Review of Evidence on Alcohol and Health (2025)

Chapter: 5 Cancer

5

Cancer

Alcohol has been identified as a carcinogen in humans (IARC, 1988, 2010, 2012). It is metabolized to acetaldehyde, which is also a carcinogen (IARC, 2010, 2012). Although the mechanisms of carcinogenesis of alcohol and acetaldehyde for each cancer site have not been entirely determined, both human and animal studies provide evidence of their roles in carcinogenesis as detailed below. The focus here is on what is known about the effects of moderate alcohol consumption on carcinogenesis and on cancer as an outcome.

CHOICE OF OUTCOMES

For the examination of moderate intake of alcohol in relation to cancer, the following sites were systematically reviewed: cancers of the oral cavity, pharynx, esophagus (squamous cell), colorectum (as well as colon and rectum, separately), and female breast. These sites were selected because previous reviews by the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) of the World Health Organization (WHO) and by the World Cancer Research Fund (WCRF) Continuous Update Project identified the evidence as “sufficient” (IARC) or “convincing” that alcohol is causal in the etiology of cancer at these sites (IARC, 1988, 2010, 2012; WCRF, 2018). Studies evaluating incidence of any of these cancers as outcomes, as well as those including composites of these outcomes (i.e., head and neck cancer, oropharyngeal cancer, or colorectal cancer), were included in the systematic review of moderate intake. While liver cancer

was also identified by IARC as a cancer site with sufficient evidence of causality by alcohol consumption, it was not included in the systematic review because the association for liver cancer is with heavy alcohol consumption on the order of three or more drinks per day (WCRF, 2018), which is beyond the scope of this review.

For several other cancer sites, there is more limited evidence on the association with alcohol consumption (i.e., urinary bladder, endometrial, gastric, pancreas, prostate, and thyroid cancers); for those sites, there is discussion of that evidence here but not a systematic review (Table 5-1). For the cancer sites included, the systematic review focused on cancer incidence and excluded studies that exclusively examined prevalence, cancer recurrence, cancer-related mortality, or survival. As for all the analyses, studies were excluded that did not specify that only never drinkers were included in the referent category to prevent abstainer bias. While these exclusions are more methodologically sound, the effect of abstainer bias likely differs for cancer than it does for some other outcomes. Associations of alcohol with cancer risk are likely linear and not J-shaped. Inclusion of former drinkers in a nondrinker referent would lead to an underestimation of the true association. Exclusion of studies because of concerns with abstainer bias limits the number of studies that can be evaluated and therefore limits overall conclusions regarding the effect of moderate alcohol consumption.

| Cancer Site | Publication |

|---|---|

| Head/Neck (not specified) | Hashibe et al., 2013; Im et al., 2021 |

| Thyroid | Im et al., 2021; Sen et al., 2015 |

| Lung | Im et al., 2021; Im et al., 2023 |

| Gastric | Im et al., 2021; Im et al., 2023; Yoo et al., 2021 |

| Small intestine | Boffetta et al., 2012 |

| Pancreas | Hippisley-Cox and Coupland, 2015; Im et al., 2021; Michaud et al., 2010; Naudin et al., 2018; Yoo et al., 2021 |

| Biliary tract | Im et al., 2021; Yoo et al., 2021 |

| Renal tract | Im et al., 2021 |

| Bladder | Botteri et al., 2017; Im et al., 2021 |

| Prostate | Demoury et al., 2016; Im et al., 2021; Papa et al., 2017 |

| Endometrium | Fedirko et al., 2013; Je et al., 2014 |

BIOLOGICAL PLAUSIBILITY

Direct Effects of Alcohol

Alcohol consumption has numerous biological effects, some of which can contribute to carcinogenesis, with effects depending on dose. Carcinogenic effects include production of reactive oxygen species with genotoxic effects, negative effects on folate absorption, metabolism, and excretion, with resulting effects on deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) methylation and one-carbon metabolism, negative effects on retinoid metabolism and immune function, inflammation, alteration of the oral and intestinal microbiome, and effects on circulating steroid hormone concentrations and hormone bioavailability; the hormone-related effects are particularly important in breast carcinogenesis (Brown and Hankinson, 2015; Rumgay et al., 2021; Tin Tin et al., 2024; Toh et al., 2010). Alcohol may also serve as a solvent, increasing exposure of epithelial cells in the mouth and gastrointestinal tract to other carcinogens (Ferraguti et al., 2022; Silva et al., 2020).

Congeners in alcoholic beverages may also have biologic effects, including affecting carcinogenesis, both positively and negatively. For example, polyphenols in wine may be protective with antioxidant and anti-inflammatory effects. Additionally, carcinogens including aflatoxin and heavy metals may be found in alcoholic beverages (Okaru and Lachenmeier, 2021). However, there are few studies in humans on possible effects of congeners on carcinogenesis (Ferraguti et al., 2022; Silva et al., 2020). The preponderance of the evidence is that ethanol in alcoholic beverages is the significant active agent; there is little evidence of a difference in cancer risk by beverage type (WCRF, 2018).

Acetaldehyde

The alcohol metabolite, acetaldehyde, is a highly reactive substance with DNA-damaging properties. Acetaldehyde forms adducts with DNA resulting in deleterious effects, including effects on gene transcription, genetic mutations, single and double DNA strand breaks, and induction of DNA cross-links, all of which can contribute to carcinogenesis. Other effects include the production of reactive oxidative species with genotoxic effects, induction of changes in methylation, and other epigenetic alterations (Balbo et al., 2012; Ferraguti et al., 2022; Guidolin et al., 2021; Hoes et al., 2021; Mizumoto et al., 2017; Rumgay et al., 2021).

Acetaldehyde is metabolized to acetate by aldehyde dehydrogenases (ALDH) and is then excreted or further metabolized into ketones and fatty acids. Individuals carrying a common ALDH2 genetic variant metabolize acetaldehyde more slowly, resulting in increased exposure of tissues to

reactive acetaldehyde with the potential for greater carcinogenic effects with exposure to lower amounts of alcohol consumption. The low activity ALDH2 variant is more prevalent among those of East Asian descent (Chang et al., 2017).

Breast Cancer (Female)

Breast cancer is the leading cause of cancer among women both globally and in the United States, accounting for 32 percent of all cancer diagnoses among women in the United States. Breast cancer is second only to cancer of the lung/bronchus as a source of cancer mortality, with 15 percent of cancer deaths among women resulting from breast cancer. Breast cancer is rare among men; approximately 99 percent of cases are among women (ACS, 2024). In both the IARC (IARC, 2010, 2012) and the WCRF (WCRF, 2018) systematic reviews, the data regarding the association of alcohol with female breast cancer were determined to be strong. In the WCRF review, the available evidence for postmenopausal breast cancer risk associated with alcohol consumption was categorized as strong/convincing; for premenopausal disease, the evidence was characterized as strong/probable. The WCRF review concluded that risk was increased across intake amounts and that there was not a threshold of intake for an alcohol effect on breast cancer (WCRF, 2018).

Cumulative exposure to increased circulating steroid hormone concentrations (including estradiol, estrone, androstenedione, dehydroepiandrosterone sulfate, testosterone) increases breast cancer risk (Brown and Hankinson, 2015; Shield et al., 2016; Tin Tin et al., 2024). Alcohol consumption, including moderate intake, is associated with increases in blood steroid hormone concentrations. The increases, particularly of estrogen, are likely important as mechanisms for alcohol-associated breast carcinogenesis (Tin Tin et al., 2024). Carcinogenic effects of alcohol and acetaldehyde exposure in the breast may also contribute to carcinogenesis. Alcohol dehydrogenase, enzymatically metabolizing alcohol to acetaldehyde, is expressed in breast tissue (Wright et al., 1999).

Colorectal Cancer

Colorectal cancer is among the most diagnosed cancers in the United States, accounting for 8 percent of all cancers for men and 7 percent for women (ACS, 2024). There are 152,810 new cases and 53,010 deaths from cancer of the colon and rectum combined in the United States each year. Colon cancer is more common than rectal cancer; there are 106,590 new colon cancer cases each year in the United States. These cancers affect men and women in approximately equal numbers (ACS, 2024).

In the colon and rectum, alcohol and acetaldehyde exposure contribute to increased cell proliferation, DNA adduct formation, DNA damage, oxidative stress, and epigenetic alterations (Bishehsari et al., 2019; Johnson et al., 2021). Further, there is evidence that alcohol exposure alters the microbiome in the large intestine in terms of composition and activity with effects on intestinal permeability, inflammation, and immune suppression. Alcohol negatively effects folate metabolism, which can result in altered one-carbon metabolism with implications for epigenetic alterations in the large intestine. Acetate, formed in the metabolism of acetaldehyde, may also have deleterious effects on the colon (Johnson et al., 2021).

Cancer of the Oral Cavity, Pharynx and Larynx

In the United States each year, there are approximately 58,450 new cases of cancer of the oral cavity and pharynx and about 12,230 deaths. Tumors at these sites tend to affect men more than women; about 70 percent of the incident cases and deaths for cancer at these sites combined are for men (ACS, 2024). In systematic reviews, WCRF (2018) and IARC (2010, 2012) both concluded that there was strong evidence of alcohol increasing the risk of cancer at these sites, including evidence of a dose response. Importantly, however, most of the research used to reach this conclusion was based on higher alcohol intakes. The focus here is on moderate alcohol consumption.

There are 12,650 new laryngeal cancers diagnosed and 3,880 deaths from laryngeal cancer each year in the United States (ACS, 2024). As for cancer of the oral cavity and pharynx, these tumors are more likely to occur in men than women (ACS, 2024). The determination in the systematic reviews by IARC and WCRF was that the evidence of an association between alcohol consumption and cancer of the larynx was strong (IARC, 2010, 2012; WCRF, 2018) and that the association followed a dose-response pattern. Again, the focus here is on associations with moderate alcohol consumption.

Alcohol is metabolized in the oral cavity to acetaldehyde by the oral microbiome (Hoes et al., 2021; Nieminen and Salaspuro, 2018), and the resulting salivary acetaldehyde concentration is higher than that in the blood (Stornetta et al., 2018; Yokoyama et al., 2008). Immediately following consumption, salivary acetaldehyde concentrations vary depending on the percent alcohol in the beverage consumed (Yokoyama et al., 2008), although about 1 hour after consumption, there are no differences by beverage type (Balbo et al., 2012; Yokoyama et al., 2008). Oral acetaldehyde decreases over about 3 hours (Balbo et al., 2012). There is evidence of a marked increase in acetaldehyde DNA adducts in oral cells (Guidolin et al., 2021) within 4 hours of alcohol consumption, in a dose dependent manner (Balbo et al., 2012).

There is evidence that alcohol consumption is associated with increased risk of head and neck cancer among those carrying the low activity ALDH2 gene variant that results in greater exposure to acetaldehyde (Chang et al., 2017; Du et al., 2021). The increased risk of cancer of these sites associated with slower metabolism of acetaldehyde provides evidence of a causal role of acetaldehyde exposure in the etiology of oral cavity, pharyngeal, and laryngeal cancer (Du et al., 2021; Nieminen and Salaspuro, 2018). Additional mechanisms for carcinogenesis in the oral cavity and pharynx include increased oxidation, and alcohol as a solvent, thus increasing exposures of epithelial cells to other carcinogens, including from tobacco (WCRF, 2018). Mutational signatures related to acetaldehyde exposure have been identified in head and neck tumors (Hoes et al., 2021). Alcohol and smoking are synergistic with stronger effects of alcohol among those who also smoke and stronger effects of smoking among those who also consume alcohol (WCRF, 2018).

Esophageal Cancer (Squamous Cell)

There are approximately 22,370 new cases and 16,130 deaths from esophageal cancer in the United States each year; both incident cases and deaths are predominately (about 80 percent) among men (ACS, 2024). The major types of esophageal cancer are squamous cell and adenocarcinomas, with differences in their risk factors (Grille, 2021). In previous reviews, the association with alcohol has been found for squamous cell esophageal cancer (IARC, 2010, 2012; WCRF, 2018).

For squamous cell esophageal cancer, the mechanisms for alcohol in carcinogenesis are similar to those for oral cavity and pharyngeal cancer: production of reactive oxygen species, exposure to acetaldehyde produced in the mouth, and effects of alcohol as a solvent increasing exposure to other carcinogens (Toh et al., 2010). Mutational signatures related to acetaldehyde exposure have been identified in esophageal tumors (Hoes et al., 2021).

PRIOR DGA RECOMMENDATIONS

To contextualize current findings on the association of alcohol with certain cancers, the committee summarized the Dietary Guidelines for Americans (DGA) and the Scientific Reports of the Dietary Guidelines for Americans Committees (DGAC) from 2010, 2015, and 2020 as they relate to alcohol and cancer. Past DGA recommendations and DGAC reports have varied in whether and the extent to which alcohol and cancer were specifically discussed and are described below in reports issued from 2010 to the present.

2010

The 2010–2015 DGA (USDA and HHS, 2010) recommended no more than moderate alcohol consumption, noting that alcohol consumption has been associated with both health benefits and harms. Among the harms of drinking, the only association with cancer noted by the DGA is that “moderate alcohol intake . . . is associated with increased risk of breast cancer.”

The 2010 DGAC report cited the WCRF/American Institute for Cancer Research (WCRF/AICR, 2007) in discussing the evidence base available relating alcohol consumption to the risk of cancer. Specifically, the report notes that there is substantial evidence of an association between alcohol consumption and risk of breast, colorectal, and liver cancer. While the association with colorectal cancer is described as demonstrating a dose-response relationship, it is designated as stronger in men than women and most notable among those consuming more than two drinks per day. The risk of liver cancer was noted as being elevated even among those consuming moderate amounts of alcohol, although the strength of this relationship appears to vary depending on smoking, diet, and underlying viral infections. There was also the suggestion that the association of alcohol with breast cancer may vary depending on folate status, with attenuation of the risk associated with alcohol among those with adequate status. Given this existing recent review and strength of the available evidence, the 2010 DGAC did not undertake a new systematic review investigating the association between alcohol consumption and cancer risk.

2015

The 2015–2020 DGA (USDA and HHS, 2015) included an appendix on alcohol with guidance consistent with the 2010–2015 DGA recommending that individuals who drink alcohol consume no more than a moderate amount. Specific health effects of alcohol, aside from the contribution of alcohol to overall caloric intake, were not discussed. The 2015 DGAC report (DGAC, 2015) did not include a separate review of evidence on the association between alcohol and health outcomes. However, the report found that, “evidence also suggests that alcoholic drinks are associated with increased risk for certain cancers.” The report found an increased risk of breast cancer even at moderate intakes of alcohol.

2020

The DGA (USDA and HHS, 2020) noted that “emerging evidence suggests that even drinking within the recommended limits may increase the

overall risk of death from various causes, such as from several types of cancer” and confirms the recommendation of prior versions of the DGA of no more than moderate alcohol consumption.

The 2020 DGAC report (DGAC, 2020) included a systematic review (Mayer-Davis et al., 2020) investigating the association between all-cause mortality and alcohol consumption. While cancer was not considered as a separate outcome, the contribution of cancer-specific mortality to all-cause mortality was noted. Additionally, three Mendelian randomization studies that investigated the association between head and neck, esophageal, and colorectal cancer (Lewis and Smith, 2005; Richmond and Smith, 2022) and alcohol consumption were highlighted. The conclusions of the 2020 DGAC report note that systematic reviews and professional society guidelines extant at that time identified a likely causal relationship between alcohol consumption and cancer mortality.

METHODOLOGICAL CONSIDERATIONS

There are important methodological considerations in the evaluation of evidence regarding a causal connection between alcohol and cancer, particularly for moderate alcohol consumption. It should be noted that, unlike some other outcomes for which most of the research has focused on alcohol consumption effects among those with alcohol use disorder, most of the evidence regarding alcohol consumption in relation to cancer risk comes from cohort studies that include a broad range of the population. In those studies, most of those consuming alcohol are not heavy drinkers meaning that in these large studies there is power to examine the effects of moderate consumption.

Significantly, alcohol consumption, both drinking compared with nondrinking as well as amount and pattern of consumption, is associated with other behaviors and participant characteristics, including cancer risk factors. Importantly, an association between alcohol consumption and smoking is found consistently and in many different populations (Breslow et al., 2011; Burton et al., 2023; Gapstur et al., 2012; Romieu et al., 2015; Schuit et al., 2002). Because alcohol consumption and smoking are correlated behaviors, and because smoking is such a strong risk factor for cancer at many sites, residual confounding by smoking is an issue in the determination of risk from alcohol alone. Examination of risks associated with drinking among those who never smoke can address the issue but would not assess synergism between alcohol and smoking.

While associations of alcohol consumption with other cancer risk factors are not as consistent, there is evidence of correlations of alcohol consumption with body mass index (BMI), physical activity, diet, and education (Breslow et al., 2011; Burton et al., 2023; Gapstur et al., 2012; Joseph et al.,

2022; Romieu et al., 2015; Sayon-Orea et al., 2011; Schuit et al., 2002). Further, behavioral risk factors, including alcohol consumption, tend to cluster and to be associated with socioeconomic status (Kukreti et al., 2022). Additionally, there may be other behavioral factors that are associated with moderate drinking such as increased socializing related to consumption.

Biological interactions of alcohol with other cancer risk factors are relevant for understanding the effect of alcohol on carcinogenesis. Factors including smoking; physical activity; body weight; occupational exposures; infectious agents, such as human papillomavirus; and diet, including specific nutrients such as folate and retinol, could potentially modify the association between alcohol with cancer risk. Unaddressed interactions could alter our understanding regarding how alcohol affects cancer risk (Gapstur et al., 2022). For example, there is synergy in exposures to both alcohol and tobacco smoke. The effect of the two exposures combined is greater than the sum of their individual effects for head and neck and for squamous cell esophageal cancers (Burton et al., 2024; Prabhu et al., 2014). Further, consideration of whether alcohol is consumed with meals or not may affect the effect of consumption on cancer risk.

A further challenge in understanding the effects of moderate alcohol consumption on cancer risk is that relationships may differ for different cancer subtypes. For example, there is evidence that alcohol is associated with estrogen receptor-positive but not estrogen receptor-negative breast cancer (WCRF, 2018). Other modifying factors would include genetic variation in alcohol metabolism, particularly ALDH2, as well as other variants, such as in DNA repair genes.

Finally, the effect of abstainer bias differs for cancer compared to some other outcomes. If associations of alcohol with risk of cancer incidence are linear and not J-shaped, with increased risk among light and moderate drinkers, the inclusion of former drinkers compared to nondrinkers in a nondrinker referent group would lead to an underestimation of the true association. Excluding former drinkers from the nondrinker group reduces bias. The committee therefore excluded studies subject to this abstainer bias from our systematic review. However, this exclusion necessarily limits the studies that are included and potentially limits the strength of overall conclusions regarding the effects of moderate consumption.

SYSTEMATIC REVIEW

Approach

Prior systematic reviews conducted by the Nutrition Evidence Systematic Review (NESR) to inform DGAC have not considered cancer incidence as a distinct outcome. However, cancer has been considered as a component

contributing to all-cause mortality. A systematic review was conducted for the 2020 DGAC, which focused on all-cause mortality as the outcome of interest (DGAC, 2020).

An initial evidence scan was conducted to provide the committee with an overview of the literature focusing on the association between low and moderate alcohol consumption and cancer incidence to inform decision making regarding the feasibility of conducting a full systematic review. A total of 77 primary articles focusing on the relationship between moderate alcohol consumption and cancer risk published between 2019 and 2023 were identified in the initial evidence scan and went through full-text screening by members of the committee, which resulted in 25 articles that met full inclusion criteria (see Chapter 2 and Appendix G for complete details of the evidence scan). An additional evidence scan was undertaken to identify prior systematic reviews of the association between alcohol and cancer risk in the period 2010–2024 (Figure 5-1).

Based on the scope of primary literature identified in preliminary evidence scans that has not been included in prior high-quality systematic reviews, the committee decided to proceed with a systematic review to answer the question regarding alcohol and cancer incidence. This systematic review included articles published between 2010 and 2024. The committee developed a systematic review protocol including an analytic framework that described the overall scope of the review including the population, types of analyses, data sources, and definitions of key terms (see Chapter 2). Aside from specifications relating to the outcome, all elements of this protocol were standardized (AND, 2024).

Results

Breast (Female) Cancer

In the meta-analysis of breast cancer, there were five studies identified of associations between moderate alcohol consumption compared to never consuming alcohol with breast cancer risk in women: four cohort studies (Kawai et al., 2011; Klatsky et al., 2015; Li et al., 2010; White et al., 2017) and one case-control study (Zhang et al., 2011). Results from the two study designs were analyzed separately.

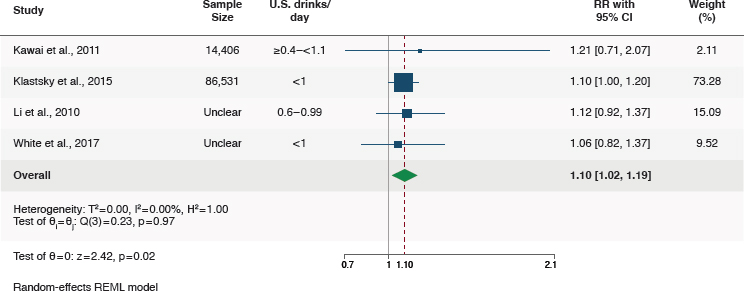

For the four cohort studies, compared to those who did not consume alcohol (lifetime abstainers), those who consumed moderate alcohol had higher risk of breast cancer (RR = 1.10, 95%CI [1.02, 1.19]; I2 = 0%) (Figure 5-2).

None of the included studies reported results stratified by age, race/ethnicity, or smoking status. In sensitivity analyses of a fixed effects model instead of a random effects model, results were similar. Sensitivity analysis of

NOTES: The diagram shows the number of primary articles identified from the primary article and systematic review searches and each step of screening. The literature dates include articles with the publications between 2010 and 2024. n = number; NLM = National Library of Medicine; PRISMA = Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses.

SOURCE: Annex G-3 in Appendix G, Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics, 2024.

data stratified on menopausal status was not feasible because of differences in reports of alcohol exposure groups. In two cohorts, results were provided stratified on menopausal status; there were no differences in the association of moderate alcohol with breast cancer risk by menopausal status in those studies (Kawai et al., 2011; White et al., 2017). In the study by Li et al. (2010) of postmenopausal women, results were similar to meta-analysis results.

NOTES: CI = confidence interval; I2 = heterogeneity; REML = restricted maximum likelihood; RR = relative risk.

SOURCE: Figure G-1 in Appendix G, Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics, 2024.

Case-control studies were examined separately from the cohort meta-analysis. There was only one case-control study examining the association between moderate alcohol consumption and odds of breast cancer that met the inclusion criteria. Zhang et al. (2011), in a study of women in China, reported lower risk of breast cancer for those who consumed <5 grams/day (0.36 U.S. drinks/day) of alcohol compared to those who never consumed alcohol (OR = 0.56, 95%CI [0.45, 0.69]). There was no significant difference in analyses by menopausal status. For this study, there were concerns related to possible bias.

Women who consumed alcohol in moderation (≤1 U.S. drink/day) likely have a higher risk of breast cancer than women who never consumed alcohol. Evidence certainty was moderate due to some concerns of risk of bias in all included studies.

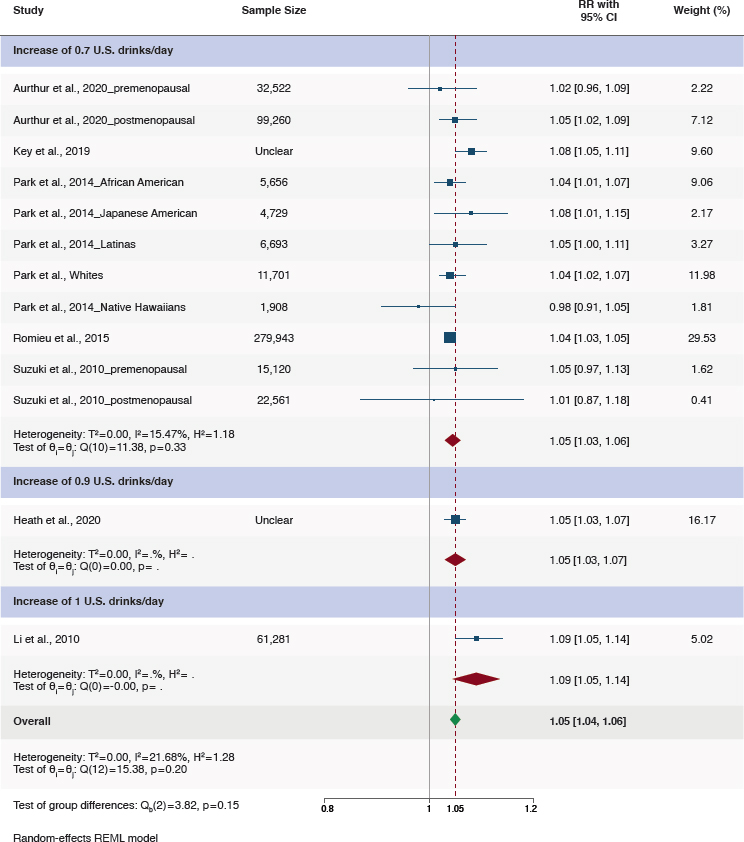

The relationship between alcohol as a continuous variable and breast cancer risk was examined in seven studies meeting the inclusion criteria. Risk was examined associated with each increase of alcohol consumption of 10–14 grams/day (Arthur et al., 2020; Heath et al., 2020; Key et al., 2019; Li et al., 2010; Park et al., 2014; Romieu et al., 2015; Suzuki et al., 2010). When these seven studies were pooled in meta-analysis, there was a higher risk of breast cancer for every 10–14 gram (0.7–1 U.S. drinks) increase in alcohol consumption per day (RR = 1.05, 95%CI [1.04, 1.06]; I2 = 21.7%) (Figure 5-3). These studies included ones based on reports of baseline consumption such that those reporting no drinking may include former drinkers. Rainey et al. (2020) reported adjusted results as odds ratios and could not be included in meta-analysis, but results were consistent with the meta-analysis (OR = 1.09, 95%CI [1.0, 1.18]). While these

NOTES: CI = confidence interval; REML = restricted maximum likelihood; RR = relative risk.

SOURCE: Figure G-7 in Appendix G, Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics, 2024.

results include intakes greater than those recommended in the DGA, they were included because they provide insight regarding the overall association of breast cancer with risk. There is no evidence of a J-shaped association; rather, the association appears to be linear with increased risk at all consumption amounts.

Two studies provided results stratified on menopausal status (Arthur et al., 2020; Suzuki et al., 2010). In postmenopausal women, the association between alcohol consumption as a continuous variable and breast cancer was consistent with results for all women (RR = 1.05, 95%CI [1.01, 1.08]; I2 = 0%); in premenopausal women, the association was similar but the confidence interval included the null (RR = 1.03, 95%CI [0.98, 1.08]; I2 = 0.04). There were some concerns regarding bias for all the included studies. Evidence certainty was moderate due to risk of bias in the included studies (Table 5-2). The certainty of the evidence of the studies included in the systematic reviews are summarized in Table 5-3.

There were two studies examining the risk of breast cancer associated with higher compared to lower intakes of alcohol among those with moderate alcohol intakes (Key et al., 2019; Romieu et al., 2015) (Figure 5-4). The committee based its conclusions on the two studies that were available, deemed to have sufficient power but downgraded the level of certainty to low.

| Study | Bias Domains assessed as “some concerns” or “high” | Overall Risk of Bias |

|---|---|---|

| Arthur et al., 2020 | Exposure measurement | Some concerns |

| Heath et al., 2020 | Exposure measurement | Some concerns |

| Kawaii et al., 2011 | Exposure measurement | Some concerns |

| Key et al., 2019 | Confounding, exposure measurement | Some concerns |

| Klatsky et al., 2015 | Exposure measurement | Some concerns |

| Li et al., 2010 | Confounding, exposure measurement | Some concerns |

| Park et al., 2014 | All domains low risk of bias | Low |

| Rainey et al., 2020 | Confounding, exposure measurement | Some concerns |

| Romieu et al., 2015 | Confounding, exposure measurement | Some concerns |

| White et al., 2017 | Confounding, exposure measurement | Some concerns |

NOTES: Overall risk of bias is based on seven domains: (1) confounding; (2) measurement of the exposure; (3) selection of participants into the study (or into the analysis); (4) post-exposure interventions; (5) missing data; (6) measurement of the outcome; and (7) selection of the reported results.

SOURCE: Adapted from Annex G-6 in Appendix G, Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics, 2024.

NOTES: CI = confidence interval; REML = restricted maximum likelihood; RR = relative risk.

SOURCE: Figure G-4 in Appendix G, Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics, 2024.

In both studies, there was increased risk for the higher intakes among moderate consumption: in the study by Key et al. (2019), for those drinking 0.6–1.1 compared to 0.2–0.5 drinks per day, (HR = 1.05, 95%CI [1.02, 1.09]) and in the study by Romieu et al. (2015) comparing, 0.4–1.1 to ≤0.4, (HR = 1.06, 96%CI [1.01, 1.11]). The overall association was 1.05 (1.02–1.08).

Finding 5-1: A meta-analysis of four eligible studies found a 10 percent higher risk of breast cancer among persons consuming moderate amounts of alcohol compared with persons never consuming alcohol (RR = 1.10, 95%CI [1.02, 1.19]). There were some concerns related to risk of bias, mainly due to confounding and exposure assessment, in the studies contributing to this comparison.

Finding 5-2: A meta-analysis of seven eligible studies found a 5 percent higher risk of breast cancer for every 10–14 grams (0.7–1.0 U.S. drinks) increment of higher alcohol consumption per day (RR = 1.05, 95%CI [1.04, 1.06]). On the basis of two eligible studies, consumption of higher compared to lower amounts of moderate alcohol was associated with a higher risk of breast cancer. One study reported a hazard ratio (HR) of 1.05 (95%CI [1.02, 1.09]) for women who consumed higher amounts of moderate alcohol (0.6–<1.1 drinks/day) compared with those who consumed lower amounts of moderate alcohol 0.2-0.5 drinks/day. Another study reported an HR of 1.06 (95%CI [1.01, 1.11]) for breast cancer associated with 0.4–1.1 drinks per day compared to <0.4 drinks per day. There were some concerns related to risk of bias, mainly due to confounding and exposure assessment.

| Certainty Assessment | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Participants (Studies) Follow-up | Risk of Bias | Inconsistency | Indirectness | Imprecision | Publication Bias | Overall Certainty of Evidence |

| Breast Cancer Consuming in Moderation vs. Never Consuming | ||||||

| 100,937+ (4 nonrandomized studies)b | seriousa | not serious | not serious | not serious | none | moderate |

| Breast Cancer Consuming Above Moderation vs. Never Consuming | ||||||

| 94,333+ (6 nonrandomized studies)c | seriousa | not serious | not serious | not serious | none | moderate |

| Breast Cancer Consuming Higher vs. Lower Alcohol Amounts in Moderation | ||||||

| 225,293+ (2 nonrandomized studies)d | seriousa | not serious | not serious | not serious | none | moderate |

| Breast Cancer Consuming Above Moderate Amounts vs. Lower Amounts in Moderation | ||||||

| 164,272+ (3 nonrandomized studies)e | seriousa | not serious | not serious | not serious | none | moderate |

| Breast Cancer and Increased Alcohol Consumption of 10–14 grams/day | ||||||

| 409,592+ (7 nonrandomized studies)f | seriousa | not serious | not serious | not serious | none | moderate |

a Some concerns of bias in most included studies.

b Kawai et al., 2011; Klatsky et al., 2015; Li et al., 2010; White et al., 2017.

c Basset et al., 2022; Kawai et al., 2010; Klatsky et al., 2015; Li et al., 2010; Suzuki et al., 2010; White et al., 2017.

d Key et al., 2019; Romieu et al., 2015.

e Heberg et al., 2019; Key et al., 2019; Romieu et al., 2015.

f Arthur et al., 2020; Key et al., 2019; Park et al., 2014; Romieu et al., 2015; Suzuki et al., 2010; Heath et al, 2020; Li et al., 2010.

SOURCE: Adapted from Table G-3 in Appendix G, Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics, 2024.

Conclusion 5-1: The committee concludes that compared with never consuming alcohol, consuming a moderate amount of alcohol was associated with a higher risk of breast cancer (moderate certainty).

Conclusion 5-2: The committee concluded that, among moderate alcohol consumers, higher versus lower amounts of moderate alcohol consumption were associated with a higher risk of breast cancer (low certainty).

Colorectal Cancer

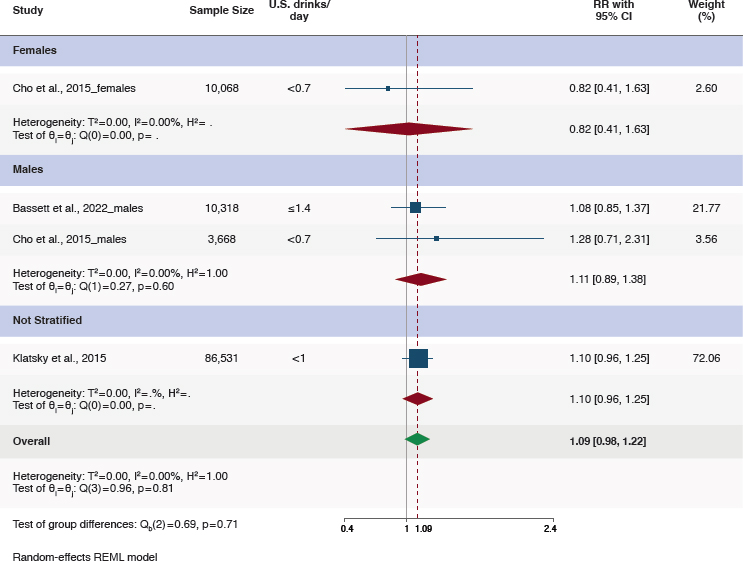

Five studies examined the relationship between alcohol consumption and colorectal cancer (Bassett et al., 2022; Cho et al., 2015; Jin et al., 2023; Klatsky et al., 2015; Murphy et al., 2019). Three studies compared moderate alcohol consumption to never consuming alcohol (Basset et al., 2022; Cho et al., 2015; Klatsky et al., 2015) (Figure 5-5). Klatsky et al. (2015) found that individuals consuming <1 drink per day had an HR of 1.10 (95%CI [0.96, 1.25]) for colorectal cancer compared to never drinkers. In an Australian study (Bassett et al., 2022) stratified by sex, men who were moderate drinkers were estimated to have an HR of 1.12 (95%CI [0.85, 1.48]). Alcohol consumption categories for women in this study did not include a category that aligns with moderate consumption. A Korean study (Cho et al., 2015) stratified by sex found that men who drank <10 grams/day (<0.7 drinks/day) had an HR of 1.28 (95%CI [0.71, 2.31]) and women had an HR of 0.82 (95%CI [0.41, 1.63]) compared to never drinkers.

Although point estimates from these studies indicate a consistent positive association between moderate alcohol consumption and risk of colorectal cancer in men, none reached statistical significance. A meta-analysis of these three studies found a nonstatistically significant positive association between moderate alcohol consumption and risk of colorectal cancer (RR = 1.09, 95%CI [0.98, 1.22]) (Figure 5-5 and Table 5-4). These studies were rated as having some concerns of risk of bias (Bassett et al., 2022; Klatsky et al., 2015) or high risk of bias (Cho et al., 2015) (Table 5-5).

Two studies examined the association between alcohol consumption and colorectal cancer risk among alcohol consumers (Jin et al., 2023; Murphy et al., 2019). The committee based its conclusions on two studies available for colorectal cancer deemed to have sufficient power but downgraded the level of certainty to low. Jin et al. (2023) examined alcohol exposure as a categorical variable and found that, after adjustment for confounding, men consuming higher amounts (0.7–<2.1 drinks/day) had higher risk of colorectal cancer compared to those consuming lower amounts (<0.7 drinks/day) (HR = 1.09, 95%CI [1.02, 1.17]) (Figure 5-5). No results for women consuming alcohol within the moderate range were reported.

| Category | N Studies | RR (95% CI) | I2 (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Overall Resultsa | |||

| Moderate Alcohol Consumptionb,c | 3 | 1.09 [0.98, 1.22] | 0 |

| Subgroup Analysis by Sexa | |||

| Moderate Alcohol Consumptionb,c | |||

| Females | 1 | 0.82 [0.41, 1.63] | N/A |

| Males | 2 | 1.11 [0.89, 1.38] | 0 |

| Not Stratified | 1 | 1.10 [0.96, 1.26] | N/A |

NOTES: CI = confidence interval; I2 = heterogeneity; N = number; N/A = Not Applicable; RR = relative risk.

a Meta-analyses of drinking categories were conducted using separate meta-analyses to avoid over-counting participants in comparison groups.

b Moderate levels are ≤1 drink/day for women and ≤2 drinks/day for men. 1 U.S. drink = 14 grams of alcohol.

c Alcohol consumption amount for included groups can be found in Figure 10 and Methods Appendix 2.

SOURCE: Adapted from Table G-8 in Appendix G, Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics, 2024.

| Study | Bias Domains assessed as “some concerns” or “high” | Overall Risk of Bias |

|---|---|---|

| Bassett et al., 2022 | Exposure measurement | Some concerns |

| Cho et al., 2015 | Confounding, exposure measurement | High |

| Jin et al., 2023 | Confounding, exposure measurement | Some concerns |

| Klatsky et al., 2015 | Exposure measurement | Some concerns |

| Murphy et al., 2019 | Confounding, exposure measurement | Some concerns |

NOTES: Overall risk of bias is based on seven domains: (1) confounding; (2) measurement of the exposure; (3) selection of participants into the study (or into the analysis); (4) post-exposure interventions; (5) missing data; (6) measurement of the outcome; and (7) selection of the reported results.

SOURCE: Adapted from Annex G-6 in Appendix G, Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics, 2024.

NOTES: CI = confidence interval; I2 = heterogeneity; REML = restricted maximum likelihood; RR = relative risk.

SOURCE: Figure G-8 in Appendix G, Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics, 2024.

Murphy et al. (2019) examined alcohol consumption as a continuous variable and found that each 15 grams/day (1.1 U.S. drinks/day) higher alcohol consumption was associated with a 1.05 times higher hazard of colorectal cancer (95%CI [1.03, 1.07]). Evidence certainty was low due to risk of bias in the included studies. The certainty of the evidence of the studies included in the systematic reviews are summarized in Table 5-6.

Finding 5-3: On the basis of five eligible studies and a meta-analysis of three of these studies, compared with never drinkers, moderate alcohol consumption was associated with a statistically nonsignificant higher risk of colorectal cancer overall among males and females. There were some concerns with the studies related to risk of bias, mainly due to confounding and exposure assessment.

Finding 5-4: On the basis of two eligible studies, consumption of higher amounts of moderate alcohol was associated with a higher

| Certainty Assessment | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Participants (Studies) Follow-up | Risk of Bias | Inconsistency | Indirectness | Imprecision | Publication Bias | Overall Certainty of Evidence |

| Colorectal Cancer Consuming Moderately vs. Never Consuming | ||||||

| 106,917 (3 nonrandomized studies)d | seriousa | not serious | not serious | seriousb | none | low |

| Colorectal Cancer Consuming Above Moderate Alcohol Consumption vs. Never Consuming | ||||||

| 50,894 (3 nonrandomized studies)d | seriousa | not serious | not serious | not serious | none | moderate |

| Colorectal Cancer Consuming Higher vs. Lower Amounts Within Moderate Alcohol Consumption | ||||||

| 1,981,807 (1 nonrandomized study)e | seriousa | not serious | seriousc | not serious | none | low |

| Colorectal Cancer Consuming Above DGAs vs. Lower Amounts Within Moderate Alcohol Consumption | ||||||

| 1,644,833 (1 nonrandomized study)f | seriousa | not serious | not serious | seriousb | none | low |

a Some concerns of bias in most included studies.

b Wide confidence interval include potential benefits and harms.

c Only reported alcohol consumption within moderate alcohol consumption for males.

d Bassett et al., 2022; Cho et al., 2015; Klatsky et al., 2015.

SOURCE: Adapted from Table G-9 in Appendix G, Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics, 2024.

risk of colorectal cancer. One study reported an HR of 1.09 (95%CI [1.02, 1.17]) for colorectal cancer among males who consumed higher amounts of moderate alcohol (0.7–<2.1 drinks/day) compared with males who consumed lower amounts of moderate alcohol (<0.7 drinks/day). Another study reported a HR of 1.05 (95%CI [1.03, 1.07]) for colorectal cancer associated with each 15 grams (1.1 U.S. drinks) increment of higher alcohol consumption per day. There were some concerns related to risk of bias (mainly due to confounding), exposure assessment, and indirectness stemming from estimating linear trends based on alcohol consumption that may have exceeded the moderate range in some individuals in the latter study.

Conclusion 5-3: The committee determined that no conclusion could be drawn regarding the association between moderate alcohol consumption compared with lifetime nonconsumers and risk of colorectal cancer.

Conclusion 5-4: The committee concluded that among moderate alcohol consumers higher versus lower amounts of moderate alcohol consumption were associated with a higher risk of colorectal cancer (low certainty).

Oral Cavity, Pharyngeal, Esophageal, and Laryngeal Cancers

There were few studies identified meeting the inclusion criteria examining the association between moderate alcohol consumption compared to lifetime abstention for risk of oral, pharyngeal, esophageal, and laryngeal cancers. While four cohort studies (Im et al., 2023; Klatsky et al., 2015; Radoï et al., 2013; Steevens et al., 2010) met the inclusion criteria, there were fewer on any one of the cancer sites. Meta-analysis of evidence for these cancer sites was not conducted.

Briefly, findings from those studies were as follows. In one study of participants in a health plan in the United States, results were reported for upper airway digestive cancers as a group (Klatsky et al., 2015). They reported a nonsignificant increased risk associated with intakes of less than 1 drink per day (RR = 1.1, 95%CI [0.8, 1.6]) but increased risk associated with 1–2 drinks per day (RR = 1.5, 95%CI [1.1, 2.3]); both comparisons to lifetime abstention. Results were not stratified by sex. The study included 52 percent women; the latter category of consumption of 1–2 drinks per day would be above moderate alcohol consumption for them. In a cohort study among Chinese men examining cancers of the oral cavity and pharynx combined, intake of less than 10 drinks per week was associated with reduced risk (RR = 0.68, 95%CI [0.49, 0.93]) (Im et al., 2023).

Radoï et al. (2013) conducted a cohort study in France of cancer of the oral cavity. They reported on risk associated with consumption of individual beverages. They found no association of risk of these cancers with consumption of one or fewer drinks per day of wine, beer, spirits, or apéritif; consumption of one glass or fewer of cider was associated with reduced risk (RR = 0.6, 95%CI [0.4, 0.9]) compared to lifetime never drinkers. They also examined the interaction of smoking and alcohol. For those consuming less than or equal to two drinks per day, risk of oral cancer was increased with moderate alcohol consumption among those who had ever smoked for 30 years or longer; it was not increased among those smoking for a shorter time. The study was 80 percent males; two or more drinks per day would be above moderate alcohol consumption for women in the study (Radoï et al., 2013).

There were two studies identified that examined moderate consumption of alcohol in association with squamous cell esophageal cancer (Im et al., 2023; Steevens et al., 2010). In a cohort study in the Netherlands, neither alcohol consumption of less than 5 grams/day was associated with risk (RR = 0.85, 95%CI [0.42, 1.73]) nor was consumption of 5–15 grams/day (RR = 1.65, 95%CI [0.85, 3.17]). At intakes of approximately 1–2 drinks per day, 15–30 grams/day, alcohol consumption was associated with increased risk (RR = 2.11, 95%CI [1.09, 4.14]). This study included both men and women; intakes in the latter category would be above moderate alcohol consumption for women. In a second study of squamous cell esophageal cancer in Chinese men, Im et al. (2023) reported no association between moderate alcohol consumption of less than 10 drinks per week (RR = 0.94, 95%CI [0.79, 1.11]). In that study, they also found no association of that amount of drinking with cancer of the larynx (RR = 1.35, 95%CI [0.89, 2.07]).

Finding 5-5: There was insufficient evidence to support an association between moderate alcohol consumption and risks of oral cavity, pharyngeal, esophageal, and laryngeal cancers.

Conclusion 5-5: The committee determined that no conclusion could be drawn regarding an association between moderate alcohol consumption and oral cavity, pharyngeal, esophageal, or laryngeal cancers.

Other Types of Cancer with Emerging Evidence Regarding Alcohol Consumption

The evidence scan conducted for the committee identified several cancers for which there appears to be an emerging body of evidence regarding moderate consumption. Specifically, studies of the relationship between moderate alcohol consumption and each of bladder, endometrial, gastric,

pancreas, prostate, lung, and thyroid cancer as well as several studies that examined combined sites such as the head and neck, biliary tract, and renal tract (14 studies in total) were identified in the evidence scan (Table 5-1). A systematic review for these cancer sites was not conducted owing to the small number of studies per cancer type. The committee evaluated this body of evidence and concluded that there was insufficient evidence to establish certainty for an association of moderate alcohol consumption with any of these other sites. Additional research may provide more information for evaluation in the future.

Finding 5-6: Upon evaluating the body of evidence, there were several sites where there was emerging evidence that was insufficient to establish certainty for an association of moderate alcohol consumption. These sites included cancer of the head and neck, thyroid, lung, gastric, small intestine, pancreas, biliary tract, renal track, bladder, prostate, and endometrium.

Summary of Evidence Relative to Past DGA Guidance

Breast Cancer

Based on the results of the de novo systematic review (SR), of studies published from 2010 to 2024, the committee concludes the results for breast cancer are consistent with the 2015 DGAC report that moderate alcohol consumption was associated with an increased risk of breast cancer. The committee finding, summarized in Conclusion 5-1, had an evidence grade of moderate certainty. Although the 2010 and the 2020 DGAC reports did not directly evaluate the associations between moderate alcohol consumption and cancer outcomes with a systematic review, the reports referred to extant guidelines, other publications, and a review of all-cause mortality to assert the association of alcohol consumption with the risk of cancers, including breast, colorectal, and liver cancer.

Colorectal Cancer

Based on the results of the de novo SR, of studies published from 2010 to 2024, the committee concludes the findings for colorectal cancer are consistent with the prior DGAC reports with an evidence grade of low certainty for the finding summarized in Conclusion 5-4. In comparisons of lower versus higher consumption of alcohol within the range of moderate alcohol consumption the committee found higher amounts of moderate alcohol consumption were associated with a higher risk of colorectal cancer, similar to findings reported in the 2010 DGAC report.

REFERENCES

ACS (American Cancer Society). 2024. Cancer facts & figures 2024. https://www.cancer.org/content/dam/cancer-org/research/cancer-facts-and-statistics/annual-cancer-facts-andfigures/2024/2024-cancer-facts-and-figures-acs.pdf (accessed September 24, 2024).

AND (Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics). 2024. Alcohol Consumption and Cancer Outcomes: Systematic Review. Appendix G available at https://nap.nationalacademies.org/catalog/28582 (accessed January 30, 2025).

Arthur, R. S., T. Wang, X. Xue, V. Kamensky, and T. E. Rohan. 2020. Genetic factors, adherence to healthy lifestyle behavior, and risk of invasive breast cancer among women in the UK Biobank. JNCI: Journal of the National Cancer Institute 112(9):893–901.

Balbo, S., L. Meng, R. L. Bliss, J. A. Jensen, D. K. Hatsukami, and S. S. Hecht. 2012. Kinetics of DNA adduct formation in the oral cavity after drinking alcohol. Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers & Prevention 21(4):601–608.

Bassett, J. K., R. J. MacInnis, Y. Yang, A. M. Hodge, B. M. Lynch, D. R. English, G. G. Giles, R. L. Milne, and H. Jayasekara. 2022. Alcohol intake trajectories during the life course and risk of alcohol-related cancer: A prospective cohort study. International Journal of Cancer 151(1):56–66.

Bishehsari, F., L. Zhang, R. M. Voigt, N. Maltby, B. Semsarieh, E. Zorub, M. Shaikh, S. Wilber, A. R. Armstrong, S. S. Mirbagheri, N. Z. Preite, P. Song, A. Stornetta, S. Balbo, C. B. Forsyth, and A. Keshavarzian. 2019. Alcohol effects on colon epithelium are time-dependent. Alcoholism, Clinical and Experimental Research 43(9):1898–1908.

Boffetta, P., W. D. Hazelton, Y. Chen, R. Sinha, M. Inoue, Y. T. Gao, W. P. Koh, X. O. Shu, E. J. Grant, I. Tsuji, Y. Nishino, S. L. You, K. Y. Yoo, J. M. Yuan, J. Kim, S. Tsugane, G. Yang, R. Wang, Y. B. Xiang, K. Ozasa, M. Nagai, M. Kakizaki, C. J. Chen, S. K. Park, A. Shin, H. Ahsan, C. X. Qu, J. E. Lee, M. Thornquist, B. Rolland, Z. Feng, W. Zheng, and J. D. Potter. 2012. Body mass, tobacco smoking, alcohol drinking and risk of cancer of the small intestine—A pooled analysis of over 500,000 subjects in the Asia Cohort Consortium. Annals of Oncology 23(7):1894–1898.

Botteri, E., P. Ferrari, N. Roswall, A. Tjonneland, A. Hjartaker, J. M. Huerta, R. T. Fortner, A. Trichopoulou, A. Karakatsani, C. La Vecchia, V. Pala, A. Perez-Cornago, E. Sonestedt, F. Liedberg, K. Overvad, M. J. Sanchez, I. T. Gram, M. Stepien, L. Trijsburg, L. Borje, M. Johansson, T. Kuhn, S. Panico, R. Tumino, H. B. A. Bueno-de-Mesquita, and E. Weiderpass. 2017. Alcohol consumption and risk of urothelial cell bladder cancer in the European prospective investigation into cancer and nutrition cohort. International Journal of Cancer 141(10):1963–1970.

Breslow, R. A., C. M. Chen, B. I. Graubard, and K. J. Mukamal. 2011. Prospective study of alcohol consumption quantity and frequency and cancer-specific mortality in the U.S. population. American Journal of Epidemiology 174(9):1044–1053.

Brown, S. B., and S. E. Hankinson. 2015. Endogenous estrogens and the risk of breast, endometrial, and ovarian cancers. Steroids 99(Pt A):8–10.

Burton, R., C. Sharpe, N. Sheron, C. Henn, S. Knight, V. M. Wright, and M. Cook. 2023. The prevalence and clustering of alcohol consumption, gambling, smoking, and excess weight in an English adult population. Preventive Medicine 175:107683.

Burton, R., P. T. Fryers, C. Sharpe, Z. Clarke, C. Henn, T. Hydes, J. Marsden, N. Pearce-Smith, and N. Sheron. 2024. The independent and joint risks of alcohol consumption, smoking, and excess weight on morbidity and mortality: A systematic review and meta-analysis exploring synergistic associations. Public Health 226:39–52.

Chang, J. S., J. R. Hsiao, and C. H. Chen. 2017. ALDH2 polymorphism and alcohol-related cancers in Asians: A public health perspective. Journal of Biomedical Science 24(1):19.

Cho, S., A. Shin, S. K. Park, H. R. Shin, S. H. Chang, and K. Y. Yoo. 2015. Alcohol drinking, cigarette smoking and risk of colorectal cancer in the Korean multi-center cancer cohort. Journal of Cancer Prevention 20(2):147–152.

Demoury, C., P. Karakiewicz, and M. E. Parent. 2016. Association between lifetime alcohol consumption and prostate cancer risk: A case-control study in Montréal, Canada. Cancer Epidemiology 45:11–17.

DGAC (Dietary Guidelines Advisory Committee). 2010. Report of the Dietary Guidelines Advisory Committee on the Dietary Guidelines for Americans, 2010, to the Secretary of Agriculture and the Secretary of Health and Human Services. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Agricultural Research Service, Washington, DC.

DGAC. 2015. Scientific Report of the 2015 Dietary Guidelines Advisory Committee: Advisory Report to the Secretary of Health and Human Services and the Secretary of Agriculture. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Agricultural Research Service, Washington, DC.

DGAC. 2020. Scientific Report of the 2020 Dietary Guidelines Advisory Committee: Advisory Report to the Secretary of Agriculture and the Secretary of Health and Human Services. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Agricultural Research Service, Washington, DC.

Du, X. Y., L. Wen, Y. Y. Hu, S. Q. Deng, L. C. Xie, G. B. Jiang, G. L. Yang, and Y. M. Niu. 2021. Association between the Aldehyde Dehydrogenase-2 rs671 G>A polymorphism and head and neck cancer susceptibility: A meta-analysis in east Asians. Alcoholism, Clinical and Experimental Research 45(2):307–317.

Fedirko, V., M. Jenab, S. Rinaldi, C. Biessy, N. E. Allen, L. Dossus, N. C. Onland-Moret, M. Schutze, A. Tjonneland, L. Hansen, K. Overvad, F. Clavel-Chapelon, N. Chabbert-Buffet, R. Kaaks, A. Lukanova, M. M. Bergmann, H. Boeing, A. Trichopoulou, E. Oustoglou, A. Barbitsioti, C. Saieva, G. Tagliabue, R. Galasso, R. Tumino, C. Sacerdote, P. H. Peeters, H. B. Bueno-de-Mesquita, E. Weiderpass, I. T. Gram, S. Sanchez, E. J. Duell, E. Molina-Montes, L. Arriola, M. D. Chirlaque, E. Ardanaz, J. Manjer, E. Lundin, A. Idahl, K. T. Khaw, D. Romaguera-Bosch, P. A. Wark, T. Norat, and I. Romieu. 2013. Alcohol drinking and endometrial cancer risk in the European prospective investigation into cancer and nutrition (EPIC) study. Annals of Epidemiology 23(2):93–98.

Ferraguti, G., S. Terracina, C. Petrella, A. Greco, A. Minni, M. Lucarelli, E. Agostinelli, M. Ralli, M. de Vincentiis, G. Raponi, A. Polimeni, M. Ceccanti, B. Caronti, M. G. Di Certo, C. Barbato, A. Mattia, L. Tarani, and M. Fiore. 2022. Alcohol and head and neck cancer: Updates on the role of oxidative stress, genetic, epigenetics, oral microbiota, antioxidants, and alkylating agents. Antioxidants 11(1).

Gapstur, S. M., W. R. Diver, M. L. McCullough, L. R. Teras, M. J. Thun, and A. V. Patel. 2012. Alcohol intake and the incidence of non-Hodgkin lymphoid neoplasms in the cancer prevention study II nutrition cohort. American Journal of Epidemiology 176(1):60–69.

Gapstur, S. M., E. V. Bandera, D. H. Jernigan, N. K. LoConte, B. G. Southwell, V. Vasiliou, A. M. Brewster, T. S. Naimi, C. L. Scherr, and K. D. Shield. 2022. Alcohol and cancer: Existing knowledge and evidence gaps across the cancer continuum. Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers & Prevention 31(1):5–10.

Grille, V. J., S. Campbell, J. F. Gibbs, and T. L. Bauer. 2021. Esophageal cancer: The rise of adenocarcinoma over squamous cell carcinoma in the Asian belt. Journal of Gastrointestinal Oncology 12(Suppl 2):S339–S349.

Guidolin, V., E. S. Carlson, A. Carra, P. W. Villalta, L. A. Maertens, S. S. Hecht, and S. Balbo. 2021. Identification of new markers of alcohol-derived DNA damage in humans. Biomolecules 11(3).

Hashibe, M., J. Hunt, M. Wei, S. Buys, L. Gren, and Y. C. Lee. 2013. Tobacco, alcohol, body mass index, physical activity, and the risk of head and neck cancer in the prostate, lung, colorectal, and ovarian (PLCO) cohort. Head Neck 35(7):914–922.

Heath, A. K., D. C. Muller, P. A. van den Brandt, N. Papadimitriou, E. Critselis, M. Gunter, P. Vineis, E. Weiderpass, G. Fagherazzi, H. Boeing, P. Ferrari, A. Olsen, A. Tjonneland, P. Arveux, M. C. Boutron-Ruault, F. R. Mancini, T. Kuhn, R. Turzanski-Fortner, M. B. Schulze, A. Karakatsani, P. Thriskos, A. Trichopoulou, G. Masala, P. Contiero, F. Ricceri, S. Panico, B. Bueno-de-Mesquita, M. F. Bakker, C. H. van Gils, K. S. Olsen, G. Skeie, C.

Lasheras, A. Agudo, M. Rodriguez-Barranco, M. J. Sanchez, P. Amiano, M. D. Chirlaque, A. Barricarte, I. Drake, U. Ericson, I. Johansson, A. Winkvist, T. Key, H. Freisling, M. His, I. Huybrechts, S. Christakoudi, M. Ellingjord-Dale, E. Riboli, K. K. Tsilidis, and I. Tzoulaki. 2020. Nutrient-wide association study of 92 foods and nutrients and breast cancer risk. Breast Cancer Research 22(1):5.

Hippisley-Cox, J., and C. Coupland. 2015. Development and validation of risk prediction algorithms to estimate future risk of common cancers in men and women: Prospective cohort study. BMJ Open 5(3):e007825.

Hoes, L., R. Dok, K. J. Verstrepen, and S. Nuyts. 2021. Ethanol-induced cell damage can result in the development of oral tumors. Cancers (Basel) 13(15).

IARC (International Agency for Research on Cancer). 1988. IARC monographs on the evaluation of the carcinogenic risks to humans. https://publications.iarc.fr/62 (accessed November 15, 2024)

IARC. 2010. IARC Monographs on the Evaluation of Carcinogenic Risks to Humans. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21735939 (accessed November 15, 2024).

IARC. 2012. Personal habits and indoor combustions. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK304391/ (accessed November 15, 2024).

Im, P. K., I. Y. Millwood, C. Kartsonaki, Y. Chen, Y. Guo, H. Du, Z. Bian, J. Lan, S. Feng, C. Yu, J. Lv, R. G. Walters, L. Li, L. Yang, Z. Chen, and G. China Kadoorie Biobank Collaborative. 2021. Alcohol drinking and risks of total and site-specific cancers in China: A 10-year prospective study of 0.5 million adults. International Journal of Cancer 149(3):522–534.

Im, P. K., N. Wright, L. Yang, K. H. Chan, Y. Chen, Y. Guo, H. Du, X. Yang, D. Avery, S. Wang, C. Yu, J. Lv, R. Clarke, J. Chen, R. Collins, R. G. Walters, R. Peto, L. Li, Z. Chen, I. Y. Millwood, and G. China Kadoorie Biobank Collaborative. 2023. Alcohol consumption and risks of more than 200 diseases in Chinese men. Nature Medicine 29(6): 1476–1486.

Je, Y., I. De Vivo, and E. Giovannucci. 2014. Long-term alcohol intake and risk of endometrial cancer in the nurses’ health study, 1980–2010. British Journal of Cancer 111(1): 186–194.

Jin, E. H., K. Han, C. M. Shin, D. H. Lee, S. J. Kang, J. H. Lim, and Y. J. Choi. 2023. Sex and tumor-site differences in the association of alcohol intake with the risk of early-onset colorectal cancer. Journal of Clinical Oncology 41(22):3816–3825.

Johnson, C. H., J. P. Golla, E. Dioletis, S. Singh, M. Ishii, G. Charkoftaki, D. C. Thompson, and V. Vasiliou. 2021. Molecular mechanisms of alcohol-induced colorectal carcinogenesis. Cancers (Basel) 13(17).

Joseph, P. V., Y. Zhou, B. Brooks, C. McDuffie, K. Agarwal, and A. M. Chao. 2022. Relationships among alcohol drinking patterns, macronutrient composition, and caloric intake: National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2017–2018. Alcohol 57(5): 559–565.

Kawaii, M., Y. Minami, M. Kakizaki, Y. Kakugawa, Y. Nishino, A. Fukao, I. Tsuji, and N. Ohuchi. 2011. Alcohol consumption and breast cancer risk in Japanese women: The Miyagi cohort study. Breast Cancer Research and Treatment 128(1):817–825.

Key, T. J., A. Balkwill, K. E. Bradbury, G. K. Reeves, A. S. Kuan, R. F. Simpson, J. Green, and V. Beral. 2019. Foods, macronutrients and breast cancer risk in postmenopausal women: A large UK cohort. International Journal of Epidemiology 48(2):489–500.

Klatsky, A. L., Y. Li, H. N. Tran, D. Baer, N. Udaltsova, M. A. Armstrong, and G. D. Friedman. 2015. Alcohol intake, beverage choice, and cancer: A cohort study in a large Kaiser Permanente population. The Permanente Journal 19(2):28.

Kukreti, S., T. Yu, P. W. Chiu, and C. Strong. 2022. Clustering of modifiable behavioral risk factors and their association with all-cause mortality in Taiwan’s adult population: A latent class analysis. International Journal of Behavioral Medicine 29(5):565–574.

Lewis, S. J., and G. D. Smith. 2005. Alcohol, ALDH2, and esophageal cancer: A meta-analysis which illustrates the potentials and limitations of a mendelian randomization approach. Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers & Prevention 14(8):1967–1971.

Li, C. I., R. T. Chlebowski, M. Freiberg, K. C. Johnson, L. Kuller, D. Lane, L. Lessin, M. J. O’Sullivan, J. Wactawski-Wende, S. Yasmeen, and R. Prentice. 2010. Alcohol consumption and risk of postmenopausal breast cancer by subtype: The Women’s Health Initiative observational study. Journal of the National Cancer Institute 102(18):1422–1431.

Mayer-Davis, E., H. Leidy, R. Mattes, T. Naimi, R. Novotny, B. Schneeman, B. J. Kingshipp, M. Spill, N. C. Cole, G. Butera, N. Terry, and J. Obbagy. 2020. In Alcohol consumption and all-cause mortality: A systematic review, USDA Nutrition Evidence Systematic Reviews, Alexandria, VA.

Michaud, D. S., A. Vrieling, L. Jiao, J. B. Mendelsohn, E. Steplowski, S. M. Lynch, J. Wactawski-Wende, A. A. Arslan, H. Bas Bueno-de-Mesquita, C. S. Fuchs, M. Gross, K. Helzlsouer, E. J. Jacobs, A. Lacroix, G. Petersen, W. Zheng, N. Allen, L. Ammundadottir, M. M. Bergmann, P. Boffetta, J. E. Buring, F. Canzian, S. J. Chanock, F. Clavel-Chapelon, S. Clipp, M. S. Freiberg, J. Michael Gaziano, E. L. Giovannucci, S. Hankinson, P. Hartge, R. N. Hoover, F. Allan Hubbell, D. J. Hunter, A. Hutchinson, K. Jacobs, C. Kooperberg, P. Kraft, J. Manjer, C. Navarro, P. H. Peeters, X. O. Shu, V. Stevens, G. Thomas, A. Tjonneland, G. S. Tobias, D. Trichopoulos, R. Tumino, P. Vineis, J. Virtamo, R. Wallace, B. M. Wolpin, K. Yu, A. Zeleniuch-Jacquotte, and R. Z. Stolzenberg-Solomon. 2010. Alcohol intake and pancreatic cancer: A pooled analysis from the pancreatic cancer cohort consortium (PanScan). Cancer Causes Control 21(8):1213–1225.

Mizumoto, A., S. Ohashi, K. Hirohashi, Y. Amanuma, T. Matsuda, and M. Muto. 2017. Molecular mechanisms of acetaldehyde-mediated carcinogenesis in squamous epithelium. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 18(9).

Murphy, N., H. A. Ward, M. Jenab, J. A. Rothwell, M. C. Boutron-Ruault, F. Carbonnel, M. Kvaskoff, R. Kaaks, T. Kuhn, H. Boeing, K. Aleksandrova, E. Weiderpass, G. Skeie, K. B. Borch, A. Tjonneland, C. Kyro, K. Overvad, C. C. Dahm, P. Jakszyn, M. J. Sanchez, L. Gil, J. M. Huerta, A. Barricarte, J. R. Quiros, K. T. Khaw, N. Wareham, K. E. Bradbury, A. Trichopoulou, C. La Vecchia, A. Karakatsani, D. Palli, S. Grioni, R. Tumino, F. Fasanelli, S. Panico, B. Bueno-de-Mesquita, P. H. Peeters, B. Gylling, R. Myte, K. Jirstrom, J. Berntsson, X. Xue, E. Riboli, A. J. Cross, and M. J. Gunter. 2019. Heterogeneity of colorectal cancer risk factors by anatomical subsite in 10 European countries: A multinational cohort study. Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology 17(7):1323–1331 e1326.

Naudin, S., K. Li, T. Jaouen, N. Assi, C. Kyro, A. Tjonneland, K. Overvad, M. C. Boutron-Ruault, V. Rebours, A. L. Vedie, H. Boeing, R. Kaaks, V. Katzke, C. Bamia, A. Naska, A. Trichopoulou, F. Berrino, G. Tagliabue, D. Palli, S. Panico, R. Tumino, C. Sacerdote, P. H. Peeters, H. B. A. Bueno-de-Mesquita, E. Weiderpass, I. T. Gram, G. Skeie, M. D. Chirlaque, M. Rodriguez-Barranco, A. Barricarte, J. R. Quiros, M. Dorronsoro, I. Johansson, M. Sund, H. Sternby, K. E. Bradbury, N. Wareham, E. Riboli, M. Gunter, P. Brennan, E. J. Duell, and P. Ferrari. 2018. Lifetime and baseline alcohol intakes and risk of pancreatic cancer in the European prospective investigation into cancer and nutrition study. International Journal of Cancer 143(4):801–812.

Nieminen, M. T., and M. Salaspuro. 2018. Local acetaldehyde-an essential role in alcohol-related upper gastrointestinal tract carcinogenesis. Cancers (Basel) 10(1).

Okaru, A. O., and D. W. Lachenmeier. 2021. Margin of exposure analyses and overall toxic effects of alcohol with special consideration of carcinogenicity. Nutrients 13(11).

Papa, N. P., R. J. MacInnis, H. Jayasekara, D. R. English, D. Bolton, I. D. Davis, N. Lawrentschuk, J. L. Millar, J. Pedersen, G. Severi, M. C. Southey, J. L. Hopper, and G. G. Giles. 2017. Total and beverage-specific alcohol intake and the risk of aggressive prostate cancer: A case-control study. Prostate Cancer and Prostatic Diseases 20(3):305–310.

Park, S. Y., L. N. Kolonel, U. Lim, K. K. White, B. E. Henderson, and L. R. Wilkens. 2014. Alcohol consumption and breast cancer risk among women from five ethnic groups with light to moderate intakes: The multiethnic cohort study. International Journal of Cancer 134(6):1504–1510.

Prabhu, A., K. O. Obi, and J. H. Rubenstein. 2014. The synergistic effects of alcohol and tobacco consumption on the risk of esophageal squamous cell carcinoma: A meta-analysis. American Journal of Gastroenterology 109(6):822–827.

Radoï, L., S. Paget-Bailly, D. Cyr, A. Papadopoulos, F. Guida, A. Schmaus, S. Cenee, G. Menvielle, M. Carton, and B. Lapôtre-Ledoux. 2013. Tobacco smoking, alcohol drinking and risk of oral cavity cancer by subsite: Results of a French population-based case–control study, the ICARE study. European Journal of Cancer Prevention 22(3):268–276.

Rainey, L., M. Eriksson, T. Trinh, K. Czene, M. J. Broeders, D. van Der Waal, and P. Hall. 2020. The impact of alcohol consumption and physical activity on breast cancer: The role of breast cancer risk. International Journal of Cancer 147(4):931–939.

Richmond, R. C., and G. Davey Smith. 2022. Mendelian randomization: Concepts and scope. Cold Spring Harbor Perspectives in Medicine 12(1).

Romieu, I., C. Scoccianti, V. Chajes, J. de Batlle, C. Biessy, L. Dossus, L. Baglietto, F. Clavel-Chapelon, K. Overvad, A. Olsen, A. Tjonneland, R. Kaaks, A. Lukanova, H. Boeing, A. Trichopoulou, P. Lagiou, D. Trichopoulos, D. Palli, S. Sieri, R. Tumino, P. Vineis, S. Panico, H. B. Bueno-de-Mesquita, C. H. van Gils, P. H. Peeters, E. Lund, G. Skeie, E. Weiderpass, J. R. Quiros Garcia, M. D. Chirlaque, E. Ardanaz, M. J. Sanchez, E. J. Duell, P. Amiano, S. Borgquist, E. Wirfalt, G. Hallmans, I. Johansson, L. M. Nilsson, K. T. Khaw, N. Wareham, T. J. Key, R. C. Travis, N. Murphy, P. A. Wark, P. Ferrari, and E. Riboli. 2015. Alcohol intake and breast cancer in the European prospective investigation into cancer and nutrition. International Journal of Cancer 137(8):1921–1930.

Rumgay, H., N. Murphy, P. Ferrari, and I. Soerjomataram. 2021. Alcohol and cancer: Epidemiology and biological mechanisms. Nutrients 13(9).

Sayon-Orea, C., M. A. Martínez-González, and M. Bes-Rastrollo. 2011. Alcohol consumption and body weight: A systematic review. Nutrition Reviews 69(8):419–431.

Schuit, A. J., A. J. van Loon, M. Tijhuis, and M. Ocke. 2002. Clustering of lifestyle risk factors in a general adult population. Preventive Medicine 35(3):219–224.

Sen, A., K. K. Tsilidis, N. E. Allen, S. Rinaldi, P. N. Appleby, M. Almquist, J. A. Schmidt, C. C. Dahm, K. Overvad, A. Tjonneland, A. L. Rostgaard-Hansen, F. Clavel-Chapelon, L. Baglietto, M. C. Boutron-Ruault, T. Kuhn, V. A. Katze, H. Boeing, A. Trichopoulou, C. Tsironis, P. Lagiou, D. Palli, V. Pala, S. Panico, R. Tumino, P. Vineis, H. A. Bueno-de-Mesquita, P. H. Peeters, A. Hjartaker, E. Lund, E. Weiderpass, J. R. Quiros, A. Agudo, M. J. Sanchez, L. Arriola, D. Gavrila, A. B. Gurrea, A. Tosovic, J. Hennings, M. Sandstrom, I. Romieu, P. Ferrari, R. Zamora-Ros, K. T. Khaw, N. J. Wareham, E. Riboli, M. Gunter, and S. Franceschi. 2015. Baseline and lifetime alcohol consumption and risk of differentiated thyroid carcinoma in the EPIC study. British Journal of Cancer 113(5):840–847.

Shield, K. D., I. Soerjomataram, and J. Rehm. 2016. Alcohol use and breast cancer: A critical review. Alcoholism, Clinical and Experimental Research 40(6):1166–1181.

Silva, P., N. Latruffe, and G. Gaetano. 2020. Wine consumption and oral cavity cancer: Friend or foe, two faces of Janus. Molecules 25(11).

Steevens, J., L. J. Schouten, R. A. Goldbohm, and P. A. Van den Brandt. 2010. Alcohol consumption, cigarette smoking and risk of subtypes of oesophageal and gastric cancer: A prospective cohort study. Gut 59(01):39–48.

Stornetta, A., V. Guidolin, and S. Balbo. 2018. Alcohol-derived acetaldehyde exposure in the oral cavity. Cancers (Basel) 10(1).

Suzuki, R., M. Iwasaki, M. Inoue, S. Sasazuki, N. Sawada, T. Yamaji, T. Shimazu, and S. Tsugane. 2010. Alcohol consumption-associated breast cancer incidence and potential effect modifiers: The Japan public health center-based prospective study. International Journal of Cancer 127(3):685–695.

Tin Tin, S., K. Smith-Byrne, P. Ferrari, S. Rinaldi, M. L. McCullough, L. R. Teras, J. Manjer, G. Giles, L. Le Marchand, C. A. Haiman, L. R. Wilkens, Y. Chen, S. Hankinson, S. Tworoger, A. H. Eliassen, W. C. Willett, R. G. Ziegler, B. J. Fuhrman, S. Sieri, C. Agnoli, J. Cauley, U. Menon, E. O. Fourkala, T. E. Rohan, R. Kaaks, G. K. Reeves, and T. J. Key. 2024. Alcohol intake and endogenous sex hormones in women: Meta-analysis of cohort studies and mendelian randomization. Cancer 130(19):3375–3386.

Toh, Y., E. Oki, K. Ohgaki, Y. Sakamoto, S. Ito, A. Egashira, H. Saeki, Y. Kakeji, M. Morita, Y. Sakaguchi, T. Okamura, and Y. Maehara. 2010. Alcohol drinking, cigarette smoking, and the development of squamous cell carcinoma of the esophagus: Molecular mechanisms of carcinogenesis. International Journal of Clinical Oncology 15(2):135–144.

USDA (U.S. Department of Agriculture) and HHS (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services). Dietary Guidelines for Americans, 2010. 7th Edition. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office, December 2010.

USDA and HHS. 2015–2020 Dietary Guidelines for Americans. 8th Edition. Washington, DC. December 2015. Available at http://health.gov/dietaryguidelines/2015/guidelines/ (accessed September 20, 2024).

USDA and HHS. Dietary Guidelines for Americans. 9th Edition. Washington, DC. December 2020. https://www.dietaryguidelines.gov/sites/default/files/2021-03/Dietary_Guidelines_for_Americans-2020-2025.pdf (accessed September 20, 2024).

WCRF (World Cancer Research Fund International). 2018. Alcohol drinks and the risk of cancer. https://www.wcrf.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/02/Alcoholic-Drinks.pdf (accessed September 23, 2024).

White, A. J., L. A. DeRoo, C. R. Weinberg, and D. P. Sandler. 2017. Lifetime alcohol intake, binge drinking behaviors, and breast cancer risk. American Journal of Epidemiology 186(5):541–549.

Wright, R. M., J. L. McManaman, and J. E. Repine. 1999. Alcohol-induced breast cancer: A proposed mechanism. Free Radical Biology & Medicine 26(3–4):348–354.

Yokoyama, A., E. Tsutsumi, H. Imazeki, Y. Suwa, C. Nakamura, T. Mizukami, and T. Yokoyama. 2008. Salivary acetaldehyde concentration according to alcoholic beverage consumed and aldehyde dehydrogenase-2 genotype. Alcoholism, Clinical and Experimental Research 32(9):1607–1614.

Yoo, J. E., D. W. Shin, K. Han, D. Kim, S. M. Jeong, H. Y. Koo, S. J. Yu, J. Park, and K. S. Choi. 2021. Association of the frequency and quantity of alcohol consumption with gastrointestinal cancer. JAMA Network Open 4(8):e2120382.

Zhang, M., and C. Holman. 2011. Low-to-moderate alcohol intake and breast cancer risk in Chinese women. British Journal of Cancer 105(7):1089–1095.