Advancing Face and Hand Transplantation: Principles and Framework for Developing Standardized Protocols (2025)

Chapter: 2 VCA Background Information and Context

2

VCA Background Information and Context

Vascularized composite allotransplantation (VCA) replaces, in the recipient, vital tissue that has been severely damaged, rendered nonfunctional, or lost. VCA is intended to restore independence and a degree of normalcy for individuals who are currently underserved by alternative treatment options, such as reconstructive surgery or the use of a prostheses. Multiple forms of VCA are described in this chapter, but this report focuses on face and hand transplantation. The first successful hand transplant was performed in 1998 in Lyon, France, and the first hand transplant in the United States was performed in 1999 in Louisville, Kentucky (Errico et al., 2012). The first successful face transplant took place in 2005 in Amiens, France, and the first face transplant in the United States was performed in 2008 in Cleveland, Ohio (Diep et al., 2021).

VCA: DEFINITION AND BACKGROUND

VCA involves the transplantation of a vascularized body part that contains multiple tissue types, including skin, fat, muscle, bone, nerves, and blood vessels (Rahmel, 2014). On July 3, 2014, the Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network (OPTN) Final Rule (42 CFR part 121)

was amended to add VCAs under the definition of an “organ,”1 giving the OPTN oversight over VCA recovery, allocation, and transplantation. Box 2-1 contains the official OPTN definition of VCA. The nine criteria that constitute the OPTN definition of VCA account for the variation in specific types of VCA (Glazier, 2016).

BOX 2-1

Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network (OPTN) Definition of Vascularized Composite Allotransplantation (VCA)

The OPTN defines VCA as a transplant involving any body parts that meet all nine of the following criteria:

- That is vascularized and requires blood flow by surgical connection of blood vessels to function after transplantation.

- Containing multiple tissue types.

- Recovered from a human donor as an anatomical/structural unit.

- Transplanted into a human recipient as an anatomical/structural unit.

- Minimally manipulated (i.e., processing that does not alter the original relevant characteristics of the organ relating to the organ’s utility for reconstruction, repair, or replacement).

- For homologous use (the replacement or supplementation of a recipient’s organ with an organ that performs the same basic function or functions in the recipient as in the donor).

- Not combined with another article such as a device.

- Susceptible to ischemia and, therefore, only stored temporarily and not cryopreserved.

- Susceptible to allograft rejection, generally requiring immunosuppression that may increase infectious disease risk to the recipient.

SOURCE: OPTN, 2020c.

The OPTN considers eight categories of body parts under its VCA policy (see Box 2-2).

___________________

1 Per U.S. Government Printing Office, Electronic Code of Federal Regulations, 42 CFR part §121.2, August 14, 2014, http://www.ecfr.gov/cgi-bin/text-idx?c=ecfr&tpl=/ecfrbrowse/Title42/42cfr121_main_02.tpl. (accessed December 31, 2024), the designation to add VCAs under the definition of an organ was published on July 3, 2013, but did not take effect until July 3, 2014.

BOX 2-2

Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network (OPTN) Body Parts Included as Vascularized Composite Allotransplantations (VCAs)

The OPTN considers the following body parts as VCAs:

- Upper limb (including, but not limited to, any group of body parts from the upper limb or radial forearm flap)

- Head and neck (including, but not limited to, face including underlying skeleton and muscle, larynx, parathyroid gland, scalp, trachea, or thyroid)

- Abdominal wall (including, but not limited to, symphysis pubis or other vascularized skeletal elements of the pelvis)

- Genitourinary organs (including, but not limited to, uterus, internal/external male and female genitalia, or urinary bladder)

- Glands (including, but not limited to adrenal or thymus)

- Lower limb (including, but not limited to, pelvic structures that are attached to the lower limb and transplanted intact, gluteal region, vascularized bone transfers from the lower extremity, anterior lateral thigh flaps, or toe transfers)

- Musculoskeletal composite graft segment (including, but not limited to, latissimus dorsi, spine axis, or any other vascularized muscle, bone, nerve, or skin flap)

- Spleen

SOURCE: OPTN, 2020c.

VCA Data Collection

“If you want to be a part of the organ transplant system and be an OPTN member, you must actually collect these data”

— Dr. Ryutaro Hirose, Scientific Registry of Transplant Recipients, presented testimony to the committee at the May 29, 2024, public webinar

All centers that perform organ transplantation are required to submit a variety of data, including patient demographics, wait times for a donor organ, donor authorization requirements, blood types, and clinical outcomes, with the goals of improving patient outcomes and promoting safety

(Lewis and Cendales, 2021). Prior to the amendment of the OPTN Final Rule, there was no systematic, centralized VCA data collection in the United States (HRSA, 2014). Recognizing the need to collect data on these transplants, the OPTN released a proposal following the Final Rule amendment that would update OPTN data submission requirements. These specified the data elements to be collected on VCA recipients at transplantation and follow-up; required that member transplantation centers are responsible for submitting VCA candidate, recipient, and donor data; and specified the time period within which VCA candidate, recipient, and donor data must be submitted to the OPTN (HRSA, 2014). 2 OPTN data submission requirements for VCA recipients were implemented in September 2015 (OPTN, 2020d), retroactive to July 3, 2014, when VCA was included in the Final Rule. VCA data submission requirements were updated most recently in 2020 (OPTN, 2020b) to capture “more relevant transplant outcome data elements” for VCA recipients (OPTN, 2020a), including the SF-12 or SF-36.

Much of the U.S. data in the following sections are based on the mandatory data submissions collected from the OPTN, published most recently in the OPTN/SRTR 2022 Annual Data Report: VCA (Hernandez et al., 2024). Three functional metrics are included in the OPTN database for hand transplant recipients: quantitative evaluation of upper extremity function (the Carroll test)3; Disability of Arm, Shoulder and Hand (DASH) score4; and the Semmes-Weinstein test,5 which evaluates sensory recovery (Hernandez et al., 2022). Functional outcomes assessed in face transplant recipients include decannulation of a tracheostomy to regain sense of smell, removal of a feeding tube, and ability to close the eye(s) (Hernandez et al., 2022) (see Chapter 6 for more information on outcome metrics).

The international data in this chapter are primarily self-reported data submitted and provided to the committee by the International Registry on Hand Composite Tissue Transplantation (IRHCTT) (IRHCTT, n.d.), through published reports of the IRHCTT, and other published sources. The IRHCTT was created in 2002 with support from the International Society of Vascularized Composite Allotransplantation. In 2002 there had been approximately 10 hand transplants performed and no successful face transplants. The registry enabled the few active centers to share information

___________________

2 See https://optn.transplant.hrsa.gov/media/1119/06_vca_data_collection.pdf (accessed December 3, 2024) for data collection and submission requirements for VCAs.

3 The Carroll score assesses hand function on a 0–99 scale where higher numbers denote better function (Carroll, 1965).

4 The DASH score is a well-validated tool in hand surgery, where higher numbers denote worse disability (Hudak et al., 1996).

5 The Semmes-Weinstein test is a clinical assessment of light touch, measuring the patient’s sensation with monofilaments; it is widely used in diabetes research and vascular and hand surgery (Feng et al., 2011).

and data about the procedures, supported other transplant centers that were interested in starting a VCA program, and contributed to the growing acceptance that upper extremity transplants were viable treatments with positive allograft survival rates.6 While the registry is voluntary, the registration form asks for a variety of data from transplant centers, including recipient and donor characteristics, principal information about surgical procedures, metabolic, and infectious complications, rejection episodes, and patient and allograft survival. Centers are also asked to submit annual forms that track the progress of their patients. The form includes information about complications, chronic and acute rejection, additional surgeries, allograft failure or removal, and functional assessment scores (e.g., DASH) and the Hand Transplantation Score System (HTSS) to evaluate sensibility, motility, ability to perform activities of daily living, and patient satisfaction and well-being. A statistical analysis is performed based on the aggregated anonymous data. Participants in the IRHCTT include nine centers in the United States and 29 centers outside of the United States.7

Data Gaps

While data reported to the OPTN and to the IRHCTT provide important clinical information about transplant recipients, data are missing in some key areas. Currently, the data do not include patient-reported outcomes, such as patient satisfaction as reported on questionnaires (UNet, 2015a,b). There are currently no validated, standardized metrics for capturing subjective measures such as patient satisfaction or other functional and psychosocial outcomes, and these data are not systematically collected across VCA centers, either in the United States or globally (see Chapter 6 for more information about outcome metrics and Chapter 7 for more information about registries).

Basic Statistics on Vascularized Composite Allotransplantations

In addition to face and hand transplants, other types of VCA include uterine, penile, abdominal wall, and larynx.8 Uterine transplants have been the most performed VCA in the United States and are unique among VCA types because the organ can be recovered from a living donor and the transplant is intended to be temporary. Uterine transplant allows those

___________________

6 Personal communication with Palmina Petruzzo, IRHCTT, May 27, 2024.

7 For a list of the centers participating in the IRHCTT, see https://www.handregistry.com/partecipants.php (accessed August 22, 2024).

8 Other VCAs performed in the United States included one scalp transplant and one trachea transplant (OPTN, 2024b).

who are unable to give birth the opportunity to experience pregnancy. A hysterectomy is typically performed after one or more pregnancies to reduce further complications and avoid the need for lifelong immunosuppression (Castellón et al., 2017). The first successful live birth in a person with a transplanted uterus occurred in 2014.

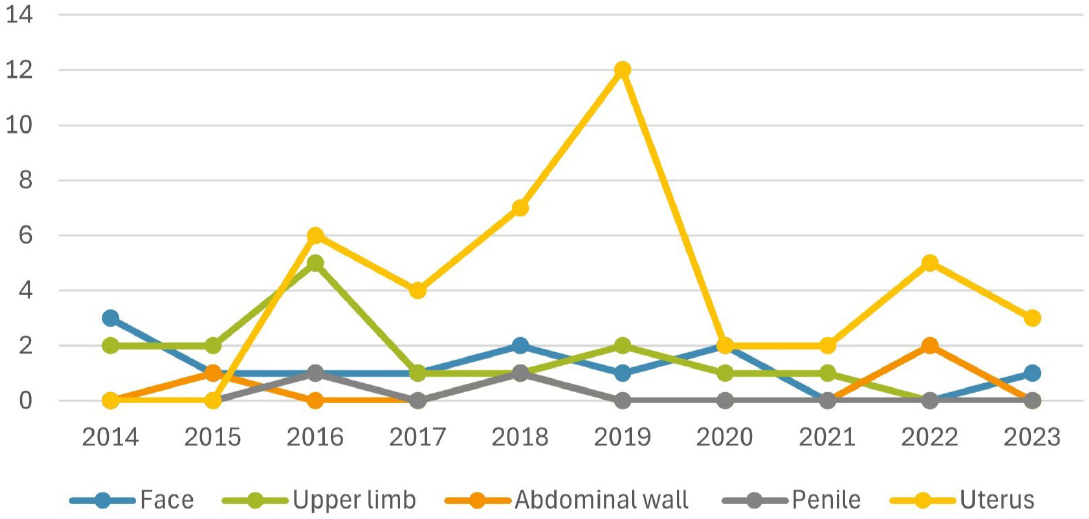

Five penile transplants have been performed worldwide, the first in 2006, and two of them were done in the United States. Two of the five patients eventually had to have the allograft removed. A unique challenge for a penile transplant recipient is the risk of sexually transmitted infections post transplant, which may increase health risks (Lopez et al., 2023). There have been 46 abdominal wall transplants performed in the last 20 years, including 22 in the United States; two of which were eventually removed. As with other forms of VCA, recipients of an abdominal wall transplant have had acute rejection, chronic rejection, and allograft loss. However, research suggests that fewer abdominal wall recipients experience rejection than face and hand transplant recipients (Honeyman et al., 2020). To date, 11 total larynx transplants have been performed, 2 in the United States (Cendelo et al., 2014; OPTN, 2024b). The primary goal of a larynx transplant is to restore breathing, eating, and speaking capabilities (Baudouin et al., 2024; Mayo Clinic, 2024). The number of VCAs performed per year and by type in the last decade in the United States are shown in Figure 2-1. There are orders of magnitude differences in the number of VCAs performed versus solid organ transplants in the United States. For example, there were 25,487 kidney and 10,528 liver transplants performed in 2024, compared with 2 VCA (one face and one hand) (ASRT, n.d.; CNN, 2024; OPTN, 2024b). For deceased donor transplants over the 2008–2024 period, there were an average of 14,682 kidney transplants and 7,478 liver transplants per year, compared with approximately 1 face transplant and 2 hand transplants per year (OPTN, 2024b).

Face Transplants

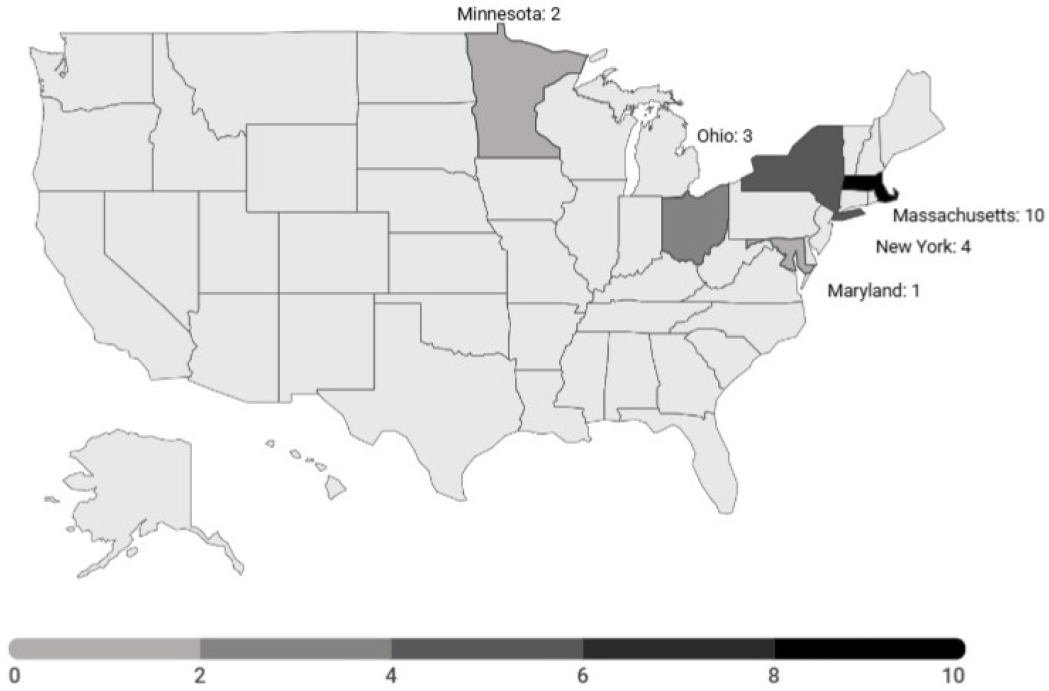

Worldwide, 53 face transplants have been completed as of December 2024 (see Figure 2-2 and Appendix C), with 20 completed in the United States (see Figure 2-3).9 Thirty-three transplants have been performed outside of the United States: 12 transplants in France, 7 in Turkey, 5 in Spain, 2 each in Poland and Finland, and 1 each in Canada, China, Russia, Belgium, and Italy. A team at the Cleveland Clinic in Ohio received the first

___________________

9 The number of face and hand transplants was calculated by recipient who received a transplant. Thus, a bilateral hand transplant is not counted as two transplants. However, a re-transplant is treated as a new transplant and therefore counted as an additional transplant in the total amount, despite the transplant being performed on the same recipient.

SOURCES: Data from CNN, 2024; OPTN, 2024b.

ethical approval for the procedure in 2004, but the first transplant did not occur until 2005 in Amiens, France (Alberti and Hoyle, 2021), leading to proof of concept for the procedure. Internationally, face transplants spiked between 2009 and 2013, including four transplants in France in 2009 and in Turkey there were four in 2012 and three in 2013 (Alberti and Hoyle, 2021). From 2014 through 2022, 32.4 percent of the 34 individuals who underwent a VCA received a face transplant (Hernandez et al., 2024). Face VCA is the third most common VCA in the United States (Hernandez et al., 2024). Since a national waiting list for VCA transplantations was created in 2014, the median time to transplant for face VCA has been 342 days (Hernandez et al., 2024). (See Chapter 4 for discussion about indications for face transplant).

Face Transplant Outcomes

Face transplantation has had positive outcomes in terms of survivability. The 5- and 10- year survival rate among the first 50 face transplantations worldwide was 85 percent and 74 percent, respectively (Homsy et al., 2024). During the follow-up period, 10 patients were deceased, with the causes of death including infection, discontinued immunosuppression, suicide, sepsis, and malignancy. Acute rejection was identified in 46/49 patients (Homsy et al., 2024). Allograft rejection, eventually leading to the removal of the transplantation, was recorded in six patients. Two of those patients received a second transplant (Homsy et al., 2024), one of which was in the United States. All face transplants performed in the United States between 2014 and 2022 have resulted in a functioning allograft (Hernandez et al., 2024) (e.g., allograft was not removed due to medical necessity), 50 percent of patients had their tracheostomy decannulated and regained their sense of smell, 33 percent had their feeding tube removed, and 33 percent regained eye closure ability (Hernandez et al., 2022; Lewis and Cendales, 2021). Additionally, patients have had significant reductions in stress level associated with personal appearance and social integration (Greenfield et al., 2020). Face transplantation has also resulted in positive quality-of-life outcomes, such as decreased distress regarding physical appearance, increased self-confidence, and social integration (Aycart et al., 2017). (See Chapter 6 for more information on outcomes.)

Hand Transplants

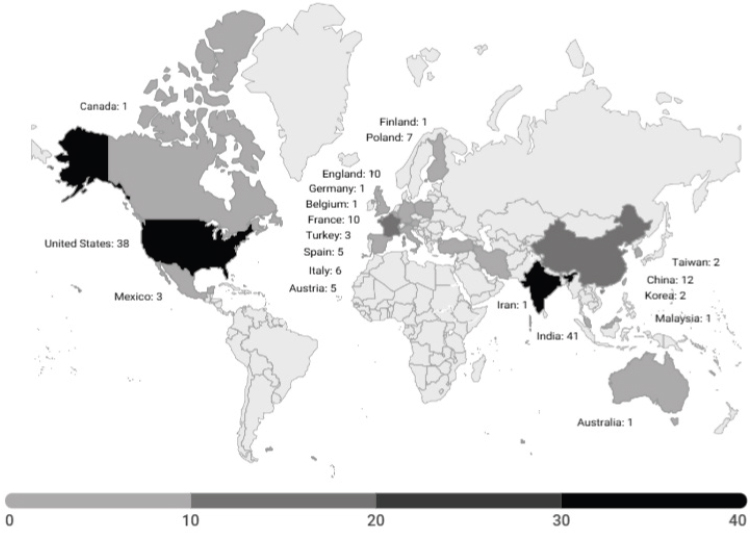

Worldwide, approximately 151 hand transplants have been completed through December 2024 (see Figure 2-4 and Appendix C), with 38

SOURCES: Data from Ahmad et al., 2020; Amaral et al., 2017; Amma, 2022; Amrita Hospital, 2024; Amrita Vishwa Vidyapeetham, 2022; ap7am.com, 2024; Cavadas et al., 2009, 2011; Chang Gung Memorial Hospital, 2022; Clark et al., 2020; Deccan Herald, 2024; Dwyer et al., 2012; The Economic Times, 2022; Eggleton, 2010; Fernandez et al., 2019; France 24, 2009; Furniss et al., 2012; The Guardian, 2008; Gobierno de Mexico, 2016; Hautz et al., 2020; The Hindu, 2018; Hurriyet Daily News, 2016; Iglesias et al., 2016; India Today, 2023, 2024; Indian Transplant Newsletter, 2023; Iyer, 2023; Jablecki et al., 2010; JIPMER Deceased Donor Transplantation Committee, 2020; Kalantar-Hormozi et al., 2013; Kuo et al., 2016; Kvernmo et al., 2005; Lanzetta et al., 2007; Lee et al., 2023; Leonard et al., 2024; OPTN, 2024b; Özkan et al., 2011; Patel et al., 2022; Pei et al., 2012; Petruzzo et al., 2008; Polish Press Agency, 2017; Rosales et al., 2019; Satbhai, 2023; Schuind et al., 2006; Sharma et al., 2023a,b; Shores et al., 2015; Sir Ganga Ram Hospital, 2024; Thompson, 2021; The Times of India, 2023, 2024; Ubelacker, 2016; Woo et al., 2021; Yildiz and Adam, 2020; Zhang et al., 2016.

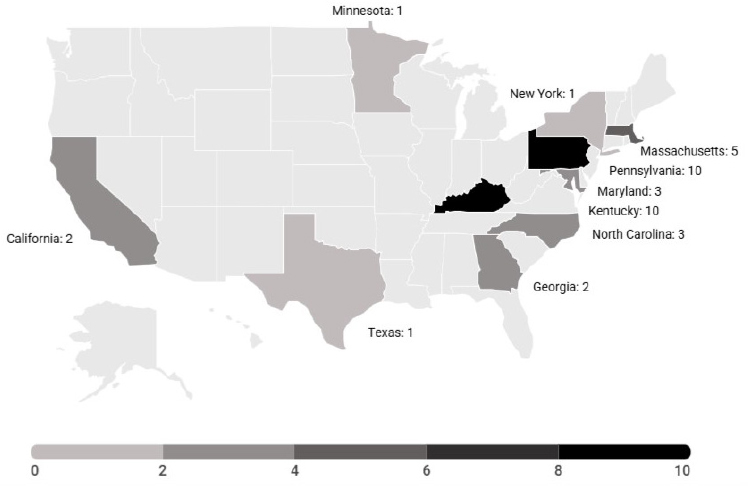

completed in the United States (see Figure 2-5).10 Outside of the United States, 41 hand transplants have been performed in India, 12 in China, 10 in England and France, 7 in Poland, 6 in Italy, 5 each in Spain and Austria, 3 in Turkey and Mexico, 2 in Taiwan and Korea, and 1 each in Canada, Germany, Belgium, Iran, Malaysia, Finland, and Australia. The first hand transplant was performed in Lyon, France in 1998, and in the 5 years following that transplant, 24 additional procedures took place (Alberti and Hoyle, 2021). Between 2014 and 2023, about 40 percent of non-uterus VCA candidates in the United States (23/56) were listed for and received an upper limb, and the most common transplanted non-uterus-VCA was upper limb (approximately 44 percent, 15/34) (Hernandez et al., 2024).

SOURCE: Data from OPTN, 2024b.

___________________

10 The number of face and hand transplants was calculated by recipient who received a transplant. Thus, a bilateral hand transplant is not counted as two transplants. However, a re-transplant is treated as a new transplant and therefore counted as an additional transplant in the total amount, despite the transplant being performed on the same recipient.

Hand Transplant Outcomes

Overall, outcomes of hand transplantations have generally been positive, leading to improvements of quality of life and functioning. A systematic review of hand transplants performed worldwide through 2020 found that hand transplantation led to decreased disability and improved functional outcomes, as measured by DASH scores (Wells et al., 2022). Acute rejection occurred in at least 85 percent of hand transplantations within the first year (Petruzzo et al., 2010). Patients can experience medical complications, including hyperglycemia, diabetes, cytomegalovirus infection, and renal insufficiency. (See Chapter 5 for information on complications.) Globally, 10.8 percent of transplants were eventually removed, typically due to acute and chronic rejection from immunosuppression, and as of 2020 there have been five reported deaths (Wells et al., 2022).

Of upper limb transplants in the United States, 93 percent (14/15) resulted in a functioning allograft (Hernandez et al., 2024) (e.g., allograft was not removed due to medical necessity). Based on data reported to the OPTN between 2014 and 2019, hand VCA recipients showed improvement in their quantitative function scores, DASH scores, and the sensory recovery test after hand transplantation (Hernandez et al., 2022). Standard instruments for following function after upper extremity VCA are evolving but are not universally accepted or used across transplant programs. For example, an analysis of data submitted over a 5-year period following implementation of the Final Rule found that “of the 4 unilateral hand recipients, 1 has reported preoperative and postoperative Carroll test scores, with a postoperative improvement of 48 points. No unilateral hand recipient has paired preoperative and postoperative DASH scores. No unilateral hand transplant recipient has postoperative Semmes-Weinstein tests” (Lewis and Cendales, 2021, p. 294). For bilateral upper extremity transplants over this time period, “[a]mong the 6 bilateral hand transplant recipients, 4 (66 percent) have reported preoperative and postoperative Carroll test scores; the average score improvement was 28 points per patient. Three of the 6 (50 percent) bilateral hand transplant recipients have documented preoperative and postoperative DASH scores in the database; these show an average of 18 points per patient improvement. Semmes-Weinstein tests are reported for 5 of the recipients (83 percent), with an average postop score of 3” (Lewis and Cendales, 2021, p. 292). (See Chapter 6 for more information on outcomes).

U.S. FACE AND HAND TRANSPLANT CENTERS

Due to the technical capabilities needed and the significant institutional burden, face and hand transplants have been performed in only a limited number of programs in the United States, all of which fall under OPTN

approval. Centers in 11 states have performed at least one such transplant since July 3, 2014; nine centers have performed upper limb transplantations; and five centers have performed face transplantations (Hernandez et al., 2024). As of December 2024, there are 10 approved and active sites for head and neck VCA procedures11 and 11 approved and active sites for upper limb transplants12 in the United States (OPTN, 2024c).

To become a certified VCA center, a transplant program must be a member of the OPTN and meet OPTN requirements including minimal certification, training, and experience for individuals serving as primary transplant physicians and surgeons at VCA programs (OPTN, 2020c, 2024a). Furthermore, the OPTN requires that VCA programs have a designated program director, a primary transplant physician, a primary program administrator, and a primary data coordinator. The primary VCA surgeon must meet specific requirements, depending on whether the center wishes to perform face or hand transplant surgery. These include, but are not limited to, holding an M.D., D.O., or equivalent degree; being a practicing physician at the hospital; having acted as the primary surgeon or first assistant on at least one VCA procedure; and having participated in the follow-up care of at least one VCA recipient (HHS, n.d.).13

Certified face and hand transplant centers in the United States are geographically concentrated along the East Coast, with two centers in the Midwest and two on the West Coast. An analysis of 13 face transplantations performed in the United States found that only one recipient lived local to the transplant center (Rifkin et al., 2018). The low geographic availability of qualified centers can increase logistical challenges for transplant recipients following surgery. Face and hand transplants require lifelong immunosuppressant care in addition to at least yearly follow-up, which can lead to financial burdens and a difficult transition to local care teams if they are not as equipped to provide ongoing care. International transplant recipients can encounter similar issues. For example, an international bilateral hand transplant recipient found that her follow-up care in France was far less

___________________

11 OPTN-approved sites include Cedars Sinai Medical Center, Cleveland Clinic, Johns Hopkins Hospital, Mayo Clinic (Arizona), Mayo Clinic (Minnesota), Mount Sinai Medical Center, NYU Langone Health, University of Maryland Medical Center, Vanderbilt University Medical Center, and Yale New Haven Hospital.

12 OPTN-approved sites include Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Cedars Sinai Medical Center, Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, Cleveland Clinic, Duke University Hospital, Emory University,* Johns Hopkins Hospital, Mayo Clinic (Minnesota), NYU Langone Health, University of California, Los Angeles,* University of Illinois Medical Center, University of Louisville Jewish Hospital, University of Pennsylvania, University of Pittsburgh,* and University of Texas, Southwestern.* (* indicates OPTN approved, but inactive sites.)

13 Despite these existing OPTN requirements, the committee believes that there should be additional standards to offer these transplants due to the necessary support and resources required to provide lifelong care to recipients (see Chapter 9 for further discussion).

optimal than her experience in the United States. This led to her traveling back and forth multiple times.14

SELECT POPULATIONS AND VCA

While the total number of VCA patients is small, the following select populations merit additional discussion: military personnel and veterans, pediatric populations, and those from racial and ethnic minority populations.

Usage of VCA Among Active Duty Military Personnel and Veterans

“Do attitudes, opinions, and knowledge of other treatments have an impact on military personnel considering transplant? And that’s a resounding yes.”

– Dr. Scott Tintle, Walter Reed National Military Medical Center, presented testimony to the committee at the April 17, 2024, public webinar

U.S. military personnel are a distinct population from most civilians. These men and women are typically young, active, and adventuresome. For those who return from combat with injuries, it is that adventuresome spirit that propels most of them to get back to the lives they want to lead, and despite their injuries, they adapt and prosper. As of 2020, five retired U.S. military personnel, along with four service members from other countries, have received VCAs following combat or combat-training injuries (Fries et al., 2020). Of these, seven were hand and limb transplants (four were bilateral), one was a face transplant, and one was a transplantation of lower limbs, abdomen, and genitalia. The first VCA performed on a wounded soldier was in 1964 in Ecuador shortly following a blast injury (Fernandez et al., 2019). Immunosuppressants at that time were primitive, so the allograft was rapidly rejected and was re-amputated 21 days later. The other eight VCAs were performed between 2009 and 2018.

Deciding to pursue VCA is a complicated decision with considerable risks and benefits. While military VCA candidates may be well suited to undergo VCA, they have expressed concerned with recovery times, side effects from immunosuppression, and rejection (Siminoff et al., 2022). Based on the testimony of a representative from the Walter Reed National

___________________

14 Testimony from information-gathering webinar on March 22, 2024.

Military Medical Center at an information-gathering webinar, veterans with limb amputations may be reluctant to pursue VCA because the risks from lifelong immunosuppression medications and the required changes in lifestyle outweigh the benefits.15 While service members appear to be good candidates, face or hand transplantations, like solid organ transplantations, are automatically disqualifying factors for military deployment. Organ or tissue transplantations that require long-term immunosuppression are disqualifying conditions for military service (DoD, 2020). Additionally, an active duty service member may have a difficult time participating in the multiyear rehabilitation programs required following VCA while also serving in the military (Within Reach, 2022). To date, no face or hand transplant has been performed on an active duty service member.16 In 2009, the U.S. Army Surgeon General established the Face Transplantation Advisory Board (Hale, 2011), which helped distribute face transplant clinical trial information to Army medical providers to help raise awareness of face transplant as a treatment option (Hale, 2011).

Active duty service members who are pursuing VCA can initiate a waiver process that, if approved by the Surgeon General’s office, will enable Tricare to cover a portion of the VCA costs (Dean and Randolph, 2015). The U.S. Veterans Health Administration (VHA) does not guarantee that costs for preoperative, surgical, or immediate postoperative VCA procedures and care will be eligible for coverage. Those are currently funded through hospital funds and research grants. The VHA does, however, provide long-term coverage for immunosuppressive medications and services like physical and speech therapy that are intended to maintain the health of the transplant and recipient (Dean and Randolph, 2015). (See Chapter 3 for more information on financial considerations.)

Pediatric Populations

In 2015, the world’s first pediatric bilateral hand transplantation was performed on an 8-year-old child. A composite neck transplantation was performed on a child in Poland in 2019 (Azoury et al., 2020). In total, there have been approximately 15 pediatric VCA transplantations worldwide, 11 of which have been performed in the United States (one bilateral arm and 10 abdominal wall) (Azoury et al., 2020; Deccan Herald, 2024; Hamilton

___________________

15 Presented by Scott Tintle, Walter Reed National Military Medical Center, at a public information-gathering webinar. See https://www.nationalacademies.org/event/42240_04-2024_principles-and-framework-to-guide-the-development-of-protocols-and-standard-operating-procedures-for-face-and-hand-transplants-webinar-2 (accessed September 9, 2024).

16 Ibid.

et al., 2015; Lanzetta, 2017; OPTN, 2024b). Challenges related to pediatric transplants include issues related to growth, extended lifelong immunosuppression and its increased health risks, and compliance with immunosuppression regimens during adolescence (Doumit et al., 2014), as well as the consent process for a minor. In the case of the first pediatric bilateral hand transplantation, some of these challenges were overcome due to the fact that the patient had previously received a kidney transplant. Therefore, the ability to adhere with posttransplant immunosuppressive therapy and rehabilitation was previously demonstrated (Snyder et al., 2019).

The ethics of pediatric transplantation are particularly challenging. Who will advocate for the pediatric patient? How are patient selection and care planning for children afflicted with congenital differences or early limb loss due to sepsis or trauma considered? While pediatric donor pools are recognized for solid organ transplantation, donor availability for pediatric hand transplant can be limited. For the pediatric VCA patient, there are generally between 11 and 112 potential pediatric donors per OPTN region (Mendenhall et al., 2019). Acquiring permission for pediatric transplant from a donor family is particularly challenging, given the circumstance of pediatric death from any cause. Other challenges include the expertise of a team to perform this type of transplant. Pediatric hand and microvascular expertise are essential for pediatric hand transplantation, and assembling a complete team can only be done in select pediatric hospitals.

Racial and Ethnic Considerations

“As a result of being the first Black man [in the United States] to have a face transplant … the data that they collected was based on one culture. As a result of that, they weren’t looking [for] external signs of rejection.”

—Testimony from a face transplant recipient at the March 22, 2024, public webinar

Within the U.S.-based data, the exact racial/ethnic profiles of transplant recipients are unclear as many recipients are reported as “unknown” (OPTN, 2024b). Among upper limb recipients in the United States, 13 were reported as White, 2 Black, 1 as Hispanic, and 22 were listed as unknown race or ethnicity. Of the data reported to the OPTN, VCA recipients are more likely to be White than Black or Hispanic: among non-uterus transplant recipients, 71.4 percent were White, 16.1 percent were Hispanic, 10.7 percent were Black, and 1.8 percent were Asian, American Indian/Alaska Native, Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander, and/or multiracial (Hernandez et

al., 2024). There has been little research about the factors contributing to potential racial and ethnic disparities in VCA, such as the role of multilevel factors and social determinants of health (Kumnig et al., 2022). However, the committee notes that many of these factors may be similar to those that impact disparities in health care delivery and outcomes, including in solid organ transplantation system (NASEM, 2022).

THE ORGAN DONATION SYSTEM AND VCA

Since the Final Rule amendment, faces and hands have been considered donatable organs under OPTN policy (Parent, 2014), and all non-uterus VCA transplant recipients have received organs from deceased donors (Hernandez et al., 2022). The availability of VCAs to treat individuals with severe disfiguring injuries relies, in part, on the decision making of families approached to donate a VCA organ—a gift that makes transplant possible. Public trust is critical for organ donation and transplantation in the United States, and transparency is essential in shaping public beliefs and attitudes about the trustworthiness of the organ transplantation system (NASEM, 2017, 2022).

U.S. Organ Transplantation System and OPTN Oversight

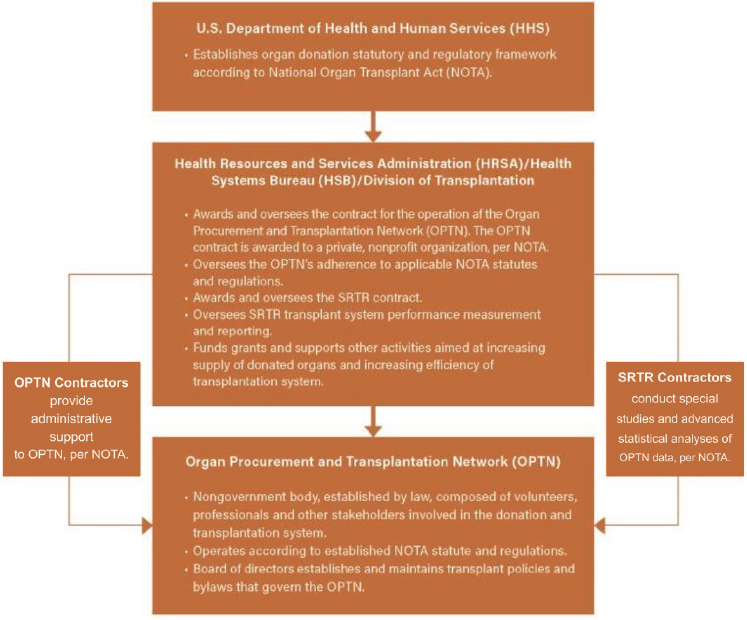

Federal standards emerged in 1984 with the enactment of the National Organ Transplant Act (NOTA), the formation of the United Network for Organ Sharing (UNOS), and other measures that addressed broader ethical and legal questions. Since then, strict federal rules have governed American transplantation. The current organ transplantation system in the United States is a complex web, involving multiple entities navigating in various aspects of creating, shaping, and implementing policies, gathering data, and providing oversight (NASEM, 2022). This web includes multiple agencies within the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), including the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA), the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the Food and Drug Administration, and the National Institutes of Health. In addition, NOTA created the OPTN as an independent entity that provides crucial empirical data related to organ donors and recipients, allowing for the tracking of both groups by age, sex, and race, cross-referenced by organ type. Furthermore, HRSA has historically maintained two contracts, for the OPTN and the Scientific Registry of Transplant Recipients (SRTR), to support the U.S. transplantation system (see Figure 2-6). The OPTN develops policies to implement an equitable system of organ allocation, maintains the waiting list of potential recipients, and compiles data from U.S. transplant centers. Policy directives and changes

for traditional organ transplantation are typically put in place for VCA as well. For example, under the OPTN, VCA programs (just as with traditional transplantation centers) must meet specific requirements, including “(1) quality control of the performing facilities and personnel, (2) protocols for candidate wait-listing and organ allocation, and (3) ongoing collection of standardized data elements” (Rose et al., 2019, p. 2).

An effort to further enhance both quality control and confidence in the U.S. organ transplant system—affecting both VCA and traditional organ transplantation—launched in March 2023. At that time, HRSA announced the OPTN Modernization Initiative, an effort to increase transparency and streamline the organ donation process. As a part of this initiative, in 2024 separation between the OPTN and UNOS boards of directors was finalized. The separation aimed to prevent conflicts of interest (HRSA, 2024). As these changes to the overarching transplantation system come to fruition,

NOTES: The Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA) acts as a liaison connecting the overlapping efforts of contractors. SRTR = The Scientific Registry of Transplant Recipients.

SOURCE: Adapted from NASEM, 2022.

the expectation is that the processes for solid organ and VCA donation will be made more equitable, efficient, and protected.

VCA Donation and the Uniform Anatomical Gift Act

Since 1968, the Uniform Anatomical Gift Act (UAGA)17 has served as a regulatory framework for organ donations in the United States and is the basis for how anatomical gifts can be made (Goodwin, 2006). This regulatory framework created legal rights for individuals to donate their body, or parts of it, for transplantation, education, or research upon their death. The UAGA is a product of the National Conference of Commissioners on Uniform State Laws as a means of creating laws for states that do not adopt it (NCCUSL, 2009). Every state has enacted the provisions of the 1968 Act in some way that allows a “decedent or surviving relatives to donate certain parts of the decedent’s organs for certain purposes, such as giving to those in need or for medical research” (Legal Information Institute, 2021). A 1987 revision sought to provide more clarity but was not widely adopted; however, the 2006 revision “expanded the list of persons who can consent to organ donation on behalf of an individual; gave every individual the opportunity to donate their organs at or near death; and stated that individuals who refuse to donate must explicitly state so” (Legal Information Institute, 2021; see also NASEM, 2022). The 2006 Act increased the focus on personal autonomy. Under Section 6, an individual may revoke or modify their donation status as long as they are deemed legally competent. Under Section 8, another person may not alter a donation decision made by another, with the exception of unemancipated minors, whose decision may be revoked by a parent (NCCUSL, 2009). The 2006 Act also authorized states to establish a donor registry using a set of minimum requirements, and while many states have done so, it is not required to do so (NCCUSL, 2009). The registry allows organ procurement organizations (OPOs) and health care providers to have access to health information regarding donor status. This information in the registry is more extensive than donation status indications on driver’s licenses. Despite the framework created by the UAGA, differences remain between states.18

Because the OPTN Final Rule (2014) established that VCAs are organs, the UAGA applies to VCA donation. However, OPTN policy and bylaws do not include VCA donation under general donor consent. The OPTN language says, “Recovery of vascularized composite allograft for transplant

___________________

17 See https://www.uniformlaws.org/viewdocument/final-act-19?CommunityKey=015e18ad4806-4dff-b011-8e1ebc0d1d0f&tab=librarydocuments (accessed October 24, 2024).

18 The Alliance maintains a website of state regulations that is current as of August 2023 (The Alliance, n.d.).

must be specifically authorized from the individual(s) authorizing the donation … consistent with applicable state law. The specific authorization must be documented by the host OPO” (OPTN, n.d.-b). This decision by the OPTN/UNOS VCA committee was made to ensure transparency in the donation request process.

The Role of OPOs

OPOs are responsible for assessing donor potential, discussing organ donations with families, and recovering organs from deceased donors. OPOs have played a vital role in the procurement of organs, particularly from deceased donors. OPOs may also discuss the creation of donor arm and face prostheses with donor families (OPTN, n.d.-a). Currently, there are 55 OPTN-approved OPOs in the United States, and they are tasked to meet the growing demands for organs in their specific regions and throughout the country (UNOS, n.d.). Data indicate that when families know the wishes of a relative, they are more likely to engage in discussions with OPOs and health care providers about organ donation (Rodrigue et al., 2010). This applies only to solid organ donations, however, because currently there is no mechanism on most donor registries to designate one’s intent to be a VCA donor. Indeed, most registries only accommodate a choice to be a donor (which is inclusive of tissues) or not. Some registries, such as California’s, do provide specific check boxes to specify what one wants to donate or exclude, and others provide a space to specify instructions concerning a donation. The practices of most OPOs are to obtain authorization for solid organs (i.e., kidneys, hearts, livers) and then to discuss tissue donation (i.e., bones, skin). Most OPOs do not assume authorization for the latter, even when the deceased is listed as a donor in a state registry. Thus, family decision makers, who are usually the deceased’s legal next of kin, are tasked— during already difficult circumstances—with deciding whether to authorize the donation of VCAs. This conversation is facilitated by personnel from the regional OPO, which manages the authorization and recovery of VCAs. Figure 2-7 shows the number of VCAs, by organ type, that have been coordinated by U.S. OPOs over a period of 26 years, and Table 2-1 shows the transplant centers that have performed a face or hand transplant in the last 5 years.

OPO personnel are responsible for educating and assisting next of kin in their decision making about VCA donation, which can be challenging for several reasons. Donating a face or hand requires consent independent of granting consent to donate solid organs; thus, a potential donor or his or her family has to weigh this additional organ donation consideration, often when the end-of-life approaches or shortly after death. A decision to be a VCA donor is made more challenging because most adults in the

SOURCE: Gift of Life Donor Program; presented by Rick Hasz, April 17, 2024, webinar.

United States have never heard of VCA donation (Gardiner et al., 2022). Furthermore, many donation professionals have little or no experience discussing VCA donations with families. In a survey of OPO professionals, 70 percent had never held a VCA donation discussion with the next of kin (Siminoff et al., 2020). Among OPO professionals who had explained what VCA was and how the recovery process works, many reported overall low levels of knowledge, comfort, and confidence talking with families about VCA. Although 44 percent of those surveyed had VCA-related training, 75 percent said that the training was insufficient (Siminoff et al., 2020).

Soon after faces and hands were classified as organs that could be donated, concerns were raised that families might rescind the deceased’s authorization to donate their solid organs if families were asked about donating faces or hand. Research has shown, however, that VCA donation has not had a negative impact on solid organ donation (Vece et al., 2021); instead, OPOs generally make stepped requests, starting with obtaining authorization for organ donation before moving to discuss tissues and then VCAs. Little is really known about these actual requests or next-of-kin responses because these opportunities are sporadic and have not been studied. Nonetheless, the push–pull effect has had an impact on OPOs, as the need for VCA donations directly relates to the number of wait-listed patients, and there are few for face or upper extremity transplants. Based on a survey conducted by the New England Donor Services, many OPOs do not have a locally approved VCA program, so the need for them to develop

TABLE 2-1 U.S. Transplant Centers That Have Performed a Face and/or Hand Transplant (2019–2024)

| Year | Center | Type of VCA |

|---|---|---|

| 2024 | University of Pennsylvania | Hand (bilateral) |

| 2024 | Mayo Clinic, Rochester | Face |

| 2023 | NYU Langone Health | Face |

| 2021 | Mayo Clinic, Rochester | Hand (bilateral) |

| 2020 | NYU Langone Health | Face and hand (bilateral) |

| 2020 | Brigham and Women’s Hospital | Face |

| 2019 | Brigham and Women’s Hospital | Face |

| 2019 | Duke University | Hand (unilateral) |

| 2019 | University of Pennsylvania | Hand (bilateral) |

SOURCES: Data from ASRT, n.d.; CNN, 2024; Homsey et al., 2024; NYU Langone Health, n.d.; OPTN, 2024b,e; Walker, 2019.

a VCA authorization protocol was seen as minimal.19 Within OPOs with VCA experience, quality control checks and documentation of the review are in place to ensure that donors are appropriately screened for VCA, and specific VCA coordination and recovery documents, transplant checklists, and intraoperative documents are readily available (OPTN, n.d.-a). There are no OPTN-approved programs to train OPO staff to make VCA requests for donation.

Additional Challenges Related to VCA Donation

Psychological Hurdles to Granting VCA Authorization

Potential donor families may wrestle with the psychological challenges that arise from face or hand donations. In face transplants, while the recipient’s final appearance will not mirror that of the donor due to differences in people’s facial bone structure, among other clinical factors, the concept of a loved one’s face on a stranger can be difficult to grasp for many people. This situation is made more challenging since face transplantations often receive significant media coverage and publicity by the transplant centers; thus, it is not uncommon for donor families to see photographs of a transplant recipient who received a VCA allograft from their decedent. Families may feel the need to alter funeral services after a relative has donated their hands or face, such as opting for closed casket funeral services, cremations, or the desire to use a facial mask or hand prosthesis for open casket funeral services (Brown et al., 2007; Gordon and Sieminow, 2009; Grant et al., 2014; OPTN, n.d.-a). Among those who were unwilling to provide authorization for VCA donation, the main reasons cited were identity loss, inability to have an open-casket funeral, reluctance to have family members see a body part on another person, and vague psychological discomfort (Rodrigue et al., 2017).

Public Support for Donation

There have been various surveys that have focused on public support for organ donation, as well as attitudes toward VCA donation (HRSA, 2020; Prior and Klen, 2011; Sarwer et al., 2014; Timar et al., 2021). According to the 2019 National Survey of Organ Donation Attitudes and Practices, approximately 90 percent of respondents supported or strongly supported organ donation, though just 50 percent of respondents are signed up to be

___________________

19 Presented by president and chief executive officer of New England Donor Services Alexandra Glazier at an information-gathering webinar. See https://www.nationalacademies.org/event/42240_04-2024_principles-and-framework-to-guide-the-development-of-protocols-and-standard-operating-procedures-for-face-and-hand-transplants-webinar-2 (accessed September 9, 2024).

organ donors (HRSA, 2020). Despite the overall high amount of support for the organ donation system, between 2012 and 2019 concerns related to organ donation increased by 9.3 percent (HRSA, 2020). In 2019, 64 percent of respondents were willing to donate their hands, and 47 percent were willing to donate their face, while in 2012, 80 percent were willing to donate their hands and 58 percent were willing to donate their face (HRSA, 2020). Over the same time period, next of kin also grew less likely to give permission to donate the hand or face of a family member. Approximately 59 percent were willing to donate a family member’s hands, and approximately 44 percent were willing to donate a loved one’s face (HRSA, 2020). These responses are similar to those for solid organ donation when individuals are asked about willingness to donate one’s own organs compared with a family member’s, which is likely reflective of the hypothetical nature of the questions and the need to know the wishes of the potential donor’s wishes. Educational interventions have been shown to increase the willingness to donate VCA organs (Plana et al., 2018; Rodrigue et al., 2017).

Public Education about VCA

The public’s knowledge and understanding of tissue donation is limited, and one study of next of kin reports that the public is largely unaware that a signed donor card grants legal authorization for tissue donation (Siminoff et al., 2010). This lack of public understanding has led many OPOs to work to obtain explicit authorization of tissues from next of kin even when the deceased is a registered donor. Interestingly, once next of kin have authorized or accepted a deceased’s prior authorization of organ donation, they are far more likely to authorize tissues or even donation for research purposes. For example, brain donation for the GTEx biobanking project was high (78 percent) once the next of kin agreed to organ transplantation (Siminoff et al., 2021).

Public awareness of face and hand transplants is also relatively low in the United States. Although face, hand, and uterus VCAs appear most often in education materials from OPOs, the educational materials have historically failed to describe the populations that benefit from the procedures, leading to gaps in knowledge (Van Pilsum Rasmussen et al., 2020). Education videos appear to greatly benefit VCA by boosting public awareness of face and hand transplantation and may increase willingness to provide consent for donation after death (Plana et al., 2018). Video messaging can increase favorable attitudes toward VCA and VCA donation, including among military and veteran populations. Blended messaging, combining factual information with personal testimony, increased the willingness to donate among veterans by 144 percent (Rodrigue et al., 2022).

A mixed-methods study of the attitudes and beliefs of the general public concerning VCA was conducted with 53 participants across six focus groups. The major themes discussed were strong initial reactions toward VCA, limited knowledge and reservations about VCA, risks versus rewards when pursing a VCA, information needed in order to authorize a donation, attitudes toward donation, and overall mistrust of the donation system (Gardiner et al., 2022). The discussions revealed a general unwillingness to receive a VCA or authorize VCA donation on behalf of a family member, although 85 percent of participants reported a willingness to receive a solid organ transplant in the survey (Gardiner et al., 2022). Nonetheless, overall findings from the small number of studies conducted to date reveal that while there is limited exposure and confusion about VCAs by the public, the overall impression about VCAs is favorable, indicating the potential value of public education campaigns.

CHAPTER 2 KEY FINDINGS

The first successful hand transplant took place in 1998, and the first successful face transplant took place in 2005. Other VCA procedures include uterine, penile, abdominal wall, and larynx transplantations. Face and hand transplants are technically feasible and have been performed multiple times at different institutions, with both successful and non-successful outcomes. Worldwide, 53 face transplants have been reported to date, with 20 completed in the United States. Worldwide, approximately 151 hand transplants have been performed to date, with 38 completed in the United States.20 In the United States across VCA organ types, most VCA recipients have been White, compared with Black or Hispanic patients. There is limited research on the factors contributing to potential racial and ethnic disparities in VCA, such as the role of poverty, access to primary care, and social determinants of health; much remains unknown.

Since the OPTN Final Rule was expanded to include VCA in 2014, all U.S. transplant centers that perform VCAs are required to follow similar guidelines to other solid organ transplants, with the goal of promoting safety and improving patient outcomes. To become an active face or hand transplant center in the United States, each program must be a member of the OPTN at a center with at least one other active solid organ transplant program and must meet OPTN requirements including program

___________________

20 As of December 2024. The number of face and hand transplants was calculated by recipient who received a transplant. Thus, a bilateral hand transplant is not counted as two transplants. However, a re-transplant is treated as a new transplant and therefore counted as an additional transplant in the total amount, despite the transplant being performed on the same recipient.

requirements and requirements for individuals serving as primary transplant physicians and surgeons at VCA transplant programs. Under the OPTN, VCA programs must meet specific requirements, including quality control of the performing facilities and personnel, protocols for candidate wait-listing and organ allocation, and ongoing collection of standardized data elements. Data submission includes patient demographics, immunosuppression regimens, complications, rejection episodes, blood types, donor authorization requirements, and other clinical parameters. Currently, the data submitted are often incomplete and not shared or standardized among transplant centers, outside of the OPTN regulatory requirements.

As of December 2024, in the United States there were 10 approved and active sites for head and neck VCA procedures and 11 approved and active sites for upper limb transplants. Five sites have been approved to perform both head and neck and upper limb VCA procedures. Face and hand transplant centers are geographically concentrated along the East Coast, with two centers in the Midwest and two on the West Coast. Since 2002, the IRHCTT has been collecting voluntary data from transplant centers related to face and hand transplantation. Participants in the IRHCTT include 9 centers in the United States and 29 centers outside of the United States.

Despite the framework established by the UAGA and NOTA, there are gaps and challenges related to VCA donation at both the state and federal levels. For example, donor authorization for VCA is required separate from authorization for solid organ donation. Authorization for donation has multiple challenges, including that many donation professionals do not have experience discussing VCA donation with families, there may be concerns related to funeral services for the potential donor, and there is a lack of public education and awareness around VCA. However, asking for VCA donation authorization has not affected solid organ donation rates. As the need for VCA donation increases, a public education campaign and specialized training for OPO staff to discuss this opportunity to help others will likely be needed.

REFERENCES

Ahmad, T. S., A. A. Ahmad, and S. Abdullah. 2021. Hand surgery in Malaysia. Journal of Hand and Microsurgery 13(01):21–26.

Alberti, F. B., and V. Hoyle. 2021. Face transplants: An international history. Journal of the History of Medicine and Allied Sciences 76(3):319–345.

The Alliance. n.d. State legislation & donor registries by state. https://www.organdonationalliance.org/resources/state-uaga-legislation-organ-registry-info/ (accessed October 24, 2024).

Amaral, S., S. K. Kessler, T. J. Levy, W. Gaetz, C. McAndrew, B. Chang, S. Lopez, E. Braham, D. Humpl, and M. Hsia. 2017. 18-month outcomes of heterologous bilateral hand transplantation in a child: A case report. The Lancet Child & Adolescent Health 1(1):35–44.

Amma. 2022. Surgeons perform two more complex bilateral hand transplants at Amrita Hospital, Kochi. https://amma.org/news/handtransplants-sept-2022/ (accessed October 1, 2024).

Amrita Hospital. 2024. A new beginning for Nidhi: Another successful hand transplant at Amrita Hospital, Kochi. https://www.amritahospitals.org/kochi/news/new-beginning-nidhi-another-successful-hand-transplant-amrita-hospital-kochi (accessed October 1, 2024).

Amrita Vishwa Vidyapeetham. 2022. Amrita Hospital successfully completes 12th hand transplant surgery. https://www.amrita.edu/news/amrita-hospital-successfully-completes-12th-hand-transplant-surgery/ (accessed October 1, 2024).

ap7am.com. 2024. Ujjain man undergoes “bilateral hand transplant” at Mumbai Hospital; plans to marry now. https://www.ap7am.com/en/76357/ujjain-man-undergoes-bilateral-hand-transplant-at-mumbai-hospital-plans-to-marry-now (accessed October 1, 2024).

ASRT (American Society for Reconstructive Transplantation). n.d. Bilateral arm transplant recently performed by the Penn Hand Transplant Program. https://www.a-s-r-t.com/ (accessed January 16, 2025).

Aycart, M. A., H. Kiwanuka, N. Krezdorn, M. Alhefzi, E. M. Bueno, B. Pomahac, and M. L. Oser. 2017. Quality of life after face transplantation: Outcomes, assessment tools, and future directions. Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery 139(1):194-203.

Azoury, S. C., I. Lin, S. Amaral, B. Chang, and L. S. Levin. 2020. The current outcomes and future challenges in pediatric vascularized composite allotransplantation. Current Opinion in Organ Transplantation 25(6):576–583.

Baudouin, R., F. Von Tokarski, T. Rigal, A. Crambert, A. Hertig, and S. Hans. 2024. Immunosuppressive protocols after laryngeal transplantation: A systematic review. Acta Oto-Laryngologica 144(3):243–249.

Brown, C. S., B. Gander, M. Cunningham, A. Furr, D. Vasilic, O. Wiggins, J. C. Banis, M. Vossen, C. Maldonado, G. Perez-Abadia, and J. H. Barker. 2007. Ethical considerations in face transplantation. International Journal of Surgery 5(5):353–364.

Carroll, D. 1965. A quantitative test of upper extremity function. Journal of Chronic Diseases 18(5):479–491.

Castellón, L. A. R., M. I. G. Amador, R. E. D. González, M. S. J. Eduardo, C. Díaz-García, N. Kvarnström, and M. Bränström. 2017. The history behind successful uterine transplantation in humans. JBRA Assisted Reproduction 21(2):126–134.

Cavadas, P., L. Landin, and J. Ibanez. 2009. Bilateral hand transplantation: Result at 20 months. Journal of Hand Surgery (European Volume) 34(4):434–443.

Cavadas, P. C., L. Landin, A. Thione, J. C. Rodríguez-Pérez, M. A. Garcia-Bello, J. Ibañez, F. Vera-Sempere, P. Garcia-Cosmes, L. Alfaro, and J. D. Rodrigo. 2011. The Spanish experience with hand, forearm, and arm transplantation. Hand Clinics 27(4):443–453.

Cendelo, E., P. C. Belafsky, M. Corrales, D. G. Farwell, L. F. Gonzales, M. Grajek, D. A. Walczak, M. Strome, R. R. Lorenz, L. F. Tintinago, M. A. Velez, W. Victoria, and M. Birchall. 2024. The global experience of laryngeal transplantation: Series of eleven patients in three continents. Laryngoscope 134(10):4313-4320.

Chang Gung Memorial Hospital. 2022. Milestone. https://www.cgmh.org.tw/eng/about/milestone (accessed September 9, 2024).

Clark, B., C. Carter, D. J. Wilks, M. Lobb, P. Hughes, R. Baker, and S. P. Kay. 2020. The Leeds hand transplant programme: Review of the laboratory management of the first six cases. International Journal of Immunogenetics 47(1):28–33.

CNN. 2024. Survivor of suicide attempt receives innovative face transplant: ‘It was just a miracle’. https://www.cnn.com/2024/11/19/health/suicide-survivor-face-transplant/index.html (accessed December 13, 2024).

Dean, W., and B. Randolph. 2015. Vascularized composite allotransplantation: Military interest for wounded service members. Current Transplantation Reports 2(3):290–296.

Deccan Herald. 2024. 15-year-old Mumbai girl becomes first in the world to successfully undergo hand transplant at shoulder level. https://www.deccanherald.com/science/15-year-old-mumbai-girl-becomes-first-in-the-world-to-successfully-undergo-hand-transplant-at-shoulder-level-3207772 (accessed October 1 2024).

Diep, G. K., Z. P. Berman, A. R. Alfonso, E. P. Ramly, D. Boczar, J. Trilles, R. Rodriguez Colon, B. F. Chaya, and E. D. Rodriguez. 2021. The 2020 facial transplantation update: A 15-year compendium. Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery—Global Open 9(5):e3586.

DoD (Department of Defense). 2020. DoD instruction 6130.03, volume 2: Medical standards for military service: Retention. https://www.esd.whs.mil/Portals/54/Documents/DD/issuances/dodi/613003_vol02.PDF (accessed November 11, 2024).

Doumit, G., B. B. Gharb, A. Rampazzo, F. Papay, M. Z. Siemionow, and J. E. Zins. 2014. Pediatric vascularized composite allotransplantation. Annals of Plastic Surgery 73(4):445–450.

Dwyer, K., A. Webb, H. Furniss, K. Anjou, D. Purtell, J. Gibbs-Dwyer, D. McCombe, D. Grin-sell, R. Williams, and R. Deam. 2012. Australia’s first hand transplant: Outcome at 1 year. Transplantation 94(10S):956.

The Economic Times. 2022. Mumbai: 22-year-old accident victim gets hand from brain dead Gujarat man. https://economictimes.indiatimes.com/news/india/mumbai-22-year-old-accident-victim-gets-hand-from-brain-dead-gujarat-man/articleshow/89801717.cms (accessed October 1 2024).

Eggleton, P. 2010. Double hand transplant carried out in Monza. https://www.italymagazine.com/featured-story/double-hand-transplant-carried-out-monza (accessed September 9, 2024).

Errico, M., N. H. Metcalfe, and A. Platt. 2012. History and ethics of hand transplants. JRSM Short Reports 3(10):74.

Feng, Y., F. J. Schlösser, and B. E. Sumpio. 2011. The Semmes-Weinstein monofilament examination is a significant predictor of the risk of foot ulceration and amputation in patients with diabetes mellitus. Journal of Vascular Surgery 53(1):220–226.e225.

Fernandez, J. J. G., R. G. Febres-Cordero, and R. L. Simpson. 2019. The untold story of the first hand transplant: Dedicated to the memory of one of the great minds of the Ecuadorian medical community and the world. Journal of Reconstructive Microsurgery 35(03):163–167.

France 24. 2009. French hospital performs first hands and face transplant. https://www.france24.com/en/20090406-french-hospital-performs-first-hands-face-transplant- (accessed May 2, 2024).

Fries, C., D. Tuder, V. Gorantla, R. Chan, and M. Davis. 2020. Military VCA in the world. Current Transplantation Reports 7:246–250.

Furniss, H., K. Dwyer, A. Webb, H. Opdam, and W. Morrison. 2012. Australia’s first hand transplant: Guidelines for facilitating upper limb donation for the purpose of transplantation. Transplantation 94(10S):606.

Gardiner, H. M., E. E. Davis, G. P. Alolod, D. B. Sarwer, and L. A. Siminoff. 2022. A mixed-methods examination of public attitudes toward vascularized composite allograft donation and transplantation. SAGE Open Medicine 10:20503121221125379.

The Guardian. 2008. German farmer gets world’s first double arm transplant. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2008/aug/02/germany (accessed May 2, 2024).

Glazier, A. K. 2016. Regulatory oversight in the United States of vascularized composite allografts. Transplant International 29(6):682–685.

Gobierno de Mexico. 2016. A successful bilateral hand reimplantation was made at Mexico’s general hospital “Eduardo Liceaga.” https://www.gob.mx/salud/prensa/a-successful-bilateral-hand-reimplantation-was-made-at-mexico-s-general-hospital-eduardo-liceaga (accessed September 9, 2024).

Goodwin, M. 2006. Black markets: The supply and demand of body parts. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Gordon, C. R., and M. Siemionow. 2009. Requirements for the development of a hand transplantation program. Annals of Plastic Surgery 63(3):262–273.

Grant, G. T., P. Liacouras, G. F. Santiago, J. R. Garcia, M. Al Rakan, R. Murphy, M. Armand, and C. R. Gordon. 2014. Restoration of the donor face after facial allotransplantation: Digital manufacturing techniques. Annals of Plastic Surgery 72(6):720–724.

Greenfield, J. A., L. L. Kimberly, Z. P. Berman, E. P. Ramly, A. R. Alfonso, O. Lee, G. K. Diep, and E. D. Rodriguez. 2020. Perceptions of quality of life among face transplant recipients: A qualitative content analysis. Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery—Global Open 8(8):e2956.

Hale, R. G. 2011. The military relevance of face composite tissue allotransplantation and regenerative medicine research. The Know-How of Face Transplantation. London, UK. Pp. 401–409.

Hamilton, N. J., M. Kanani, D. J. Roebuck, R. J. Hewitt, R. Cetto, E. J. Culme-Seymour, E. Toll, A. J. Bates, A. P. Comerford, C. A. McLaren, C. R. Butler, C. Crowley, D. McIntyre, N. J. Sebire, S. M. Janes, C. O’Callaghan, C. Mason, P. De Coppi, M. W. Lowdell, M. J. Elliott, and M. A. Birchall. 2015. Tissue-engineered tracheal replacement in a child: A 4-year follow-up study. American Journal of Transplantation 15(10):2750–2757.

Hautz, T., F. Messner, A. Weissenbacher, H. Hackl, M. Kumnig, M. Ninkovic, V. Berchtold, J. Krapf, B. G. Zelger, B. Zelger, D. Wolfram, G. Pierer, W. N. Löscher, R. Zimmermann, M. Gabl, R. Arora, G. Brandacher, R. Margreiter, D. Öfner, and S. Schneeberger. 2020. Long-term outcome after hand and forearm transplantation—A retrospective study. Transplant International 33(12):1762–1778.

Hernandez, J. A., J. Miller, N. C. Oleck, D. Porras-Fimbres, J. Wainright, K. Laurie, S. E. Booker, G. Testa, A. K. Israni, and L. C. Cendales. 2022. OPTN/SRTR 2020 annual data report: VCA. American Journal of Transplantation 22:623–647.

Hernandez, J. A., J. M. Miller, E. Emovon III, J. N. Howell, G. Testa, A. K. Israni, J. J. Snyder, and L. C. Cendales. 2024. OPTN/SRTR 2022 annual data report: Vascularized composite allograft. American Journal of Transplantation 24(2):S534–S556.

HHS (Department of Health and Human Services). n.d. OPTN membership application for vascularized composite allograft (VCA) transplant programs. https://unos.org/wp-content/uploads/FORM-OPTN-Membership-App-VCA.pdf (accessed October 2, 2024).

The Hindu. 2018. Hand transplant patient going strong. https://www.thehindu.com/news/cities/chennai/hand-transplant-patient-going-strong/article25052017.ece (accessed October 1, 2024).

Homsy, P., L. Huelsboemer, J. P. Barret, P. Blondeel, D. E. Borsuk, D. Bula, B. Gelb, P. Infante-Cossio, L. Lantieri, and S. Mardini. 2024. An update on the survival of the first 50 face transplants worldwide. JAMA Surgery, September 18:e243748 [online ahead of print].

Honeyman, C., R. Dolan, H. Stark, C. A. Fries, S. Reddy, P. Allan, G. Vrakas, A. Vaidya, G. Dijkstra, and S. Hofker. 2020. Abdominal wall transplantation: Indications and outcomes. Current Transplantation Reports 7:279–290.

HRSA (Health Resources and Services Administration). 2014. Data collection and submission requirements for vascularized composite allografts (VCAs). https://optn.transplant.hrsa.gov/policies-bylaws/public-comment/data-collection-and-submission-requirements-for-vascularized-composite-allografts-vcas/ (accessed November 27, 2024).

HRSA. 2020. National Survey of Organ Donation Attitudes and Practices, 2019. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. https://www.organdonor.gov/sites/default/files/organ-donor/professional/grants-research/nsodap-organ-donation-survey-2019.pdf (accessed November 26, 2024).

HRSA. 2024. Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network (OPTN) Modernization Initiative. https://www.hrsa.gov/optn-modernization (accessed June 6, 2024).

Hudak, P. L., P. C. Amadio, C. Bombardier, D. Beaton, D. Cole, A. Davis, G. Hawker, J. N. Katz, M. Makela, and R. G. Marx. 1996. Development of an upper extremity outcome measure: The DASH (Disabilities of the Arm, Shoulder, and Head). American Journal of Industrial Medicine 29(6):602–608.

Hurriyet Daily News. 2016. Turkey’s third double arm transplant performed in Antalya. https://www.hurriyetdailynews.com/turkeys-third-double-arm-transplant-performed-in-antalya--94699 (accessed September 9, 2024).

Iglesias, M., P. Butron, M. Moran-Romero, A. Cruz-Reyes, J. Alberu-Gomez, P. Leal-Villalpando, J. Bautista-Zamudio, M. Ramirez-Berumen, E. Lara-Hinojosa, and V. Espinosa-Cruz. 2016. Bilateral forearm transplantation in Mexico: 2-year outcomes. Transplantation 100(1):233–238.

India Today. 2023. Rajasthan man becomes first Asian to undergo total arm transplant at Mumbai hospital. https://www.indiatoday.in/india/story/rajasthan-man-becomes-first-asian-to-undergo-total-arm-transplant-at-mumbai-hospital-2348204-2023-03-18 (accessed October 1 2024).

India Today. 2024. Faridabad hospital conducts north India’s first-ever successful hand transplant. https://www.indiatoday.in/india/story/faridabad-amrita-hospital-hand-transplant-first-in-north-india-kidney-transplant-2491466-2024-01-21 (accessed October 1, 2024).

Indian Transplant Newsletter. 2023. SSKM becomes first hospital in eastern India to perform hand transplantation. https://www.itnnews.co.in/indian-transplant-newsletter/issue69/SSKM-Becomes-First-Hospital-in-Eastern-India-to-Perform-Hand-Transplantation-1246.htm (accessed October 1 2024).

IRHCTT (International Registry on Hand Composite Tissue Transplantation). n.d. Home page. https://handregistry.com/ (accessed April 5, 2024).

Iyer, S. 2023. Hand transplant programme in India—Progress and future. Indian Transplant Newsletter 22(2):4. https://www.itnnews.co.in/indian-transplant-newsletter/issue69/Hand-Transplant-Programme-in-India-Progress-and-Future-1249.htm (accessed November 26, 2024).

Jablecki, J., L. Kaczmarzyk, A. Domanasiewicz, A. Chelmonski, M. Boratynska, and D. Patrzalek. 2010. Hand transplantation—Polish program. Transplantation Proceedings 42(8):3321–3322.

JIPMER Deceased Donor Transplantation Committee. 2020. Establishing a deceased donor transplantation program and its impact in a public sector hospital in India—A single centre experience from India. Indian Journal of Transplantation 14(4):321–332.

Kalantar-Hormozi, A., F. Firoozi, M. Yavari, E. Arasteh, K. Najafizadeh, and F. Rashid-Farokhi. 2013. The first hand transplantation in Iran. International Journal of Organ Transplantation Medicine 4(3):125–127.

Kumnig, M., S. G. Jowsey-Gregoire, E. J. Gordon, and G. Werner-Felmayer. 2022. Psychosocial and bioethical challenges and developments for the future of vascularized composite allotransplantation: A scoping review and viewpoint of recent developments and clinical experiences in the field of vascularized composite allotransplantation. Frontiers of Psychology 13:1045144.

Kuo, Y. R., C. C. Chen, Y. C. Chen, M. C. Yeh, P. Y. Lin, C. H. Lee, J. K. Chang, Y. C. Lin, S. C. Huang, Y. C. Chiang, N. M. Chiu, Y. Lee, Y. C. Huang, J. L. Liang, R. W. Wu, K. K. Siu, K. C. Chung, M. H. Chiang, C. C. Pan, and F. C. Wei. 2016. The first hand allotransplantation in Taiwan: A report at 9 months. Annals of Plastic Surgery 77(Suppl 1):S12–S15.

Kvernmo, H. D., V. S. Gorantla, R. N. Gonzalez, and W. C. Breidenbach III. 2005. Hand transplantation: A future clinical option? Acta Orthopaedica 76(1):14–27.

Lanzetta, M. 2017. Hand transplantation in children: Is it too early or too late? The Lancet Child & Adolescent Health 1(1):4–6.

Lanzetta, M., R. Nolli, G. Vitale, F. Magni, I. Radaelli, L. Stroppa, G. Urso, E. Martinez, G. Lucchini, P. Pioltelli, I. Carta, O. Convertino, P. Petruzzo, A. Cappellini, R. Coletti, C. Dezza, S. Lucchina, A. Rampa, L. Rovati, and M. Scalamogna. 2007. Hand transplantation: The Milan experience. Polski Przeglad Chirurgiczny 79:1379–1397.

Lee, N., W. Y. Baek, Y. R. Choi, D. J. Joo, W. J. Lee, and J. W. Hong. 2023. One year experience of the hand allotransplantation first performed after Korea Organ Transplantation Act (KOTA) amendment. Archives of Plastic Surgery 50(4):415–421.

Legal Information Institute. 2021. Uniform Anatomical Gift Act. https://www.law.cornell.edu/wex/uniform_anatomical_gift_act (accessed November 7, 2024).

Leonard, D., I. Natalwala, S. Taplin, J. Burdon, G. Bourke, and S. P. Kay. 2024. Hand and upper limb transplant—The UK experience. Transplantation 108(9S).

Lewis, H. C., and L. C. Cendales. 2021. Vascularized composite allotransplantation in the United States: A retrospective analysis of the organ procurement and transplantation network data after 5 years of the final rule. American Journal of Transplantation 21(1):291–296.

Lopez, C. D., A. O. Girard, I. V. Lake, B. C. Oh, G. Brandacher, D. S. Cooney, A. L. Burnett, and R. J. Redett. 2023. Lessons learned from the first 15 years of penile transplantation and updates to the Baltimore criteria. Nature Reviews Urology 20(5):294–307.

Mayo Clinic. 2024. Larynx and trachea transplant program. https://www.mayoclinic.org/departments-centers/larynx-trachea-transplant/overview/ovc-20508897 (accessed August 29, 2024).

Mendenhall, S. D., J. D. Sawyer, B. L. West, M. W. Neumeister, A. Shaked, and L. S. Levin. 2019. Pediatric vascularized composite allotransplantation: What is the landscape for obtaining appropriate donors in the united states? Pediatric Transplantation 23(5):e13466.

Murcia Today. 2024. Spanish doctors perform world’s first face transplant on patient whose heart has stopped https://murciatoday.com/spanish_doctors_perform_world_39_s_first_face_transplant_on_patient_whose_heart_had_stopped_1000135562-a.html (accessed October 2, 2024).

NASEM (National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine). 2017. Opportunities for organ donor intervention research: Saving lives by improving the quality and quantity of organs for transplantation. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

NASEM. 2022. Realizing the promise of equity in the organ transplantation system. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

NCCUSL (National Conference of Commissioners on Uniform State Laws). 2009. Revised Uniform Anatomical Gift Act (2006). https://wcmea.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/01/Uniform-Anatomical-Gift-Act.pdf (accessed January 3, 2025).

NYU Langone Health. n.d. NYU Langone Health performs world’s first successful face & double hand transplant. https://nyulangone.org/news/nyu-langone-health-performs-worlds-first-successful-face-double-hand-transplant (accessed August 8, 2024).

OPTN (Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network). n.d.-a. Guidance on optimizing VCA recovery from deceased donors. https://optn.transplant.hrsa.gov/media/2503/vca_guidance_201806.pdf (accessed July 22, 2024).

OPTN. n.d.-b. Guidance to organ procurement programs (OPOs) for VCA deceased donor authorization. https://optn.transplant.hrsa.gov/media/1137/vca_donor_guidance.pdf (accessed June 10, 2024).

OPTN. 2020a. Briefing to the OPTN board of directors on update to VCA transplant outcomes data collection. https://optn.transplant.hrsa.gov/media/3809/202006_vca_data_collection_bp.pdf (accessed April 5, 2024).

OPTN. 2020b. Notice of OPTN data collection changes—Update to VCA transplant outcomes data collection. https://optn.transplant.hrsa.gov/media/3889/update-to-vca-transplant-outcomes-data-collection.pdf (accessed April 5, 2024).

OPTN. 2020c. Notice of OPTN policy and bylaw changes—Vascularized composite allograft membership changes. https://optn.transplant.hrsa.gov/media/3922/20200731_vca_membershipchanges_policynotice.pdf (accessed February 29, 2024).

OPTN. 2020d. Update to VCA transplant outcomes data collection. https://optn.transplant.hrsa.gov/policies-bylaws/public-comment/update-to-vca-transplant-outcomes-data-collection/ (accessed January 2, 2025).

OPTN. 2024a. About OPTN membership. https://optn.transplant.hrsa.gov/about/about-optn-membership/ (accessed Febraury 15, 2025).

OPTN. 2024b. National data. https://optn.transplant.hrsa.gov/data/view-data-reports/national-data/ (accessed December 31, 2024).

OPTN. 2024c. Transplant centers by organ. https://hrsa.unos.org/about/search-membership/ (accessed February 15, 2024).

Özkan, Ö., F. Demirkan, A. Dinçkan, N. Hadimioglu, S. Tuzuner, G. Suleymanlar, and F. Gunseren. 2011. The first (double) hand transplantation in Turkey. Transplantation Proceedings 43(9):3557–3560.

Parent, B. 2014. Informing donors about hand and face transplants: Time to update the Uniform Anatomical Gift Act. Journal of Health & Biomedical Law 10:309.

Patel, T., S. Rackimuthu, H. Jindal, and S. Goyal. 2022. The current status of hand transplantation in India: Challenges and opportunities. Orthoplastic Surgery. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.orthop.2022.06.001.

Pei, G., D. Xiang, L. Gu, G. Wang, L. Zhu, L. Yu, H. Wang, X. Zhang, J. Zhao, and C. Jiang. 2012. A report of 15 hand allotransplantations in 12 patients and their outcomes in China. Transplantation 94(10):1052–1059.

Petruzzo, P., E. Morelon, J. Kanitakis, L. Badet, A. Eljaafari, M. Lanzetta, E. Owen, and J.-M. Dubernard. 2008. Hand transplantation: Lyon experience. In C. W. Hewitt, W. P. A. Lee, and C. R. Gordon (eds.), Transplantation of composite tissue allografts. Boston, MA: Springer. Pp. 209–214.

Petruzzo, P., M. Lanzetta, J. M. Dubernard, L. Landin, P. Cavadas, R. Margreiter, S. Schneeberger, W. Breidenbach, C. Kaufman, J. Jablecki, F. Schuind, and C. Dumontier. 2010. The International Registry on Hand and Composite Tissue Transplantation. Transplantation 90(12):1590–1594.

Plana, N. M., L. L. Kimberly, B. Parent, K. S. Khouri, J. R. Diaz-Siso, E. M. Fryml, C. C. Motosko, D. J. Ceradini, A. Caplan, and E. D. Rodriguez. 2018. The public face of transplantation: The potential of education to expand the face donor pool. Plastic and Reconstructive Ssurgery 141(1):176–185.

Polish Press Agency. 2017. University Hospital of Wroclaw is first in the world to transplant a hand to an adult patient. https://poland.pl/business-and-science/achievements-science/university-hospital-wroclaw-first-world-transplant-hand-adult-pa/ (accessed May 2, 2024).

Prior, J. J., and O. Klein. 2011. A qualitative analysis of attitudes to face transplants: Contrasting views of the general public and medical professionals. Psychology & Health 26(12):1589–1605.

Rahmel, A. 2014. Vascularized composite allografts: Procurement, allocation, and implementation. Current Transplantation Reports 1(3):173-182.

Rifkin, W. J., A. Manjunath, L. L. Kimberly, N. M. Plana, R. S. Kantar, G. L. Bernstein, J. R. Diaz-Siso, and E. D. Rodriguez. 2018. Long-distance care of face transplant recipients in the United States. Journal of Plastic, Reconstructive & Aesthetic Surgery 71(10):1383–1391.

Rodrigue, J. R., D. L. Cornell, J. Krouse, and R. J. Howard. 2010. Family initiated discussions about organ donation at the time of death. Clinical Transplantation 24(4):493–499.

Rodrigue, J. R., D. Tomich, A. Fleishman, and A. K. Glazier. 2017. Vascularized composite allograft donation and transplantation: A survey of public attitudes in the United States. American Journal of Transplantation 17(10):2687–2695.