Safeguarding the Food Supply: Integrating Diverse Risks, Connecting with Consumers, and Protecting Vulnerable Populations: Proceedings of a Workshop (2025)

Chapter: 2 Nutritional, Economic, and Equity Implications in Food Safety

2

Nutritional, Economic, and Equity Implications in Food Safety

The speakers in the first session, moderated by Kimberly L. Cook, U.S. Department of Agriculture, discussed the potential implications of various food safety hazards, which depend on many factors. A particularly important one is consuming population, as effects may vary based on age, where people live in the world, the types of food they typically consume, and/or how precautions might be taken to reduce the exposure to a hazard. Speakers also reviewed the nutritional and health implications as well as the economic implications of microbial and chemical hazards. The session concluded with a discussion on equity considerations across different hazards and how to think about different subpopulations in food safety hazard identification and guidance.

NUTRITIONAL AND HEALTH IMPLICATIONS OF MICROBIAL AND CHEMICAL HAZARDS

Health Implications of Microbial Hazards

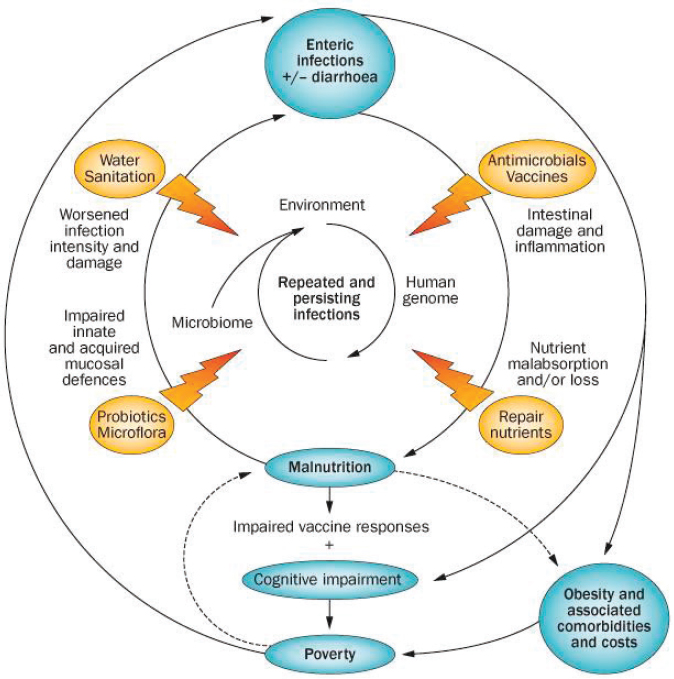

Arie H. Havelaar, University of Florida, presented on the interconnection between food safety and nutrition, emphasizing that “if it’s not safe, it’s not food.” He shared World Health Organization (WHO) data, showing that the global burden of foodborne disease accounts for 33 million healthy life years lost annually, comparable to HIV, malaria, and tuberculosis (Havelaar et al., 2015). There is significant inequity in this burden, he said, as children account for one third of deaths from foodborne illness. And while the poorest 41 percent of the world’s population experiences 53 percent of foodborne

illnesses, they suffer 75 percent of foodborne deaths and 72 percent of the disability-adjusted life years (DALYs). Food safety is intimately related to nutrition, he noted, both affected by the vicious cycles of diseases of poverty (see Figure 2-1), making affected children even more vulnerable to exposures and illnesses.

With bacteria playing such a key role in stunting, as well as chronic inflammation in children, it is important to understand how to intervene in their introduction into the food supply, Havelaar explained. Studies have shown that one of the main sources of children’s exposure is from surrounding animals. For infants, food and breast-feeding (and the surface of the breast) are important pathways, both subject to contamination via the hands of caretakers. Research in Ethiopia demonstrated that Campylobacter

SOURCES: Presented by Arie H. Havelaar on September 4, 2024; Guerrant et al., 2013. Used with permission of Nature Reviews, permission conveyed through Copyright Clearance Center, Inc.

infections, primarily transmitted through chickens, affect up to 90 percent of children in their first year of life, mostly asymptomatically (Deblais et al., 2023). The study emphasized the complex pathogen transmission pathways involving food, breast milk surfaces, and soil. Havelaar emphasized the need for a multidisciplinary approach to address these issues, integrating food safety, nutrition, and water, sanitation, and hygiene interventions, and including behavioral interventions and social sciences expertise.

Shifting to the United States, he acknowledged the foodborne disease burden is lower compared to other parts of the world, but it cannot be ignored. According to WHO data, America has the lowest level of DALYs per capita globally from foodborne illness, said Havelaar, but this is partly because of better access to high-quality health care systems that may provide adequate treatment for serious outcomes and prevent deaths. The WHO data cannot directly be compared to other estimates, such as the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), because of differences in methodology. Importantly, WHO estimates the burden of illness from 31 known hazards, whereas the widely cited CDC estimates also include extrapolations to unknown hazards. Currently, the main pathogens of concern in high-income nations remain Salmonella, Campylobacter, Toxoplasma, norovirus, and Listeria monocytogenes. Looking at the U.S. Healthy People 2030 website,1 he shared that there was a small drop in foodborne illness during the COVID-19 pandemic domestically (and he noted that this trend was apparent in many countries), but this has since seen a resurgence. Food safety challenges are never ending and always changing, said Havelaar, so it is critical to maintain awareness and surveillance of potential threats.

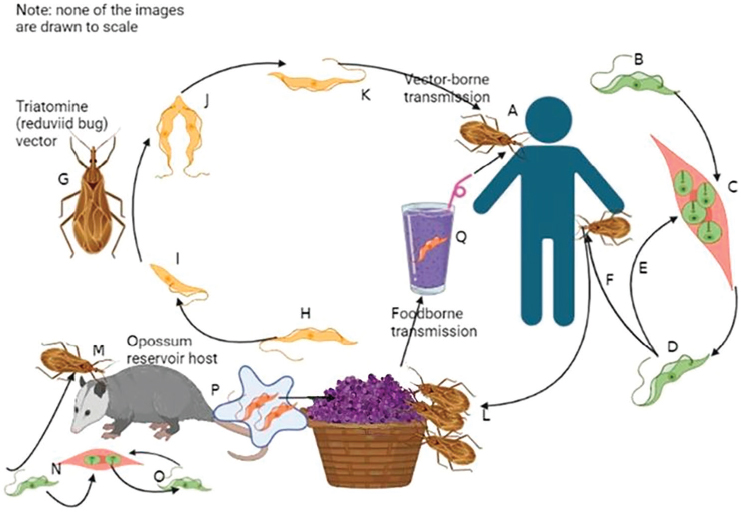

As an example, he referenced Chagas disease—once thought to be a vector-borne disease but now dominantly considered a foodborne disease in endemic countries in Latin America (see Figure 2-2). In 2022, he said, researchers estimated that the United States had approximately 10,000 cases of T. cruzi, the bacteria that causes Chagas disease, that were locally acquired (Irish et al., 2022). Understanding this transmission cycle and the role that foodborne transmission plays will be important in reducing the number of cases.

Lastly, he noted that, while nutrient-dense foods are often the healthiest, they also typically carry the highest risks. Nutrition and food safety should not be thought of as trade-offs, he said; they should be seen as essential companions of healthy foods. Symptomatic and asymptomatic infections with enteric pathogens are increasingly recognized as contributing to malnutrition, and unsafe foods disproportionately affect the vulnerable. While consumers can take precautions, industry bears the responsibility for providing

___________________

1 See https://health.gov/healthypeople/objectives-and-data/browse-objectives/foodborne-illness (accessed September 4, 2024).

SOURCE: Presented by Arie H. Havelaar on September 4, 2024, from Robertson et al., 2024. CC-BY 4.0.

safe food, said Havelaar. He emphasized that while microbial hazards are largely preventable, food safety requires constant vigilance as the challenges continue to evolve. Without continuous surveillance, threats that are not common in the United States, can emerge, reemerge, or make a comeback.

Nutrition and Health Implications of Chemical Hazards

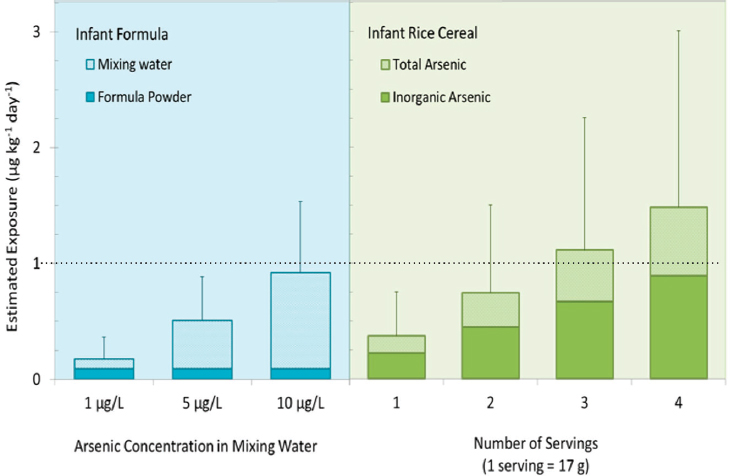

Margaret R. Karagas, Dartmouth Geisel School of Medicine, presented the challenges and opportunities for assessing dietary exposures to chemical contaminants, particularly in vulnerable populations. She shared findings from learning about eating patterns, especially during sensitive periods of gestation and early childhood, emphasizing the importance of timing, mechanisms, and risk modifiers in exposure assessment. Looking at data from the New Hampshire Birth Cohort Study, Karagas shared that they found 80 percent of babies were introduced to rice cereal. Estimated arsenic exposure from consuming three servings of rice cereal a day, she explained, would be roughly equivalent to a child ingesting formula mixed with 10 µg/liter of arsenic in the water (see Figure 2-3) (Carignan et al., 2016). Unrelated to arsenic exposure,

NOTE: 10 µg/liter is the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency maximum contaminant level.

SOURCES: Presented by Margaret R. Karagas on September 4, 2024, adapted from Carignan et al., 2016. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0.

other studies examining rice intake among infants and young children found that earlier introduction of rice cereal was associated with a higher risk of upper and lower respiratory infections (Moroishi et al., 2022).

Karagas shared several studies demonstrating the complex relationships between dietary choices, chemical exposures, and health outcomes, while highlighting the importance of timing and individual variation in exposure responses. A more direct approach to measurement of health outcomes, she explained, is to use biomarkers and such novel techniques as teeth analysis to trace exposures over time, as well as analysis of blood and human milk. These methods can reveal prenatal and early-life exposures to such elements as lead from drinking water per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) exposures during gestation and lactation. Karagas shared her study comparing children who were exclusively breastfed versus those who were formula-fed, finding higher concentrations of barium, lithium, and strontium in the infancy windows of teeth from formula-fed babies (Bauer et al., 2024). Her team’s “dietary-wide association study” using National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) data also identified significant correlations between rice consumption and blood mercury and urinary arsenic levels, and between fish/shellfish consumption and arsenic

and mercury levels (Davis et al., 2014). She also noted that similar associations were found with PFAS concentrations during gestation and lactation.

Karagas emphasized that food is a mixture of nutrients and toxicants. Trials to identify novel toxicant exposures from foods such as seaweed can be useful but are costly and may require long follow-up periods. Rather than waiting for clinical evidence of illness to manifest, she suggested measuring intermediary biomarkers, known to be associated with disease diagnoses, which then can help link exposures to long-term health outcomes more quickly. Karagas underscored the prospects of using national consortia comprised of populations with diverse consumption patterns and exposure risks, and she highlighted approaches that could be used to tease apart the health effects of nutrient and contaminant levels in foods, such as seafood. She concluded by emphasizing the need for multiple research approaches, including national cross-sectional studies, prospective cohorts, biomarkers and experimental designs, and intermediate outcome measures to effectively evaluate the benefits and risks associated with the consumption of specific foods. She emphasized the importance of collaborative research efforts in developing optimal dietary guidelines that balance nutritional benefits with chemical exposure risks.

ECONOMIC IMPLICATIONS OF MICROBIAL AND CHEMICAL HAZARDS

Economic Approaches to Food Safety

Robert L. Scharff, The Ohio State University, presented an overview of economic approaches to food safety, emphasizing three key tasks: estimating the economic burden of illness, understanding incentives, and evaluating interventions. He said economists view food safety through the lens of maximizing social welfare, which encompasses more than just health outcomes and includes people’s values and preferences for risk–benefit trade-offs. It is important to consider both financial costs and the effects on quality of life when calculating economic burden, he noted, as these costs in the United States can vary significantly across states. These include costs to the food industry (regulatory compliance, recalls), households (mortality, medical care, work loss, pain and suffering), and government (surveillance, outbreak response). The cost seen at the national level may not be the same as the costs certain states may encounter, he added.

Presenting data on the economic cost of illnesses associated with leafy green consumption, he said it is as high as $5.3 billion, demonstrating how economic cost estimates can lead to different prioritization of pathogens compared to illness counts alone. To illustrate this point, looking at the number of illnesses as a ranking metric, he said that norovirus, as an

example, ranks highest but becomes less dominant when economic costs are considered, as the illness is not that serious. This potentially affects implementation of intervention strategies.

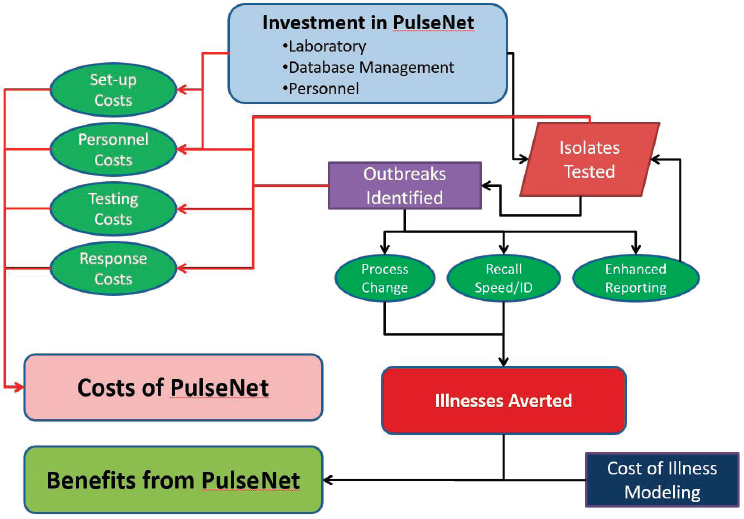

He emphasized the importance of understanding incentives when designing and implementing food safety measures, as market failure can occur in the face of incomplete information. Consumers often cannot identify food risks at the point of consumption. Sometimes indirect measures, such as improved outbreak detection, can drive behavioral change more effectively than direct regulation. For example, Figure 2-4 shows how the PulseNet surveillance system was able to create market-based incentives that could drive private-sector behavior toward better food safety practices, even without direct regulatory requirements. The system was effective because it identified outbreaks that were not previously identified, creating a powerful incentive for private companies to manage food safety in an effort to prevent their implication in an outbreak.

Scharff briefly summarized by saying that economics can provide burden estimates that reflect loss of social welfare, aid in the prioritization of hazards, reveal how incentives shape behavior, and help in the design, implementation, and evaluation of interventions. He emphasized that

SOURCES: Presented by Robert L. Scharff on September 4, 2024, adapted from Scharff et al., 2016. CC-BY-NC-ND.

economic analysis helps determine not just whether interventions improve social welfare, but also which combinations of interventions provide the most benefit for the least cost.

Regulating Chemical Contaminants in the Food Supply

Also presenting on economic considerations, Joanna MacEwan, Genesis Research Group, shared perspectives on regulating chemical contaminants in the food supply. She outlined various routes in which the contaminants enter the food chain: direct introduction via pesticides, environmental presence such as heavy metals, and byproducts of food processing. MacEwan explained the process of setting action levels, or limits, for contaminants, which is done by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA), to identify a level of contamination where the food is considered adulterated and at which point it may take legal action. FDA employs a two-step process: first, it conducts an exposure assessment to establish exposure levels with the action level in place, then it performs an achievability assessment through sampling to determine contaminant distribution in the food supply.

MacEwan illustrated this process using the recent example of lead in baby food, where even low levels of lead exposure can be harmful. In response, in 2021 FDA initiated its Closer to Zero action plan, which identified actions to minimize exposure to toxic elements, including lead. Then in 2023, FDA produced draft action levels, providing guidance for industry that included results of its exposure and achievability analyses for typical foods consumed by babies, such as 20 parts per billion for lead in dry infant cereals with 90 percent achievability. While FDA communicates these standards through guidance documents, such documents lack the force of law. FDA guidance does not require a comprehensive benefit–cost analysis to enforce the action level, she said, similar to those conducted by the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), as a regulation would. Benefit–cost analyses quantify the aggregate change in individual well-being resulting from a policy decision in monetary terms. She detailed how economists evaluate such regulations by considering multiple factors, including the point of introduction in the supply chain, effects on production costs, regional economic effects, consumer health outcomes, and changes in consumer prices.

MacEwan highlighted the challenges of balancing food safety with economic impacts on producers and consumers, noting that regulations can affect farm gate prices,2 production practices, and food prices. There are a

___________________

2 MacEwan defines farm gate prices as the value of the product before transportation and marketing prices, what the farmer sells it for, usually less than the retail price because farmers do not sell directly to consumers.

lot of parameters and inputs that go into estimating the cost and benefits of a policy or regulation intended to mitigate effects of a contaminant. To demonstrate these concepts in practice, MacEwan presented a case study of a proposed California ban on pyrethroids and neonicotinoids in lettuce production (ERA Economics LLC, 2022). The analysis revealed that farming costs would increase by 12 percent because of the need for more expensive, less effective alternative pesticides, with production costs rising by $125–300 per acre. The study projected a corresponding 8.2 percent increase in consumer lettuce prices, with disproportionate effects on lower-income households, where families spend a larger proportion of their income on food. Additionally, the regional economic impact would be substantial, she noted, particularly in agricultural areas already facing economic challenges. The study estimated that each $1 million reduction in farm revenue results in the loss of 15 full-time equivalent farm jobs, reduces local economic activity by $1.09 million, and reduces gross regional sales by $1.53 million. However, the benefits would include a reduction in exposure to the contaminant, an avoidance of the negative effects on health, and avoidance of costs of treatments and care.

MacEwan concluded by emphasizing that while some level of contaminant exposure may be unavoidable, various policy and regulatory tools exist for risk mitigation. She underlined the importance of thorough benefit–cost analysis in policy design, particularly given the complex economic impacts throughout the food supply chain and their potential effects on different populations. The key challenge lies in balancing the need for food safety with economic feasibility and social equity considerations.

EQUITY CONSIDERATIONS

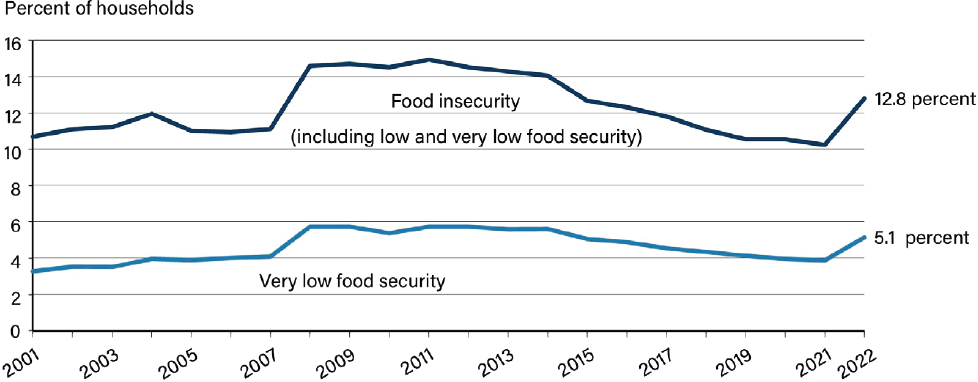

Julie Herbstman, Columbia University, addressed equity considerations at the intersection of food safety and food security, beginning with a foundational definition of food security as universal access to sufficient, safe, and nutritious food. Both food safety and food security have a variety of predictors, but two factors predict both, she noted: poverty and climate change. Recent estimates show that 13 percent of the U.S. population is food insecure, said Herbstman, without much progress made in the last 20 years (see Figure 2-5).

Herbstman examined the limitations of NHANES data in understanding dietary patterns among different population subgroups. Using seafood consumption in pregnant women as an example, she noted the difficulty in understanding the benefit and potential harm of this recommendation, as seafood contains both essential nutrients as well as contaminants. NHANES data show 27 percent of pregnant or lactating women are not eating fish at all, and only 19 percent of women of childbearing age meet

NOTE: For the definitions of food insecurity, low food security, and very low food security, see https://www.ers.usda.gov/topics/food-nutrition-assistance/food-security-in-the-u-s/key-statistics-graphics (accessed September 4, 2024).

SOURCES: Presented by Julie Herbstman on September 4, 2024, from Economic Research Service, 2024.

the recommended two servings of fish per week (NASEM, 2024). However, these patterns vary significantly by ethnicity. The Asian population, though small in the NHANES sample, has much higher consumption rates, she noted, with about 40 percent meeting recommendations.

She also emphasized how NHANES fails to capture certain populations entirely, such as indigenous peoples, who consume 10–25 times more shellfish than the national average and prepare it differently. In addition, the source of where the seafood is caught can make a significant difference, such as subsistence fishermen in Louisiana bayous who may be eating mercury-laden fish they have caught locally, versus those with the means to shop at more expensive stores that provide label information about mercury levels.

Regarding rice consumption and arsenic exposure, Herbstman presented research showing significant ethnic disparities. Asian populations consume approximately twice as much rice as non-Asian populations, with low-income Asian communities consuming 2.5 times more (Sobel et al., 2020). Through the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA) and New York City research, she demonstrated how these consumption patterns correlate with higher urinary arsenic levels, particularly concerning for children who are more vulnerable to arsenic’s neurodevelopmental effects. She emphasized the need for more research to understand consumption patterns in subgroups defined by ethnicity, life stage, and poverty status, calling for approaches to risk assessment and management that are both culturally appropriate and account for notable differences from average consumption patterns.

Lastly, while there is limited data currently, she briefly acknowledged the exacerbating effects of climate change on food safety in her concluding remarks. For example, she cited new data that is under review that indicates that rising temperatures increase the arsenic absorption in rice plants, which has implications for exposure levels and recommended intakes. Rising temperatures can also affect salinity and water temperature, leading to more toxic algal blooms. This can also manifest in increased bacterial contamination after flooding events, disproportionately affecting communities relying on local water sources. Herbstman pointed to the urgent need to understand and address how climate change exacerbates existing inequities in food safety and exposure risks, particularly for vulnerable populations.

DISCUSSION

During the discussion, speakers highlighted the complex interplay between food safety, public health, economic considerations, and environmental challenges, emphasizing balanced, evidence-based approaches that consider both immediate safety concerns and longer-term sustainability goals. Peter Lurie, Center for Science in the Public Interest, raised concerns about FDA’s achievability approach to setting action levels for contaminants. He argued that this approach, which considers what industry can currently achieve, not what could be possible, might not adequately prioritize public health. MacEwan acknowledged this concern and suggested that a more formal benefit–cost analysis during the process of setting action levels could be beneficial.

In response to concerns about NHANES limitations in capturing sub-population data, Herbstman revisited a multitiered approach to filling these gaps, including large consortium studies like the National Institutes of Health (NIH) Environmental Influences on Child Outcomes study, individual cohorts for localized issues, and regional studies. Karagas added that the NIH All of Us program, targeting one million participants, could also provide additional adult and family-focused data.

Another participant inquired about the potential of artificial intelligence (AI) in economic burden analysis. Scharff acknowledged AI’s promise but cautioned against over-reliance, suggesting it should supplement rather than replace traditional methods. Havelaar added that current AI primarily reiterates existing knowledge, rather than generating new knowledge, which can be helpful in identifying what might be missing. Scharff described FDA’s hybrid approach combining traditional risk-based models with AI for inspections as a promising direction.

Lastly, challenges were raised related to environmental damage and adaptation strategies. Scharff emphasized the importance of incentive-based approaches for adaptation, which could be more successful to motivate

countries than top-down approaches. Havelaar discussed the difficulty in applying safety standards from one location to another without thinking critically about risks and benefits. For example, he said many African countries adopt U.S. or European Union standards related to aflatoxin M1 in milk without considering their local context. This particular U.S. standard dates back to the 1970s, is not clearly risk-based, and reflects what was achievable in high-income nations. Worldwide, he explained, there are only about 30 liver cancer cases worldwide attributable to this type of aflatoxin M1 exposure. Yet, even with this low health impact, the adoption of U.S. standards in African countries can lead to significant food waste, job insecurity, and loss of valuable nutrition sources. Havelaar reemphasized the importance of contextual consideration in setting food safety standards and the need to periodically reassess them to ensure they are doing what they are intended to do.