The Age of AI in the Life Sciences: Benefits and Biosecurity Considerations (2025)

Chapter: 3 AI-Enabled Biological Design and the Risks of Synthetic Biology

3

AI-Enabled Biological Design and the Risks of Synthetic Biology

Artificial intelligence (AI) integration in the biological sciences is a relatively nascent area of research that creates a complex landscape for risk assessment. To date, there is a distinct lack of empirical data and research studies focused on evaluating the potential biosecurity risks of AI-enabled biological tools. Most risk assessments and subsequent critiques of studies at the interface of AI and biology have focused on general chatbots (Soice et al., 2023; Mouton, Lucas, and Guest, 2024; Patwardhan et al., 2024) and are outside the scope of this study. Urbina and colleagues (2022) published a study reporting the use of a predictive machine learning model to generate de novo chemicals predicted to be toxic. However, as will be discussed in this chapter, designing transmissible biological agents is more complicated than designing toxic biochemical molecules using current AI predictive models. This chapter will explore the complexities of biological design and engineering and subsequent biosecurity risk implications, focusing on the current capabilities of AI-enabled biological tools combined with scientific understanding of the biology. Although this report does not represent a formal risk assessment, which requires a broader assessment beyond technical capability to include intent and other factors, the 2018 framework (NASEM, 2018) may be utilized to consider the biosecurity risks in context of a given capability.

ADDRESSING BIOLOGICAL COMPLEXITY IN DESIGN AND ENGINEERING

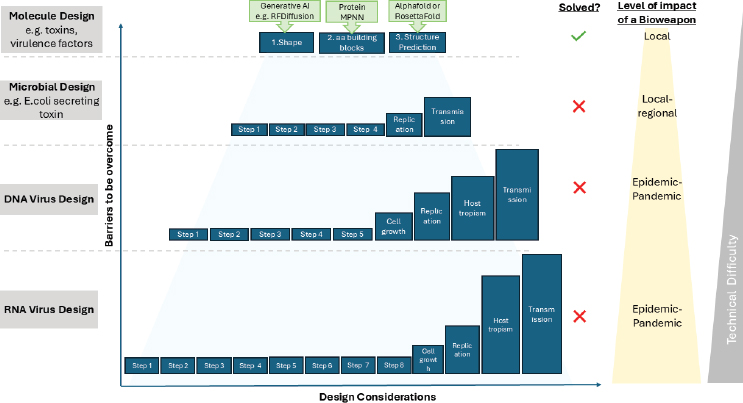

The committee examined the following three representative problems in biological design and engineering in consideration of the concern stated in the

statement of task—transmissible biological threats that could pose significant epidemic- and pandemic-scale consequences: (1) design of biomolecules, such as proteins and toxins; (2) modification of existing pathogens for increased virulence; and (3) de novo design of a virus.

AI-Enabled Design of Biomolecules

Current AI-enabled biological tools are capable of various modeling tasks, such as design and prediction with biological applications. For example, RoseTTAFold (Baek et al., 2021) and AlphaFold (Jumper et al., 2021) are accurate predictive protein models trained on structures in the Protein Data Bank (PDB). RFdiffusion is a generative model that can generate or design novel proteins by combining structure prediction from RoseTTAFold with a diffusion model (Watson et al., 2023). Recently developed generative AI–based approaches (see Appendix A) perform more sophisticated tasks, such as designing entirely new molecules with new functions and specificities to a specific ligand (Bennett et al., 2023; Vázquez Torres et al., 2024). How can these capabilities be misused for harmful applications?

One possibility is to redesign known toxins using different amino acid building blocks and, in so doing, potentially bypass simple homology-based DNA screening (Ekins et al., 2023; Baker and Church, 2024; Whitmann et al., 2024). For example, ProteinMPNN can be utilized in protein design to assign amino acid building blocks to create a specific structure. Importantly, ProteinMPNN (Daupras et al., 2022) can be used not only when building new molecules but also when redesigning an existing molecule to maintain the same structure with different amino acids. This capability can be used to generate a structurally similar molecule with limited sequence homology to the parent (Sumida et al., 2024) and may bypass typical homology-based DNA screening methodologies.

Likewise, intrinsically disordered proteins (IDPs) comprise 30–50 percent of proteomes and perform multiple essential functions in cells as well as play key roles in disease. These proteins do not form stable conformations and are refractile to traditional protein folding tools. Prions, which are proteins whose misfolding leads to accumulation of abnormal protein in the central nervous system, are IDPs that in specific conformations are able to self-template and “replicate.” AI-enabled prediction tools are beginning to decipher these conformational transitions (Erdős and Dosztányi, 2024). While it is theoretically possible that, as with toxin simulants above, a prion simulant could be created using IDP analytical tools, wet-lab testing is still necessary to assess the functionality of the designed protein or molecule.

Furthermore, limitations with current tools, such as fine-grained control (i.e., generating outputs that satisfy desired requirements), remain for any AI-enabled biological design. For AI-designed small molecules, a useful

molecule must be synthetically accessible, able to permeate specific physical barriers, and interact with specific intended molecules in the cell (and potentially no others). The current AI-enabled design methodologies focus on satisfying one or more phenotypical properties. The ability to satisfy an arbitrary number of chemical and phenotypical constraints remains an outstanding challenge in generative AI models. Similarly, controllable generation task challenges manifest themselves in macromolecular protein design. For instance, we are currently able to control for structure, but AI models cannot fully capture dynamics at disparate spatiotemporal scales and the full equilibrium conformational ensemble expected of a designed molecule in the cell. While not insurmountable, these are key challenges in the future capabilities of AI biological models. Quantum computing platforms may help address some of these challenges in the future.

The capabilities and limitations of current Al-enabled biological tools for protein design demonstrate the numerous factors that must be accounted for in designing a protein, a relatively simple biological problem. These variables significantly increase when the objective is to design complex biological systems that replicate, such as a bacterium or virus (see Figure 3-1).

AI-Enabled Design of Self-Replicating Agents with Epidemic or Pandemic Potential

The potential use of AI-enabled biological tools to design self-replicating and transmissible biological agents that do not already exist or are modified in some manner to be rendered more dangerous is challenging at every phase—from design to build and test. Specifically, to design new viral pathogens, generative AI models need to predict structural, virulence, and transmissibility determinants of a virus accurately, as discussed below. The de novo design of a virus would represent a significant capability uplift enabled by AI biological tools. Furthermore, this capability could have the highest impact in terms of consequences, as the potential for mitigation would be hampered and relatively delayed absent of information. However, it is unlikely that currently available viral sequence data are sufficient to train such a model, which would require not just sequence data but also the knowledge of sequences that are linked to specific phenotypes. Furthermore, virulence and transmissibility phenotypes are often associated with multiple molecular determinants, along with host interaction components, and therefore require an understanding of multiple network interactions (Eisfeld et al., 2024; Waters, 2024). Human viruses have had hundreds of thousands of years to evolve these traits, which are often best suited for a particular host with which the virus co-evolved or closely related organisms. In addition, viruses with RNA genomes are already functioning near their limit in terms

of mutational tolerance, meaning that most changes are likely to affect viral fitness (Goldhill et al., 2018; Li et al., 2023).

Modification of Existing Organisms

AI biological models have demonstrated promise in predicting phenotypes from genotypic, proteomic, and other types of molecular data but have several limitations at present. It should be noted that several existing non-AI-based models and methodologies can be used to predict individual characteristics of pathogens, such as transmission rates and antibody escape (Wagh et al., 2023; Dadonaite et al., 2024; May and Rannala, 2024; Meijers et al., 2024). Appendix A includes a brief overview of AI biological models that predict phenotypes of viruses (see Box 3-1). The unique capability uplift (DAI) of utilizing AI-based methods stems from the predictive modeling that in turn may provide guidance for experimental validation that can be further refined.

Understanding the molecular determinants of fitness characteristics of pathogens is important for developing vaccines, medical countermeasures,

and other public health responses, as noted in the referenced studies and discussed in more detail in Chapter 4. However, can AI-enabled biological tools be misused to modify existing pathogens by designing a single or a few specific changes to viral or bacterial sequences to increase virulence? The committee notes several key limitations of current AI-enabled biological tools in this regard and also for designing novel pathogens. These include limitations in the performance and capabilities of current models, while a second type of limitation involves the downstream processes of building, testing, and production. For accuracy in modeling, existing datasets that can be used to train the models are limited and noisy. Many datasets lack the coverage to capture the full range of molecular data influencing phenotypes. Biological datasets are not all standardized, often contain errors, and may contain biases that will affect model performance. Biological systems are also complex, and phenotypes result from intricate interactions at the molecular level, between environmental factors and host-pathogen interactions, and under evolutionary pressures that are difficult to model accurately. Phenotypes can change over time, requiring dynamic modeling

that current models and tools are not yet capable of with great accuracy. Finally, regardless of the capabilities of AI models, the production of a bioweapon requires experimental validation, which is resource-intensive and therefore remains an outstanding bottleneck. The bottleneck in physical production is not affected by the capabilities of AI biological models.

The chaotic nature of viral evolution also challenges accurate prediction of the intended results of virus design, including modification. The “butterfly effect” (Lorenz, 1972) is a chaos theoretical term defined as “the sensitive dependence on initial conditions in which a small change in one state of a deterministic nonlinear system can result in large differences in a later state.”1 In public parlance, the butterfly effect refers to the possibility that a butterfly flapping its wings could theoretically lead to a tornado but that the time and place of the tornado formation would be unpredictable mathematically due to the vast number of variables that would have to be taken into consideration. Chaos theory (Hasselblatt and Katok, 2003) is related to Stephen Wolfram’s concept of “computational irreducibility,” which postulates that many systems in nature are so complex that the system’s future state cannot be predicted without simulating each step in the process. Although both chaos theory and computation irreducibility are typically applied to physics, both concepts clearly should be taken into consideration when contemplating evolutionary pathways (Bennett, 2010; Rego-Costa, Débarre, and Chevin, 2018; Hoggard, 2024). In other words, it is possible that the various evolutionary pressures on pathogens, and, by extrapolation, even more so the evolution of newly created viruses, remain unpredictable even with the best AI tools and the fastest super computers.

Understanding Data Limitations in Viral Design

The lack of relevant and well-curated data is currently a limiting factor to training AI biological models that allow the design of novel pathogens with epidemic or pandemic potential. However, collecting large-scale data on virulence, pathogenicity, immune evasion, and other properties of viruses to use for training models is challenging. By comparison, protein folding models such as AlphaFold were trained on several hundred thousand experimentally determined protein structures, the vast majority of which were contributed over decades by individual research laboratories. This was possible in large part because the genotype-to-phenotype relationship is measurable: the three-dimensional structure of the protein is the phenotype itself, and scientists have been studying protein structure for decades. In addition to the lack of data, the quality of existing datasets may not be suitable for training accurate AI models (see Box 3-2).

___________________

1 See https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Butterfly_effect (accessed October 20, 2024)

The COVID-19 pandemic drove an unprecedented collection of high-quality sequences of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARSCoV-2) genomes as the global research and public health communities tracked the spread of new variants. To date, the GISAID (Global Initiative on Sharing All Influenza Data) repository, which began as an influenza virus resource but expanded to include SARS-CoV-2 during the pandemic, has more than 15 million deposited SARS-CoV-2 variant sequences.2 If these sequence data were paired with comprehensive phenotypic data, such as evasion of neutralizing antibodies raised against vaccine sequences, these data could be used to design sequences that enhance immune evasion. However, these types of phenotypic data have only been collected for a small fraction of the sequenced SARS-CoV-2 genomes, making the training of an immune evasion model difficult. Yet, the sheer number of SARSCoV-2 genome sequences available, even without phenotypic data, does

___________________

2 See https://gisaid.org/lineage-comparison/ (accessed October 14, 2024).

offer insight into the evolutionary space that has been effectively explored over the course of the pandemic. As a comparison, vaccine researchers who engineer prefusion stabilized spike proteins for SARS-CoV-2 report that AI has sped up their design process but that high-throughput screening and testing remains essential to their process.3

Another example is the family of replication-incompetent adeno-associated viruses (AAVs), one of the few groups of viruses with datasets linking viral sequences to human cell types infected (i.e., tropism) (Wang et al., 2024). These datasets have enabled AAVs to be engineered to deliver gene therapies, including Food and Drug Administration–approved treatments for hemophilia A (FDA, 2023) and neuromuscular diseases in children (FDA, 2019, 2024). However, even with the comparatively large amounts of data, predictively altering the tropism of AAVs remains challenging. Currently, the state of the art in AI-assisted AAV design depends on the use of AI to generate diverse libraries of AAV designs followed by successive design-build-test cycles to narrow the libraries down to functional sequences (Bryant et al., 2021; Ghauri and Ou, 2023). In other words, zero- or one-shot design of retargeted AAVs remains beyond the state of the art.

Conversely, attempting to design replication-competent viruses in a bottom-up fashion using protein design models is far beyond the capabilities of existing tools. For example, the authors of AlphaFold3 report that current protein design models are still poor predictors of protein dynamics (e.g., different conformational states), stemming from the fact that state-of-the-art protein design models use mainly static protein structure data from sources such as PDB (Abramson et al., 2024). See Appendix A for a more detailed discussion on the types of data that at scale may be used to develop new AI models for biology.

Finally, beyond the challenges associated with the design or modification of viruses, there are challenges associated with the physical production of any digital outputs to test and subsequently deploy, as discussed in the following sections.

IMPLICATIONS FOR BIOSECURITY

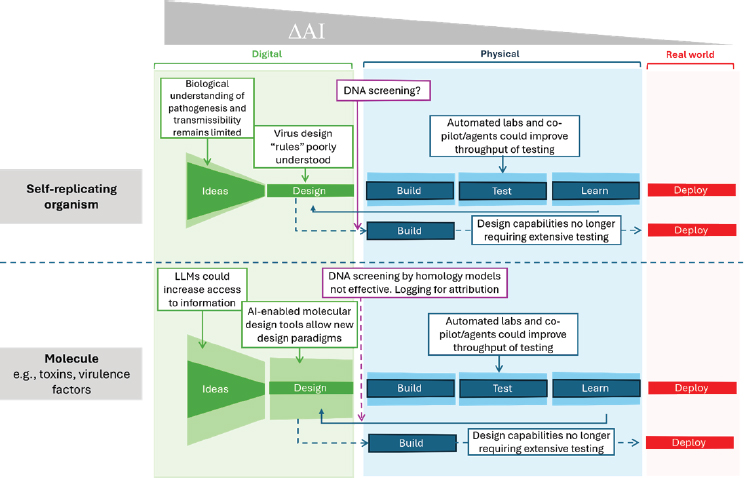

In assessing the impact of AI-enabled biological tools on lowering barriers or eliminating bottlenecks to creating or modifying existing pathogens, the committee considered how the capabilities made possible by these tools change the specific aspects of the Design-Build-Test-Learn (DBTL) cycle for a given threat. Presently, AI-enabled biological tools can facilitate the design of simple biomolecules. This capability has the potential to be

___________________

3 Presentation to the committee by Jason McLellan and Emanuele Andreano, October 1, 2024. See Appendix B.

exploited for harmful applications such as the redesign of toxins. However, this capability does not remove the need for building and testing that requires an extensive footprint. In contrast, current AI-enabled biological tools are not capable of the de novo design of a self-replicating organism such as a virus. Figure 3-2 summarizes the current capabilities and limitations of AI-enabled biological tools with respect to biological design complexity.

Overall, AI-enabled biological tools provide data-driven guidance to filter and select designs that reduce the amount of wet-lab testing and iterations to a potentially manageable number. The ultimate application of AI-enabled biological design would be to obviate the need for DBTL

NOTE: LLM = large language model.

altogether, so called zero-shot (de novo design without a preexisting example of a design to work from) or one-shot (design from a single reference design) learning. Significant capability uplift of AI-enabled biological tools that may be concerning and should be monitored include the following: (1) models able to predict transmissibility and pathogenesis with high accuracy, (2) AI-enabled design of fully replicating infectious agents, (3) design of models for molecules or pathogens that no longer require minimal wet-lab testing, or (4) improved AI-driven automated laboratories.

Conclusion: The relative lack of biological and mechanistic understanding about virulent phenotypes and the paucity of high-fidelity biological data mean that AI-enabled biological tools currently cannot be used to de novo design and subsequently build complex biological systems that can successfully replicate as transmissible biological agents with epidemic or pandemic potential.

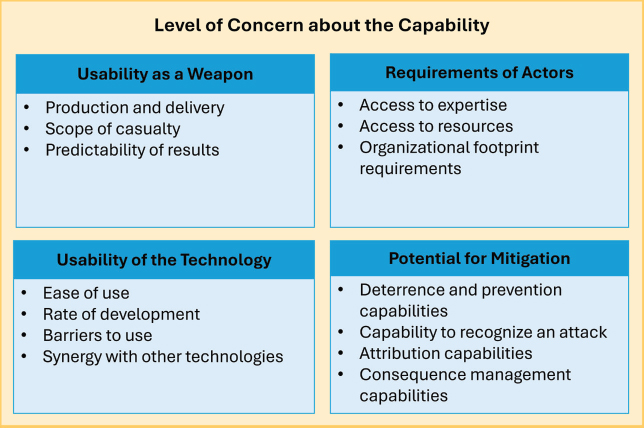

BROADER CONTEXT FOR ASSESSING BIOSECURITY RISKS: THE 2018 FRAMEWORK

In assessing biosecurity risks, intent cannot be separated from capability. While this report provides an analysis of the technical capabilities of AI-enabled biological tools that may be misused for harmful applications, the committee acknowledges the broader context of the risk landscape that can be assessed using the 2018 framework developed in the report Biodefense in the Age of Synthetic Biology (NASEM, 2018).

The framework allows various aspects of the threat development and use process to be considered, such that an analyst can properly weigh how technical advances may change one part of the process, for example, but leave others unchanged. The framework involves the analysis of four main attributes as they relate to the development and use of a synthetic biology–generated threat:

- Usability of the technology,

- Usability as a weapon,

- Requirements of actors, and

- Potential for mitigation.

Each of these categories was further divided into a series of subcategories, as shown below (see Figure 3-3).

SOURCE: Adapted from NASEM (2018).

As shown above, the framework considers the requirement of actors with intent to deploy a biological agent in an attack, including access to resources and expertise. Malicious actors may range from an individual to a state-sponsored bioweapons program (see Box 3-3). With respect to current AI-enabled biological tools, some degree of expertise is required to be able to exploit them for harmful applications. In looking toward the future, the committee considered the possibility of the development of AI agents that would lower the tacit knowledge required for an actor with malicious intent (see Box 3-4).

Finally, weaponization of the transmissible biological agent is necessary, or the usability as a weapon, as described in the 2018 framework, which accounts for the “implications for production and delivery of a weapon, expected scope of casualty, and the predictability of the intended results” (NASEM, 2018, p. 27).

Large-scale virus production, weaponization, dispersal, and dissemination are primarily informed through biotechnological, engineering, or meteorological knowledge and largely unencumbered by classical biological challenges or dependent on biological datasets. The committee acknowledges that nonbiological AI tools may accelerate development and evaluation for weaponization and dissemination by predicting ideal meteorological or environmental conditions for dispersal or tracking population movement, but these aspects are beyond the scope of this report. However, the fundamental problems associated with biological weapons production and delivery have not changed in recent years (Roffey, Tegnell, and Elgh, 2002; Guillemin, 2006).

REFERENCES

Abramson, J., J. Adler, J. Dunger, R. Evans, T. Green, A. Pritzel, O. Ronneberger, L. Willmore, A. J. Ballard, J. Bambrick, S. W. Bodenstein, D. A. Evans, C. C. Hung, M. O’Neill, D. Reiman, K. Tunyasuvunakool, Z. Wu, A. Žemgulytė, E. Arvaniti, C. Beattie, O. Bertolli, A. Bridgland, A. Cherepanov, M. Congreve, A. I. Cowen-Rivers, A. Cowie, M. Figurnov, F. B. Fuchs, H. Gladman, R. Jain, Y. A. Khan, C. M. R. Low, K. Perlin, A. Potapenko, P. Savy, S. Singh, A. Stecula, A. Thillaisundaram, C. Tong, S. Yakneen, E. D. Zhong, M. Zielinski, A. Žídek, V. Bapst, P. Kohli, M. Jaderberg, D. Hassabis, and J. M. Jumper. 2024. “Accurate structure prediction of biomolecular interactions with AlphaFold 3.” Nature 630 (8016):493–500. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-024-07487-w.

Adriaenssens, E. M., S. Roux, J. R. Brister, I. Karsch-Mizrachi, J. H. Kuhn, A. Varsani, T. Yigang, A. Reyes, C. Lood, E. J. Lefkowitz, M. B. Sullivan, R. A. Edwards, P. Simmonds, L. Rubino, S. Sabanadzovic, M. Krupovic, and B. E. Dutilh. 2023. “Guidelines for public database submission of uncultivated virus genome sequences for taxonomic classification.” Nature Biotechnology 41 (7):898-902. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41587-023-01844-2.

Baek, M., F. DiMaio, I. Anishchenko, J. Dauparas, S. Ovchinnikov, G. R. Lee, J. Wang, Q. Cong, L. N. Kinch, R. D. Schaeffer, C. Millán, H. Park, C. Adams, C. R. Glassman, A. DeGiovanni, J. H. Pereira, A. V. Rodrigues, A. A. van Dijk, A. C. Ebrecht, D. J. Opperman, T. Sagmeister, C. Buhlheller, T. Pavkov-Keller, M. K. Rathinaswamy, U. Dalwadi, C. K. Yip, J. E. Burke, K. C. Garcia, N. V. Grishin, P. D. Adams, R. J. Read, and D. Baker. 2021. “Accurate prediction of protein structures and interactions using a three-track neural network.” Science 373 (6557):871–876. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.abj8754.

Baker, D., and G. Church. 2024. “Protein design meets biosecurity.” Science 383 (6681):349. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.ado1671.

Beguir, K., M. J. Skwark, Y. Fu, T. Pierrot, N. L. Carranza, A. Laterre, I. Kadri, A. Korched, A. U. Lowegard, B. G. Lui, B. Sänger, Y. Liu, A. Poran, A. Muik, and U. Şahin. 2023. “Early computational detection of potential high-risk SARS-CoV-2 variants.” Computers in Biology and Medicine 155:106618. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compbiomed.2023.106618.

Bennett, K. 2010. “The chaos theory of evolution.” NewScientist. https://www.newscientist.com/article/mg20827821-000-the-chaos-theory-of-evolution/ (accessed October 8, 2024).

Bennett, N. R., B. Coventry, I. Goreshnik, B. Huang, A. Allen, D. Vafeados, Y. P. Peng, J. Dauparas, M. Baek, L. Stewart, F. DiMaio, S. De Munck, S. N. Savvides, and D. Baker. 2023. “Improving de novo protein binder design with deep learning.” Nature Communications 14 (1):2625. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-023-38328-5.

Bryant, D. H., A. Bashir, S. Sinai, N. K. Jain, P. J. Ogden, P. F. Riley, G. M. Church, L. J. Colwell, and E. D. Kelsic. 2021. “Deep diversification of an AAV capsid protein by machine learning.” Nature Biotechnology 39 (6):691–696. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41587-020-00793-4.

Dadonaite, B., J. J. Ahn, J. T. Ort, J. Yu, C. Furey, A. Dosey, W. W. Hannon, A. L. Vincent Baker, R. J. Webby, N. P. King, Y. Liu, S. E. Hensley, T. P. Peacock, L. H. Moncla, and J. D. Bloom. 2024. “Deep mutational scanning of H5 hemagglutinin to inform influenza virus surveillance.” PLOS Biology 22 (11):e3002916. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pbio.3002916.

Dauparas, J., I. Anishchenko, N. Bennett, H. Bai, R. J. Ragotte, L. F. Milles, B. I. M. Wicky, A. Courbet, R. J. de Haas, N. Bethel, P. J. Y. Leung, T. F. Huddy, S. Pellock, D. Tischer, F. Chan, B. Koepnick, H. Nguyen, A. Kang, B. Sankaran, A. K. Bera, N. P. King, and D. Baker. 2022. “Robust deep learning-based protein sequence design using ProteinMPNN.” Science 378 (6615):49–56. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.add2187.

Eisfeld, A. J., L. N. Anderson, S. Fan, K. B. Walters, P. J. Halfmann, D. Westhoff Smith, L. B. Thackray, Q. Tan, A. C. Sims, V. D. Menachery, A. Schäfer, T. P. Sheahan, A. S. Cockrell, K. G. Stratton, B.-J. M. Webb-Robertson, J. E. Kyle, K. E. Burnum-Johnson, Y.-M. Kim, C. D. Nicora, Z. Peralta, A. U. N’jai, F. Sahr, H. van Bakel, M. S. Diamond, R. S. Baric, T. O. Metz, R. D. Smith, Y. Kawaoka, and K. M. Waters. 2024. “A compendium of multi-omics data illuminating host responses to lethal human virus infections.” Scientific Data 11 (1):328. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-024-03124-3.

Ekins, S., M. Brackmann, C. Invernizzi, and F. Lentzos. 2023. “Generative artificial intelligence-assisted protein design must consider repurposing potential.” GEN Biotechnology 2 (4):296–300. https://doi.org/10.1089/genbio.2023.0025.

Erdős, G., and Z. Dosztányi. 2024. “Deep learning for intrinsically disordered proteins: From improved predictions to deciphering conformational ensembles.” Current Opinion in Structural Biology 89:102950. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbi.2024.102950.

FDA (Food and Drug Administration). 2019. “FDA approves innovative gene therapy to treat pediatric patients with spinal muscular atrophy, a rare disease and leading genetic cause of infant mortality.” Last Modified May 24, 2019. https://www.fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/fda-approves-innovative-gene-therapy-treat-pediatric-patients-spinal-muscular-atrophy-rare-disease (accessed November 8, 2024).

FDA. 2023. “FDA approves first gene therapy for adults with severe hemophilia A.” Last Modified June 30, 2023. https://www.fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/fda-approves-first-gene-therapy-adults-severe-hemophilia (accessed November 8, 2024).

FDA. 2024. “FDA expands approval of gene therapy for patients with Duchenne muscular dystrophy.” Last Modified June 20, 2024. https://www.fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/fda-expands-approval-gene-therapy-patients-duchenne-muscular-dystrophy (accessed November 8, 2024).

Gao, S., A. Fang, Y. Huang, V. Giunchiglia, A. Noori, J. R. Schwarz, Y. Ektefaie, J. Kondic, and M. Zitnik. 2024. “Empowering biomedical discovery with AI agents.” arXiv. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2404.02831.

Ghauri, M. S., and L. Ou. 2023. “AAV engineering for improving tropism to the central nervous system.” Biology 12 (2):186. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology12020186.

Goldhill, D. H., A. J. W. Te Velthuis, R. A. Fletcher, P. Langat, M. Zambon, A. Lackenby, and W. S. Barclay. 2018. “The mechanism of resistance to favipiravir in influenza.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences USA 115 (45):11613–11618. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1811345115.

Guillemin, J. 2006. “Scientists and the history of biological weapons.” EMBO Reports 7 (S1):S45–S49. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.embor.7400689.

Haddox, H. K., A. S. Dingens, and J. D. Bloom. 2016. “Experimental estimation of the effects of all amino-acid mutations to HIV’s envelope protein on viral replication in cell culture.” PLOS Pathogens 12:e1006114. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.ppat.1006114.

Haddox, H. K., A. S. Dingens, S. K. Hilton, J. Overbaugh, and J. D. Bloom. 2018. “Mapping mutational effects along the evolutionary landscape of HIV envelope.” eLife 7:e34420. https://doi.org/10.7554/eLife.34420.

Hasselblatt, B., and A. Katok. 2003. A First Course in Dynamics: With a Panorama of Recent Developments. Cambridge, MA: Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511998188.

Hie, B., E. Zhong, B. Berger, and B. Bryson. 2021. “Learning the language of viral evolution and escape.” Science 371:284–288. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.abd7331.

Hie, B. L., K. K. Yang, and P. S. Kim. 2022. “Evolutionary velocity with protein language models predicts evolutionary dynamics of diverse proteins.” Cell Systems 13 (4):274–285. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cels.2022.01.003.

Hoggard, N. 2024. “How chaos theory brings order to the evolution of intelligence.” Journal of Big History 7 (2):43–65. https://doi.org/10.22339/jbh.v7i2.7205.

International Security Advisory Board. 2024. Report on biotechnology in the People’s Republic of China’s military-civil fusion strategy. Department of State. https://www.state.gov/wp-content/uploads/2024/11/ISAB-Report-on-Biotechnology-in-the-PRC-MCF-Strategy_Final.pdf. (accessed January 6, 2025)

Ito, J., A. Strange, W. Liu, G. Joas, S. Lytras, and K. Sato. 2024. “A protein language model for exploring viral fitness landscapes.” bioRxiv. https://doi.org/10.1101/2024.03.15.584819.

Jumper, J., R. Evans, A. Pritzel, T. Green, M. Figurnov, O. Ronneberger, K. Tunyasuvunakool, R. Bates, A. Žídek, A. Potapenko, A. Bridgland, C. Meyer, S. A. A. Kohl, A. J. Ballard, A. Cowie, B. Romera-Paredes, S. Nikolov, R. Jain, J. Adler, T. Back, S. Petersen, D. Reiman, E. Clancy, M. Zielinski, M. Steinegger, M. Pacholska, T. Berghammer, S. Bodenstein, D. Silver, O. Vinyals, A. W. Senior, K. Kavukcuoglu, P. Kohli, and D. Hassabis. 2021. “Highly accurate protein structure prediction with AlphaFold.” Nature 596 (7873):583–589. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-021-03819-2.

Lamb, K. D., J. Hughes, S. Lytras, O. Koci, F. Young, J. Grove, K. Yuan, and D. L. Robertson. 2024. “From a single sequence to evolutionary trajectories: Protein language models capture the evolutionary potential of SARS-CoV-2 protein sequences.” bioRxiv. https://doi.org/10.1101/2024.07.05.602129.

Lee, J. M., J. Huddleston, M. B. Doud, K. A. Hooper, N. C. Wu, T. Bedford, and J. D. Bloom. 2018. “Deep mutational scanning of hemagglutinin helps predict evolutionary fates of human H3N2 influenza variants.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences USA 115 (35):E8276–E8285. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1806133115.

Li, Y., S. Arcos, K. R. Sabsay, A. J. W. Te Velthuis, and A. S. Lauring. 2023. “Deep mutational scanning reveals the functional constraints and evolutionary potential of the influenza A virus PB1 protein.” Journal of Virology 97 (11):e0132923. https://doi.org/10.1128/jvi.01329-23.

Liu, X., J. Kong, Y. Shan, Z. Yang, J. Miao, Y. Pan, T. Luo, Z. Shi, Y. Wang, Q. Gou, C. Yang, C. Li, S. Li, X. Zhang, Y. Sun, E. C. Holmes, D. Guo, and M. Shi. 2024. “SegFinder: An automated tool for identifying RNA virus genome segments through co-occurrence in multiple sequenced samples.” bioRxiv. https://doi.org/10.1101/2024.08.19.608591.

Lorenz, E. N. 1972. “Predictability: Does the Flap of a Butterfly’s Wings in Brazil Set Off a Tornado in Texas?” American Association for the Advancement of Science. http://gymportalen.dk/sites/lru.dk/files/lru/132_kap6_lorenz_artikel_the_butterfly_effect.pdf. (accessed October 5, 2024).

Lu, C., C. Lu, R. T. Lange, J. Foerster, J. Clune, and D. Ha. 2024. “The AI scientist: Towards fully automated open-ended scientific discovery.” arXiv. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2408.06292.

May, M. R., and B. Rannala. 2024. “Early detection of highly transmissible viral variants using phylogenomics.” Science Advances 10 (33):eadk7623. https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.adk7623.

Meijers, M., D. Ruchnewitz, J. Eberhardt, M. Karmakar, M. Luksza, and M. Lässig. 2024. “Concepts and methods for predicting viral evolution.” arXiv. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2403.12684.

Monzón, S., S. Varona, A. Negredo, S. Vidal-Freire, J. A. Patiño-Galindo, N. Ferressini-Gerpe, A. Zaballos, E. Orviz, O. Ayerdi, A. Muñoz-Gómez, A. Delgado-Iribarren, V. Estrada, C. García, F. Molero, P. Sánchez-Mora, M. Torres, A. Vázquez, J.-C. Galán, I. Torres, M. Causse del Río, L. Merino-Diaz, M. López, A. Galar, L. Cardeñoso, A. Gutiérrez, C. Loras, I. Escribano, M. E. Alvarez-Argüelles, L. del Río, M. Simón, M. A. Meléndez, J. Camacho, L. Herrero, P. Jiménez, M. L. Navarro-Rico, I. Jado, E. Giannetti, J. H. Kuhn, M. Sanchez-Lockhart, N. Di Paola, J. R. Kugelman, S. Guerra, A. García-Sastre, I. Cuesta, M. P. Sánchez-Seco, and G. Palacios. 2024. “Monkeypox virus genomic accordion strategies.” Nature Communications 15 (1):3059. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-024-46949-7.

Mouton, C. A., C. Lucas, and E. Guest. 2024. The Operational Risks of AI in Large-Scale Biological Attacks, Results of a Red-Team Study. Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corporation. https://www.rand.org/pubs/research_reports/RRA2977-2.html.

NASEM (National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine). 2018. Biodefense in the Age of Synthetic Biology. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. https://doi.org/10.17226/24890.

Patwardhan, T., K. Liu, T. Markov, N. Chowdhury, D. Leet, N. Cone, C. Maltbie, J. Huizinga, C. Wainwright, S. Jackson, S. Adler, R. Casagrande, and A. Madry. 2024. “Building an early warning system for LLM-aided biological threat creation.” OpenAI. https://openai.com/index/building-an-early-warning-system-for-llm-aided-biological-threat-creation/#design-principles.

Regan, D., and R. Dubin. 2023. “How to tell biodefense from an offensive bioweapons program.” Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists. https://thebulletin.org/2023/03/how-to-tell-biodefense-from-an-offensive-bioweapons-program/.

Rego-Costa, A., F. Débarre, and L. M. Chevin. 2018. “Chaos and the (un)predictability of evolution in a changing environment.” Evolution 72 (2):375–385. https://doi.org/10.1111/evo.13407.

Riesselman, A. J., J. B. Ingraham, and D. S. Marks. 2018. “Deep generative models of genetic variation capture the effects of mutations.” Nature Methods 15:816–822. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41592-018-0138-4.

Roffey, R., A. Tegnell, and F. Elgh. 2002. “Biological warfare in a historical perspective.” Clinical Microbiology and Infection 8 (8):450–454. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1469-0691.2002.00501.x.

Soice, E. H., R. Rocha, K. Cordova, M. Specter, and K. M. Esvelt. 2023. “Can large language models democratize access to dual-use biotechnology?” arXiv. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2306.03809.

Starr, T. N., A. J. Greaney, S. K. Hilton, D. Ellis, K. H. D. Crawford, A. S. Dingens, M. J. Navarro, J. E. Bowen, M. A. Tortorici, A. C. Walls, N. P. King, D. Veesler, and J. D. Bloom. 2020. “Deep mutational scanning of SARS-CoV-2 receptor binding domain reveals constraints on folding and ACE2 binding.” Cell 182 (5):1295–1310.e20. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2020.08.012.

Starr, T. N., A. J. Greaney, W. W. Hannon, A. N. Loes, K. Hauser, R. Dillen, E. Ferri, A. G. Farrell, B. Dadonaite, M. McCallum, K. A. Matreyek, D. Corti, D. Veesler, G. Snell, and J. D. Bloom. 2022. “Shifting mutational constraints in the SARS-CoV-2 receptor-binding domain during viral evolution.” Science 377 (6604):420–424. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.abo7896.

Sumida, K. H., R. Núñez-Franco, I. Kalvet, S. J. Pellock, B. I. M. Wicky, L. F. Milles, J. Dauparas, J. Wang, Y. Kipnis, N. Jameson, A. Kang, J. De La Cruz, B. Sankaran, A. K. Bera, G. Jiménez-Osés, and D. Baker. 2024. “Improving protein expression, stability, and function with ProteinMPNN.” Journal of the American Chemical Society 146 (3):2054–2061. https://doi.org/10.1021/jacs.3c10941.

Thadani, N. N., S. Gurev, P. Notin, N. Youssef, N. J. Rollins, D. Ritter, C. Sander, Y. Gal, and D. S. Marks. 2023. “Learning from prepandemic data to forecast viral escape.” Nature 622:818–825. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-023-06617-0.

Urbina, F., F. Lentzos, C. Invernizzi, and S. Ekins. 2022. “Dual use of artificial intelligence-powered drug discovery.” Nature Machine Intelligence 4 (3):189–191. https://doi.org/10.1038/s42256-022-00465-9.

U.S. Department of State. 2022. Adherence to and Compliance with Arms Control, Nonproliferation, and Disarmament Agreements and Commitments. https://www.state.gov/wp-content/uploads/2022/04/2022-Adherence-to-and-Compliance-with-Arms-Control-Nonproliferation-and-Disarmament-Agreements-and-Commitments-1.pdf. (accessed January 6, 2025).

Vázquez Torres, S., P. J. Y. Leung, P. Venkatesh, I. D. Lutz, F. Hink, H. H. Huynh, J. Becker, A. H. Yeh, D. Juergens, N. R. Bennett, A. N. Hoofnagle, E. Huang, M. J. MacCoss, M. Expòsit, G. R. Lee, A. K. Bera, A. Kang, J. De La Cruz, P. M. Levine, X. Li, M. Lamb, S. R. Gerben, A. Murray, P. Heine, E. N. Korkmaz, J. Nivala, L. Stewart, J. L. Watson, J. M. Rogers, and D. Baker. 2024. “De novo design of high-affinity binders of bioactive helical peptides.” Nature 626 (7998):435–442. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-023-06953-1.

Wagh, K., X. Shen, J. Theiler, B. Girard, J.-C. Marshall, D. C. Montefiori, and B. Korber. 2023. “Mutational basis of serum cross-neutralization profiles elicited by infection or vaccination with SARS-CoV-2 variants.” bioRxiv. https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.08.13.553144.

Wang, H., T. Fu, Y. Du, W. Gao, K. Huang, Z. Liu, P. Chandak, S. Liu, P. Van Katwyk, A. Deac, A. Anandkumar, K. Bergen, C. P. Gomes, S. Ho, P. Kohli, J. Lasenby, J. Leskovec, T.-Y. Liu, A. Manrai, D. Marks, B. Ramsundar, L. Song, J. Sun, J. Tang, P. Veličković, M. Welling, L. Zhang, C. W. Coley, Y. Bengio, and M. Zitnik. 2023. “Scientific discovery in the age of artificial intelligence.” Nature 620 (7972):47–60. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-023-06221-2.

Wang, J.-H., D. J. Gessler, W. Zhan, T. L. Gallagher, and G. Gao. 2024. “Adeno-associated virus as a delivery vector for gene therapy of human diseases.” Signal Transduction and Targeted Therapy 9 (1):78. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41392-024-01780-w.

Waters, K. 2024. “NIAID modeling host responses to understand severe human virus infections, multi-omic viral dataset catalog collection.” DataHub. Last Modified February 11, 2024. https://doi.org/10.25584/PRJ.U19AI106772/1971764 (accessed November 17, 2024).

Watson, J. L., D. Juergens, N. R. Bennett, B. L. Trippe, J. Yim, H. E. Eisenach, W. Ahern, A. J. Borst, R. J. Ragotte, L. F. Milles, B. I. M. Wicky, N. Hanikel, S. J. Pellock, A. Courbet, W. Sheffler, J. Wang, P. Venkatesh, I. Sappington, S. V. Torres, A. Lauko, V. De Bortoli, E. Mathieu, S. Ovchinnikov, R. Barzilay, T. S. Jaakkola, F. DiMaio, M. Baek, and D. Baker. 2023. “De novo design of protein structure and function with RFdiffusion.” Nature 620 (7976):1089-1100. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-023-06415-8.

Wittmann, B. J., T. Alexanian, C. Bartling, J. Beal, A. Clore, J. Diggans, K. Flyangolts, B. T. Gemler, T. Mitchell, S. T. Murphy, N. E. Wheeler, and E. Horvitz. 2024. “Toward AI-resilient screening of nucleic acid synthesis orders: Process, results, and recommendations.” bioRxiv. https://doi.org/10.1101/2024.12.02.626439.

Wu, N. C., J. Otwinowski, A. J. Thompson, C. M. Nycholat, A. Nourmohammad, and I. A. Wilson. 2020. “Major antigenic site B of human influenza H3N2 viruses has an evolving local fitness landscape.” Nature Communications 11:1233. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-020-15102-5.