The Age of AI in the Life Sciences: Benefits and Biosecurity Considerations (2025)

Chapter: 2 Design-Build-Test-Learn: Impact of AI on the Synthetic Biology Process

2

Design-Build-Test-Learn: Impact of AI on the Synthetic Biology Process

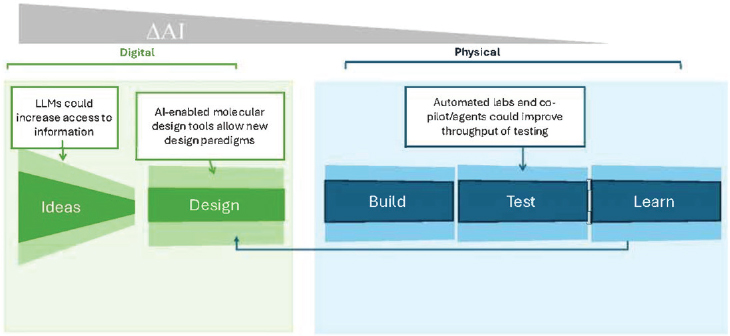

Artificial intelligence (AI)–enabled biological tools can enhance research and design across the various disciplines in the life sciences. Appendix A provides a more detailed discussion of current capabilities and limitations of AI models in biological applications. This chapter presents a broad overview of the impact of AI in synthetic biology and three areas of future development—scientific large language models (LLMs), automated laboratories, and synthetic datasets—that have the potential to accelerate biological design and discovery by improving biological models.

In synthetic biology, the Design-Build-Test-Learn (DBTL) cycle is an iterative approach for designing, constructing, and evaluating biological systems with a built-in feedback loop for refining designs based on experimental data (see Figure 2-1). Ideation or hypothesis generation typically precedes design. The design phase defines the conceptual plan, describes how to achieve the desired output, and can utilize computational modeling tools. AI-enabled biological tools can accelerate ideation and design significantly by providing data-driven insights, discovering patterns in large datasets, and generating novel ideas and design. For example, in drug discovery applications such tools can generate thousands of molecules as potential candidates in days (Chan et al., 2019; Melo, Maasch, and de la Fuente-Nunez, 2021; Food and Drug Administration, 2023; Ren et al., 2024), a feat that would probably take years for researchers.

The build phase is the key point in the DBTL cycle, where digital outputs transition to physical implementation. During the test phase, designed agents are evaluated for whether they behave as expected. During these

phases, automated laboratories can improve efficiency and throughput significantly, but there are challenges, as will be discussed below. Extracting data from build and test to refine and optimize design in the learn phase allows for continuous improvement and knowledge generation. The iterative process of DBTL accounts for the inherent variability of biological systems and highlights the necessity of coupling AI-driven design or modeling with experimental validation.

IDEATION AND DESIGN: LARGE LANGUAGE MODELS AND FOUNDATION MODELS

Thanks to their scaling properties (Hoffmann et al., 2022) and in-context learning (Garg et al., 2024), LLMs are now approaching trillions of learnable parameters. LLMs have made significant advances in natural language understanding and generation, as demonstrated by their increasing performance on benchmark tasks such as language modeling, machine translation, and answering questions (Kumar et al., 2021; Xie et al., 2022; Yue, Yao, and Sun, 2022). Despite existing and well-publicized challenges on staying true to a corpus of knowledge and reducing hallucinations, LLMs are powering valuable tools for knowledge acquisition and idea generation. While most widely known commercial LLM-enabled platforms, such as chatbots, focus on natural language understanding and generation,

researchers are building interactive platforms to advance discovery in specific scientific disciplines or domains.

One category, commonly referred to as “LLMs for science,” is being developed at an increasing pace to help students and researchers quickly grasp key concepts and findings over vast amounts of literature in a particular discipline or across disciplines; interpret complex scientific data to support the discovery process; and, more importantly, assist and guide the generation of scientific hypotheses (Birhane et al., 2023). LLM-assisted ideation goes beyond simple question-answering grounded in a particular domain such as Alphabet’s Med-PaLM 2 for medicine.1 An exemplar of a scientific LLM is CRISPR-GPT, an LLM for the automated design of gene-editing experiments (Huang et al., 2024). LLM-enabled ideation assistants/agents are growing. A non-exhaustive list includes ChemCrow, assisting with planning and executing chemical synthesis procedures (Bran et al., 2024); BioGPT, trained on biomedical literature to assist in biomedical research and ideation (Luo et al., 2022); MatSciBERT, trained on materials science literature to aid in materials discovery and research (Gupta et al., 2022); AstronomyGPT, trained on astronomical data and literature to assist in astrophysics research and hypothesis generation (Ciucă et al., 2023); and ClimateGPT, helping researchers analyze climate data and generate research ideas (Thulke et al., 2024).

While building powerful LLMs currently remains within the reach of only a few companies and countries, two core capabilities may continue to fuel the rise of LLM-enabled ideation assistants: (1) many companies, such as Meta, are releasing their LLMs and sharing model functional characteristics but not the details of the training process or training data; and (2) LLMs are examples of foundation models that learn representations of the input data in a task-agnostic manner through a process referred to as pretraining. Although LLMs are pretrained over large nonspecific datasets as foundation models, LLMs can be further refined in capabilities and performance in a specialized task or domain through continued training, fine-tuning, and instruction tuning.

How well do current ideation assistants perform? Evaluating LLMs as ideation assistants is challenging as it is an emerging area of research with no clear benchmarks. Anecdotal evidence tends to be positive. For instance, Si, Yang, and Hashimoto (2024) demonstrated that LLMs can generate research ideas consistently rated as more novel than those produced by 100 experts, but the ideas lacked depth.

___________________

1 Big tech and start-ups, such as Alphabet, Kili Technology, and others, are counting on an increasing need by researchers for domain-specific LLMs for quick knowledge acquisition and ideation.

On the other hand, there are concerns that an actor may exploit general LLMs for harmful intentions, such as providing guidance to create a bioweapon, and in turn lower the level of expertise needed. A recent study investigated the dual-use potential of chatbots by having students prompt chatbots for information related to creating a pathogen (Soice et al., 2023). However, prompts to the chatbot were highly guided and detailed, and they potentially contained the very information requested.

Rigorous analysis over planning problems indicates that current LLMs cannot reason well (Kambhampati, 2024). Reasoning is key to planning out a recipe or scientific protocol and so is central to effective ideation. However, reasoning capabilities of LLMs are growing (see GPT-4o2), and LLM-modulo frameworks that include external verifiers may provide a path forward (Kambhampati et al., 2024). In the future, LLM-enabled assistants may be capable of being real reasoning partners, representing a transformative point for scientific discovery.

Yet, developing general LLMs remains a challenge owing to the computational cost to power them. While this cost can be circumvented by researchers fine-tuning already pretrained models, there is another computational cost in deployment. An active area of research seeks alternative non-transformer-based architectures to lower both costs. State space models, such as S4 (Gu, Goel, and Ré, 2022), S5 (Smith, Warrington, and Linderman, 2023), Mamba (Gu and Dao, 2024), Hawk (De et al., 2024), and others, constitute a particular category of efficient recurrent networks that promise linear-time pretraining and constant-cost inference, with capabilities approaching those of transformer-based models (Blouir et al., 2024).

Confining LLMs to text or ideation, however, misses a big part of the picture and their true potential. Growing research in bioinformatics and cheminformatics leverages sequential representations of biological entities in a way that can be used by computational tools and LLMs to generate new proteins and new small molecules. For example, the Simplified Molecular Input Line Entry System is used to represent chemical structures (Hunter, Culver, and Fitzgerald, 1987). It is worth noting that the research advances foundation models, which are architecture-agnostic; that is, the models are not restricted to transformer-based architectures but rather are inclusive of other generative architectures, such as those based on variational autoencoders, generative adversarial networks, diffusion models, and others.

In addition, foundation models can be trained to learn information from multiple types of data. DALL-E, for instance, is an example of a foundation model that is trained over two data modalities, text and images.3

___________________

2 See https://openai.com/index/hello-gpt-4o/ and https://openai.com/index/learning-to-reason-with-llms/ (accessed November 12, 2024).

3 See https://openai.com/index/dall-e-2/ (accessed November 12, 2024).

Sora is another example, trained over text and video data.4 Indeed, foundation models trained over multiple data modalities promise to revolutionize scientific discovery and present an emerging area of research (see Appendix A). A non-exhaustive list illustrates this point:

- IsoFormer is a multimodal foundation model that learns over DNA, RNA, and proteins to predict how multiple RNA transcript isoforms originate from the same gene and map to different transcription expression levels across various human tissues (Garau-Luis et al., 2024).

- IBM’s Biomedical Foundation Models5 include foundation models for identifying novel diagnostic and therapeutic target discovery (trained over DNA, bulk RNA, single-cell RNA expression data, and other cell-level signaling information); foundation models for biologics discovery, which further integrate protein sequences, protein complex structures, and protein–protein complex binding free energies; and various small molecule models trained over multiple representations of small molecules to advance drug discovery.

- Many foundation models are being advanced for medical imaging and pathology, including multimodal AI systems for outcomes prediction in precision oncology, trained over textual and image data (Truhn et al., 2024).

In principle, foundation models can be trained over diverse sets of multi-omics6 data and combine ideation and biological design, but many challenges remain for developing multimodal models, including data size, data sparsity across modalities, and data fidelity. For natural language processing, the scaling laws demand very large training datasets (Hoffman et al., 20227). It is possible that advancements in architectures and training procedures may lower data demands to facilitate the development of multimodal foundation models that can incubate both ideation and design internally.

___________________

4 See https://openai.com/index/sora/ (accessed November 12, 2024).

5 See https://research.ibm.com/projects/biomedical-foundation-models (accessed November 12, 2024).

6 Multi-omics refers to “combined information derived from data, analysis, and interpretation of multiple omics measurement technologies to identify or analyze the roles, relationships, and functions of biomolecules (including nucleic acids, proteins, and metabolites) that make up a cell or cellular system. Omics are disciplines in biology that include genomics, transcriptomics, proteomics, and metabolomics.” See https://www.nist.gov/bioscience/nist-bioeconomy-lexicon#multiomic-information.

7 The Chinchilla scaling laws in Hoffman and colleagues (2022) suggest that for compute-optimal training, the number of model parameters and the number of training tokens should scale at approximately equal rates. This is typically operationalized as a ratio of about 20 tokens per parameter.

Provided that these challenges are surmountable, multimodal foundation models have the potential to be a one-stop shop, such that one interacts with a master AI agent rather than patching single-task AI agents. Advancing this analogy, multimodal foundation models hold great potential to operationalize ideation to actual biological design. Currently, however, one-stop-shop models are out of reach owing to computational cost and data requirements as well as the sophistication needed to build them.

BUILD AND TEST: AUTOMATED LABORATORIES

Today, applications of bioengineering require many successive DBTL cycles to yield a biological design that meets the desired performance target. To increase the probability of success and reduce the total amount of time and cost it takes to develop a successful design, automation is often used to perform build and test activities. Facilities that automate design-build-test cycles for synthetic biology are commonly referred to as foundries, in reference to foundries that fabricate silicon chips (Hillson et al., 2019).

While the automation used in foundries has become significantly more advanced, foundries vary in their capabilities and are often designed for specific purposes (e.g., assembly of large DNA molecules, microbial engineering to produce a useful product, or mammalian cell engineering). Foundries are now being leveraged to generate datasets for AI training, the results of which can be used to curate new datasets that improve model performance. This “lab in the loop” approach promises to accelerate AI model development, which in turn could reduce the number of DBTL cycles needed to realize a successful design. Additionally, this combination of automated laboratories with AI may address the need to generate vast biological datasets broadly by using the generated data to further refine AI models in the iterative DBTL cycle.

The concept of lab in the loop involves AI-driven experimental design and automation of the build and test work. This raises the concern that fully automated foundries could lower the intensive requirements of build and test and be co-opted by malicious actors to develop harmful products. However, the full suite of activities needed to design, build, and test in automated or fully “self-driving laboratories” is a future capability that at present has significant challenges. Currently, foundries are typically application-specific and resource-intensive, and they require a large amount of human input and capital investment (Martin et al., 2023).

LEARN: SYNTHETIC DATA

Training AI models on synthetic data is an increasingly appealing proposition in several application domains where data scarcity and potential

privacy and ethical considerations are key concerns. Synthetic data refers to artificial data that are generated to mimic real-world data. In biology, future developments may lead to improvements of biological models from incorporating synthetic data as training data, but more work is needed. Biological processes are physics-driven dynamic processes, and no amount of wet-lab data will sufficiently capture all aspects of a physics-based process as it unfolds across disparate spatiotemporal scales. Synthetic data, such as those obtained from Monte Carlo or molecular dynamics physics–based simulations, may fill in the gaps of experimentally derived data. However, model collapse, defined as the decrease in performance from using synthetic data generated from one machine learning model in another machine learning model, may occur (Shumailov et al., 2024).

Future developments in LLMs, automated laboratories, and the use of synthetic data to train models represent a few areas to monitor for increases in AI-enabled biological capabilities.

REFERENCES

Birhane, A., A. Kasirzadeh, D. Leslie, and S. Wachter. 2023. “Science in the age of large language models.” Nature Reviews Physics 5 (5):277–280. https://doi.org/10.1038/s42254-023-00581-4.

Blouir, S., J. T. H. Smith, A. Anastasopoulos, and A. Shehu. 2024. “Birdie: Advancing state space models with reward-driven objectives and curricula.” arXiv. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2411.01030.

Bran, M. A., S. Cox, O. Schilter, C. Baldassari, A. D. White, and P. Schwaller. 2024. “Augmenting large language models with chemistry tools.” Nature Machine Intelligence 6 (5):525–535. https://doi.org/10.1038/s42256-024-00832-8.

Chan, H. C. S., H. Shan, T. Dahoun, H. Vogel, and S. Yuan. 2019. “Advancing drug discovery via artificial intelligence.” Trends in Pharmacological Sciences 40 (8):592–604. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tips.2019.06.004.

Ciucă, I., Y.-S. Ting, S. J. Kruk, and K. G. Iyer. 2023. “Harnessing the power of adversarial prompting and large language models for robust hypothesis generation in astronomy.” arXiv. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2306.11648.

De, S., S. L. Smith, A. Fernando, A. Botev, G. Cristian-Muraru, A. Gu, R. Haroun, L. Berrada, Y. Chen, S. Srinivasan, G. Desjardins, A. Doucet, D. Budden, Y. W. Teh, R. Pascanu, N. D. Freitas, and C. Gulcehre. 2024. “Griffin: Mixing gated linear recurrences with local attention for efficient language models.” arXiv. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2402.19427.

Food and Drug Administration. 2023. Using Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning in the Development of Drug and Biological Products. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. https://www.fda.gov/media/167973/download.

Garau-Luis, J., P. Bordes, L. Gonzalez, M. Roller, B. Almeida, L. Hexemer, C. Blum, S. Laurent, J. Grzegorzewski, M. Lang, T. Pierrot, and G. Richard. 2024. “Multi-modal transfer learning between biological foundation models.” arXiv. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2406.14150v1.

Garg, S., D. Tsipras, P. Liang, and G. Valiant. 2024. “What can transformers learn in-context? A case study of simple function classes.” Proceedings of the 36th International Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems, New Orleans, LA, November 28-December 9, 2022. https://doi.org/10.5555/3600270.3602487.

Gu, A., and T. Dao. 2024. “Mamba: Linear-time sequence modeling with selective state spaces.” arXiv. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2312.00752.

Gu, A., K. Goel, and C. Ré. 2022. “Efficiently modeling long sequences with structured state spaces.” arXiv. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2111.00396.

Gupta, T., M. Zaki, N. M. A. Krishnan, and Mausam. 2022. “MatSciBERT: A materials domain language model for text mining and information extraction.” npj Computational Materials 8 (1):102. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41524-022-00784-w.

Hillson, N., M. Caddick, Y. Cai, J. A. Carrasco, M. W. Chang, N. C. Curach, D. J. Bell, R. Le Feuvre, D. C. Friedman, X. Fu, N. D. Gold, M. J. Herrgård, M. B. Holowko, J. R. Johnson, R. A. Johnson, J. D. Keasling, R. I. Kitney, A. Kondo, C. Liu, V. J. J. Martin, F. Menolascina, C. Ogino, N. J. Patron, M. Pavan, C. L. Poh, I. S. Pretorius, S. J. Rosser, N. S. Scrutton, M. Storch, H. Tekotte, E. Travnik, C. E. Vickers, W. S. Yew, Y. Yuan, H. Zhao, and P. S. Freemont. 2019. “Building a global alliance of biofoundries.” Nature Communications 10 (1):2040. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-019-10079-2.

Hoffmann, J., S. Borgeaud, A. Mensch, E. Buchatskaya, T. Cai, E. Rutherford, D. d. L. Casas, L. A. Hendricks, J. Welbl, A. Clark, T. Hennigan, E. Noland, K. Millican, G. van den Driessche, B. Damoc, A. Guy, S. Osindero, K. Simonyan, E. Elsen, O. Vinyals, J. W. Rae, and L. Sifre. 2022. “Training compute-optimal large language models.” arXiv. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2203.15556.

Huang, K., Y. Qu, H. Cousins, W. A. Johnson, D. Yin, M. Shah, D. Zhou, R. Altman, M. Wang, and L. Cong. 2024. “CRISPR-GPT: An LLM agent for automated design of gene-editing experiments.” bioRxiv 2024.04.25.591003. https://doi.org/10.1101/2024.04.25.591003.

Hunter, R. S., F. D. Culver, and A. Fitzgerald. 1987. SMILES User Manual. A Simplified Molecular Input Line Entry System. Bozeman, MT: Montana State University, Institute for Biological and Chemical Process Control.

Kambhampati, S. 2024. “Can large language models reason and plan?” Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences 1534 (1):15–18. https://doi.org/10.1111/nyas.15125.

Kambhampati, S., K. Valmeekam, L. Guan, K. Stechly, M. Verma, S. Bhambri, L. Saldyt, and A. Murthy. 2024. “LLMs can’t plan, but can help planning in LLM-modulo frameworks.” arXiv. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2402.01817.

Kumar, S., A. Anastasopoulos, S. Wintner, and Y. Tsvetkov. 2021. “Machine translation into low-resource language varieties.” Proceedings of the 59th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics and the 11th International Joint Conference on Natural Language Processing 2:110–121. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2106.06797.

Luo, R., L. Sun, Y. Xia, T. Qin, S. Zhang, H. Poon, and T.-Y. Liu. 2022. “BioGPT: Generative pre-trained transformer for biomedical text generation and mining.” Briefings in Bioinformatics 23 (6). https://doi.org/10.1093/bib/bbac409.

Martin, H. G., T. Radivojevic, J. Zucker, K. Bouchard, J. Sustarich, S. Peisert, D. Arnold, N. Hillson, G. Babnigg, J. M. Marti, C. J. Mungall, G. T. Beckham, L. Waldburger, J. Carothers, S. Sundaram, D. Agarwal, B. A. Simmons, T. Backman, D. Banerjee, D. Tanjore, L. Ramakrishnan, and A. Singh. 2023. “Perspectives for self-driving labs in synthetic biology.” Current Opinion in Biotechnology 79:102881. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.copbio.2022.102881.

Melo, M. C. R., J. R. M. A. Maasch, and C. de la Fuente-Nunez. 2021. “Accelerating antibiotic discovery through artificial intelligence.” Communications Biology 4 (1):1050. https://doi.org/10.1038/s42003-021-02586-0.

Ren, F., A. Aliper, J. Chen, H. Zhao, S. Rao, C. Kuppe, I. V. Ozerov, M. Zhang, K. Witte, C. Kruse, V. Aladinskiy, Y. Ivanenkov, D. Polykovskiy, Y. Fu, E. Babin, J. Qiao, X. Liang, Z. Mou, H. Wang, F. W. Pun, P. Torres-Ayuso, A. Veviorskiy, D. Song, S. Liu, B. Zhang, V. Naumov, X. Ding, A. Kukharenko, E. Izumchenko, and A. Zhavoronkov. 2024. “A small-molecule TNIK inhibitor targets fibrosis in preclinical and clinical models.” Nature Biotechnology. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41587-024-02143-0.

Shumailov, I., Z. Shumaylov, Y. Zhao, N. Papernot, R. Anderson, and Y. Gal. 2024. “AI models collapse when trained on recursively generated data.” Nature 631 (8022):755–759. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-024-07566-y.

Si, C. S., D. Yang, and T. Hashimoto. 2024. “Can LLMs generate novel research ideas? A large-scale human study with 100+ NLP researchers.” arXiv. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2409.04109.

Smith, J. T. H., A. Warrington, and S. W. Linderman. 2023. “Simplified state space layers for sequence modeling.” arXiv. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2208.04933.

Soice, E. H., R. Rocha, K. Cordova, M. Specter, and K. M. Esvelt. 2023. “Can large language models democratize access to dual-use biotechnology?” arXiv. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2306.03809.

Thulke, D., Y. Gao, P. Pelser, R. Brune, R. Jalota, F. Fok, M. Ramos, I. van Wyk, A. Nasir, H. Goldstein, T. Tragemann, K. Nguyen, A. Fowler, A. Stanco, J. Gabriel, J. Taylor, D. Moro, E. Tsymbalov, J. de Waal, E. Matusov, M. Yaghi, M. Shihadah, H. Ney, C. Dugast, J. Dotan, and D. Erasmus. 2024. “ClimateGPT: Towards AI synthesizing interdisciplinary research on climate change.” arXiv. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2401.09646.

Truhn, D., J.-N. Eckardt, D. Ferber, and J. N. Kather. 2024. “Large language models and multimodal foundation models for precision oncology.” npj Precision Oncology 8 (1):72. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41698-024-00573-2.

Yue, X., Z. Yao, and H. Sun. 2022. “Synthetic question value estimation for domain adaptation of question answering.” Proceedings of the 60th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics 1:1340–1351. Dublin, Ireland: Association for Computational Linguistics.