The Age of AI in the Life Sciences: Benefits and Biosecurity Considerations (2025)

Chapter: 5 Importance of Data in AI-Enabled Biological Models

5

Importance of Data in AI-Enabled Biological Models

Artificial intelligence (AI)–enabled biological tools are likely to continue to require data-driven AI methods that learn patterns from large biological datasets, because the underlying rules of the types of biology being discussed in this report are generally unknown. This contrasts with AI systems that play and win difficult games with superhuman performance, such as chess (Campbell, Hoane, and Hsu, 2002) and Go (Silver et al., 2017), where the rules of the games are fully known and can be used to improve AI systems without additional data. Our recommendations on the importance of generating accessible high-quality biological data with robust data provenance are derived from three key properties commonly found in data-driven AI systems:

- Risky data are hard to define. It is difficult to determine which aspects of training data (i.e., features) cause deep neural networks to make predictions (Ras et al., 2022). As a result, it is not feasible to a priori identify targeted biological data points that, if specifically excluded from training, would prevent AI from making certain kinds of risky predictions (e.g., increased viral virulence) while still enabling related beneficial predictions (e.g., lack of pathogenicity of viral vector vaccines). The main option is to exclude large swaths of data from training.

- State-of-the-art AI uses all available data. The most competitive AIs, including those for clinical decision support (Singhal et al., 2023) and code generation (Du et al., 2024), are built using foundation models trained on enormous volumes of general data (e.g.,

- text, images, genomic) and then specialized to certain domains using techniques such as fine-tuning, prompt engineering, and model distillation. A biosecurity approach based on restricting large swaths of data from AI training is more likely to hinder research and is impractical given that model capabilities are reliant on the data.

- High-quality data are a strategic national asset. Data-driven AI requires trusted high-quality data to be effective, as witnessed by recent breakthroughs ranging from protein folding AI trained on Protein Data Bank (PDB) data to digital pathology AI for identifying infectious diseases trained on curated clinical datasets (Smith and Kirby, 2020; Jiao et al., 2021; Xu, Liu, et al., 2024). The availability of high-quality datasets with ensured data integrity will help maximize the benefits of AI-driven biosurveillance and faster medical countermeasure (MCM) design.

BIOLOGICAL DATASETS FOR TRAINING AI MODELS

As previously noted, publicly available and accessible data are necessary to train AI models. The accessibility of data follows a continuum from freely available and in the public domain to highly classified information—with several options in between. Guidance for federally funded research data advocates for data deposition in repositories that meet the criteria established in the report, Desirable Characteristics of Data Repositories for Federally Funded Research. These criteria include openness “consistent with legal and policy requirements related to maintaining privacy and confidentiality, Tribal and national data sovereignty, and protection of sensitive data,” as well as appropriate cybersecurity policies to prevent “unauthorized access to, modification of, or release of data, with levels of security that are appropriate to the sensitivity of data (e.g., the NIST [National Institute of Standards and Technology] Cybersecurity Framework1)” (Subcommittee on Open Science of the National Science and Technology Council, 2022). The guidance is meant to provide a balance of accessibility and security in recognition of the importance of data as a public good with dual-use potential. Data generated and funded by private entities have no requirement for submission to national repositories. The security of these data is the responsibility of the private entity.

The Findable, Accessible, Interoperable, and Reusable (FAIR) principles established by Wilkinson and colleagues (2016) serve as aspirational guidelines to the data management community for creating and maintaining data resources that are machine-accessible. Data can be FAIR while implementing

___________________

1 See https://www.nist.gov/cyberframework (accessed January 6, 2025).

access controls and use restrictions in accordance with federal guidelines. The data management community has improved data FAIRness through increased adoption of persistent identifiers, standardized authentication protocols, and metadata standardization. As repositories converge on common standards and ontologies, the interoperability of data from different studies improves, making data more machine-accessible and AI-ready. However, FAIR does not mean that all data are open or immediately accessible to humans or machines. Furthermore, as our understanding of biological data improves and new measurements are possible, the data models and standards as well as the policies must evolve to accommodate this new understanding.

Evolution of Biological Data Access Policy at the National Institutes of Health

Many factors influence the extent to which information is available—some are driven by organizational policy and others are driven by legal constraints, but all are consistent with the FAIR principles. In 2003, the National Institutes of Health (NIH) established a data-sharing policy that required a data-sharing or management plan for any researcher seeking more than $500,000 in direct costs. However, researchers could seek exemptions for concerns over biosafety or national security. Also, any identifiable information had to be stripped from data related to research involving human subjects. After the final data-sharing policy, as high-throughput genome sequencing became a reality, NIH published the Policy for Sharing of Data Obtained in NIH Supported or Conducted Genome-Wide Association Studies (GWAS) in 2007,2 which lowered the funding threshold from $500,000 to $0. In other words, NIH indicated that as much data as possible created through public tax dollars should be put into the public domain, in large part due to the rise of fraudulent publications that were accepted to high-impact journals but not reproducible. Thus, while it could be argued that NIH has pushed for public data sharing to speed up scientific investigation, it could also be argued that it has done this to address the reproducibility crisis in science. If investigators did not have a clear plan for sharing genomic data, their data can be sent to the Database of Genotypes and Phenotypes (dbGaP), which would curate and redistribute the data on behalf of the investigators.

After the GWAS policy, NIH released the Genomic Data Sharing (GDS) Policy in 2014.3 This policy was due to new advances in sequence gen-

___________________

2 See https://grants.nih.gov/grants/guide/notice-files/not-od-07-088.html (accessed January 2, 2025).

3 See https://grants.nih.gov/grants/guide/notice-files/NOT-OD-14-124.html and https://sharing.nih.gov/genomic-data-sharing-policy/about-genomic-data-sharing/gds-policy-overview (accessed January 2, 2025).

eration capabilities. This time, whole exome sequencing and whole genome sequencing became (relatively) cost-effective. NIH recognized that the GWAS policy was a bit myopic because it focused mainly on basic variants and their associations with phenotypic expression as opposed to simply the entirety of the genome. Thus, the GDS policy aimed to resolve this issue. However, it should be recognized that both the GWAS and GDS policies indicated that data should be made available in a manner that was de-identified.

Many of the policies that have been set forth by NIH and the infrastructure that has been set up to manage biomedical data have focused on data derived from humans. The GWAS and GDS policies, for instance, are concerned mainly about human privacy and not about biosafety issues that could arise from the sharing of bacterial or viral data and their impact on human cell lines. That said, NIH has recognized that there are many ethical questions regarding the sharing of infectious disease data, and one of the core components of NIH’s soon-to-be-initiated Human Virome Project relates to the ethical, legal, and social implications regarding the collection and sharing of such data.4

INFRASTRUCTURE AND GOVERNANCE

Agencies establish policies for data governance that dictate access controls. For example, while NIH wants genomic data to be made accessible to the public, it requires a legitimate scientific reason for the use of data derived from humans. Thus, to access data at dbGaP, investigators need to submit a request for access because dbGaP only serves as a repository of the data. NIH did not stand up an analytic workbench to allow people to interact with the hundreds of datasets that were submitted. Moreover, since dbGaP is a federal repository, the Data Access Committee that determined who got access based on their requests was composed solely of federal employees. This was not well received by the research community broadly because it takes the academic community (and commercial communities, if they contributed data) out of the decision-making equation. This was a particular concern because requests for data came from all over the world, and it was unclear whether investigators wanted data on U.S. residents to be shared with foreign entities.

By contrast, the NIH’s All of Us Research Program has a different access framework. Rather than serve as only a repository, the program aimed to create a cloud-backed analytic workbench. In doing so, the All of Us Research Program chose to sandbox the data, wherein researchers would be able to access and investigate the data using various programming

___________________

languages, such as Python, R, and SAS, but would not be permitted to take individual-level data out of the environment. Further, unlike dbGaP, the All of Us Research Program took a different approach than the traditional Data Access Committee model for dbGaP, which required a review for every request of data—including when two different requests came from the same investigator. Specifically, the All of Us Research Program adopted the passport model (Dyke et al., 2018), which worked on a trust model based more on the credentials of the user than on how the data were used. Thus, the All of Us Research Program requires

- institutions associated with where a user originates to enter into a contractual agreement that takes responsibility for their actions (as of December 2024, there were 1,0385);

- users to take a series of courses or trainings regarding what they are expected to do (and not do) with the data they are provided access to and pass an examination;6

- users to accept a data user code of conduct7 in which they agree not to perform stigmatizing research or attempt to re-identify the participants8 in the program; and

- users to create a new workspace and a public description of the work that they are doing for every study that they do (to comply with the 21st Century Cures Act9), unlike the access request, which only occurs once.

In addition, the All of Us Research Program data are structured in a tiered manner, such that data deemed less risky in regard to privacy or sensitivity are made available in the Registered Tier,10 while whole genome sequencing data and potentially more private and sensitive data are in the Controlled Tier. Xia and colleagues (2023) provide details on how re-identification risk is assessed and managed. Further documentation on how All of Us provisions access is provided by Mayo et al. (2023).

Still the All of Us Research Program data access model creates some limitations with respect to training and developing AI models. At present, the All of Us Research Program does not allow its data to be used to

___________________

5 See https://www.researchallofus.org/institutional-agreements/ (accessed January 8, 2025).

6 See https://support.researchallofus.org/hc/en-us/articles/6088597693716-All-of-Us-Onboarding-Tutorial-Video (accessed January 8, 2025).

7 See https://www.researchallofus.org/faq/data-user-code-of-conduct/ (accessed January 8, 2025).

8 “Participants” in this case indicates consented research volunteers.

9 21st Century Cures Act of 2016, Pub. L. No. 114-255, 130 Stat. 1033.

10 See https://support.researchallofus.org/hc/en-us/articles/4552681983764-How-All-of-Us-protects-participant-privacy (accessed January 8, 2025).

fine-tune or train external foundation models or machine learning models more generally. This restriction stems from concerns of losing control over the data. As such, while a researcher can build a machine learning model within the All of Us Research Program sandboxed workbench, the model cannot be taken out of the workbench. This may change in the future, but it demonstrates why the All of Us Research Program model may not be a suitable example for data governance in considering the various types of biological datasets used to train AI models. Nevertheless, the program is an appropriate case study for how the entire workflow, from the data to the AI-enabled tool to all user interactions with the tool, can be sandboxed and managed accordingly if required. In many respects, this would be analogous to an access-controlled version of AlphaFold.

THE DATA LIFE CYCLE AND NATIONAL REPOSITORIES

Data have a life cycle that is generally composed of the following stages: plan and design, collect and create, analyze and collaborate, evaluate and archive, share and disseminate, and publish and reuse (see Figure 5-1). The various stages inform each other and future experiments. How data are captured and preserved has a critical impact on their integrity and the subsequent validity of AI. Once data and the corresponding contextual information (labels) are available in machine-readable formats, many powerful computational and statistical techniques can be utilized to identify patterns, make predictions, and advance scientific understanding.

The core of the data life cycle is storage and data management, as a long-term home and effective management policies are critical to maximizing the value of a dataset. The data life cycle connects to the AI layer and its associated software life cycle wherever data are used (reuse) or models or data are generated (collect and create). The experimental design or plan impacts the data that are collected and made available for training or building AI because at this stage, the scientist must gather enough contextual information to inform future data reuse. The contextual information links data collected in one experiment to another and builds the necessary connective tissue for large-scale statistical analyses.

National repositories are a valuable resource for scientific progress and AI-driven innovation due to federal investments in curated public databases. The creation, curation, and preservation of national repositories require significant long-term investments in laboratory and computing infrastructure capacity as well as subject matter expertise.

Beyond data storage and management systems with strong data provenance, U.S. federal research funding agencies such as NIH, Advanced Research Projects Agency for Health, Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA), National Science Foundation (NSF), U.S. Department

SOURCE: Longwood Medical Area Research Data Management Working Group, 2024, under Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial 4.0 International License.

of Energy (DOE), and others should fund AI hardware infrastructure so the research community can competitively develop next-generation AI-enabled biological tools that are specifically trained on biological data and focused on biological capabilities. Many researchers lack access to the necessary data, computing, and educational resources to fully leverage or develop AI for biological R&D, including medical countermeasure development.

In order to build AI applications, it is essential to have infrastructure connecting data repositories with the high-performance computing hardware needed to train models, compute inference, and then store those outputs. Many researchers lack access to the necessary data, computing, and educational resources to leverage or develop AI biological models or tools. The National Artificial Intelligence Research Resource (NAIRR) pilot seeks to bring together computational, data, software, model, training, and user support resources as foundational infrastructure for AI research. NAIRR is led by NSF, in partnership with 12 other federal agencies and 26 nongovernmental entities.11 Similarly, DOE is leading the Frontiers in Artificial Intelligence for Science, Security and Technology initiative, offering the connected computing, experimental data generation, and educational infrastructure of the DOE national laboratories to the scientific community to advance AI research. NIH has partnered with cloud vendors to host large repositories such as the Sequence Read Archive (SRA). More than 50 petabytes of raw sequence data are co-located with cloud computing resources that can be used for the development of new tools (Serratus, a cloud computing environment12) or new data resources (Logan, a set of compressed sequencing files for SRA13), provided that the researcher has the budget to conduct the computations. The United States has led research and development (R&D) in high-performance computing for decades, according to the Supercomputing Top 500 List,14 and national investments in AI infrastructure will be essential to maintain U.S. competitiveness in AI.

CONSIDERATIONS FOR BUILDING DATA INFRASTRUCTURE

The recognition of AI and enabling data as national R&D, security, and economic assets has been articulated in various policies and strategic plans, including the September 2024 launch of the interagency Task Force on AI Datacenter Infrastructure15 to promote the development of data center projects and the 2024 National Security Memorandum on AI.

Recommendation: To maximize the benefits of artificial intelligence (AI) in biology, U.S. federal research funding agencies such as the National Institutes of Health, Advanced Research Projects Agency for Health, Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency, National Science

___________________

11 See https://nairrpilot.org/ (accessed November 17, 2024).

12 See https://serratus.io/about (accessed November 17, 2024).

13 See https://registry.opendata.aws/pasteur-logan/ (accessed November 17, 2024).

14 See https://top500.org/lists/top500/ (accessed November 17, 2024).

15 See https://bidenwhitehouse.archives.gov/briefing-room/statements-releases/2024/09/12/readout-of-white-house-roundtable-on-u-s-leadership-in-ai-infrastructure/ (accessed November 17, 2024).

Foundation, U.S. Department of Energy, and others should fund efforts and infrastructures to do the following:

- Create and steward AI-compatible data and training sets for biological applications that are made publicly available;

- Initiate and support public–private partnerships for the generation of training datasets; and

- Develop frontier AI-enabled biological tools that are specifically trained on biological data and focused on biological capabilities.

Recommendation: Federal research agencies that house or fund biological databases should consider these to be strategic assets and concordantly implement robust data provenance mechanisms to maintain the highest data quality. They should provide strong incentives and infrastructure for the standardization, curation, integration, and continuous maintenance of high-quality, publicly accessible biological data at scale.

Recommendation: While a public–private partnership is a reasonable approach to pilot the creation of an artificial intelligence (AI)–ready data resource on government-owned infrastructure, a dedicated organization is central to a sustainable national data stewardship resource. The National Artificial Intelligence Research Resource (NAIRR) pilot should explore approaches for establishing central repositories for training AI models.

PROTECTING DATA ASSETS FOR AI-ENABLED BIOLOGICAL R&D

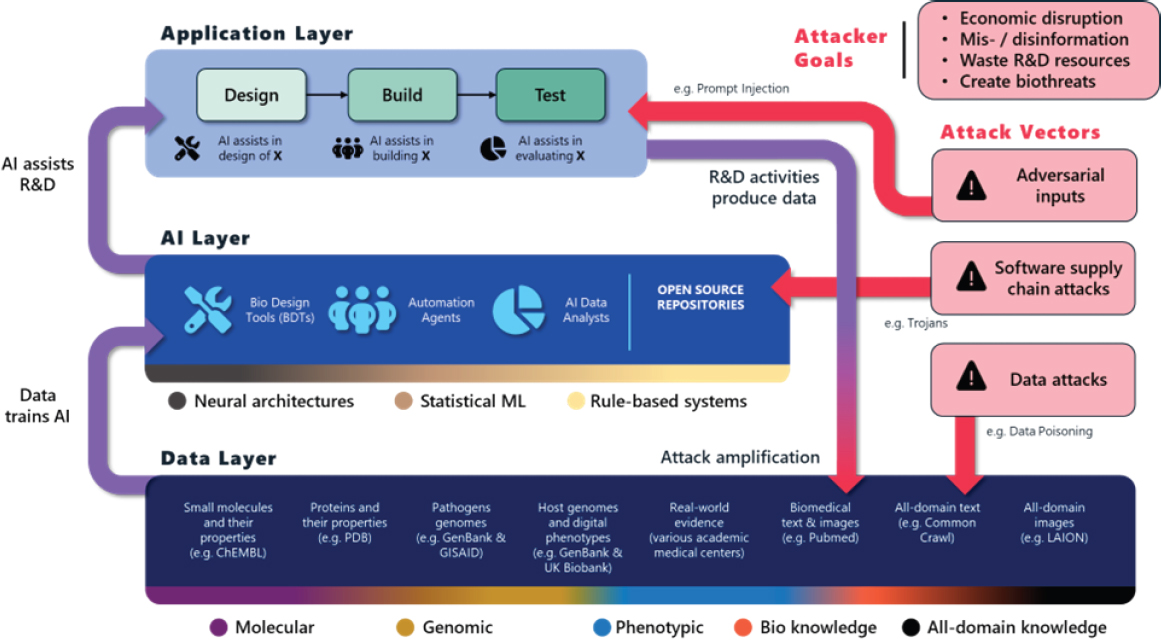

To maintain high-quality and secure national data assets for AI-enabled biological R&D, it is crucial to understand how data flow into AI software and how AI software is used across the design, build, and test stages. Figure 5-2 summarizes the relationships between these layers and the locations of potential vulnerabilities at the data, AI software, and application layers.

- The Data Layer shows key datasets used to train AI applied to biology (and beyond). This layer is highly heterogeneous, is decentralized, and includes general text and images mined from the broader internet, creating opportunities to manipulate the biological R&D process by manipulating the data used to train AI (Shan et al., 2024).

- The AI Layer highlights many sophisticated forms of AI that are relevant for biological R&D, and these are implemented using a large corpus of open-source software (at least 55% of PubMedCentral–Open Access articles have links to open-source software [Istrate

- et al., 2022]). This exposes the biological R&D ecosystem to software supply chain attacks, including attacks identified by the Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency (2024) as major national security risks, which could be used to manipulate AI software used in biomedical R&D.

- The Application Layer emphasizes that AI technologies are being and will be used across the design, build, and test stages, including biological design tools, automation agents to control equipment or order biological materials and reagents (Bose, 2024), and AI analysts to help interpret clinical data to accelerate clinical trials and improve post-market surveillance (e.g., AI for real-world evidence [Subbiah, 2023]). For example, the drug program was approved to prevent lung transplant rejection based on real-world observational data from its off-label use (Food and Drug Administration, 2021). Vulnerabilities introduced at the lower layers could manifest across the biomedical R&D stages and include difficult-to-mitigate vulnerabilities specific to generative AI (Short, La Pay, and Gandhi, 2019; Gupta et al., 2023).

A final challenge is that both noisy data and intentional corruption are likely to be self-amplifying, because corrupted data generated at the application layer will be added back into the data layer, further corrupting AI that is later trained on them and potentially leading to phenomena such as model collapse (Dohmatob et al., 2024; Shumailov et al., 2024). Maintaining data provenance (i.e., tracking by whom and where in the application layer data were created, recording all the AI tools and software dependencies used to assist in generating novel data, and linking AI tools to the data used to train their models) creates a complete picture of the history of the data. This allows low-quality data to be rejected, enables rapid identification of AI systems that may have been compromised by noisy or intentionally manipulated data, and ensures high-quality data producers can determine how their data were used to train AI. Boxes 5-1, 5-2, and 5-3 give examples of enabling technologies, which are already utilized in adjacent regulated industries, for creating high-quality and secure data assets with strong data provenance.

DATA-DRIVEN VULNERABILITIES AND MITIGATIONS

AI-enabled biological tools bring unique opportunities to biomedical research but may be vulnerable to data corruption. Adversarial attacks exploit vulnerabilities in AI models by introducing small, often imperceptible, perturbations in the input data that can cause the model to make incorrect

predictions. We explore potential attack vectors and possible mitigation strategies to ensure data integrity for use in training models.

Potential Data Vulnerabilities

Data Poisoning and Corruption

Data poisoning is the modification of training data to manipulate the AI model to learn certain patterns or relationships (Jagielski et al., 2018; Yerlikaya and Bahtiyar, 2022). These patterns may be designed to be factually incorrect, to be biased, or to obscure a signal of interest. Data poisoning can be dangerous because small undetected changes in large

datasets can lead to significant errors in model predictions and downstream applications.

In the biomedical domain, AI models often rely on large publicly available datasets, such as gene expression profiles or drug efficacy studies. However, one of the concerns of such a reliance is that there is no guarantee that the data contributed to the public domain have been subject to peer review, and those that have may lack rigorous validation. It is possible that an attacker could publicly disseminate falsified research papers or data, which in turn are mined by AI systems for training data. For instance, an attacker could submit a paper containing slightly altered gene–drug interaction data to a preprint server, where the efficacy of a particular drug is exaggerated.

A more targeted attack could involve altering training data for models that predict protein folding or drug interactions. For instance, a malicious actor could corrupt these data with false protein structures or misleading chemical interaction information, leading an AI system to generate flawed outputs, such as ineffective molecules or incorrect biological pathway predictions. These corrupted outputs could, in turn, derail efforts aimed at medical countermeasures. While these would be caught during the test stage (i.e., preclinical testing and clinical trials), valuable time might be wasted in the context of a rapidly progressing epidemic or pandemic.

Backdoor Attacks

In a backdoor attack (Salem et al., 2022), the adversary introduces a hidden trigger during the training or development of the AI model, such that when a specific input pattern is provided the model produces incorrect or unsafe outputs. A backdoor attack is difficult to detect because it could remain dormant and undetected during normal usage and only be activated under specific conditions.

In this scenario, a public, open-source AI model that is designed to support vaccine discovery could be altered by embedding a backdoor that is activated when the model encounters a specific sequence in a DNA or protein structure.

Jailbreaking Attacks

Jailbreaking attacks involve bypassing the safety mechanisms built into AI models, allowing the system (or user of the system) to perform tasks it was otherwise restricted from doing (Xu, Usuyama, et al., 2024). An actor may also try to exploit the AI’s capabilities by rephrasing requests or breaking down the task into smaller, seemingly benign steps. Instead of directly asking the AI to design a lethal substance, the attacker might ask it to suggest molecules with certain properties (e.g., specific toxicity levels) or find ways to bypass the safety filters by describing the task in vague or scientific terms. Over time, these carefully constructed prompts could lead the AI to generate prohibited outputs, despite the model’s safeguards. Jailbreaking attacks are particularly concerning because they do not require altering the underlying model; rather, they exploit the model’s interpretive processes to circumvent its safety protocols.

Model Fine-Tuning and Instruction Manipulation

In another type of attack, a system user could perform model fine-tuning by injecting malicious data or introducing specific instructions to subtly manipulate the behavior of an AI system. The fine-tuning attack enables an adversary to adjust a pretrained model by retraining it with additional adversarial data, steering it toward incorrect or dangerous outputs. For example, an attacker with access to the model’s training process could fine-tune it to produce misleading information about disease progression, biosurveillance, or genetic and molecular interactions. A model fine-tuned in this manner might falsely predict the effectiveness of a particular drug or incorrectly diagnose the health status of an individual, which could lead to improper—or a lack of—identification of or treatments for an individual who has been exposed to some agent. By subtly altering how the

AI interprets biological data, an attacker could push the model to design ineffective therapies that would waste time in clinical trials, misinform researchers in critical research, or manipulate public trust.

Attackers could fine-tune biomedical models to align with more harmful objectives, such as providing guidance for the creation of dangerous biological agents. For instance, by feeding the AI malicious training data, an adversary could reorient the model to generate synthetic pathways for producing toxic compounds or lethal pathogens (Urbina et al., 2022). This kind of attack could enable the development of bioweapons or hazardous chemicals under the guise of legitimate drug discovery efforts. To be successful in such an attack, the adversary would need access to the model’s training pipeline as well as knowledge of how to craft malicious data that will specifically skew the AI’s responses. This would require a nontrivial level of technical expertise in both machine learning and the relevant biological domain. Moreover, this type of attack would require the capability either to inject harmful data during training or to deceive the AI’s deployment environment. Finally, this type of attack will still encounter significant barriers during the build and test phases.

Mitigation Approaches

Continuous Penetration Testing (Pen Testing)

Regular penetration (or pen) testing involves probing AI models for weaknesses by simulating various attack scenarios. This allows researchers to assess the security of their models continuously and identify potential vulnerabilities before they can be exploited by malicious actors. For biomedical AI, this could involve testing how the model responds to harmful prompts, encoded malicious data, or attempts to bypass its safety mechanisms. Robust pen testing ensures that the AI system remains secure even as new threats emerge.

Robust Training Techniques

AI models need to be trained using well-curated and trusted datasets with strong data provenance to minimize the risk of data poisoning. This involves implementing more stringent data filtering and augmentation processes. Additionally, models should be trained to recognize and reject manipulated inputs that could lead to harmful outputs. Training AI models in adversarial environments—where they are exposed to deliberately corrupted or misleading data—can improve their robustness and resistance to attacks.

Benchmarking for Robustness and Risk Evaluation

Developing standardized benchmarks for evaluating the robustness of biomedical AI models is essential. These benchmarks should assess how well a model can resist various forms of attack, including data corruption, jailbreaking, and backdoor manipulation. Consistent benchmarking ensures that models meet safety standards and can be trusted in high-stakes applications, such as pathogen discovery or drug design.

Regular Model Audits

Auditing AI models at regular intervals can help in identifying back-doors or hidden vulnerabilities that may not be immediately apparent. These audits should involve both automated techniques and manual reviews by experts in AI security and biomedical research. Audits can ensure that any updates or changes to the model do not introduce new vulnerabilities.

Assessment of Large Language Models

General-purpose AI models (e.g., large language models [LLMs] like ChatGPT, Gemini, or Claude) are actively assessed to identify different types of vulnerabilities (e.g., cybersecurity), capabilities (e.g., factuality, persuasion), or unwanted or harmful behaviors (e.g., model responses including personal information, or promoting harm or bias). Different approaches can be used to assess or evaluate AI models like LLMs, including the following, among others:

- Static single-turn, open-ended prompts where human raters rate the responses as problematic or not;

- Red teaming where humans take on the role or goals of malicious actors and simulate adversarial “attacks” or questions to the model to see how the model will respond;

- Multiple choice questions addressing a specific scientific domain with automatic grading;

- Uplift studies where the performance of groups of people on a task using an AI model is compared to the performance of an equivalent group that must achieve the same task but without the AI model; and

- Some combinations and variations on these listed approaches.

Each approach brings with it different strengths and weaknesses; for example, automated multiple-choice-question benchmarks or “tests,” which are historically favored by computer engineers, can be performed rapidly

and lend themselves easily to comparing the “grades” between models and for different versions of the same model (i.e., one could follow how the grades rise or fall between different models and see whether a model is “getting better” at answering biology questions). However, the types of questions posed tend to be simplistic, and the inclusion of reasoning questions has limitations. Closed-ended responses, by definition, also imply that this approach could not be used to “discover” new model capabilities (e.g., trying to find out whether an LLM could design good primers for polymerase chain reaction). Moreover, the meaning attributed to any one grade given to a set of multiple-choice-question assessments is unknown—for example, when could we say that an AI model is good at math? What grade would be needed?

Similarly, there are challenges in probing LLMs to see whether they may provide information that could be used by malicious actors to cause harm. To date, most assessments of LLMs related to biosecurity risks are utilized to see how well LLMs can answer scientific questions rather than providing accurate and actionable information that would significantly help a malicious actor to cause harm. If a model performs poorly on biology questions, for example, the assumption is that the model would be unlikely to provide accurate information to a malicious actor in any significant way. There are limitations in extrapolating these assessments, which is indicative of how nascent the science of model assessments and evaluations currently is. More research is needed to map out the approaches and corresponding methodologies to obtain meaningful results.

In addition, disagreement remains on the nomenclature used to describe the different approaches for LLM assessments. Although red teaming, a term used in military applications and predating AI, is one of the best-known approaches, it is not the only approach. Furthermore, the distinction between general LLMs and domain-specific LLMs, such as biological LLMs, should be considered in model assessments and evaluations.

REFERENCES

Bose, P. 2024. “How cloud labs and remote research shape science.” TheScientist. March 18. https://www.the-scientist.com/how-cloud-labs-and-remote-research-shape-science-71734 (accessed October 18, 2024).

Campbell, M., A. J. Hoane, and F.-h. Hsu. 2002. “Deep blue.” Artificial Intelligence 134 (1–2):57–83. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0004-3702(01)00129-1.

Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency. 2019. Information Sharing Architecture (ISA) Access Control Specification (ACS). U.S. Department of Homeland Security. https://www.cisa.gov/sites/default/files/publications/ISA%2520Access%2520Control%2520Specification.pdf. (accessed October 22, 2024).

Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency. 2024. “CISA announces new efforts to help secure open source ecosystem.” March 7. https://www.cisa.gov/news-events/news/cisa-announces-new-efforts-help-secure-open-source-ecosystem (accessed October 21, 2024).

de Moura, L., and N. Bjørner. 2008. “Z3: An efficient SMT solver.” In Tools and Algorithms for the Construction and Analysis of Systems, edited by C. R. Ramakrishnan and J. Rehof, 337–340. Berlin: Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-540-78800-3_24.

Dohmatob, E., Y. Feng, P. Yang, F. Charton, and J. Kempe. 2024. “A tale of tails: Model collapse as a change of scaling laws.” arXiv. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2402.07043.

Du, X., M. Liu, K. Wang, H. Wang, J. Liu, Y. Chen, J. Feng, C. Sha, X. Peng, and Y. Lou. 2024. “Evaluating large language models in class-level code generation.” IEEE/ACM 46th International Conference on Software Engineering, Lisbon, Portugal, April 14-20, 2024. http://dx.doi.org/10.1145/3597503.3639219.

Dyke, S. O. M., M. Linden, I. Lappalainen, J. R. De Argila, K. Carey, D. Lloyd, J. D. Spalding, M. N. Cabili, G. Kerry, J. Foreman, T. Cutts, M. Shabani, L. L. Rodriguez, M. Haeussler, B. Walsh, X. Jiang, S. Wang, D. Perrett, T. Boughtwood, A. Matern, A. J. Brookes, M. Cupak, M. Fiume, R. Pandya, I. Tulchinsky, S. Scollen, J. Törnroos, S. Das, A. C. Evans, B. A. Malin, S. Beck, S. E. Brenner, T. Nyrönen, N. Blomberg, H. V. Firth, M. Hurles, A. A. Philippakis, G. Rätsch, M. Brudno, K. M. Boycott, H. L. Rehmr M. Baudis, S. T. Sherry, K. Kato, B. M. Knoppers, D. Baker, and P. Flicek. 2018. Registered access: authorizing data access. European Journal of Human Genetics 26 (12):1721–1731. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41431-018-0219-y.

Elmrabit, N., F. Zhou, F. Li, and H. Zhou. 2020. “Evaluation of machine learning algorithms for anomaly detection.” 2020 International Conference on Cyber Security and Protection of Digital Services (Cyber Security), Dublin, Ireland, June 15-19, 2020. https://doi.org/10.1109/CyberSecurity49315.2020.9138871.

Food and Drug Administration. 2021. “FDA approves new use of transplant drug based on real-world evidence.” Last Modified July 16, 2021. https://www.fda.gov/drugs/news-events-human-drugs/fda-approves-new-use-transplant-drug-based-real-world-evidence (accessed January 2, 2025).

Gupta, M., C. Akiri, K. Aryal, E. Parker, and L. Praharaj. 2023. “From ChatGPT to ThreatGPT: Impact of generative AI in cybersecurity and privacy.” IEEE Access 11:80218–80245. https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2023.3300381.

Istrate, A.-M., D. Li, D. Taraborelli, M. Torkar, B. Veytsman, and I. Williams. 2022. “A large dataset of software mentions in the biomedical literature.” arXiv. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2209.00693.

Jagielski, M., A. Oprea, B. Biggio, C. Liu, C. Nita-Rotaru, and B. Li. 2018. “Manipulating machine learning: Poisoning attacks and countermeasures for regression learning.” 2018 IEEE Symposium on Security and Privacy (SP), San Francisco, CA, May 2–24, 2018.

Jiao, Z., J. W. Choi, K. Halsey, T. M. L. Tran, B. Hsieh, D. Wang, F. Eweje, R. Wang, K. Chang, J. Wu, S. A. Collins, T. Y. Yi, A. T. Delworth, T. Liu, T. T. Healey, S. Lu, J. Wang, X. Feng, M. K. Atalay, L. Yang, M. Feldman, P. J. L. Zhang, W.-H. Liao, Y. Fan, and H. X. Bai. 2021. “Prognostication of patients with COVID-19 using artificial intelligence based on chest x-rays and clinical data: A retrospective study.” The Lancet Digital Health 3 (5):e286–e294. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2589-7500(21)00039-X.

Kim, M., and K. Lauter. 2015. “Private genome analysis through homomorphic encryption.” BMC Medical Informatics and Decision Making 15(Suppl 5):S3. https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6947-15-S5-S3.

Longwood Medical Area Research Data Management Working Group. 2024. “Biomedical data lifecycle.” Longwood Research Data Management. October 2. https://datamanagement.hms.harvard.edu/plan-design/biomedical-data-lifecycle (accessed November 6, 2024).

Marcolla, C., V. Sucasas, M. Manzano, R. Bassoli, F. H. P. Fitzek, and N. Aaraj. 2022. “Survey on fully homomorphic encryption, theory, and applications.” Proceedings of the IEEE 110 (10):1572–1609. https://doi.org/10.1109/JPROC.2022.3205665.

Mayo, K. R., M. A. Basford, R. J. Carroll, M. Dillon, H. Fullen, J. Leung, H. Master, S. Rura, L. Sulieman, N. Kennedy, E. Banks, D. Bernick, A. Gauchan, L. Lichtenstein, B. M. Mapes, K. Marginean, S. L. Nyemba, A. Ramirez, C. Rotundo, K. Wolfe, W. Xia, R. E. Azuine, R. M. Cronin, J. C. Denny, A. Kho, C. Lunt, B. Malin, K. Natarajan, C. H. Wilkins, H. Xu, G. Hripcsak, D. M. Roden, A. A. Philippakis, D. Glazer, and P. A. Harris. 2023. “The All of Us data and research center: Creating a secure, scalable, and sustainable ecosystem for biomedical research.” Annual Review of Biomedical Data Science 6:443–464. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-biodatasci-122120-104825.

Mohassel, P., and Y. Zhang. 2017. “SecureML: A system for scalable privacy-preserving machine learning.” 2017 IEEE Symposium on Security and Privacy (SP), San Jose, CA, 22-26 May 2017.

Ng, W. Y., T. E. Tan, P. V. H. Movva, A. H. S. Fang, K. K. Yeo, D. Ho, F. S. S. Foo, Z. Xiao, K. Sun, T. Y. Wong, A. T. Sia, and D. S. W. Ting. 2021. “Blockchain applications in health care for COVID-19 and beyond: A systematic review.” Lancet Digital Health 3 (12):e819–e829. https://doi.org/10.1016/s2589-7500(21)00210-7.

Ponta, S. E., H. Plate, and A. Sabetta. 2018. “Beyond metadata: Code-centric and usage-based analysis of known vulnerabilities in open-source software.” 2018 IEEE International Conference on Software Maintenance and Evolution (ICSME), Madrid, Spain, September 23–29, 2018. https://doi.org/10.1109/ICSME.2018.00054.

Ras, G., N. Xie, M. van Gerven, and D. Doran. 2022. “Explainable deep learning: A field guide for the uninitiated.” Journal of Artificial Intelligence Research 73. https://doi.org/10.1613/jair.1.13200.

Salem, A., R. Wen, M. Backes, S. Ma, and Y. Zhang. 2022. “Dynamic backdoor attacks against machine learning models.” 2022 IEEE 7th European Symposium on Security and Privacy (EuroS&P), Genoa, Italy, June 6–10, 2022.

Sejfia, A., and M. Schäfer. 2022. “Practical automated detection of malicious npm packages.” Proceedings of the 44th International Conference on Software Engineering 1681–1692. https://doi.org/10.1145/3510003.3510104.

Shan, S., W. Ding, J. Passananti, S. Wu, H. Zheng, and B. Y. Zhao. 2024. “Nightshade: Prompt-specific poisoning attacks on text-to-image generative models.” 2024 IEEE Symposium on Security and Privacy (SP), San Francisco, CA, May 19–23, 2024.

Short, A., T. La Pay, and A. Gandhi. 2019. Defending Against Adversarial Examples. Albuquerque, NM: Sandia National Laboratories. https://www.osti.gov/servlets/purl/1569514/.

Shumailov, I., Z. Shumaylov, Y. Zhao, N. Papernot, R. Anderson, and Y. Gal. 2024. “AI models collapse when trained on recursively generated data.” Nature 631 (8022):755–759. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-024-07566-y.

Silver, D., J. Schrittwieser, K. Simonyan, I. Antonoglou, A. Huang, A. Guez, T. Hubert, L. Baker, M. Lai, A. Bolton, Y. Chen, T. Lillicrap, F. Hui, L. Sifre, G. van den Driessche, T. Graepel, and D. Hassabis. 2017. “Mastering the game of Go without human knowledge.” Nature 550 (7676):354–359. https://doi.org/10.038/nature24270.

Singhal, K., S. Azizi, T. Tu, S. S. Mahdavi, J. Wei, H. W. Chung, N. Scales, A. Tanwani, H. Cole-Lewis, S. Pfohl, P. Payne, M. Seneviratne, P. Gamble, C. Kelly, A. Babiker, N. Schärli, A. Chowdhery, P. Mansfield, D. Demner-Fushman, B. Agüera y Arcas, D. Webster, G. S. Corrado, Y. Matias, K. Chou, J. Gottweis, N. Tomasev, Y. Liu, A. Rajkomar, J. Barral, C. Semturs, A. Karthikesalingam, and V. Natarajan. 2023. “Large language models encode clinical knowledge.” Nature 620 (7972):172–180. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-:23062912.

Smith, K. P., and J. E. Kirby. 2020. “Image analysis and artificial intelligence in infectious disease diagnostics.” Clinical Microbiology and Infection 26 (10):1318–1323. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cmi.2020.03.012.

Steinegger, M., and S. L. Salzberg. 2020. “Terminating contamination: Large-scale search identifies more than 2,000,000 contaminated entries in GenBank.” Genome Biology 21 (1):115. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13059-020-02023-1.

Subbiah, V. 2023. “The next generation of evidence-based medicine.” Nature Medicine 29 (1):49–58. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41591-022-02160-z.

Subcommittee on Open Science of the National Science and Technology Council. 2022. Desirable Characteristics of Data Repositories for Federally Funded Research. Office of Science and Technology Policy. https://rosap.ntl.bts.gov/view/dot/62310.

Tama, B. A., B. J. Kweka, Y. Park, and K. H. Rhee. 2017. “A critical review of blockchain and its current applications.” 2017 International Conference on Electrical Engineering and Computer Science (ICECOS), Palembang, Indonesia, August 22–23, 2017. https://doi.org/10.1109/ICECOS.2017.8167115., 2017v.

“The increasing potential and challenges of digital twins.” 2024. Nature Computational Science 4 (3):145–146. https://doi.org/10.1038/s43588-024-00617-4.

Urbina, F., F. Lentzos, C. Invernizzi, and S. Ekins. 2022. “Dual use of artificial intelligence-powered drug discovery.” Nature Machine Intelligence 4 (3):189–191. https://doi.org/10.1038/s42256-022-00465-9.

Wei, A., Y. Deng, C. Yang, and L. Zhang. 2022. “Free lunch for testing: Fuzzing deep-learning libraries from open source.” Proceedings of the 44th International Conference on Software Engineering 995–1007. https://doi.org/10.1145/3510003.3510041.

Wilkinson, M. D., M. Dumontier, I. J. Aalbersberg, G. Appleton, M. Axton, A. Baak, N. Blomberg, J.-W. Boiten, L. B. da Silva Santos, P. E. Bourne, J. Bouwman, A. J. Brookes, T. Clark, M. Crosas, I. Dillo, O. Dumon, S. Edmunds, C. T. Evelo, R. Finkers, A. GonzalezBeltran, A. J. G. Gray, P. Groth, C. Goble, J. S. Grethe, J. Heringa, P. A. C. ’t Hoen, R. Hooft, T. Kuhn, R. Kok, J. Kok, S. J. Lusher, M. E. Martone, A. Mons, A. L. Packer, B. Persson, P. Rocca-Serra, M. Roos, R. van Schaik, S.-A. Sansone, E. Schultes, T. Sengstag, T. Slater, G. Strawn, M. A. Swertz, M. Thompson, J. van der Lei, E. van Mulligen, J. Velterop, A. Waagmeester, P. Wittenburg, K. Wolstencroft, J. Zhao, and B. Mons. 2016. “The FAIR guiding principles for scientific data management and stewardship.” Scientific Data 3 (1):160018. https://doi.org/10.1038/sdata.2016.18.

Xia, W., M. Basford, R. Carroll, E. W. Clayton, P. Harris, M. Kantacioglu, Y. Liu, S. Nyemba, Y. Vorobeychik, Z. Wan, and B. A. Malin. 2023. “Managing re-identification risks while providing access to the All of Us research program.” Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association 30 (5):907–914. https://doi.org/10.1093/jamia/ocad021.

Xu, H., N. Usuyama, J. Bagga, S. Zhang, R. Rao, T. Naumann, C. Wong, Z. Gero, J. González, Y. Gu, Y. Xu, M. Wei, W. Wang, S. Ma, F. Wei, J. Yang, C. Li, J. Gao, J. Rosemon, T. Bower, S. Lee, R. Weerasinghe, B. J. Wright, A. Robicsek, B. Piening, C. Bifulco, S. Wang, and H. Poon. 2024. “A whole-slide foundation model for digital pathology from real-world data.” Nature 630 (8015):181–188. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-024-07441-w.

Xu, Z., Y. Liu, G. Deng, Y. Li, and S. Picek. 2024. “A comprehensive study of jailbreak attack versus defense for large language models.” arXiv. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2402.13457.

Yerlikaya, F. A., and Ş. Bahtiyar. 2022. “Data poisoning attacks against machine learning algorithms.” Expert Systems with Applications 208:118101. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eswa.2022.118101.