The Future of Commuter Rail in North America (2025)

Chapter: 7 Implementation Strategies

CHAPTER 7

Implementation Strategies

The commuter rail industry consists of 28 providers in North America. This research reveals a tremendous diversity of services, markets, operating models, built environments, and governance structures that supports each of these providers. At the extremes, some rail services have been operating for more than 150 years, while more than half of the providers launched service within the last 35 years. Some are funded and governed by state agencies; others are wholly local entities. Many providers offer all-day bi-directional timetables, while others are exclusively peak oriented. Most providers do not neatly fit into one category or another and are a blend of these features. In most cases, operating support comes from both state and local sources, operating patterns are peak focused but have some off-peak trips, and providers have a few decades of experience to build on.

When looking to the future of commuter rail, it is clear there is no one-size-fits-all path forward. Each provider and each region will need to examine its travel markets, service, and infrastructure to identify a responsible and pragmatic approach to address changing market conditions. The strategies providers can take in the short, medium, and long term will vary. However, discussions with dozens of leaders and experts within the field can reveal emerging practices and trends addressing the ridership, funding, and service challenges the industry faces.

This section aims to help staff and leadership answer some of the following questions:

- Mobility goals. How do commuter rail services fit into the regional mobility goals of advancing economic opportunity, travel needs, and sustainability?

- Travel markets. How have travel markets changed, and which markets can commuter railways serve?

- Service patterns. How do service patterns affect market capture and ridership?

- Fare policy. What are best practices for structuring fare policy that responds to new commuting patterns and travel markets?

- Passenger information and marketing. What are the best ways to communicate passenger information and marketing of the system?

- Operational efficiency. How can providers improve operational efficiency to make their services more cost-effective?

- Funding. How can agencies raise funds to supplement lost fare revenues?

- Coordination. How can commuter rail providers collaborate and coordinate with other transit providers to expand markets and increase revenues?

- Public policy and governance. What public policy and governance changes need to be in place to help better serve transportation markets, including overcoming challenges for commuter railroads that operate on host railroads?

The following best practices are a summary of strategies documented in the research contained in this report:

Short-term implementation strategies

- Develop a strategic planning initiative

- Review the travel market along commuter rail corridors

- Initiate a timetabling process to evaluate service, costs, and capacity; as part of this effort, develop a long-term strategic timetable as a target

- Enhance current service that works toward the long-term strategic timetable

- Use the recovery period as a time to reevaluate fares and revise the fare structure with input from internal and external stakeholders

- Identify and implement cost-saving measures

- Create marketing materials and strategies to bring customers to the service

- Set up a TOD unit with the goal of transforming underutilized land near stations

Medium-term implementation strategies

- Release a strategic plan for the region

- Develop fare-sharing agreements with other agencies/divisions

- Implement new timetables as infrastructure becomes ready to support improved services

- Implement cost-saving measures

- Create a governance strategy

Long-term implementation strategies

- Develop new regional governance models

- Expand capacity where needed

- Secure long-term and consistent funding

- Electrify or implement new technology when warranted to meet environmental goals

- Develop existing land around stations to encourage ridership growth

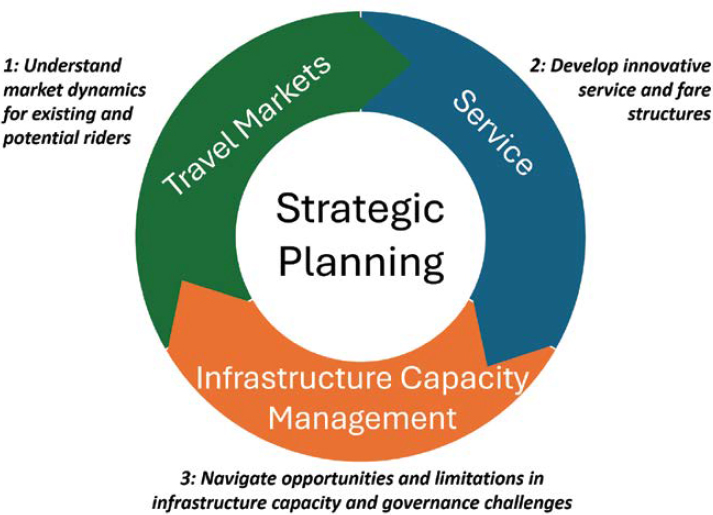

This research also reveals that providers implementing the short-, medium-, and long-term strategies use an iterative process, as shown in Figure 22. Strategic planning is setting the course for the commuter rail service in the long run, developing regional goals, and seeing how commuter rail can fit those. Developing specific strategies for the future of commuter rail involves an

iterative process that includes evaluating markets, designing timetables to meet those markets, assessing how to implement the service on the infrastructure, and then revisiting the market and timetable assumptions based on capacity constraints and funding realities in the short, medium, and long terms.

To chart the future of commuter rail in North America, it is important to start with a clear understanding of goals. This does not necessarily mean putting the mode first. It is vital to first understand what broad mobility goals a region has, then determine the role of commuter rail in achieving those goals (Plaskon, Trainor, and Grant 2011). This section includes a discussion of regional transit goals, best practices for how to set them, and how to address commuter rail or regional rail systems within that context. In doing so, transit planners and leaders need to be prepared to answer tough questions about commuter rail service changes, fare policy, and institutional governance to tackle the transportation goals established in each region. Understanding the goals and the current travel market for commuter rail services across the United States will be the foundation for charting an effective future.

Fundamentally, each region needs to ask questions about

- What places and people need to be connected,

- What service levels are needed to connect them, and

- How the commuter rail system interfaces with other modes of transit.

That approach differs from an infrastructure-led or mode-led goal-setting approach that sets initial goals around increasing speeds, expanding capacity, and cutting costs without first thinking of the specific transportation outcomes desired in the region. Furthermore, the goal of commuter rail should not be necessarily what is best for the commuter rail provider, but what is best for the public.

Given the state of the commuter rail industry today in North America, forming a clear set of goals to bring commuter rail providers out of their current crisis is of paramount importance. Every provider knows its own local context best and will have its own path out of its current post-COVID ridership, but the fundamental practice of forming a long-term plan with effective, achievable goals and understanding the practices likely to lead to a successful implementation of those goals will be universally important.

7.1 Understanding the Addressable Markets for Commuter Rail

An important step in charting the future of a commuter rail service is understanding the potential market for trips. Commuter rail cannot expect to capture all trips in a corridor, or even a majority of trips. In fact, high-frequency heavy-rail rapid transit systems with dense development along a corridor will typically only capture 30 to 40 percent of all travel (WMATA 2021). Commuter or regional rail services, with lower frequencies, will capture less. However, understanding where and at what times people are traveling can help providers tailor a strategy for service and infrastructure that can capture a greater share.

This research shows that the travel market has shifted since 2019. While ridership on commuter rail systems has overall declined, overall travel has remained stable or increased. Analysis of travel data from several commuter rail markets in North America reveals the following trends:

- On typical weekdays, there are still significant morning and evening peaks, but those peaks are less strong than they were before 2020.

- Weekday travel markets have grown during the midday and evening hours, with homeward-bound peak travel extending to as late as 8:00 or 9:00 p.m.

- Weekday travel on commuter rail is much greater on Tuesdays, Wednesdays, and Thursdays.

- Weekend rail travel has grown significantly, although it is not as strong as rail travel on a typical weekday.

- Weekend travel has shifted more toward evening hours than it was before 2020.

While the National Transit Database and other data sources do not report ridership by the day of the week, these findings are backed up by interviews conducted as part of this research. Every agency that offers weekend service reported the largest amount of growth coming on the weekend. Additionally, MBTA Commuter Rail, Metra, Caltrain, and Metrolink all suggested that they had significant growth during the weekday off peak. Every railroad consulted noted that ridership is not as strong on Monday and Friday as during the middle of the week.

For many commuter rail service providers, the peak commute market is still the core of their ridership in total numbers. Yet it is this market that has seen the slowest return to pre-pandemic ridership levels. It is increasingly clear that the traditional commute is not going to return to what it was before 2020. Meanwhile, for providers that offer it, off-peak, weekend, and non-downtown-bound trips have returned to a much greater extent. Provider representatives also cited non-downtown locations as drivers of ridership, including stations with new TOD and airports, for both workers and airline passengers.

The Los Angeles Metrolink case study shows how an evaluation of travel market data can show where potential markets are and build the case for a schedule modification. Metrolink’s schedule change did not include a ridership prediction or demand model, but it did include a relatively straightforward assessment of the broader market near its stations and along its routes. In particular, Metrolink found that in a polycentric region like Los Angeles, strong travel demand continued throughout the day and was not necessarily focused on downtown Los Angeles. Similarly, providers can survey current and potential future riders to determine when and where they would prefer to see service changed to address their future travel. In a 2024 survey of MARC riders, the agency found that most current and potential riders desired more off-peak and weekend service than anything else from the provider.

7.2 Altering Service to Address the Travel Market

Based on the market analysis, commuter rail providers can tailor their service to better attract riders. The timetable is commuter rail’s product and the fare structure is the price, so emphasizing and marketing these elements are fundamental to success. Assessing commuter rail service involves looking at not only the market analysis, but also the mobility goals for the region and the current ridership on the network. Providers also need to understand the different effects of the service on cost efficiency and funding.

Service Timetable

While most commuter rail providers are operating timetables similar to their pre-COVID operations or are making cuts when needed, some providers, including but not limited to MBTA, Metra, Metrolink, UTA, and GO Transit, have made or are in the process of making significant additions to their timetables. The new timetables are built around regular, often hourly, service all day, every day on most or all lines.

This regional rail model is strongly correlated with ridership recovery and growth. Of all the legacy systems, MBTA Commuter Rail is the only one near its pre-COVID ridership levels. This research indicates that this fact is largely because MBTA has reoriented its timetables to provide regular service throughout the day. Similarly, Tri-Rail in Miami has exceeded its pre-COVID ridership in part because it already had robust off-peak and weekend schedules ready to attract new markets.

Systems with multiple lines radiating out of a central hub, such as Metrolink in Los Angeles, are using their timetable changes to develop pulsed schedules that facilitate transfers between lines. A pulsed schedule is one with services timed to stop at a single station, usually the hub of the network, at or around the same time, to allow for anywhere-to-anywhere transfers at a single point. This option can enable more trips across the network, rather than concentrating markets to a single corridor in polycentric regions. While it is too early to show how many travelers will take advantage of this option in Los Angeles, it is a relatively simple change to the operating pattern that has the potential to capture significantly more trips.

However, a regional rail operating model is not a guarantee of success, nor does it work in all markets or for all regions. Despite many providers reporting significant growth in off-peak and weekend services, most of their ridership still travels during the traditional peak times. Other railroads, particularly many of the newer systems, serve park-and-ride lots in suburban areas that have little or no existing development. All-day service to these areas would not necessarily attract any new riders. CTDOT is addressing this matter in part with a proactive TOD program utilizing underused land nearby stations.

Commuter railroad providers in the New York City region shared struggles with balancing the desire to capture more off-peak markets with limits on infrastructure and rolling stock capacity. Ridership has largely recovered on New York’s commuter railroads during the peak, but only on Tuesdays, Wednesdays, and Thursdays. If providers were to spread some of the service from the peak to other parts of the day, it would leave peak commuters at crush loads. At worst, the New York City railroads would be passing up some peak riders because of reduced passenger capacity. If regional goals continue to focus on serving the commute trips and funding is not available for off-peak capacity, then the providers might not have additional options.

Regardless, a market assessment should first and foremost cause commuter rail providers to reassess their operating model and explore different ways to attract potential markets. Evidence from providers that have redone their schedules indicates most have ridership over capacity during peak times and could benefit from spreading those frequencies throughout the day. Weekend service also appears to be an area for growth for many agencies: For example, MBTA Commuter Rail is reporting more than 200 percent growth in weekend ridership.122 Regular repeating patterns, even for hourly service, are also associated with ridership growth, rather than timetables with inconsistent headways.

Providers should also note that a wholesale change to the schedule is different from the standard adjustments that most operations staff are used to. Investing in operational readiness, as Utah is doing with the FrontRunner service, can refine the new timetable to make it operationally sound and ensure its rollout is smooth. First impressions are important when selling a product, and putting the best foot forward will be critical to the industry reinventing itself.

Fares

The large provision of federal COVID-19 relief funding for commuter rail operations in the United States and Canada allowed for some experimentation by commuter rail providers. The packages passed in 2020 and 2021 provided several years of operating support for agencies, with length depending on the formulas devised by Congress and Parliament and their financial structure. Nevertheless, in all cases, the flexibility of the funding, along with its magnitude, provided the opportunity to test new service patterns and try fare promotions. Interviewees with staff at commuter rail providers cited this opportunity as an area of recent success.

All commuter rail providers interviewed for this research project mentioned some experimentation with fare policies, offering weekend discounts, free fares, or other promotions to win

back riders. Providers with reduced or simplified fares generally saw ridership increases during those periods of reduced fares, which then returned to normal levels when the fares reverted. While providers suggested that reduced fares increased ridership, they did not suggest that low fares were sustainable or effective in the long term.

In the case of Metra, the COVID-related disruptions allowed staff to reform and simplify the fare structure. Metra engaged the riding public and its workforce to develop a new policy, reducing the number of zones and fare products it offered. Metra also showed that some of the traditional fare products, such as the full-priced monthly pass, are less useful for the current market. Whereas the previous monthly pass was priced to target commuters using the system 4 to 5 days per week, Metra had to revise prices to reflect the reality that most commuters were only using the system 2 to 3 days per week. This change will not bring in the same amount of revenue as before, but it is also an opportunity to provide more day passes or non-downtown products that can target a new travel market.

However, as the COVID-19 relief funding runs out, the looming fiscal cliff poses a challenge for the industry, and how each region addresses it depends on its organizational structure and local funding support. New policies that target fares as a way to close fiscal challenges are not likely to succeed, as large fare increases could further depress a smaller market.

While providers offered fare promotions on their services, relatively little progress was made on the regional coordination of fares. Most of the region interviewees have different fare structures and media for their commuter rail lines than the local buses or trains. Interviewees recognized the need for coordination of service, fares, and customer information between commuter rail providers and local transit agencies.

Along with their service, commuter rail providers can look strategically at their fare policy that adapts to the new normal. Zone-based fare systems are likely to remain, consistent with revised structures in locations like Chicago as well as in other countries. However, fewer zones and simpler products can help reduce barriers to new riders who can take advantage of the systems. Further, providers should consider the benefits of better integration with local bus and urban rail networks. In some instances, this integration requires coordination and revenue sharing with other providers, and evidence from integrated networks, such as in Germany, shows that this practice strongly encourages use.

Passenger Information, Marketing, and Messaging

Consistent with all interviewees and reviews of commuter rail systems across North America, representatives shared that new travel patterns have created a completely new user base for the system. While many riders have stopped using commuter rail for regular commuting, many more have started using the network. VRE and MBTA Commuter Rail, for example, reported that many of their current riders are new to the system, having started using it within the past 5 years. This new customer base represents an opportunity for the industry to rebrand and remarket itself.

Given a large percentage of new riders, passenger information should be geared toward these riders, who might not be familiar with how the system operates. Many people interviewed as part of this research project suggested better marketing efforts could attract even more riders, particularly because many people have never used commuter rail and might not know that it can take them to destinations throughout the region or to locations not associated with their commute.

For decades, regular, 5-day-a-week riders have represented the core of a commuter rail system’s riders. However, occasional riders represent a significant opportunity for growth, and their information and messaging needs are different. Expanding information and making these people comfortable with the system could be a large potential market.

TOD

Commuter railroads serve a diverse range of stations. A single line can include stations at dense, large downtown areas in major North American cities, historic suburban town centers, and park-and-ride lots with spaces for dozens or hundreds of cars. With less emphasis on downtown commutes, commuter rail can enhance its role in the region by encouraging development at stations.

An emerging practice is to set up a TOD unit within the agency focused on establishing relationships with communities, encouraging support for local TOD, and developing agency-owned land. Parking lots and unused land adjacent to stations represent the largest opportunities for TOD. If the provider owns the land, retaining ownership and leasing it to a developer can create new revenue streams to support operations.

Cost Management

Expanded service and simpler fares are great ways to attract commuter rail riders, but they can be expensive to operate. Commuter rail providers can look for ways to increase the efficiency of their own operations. This research revealed several ways that agencies are exploring options to reduce their operating costs.

The traditional model of peak-oriented service involves several trainsets arriving in the city core and parking until the evening commute. If there is no midday service, this means that a trainset only makes one round trip per day, and the crew only operates one round trip per day, often passing the midday in a hotel room. While this service plan was necessary to serve high-demand downtown office markets, it was not necessarily efficient from a cost perspective.

For providers that can spread service throughout more of the day, this service plan offers better equipment utilization and crew utilization. Metrolink was able to expand service by 23 percent using fewer trainsets, which will save on maintenance costs associated with that equipment. Similarly, crews can be more productive throughout the day, reducing unit costs of operating the service.

Fare policy also represents a future area for cost savings. Many commuter rail services rely on multiple on-board crew members to check and collect fares from riders. Simplified fare structures can make that process faster, potentially reducing staffing. Further efforts to eliminate on-board cash sales can cut on-board and back-office staff.

Despite opportunities for cost savings, in most conversations with practitioners and experts, cost-saving measures were not a priority initiative. COVID-relief funding has not pushed providers to grapple with dramatic declines in fare revenues and cost increases associated with inflation. Even initiatives such as Caltrain’s electrification did not yield energy cost savings. This could represent an area for future research and more insights to rethink staffing, equipment, and other operational costs to make the services more efficient and cost competitive.

Funding

At the time of this writing, most commuter rail providers in North America are only starting to grapple with their coming funding gaps as COVID-relief funds run out. No provider suggested that new federal funding was anticipated for future operating expenses. Without dramatic cuts in service or reduction in operating costs, most will need to secure additional funds from their state and local governments. No practitioner or expert interviewed as part of this research project expected additional operating funds to come from the federal government.

Commuter rail is particularly vulnerable to the fiscal cliff when COVID-relief funds run out and leadership is faced with the trade-off of securing more funding or cutting service. Providers

covered on average approximately 50 percent of their operating costs from fare revenue, but that number has declined dramatically with the loss of regular commuters. Even providers that always had lower farebox recovery ratios are facing issues because wages, fuel, and other costs have increased significantly over the past 5 years with inflation.

Some providers have started to address the issue. For example, Metrolink was able to secure more than $14 million in additional funding from its board for expanded service. The governor of Pennsylvania redirected state highway funds to SEPTA, which operates the regional rail system in and around Philadelphia. However, most agencies admitted they have no concrete proposal to secure new funding.

The good news is that many local and state governments see value in their commuter rail networks and want to see them succeed. Taking steps now to increase ridership can demonstrate value.

7.3 Managing Infrastructure Capacity

If capacity were endless, changing timetables and adding new commuter rail service would be simple. However, railroad capacity is finite, and, in some cases, it is shared with freight carriers and other passenger rail operators. In addition, maintenance and rehabilitation efforts periodically limit the supply of railroad capacity, posing greater challenges for railroads wanting to offer more service throughout the day.

While commuter railroad providers could expand capacity where it is needed to meet their new needs, it would be expensive to do so. The United States and Canada have some of the highest-cost infrastructure projects in the world, particularly for passenger rail projects. Long timelines and high costs mean providers need to be judicious concerning their infrastructure expenditures, particularly when it comes to capacity expansion or extensions of lines (Schank et al. 2015).

Existing funding opportunities at the federal level could create some additional capacity for commuter rail service. The 2021 Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act in the United States provided billions of dollars to intercity passenger rail and urban transit systems for capital projects. However, most of this funding has already been allocated.

The commuter rail providers able to make significant schedule changes already own their rights-of-way, providing greater flexibility than those that must operate on host railroads. Most commuter rail providers in North America and the lines on which they operate own and control most of their infrastructure. This is a large advantage and can lead any coordination on capacity management approaches. Interviewees for this research project mentioned the following obstacles to changing their operating patterns:

- Restrictive trackage rights or purchase-of-service agreements can limit the hours of commuter rail operation or restrict them to pre-negotiated slots,

- Rail corridors at or near capacity would require expensive infrastructure to increase capacity,

- Unpredictable rail services operated by the host railroad can make regular commuter rail timetables difficult to operate, and

- Lack of understanding of the actual supply and demands on host railroads creates a dynamic in which they expend large sums for trackage rights and capital improvements with host railroads to allow more passenger service on the shared line.123

Agreements with host railroads can prevent commuter rail providers from quickly implementing additional or modified service in response to market demand. The financial strain, coupled with an inability to adequately serve the regional travel market, severely hampers the financial and operational success of commuter rail providers.

A strategy used by German regional rail counterparts is a strategic capacity management approach that evaluates capacity supply and demands by commuter rail operators and maintenance teams. This evaluation requires a timetabling process, operational readiness approaches, and operational discipline to use the capacity effectively by sticking to the timetable. The infrastructure owner uses an iterative process, so when a region evaluates its travel markets, assesses its operations, then plans its capacity, it uses these inputs to revisit the market analysis to see whether the additional capacity consumption is worth serving the market it intends to address. North American commuter rail providers rethinking their service timetables are starting to employ similar approaches.

Governance of commuter rail providers also comes into play for capacity management. Providers that do not own their tracks or are subject to restrictive agreements could take the opportunity to purchase lines or redo their agreements. Also, potential through-running or cross-town commuter rail services in Chicago, New York, and Washington, DC, could use existing infrastructure with minimal investment. However, the effectiveness of that service over rail segments with limited capacity needs careful evaluation in the context of interagency agreements, fragmented ownership, and diverse governing agencies. Union agreements, equipment compatibility, and funding agreements could all be examined from a governance perspective. This is going to vary for each organization, but necessary governance modifications need to be on the table when addressing the future of commuter rail.

7.4 Future Research Needs

While the findings of this report have contributed to advancing knowledge and resolving certain questions, they have also highlighted gaps and limitations that must be addressed in future work. As research progresses in identifying and charting the future of commuter rail in North America, it is essential to identify areas that warrant further investigation to deepen understanding, address emerging challenges, and refine practical applications.

The following are areas for future research, informed by the results and limitations of this report, as well as the broader context of existing literature. By targeting these areas, future efforts can build on the current foundation, foster innovation, and promote evidence-based advancements that benefit commuter rail providers, as well as regional mobility overall. Each of these topics was discussed in this report but lacked sufficient best practices and warrant further investigation:

- Reduction of commuter rail operational costs. While several examples included in this research show how a regional rail operating model can increase equipment and crew efficiencies, provider representatives cited growing costs as a major future concern. On-board staff levels, better maintenance practices, and more efficient equipment might be targets for greater cost efficiencies. More research is needed to quantify these elements, compare operators, and suggest which could yield substantive productivity benefits to the industry.

- Customer information and ease of use. This research found that large portions of post-2020 ridership are occasional users new to commuter rail. Infrequent and new riders need clear information to help them navigate the system. For example, with some exceptions, the research also found that North America is unique among its international peers in naming its commuter rail lines after suburban destinations (“Fitchburg Line”), a previous private owner (“Rock Island”), or other branded names (“Sounder”). In other countries, lines tend to be lettered or numbered and consistently named across geographies. Future research could investigate how customer information and system naming could affect ridership and ease of use for current and future customers, including whether and how previous research on the topic for transit generally applies to commuter rail specifically.

- Land use coordination. The CTDOT case study showed how a commuter rail provider is directly affecting land use policy near stations. The case pointed to increased ridership and potential lease revenue from recent development, indicating TOD could be a ridership and revenue driver for more commuter rail systems. More detail and examples are needed to understand how to integrate commuter rail planning with local land use, particularly given the large suburban park-and-ride lots. Future research on the topic could reveal the implications of coordinating existing and future commuter rail or regional rail services with land use to enable greater ridership and more consistent use.

- First-mile/last-mile connections. Related to the land use research, more information is needed to better understand how modern travel markets access commuter rail stations in urban and suburban areas. Data uncovering current and desired access patterns for automobile, public transit connections, walking, and biking could help commuter rail providers better plan their stations and the surrounding land use.

- Funding and governance. Thanks to federal operational support in the United States and Canada as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic, most commuter rail providers have not yet had to raise significant funds, make large service cuts, or both. However, the industry recognizes that money will run out (see Sections 4.2 and 7.2). Various proposals exist, but no consensus has emerged about how to best tackle the funding problem and which funding sources make the most sense in the long term. Related, new funding sources need to be evaluated through the lens of governance, potentially as a way to include new funders in decisions and create more opportunities to increase ridership and save costs. More research is needed to suggest better ways to tackle governance and funding challenges.

- Considerations for the development of new regional rail systems. The period from 1989 until the COVID-19 pandemic demonstrated the appetite for new commuter rail systems around North America. Post-pandemic, while travel patterns have changed, the demand for travel remains. Many major cities in the United States and Canada are well suited to regional rail but have not yet developed such a system. New regional rail systems would have the benefit of learning lessons from current commuter rail providers and would help demonstrate the continued demand for rail as an integral part of the solution to regional mobility challenges.

This research acknowledges that the term commuter rail encompasses a wide range of providers that are sometimes on completely different scales. For example, some providers are relatively small organizations in their region and have recovered only a fraction of their pre-COVID ridership, leaving doubts about whether even dramatic timetable changes would make their services financially viable in the long run. On the other hand, the three commuter railroads serving the tri-state New York City region carry more riders than the other 25 North American providers combined. Their role in regional mobility is not contested, but how they handle high loads only 3 days per week while addressing additional travel markets is not well understood. Specific research targeting these niche regional issues could be helpful in creating more sustainable solutions for different types of agencies.