The Age of AI in the Life Sciences: Benefits and Biosecurity Considerations (2025)

Chapter: 4 Promoting and Protecting AI-Enabled Innovation for Biosecurity

4

Promoting and Protecting AI-Enabled Innovation for Biosecurity

Executive Order 14110 on the Safe, Secure, and Trustworthy Development and Use of Artificial Intelligence and the National Security Memorandum on AI both articulate the promise and potential vulnerabilities of artificial intelligence (AI) applications. To this end, the first two guiding principles and priorities listed in the Executive Order state, (1) “artificial intelligence must be safe and secure”; and (2) “promoting responsible innovation, competition, and collaboration will allow the United States to lead in AI and unlock the technology’s potential to solve some of society’s most difficult challenges.” This chapter highlights beneficial applications of AI-enabled biological tools to enhance biosecurity and mitigate biological threats through improved prediction, detection, prevention, and response.

AI-ENABLED INFECTIOUS DISEASE BIOSURVEILLANCE

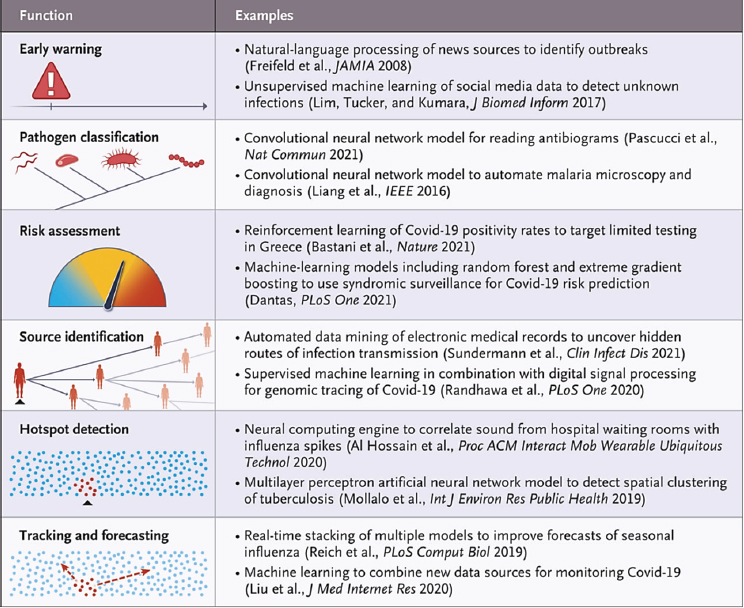

AI-enabled biological tools have long contributed to multiple aspects of infectious disease surveillance, such as epidemiological tracking and forecasting, early-warning systems, hotspot detection, and resource allocation. Figure 4-1 lists several significant roles of AI-based methods for infectious disease surveillance. Rapid advances were seen during the COVID-19 pandemic as multiple AI models were built and used to support diverse aspects of the response to the pandemic (Arora et al., 2021; Chen et al., 2021; Syrowatka et al., 2021; Ahmed, Boopathy, and Sudhagara Rajan, 2022; Brownstein et al., 2023; Malhotra and Sodhi, 2023; Sarmiento Varón et al., 2023).

SOURCE: Brownstein et al. (2023).

AI-based approaches to disease surveillance complement traditional approaches. Natural language processing is used to analyze global communication sources by parsing, filtering, and classifying the data to remove noise and focus on unusual infections. For example, HealthMap identified early cases of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) infections in China as a “cluster of pneumonia cases of unknown etiology” (Freifeld et al., 2008). Following an early-warning system’s identification of an outbreak, the pathogen in question can be classified by diagnostic algorithms, differentiating pathologic and epidemiologic characteristics of an outbreak and pointing to a potential pathogen. AI-enabled platforms are additionally promising to detect and investigate infectious disease outbreaks (Sintchenko and Holmes, 2015). For instance, phylodynamic approaches

can incorporate epidemiological data to infer host-related events such as disease introductions into discrete geographic regions or to constrain transmission hypotheses with contact data (Volz, Koelle, and Bedford, 2013; Ingle, Howden, and Duchene, 2021). Likelihood-free deep learning models are lowering the computational cost of these methods to build phylodynamic models in a fraction of the computational time (Kupperman, Leitner, and Ke, 2022; Voznica et al., 2022; Thompson et al., 2023). To stop an outbreak, infections can be traced by spatiotemporal clustering and contact tracing, aiding in the analysis of complex transmission patterns. Transmission during a pandemic can be traced using genetic epidemiological methods, which were greatly expanded and refined during the COVID-19 pandemic (Li et al., 2021; Niemi, Daly, and Ganna, 2022).

AI models that utilize deep learning can now analyze genomic data rapidly to identify known pathogens (Singh, 2022; Hou et al., 2024). By comparing both genetic and structural features of biological agents to known organisms, it may be possible for future AI models to provide insights into potential functions, virulence, pathogenicity, and other properties (Suster et al., 2024). However, as emphasized earlier in this report, such functionality will depend on the development of larger, more robust datasets on which the models can train.

AI-enabled real-time biosurveillance is indeed within reach. AI models can monitor genomic data continuously from various sources, amplify such data with predicted protein structure data, and detect emerging threats or unusual patterns that potentially indicate a new circulating pathogen. These same models can integrate genomic data with epidemiological information to predict outbreak patterns and inform public health responses in near real time (Brownstein et al., 2023; Suster et al., 2024).

AI models also can guide treatment decisions. In addition to serving as early-warning systems and identifiers of both potential biological agents and risks for outbreaks and epidemics, these same systems can be used to guide the design of effective treatments to inform public health strategies (Wong, de la Fuente-Nunez, and Collins, 2023; Wong et al., 2024).

AI-ENABLED BIODESIGN FOR COUNTERMEASURE DEVELOPMENT AND EMERGENCY RESPONSE

The rapid development of medical countermeasures (MCMs) (e.g., vaccines, biologics/therapeutics, and diagnostics) to address an emerging biological threat is essential to secure the world against such threats, whether they are natural or human-made. The past decade has seen a significant shift in the approach to vaccine research and development (R&D). Building on the foundational work done by many vaccinologists working on HIV/AIDS, the field has shifted from empirical development of vaccines to an

approach referred to as “structure-based” vaccine design (McLellan, Chen, Joyce, et al., 2013; McLellan, Chen, Leung, et al., 2013; Gilman et al., 2016; Crank et al., 2019; Graham, Gilman, and McLellan, 2019). In this approach neutralizing antibodies are used to identify and understand the best epitopes on the viral particle to target with a vaccine-elicited immune response or as a therapeutic monoclonal antibody. Once those antibodies have been identified, the structure of the target antigen is used to understand how the antibodies bind. Moreover, structural biology is used to guide stabilizing amino acids in the viral antigen that helped lock the target in a conformation that can best elicit protective immune responses. Such amino acid changes include stabilizing proline residues, discovered by Jason McLellan and Barney Graham working on Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV)—work that took years of wet-lab testing and optimization (Pallesen et al., 2017). When SARS-CoV-2 emerged, this foundational work fortunately had already been done; these mutations were ported into the viral spike protein to stabilize the antigen in many of the vaccine candidates, including both the Moderna and Pfizer/BioNTech mRNA vaccines, which ultimately were authorized for emergency use within a year (Corbett et al., 2020; Polack et al., 2020; Baden et al., 2021).

How will AI change this approach? Precedent that establishes a role for computational approaches to change how we mount an emergency response has already been set. During the COVID-19 pandemic, the Institute for Protein Design at the University of Washington used computational methods to generate a nanoparticle vaccine (SKYCovione) that was the first computationally designed protein medicine to complete a Phase III trial; SKYCovione was approved for emergency use during the COVID-19 pandemic (SK bioscience, 2023; Miranda et al., 2024). Subsequently, AI has further transformed the world of protein sciences and structural biology and, in so doing, is poised to affect discovery and design of MCMs in many positive ways. As an example, during the first weeks of COVID-19, researchers were “flying blind,” working with presumptive structures of what the SARSCoV-2 spike might look like based only on prior knowledge of other betacoronaviruses. Six weeks after the sequence of SARS-CoV-2 was released, the solved SARS-CoV-2 structure was published online on February 15, 2020 (Wrapp et al., 2020). Now, only four years later, AI-enabled protein structure prediction tools have dramatically changed these timelines—AlphaFold, which has already been used to predict the structure of millions of proteins (Tunyasuvunakool et al., 2021; Varadi et al., 2022, 2024), or other structure prediction models, would be able to predict the structure of a similar new viral glycoprotein accurately in a matter of hours, and AI could now be used to do more detailed molecular dynamic modeling and glycan profiling (Abramson et al., 2024; Krishna et al., 2024). Moreover, instead of relying on the proline residues that had been used to stabilize the

MERS-CoV spike, generative AI can now be used to design new vaccines rapidly and explore a vast array of additional stabilizing strategies such as cavity filling, scaffolds, and particulate display,1 thereby greatly reducing the time needed to design a vaccine against a new viral threat.

Similar acceleration can also be expected in the development of monoclonal antibodies for diagnostics and therapeutic use. In the pre-AI era, therapeutic monoclonal antibodies were produced by expression from antibody gene sequences identified in B cells isolated from infected humans that were shown to have viral neutralization capacity (Gilman et al., 2016). This process is time consuming, as it requires identification of a convalescent donor as well as selection of the appropriate B cells and isolation or expression of the monoclonal antibodies. During COVID-19, the first antibodies in the United States were isolated from the B cells of some of the first infected patients in North America (Zost et al., 2020). In the future, improved bio-design tools likely will make it possible for monoclonal antibodies or other protein biologics to be generated rapidly in silico (He et al., 2024). These designed biologics will be able to bind to predicted or actual structures on known viral antigens, circumventing the need to isolate antibodies from convalescent patients and expediting the development of both diagnostics and therapeutics.

In the case of both vaccines and biologics, AI-enabled biological tools make it possible for much of the work to be performed in silico, allowing a global outbreak response to be initiated anywhere in the world based initially on viral sequence alone, which holds the promise of dramatically reducing the time from detecting an outbreak to initiating countermeasure development. The committee notes that while going from an AI-designed sequence for a potential pathogen to having the pathogen will be met with significant bottlenecks, going from an AI-designed sequence to a therapeutic antibody is more akin to the earlier example of toxin design—that is, there is much less of a bottleneck to make a single protein than a complex system such as a virus.

AI AND BIODESIGN SECURITY

Although AI-enabled biological tools could be misused for harmful applications, as described in Chapter 3, the tools may also be used to screen and prevent the creation of biological threats by augmenting current nucleic acid screening methods. However, this specific application of AI is an emerging area and would need more research. Nucleic acid synthesis is a critical chokepoint between the digital and physical divide; therefore,

___________________

1 Presentation to the committee by Jimmy Gollihar, August 14, 2024. See Appendix B.

measures to mitigate the misuse of commercial services for nucleic acid synthesis have been developed and implemented, including screening of both sequences and customers. The International Gene Synthesis Consortium (IGSC) is an industry-led group of gene synthesis companies formed in 2009 that sets voluntary standards for screening nucleic acid synthesis orders based on U.S. and international biosecurity standards. Most major nucleic acid synthesis providers are part of the IGSC and use a common protocol to screen the sequences of synthetic gene orders and the legitimacy of customers. Screening nucleic acid sequences (and modified sequences that retain homology to known amino acid sequences) against “sequences of concern” (SOCs), such as those on the Select Agents and Toxins List, is routine and standard practice.

Executive Order 141102 includes directives for the U.S. federal government to reduce risks of misuse of synthetic nucleic acids. Subsequently, the Framework for Nucleic Acid Synthesis Screening was released in April 2024, requiring all federal agencies that fund life sciences research to mandate the use of nucleic acid synthesis providers that (1) attest they are implementing screening of synthetic nucleic acids; (2) screen purchase orders for synthetic nucleic acids to identify SOCs; (3) screen customers to verify their legitimacy; (4) report potentially illegitimate purchase orders of synthetic nucleic acids involving SOCs or of benchtop nucleic acid synthesis equipment; (5) retain records relating to purchase orders for synthetic nucleic acids and benchtop nucleic acid synthesis equipment; and (6) take steps to ensure cybersecurity and information security (National Science and Technology Council, 2024). This builds upon the longstanding National Institutes of Health (NIH) Guidelines for Research Involving Recombinant or Synthetic Nucleic Acid Molecules, most recently updated in April 2024 (National Institutes of Health, 2024).

At this time, an SOC is defined as a “best match” to a sequence of already federally regulated agents (such as the Biological Select Agents and Toxins List,3 which is codified in the USA PATRIOT Act [2001]4 and the Bioterrorism Act [2002],5 or the Commerce Control List)6 except when the sequence is also found in an unregulated organism or toxin. The Framework for Nucleic Acid Synthesis Screening has updated the SOC definition

___________________

2 Exec. Order No. 14110, Fed. Reg. 24283 (October 30, 2023). See https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2023/11/01/2023-24283/safe-secure-and-trustworthy-development-and-use-of-artificial-intelligence/ (accessed October 12. 2024).

3 See https://www.selectagents.gov/sat/list.htm (accessed October 10, 2024).

4 USA PATRIOT Act of 2001, Pub. L. No. 107-56, 115 Stat. 272.

5 Public Health Security and Bioterrorism Preparedness and Response Act of 2002, Pub. L. No. 107-188, 116 Stat 594.

6 See https://www.bis.gov/regulations/ear/part-774/supplement-1-774/commerce-control-list#category1 (accessed October 14, 2024).

to also include those “sequences known to contribute to pathogenicity or toxicity, even when not derived from or encoding regulated biological agents” (Fast Track Action Committee on Synthetic Nucleic Acid Procurement Screening of the National Science and Technology Council, 2024). Determining these sequences is a challenging, highly contextual process that has been upended by generative AI tools (Godbold and Scholz, 2024). This area will require more research to be useful for regulatory purposes.

Any new security measures would build on the existing practice recommended by the IGSC for logging synthesized nucleic acids to establish provenance. Logging designs and orders does not itself prevent misuse, but this practice can assist with attribution. While developing measures to diminish misuse of commercial services for nucleic acid synthesis is important, such an effort is an imperfect control point because it will not deter all potential malicious actors and there are technological means to bypass commercial synthesis. For example, future development of benchtop synthesis devices would bypass commercial synthesis screening processes. Customer screening of these devices and embedded security screening software, similar to the processes in nucleic acid synthesis, will remain important. Monitoring developments in this area is important as is engaging companies with biosecurity expertise in advance of any commercial launch of a benchtop device.

AI-enabled biological tools may pose new challenges for nucleic acid synthesis screening. It is difficult to infer the function of a novel design without context on its intended use, and current screening methods may not detect every possible sequence that may be concerning. Nucleic acid synthesis providers may need to rely increasingly on metadata to evaluate incoming orders. Today, there are no standards for metadata to be included with nucleic acid synthesis orders, beyond “know your customer” guidance. “Know your order” guidance could assist nucleic acid synthesis providers in screening orders more effectively.

Beyond nucleic acid synthesis screening, the development of a layered approach that might include “intent-based screening,” guardrails embedded within design tools and logging and tracking of who is using design tools (i.e., “know your design screening”), has been suggested. While these could complement existing screening approaches to reduce the chance of misuse of design tools and serve as deterrents, such approaches may be both impractical to implement and ineffective to deter more sophisticated actors.

Moreover, screening how users access and leverage AI tools is challenging and prone to false positives that can hinder or prevent legitimate research that may itself be beneficial. Closed-source AI tools are often accessible via an application programming interface (API), which can effectively put a “black box” around proprietary models and any security features that have been implemented. For example, the committee learned from Jason McLellan that expert vaccine researchers seeking to access the

AlphaFold3 API to develop a mpox vaccine were initially barred from using the API; the AlphaFold3 developers had planned to prevent the use of their API for the design of certain viral sequences.7 While the researchers were eventually permitted to use AlphaFold3 for mpox vaccine design after several weeks’ delay, the event underscores the challenges of screening for misuse via design tool usage. Access restriction may present challenges to end users who have legitimate designs as an unintended consequence of security features, and further research to optimize screening methodologies is warranted. Here, AI-enabled biological tools themselves may be integrated in screening and help improve screening over traditional methods.

The implementation of security screening for AI-enabled biological tools has evolved rapidly with the release of newer generative models such as those based on large language models and represents an emerging area of research. Currently, AI-based approaches have a few limitations. Screening can occur prior to training a generative model by leaving data on harmful biological agents out of the training dataset completely. This approach, however, may impact the performance of a model intended for beneficial uses such as vaccine design (Kaplan et al., 2020; Hoffman et al., 2022). Agent-based models instructed to avoid designing harmful sequences or, alternatively, template-based design models can be prohibited from using particular structures or sequences as templates for generative design—as seen in the mpox example. In the near future, optimizing and increasing efficiency of AI-enabled biological tools in screening may provide an additional mitigation strategy.

Conclusion: More research in new methodologies for nucleic acid synthesis screening, including how to leverage AI-enabled biological tools for screening, is needed for this process to be an efficient control point and possible strategy to mitigate potential biosecurity risks. Engaging practitioners and developers of AI-enabled biological tools to explore the most effective approaches for implementation is important as is engaging biologists and other developers to assess impacts of screening on public health preparedness and response.

BALANCING AI-ENABLED RESPONSES TO BIOLOGICAL THREATS AND POTENTIAL RISKS

AI applications for biosecurity have great potential to enhance biosurveillance, bolster early-warning systems, improve infectious disease monitoring, and accelerate the development of MCMs for a variety of

___________________

7 Presentation to the committee by Jason McLellan and Emanuele Andreano, October 1, 2024. See Appendix B.

diseases—from infectious to noncommunicable. In general, research programs for understanding the biology of infectious agents are important to support the development of vaccines and therapeutics to prevent and treat diseases caused by such agents, whether from natural occurrences or intentional threats. Along these lines, associated biological datasets will be useful and necessary for training AI models to accelerate the development of such MCMs, bolster biosurveillance, and support other previously mentioned biosecurity applications.

Various institutes and offices housed within the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), such as the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and NIH, have existing programs that support infectious disease research. Specifically, CDC houses the National Center for Emerging and Zoonotic Infectious Diseases,8 which has the mission of preventing and controlling infectious disease. Within NIH, the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID) is the primary funder of both intramural and extramural research to better understand the biology of infectious diseases affecting humans,9 including those that are emerging.10 Within NIAID, the Integrated Research Facility at Fort Detrick is a “collaborative resource that facilitates multidisciplinary research to understand, treat, prevent, and eradicate diseases caused by novel, emerging, and highly virulent viruses.”11 Other institutes at NIH centers investigate how environmental conditions affect immunological defenses to infectious disease (National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences12) and which viruses cause human cancer (National Cancer Institute13).

The U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) also has research programs that study infectious diseases affecting plants and animals. Relevant USDA agencies include Animal and Plant Health Inspection Services,14 the National Institute of Food and Agriculture,15 and the National Bio and Agro-Defense Facility.16 The U.S. Army Medical Research Institute of Infectious Diseases,17 under the U.S. Department of Defense (DoD), also conducts MCM research

___________________

8 See https://www.cdc.gov/ncezid/about/index.html (accessed November 17, 2024).

9 See https://www.niaid.nih.gov/research/infectious-diseases (accessed November 17, 2024).

10 See https://www.niaid.nih.gov/research/centers-research-emerging-infectious-diseases (accessed November 17, 2024).

11 See https://www.niaid.nih.gov/research/frederick-integrated-research-facility (accessed November 17, 2024).

12 See https://www.niehs.nih.gov/research/supported/health/autoimmune (accessed November 18, 2024).

13 See https://ccr.cancer.gov/staff-directory/principal-investigators/research-areas/cancer-and-viruses (accessed November 18, 2024).

14 See https://www.aphis.usda.gov/ (accessed November 18, 2024).

15 See https://www.nifa.usda.gov/about-nifa (accessed November 18, 2024).

16 See https://www.usda.gov/nbaf (accessed November 18, 2024).

17 See https://usamriid.health.mil/ (accessed November 18, 2024).

“to deter and defend against current and emerging biological threats.” The National Biodefense Analysis and Countermeasures Center18 is situated within the U.S. Department of Homeland Security and plays an important role in filling knowledge gaps about biological agents and R&D related to MCMs. Other relevant programs that support research on infectious disease biology include the National Science Foundation’s program on Ecology and Evolution of Infectious Diseases19 and CDC’s One Health Initiative,20 which involves collaborative efforts of several agencies including NIH and USDA.21 Though not directly related to infectious disease research, the U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) is home to many biological research programs (including those at DOE’s national laboratories)—for example, the Joint Genome Institute22 is a user facility that provides a resource for genomic research. These research programs and investments will need to continue, and ideally expand, in support of understanding the biology of infectious agents toward enhanced biosecurity enabled by AI.

Recommendation: The U.S. Department of Defense, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA), U.S. Department of Energy, U.S. Department of Homeland Security, and other agencies that support and conduct research should continue to invest in vigorous research programs to understand the biology of infectious agents. As a part of these programs, agencies should also invest in and implement biosurveillance networks through the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and USDA in cooperation with public health agencies globally.

In addition to this enhanced understanding through research and data collection, research supporting the development and testing of new models for MCM development and biosurveillance is also needed. Several programs are currently in place that focus on the development of MCMs. For instance, the Biomedical Advanced Research and Development Authority (BARDA), which is situated within the Administration for Strategic Preparedness and Response in HHS, “promotes the advanced development of medical countermeasures to protect Americans

___________________

18 See https://www.dhs.gov/science-and-technology/national-biodefense-analysis-and-countermeasures-center (accessed November 18, 2024).

19 See https://new.nsf.gov/funding/opportunities/eeid-ecology-evolution-infectious-diseases. (accessed November 18, 2024).

20 See https://www.cdc.gov/one-health/about/ (accessed November 18, 2024).

21 See science-and-technology/national-biodefense-analysis-and-countermeasures-center (accessed November 18, 2024).

22 See https://jgi.doe.gov/ (accessed November 18, 2024).

and respond to 21st century health security threats.”23 As a part of its 2022–2026 strategic plan, BARDA committed to investing in technologies that could make MCMs “faster, safer, and more accessible” as a part of its preparedness goal.24 BARDA’s Division of Research, Innovation, and Ventures25 specifically invests in a broad portfolio and would be well suited to invest in approaches using AI-enabled design tools for development of MCMs. Funders like the Advanced Research Projects Agency for Health (ARPA-H) and the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA) invest in high-risk projects and also can consider investing in AI-enabled design tools for MCM development. Both ARPA-H26 and DARPA27 already have plans to apply AI to biology in innovative ways. For instance, the new ARPA-H CATALYST program plans to develop predictive drug safety and efficacy models to develop in silico models of human physiology for predictive drug safety and efficacy testing, reducing the time from drug discovery to delivery. The DoD Chemical and Biological Defense28 group, Defense Threat Reduction Agency,29 and Defense Health Agency30 all play a role in biosurveillance. In addition, innovations in AI tools are largely driven by the commercial sector, making public–private partnerships important in this endeavor.

Recommendation: Entities within the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (e.g., National Institutes of Health, Biomedical Advanced Research and Development Authority, and Advanced Research Projects Agency for Health) and the U.S. Department of Defense (e.g., Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency and Chemical and Biological Defense) should fund approaches using artificial intelligence–enabled design tools for application in medical countermeasure development, especially in the face of an epidemic, pandemic, or other biological threat.

___________________

23 See https://aspr.hhs.gov/AboutASPR/ProgramOffices/BARDA/Pages/default.aspx (accessed November 18, 2024).

24 See https://medicalcountermeasures.gov/barda/strategic-plan/ (accessed November 18, 2024).

25 See https://drive.hhs.gov/ventures.html (accessed November 18, 2024).

26 See https://www.synbiobeta.com/read/arpa-h-unveils-program-to-revolutionize-drug-safety-and-efficacy-testing (accessed November 18, 2024).

27 See https://www.synbiobeta.com/read/darpas-aixbto-initiative-pushing-bioinnovation-boundaries (accessed November 18, 2024).

28 See https://www.acq.osd.mil/ncbdp/cbd/ (accessed November 18, 2024).

29 See https://www.dtra.mil/ (accessed November 18, 2024).

30 See https://www.health.mil/About-MHS/OASDHA/Defense-Health-Agency (accessed November 18, 2024).

Recommendation: As part of a national preparedness strategy, the Biomedical Advanced Research and Development Authority, U.S. Department of Energy, and U.S. Department of Defense should establish a public–private partnership, analogous to Operation Warp Speed and the COVID-19 High-Performance Computing Consortium, that can both leverage and provide continuous access to artificial intelligence–enabled tools and computational resources and be activated rapidly in an emergency response.

The potential misuse of biological data and knowledge for harmful applications by an actor with malicious intent presents a security concern. When considering biosecurity risks, it is important to distinguish between technical capability and intent to avoid unnecessarily stifling R&D advances that are critical in response strategies for natural infectious disease threats and intentional threats. Efforts are ongoing to address these issues in various sectors including the government, the scientific community and its broader enterprise, and commercial developers of the relevant technologies. Both the Executive Order and National Security Memorandum on AI outline such initiatives, including the development of risk evaluations and stakeholder engagement (see Table 1-1), similar to recommendations articulated in this report. Other policies are in place that oversee pathogen research in general but do not include AI, such as the Policy for Oversight of Dual Use Research of Concern and Pathogens with Enhanced Pandemic Potential.31

The committee summarizes the following considerations discussed in this report. Application of AI-enabled biological tools is an emerging area of research that is developing rapidly. At present, the capabilities of AI tools have certain limitations that are described in previous chapters and in Appendix A. The present limitations, as well as uplift in capabilities, hold true whether for beneficial or harmful applications. AI-enabled biological tools provide data-driven guidance for experimental validation, and the resulting experimental data may then be used to improve the models in an iterative Design-Build-Test-Learn cycle, as discussed in Chapter 2. However, physical production of digital outputs remains a significant barrier. In the future, significant improvements in automated laboratories may assist with experimental throughput and scalability. Furthermore, AI-enabled biological tools have promising applications to enhance and augment biosecurity responses in naturally occurring outbreaks or intentional events.

___________________

31 See https://aspr.hhs.gov/S3/Documents/USG-Policy-for-Oversight-of-DURC-and-PEPP-May2024-508.pdf/ (accessed November 18, 2024).

Amassing significant datasets, sometimes generated through compute-intensive simulations, is a prerequisite for training AI models (e.g., Protein Data Bank [PDB] for AlphaFold); therefore, the availability of high-quality, robust data can be the leading indicator of an emerging or developing AI model capability. Currently, no approach exists to determine the absolute amount of data needed for training, but, as previously noted, AlphaFold was trained on a few hundred thousand protein structures in PDB. It is important to note that dataset size is comparatively significant for biology because the process to generate biological data is often laborious. Moreover, more datasets are necessary to capture the diversity and complexity of biology and subsequently account for them in models. The scaling hypothesis indicates that model performance improves as the size of the model, dataset, and computational resources increases (Kaplan et al., 2020; Hoffmann et al., 2022).

In light of the rapid pace of development of AI-enabled biological tools and the continued collection of training data that could lead to new or improved capabilities of such models, the committee suggests the adoption of an “if-then” approach to guide future vulnerability and risk assessment and mitigation. The if-then strategy accounts for these dynamics without being prescriptive or restrictive based on predicting future capabilities.

An if-then approach would allow for the continual assessment and periodic reassessment of vulnerabilities and risks using a principles-based thought framework. These evaluations should be anchored in both data availability and the associated emerging AI capabilities as well as real-world threat models that incorporate all four factors articulated in the 2018 framework and in Figure 3-3 (i.e., usability of the technology, usability as a weapon, requirement of actors, and potential for mitigation) (NASEM, 2018). In addition, the if-then strategy should establish benchmarks and metrics to track data availability and associated capability progress as well as a set of thresholds that, once surpassed by emerging capabilities, activate risk assessment and mitigation.

Recommendation: The U.S. Department of Defense and the U.S. Artificial Intelligence (AI) Safety Institute should develop an “if-then” strategy to evaluate continuously both the availability and quality of data and emerging AI-enabled capabilities to anticipate changes in the risk landscape (e.g., if dataset “x” is collected, then monitor for the emergence of capability “y”; if capability “y” is developed, then watch for output “z”). Evaluation of AI-enabled biological tool capabilities may be conducted in a sandbox environment.

- Example datasets of interest:

- If clear associations between viral sequences and virulence parameters become known, then evaluate the capability of AI models to predict or design pathogenicity and/or virulence.

- If robust viral phylogenomic sequence datasets linked to epidemiological data become available, then assess for the development of new AI models of transmissibility that could be used to design new threats.

- Example AI models that warrant assessment:

- If AI models are developed that infer mechanisms of pathogenicity and transmissibility from pathogen sequencing data, then watch for attempts to modify existing pathogens to increase their virulence or transmissibility.

- If AI models are developed that could predictably generate a novel replication-competent virus, then assess risk for bioweapon development.

REFERENCES

Abramson, J., J. Adler, J. Dunger, R. Evans, T. Green, A. Pritzel, O. Ronneberger, L. Willmore, A. J. Ballard, J. Bambrick, S. W. Bodenstein, D. A. Evans, C. C. Hung, M. O’Neill, D. Reiman, K. Tunyasuvunakool, Z. Wu, A. Žemgulytė, E. Arvaniti, C. Beattie, O. Bertolli, A. Bridgland, A. Cherepanov, M. Congreve, A. I. Cowen-Rivers, A. Cowie, M. Figurnov, F. B. Fuchs, H. Gladman, R. Jain, Y. A. Khan, C. M. R. Low, K. Perlin, A. Potapenko, P. Savy, S. Singh, A. Stecula, A. Thillaisundaram, C. Tong, S. Yakneen, E. D. Zhong, M. Zielinski, A. Žídek, V. Bapst, P. Kohli, M. Jaderberg, D. Hassabis, and J. M. Jumper. 2024. “Accurate structure prediction of biomolecular interactions with AlphaFold 3.” Nature 630 (8016):493–500. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-024-07487-w.

Ahmed, A., P. Boopathy, and S. Sudhagara Rajan. 2022. “Artificial intelligence for the novel corona virus (COVID-19) pandemic: Opportunities, challenges, and future directions.” International Journal of E-Health and Medical Communications (IJEHMC) 13 (2):1–21. https://doi.org/10.4018/IJEHMC.20220701.oa5.

Arora, G., J. Joshi, R. S. Mandal, N. Shrivastava, R. Virmani, and T. Sethi. 2021. “Artificial intelligence in surveillance, diagnosis, drug discovery and vaccine development against COVID-19.” Pathogens 10 (8):1048. https://doi.org/10.3390/pathogens10081048.

Baden, L. R., H. M. El Sahly, B. Essink, K. Kotloff, S. Frey, R. Novak, D. Diemert, S. A. Spector, N. Rouphael, C. B. Creech, J. McGettigan, S. Khetan, N. Segall, J. Solis, A. Brosz, C. Fierro, H. Schwartz, K. Neuzil, L. Corey, P. Gilbert, H. Janes, D. Follmann, M. Marovich, J. Mascola, L. Polakowski, J. Ledgerwood, B. S. Graham, H. Bennett, R. Pajon, C. Knightly, B. Leav, W. Deng, H. Zhou, S. Han, M. Ivarsson, J. Miller, and T. Zaks. 2021. “Efficacy and safety of the mRNA-1273 SARS-CoV-2 vaccine.” New England Journal of Medicine 384 (5):403–416. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa2035389.

Brownstein, J. S., B. Rader, C. M. Astley, and H. Tian. 2023. “Advances in artificial intelligence for infectious-disease surveillance.” New England Journal of Medicine 388(17):1597–1607. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMra2119215.

Chen, J., K. Li, Z. Zhang, K. Li, and P. S. Yu. 2021. “A survey on applications of artificial intelligence in fighting against COVID-19.” ACM Computing Surveys 54 (8):1–32. https://doi.org/10.1145/3465398.

Corbett, K. S., D. K. Edwards, S. R. Leist, O. M. Abiona, S. Boyoglu-Barnum, R. A. Gillespie, S. Himansu, A. Schäfer, C. T. Ziwawo, A. T. DiPiazza, K. H. Dinnon, S. M. Elbashir, C. A. Shaw, A. Woods, E. J. Fritch, D. R. Martinez, K. W. Bock, M. Minai, B. M. Nagata, G. B. Hutchinson, K. Wu, C. Henry, K. Bahl, D. Garcia-Dominguez, L. Ma, I. Renzi, W.-P. Kong, S. D. Schmidt, L. Wang, Y. Zhang, E. Phung, L. A. Chang, R. J. Loomis, N. E. Altaras, E. Narayanan, M. Metkar, V. Presnyak, C. Liu, M. K. Louder, W. Shi, K. Leung, E. S. Yang, A. West, K. L. Gully, L. J. Stevens, N. Wang, D. Wrapp, N. A. DoriaRose, G. Stewart-Jones, H. Bennett, G. S. Alvarado, M. C. Nason, T. J. Ruckwardt, J. S. McLellan, M. R. Denison, J. D. Chappell, I. N. Moore, K. M. Morabito, J. R. Mascola, R. S. Baric, A. Carfi, and B. S. Graham. 2020. “SARS-CoV-2 mRNA vaccine design enabled by prototype pathogen preparedness.” Nature 586 (7830):567–571. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-020-2622-0.

Crank, M. C., T. J. Ruckwardt, M. Chen, K. M. Morabito, E. Phung, P. J. Costner, L. A. Holman, S. P. Hickman, N. M. Berkowitz, I. J. Gordon, G. V. Yamshchikov, M. R. Gaudinski, A. Kumar, L. A. Chang, S. M. Moin, J. P. Hill, A. T. DiPiazza, R. M. Schwartz, L. Kueltzo, J. W. Cooper, P. Chen, J. A. Stein, K. Carlton, J. G. Gall, M. C. Nason, P. D. Kwong, G. L. Chen, J. R. Mascola, J. S. McLellan, J. E. Ledgerwood, and B. S. Graham. 2019. “A proof of concept for structure-based vaccine design targeting RSV in humans.” Science 365 (6452):505–509. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aav9033.

Fast Track Action Committee on Synthetic Nucleic Acid Procurement Screening of the National Science and Technology Council. 2024. Framework for Nucleic Acid Synthesis Screening. Office of Science and Technology Policy. https://www.whitehouse.gov/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/Nucleic-Acid_Synthesis_Screening_Framework.pdf. (accessed October 10, 2024).

Freifeld, C. C., K. D. Mandl, B. Y. Reis, and J. S. Brownstein. 2008. “HealthMap: Global infectious disease monitoring through automated classification and visualization of internet media reports.” Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association 15 (2):150–157. https://doi.org/10.1197/jamia.M2544.

Gilman, M. S., C. A. Castellanos, M. Chen, J. O. Ngwuta, E. Goodwin, S. M. Moin, V. Mas, J. A. Melero, P. F. Wright, B. S. Graham, J. S. McLellan, and L. M. Walker. 2016. “Rapid profiling of RSV antibody repertoires from the memory B cells of naturally infected adult donors.” Science Immunology 1 (6). https://doi.org/10.1126/sciimmunol.aaj1879.

Godbold, G. D. and M. B. Scholz. 2024. “Annotation of functions of sequences of concern and its relevance to the new biosecurity regulatory framework in the United States.” Applied Biosafety 29 (3):142–149. https://doi.org/10.1089/apb.2023.0030.

Graham, B. S., M. S. A. Gilman, and J. S. McLellan. 2019. “Structure-based vaccine antigen design.” Annual Review of Medicine 70:91–104. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-med-121217-094234.

He, X. H., J. R. Li, J. Xu, H. Shan, S. Y. Shen, S. H. Gao, and H. E. Xu. 2024. “AI-driven antibody design with generative diffusion models: Current insights and future directions.” Acta Pharmacologica Sinica. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41401-024-01380-y.

Hoffmann, J., S. Borgeaud, Mensch, E. Buchatskaya, T. Cai, E. Rutherford, D. d. L. Casas, L. A. Hendricks, J. Welbl, A. Clark, T. Hennigan, E. Noland, K. Millican, G. van den Driessche, B. Damoc, A. Guy, S. Osindero, K. Simonyan, E. Elsen, O. Vinyals, J. W. Rae, and L. Sifre. 2022. “Training compute-optimal large language models.” arXiv. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2203.15556.

Hou, X., Y. He, P. Fang, S. Q. Mei, Z. Xu, W. C. Wu, J. H. Tian, S. Zhang, Z. Y. Zeng, Q. Y. Gou, G. Y. Xin, S. J. Le, Y. Y. Xia, Y. L. Zhou, F. M. Hui, Y. F. Pan, J. S. Eden, Z. H. Yang, C. Han, Y. L. Shu, D. Guo, J. Li, E. C. Holmes, Z. R. Li, and M. Shi. 2024. “Using artificial intelligence to document the hidden RNA virosphere.” Cell 187 (24):6929–6942.e16. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2024.09.027.

Ingle, D. J., B. P. Howden, and S. Duchene. 2021. “Development of phylodynamic methods for bacterial pathogens.” Trends in Microbiology 29 (9):788–797. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tim.2021.02.008.

Kaplan, J., S. McCandlish, T. Henighan, T. B. Brown, B. Chess, R. Child, S. Gray, A. Radford, J. Wu, D. Amodei. 2020. “Scaling laws for neural language models.” arXiv. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2001.08361.

Krishna, R., J. Wang, W. Ahern, P. Sturmfels, P. Venkatesh, I. Kalvet, G. R. Lee, F. S. MoreyBurrows, I. Anishchenko, I. R. Humphreys, R. McHugh, D. Vafeados, X. Li, G. A. Sutherland, A. Hitchcock, C. N. Hunter, A. Kang, E. Brackenbrough, A. K. Bera, M. Baek, F. DiMaio, and D. Baker. 2024. “Generalized biomolecular modeling and design with RoseTTAFold All-Atom.” Science 384 (6693):eadl2528. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.adl2528.

Kupperman, M. D., T. Leitner, and R. Ke. 2022. “A deep learning approach to real-time HIV outbreak detection using genetic data.” PLOS Computational Biology 18 (10):e1010598. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pcbi.1010598.

Li, J., S. Lai, G. F. Gao, and W. Shi. 2021. “The emergence, genomic diversity and global spread of SARS-CoV-2.” Nature 600(7889):408–418. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-021-04188-6.

Malhotra, D., and G. K. Sodhi. 2023. “A survey on the role of ML and AI in fighting Covid-19.” 2023 International Conference on Advancement in Computation & Computer Technologies (InCACCT), Gharuan, India, May 5–6, 2023. https://doi.org/10.1109/InCACCT57535.2023.10141732.

McLellan, J. S., M. Chen, M. G. Joyce, M. Sastry, G. B. Stewart-Jones, Y. Yang, B. Zhang, L. Chen, S. Srivatsan, A. Zheng, T. Zhou, K. W. Graepel, A. Kumar, S. Moin, J. C. Boyington, G. Y. Chuang, C. Soto, U. Baxa, A. Q. Bakker, H. Spits, T. Beaumont, Z. Zheng, N. Xia, S. Y. Ko, J. P. Todd, S. Rao, B. S. Graham, and P. D. Kwong. 2013. “Structure-based design of a fusion glycoprotein vaccine for respiratory syncytial virus.” Science 342 (6158):592–598. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1243283.

McLellan, J. S., M. Chen, S. Leung, K. W. Graepel, X. Du, Y. Yang, T. Zhou, U. Baxa, E. Yasuda, T. Beaumont, A. Kumar, K. Modjarrad, Z. Zheng, M. Zhao, N. Xia, P. D. Kwong, and B. S. Graham. 2013. “Structure of RSV fusion glycoprotein trimer bound to a prefusion-specific neutralizing antibody.” Science 340 (6136):1113–1117. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1234914.

Miranda, M. C., E. Kepl, M. J. Navarro, C. Chen, M. Johnson, K. R. Sprouse, C. Stewart, A. Palser, A. Valdez, D. Pettie, C. Sydeman, C. Ogohara, J. C. Kraft, M. Pham, M. Murphy, S. Wrenn, B. Fiala, R. Ravichandran, D. Ellis, L. Carter, D. Corti, P. Kellam, K. Lee, A. C. Walls, D. Veesler, and N. P. King. 2024. “Potent neutralization of SARS-CoV-2 variants by RBD nanoparticle and prefusion-stabilized spike immunogens.” npj Vaccines 9 (1):184. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41541-024-00982-1.

NASEM (National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine). 2018. Biodefense in the Age of Synthetic Biology. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. https://doi.org/10.17226/24890.

National Institutes of Health. 2024. NIH Guidelines for Research Involving Recombinant or Synthetic Nucleic Acid Molecules. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. https://osp.od.nih.gov/wp-content/uploads/NIH_Guidelines.htm.

Niemi, M. E. K., M. J. Daly, and A. Ganna. 2022. “The human genetic epidemiology of COVID-19.” Nature Reviews Genetics 23 (9):533–546. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41576-022-00478-5.

Pallesen, J., N. Wang, K. S. Corbett, D. Wrapp, R. N. Kirchdoerfer, H. L. Turner, C. A. Cottrell, M. M. Becker, L. Wang, W. Shi, W.-P. Kong, E. L. Andres, A. N. Kettenbach, M. R. Denison, J. D. Chappell, B. S. Graham, A. B. Ward, and J. S. McLellan. 2017. “Immunogenicity and structures of a rationally designed prefusion MERS-CoV spike antigen.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences USA 114 (35):E7348–E7357. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.170730411.

Polack, F. P., S. J. Thomas, N. Kitchin, J. Absalon, A. Gurtman, S. Lockhart, J. L. Perez, G. Pérez Marc, E. D. Moreira, C. Zerbini, R. Bailey, K. A. Swanson, S. Roychoudhury, K. Koury, P. Li, W. V. Kalina, D. Cooper, R. W. Frenck, Jr., L. L. Hammitt, Ö. Türeci, H. Nell, A. Schaefer, S. Ünal, D. B. Tresnan, S. Mather, P. R. Dormitzer, U. Şahin, K. U. Jansen, and W. C. Gruber. 2020. “Safety and efficacy of the BNT162b2 mRNA Covid-19 vaccine.” New England Journal of Medicine 383 (27):2603–2615. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa2034577.

Sarmiento Varón, L., J. González-Puelma, D. Medina-Ortiz, J. Aldridge, D. Alvarez-Saravia, R. Uribe-Paredes, and M. A. Navarrete. 2023. “The role of machine learning in health policies during the COVID-19 pandemic and in long COVID management.” Frontiers in Public Health 11. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2023.1140353.

Singh, A. 2022. “Viral discovery at a global scale.” Nature Methods 19 (3):273. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41592-022-01430-5.

Sintchenko, V., and E. C. Holmes. 2015. “The role of pathogen genomics in assessing disease transmission.” BMJ: British Medical Journal 350:h1314. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.h1314.

SK bioscience. 2023. “SK bioscience COVID-19 vaccine granted emergency use listing by the World Health Organization.” https://www.skbioscience.com/en/news/news_01_01?mode=view&id=214&] (accessed October 8, 2024).

Suster, C. J. E., D. Pham, J. Kok, and V. Sintchenko. 2024. “Emerging applications of artificial intelligence in pathogen genomics.” Frontiers in Bacteriology 3. https://doi.org/10.3389/fbrio.2024.1326958.

Syrowatka, A., M. Kuznetsova, A. Alsubai, A. L. Beckman, P. A. Bain, K. J. T. Craig, J. Hu, G. P. Jackson, K. Rhee, and D. W. Bates. 2021. “Leveraging artificial intelligence for pandemic preparedness and response: A scoping review to identify key use cases.” npj Digital Medicine 4 (1):96. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41746-021-00459-8.

Thompson, A., B. Liebeskind, E. J. Scully, and M. Landis. 2023. “Deep learning and likelihood approaches for viral phylogeography converge on the same answers whether the inference model is right or wrong.” bioRxiv. https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.02.08.527714.

Tunyasuvunakool, K., J. Adler, Z. Wu, T. Green, M. Zielinski, A. Žídek, A. Bridgland, A. Cowie, C. Meyer, A. Laydon, S. Velankar, G. J. Kleywegt, A. Bateman, R. Evans, A. Pritzel, M. Figurnov, O. Ronneberger, R. Bates, S. A. A. Kohl, A. Potapenko, A. J. Ballard, B. Romera-Paredes, S. Nikolov, R. Jain, E. Clancy, D. Reiman, S. Petersen, A. W. Senior, K. Kavukcuoglu, E. Birney, P. Kohli, J. Jumper, and D. Hassabis. 2021. “Highly accurate protein structure prediction for the human proteome.” Nature 596 (7873):590–596. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-021-03828-1.

Varadi, M., S. Anyango, M. Deshpande, S. Nair, C. Natassia, G. Yordanova, D. Yuan, O. Stroe, G. Wood, A. Laydon, A. Žídek, T. Green, K. Tunyasuvunakool, S. Petersen, J. Jumper, E. Clancy, R. Green, A. Vora, M. Lutfi, M. Figurnov, A. Cowie, N. Hobbs, P. Kohli, G. Kleywegt, E. Birney, D. Hassabis, and S. Velankar. 2022. “AlphaFold Protein Structure Database: Massively expanding the structural coverage of protein-sequence space with high-accuracy models.” Nucleic Acids Research 50 (D1):D439–D444. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkab1061.

Varadi, M., D. Bertoni, P. Magana, U. Paramval, I. Pidruchna, M. Radhakrishnan, M. Tsenkov, S. Nair, M. Mirdita, J. Yeo, O. Kovalevskiy, K. Tunyasuvunakool, A. Laydon, A. Žídek, H. Tomlinson, D. Hariharan, J. Abrahamson, T. Green, J. Jumper, E. Birney, M. Steinegger, D. Hassabis, and S. Velankar. 2024. “AlphaFold Protein Structure Database in 2024: Providing structure coverage for over 214 million protein sequences.” Nucleic Acids Research 52 (D1):D368–D375. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkad1011.

Volz, E. M., K. Koelle, and T. Bedford. 2013. “Viral phylodynamics.” PLOS Computational Biology 9(3):e1002947. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pcbi.1002947.

Voznica, J., A. Zhukova, V. Boskova, E. Saulnier, F. Lemoine, M. Moslonka-Lefebvre, and O. Gascuel. 2022. “Deep learning from phylogenies to uncover the epidemiological dynamics of outbreaks.” Nature Communications 13 (1):3896. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-022-31511-0.

Wong, F., C. de la Fuente-Nunez, and J. J. Collins. 2023. “Leveraging artificial intelligence in the fight against infectious diseases.” Science 381 (6654):164–170. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.adh1114.

Wong, F., E. J. Zheng, J. A. Valeri, N. M. Donghia, M. N. Anahtar, S. Omori, A. Li, A. Cubillos-Ruiz, A. Krishnan, W. Jin, A. L. Manson, J. Friedrichs, R. Helbig, B. Hajian, D. K. Fiejtek, F. F. Wagner, H. H. Soutter, A. M. Earl, J. M. Stokes, L. D. Renner, and J. J. Collins. 2024. “Discovery of a structural class of antibiotics with explainable deep learning.” Nature 626 (7997):177–185. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-023-06887-8.

Wrapp, D., N. Wang, K. S. Corbett, J. A. Goldsmith, C. L. Hsieh, O. Abiona, B. S. Graham, and J. S. McLellan. 2020. “Cryo-EM structure of the 2019-nCoV spike in the prefusion conformation.” bioRxiv. https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.02.11.944462.

Zost, S. J., P. Gilchuk, R. E. Chen, J. B. Case, J. X. Reidy, A. Trivette, R. S. Nargi, R. E. Sutton, N. Suryadevara, E. C. Chen, E. Binshtein, S. Shrihari, M. Ostrowski, H. Y. Chu, J. E. Didier, K. W. MacRenaris, T. Jones, S. Day, L. Myers, F. Eun-Hyung Lee, D. C. Nguyen, I. Sanz, D. R. Martinez, P. W. Rothlauf, L.-M. Bloyet, S. P. J. Whelan, R. S. Baric, L. B. Thackray, M. S. Diamond, R. H. Carnahan, and J. E. Crowe. 2020. “Rapid isolation and profiling of a diverse panel of human monoclonal antibodies targeting the SARSCoV-2 spike protein.” Nature Medicine 26 (9):1422–1427. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41591-020-0998-x.