Review of Evidence on Alcohol and Health (2025)

Chapter: 3 All-Cause Mortality

3

All-Cause Mortality

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, heart disease, cancer, accidents, and stroke are leading causes of death in the United States (CDC, 2024). Previous research studies have demonstrated that modifiable lifestyle factors, including alcohol consumption, are associated with these causes of death. With respect to alcohol consumption, there is strong evidence that heavy drinking has adverse effects on the risk of these leading causes of death. However, owing to the paucity of large and well-designed studies that address the methodological challenges described in Chapter 2 (e.g., the challenges of using self-reported data to capture complexities of alcohol consumption), the association of moderate alcohol consumption with all-cause mortality is less clear. The committee sought to examine the association of moderate alcohol consumption with the risk of all-cause mortality by reviewing publications available from January 2019 through September 2023 and with the focus on moderate alcohol consumption.

CHOICE OF OUTCOMES

The outcome discussed in this chapter is all-cause mortality (i.e., total mortality), which the committee defined as the total number of deaths from all causes expressed per population at risk and calculated for a specific period of time. This outcome is of high public health relevance, and the association of alcohol intake with all-cause mortality provides an overall integration of the effects of alcohol on multiple organ systems, on intentional and unintentional injuries, and on any yet-to-be identified associations. There is strong evidence for the adverse effects of heavy drinking on the risk of the

leading causes of death, including heart disease, stroke, and cancer. While it is also important to understand the association of moderate alcohol consumption with cause-specific mortality, this chapter focuses on the association of moderate alcohol consumption and the risk of all-cause mortality.

BIOLOGICAL PLAUSIBILITY

Previous mechanistic studies have demonstrated that alcohol consumption influences serum levels of intermediary biological markers that are relevant to the incidence of heart disease and stroke. Specifically, the effects of alcohol consumption on lipids, platelet aggregation, inflammation, and endothelial function are well-documented in the literature (Camargo et al., 1985; Chiva-Blanch et al., 2015; Fragopoulou et al., 2021; Gepner et al., 2015; Masarei et al., 1986; Sierksma et al., 2002; Stote et al., 2016; Umar et al., 2005; Zhang et al., 2000). Furthermore, alcohol metabolites, including acetaldehyde, can play a role in the pathogenesis of certain cancers with downstream implication on the risk of death from cancers (Balbo et al., 2012; Ferraguti et al., 2022; Guidolin et al., 2021; Hoes et al., 2021; Mizumoto et al., 2017; Rumgay et al., 2021). The toxic effects of alcohol on several organs and the ability of alcohol to impair brain function has been well established in the literature for trauma and deaths related to alcohol intoxication (Ferragut et al., 2022; Vore and Deak, 2022). A combination of pathways is hypothesized to mediate the effects of alcohol consumption on multiple organ systems to ultimately affect all-cause mortality, including, for example, alcohol’s effect on altering hemostatic factors to increase the risk of bleeding. The investigation of the association of moderate alcohol consumption with all-cause mortality provides an integrated estimate of the full effect of this level of alcohol consumption. Further consideration of cause-specific morbidity and mortality, including cancers, cardiovascular disease, and neurocognitive outcomes, are reported in Chapters 5, 6, and 7, respectively.

PRIOR DGA RECOMMENDATIONS

To contextualize the current findings on the association of alcohol consumption with all-cause mortality, the committee consulted the Dietary Guidelines for Americans (DGA) and the Dietary Guidelines for Americans Committee (DGAC) reports from 2010, 2015, and 2020.

2010

The 2010–2015 DGA stated, “Moderate alcohol consumption also is associated with reduced risk of all-cause mortality among middle-aged and older adults,”1 where moderate alcohol consumption is defined as up to one

___________________

1 2010 Dietary Guidelines for Americans Report, p. 31.

drink per day for women and up to two drinks per day for men (USDA and HHS, 2010). The above statements were not referenced nor was there a systematic review of the evidence.

The 2010 DGAC report states that, compared to those who abstain, an “average daily intake of one to two alcoholic beverages is associated with the lowest all-cause mortality” (DGAC, 2010).2 The report concluded that there was no meaningful change in the research findings compared to past reports, that no new systematic reviews were warranted, and the committee reiterated the findings of past committees. For all-cause mortality, the report cited a meta-analysis (Di Castelnuovo et al., 2006) that found an inverse association of moderate alcohol consumption and total mortality with a summary relative risk estimate of 0.80 from a J-shaped curve; the lowest mortality was observed in persons with an average consumption of 1–2 drinks/day.3

2015

The 2015–2020 DGA included an appendix on alcohol, but it did not describe or quantify the association of alcohol with all-cause mortality. The emphasis in the 2015–2020 DGA was on the consideration of the energy content (calories) from alcohol consumption, where moderate intake was defined as “up to one drink per day for women and up to two drinks per day for men” (USDA and HHS, 2015).4 The 2015 DGAC report did not specifically address the association of alcohol intake with all-cause mortality (DGAC, 2015).

2020

The DGA included a chapter on alcohol and health. Consuming alcohol in moderation was defined as limiting intake to two drinks or less in a day for men and one drink or less in a day for women, when alcohol is consumed (USDA and HHS, 2020).5 The DGA stated that “evidence indicates that, among those who drink, higher average alcohol consumption is associated with an increased risk of death from all causes compared with lower average alcohol consumption” (USDA and HHS, 2020).6 The report qualified this conclusion by reiterating that cause-specific mortality may have differential associations with alcohol intake and noting that “emerging evidence suggests that even drinking within the recommended limits may increase the overall risk of death from various causes, such as from several types of cancer and some forms of cardiovascular disease” (USDA and HHS, 2020).7

___________________

2 2010 Dietary Guidelines Advisory Committee Report, pp. 5, 559–560, 362.

3 2010 Dietary Guidelines Advisory Committee Report, p. 355.

4 2015 Dietary Guidelines for Americans Report, p. 93.

5 2020 Dietary Guidelines for Americans Report, pp. x, 18, 49, 129.

6 2020 Dietary Guidelines for Americans Report, p. 49.

7 2020 Dietary Guidelines for Americans Report, p. 49.

The 2020 DGAC report included a systematic review designed to address the question “What is the relationship between alcohol consumption and all-cause mortality?” Briefly, the 2020 systematic review included studies published between January 2010 and March 2020, Mendelian randomization studies and observational studies with more than 1,000 participants; studies of participants under 21 years of age were excluded (Mayer-Davis et al., 2020). The systematic review included 60 studies (one Mendelian randomization study, one retrospective cohort study, and 58 prospective cohort studies) with no randomized controlled trials. The primary focus of the systematic review was on risk among those who consumed alcohol, including risk of binge drinking; the findings for binge drinking are not referenced here because this exposure category is not the focus of the current report. The DGAC first addressed the association of consuming more versus less alcohol among those who consumed alcohol (DGAC, 2020). The plain language summary noted, “Moderate evidence indicates higher average volume of alcohol consumption is associated with an increased risk of all-cause mortality compared with lower average alcohol consumption among those who drink”8 and that “Most studies found lower risk among men consuming within ranges up to two drinks per day and women consuming within ranges up to one drink per day compared to those consuming higher average amounts” (DGAC, 2020).9 The DGAC next addressed the question of consuming alcohol at various levels compared to never consuming alcohol, concluding, “limited evidence suggests that low average alcohol consumption, particularly without binge drinking, is associated with a lower risk of all-cause mortality compared with never drinking alcohol” (DGAC, 2020). The 2020 DGAC report cautioned that the scientific and public health concerns that are associated with alcoholic beverages should involve a careful review of the evidence when comparing never drinking alcohol to low average consumption given the biases (e.g., residual confounding) known to affect observational studies.

METHODOLOGICAL CONSIDERATIONS

All-cause mortality is often used as an outcome because it is less affected by misclassification than cause-specific mortality (Weiss, 2014), which is a strength. If the exposure, in this case alcohol consumption, affects major and multiple causes of death in the same direction (i.e., uniformly increases or decreases risk), then all-cause mortality is a sensitive outcome. However, the association of alcohol consumption with all-cause mortality will be affected by confounding bias if there is a factor that affects both the likelihood of exposure and the risk of all-cause mortality. Another methodological challenge when using all-cause mortality as an outcome in alcohol research is

___________________

8 2020 Dietary Guidelines Advisory Committee Report, p. 11.

9 2020 Dietary Guidelines Advisory Committee Report, p. 11.

that it includes deaths that are attributable to factors not related to alcohol intake (e.g., natural disasters). Counting deaths that are not causally related to alcohol consumption may lead to a dilution of any true association of alcohol consumption with mortality (e.g., underestimation of true association of moderate alcohol intake with death). Studying cause-specific mortality as an outcome might mitigate some of the above issues but raises other challenges, including misclassification of cause of death and statistical power concerns for stable estimates of association when studying rare causes of deaths.

SYSTEMATIC REVIEW

Approach

An evidence scan was completed to describe the extent of the recent published literature. The scan searched for original research studies published from January 2019 to September 2023, given that the past DGAC reviewed literature through March 2020. Thirty-four studies of alcohol and all-cause mortality were identified, including 11 published from 2018 to 2020 and 23 between 2021 and 2023; the majority were prospective cohort studies (Figure 3-1). The certainty of the evidence of the studies included in the systematic review are summarized in Table 3-1. Given the number of original studies identified in the evidence scan, the committee made the subjective decision to commission a de novo systematic review of the relationship between alcohol consumption and the risk of all-cause mortality. The committee notes that because the commissioned systematic review was limited to studies published between January 2019 to September 2023, this is not an overall review of all the evidence on this question, given the evidence base dates back over 50 years. Also, the included studies are mainly prospective epidemiologic studies of average drinking, so there are caveats related to the methodologic concerns described in Chapter 2, including the use of self-reported data on alcohol consumption, incomplete control of confounding, and challenges in harmonizing findings across different ways of assessing and categorizing alcohol consumption (AND, 2024a).

Results

The systematic review search dates were January 1, 2019, to September 22, 2023, and the search was completed on September 22, 2023. The search focused on identifying all original research studies, using a protocol to identify exclusion/inclusion criteria. The following data were extracted from each study onto a standardized template: authors; year of publication; country where the study was conducted; source of funding; duration of follow-up; sample size; years of data collection; description of alcohol consumption and how consumption of alcohol was assessed; description

NOTES: The diagram shows the number of primary articles identified from the primary article search and each step of screening. The literature dates include articles with the publications between 2019 and 2023. n = number; NLM = National Library of Medicine; PRISMA = Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses.

SOURCE: Figure E-1 in Appendix E, Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics, 2024.

of comparison group, age, sex, race/ethnicity; and confounders accounted for in analysis (Table E-2 of SR details specific confounders accounted for in each study [see Appendix E]). For quantitative results, hazard ratio (HR), risk ratio/relative risk (RR) or odds ratio (OR), and 95% confidence interval (CI) for the all-cause mortality outcome was extracted for each comparison of interest. The fully adjusted effect estimates were extracted, thus from models accounting for confounding factors.

Among the 27 included studies reported in 34 articles, only 12 had data available to assess this association and only eight of these studies

| Certainty Assessment | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Participants (studies) Follow-up | Risk of bias | Inconsistency | Indirectness | Imprecision | Publication bias | Overall certainty of evidence | Relative effect (95% CI) |

| All-Cause Mortality: Consuming Moderate Alcohol vs. Never Consumption | |||||||

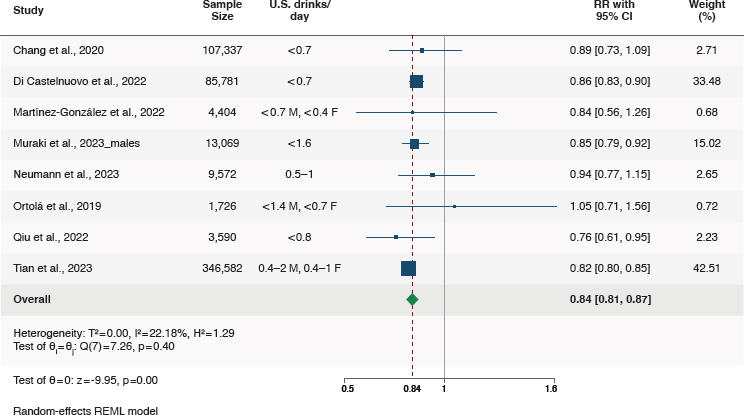

| 572,421 (8 nonrandomized studies)a | seriousb,c | not seriousc | not serious | not serious | none | moderate | RR 0.84 (0.81, 0.87) |

| All-Cause Mortality Among Moderate Alcohol Consumers: Higher vs. Lower Amounts | |||||||

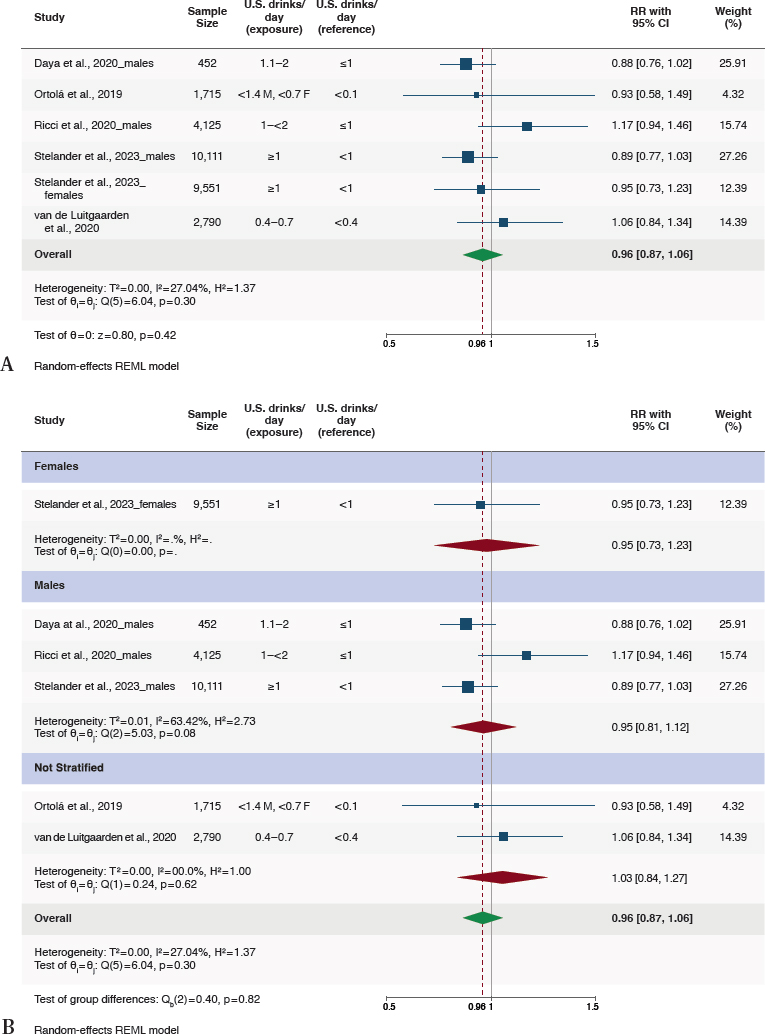

| 28,744 (5 nonrandomized studies)e | seriousb | not serious | not serious | seriousd | none | low | RR 0.96 (0.87, 1.06) |

NOTES: CI = confidence interval; RR = relative risk.

a Chang et al., 2020; Di Castelnuovo et al., 2022; Martínez-González et al., 2022; Muraki et al., 2023; Neumann et al., 2022; Ortolá et al., 2019; Qiu et al., 2022; Tian et al., 2023.

b Some concerns/high risk of bias in most included studies.

c High heterogeneity in results between studies.

d Wide confidence interval include potential benefits and harms.

e Daya et al., 2020, Ortolá et al., 2019, Ricci et al., 2020, Stelander et al., 2023, van de Luitgaarden et al., 2020.

SOURCE: Adapted from Table E-4 in Appendix E, Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics, 2024.

contributed to the overall estimate quantified in a meta-analysis (Table 3-2, Overall Results). Not all included studies had data on the risk of all-cause mortality for participants with moderate alcohol consumption compared to participants who never consumed alcohol. For this reason, eight studies contributed to the meta-analysis of this question. For a detailed description of all studies that met the inclusion criteria for the systematic review, please refer to Table E-2 in the systematic review. The eight studies that compared moderate alcohol consumption to never consuming alcohol primarily

| Category | N Studies | RR (95% CI) | I2 (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Overall Resultsa | |||

| Moderate alcohol consumptionb,c | 8 | 0.84 (0.81, 0.87)d | 22.2 |

| Subgroup Analyses According to Sex and Agea | |||

| Sex | |||

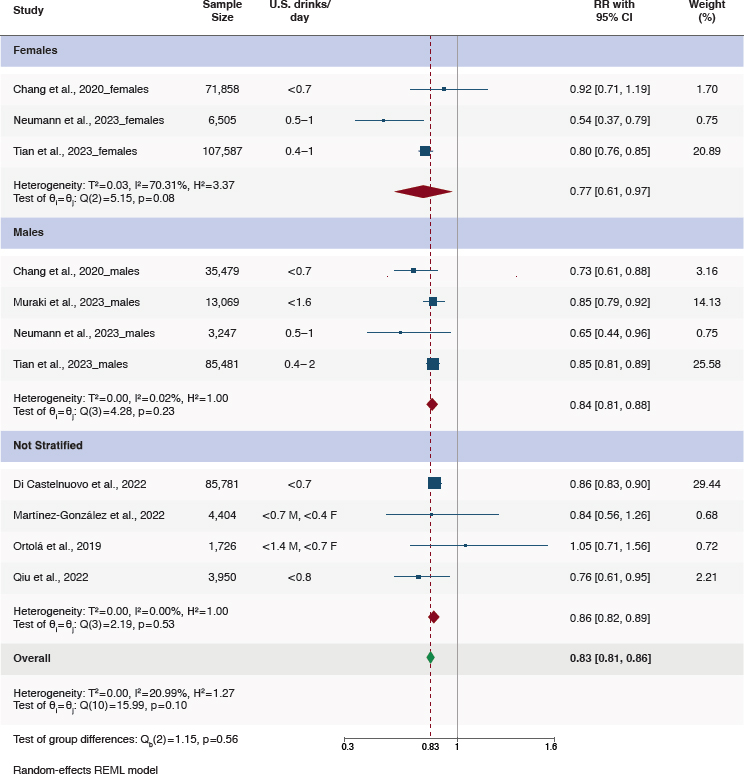

| Moderate alcohol consumptionb,c | |||

| Males | 4 | 0.84 (0.81, 0.88) | 0.02 |

| Females | 3 | 0.77 (0.60, 0.97) | 70.3 |

| Not Stratified | 4 | 0.86 (0.82, 0.89) | 0 |

| Age | |||

| Moderate alcohol consumptionb | |||

| <60 years | 2 | 0.80 (0.74, 0.86) | 8.5 |

| ≥60 years | 4 | 0.82 (0.77, 0.87) | 5.9 |

| Not Stratified | 4 | 0.84 (0.78, 0.92) | 56.8 |

NOTES: CI = confidence interval; I2 = heterogeneity; N = number; RR = relative risk.

a Meta-analyses of drinking categories were conducted using separate meta-analyses to avoid over-counting participants in comparison groups. Numbers in parentheses represent the range of alcohol consumption categories included in analysis.

b Moderate alcohol consumption is defined as: ≤1 drink/day for women and ≤2 drinks/day for men. 1 U.S. drink = 14 grams of alcohol.

c Alcohol consumption amount for included groups can be found in Figure E-3 and Annex E-2 in Appendix E.

d Results in bold are statistically significant (p < 0.05).

SOURCE: Adapted from Table E-3 in Appendix E, Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics, 2024.

NOTES: CI = confidence interval; I2 = heterogeneity; REML = restricted maximum likelihood; RR = relative risk.

SOURCES: Adapted from Figure E-3 in Appendix E, Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics, 2024.

estimated the association of consuming alcohol at the lower end of moderate alcohol consumption (Figure 3-2A). For example, five of the eight studies compared an average of about 0.7 U.S. drinks/day (8.4 g/d) with never consuming alcohol. Because of how alcohol consumption was assessed and/or categorized in the included studies, there were fewer studies that contributed to an analysis of alcohol consumption at levels closer to the upper end of moderate alcohol consumption. All eight studies were assessed for risk of bias and were considered to have “some concerns” based on risk of bias due to confounding and/or exposure measurement (Table 3-3).

Among the 27 included studies, only four had data available to assess the association of moderate alcohol consumption and all-cause mortality stratified by sex (Table 3-2 and Figure 3-2B). There were three studies with data on females and males, one study with data on males only, and four studies that did not present sex-stratified analyses (note, these eight studies are the same studies in Figure 3-2A contributing to the overall estimate). All eight studies contributing data to the main question (i.e., the association of moderate consumption of alcohol compared to never consuming alcohol on the risk of all-cause mortality) adjusted for major confounders, including age, sex, socioeconomic factors, physical activity, smoking, and typically some mixture of comorbidities and body habitus. The eight included studies had serious concerns due to risk of bias (Table 3-3, primarily due

| Study | Bias Domains assessed as “some concerns” or “high” | Overall Risk of Bias |

|---|---|---|

| Ahlner et al., 2023 | Confounding, exposure measurement, selection of participants | Some concerns |

| Armas Rojas et al., 2021 | Confounding | Some concerns |

| Barbería-Latasa et al., 2022 | Exposure measurement, selection of participants | High |

| Campanella et al., 2023 | Confounding, exposure measurement | High |

| Chang et al., 2020 | Confounding | Some concerns |

| Daya et al., 2020 | Confounding, exposure measurement | Some concerns |

| Di Castelnuovo et al., 2022; Di Castelnuovo et al., 2023 | Confounding, exposure measurement | Some concerns |

| Jankhothaew et al., 2020 | Confounding, exposure measurement, missing data | Some concerns |

| John et al., 2021 | Confounding, exposure measurement | High |

| Keyes et al., 2019 | Confounding | Some concerns |

| Liu et al., 2022 | Exposure measurement | Some concerns |

| Millwood et al., 2023 | All domains low risk of bias | Low |

| Muraki et al., 2023 | Confounding, exposure measurement | Some concerns |

| Neumann et al., 2022 | Confounding | Some concerns |

| Ortolá et al., 2019 | Exposure measurement | Some concerns |

| Patra et al., 2021 | Confounding, exposure measurement | Some concerns |

| Peeraphatdit et al., 2020 | Confounding, exposure measurement | Some concerns |

| Qiu et al., 2022 | Confounding | Some concerns |

| Ricci et al., 2020 | Confounding, missing data | High |

| Rosella et al., 2019 | Confounding | Some concerns |

| Stelander et al., 2023 | Confounding, exposure measurement | Some concerns |

| SUN Study | Confounding, exposure measurement, selection of participants | Some concerns |

| Tevik et al., 2019 | Confounding, exposure measurement, missing data | Some concerns |

| Tian et al., 2023 | Confounding | Some concerns |

| Study | Bias Domains assessed as “some concerns” or “high” | Overall Risk of Bias |

|---|---|---|

| UK Biobank | Confounding, exposure measurement | Some concerns |

| van de Luitgaarden et al., 2020 | Confounding | Some concerns |

| Ye et al., 2021 | Confounding, exposure measurement | Some concerns |

| Zhang et al., 2021 | All domains low risk of bias | Low |

NOTE: Overall risk of bias is based on seven domains: (1) confounding; (2) measurement of the exposure; (3) selection of participants into the study (or into the analysis); (4) post-exposure interventions; (5) missing data; (6) measurement of the outcome; and (7) selection of the reported results.

SOURCE: Adapted from Figure E-2 in Appendix E, Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics, 2024.

to confounding bias and/or exposure measurement bias); four studies had data available to estimate the association of moderate alcohol consumption, compared to never consuming alcohol, on all-cause mortality stratified by sex (Table 3-2 and Figure 3-2B). Limited and inconsistent data are available on the associations of beverage types and drinking patterns with risk of all-cause mortality in the context of moderate alcohol consumption, and it is unclear if such associations differ by sex and/or age.

Finding 3-1: On the basis of a meta-analysis of eight eligible studies, there was a 16 percent lower risk of all-cause mortality among those who consumed moderate levels of alcohol compared with those who never consumed alcohol (RR = 0.84, 95%CI [0.81, 0.87]).

Finding 3-2: On the basis of a meta-analysis of three eligible studies, a 23 percent lower risk of all-cause mortality was found among females who consumed moderate amounts of alcohol compared with females who never consumed alcohol (RR = 0.77, 95%CI [0.6, 0.97]). An assessment of four studies showed a 16 percent lower risk of all-cause mortality among males who consumed moderate amounts of alcohol compared with males who never consumed alcohol (RR = 0.84, 95%CI [0.81, 0.88]). The committee found no evidence for a difference in the effect size by sex, as reflected in the p-value of 0.56 for the test for heterogeneity between the sexes.

NOTES: CI = confidence interval; I2 = heterogeneity; REML = restricted maximum likelihood; RR = relative risk.

SOURCE: Figure E-3 in Appendix E, American Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics, 2024.

Finding 3-3: On the basis of a meta-analysis of two eligible studies, a 20 percent lower risk of all-cause mortality was found among persons less than 60 years of age who consumed moderate amounts of alcohol compared with persons less than 60 years of age who never consumed alcohol (RR = 0.80, 95%CI [0.74, 0.86]). An assessment of four eligible studies found an 18 percent lower risk of all-cause mortality among persons 60 years of age or older who consumed moderate amounts of alcohol compared with persons 60 years of age or older who never

consumed alcohol (RR = 0.82, 95%CI [0.77, 0.87]). The committee found no evidence for a difference in the effect size by age, as reflected in the p-value of 0.61 for the test for heterogeneity between the age groups. This comparison was not graded for certainty of the evidence.

Finding 3-4: On the basis of a meta-analysis of five studies published between 2019 and 2023, the committee found that, among moderate alcohol consumers, higher versus lower amounts of moderate alcohol consumption were associated with similar risks of all-cause mortality (RR = 0.96, 95%CI [0.87, 1.06]). The committee also found no evidence for a difference in this effect size by sex, as reflected in the p-value of 0.82 for the test for heterogeneity between the sexes.

Conclusion 3-1: Based on data from the eight eligible studies from 2019 to 2023, the committee concludes that compared with never consuming alcohol, moderate alcohol consumption is associated with lower all-cause mortality (moderate certainty).

Among the 27 included studies, six studies had data available to assess the association of moderate alcohol consumption and all-cause mortality stratified by age (Table 3-2). There were two studies with data on persons less than 60 years of age, four studies with data on persons 60 years and older, and four studies that did not present stratified analyses. These studies contributed data to estimate the association of moderate alcohol consumption, compared to never consuming alcohol, on all-cause mortality stratified by age (Table 3-2).

Because of how alcohol consumption was assessed and/or categorized in the eight included studies that contributed to the overall estimate of association (Table 3-2 and Figure 3-2A), the comparison mainly reflected alcohol consumption toward the lower end of the range defined as moderate consumption versus never consuming alcohol. There were five studies (with data on six comparisons) that contributed to an overall analysis of the risk of all-cause mortality comparing higher to lower categories of alcohol consumption, where all categories were within the range of moderate alcohol consumption (Figure 3-3). For example, Daya et al. (2020) compared mortality risk in males who consumed 1.1–2.0 U.S. drinks/day to those who consumed ≤1 U.S. drink/day. The five studies with data for this analysis were determined to have “some concerns” about risk of bias, primarily due to confounding, and one study was at high risk of bias due concerns about both confounding and bias due to missing data (Table 3-3).

Summary of Evidence Relative to Past DGA Guidance

Based on the results of the de novo systematic review, of studies published from 2019 to 2023, the committee concludes these results are consistent with prior DGAC reports, with an evidence grade of moderate

NOTES: CI = confidence interval; I2 = heterogeneity; REML = restricted maximum likelihood; RR = relative risk.

SOURCE: Figure E-6 in Appendix E, Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics, 2024.

certainty for the overall finding summarized in Conclusion 3-1. Overall, the reports from 2010, 2015, and 2020 concluded that moderate alcohol consumption, compared to never consuming alcohol, is associated with a lower risk of all-cause mortality. The SR that supported the 2020 DGAC report, which reviewed studies published from 2010 to 2020, addressed the question of consuming alcohol at various levels compared to never consuming alcohol, and concluded, “Limited evidence suggests that low average alcohol consumption, particularly without binge drinking, is associated with a lower risk of all-cause mortality compared with never drinking alcohol” (DGAC, 2020).

REFERENCES

AND (Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics). 2024a. Alcohol Consumption and All-Cause Mortality: Systematic Review. Appendix E available at https://nap.nationalacademies.org/ (accessed January 30, 2025).

Ahlner, F., H. F. Erhag, L. Johansson, J. Samuelsson, H. Wetterberg, M. M. Fassberg, M. Waern, and I. Skoog. 2023. The effect of alcohol consumption on all-cause mortality in 70-year-olds in the context of other lifestyle risk factors: Results from the Gothenburg H70 birth cohort study. BMC Geriatrics 23(1):523.

Armas Rojas, N. B., B. Lacey, D. M. Simadibrata, S. Ross, P. Varona-Perez, J. A. Burrett, M. Calderon Martinez, E. Lorenzo-Vazquez, S. Bess Constanten, B. Thomson, P. Sherliker, J. M. Morales Rigau, J. Carter, M. S. Massa, O. J. Hernandez Lopez, N. Islam, M. A. Martinez Morales, I. Alonso Aloma, F. Achiong Estupinan, M. Diaz Gonzalez, N. Rosquete Munoz, M. Cendra Asencio, J. Emberson, R. Peto, and S. Lewington. 2021. Alcohol consumption and cause-specific mortality in Cuba: Prospective study of 120,623 adults. EClinicalMedicine 33:100692.

Balbo, S., L. Meng, R. L. Bliss, J. A. Jensen, D. K. Hatsukami, and S. S. Hecht. 2012. Kinetics of DNA adduct formation in the oral cavity after drinking alcohol. Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers & Prevention 21(4):601–608.

Barbería-Latasa, M., M. Bes-Rastrollo, R. Perez-Araluce, M. A. Martiínez-Gonzalez, and A. Gea. 2022. Mediterranean alcohol-drinking patterns and all-cause mortality in women more than 55 years old and men more than 50 years old in the “Seguimiento Universidad de Navarra” (SUN) cohort. Nutrients 14(24).

Camargo, C. A., Jr., P. T. Williams, K. M. Vranizan, J. J. Albers, and P. D. Wood. 1985. The effect of moderate alcohol intake on serum apolipoproteins A-I and A-II. A controlled study. JAMA 253(19):2854–2857.

Campanella, A., C. Bonfiglio, F. Cuccaro, R. Donghia, R. Tatoli, and G. Giannelli. 2023. High adherence to a mediterranean alcohol-drinking pattern and mediterranean diet can mitigate the harmful effect of alcohol on mortality risk. Nutrients 16(1).

CDC (U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention). 2024. Leading causes of death. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/fastats/leading-causes-of-death.htm (accessed September 20, 2024).

Chang, J. Y., S. Choi, and S. M. Park. 2020. Association of change in alcohol consumption with cardiovascular disease and mortality among initial nondrinkers. Scientific Reports 10(1):13419.

Chiva-Blanch, G., E. Magraner, X. Condines, P. Valderas-Martinez, I. Roth, S. Arranz, R. Casas, M. Navarro, A. Hervas, A. Siso, M. Martinez-Huelamo, A. Vallverdu-Queralt, P. Quifer-Rada, R. M. Lamuela-Raventos, and R. Estruch. 2015. Effects of alcohol and polyphenols from beer on atherosclerotic biomarkers in high cardiovascular risk men: A randomized feeding trial. Nutrition, Metabolism and Cardiovascular Diseases 25(1):36–45.

Daya, N. R., C. M. Rebholz, L. J. Appel, E. Selvin, and M. Lazo. 2020. Alcohol consumption and risk of hospitalizations and mortality in the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities study. Alcoholism, Clinical and Experimental Research 44(8):1646–1657.

Di Castelnuovo, A., S. Costanzo, V. Bagnardi, M. B. Donati, L. Iacoviello, and G. de Gaetano. 2006. Alcohol dosing and total mortality in men and women: An updated meta-analysis of 34 prospective studies. Archives of Internal Medicine 166(22):2437–2445.

Di Castelnuovo, A., S. Costanzo, M. Bonaccio, P. McElduff, A. Linneberg, V. Salomaa, S. Mannisto, M. Moitry, J. Ferrieres, J. Dallongeville, B. Thorand, H. Brenner, M. Ferrario, G. Veronesi, E. Pettenuzzo, A. Tamosiunas, I. Njolstad, W. Drygas, Y. Nikitin, S. Soderberg, F. Kee, G. Grassi, D. Westermann, B. Schrage, S. Dabboura, T. Zeller, K. Kuulasmaa, S. Blankenberg, M. B. Donati, G. de Gaetano, and L. Iacoviello. 2022. Alcohol intake and total mortality in 142,960 individuals from the MORGAM project: A population-based study. Addiction 117(2):312–325.

Di Castelnuovo, A., M. Bonaccio, S. Costanzo, P. McElduff, A. Linneberg, V. Salomaa, S. Mannisto, J. Ferrieres, J. Dallongeville, B. Thorand, H. Brenner, M. Ferrario, G. Veronesi, A. Tamosiunas, S. Grimsgaard, W. Drygas, S. Malyutina, S. Soderberg, M. Nordendahl, F. Kee, G. Grassi, S. Dabboura, R. Borchini, D. Westermann, B. Schrage, T. Zeller, K. Kuulasmaa, S. Blankenberg, M. B. Donati, L. Iacoviello, M. S. Investigators, and G. de Gaetano. 2023. Drinking alcohol in moderation is associated with lower rate of all-cause mortality in individuals with higher rather than lower educational level: Findings from the MORGAM project. European Journal of Epidemiology 38(8):869–881.

DGAC (Dietary Guidelines Advisory Committee). 2010. Report of the Dietary Guidelines Advisory Committee on the Dietary Guidelines for Americans, 2010: To the Secretary of Agriculture and the Secretary of Health and Human Services. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Agricultural Research Service, Washington, DC. https://www.dietaryguidelines.gov/sites/default/files/2019-05/2010DGACReport-camera-ready-Jan11-11.pdf (accessed September 20, 2024).

DGAC. 2015. Scientific Report of the 2015 Dietary Guidelines Advisory Committee: Advisory Report to the Secretary of Health and Human Services and the Secretary of Agriculture. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Agricultural Research Service, Washington, DC. https://health.gov/sites/default/files/2019-09/Scientific-Report-of-the-2015-Dietary-Guidelines-Advisory-Committee.pdf (accessed September 20, 2024).

DGAC. 2020. Scientific Report of the 2020 Dietary Guidelines Advisory Committee: Advisory Report to the Secretary of Agriculture and the Secretary of Health and Human Services. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Agricultural Research Service, Washington, DC. https://www.dietaryguidelines.gov/sites/default/files/2020-07/ScientificReport_of_the_2020DietaryGuidelinesAdvisoryCommittee_first-print.pdf (accessed September 20, 2024).

Ferraguti, G., S. Terracina, C. Petrella, A. Greco, A. Minni, M. Lucarelli, E. Agostinelli, M. Ralli, M. de Vincentiis, G. Raponi, A. Polimeni, M. Ceccanti, B. Caronti, M. G. Di Certo, C. Barbato, A. Mattia, L. Tarani, and M. Fiore. 2022. Alcohol and head and neck cancer: Updates on the role of oxidative stress, genetic, epigenetics, oral microbiota, antioxidants, and alkylating agents. Antioxidants 11(1).

Fragopoulou, E., C. Argyrou, M. Detopoulou, S. Tsitsou, S. Seremeti, M. Yannakoulia, S. Antonopoulou, G. Kolovou, and P. Kalogeropoulos. 2021. The effect of moderate wine consumption on cytokine secretion by peripheral blood mononuclear cells: A randomized clinical study in coronary heart disease patients. Cytokine 146:155629.

Gepner, Y., R. Golan, I. Harman-Boehm, Y. Henkin, D. Schwarzfuchs, I. Shelef, R. Durst, J. Kovsan, A. Bolotin, E. Leitersdorf, S. Shpitzen, S. Balag, E. Shemesh, S. Witkow, O. Tangi-Rosental, Y. Chassidim, I. F. Liberty, B. Sarusi, S. Ben-Avraham, A. Helander, U. Ceglarek, M. Stumvoll, M. Bluher, J. Thiery, A. Rudich, M. J. Stampfer, and I. Shai. 2015. Effects of initiating moderate alcohol intake on cardiometabolic risk in adults with type 2 diabetes: A 2-year randomized, controlled trial. Annals of Internal Medicine 163(8):569–579.

Guidolin, V., E. S. Carlson, A. Carra, P. W. Villalta, L. A. Maertens, S. S. Hecht, and S. Balbo. 2021. Identification of new markers of alcohol-derived DNA damage in humans. Biomolecules 11(3).

Hoes, L., R. Dok, K. J. Verstrepen, and S. Nuyts. 2021. Ethanol-induced cell damage can result in the development of oral tumors. Cancers 13(15).

Jani, B. D., R. McQueenie, B. I. Nicholl, R. Field, P. Hanlon, K. I. Gallacher, F. S. Mair, and J. Lewsey. 2021. Association between patterns of alcohol consumption (beverage type, frequency and consumption with food) and risk of adverse health outcomes: A prospective cohort study. BMC Medicine 19(1):8.

Jankhotkaew, J., K. Bundhamcharoen, R. Suphanchaimat, O. Waleewong, S. Chaiyasong, K. Markchang, C. Wongworachate, P. Vathesatogkit, and P. Sritara. 2020. Associations between alcohol consumption trajectory and deaths due to cancer, cardiovascular diseases and all-cause mortality: A 30-year follow-up cohort study in Thailand. BMJ Open 10(12):e038198.

John, U., H. J. Rumpf, M. Hanke, and C. Meyer. 2021. Alcohol abstinence and mortality in a general population sample of adults in Germany: A cohort study. PLoS Medicine 18(11):e1003819.

Keyes, K. M., E. Calvo, K. A. Ornstein, C. Rutherford, M. P. Fox, U. M. Staudinger, and L. P. Fried. 2019. Alcohol consumption in later life and mortality in the United States: Results from 9 waves of the Health and Retirement Study. Alcoholism, Clinical and Experimental Research 43(8):1734–1746.

Liu, Y. T., J. H. Lee, M. K. Tsai, J. C. Wei, and C. P. Wen. 2022. The effects of modest drinking on life expectancy and mortality risks: A population-based cohort study. Scientific Reports 12(1):7476.

Ma, H., X. Li, T. Zhou, D. Sun, I. Shai, Y. Heianza, E. B. Rimm, J. E. Manson, and L. Qi. 2021. Alcohol consumption levels as compared with drinking habits in predicting all-cause mortality and cause-specific mortality in current drinkers. Mayo Clinic Proceedings 96(7):1758–1769.

Martínez-González, M. A., M. Barbería-Latasa, J. Perez de Rojas, L. J. Dominguez Rodriguez, and A. Gea Sanchez. 2022. Alcohol and early mortality (before 65 years) in the ‘Seguimiento Universidad de Navarra’ (SUN) cohort: Does any level reduce mortality? British Journal of Nutrition 127(9):1415–1425.

Masarei, J. R., I. B. Puddey, I. L. Rouse, W. J. Lynch, R. Vandongen, and L. J. Beilin. 1986. Effects of alcohol consumption on serum lipoprotein-lipid and apolipoprotein concentrations. Results from an intervention study in healthy subjects. Atherosclerosis 60(1):79–87.

Mayer-Davis, E., H. Leidy, R. Mattes, T. Naimi, R. Novotny, B. Schneeman, B. J. Kingshipp, M. Spill, N. C. Cole, and G. Butera. 2020. Alcohol Consumption and All-Cause Mortality: A Systematic Review. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Food and Nutrition Service, Center for Nutrition Policy and Promotion, Nutrition Evidence Systematic Review. https://doi.org/10.52570/NESR.DGAC2020.SR0403 (accessed September 23, 2024).

Millwood, I. Y., P. K. Im, D. Bennett, P. Hariri, L. Yang, H. Du, C. Kartsonaki, K. Lin, C. Yu, Y. Chen, D. Sun, N. Zhang, D. Avery, D. Schmidt, P. Pei, J. Chen, R. Clarke, J. Lv, R. Peto, R. G. Walters, L. Li, Z. Chen, and G. China Kadoorie Biobank Collaborative. 2023. Alcohol intake and cause-specific mortality: Conventional and genetic evidence in a prospective cohort study of 512,000 adults in China. Lancet Public Health 8(12):e956–e967.

Mizumoto, A., S. Ohashi, K. Hirohashi, Y. Amanuma, T. Matsuda, and M. Muto. 2017. Molecular mechanisms of acetaldehyde-mediated carcinogenesis in squamous epithelium. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 18(9).

Muraki, I., H. Iso, H. Imano, R. Cui, S. Ikehara, K. Yamagishi, and A. Tamakoshi. 2023. Alcohol consumption and long-term mortality in men with or without a history of myocardial infarction. Journal of Atherosclerosis and Thrombosis 30(4):415–428.

Neumann, J. T., R. Freak-Poli, S. G. Orchard, R. Wolfe, C. M. Reid, A. M. Tonkin, L. J. Beilin, J. J. McNeil, J. Ryan, and R. L. Woods. 2022. Alcohol consumption and risks of cardiovascular disease and all-cause mortality in healthy older adults. European Journal of Preventive Cardiology 29(6):e230–e232.

Ortolá, R., E. Garcia-Esquinas, E. Lopez-Garcia, L. M. Leon-Munoz, J. R. Banegas, and F. Rodriguez-Artalejo. 2019. Alcohol consumption and all-cause mortality in older adults in Spain: An analysis accounting for the main methodological issues. Addiction 114(1):59–68.

Patra, J., C. Buckley, W. C. Kerr, A. Brennan, R. C. Purshouse, and J. Rehm. 2021. Impact of body mass and alcohol consumption on all-cause and liver mortality in 240,000 adults in the United States. Drug Alcohol Review 40(6):1061–1070.

Peeraphatdit, T. B., J. C. Ahn, D. H. Choi, A. M. Allen, D. A. Simonetto, P. S. Kamath, and V. H. Shah. 2020. A cohort study examining the interaction of alcohol consumption and obesity in hepatic steatosis and mortality. Mayo Clinic Proceedings 95(12):2612–2620.

Qiu, W., A. Cai, L. Li, and Y. Feng. 2022. Longitudinal trajectories of alcohol consumption with all-cause mortality, hypertension, and blood pressure change: Results from CHNS cohort, 1993–2015. Nutrients 14(23).

Ricci, C., A. E. Schutte, R. Schutte, C. M. Smuts, and M. Pieters. 2020. Trends in alcohol consumption in relation to cause-specific and all-cause mortality in the United States: A report from the NHANES linked to the us mortality registry. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition 111(3):580–589.

Rosella, L. C., K. Kornas, A. Huang, L. Grant, C. Bornbaum, and D. Henry. 2019. Population risk and burden of health behavioral-related all-cause, premature, and amenable deaths in Ontario, Canada: Canadian Community Health Survey-linked mortality files. Annals of Epidemiology 32:49–57 e43.

Rumgay, H., N. Murphy, P. Ferrari, and I. Soerjomataram. 2021. Alcohol and cancer: Epidemiology and biological mechanisms. Nutrients 13(9).

Schaefer, S. M., A. Kaiser, I. Behrendt, G. Eichner, and M. Fasshauer. 2023. Association of alcohol types, coffee and tea intake with mortality: Prospective cohort study of UK Biobank participants. British Journal of Nutrition 129(1):115–125.

Schutte, R., M. Papageorgiou, M. Najlah, H. W. Huisman, C. Ricci, J. Zhang, N. Milner, and A. E. Schutte. 2020. Drink types unmask the health risks associated with alcohol intake - prospective evidence from the general population. Clinical Nutrition 39(10):3168-3174.

Sierksma, A., M. S. van der Gaag, C. Kluft, and H. F. Hendriks. 2002. Moderate alcohol consumption reduces plasma C-reactive protein and fibrinogen levels; A randomized, diet-controlled intervention study. European Journal of Clinical Nutrition 56(11):1130–1136.

Stamatakis, E., K. B. Owen, L. Shepherd, B. Drayton, M. Hamer, and A. E. Bauman. 2021. Is cohort representativeness passe? Poststratified associations of lifestyle risk factors with mortality in the UK biobank. Epidemiology 32(2):179–188.

Stelander, L. T., G. F. Lorem, A. Hoye, J. G. Bramness, R. Wynn, and O. K. Gronli. 2023. The effects of exceeding low-risk drinking thresholds on self-rated health and all-cause mortality in older adults: The Tromsø study 1994–2020. Archives of Public Health 81(1):25.

Stote, K. S., R. P. Tracy, P. R. Taylor, and D. J. Baer. 2016. The effect of moderate alcohol consumption on biomarkers of inflammation and hemostatic factors in postmenopausal women. European Journal of Clinical Nutrition 70(4):470–474.

Tevik, K., G. Selbaek, K. Engedal, A. Seim, S. Krokstad, and A. S. Helvik. 2019. Mortality in older adults with frequent alcohol consumption and use of drugs with addiction potential The Nord Trøndelag Health Study 2006–2008 (HUNT3), Norway, a population-based study. PLoS One 14(4):e0214813.

Tian, Y., J. Liu, Y. Zhao, N. Jiang, X. Liu, G. Zhao, and X. Wang. 2023. Alcohol consumption and all-cause and cause-specific mortality among us adults: Prospective cohort study. BMC Medicine 21(1):208.

Umar, A., F. Depont, A. Jacquet, S. Lignot, M. C. Segur, M. Boisseau, B. Begaud, and N. Moore. 2005. Effects of armagnac or vodka on platelet aggregation in healthy volunteers: A randomized controlled clinical trial. Thrombosis Research 115(1–2):31–37.

USDA (U.S. Department of Agriculture) and HHS (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services). 2010. Dietary Guidelines for Americans, 2010. https://www.dietaryguidelines.gov/sites/default/files/2019-05/DietaryGuidelines2010.pdf (accessed September 20, 2024).

USDA and HHS. 2015. 2015–2020 Dietary Guidelines for Americans. Washington, DC. https://health.gov/sites/default/files/2019-09/2015–2020_Dietary_Guidelines.pdf (accessed September 20, 2024).

USDA and HHS. 2020. Dietary Guidelines for Americans, 2020-2025. Washington, DC. https://www.dietaryguidelines.gov/sites/default/files/2021-03/Dietary_Guidelines_for_Americans_2020-2025.pdf (accessed September 20, 2024).

van de Luitgaarden, I. A. T., I. C. Schrieks, L. M. Kieneker, D. J. Touw, A. J. van Ballegooijen, S. van Oort, D. E. Grobbee, K. J. Mukamal, J. E. Kootstra-Ros, A. C. Muller Kobold, S. J. L. Bakker, and J. W. J. Beulens. 2020. Urinary ethyl glucuronide as measure of alcohol consumption and risk of cardiovascular disease: A population-based cohort study. Journal of the American Heart Association 9(7):e014324.

Vore, A. S., and T. Deak. 2022. Alcohol, inflammation, and blood-brain barrier function in health and disease across development. International Review of Neurobiology 161: 209–249.

Weiss, N. S. 2014. All-cause mortality as an outcome in epidemiologic studies: Proceed with caution. European Journal of Epidemiology 29(1):147–149.

Ye, X. F., C. Y. Miao, W. Zhang, C. S. Sheng, Q. F. Huang, and J. G. Wang. 2021. Alcohol consumption in relation to cardiovascular and non-cardiovascular mortality in an elderly male Chinese population. BMC Public Health 21(1):2053.

Zhang, Q. H., K. Das, S. Siddiqui, and A. K. Myers. 2000. Effects of acute, moderate ethanol consumption on human platelet aggregation in platelet-rich plasma and whole blood. Alcohol: Clinical Experimental Research 24(4):528–534.

Zhang, X., Y. Liu, S. Li, A. H. Lichtenstein, S. Chen, M. Na, S. Veldheer, A. Xing, Y. Wang, S. Wu, and X. Gao. 2021. Alcohol consumption and risk of cardiovascular disease, cancer and mortality: A prospective cohort study. Nutrition Journal 20(1):13.