Advancing Face and Hand Transplantation: Principles and Framework for Developing Standardized Protocols (2025)

Chapter: 8 Data Management and Registry Development

8

Data Management and Registry Development

“I don’t mind data being collected. In fact, I want it to be collected because I wanted people to benefit from my experience.”

—Bilateral hand transplant recipient, lived experience consultant testimony to the committee

“With so many variables, [VCA] is unlike any other solid organ transplant, and we need a much larger sharing of data to be able to standardize the protocols.”

— Dr. Mohit Sharma, Amrita Hospital, presented testimony to the committee at the March 22, 2024, public webinar

“[W]ith a small number of patients, a lot of what we’re doing … is getting the natural history, they’re finding the biomarkers, they’re understanding the course of the disease.”

— Dr. Tiina Urv, Rare Diseases Clinical Research Network, presented testimony at the May 29, 2024, public webinar

“Our patient registry is a crown jewel, helping improve clinical outcomes as well as advance the science.”

— Erin Tallarico, Advanced Lung Disease Transplant Program, Cystic Fibrosis Foundation, presented testimony at the May 29, 2024, public webinar

An essential driver of research and clinical practice is data stewardship. Data storage, sharing, collection, analytics, and access are dependent on the proper and consistent use of data management principles. Good data management is a key factor in knowledge discovery and innovation. The FAIR principles, formally published in 2016, are a set of guidelines aimed at improving the findability, accessibility, interoperability, and reusability of digital data (Wilkinson et al., 2016). When the FAIR principles are followed, researchers find it easier to navigate the burgeoning landscape of big data and processing. These principles have been used successfully in the health data domain (Inau et al., 2021, 2023), such as in rare disease registries (Hageman et al., 2023).

Data management systems can be used to collect and monitor patient information. Health data management has been propelled forward by the advancement of health technologies and electronic record keeping (Ismail et al., 2020). A 2020 scoping review identified seven requirements for every health care data management system: (1) quality medical record data; (2) real time data input and access; (3) patient access to health data; (4) data sharing with patients, families, medical organizations, and the government; (5) data security to protect patient data from cyberattacks; (6) privacy of patient identity; and (7) public insights with safeguards to protect patients and their health information (Ismail et al., 2020).

A registry offers a beneficial tool for health data management. Many of the presenters who described clinical networks at the May 29, 2024, webinar1 said that data collected in registries helped advance the work of their clinical networks. According to a representative of the Blood & Marrow Transplant Clinical Trials Network, that network’s biggest asset is “being embedded in a high-quality, longitudinal registry of real-world data,” and that a registry is a “built-in mechanism for long-term follow-up of patients treated” through the clinical network. A patient registry focuses on patient data and related health information. A critical step in designing a patient registry is the selection and definition of patient outcomes (Gliklich et al., 2020c). (See Chapter 6 for more information on core face and hand transplant outcomes that could be collected in a registry.) Although there is no single definition of a patient registry, Gliklich et al. (2020c) states:

A patient registry is an organized system that uses observational study methods to collect uniform data (clinical and other) to evaluate specified outcomes for a population defined by a particular disease, condition, or

___________________

1 See https://www.nationalacademies.org/event/42578_05-2024_principles-and-framework-to-guide-the-development-of-protocols-and-standard-operating-procedures-for-face-and-hand-transplants-webinar-3 (accessed July 9, 2024).

exposure and that serves one or more stated scientific, clinical, or policy purposes.

Creating and implementing a registry is a multifaceted process, including the intricacies of dealing with coding languages and data collection tools, as well as addressing ethical and legal concerns to safeguard data privacy while facilitating sharing and reuse. Effective governance and management are essential to balance the diverse interests of patients, health care professionals, researchers, policy makers, and other community partners (Hageman et al., 2023). Registries that are properly designed and effectively executed can provide a real-world perspective of clinical practice, safety, patient outcomes, and comparative effectiveness (Gliklich et al., 2020c).

The Clinical Organization Network for Standardization of Reconstructive Transplantation’s (CONSORT’s) statement of work includes items related to data management and a registry (see Box 8-1). These items are to be led, organized, and staffed by Navitas Technologies.2 To the committee’s understanding, these activities and the electronic clinical trial management system—VCA-NET—are in the preliminary stages, and Navitas is waiting for the standardized domains to be developed through the standardization of protocols process before entering beta testing. This chapter provides information that the committee believes will be helpful at this stage of development.

A centralized vascularized composite allotransplantation (VCA) registry will be a valuable asset for CONSORT throughout the duration of the network, provided that it is constructed so that it is easy to work with, uses standardized data elements, and links to powerful analytical tools for data evaluation. One of the benefits of creating a VCA patient registry is the ability to easily share data and outcomes between CONSORT network sites, thereby improving future clinical care. In addition, centers that are not participating in CONSORT may request access to data to learn from the procedures performed in the clinical network, as well as share data to

___________________

2 See https://navitastech.com/overview (accessed December 24, 2024). As part of the clinical network award mechanism, a for-profit entity was a requirement of the Research Other Transaction Award (ROTA): “As a matter of DOD policy, ROTAs may only be awarded when one or more for-profit firms are to be involved either in the: (1) performance of the research project(s) or (2) commercial application of the research results. A consortium should either include, collaborate with, or involve one or more for-profit firms (e.g., pharmaceutical company to provide medication, rehabilitation clinic to provide services to recipients, etc.) in addition to state or local government agencies, institutions of higher education, or other nonprofit organizations. For the FY22 Clinical Network Award, the for-profit firm may be involved in either Phase 1, Phase 2, or both phases of the award.” Fiscal Year 2022 Reconstructive Transplant Research Program Funding Opportunity Description. See https://cdmrp.health.mil/funding/pa/HT9425-23-RTRP-CNA-GG2.pdf (accessed December 26, 2024).

be included in the registry, thereby increasing data collection opportunities. Ideally, a face and hand transplant registry would collect information routinely from hospitals, patients, and clinical teams across all active VCA transplant centers.

BOX 8-1

Data Management and Registry Components of CONSORT Statement of Work

Phase I Specific Aim 3: Design, develop and deploy VCA-NET, which is a purpose-built electronic clinical trial management system (eCTMS), with standardized domains that incorporate the unique complexity of hand and face transplant metrics.

Major Task 6: To create for the first time ever in reconstructive transplantation, a database customized for upper extremity or craniofacial VCA, to facilitate utilization and compliance with standardized data reporting across Network Sites (National and International).

Milestone #14: Complete preliminary alpha testing of the multiapplication programming eCTMS dashboard of VCA-NET across Network Sites approved for Phase II.

Milestone #15: Alpha-test cloud-based, seamless, HIPAA-secure, regulatory-compliant access to standardized data inputs across Network sites.

Milestone #16: Deliver to the CONSORT Trial, the first independent, decentralized and deconflicted database for VCA data, alpha/beta tested early Phase II (during first NCE), ready for site-wide implementation in Phase II across US and International Sites.

Phase II Specific Aim 4: Assess and validate standardized protocols and SOPs for hand and face transplantation in multi-institutional clinical trials across select National Network Sites.

Milestone #17: Transition VCA-NET into a Cloud based VCA Registry after study completion.

SOURCE: CONSORT statement of work, submitted to the committee by CONSORT.

NOTE: HIPAA = Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act; NCE = no-cost extension.

CURRENT REGISTRIES THAT COLLECT FACE AND HAND TRANSPLANT DATA

Currently, there are two major data registries for data on face and hand transplants—the U.S.-based Scientific Registry of Transplant Recipients

(SRTR), which includes mandatory data submissions collected by the Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network (OPTN), and the International Registry on Hand Composite Tissue Transplantation (IRHCTT), which stores voluntary data submissions by participating transplant centers worldwide.

The SRTR collects and analyzes transplantation data, including VCA, in the United States, which are largely collected by the OPTN through UNet (SRTR, n.d.; UNOS, n.d.). UNet has four distinct subcategories: Waitlist, which adds transplant candidates to the national waiting list; DonorNet, in which organ procurement organizations (OPOs) enter potential donor information and matches are made; TransNet, which ensures that organs are labeled, packaged, and matched corrected; and TIEDI, which is used to collect post-transplant data (UNOS, n.d.). Data have been collected on U.S.-based VCA transplants since 2014 (when VCA was included in the Final Rule). As noted in Chapter 2, when data submitted to the OPTN database are incomplete, the data analyses that SRTR can perform are affected (Hernandez et al., 2024). Historically, data have often been incomplete, though the quality of submitted data has been improving.

While the IRHCTT collects data on individual procedures and from institutional publications and case reports, the registry receives information only from transplant centers that voluntarily submit their information. Among institutions that do contribute, data submissions are often incomplete. The data collection generally includes recipient general conditions (e.g., patient and allograft survival, patient satisfaction, rejection episodes), recovery of face function, and outcomes based on two functional recovery scoring systems for hand transplant recipients—the Hand Transplantation Score System scores and Disability of the Arm, Shoulder, and Hand scores (IRHCTT, n.d.). At the time of its most recent report in 2017, the IRHCTT contained data from 66 upper extremity allotransplantations performed around the world, with recorded follow-up times ranging from 2 months to 18 years, and 30 cases of partial or total face allotransplantations, with recorded follow-up times ranging from 15 months to 11 years (Petruzzo et al., 2017). Data that are housed within the IRCHTT registry are only accessible to those who have submitted information. This typically consists of physicians who have performed a procedure. However, there are multiple groups who could benefit from accessing patient registries, such as researchers, patient advocacy organizations, potential payers, and drug manufacturers (Gliklich et al., 2020c). The Rare Diseases Registry Program recommends establishing eligibility criteria to determine who can join and access a registry. That program developed a participant criteria checklist based on location, language, and diagnosis (RaDaR, n.d.-d). To protect patient privacy, different levels of access may be appropriate for different interested parties.

For CONSORT, rather than starting a new registry from scratch, it would be preferable for the registry/data management system to coordinate and build upon the SRTR and the IRHCTT, as these registries have been collecting data on face and hand transplants for years and will presumably continue to do so. A VCA patient registry may also benefit from the inclusion of all individuals who are evaluated for a face or hand transplantation to increase data collection opportunities, allow for outcome comparison, and help refine patient selection criteria.

BEST PRACTICES IN REGISTRY DEVELOPMENT AND EXEMPLARS

Some factors to consider when developing a patient registry are who the target audience is, how long the registry will be in service, and what funding is available to both develop and maintain the registry. Initial steps in registry development include the creation of specific registry objectives and goals, the identification of stakeholders, and the creation of a team responsible for registry implementation (Gliklich et al., 2020a). When well planned and executed, these initial steps can help the registry avoid excessive data collection and focus on collecting the data necessary to answer the research questions that are prioritized. The Rare Diseases Registry Program, which has created guidance tools on best practices for registry development, recommends creating a written governance or project plan to oversee these first steps. Project plans can include elements such as cost management, staff management, risk management, and communication strategies (Gliklich et al., 2020a). A governance plan can also help guide with whom and how data will be shared as the registry develops (RaDaR, n.d.-a).

Once the registry has been established, timelines and goals may change. Planning for challenges and delays within the initial timeline may make it easier to overcome unanticipated obstacles (RaDaR, n.d.-a). Additionally, it is a best practice to design a strategy to periodically evaluate the effectiveness of the registry. These reviews should be undertaken by key community partners and, if helpful, include an analysis by outside experts. These reviews are especially important for registries that will be in use for many years (Gliklich et al., 2020a), because participants, objectives, data categories, and technologies will change over time. Periodically reevaluating the registry’s goals can also help to assess the success of the registry by determining whether data are being used and collected efficiently, whether the data are high quality, and whether meaningful conclusions can be drawn from the registry (RaDaR, n.d.-c).

An international study of 13 registries concluded that making registry outcome data transparent to both practitioners and the public can assist medical professionals in identifying and sharing best clinical practices,

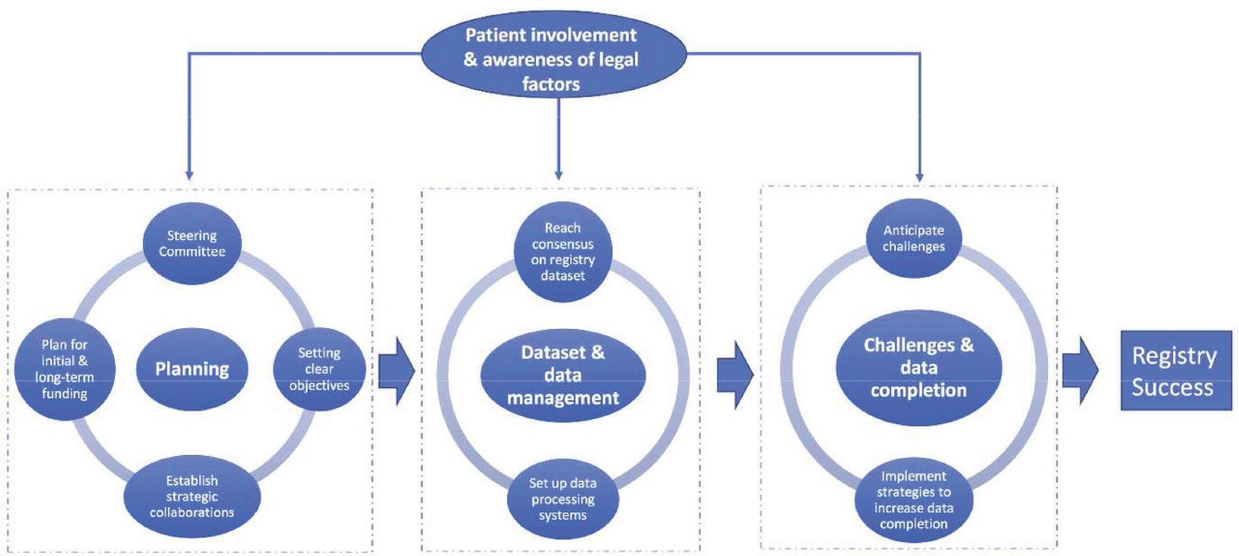

thereby improving patient outcomes (Larsson et al., 2012). Additionally, active engagement with the clinical community was noted as critical for securing broad support and participation of practicing clinicians (Larsson et al., 2012). A systematic review of surgical registries in the United Kingdom found that successful registry development requires a steering committee, clear registry objectives, planning for sustainable funding, strategic national collaborations among key community partners, a registry management team, consensus meetings related to the registry dataset, established data processing systems, anticipating conflicts, and application of strategies to facilitate data completion (Mandavia et al., 2017) (see Figure 8-1). Additionally, registry development is not a linear process—over time, the scope of a registry often evolves to include broader populations, incorporate additional data items, shift focus to different geographical regions, or address new research questions (Gliklich et al., 2020c).

Data from a centralized, accessible repository can also be used to help plan clinical studies. During the May 29, 2024, public webinar, the committee heard from two registries—the Limb Loss and Preservation Registry (LLPR) and the Cystic Fibrosis Foundation Patient Registry—that use their data to facilitate research studies and clinical trials. They reported that using a registry to plan clinical studies reduces costs, avoids duplicative data collection, and assists with identifying and recruiting potential patient participants.

The LLPR collects information from multiple sources. Hospitals provide information on patient demographics, level and side of amputations, patient encounters, comorbidities, social determinants of health, facility, provider, payer, and physical function scores from the Patient-Reported Outcome Measures Information System; providers submit data on activity level, prescription, L-codes, and prosthetic and orthotic components; patients send in information on their mobility and functional status, socket comfort and limb health, quality of life, safety, and prostheses use; and a cloud-based disposable sensor worn by patients uploads real-world functional outcomes data. Given the similarities between LLPR patient participants and hand transplant recipients, building upon and collaborating with the LLPR may be beneficial for CONSORT to consider.

The Cystic Fibrosis Foundation Patient Registry was started in 1966 by the Cystic Fibrosis Foundation to track cystic fibrosis patients, including patient demographics, health status, and survival. The registry was created to collect and maintain data on diagnosis, treatment, and outcomes and has evolved over the years to allow for new data types, fields, and other capabilities, including advances in new technology (Knapp et al., 2016; Labkoff et al., 2024). Inclusion criteria include diagnosis with cystic fibrosis or a related disorder, care at an accredited care center program, and provision of informed consent (Knapp et al., 2016). As of 2016, the Cystic Fibrosis

Foundation Patient Registry includes 81–84 percent of all individuals with cystic fibrosis in the United States, and the Cystic Fibrosis Foundation has used funding for cystic fibrosis care centers to increase the number of patients enrolled and the completeness of the data in the registry (Knapp et al., 2016). Five categories of electronic data are collected through a web-based portal: demographics, encounter, diagnosis, annual review forms, and care episode. Staff, patients, and families enter available data into medical records or in patient forms (Knapp et al., 2016). Key fields are required so that a minimum amount of information is collected for a given form, and there are verification and data-checking procedures. Other exemplary U.S.-based registries include the American College of Cardiology’s CathPCI Registry3 and the National Cancer Institute’s Surveillance Epidemiology and End Results database.4

INFRASTRUCTURE AND SUSTAINABILITY

As with any digital data management system, a patient registry requires a robust information technology (IT) infrastructure. A VCA registry will likely use electronic health records (EHR) data and patient-reported data from VCA centers across the United States and potentially around the globe. This will require a fully interoperable data environment, enabling data from multiple EHR systems and numerous patient input platforms to be imported, extracted, transformed, and loaded in a seamless manner. Building and maintaining such a system will face multiple challenges. A face and hand transplant registry will likely be used both for evaluating and improving clinical care and for research purposes, and these two focus areas may have different IT infrastructures (Gliklich et al., 2019). Thus, integrating infrastructure that meets both needs is important. Different institutions may have different data governance policies, which can create a web of barriers when importing and integrating EHR data from multiple sources (Gliklich et al., 2019).

The development of standardized protocols and standard operating procedures for face and hand transplant will mitigate some of the registry IT infrastructure challenges. For example, the use of standardized patient inclusion and exclusion criteria by every VCA center will lessen the chance that different data values are used for the same event or fact, as seen in other disciplines (Gliklich et al., 2019). The use of standard operating procedures should also improve data quality by ensuring that data added

___________________

3 See https://cvquality.acc.org/NCDR-Home/registries/hospital-registries/cathpci-registry (accessed October 7, 2024).

4 See https://seer.cancer.gov/ (accessed October 7, 2024).

to the registry are complete and accurate, regardless of which VCA center submits the data.

Little research has been done about the use of big data and artificial intelligence (AI) in registries. A study of ophthalmic clinical registries found that the use of AI is still relativity low (Tran et al., 2024). While new technologies, such as AI, propagate and develop, registry developers can prepare systems that will be able to support large amounts of patient data and have the flexibility to innovate. In addition to the infrastructure necessary to support the development and implementation of the patient registry, sustainability is vital to ensure that data within the registry remain secure for a long period of time. As noted in Wilkinson et al. (2016), “data stewardship includes the notion of ‘long-term care’ of valuable digital assets, with the goal that they should be discovered and re-used for downstream investigations, either alone, or in combination with newly generated data” (p. 1). It is important that, prior to establishing a registry, a sustainability plan is put in place with a focus on funding, ownership, partnerships, security audits, and quality control (Boulanger et al., 2020). Like other aspects, this sustainability plan should be assessed on a frequent basis to ensure goals are being met (Boulanger et al., 2020). While initial funding is necessary for the formation of the registry, a dependable longer-term funding stream is essential for the registry to be sustainable over time (Hageman et al., 2023). Many rare disease registries receive funding from private companies, such as pharmaceutical or technology companies (Hageman et al., 2023). Establishing registry use or access fees to pay for registry staff and maintenance can provide an additional funding stream (NCATS, n.d.).

SPECIFIC CONSIDERATIONS FOR PATIENT-REPORTED OUTCOMES IN REGISTRIES

As discussed in Chapter 6, patient-reported outcomes (PROs) are critical to collect because PROs complement the information provided by objective clinical data. However, there are challenges both with determining what kinds of patient data to include and in the analyses of subjective PROs in patient registries, particularly rare disease registries (Gliklich et al., 2020d; Solomon et al., 2019). Rare diseases will not typically have a condition-specific metric, and the creation of a new metric poses additional challenges (Gliklich et al., 2014) (see discussion in Chapter 6). There are multiple types of patient outcome measures, but as there is no unique validated measure for face and hand transplantation, a registry will have to either collect data using existing measures or develop a new measure to use in the registry. Even once the PROs are decided on and agreed upon, the management and collection of data over time can be difficult. When planning and developing the VCA registry, it would be helpful to determine what PROs

will be collected based on input from patients, caregivers, health service researchers, clinicians, and other community partners. It is often easier to remove additional outcome measurements later in the process than to add additional measurements as part of data collection efforts after the registry has already been launched.

A recurring challenge with including PROs in registries is the burden that these data collections place on patients. Face and hand transplant recipients already complete multiple quality-of-life surveys, and some recipients have expressed discomfort with how often they would need to input their data into a new registry.5 Patients may need to know what the time commitment will be for gathering specific PROs before agreeing to participate. Some studies recommend questionnaires every 3 months, completed either at home or at doctors’ appointments (Solomon et al., 2019). Analyses of other patient registries concluded that questionnaires should be brief and completed by patients at regular intervals, rather than relying on PRO data being collected during visits to the doctor (Franklin et al., 2013; Hazari and Walton, 2015; Mandavia et al., 2017).

Patient recruitment is another factor when gathering PROs. Patients undergoing clinical research are more likely to participate in registries based on the trust they have in their clinicians (Solomon et al., 2019). As face and hand transplant recipients spend a great deal of time with their multidisciplinary teams, trust will play a key role in their consideration for active participation in the registry. Once a VCA registry is developed, new transplant patients can be asked to provide data to the registry at the beginning of their transplant experience. In addition, it will be important to decide what data to collect on patients who were evaluated for transplant but not ultimately transplanted (see Chapter 4 for more information).

PATIENT DATA SHARING AND PRIVACY CONSIDERATIONS

“All that privacy stuff is very important to me. I think it comes with after the media coverage and stuff like that, I just became a little bit more recluse.”

— Bilateral hand transplant recipient, lived experience consultant testimony to the committee

___________________

5 Lived experience consultant testimony.

“Our data is what, getting sold? How does this work? It makes me really uncomfortable … [W]e don’t want to be sold.”

— Bilateral hand transplant recipient, lived experience consultant testimony to the committee

Patients with rare diseases, regardless of how severe their condition is or what socio-demographic background they have, generally support data sharing to enhance research and health care (Courbier et al., 2019). However, their willingness to share data is generally contingent on specific conditions to ensure their privacy, respect their choices, and address their need for information about how their data will be used. Collection, storage, and use of patient data is best done when patient privacy is always secure and protected. It is the legal and ethical thing to do, and without these safeguards patients may be unwilling to participate in the registry, limiting the registry’s impact and limiting the PROs that could be collected to improve clinical care.

Patients sharing their data with a registry require informed consent, which specifies patients’ rights concerning data privacy, transparency, and use. Getting informed consent ensures that patients are voluntarily agreeing to their data being reported. The consent process must explicitly describe the purposes of data in the registry and what the potential uses of the data may be, such as being analyzed in additional research projects (Gliklich et al., 2020b). McCormack et al. (2016) found that patients appreciated being asked to provide consent again when the purpose of the research shifts. They described consent as “a social agreement,” emphasizing that decisions regarding research should not be assumed to be automatically granted. In the event that patients wish to stop sharing their information with the registry, clear procedures for patients to withdraw from registry participation are needed (Gliklich et al., 2020b).

Transparency also influences patient participation in a registry. Allowing patients, caregivers, and other stakeholders to have a clear understanding of the registry’s objectives, data sources, funding, and governance (Gliklich et al., 2020b) can ease concerns about how the data within the registry will be used. Overall, protecting the data of patients who allow their data to be stored in a patient registry is crucial, and those leading the development of a registry have an obligation to minimize potential harms (Gliklich et al., 2020b).

While face and hand transplant recipients and caregivers have emphasized that they want future patients to benefit from their experiences, they

have also expressed a strong desire to be informed about where their data are being stored, whether they are being sold, and who may access them.6 While the Health Information Portability and Accountability Act protects patients’ identifiable health information in patient registries (Gliklich et al., 2020b), additional steps are needed to ensure patient privacy and reduce the risk of data breaches. Some registries design their infrastructure and security measures to meet the U.S. Food and Drug Administration standards for data integrity,7 including allowing only authorized users access to the password-protected online portal, installing robust firewall and intrusion detection systems, transferring data using a secure file transfer protocol, and processing, storing, and encrypting data to meet the standards of the Health Information Technology for Economic and Clinical Health Act8 (Knapp et al., 2016).

It is important to develop a data-sharing agreement regarding data ownership (Dolor et al., 2014). A best practice is to finalize the data-sharing agreement before patients and centers are asked to contribute and to ensure that the agreement addresses how patient confidentiality will be maintained, what information will be de-identified, and how this will be done (Dolor et al., 2014). The Rare Diseases Registry Program recommends that data protection plans clarify who has access to the data and how often data security protocols are updated. Furthermore, the program recommends that a breach response plan be created that details how to lock down the data system and notify participants in the event of a breach. Additional steps to reduce the risk of data breaches include implementing a secure access process, developing security guidelines, using automatic detection systems, and maintaining regular security updates (RaDaR, n.d.-b).

INVOLVEMENT OF INTERNATIONAL SITES

In the CONSORT statement of work tasks related to data management and registry development (see Box 8-1), international sites are called out specifically as participants in the envisioned registry. As seen in Chapter 2, many face and hand transplants occur outside of the United States; thus, much of the possible data to be collected and examined will likely be outside of the United States. However, as discussed in Chapter 7, international sites are not expected to participate in CONSORT as clinical network sites. Therefore, there is no mandate that international transplant centers

___________________

6 Lived experience consultant testimony.

7 Compliant with 21 C.F.R. part 11.

8 Health Information Technology for Economic and Clinical Health (HITECH) Act. Title XIII, Division A, and Title IV, Division B, American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009 (ARRA). Pub. L. 111-5, 42 U.S.C. §§ 201 et seq., 123 Stat. 226.

will follow the standardized protocols, including collecting outcomes in a standardized manner and reporting data according to the same standards that network sites have agreed to. There are different systems in place that may create challenges with data harmonization between national and international registries, such as inconsistent data collection and upkeep methods (Tabatabaei Hosseini et al., 2024). Additionally, there may be cultural differences across countries related to patient preferences and data considerations. However, harmonization should be strived for given the importance of international collaboration (Tabatabaei Hosseini et al., 2024) and the number of these transplants that are performed outside of the United States.

When considering the inclusion of international data in the registry, given the differing protocols and data collection methods used around the world (Tabatabaei Hosseini et al., 2024), it may be beneficial to take a country-by-country approach, with an eye toward confirming the validity of any submitted data that were not collected under the standardized protocols. While this will likely be time consuming, high-quality data are critical to any possible conclusions based on the culmination of data collected in the registry. Additionally, outreach by CONSORT to international transplant centers to encourage standardized reporting of outcome metrics based upon the agreed upon protocols may help alleviate these concerns and encourage high-quality data harmonization.

CHAPTER 8 KEY FINDINGS

A registry, among other data management tools, is a valuable tool for advancing face and hand transplantation. The existing SRTR and IRHCTT data repositories include information that would be valuable to any registry or data management system that CONSORT develops. Before the registry is created, several features should be developed and specified: a well-executed governance or project plan, a schedule for evaluating the effectiveness of the registry, and a sustainability plan that addresses the longer-term needs of a registry and establishes whom the registry is for, how the registry will be used, and how it will be sustainably funded. An effective registry is built on a robust IT infrastructure that can handle data from numerous transplant centers and patients, is designed to be secure, and adheres to the principles of findability, accessibility, interoperability, and reusability. There is a plethora of international data that are beneficial to include in a registry, but there will likely be issues with data harmonization, given the different cultural contexts and concerns with data quality. It will be critical that international data included in the registry be collected and reported according to high-quality data standards, even if the transplant center does not follow the standardized protocol developed by CONSORT.

PART III OVERARCHING CONCLUSIONS

Part III of the report presents the committee’s vision for the future of face and hand transplantation and a framework and principles that can guide CONSORT and the broader VCA community toward realizing that vision. The following overarching conclusions are based on the body of evidence and committee expertise. Experience has shown that these transplants have transformed patients’ lives and have the potential to better the lives of future patients. To optimize the chances for success, VCA patients and their caregivers require long-term follow-up care and support provided by a multidisciplinary team. For the continued maturation of face and hand transplantation, several things are needed, including standardized data collection using both generic and condition-specific measures, additional research to establish the principles underlying VCA-specific immunosuppressive regimens and rehabilitation protocols, and continued innovation of surgical techniques. Additionally, there must be strong leadership from experienced VCA transplant centers that understand and agree to the institutional commitment needed to longitudinally support these patients and their caregivers, and that will continue to pursue education and training to improve team competence and expertise. To develop and increase understanding of the benefits and risks of face and hand transplants, a registry is needed that permits easy access to timely information on outcomes, including long-term, standardized follow-up of mental, emotional, physical, medical, surgical, and social health.

The committee’s framework for the future of face and hand transplantation, as described in Chapter 7, will only be realized by sustained and concerted efforts over time. While much has been achieved, significant opportunities remain to advance VCA and improve care for selected individuals who can benefit from a face or a hand transplant. As the number of procedures grows, face and hand transplantation must be underpinned by ethical cornerstones; the cross-cutting dimensions of value, transparency, and equity; and the six principles in the committee’s vision: multidisciplinary and comprehensive care, accountability, sustainable funding, ongoing investigation on undefined areas, patient/family centeredness, and team competency.

REFERENCES

Boulanger, V., M. Schlemmer, S. Rossov, A. Seebald, and P. Gavin. 2020. Establishing patient registries for rare diseases: Rationale and challenges. Pharmaceutical Medicine 34(3):185–190.

Courbier, S., R. Dimond, and V. Bros-Facer. 2019. Share and protect our health data: An evidence based approach to rare disease patients’ perspectives on data sharing and data protection-quantitative survey and recommendations. Orphanet Journal of Rare Diseases 14:1–15.

Dolor, R. J., K. M. Schmit, D. G. Graham, C. H. Fox, and L. M. Baldwin. 2014. Guidance for researchers developing and conducting clinical trials in practice-based research networks (PBRNs). Journal of the American Board of Family Medicine 27(6):750–758.

Franklin, P. D., L. Harrold, and D. C. Ayers. 2013. Incorporating patient-reported outcomes in total joint arthroplasty registries: Challenges and opportunities. Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Reseach 471(11):3482–3488.

Gliklich, R. E., N. A. Dreyer, and M. B. Leavy. 2014. Rare disease registries. In Registries for evaluating patient outcomes: A user’s guide [internet]. 3rd edition. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality.

Gliklich, R. E., M. B. Leavy, and N. A. Dreyer. 2019. AHRQ methods for effective health care. In R. E. Gliklich, M. B. Leavy, and N. A. Dreyer (eds.), Tools and technologies for registry interoperability, registries for evaluating patient outcomes: A user’s guide, 3rd edition, addendum 2. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality.

Gliklich, R. E., M. B. Leavy, and N. A. Dreyer. 2020a. Planning a registry. In Registries for evaluating patient outcomes: A user’s guide [internet]. 4th edition. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality.

Gliklich, R. E., M. B. Leavy, and N. A. Dreyer. 2020b. Principles of registry ethics, data ownership, and privacy. In Registries for evaluating patient outcomes: A user’s guide [internet]. 4th edition. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality.

Gliklich, R. E., M. B. Leavy, and N. A. Dreyer. 2020c. Registries for evaluating patient outcomes: A user’s guide [internet]. 4th edition. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality.

Gliklich, R. E., M. B. Leavy, and N. A. Dreyer. 2020d. Selecting and defining outcome measures for registries. In Registries for evaluating patient outcomes: A user’s guide [internet]. 4th edition. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality.

Hageman, I. C., I. A. van Rooij, I. de Blaauw, M. Trajanovska, and S. K. King. 2023. A systematic overview of rare disease patient registries: Challenges in design, quality management, and maintenance. Orphanet Journal of Rare Diseases 18(1):106.

Hazari, A., and P. Walton. 2015. The UK National Flap Registry (UKNFR): A national database for all pedicled and free flaps in the UK. Journal of Plastic, Reconstructive & Aesthetic Surgery 68(12):1633–1636.

Hernandez, J. A., J. M. Miller, E. Emovon, 3rd, J. N. Howell, G. Testa, A. K. Israni, J. J. Snyder, and L. C. Cendales. 2024. OPTN/SRTR 2022 annual data report: Vascularized composite allograft. American Journal of Transplantation 24(2s1):S534–S556.

Inau, E. T., J. Sack, D. Waltemath, and A. A. Zeleke. 2021. Initiatives, concepts, and implementation practices of FAIR (findable, accessible, interoperable, and reusable) data principles in health data stewardship practice: Protocol for a scoping review. JMIR Research Protocols 10(2):e22505.

Inau, E. T., J. Sack, D. Waltemath, and A. A. Zeleke. 2023. Initiatives, concepts, and implementation practices of the findable, accessible, interoperable, and reusable data principles in health data stewardship: Scoping review. Journal of Medical Internet Research 25:e45013.

IRHCTT (International Registry on Hand Composite Tissue Transplantation). n.d. What is the IRHCTT?. https://www.handregistry.com/irhctt.php (accessed October 7, 2024).

Ismail, L., H. Materwala, A. P. Karduck, and A. Adem. 2020. Requirements of health data management systems for biomedical care and research: Scoping review. Journal of Medical Internet Research 22(7):e17508.

Knapp, E. A., A. K. Fink, C. H. Goss, A. Sewall, J. Ostrenga, C. Dowd, A. Elbert, K. M. Petren, and B. C. Marshall. 2016. The Cystic Fibrosis Foundation patient registry. Design and methods of a national observational disease registry. Annals of the American Thoracic Society 13(7):1173–1179.

Labkoff, S. E., Y. Quintana, and L. Rozenblit. 2024. Identifying the capabilities for creating next-generation registries: A guide for data leaders and a case for “registry science.” Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association 31(4):1001–1008.

Larsson, S., P. Lawyer, G. Garellick, B. Lindahl, and M. Lundström. 2012. Use of 13 disease registries in 5 countries demonstrates the potential to use outcome data to improve health care’s value. Health Affairs 31(1):220–227.

Mandavia, R., A. Knight, J. Phillips, E. Mossialos, P. Littlejohns, and A. Schilder. 2017. What are the essential features of a successful surgical registry? A systematic review. BMJ Open 7(9):e017373.

McCormack, P., A. Kole, S. Gainotti, D. Mascalzoni, C. Molster, H. Lochmüller, and S. Woods. 2016. “You should at least ask.” The expectations, hopes and fears of rare disease patients on large-scale data and biomaterial sharing for genomics research. European Journal of Human Genetics 24(10):1403–1408.

NCATS (National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences). n.d. Registry sustainability. https://toolkit.ncats.nih.gov/glossary/registry-sustainability/ (accessed October 25 2024).

Petruzzo, P., C. Sardu, M. Lanzetta, and J. Dubernard. 2017. Report (2017) of the International Registry on Hand and Composite Tissue Allotransplantation (IRHCTT). Current Transplantation Reports 4:294–303.

RaDaR (Rare Diseases Registry Program). n.d.-a. Create your registry plan. https://registries.ncats.nih.gov/module/setting-up-your-registry/create-your-registry-plan/plan-for-roadblocks/ (accessed September 12, 2024).

RaDaR. n.d.-b. Review & clean your data. https://registries.ncats.nih.gov/module/maintaining-your-registry/clean-up-your-data/review-data-protection-plan/ (accessed September 12, 2024).

RaDaR. n.d.-c. Review & evolve your registry. https://registries.ncats.nih.gov/module/setting-up-your-registry/create-your-registry-plan/plan-for-roadblocks/ (accessed September 12, 2024).

RaDaR. n.d.-d. Tool: Participant criteria checklist. https://registries.ncats.nih.gov/wp-content/uploads/2019/02/Tool_Participant_Criteria_Checklist.pdf (accessed October 24, 2024).

Solomon, D., N. A. Shadick, and E. Patorno. 2019. Determining the best methods for using patient registry data in clinical research. Washington, DC: Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute.

SRTR (Scientific Registry of Transplant Recipients). n.d. Driven to make a difference: Mission, vision, and values. https://www.srtr.org/about-srtr/mission-vision-and-values (accessed October 7, 2024).

Tabatabaei Hosseini, S. A., R. Kazemzadeh, B. J. Foster, E. Arpali, and C. Süsal. 2024. New tools for data harmonization and their potential applications in organ transplantation. Transplantation 108(12):2306–2317.

Tran, L., H. Kandel, D. Sari, C. H. Chiu, and S. L. Watson. 2024. Artificial intelligence and ophthalmic clinical registries. American Journal of Ophthalmology 268:263–274.

UNOS (United Network for Organ Sharing). n.d. Technology for transplants. https://unos.org/technology/technology-for-transplantation (accessed October 24, 2024).

Wilkinson, M. D., M. Dumontier, I. J. Aalbersberg, G. Appleton, M. Axton, A. Baak, N. Blomberg, J.-W. Boiten, L. B. da Silva Santos, P. E. Bourne, J. Bouwman, A. J. Brookes, T. Clark, M. Crosas, I. Dillo, O. Dumon, S. Edmunds, C. T. Evelo, R. Finkers, A. Gonzalez-Beltran, A. J. G. Gray, P. Groth, C. Goble, J. S. Grethe, J. Heringa, P. A. C. ’t Hoen, R. Hooft, T. Kuhn, R. Kok, J. Kok, S. J. Lusher, M. E. Martone, A. Mons, A. L. Packer, B. Persson, P. Rocca-Serra, M. Roos, R. van Schaik, S.-A. Sansone, E. Schultes, T. Sengstag, T. Slater, G. Strawn, M. A. Swertz, M. Thompson, J. van der Lei, E. van Mulligen, J. Velterop, A. Waagmeester, P. Wittenburg, K. Wolstencroft, J. Zhao, and B. Mons. 2016. The FAIR guiding principles for scientific data management and stewardship. Scientific Data 3(1):160018.

This page intentionally left blank.