Advancing Face and Hand Transplantation: Principles and Framework for Developing Standardized Protocols (2025)

Chapter: 5 The Transplant Experience: Surgical Procedures and Care Management

5

The Transplant Experience: Surgical Procedures and Care Management

After the comprehensive pretransplant process, including when the prospective transplant recipient has been evaluated and decided to proceed with a face or hand transplant and is listed on the waiting list, the next stages include the preparations by the medical and surgical teams for that particular surgery, the procurement and transplantation procedures when a donor becomes available, and the monitoring and care management of the many aspects of adjusting to life as a face or hand transplant recipient. This chapter provides an overview of the surgical procedures for both face and hand transplantation, the immunosuppression regimens that are commonly used, research focused on reducing the risks and burden of lifelong immunosuppression therapy, postoperative rehabilitation, and the psychosocial care of hand and face transplant recipients. The chapter closes with an overview of the most common complications that arise following transplant surgery. Although the care management and monitoring of recovery and rehabilitation following vascularized composite allotransplantation (VCA) are described in this chapter as occurring in discrete steps, these procedures operate on a continuum. It may be suitable to overlay approximate timelines onto care management and monitoring, but every transplant recipient is unique and will progress in an individualized manner.

SURGICAL PROCEDURES

Current VCA surgical techniques and procedures have been built on a foundation of microsurgery and reconstructive surgery performed over decades as well as on the experiences of surgeons performing VCA over

the past 26 years (Barret and Tomasello, 2015; Mendenhall et al., 2020). While the surgical techniques are often routine, the complexities of VCA, especially in face transplantation, necessitate that the details of preoperative preparation are unique and personalized for each patient (Hartzell et al., 2011). Though the surgical steps used in VCA are mature, relatively few face and hand transplants have been performed, so there remains room for innovation and for the development of greater standardization. Therefore, it is critical that surgeons performing VCA continue to share their technical refinements more broadly through peer-reviewed publications, professional society communications, presentations at conferences, and speaking among colleagues.

The following sections provide brief summaries of approaches used in face and hand transplantation, benefits and challenges of these approaches, procedures that are common to VCA procedures, and organizational and logistical considerations that maximize the success of VCA. The sections discuss considerations that are relevant for both face and hand transplantation as well as considerations specific to either face or hand. While there have been instances of face and hand transplants performed simultaneously (Wells et al., 2022), these have occurred rarely and are not discussed in detail here.

Preoperative Planning

Each VCA requires extensive preoperative planning, numerous rehearsals, and the coordination of many people to ensure that procurement of the donor organ and transplantation occur smoothly. The members of the organ procurement organization (OPO) and those of the surgical teams must coordinate their roles, responsibilities, and sequence of events in advance of the procurement. The major events in preoperative planning are listed in Table 5-1.

Surgical rehearsals involving the entire transplant team, using both cadaver tissue and research allograft procurements, are critically important for maximizing the success of the organ procurement and transplant (Gittings et al., 2018; Mendenhall et al., 2020). Customized workflow standardizations are valuable aids in the operating room during both rehearsals and the actual procurement and transplantation (Kantar et al., 2018), such as surgical checklists. Additionally, rehearsals allow for an objective evaluation of outcomes. Some VCA centers assign a rehearsal coordinator to monitor each rehearsal, taking notes that identify steps that go well as well as pitfalls and challenges (Gittings et al., 2018). At the end of a rehearsal, the rehearsal coordinator facilitates the debrief.

Imaging, computerized surgical planning, and three-dimensional (3D) printing may improve intraoperative accuracy and efficiency (Gittings et al., 2018; Mendenhall et al., 2020). Computed tomography (CT) scans of

TABLE 5-1 Preoperative Events to Optimize Procurement and Transplantation for VCA Surgery

| Event | Personnel | Action |

|---|---|---|

| Education | Director of VCA program | Meet with operating room staff to answer questions and explain the many steps of VCA |

| Assembly of teams | Director of VCA program |

|

| Rehearsals | All surgical team members |

|

| Surgical planning/meetings | Lead surgeon, other surgeons, circulating nurse, anesthesiologists, organ procurement organization (OPO) staff, and other team members as needed |

|

| Adjunctive imaging-based planning tools | Surgeons and supporting team members |

|

| Immunosuppression (IS) | Surgeons, anesthesiologists, immunology personnel |

|

| Surgical complications | Entire surgical team |

|

the prospective recipient can be used for computerized surgical planning and to create 3D printed anatomical models and bone-cutting guides. For planning purposes, these aids are prepared in advance and used during rehearsals. Three-dimensional printed models can also serve as educational aids that the surgeon can use in discussions with the patient and the caregivers (Momeni et al., 2016). For face transplants, especially, computerized surgical planning improves the surgical team’s ability to integrate the craniofacial features and their functional relationships with the eyes, oral cavity, and respiratory tract to restore facial expressiveness, animation, speech, aesthetics, and the ability to eat and breathe normally (Ramly et al., 2019).

Planning of the immunosuppressive and immunomodulation therapy regimen preoperatively is imperative. VCA immunosuppression therapy regimens are modeled after those used in solid organ transplants (Kueckelhaus et al., 2016; Mendenhall et al., 2020). Details concerning immunosuppression are found later in this chapter.

Donor Procurement

As with all forms of organ transplantation, face and hand transplants would not be possible without donor procurement through the gift of organ donation. As discussed in Chapter 2, the Uniform Anatomical Gift Act and other state laws regulate the donation and transportation of anatomical gifts. Successful procurement of a face or hand(s) necessitates short ischemia times to optimize viability and functionality of allografts. In 2023, the Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network (OPTN) updated its guidance on optimizing VCA recovery (OPTN, 2023), including recommendations for the timing and sequence of VCA recovery in a donor who is also providing solid organs, including extended time needed in the operating room, coordination of organ recovery, and contingency planning in the event the donor becomes unstable. OPTN guidance says that recovery of VCA allografts is not to compromise the recovery of solid organs. OPTN membership requirements for face and hand transplantation require that the primary surgeon has acted “as the first assistant or primary surgeon on at least 1 covered VCA procurement” (HHS, n.d.). Based on committee surgical experience, participation in just one donor procurement is not enough to guarantee that the clinical team is thoroughly prepared to conduct a VCA. This is particularly applicable to face transplantation as the surgical steps are more highly complex and individualized to patient injuries than hand transplantation, which draws from amputation and replantation techniques.

Procurement of Hand and Upper Extremity Allografts

Typically, the recovery of an upper limb takes less than 1 hour (Mendenhall et al., 2021; OPTN, 2023). Commonly, the donor upper extremity is disarticulated at the joint proximal from the level of amputation in the recipient (Mendenhall et al., 2021).

Procurement of Facial Allografts

Procurement of facial allografts is long and complex, with reports of up to 22 hours (Siemionow et al., 2010). In the earliest face VCA surgeries, the procurement of the facial allograft did not interfere with recovery of solid organs (Siemionow and Gordon, 2010), which meant that solid organ recovery did not begin for more than 10 hours after the donor entered the operating room. Although procuring the face allograft first remains the preferred method for some surgeons (Longo et al., 2024), a number of VCA teams have tested approaches that enable simultaneous recovery of multiple solid organs and a face allograft (Brazio et al., 2013; J. Bueno et al., 2011; Gomez-Cia et al., 2011) or procurement after the other solid organs. Such coordinated efforts reduce recovery and cold ischemia times and prioritize the integrity of the solid organs (e.g., see Figure 3 within Brazio et al., 2013). OPTN guidance recommends that when the VCA recovery is complex, representatives from the VCA transplant program and the OPO weigh the risks and benefits of transporting the donor to the transplant hospital as possible (OPTN, 2023).

Donor Care Units

A donor care unit (DCU), also known as an organ recovery center or specialized donor care facility, is managed by an OPO to monitor organ function and recovery from deceased donors (NASEM, 2022). The use of a DCU may be ideal in the case of face and hand transplant procurement, especially face transplant due to the complexity of procurement. Furthermore, the use of DCUs leads to high satisfaction rates among donor families, decreases the costs of organ procurement, and increases the overall organ procurement yield (NASEM, 2022). DCUs may be available in transplant centers, allowing for optimal care of donors prior to procurement. However, the availability of a DCU is not guaranteed, due to the location of OPOs and financial challenges within hospitals (NASEM, 2022).

Transplant Surgical Procedures

There is little consensus on coordinating the timing between donor procurement of a face allograft and beginning surgery on the recipient. Some propose that surgery on the recipient should only begin once the donor procedures are complete (Longo et al., 2024). Others propose that beginning the recipient surgery for facial VCA several hours before the donor surgery (but not advancing the recipient surgery beyond a “point of no return”) may reduce wait times for the donor surgery and reduce the risk of prolonged ischemia (Brazio et al., 2013). Considerations regarding the timing of donor and recipient procedures include ischemia time, prioritization of solid organ procurement, and donor instability, and are frequently case dependent (Brazio et al., 2013; La Padula et al., 2022).

When organ recovery and transplant occur in the same hospital, donor and recipient preparations can begin simultaneously (OPTN, n.d.-a). When the allograft must be transported to the transplant hospital following procurement, surgical teams and OPOs maintain regular communication to signal that is okay to begin the recipient surgery (OPTN, n.d.-b). Factors that affect this are the distance between the hospitals, the mode of transporting the allograft, the minimization of ischemia time, the type of upper extremity allograft, and the health of both the recipient and donor allografts (Hartzell et al., 2011; Hausien et al., 2014).

Insights into warm and cold ischemia are largely derived from the experience in replantation, revascularization, and solid organ transplantation. Prolonged ischemia is associated with allograft rejection. Currently, the responses of the diverse tissues as well as the perfusates are under study. Reported analyses have exposed a lack of data on extremity functional recovery following cold ischemia, particularly in humans or large animal models (Chakradhar et al., 2024).

Facial Allotransplantation

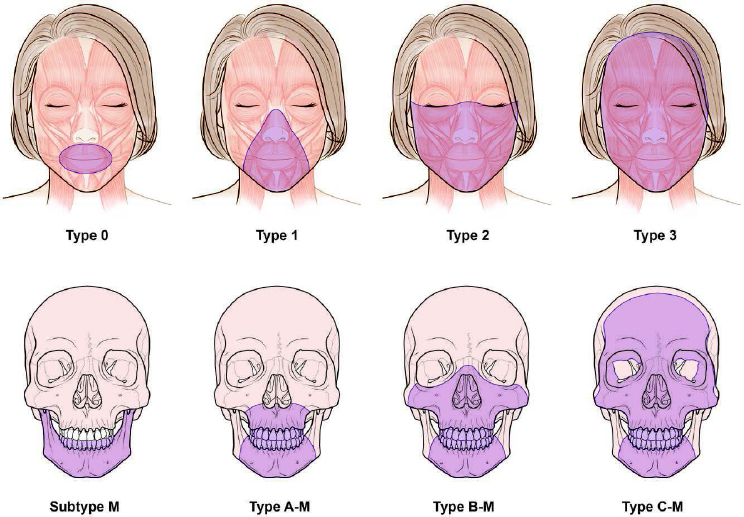

From a surgical perspective, face transplantation has evolved from a combination of craniofacial, microsurgical, and aesthetic principles (Rifkin et al., 2018a). There are multiple degrees of facial injuries among patients who may be suitable candidate for face transplant. However, developing patient-specific reconstructive strategies is a challenge, as facial defects can vary widely in potential candidates. A procedure may require a partial face transplant or mid-face transplant and may include scalp, soft tissue only, or bone and soft tissue. This variability and the limited number of procedures performed have made it particularly difficult to standardize the steps of face transplant, as every patient and every defect is unique (Kantar et al., 2018; Vincent et al., 2021). However, there is a soft-tissue and skeletal

tissue defect classification system for facial transplantation to help with the standardization of future procedures and to aid in communication (Kantar et al., 2021; see Figure 5-1).

Although the specific surgical steps will vary based on the level of transplant in each patient, following extensive surgical preparation, mapping, and modeling for the specific recipient and donor procurement, there are steps that are common to most facial VCA surgery. The commons steps include:

- Excision of previously injured and scarred autologous facial tissue to create mirroring defects for precise adaptation of the donor facial allograft.

- Dissection of essential structures including facial and mental nerves.

- Use of cutting guides for skeletal subunit osteotomies that match donor facial allograft.

- Allograft is brought into appropriate position, and if bone is included, bony subunits are rigidly fixed using titanium plates and screws.

- Blood vessels (e.g., jugular and facial veins, carotid arteries) are anastomosed, using an operating microscope, to restore profusion and drainage of the allograft, and facial nerve branches are coaptated.

- Other soft tissues (e.g., tendons, ligaments, muscles, ears, eyelid, nasal and oral mucosa) are tailored specifically to the recipient, using microsurgical reconstruction, and finally skin closure (Ceradini et al., 2024; Pomahac et al., 2012; Ramly et al., 2022; Sosin et al., 2016).

Computerized surgical planning is a tool that has recently been often incorporated into facial transplant surgeries (Kantar et al., 2021). Combined with CT-directed intraoperative navigation, computerized surgical planning enables precision alignment of the donor allograft to the recipient skull base (Dorafshar et al., 2013). Cutting guides and stereolithographic models are also indispensable aids during transplantation of the allograft. Face transplants are performed under general anesthesia, and details of the face injury and past reconstructive efforts, such as the presence of a tracheostomy tube, influence airway management plans (Cywinski et al., 2011).

Hand and Upper Extremity Allotransplantation

The sequence of limb transplantation is similar to those used in upper extremity replantation (Haddock et al., 2013; Hartzell et al., 2011). Although the specific surgical steps vary based on the level of transplant

NOTES: Soft-tissue defects (above) are classified as type 0, oral (includes the upper lip, lower lip, and oral commissures); type 1, oral–nasal (includes the nasal soft-tissue structures with or without type 0); type 2, oral–nasal–orbital (includes infra-orbital and malar regions with or without type 1); type 3, full facial (includes the forehead, supraorbital, and preauricular regions and can include all facial soft tissues). Skeletal tissue defects (below) are classified as type A, Le Fort I–type (involves the maxilla partially or completely); type B, Le Fort III–type (includes the maxilla, inferomedial orbital, and zygomatic bones with or without nasal, vomer, and ethmoid bones); type C, monobloc advancement type (includes frontal and supraorbital bones with or without facial bones in the other types of defects); and subtype M, mandibular involvement (includes the mandible partially or completely). Patients with type 0 defects may be candidates for conventional reconstruction methods, but if the results are inadequate, then face transplantation may be considered.

SOURCE: Kantar et al., 2021; printed with permission and copyrights retained by Eduardo D. Rodriguez, M.D., D.D.S.

and condition of the residual limb of each patient, there are steps that are common to upper extremity VCA surgery. The sequence of repair follows the individual cases but generally, and after the skin flaps are designed, bone fixation follows. The transplant is completed when all the tissues are repaired as applicable. Common steps in most hand and upper extremity allotransplantation cases include:

- Skin flaps are designed to allow for interdigitation upon closure.

- Muscular origins off the medial and lateral epicondyles of the humerus are dissected free and excised, and all key neurovascular structures are identified and tagged.

- Distal and proximal portions of the radius and ulna are exposed circumferentially with preservation of the interosseous membrane.

- After confirming adequate osteotomies without bony block to pronation or supination, the donor and recipient extremities are brought together.

- Osteosynthesis is performed.

- Vascular anastomosis, tendon/muscle repair, and nerve repair are performed, and finally skin closure (Haddock et al., 2013; Mendenhall et al., 2020).

The preoperative use of radiology scans and computerized surgical planning and 3D printing of personalized cutting guides greatly improves the efficiency and precision of the transplant procedure (Kantar et al., 2018). Osteosynthesis can be facilitated using implants, which improve precision, increase bone-to-bone contact, and reduce the time needed for osteosynthesis (Higgins et al., 2014; Mendenhall et al., 2015; Momeni et al., 2016). Hand transplantation has been performed under general anesthesia with supplemental brachial plexus block, as well as with regional block and ultrasound-guided infraclavicular catheters to provide a sympathetic block to facilitate blood flow to the upper extremities and to provide both intraoperative and postoperative pain control (Gordon and Siemionow, 2009; Gurnaney et al., 2016; Lang et al., 2012; Pulos et al., 2015).

Despite the common steps described above, there are differences among surgical techniques used by different VCA teams, such as performing a vascular shunt first to reduce ischemia or carrying out a different sequence of structure repairs.

Secondary Surgeries

Following the initial face transplant surgery, revisions are often performed to improve functional and aesthetic outcomes and to address postoperative complications and conditions such as hematomas, malocclusion, ptosis, palatal fistulae, ectropion, facial muscle and/or lid retraction, and contour abnormalities (Aycart et al., 2016; Bassiri Gharb et al., 2017; Kantar et al., 2021; Khalifian et al., 2014; Mohan et al., 2014; Rifkin et al., 2018a; Sosin et al., 2016). Secondary surgeries are also performed to remove or tailor excess skin and soft tissue that was used in the initial transplant to allow for swelling and edema without compromising blood flow (Diep et al., 2020). Revisions or additional surgeries following

hand transplantation also take place following complications or functional decline (Wells et al., 2022).

POSTTRANSPLANT CARE MANAGEMENT AND MONITORING

“I opened my eyes and noticed my new hands swaddled and splinted. I thought, like a father seeing his newborn: those are the most beautiful hands I have ever seen. Immediately they felt like mine: my mental map and the territory of my body realigned in an instant. This moment was wholly opposite the trauma, 3 years earlier, of emerging from surgery without arms: now, I felt healed.”

— Bilateral hand transplant recipient, written testimony to the committee

“When I woke up from surgery, I couldn’t feel anything, but I could see these two new hands attached to my body. They became my hands immediately. It was one of the happiest days of my existence.”

— Bilateral hand transplant recipient, presented testimony to the committee at the March 22, 2024, public webinar

“As soon as I woke up, I was able to talk through my [tracheostomy tube] … 2 or 3 days after surgery I was able to eat.”

— Face and bilateral hand transplant recipient, presented testimony to the committee at the June 6, 2024, public webinar

Face and hand transplant recipients are not unlike patients who have chronic, treatable but not curable disease. These patients and their caregivers play a critical role in the management of their own disease. Patients therefore need to have or to acquire the information and skills to successfully engage in self-care—managing their disease on a daily basis (e.g., medication adherence, rehabilitation adherence) and self-monitoring (e.g., detecting early signs of rejection). Successful self-management is best accomplished when patients understand the commitment to treatment from the beginning (see Chapter 4 for more information).

Organ transplantation is increasingly viewed as therapy for a chronic condition that requires intensive monitoring and surveillance during the patient’s lifetime, as opposed to a “cure” (Deng et al., 2023; Lai et al., 2020; Lieber et al., 2021). Survivorship is a well-established concept in the cancer care continuum (IOM, 2006; Mayer et al., 2017; Moser and Meunier, 2014) and has begun to be used in the discipline of organ transplantation, with

a reframing of transplantation as a “life-altering experience that poses different physical, emotional, and psychological challenges for recipients and caregivers,” rather than merely a treatment (Lieber et al., 2021, p. 2). This concept is particularly relevant to face and hand transplantation, given the commitment to lifelong medical care necessary following transplant and with recovery as an ongoing and ever-changing process.

Care management and monitoring for VCA recipients involves the management of immunosuppression, monitoring for signs of rejection and other complications, rehabilitation protocols, and psychosocial support for patients and caregivers. Following the transplant surgery, face and hand VCA recipients initially spend time in the hospital where they are monitored for signs of rejection and surgical, immunological, and vascular complications (Vincent et al., 2021). There is monitoring for vascular inflow and outflow to assure adequate perfusion of the allograft during this time (Kaufman et al., 2012; Kumamaru et al., 2014). Blood draws are used to monitor immunosuppressive drugs. If there are visible signs on the skin of possible rejection, tissue biopsies are performed to confirm and diagnose rejection histologically. Imaging and other tests are also used at different centers to monitor the transplant. Once a patient is discharged from the hospital, at-home monitoring and care management is crucial. Patients typically continue rehabilitation at a medical facility and at home (La Padula et al., 2022) and should continue to monitor for signs of rejection. Patient and caregivers are provided education to continue monitoring after discharge (Within Reach, n.d.-a). In addition to monitoring for and managing any medical problems should they arise, therapeutic levels of immunosuppression are monitored as well as rehabilitation and psychosocial support.

IMMUNOSUPPRESSION TO MINIMIZE TRANSPLANT REJECTION

All VCAs are subject to immune rejection for as long as the recipient has the transplant. As with other organ transplants, VCA recipients receive a combination of immunosuppressant drugs from the time of the transplant. Immunosuppressive therapy in VCA is modeled after regimens used in solid organ transplantations; there is an induction phase, a maintenance phase, and rescue therapy as applicable (Elliott et al., 2014; Kirk, 2006; Mendenhall et al., 2020; Tintle et al., 2014; Wells et al., 2022). Induction uses relatively high dosages of drugs designed to prevent acute rejection to the VCA in the days following transplantation. Induction immunosuppression gives way to maintenance therapy as the host’s immune response gradually lessens. Maintenance therapy is less potent than induction, but is tolerable for chronic use (Kirk, 2006). Rescue therapy is initiated in response to a

rejection episode, and like induction, it is more intense and effective than maintenance regimes, though it is too toxic for long-term use.

The management of a transplant patient’s immunosuppression and monitoring for signs of rejection as well as for other complications arising from immunosuppression are similar for patients who received a VCA and those who received a solid organ transplant. What is unique for skin containing VCA is that rejection is monitored by looking for visual changes in the allografted skin (Cendales et al., 2008) and diagnosed by histological examination (Schneider et al., 2016). Rejection based on histology is scored using a standardized classification system (Cendales and Kleiner, 2003; Cendales et al., 2008, 2024). Monitoring for rejection continues for as long as the recipient has the allograft. Therapies designed to prevent rejection follow those of other solid organ transplants for both T-cell and for antibody-mediated rejection. Current immunosuppressive therapies have significantly reduced acute rejection of solid organ transplants to approximately 5 percent in kidney (Lentine et al., 2024), 18–29 percent in heart (Colvin et al., 2024), 10–25 percent in lung (Valapour et al., 2024), and 22–50 percent in intestine (Horslen et al., 2024), with differences by age group and by regimen in some organs. To date, from 85 percent to 90 percent of VCA recipients have experienced rejection within the first year after transplantation, a rate greatly exceeding all other transplanted organs (Giannis et al., 2020; Petruzzo and Dubernard, 2011). In addition, essentially all VCA recipients have experienced immunosuppressive side effects, most of which are related to the use of calcineurin inhibitors (CNIs) and steroids (Petruzzo et al., 2010; Uluer et al., 2016), with some patients requiring kidney transplantation after hand and face transplantation due to nephrotoxicity (Barth et al., 2019).

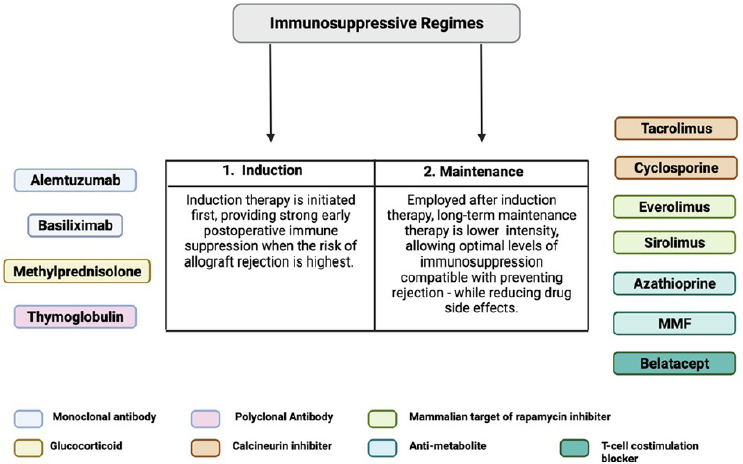

Currently, the most common regimen in VCA is a triple-drug regimen with tacrolimus, mycophenolate mofetil, and steroids following induction therapy, with antithymocyte globulin (ATG) as the most commonly used T cell–depleting induction agent. Figure 5-2 lists immunosuppression currently used for face and hand transplantation.

Induction of Immunosuppression

Briefly, induction immunosuppression is a short-duration, relatively high-dosage therapy given at the time of transplantation. The need for induction is based on evidence that more intense immunosuppression is necessary early to counteract the host’s rapid and powerful alloimmune response to the allograft and transplantation-induced injury (Kirk, 2006). The regimen used for induction is typically a combination of two to four drugs, most often from among ATG, prednisone, tacrolimus, mycophenolate

NOTE: MMF = mycophenolate mofetil; VCA = vascularized composite allotransplantation.

SOURCE: Huelsboemer et al., 2024; CC BY 4.0.

(MMF), alemtuzumab, rapamycin, basiliximab, and belatacept (Elliott et al., 2014; Huelsboemer et al., 2024; Wells et al., 2022).1

___________________

1 Antibodies like alemtuzumab and thymoglobulin reduce T cell populations and down-regulate T cell activity by binding directly to T cell surface receptors, triggering apoptosis, opsonization, and complement-dependent lysis (Ballen, 2009). Alemtuzumab targets mature cells expressing CD52, including T and B lymphocytes, monocytes, and eosinophils, while thymoglobulin also inhibits the function of B cells, dendritic cells, natural killer cells, and regulatory T cells (Brayman, 2007; Jones and Coles, 2014; Mueller, 2007; Weaver and Kirk, 2007). It has been reported that within minutes of delivering a dose of alemtuzumab to a person, their peripheral lymphocytes are undetectable (Jones and Coles, 2014). However, T cells are depleted in a variable manner by alemtuzumab. Antigen-experienced memory T cells are less susceptible to depletion than are naive T cells or T cells with a CD4+CD25+ regulatory phenotype (Pearl et al., 2005; Weaver and Kirk, 2007). Thus, the effectiveness of alemtuzumab may depend on the T cell repertoire of the patient at the time of transplant (Weaver and Kirk, 2007). The antibody basiliximab recognizes a portion of the IL-2 receptor complex on T cells. Basiliximab binding to the receptor competitively inhibits IL-2 binding, which blocks IL-2 stimulation of its downstream signaling pathways, and consequently prevents the host from mounting a T cell–based immune response (Du et al., 2010; McKeage and McCormack, 2010). Methylprednisolone, like some other corticosteroids, prevents the release of cytokines from both T cells and antigen presenting cells, but like other drugs in this class, methylprednisolone causes a wide range of adverse systemic effects, including impaired wound healing, diabetes mellitus, and osteopenia (Giannis et al., 2020; Moudgil and Puliyanda, 2007). Rituximab has also used for induction immunosuppression to deplete mature B cells, in particular donor-derived B cells that reside in donor skin and are therefore transplanted (Gelb et al., 2018).

Maintenance of Immunosuppression

Face and hand transplant recipients are on immunosuppression medications for life. This is, perhaps, the most challenging risk factor associated with these transplants. The current goal among VCA researchers and clinicians is to develop immunosuppressive approaches that are less morbid and damaging by lessening adverse side effects. A generalizable approach to immune management of VCA recipients has not been established. The most frequently used regimen is a triple-drug therapy composed of tacrolimus, MMF, and a steroid (Huelsboemer et al., 2024; Kaufman et al., 2019; Mendenhall et al., 2020; Wells et al., 2022). Due to tacrolimus’s detrimental effects on the kidneys and the systemic side effects of long-term steroid use, alternative immunosuppressive strategies are now being optimized, using costimulation blockade-based regimens with belatacept (Cendales et al., 2015, 2018).

Succinctly, inhibitors of the Ca2+-sensitive phosphatase, calcineurin, block dephosphorylation of the transcription factor, nuclear factor of activated T cells (NFAT), which prevents NFAT transport into the nucleus and subsequent expression of numerous cytokines, chemokines, and other genes necessary for T cell proliferation, differentiation, and effector function acquisition (Lees et al., 2014; Park et al., 2020; Ravindra et al., 2012).2 Analogues of purine inhibit purine synthesis pathways (Allison and Eugui, 2000; Broen and van Laar, 2020). Purine analogues used following transplant have included azathioprine, and MMF, which inhibits inosine mono-phosphate dehydrogenase, and thus blocks de novo synthesis of guanosine nucleotides, halting cell proliferation by preventing nucleic acid synthesis. Inhibitors of mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) kinase block intracellular signaling pathways that are triggered by cytokines (including IL-2) and growth factors (Kovarik, 2013). One significant consequence of mTOR inhibition is a reduction in protein synthesis, which arrests T and B cells in the G1 phase of the cell cycle, thus blocking lymphocyte proliferation and reducing antibody production (Yang et al., 2022). Due to the nephrotoxicity of calcineurin inhibitors, mTOR inhibitors have been tested both instead of calcineurin inhibitors in immunosuppression trials and in conversion from a calcineurin inhibitor to an mTOR inhibitor (Schmitz et al., 2020; Swanson et al., 2002). Corticosteroids suppress the immune system in several relatively nonspecific ways, such as by blocking many proinflammatory cytokines and prostaglandins (Löwenberg et al., 2008; Ravindra et al.,

___________________

2 Unfortunately, calcineurin is evolutionarily highly conserved and is critical in Ca2+-sensitive pathways in the brain, heart, and skeletal muscle (Schulz and Yutzey, 2004), thus prolonged use of calcineurin inhibitors can have serious systemic side effects, in particular, nephrotoxicity and glucose intolerance. Calcineurin inhibitors include tacrolimus, cyclosporine, pimecrolimus, and voclosporin, among which tacrolimus and cyclosporine are used for transplants.

2012), which thus inhibits a range of cellular- and antibody-based immune responses. While glucocorticoids are effective at preventing acute rejection, there are ongoing trials to find alternative drugs.

Costimulation Blockade

Costimulation blockade has been developed to achieve antigen control over transplant rejection while minimizing the broad attenuation of protective immunity seen with conventional immunosuppressives. A randomized controlled study of kidney transplant patients found increased patient and allograft survival and improved renal function with belatacept at 7 years post transplantation compared with a cyclosporine-based regimen (Vincenti et al., 2016).3 Belatacept was approved as a CNI replacement therapy in kidney transplant recipients with significantly better renal function and better patient and allograft survival compared with cyclosporine (Vincenti et al., 2016). Belatacept is more effective at preventing the development of donor-specific antibodies (DSAs) but may be inferior to CNIs in the short term in the prevention of acute cellular rejection (Vincenti et al., 2016). Its safety profile is comparable to, if not better than, CNI medications (Muduma et al., 2016). Specifically, belatacept offers better blood pressure management, improved lipid metabolic profile, and a lower incidence of posttransplantation diabetes (Bamgbola, 2016; Masson et al., 2014).

Costimulation immunosuppression has been extensively studied preclinically in both small- and large-animal models (Atia et al., 2020; Kirk et al., 1997, 1999, 2001, 2014; Larsen et al., 2005; Preston et al., 2005; Xu et al., 2003). Clinically, belatacept has been used successfully as a CNI replacement in a hand transplant recipient at 42 months post transplantation (Cendales et al., 2015). The use of de novo belatacept has also been used in hand transplantation (Cendales et al., 2015, 2018). In one clinical study, a hand transplant recipient was treated with belatacept, MMF, steroids, and tacrolimus, followed by conversion to sirolimus at 6 months. This study demonstrated that belatacept can be incorporated as a core component of antirejection regimens, minimizing the use of CNI and its long-term adverse effects, a particularly important goal in VCA.

___________________

3 The risk of death or long-term allograft loss was reduced by 43 percent with both belatacept regimens tested, and the glomerular filtration rate (GFR) increased, compared with cyclosporine-nephrotoxicity GFR decrease (Vincenti et al., 2016). However, the BENEFIT study demonstrated high cumulative rates of acute rejection in both high- (24.4 percent) and low- (18.3 percent) intensity belatacept groups compared with cyclosporine (11.4 percent) at 7 years post transplantation.

Future Directions in VCA Immunomodulation

A generalizable immunosuppression regimen has not been established in VCA. Continued preclinical and clinical VCA research is necessary to establish principles underlying a VCA-specific immunosuppression regimen. Attention should be given to less morbid immunosuppressive approaches when supported by emerging data. Reduction of the high incidence of allograft rejection, particularly in the first posttransplant year, should be a priority.

Approaches include maintaining a therapeutic level of immunosuppression, close monitoring of the allograft to include protocol biopsies and treatment of subclinical rejection. Research approaches should also focus on differential diagnosis manifested with skin changes. Focus should be put on developing immunosuppression regimens that target specific alloimmune mechanisms (e.g., costimulation blockade), avoid associated end-organ toxicities of immunosuppressants, decrease the adverse effects of broad metabolic pathways (e.g., CNIs), and prevent the development of donor specific antibodies.

Research on Immunomodulation

Preclinical studies in VCA in rodents have shown that a complete limb allograft in a rat model elicited a weaker immune response than did allografts of individual tissue components (Lee et al., 1991). In addition, the tissue components of the intact grafted limb interacted with the host immune system “in a complex but predictable pattern with differing timing and intensity” (Brandacher et al., 2012, p. 676). Other studies of transplanting a hindlimb in mice have used the unique opportunities that VCA offer to assess the relative contribution of peripheral and secondary lymphoid tissue to the process of rejection (Moris and Cendales, 2021). The studies showed that in the absence of lymphoid nodes, allografts are rejected in a delayed fashion. Additionally, splenectomy in alymphoplastic mice further extended allograft survival but did not eliminate rejection all together.

Preclinical studies in nonhuman primates have shown that costimulation blockade-based regimens prevent rejection and prolong survival in VCA (Freitas et al., 2015). Specifically, a belatacept-based regimen was used, given the evidence indicating that it can improve both the specificity and tolerability of anti-rejection therapy and that it is effective in preventing DSA formation, a well-recognized cause of allograft loss.

In humans, a study found that levels of C-reactive protein (CRP), a potent activator of the innate immune system, correlated with acute allograft rejection in face transplant patients (Kiefer et al., 2024). In a rat hindlimb model, CRP induced activation of a specific subpopulation of

monocytes, which aggravated early rejection of the allograft and reduced allograft survival (Kiefer et al., 2024). The administration of 1,6-bis-phos-phocholine inhibited CRP activation of monocytes and thus mitigated allograft rejection. Other approaches have included the use of donor bone marrow and stem cells to induce immunotolerance by generating a mixed chimeric state in the recipient (Sachs et al., 2014).

Monitoring and Research on Surrogate End-Point Markers of Allograft Rejection

An overarching challenge regarding immunosuppression across all forms of organ transplantation is the absence of personalized medicine, leading to difficulties with monitoring the immune status and response of transplant patients, due to a lack of tests to determine the optimal amounts of immunosuppressive drugs (Jaksch et al., 2022). The current methods of monitoring for immune responses, both histologically and clinically, are used across both solid organ transplantation and VCA (Leonard et al., 2020; Valenzuela and Reed, 2017), and more research will be necessary before it may be possible to determine whether a patient is being treated with the appropriate amount of immunosuppression. A major difference between solid organ and VCA rejection monitoring is the use of the skin as an indicator of rejection (Leonard et al., 2020); however, it is expected that the specific immune responses in VCA patients will likely continue to be monitored similarly to solid organ transplant until there is a breakthrough in VCA-specific immunologic research.

Face and hand VCA allografts are routinely monitored for signs of allograft rejection by visual inspection of the skin and by histological evaluation of skin biopsies. The histopathology is reported in accordance with the universally accepted Banff 2007 and Banff 2022 grading systems for skin-containing composite tissue allografts (Cendales et al., 2008, 2024). There are, however, several limitations with this method: observed inflammation is not specific to allograft rejection, rejection may be subclinical and thus may not manifest as changes to the skin, and the degree of visible skin changes does not consistently correlate with the severity of rejection based on histopathology of skin biopsies (Honeyman et al., 2021). As with other organ transplants, it will be valuable to identify additional reliable surrogate end-point markers of rejection. To date, the search for potential VCA biomarkers has focused on cells and molecules in tissue and blood that associate (and ideally, correlate) with allograft rejection (Honeyman et al., 2021; Kollar et al., 2018, 2019).

MONITORING AND CARE MANAGEMENT OF COMPLICATIONS

As is the case with all other transplants, medical and surgical complications in VCA continue to represent important causes of mortality and morbidity—predominantly, allograft rejection, infections (Splendiani et al., 2005), malignancies (Buell et al., 2005; Hartevelt et al., 1990), renal problems (McKane et al., 2001; Ojo et al., 2003), systemic metabolic disorders (Elliott et al., 2014; Kaufman et al., 2019; Mendenhall et al., 2020; Wells et al., 2022), and allograft dysfunction (Kamińska et al., 2014; Milek et al., 2023; Uluer et al., 2016) (see Table 5-2). For a discussion of mental health complications, see section on psychosocial care management.

Intraoperative and Perioperative Complications

Reported surgical risks to the patient during face or hand transplantation include infection, thrombosis, myocardial infarction, stroke, and death (Aycart et al., 2016; Longo et al., 2023). Significant hemorrhaging has taken place during VCA surgery, requiring multiple blood transfusions (Edrich et al., 2012). Additionally, patients may also experience bone healing problems (e.g., non-union and delayed union), blood disorders (e.g., thrombosis), and cardiovascular disorders (e.g., cardiovascular instability).

Allograft Rejection, Allograft Dysfunction, and Allograft Loss

Allograft failure is defined by the OPTN as when a recipient is re-registered for the same VCA, the recipient dies from conditions including, but not limited to, allograft failures, cardiac arrest, malignancy, or infection, or there is an unplanned removal of a VCA (OPTN, 2022). VCA allograft rejection is categorized as either hyperacute, acute, or chronic rejection; the differentiation is based largely on elapsed time post transplant, clinical and histopathological presentation, and immunological mechanisms. The differences among these categories are discussed in this section. Unlike solid organ transplants, allograft outcomes in VCA are imprecisely defined. Metrics of function are multifactorial and are dependent on the recipient’s initial injuries, amount of tissue loss, outcome expectations, and degree of adherence with the regimens of immunosuppression and rehabilitation (Uluer et al., 2016). Allograft dysfunction has primarily resulted from rejection, infection, and subsequent surgical procedures (Sosin et al., 2015). For face VCA recipients, allograft loss may result in death. To date, the exit strategy in case of facial allograft failure differs across teams and patients (Diaz-Siso et al., 2018; Ozkan et al., 2017). Based on a 2023 systematic literature review, seven facial allografts were lost (14.6 percent of face VCAs), of which two underwent retransplantation and four were reconstructed using tissue flaps. Of these seven, four survived (Longo et al., 2023).

TABLE 5-2 Possible Medical Complications Following Face and Hand Transplantation

| Intraoperative and perioperative complications | Poor bone healing; blood disorders (e.g., thrombosis); cardiovascular disorders; stroke; tendon adherence; incomplete reinnervation; infection; death |

| Allograft failure and loss | Allograft failure |

| Allograft loss | |

| Allograft rejection | Hyperacute rejection |

| Acute rejection | |

| Chronic rejection | |

| Antibody-mediated rejection | |

| Infection | Nosocomial infections |

| Pseudomonal allograft infections | |

| Sepsis | |

| Hardware infections | |

| Osteomyelitis | |

| Pneumonia (aspiration, ventilator-associated) | |

| Pulmonary aspergilloma | |

| Candida surgical site infections | |

| Tinea/noninvasive cutaneous fungal infections | |

| Viral infections (CMV, HSV, VZV, HPV) | |

| Malignancy | Lymphoma |

| Reoccurrence | |

| Cutaneous malignancies | |

| Hepatocellular carcinoma | |

| Lung cancer | |

| Renal dysfunction and metabolic disease | Acute and chronic renal failure |

| Diabetes | |

| Metabolic syndrome | |

| Osteoporosis | |

| Syndrome of inappropriate antidiuretic hormone secretion |

NOTES: CMV = cytomegalovirus; HPV = human papillomavirus; HSV = herpes simplex virus; VZV = varicella zoster virus.

SOURCES: Data from Aycart et al., 2016; Longo et al., 2023; Uluer et al., 2016; and committee expertise.

For VCA recipients, histopathology using the Banff VCA classification system is the gold standard for the diagnosis of rejection and for guiding treatment for skin containing VCAs. Similar to the Banff classifications system for kidney transplants (Roufosse et al., 2018), the Banff system for VCAs is a living document and represents the deliberations and consensus of numerous pathologists, physicians, surgeons, immunologists, and dermatologists from around the world (see Table 5-3) (Cendales et al., 2008, 2024). Currently, the Banff system is based on skin and does not include antibody-mediated rejection or chronic rejection. Similarly, the system does not include assessment of rejection in other tissues in a VCA such as mucosa, muscle, or nerve.

Rejection

Transplant immunology is a complex series of events that include immune and non-alloimmune processes. In general, the forms of allograft rejection are hyperacute, acute, chronic, and antibody-mediated rejection. These forms represent pathologic consequences of one or more processes. Acute rejection is characterized by T cell infiltration within the allograft. Later in the process, there is tissue destruction. Chronic rejection includes the development of progressive vascular neointimal proliferation and represents a remodeling response.

Hyperacute rejection

Hyperacute rejection generally occurs within 24 hours (from minutes to hours) of transplantation. It is dependent on the presence of preformed circulating antibodies with specificities for polymorphisms on the allograft endothelia. The presence of DSAs at the time of transplantation or the subsequent formation of de novo DSAs against human leukocyte antigens and ABO antigens on donor epithelial cells can trigger complement activation and coagulation cascades that lead to vascular thrombosis, infarcts, and subsequent rejection and loss of the allograft. These donor-specific antibodies underlie hyperacute rejection but are also currently considered as the primary cause of late allograft rejection and failure (Moris and Cendales, 2021).

Acute rejection

Approximately 85 percent of face and hand transplant recipients have experienced one or more acute rejection episodes within the first year (Uluer et al., 2016), making its occurrence higher than any for other transplant and the most common postsurgical complication for VCA recipients (Fischer et al., 2014; Issa, 2016; Kueckelhaus et al., 2016; Petruzzo and Dubernard, 2011). Untreated rejection leads to chronic rejection (Within Reach, n.d.-b). Acute rejection usually occurs soon after the transplant but can also take place years later (Kanitakis et al., 2016). Rejection typically “manifests clinically with erythematous, macular or

TABLE 5-3 Definitions and Scoring Systems of Potential Allograft Changes in VCA

| Term | Vasculitis | Vasculopathy | Capillary Thrombosis | Pathology |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Definition | Mononuclear cells underneath vessel endothelium, scored on the most involved vessel, including capillaries, arterioles, venules, veins, arteries. The number and type of involved vessels must be reported. | Intimal thickening with fibrosis, and/or mononuclear cell infiltrate in fibrosis and/ or formation of neointima. Reported as percent of luminal reduction. | Thrombosis in capillaries | |

| Scoring system | v0: No vasculitis v1: Mild to moderate intimal vasculitis in at least one vessel cross section. v2: Severe intimal vasculitis with at least 25% luminal area lost in at least one vessel cross section. v3: Transmural vasculitis and/or vascular fibrinoid change and medial smooth muscle necrosis with mononuclear infiltrate in vessel. vx: No vessels |

av0: None av1: 25–50% luminal reduction av2: >50% luminal reduction avx: No arteries |

T0: Absent T1: Present |

Grade 0: No or rare inflammatory infiltrates. Grade I: Mild. Mild perivascular infiltration. No involvement of the overlying epidermis. Grade II: Moderate. Moderate-to-severe perivascular inflammation with or without mild epidermal and/or adnexal involvement (limited to spongiosis and exocytosis). No epidermal dyskeratosis or apoptosis. Grade III: Severe. Dense inflammation and epidermal involvement with epithelial apoptosis, dyskeratosis, and/or keratinolysis. Grade IV: Necrotizing acute rejection. Frank necrosis of epidermis or other skin structures. |

SOURCE: Cendales et al., 2024.

diffuse, lesions over the allograft skin, and, histologically, with dermal and epidermal changes, including mainly dermal perivascular infiltration with T cells, epidermal keratinocyte vacuolization or apoptosis, lichenoid changes, necrosis of the epidermis and its adnexa” (Kanitakis et al., 2016, p. 2054), or changes to the nail bed (Fischer et al., 2014; Kanitakis, 2006, 2007; Sarhane et al., 2014). Less commonly, acute rejection symptoms have been reported to include pain and edema in some recipients (Within Reach, n.d.-a). Steroids have been used to treat acute rejection of hand allografts in more than 90 percent of cases reported to the IRHCTT, or antibodies (antithymocyte globulins, basiliximab, or alemtuzumab) were used for steroid-resistant rejection (Petruzzo et al., 2010, 2017). In addition to the oral or intravenous treatments, topical corticosteroid and tacrolimus were used either individually or in combination in 86 percent of the reported cases (Petruzzo et al., 2017). For face VCA, 100 percent of the acute rejection episodes reported were treated with intravenous steroids, with a minority of cases also receiving an increased dose of oral steroids, supplementation with topical immunosuppressants, or both (Petruzzo et al., 2017).

Chronic rejection

Chronic, or long-term, rejection occurs months to years after a face or hand transplantation (UNOS, n.d.; Within Reach, n.d.-a). Though chronic rejection has not been formally defined in VCA and the underlying mechanism(s) leading to chronic rejection remains unknown, there is documented histologic evidence that is similar in VCA patients with confirmed chronic rejection (Cendales et al., 2024; Kaufman et al., 2020). Based on submissions to the IRHCTT as of 2017, among 66 upper-extremity transplantations, nine cases of chronic rejection occurred, of which four led to allograft loss; and among 30 face VCA recipients, two chronic rejection cases were reported (Petruzzo et al., 2017). Two cases have been reported of patients who received a second face transplant following failure of their initial transplant due to chronic rejection (BWH, n.d.; Rosenberg, 2018). The Banff VCA international consensus working group reported that fibrosing changes can be caused by immune and nonimmune events and in certain cases they can overlap. The working group noted that histologic and chronic injury in a skin-containing VCA include skin and muscle atrophy, myointimal proliferation, loss of adnexa, vascular narrowing and nail changes (Cendales et al., 2008, 2024). A working definition has been proposed by the American Society for Reconstructive Transplantation and the International Society of Vascularized Composite Allotransplantation with respect to four chronic rejection categories (Kaufman et al., 2020). The diagnosis of chronic rejection in VCA has relied on clinical and pathological findings (Kanitakis, 2023). Clinical changes include allograft fibrosis, dyschromia and ischemic/necrotic ulcerations (Kanitakis, 2023), with clinical manifestations in face transplant recipients specifically including features of premature aging, mottled leukoderma accentuating suture

lines, telangiectasia, and dryness of nasal mucosa (Krezdorn et al., 2019). Pathological changes typically affect allograft vessels and manifest with allograft vasculopathy (i.e., myo-intimal proliferation and luminal narrowing of allograft vessels, leading to allograft ischemia) (Kanitakis, 2023). Unlike acute rejection, chronic rejection may not be reversible and results in the loss of function as well as in the loss or the removal of the allograft (Benedict and Barth, 2019; Kanitakis et al., 2016; Park et al., 2019; Robbins et al., 2019). Chronic rejection negatively impacts patient satisfaction (Hautz et al., 2020).

Antibody-mediated rejection

Earlier classification of VCA rejection described primarily T cell–mediated rejection. But as the number of VCA recipients has grown and longer follow-up data has become available through registries and translational studies, antibody-mediated rejection is under investigation in VCA (Blades et al., 2024; Cendales et al., 2024; Chandraker et al., 2014; Moris and Cendales, 2021). There have been reports on antibody-mediated rejection of both face and hand allografts (Azoury et al., 2021; Kiukas et al., 2023; Moktefi et al., 2021; Petruzzo et al., 2021). Similar to other solid organ transplants, diagnosis of antibody-mediated rejection in VCA presents challenges. Additional research needed includes histopathology, complement deposition, donor-specific antibodies, non-HLA antibodies, and biomarkers. The management of antibody-mediated rejection in a pre-sensitized face transplant recipient was performed with a combination therapy with plasmapheresis, eculizumab, alemtuzumab, and bortezomib (Chandraker et al., 2014). In 2024 a double hand transplant patient in the United Kingdom underwent therapeutic plasma exchange treatment to stop antibody-mediated rejection (NHS Blood and Transplant, 2024). This was the first reported use of this treatment in a bilateral hand transplant recipient. Per the report, the patient’s symptoms were reduced significantly, and an alternate immunosuppressant regimen was initiated to prevent further episodes of rejection.

Complications from Infections

Infections are a leading complication for VCA patients following transplantation (Hammond, 2013; Steinbrink et al., 2021; Uluer et al., 2016). Broad-spectrum antibiotics are given perioperatively depending on the anatomy of the allograft, the results of donor and recipient cultures, immunological status, and the organisms identified in the hospital microbiome among others (Hammond, 2013; Steinbrink et al., 2021). Environmental pathogens, opportunistic microbes, and reactivated endogenous viruses are all sources of possible infection for VCA recipients. In addition, each face and hand transplant contains unique anatomical and tissue specific flora

and, in the case of the hand, the donor’s occupation may play a role. Perioperatively, an opportunistic infection directly caused one fatality in a VCA recipient of combined face and bilateral hands (see footnote for additional considerations).4

Malignancies

Lifelong immunosuppression increases the risk for tumor formation and bloodborne cancers. As a result, malignancies occur at three- to fivefold higher rates among transplant recipients than in the general population and are the second most common cause of death among transplant recipients (Acuna, 2018; Au et al., 2018; Uluer et al., 2016). While these statistics are based on solid organ transplant recipients, a variety of malignancies have been reported among VCA recipients of face and hand allografts. Non-melanoma skin cancers, including squamous cell and basal cell carcinomas,

___________________

4 For example, donor tissues may be cultured for bacteria, fungi, and mycobacteria during the donor evaluation process (Milek et al., 2023; Steinbrink et al., 2021). The results of these cultures—and culture results of the recipient—can aid in developing the antibiotic regimen (Lindford et al., 2019). The identification of Staphylococcus aureus, Pseudomonas spp., Acinetobacter spp., and Candida are of special concern because they are associated with surgical site infections (Milek et al., 2023). Hammond (2013) reviewed the VCA literature for postsurgical infections and presented the findings as early, intermediate, and late posttransplant infections for face and, separately, for hand VCA. Each face transplant contains unique anatomical details. They almost all include mucosal tissue, but may also contain sinuses, which are all likely to be colonized with donor flora (Hammond, 2013; Milek et al, 2023). In the days and weeks following surgery, the most prevalent bacterial infections resulted in pneumonia, infections at the surgical site, and bacteremia. Reactivation of hepatitis C virus (HCV), herpes simplex virus (HSV), and cytomegalovirus (CMV) have all been reported. During the period from 2 to 9 months following transplant surgery, CMV and other viral infections caused the greatest number of complications in a face VCA recipient. Those at the greatest risk were recipients that tested negative for CMV with a CMV+ allograft. Bacterial infections reduced in frequency compared with the early posttransplant period, though those that were recorded were primarily nosocomial. Late-stage microbial infections following VCA were predominantly viral reactivation of HSV and CMV, community-acquired infections, and face-specific infections such as parotitis and conjunctivitis. Reports of bacterial infections were uncommon in hand transplant recipients in the early postsurgical phase, while reactivation of HSV and CMV were reported most frequently. Bacterial and fungal mycotic aneurysms of the anastomotic blood vessels have also been reported (Steinbrink et al., 2021). During the intermediate phase following hand VCA, viral infections were most prevalent. These included varicella zoster virus reactivation, human papillomavirus warts, and CMV disease and viremia. With proper care and management of the hand allograft, reports of late-stage infections were rare. Patients whose occupations or hobbies exposed them to high concentrations of environmental microbes, such as gardening, farming, or fishing, were at increased risk of infection for particular microorganisms (Milek et al., 2023; Steinbrink and Wolfe, 2020; Steinbrink et al., 2021). In addition, donors with similar occupations and donors whose cause of death was drowning presented a similar risk of transferring large numbers of specific environmental microbes in the allograft (Steinbrink and Wolfe, 2020; Steinbrink et al., 2021).

have been reported (Cavadas et al., 2011; Kanitakis et al., 2015; Khalifian et al., 2014; Landin et al., 2010). At the time that this report was written, posttransplant lymphoproliferative disorder (PTLD) has been reported in four VCA recipients, including two who were confirmed with an EBV-related B cell lymphoma and a third who developed an EBV-negative B cell lymphoma more than 10 years post transplant, with the fourth being submitted to the IRHCTT with few details (Khalifian et al., 2014; Petruzzo et al., 2010; Uluer et al., 2016; Zaccardelli et al., 2024). A recipient of a face allograft developed small-cell lung carcinoma 10 years post transplant, which, despite prompt treatment, recurred and was eventually fatal (Morelon et al., 2017).

Renal Dysfunction and Metabolic Disease

Decreases in kidney function and kidney transplantation due to the use of CNIs have been reported in face and hand transplant recipients (Krezdorn et al., 2018).5 A retrospective study of 99 face and hand VCA recipients revealed a decline in renal function, with a significant drop in year one post transplant (Krezdorn et al., 2018). Univariate linear mixed-effects models indicated that the doses and levels of tacrolimus were major factors in decreasing renal function. Although lowering of the tacrolimus levels after 1 year resulted in slight improvements in renal function, renal function remained below pretransplant levels (Krezdorn et al., 2018). VCA transplant recipients—as with other solid organ transplant recipients—are at risk of metabolic complications caused primarily by their immunosuppression regimen. Hyperglycemia and diabetes, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and other complications have been reported in VCA (Dwyer et al., 2012, Milek et al., 2023; Wells et al., 2022).6

___________________

5 For both VCA and nonrenal solid organ transplant recipients, there is evidence that diabetes, hypertension, chronic inflammation, and hepatitis C infection are contributory factors to the overall risk of chronic kidney failure (Bloom and Reese, 2007; Krezdorn et al., 2018; Ojo et al., 2003).

6 In a 2017 analysis of face and hand transplants reported to the IRHCTT, “the majority of the recipients presented metabolic complications (41.5 percent experienced transient hyperglycemia, which was not reversible in 23 percent of cases, and 3 percent of them required insulin; 26 percent of the patients developed increased serum creatinine values with two cases of end-stage renal disease requiring hemodialysis and one of them underwent kidney transplantation; arterial hypertension, Cushing’s syndrome, aseptic necrosis of hip with replacement, and serum sickness were also reported)” (Petruzzo et al., 2017, p. 296).

REHABILITATION

“Rehabilitation must be emphasized and supported as being at least as important to the patient’s outcome as the surgery … and affirmed as a life-long participant.”

— Bilateral hand transplant recipient, written testimony to the committee

Rehabilitation following any surgical procedure is a crucial part of the recovery process and its outcomes. For face and hand transplant recipients, rehabilitation is paramount because of the allographic nature of the transplant, the time it takes for reinnervation of muscles and other tissue, and the vital and complex roles that our hands and face play in who we are, how we are perceived by others, and our activities of daily life. For all those reasons, the rehabilitation process begins with preoperative assessments that are used to create a treatment plan, which will commence shortly after the transplant surgery is complete (see Chapter 4 for details on the assessment process). Functional recovery extends over years and thus so does rehabilitation. Throughout the process, a patient’s rehabilitation team regularly adapts treatment approaches to prevent and manage complications and enhance techniques to maximize functional recovery. Table 5-4 lists techniques that are typically used by occupational and physical therapists, speech–language pathologists, and other professionals on the rehabilitation team during the rehabilitation of face and hand transplant recipients. The protocols and timing of therapy modalities varies depending on patient needs (e.g., level of upper extremity transplant or extent of facial reconstruction) and the preferences of the individual VCA rehabilitation centers. Rehabilitation for face and hand transplant patients occurs in multiple phases, which can be broadly divided into initial, intermediate, and late (Fitzpatrick et al., 2022).

Rehabilitation for Hand Transplant Recipients

For hand transplants, rehabilitation focuses on range of motion, dexterity, and sensation. The level of the transplant, tissue atrophy, and type of reconstruction are key factors affecting the rehabilitation (E. Bueno et al., 2014).

TABLE 5-4 Rehabilitation Techniques for Face and Hand Transplant Recipients

| Therapy Modalities | Description | Face, Hand, or Both |

|---|---|---|

| Splinting | Used to protect transplanted tissues and to promote healing shortly after transplant. | Hand |

| Range of motion exercises | Used to promote motor function recovery of face, neck, arms, wrists, hands, or fingers. | Both |

| Edema and scar management | May use static compression combined with massage and gentle motion to prevent adhesions. | Hand |

| Strengthening/fitness conditioning/muscle therapy | Used to stimulate muscles during recovery using weights, Therabands, functional hand use, facial expression training, muscle relaxation and stimulation, and mirror exercises. | Both |

| Activities of daily living | Used to train and evaluate patient’s independence and function, such as eating, using the restroom, working, and patient interests/hobbies. | Both |

| Speech therapy | Trains patient how to regain functional control of lips to assist with speech, swallowing, and facial expressions. | Face |

SOURCES: Data from Boczar et al., 2023; E. Bueno et al., 2014; Dixon et al., 2011; Levy-Lambert et al., 2020; as well as submitted protocols (see public access file).

Initial and Intermediate Rehabilitation

Initial treatment after hand transplantation generally focuses on managing edema, gentle range-of-motion exercises, and splinting and orthosis fabrication and management (Boczar et al., 2023; E. Bueno et al., 2014; Mendenhall et al., 2020). Multiple sessions, which can total 4 to 6 hours per day, take place during the initial weeks that patients typically remain in acute hospital care (E. Bueno et al., 2014; Johns Hopkins, n.d.; Mendenhall et al., 2020; Severance and Walsh, 2013). In the next phase— intermediate rehabilitation—patients may be transferred to a different facility to continue therapy daily. The intermediate phase usually lasts several months, depending on the type of hand transplant (unilateral/bilateral), level of transplantation, degree of needed complication prevention and care management, and monitored progress of the patient. Treatments during intermediate rehabilitation include active range-of-motion exercises, cognitive training, and more activities of daily living (ADLs) exercises.

Late-Stage Rehabilitation

Late-stage rehabilitation can last for years after the patient returns home. If that home is far from the transplant center, a rehabilitation transition care plan will be required with a well-organized “handoff” between therapy teams. Patients may feel anxious about the switch to a new team and new settings. Thus, the handoff ideally includes detailed and granular discharge assessments and instructions, including guidance for setting goals and maintaining regular communication among the teams. The instructions can also include recommendations on splinting, exercises, and activities to focus on based on the patient’s adherence and dedication in therapy sessions and with at-home rehabilitation (Severance and Walsh, 2013). During the late-stage phase, sessions will gradually decrease in frequency and duration, though the specifics will depend on patient adherence and progress. Rehabilitation courses are patient-specific, adaptable, and dependent on surgical factors and type of reconstruction.

Muscle actions of the hand and wrist can be defined as either extrinsic or intrinsic. Extrinsic muscle action is defined as activation of muscles that originate from the forearm that move the wrist and hand (Okwumabua et al., 2019). Intrinsic muscles are responsible for functions such as grip and pinch strength (Dawson-Amoah and Varacallo, 2019). When extrinsic muscles are native to the recipient, then extrinsic motor function is preserved (Bueno et al., 2014). Intrinsic motor function may appear around 9 months post surgery but more typically is seen beginning at 12 months (Bueno et al., 2014; Lanzetta et al., 2007). With the recovery of muscle function, patients can perform many more complex tasks, such as eating, driving, shaving, and riding a bicycle (Lanzetta et al., 2007).

Though it is possible to establish standardized planning for rehabilitation, each patient will benefit from an individualized treatment approach. Improved outcomes can be demonstrated based on functional assessments, quality-of-life (QoL) surveys, and psychosocial evaluations. Most patients recover protective sensations—the ability to detect pain, heat, cold, and gross tactile feelings—which can be key to improved safety and independence (Lanzetta et al., 2007). Numerous assessment tools are available to the rehabilitation team, with many adapted from use in replantation patients (see Chapter 6). In the VCA community, there is still a lack of consensus about some aspects of rehabilitation protocols, such as the timeline of initial rehabilitation post surgery (Longo et al., 2024). To improve the ability to characterize rehabilitation treatments across disciplines, the Research Treatment Specification System was developed. The Research Treatment Specification System is a framework that describes how treatment leads to functional change in rehabilitation patients (Dijkers, 2019; Van Stan et al., 2019) and may be helpful to use as standardized protocols are developed.

Rehabilitation for Face Transplant Recipients

The rehabilitation management and recovery of the face transplant recipient are complex. Depending on the injuries, goals may include regaining intelligible speech, regaining ability to make facial expressions, and sensory recovery as well as breathing and eating without assistance. Our facial features from our hair to our eyes, nose, and lips to the shape of our jaw and cheeks are powerful communicators of who we are, how we feel about ourselves, and how we move through the world. A face transplant recipient has to reestablish all of these complex feelings and attitudes while also addressing the critical functions that various parts of the face provide, such as chewing and swallowing, breathing, smelling, seeing, and hearing, along with aural and nonverbal communication. In addition, patient goals and outcomes may look different depending on the level of transplantation and what area of the face is most affected. Rehabilitation protocols will vary based on whether the transplant is soft tissue, soft tissue and bone, partial mid-face, or scalp. Rehabilitation treatment for a partial face transplant, for example, includes passive and active facial exercises focused on the lips and mouth to enhance eating and drinking abilities (Dubernard et al., 2007).

In addition to functional rehabilitation therapy, psychosocial therapy is an integral part of rehabilitation for a face transplant recipient (Brill et al., 2006). Immediately post transplant, patient behavioral and social interactions are closely monitored. Patients may be encouraged to look at their new face in the mirror to begin psychosocial recovery. Long-term care includes helping patients adapt to their new faces and promoting a healthy body image (Lemogne et al., 2019). Additionally, studies have shown that the recovery of facial expressions helps improve nonverbal communication and social interactions (Topçu et al., 2018). See Chapter 3 for more information about psychosocial considerations.

Initial and Intermediate Rehabilitation

In the initial phase of rehabilitation, the focus is on achieving medical stability, beginning the recovery process, and promoting healing both physically and psychologically. Additionally, initial rehabilitation focuses on basic functions such as breathing, eating, drinking, and comfortably sleeping (La Padula et al., 2022). In this initial stage of face transplant rehabilitation, active range-of-motion and flexibility exercises are restricted to optimize healing and preserve tissue integrity (Dixon et al., 2011).

The intermediate phase of rehabilitation focuses on facial exercises to regain control of mouth and lip muscles, eye muscles, and other facial muscles (Dixon et al., 2011). Larger movements may be restricted initially to prevent allograft failure or infection (La Padula et al., 2022). There is

also a focus on higher-level functional activities of daily living and cognitive training of sensory functions (Dixon et al., 2011). During the intermediate phase, rehabilitation of facial muscles is a main goal, in addition to activities of daily living such as blowing the nose and washing the face (La Padula et al., 2022). In the later stages of this phase, the rehabilitation team will prepare the patient for community re-entry and life at home.

Late-Stage Rehabilitation

During the later stages of rehabilitation, sensory stimulation and muscle strengthening may be used to improve functional outcomes and electromyograph biofeedback, mirror training, passive stretching, and massage can be used to help rehabilitate individual muscles (La Padula et al., 2022). Speech and the ability to smile may be given specific attention, as muscles around the mouth may have to be retrained, depending on the presence of a tracheotomy (La Padula et al., 2022). Functional outcomes in face transplants that improve with rehabilitation include breathing, sense of smell, ability to eat, facial expressions such as the ability to smile or express other emotions, and sensation (Fischer et al., 2015). Patient adherence with facial muscle exercises and speech therapy increases the chance of regaining optimal speech function and facial mobility (Siemionow and Gordon, 2010).

Once patients return home, they may continue to use outpatient rehabilitation services for sensory processing, olfaction, and facial expression therapy and to use adaptive equipment for at-home exercise programs (Dixon et al., 2011). Returning home and becoming increasingly independent following transplant can elicit a range of feelings. The rehabilitation team is critical in helping a patient navigate those feelings and make a successful transition. Psychosocial coping strategies for reintegration into the community may be used. Additionally, rehabilitation may include the instruction to support groups or other community resources (Dixon et al., 2011).

Challenges Hand and Face Transplant Recipients Encounter During Rehabilitation

Perhaps one of the greatest challenges of rehabilitation is maintaining a patient’s focus and dedication to the rigorous and prolonged therapy regimen following transplantation. For example, a study that examined psychosocial data submitted to the IRHCTT with a supplemental psychosocial survey found a negative association between participation in occupational therapy and transplant removal; recipients who did not “actively participate

and perform exercises at home” (N = 15, 35 percent) had a nearly three-fold risk of allograft removal compared with those who actively participated in therapy (Kinsley et al., 2020, p. 2). Long-term rehabilitation is necessary as results can be seen years after transplant. Additionally, decrease in function can be a sign of chronic rejection resulting in allograft loss. The longitudinal assessment and monitoring of function is critical to quantify outcomes (see Chapter 6). Other challenges for the patient and caregivers are setting realistic goals and adhering to the precautions set by the rehabilitation team so that as they exercise and go about their daily lives, preventable injuries and complications are avoided (Dixon et al., 2011). As noted above, once a patient has returned home, there can be challenges transitioning to a new rehabilitation team and maintaining social and psychosocial support. Additionally, patients may find it difficult to cover their portion of the costs of rehabilitation sessions, which may interfere with access to care. Depending on where they live, patients may need to travel long distances to see various physicians, including returning to their VCA transplant center (Rifkin et al., 2018b). These travel needs can be burdensome to some patients, requiring time away from work, having access to childcare, and having to cover the expenses associated with travel. Based on patient testimony at the committee’s public webinars and on discussions with the study’s lived experience consultants, even when an institution has grants for postoperative care, these can run out after a set period while the care of a transplant patient is for life. Even with insurance, the actual cost of rehabilitation can be a significant burden to patients and their caregivers.

PSYCHOSOCIAL CARE MANAGEMENT

“Continuous support should be available and readily available even years after.”

— Bilateral hand transplant recipient, written testimony to the committee

The initial psychological challenges that recipients may encounter include difficulties integrating the face or hand transplant into their existing body image and identity, dealing with the reactions of friends and families to physical change, and anxiety related to possible rejection or loss of the transplant and a return to the previous disability. Throughout the initial

recovery period, psychosocial challenges can arise. In the first 2 weeks post transplant, patients may experience high levels of anxiety, delirium, denial or avoidance, or re-emergence of the initial trauma that led to the need for a transplant (Brill et al., 2006). This may be treated with medication or exercises such as mirror therapy. Visits with the patients support system and social activities may also help during the initial posttransplant period (Brill et al., 2006).