Safeguarding the Food Supply: Integrating Diverse Risks, Connecting with Consumers, and Protecting Vulnerable Populations: Proceedings of a Workshop (2025)

Chapter: 5 Exploring Opportunities for the Future of Food Safety

5

Exploring Opportunities for the Future of Food Safety

In the final session, moderated by Keeve E. Nachman, speakers shared brief remarks on the opportunities and challenges for the field, as well as their reactions to the workshop discussion. Various perspectives included exploring alternative approaches to measuring exposure and how to mitigate risk, using genomics and advanced analytics, using different methods for data collection, and going beyond current frameworks and ways of thinking to be more collaborative in the future and work together for common goals.

PERSPECTIVES ON THE FUTURE OF FOOD SAFETY

Alternative Approaches to Measuring Exposure

Gary Ginsberg, Yale University and New York State Department of Health, shared three general observations, beginning with the need to change the culture, and the ongoing challenge of shifting from reactive to preventive approaches while acknowledging that the focus is often on just a small portion of the “haystack.” He also brought up vulnerable populations and disparities, noting that though it was not a key topic in the workshop, policy makers are increasingly focusing on how to do a better job of identifying disparities and finding ways to address them in environmental health, and this is highly relevant to food safety. Ginsberg also shared some of his research focusing on pragmatic approaches when risk-based approaches do not work, using inorganic arsenic in foods for young children as an example.

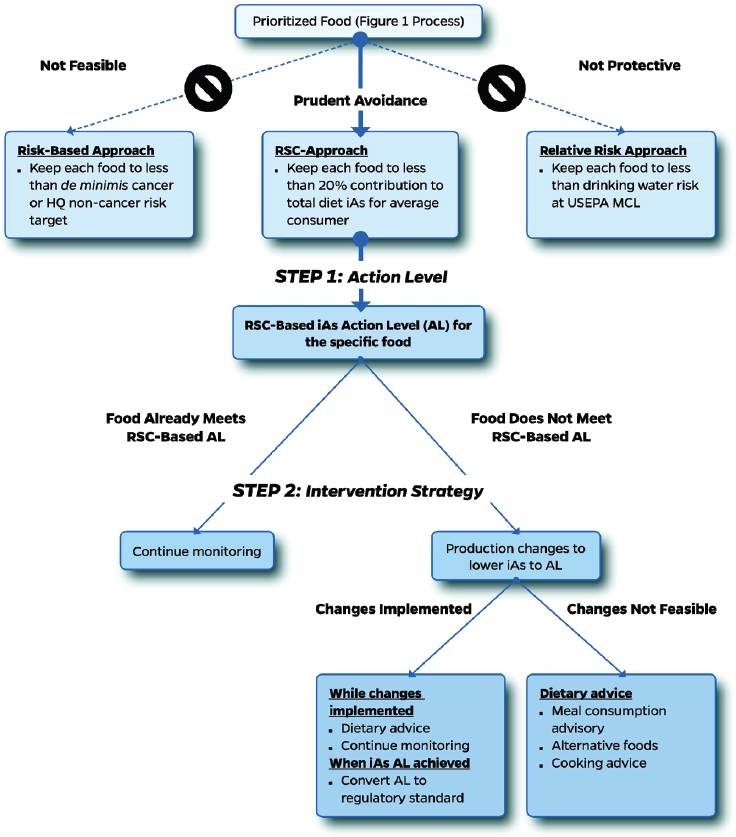

Developing an action level for inorganic arsenic will be difficult to do in a risk-based way, he explained. The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) inorganic arsenic action level in apple juice, developed in 2023, is 10 parts per billion, and therefore it is estimated that one juice box per day for a 3- to 6-year-old would provide 70 times higher cancer risk than de minimis. This is based on the old slope factor for which there are proposals to increase potency, he said. If this risk-based approach is not feasible, he proposed using a relative source contribution approach to set action levels and consider consumption advisories. This method examines cumulative exposure sources for contaminants, aims to limit individual source contributions to reasonable proportions of the total exposure, and uses a target threshold of 20 percent contribution to the total diet of inorganic arsenic from any single source (see Figure 5-1).

As an example, infant rice cereal can contribute 46 percent of a child’s inorganic arsenic exposure during solid food introduction, he explained. But the research suggests that reducing consumption to twice weekly would align with the 20 percent target. Ginsberg warned that this is a careful balance, and that public food advisories are fraught with communication issues, with some people ignoring them completely and others overreacting and then avoiding certain foods entirely. He said it is important to ensure alternative food options, align with existing medical guidance (such as diversifying first foods beyond rice cereal), and recognizing the challenge of prioritizing which foods to target in a fair and equitable way.

Leveraging Genomics and Risk Analytics

Francisco J. Zagmutt, EpiX Analytics, discussed the use of genomics and risk analytics to create a safer food system. Current regulatory approaches using “carrots and sticks” have not significantly improved microbial food safety over the past 10–15 years, he said. Zagmutt presented a case study combining genomics and risk analytics to enhance food safety, initially focusing on Salmonella control. The research addressed two key challenges in controlling pathogen risks in foods. First, there is a need to target higher-virulence Salmonella serovars rather than treating all serovars as equally risky. Second, identifying such higher-virulence serovar targets based solely on reported foodborne illness data is inappropriate, as such data lacks statistical power to detect disease trends in a timely fashion This study combined genetic and epidemiological data to identify higher-virulence Salmonella serovars that had a distinct genomic profile and also had significantly higher rates of illness, hospitalization and mortality compared to lower virulence groups (Fenske et al., 2023).

In addition to better public–private partnerships in the future, Zagmutt also called for formalizing the implementation of genomics—as well as

NOTE: AL = action level; iAs = inorganic arsenic; HQ = hazard quotient; RSC = relative source contribution; USEPA MCL = U.S. Environmental Protection Agency’s maximum contaminant level.

SOURCES: Presented by Gary Ginsberg on September 5, 2024, from Nachman et al., 2017. CC-BY-NC-ND.

artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning (ML)—into the risk analysis process. Gaining a better understanding of genomic drivers of virulence can improve prediction and risk management, ultimately increasing public health. Lastly, he noted that food safety innovation requires federal investment, especially in private-sector incentives.

Considering Different Methods and Data

Kerry A. Hamilton, Arizona State University, offered three suggestions for future opportunities: systems-level improvements to risk analysis, different types of data needs, and social considerations. She highlighted the need for system-level improvements to address unknown or unrecognized food contaminants. She called for improving the non-targeted approaches for chemical analysis and using metagenomics on the microbial side to narrow down the hazard(s) of focus. There are many existing approaches for accounting for chemical toxicity mechanisms, but fewer exist for microbial-associated outcomes. Increased implementation of Bayesian models to establish baselines and enable faster throughput could help with this, she said, as well as proposing developing better mechanisms for understanding infection pathways and chemical exposure outcomes.

Hamilton said generally it is time-series data that are needed, because they are useful for understanding seasonality and climate impacts on risk, and they can improve understanding of time scales of hazard persistence and risk. Hamilton also encouraged the sharing of models and code to avoid duplicative effort, as well as more granular data collection. She also suggested bridging the gap between mechanistic and data-driven models using physics-based ML approaches. Lastly, thinking about social factors, she noted the need to better account for subpopulations in risk models. She acknowledged that consumer behavior does not always align with consumer perceptions; thus, it is important to understand the drivers of behavior while also understanding risk acceptability for various populations. What may constitute an acceptable risk for one person or population may be very different for another, she added. She also called for improving understanding of in vivo kinetics using biomarker data in order to better understand interactions between food, nutrients, and contaminants.

Finally, Hamilton also highlighted the role of social media in influencing different food safety perceptions and behaviors, and how that can inform the ability to effectively communicate with different audiences and include them in risk assessments.

Looking Beyond and Working Together

Recounting the history of the field, Janell R. Kause, U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA), shared her key takeaways from workshop discussions and future thoughts. She discussed the massive outbreaks 20 years ago that led to risk-based algorithms and reduced foodborne contamination, and a significant decrease in outbreaks for nearly 15 years. Then cracks began to form in that system, she said, when outbreaks began to be linked to foods not previously implicated in outbreaks. This threat continues to evolve and emerge. She emphasized the need to look beyond spaces “under the lamplight” for potential hazards. She also highlighted the importance of data, saying that more data exists than previously thought, but much of it is not accessible, so multi-sector and multi-agency collaborations are extremely important.

Working together across those sectors in aggregating data can help prioritize efforts and lead to real benefit. But the commitment is important, as we can build all the greatest tools in the world, but without everyone coming to the table to work together, progress will be slow. Thinking toward the future, she again emphasized the need for collaboration, including the harmonization and standardization of data across stakeholders. She echoed calls for a cultural shift across the food system, and cited signs of recent progress. For example, initiatives such as those sponsored by Western Growers are positive indicators, and these types of public–private partnerships facilitate important conversations to advance the field.

In closing, she emphasized the importance of preparing future scientists with a holistic understanding of connections and intersections between the environment, food safety, food security, and nutrition. They should also be equipped with strong analytical skills for data utilization, she argued. While technological advancements will continue to play an important role, true progress in food safety will demand cultural changes and improved collaboration across the system.

DISCUSSION

The discussion portion of the panel focused on a few key areas for the future, including better use and integration of data, practical application of complex models, improved funding and resources, and a focus on vulnerable populations and cumulative risks. Kimberly L. Cook, USDA, emphasized the need to move beyond basic data collection to root cause analysis. She suggested learning from other industries such as aviation, and highlighted opportunities to overlay information from multiple sources and industries to gain deeper insights. Similarly, Hamilton pointed out the

need to better use existing datasets, as well as the need to generate new datasets to answer specific questions.

To encourage more data sharing and improve communication, Kause suggested showing stakeholders how their data are used and what the impact their data could have. In the spirit of collaboration, Davis also challenged the industry community to think about reasons that data sharing should move forward, and just start with what is realistic to do, even if the initial information available is imperfect. “We could talk ourselves out of this very easily,” she said, “but there are a lot of things that can get done.”

Kowalcyk advocated for increased food safety funding and training opportunities, and research, noting that USDA food safety grants, typically $750,000 over 4 years, are substantially smaller than comparable National Science Foundation grants, which are closer to $3 million over 5 years, and this has negatively affected workforce development. “To make a difference here, the research and training funding models in the U.S. will need to change,” she said. Similarly, Kause emphasized the need for—and importance of—a food safety culture change across the entire food system. She added, if the change can be agreed upon, “I think together we will have the energy and will to put the data together.” She highlighted some available National Institutes of Health (NIH) funding for quantitative microbial risk assessment training, and Eric A. Decker, University of Massachusetts Amherst, suggested potential partnerships with NIH’s precision nutrition initiatives.

Vulnerable populations were mentioned throughout workshop discussions, and Nachman raised the question of whether the field is adequately accounting for diverse factors that influence vulnerability to food safety challenges. These could include such things as life stage, comorbidities, genetics, and nutritional status. Hamilton acknowledged that the field is not adequately addressing these factors, particularly in microbial dose–response modeling. Ginsberg also highlighted the importance of considering the increasing prevalence of immunocompromised individuals in the population. When recommendations are heavily influenced by sustainability, cautioned Zagmutt, this has impacts on risks associated with nutrition and protection for vulnerable populations. He suggested incorporating nutrition and sustainability considerations into traditional chemical and microbial risk analysis to ensure that concerns about, for instance, animal product consumption, are not overly restricted for populations in need of those nutrients. Overall, Kause emphasized the importance of continuous improvement, saying that while the final goal may not always be immediately achievable, forward progress should be the target.