Review of Evidence on Alcohol and Health (2025)

Chapter: 6 Cardiovascular Disease

6

Cardiovascular Disease

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) persists as the leading cause of death in the United States (Martin et al., 2024). CVD includes “heart attack” or myocardial infarction (MI) and stroke; these two conditions are the major CVD outcomes associated with significant levels of morbidity and mortality. Despite advances in biomedical research leading to new treatments, the societal burden of CVD remains enormous (Dunbar et al., 2018; GBD 2021 Causes of Death Collaborators, 2024; Luengo-Fernandez et al., 2023; Zhang et al., 2023), and there is a continuing need to address modifiable risk factors for CVD to mitigate its burden.

An American suffers an MI every 40 seconds, based on the American Heart Association statistics (Martin et al., 2024), with approximately 605,000 MIs per year (Martin et al., 2024). Every year, about 800,000 Americans suffer a stroke (87 percent ischemic and 10 percent hemorrhagic stroke) (Martin et al., 2024). Coronary heart disease and stroke are the first and fifth leading causes of death in the United States, respectively. It is well recognized that modifiable lifestyle factors, including alcohol consumption, may influence the risk of MI and stroke. While heavy alcohol consumption has been associated with a higher risk of MI (Song et al., 2018) and hemorrhagic stroke (Zhong et al., 2022), prior observational studies have suggested that moderate alcohol consumption is associated with a lower risk of CVD (Ding et al., 2021; Luceron-Lucas-Torres et al., 2023; Song et al., 2018). A subset of studies examined associations of moderate alcohol consumption—with the risk of MI, stroke, and CVD death—with particular care to include people who never consumed alcohol as the reference group. The commissioned systematic review studied the association of moderate

alcohol consumption, compared to never consuming alcohol, on the risk of MI, stroke, and CVD death using studies published from January 2010 through February 2024.

CHOICE OF CVD OUTCOMES

This chapter assesses the association of moderate alcohol consumption versus no alcohol consumption with the risk of experiencing a major adverse cardiovascular event (MACE-3), which includes the three primary outcomes of MI, stroke, and cardiovascular death (Ridker et al., 2005). Unlike MI and stroke, which clinicians diagnose with high accuracy, angina pectoris (another type of CVD) is a less definitive outcome given its subjective nature and the fact that revascularization to treat it may be elective. Accordingly, major randomized controlled trials (RCTs) of CVD treatments use MACE-3 as the primary outcome. While trials of CVD treatment may study a combined outcome based on the three major types of CVD events, we studied each of the three outcomes separately.

BIOLOGICAL PLAUSIBILITY

Several biologic mechanisms potentially explain how moderate alcohol consumption plays a role in reducing the risk of CVD, including the ability of alcohol to (1) increase high density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol and apolipoprotein A-1 (Camargo et al., 1985; Chiva-Blanch et al., 2015; Gepner et al., 2015; Masarei et al., 1986); (2) inhibit platelet aggregation (Umar et al., 2005; Zhang et al., 2000) and inflammation (Chiva-Blanch et al., 2015; Fragopoulou et al., 2021; Sierksma et al., 2002); (3) reduce fibrinogen (Chiva-Blanch et al., 2015; Sierksma et al., 2002; Stote et al., 2016) and increase plasminogen activator inhibiting factor 1 (Stote et al., 2016); and (4) favorably affect markers of glycemic control (Gepner et al., 2015), all of which are risk factors for MACE-3.

These biological mechanisms, which were originally proposed in observational studies, have also been confirmed in dozens of short-term RCTs over the past 40 years. For example, systematic reviews of RCT data have demonstrated that moderate drinking favorably affects HDL cholesterol, low density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol, and apolipoprotein A-1 (Brien et al., 2011; Huang et al., 2017; Spaggiari et al., 2020); fibrinogen (Brien et al., 2011; Huang et al., 2017); interleukin-6 (Huang et al., 2017); and glucose control (Schrieks et al., 2015). While each of these established effects is likely to contribute to observed reductions in risk of MI and ischemic stroke with alcohol consumption, some changes in biologic pathways (e.g., decreased clotting) also help explain how alcohol consumption may increase risk of hemorrhagic stroke.

PRIOR DGA RECOMMENDATIONS

As explained in Chapter 1 of this report, the Dietary Guidelines Advisory Committee (DGAC) reports and Dietary Guidelines for Americans (DGA) have sometimes addressed the association of alcohol with the risk of CVD. The past three 5-year cycles are summarized below.

In brief, the 2010–2015 DGA and 2015–2020 DGA (USDA and HHS, 2010, 2015) and the 2010 and 2015 Dietary Guidelines Advisory Committee (USDA and HHS, 2010, 2015) reports concluded that moderate alcohol consumption (defined as up to one drink per day for women and up to two drinks per day for men) is associated with lower risk of CVD, when compared to nondrinkers. The 2020 DGAC report provided a narrative synthesis of four Mendelian randomization studies and concluded that those studies did not support a lower risk of CVD at lower levels of alcohol consumption, which the report found was inconsistent with the extensive body of evidence from observational studies. It is important to note that the Mendelian randomization design has its own set of limitations (see Chapter 2).

2010

The 2010–2015 DGA (USDA and HHS, 2010) does not include much information about the specific association of alcohol consumption with CVD morbidity and/or mortality. In a general statement about the dietary factors associated with increased risk of chronic disease, the report names excess alcohol consumption as a dietary factor that increases blood pressure. The report notes: “Alcohol consumption may have beneficial effects when consumed in moderation. Strong evidence from observational studies has shown that moderate alcohol consumption is associated with a lower risk of cardiovascular disease.”1 The above statements were not linked to scientific references, and a systematic review of evidence was not conducted.

The 2010 committee addressed the question, “What is the relationship between alcohol intake and coronary heart disease?” The committee used meta-analyses and systematic reviews (SRs) published in the period since the 2005 DGAC report to answer the question. The focus was on moderate drinking, which the 2010 DGAC report defined as no more than 14 drinks a week for men and 7 drinks a week for women with no more than 4 drinks on any given day for men and no more than 3 drinks on any given day for women.2 The 2010 DGAC report (DGAC, 2010) concluded there was no meaningful change in the research findings on alcohol and CVD risk since

___________________

1 2010 Dietary Guidelines for Americans Report, p. 31.

2 2010 Dietary Guidelines Advisory Committee Report, p. 354.

the 2005 report and that no new systematic reviews were warranted; the committee reiterated the findings of prior committees. The overall conclusion was: “compared to those who abstain from alcohol, regular light to moderate drinking can reduce the risk of coronary heart disease (CHD) whereas heavy irregular or binge drinking increases risk of CHD.”3

For the risk of stroke, the report found that light to moderate alcohol consumption may be protective against total and ischemic stroke, noting that 10 prospective studies since the last report supported that finding. Furthermore, the report concluded that there is strong evidence that moderate alcohol consumption does not elevate the risk of either hypertension or stroke compared to nondrinking. The report noted that heavier alcohol intake is clearly associated with adverse cardiovascular outcomes, and evidence supports that reducing alcohol intake is an effective treatment for lowering blood pressure in persons with elevated blood pressure (DGAC, 2010).

2015

The 2015–2020 DGA include an appendix on alcohol, but it has limited information about the association of alcohol with chronic disease outcomes, including CVD endpoints (USDA and HHS, 2015). The 2015 DGAC report (DGAC, 2015) focused on dietary patterns and reached an overall conclusion that “moderate consumption of alcohol also [is] shown to be [a] component of a beneficial dietary pattern in most studies.”4 The emphasis in the 2015 report was on the need to include the energy (calories) from alcohol consumption in defining healthy eating patterns to avoid excess energy consumption and the risk of weight gain. The report concluded that there was strong evidence to indicate that some dietary patterns, for example the Mediterranean Diet, include moderate intake of alcohol and these patterns are associated with reduced risk of CVD.5

2020

The DGA did not specifically address the role of alcohol in cardiovascular morbidity and/or mortality (USDA and HHS, 2020). The 2020 DGAC report (DGAC, 2020) devoted a chapter to alcohol and health and conducted a systematic review designed to address the question: “What is the relationship between alcohol consumption and all-cause mortality?” The 2020 DGAC report also included a narrative synthesis of Mendelian randomization studies of alcohol and CVD because time constraints and the prioritization of all-cause mortality precluded a full systematic review for

___________________

3 2010 Dietary Guidelines Advisory Committee Report, p. 359.

4 2015 Dietary Guidelines Advisory Committee Report, p. 188.

5 2015 Dietary Guidelines Advisory Committee Report, p. 211.

the CVD outcome. The 2020 committee searched the literature from 2010 to 2020. The report concluded that the Mendelian randomization analysis “revealed no evidence of reduced associations for myocardial infarction or total coronary heart disease at low levels of alcohol consumption, with little overall effect of alcohol consumption on those outcomes.”6

METHODOLOGICAL LIMITATIONS

Some of the methodological challenges associated with the use of MACE-3 as an outcome include incomplete ascertainment of CVD events, in particular silent MI; misclassification of MI or stroke depending on the rigor of diagnostic criteria; and missing averted MI or stroke in the settings of early intervention, such as percutaneous coronary intervention or early thrombolytic therapy upon onset of MI and/or stroke signs and symptoms.

SYSTEMATIC REVIEW

Approach

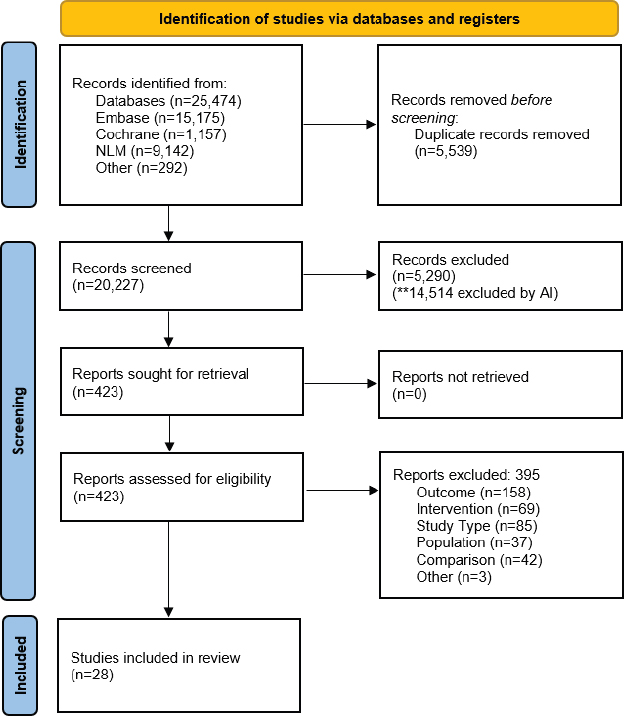

An evidence scan of the recent literature was conducted and searched for prior systematic reviews and original research studies published from 2020 to 2024; the screening of the search results is shown in Figure 6-1. The evidence scan identified 19 systematic reviews of which five were published in 2020, four in 2021, seven in 2022, two in 2023, and one in 2024; about half of the reviews conducted a meta-analysis. The published reviews were approximately equally distributed across AMSTAR-27 quality categories, thus five were high quality and nine were assessed as critically low or low quality. Eight of the 19 reviews considered CVD outcomes broadly, and the remaining 11 focused on specific CVD outcomes, including blood pressure, hypertension, heart failure, atrial fibrillation, flow mediated dilation, lipids, and metabolic markers.

The evidence scan for original research studies was conducted for the period 2010 to 2024, given that past DGACs did not review this literature. There were 109 studies of alcohol and CVD identified, including 21 published between 2010 to 2015, 45 between 2016 to 2020, and 42 between 2021 and 2024. Forty-two of these studies were noninformative due to various methodological reasons (e.g., the exposure indicator was insufficient for comparison; the comparator included subjects who consumed alcohol in the past/former drinkers; wrong study outcome). The mixed quality and the diversity of outcomes considered in past systematic reviews meant that these reviews were not adequate to support the work of this committee.

___________________

6 2020 Dietary Guidelines Advisory Committee Report, p. 19, 20.

7 A Measurement Tool to Assess Systematic Reviews; see Chapter 2.

NOTES: The diagram shows the number of primary articles identified from the primary article and systematic review searches and each step of screening. The literature dates include articles with the publications between 2010 and 2024. n = number; NLM = National Library of Medicine; PRISMA = Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses.

SOURCE: Figure H-1 in Appendix H, Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics, 2024.

Given the number of original studies identified in the evidence scan, the committee made the decision to conduct a de novo systematic review of the relationship between alcohol consumption and the risk of CVD; the commissioned systematic review searched for published literature from January 2010 to February 2024 (AND, 2024). The risk of bias and the certainty of the evidence of the studies included in the systematic reviews are summarized in Table 6-1 and Table 6-2, respectively.

| Study | Source of Bias | Overall Risk of Bias |

|---|---|---|

| Bell et al., 2017 | Confounding, exposure assessment | Some concerns |

| Chang et al., 2020 | Confounding | Some concerns |

| Chiuve et al., 2010 | Confounding, exposure assessment | Some concerns |

| Di Castelnuovo et al., 2022 | Confounding, exposure assessment | Some concerns |

| Duan et al., 2019 | No bias identified | Low |

| Hernandez-Hernandez et al., 2015 (SUN Study) | Confounding, exposure assessment | Some concerns |

| Ilomäki et al., 2012 | Confounding | Some concerns |

| Im et al., 2023 | Confounding, exposure assessment | Some concerns |

| Jankhotkaew et al., 2020 | Confounding, exposure assessment | Some concerns |

| Jeong et al., 2022 | Confounding | Some concerns |

| Johansson et al., 2021 | Exposure assessment | Some concerns |

| John et al., 2021 | Confounding, exposure assessment | High |

| Jones et al., 2015 | Exposure assessment | Some concerns |

| Kadlecová et al., 2015 | Exposure assessment | Some concerns |

| Larsson et al., 2017 | Exposure assessment | Some concerns |

| Liu et al., 2022 | Exposure assessment | Some concerns |

| Liu et al., 2023 | Exposure assessment, selection bias | Some concerns |

| Lv et al., 2017 | Exposure assessment | Some concerns |

| Ma et al., 2021 | Exposure assessment | Some concerns |

| Merry et al., 2011 | Confounding, exposure assessment | Some concerns |

| Millwood et al., 2019 | Confounding | Some concerns |

| Muraki et al., 2023 | Confounding, exposure assessment | Some concerns |

| Ricci et al., 2020 | Confounding | High |

| Smyth et al., 2015 | Exposure assessment | Some concerns |

| Stamatakis et al., 2021 | Exposure assessment | Some concerns |

| Tian et al., 2023 | Confounding | Some concerns |

| Ye et al., 2021 | Confounding, exposure assessment | Some concerns |

| Zhang et al., 2021 | No bias identified | Low |

NOTE: Overall risk of bias is based on seven domains: (1) confounding; (2) measurement of the exposure; (3) selection of participants into the study (or into the analysis); (4) post-exposure interventions; (5) missing data; (6) measurement of the outcome; and (7) selection of the reported results.

SOURCE: Adapted from Figure H-2 in Appendix H, Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics, 2024.

| Certainty Assessment | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Participants (Studies) Follow-up | Risk of Bias | Inconsistency | Indirectness | Imprecision | Publication Bias | Overall Certainty of evidence |

| CVD Mortality for Moderate Consumption vs. Never Consuming | ||||||

| 329,772 (4 nonrandomized studies)h | seriousa | not serious | not serious | not serious | none | moderate |

| CVD Mortality Consuming Higher vs. Lower Moderate Alcohol Consumption | ||||||

| 14,920 (1 nonrandomized study)i | very seriousd | not serious | not serious | seriousc | none | veryf low |

| MI for Moderate Alcohol Consumption vs. Never Consuming | ||||||

| 139,317 (2 nonrandomized studies)j | seriousa | not serious | not serious | not serious | none | moderate |

| MI Consuming Higher vs. Lower Alcohol Amounts Within Moderate Alcohol Consumption | ||||||

| 38,751 (2 nonrandomized studies)k | seriousa | seriousb | not serious | seriouse | none | veryf low |

| Stroke for Moderate Alcohol Consumption vs. Never Consuming | ||||||

| 3,129,600 (7 nonrandomized studies)l | seriousa | not serious | not serious | not serious | none | lowg |

| Stroke Consuming Higher vs. Lower Alcohol Amounts Within Moderate Alcohol Consumption | ||||||

| 7,277 (1 nonrandomized study)m | seriousa | not serious | not serious | seriousc | none | low |

a Some concerns of bias in most included studies.

b High heterogeneity in results between studies.

c Wide confidence interval include potential benefit and harms.

d One study with high risk of bias.

e Meta-analysis was not possible, as Ilomäki et al. (2012) compared lower to higher consumption, and Larsson et al. (2017) compared higher to lower consumption.

f The committee used the phrase “insufficient evidence” to reflect a lower level of certainty of the evidence, as indicated by the assignment of “very low” in the commissioned systematic reviews by the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics.

g Jeong et al. (2022) met inclusion criteria by the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics. Because it was unclear how never drinkers were classified, the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics’ categorization was retained, but the committee downgraded the certainty from “moderate” to “low” certainty.

h Chiuve et al., 2010; Di Castelnuovo et al., 2022; Muraki et al., 2023; Tian et al., 2023.

j Chiuve et al., 2010; Smyth et al., 2015.

k Larsson et al., 2017; Zhang et al., 2021.

l Chang et al., 2020; Duan et al., 2019; Jeong et al., 2022 Jones et al., 2015; Liu et al., 2023; Lv et al., 2017; Smyth et al., 2015.

SOURCE: Adapted from Table H-4 in Appendix H, Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics, 2024.

Results

Myocardial Infarction

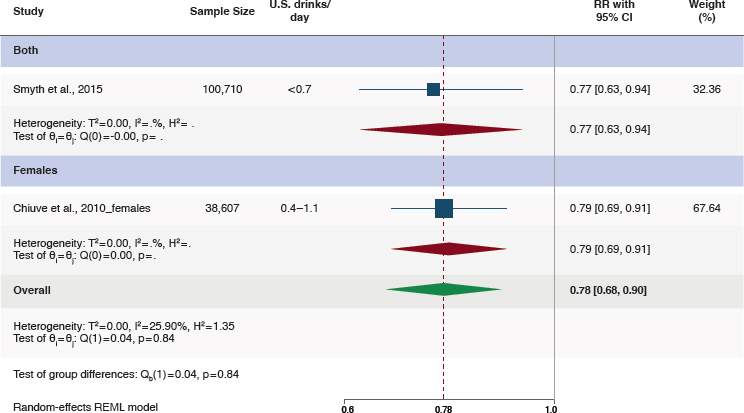

While 26 cohort studies that examined the associations between alcohol consumption and cardiovascular outcomes of interest were included in the systematic review, only eight studies reported findings for the outcome of myocardial infarction (MI). Of these eight studies, only two studies had comparisons that could be included in summarizing the association of moderate alcohol consumption, compared to never consuming alcohol, and the risk of MI. The committee based its conclusions on two studies available for MI deemed to have sufficient power but downgraded the level of certainty to low. The findings are summarized in Table 6-3 and Figure 6-2.

Finding 6-1: A meta-analysis of two eligible studies found that among persons who consumed moderate amounts of alcohol compared with persons who never consumed alcohol, there was a 22 percent lower risk of MI (RR = 0.88, 95%CI [0.68, 0.90]). No studies reported data for males alone. One study reported a 21 percent lower risk of MI among females only; these results were consistent with the estimate for both sexes combined. There were some concerns related to risk of bias in the studies, mainly due to confounding.

| Category | N Studies | RR (95% CI) | I2 (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Main Analysisa | |||

| Moderate Alcohol Consumption | 2 | 0.78 [0.68, 0.90] | 25.9 |

| Subgroup Analysesa | |||

| Moderate Alcohol Consumption | |||

| Males | – | – | |

| Females | 1 | 0.79 [0.69, 0.91] | N/A |

| Both | 1 | 0.77 [0.63, 0.94] | N/A |

NOTES: A dash indicates that there were no studies available for this comparison. CI = confidence interval; I2 = heterogeneity; MI = myocardial infarction; N = number; N/A = not applicable; RR = relative risk.

a Meta-analyses of drinking categories were conducted using separate meta-analyses to avoid over-counting participants in comparison groups.

SOURCE: Adapted from Table H-3 in Appendix H, Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics, 2024.

NOTES: CI = confidence interval; REML = restricted maximum likelihood; RR = relative risk.

SOURCE: Figure H-3 in Appendix H, American Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics, 2024.

Conclusion 6-1: The committee concludes that compared with never consuming alcohol, consuming moderate amounts of alcohol is associated with a lower risk of nonfatal MI (low certainty).

Stroke

Of the 26 cohort studies included in the review, 13 cohort studies examined the association of alcohol consumption on the risk of stroke; seven of these studies compared alcohol consumption to never consuming alcohol. Results from included studies were extracted for total stroke when available and ischemic stroke when total stroke was not reported, given ischemic stroke comprises most stroke cases (Table 6-4 and Figure 6-3).

Finding 6-2: A meta-analysis of seven eligible studies found an 11 percent lower risk of stroke among persons consuming moderate amounts of alcohol compared with persons never consuming alcohol (RR = 0.89, 95%CI [0.86, 0.93]). These results were driven by ischemic stroke, which showed a 12 percent lower risk (RR = 0.88, 95%CI [0.86, 0.90]).

| Category | N Studies | RR (95% CI) | I2 (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Main Analysisa | |||

| Moderate Alcohol Consumptionb | 7 | 0.89 [0.86, 0.93]c | 7.3 |

| Subgroup Analyses a | |||

| Moderate Alcohol Consumption | |||

| Males | 3 | 1.02 [0.70, 1.49] | 77.0 |

| Females | 2 | 0.86 [0.51, 1.44] | 8.9 |

| Both | 4 | 0.88 [0.86, 0.90] | 0.01 |

NOTES: CI = confidence interval; N = number; I2 = heterogeneity; RR = relative risk.

a Meta-analyses of drinking categories were conducted using separate meta-analyses to avoid over-counting participants in comparison groups.

b Moderate consumption levels are ≤1 drink/day for women and ≤2 drinks/day for men. 1 U.S. drink = 14 grams of alcohol.

c Results in bold are statistically significant (p < 0.05).

SOURCE: Adapted from Table H-6 in Appendix H, Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics, 2024.

Separate examination of hemorrhagic strokes was infrequent; thus, no estimate of effect for this health outcome could be made. There were some concerns related to risk of bias among the studies, mainly due to confounding and exposure assessment.

Conclusion 6-2: The committee concludes that compared with never consuming alcohol, consuming moderate amounts of alcohol is associated with a lower risk of nonfatal stroke (low certainty).

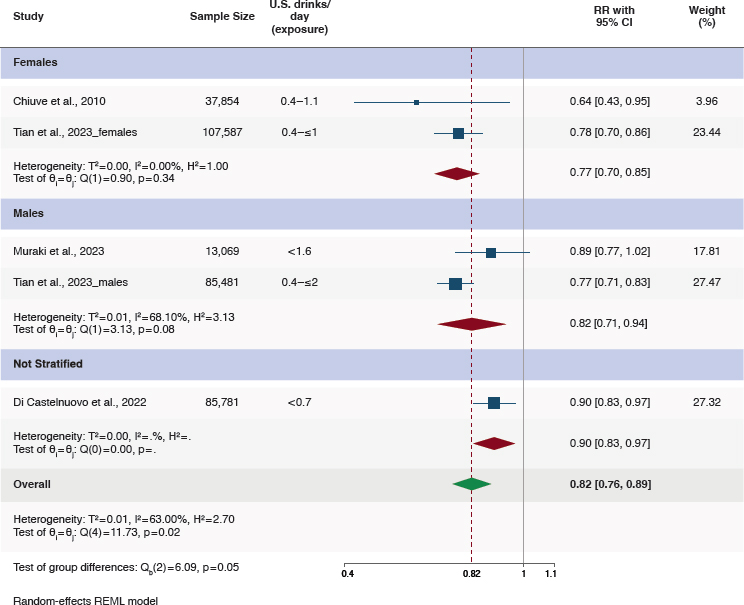

CVD Mortality

While 13 studies investigated the association of alcohol consumption with CVD mortality, only seven of those used never drinkers as the comparison group; among those seven studies, only four were informative for estimating the association of moderate alcohol consumption compared to never consuming alcohol on the risk of CVD mortality. These four studies were meta-analyzed as shown in Table 6-5 and Figure 6-4.

Finding 6-3: A meta-analysis of four eligible studies found an 18 percent lower risk of CVD mortality among persons who consumed moderate amounts of alcohol compared with those who never consumed alcohol

NOTES: CI = confidence interval; REML = restricted maximum likelihood; RR = relative risk.

SOURCE: Figure H-6 in Appendix H, American Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics, 2024.

(RR = 0.82, 95%CI [0.76, 0.89]). The committee further found a 23 percent lower risk in females (RR = 0.77, 95%CI [0.70, 0.85]), and an 18 percent lower risk in males (RR = 0.82, 95%CI [0.71, 0.94]). Very limited data stratified by age were available; however, one study showed that the effect size and direction for moderate alcohol consumption compared with no alcohol consumption was consistent among persons aged less than 60 years (33 percent lower risk of CVD mortality) and among persons aged 60 years or older (19 percent lower risk of CVD mortality). There were some concerns related to risk of bias, mainly due to confounding, in the studies contributing to this comparison.

| Category | N Studies | RR (95% CI) | I2 (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Main Analysisa | |||

| Moderate Alcohol Consumptionb | 4 | 0.82 [0.76, 0.89]c | 63.0 |

| Subgroup Analyses a | |||

| Moderate Alcohol Consumption | |||

| Males | 2 | 0.82 [0.71, 0.94] | 68.1 |

| Females | 2 | 0.77 [0.70, 0.85] | 0 |

| Not stratified | 1 | 0.90 [0.83, 0.97] | N/A |

| Moderate Alcohol Consumption | |||

| <60 years | 1 | 0.67 [0.59, 0.76] | N/A |

| ≥60 years | 1 | 0.81 [0.75, 0.87] | N/A |

| Not stratified | 3 | 0.89 [0.83, 0.95] | 0.03 |

NOTES: CI = confidence interval; I2 = heterogeneity; N = number; N/A = Not Applicable; RR = relative risk.

a Meta-analyses of drinking categories were conducted using separate meta-analyses to avoid over-counting participants in comparison groups.

b Moderate amounts are ≤1 drink/day for women and ≤2 drinks/day for men. 1 U.S. drink = 14 grams of alcohol.

c Results in bold are statistically significant (p < 0.05).

SOURCE: Adapted from Table H-8 in Appendix H, Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics, 2024.

Conclusion 6-3: The committee concludes that compared with never consuming alcohol, consuming moderate amounts of alcohol is associated with a lower risk of CVD mortality in both females and males (moderate certainty).

Summary of Evidence Relative to Past DGA Guidance

Based on the results of the de novo SR using data from 2010 to 2024, the committee concludes these results are consistent with prior DGAC reports that moderate alcohol consumption, compared to never drinking, is associated with a lower risk of MI, total stroke, and CVD mortality with evidence grades of low certainty, low certainty, and moderate certainty for findings summarized in Conclusions 6-1, 6-2, and 6-3, respectively.

NOTES: CI = confidence interval; REML = restricted maximum likelihood; RR = relative risk.

SOURCE: Figure H-9 in Appendix H, Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics, 2024.

REFERENCES

AND (Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics). 2024. Alcohol Consumption and Cardiovascular Outcomes: Systematic Review. Appendix H available at https://nap.nationalacademies.org/catalog/28582 (accessed January 30, 2025).

Bell, S., M. Daskalopoulou, E. Rapsomaniki, J. George, A. Britton, M. Bobak, J. P. Casas, C. E. Dale, S. Denaxas, A. D. Shah, and H. Hemingway. 2017. Association between clinically recorded alcohol consumption and initial presentation of 12 cardiovascular diseases: Population based cohort study using linked health records. BMJ 356:j909.

Brien, S. E., P. E. Ronksley, B. J. Turner, K. J. Mukamal, and W. A. Ghali. 2011. Effect of alcohol consumption on biological markers associated with risk of coronary heart disease: Systematic review and meta-analysis of interventional studies. BMJ 342:d636.

Camargo, C. A., Jr., P. T. Williams, K. M. Vranizan, J. J. Albers, and P. D. Wood. 1985. The effect of moderate alcohol intake on serum apolipoproteins A-I and A-II. A controlled study. JAMA 253(19):2854–2857.

Chang, J. Y., S. Choi, and S. M. Park. 2020. Association of change in alcohol consumption with cardiovascular disease and mortality among initial nondrinkers. Science Reports 10(1):13419.

Chiuve, S. E., E. B. Rimm, K. J. Mukamal, K. M. Rexrode, M. J. Stampfer, J. E. Manson, and C. M. Albert. 2010. Light-to-moderate alcohol consumption and risk of sudden cardiac death in women. Heart Rhythm 7(10):1374–1380.

Chiva-Blanch, G., E. Magraner, X. Condines, P. Valderas-Martinez, I. Roth, S. Arranz, R. Casas, M. Navarro, A. Hervas, A. Siso, M. Martinez-Huelamo, A. Vallverdu-Queralt, P. Quifer-Rada, R. M. Lamuela-Raventos, and R. Estruch. 2015. Effects of alcohol and polyphenols from beer on atherosclerotic biomarkers in high cardiovascular risk men: A randomized feeding trial. Nutrition, Metabolism, and Cardiovascular Diseases 25(1):36–45.

DGAC (Dietary Guidelines Advisory Committee). 2010. Report of the Dietary Guidelines Advisory Committee on the Dietary Guidelines for Americans, 2010, to the Secretary of Agriculture and the Secretary of Health and Human Services. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Agricultural Research Service, Washington, DC.

DGAC. 2015. Scientific Report of the 2015 Dietary Guidelines Advisory Committee: Advisory Report to the Secretary of Health and Human Services and the Secretary of Agriculture. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Agricultural Research Service, Washington, DC.

DGAC. 2020. Scientific Report of the 2020 Dietary Guidelines Advisory Committee: Advisory Report to the Secretary of Agriculture and the Secretary of Health and Human Services. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Agricultural Research Service, Washington, DC.

Di Castelnuovo, A., S. Costanzo, M. Bonaccio, P. McElduff, A. Linneberg, V. Salomaa, S. Mannisto, M. Moitry, J. Ferrieres, J. Dallongeville, B. Thorand, H. Brenner, M. Ferrario, G. Veronesi, E. Pettenuzzo, A. Tamosiunas, I. Njolstad, W. Drygas, Y. Nikitin, S. Soderberg, F. Kee, G. Grassi, D. Westermann, B. Schrage, S. Dabboura, T. Zeller, K. Kuulasmaa, S. Blankenberg, M. B. Donati, G. de Gaetano, and L. Iacoviello. 2022. Alcohol intake and total mortality in 142,960 individuals from the MORGAM project: A population-based study. Addiction 117(2):312–325.

Ding, C., D. O’Neill, S. Bell, E. Stamatakis, and A. Britton. 2021. Association of alcohol consumption with morbidity and mortality in patients with cardiovascular disease: Original data and meta-analysis of 48,423 men and women. BMC Medicine 19(1):167.

Duan, Y., A. Wang, Y. Wang, X. Wang, S. Chen, Q. Zhao, X. Li, S. Wu, and L. Yang. 2019. Cumulative alcohol consumption and stroke risk in men. Journal of Neurology 266(9):2112–2119.

Dunbar, S. B., O. A. Khavjou, T. Bakas, G. Hunt, R. A. Kirch, A. R. Leib, R. S. Morrison, D. C. Poehler, V. L. Roger, L. P. Whitsel, and A. American Heart. 2018. Projected costs of informal caregiving for cardiovascular disease: 2015 to 2035: A policy statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation 137(19):e558–e577.

Fragopoulou, E., C. Argyrou, M. Detopoulou, S. Tsitsou, S. Seremeti, M. Yannakoulia, S. Antonopoulou, G. Kolovou, and P. Kalogeropoulos. 2021. The effect of moderate wine consumption on cytokine secretion by peripheral blood mononuclear cells: A randomized clinical study in coronary heart disease patients. Cytokine 146:155629.

GBD 2021 Causes of Death Collaborators. 2024. Global burden of 288 causes of death and life expectancy decomposition in 204 countries and territories and 811 subnational locations, 1990–2021: A systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2021. Lancet 403(10440):2100–2132.

Gepner, Y., R. Golan, I. Harman-Boehm, Y. Henkin, D. Schwarzfuchs, I. Shelef, R. Durst, J. Kovsan, A. Bolotin, E. Leitersdorf, S. Shpitzen, S. Balag, E. Shemesh, S. Witkow, O. Tangi-Rosental, Y. Chassidim, I. F. Liberty, B. Sarusi, S. Ben-Avraham, A. Helander, U. Ceglarek, M. Stumvoll, M. Bluher, J. Thiery, A. Rudich, M. J. Stampfer, and I. Shai. 2015. Effects of

initiating moderate alcohol intake on cardiometabolic risk in adults with type 2 diabetes: A 2-year randomized, controlled trial. Annals of Internal Medicine 163(8):569–579.

Hernandez-Hernandez, A., A. Gea, M. Ruiz-Canela, E. Toledo, J. J. Beunza, M. Bes-Rastrollo, and M. A. Martínez-González. 2015. Mediterranean alcohol-drinking pattern and the incidence of cardiovascular disease and cardiovascular mortality: The SUN project. Nutrients 7(11):9116–9126.

Huang, Y., Y. Li, S. Zheng, X. Yang, T. Wang, and J. Zeng. 2017. Moderate alcohol consumption and atherosclerosis: Meta-analysis of effects on lipids and inflammation. Wiener Klinische Wochenschrift 129(21-22):835–843.

Ilomäki, J., A. Hajat, J. Kauhanen, S. Kurl, J. S. Kaufman, T. P. Tuomainen, and M. J. Korhonen. 2012. Relationship between alcohol consumption and myocardial infarction among ageing men using a marginal structural model. European Journal of Public Health 22(6): 825–830.

Im, P. K., N. Wright, L. Yang, K. H. Chan, Y. Chen, Y. Guo, H. Du, X. Yang, D. Avery, S. Wang, C. Yu, J. Lv, R. Clarke, J. Chen, R. Collins, R. G. Walters, R. Peto, L. Li, Z. Chen, I. Y. Millwood, and G. China Kadoorie Biobank Collaborative. 2023. Alcohol consumption and risks of more than 200 diseases in Chinese men. Nature Medicine 29(6): 1476–1486.

Jankhotkaew, J., K. Bundhamcharoen, R. Suphanchaimat, O. Waleewong, S. Chaiyasong, K. Markchang, C. Wongworachate, P. Vathesatogkit, and P. Sritara. 2020. Associations between alcohol consumption trajectory and deaths due to cancer, cardiovascular diseases and all-cause mortality: A 30-year follow-up cohort study in Thailand. BMJ Open 10(12):e038198.

Jeong, S. M., H. R. Lee, K. Han, K. H. Jeon, D. Kim, J. E. Yoo, M. H. Cho, S. Chun, S. P. Lee, K. W. Nam, and D. W. Shin. 2022. Association of change in alcohol consumption with risk of ischemic stroke. Stroke 53(8):2488–2496.

Johansson, A., I. Drake, G. Engstrom, and S. Acosta. 2021. Modifiable and non-modifiable risk factors for atherothrombotic ischemic stroke among subjects in the MALMO diet and cancer study. Nutrients 13(6).

John, U., H. J. Rumpf, M. Hanke, and C. Meyer. 2021. Alcohol abstinence and mortality in a general population sample of adults in Germany: A cohort study. PLoS Medicine 18(11): e1003819.

Jones, S. B., L. Loehr, C. L. Avery, R. F. Gottesman, L. Wruck, E. Shahar, and W. D. Rosamond. 2015. Midlife alcohol consumption and the risk of stroke in the atherosclerosis risk in communities study. Stroke 46(11):3124–3130.

Kadlecová, P., R. Andel, R. Mikulik, E. P. Handing, and N. L. Pedersen. 2015. Alcohol consumption at midlife and risk of stroke during 43 years of follow-up: Cohort and twin analyses. Stroke 46(3):627–633.

Larsson, S. C., A. Wallin, and A. Wolk. 2017. Contrasting association between alcohol consumption and risk of myocardial infarction and heart failure: Two prospective cohorts. International Journal of Cardiology 231:207–210.

Liu, X., X. Ding, F. Zhang, L. Chen, Q. Luo, M. Xiao, X. Liu, Y. Wu, W. Tang, J. Qiu, and X. Tang. 2023. Association between alcohol consumption and risk of stroke among adults: Results from a prospective cohort study in Chongqing, China. BMC Public Health 23(1):1593.

Liu, Y. T., J. H. Lee, M. K. Tsai, J. C. Wei, and C. P. Wen. 2022. The effects of modest drinking on life expectancy and mortality risks: A population-based cohort study. Scientific Reports 12(1):7476.

Luceron-Lucas-Torres, M., A. Saz-Lara, A. Diez-Fernandez, I. Martinez-Garcia, V. Martinez-Vizcaino, I. Cavero-Redondo, and C. Alvarez-Bueno. 2023. Association between wine consumption with cardiovascular disease and cardiovascular mortality: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Nutrients 15(12).

Luengo-Fernandez, R., M. Walli-Attaei, A. Gray, A. Torbica, A. P. Maggioni, R. Huculeci, F. Bairami, V. Aboyans, A. D. Timmis, P. Vardas, and J. Leal. 2023. Economic burden of cardiovascular diseases in the European union: A population-based cost study. European Heart Journal 44(45):4752–4767.

Lv, J., C. Yu, Y. Guo, Z. Bian, L. Yang, Y. Chen, X. Tang, W. Zhang, Y. Qian, Y. Huang, X. Wang, J. Chen, Z. Chen, L. Qi, L. Li, and G. China Kadoorie Biobank Collaborative. 2017. Adherence to healthy lifestyle and cardiovascular diseases in the Chinese population. Journal of the American College of Cardiology 69(9):1116–1125.

Ma, H., X. Li, T. Zhou, D. Sun, I. Shai, Y. Heianza, E. B. Rimm, J. E. Manson, and L. Qi. 2021. Alcohol consumption levels as compared with drinking habits in predicting all-cause mortality and cause-specific mortality in current drinkers. Mayo Clinic Proceedings 96(7):1758–1769.

Martin, S. S., A. W. Aday, Z. I. Almarzooq, C. A. M. Anderson, P. Arora, C. L. Avery, C. M. Baker-Smith, B. Barone Gibbs, A. Z. Beaton, A. K. Boehme, Y. Commodore-Mensah, M. E. Currie, M. S. V. Elkind, K. R. Evenson, G. Generoso, D. G. Heard, S. Hiremath, M. C. Johansen, R. Kalani, D. S. Kazi, D. Ko, J. Liu, J. W. Magnani, E. D. Michos, M. E. Mussolino, S. D. Navaneethan, N. I. Parikh, S. M. Perman, R. Poudel, M. Rezk-Hanna, G. A. Roth, N. S. Shah, M. P. St-Onge, E. L. Thacker, C. W. Tsao, S. M. Urbut, H. G. C. Van Spall, J. H. Voeks, N. Y. Wang, N. D. Wong, S. S. Wong, K. Yaffe, L. P. Palaniappan, American Heart Association Council on Epidemiology and Prevention Statistics Committee and Stroke Statistics Subcommittee. 2024. 2024 heart disease and stroke statistics: A report of US and global data from the American Heart Association. Circulation 149(8):e347–e913.

Masarei, J. R., I. B. Puddey, I. L. Rouse, W. J. Lynch, R. Vandongen, and L. J. Beilin. 1986. Effects of alcohol consumption on serum lipoprotein-lipid and apolipoprotein concentrations. Results from an intervention study in healthy subjects. Atherosclerosis 60(1): 79–87.

Merry, A. H., J. M. Boer, L. J. Schouten, E. J. Feskens, W. M. Verschuren, A. P. Gorgels, and P. A. van den Brandt. 2011. Smoking, alcohol consumption, physical activity, and family history and the risks of acute myocardial infarction and unstable angina pectoris: A prospective cohort study. BMC Cardiovascular Disorders 11:13.

Millwood, I. Y., R. G. Walters, X. W. Mei, Y. Guo, L. Yang, Z. Bian, D. A. Bennett, Y. Chen, C. Dong, R. Hu, G. Zhou, B. Yu, W. Jia, S. Parish, R. Clarke, G. Davey Smith, R. Collins, M. V. Holmes, L. Li, R. Peto, Z. Chen, and G. China Kadoorie Biobank Collaborative. 2019. Conventional and genetic evidence on alcohol and vascular disease aetiology: A prospective study of 500,000 men and women in China. Lancet 393(10183):1831–1842.

Muraki, I., H. Iso, H. Imano, R. Cui, S. Ikehara, K. Yamagishi, and A. Tamakoshi. 2023. Alcohol consumption and long-term mortality in men with or without a history of myocardial infarction. Atherosclerosis and Thrombosis 30(4):415–428.

Ricci, C., A. E. Schutte, R. Schutte, C. M. Smuts, and M. Pieters. 2020. Trends in alcohol consumption in relation to cause-specific and all-cause mortality in the United States: A report from the nhanes linked to the us mortality registry. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition 111(3):580589.

Ridker, P. M., N. R. Cook, I. M. Lee, D. Gordon, J. M. Gaziano, J. E. Manson, C. H. Hennekens, and J. E. Buring. 2005. A randomized trial of low-dose aspirin in the primary prevention of cardiovascular disease in women. New England Journal of Medicine 352(13):1293–1304.

Schrieks, I. C., A. L. Heil, H. F. Hendriks, K. J. Mukamal, and J. W. Beulens. 2015. The effect of alcohol consumption on insulin sensitivity and glycemic status: A systematic review and meta-analysis of intervention studies. Diabetes Care 38(4):723–732.

Sierksma, A., M. S. van der Gaag, C. Kluft, and H. F. Hendriks. 2002. Moderate alcohol consumption reduces plasma c-reactive protein and fibrinogen levels; a randomized, diet-controlled intervention study. European Journal of Clinical Nutrition 56(11):1130–1136.

Smyth, A., K. K. Teo, S. Rangarajan, M. O’Donnell, X. Zhang, P. Rana, D. P. Leong, G. Dagenais, P. Seron, A. Rosengren, A. E. Schutte, P. Lopez-Jaramillo, A. Oguz, J. Chifamba, R. Diaz, S. Lear, A. Avezum, R. Kumar, V. Mohan, A. Szuba, L. Wei, W. Yang, B. Jian, M. McKee, S. Yusuf, and P. Investigators. 2015. Alcohol consumption and cardiovascular disease, cancer, injury, admission to hospital, and mortality: A prospective cohort study. Lancet 386(10007):1945–1954.

Song, R. J., X. T. Nguyen, R. Quaden, Y. L. Ho, A. C. Justice, D. R. Gagnon, K. Cho, C. J. O’Donnell, J. Concato, J. M. Gaziano, L. Djousse, and V. A. M. V. Program. 2018. Alcohol consumption and risk of coronary artery disease (from the Million Veteran Program). American Journal of Cardiology 121(10):1162–1168.

Spaggiari, G., A. Cignarelli, A. Sansone, M. Baldi, and D. Santi. 2020. To beer or not to beer: A meta-analysis of the effects of beer consumption on cardiovascular health. PLoS One 15(6):e0233619.

Stamatakis, E., K. B. Owen, L. Shepherd, B. Drayton, M. Hamer, and A. E. Bauman. 2021. Is cohort representativeness passe? Poststratified associations of lifestyle risk factors with mortality in the UK Biobank. Epidemiology 32(2):179–188.

Stote, K. S., R. P. Tracy, P. R. Taylor, and D. J. Baer. 2016. The effect of moderate alcohol consumption on biomarkers of inflammation and hemostatic factors in postmenopausal women. European Journal of Clinical Nutrition 70(4):470–474.

Tian, Y., J. Liu, Y. Zhao, N. Jiang, X. Liu, G. Zhao, and X. Wang. 2023. Alcohol consumption and all-cause and cause-specific mortality among us adults: Prospective cohort study. BMC Medicine 21(1):208.

Umar, A., F. Depont, A. Jacquet, S. Lignot, M. C. Segur, M. Boisseau, B. Begaud, and N. Moore. 2005. Effects of armagnac or vodka on platelet aggregation in healthy volunteers: A randomized controlled clinical trial. Thrombosis Research 115(1-2):31–37.

USDA (U.S. Department of Agriculture) and HHS (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services). 2010. Dietary Guidelines for Americans, 2010. Washington, DC. https://www.dietaryguidelines.gov/sites/default/files/2019-05/DietaryGuidelines2010.pdf (accessed September 20, 2024).

USDA and HHS. 2015. 2015–2020 Dietary Guidelines for Americans. Washington, DC. https://health.gov/sites/default/files/2019-09/2015–2020_Dietary_Guidelines.pdf (accessed September 20, 2024).

USDA and HHS. 2020. Dietary Guidelines for Americans, 2020–2025. Washington, DC. https://www.dietaryguidelines.gov/sites/default/files/2021-03/Dietary_Guidelines_for_Americans_2020-2025.pdf (accessed September 20, 2024).

Ye, X. F., C. Y. Miao, W. Zhang, C. S. Sheng, Q. F. Huang, and J. G. Wang. 2021. Alcohol consumption in relation to cardiovascular and non-cardiovascular mortality in an elderly male Chinese population. BMC Public Health 21(1):2053.

Zhang, Q. H., K. Das, S. Siddiqui, and A. K. Myers. 2000. Effects of acute, moderate ethanol consumption on human platelet aggregation in platelet-rich plasma and whole blood. Alcoholism, Clinical and Experimental Research 24(4):528–534.

Zhang, X., Y. Liu, S. Li, A. H. Lichtenstein, S. Chen, M. Na, S. Veldheer, A. Xing, Y. Wang, S. Wu, and X. Gao. 2021. Alcohol consumption and risk of cardiovascular disease, cancer and mortality: A prospective cohort study. Nutrition Journal 20(1):13.

Zhang, Y., M. T. Pena, L. M. Fletcher, L. Lal, J. M. Swint, and J. C. Reneker. 2023. Economic evaluation and costs of remote patient monitoring for cardiovascular disease in the United States: A systematic review. International Journal of Technology Assessment in Health Care 39(1):e25.

Zhong, L., W. Chen, T. Wang, Q. Zeng, L. Lai, J. Lai, J. Lin, and S. Tang. 2022. Alcohol and health outcomes: An umbrella review of meta-analyses base on prospective cohort studies. Frontiers in Public Health 10:859947.