Advancing Face and Hand Transplantation: Principles and Framework for Developing Standardized Protocols (2025)

Chapter: 6 The Transplant Experience: Outcomes

6

The Transplant Experience: Outcomes

“It was so much more comfortable to not have to be on pain medicine. … [W]hen I got my face transplant it just opened up my world.”

— Face transplant recipient, presented testimony to the committee at the March 22, 2024, public webinar

“It’s hard to overstate how good it is just to be able to do simple things without needing assistance, such as putting on my glasses, or scratching the back of my head. … I frequently figure out new uses for the tools [hands] I’ve been given, which never fails to feel like a blessing.”

— Bilateral hand transplant recipient, written testimony to the committee

“Two to three days after surgery I was able to eat. … [S]ome abilities came back really quickly.”

— Face transplant recipient, presented testimony to the committee at the June 6, 2024, public webinar

“When I gave birth to my daughter 2 years ago, I couldn’t have fulfilled these dreams of becoming a mother without my new hands. It’s absolutely amazing to hold her hands every day and hold her in my arms. There is no word to describe this feeling, and I’m so grateful for having this change.”

— Bilateral hand transplant recipient, presented testimony to the committee at the March 22, 2024, public webinar

This final chapter in Part II provides discussion of face and hand transplant outcomes. Outcome metrics seek to quantify the impact of an intervention or treatment on health, including both risks (e.g., side effects) and benefits (e.g., effectiveness) (Williamson et al., 2017). Given the historical understanding of these transplants as life-enhancing rather than lifesaving, face and hand transplantation must demonstrate the ability to improve the lived experience of transplant recipients. Within this chapter, the committee does not recommend any specific measure or assessment tool, but rather provides a summary of outcomes assessed and outcome metrics used historically, in addition to other relevant information. This chapter builds upon the data in Chapter 2, which includes reported outcomes following face or hand transplant, such as survival rate, time to failure (removal of transplant), and functional outcomes.

This chapter begins with an overview of health outcomes, followed by a discussion of key outcomes for face and hand transplantation and then a review of the limitations and challenges associated with current outcome measures used in face and hand transplantation. Finally, future directions are discussed.

OVERVIEW OF HEALTH OUTCOMES

The World Health Organization (WHO) defines health as “a state of complete physical, mental, and social well-being and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity” (WHO, n.d.). WHO considers health to be a holistic state of well-being, including access to health care, support for education, and improved environmental conditions that affect health (WHO, 1998). The distinct domains of health and the full range of health (including wellbeing) beyond disease and infirmity in this definition have greatly influenced health outcome assessments. In research, an outcome is an endpoint that demonstrates the effects of an intervention or exposure on a population (Ferreira and Patino, 2017). In clinical care, an outcome is “a measurable change in symptoms, overall health, ability to function, quality of life, or survival outcomes that result from giving care to patients” (NCATS, n.d.a; italics added). Outcome domains are “concepts to be measured in terms of a further specification of an aspect of health” (Kaiser et al., 2020, p. 2). These impacts or improvements can be generic or specific to the condition/procedure to which they are referring to. Outcome metrics are used to convey and reflect the impact of a particular health service, procedure, or treatment and how it relates to patients. Outcomes metrics can be measured objectively (e.g., using clinical diagnostic data) or subjectively (e.g., using patient reports and perceptions). Patient-reported outcomes (PROs) are “any report of the status of a patient’s (or person’s) health condition,

health behavior, or experience with healthcare that comes directly from the patient, without interpretation of the patient’s response by a clinician or anyone else” (NQF, 2013, p. 5). PROs are usually collected on a fixed scale to quantify responses and key domains include health-related quality of life (HRQoL), symptoms and symptom burden experience with care, and health behaviors (NQF, 2013).

It is important to note that while listed as three separate focus areas in the study statement of task (see Chapter 1), patient reporting, quality-of-life measures, and outcomes metrics are reliant on each other. For example, there cannot be patient-reported or HRQoL outcomes without assessing a patient’s health status repeatedly over time. Additionally, meaningful interpretations of any observed changes are critical.

Outcome Metrics and Challenges with Small Populations

Outcome metrics can measure impacts at both the individual and population level. For individual patients, assessments can inform care, such as the need for additional interventions or changes to the care management plan. They can also be used to quantify the impact of the transplant on the patient, including their quality of life (QoL), clinical outcomes like functional status, satisfaction, and psychosocial heath (Hautz et al., 2020). Population-level outcome metrics can be used to aggregate different classes of data across a population to address specific questions, such as the effectiveness of certain interventions (Parrish, 2010). Outcome metrics commonly used to measure population health include mortality, life expectancy, summary measures, and measures of the distribution of health (Parrish, 2010). However, there are challenges with population-level outcome metrics in small populations. For example, the limited number of observations means that variability, outliers, or confounding factors have a greater impact on metrics when using statistical methods designed for larger datasets (NASEM, 2018). Some health outcomes, such as survival rate, can be calculated, and have been reported for both face or hand transplant,1 but results may be more volatile due to small numbers and will thus necessitate using risk-adjusted analyses, including incorporating qualitative data to complement the quantitative data. Evaluation of treatments in small populations is possible, provided that critical aspects of clinical research in small populations, such as the identification of outcome metrics that determine success, establishment of a baseline for measurement of change, and a means of follow-up to assess

___________________

1 See Homsy et al. (2024), Shores et al. (2015), and Chapter 2 for more information on survival rates.

change, are integrated into the analysis (IOM, 2001b). Pooling of data from available sources (e.g., for vascular composite allotransplantation [VCA], from multiple transplant centers through the Clinical Organization Network for Standardization of Reconstructive Transplantation [CONSORT]) can increase the power of analyses. (For more information on conducting clinical research in small populations, see the section below on Addressing Small Sample Size Challenges and Chapter 7).

Quality of Life and Health-Related Quality of Life

The WHO defines QoL as “an individual’s perception of their position in life in the context of the culture and value systems in which they live and in relation to their goals, expectations, standards, and concerns. It is a broad ranging concept affected in a complex way by the person’s physical health, psychological state, personal beliefs, social relationships and their relationship to salient features of their environment” (WHO, 1998, p. 11). During the 1980s, terminology shifted from health to health-related QoL (HRQoL) measures. To distinguish an individual’s health from broader QoL concepts such as housing or standard of living (Campbell et al., 1976), limitations in functioning (what people are able to do) were attributed specifically to health in general or to a specific domain of health or health condition. There is no universal definition of HRQoL, but it is accepted as a multidimensional concept used to examine the effect of health status on QoL by describing various aspects of functioning and well-being, including objective and subjective perspectives (de Wit and Haios, 2013). Standards for gathering patient-reported HRQoL outcomes have been created by multiple entities, including the American Psychological Association, the American Educational Research Association, the National Council on Measurement in Education, and the Consensus-Based Standards for Selection of Health Measures Initiative.2

One of the main motivations for measuring HRQoL—or, more specifically, change in HRQoL—is to evaluate the effectiveness of an intervention, such as a face or hand transplant. Generic HRQoL measures consider domains that involve basic human values such as functioning (what one is able to do) and feelings (ill- and well-being) and are applicable to general and patient populations (Patrick and Deyo, 1989). Disease- and condition-specific HRQoL measures focus on QoL limitations attributable to a certain disease or condition (Ware et al., 2016).

___________________

2 Presented by David Tulsky, University of Delaware, at the April 17, 2024, information-gathering webinar. See https://www.nationalacademies.org/event/42240_04-2024_principles-and-framework-to-guide-the-development-of-protocols-and-standard-operating-procedures-for-face-and-hand-transplants-webinar-2.

Evaluating HRQoLs: Psychometric and Utility Measures

Though both psychometric and utility measures3 are used to evaluate HRQoL, these measures differ in their purposes and how they score and interpret health. Psychometric measures are designed to assess the subjective experience of health and well-being, while utility measures are designed to quantify the value or relative importance that individuals place on different health states and outcomes. Psychometric measures attempt to validly estimate profiles of health and summary health status measures through psychometric scaling across multiple domains, while utility measures assess health in terms of a single index through preference estimates (Revicki and Kaplan, 1993). Psychometric tools use psychometric methods of scale construction and scoring. In contrast, utility methods yield a single (0–1, death–perfect health) index score (Touré et al., 2021). The two types of measures are complementary. While psychometric measures help clarify an individual’s health profile, utility measures focus on the preference and values of different health states, which can inform global decision making and cost-effective analyses.

Figure 6-1 summarizes the major HRQoL domains represented in psychometric and utility index tools used historically, with the addition of psychometric tools from the Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS)4 and three utility measures. Note that the tools included in the figure are examples and not an exhaustive list of HRQoL measurement tools.5 Measurement of the full range for each essential domain is important because scores both above and below general population normal scores have been observed for some domains in transplant studies. Historically, health has most frequently been defined by the following generic QoL domains (roughly in the order of their representation across tools): physical functioning, role functioning, psychological distress,

___________________

3 For the purposes of CONSORT, psychometric measures are likely more relevant at this point in time. However, utility measures are an important aspect of HRQoL measurement. Recent arguments in favor of utility index scoring and methods were published from the PROMIS investigators who have applied utility scoring to the PROMIS items in Figure 6-1 to improve them over legacy estimates used in utility-based cost–benefit analyses of specific treatments and health care. For more information, see Hartman and Craig (2018). Additionally, utility measures have been used previously in hand transplantation for decision making and cost-effectiveness analyses. See Chung et al. (2010) and Efanov et al. (2022) for more information.

4 PROMIS includes a series of fixed-length profile instruments that use subsets of items from the PROMIS item banks to capture various aspects of a patient’s HRQoL. PROMIS-27 is a short-form profile containing 27 items and seven domains, while PROMIS-57 is a long-form profile that contains 57 items and the same seven domains. See section on PROMIS for more information.

5 For more information on these and other tools, see https://eprovide.mapi-trust.org/ (accessed January 8, 2025).

social functioning, general health, pain, and fatigue.6 Below the red box in Figure 6-1 are proven measures of the opposite poles of psychological distress and fatigue domains, namely, psychological well-being and energy, respectively. These domains have frequently been combined psychometrically to estimate summary scores over a wide range of the physical and mental components of health, using long- and short-form surveys. More recently, newer measurement systems (e.g., PROMIS) have expanded upon these larger concepts and domains to include specific sub-domains. Brevity is an important consideration in scale selection as shorter scales (e.g., SF-12 rather than SF-36) can enable study-specific measurement additions while reducing respondent burden.

Common Data Elements

Recent advances to standardize the definitions, collection, and use of outcomes data in health care include the use of common data elements (CDEs). CDEs are standardized, structured, well-defined data points used to ensure consistency in data collection, interpretation, and analysis across medical populations. CDEs are “defined fields describing the data to be collected (e.g., identifying specific variables) along with how to gather the data (e.g., PROs), and how the response is represented in a dataset (e.g., allowable responses or variable coding)” (NIH, 2024). The National Institutes of Health (NIH) has developed and endorsed collections of CDEs to improve comparisons and analyses of data across studies (NIH, 2024). For example, the NIH-developed NIH Toolbox7 provides CDEs for evaluating neurological and behavioral functioning, with domains that include cognition, motor function, sensory function, and emotional health.

NIH also invested in additional fundamental psychometric item bank and scale development to improve the quality of PROs through the PROMIS Initiative (Cella et al., 2010). PROMIS is a standardized system of CDEs used to measure PROs across various health conditions with the goal to evaluate the effectiveness of treatments from the patient’s perspective. PROMIS “includes over 300 measures of physical, mental, and social health for use with the general population and with individuals living with chronic conditions” (Health Measures, 2024a), subsets of which can be summed to create a single global score. PROMIS surveys can be administered through in-person interviews, telephone/remote interviews,

___________________

6 Because the Sickness Impact Profile measured health only dichotomously in terms of behavioral functioning, it did not represent the generic domain or feelings of ill-being, such as pain or fatigue domains.

7 See https://www.healthmeasures.net/explore-measurement-systems/nih-toolbox (accessed January 6, 2024).

NOTES: Psychometric: COOP = Dartmouth Function Charts (1987); DHP = Duke Health Profile (1990); HIE = Health Insurance Experiment (1990); MOS – 149 = MOS Functioning and Well-Being Profile (1992); MOS SF-12/36 = 12/36 Item Short Form Health Survey (1992); NHP = Nottingham Health Profile (1980); PROMIS = Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System, 29-57 items (2005 on); QU = Quality of Life Index (1961); SIP = Sickness Impact Profile (1976). Utility: EQ-5D = European Quality of Life Index (1990); HUI = Health Utility Index (1996); SF-6D = SF-36 Utility Index (2002, 2020).

SOURCES: Adapted from Ware, 1995. Measure sources: Bergner et al., 1981; Brazier et al., 1992; Brook et al., 1983; Cella et al., 2010, 2019; EuroQol Group, 1990; Hunt et al., 1981; Parkerson et al., 1981; Spitzer et al., 1981; Stewart and Ware, 1992; Torrance et al., 1996; Ware and Sherbourne, 1992; Ware et al., 1996b.

or self-administered reports, and are designed to be universally applicable across different populations, allowing for comparisons among groups or studies (Bjorner et al., 2014a,b; Kisala et al., 2019; Wang et al., 2017). Each PROMIS measure has a definition, a set number of scales, banks, or pool, and some have short forms, which have been designed to reduce testing time and participant burden (Health Measures, 2024b). Additionally, computerized adaptive testing, a core feature of PROMIS, dynamically tailors the questionnaire to the patient, selecting questions based on previous responses to maximize the accuracy of the assessment while minimizing the number of questions asked and time to complete the questions (Health Measures, 2024a). It is not expected that all domains are surveyed for each population or condition; rather, a subset of measures can be selected based on the areas that are most relevant to the research population to capture the most relevant domains.8

OUTCOMES FOLLOWING FACE AND HAND TRANSPLANTATION

Face and hand transplants are complex procedures requiring long-term care management, which affects multiple facets of a recipient’s lived experience. Consequently, there are many measurable outcomes that may be affected by the transplant experience. However, the lack of longitudinal outcomes reporting, limited sample size, and heterogeneity of information has made a true understanding of face and hand VCA outcomes data challenging. Commonly assessed outcomes are listed in Table 6-1 under the overarching categories of surgical, medical, functional, QoL, psychosocial, and aesthetic outcomes.9 In the existing literature, reports of hand transplant outcomes have primarily focused on the physiological survival of the allotransplant, functioning, and immunological outcomes (e.g., rejection, side

___________________

8 For more information, see https://commonfund.nih.gov/patient-reported-outcomes-measurement-information-system-promis (accessed January 7, 2025).

9 These categories were chosen for ease of organization and summarization of the breadth of outcomes, rather than exact domain definitions. The committee recognizes that there may be conceptual disagreements regarding these outcomes across domains. For example, the QoL literature subsumes psychosocial outcomes within the concept of QoL, which includes physical, mental/psychological, social, role functioning, and well-being as domains of HRQoL. See de Wit and Hajos (2013). In the psychological literature, QoL is sometimes considered a psychosocial domain. See Rosenberger et al. (2013). Other transplant studies have separated these domains into two categories. See Seiler et al. (2016). For the purposes of this chapter, the committee has separated these two domains out in Table 6-1 and the following sections primarily for organizational purposes. Further discussion of these conceptual disagreements is outside of the scope of this report. Additionally, there are subdomains that are likely particularly important for this population, but this level of detail is not attempted to be conveyed through this table.

TABLE 6-1 Commonly Assessed Outcomes Following Face and Hand Transplantation

| Categories | Key Outcomes |

|---|---|

| Surgical | Allograft survival |

| Control of pain levels | |

| Morbidity/mortality | |

| Incidence of transplant rejection/longevity of transplant | |

| Surgical revisions | |

| Medical | Control of rejection episodes (immunosuppression) |

| Control of adverse events and complications (side effects, organ failure, death) | |

| Overall health | |

| Pain and pain management | |

| Functional | Improvement in function range relative to pretransplant state Autonomy in activities of daily living (with or without assistive devices) |

| Hands: ability to hold, grasp, and do daily activities such as bathing, dressing, eating, and writing. Grip and pinch strength, gross and fine motor skills, and range of motion. | |

| Face: ability to talk, chew, swallow, blink, and smile by allowing improved control over the movement of the mouth, nose, eyelids, and other parts of the face. Facial expressions. Ability to breathe, smell, speak, and understand. | |

| Mobility | |

| Sensory recovery/sensitivity | |

| Hands: Feel hot or cold, feel pain, feel touch and texture. | |

| Face: Feel hot or cold, feel touch | |

| Quality of Life | Qualitative and quantitative measures of health-related quality of life (e.g., physical, mental/psychological, social, role functioning, and well-being) |

| Psychosocial | Mental health adjustment and psychological outcomes |

| Integration of allograft into recipient’s identity | |

| Effective coping when difficulties arise | |

| Reducing psychiatric symptoms | |

| Aesthetic | Satisfaction with aesthetic appearance |

SOURCES: Aycart et al., 2017; Bernardon et al., 2015; Diep et al., 2020; Dorante et al., 2020, 2023; Dubernard, 2011; Fischer et al., 2015; Hadjiandreou et al., 2024; Hautz et al., 2020; Kumnig et al., 2022; Longo et al., 2023; Nizzi et al., 2017; Reece and Ackah, 2019; Singh et al., 2015, 2016; Tchiloemba et al., 2021; Tintle et al., 2022; Tyner et al., 2023; Wells et al., 2022; and testimony from patients and caregivers presented at public webinars, in lived experience consultant discussions, and from the online call for perspectives.

effects) (Mendenhall et al., 2020; Shores et al., 2017; Tulsky et al., 2023). Similarly, reports of face transplant outcomes have primarily focused on the survival of the allotransplant and immunological outcomes, followed by medical, functional, aesthetic, QoL, and psychosocial outcomes (Aycart et al., 2017; Diep et al., 2021; Hadjiandreou et al., 2024; Hoffman et al., 2022; Homsy et al., 2024; Wells et al., 2022). Other commonly reported outcomes include overall morbidity/mortality, incidence of transplant rejection, longevity of transplant, secondary revisions, allograft function, improvement in function range relative to pretransplant state, aesthetic appearance, and patient satisfaction.

Surgical, Medical, and Functional Outcomes

In a systematic review of 48 face transplantations, the mortality rate was found to be 15.2 percent, with deaths caused by malignancy, infection, respiratory failure, non-adherence, and suicide (Hadjiandreou et al., 2024). Surgical revisions were fairly common, with a mean of 2.8 additional procedures post transplant and the need for revisions declining after 36 months (Hadjiandreou et al., 2024). In a systematic review of hand transplants from 1998 to 2019, the mortality rate was 5.2 percent, largely due to cardiac arrest, infection, and immediate perioperative death (Wells et al., 2022). A total of 10.8 percent of transplants were amputated, with the most common reason cited being acute rejection, followed by withdrawal from the immunosuppression regimen (Wells et al., 2022). (See Chapter 5 for more information about surgical and medical complications.)

Longitudinal measurement of functional outcomes remains a challenge across face and hand transplantation. Functional outcomes in face transplantation include, but are not limited to, ability to speak, nasal breathing, ability to smell, ability to eat, and facial expression. A systematic review of face transplant outcomes found that all patients experienced an improvement in their functional tasks (Hadjiandreou et al., 2024). While most observations were subjective, there is evidence of objective measures being reported that can form the basis for validated face transplant outcome measures (Hadjiandreou et al., 2024). Functional outcomes following hand transplant are commonly measured using comparisons between pre- and postoperative Disability of the Arm, Shoulder, and Hand (DASH) scores. DASH scores were found to have decreased post transplantation, with preoperative scores ranging from 25 to 100 and postoperative scores ranging from 7 to 86, wherein 0 indicates no disability and 100 is severe disability (Wells et al., 2022). The WHO has used the International Classification of Functioning, Disability, and Health model as a framework to assess health-related function in terms of body function (e.g., pain), activities (e.g., walking), and participation (e.g., going to school or work) (WHO, 2001). It has

been applied to physical, mental, and social functioning across populations and conditions.

Quality-of-Life Outcomes

In the published literature, HRQoL outcomes are underreported compared with medical, surgical, and functional outcomes. The lack of reporting is likely a result of multiple factors, such as poor follow-up by transplant teams or teams that are waiting for a longer follow-up time to provide a comprehensive assessment (Aycart et al., 2017). However, the importance of measuring HRQoL is paramount, as improvements in QoL are often a main reason that recipients have chosen to proceed with a transplant.10 A systematic review of outcomes following face transplant found that the QoL of recipients improved with gradual social integration into work, family, and community environment (Hadjiandreou et al., 2024); however, despite general improvement, variability was seen, as some patients had posttransplant complications and were affected by continuous monitoring burden and external factors, leading to worsening in QoL outcomes that were not captured by face transplant–specific questionnaires. Additionally, most of the evidence was reported in the form of anecdotal or subjective reports.

As discussed previously, HRQoL serves as a comprehensive measure that captures the multifaceted impact of face and hand transplantation on a patient’s life, making it essential for evaluating the success of the procedure beyond clinical and functional outcomes. Figure 6-2 adapts the Wilson and Cleary (1995) conceptual model linking biological and psychological aspects of health to HRQoL through a continuum of outcomes and measures for face and hand transplantation, ranging from the most objective bio/physiological and performance tests to patient-reported measures of symptoms and specific and generic HRQoL endpoints. PROs are self-reported outcomes that cannot be inferred from clinical measurements or performance tests, and encompass specific symptoms, transplant-specific HRQoL, and generic HRQoL. Of particular importance is whether, and how well, specific and generic HRQoL measures respond to lower and higher levels of objective biomarkers and to performance tests to their left in Figure 6-2. The measures are examples and not comprehensive.

Psychosocial and Aesthetic Outcomes

The main psychosocial and aesthetic outcomes discussed following face transplantation are improved social life (e.g., return to work, traveling, self-confidence), improved aesthetic results, and sense of self (e.g., body

___________________

10 Lived experience consultants’ testimony.

NOTES: On the left, example measures are more objective, more specific, and more clinically useful for a specific condition. On the far right, example measures are more generic or general and enable comparisons of burden of different conditions and benefits of different treatments. ADLs = activities of daily living; DASH = Disabilities of the Arm, Shoulder, and Hand; EQ-5D = EuroQol – 5 Dimension; HRQoL = health-related quality of life; SF-12 = 12-Item Short Form Survey; SF-36 = 36-Item Short Form Survey.

SOURCE: Adapted from Wilson and Cleary, 1995.

image, accepting the new face as one’s own) (Nizzi et al., 2017). Overall, there are demonstrated positive psychosocial outcomes leading to high levels of patient satisfaction in face transplantation (Nizzi et al., 2017). In hand transplantation, psychosocial outcomes post transplantation may be compared to outcomes during prosthesis use (Salminger et al., 2016). Transplantation patients score significantly higher in emotional and mental health domains than those who used protheses (Salminger et al., 2016).

Despite their importance, systematic reviews of psychosocial and aesthetic outcomes are lacking for both face and hand transplantation due to limited published primary literature and sparse data reporting. Moreover, it is common for published literature to include only minimal, general information about psychosocial outcomes (Nizzi et al., 2017). Additionally, analysis of psychosocial and aesthetic outcomes may sometimes fall under larger QoL discussions (Aycart et al., 2017).

Commonly Used Outcome Measures for Face and Hand Transplantations

Numerous assessment tools have been historically used following face and hand transplantation. These include generic HRQoL tools that measure physical, social, and role functioning well-being (e.g., SF-36, SF-12, RAND-36) (Bernardon et al., 2015; Bueno et al., 2014; Lantieri et al., 2016); utility HRQoL tools (e.g., EuroQoL-5D) (Balestroni and Bertolotti, 2012; Bueno et al., 2014); tools that measure sensation or pain (e.g., Visual Analog Scale, Semmes-Weinstein monofilament test) (Bueno et al., 2014; Siemionow and Gordon, 2010; Topçu et al., 2017); tools that are used for hand transplant recipients to measure physical and/or social functioning (e.g., Hand Transplantation Score System, Sollerman Hand Function Test, Disability of the Arm, Shoulder, and Hand, Carroll Upper Extremity Function Test, Tinel test, Kapandji test, 9 hole peg test) (Bueno et al., 2014; Hautz et al., 2020; Lanzetta et al., 2007; Singh et al., 2016); and tools that are used for face transplant recipients to measure physical or social functioning (e.g., Daniels and Worthingham Muscle Testing, Facial Disability Index, Grandfather Passage) (Dixon et al., 2011; Kollar et al., 2020; Levy-Lambert et al., 2020). Many activities of daily living (ADLs), such as the abilities to smell and eat, do not have designated assessment tools but rely on other types of measurement, such as patient reporting or checklists (e.g., the Katz Index of Independence in Activities of Daily Living, the Lawton Instrumental Activities of Daily Living Scale) (Bueno et al., 2014; Dixon et al., 2011; Edemekong et al., 2019). In addition to the measures listed above, psychosocial measures to assess depressive symptoms and anxiety have been used historically for

care management (see Chapter 5 for more information and Appendix D for more information on the Chauvet Workgroup).11

LIMITATIONS IN CURRENT OUTCOME MEASUREMENTS

“We’re really just scratching the surface of what we could do [with patient-reported outcome measures]; we have data to do the rest.”

— Dr. David Tulsky, University of Delaware, presented testimony to the committee at the April 17, 2024, public webinar

“You have to have crisp and robust definitions for every single variable that you collect across the board, across institutions. Otherwise, it’s really comparing apples to oranges.”

— Dr. Ryutaro Hirose, Scientific Registry of Transplant Recipients, presented testimony to the committee at the May 29, 2024, public webinar

“Assessment of function is critical for advancement. There is a gap between clinical and lab-based assessments of hand function and use of the transplanted hand in real life.”

— Dr. Scott Frey, University of Missouri, written testimony to the committee

“Outcome metrics should be geared to each patient, as they can vary widely depending on level of amputation or facial deformity.”

— Bilateral hand transplant recipient, written testimony to the committee

A true understanding of patient outcomes following face and hand transplantation requires a comprehensive approach to representing outcome dimensions. But due to several existing limitations there is a relative paucity of long-term outcomes data on face and hand VCA compared with, say, solid organ transplantation. Additionally, there has been little agreement on the establishment of core outcome domains and common measurement instruments for face and hand transplantation (Fullerton et al., 2022; Shores et al., 2017), though there have been discussions about the need for balancing objective functional outcomes (like grip strength or range of motion) with PROs. Aycart et al. (2017) identified more than 25 different instruments that have been used to evaluate HRQoL after face transplantation. Moreover, researchers differ on their definitions for

___________________

11 The Chauvet Workgroup is a multicenter, global collaboration project formed to discuss the specific psychosocial outcomes as a result of VCAs (Kumnig et al., 2022). See Appendix D for more information.

commonly used outcomes (Williamson et al., 2017). An additional challenge is that the heterogeneity of the patient population (e.g., different levels of injury, facial defect, or amputation) affects the comparison of outcomes. Clinically, patients have different goals and expectations in pursuing a transplant. The extremely small sample available has also limited the ability to develop and validate VCA-specific measures. These challenges—small sample size, heterogeneity of the patient population, lack of consensus, lack of longitudinal data to base decisions upon, and differing priorities across transplant centers—have resulted in a wide diversity of outcome measures used to assess the impact of VCA for each recipient.

There have also been calls for better incorporation of patient-reported outcomes measures (PROMs), to identify essential domains for VCA patients and caregivers and to help in the development of new, VCA-specific measures (Greenfield et al., 2020; Kimberly et al., 2019; Tulsky et al., 2023; Tyner et al., 2023). The committee heard from transplant recipients that the available instruments to assess QoL are not adequate to pick up the range of special issues they face. Traditional clinical measures of success do not always align with what patients’ value most. As noted by Tysome et al. (2015, p. 512):

Outcome measures are often clinician-[centered], measuring aspects that are deemed important primarily to healthcare professionals. However, it is our patients’ well-being and the impact of our interventions on their lives that are most important in our practice.

The Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act of 198912 mandated broad-based, patient-centered outcomes research beyond traditional measures of survival and also called for specific clinical endpoints to include physical and mental measures of functional status and well-being and patient satisfaction (IOM, 1990). Accordingly, health status and patient satisfaction (with care services) monitoring became a focus of law and public policy. Along with patient satisfaction with care and services, typical PROs in health care include HRQoL, symptoms and symptom burden, experience with care, functional status, and health (Churruca et al., 2021; NCATS, n.d.-b; NQF, 2013). PROMs can assess many important outcomes of face and hand transplant. However, most outcomes reported in the face transplant literature do not include PROs (Hoffman et al., 2022).

Despite the availability of validated measurement tools, clinicians often fail to use these measures in clinical practice. This stems from a disconnect between research and clinical care. For research purposes, using broad, generic measures that are applicable to many illnesses generates results for

___________________

12 P.L. 101–239.

larger patient populations, and the resulting data often have stronger statistical properties. However, in clinical settings the utility of a measure lies in its ability to reliably capture relevant predictors of improved outcomes, assess the status of patients accurately, and guide clinical interventions. The existing tools used in VCA have primarily fallen into the former category, largely due to the challenges associated with small sample sizes and insufficient coordination between centers for validating VCA-specific and psychometrically sound measures. Generic measures have the advantage of providing a common yardstick that is useful both in making comparisons of disease/condition burden across diseases and in comparative effectiveness research for comparing benefits across treatments (Patrick and Deyo, 1989). Disease- and condition-specific HRQoL measures have the advantage in clinical practice and research of greater specificity and responsiveness to the presence of disease and to the clinically defined severity of a specific condition (Patrick and Deyo, 1989). The combination of generic measures and disease- and condition-specific measures have been shown empirically to complement each other in both research and practice (Ware et al., 2016; Ware et al., 2019). Thus, it is not a question of whether only generic or specific tools should be used, but rather that they are best used in tandem, given their complementary natures.

PROMs gather data directly from patients, families, and caregivers about health status and outcomes, and these evaluations are among the best predictors of future clinical, economic, and social status (Billig et al., 2020; Kim et al., 2017; Schilling et al., 2016; Zannad et al., 2023). The feasibility and usefulness of repeated self-administered surveys for purposes of estimating and comparing PROMs has been demonstrated in large, longitudinal medical care outcome studies (e.g., randomized control trials and quasi-experiments) (Temple et al., 2009; Testa and Simonson, 1996; Ware et al., 1996a).

There may be substantial variability among recipients regarding the aspects of their experience that most greatly affect their QoL. As each patient comes to the transplant with different goals, values, and priorities, revisiting individual patient goals that are identified before transplant and assessing them following transplant could ensure that outcome metrics reflect patients’ priorities. This approach would help in aligning clinical success with patient satisfaction, ensuring a more holistic view of the transplant’s impacts on their lives.

FUTURE DIRECTIONS

To appropriately characterize and compare VCA outcomes across patients and transplant centers, there needs to be an agreement on the key outcome domains to be measured. The agreed-upon outcome domains

should balance objective measures (e.g., performance-based functional status, recovery, motor function, and sensation) and subjective measures (e.g., patient-reported functioning and well-being in everyday life and satisfaction with transplant). In accordance with this report’s emphasis on patient- and family-centered care, the selection of key outcome domains should consider patients’ priorities for their care and outcomes.

Developing a Core Outcome Set

When investigating the impact of an intervention on an individual’s health, researchers and clinicians have a multitude of outcomes they could consider measuring. A core outcome set identifies what specific outcomes researchers and clinicians should measure and report when assessing an intervention (Clarke and Williamson, 2016). Over the last few decades, hundreds of core outcome sets have been developed for specific health conditions or specific populations in research and clinical settings (Gargon et al., 2021; Kirkham et al., 2017).

Methodologically, core outcome set developers first need to determine what to measure (known as the scope) (Kirkham et al., 2017; Williamson et al., 2017). This includes specifying the health condition, the target population, specific interventions, and specific settings. Next, the developers need to review the current evidence base to identify all potential core outcomes, as well as to determine which outcomes are most important to measure (Williamson et al., 2017), with input from key partners including patients, caregivers, researchers, and clinicians. Once the potential outcomes have been identified, similarly defined outcomes are grouped into a single outcome name, with agreed-upon, unambiguous definitions of the outcome. Then these outcomes are grouped into domains, or “constructs which can be used to classify broad aspects of the effects of interventions” (Williamson et al., 2017, p. 11).

Core Quality Measures Collaborative

The Core Quality Measures Collaborative (CQMC) outlined principles for selecting core measure sets (CQMC, 2021). The CQMC stressed that the set must be comprehensive, holistic, and meets the full definition of high-quality care as defined by the Institute of Medicine—care that is “safe, effective, person-centered, timely, efficient, and equitable” (IOM, 2001a, p. 6). The CQMC emphasizes that measures should produce meaningful and actionable information for patients, consumers, and clinicians. A core set should strike a balance between specialty-specific measures and those measures that are applicable across specialties and settings. Additionally, the set should be concise and efficient to minimize burden and include a

variety of measurement types. The CQMC advocates for the incorporation of patient-reported measures and standardized digital measures and encourages the development of novel measures (CQMC, 2021). As noted by Barker et al. (2015), “a recommended core outcome set would not preclude researchers from including other measures relevant to an individual study but would at least provide a central data set” (p. 571).

Developing New Patient-Reported Outcome Measures

“Every year since my surgery, my hands get evaluated on passive and active ranges of motion, my ability to pick up objects, and so on. But these tests fail to measure how I actually use my hands in my day-today life, and generic quality-of-life surveys also seem to miss the mark.”

— Bilateral hand transplant recipient, presented testimony to the committee at the March 22, 2024, public webinar

“Patient reporting must include our subjective experience.”

— Bilateral hand transplant recipient, written testimony to the committee

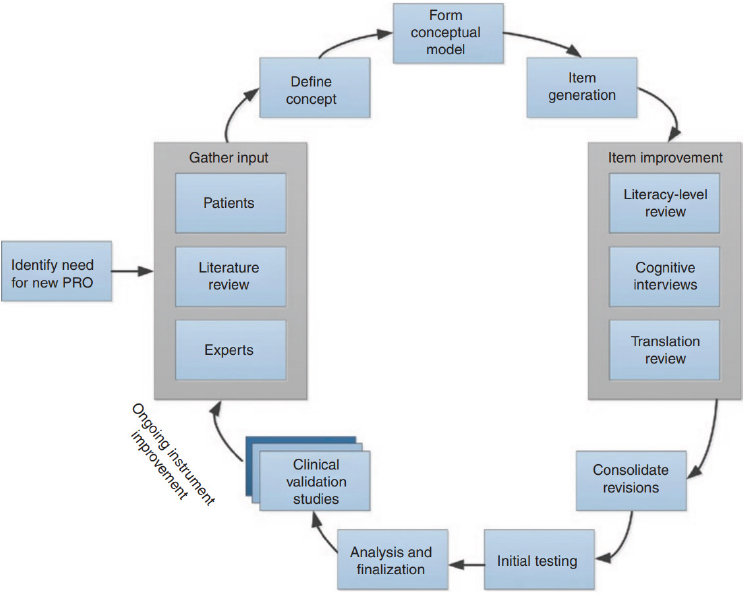

Some have argued that a VCA-specific measure would be beneficial (Fullerton et al., 2022; Tyner et al., 2023). Face and hand transplant recipients have expressed frustration that the current measures do not accurately assess their unique experiences with a unique procedure.13 It is crucial that patients have a say in the metric development; this may be accomplished through focus groups or interviews (Rothrock et al., 2011). When working to develop a new outcome measure, organizations such as the National Committee for Quality Assurance, the NIH Common Fund, and the National Quality Forum may be able to provide guidance and resources. Additionally, there are well-established processes for constructing PROMs from conceptual model development through instrument validation (see Figure 6-3; Rothrock et al., 2011).

Some work is already being done in this area for hand transplants, using the model depicted in Figure 6-3. As part of a larger Reconstructive Transplant Research Program grant to “lay the groundwork for developing validated VCA outcome measures by identifying the QOL domains that

___________________

13 Lived experience consultant testimony.

NOTE: PRO = patient-reported outcome.

SOURCE: Rothrock et al., 2011; © 2011 American Society for Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics.

are most relevant to hand transplantation candidates and recipients,”14 recently published results identified 28 specific domains important to hand transplant recipients, with 8 being unique to transplantation and 20 applicable to those with other medical conditions (Tulsky et al., 2023; Tyner et al., 2023). The themes identified as important to HRQoL after hand transplant spanned the areas of emotional, physical, and social health. The eight unique domains that were particularly important for hand transplant recipients based on this qualitative work were expectations, fitting in, integration/assimilation of the transplant, caregiver/familial support, sensation, satisfaction with the hand, posttransplant challenges, and treatment adherence (Tulsky et al., 2023; Tyner et al., 2023). This work was discussed in

___________________

14 See https://cdmrp.health.mil/search.aspx, Award Numbers: W81XWH-18-2-0068/W81XWH-18-2-0066/W81XWH-18-2-0067, W81XWH-20-2-0061/W81XWH-20-2-0062, and W81XWH-17-1-0335 (accessed January 6, 2025).

detail at the April 17, 2024, public webinar15 and it was noted that new items have been developed to measure these unique domains, using the model depicted in Figure 6-3.16 Additional information about this work is anticipated to be forthcoming following the release of this report, including continued evaluation of the construct validity of the new items and existing measures, examining group differences with proxy populations,17 and evaluating whether these measures have clinical utility. While this work is ongoing and the committee was not able to review the unpublished data, it is expected that once released, this research will be relevant and informative for additional outcome measure development and validation for both face and hand transplant.

Repurposing Other Patient-Reported Outcome Measures

Some established PROMs could also be repurposed for this population, such as the Patient Generated Index (PGI). The PGI is an individualized PROM in which respondents nominate domains that are important to them, rate how they function in these areas, and assign points according to how they would most like to see an improvement (Ruta et al., 1994). The PGI has been used in various settings, including kidney transplantation, to provide unique information across health conditions not captured by standardized measures (e.g., the importance of specific motor impairments, perception of self/body) and measure change from baseline (Janaudis-Ferreira et al., 2018; Mayo et al., 2017). The PGI has also been used to assess HRQoL in other disciplines including multiple sclerosis, stroke, cancer, and Parkinson’s

___________________

15 See https://www.nationalacademies.org/event/42240_04-2024_principles-and-framework-to-guide-the-development-of-protocols-and-standard-operating-procedures-for-face-and-hand-transplants-webinar-2 (accessed January 6, 2025).

16 The experimental items specific for hand transplant were discussed at the public webinar. The item pool and content coverage, respectively were (1) expectations and perceived outcomes, assessment of how well the recipients’ pre-surgical expectations were met; (2) fitting in, comfort in social interactions where other people may view or touch the transplant(s); (3) integration and assimilation of the transplant, acceptance and identification of the transplant as one’s own and feelings of “wholeness” or having something restored; (4) postsurgical challenges and complications, burdens of posttransplant treatment and therapies and effects on health and personal life; (5) hand sensation, ability to perceive sensations with the transplant; (6) satisfaction with hand aesthetics, satisfaction with physical appearance of the transplant; and (7) satisfaction with hand function, comfort, confidence, and satisfaction with the functional abilities of the transplant(s) in various daily activities. See https://www.nationalacademies.org/event/42240_04-2024_principles-and-framework-to-guide-the-development-of-protocols-and-standard-operating-procedures-for-face-and-hand-transplants-webinar-2 (accessed January 6, 2025).

17 A proxy population refers to a population that is not the exact population of interest but shares similar characteristics or experiences and is often used in research if there are challenges with response rates from target populations or limited sample sizes that impact validation of measures (Lu and Franklin, 2018). See section on proxy populations for more information.

disease, and with HIV positive patients (Kuspinar et al., 2020; Mayo et al., 2017). The PGI also has applications in rare conditions with smaller populations, such as high-grade gliomas (Pakzad-Shahabi et al., 2021).

As discussed previously, the PROMIS scales could also be used or adapted for this population. Additionally, LIMB-Q is a PROM used to measure outcomes in patients after lower extremity trauma (Q-Portfolio, 2025) and includes items that may be relevant for hand transplant recipients and may have the potential to be adapted for this population. LIMB-Q covers four domains—limb, HRQoL, experience of care, and treatment—with each domain consisting of multiple independently functioning scales, “providing flexibility to choose the subset of scales best suited to measure the outcomes of interest in any given study or clinical situation” (Q-Portfolio, 2025).

Addressing Small Sample Size Challenges

Though the numbers of patients receiving face and hand transplants may increase, they will always be a relatively small population. This small population size affects the validation of new measures and evaluation of outcomes.

Proxy Populations

As mentioned during the April 17, 2024 public webinar,18 sufficiently large and comprehensive datasets representing measured variables exist for traumatized patients before transplantation. This proxy population could be used for potentially valuable exploratory analyses including for generic HRQoL, pre-treatment score comparisons in relation to national norms, and cross-sectional estimates of correlations among the core clinical and HRQoL variables (see Figure 6-1) without incurring new data collection costs. A proxy population refers to a population that is not the exact population of interest but shares similar characteristics or experiences and is often used in research if there are challenges with response rates from target populations or limited sample sizes that impact validation of measures (Lu and Franklin, 2018). Proxy populations can be identified using five steps: “(1) elaborating and ranking attributes in the target population critical to mimic in the proxy population; (2) determining if the attributes occur naturally or can be learned; (3) identifying different proxy populations that may be appropriate; (4) comparing the attributes to assure that persons within the selected proxy population have attributes most similar to

___________________

18 See https://www.nationalacademies.org/event/42240_04-2024_principles-and-framework-to-guide-the-development-of-protocols-and-standard-operating-procedures-for-face-and-hand-transplants-webinar-2 (accessed January 6, 2025).

the target population, and/or embedding training strategies in the research design to increase the degree to which the proxy population mimics the target population; and (5) accurately assessing/reporting the threats to validity” (Lu and Franklin, 2018, pp. 1535–1536).

Due to the small population of face and hand transplantation patients, proxy populations may help to overcome small sample size challenges and help to validate new measures or a measurement battery. For hand transplantation, HRQoL data collected on individuals who have had major extremity trauma and/or amputation, including those that use prostheses or undergo complex reconstructive surgeries, would likely be helpful in validating measures for hand transplant recipients. Leveraged data from the Major Extremity Trauma Research Consortium19 or the Limb Loss and Preservation Registry,20 among others, may be a good fit as a proxy population for hand transplant recipients. For face transplantation, HRQoL data collected on individuals with severe facial trauma or facial burns may be an appropriate proxy population. Repurposed data from the Burn Model Systems Centers Program21 may be suitable.

Integration of Qualitative and Quantitative Methods

Appropriate qualitative methods allow the extraction of valuable data in the context of small populations. Current patient self-reported outcomes measures use a multimethod approach that integrates rigorous qualitative methods with quantitative psychometrics. The perspective of the participant receiving care becomes the starting point for measurement development rather than that of the medical providers and health care researchers. This approach illuminates how phenomena are viewed and experienced from the participant’s or patient’s viewpoint (Parsons et al., 2011; Tripp-Reimer, 1984) and has been successfully applied in studies on posttraumatic stress disorder in emergency settings (Rasmussen et al., 2014), QoL in patients with locked-in syndrome (Nizzi et al., 2012), and adherence to diabetes treatment (McCullough and Hardin, 2013), which have shown that the views of patients and providers are often misaligned. Applications of this approach have highlighted the importance of culturally appropriate health measures and called for paradigmatic shifts in patient care (Levesque, 2015; Santos-Lozada and Martinez, 2018). This theoretical lens points to

___________________

19 The Major Extremity Trauma Research Consortium METRC works to improve the “clinical, functional, and quality of life outcomes of both service members and civilians who sustain high energy trauma to the extremities” (METRC, n.d.).

20 See https://www.llpr.org/ (accessed January 6, 2025).

21 The Burn Model Systems Centers Program is funded by the National Institute on Disability, Independent Living, and Rehabilitation Center and works to “improve care and outcomes for individuals with burn injuries” (MSKTC, n.d.)

the importance of understanding the culturally constituted frames of meanings, through which “clinical realities” are constructed. Current provision of health care now requires patients and their caregivers to take charge of, for example, medication regimens and making changes to health behaviors. This necessitates acknowledging and incorporating the perspectives of patients and caregivers.

To develop PROMs that have content and face validity,22 qualitative methodologies can be used to capture data through the iterative application of various qualitative data collection methods. For example, interviews with patients can be used to obtain a detailed and nuanced understanding of patients’ preferences, goals, and valuation for shared decision making of multiple outcome conditions (Elwyn et al., 2014). Generally, interviews are conducted until thematic saturation is obtained and key domains identified (Guest et al., 2020). An exemplar of this approach is the collection of foundational data directly from samples of patients iteratively as follows: (1) carry out interviews with patients to identify and develop a comprehensive list of domains and items; (2) use identified domains and capture phrasing from participant-provided “thick description” to create an item pool; (3) refine the items’ wording based on a separate sample of patients using a “think aloud” methodology; (4) conduct focus groups with clinicians to help further refine and reduce the item pool; (5) test the refined item pool to determine psychometric properties of the instrument by administration of the item pool to a larger sample of patient participants; and (6) reduce to a set of final items to create a parsimonious scale by formal testing of psychometric properties (Siminoff et al., 2006).

Timing for Measurement

In addition to standardizing what outcome measures are collected, timing measurements is important to having a full picture of patient outcomes and ensuring that outcome assessments and metrics can be compared across centers and patients. VCA outcomes vary over time based on patient recovery and other considerations, such as their immunosuppression regimen and comorbidities. Additionally, the levels of change for specific domains must be anticipated. For example, ADLs measured with the EQ-5D may not measure improvement because of skewness of distributions. Longitudinal collection of outcome measures is also important. This is demonstrated by

___________________

22 Content validity refers to the degree to which the items or questions on a measure accurately reflect all elements of the construct or concept that is being measured. It assesses whether the items are accurate, relevant, and comprehensive in measuring the construct. Face validity refers to the degree to which a measure seems to be measuring what it claims to measure. It assesses whether the measure appears to be relevant.

current research at the Uniformed Services University investigating longitudinal benefits and outcomes of hand transplantations (Uniformed Services University, 2020).

The timing of measurements across outcome domains is not standardized, and it would be beneficial for this to be standardized across transplant centers. When the OPTN data submission requirements for VCA were updated, the OPTN VCA Committee recommended collecting data at intervals identical to those for other, non-VCA organs (at discharge or 6 weeks post transplant, whichever is first; at the 6-month anniversary; and annually thereafter).23 Based on the published literature24 in VCA as well as anecdotal clinical experience regarding patient burden, assessing patient outcomes frequently for the first 12–18 months at specific time frames, every 6–12 months for up to 5 years post transplant, and then annually thereafter provides data that can both inform clinical decisions regarding treatment planning and answer current research questions about VCA outcomes, while being sensitive to patient and clinician burden considerations.

Baseline Assessments

Baseline assessments have been used to determine the effectiveness of health interventions in other disciplines (Callahan et al., 2006; Fiol-DeRoque et al., 2021; Iverson and Schatz, 2015). In face and hand transplantation, baseline assessments are even more important for quantifying the effects of VCA between pre- and posttransplant health status due to the heterogeneity of the patient population, including differences in the level of upper extremity amputation or facial injury. More research is needed to identify which baseline characteristics are most predictive of posttransplant outcomes in order to optimize outcomes by tailoring the preparations of patients and caregivers during the candidacy phase (Nizzi and Pomahac, 2022). However, much of the published literature on outcomes following face and hand transplantation does not report functional outcomes or preoperative disabilities of a recipient prior to the transplant, making pre- and posttransplant comparisons difficult. The ability to identify the necessity, efficiency, and effectiveness of face and hand transplants without these data for comparison has been a challenge (Fischer et al., 2015; Hein et al., 2020).

___________________

23 See https://optn.transplant.hrsa.gov/media/1119/06_vca_data_collection.pdf (accessed January 3, 2025) for data collection and submission eequirements for VCAs.

24 Lanzetta et al. (2007) noted assessment of outcomes following hand transplantation at 1, 3, 6, and 12 months post transplant and annually thereafter. Lantieri et al. (2016) noted assessment of outcomes following face transplantation at 3, 6, and 12 months post transplant and annually thereafter, with additional assessments if signs of rejection occurred. Two submitted protocols from U.S. transplant centers assessed outcomes following hand transplantation at 6, 12, and 24 weeks post transplant, and every 6 months thereafter, and 3, 6, and 12 months post transplant and annually thereafter (see public access file).

Baseline functional assessments have been made in face transplantation using software to track anatomical landmarks, such as midpoints and the Cupid’s bow (Aguiar et al., 2013).

Baseline measurement is here construed as a dynamic characterization of a candidate’s and caregiver’s preparedness, such that regular assessments throughout the candidacy period (rather than a single pretransplant assessment) align most with a whole health approach to VCA care. Post transplant, regular assessments allow for dynamic, longitudinal tracking of VCA outcomes as patients and caregivers adjust to posttransplant life, encounter difficulties, and mobilize coping strategies to support a resilient adjustment to VCA. Baseline assessments for VCA are sometimes used in psychological assessments (see Chapter 4). In a study that examined three face transplant recipients with psychological baseline assessments on average 8 months prior to surgery, later assessments revealed psychiatric disorders and were used to evaluate the recipients’ mental health post transplant. In this cohort of patients, measurements showed significant improvements in mental health. However, a challenge with psychosocial baseline assessments is patient bias presurgery and the desire to have a “normal” appearance, leading to a potential minimization of psychosocial challenges (Chang and Pomahac, 2013).

Caregiver Burden Measures

PROMs and caregiver outcome measures are highly connected (Seipp et al., 2022), though there is a lack of caregiver burden measurement following face and hand transplantation. Research on liver transplant outcomes has demonstrated that caregiver outcomes can affect recipient outcomes because of excess stress on caregivers affecting patient recovery (Rodrigue et al., 2011). There are no caregiver burden measures used across VCA transplant centers; measures from other medical disciplines may be useful. The Zarit Scale of Caregiver Burden, or the Zarit Burden Interview, is an instrument for measuring caregiver burden that is widely used across multiple caregiver populations (Bédard et al., 2001; Hébert et al., 2000). Following kidney and liver transplantation, the Caregiver Strain Index and the Caregiver Benefit Index are used to evaluate strain, QoL, and perceived benefits by caregivers using “yes” and “no” responses (Rodrigue et al., 2011). Additionally, a similar scale to the previously discussed PGI, the Carer-Generated Index, has been used to assess caregiver concerns (Pakzad-Shahabi et al., 2021).

CHAPTER 6 KEY FINDINGS

In reviewing the evidence, the committee found that no standardized set of outcome metrics have been defined or used consistently across hand and face transplants. Much of the published literature on outcomes following face and hand transplantation does not report preoperative functional outcomes or disabilities of transplant recipients, thus eliminating the ability to compare before and after transplant and evaluate changes in health status. Without these data for comparison, the ability to evaluate the necessity, efficiency, and effectiveness of face and hand transplants has been a challenge. Commonly reported outcomes following face and hand transplantation include overall morbidity/mortality, incidence of transplant rejection/longevity of transplant, improvement in function range relative to pretransplant state, aesthetic appearance, and overall patient satisfaction, though these do not reflect all the key outcomes that would be valuable to measure. The breadth of HRQoL domains is limited for the face and hand transplantation patient population. Based on patient input, additional HRQoL domains (e.g., sensory related) and PROs are needed.

In addition to a lack of consensus for the most important outcome domains for face and hand transplantation, and while there are measurement tools that have been used to assess outcome domains in this population, a variety of measurement instruments are being used to assess the same outcomes, which further confounds the ability to compare studies or pool data. Both psychometric (e.g., SF-12) and utility (e.g., EQ-5D) measures have been used in studies of patients before and/or after transplant. Frequently used hand transplant-specific HRQoL tools include the DASH and shorter QuickDASH questionnaires. Generic measures have the advantage of providing a common yardstick useful in making comparisons of disease/condition burden across diseases and treatment benefits across treatments. Disease/condition-specific HRQoL measures have the advantage in clinical practice and research of greater specificity and responsiveness to the presence and clinically defined severity of a specific condition and can provide clinically actionable information. Without a core outcome set and agreement on standard measures to use, it will be difficult to make valid estimates of risks and benefits, and potentially compare outcomes across centers.

When developing a core outcome set and selecting corresponding measurement instruments, best practices include using a consensus-based process, gathering evidence, grouping outcomes into domains, determining which outcomes are most important to include at a minimum, and selecting measurement instrument(s) for each core outcome domain. Once VCA transplant centers agree upon a core outcome set, these should be curated in a well-designed and properly managed database (see Chapter 8 for more

information on developing a registry). Researchers can use this dataset to estimate rates of key outcomes, such as surgical complications, frequency of rejection episodes, recipient adherence to immunosuppressive therapy, time to full function, and aspects of recipient satisfaction. Such estimates can help inform future decision-making of transplant recipients and clinical teams. Eventually, with a larger set of data, researchers may be able to look for possible associations between aspects of protocols and procedures and outcomes of interest. As noted previously, this does not mean that additional outcomes data could not be collected, though the burden on both patients and transplant center staff should be a consideration.

Patient outcome domains should balance both objective functional outcomes as well as subjective measures through PROs. The health outcomes assessed should include those relating to function, to safety concerns (e.g., transplant rejection, renal failure) and, very importantly, HRQoL outcomes that are important to transplant recipients. A multipronged approach is needed for measurement, with a combination of tools with a balance of existing general measures and health surveys, through repeated pre- and posttreatment measurement, to capture meaningful data and evaluate outcomes comprehensively. It is important to use generic and specific measurements in tandem for this unique population. This combination of measurements would allow for the assessment of universal symptoms and emotions (e.g., physical functioning, self-care, depression, anxiety) by well-established generic measures, with the additional measurement of symptoms and emotions that are more specific to VCA (e.g., aesthetics and body image, integration of the new hand or face). Currently, the existing tools are likely insufficient on their own. Thus, there is a need for the development, evaluation, and validation of face and hand transplant-specific measures with specific attributions to those conditions for limitations in functioning, though the small and heterogeneous patient population may affect validation of these measures. These tools in combination with or supplemented by generic outcome measures will likely provide a more comprehensive view of face and hand transplant outcomes than is currently available. Preliminary work related to PRO measurement following hand transplant and the development of new measures is ongoing.

THE WAY FORWARD AND OVERARCHING CONCLUSIONS

The face or hand transplant experience begins well before the transplant occurs and continues for the rest of the recipient’s and the caregivers’ lives. Part II of this report has reviewed a typical transplant experience involving the patient, the caregivers, and the multidisciplinary team of clinicians. Within the context of the transplant experience, eight focus

areas that form the experience were discussed: patient inclusion/exclusion criteria; patient education; surgical procedures; rehabilitation; immunosuppression and/or immunoregulation; outcome metrics; QoL measures; and patient reporting. Face and hand transplant recipients undergo a rigorous evaluation process, and comprehensive patient education programs provide the information needed to help patients and their families make the shared decision to proceed with transplant. During their shared decision-making process, patients balance the risk–benefit ratio between the benefits of the transplant and the risks and complications of immunosuppression.

Allograft rejection is a major concern and occurs more frequently than with solid organs. There is no one immunosuppressive regimen that works for all patients with any organ type, and a standardized approach to immune management of VCA recipients has not been established. Additional research studies are needed to establish principles underlying a VCA-specific immunosuppression regimen. The short- and long-term care management of the patient, including rehabilitation, immunosuppression, and psychosocial support, occurs over the lifetime of the transplant. The functional outcomes vary based on the level of the transplant, therapeutic immunosuppression levels, and patient goals. No standardized set of outcome metrics has been defined or used consistently across face and hand transplantation, and there is no consensus on the most important outcomes for face and hand transplantation. A variety of measurement instruments are used, with no standardization across transplant centers.

Based on this body of evidence and committee expertise, the committee concludes the following:

Conclusion II-1: A face or hand transplant is one treatment option to be considered by the patient alongside other treatments. Evaluating the alternatives should be done through a shared decision-making process. Thoughtful and realistic decision making, shared among patients, caregivers, and their clinical team, is a key component in achieving positive patient outcomes. Currently, there is no standardization among VCA centers regarding how and what information is shared with recipients and their caregivers.

Conclusion II-2: Ideal selection of face and hand transplantation candidates is best performed through a rigorous screening process by a multidisciplinary team that assesses the candidate’s clinical and psychosocial suitability for the procedure (e.g., immunological status, viral status, functional deficit, health, social support, and ability for self-reliance and adherence with directed care requirements following transplant), as well as the candidate’s commitment to long-term management and

monitoring (e.g., extensive rehabilitation, lifelong immunosuppression, and regular assessments).

Conclusion II-3: There is no standardized psychosocial, surgical, or medical profile of candidates based on the current evidence. Each patient comes to the evaluation process with different circumstances, characteristics, and goals. Current evidence supports certain contraindications and indications, but as more data become available, patient inclusion and exclusion criteria can be expected to evolve.

Conclusion II-4: Repeated assessment over an extended time frame during the candidacy period allows transplant centers to mitigate known biases, identify potential communication challenges, gain a comprehensive understanding of the candidate’s psychological and social readiness for transplantation and adherence post transplant, and provide opportunities for supportive interventions to strengthen the candidate’s ability to navigate the complex demands of transplant. In the committee’s opinion, the assessment of candidates is best completed over a substantive period of time, often lasting around a year. An extended assessment period allows for potential recipients, their caregivers, and their clinicians to prepare for the unique needs of these transplants. This assessment period also allows for appropriate clinical preparation, including surgical rehearsals and other needed clinical interventions.

Conclusion II-5: While surgical techniques and procedures are similar across transplant centers, there are opportunities for surgical innovations and refinements, including new technologies and secondary surgeries.

Conclusion II-6: No standardized approach to immune management of VCA recipients has been established. However, most transplant centers use a regimen that blocks specific alloimmune pathways (e.g., costimulation blockade) to prevent rejection and the development of donor-specific antibodies, decrease the adverse effects of broad metabolic pathway inhibition (e.g., calcineurin inhibition), and avoid associated end-organ toxicities (e.g., calcineurin inhibitor-associated renal failure). Additional research is needed to establish the principles underlying a VCA-specific immunosuppression regimen to reduce rejection.

Conclusion II-7: While patients will likely need individualized rehabilitation approaches, there are core components across rehabilitation protocols that are beneficial to most, if not all, patients. Creativity and adaptability in rehabilitation protocols can still be explored within a standardized rehabilitation protocol to ensure optimal benefit.

Conclusion II-8: Transplant recipient caregivers are critical to the transplant experience and have indicated the need for additional support. Ongoing evaluations ensure that candidates, recipients, and caregivers receive the necessary support and interventions to navigate the challenges and maximize their well-being throughout the transplant experience.

Conclusion II-9: Core outcomes that recipients experience following face and hand transplantation extend far beyond simple medical or surgical metrics of success and failure and pertain to surgical, medical, functional, health related quality of life, psychosocial, and aesthetic outcomes.

Conclusion II-10: Outcome metrics are not systematically collected across transplant programs. Failure to use a systematic, standardized approach, failure to report consistently defined outcomes, failure to use a common set of measures to evaluate those outcomes, and failure to evaluate outcomes against the baseline all prevents the identification of suboptimal approaches and limits the ability to systematically improve outcomes.

Conclusion II-11: Standardized data collection and systematic approaches are needed for the continued maturation of VCA and clinical care. Standardization of measurement instruments that have content validity along with reliability are essential. Both generic and disease-specific health-related quality of life measures are necessary for accurate measurement that is sufficiently comprehensive and to appropriately quantity patient outcomes following face and hand transplantation, as well as objective functional outcome measurements. While there may be challenges with data collection and variability in outcomes due to the small patient population, the pooling of data collected across transplant centers in a standardized manner is critical for the systematic evaluation of outcomes.

Conclusion II-12: A multipronged approach with a combination of tools and measurements is needed to capture meaningful data. A balance of existing general measures and health surveys and the development of specific instruments or items designed to capture the unique experiences and challenges faced by face and hand transplant recipients is essential. Additional research is needed for VCA-specific measures of health-related quality of life, though the small and heterogeneous patient population will likely affect validation of these measures. While new VCA-specific measures and items are being developed, VCA transplant centers should agree upon standard measurements to use.

REFERENCES

Aguiar, P., R. Horta, D. Monteiro, A. Silva, and J. M. Amarante. 2013. Evaluation of a facial transplant candidate with a facegram: A baseline analysis. Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery 132(3):479e–480e.

Aycart, M. A., H. Kiwanuka, N. Krezdorn, M. Alhefzi, E. M. Bueno, B. Pomahac, and M. L. Oser. 2017. Quality of life after face transplantation: Outcomes, assessment tools, and future directions. Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery 139(1):194–203.

Balestroni, G., and G. Bertolotti. 2012. [euroqol-5d (eq-5d): An instrument for measuring quality of life]. Monaldi Archives for Chest Disease 78(3):155–159.

Barker, F., E. MacKenzie, L. Elliott, and S. de Lusignan. 2015. Outcome measurement in adult auditory rehabilitation: A scoping review of measures used in randomized controlled trials. Ear & Hearing 36(5):567–573.

Bédard, M., D. W. Molloy, L. Squire, S. Dubois, J. A. Lever, and M. O’Donnell. 2001. The Zarit Burden Interview: A new short version and screening version. Gerontologist 41(5):652–657.

Bergner, M., R. A. Bobbitt, W. B. Carter, and B. S. Gilson. 1981. The Sickness Impact Profile: Development and final revision of a health status measure. Medical Care 19(8):787–805.

Bernardon, L., A. Gazarian, P. Petruzzo, T. Packham, M. Guillot, V. Guigal, E. Morelon, H. Pan, J.-M. Dubernard, and C. Rizzo. 2015. Bilateral hand transplantation: Functional benefits assessment in five patients with a mean follow-up of 7.6 years (range 4–13 years). Journal of Plastic, Reconstructive & Aesthetic Surgery 68(9):1171–1183.

Billig, J. I., E. D. Sears, B. N. Travis, and J. F. Waljee. 2020. Patient-reported outcomes: Understanding surgical efficacy and quality from the patient’s perspective. Annals of Surgical Oncology 27:56–64.

Bjorner, J. B., M. Rose, B. Gandek, A. A. Stone, D. U. Junghaenel, and J. E. Ware. 2014a. Difference in method of administration did not significantly impact item response: An IRT-based analysis from the Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS) initiative. Quality of Life Research 23:217–227.

Bjorner, J. B., M. Rose, B. Gandek, A. A. Stone, D. U. Junghaenel, and J. E. Ware Jr. 2014b. Method of administration of PROMIS scales did not significantly impact score level, reliability, or validity. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology 67(1):108–113.

Brazier, J. E., R. Harper, N. Jones, A. O’Cathain, K. J. Thomas, T. Usherwood, and L. Westlake. 1992. Validating the SFf-36 health survey questionnaire: New outcome measure for primary care. British Medical Journal 305(6846):160–164.