening, including how to leverage AI-enabled biological tools for screening, is needed for this process to be an efficient control point and possible strategy to mitigate potential biosecurity risks. Engaging practitioners and developers of AI-enabled biological tools to explore the most effective approaches for implementation is important as is engaging biologists and other developers to assess impacts of screening on public health preparedness and response.

PROMOTING AND PROTECTING AI-ENABLED INNOVATION FOR BIOSECURITY: GUIDING PRINCIPLES FOR CONTINUOUS EVALUATIONS

New and rapidly developing capabilities in AI biological models and design tools provide vast opportunities for discovery, ideation, and design of biomolecules and biological agents that have useful purposes and applications in health, agriculture, industry, and beyond. In addition, AI applications to mitigate biosecurity risks are promising. However, AI-enabled biological tools and models also may be misused for harmful applications. Here, it is important to distinguish between capability and intent when considering the potential biosecurity risks to avoid unnecessarily restricting or hindering biological research and development. At present, AI-enabled biological tools have limitations (see Chapter 4), whether for beneficial or harmful applications. Namely, biological knowledge and datasets are scarce to train AI biological models for the purpose of designing a novel virus or bacterium or modifying an existing biological entity broadly. Physical production of such an entity is also a significant bottleneck and barrier.

The committee recommends the adoption of an “if-then” strategy to account for the dynamic and rapid pace of development of AI-enabled biological tools that may be improved with training data. The if-then strategy accounts for these dynamics without being prescriptive or restrictive based on predicting future capabilities. Amassing significant datasets, sometimes generated through compute-intensive simulations, is a prerequisite for training AI models (e.g., PDB for AlphaFold); therefore, the availability of high-quality, robust data can be the leading indicator of an emerging or developing AI capability.

The if-then approach allows for the continual assessment and periodic reassessment of vulnerabilities and risks using a principles-based thought framework. These evaluations should be anchored in both data availability and the associated emerging AI capabilities as well as real-world threat models that incorporate all four factors articulated in the NASEM 2018 framework (i.e., usability of the technology, usability as a weapon, requirement of actors, and potential for mitigation). In addition, the development of an if-then strategy should incorporate benchmarks and metrics to track data availability and associated capability progress as well as a set of thresholds that, once surpassed by emerging capabilities, activate risk assessment and mitigation.

Recommendation 2: The U.S. Department of Defense and the U.S. Artificial Intelligence (AI) Safety Institute should develop an “if-then” strategy to evaluate continuously both the availability and quality of data and emerging AI-enabled capabilities to anticipate changes in the

risk landscape (e.g., if dataset “x” is collected, then monitor for the emergence of capability “y”; if capability “y” is developed, then watch for output “z”). Evaluation of AI-enabled biological tool capabilities may be conducted in a sandbox environment.

- Example datasets of interest:

- If clear associations between viral sequences and virulence parameters become known, then evaluate the capability of AI models to predict or design pathogenicity and/or virulence.

- If robust viral phylogenomic sequence datasets linked to epidemiological data become available, then assess for the development of new AI models of transmissibility that could be used to design new threats.

- Example AI models that warrant assessment:

- If AI models are developed that infer mechanisms of pathogenicity and transmissibility from pathogen sequencing data, then watch for attempts to modify existing pathogens to increase their virulence or transmissibility.

- If AI models are developed that could predictably generate a novel replication-competent virus, then assess risk for bioweapon development.

OPTIMIZING DATA RESOURCES AND INFRASTRUCTURE

Biological data are the leading indicators of the emergence of new AI applications in the life sciences. However, with the notable exception of nucleic acid sequences and structural data, data in the life sciences are fragmented, and robust, reliable, and well-curated data that are amenable to model training are scarce. Both top-down generation of high-quality datasets and bottom-up aggregation of diverse and smaller datasets alongside tools for data harmonization are valid approaches to address the paucity of biological data.

In addition, standardized contextual information is critical for data reuse. For example, the PDB is a valuable resource that provided the foundation for AlphaFold because it is standardized, curated, and available to the public. Lack of data aggregation hinders research and development, especially in the training of new AI-enabled biological models and capabilities. The generation, curation, and preservation of a data repository requires significant long-term investments in laboratory and computing infrastructure capacity as well as subject matter expertise. Building new national data resources and the strategic collection of AI-ready biological datasets should be a national research priority for the United States to maintain scientific competitiveness and innovation.

Recommendation 3-1: To maximize the benefits of artificial intelligence (AI) in biology, U.S. federal research funding agencies such as the National Institutes of Health, Advanced Research Projects Agency for Health, Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency, National Science Foundation, U.S. Department of Energy, and others should fund efforts and infrastructures to do the following:

- Create and steward AI-compatible data and training sets for biological applications that are made publicly available;

- Initiate and support public–private partnerships for the generation of training datasets; and

- Develop frontier AI-enabled biological tools that are specifically trained on biological data and focused on biological capabilities.

Recommendation 3-2: Federal research agencies that house or fund biological databases should consider these to be strategic assets and concordantly implement robust data provenance mechanisms to maintain the highest data quality. They should provide strong incentives and infrastructure for the standardization, curation, integration, and continuous maintenance of high-quality, publicly accessible biological data at scale.

Recommendation 3-3: While a public–private partnership is a reasonable approach to pilot the creation of an artificial intelligence (AI)–ready data resource on government-owned infrastructure, a dedicated organization is central to a sustainable national data stewardship resource. The National Artificial Intelligence Research Resource (NAIRR) pilot should explore approaches for establishing central repositories for training AI models.