Safeguarding the Food Supply: Integrating Diverse Risks, Connecting with Consumers, and Protecting Vulnerable Populations: Proceedings of a Workshop (2025)

Chapter: 4 National and International Perspectives on Risk Assessment and Tools to Mitigate Risk

4

National and International Perspectives on Risk Assessment and Tools to Mitigate Risk

In the fourth session, moderated by Stéphane Vidry, International Life Sciences Institute, speakers discussed available tools from other countries and the United States that are being used for risk assessment and mitigation. Trade-offs were discussed, as well as the increasing use of and potential for artificial intelligence (AI).

EUROPEAN FOOD SAFETY AUTHORITY APPROACHES FOR RISK–BENEFIT ASSESSMENT

Salomon Sand, Swedish Food Agency, presented approaches proposed by the European Food Safety Authority’s (EFSA’s) guidance on risk–benefit assessment of foods. Most of EFSA’s work is done in response to questions from the European Commission, European Parliament, or member states, he said, but it can also self-task, as it did with a recently published guidance document, released in 2024, which aims to broaden the overall approach to risk–benefit assessment (EFSA Food Safety Committee et al., 2024). Sand emphasized that the guidance “exclusively deals with health risks and benefits” and focuses solely on chemical hazards and nutrients, reserving microbial hazard assessment for future iterations. It represents a significant evolution in food safety assessment, excluding societal and environmental factors. Explaining risk–benefit assessments, Sand said they are relevant when both risks and benefits are clearly associated with the consumption of foods and may differ depending on the level of complexity of the question, in combination with the data and resources available.

He explained various approaches, including ranking methods for the initial prioritization of food components, comparison of exposure to health-based guidance values, and health effect metrics such as disability-adjusted life years (DALYs), which can be used to extend the historical risk–benefit assessments. In Europe, he said, risk–benefit assessments are not as well established as the traditional risk assessment process, but there is room for its future use. Sand also discussed methods for the joint assessment of multiple effects, such as categorical regression and approaches based on severity scoring systems, which could assist in comparing and integrating different health effects.

Sand acknowledged the inherent challenges in conducting these types of risk–benefit assessments, including the need to characterize several relevant effects over a range of potential intakes, differing data on relevant risks and benefits, and trying to compare negative and positive health effects on a common scale to assess trade-offs. It is also difficult to compare different effects on a common scale, especially when dealing with both experimental and epidemiological data. Developed guidance document(s) offer several approaches, ranging from initial ranking to more sophisticated health impact metrics, emphasizing the importance of standardized effect scoring systems. He presented innovative models for combining data across broad health effects that allow for a common scale to compare different health outcomes.

Looking to the future, Sand highlighted the importance of collaboration between risk assessors and managers in selecting weighting approaches. EFSA’s increased emphasis on uncertainty analysis is particularly relevant where data combination adds layers of complexity, he noted. As toxicology moves more toward upstream data collection, new methods may be needed to bridge between traditional approaches and the health impact metrics they seek to characterize.

INNOVATIVE FOOD SAFETY TOOLS TO MITIGATE RISK

Cory Lindgren, Canadian Food Inspection Agency (CFIA), presented on innovative food safety tools employed in Canada that use quantitative risk modeling and machine learning. As a regulatory agency, he said CFIA is dedicated to safeguarding food, animals, and plants to ensure the well-being of Canadians. His office works mainly to estimate emerging risks and trends and conducts modeling work to reduce pathogens with the end goal of modernizing CFIA food inspection programs. Lindgren introduced three new tools or models that CFIA is currently developing, all of which use emerging technologies such as AI and machine learning (ML), analyzed using advanced statistical methods.

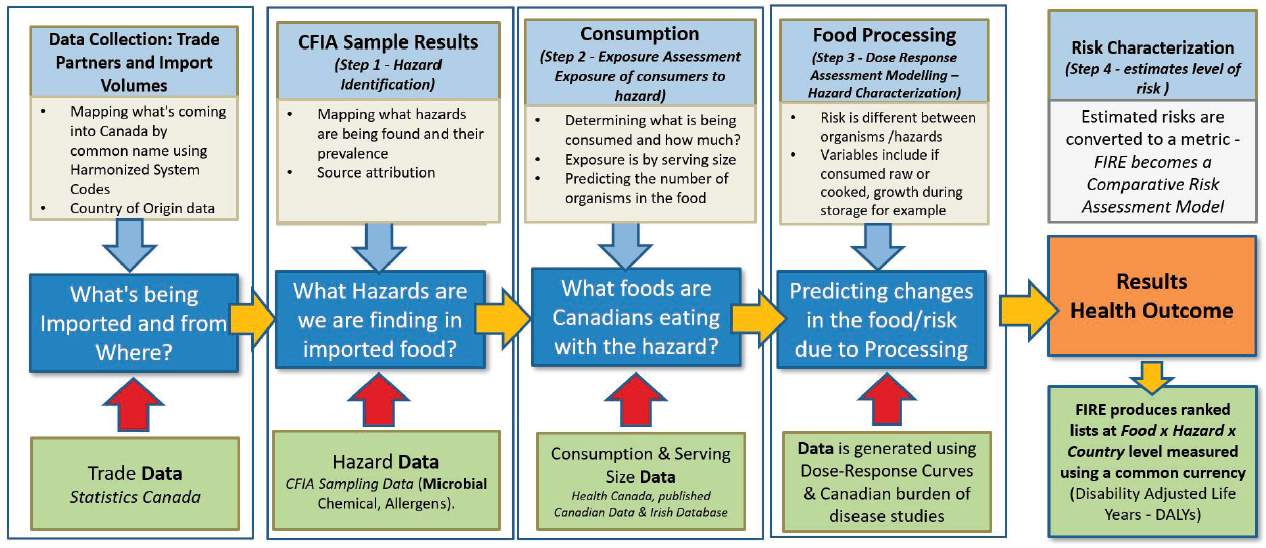

The Food Import Risk Explorer (FIRE) model addresses the need for ranking importing food products based on risk, using DALYs calculated at the food-hazard-country of origin level. In addition to DALYs, he explained the algorithm considers import volumes, and probability of contamination and illness after exposure (see Figure 4-1). This will allow operations and policy colleagues to compare risk across different commodities, he said. The algorithm’s results are captured in a Power BI dashboard (a single-page data visualization) enabling CFIA staff to take a deeper dive into the FIRE data so that they can analyze risks across different dimensions. Initially the FIRE model is focused on microbiological hazards in imported fresh fruit and vegetables, he said. It is being expanded to include fish, seafood, and dairy commodities, as well as chemical hazards.

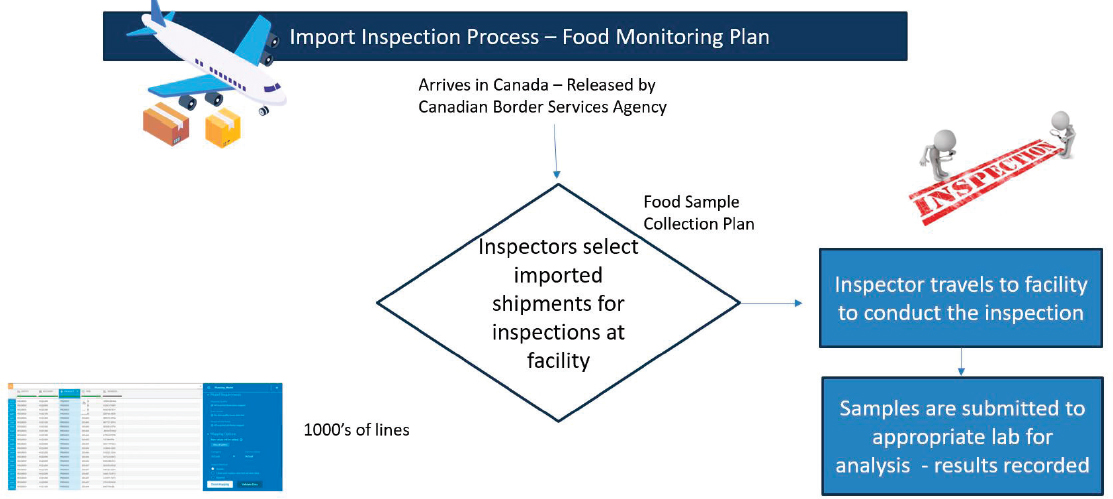

Lindgren also discussed the FISHnet model, which uses AI and ML to assist inspection staff in predicting and preventing risks. It aims to expedite the process of selecting which imported products require inspection from thousands of daily entries based on risk (see Figure 4-2). CFIA is working with the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) to learn from their ML models in this area.

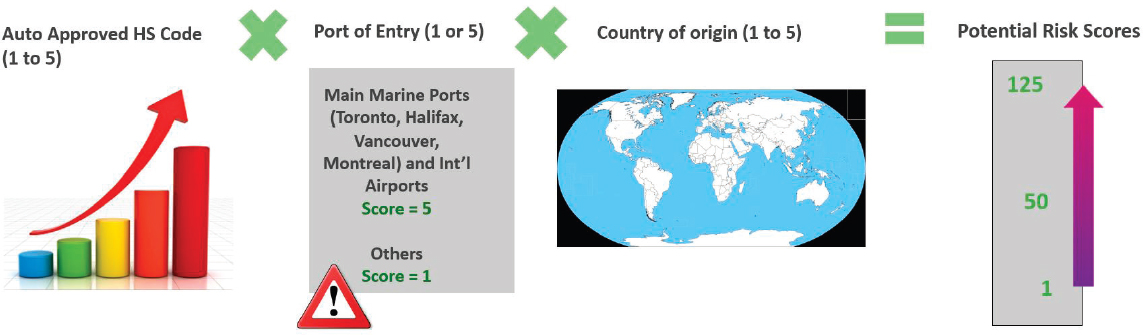

Finally, he shared the details of the Misdeclared Import Surveillance Tool (MIST), which has been operational for a few years and addresses the challenge of misdeclared imports. The MIST is a risk-based predictive screening tool that was created to help prioritize port-of-entry inspections at the border and in bonded warehouses of incoming import shipments at highest risk of containing smuggled, undeclared, or prohibited food products, before they reach the Canadian marketplace. Using algorithmic calculations based on intelligence information, the tool applies a risk-weighted ranking for auto-approved products that do not require CFIA review for release approvals and are, therefore, more likely to be used to bypass Canadian import requirements. While CFIA maintains auto-approved harmonized system codes for trusted importers, some do misuse the codes to import higher-risk items. MIST helps staff prioritize inspections of incoming import shipments through a qualitative risk-based screening approach (see Figure 4-3).

Most importantly, these tools and models will support one another, he added, and are not being developed in silos. They are designed to be interconnected and interactive, with outputs/inputs from one model informing another. For example, he said FIRE’s data on import patterns and sampling efforts can be used to develop more robust sampling plans, which then can also feed into FISHnet’s ML algorithms—collectively moving the organization to a more preventative paradigm. Successful model development and deployment requires extensive teamwork, he said, emphasizing the importance of data sharing and collaboration among different stakeholders to improve food safety efforts.

SOURCE: Presented by Cory Lindgren on September 5, 2024.

SOURCE: Presented by Cory Lindgren on September 5, 2024.

NOTES: CFIA = Canadian Food Inspection Agency, HS = Harmonized System, MIST = Misdeclared Import Surveillance Tool.

SOURCE: Presented by Cory Lindgren on September 5, 2024.

USING MACHINE LEARNING FOR IMPROVED COMPLIANCE TARGETING

Chuck Hassenplug, Human Food Program, FDA, discussed ML for improved compliance targeting in food safety. He repeated how challenging it is having limited resources to inspect large numbers of items, and explained how FDA is using traditional ML techniques rather than advanced AI or deep learning. This choice was deliberate, he noted, as traditional ML can offer more explicable results and complement existing models and human expertise in identifying high-risk food imports.

Hassenplug described the development and implementation of various models targeting specific hazards and operations, such as microbial contamination, seafood hazards, and pesticides. The challenge is substantial, he said, as the food coming into the United States is increasing by roughly 10 percent every year, he added, with limited regulatory resources to inspect and sample incoming shipments. With many different products and continuously evolving players and businesses, there are always a lot of moving pieces, often leading to confusion. ML can help to recognize patterns and support human inspectors, focusing on actionable information as power.

FDA’s current portfolio includes models for microbiological hazards, seafood, pesticides, toxic elements/heavy metals, and facility inspection violations. The modeling process uses extensive FDA datasets, up to 25,000 samples annually, combined with third-party demographic information, and employs Microsoft’s LightGBM boosted tree algorithm. This LightGBM model is able to convert categorical data into numerical variables and handle missing values, Hassenplug explained.

The resulting predictions are highly specific, which allows them to target individual facilities rather than broad categories. He highlighted the importance of model transparency, continuous evaluation, and collaboration with other agencies and stakeholders to improve food safety efforts. Key predictive features of these models include operational size, market entry timing, geographical location, and registration compliance. Analysis across different food categories revealed varying risk profiles, he noted. For example, dietary supplements, cheese, soups, spices, and seafood showed higher prediction rates for violations, while produce, bakery products, and pasta showed lower rates. Geographically, analysis found higher risk profiles in Southeast Asia and parts of Africa, though major importing regions like Mexico showed lower risk profiles.

Hassenplug described the rigorous validation process to assess these models across three phases: in silico testing, with 80/20 training/evaluation split; retrospective testing, including field validation without model implementation; and prospective testing, including actual deployment with human decision-makers. Performance metrics have been promising,

Hassenplug said, with accuracy ranging from 70 to 92 percent, and positive predictive values 2–5 times above the baseline. Over the past fiscal year 2024, models helped identify 175 more violative samples, representing $7.3 million worth of food, demonstrating the potential these approaches have to offer.

By extrapolation and making general assumptions, he estimated that 13.6 million people did not get harmed because of FDA’s implementation of ML and use of these models. Summarizing key lessons, he emphasized that data quality is essential, as accurate registration and manufacturer information can help a model make predictions more accurately. FDA has found how helpful it has been for ML to “shrink the haystack” of samples predicted to be violative, allowing FDA to focus resources on riskier shipments and facilities, though he noted that balance is needed between compliance driven and surveillance sampling. Using the ML results at the supply chain level helps FDA to identify problem shipments and remove them from the market before an outbreak or recall even occurs. Overall, the goal is to move toward “smart” regulation, working and communicating across the public, academia, and industry in a collaborative manner.

DISCUSSION

The discussion on international perspectives focused on modeling systems and implementation, international collaboration and risk–benefit analysis, and consumer impact. In response to concerns about model transparency potentially enabling gaming of the system, Hassenplug acknowledged the risk but noted that suspicious pattern changes are risk signals themselves. FDA maintains tight control over algorithms while aiming for industry cooperation in the use of its PREDICT model. This should also be balanced with data sensitivity, especially when used to inform consumer choices, he added. Kowalcyk raised concerns about potential bias in AI and ML models, questioning the absence of vulnerable populations as a factor. Hassenplug clarified that the FDA model predicts violation probability, not absolute risk, but he noted the importance of balancing what is fed into the models to avoid perpetuating existing biases. He also added that vulnerable populations are considered post analysis. Lindgren also emphasized CFIA’s use of supervised ML algorithms rather than broader AI.

Davis highlighted the need for practical applications of these models in the produce industry, emphasizing that the goal is not to have growers perform complex analyses but to change behaviors based on risk assessments. She suggested an end goal of having a risk model similar to the Waze app (a satellite navigation software that incorporates user-submitted traffic information) used for traffic, that could flag a red zone in a farmer’s process that could prompt a change in behavior. Janell R. Kause, U.S. Department

of Agriculture, emphasized the importance of incremental improvements in food safety practices, even if perfect solutions are not immediately achievable.

A participant asked about what steps countries should take when exploring risk–benefit analysis for regulatory and policy decisions. Sand responded that there is significant variation in progress from different countries, though, for example, Denmark has been a leader in implementing risk–benefit analysis. He noted a cyclical pattern in European interest in risk–benefit analysis, with high interest nearly 10 years ago followed by a decline, with interest now resurging again. Francisco J. Zagmutt, EpiX Analytics, also asked about quantifying evidence quality, especially when different types of evidence are available for risks versus benefits. Sand agreed this is a challenge, noting that current assessments have not fully addressed evidence quality differences.

A participant asked about consumer access to food safety data, suggesting FDA and CFIA modeling results could help consumers make informed choices about products and suppliers. Lindgren replied that current modeling remains internal to agency operations at this point in time, owing to regulatory constraints and data protection requirements. Both agencies indicated that sharing data with the public would require careful consideration of disclosure limitations and protected information.

This page intentionally left blank.