Advancing Face and Hand Transplantation: Principles and Framework for Developing Standardized Protocols (2025)

Chapter: 4 The Transplant Experience: The Preoperative Stage

4

The Transplant Experience: The Preoperative Stage

Part II of the report details the transplant experience from contemplation of a new treatment through exploration about the possibilities of what a hand or face transplant could mean for a recipient’s life—greater independence, more functional abilities, and renewed opportunities for social integration, including the ability to smile or being able to hold a child’s hand. The experience is potentially life-changing in many ways for the patient, their caregivers, and the multidisciplinary team of health care providers who become part of the patient’s life. Part II explores what is known about this experience, including the decision-making process on whether to proceed with transplantation, the surgery, perioperative management in the hospital, and the return home to reintegrate into family life and society. Throughout these stages, there is much evaluation, education, and monitoring of the patient’s physical and mental health, as well as their psychosocial needs and support mechanisms. After the transplantation, monitoring becomes lifelong due to the continuous need for immunosuppression. Also, an extended and extensive rehabilitation process commences.

Face and hand transplants are complex, and patients and their families interact with many health care providers and experience many different care settings along the way. The transplant experience unfolds along a continuum, but in Part II of this report, for ease of presentation, it is divided into several areas of focus: the preoperative stage, postoperative care management, and outcomes.

FOCUS AREA DEFINITIONS

In developing the principles and strategies for the standardization, assessment, and validation of protocols and standard operating procedures for face and hand transplantation, the committee was asked to focus on eight areas: patient inclusion/exclusion criteria, patient education, surgical procedures, rehabilitation, immunosuppression and immunoregulation, outcome metrics, quality-of-life measures, and patient reporting. These focus areas are introduced below.

Patient Inclusion/Exclusion Criteria

Eligibility criteria define the patient population appropriate for undergoing a procedure. Inclusion criteria specify the characteristics required for treatment, such as stage of disease or specific pathophysiological characteristics (FDA, 2018). In contrast, exclusion criteria are defined as features of the potential patients who meet the inclusion criteria, but present with additional characteristics (e.g., comorbidities, concomitant treatment, or other factors) that could interfere with the success of the procedure or increase the risk of an unfavorable outcome (Patino and Ferriera, 2018).

Patient Education and Shared Decision Making

Patient education is a set of planned educational activities that can use one or more methods to impart information to patients for the purpose of improving patient knowledge and health behaviors and to enhance informed decision making. Patient education programs are not standardized across vascularized composite allotransplantation (VCA) transplant centers. During its deliberations, the committee felt that the patient education focus area required reframing to better reflect the nature of patient-centered care (IOM, 2001; see Chapter 3). Instead, the term “shared decision making” is used throughout the report. Shared decision making is a key aspect of patient-centered care and empowers individuals to play a pivotal role in the production of their own health. It is important to understand how people make decisions when faced with a health care decision for themselves or a family member (either acting as a surrogate decision maker or assisting a patient to make a decision). “Patient education” has moved away from the notion that that health care providers provide static information to passive patients to one in which patients actively engage in decision making (Adapa et al., 2020). The goal of shared decision making in face and hand transplantation is to increase patients’ involvement in medical decision making, strengthening the clinician–patient relationship with outcomes of greater satisfaction with and engagement in care. Shared decision making in VCA

begins when patients present with interest in considering candidacy for VCA and includes the decisions to undergo the selection process inclusive of the medical testing needed to ascertain eligibility and, if deemed eligible, to pursue VCA as well as to follow the recommendations and care management needed to care for and maintain the VCA for as long as the patient has the VCA.1

Surgical Procedures

Surgical procedures are used during surgery to assess, remove, or repair a part of the body (AMA, 2023). In organ transplantation there are two surgical procedures: procurement of the organ from the donor and grafting of the organ to the recipient. These two procedures must be coordinated with each other, and additionally, VCA organ procurement must be coordinated with other solid organ procurement. Organ preservation methods, microsurgical procedures, and extensive coordination among teams of professionals must all be established and rehearsed to optimize the success of a face or hand transplantation.

Rehabilitation

The World Health Organization (WHO) defines rehabilitation as “a set of interventions designed to optimize functioning and reduce disability in individuals with health conditions in interaction with their environment” (WHO, 2024). In research, rehabilitation has been defined as a “multimodal, person-centered, collaborative process including interventions targeting a person’s capacity and/or contextual factors related to performance, with the goal of optimizing the functioning of persons with health conditions currently experiencing disability or likely to experience disability, or personals with disability” (Negrini et al., 2022, p. 333). Rehabilitation following a surgical procedure is a crucial part of the recovery process to ensure that the patient regains strength and mobility, depending on the procedure. Postoperative therapies for hand transplants can include splinting to protect the tissues, range of motion exercises, electrical stimulation, strengthening, cognitive training, and scar management (Bueno et al., 2014). For face transplant recipients, physical therapy and speech therapy are components of the rehabilitation process.

___________________

1 See presentation by Heather Gardiner, Temple University, at April 17, 2024, webinar for more information on the VCA shared decision-making model. https://www.nationalacademies.org/event/42240_04-2024_principles-and-framework-to-guide-the-development-of-protocols-and-standard-operating-procedures-for-face-and-hand-transplants-webinar-2 (accessed December 16, 2024).

Immunosuppression and Immunoregulation

Immunosuppression is “a reduction in the capacity of the immune system to respond effectively to foreign antigens” (Rice, 2019, p. 159). Immunoregulation (or immunomodulation) attempts to modulate the cytokines, signaling pathways, and cells of the immune system that normally regulate an immune response to surgical tissue injury and foreign antigens in the allograft. Immunoregulation is designed to prevent allograft rejection and an allograft-versus-host reaction by shifting the balance of activated immune cells away from those that cause allograft destruction to those that tolerate the allograft (Wood et al., 2012). Immunosuppression regimes in face and hand transplantation draw from solid organ transplantation (Huelsboemer et al., 2024).

Outcome Metrics

Outcome metrics are used to convey and reflect the impact of a particular health service, procedure, or treatment and how it relates to patients. Outcome metrics can be relatively straightforward, such as surgical mortality rates, but can also be more complex, based on multiple factors and mathematical models (AHRQ, 2015). Outcome metrics can measure impacts of an intervention at both the individual and population level.

Quality-of-Life Measures

The World Health Organization defines quality of life (QoL) “as an individual’s perception of their position in life in the context of the culture and value systems in which they live and in relation to their goals, expectations, standards, and concerns” (WHO, 1998, p. 8). Both negative and position outcomes have an impact on one’s QoL (Teoli and Bhardwaj, 2021). QoL differs from health-related quality of life (HRQoL) in that the latter is a measure that explores the connection between health and QoL. HRQoL metrics are used in order to evaluate a patient’s physical state and psychological well-being and can influence care management plans (Addington-Hall and Kalra, 2001). HRQoL is also a helpful indicator of overall health as it captures information on the physical and mental health status of individuals and on the impact of health status on QoL (Palermo et al., 2008; Revicki et al., 2014). HRQoL is usually assessed by multiple indicators of self-perceived health status and physical and emotional functioning. HRQoL measurements and outcomes differ depending on disease, prognosis, and personal preference of the patient (Addington-Hall and Kalra, 2001).

Patient Reporting

Medical technology enables the measurement of numerous parameters and markers that provide data on the physical, physiological, and biochemical status of the patient. However, it is not able to provide all of the necessary data about the state of a patient (Deshpande et al., 2011). Some data can be obtained only from the patient, including patient-reported outcomes and experiences (Neubert et al., 2020). A patient-reported outcome is “any report of the status of a patient’s health condition that comes directly from the patient, without interpretation of the patient’s response by a clinician or anyone else” (Deshpande et al., 2011, p. 137).

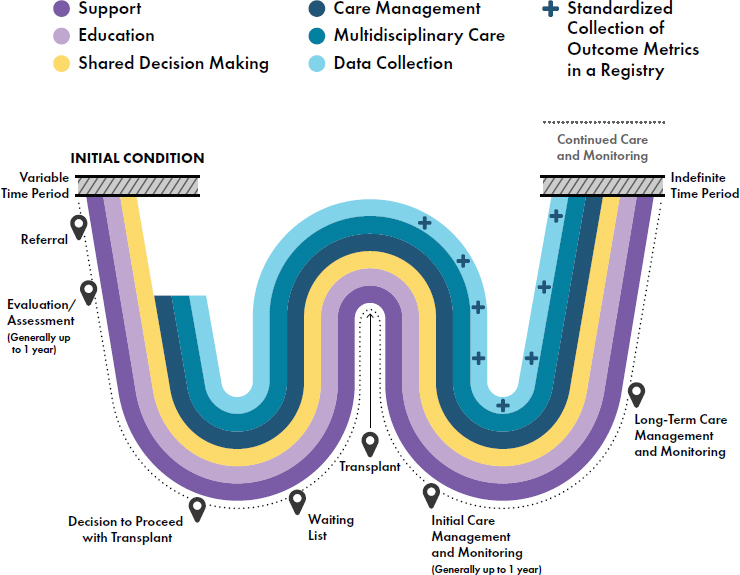

These eight focus areas help to provide a framework of the transplant experience. Figure 4-1 depicts the major stages of the transplant experience—the preoperative stage, surgical procedures during transplant, and the initial and long-term care management, monitoring, and data collection of outcomes—for a typical recipient of a face or hand transplant. Key steps of the transplant experience are highlighted in the figure, and the eight focus areas are discussed in detail in Chapters 4–6.

SOURCE: Adapted from NASEM, 2022b.

MULTIDISCIPLINARY TEAMS

The use of multidisciplinary teams provides a wide range of benefits within health care, such as improved patient care and satisfaction, reduction of hospital stays, increased communication between medical specialties, fewer clinical errors, and decreased patient mortality (Korylchuk et al., 2024). Patients and caregivers are also important members of the multidisciplinary team. Transplant disciplines, such as heart and kidney, rely on multidisciplinary teams of specialized personnel that collaborate across their specialties and coordinate their efforts to identify, assess, and list potential transplant candidates and to prepare for the surgery, recovery, rehabilitation, monitoring, and care management of the transplant recipient (Cajita et al., 2017; Costanzo et al., 2010; De Pasquale et al., 2014) (see Box 4-1 expertise areas of team members involved in VCA). Continuous education and training to promote overall team competence is critical. Team science is also an important aspect of multidisciplinary care. Team science is defined as “scientific collaboration, i.e., research conducted by

BOX 4-1

Areas of Expertise of the Multidisciplinary Team Members Involved in Face and Hand Transplantation

| Anesthesia | Nutrition |

| Caregiving | Pathology |

| Ethics | Pharmacy |

| Dentistry (face) | Psychiatry/Psychology |

| Dermatology |

Physiatry/Rehabilitation

Occupational therapy Physiotherapy |

| Hematology | Respiratory therapy (face) |

| Infectious disease | Social work |

| Internal medicine | Speech/language therapy (face) |

| Immunology |

Surgery

Plastic, Reconstructive, Oral maxillofacial, Orthopedic, Transplant, Hand |

| Neurology | Transplant Coordination |

| Nursing | Transplant Medicine |

SOURCE: Adapted from Alolabi et al., 2017.

more than one individual in an interdependent fashion, including research conducted by small teams and larger groups” (NASEM, 2015, p. 2). The input–mediator–output–input framework of team science has previously been applied to VCA to examine how to create an effective team (Griffin et al., 2022). Multidisciplinary teams are essential aspects of VCA programs and are critical in the patient evaluation process (Zuo et al., 2024).

Caregivers are recognized as essential members of patient care teams who play a critical role in maximizing patient outcomes (Stephenson et al., 2022). In organ transplantation, caregivers may interact with other members of the team to receive information about how to effectively care for the transplant patient and act as a line of communication between patient and clinician (Jesse et al., 2021). During the preoperative stage, caregivers help patients comprehend large amounts of information, support them through the evaluative testing, and collaborate in the shared decision-making process. They can also provide emotional support during the postoperative phase and throughout the transplant experience, including motivating patient adherence to follow-up care and with their medications. For face and hand transplantation candidates, their caregivers have typically been involved with them for some time, providing care and support since the initial injury or condition.2 Caregivers can be a heterogeneous mix of people.3 These include family members, such as a spouse or parent, friends (Within Reach, n.d.-c), members of the patient’s community,4 and even members of the transplant team (Within Reach, n.d.-b), and can change over time, due to changes in the relationship with the patient, the patient’s needs, and whether the caregiver feels overburdened or strained (Deng et al., 2024). Caregiver roles may also shift as patients age.5 Caregivers often participate in initial visits and help communicate patient progress, contributing to overall transplant success (Zuo et al., 2024).

Patient advocates and patient navigators can also be members of the clinical team. These individuals are typically trained personnel who assist patients with navigating the health care system, ensure that the patient’s needs are met, and work to eliminate barriers to care (Freeman and Rodriguez, 2011; McBrien et al., 2018). A patient advocate helps enhance communication between patients, caregivers, and their health care providers, in addition to organizing support for a patient’s needs (NCI, n.d.; The Joint Commission, n.d.). Patient navigation services include referral to additional

___________________

2 Based on testimony from lived experience consultants.

3 Caregivers are typically female (two-thirds) and female caregivers often report higher burden levels compared to male caregivers (Pacheco Barzallo et al., 2024).

4 See information-gathering webinar on March 22, 2024. https://www.nationalacademies.org/our-work/principles-and-framework-to-guide-the-development-of-protocols-and-standard-operating-procedures-for-face-and-hand-transplants (accessed December 19, 2024).

5 “I know that either [their sister or daughter] will watch over me when I need it” – Lived experience consultant testimony on plans to rely on caregivers as they age.

services, care coordination, treatment support, and clinical trial assistance (Wells et al., 2018).

THE PRETRANSPLANT EXPERIENCE

There are many stages that take place before a patient proceeds with face or hand transplantation. These include the initial qualifying condition for a transplantation, the referral process, the information-gathering and education stage, the formal evaluation process, the ongoing shared decision-making process, the decision to proceed with a transplant, and the experience of being on the waiting list and any pretransplant management, which varies based on patient characteristics and needs.

Conditions Leading to Transplant

“I had lost both my arms and legs below my elbows and knees, so my feet and hands. Needless to say, it was very hard and devastating for me and my family. … The worst part was that I needed help to take a shower every day and was dependent on other people … prosthetic hands do not replace real hands.”

— Bilateral hand transplant recipient, presented testimony to the committee at the March 22, 2024 public webinar

As is the case with other forms of organ transplantation, reliable data are lacking on the number of people who may benefit from face and hand transplants (NASEM, 2022b). For most patients the face and hand transplantation experience begins well before they initiate conversations, assessment, and deliberations about the transplant process. It begins when the person undergoes a trauma, facial deformity, or amputation resulting from injury, infection, or other medical condition that cannot be successfully restored using standard reconstructive procedures. Nearly all patients who have been candidates for either face or hand transplantation have experienced sequelae of their injuries that have greatly limited their independence, comfort, health, and overall QoL. Face and hand transplants are currently considered as a treatment option only when conventional methods of reconstructive surgery have failed (e.g., microvascular tissue transfers), or alternative treatments (e.g., prostheses) have produced unsatisfactory functional outcomes. For patients seeking a hand transplant, this can include the fine motor capabilities many of us with functioning hands take for granted, such as the ability to write or to raise a fork to one’s mouth or the ability to shift

one’s weight in a wheelchair. For patients seeking a face transplant, the role of the face in social existence cannot be overstated, but many patients also experience effects of their injury that limit their ability to eat, to breath, to see, and more. There has been at least one case where face transplant was considered as the initial solution and performed on an emergency basis to save the life of the recipient (Maciejewski et al., 2016). There are a variety of indications that may result in face and hand transplantation. Based on the Organ Procurement and Transplant Network (OPTN) 2022 data report, the most common primary diagnoses in the United States for those that received a VCA were trauma (41 percent, 14/34) and infection (24 percent, 8/34) (Hernandez et al., 2024).

Indications for Face Transplant

A variety of injuries and illnesses can result in the need for a face transplant. Such injuries and illnesses can create physical and psychological challenges for the patients. Issues with eating, speaking, breathing, and using facial expressions are all common with face transplant patients. Additionally, psychological challenges are not uncommon. One study found that 23 percent of face transplant patients had posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) 1 year after their trauma (Coffman et al., 2011). It can be difficult to estimate the number of patients who would qualify for a face transplantation procedure because the numbers of those with qualifying conditions is not proportionate to the circumstances that have led to actual transplants. For example, in the United States, 7 out of the 18 face transplants performed were due to ballistic trauma (Diep et al., 2021). Gun violence in the United States, including homicides, suicides, and mass shootings, has increased over the past decades and reached a peak in 2021 (Hemenway and Nelson, 2020; Menezes et al., 2023). Despite the increasing numbers of gunshot injuries, it is not known how many of these patients would benefit from or qualify for a face transplant. In a population study that examined gunshot injuries occurring between 2015 and 2017, an average of 7,000 per year involved the head and neck (Menezes et al., 2023). It is estimated that up to two-thirds of all burns are associated with the face in some manner (Clark et al., 2020). While not common, acid attacks can lead to severe facial disfigurement. Electric, chemical, and thermal burns accounted for 8 of 18 face transplants in the United States. In addition to gunshot injuries and burns, animal attacks (1/18), and necrotizing infection (1/18) have also led to face transplants in the United States (see Appendix C for a timeline of face transplants, which includes the indication leading to face transplant).

Indications for Hand Transplant

“To understand why I would decide to undergo a double arm transplantation … you need to imagine life as a quad amputee, trying to navigate the world both with and without prostheses. … [A]side from my arms and legs, I also lost my teaching job, my apartment (a second-floor walk-up, useless for someone in a wheelchair), and my ability to interact comfortably with so many things in our able-bodied, hand-oriented world.”

— Bilateral hand transplant recipient, written testimony to the committee

“VCA represented the best chance I have currently of regaining the function I was lacking, including sensation … the psychosocial component of VCA. … [N]o one looks at arms the way they look at prostheses, no matter how realistic. “

— Bilateral hand transplant recipient, presented testimony during lived experience focus group session

“There seems to be a looming question of whether a hand transplant is better or worse than a prosthetic. … [I]t’s better by a wide margin.”

— Unilateral hand transplant recipient, written testimony to the committee

The primary condition leading to the need for a hand transplant is an amputation. Amputation is defined as the “partial or total removal of a limb, or part of a limb with the aim of salvaging the life of the individual or improving function in the remaining part of the limb” (Ligthelm and Wright, 2014, p. 99). In the United States there are approximately 41,000 upper extremity amputations per year (Heineman et al., 2020). Statistics indicate that trauma is the major cause of upper limb amputations (68.8 percent) and that 90–92 percent of trauma cases are caused by industrial accidents worldwide (Shahsavari et al., 2020). Additional factors that can lead to loss of an upper limb are burns, high-voltage injuries, infections, and congenital conditions. In military and veteran populations, amputations are most commonly necessitated by combat-related injuries (Fries et al., 2020). Upper limb amputations cause numerous physical and psychosocial challenges to daily independent function, including disruptions to QoL, functional limitations, and psychological distress (De Putter et al., 2014). Half of patients experiencing amputation encounter challenges, including the physical environment, climate, and income (Gallagher et al., 2011). Treatment options for upper extremity amputations include prosthesis,

replantation, and VCA, with prothesis being the most common treatment option (Finnie et al., 2022).

Use of Upper Limb Prostheses

For people who have lost one or both of their upper extremities, protheses may help them regain some dexterity, function, cosmesis, and independence they had prior to their amputation (Engdahl et al., 2024; Fink and Diamond, 2023; NASEM, 2017). Recent advances in amputee and prosthetic care have improved patient outcomes (Frey et al., 2022). For example, innovative surgical techniques are successfully addressing pain management, while techniques to improve prosthesis control (e.g., targeted muscle re-innervation and osseointegration) and newer materials like silicone are improving the aesthetics and utility of prostheses (Latour, 2022). Regular use of a prosthesis has been demonstrated to yield considerable benefits, including greater levels of employment, improved QoL, and a reduction in both psychiatric symptoms (e.g., depression, anxiety, and self-esteem) and secondary health conditions (e.g., obesity, cardiovascular disease, and diabetes) (Pasquina et al., 2015). Despite these benefits, some upper limb amputees abandon their prostheses because they are unsatisfied with them (Biddiss et al., 2007; Fitzpatrick et al., 2022; Resnik et al., 2019; Salminger et al., 2022; Wright et al., 1995). The reasons people abandon their upper limb prosthesis include inability to achieve a level of desired function as well as comfort issues, such as those related to weight, temperature, and perspiration (Smail et al., 2021), and these factors may influence the consideration of alternative treatments, such as hand transplantation.6 To increase the likelihood of acceptance, proper fitting and training on the use of the prostheses by an experienced rehabilitation team are critical (Gaine et al., 1997; Resnik et al., 2012).

Rehabilitation professionals may not be aware of hand transplantation even though they work with patients who have upper extremity amputation and use prostheses who may qualify for the procedure. Members of the rehabilitation team are in a unique position as it relates to providing information about hand transplantation and potentially referring interested candidates to a VCA transplant center for additional information and assessment.

___________________

6 Patient testimony during March 22, 2024, webinar about why they pursued hand transplant following dissatisfaction with upper limb prosthetics. See https://www.nationalacademies.org/event/42167_03-2024_principles-and-framework-to-guide-the-development-of-protocols-and-standard-operating-procedures-for-face-and-hand-transplants-webinar-1 (accessed October 7, 2024).

The State of Patient Awareness about VCA and Referral of Potential Candidates

Unlike with solid organ transplantation, which has been the subject of extensive public education campaigns, VCA remains largely unknown to the general public. This has implications for both the donation process (see Chapter 2) and for people who might be candidates for a face or hand transplant. An important component of the patient experience is the referral of potential candidates by a clinician or when a potential candidate contacts the transplant center directly. Prior to referral and evaluation at a transplant center, potential face and hand transplant recipients must first become aware of the transplant as a treatment option. Current VCA public education materials have not effectively educated people about VCA, including the patient population that could become VCA donors (Van Pilsum Rasmussen et al., 2020) or those who could benefit from the procedure. One study found that among people with limb loss who were not VCA recipients, knowledge about upper limb transplantation varied, and the study concluded that there was a need for improved education about all of the treatment options for limb loss patients (Finnie et al., 2022). Education among the transplant, trauma, and medical communities may also help with patient referral. An analysis of hand transplantation referrals from one institution found that of 89 referrals analyzed, 69 were self-referrals, while only 20 were physician referrals (Kiwanuka et al., 2017). The study also found that physician referrals led to more screened and accepted patients than self-referrals, which more often resulted in immediate exclusion. In a review of referrals and outcomes for potential face transplantation patients, nearly 50 percent of the 72 patients examined were physician referrals; similar to the case with hand transplantation, patients who were referred by physicians were more likely to be ultimately transplanted than self-referrals (Kiwanuka et al., 2016b). A challenge related to patient awareness and referral is the public availability of patient inclusion and exclusion criteria. Not all VCA transplants centers display their selection criteria on publicly available websites. This may cause confusion for patients who are interested in pursuing transplantations. Clinicians may also have challenges referring their patients to specific programs if the criteria are not clear (Parker et al., 2022).

The Evaluation and Assessment Process

“One of the things to standardize is patient selection. I think the key to success is to treat the right patients.”

— Dr. Patrik Lassus, University of Helsinki, Finland, presented testimony to the committee at the March 22, 2024, public webinar

“I think the psychological evaluations should continue throughout the waiting period, not just one time … because anybody could say yes, I’m prepared, but you’re never really 100 percent prepared.”

— Bilateral hand transplant recipient, presented testimony during lived experience focus group session

Someone considering a face or hand transplant has likely been party to other treatments, such as reconstructive surgery for an injured face or a prosthesis for an upper limb amputation. These are important prerequisites before someone is evaluated as a candidate for VCA. Face and hand transplantation candidates undergo a rigorous screening process of medical, surgical, and psychiatric evaluations by a multidisciplinary team to assess their clinical and psychosocial suitability for the procedure. For example, hand transplant evaluations are underpinned by an occupational and physical therapy assessment of baseline functional status, while face transplant candidates demonstrate their abilities to eat, breathe, speak, and see, among other key functions, by speech language pathologists and other team members. For all VCA candidates, there is also extensive laboratory work that assesses the candidate’s immunological, metabolic, and infectious status as well as comorbidities that would preclude transplantation, along with ABO and tissue typing and panel reactive antibody testing. Candidates must demonstrate their ability to cope with the demands of therapy after transplant, and imaging technologies are used to assess anatomy (MacKay et al. 2014; Mendenhall et al., 2018b). Indications for face and hand transplant are based on both the expected success of the transplant and the likely impact on function and QoL for the patient (Alolabi et al., 2017). Only candidates who meet specific eligibility criteria are placed on the waiting list for transplant and ultimately transplanted.

Multiple studies have emphasized that multidisciplinary teams should be involved in the evaluation process, including surgeons (e.g., orthopedic, plastic, and transplant), clinicians (e.g., transplantation medicine, radiology, pathology, occupational and physical therapy, physiatry, social work), psychologists and psychiatrists, ethicists, and caregivers (e.g., social support

networks) (Longo et al., 2024; Mendenhall et al., 2018b) (see the section above on multidisciplinary teams). The approach to both the medical and psychosocial assessment of candidates has evolved as VCA has matured (Diep et al., 2021; Smith et al. 2021). The assessment process has not always been sufficiently comprehensive across transplant centers, which may have contributed to mixed and marginal outcomes historically.

Psychosocial Evaluation

Presurgical psychological screening is “a projection of the extent to which psychological factors may influence surgery results” (Block and Sarwer, 2013, p. 5). This screening process allows for mental health professionals to evaluate the psychosocial state of candidates, and whether moving forward with the surgery is in the best interest of the patient and if any psychosocial interventions are needed (Block and Sarwer, 2013). Psychological screening typically follows three general steps: (1) information gathering from patients, caregivers, and psychometric testing, (2) empirical assessment of the psychosocial risks, and (3) treatment suggestions (Block and Sarwer, 2013). Psychosocial factors interfering with behavioral adherence may adversely affect long-term transplant outcomes, such as QoL, so psychosocial functioning is a critical part of pretransplant evaluation for face and hand transplantation (Jowsey-Gregoire et al., 2016; Kumnig et al., 2022a; Shanmugarajah et al., 2011; Smith et al., 2021). A study that examined psychosocial data submitted to the International Registry on Hand and Composite Tissue Transplantation (IRHCTT) between 1998 and 2016 found that anxiety, depression, PTSD, and family support are associated with postsurgical transplant status (Kinsley et al., 2020). Relying on comprehensive psychosocial assessments is essential for enhancing patient selection, presurgical preparation, postsurgical rehabilitation, and follow-up care (Hummel et al., 2023; Kimberly et al., 2022; Kumnig et al., 2022b). By understanding a patient’s emotional state, social support networks, and coping mechanisms, health care professionals can identify potential challenges and tailor treatment strategies to maximize their effectiveness. For example, a patient struggling with depression may require additional support during recovery, while a patient lacking social support may benefit from connecting with community resources.

Psychosocial evaluations include assessment of psychological status, personal distress, and self-perception as well as of overall mental health and stability, the presence of addictions or other red flags, family support, coping skills, adherence mechanisms, concept of body and self, QoL, and financial situation (Hummel et al., 2023; Longo et al., 2024; Mendenhall et al., 2018b). Psychosocial domains considered during evaluation include personality, cognitive function, mood, behavioral adherence, social support,

and substance use history, among others (Smith et al., 2021). However, standardized elements for the pretransplant psychosocial evaluation have not been developed (Jowsey-Gregoire and Kumnig, 2016; Kumnig and Jowsey-Gregoire, 2015; Kumnig et al., 2022a). The Chauvet Workgroup has been involved in attempts to reach consensus on domains of the psychosocial evaluation of candidates, but these developments have neither been agreed to nor implemented by all VCA centers (Kumnig et al., 2022a,b; see Appendix D for more information on the Chauvet Workgroup). Each transplant program has different thresholds of inclusion and exclusion criteria, despite efforts in the VCA community to develop universal standards.

While there are no validated psychosocial instruments specifically designed for use among this unique population (Jowsey-Gregoire and Kumnig, 2016), there are general, validated tools that are used to evaluate face and hand transplantation patients’ characteristics related to behavioral adherence, substance use, personality, coping strategies, social support, and emotional and cognitive function.7 Consistent psychosocial guidelines regarding exclusion criteria are crucial for reducing biases in access to care. These guidelines can help ensure that decisions in the transplant process are based on objective, evidence-based criteria. However, each patient is best treated as an individual through a process that considers his or her unique circumstances and needs, rather than relying on broad, potentially discriminatory criteria.

In addition to support for patients, caregivers may also benefit from having access to psychological professionals throughout the transplant process. Caregivers may need to make large life changes (Hummel et al., 2023), such as leaving their jobs in order to assume full-time caregiving responsibilities.8 There are no formal support groups or psychological support

___________________

7 These measures include the clinician-measured PTSD scale, the Life Event Checklist, the Beck Depression Inventory II, the Beck Anxiety Inventory, the Norbeck Social Support Questionnaire, the Wide Range Achievement Test- 4, the Wechsler Abbreviated Scale of Intelligence, and the Repeatable Battery for the Assessment of Neuropsychological Status. Additional psychosocial assessment tools can also be used in the evaluation process, including the Derriford Appearance Scale (DAS59) to measure psychological distress and dysfunction that may come from severe facial disfigurement (Harris and Carr, 2001); the Everyday Discrimination Scale to examine and measure discrimination that may lead to health effects such as anxiety, depression, high blood pressure, and stroke (Bastos and Harnois, 2020); the Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale (CD-RISC) to measure resilience and coping strategies (Connor and Davidson, 2003); the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT) to screen for alcohol-related behavioral challenges (NIDA, n.d.-a); the Current Opioid Misuse Measure (COMM) to measure risk of potential medication misuse by examining patient characteristics (Butler et al., 2010); and the Fagerström Test for Nicotine Dependence (NIDA, n.d.-b). The last three measurement items are especially important in VCA, as substance abuse may be considered an exclusionary condition for transplant, depending on individual patient circumstances and the transplant center protocol. See Chapter 5 for information on psychosocial assessment to inform care management and Chapter 6 for psychosocial outcome metrics.

8 Based on lived experience consultant testimony.

specifically for caregivers, resulting in many caregivers feeling alone and unprepared for caring responsibilities following transplantation.9

Evaluation of Suitability for Rehabilitation Commitment

Preoperatively, the rehabilitation team must emphasize and evaluate the candidate’s ability to cope with the intensive and prolonged rehabilitation process and understanding of the rehabilitation commitment. Caregivers and the patient must demonstrate that they understand the demands of the rehabilitation process and feel they can follow the intensive, long-term treatment regimen. Goals are outlined, and a plan of care is prepared (Boczar et al., 2023; Bueno et al., 2014). Education and communication are critical components of this evaluation process. The candidate’s baseline functional status is also assessed. For hand transplant patients, this includes a history of injuries; work occupation; and sensory status, baseline pain, range of motion, strength, and dexterity of the upper extremities, along with functional analyses and measures of the ability to perform activities of daily living. Potential face transplant patients undergo a similar set of assessments but with a focus on their current ability to eat and breathe without assistance, degree of sensory deficits, and ability to communicate intelligibly through both speech and nonverbal facial expressions (Fischer et al., 2015).

Patient Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

Eligibility criteria define the patient population appropriate for undergoing a procedure. Common exclusion criteria include characteristics that make candidates likely to be lost to follow-up, miss scheduled appointments, have comorbidities that could diminish the probability of procedure success, or increase their risk for adverse events (Patino and Ferreira, 2018). Whether the benefits outweigh the potential risks is also a primary consideration for determining eligibility criteria (FDA, 2018). Eligibility for a clinical procedure is intended to ensure that the procedure is more likely to benefit than to harm the candidate and must be carefully designed and intentionally applied to both address the question being evaluated and achieve accurate and meaningful results. However, unintentional and systematic exclusion of certain groups can come from restrictions on eligibility criteria (Langford et al., 2014; McKee et al., 2013; NASEM, 2022a; Quiñones et al., 2020). A 2022 National Academies report, Improving Representation in Clinical

___________________

9 Based on lived experience consultant testimony and caregiver testimony at the June 6, 2024, public webinar. https://www.nationalacademies.org/event/42579_06-2024_principles-and-framework-to-guide-the-development-of-protocols-and-standard-operating-procedures-for-face-and-hand-transplants-webinar-4.

Trials and Research, found that stringent eligibility criteria had “resulted in the exclusion of underserved patient populations (much to the detriment of inclusive research)” (NASEM, 2022a, p. 99).

VCA candidates are “typically medically stable at the time of evaluation, have often considered or been evaluated for other conventional therapeutic modalities, and approach transplantation to improve functionality and/or quality of life rather than survival” (Smith et al., 2021, p. 1). While there are common inclusion and exclusion criteria across VCA transplant centers, there is no consensus at this point on standardized criteria for inclusion or exclusion of candidates, and patient selection criteria may change over time with more research and transplants performed. Across VCA transplant centers, common inclusion criteria for potential face and hand transplantation recipients include being between 18 and 65 years old, having no co-existing medical or psychosocial conditions, having a strong desire to receive a face or hand transplantation, testing negative for HIV, being a non-smoker, and, for female-identifying patients, testing negative for pregnancy.10 Common exclusion criteria include active conditions such as sepsis, HIV, tuberculosis, malignancy, hepatitis B or C, infections, and a history of medical non-adherence to postoperative protocols.11 Transplant center criteria have evolved based on knowledge learned from prior experiences, such as challenges with immunosuppression (Parker et al., 2022), as well as allograft rejection and failure.

Despite these common selection criteria, patient selection for face and hand transplantation remains challenging. For one, patient inclusion and exclusion criteria are not standardized among VCA transplant centers (Parker et al., 2022). At one level, criteria are based on the expected success of the transplant and the function of the allograft (Alolabi et al., 2017), but that belies the reality that the assessment of patient inclusion and exclusion criteria can be complex, the body of evidence is still limited because of the limited number of patients, and certain institutions prioritize different areas of the criteria based on their own experiences, leading to subjective judgments by different transplant centers regarding aspects of patient selection.

Some areas of patient inclusion and exclusion criteria cut across both face and hand transplantation, including social support, history of suicide attempt, and strong motivation to proceed with transplant. The importance of a robust social support system for patients considering VCA cannot be overstated. While a spouse or partner is frequently the main person in this

___________________

10 Based on submitted protocols from U.S. VCA transplant centers.

11 Ibid.

support system, a solid social network may also include extended family, friends (Within Reach, n.d.-b), and community members.12

A history of suicide attempt may raise concerns, but currently there is no consensus among face transplant centers on whether suicidality should be considered a contraindication (Parker et al., 2022). Previous face transplant recipients have had a history of a suicide attempt. At least three patients in the United States have received a face transplant as a result of self-inflicted gunshot wounds (CNN, 2024; Kiwanuka et al., 2016a), and worldwide, at least 18 face transplantations have been the result of ballistic trauma, 5 of which were known to be self-inflicted (McQuinn et al., 2019). Suicide attempts are often complex and multifaceted events, and their significance can vary depending on each patient’s history and psychological construct. Some people may attempt suicide as a means of coping with overwhelming distress, expressing emotional pain, or resolving conflicts. Careful consideration through psychosocial analysis is essential to understand the factors that facilitated or protected against suicide in the patient’s past (La Padula et al., 2022). Therefore, a thorough assessment of the patient’s history, current psychological state, and coping mechanisms is crucial in determining the appropriateness of their inclusion. This assessment benefits from a multidisciplinary approach, involving psychologists, psychiatrists, and social workers. As part of the assessment process, special attention may be given to how open the patient is about their mental history and the suicide attempt, such as a description of the attempt, substance use, and how things in life are different than before the attempt (Kiwanuka et al., 2016a). The circumstances after the suicide attempt, including their recovery trajectory and coping skill-building, whether the patient received any kind of mental health counseling, and whether they are open to continuing treatment in the future, are also relevant (Kiwanuka et al., 2016a). A challenge with screening potential face transplant patients who have a history of a suicide attempt is the potential for repeat attempts. For those who attempted suicide with a firearm, the risk of repeat attempts is generally higher compared to other methods (McQuinn et al., 2019). However, it has been suggested that patients who receive a face transplant after a suicide attempt may have a decreased risk of a repeat attempt due to a reduction of psychological symptoms associated with the initial suicide attempt (McQuinn et al., 2019). For recipients with a previous suicide attempt, a comprehensive psychosocial care management plan is critical, as their psychosocial needs may differ from face transplant candidates who

___________________

12 See https://www.nationalacademies.org/event/42167_03-2024_principles-and-framework-to-guide-the-development-of-protocols-and-standard-operating-procedures-for-face-and-hand-transplants-webinar-1 (accessed December 16, 2024).

survived other traumatic accidents (Nizzi et al., 2017) (see Chapter 6 for more information).

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria Specific to Face Transplantation

There are some areas of patient inclusion and exclusion criteria that are specific to face transplant that merit further discussion, particularly as it relates to medical and rehabilitation criteria.

The 2019 Bethesda, Maryland, Summit Conference identified the following patient selection criteria for face transplantation: “(1) extensive soft tissue damage of at least 30 percent of the total facial surface with extensive mid-face involvement; for unilateral cases there should be at least two mid-facial structures destroyed (eyelid, nose, lips) and for bilateral cases at least one mid-facial structure destroyed; (2) conventional reconstruction will not yield acceptable aesthetic and functional outcomes; and (3) have completed an experience center’s multidisciplinary team’s assessment and approval of their psychosocial, physiologic, and physical health” (Tintle et al., 2022, p. 42). Additionally, a two-step Delphi study recommended that face transplants should be specific to extreme facial and midface defects that involve key anatomical structures, that face transplants are indicated for defects with a complete loss of the orbicularis oculi and/or orbicularis oris muscles, and that a past medical history of benign tumor should not be considered as a contraindication to face transplantation (Longo et al., 2024; see Chapter 5 for more information on the soft-tissue and skeletal tissue defect classification system for facial transplantation). Some VCA centers require that 25 percent of the facial tissue be affected in order to be considered for a transplant (BWH, n.d.), while others are less specific on the amount of damaged facial tissue required. The general indications, contraindications, and relative contraindications based on expert opinion and the published literature for face transplantation are summarized in Box 4-2.

The debate surrounding blindness as an exclusion criterion for face transplant within the VCA community is ongoing. While it was initially considered a contraindication due to the assumption that face transplant would primarily benefit patients with functional vision, VCA has since evolved significantly (Carty et al., 2012). The successful transplantation of faces onto blind patients has demonstrated that the subjective experience of disfigurement extends beyond visual cues. Patients with severe facial disfigurement often endure social exclusion, and increased social anxieties, leading to self-isolation and psychological distress (Carty et al., 2012). These factors, rather than the absence of vision, can have a devastating impact on a patient’s QoL. Given the history of restoring facial aesthetics and improving the well-being of blind patients, some believe that blindness should not be considered an exclusion criterion (Carty et al., 2012).

BOX 4-2

Common Indications, Contraindications, and Relative Contraindications for Face Transplant

Indications

- Severe facial disfigurement (e.g., extreme facial and midface defects that involve key anatomical structures, defects with a complete loss of the orbicularis oculi and/or orbicularis oris muscle) that involves the majority of the facial surface area

- Presence of functional impairments

- Existing conventional reconstructive options are expected to lead to an inferior result

- Motivation to proceed with transplant

Contraindications

- Inadequate social support

- Significant or untreated systemic diseases, multiple impairments, and/or coexisting medical conditions (e.g., active malignancy, chronic infection)

- Current pregnancy

- Severe, active, or poorly controlled psychiatric disorders that are likely to decompensate or affect the ability to recover, participate in therapy, or comply with medication regimen

- Sufficient tissue availability for other reconstructive options

- Active end-organ dysfunction or failure

Relative contraindications

- History of certain malignancies

- Technical and anatomic issues risking successful operative outcomes

- Inability to find an immunologically suitable donor in highly sensitized patients

- History of poor medical adherence

- Immune system condition (e.g., immunocompromised)

SOURCE: Summarized by committee from published literature and expert opinion. Adapted from Kantar et al., 2021; Longo et al., 2024; Tintle et al., 2022.

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria Specific to Hand Transplantation

Indications for hand transplant are based on both the expected postoperative success of transplant and the impact on function for the patient. Common indications, contraindications, and relative contraindications based on expert opinion and the published literature for hand transplantation are summarized in Box 4-3.

Preoperative Education and the Shared Decision-Making Process

“Transparency is a must and should be a core component for all recipients and potential recipients of both hand and face transplantations. … [T]he goal of transparency is to provide a fair chance, from the beginning, for an individual to make clear decisions, especially with hand and face transplants.”

— Bilateral hand transplant recipient, written testimony to the committee

“I don’t have any regrets of getting the hands. I just wish I had more information so I could have prepared myself mentally because losing my independence, as well as losing my limbs, that was traumatizing on their own, and then going through these new battles post hand transplantation … the kidney failing and so forth. It’s a lot. It’s a lot for one person to handle.”

— Bilateral hand transplant recipient, presented testimony to the committee at the March 22, 2024, public webinar

Because of the complexity and uncertainty of many treatments, and because most treatments contain both risks and benefits, preference-sensitive treatments like VCA (e.g., where there are multiple options for treatment, often without a scientifically proven “best” option) are ideally accomplished within the context of shared decision making. Shared decision making and patient-centered communication are indicators of high-quality, value-based health care (see Chapter 3) and are the gold standard for decision making in clinical care (Clayton et al., 2007; Gilligan et al., 2017; Street et al., 2016). Shared decision making increases patients’ satisfaction with their care and may positively influence treatment adherence (Shay and Lafata, 2015). Although health care providers are experts on medical information, patients are the experts about themselves and their values, goals, and preferences. Providing a forum where all this information flows both ways between patient and the clinician team is integral to shared decision

BOX 4-3

Common Indications, Contraindications, and Relative Contraindications for Hand Transplant

Indications

- Unilateral or bilateral limb loss1

- Significant quality-of-life burden/presence of functional impairments

- Greater than 6 months since extremity injury, with attempt at rehabilitation

- Previous trial with prostheses (many hand transplant programs consider hand transplants for patients only if they have been fit and attempted to function with conventional prosthetics)

- Motivation to proceed with transplant

Contraindications

- Inadequate social support

- Significant or untreated systemic diseases, multiple impairments, and/or coexisting medical conditions (e.g., active malignancy, chronic infections)

- Current pregnancy

- Severe, active, or poorly controlled psychiatric disorders that are likely to decompensate or affect the ability to recover, participate in therapy, or comply with medication regimen

Relative contraindications

- History of certain malignancies

- Technical and anatomic issues risking successful operative outcomes

- Highly sensitized patients

- History of poor medical adherence

- Immune system condition (e.g., immunocompromised)

__________________

1 Some transplant centers protocols may include bilateral amputation only, rather than both bilateral and unilateral as a patient inclusion factor. The arguments for this perspective are based on risk–benefit analyses and greater expected functional and quality-of-life improvement for bilateral amputees since unilateral amputees could compensate the functional deficit either with prosthesis or with the contralateral limb (Hautz et al., 2011; Lúcio and Horta, 2020). Mathes et al. (2009) examined attitudes surrounding hand transplant by clinicians who treat complex hand injuries and found that hand transplant as a treatment for bilateral amputees is more accepted compared to hand transplant as a treatment option for unilateral amputees.

SOURCE: Summarized by committee from published literature and expert opinion. Adapted from Alolabi et al., 2017; Hartzell et al., 2011; MacKay et al., 2014; Mendenhall et al., 2018b.

making. Research also emphasizes a need for both the relational elements (emotion and tone) and the instrumental elements (information exchange) of communication (Bomhof-Roordink et al., 2019; Siminoff and Step, 2005; Traino and Siminoff, 2016). This is not a linear process, as patient interest in transplantation may change throughout the evaluation and assessment process.

A key component in achieving positive outcomes and the sustainability of the allograft over time is thoughtful and realistic decision making, shared between patient and clinical team (Boehmer et al., 2023). Shared decision making may be viewed as an open exchange of information among patient, caregiver, and clinical team with an emphasis on patient choice. These discussions often include disclosed risks, alternative treatments, and lifestyle advice (Herrington and Parker, 2019) (see Chapter 3 for more on shared decision making).

Setting appropriate expectations preoperatively is critical for patient satisfaction and to ensure informed decision making. Additionally, expectations can also affect outcomes—a study that examined psychosocial data submitted to the IRHCTT from 1998 to 2016 found that expectations for posttransplant function were associated with postsurgical transplant status (Kinsley et al., 2020). Allograft loss occurred in 6 percent of patients who had “realistic expectations” compared to 33 percent of patients who had “unrealistic expectations” (Kinsley et al., 2020), though the numbers were small (2/34 and 3/9, respectively). Another study found that for some limb loss patients, financial burden and lack of insurance coverage was a major concern when considering VCA (Finnie et al., 2022). The study also found that clear communication early in the evaluation process about financial burdens and what insurance will and will not cover is an important part of the shared decision-making process. It has been suggested that developing an “open-ended” perspective may help hand transplantation patients form appropriate expectations regarding outcomes following VCA (Herrington and Parker, 2019). An open-ended perspective emphasizes the message of flexible goals that may evolve and help to set a realistic picture of posttransplant life.

Unlike solid organ transplantation, the OPTN VCA committee13 has not developed guidelines clarifying what information must be disclosed to VCA candidates to ensure they can make informed decisions about their treatment. Thus, the information about the procedure that is provided to VCA candidates varies by transplant program. A review of protocols from various VCA centers revealed that patient education was not robustly explored in all of the protocols. Such variation may contribute to transplant

___________________

13 See https://optn.transplant.hrsa.gov/about/committees/vascularized-composite-allograft-transplantation-committee/ (accessed September 30, 2024).

candidates being inadequately informed and underprepared, leading them, in some cases, to feel unduly pressured when considering VCA as an option (Vanterpool et al., 2023). Multiple health care professionals care for VCA recipients, and a comprehensive plan for patient and caregiver education is a necessary best practice.

The Ottawa Decision Support Framework conceptualizes the support needed by patients, families, and clinicians for “difficult” decisions with multiple options (Ottawa Hospital, 2022; Stacey et al., 2020). The Ottawa Hospital also developed general decision aids based on their four-step framework: (1) clarify the decision (e.g., the reasons for making this decision, when must the decision be made by), (2) explore the decision (e.g., listing out options, risks, and benefits, identifying people who provide social support and how they will be involved), (3) identify decision-making needs (e.g., knowledge, values, support, certainty), and (4) plan next steps based on the decision-making needs (Ottawa Hospital, 2024). These decision guides, and other frameworks, may be helpful for standardizing the shared decision-making process in face and hand transplantation across VCA transplant centers.

A study using interviews conducted with upper extremity amputees, VCA candidates, and upper extremity transplant recipients was designed to qualitatively assess the decision-making and informed-consent processes for upper extremity transplantations, including developing and evaluating patient-centered educational materials (Gordon et al., 2023). Interviewees said that the timing of information disclosure had an impact on their decision-making process and that they would like to be aware of information as soon as possible. Information about the procedure is typically provided verbally or as pamphlets with follow-up emails. However, participants disliked the paper packets, reporting that they sometimes had difficulty turning the pages and that the amount of information was overwhelming and adding that it was preferable for information to be relayed in a digital format with smaller, easily digestible sections (Gordon et al., 2023). Another study among upper extremity amputees considering hand transplantation identified a strong desire to know and understand the comprehensive VCA experience. This included information about the pretransplant experience, such as time on the waiting list, the psychosocial evaluation process, and how closely the donor arm will match the patient’s characteristics (Gacki-Smith et al., 2022). Additionally, potential patients were interested in surgical aspects, such as the likely number of revision surgeries, hospital stays, and recovery timelines. Posttransplantation considerations included medication side effects, rehabilitation protocols, and the degree to which a transplantation would restore functionality (Gacki-Smith et al., 2022).

The website Within Reach was developed for people with upper limb amputations to explore VCA as a possible option (Within Reach, n.d.-a).

Additional resources to use during the shared decision-making process are 3-D printed models and computerized models, which can help patients have appropriate expectations regarding size variations of the allograft (Momeni et al., 2016). Education to support the ability of caregivers to guide the mental health and social interventions is also critical to optimize recovery and rehabilitation. Suggested informational elements for a comprehensive patient and caregiver education program for face and hand transplantation are listed in Table 4-1.

Using a culturally sensitive approach during the shared decision-making process supports the engagement of patients with their health care team

| Necessary Knowledge for Shared Decision Making | Education Delivery Mechanisms | Individual Patient Considerations |

|---|---|---|

|

|

|

(Hawley and Morris, 2017). For example, it may be necessary to engage with a professional translator if the patient or caregivers speak a different language than the health care team. Additionally, cultural beliefs about the appropriateness of certain treatments can influence patient preferences. Currently, trainings and interventions to educate clinicians on cultural competencies are not widely used, which may exacerbate health disparities (Gordon et al., 2020).

In addition to patient education programs, VCA caregivers need to learn what is required of them to support a face or hand transplantation patient. Historically, support of any kind pretransplantation is focused on the patient, which can lead to caregivers feeling isolated and stressed.14 Due to the lack of educational programs for caregivers of organ transplantation patients, the American Society of Transplantation created an Organ Transplant Caregiver Toolkit.15 This toolkit was developed using caregiver input to provide a comprehensive understanding of the responsibilities of a caregiver (Bruschwein et al., 2024). The toolkit discusses caregiver roles and responsibilities, legal and financial considerations, caregiver QoL and self-care, special considerations when caregiving, relationship dynamics between patients and caregivers, and organ-specific caregiving. There is currently no guide or education program specifically about VCA caregiving. Prospective VCA caregivers have expressed a desire to speak with caregivers who have had experience with a face or hand transplantation patient as part of the pretransplant education process (Herrington and Parker, 2019).

Decision to Proceed with Transplantation

“I always said that if I had one real hand, I would be able to do more for myself. Essentially, the decision for me was quite easy.”

— Bilateral hand transplant recipient, written testimony to the committee

[On why she pursued a double hand transplant:] “My goals were to regain my independence, to get my sensation back, and one day to become a mother and then hold my baby in my arms.”

— Bilateral hand transplant recipient, presented testimony to the committee at the March 22, 2024, public webinar-

___________________

14 Based on lived experience consultant testimony.

15 See https://www.myast.org/caregiver-toolkit (accessed September 30, 2024).

“I would almost say that [shared decision making] has to be the number one thing going into VCA because it’s not just that you say yes to this procedure. … [Y]ou become part of a team that you’re grafted to, for lack of a better word, for the rest of your life.”

— Bilateral hand transplant recipient, presented testimony during lived experience focus group session

“Talking with someone who’s been through it, I think would be hugely important during the decision-making process.”

— Bilateral hand transplant recipient, presented testimony during lived experience focus group session

Following the evaluation and assessment process, the candidate, together with their support system, then makes the decision whether to proceed with the transplant and be placed on a waiting list for a face or hand. In order for a patient to give consent for the procedure to take place, it is necessary by law for the patient—or guardian in the case of a pediatric patient—to be competent (Scholten et al., 2021). As discussed previously, this decision is ideally reached through a shared decision-making process that includes the patient, his or her caregivers, and the health care team. This process can vary greatly depending on the patient.

In the case of upper extremity loss, a hand or upper limb transplant may not be an appropriate or the preferred treatment option for every person who seeks it. Some patients may have better outcomes with a prosthesis after undergoing a surgical revision or novel reconstructions (e.g., targeted muscle reinnervation, osseointegration) to improve the prosthetic fit and function. Others may do better by adapting to life without an arm and not receiving additional treatment. For patients with facial disfigurement, an alternative to face transplantation is additional facial reconstruction, in which tissues from the person’s body are used to rebuild facial structures.

There is little evidence about the process by which patients, caregivers, and health care teams come to a decision whether to pursue a face or hand transplant. However, studies have identified three classes of factors that affect that decision-making process (Boehmer et al., 2023; Finnie et al., 2022; Gordon et al., 2023; Talbot et al., 2019). Pull factors, which increase the likelihood of going forward with a transplant, include dissatisfaction with current treatment plans; the desire to regain or improve function; improvement of appearance, self-image, and identity; renewed social integration and family interaction; and regained independence. Push factors,

which weigh against proceeding with a transplant, include concerns about jeopardizing one’s current health, being satisfied with the current treatment option, committing to rehabilitation, managing logistical burdens, interrupting family and work life, handling financial burden, and a belief that there is a need for more research in VCA (Finnie et al., 2022; Gordon et al., 2023; Talbot et al., 2019). External factors also affect the decision to pursue a transplant, including influences from family, culture, and the medical field as well as the time since the injury occurred.

The above-mentioned functional and psychosocial benefits of VCA (the pull factors) have to be weighed against the commitments and risks (the push factors) that accompany receiving a transplanted face or upper limb. The latter are the physical, mental, and emotional demands on the patient from the psychosocial adjustment process, and the serious health risks of taking immunosuppressant drugs for life (Herrington and Parker, 2019), in addition to the rigorous rehabilitative process. Since VCA is not considered lifesaving and since alternative treatments exist that avoid the risks of immunosuppressive medications, the risk–benefit ratio is a major consideration as patients make their decision whether to proceed with transplantation (Snyder et al., 2021), which is often dependent on the patient’s and family’s values, preferences, and goals.

Patients considering VCA are making a transformative medical decision that radically alters a person’s lived experience. Imagining what a transplant will be like and what it will represent in terms of a change to the life course of a person and the person’s family is a process requiring proper assessment and consideration. Meaningful decision making includes understanding the short- and long-term consequences of a surgical procedure of potentially high gain but also high risk, including in the physical, emotional, psychological, and financial realms. This decision is complicated by the lack of generalizable data and consensus within VCA, one in which multiple unknowns still affect the evaluation of risk. Patients and caregivers have to decide whether a face or hand transplant will be affordable for their family and whether the risks will be worth the potential psychosocial and functional benefits (Herrington and Parker, 2019).

Waiting List and Donor Matching

[After receiving a call about a possible donor:] “I told my son, he was 9 at the time, what was happening, and he said, ‘So we’re going to be able to play catch again?’ … [O]n Father’s Day of 2019, I received the hand. So, what a gift!”

— Hand transplant recipient, presented testimony to the committee at the March 22, 2024, public webinar

Once the candidate has been approved for and has decided to proceed with the transplant, the candidate is placed on the OPTN waiting list. The OPTN uses an electronic database to track patients waiting for a VCA.16 Wait times for a transplant vary between less than 6 months to over 3 years, depending on the number of VCA donors and finding a donor match for the recipient (Wainright et al., 2018). The number of candidates for VCA is much smaller than the number of people waiting for solid organ transplants. As of November 14, 2024, there were two patients on the waiting list for a face transplant and three patients on the waiting list for a hand transplant compared to 9,549 and 97,565 patients on the waiting list for liver or kidney transplant, respectively (OPTN, 2024). These patients waiting for a face or hand transplant have been on the waiting list for 90 days to greater than 6 months.

Before the Final Rule was promulgated in 2014 (see Chapter 2), VCA procurement was performed in direct coordination with the organ procurement organization (OPO). When OPTN oversight of VCAs began, VCA allocation and data collection for VCAs was initially conducted using a parallel process to UNet17—“an electronic network comprised of multiple systems, designed to link transplant hospitals, OPOs, and histocompatibility laboratories on one platform…due to the novelty of the field and programming time constraints.”18 In 2020 the OPTN VCA committee recommended programming VCA allocation and data collection in UNet, which was implemented in 2023 (UNOS, 2023).

Matching the Recipient and Donor

For face and hand transplants, the matching of a donor and a recipient is done with factors similar to those used for solid organ transplants, such as similar blood types, viral screening, and human leukocyte antigen (HLA) protocols, although this varies by transplant center and country (Kay and Leonard, 2023; La Padula et al., 2022). Special considerations for VCA donor selection include matching sex, age, and skin color to the recipient. Ethnicity, height, bone size, and weight are considered on an individual basis by some centers. Distance between the procurement and the transplant centers is also a factor. Currently, the number of potential VCA donors is not a limiting factor, as a significant portion of the solid organ

___________________

16 See https://www.nationalacademies.org/event/42240_04-2024_principles-and-framework-to-guide-the-development-of-protocols-and-standard-operating-procedures-for-face-and-hand-transplants-webinar-2 (accessed September 16, 2024).

17 See https://unos.org/technology/unet/ (accessed May 27, 2020).

18 Briefing to the OPTN Board of Directors on Programming VCA Allocation in UNet. See https://optn.transplant.hrsa.gov/media/ummpuvbz/bp_202012_programming-vca-allocation-in-unet.pdf (accessed November 18, 2024).

donor pool would quality to be a VCA donor (Mendenhall et al., 2018a), though the phenotypic matching criteria may increase the time needed to find a suitable donor.

Prehabilitation and Psychosocial Support

While patients await their transplant, it is valuable to commence prehabilitation-based lifestyle changes and preparation for life with a transplant (Quint et al., 2023). Prehabilitation is used across many types of surgical specialties to promote positive clinical outcomes and improved patient QoL post surgery. Prehabilitation focuses on optimizing exercise, nutrition, education, psychosocial support, and stress management counseling (Santa Mina et al., 2015). Among kidney transplant patients, those who participated in prehabilitation (e.g., endurance and strength training) had shorter hospital stays post transplant than those who did not engage in prehabilitation (Quint et al., 2023). While there has not been extensive research on the impact of prehabilitation on face and hand transplantation patients, prehabilitation may produce positive outcomes similar to the benefits seen in solid organ transplantation. For example, in upper extremity transplantation patients it may be beneficial to strengthen the shoulder, limb, and other muscles throughout the body to prepare the patient for the weight of the allograft.

Psychosocial support is also key to patient recovery and important during the pretransplant period (Brill et al., 2006). Psychosocial support interventions can include the assessment of coping strategies, support network preparedness, and psychosocial counseling (Brill et al., 2006; Nizzi and Pomahac, 2022).

Data Limitations and Additional Research Needed Related on the Preoperative Phase of the Transplant Experience

There are evidence gaps related to the preoperative phase of the transplant experience that limited the committee’s findings and suggested areas for future research and action. As with the solid organ transplantation system, for VCA there is no mandatory requirement to report data from the pre-transplant experience. A report from the National Academies on reforming the organ transplantation system recommended, as part of the OPTN Transplant Program Performance Monitoring Enhancement project (OPTN, n.d.), that additional performance metrics be added concerning the preoperative phase of the transplant experience (NASEM, 2022b). The recommended metrics included the number of patients referred to each transplant center for evaluation, the number of referred patients who were

evaluated, and the number of evaluated patients who were listed. There is also insufficient evidence on referral sources or awareness of VCA by those that may benefit from the procedures. A two-step Delphi study focused on face transplant concluded that research related to patient inclusion and exclusion criteria, including the investigation of predictive factors of success, is also needed (Longo et al., 2024). The same study also concluded that further research regarding the assessment and evaluation of patient support systems may benefit the pretransplant phase (Longo et al., 2024).

CHAPTER 4 KEY FINDINGS

The face and hand transplantation experience begins well before the transplant surgery and continues for the rest of the lives of both the recipient and their caregivers. This experience includes the initial condition; becoming aware of VCA as one treatment option; referral to a transplant center; the evaluation and assessment process; the decision whether to proceed with transplant; time spent on the waiting list; the surgical procedures; postsurgical management, including immunosuppression, rehabilitation, and psychosocial support; and the long-term care management and assessment of patient outcomes. Indications for face and hand transplant are based on the failure of conventional treatments to address a patient’s limitations, the expected success of the transplantation, and the impact on function and QoL for the patient. People considering a face transplant often have physical challenges, such as problems with eating, speaking, breathing, and using facial expressions, and psychological challenges such as PTSD. Those considering hand transplantation have had single or bilateral upper limb amputation, which can disrupt QoL, limit function, cause psychological distress, decrease social interactions, and limit participation in society. Overall, there is little evidence about the process by which patients and health care teams come to a decision on whether to pursue face or hand transplant, but studies have found that a multitude of factors (pull, push, and outside factors) affect the patient decision-making process for pursuing a transplant.

During the pretransplant assessment process, shared decision making is an essential component of the VCA experience and begins when patients present with interest in being considered for VCA. It is integral to many of the preoperative decision-making steps and, postoperatively, as part of the care management needed to care for and maintain the VCA. Setting appropriate expectations preoperatively is critical for patient satisfaction and to ensure informed decision making. The educational information provided to patients varies by transplant center. A caregiver can offer support for the decision-making process as well as the rest of the transplant experience. To prepare for their role, caregivers have demonstrated interest in additional

training, education, and support. There is no general, comprehensive education program for VCA caregivers, and, like patient education programs, the information provided to caregivers varies by transplant center.