Charting a Path Toward New Treatments for Lyme Infection-Associated Chronic Illnesses (2025)

Chapter: 3 Building on Research from Other Infection-Associated Chronic Illnesses

3

Building on Research from Other Infection-Associated Chronic Illnesses

Lyme infection-associated chronic illnesses (IACI) are among the many chronic illnesses that are potentially triggered by an infectious agent. Also called “post-acute infectious syndromes,” such other conditions with similar subjective symptoms of unclear etiology have been described following viral, bacterial, and parasitic infections (Choutka et al., 2022).1 These may be related to a specific pathogen, such as Long COVID and post-polio syndrome, or may not have a clear connection to specific pathogens, such as with as myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome (ME/CFS). However, while several potential disease mechanisms have been hypothesized, including the possibility of overlap or interactions between more than one process, the pathogenesis of Lyme IACI and other IACI remains unknown (Arron et al. 2024; Bai and Richardson 2023; Choutka et al., 2022; Davis et al. 2023; Komaroff and Lipkin, 2023).

The potential link to infectious agents and parallels in symptoms contribute to the hypothesis that there may be common mechanisms among Lyme IACI and other IACI that lead to these chronic symptoms (NASEM, 2024b). Thus, there may be treatment approaches or therapeutic agents that act on common causative pathways to alleviate symptoms across more than one of these similar diseases. For example, dysautonomia symptoms have been reported in Lyme IACI, Long COVID, and ME/CFS, which would

___________________

1 Collectively these are referred to as “infection-associated chronic illnesses” (IACI) in this report while acknowledging that no single infectious agent has been linked to ME/CFS and that whether there is a definitive infectious origin for the condition as a whole remains debated and uncertain.

suggest therapeutic agents for autonomic nervous system dysfunction as an avenue for exploration (Adler et al., 2024). Existing knowledge and ongoing research from ME/CFS have already helped shape treatment strategies to ameliorate Long COVID symptoms (Bonilla et al., 2023; Petracek et al., 2023). Similar opportunities exist for knowledge sharing to inform Lyme IACI research and address the unmet need for new treatments.

Stigmatization and dismissal or minimization of their symptoms in social spheres and in seeking health care are common experiences shared by those living with chronic symptoms from IACI, even as objectively measurable pathology affirms the severity of their symptoms (Ali et al., 2014; IOM, 2015; NASEM, 2024a). People living with IACI have shared how these debilitating symptoms have reverberated throughout their daily lives and the profound impact on their social, economic, mental, and physical well-being. The debilitating impact that these symptoms have on people’s health and quality of life must be matched by an equal urgency to provide high-quality scientific evidence for clinical decision-making.

In this chapter, the committee explores research conducted concerning IACI other than Lyme IACI, with a focus on how findings from such research may be drawn upon to advance Lyme IACI treatment. A full understanding of disease etiology and mechanisms remain elusive in IACI, though these likely involve a complex combination of pathogen, host, and environmental factors (Peluso et al., 2024). The generally insufficient understanding of the causes of IACI impedes evaluation and prioritization of candidate treatments that target disease etiology and pathogenesis, which may be further complicated by the possibility that multiple causes or risk factors may be responsible for developing IACI. In the absence of robust data to inform mechanism-based disease targets and treatments, the committee examined findings on treatments aimed at alleviating symptoms and the associated evidence base to any available knowledge on disease mechanisms.

Surveying Potential Treatments with Focus on ME/CFS and Long COVID

Of the many chronic illnesses potentially associated with an infectious trigger, ME/CFS and Long COVID have emerged as two with the most robust evidence bases—one built over decades of research, the other driven by the sudden and immense disease burden stemming from the global pandemic. Based on the significant overlap in symptoms among Lyme IACI, Long COVID, and ME/CFS (Table 3-1) as well as potential insights from the research infrastructure that have been established around ME/CFS and Long COVID, the committee centered this evidence review around these two conditions.

TABLE 3-1 Symptoms Commonly Reported for IACI

| Symptoms | Lyme IACI | Long COVID | ME/CFS |

|---|---|---|---|

| Neurocognitive function (memory loss, brain fog) | x | x | x |

| Fatigue | x | x | x |

| Musculoskeletal pain (myalgia, arthralgia) | x | x | x |

| Sleep impairment (difficulty with sleep, unrefreshing sleep) | x | x | x |

| Mental health symptoms (depression, anxiety) | x | x | x |

| Headache | x | x | x |

| Dysautonomia symptoms | x | x | x |

| Gastrointestinal symptoms | x | x | x |

| Paresthesia | x | x | |

| Stiff neck | x | ||

| Tremors/twitching | x | ||

| Change in taste/smell | x | ||

| Rash and hair loss | x | ||

| Post-exertional malaise1 | x | x | |

| Food/chemical sensitivities | x | ||

| Lymphadenopathy | x | ||

| Increased susceptibility to viruses | x |

1 Post-exertional malaise has not been evaluated separately from measures of fatigue in studies on Lyme IACI.

NOTE: IACI = infection-associated chronic illnesses; ME/CFS = myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome.

The committee surveyed systematic reviews and meta-analyses published since 2020 that described randomized trials evaluating pharmacological and nonpharmacological treatments for the two conditions. While the committee’s search focused on ME/CFS and Long COVID, the initial literature search was broadly conducted to incorporate reviews on other IACI, if available. A descriptive summary of the results of randomized trials that have been assessed in review articles is offered in this section. There were three reviews that evaluated studies assessing treatments for other IACI based on mechanistic pathways: one summarized studies on the effects of plasmapheresis on amyloid fibrin(ogen) particles in people with Long

COVID (Fox et al., 2023), the second examined studies that evaluated the efficacy of nutraceutical interventions to target mitochondrial dysfunction in individuals living with ME/CFS (Maksoud et al., 2021), and the third summarized ongoing clinical trials that target proposed disease mechanisms in Long COVID (Chee et al., 2023). The rest of the systematic reviews evaluated studies of treatments to alleviate persistent symptoms without specifically targeting a particular disease mechanism or etiology. There was also a notable lack of studies focused on the pediatric population. As more knowledge is generated on disease mechanisms from other IACI and on promising therapeutic interventions for children and adolescents, it will be important to examine the possible applicability to Lyme IACI research for this subpopulation as well.

Conclusion 3-1: There is an insufficient understanding of the underlying mechanisms that cause Lyme IACI and of how Lyme IACI is similar to and distinct from other IACI.

CLINICAL EVIDENCE ON SYMPTOM-BASED APPROACHES TO TREATMENTS FOR IACI

There is overlap in many of the symptoms ascribed to Lyme IACI, ME/CFS, Long COVID, and other chronic conditions suspected of having an infectious trigger. Table 3-1 provides an overview of the most commonly noted symptoms in the literature for Lyme IACI, Long COVID, and ME/CFS, drawn from reviews on similarities and differences among the conditions (Bai and Richardson, 2023; Choutka et al., 2022; Komaroff and Lipkin, 2023). It should be noted, however, that these lists of symptoms are not intended to provide a case definition or diagnostic criteria for the associated illnesses or conditions. Heterogeneity in symptoms among people living with IACI is a central feature of these conditions. While there can be a subset of core or characteristic symptoms, or subsets of symptom clusters associated with each condition, individual experiences with the disease may differ from one person to the next. Research on different IACIs, such as Long COVID, has generally not prioritized patient-reported symptoms or lived experience into the study’s goals, approach, or outcome measures as standard practice (Zeraatkar et al., 2024).

In Lyme IACI, an analysis of self-reported information in a patient-led registry found that the three most commonly reported symptoms were neurologic—cognitive impairment or neuropathy (84 percent), fatigue (64 percent), and musculoskeletal pain (57 percent) (Johnson et al., 2018). These symptoms were reported by many individuals as severe, with symptoms related to pain, mental health, physical health, and general poor

health affecting quality of life on a majority of days within a 30-day period (Johnson et al., 2014). Additional observational studies have also found that fatigue, pain, and cognitive impairment were among the most frequent symptoms exhibited by individuals living with Lyme IACI (Aucott et al., 2013; Rebman et al., 2017). These three symptoms are also extremely common in both adults and children living with Long COVID and ME/CFS (Komaroff and Lipkin, 2023; Rao et al., 2024; Rowe et al., 2017). Given these findings, the committee organized their assessment of current evidence for the effectiveness of treatments of other IACI around the core symptoms of fatigue, pain, and cognitive dysfunction, while remaining inclusive of the literature that addresses other common symptoms as well as approaches that may mitigate more than one symptom.

This section summarizes current evidence from randomized trials on the treatment of other IACI, with a focus on ME/CFS and Long COVID. The summary is organized by the major symptoms described in Lyme IACI. The evidence presented in this section is not intended to be a comprehensive review of treatments for other IACI. The committee prioritized scientific findings that are supported by a compilation of evidence and systematically reviewed over new claims whose results have not yet been reviewed or replicated. The literature search was thus limited to meta-analyses and systematic reviews published since 2020, and the outcomes of individual randomized trials within those reviews are summarized below. An important limitation of relying on published reviews to identify current evidence is the potential exclusion of well-designed, high-quality, or promising late-breaker studies that were not captured in review articles due to temporal or scope parameters. Another key limitation in this method is the reliance on reporting effectiveness of interventions based on the outcome cutoff defined in individual studies. However, this approach is intended to provide a broad overview of the evidence on treatments for other IACI and enable the committee to examine evidence that has been replicated in multiple studies, when available. While studies differed in the use of outcome measurements and analyses to determine effectiveness, on balance, none of the interventions described in this section have consistent, compelling evidence suggesting effectiveness.

Fatigue

While fatigue may be perceived by the public as a general, transient experience, the fatigue experienced by people with IACI is often severe and intractable and may or may not be worsened by physical activity. Fatigue may be caused by inadequate signaling from the central nervous system to the rest of the body to initiate or sustain a task (i.e., central fatigue), by inadequate signaling or responses from muscle receptors (i.e., peripheral

fatigue), or by a combination of the two. Yet the specific pathogenic pathways that lead to these alterations in neuromuscular signaling and responses remain poorly understood (Staud, 2012). This complexity suggests that effective treatment of fatigue will likely require a better understanding of its pathogenesis in different individuals and circumstances in which pharmacological or nonpharmacological strategies that exert change on multiple pathways may be more likely to succeed in symptom management.

Evidence in Adults

Both medications and nonpharmacologic interventions have been evaluated using randomized trials for their effects on fatigue in adults. Overall, for ME/CFS there were more reports of beneficial effects among studies on nonpharmacologic interventions than among studies on medications or complementary and alternative medicine (Kim et al., 2020). Similarly, a systematic review of randomized trials for Long COVID (inclusive of publications up until December 2023) did not identify any pharmaceutical interventions that improved fatigue in this population (Zeraatkar et al., 2024). Single studies of individuals with ME/CFS have suggested potential benefit for methylphenidate (a central nervous system stimulant) or coenzyme Q10 with nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide in its reduced form (NADH, a hypothesized mitochondrial modulator) (hypothesized mitochondrial modulator) to alleviate fatigue (Blockmans et al., 2006; Castro-Marrero et al., 2015); although these studies were randomized and controlled, both were small trials with fewer than 50 participants in their treatment arms. Evidence from medium-to-larger trials for ME/CFS on the potential effect on fatigue of hydro- or fludrocortisone at various dose ranges remain conflicted, with benefit reported in one randomized crossover study including 32 patients (Cleare et al., 1999), but not in four other randomized trials (Blockmans et al., 2003; McKenzie et al., 1998; Peterson et al., 1998; Rowe et al., 2001). These findings alone are not sufficient to justify immediate adoption of these interventions in randomized trials for the treatment of fatigue in Lyme IACI. Further research into the abovementioned products for the treatment of fatigue in other IACI, including Lyme IACI, must be supported by reasonable biological plausibility and any additional preclinical or clinical data that supports the treatments’ effects. Many trials described in the available literature have small sample sizes (<100), the results have not been replicated, and understanding of the therapeutic mechanisms—which would bolster confidence in any observed effects—may be lacking.

Cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) and graded exercise therapy have been studied as nonpharmaceutical interventions to improve fatigue for ME/CFS and, more recently, for Long COVID. However, several important caveats must be kept in mind when considering the trial outcomes related

to these two approaches. CBT is an established psychological intervention with roots in treating mental health conditions that has also been found to be effective in managing aspects of many chronic diseases (Halford and Brown, 2009; Taylor, 2006). CBT can alleviate mental health–related comorbidities (e.g., depression, anxiety) and help develop coping strategies for individuals living with chronic illnesses. Whether CBT may improve other aspects of IACI through additional mechanistic pathways remains to be determined.

Graded exercise therapy was initially explored as an intervention for ME/CFS based on the hypothesis that deconditioning is a main cause of post-exertional malaise in ME/CFS. However, exercise therapy may in fact exacerbate symptoms of ME/CFS for some individuals and can lead individuals to adopt coping behaviors to be able to complete the exercise regimen, which does not reflect symptom improvement. Furthermore, there are criticisms surrounding analyses and outcome reporting of a major trial involving these interventions (Geraghty, 2017; White et al., 2017). Within this context, clinical trial design and outcome interpretations need to consider whether the trial endpoints reflect a temporary remission, masking, or actual sustained recovery of symptoms such that accurate conclusions can be drawn and reported. As discussed below, there is currently insufficient evidence to consider CBT and graded exercise therapy as preferred therapeutic options for ME/CFS or Long COVID (Sanal-Hayes et al., 2023; Wilshire et al., 2018).

A high-level overview of trials involving CBT found mixed results in trials in individuals with ME/CFS and Long COVID. One complication in the interpretation of trial results or of an aggregated analysis is the variation in the CBT protocols used across different studies. In one systematic review, improvement in fatigue was reported in six out of 10 randomized trials of CBT that enrolled at least 45 participants with ME/CFS (or at least 23 participants for randomized crossover trials) (Deale et al., 1997; Janse et al., 2018; Kim et al., 2020; Prins et al., 2001; Sharpe et al., 1996; White et al., 2011; Wiborg et al., 2015), and other trials reported similar potential benefits in reduction of fatigue in ME/CFS (O’Dowd et al., 2006; Stubhaug et al., 2008). Similarly, CBT may be beneficial for managing fatigue associated with Long COVID, but these findings were based on low-certainty evidence and require additional study (Kuut et al., 2023; Zeraatkar et al., 2024). Two randomized trials reported that less intense self-guided instruction based on CBT for people with ME/CFS led to improvement in fatigue and physical function (Knoop et al., 2008), though the improvement in physical function was restricted to a subgroup of participants with physical disabilities at baseline in one of the studies (Tummers et al., 2012). While individuals with ME/CFS reported some improvement in fatigue in studies of CBT, this was not always associated with increased activity level and can be interpreted as an adaptation instead of improvement in the underlying

disease (Toogood et al., 2021). CBT has also been evaluated for other postinfectious fatigue, with positive outcomes reported in a study of Q fever fatigue syndrome compared with an oral medication placebo group, though comparison between groups receiving CBT and oral antibiotics was not performed (Keijmel et al., 2017).

Graded exercise therapy has in the past been suggested as a therapy that could address post-exertional malaise, a symptom that has been described for ME/CFS and Long COVID but has not been differentiated from general fatigue in Lyme IACI research. It is important to note that exercise regimens that address respiratory, cardiovascular, and musculoskeletal deconditioning as sources of physical fatigue are contraindicated for a subset of individuals with ME/CFS. Post-exertional malaise has been linked with distinct pathological changes in muscles, including mitochondrial dysfunction and abnormal lactic acid accumulation (Appelman et al., 2024), but such changes have yet to be evaluated in Lyme IACI. Overall, current evidence suggests that a patient-led, self-paced approach to physical activity is more likely to be beneficial than pre-set therapy regimens (Fowler-Davis, 2021). Graded exercise therapy was found to have some benefit in two studies of ME/CFS (Wearden et al., 1998; White et al., 2011), and self-managed graded exercise or other self-paced physical activity reported reduction in the severity of fatigue in ME/CFS (Clark et al., 2017; Marques et al., 2015). A meta-analysis of randomized trials studying graded exercise therapy for individuals with Long COVID found overall improvement in fatigue from structured physical activities, including aerobic, multimodal, breathing, and tai chi exercises. However, the majority of these studies were assessed to have high risk of bias, and additional rigorously designed studies are needed to confirm efficacy (Cheng et al., 2024). A critical context for these findings is the lack of a reliable method to distinguish individuals who may benefit with exercise therapy from others for whom it is detrimental.

Complementary and alternative medicine or health strategies have also been explored for the management of fatigue in ME/CFS and Long COVID. Acupuncture or therapeutic abdominal massages have been suggested to improve fatigue symptoms in people with ME/CFS and Long COVID (Huanan et al., 2017; Kim et al., 2015; Lam et al., 2024; Ng and Yiu, 2013). Isometric yoga, alone or in combination with pharmacotherapy, was reported to have some benefits for ME/CFS (Oka et al., 2014). Other complementary and alternative interventions that suggest potential benefit to an individual’s health are based on data considered to be low confidence and would require well-designed, adequately powered studies to determine whether there are meaningful benefits. These include a variety of Chinese herbal medicines used alone or co-administered with conventional pharmaceuticals; integrative medicine approaches, including muscle relaxation and meditation; nutrient supplements, such as probiotic microbes and

enzymes; aromatherapy; and traditional Chinese medicine (Chen et al., 2024; Hawkins et al., 2022; Pang et al., 2022; Rathi et al., 2021).

Evidence in Pediatrics

Of the literature described in the review papers the committee assessed, only two studies of ME/CFS measured outcomes in the pediatric population. These found improvement in fatigue and general physical scoring in children following CBT interventions (Kim et al., 2020; Nijhof et al., 2012; Stulemeijer et al., 2005).

Pain

Current research generally categorizes pain into three types based on its source and pathophysiology (Cao et al., 2024). Nociceptive pain stems from inflammation and tissue damage and is usually treatable with analgesics. Neuropathic pain results from nerve damage and responds poorly to analgesics. Nociplastic pain is a relatively new concept that describes pain not associated with detectable involvement of nociceptive or neuropathic pathways (i.e., pain in the absence of tissue or nerve damage). The etiology for nociplastic pain remains poorly understood, though enhanced pain and sensory processing in the central nervous system or altered pain modulation have been proposed as possibilities (Kaplan et al., 2024). While such overall categorization based on a mechanistic understanding of pain can be informative for the development and application of treatments, different types of pain may occur simultaneously in individual people.

Pain can decrease the quality of life, and chronic pain in particular is associated with serious comorbidities, including depression, anxiety, fatigue, and cognitive impairment (Cao et al., 2024; Fitzcharles et al., 2021). Pharmacological options for pain relief largely work on cellular targets for inflammation or various signaling receptors in the neurosensory pathway. In addition, nonpharmaceutical interventions such as cognitive behavioral therapy, exercise, acupuncture, and others have demonstrated effectiveness in general pain management.

Evidence in Adults

Clinical trials targeting pain in Long COVID and ME/CFS populations have been limited. Analgesics, including opiates and naloxone were found to have minimal effects in ME/CFS by a small study with 41 participants (Hermans et al., 2018). A randomized trial of 54 participants assessing psycho-spiritual mental health education in ME/CFS found that the intervention improved well-being, with a decrease in daily interference from pain. (El-Mokadem et al., 2023).

Chronic pain symptoms have been reported following other infections beyond COVID. For example, people recovering from chikungunya fever, a mosquito-transmitted viral disease characterized by severe debilitating joint pain, often experience ongoing musculoskeletal and neuropathic pain for months to years (WHO, 2025). A systematic review identified two small randomized trials that suggested some benefit from physical therapy or exercise in improving physical function and reducing pain in those individuals (de Oliveira et al., 2019; Neumann et al., 2021). A third randomized trial identified in the systematic review found transcranial direct current stimulation to significantly improve pain in this patient population, but it had no effect on physical function or the quality of life (Silva-Filho et al., 2018).

Post-polio syndrome is another disorder for which a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized, controlled trials of treatment was available. This review examined evidence on intravenous immunoglobulin therapy and concluded that it was unlikely to improve pain, fatigue, or muscle strength. However, these trials had small sample sizes, and further study would be needed to determine whether certain patient subgroups might respond to the therapy (Huang et al., 2015).

Evidence in Pediatrics

A review found that despite the prevalence and impact of pain, very few pediatric studies had measured it, and no studies were found on pain management in children. The treatments studied focused primarily on the overall management of ME/CFS for pediatric populations. As more research is conducted to identify effective therapeutic options for pain associated with ME/CFS and other IACI in adults, additional safety, efficacy, and dosing studies will need to be conducted in pediatric populations to determine if these treatments are also appropriate for children (Ascough et el., 2020).

Cognitive Dysfunction

People living with IACI have described “brain fog” that may include attention deficits (e.g., an inability to concentrate or maintain focus), mental fatigue (e.g., reduced task processing speed), language loss (e.g., difficulties finding words), and other impairments in memory, reasoning, and executive functions (IOM, 2015; NASEM 2024a; Touradji et al., 2019). While many reported symptoms have subjective qualities, there are established methods and tools to measure neurologic and cognitive function that can be used to connect patient-reported outcomes to objectively characterize neurocognitive decline. The causes of these types of cognitive symptoms remain elusive. Available data in Long COVID suggest two potential mechanisms that may occur alone or in combination: inflammation involving the central nervous

system and vascular dysfunction from SARS-CoV-2 infection (Spudich and Nath, 2022). Reductions in gray matter thickness and global brain size have also been noted in some individuals with Long COVID in comparisons of MRI scans before and after COVID-19 infection, suggesting damage to the central nervous system (Komaroff and Lipkin, 2023). Markers of neuroinflammation and other physiological changes in brain structure have similarly been measured for ME/CFS (Lee et al., 2024; Walitt et al., 2024). People living with IACI may simultaneously experience pain, depression, and anxiety, which are each known from other conditions to affect different aspects of cognition (James and Ferguson, 2020; Robinson et al., 2013), complicating efforts to dissect cause and effect.

Evidence in Adults

Pathogen persistence is a possible cause of ongoing inflammation or structural changes in IACI that may lead to cognitive impairment, and anti-infectives have been explored as treatment options. In a subset of individuals with ME/CFS who had elevated Epstein-Barr viral and human herpesvirus 6 titers, treatment with valganciclovir, an RNA polymerase inhibitor antiviral drug, was associated with minor improvement in cognitive symptoms when given for 6 months (Montoya et al., 2013). The Toll-like receptor 3 agonist polyl:polyC12U (also known as rintatolimod or Ampligen) has antiviral and immunomodulatory properties and yielded mild improvements to cognitive deficit in a small, randomized trial for ME/CFS (Strayer et al., 1994). It has been approved for use in severe cases of ME/CFS in Argentina but not in the United States and is being tested for efficacy in Long COVID with mixed read-outs from a recent phase II trial (AIM ImmunoTech, 2024).

Various other pharmaceutical treatments have been evaluated for their potential to improve cognition in Long COVID. Two medications with known neurological applications, donepezil chlorhydrate (a cholinesterase inhibitor approved for Alzheimer’s disease) and an investigational endocannabinoid treatment for neurodegenerative diseases, were not found to improve cognitive function (Pooladgar et al., 2023; Versace et al., 2023). The serotonergic antidepressant drug vortioxetine may have potential to improve depression and general health-related quality of life, but no effects on cognitive function were detected (McIntyre et al., 2024). Famotidine, a selective histamine 2 (H2) receptor antagonist, was reported to lead to some improvement in cognitive function (Momtazmanesh et al., 2023). While the evidence assessed above was all drawn from randomized, controlled trials, the sample sizes examined were small and the findings need to be confirmed by larger trials.

Nonpharmaceutical approaches have also been evaluated for improvement of cognitive functioning in Long COVID and have also yielded mixed results. A meditation program was shown to improve processing speed in a small cohort (Hausswirth et al., 2023), but breathing training and a mobile app guide to motivational and rehabilitation activities in a randomized controlled trial of 100 people with Long COVID were not found to affect cognitive function (Philip et al., 2022, Samper-Pardo et al., 2023). As described above, a meta-analysis of randomized, controlled trials evaluating exercise therapies suggested improvement in fatigue but did not find effects on cognitive impairment (Cheng et al., 2024). No improvement in executive function and processing speed was found after transcranial direct current stimulation (Oliver-Mas et al., 2023). Some improvement in cognitive function from hyperbaric oxygen was reported in a randomized trial of 73 participants; approximately 10 percent of participants in both the treatment and control arms experienced trauma resulting from pressure changes in the hyperbaric chamber where participants received the intervention or sham treatment (Zilberman-Itskovich et al., 2022).

Available findings from three small randomized trials of alternative medicine approaches to treat cognitive dysfunction are inconclusive, given the variety of supplements evaluated and the inconsistency in the effects on cognitive symptoms. A randomized trial with 31 participants with Long COVID found that a cannabidiol-rich hemp-derived product did not improve cognition compared with baseline (Young et al., 2024). A randomized trial of 100 participants evaluating an adaptogen mixture in people with Long COVID showed improvement in cognitive performance, anxiety, and depression in both the treatment and placebo groups compared with baseline, but no difference in the three symptoms between the treatment and placebo groups. This finding suggests the intervention was no different than a placebo in addressing cognition, anxiety, or depression (Karosanidze et al., 2022). A nutritional supplement consisting of a combination of ethylmethylhydroxypyridine succinate and meldonium, tested in a randomized trial of 30 participants with Long COVID, led to a small improvement in cognitive function compared with a placebo control (Tanashyan et al., 2023).

Evidence in Pediatrics

No randomized trials included in systematic reviews or meta-analyses on ME/CFS or Long COVID interventions specifically address cognitive dysfunction in the pediatric or adolescent population.

OPPORTUNITIES FOR TRANSLATING PROMISING APPROACHES TO LYME IACI

Through the survey of systematic reviews and meta-analyses of ME/CFS and Long COVID clinical research summarized above, the committee did not identify specific treatment approaches with sufficient support of beneficial effects and determined that the available evidence do not support prioritizing development or translation of these interventions to treat Lyme IACI. This should not be interpreted to mean that these treatment approaches do not have merit and should not be pursued as potential treatments for Lyme IACI. Instead, there is an opportunity for future evaluations of potential IACI treatments to be conducted with trials that incorporate—and stratify results according to—different IACI populations, including the Lyme IACI population. Given the similarities in the major symptoms, these future clinical trials can be developed to address a shared symptom and consider enrollment criteria based on a carefully defined syndromic definition that includes people with Lyme IACI along with others with ME/CFS and Long COVID. Likewise, research findings on disease mechanisms in other IACI can be explored to understand if these findings also apply for Lyme IACI.

There may be concerns that treatments to address disease symptoms rather than etiology or a fully known mechanistic pathway may be imprecise and do not address the need for curative treatments. However, therapeutics that aim to alleviate symptoms have been developed and approved for many intractable diseases while research to elucidate the pathogenesis and root cause continue being carried out. Examples range from mental health (e.g., depression) to autonomic disorders that have been reported for IACI (e.g., clinical studies on repurposed drugs for symptoms of POTS) (Cui et al., 2024; Vernino et al. 2021). Notably, the etiology of the three examples are unknown, but a number of pharmaceutical and nonpharmaceutical interventions have been identified to mitigate the disease manifestations and research to develop new treatments remain active. The approach to developing new treatments for IACI through symptom mitigation would focus on any available knowledge of the immediate causes for the symptoms, identify if there are parallels with other known diseases, and design studies such that data and samples can be collected to further understanding of the disease mechanism(s). One example of success in developing new treatments through this research approach is in fibromyalgia, a chronic condition with indeterminate etiology and symptoms similar to those in other IACI, particularly ME/CFS (Box 3-1).

Ongoing Lyme IACI Trials Informed by Other Disease Areas

There are few ongoing clinical trials registered on ClinicalTrials.gov for interventions to address Lyme IACI that draw from findings in other disease areas such as Long COVID, ME/CFS, and fibromyalgia.2 These interventions are briefly discussed below. While these interventions are in

___________________

2 This section highlights clinical trials that are listed as active or suspended on ClinicalTrials.gov as of March 17, 2025. It does not include review of trials that have been terminated or withdrawn.

the early stages of evaluation, they demonstrate the potential for translating treatment approaches from disease areas similar to those of Lyme IACI. As of March 2025, there are also a number of other ongoing clinical trials that explore treatments for Long COVID and ME/CFS; however, these experimental interventions have not been applied to Lyme IACI.3

Vagus Nerve Stimulation

Vagus nerve stimulation (VNS) is a procedure using a medical device to stimulate the vagus nerve with electrical impulses, which engages both afferent and efferent fibers to alter brain activity and systemic inflammation (Mayo Clinic, 2023). The implanted device has been approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) to treat pharmaco-resistant epilepsy and severe, recurrent depression as well as for use in stroke rehabilitation programs. There are also noninvasive devices that may be held against the skin of the neck to stimulate the cervical branch of the nerve or on the ear to stimulate its auricular branch, which has only afferent fibers. Noninvasive VNS devices haves been used to treat cluster headaches and migraines and have been shown to block pain signals (Mayo Clinic, 2023). In recent years, pilot studies using VNS to treat individuals with Long COVID has demonstrated early but promising effects for symptoms including fatigue, sleep, and mood (Khan et al., 2024; Lladós et al., 2024). There is an ongoing clinical trial investigating transcutaneous auricular VNS in people with persistent symptoms after Lyme disease (NCT05776251) (Columbia University, n.d., 2024).

Transcranial Direct Current Stimulation

Transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS) is performed using a noninvasive neuromodulation medical device that delivers a low electrical current to the scalp of an individual and modulates brain functions. tDCS does not alter brain structure but instead selectively modulates neuronal activity in regions of the brain to alter brain activity (Thair et al., 2017). The device is not currently FDA-approved for use outside of clinical research. A systematic review and meta-analysis of six randomized trials of tDCS for the treatment of major depressive disorder found that tDCS was superior to placebo and comparable to antidepressant drugs in addressing depression symptoms (Brunoni et al., 2016). A trial of the medical

___________________

3 Clinical trials for Long COVID and ME/CFS can be found through searching on ClinicalTrials.gov, CenterWatch (https://www.centerwatch.com/clinical-trials/listings) or on patient organization websites such as the American Myalgic Encephalomyelitis and Chronic Fatigue Syndrome Society (https://ammes.org/clinical-trials/) (accessed March 16, 2025).

device for the treatment of symptoms of Lyme IACI was recently launched (NCT03500770). The Clinical Trials Network for Lyme and Other Tick-Borne Diseases is planning to test tDCS and cognitive retraining for the treatment of brain fog and will plan to examine the feasibility of long-term tDCS for individuals with persistent cognitive symptoms following a Lyme infection (Columbia University, n.d.). tDCS is also being tested by the RECOVER-NEURO clinical trial to assess the devices’ impacts on Long COVID symptoms, such as brain fog (RECOVER, 2024).

Sana Device

The Sana Device is a wearable device that uses a combination of audio and visual stimulation to encourage mental relaxation with the goal of reducing chronic pain, among other intended health effects. It does not have FDA approval for treatment of any medical conditions, but it has been tested in clinical trials for relieving symptoms of fibromyalgia, as well as chronic neuropathic pain. Results are not available for the fibromyalgia study, and results from the chronic pain study, which have not yet gone through peer review, suggest the device was effective in reducing pain in the small study sample (Tabacof et al., 2024). There is currently a clinical trial to evaluate the effectiveness of the device on reducing chronic pain associated with PTLDS (NCT06655844).

Psilocybin

Psilocybin is a psychedelic agent that has been tested to treat several neurological and psychiatric conditions. Psilocybin is also being evaluated in a pilot study for the treatment of symptom burden in individuals with post-treatment Lyme disease (PTLD) (Johns Hopkins Medicine, 2024). The study is expected to be completed in April of 2025 (JHU, 2024).

Lumbrokinase

Building on Long COVID research that identified amyloid fibrin(ogen) particles as a potential cause for fatigue and other dysautonomia symptoms, thrombolytic enzymes, including lumbrokinase, have been proposed as potential therapeutic agents for Long COVID (Kell et al., 2024). Lumbrokinase is available as an oral supplement but does not have approved pharmaceutical indications (Mihara et al., 1991). A recent clinical trial has been initiated to test the efficacy of lumbrokinase in treating adults with Long COVID, PTLDS, or ME/CFS (Putrino et al., n.d.) (NCT06511050).

Applying New Research Methods to Lyme IACI

Opportunities for knowledge sharing between Lyme IACI and other conditions are not limited to breakthrough biomedical or clinical findings. Sharing technical knowledge such as methods and pitfalls learned from Long COVID research can facilitate application of new techniques to Lyme IACI studies that may unveil novel findings. A comparison between research into neurological manifestations of Long COVID and Lyme IACI is one example of the imbalance in application of modern research tools between two disease areas that share similar neurocognitive symptoms (Box 3-2). While early findings on potential links between neurological structure and function in Long COVID require further confirmatory research, sharing of techniques, protocols, and study designs can promote uptake of new technologies that have not been previously applied to Lyme IACI and facilitate coordination that enable meta-analyses across disease areas.

Epigenomics are another emerging area of Long COVID research with potential application to Lyme IACI. Infections are capable of triggering epigenetic changes, such as DNA methylation, which alter gene expression and have been known to contribute to disease pathogenesis for multiple conditions including ME/CFS (de Vega and McGowan, 2017). Studies of individuals with Long COVID have also described methylation of genes involved in immune responses and other biological processes that may shed light on the disease mechanism (Calzari et al., 2024; Lee et al., 2024). A genomewide DNA methylation study has been conducted in participants with neuroborreliosis following a B. burgdorferi infection (Henningsson et al., 2024), but epigenomic studies, which may contribute to improved understanding of pathogenesis, have yet to be conducted in a population with Lyme IACI.

Conclusion 3-2: Research findings for any single IACI may be informative for other IACI. Coordination to studying these illnesses and conditions can advance research for all IACI, including Lyme IACI.

Lessons from Diagnosis of Other Infection-Associated Chronic Illnesses

There are no specific diagnostic tests for Lyme IACI (see Chapter 2), Long COVID, or ME/CFS due to the incomplete understanding of etiology and lack of objective markers (IOM, 2015; NASEM, 2024a). Biomarker research is ongoing for Long COVID and ME/CFS and, if successful, may be transformative for both the development of potential diagnostic tests (Davis et al., 2023) and advancing our understanding of these conditions. Moreover, research on biomarkers in conditions like Long COVID may

inform the development of diagnostics for Lyme IACI if similar mechanisms exist. For example, several similar psychiatric conditions share the same inflammation-related biomarkers (Yuan et al., 2019).

In the absence of validated diagnostic tests, a syndromic definition has been developed for Long COVID (NASEM, 2024a), and ME/CFS has had a multitude of proposed case definitions and diagnostic criteria (IOM, 2015; Lim and Son, 2020). The 2015 Institute of Medicine (IOM) diagnostic criteria for ME/CFS enabled clinicians to make diagnoses based primarily on the presence of symptoms, as opposed to the lengthy approach that largely relied on a diagnosis by exclusion, which was commonly used before the diagnostic criteria (Bateman et al., 2021). Making a diagnosis of ME/CFS still involves a degree of ruling out other potential causes of an individual’s symptoms, but the availability of standardized, evidence-based definitions is critical for making reliable and timely diagnoses. In addition, significant efforts have been made over the years to develop and validate patient-reported outcome measures for use in ME/CFS research that will likely complement the use of biomarkers in clinical diagnosis. These standardized and validated assessments of symptoms include those developed specifically for ME/CFS, such as the DePaul Symptom Questionnaire, and more general research tools such as the Short Form 36-Item Health Survey (Jason & Sunnquist, 2018).4

The definitions and criteria for Long COVID and ME/CFS, while imperfect, can be useful in guiding clinical diagnoses and appropriate care. However, it is not known whether there are meaningful differences among different IACI that would affect treatment. Research that compares treatment responses across participants with different IACI diagnoses will be needed to determine if certain interventions are more effective for certain populations. In the absence of such evidence, tailoring treatment to the symptoms of each individual patient will continue to be important to clinical practice.

Notably, disease definitions may have multiple applications. A definition for the purposes of research may need to be more narrowly tailored to ensure that the patient populations in various studies are comparable. A clinical definition used in diagnosis or for disability determinations may be broader to suggest possible treatment approaches or facilitate access to care or benefits. In the example of ME/CFS, the IOM criteria are more commonly used in the clinical care setting, while the Canadian Consensus Criteria are more frequently seen as a definition in clinical research.5

Key research findings must be incorporated into disease definitions to maintain relevance and clinical utility. Definitions of ME/CFS have been

___________________

4 Common data elements for ME/CFS list many other patient-reported measures of study outcomes and end points, see: NINDS, n.d.

5 As presented to the committee in open session by Nancy Klimas on July 11, 2024.

revised many times to reflect emerging evidence and the Long COVID definition was developed with the intention to be reviewed at regular intervals for necessary updates (Lim and Son, 2020; NASEM, 2024a). Given the incomplete and evolving understanding of Lyme IACI, it is critical that future efforts to develop research or clinical definitions for Lyme IACI follow a similar approach to allow periodic review and modification to reflect new evidence as it develops.

Other Considerations in Research Strategies for Infection-Associated Chronic Illnesses

In addition to potential directions for clinical research, opportunities to incorporate new techniques, and approaches to developing working definitions in the absence of diagnostic tests for Lyme IACI, there are several strategies that have helped advance research on other IACI. These strategies are, to date, generally absent or underused in the field of Lyme IACI research.

Standardization

A standardized and clear definition for a patient population, and any relevant subgroups, can streamline clinical trial recruitment and guide application of research findings to the appropriate group in clinical practice. The consensus definitions for Long COVID and ME/CFS provide a common reference point for researchers to interpret results from across different studies. For Lyme IACI, PTLDS is used for research purposes and describes a well-defined group within the Lyme IACI population (see Chapter 2; Wormser et al., 2006). While PTLDS has an important role in the research that has been conducted to date, the balance toward its stringency inevitably excludes many individuals with similar symptoms for whom the evidence for prior Lyme disease is uncertain or who have less severe symptoms. Standardized definitions for Lyme IACI would serve as a common reference point to advance research for this disease and could provide a clear pathway for including people who do not fit the PTLDS criteria in future research. To facilitate a coordinated IACI research approach, efforts to develop a Lyme IACI definition could consider how it aligns or differs from the limitations, rationale, and steps for improvement for the proposed Long COVID definition (Ely et al., 2024).

Standardization in scientific research also ensures there are commonly accepted outcome measures that promote a consistent approach to collecting data (e.g., patient characteristics, study endpoints) and allow for meta-analyses and other cross-study comparisons. Data standardization can be particularly important when symptom assessments include subjective

measures that may be obtained through a variety of tools which are not always interchangeable or comparable, and may not be validated (Machado et al., 2021). For example, common measurements for fatigue in the IACI literature reviewed in this chapter included a number of tools that differed in their utility, such as the Fatigue Severity Scale (a unidimensional tool with good potential to detect change over disease course), and Fatigue Impact Scale (a multidimensional tool with poor potential to detect change over disease course), and the relevant subscale of the generic short-form 36 (SF-36) (Whitehead, 2009).6 Efforts to standardize patient-reported outcome measures include NIH-supported development of several robust measurement systems, including the Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS®) and Neuro-QoLTM (Cella et al., 2012; Health Measures, 2025; NIH OSC, 2025). Research on other IACI has benefited from establishment of core data standards and preferred outcome measurement tools. The National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke, in collaboration with the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, convened working groups to assemble common data elements (CDEs) for clinical research on ME/CFS (NIH, n.d.b). The publication of these CDEs has helped to orient the research field around reliable and consistent outcome measures which enable researchers to make direct comparisons between studies.7 Efforts to develop CDEs for standardization in Long COVID research is also in progress (Walters et al., 2024).

Coordination

In 2022, the Department of Health and Human Services released the National Research Action Plan describing the federal government’s research agenda for Long COVID and ongoing research efforts across different federal agencies (HHS, 2022). The action plan also serves as a blueprint to guide future investment, identify research priorities, and outline actions to advance those priorities. One such priority is a call to apply the knowledge gained from ME/CFS and other IACI to address Long COVID. The action plan also calls to situate Long COVID research within the broader IACI context and acknowledges that advancement of Long COVID research needs to be built on intersectoral collaborations among people with IACI, and academic and private sector research, as well as interdisciplinary collaborations. Coordination through a similar action plan for people living with Lyme IACI, researchers, and research funders can provide a strategic

___________________

6 Unidimensional fatigue measure tool is one that includes measure of just one factor, usually fatigue severity. Multidimensional measure tool capture two or more factors (e.g., fatigue severity, duration, pattern over time, etc.).

7 As presented to the committee in open session by Nancy Klimas on July 11, 2024.

vision to advance Lyme IACI research within the broader context of other similar conditions. In particular, coordination of research efforts—and standards, where appropriate—across various IACI would facilitate knowledge and resource sharing that could accelerate treatment innovations for people with IACI symptoms regardless of the initial infectious agent. This includes the potential identification of common disease pathways and therapeutic targets, but also the identification of differences between Lyme IACI and other conditions. The HHS Office of Long COVID Research and Practice, though closing, was a vital mechanism to coordinate government initiatives on Long COVID and demonstrates the value of aligning efforts across a complex research ecosystem (HHS, 2025).

One option for aligning research efforts across multiple sites is to establish coordinating centers. There are different ways to structure and run coordinating centers, but core functions include administrative organization and operation of trials or research programs that are often complex, interdisciplinary, and multisite. For example, tasks that coordinating centers generally undertake on behalf of a research network or program can be categorized into the following four themes:

- structural: coordinating centers may provide input on the organizational structure or governance of a research program;

- collaboration development: facilitating connections between and synergy within the research program or network, including the prioritization of activities;

- operational: administrative and technological tasks, with a focus on promoting compatibility; and

- data: efforts to promote data interoperability between individual research sites (Rolland et al., 2017).

Several coordinating centers have demonstrated the utility of this design as an effective tool that reduces administrative burden for complex trials and improves research efficiency (Rolland et al., 2011, 2017). A coordinating center can also support a network of decentralized clinical trials, which may allow a larger participant pool from different geographic locations, and a convergence of greater expertise than trials that rely on personnel at a single site.

The NIH already supports a data management and coordinating center for the ME/CFS Research Network (MECFS Net, n.d.) and an administrative coordinating center for the Researching COVID to Enhance Recovery (RECOVER) initiative on Long COVID (RTI International, 2021). However, there is not currently a coordinating center dedicated to Lyme IACI research. As Chapter 4 will discuss, there is a Clinical Trials Network Coordinating Center for Lyme and other Tick-borne Diseases, though as

the name indicates, the center covers a broad variety of diseases beyond Lyme IACI.

Conclusion 3-3: The Lyme IACI field needs leadership in promoting and supporting coordination between research sites and investigators to conduct research with minimal redundancy, maximize outcomes from the limited available resources, and enable cross-IACI initiatives.

Expanded Data Collection

Data are the key to unlocking scientific discoveries. But when conducting research, it is critical to collect and analyze the right data—data that can answer the target research questions. Expanded data collection is only cost-effective when there is a clear benefit, and otherwise may lead to waste in time and unnecessary harm for trial participants, loss of time and effort for research staff and participants, and excess samples that consume precious storage space. Therefore, it is important to have a strategy for collecting the necessary data to answer research questions.

One strategy to expanding data collections could be drawn from the recent deep phenotyping study conducted to elucidate the pathogenesis of post-infectious ME/CFS. This involves measuring a broad array of health markers from participants (e.g., cognition, motor skills, cardiopulmonary health, laboratory testing, imaging results) for comparison between individuals with ME/CFS and health controls (Walitt et al., 2024). In this study, researchers performed “physiological measures, physical and cognitive performance testing, and biochemical, microbiological, and immunological assays of blood, cerebrospinal fluid, muscle, and stool” of the recruited participants, accruing a massive dataset that could be probed to detect unique features of the ME/CFS patients. Despite a small sample size of 17 ME/CFS patients and 21 healthy controls, data from the study led to a hypothesis involving simultaneous immune dysfunction and microbiome dysbiosis that may result in a cascade of symptoms. The data also pointed to several biomarkers that could assist in the diagnosis of ME/CFS, highlighted sex differences, and identified potential treatment targets based on the proposed pathogenesis model.

Another strategy is to broaden, instead of deepen, the data that are collected. To address challenges with the overlapping symptoms and potential infectious origins of different IACI, studies could include participants from a variety of IACI (possibly also people with similar symptoms of uncertain origin). Studies that collect data on multiple IACI provide an opportunity to more rapidly identify commonalities and potential treatments with wide benefit for different diseases. Analysis of these large datasets could also identify treatments for specific subsets of patients, including patient subgroups, or mechanistic understandings may be discernible across a

multi-IACI dataset. It can be challenging to design studies that identify and ideally stratify relevant subgroups across these different diseases, which may have different etiology and pathogenesis, including heterogeneity in risk factors such as prior history of trauma, environmental exposures, or genetics. If these strata are not identified and analyzed separately, important findings could be missed among the combined study sample. Additionally, this combined research effort would prove counterproductive if there are significant differences in the etiology, pathogenesis, or risk factor for these diseases. To guard against this possibility, it is important to maintain relevant history and key characteristics of study participants, which can be done through using a standardized core set of common data elements to further facilitate interoperability of the large dataset.

Deepening and broadening the data used in research can be complementary and mutually reinforcing approaches to better understand Lyme IACI. Standardizing outcome measures and definitions are central to successfully collecting and making use of expanded data collections. New approaches to obtaining and analyzing this data are discussed in Chapter 4.

LESSONS LEARNED

Many knowledge gaps remain in understanding the etiology of IACI, impeding the ability to develop treatments and diagnostics for these diseases. This is the case for the recently emerged condition of Long COVID as well as for other chronic syndromes that have been known for decades, including ME/CFS and Lyme IACI. The limiting factor to progress in the basic understanding of IACI does not appear to be exhaustion of scientific or technological exploration. Instead, the interdisciplinary, comprehensive approach that is necessary to address these complex illnesses and conditions requires significant and sustained investment in high quality basic and clinical research.

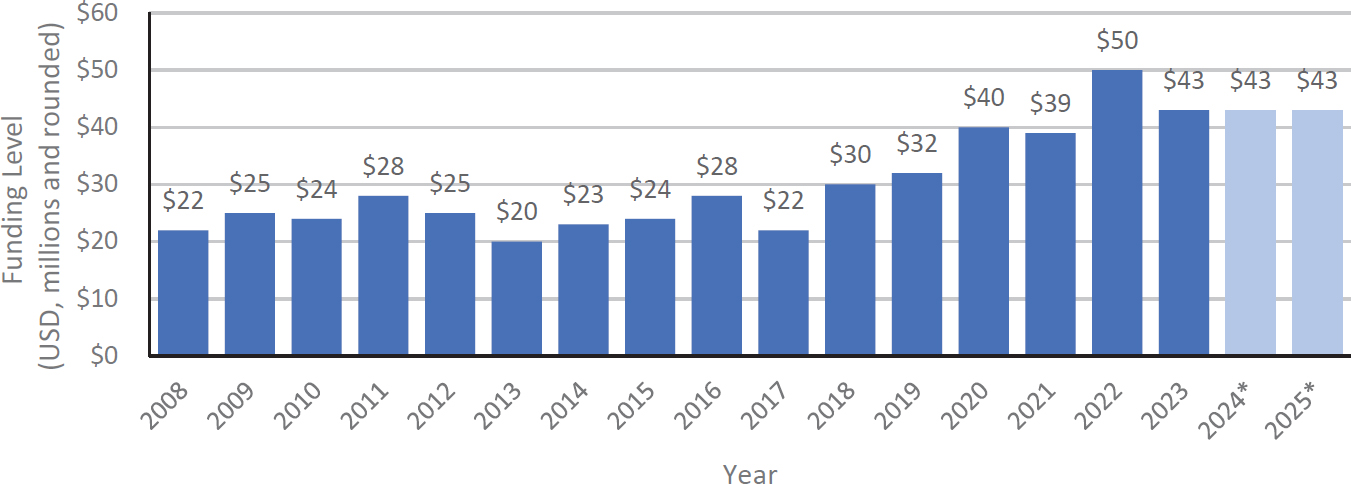

Widespread acknowledgment of the public health burden from COVID-19 and Long COVID among policymakers and research funders has led to significant support for Long COVID research that was essential to yielding the substantial body of evidence for this condition. The RECOVER Initiative, established in 2021 as a nationwide research program to fully understand, diagnose, and treat Long COVID, received $1.7 billion in funding through a combination of Congressional appropriations and repurposed NIH funding (NIH, 2024). In contrast, Lyme disease research, which encompasses research on Lyme IACI, has received a total of $475 million in NIH funding over 15 years between 2008 and 2023 (Figure 3-1) (NIH, n.d.a). The limited funding for Lyme IACI research has been attributed to varied factors, including a historic lack of recognition of the disease, poor

understanding of the pathophysiology,8 shifting priorities in the absence of a national research strategy, and challenges with alignment and coordination among different research partners—such as people with lived experience and funding organizations.9 Increased funding has a direct impact on the quantity and quality of studies that can be conducted. While an imperfect count, a search of for active trials on “Long COVID” through ClinicalTrials.gov yields 299 results, whereas the same search for “posttreatment Lyme disease” returns 9 studies.10 More broadly speaking, while NIH-funded programs and initiatives are crucial to advancing biomedical research and scientific knowledge, adjunctive research often led through the expertise of other agencies are also important for addressing a wide-reaching public health problem like Lyme IACI. For example, the Agency for Health Research and Quality supports expansion of comprehensive, multidisciplinary clinics for Long COVID, which can play a key role as community trial sites (AHRQ, 2025). While the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention is largely involved in surveillance and prevention of vector-borne diseases, they can be key partners in conducting necessary epidemiological studies (see Chapter 2), participating in development of new diagnostics and evaluate their use in case surveillance, and educating clinicians to disseminate use of research and clinical definitions for Lyme IACI.

Conclusion 3-4: Lyme IACI research is conducted with limited resources without a centralized body and with no formal standardized definition of patient population, outcomes, or mechanisms to promote collaboration among investigators, transparency of existing resources, and data sharing.

Support for long-term, sustainable clinical research infrastructure and initiatives, including adjunctive research, may be costly as they will likely be years-long endeavors involving investigators across multiple locations and disciplines. But long-term engagement also builds a collaborative ecosystem among researchers and patient participants that can provide return on the initial investment by enabling more rapid mobilization for future work and streamlined dissemination of study outcomes.

Although the available evidence does not support the immediate translation of any particular intervention from ME/CFS and Long COVID research to Lyme IACI, the adoption of the research approaches from these conditions is supported by available evidence. Common standards for research definitions and metrics would greatly improve the capacity to draw

___________________

8 As presented to the committee in open session by Wendy Adams on July 11, 2024.

9 As presented to the committee in open session by Leith States on July 11, 2024.

10 Search performed at https://clinicaltrials.gov/ on January 15, 2025.

NOTES: Asterisks indicate that funding levels for 2024 and 2025 are estimates provided by NIH and have not been finalized as of March 2025. Research for persistent symptoms related to Lyme disease is part of this overall funding. NIH = National Institutes of Health.

comparisons between individual studies on Lyme IACI. Centralized coordination will be particularly important for streamlining Lyme IACI research efforts—and IACI research broadly, and would help increase efficiency and avoid duplicative studies and efforts. Research coordination within Lyme IACI and among different IACI would also promote the sharing of data and limited resources among researchers. Applying these lessons in Lyme IACI research will be important to advance the pace of discoveries.

REFERENCES

Adler, B. L., T. Chung, P. C. Rowe, and J. Aucott. 2024. Dysautonomia following Lyme disease: A key component of post-treatment lyme disease syndrome? Front Neurology 15:1344862.

AIM ImmunoTech. 2024. AIM ImmunoTech announces that analysis of AMP-518 complete clinical patient data underscores Ampligen’s potential to improve the post-covid condition of fatigue. https://aimimmuno.com/aim-immunotech-announces-that-analysis-of-amp-518-complete-clinical-patient-data-underscores-ampligens-potential-to-improve-the-post-covid-condition-of-fatigue/ (accessed January 27, 2025).

Ali, A., L. Vitulano, R. Lee, T. R. Weiss, and E. R. Colson. 2014. Experiences of patients identifying with chronic Lyme disease in the healthcare system: A qualitative study. BMC Family Practice 15(1):79.

Appelman, B., B. T. Charlton, R. P. Goulding, T. J. Kerkhoff, E. A. Breedveld, W. Noort, C. Offringa, F. W. Bloemers, M. van Weeghel, B. V. Schomakers, P. Coelho, J. J. Posthuma, E. Aronica, W. Joost Wiersinga, M. van Vugt, and R. C. I. Wüst. 2024. Muscle abnormalities worsen after post-exertional malaise in Long COVID. Nature Communications 15(1):17.

AHRQ (Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality). 2025. AHRQ efforts to address Long COVID. https://www.ahrq.gov/coronavirus/long-covid.html (accessed March 16, 2025).

Arron, H. E., B. D. Marsh, D. B. Kell, M. A. Khan, B. R. Jaeger, and E. Pretorius. 2024. Myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome: The biology of a neglected disease. Frontiers in Immunology 15:1386607.

Ascough, C., H. King, T. Serafimova, L. Beasant, S. Jackson, L. Baldock, A. E. Pickering, J. Brooks, and E. Crawley. 2020. Interventions to treat pain in paediatric CFS/ME: A systematic review. BMJ Paediatrics Open 4(1):e000617.

Aucott, J. N., A. W. Rebman, L. A. Crowder, and K. B. Kortte. 2013. Post-treatment Lyme disease syndrome symptomatology and the impact on life functioning: Is there something here? Quality of Life Research 22(1):75–84.

Bai, N. A., and C. S. Richardson. 2023. Posttreatment Lyme disease syndrome and myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome: A systematic review and comparison of pathogenesis. Chronic Diseases and Translational Medicine 9(3):183–190.

Bateman, L., A. C. Bested, H. F. Bonilla, B. V. Chheda, L. Chu, J. M. Curtin, T. T. Dempsey, M. E. Dimmock, T. G. Dowell, D. Felsenstein, D. L. Kaufman, N. G. Klimas, A. L. Komaroff, C. W. Lapp, S. M. Levine, J. G. Montoya, B. H. Natelson, D. L. Peterson, R. N. Podell, I. R. Rey, I. S. Ruhoy, M. A. Vera-Nunez, and B. P. Yellman. 2021. Myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome: Essentials of diagnosis and management. Mayo Clinic Proceedings 96(11):2861–2878.

Besteher, B., T. Rocktäschel, A. P. Garza, M. Machnik, J. Ballez, D.-L. Helbing, K. Finke, P. Reuken, D. Güllmar, C. Gaser, M. Walter, N. Opel, and I. Rita Dunay. 2024. Cortical thickness alterations and systemic inflammation define Long COVID patients with cognitive impairment. Brain, Behavior, and Immunity 116:175–184.

Blockmans, D., P. Persoons, B. Van Houdenhove, M. Lejeune, and H. Bobbaers. 2003. Combination therapy with hydrocortisone and fludrocortisone does not improve symptoms in chronic fatigue syndrome: A randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind, crossover study. American Journal of Medicine 114(9):736–741.

Blockmans, D., P. Persoons, B. Van Houdenhove, and H. Bobbaers. 2006. Does methylphenidate reduce the symptoms of chronic fatigue syndrome? American Journal of Medicine 119(2):167.E23–167.E30.

Bonilla, H., M. J. Peluso, K. Rodgers, J. A. Aberg, T. F. Patterson, R. Tamburro, L. Baizer, J. D. Goldman, N. Rouphael, A. Deitchman, J. Fine, P. Fontelo, A. Y. Kim, G. Shaw, J. Stratford, P. Ceger, M. M. Costantine, L. Fisher, L. O’Brien, C. Maughan, J. G. Quigley, V. Gab-bay, S. Mohandas, D. Williams, and G. A. McComsey. 2023. Therapeutic trials for Long COVID-19: A call to action from the interventions taskforce of the RECOVER initiative. Frontiers in Immunology 14:1129459.

Brunoni, A. R., A. H. Moffa, F. Fregni, U. Palm, F. Padberg, D. M. Blumberger, Z. J. Daskalakis, D. Bennabi, E. Haffen, A. Alonzo, and C. K. Loo. 2016. Transcranial direct current stimulation for acute major depressive episodes: Meta-analysis of individual patient data. British Journal of Psychiatry 208(6):522–531.

Calzari, L., D. F. Dragani, L. Zanotti, E. Inglese, R. Danesi, R. Cavagnola, A. Brusati, F. Ranucci, A. M. Di Blasio, L. Persani, I. Campi, S. De Martino, A. Farsetti, V. Barbi, M. Gottardi Zamperla, G. N. Baldrighi, C. Gaetano, G. Parati, and D. Gentilini. 2024. Epigenetic patterns, accelerated biological aging, and enhanced epigenetic drift detected 6 months following COVID-19 infection: Insights from a genome-wide DNA methylation study. Clinical Epigenetics 16(1):112.

Cao, B., Q. Xu, Y. Shi, R. Zhao, H. Li, J. Zheng, F. Liu, Y. Wan, and B. Wei. 2024. Pathology of pain and its implications for therapeutic interventions. Signal Transduction and Targeted Therapy 9(1):155.

Castro-Marrero, J., M. D. Cordero, M. J. Segundo, N. Sáez-Francàs, N. Calvo, L. Román-Malo, L. Aliste, T. Fernández de Sevilla, and J. Alegre. 2015. Does oral coenzyme Q10 plus NADH supplementation improve fatigue and biochemical parameters in chronic fatigue syndrome? Antioxidants & Redox Signaling 22(8):679–685.

Cella, D., J. S. Lai, C. J. Nowinski, D. Victorson, A. Peterman, D. Miller, F. Bethoux, A. Heinemann, S. Rubin, J. E. Cavazos, A. T. Reder, R. Sufit, T. Simuni, G. L. Holmes, A. Siderowf, V. Wojna, R. Bode, N. McKinney, T. Podrabsky, K. Wortman, S. Choi, R. Gershon, N. Rothrock, and C. Moy. 2012. Neuro-QoL: Brief measures of health-related quality of life for clinical research in neurology. Neurology 78(23):1860-1867.

Chee, Y. J., B. E. Fan, B. E. Young, R. Dalan, and D. C. Lye. 2023. Clinical trials on the pharmacological treatment of Long COVID: A systematic review. Journal of Medical Virology 95(1):e28289.

Chen, X. Y., C. L. Lu, Q. Y. Wang, X. R. Pan, Y. Y. Zhang, J. L. Wang, J. Y. Liao, N. C. Hu, C. Y. Wang, B. J. Duan, X. H. Liu, X. Y. Jin, J. Hunter, and J. P. Liu. 2024. Traditional, complementary and integrative medicine for fatigue post COVID-19 infection: A systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Integrative Medicine Research 13(2):101039.

Cheng, X., M. Cao, W.-F. Yeung, and D. S. T. Cheung. 2024. The effectiveness of exercise in alleviating Long COVID symptoms: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Worldviews on Evidence-Based Nursing 21(5):561–574.

Choutka, J., V. Jansari, M. Hornig, and A. Iwasaki. 2022. Unexplained post-acute infection syndromes. Nature Medicine 28(5):911–923.

Cui, L., S. Li, S. Wang, X. Wu, Y. Liu, W. Yu, Y. Wang, Y. Tang, M. Xia, and B. Li. 2024. Major depressive disorder: Hypothesis, mechanism, prevention and treatment. Signal Transduction and Targeted Therapy 9(1):30.

Clark, L. V., F. Pesola, J. M. Thomas, M. Vergara-Williamson, M. Beynon, and P. D. White. 2017. Guided graded exercise self-help plus specialist medical care versus specialist medical care alone for chronic fatigue syndrome (GETSET): A pragmatic randomised controlled trial. Lancet 390(10092):363–373.

Cleare, A. J., E. Heap, G. S. Malhi, S. Wessely, V. O’Keane, and J. Miell. 1999. Low-dose hydrocortisone in chronic fatigue syndrome: A randomised crossover trial. The Lancet 353(9151):455–458.

Columbia University. n.d. Clinical Trials Network for Lyme and Other Tick-Borne Diseases: Active clinical studies. https://www.lymectn.org/Studies.aspx (accessed January 15, 2025).

Davis, H. E., L. McCorkell, J. M. Vogel, and E. J. Topol. 2023. Long COVID: Major findings, mechanisms and recommendations. Nature Reviews Microbiology 21(3):133–146.

Deale, A., T. Chalder, I. Marks, and S. Wessely. 1997. Cognitive behavior therapy for chronic fatigue syndrome: A randomized controlled trial. American Journal of Psychiatry 154(3):408–414.

de Oliveira, B. F. A., P. R. C. Carvalho, A. S. de Souza Holanda, R. Dos Santos, F. A. X. da Silva, G. W. P. Barros, E. C. de Albuquerque, A. T. Dantas, N. G. Cavalcanti, A. Ranzolin, A. Duarte, and C. D. L. Marques. 2019. Pilates method in the treatment of patients with chikungunya fever: A randomized controlled trial. Clinical Rehabilitation 33(10):1614–1624.

de Vega, W. C., and P. O. McGowan. 2017. The epigenetic landscape of myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome: Deciphering complex phenotypes. Epigenomics 9(11):1337–1340.

El-Mokadem, J. F. K., K. DiMarco, T. M. Kelley, and L. Duffield. 2023. Three principles/innate health: The efficacy of psycho-spiritual mental health education for people with chronic fatigue syndrome. Spirituality in Clinical Practice 10(4):289–303.

Ely, E. W., L. M. Brown, and H. V. Fineberg. 2024. Long COVID defined. New England Journal of Medicine 391(18):1746–1753.

Fallon, B. A., J. Keilp, I. Prohovnik, R. V. Heertum, and J. J. Mann. 2003. Regional cerebral blood flow and cognitive deficits in chronic Lyme disease. The Journal of Neuropsychiatry Clinical Neuroscience 15(3):326–332.

Fitzcharles, M. A., S. P. Cohen, D. J. Clauw, G. Littlejohn, C. Usui, and W. Häuser. 2021. Nociplastic pain: Towards an understanding of prevalent pain conditions. The Lancet 397(10289):2098–2110.

Fowler-Davis, S., R. Young, T. Maden-Wilkinson, W. Hameed, E. Dracas, E. Hurrell, R. Bahl, E. Kilcourse, R. Robinson, and R. Copeland. 2021. Assessing the acceptability of a co-produced Long COVID intervention in an underserved community in the UK. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18(24):13191.

Fox, T., B. J. Hunt, R. A. Ariens, G. J. Towers, R. Lever, P. Garner, and R. Kuehn. 2023. Plasmapheresis to remove amyloid fibrin(ogen) particles for treating the post-COVID-19 condition. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 7(7):CD015775.

Geraghty, K. J. 2017. ‘Pace-gate’: When clinical trial evidence meets open data access. Journal of Health Psychology 22(9):1106–1112.

Gracely, R. H., F. Petzke, J. M. Wolf, and D. J. Clauw. 2002. Functional magnetic resonance imaging evidence of augmented pain processing in fibromyalgia. Arthritis & Rheumatology 46(5):1333–1343.

Greene, C., R. Connolly, D. Brennan, A. Laffan, E. O’Keeffe, L. Zaporojan, J. O’Callaghan, B. Thomson, E. Connolly, R. Argue, J. F. M. Meaney, I. Martin-Loeches, A. Long, C. N. Cheallaigh, N. Conlon, C. P. Doherty, and M. Campbell. 2024. Blood–brain barrier disruption and sustained systemic inflammation in individuals with Long COVID-associated cognitive impairment. Nature Neuroscience 27(3):421–432.

Halford, J., and T. Brown. 2009. Cognitive–behavioural therapy as an adjunctive treatment in chronic physical illness. Advances in Psychiatric Treatment 15(4):306–317.

Hausswirth, C., C. Schmit, Y. Rougier, and A. Coste. 2023. Positive impacts of a four-week neuro-meditation program on cognitive function in post-acute sequelae of COVID-19 patients: A randomized controlled trial. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 20(2):1361.

Hawkins, J., C. Hires, L. Keenan, and E. Dunne. 2022. Aromatherapy blend of thyme, orange, clove bud, and frankincense boosts energy levels in post-COVID-19 female patients: A randomized, double-blinded, placebo controlled clinical trial. Complementary Therapies in Medicine 67:102823.

HHS (Department of Health and Human Services). 2022. National research action plan on Long COVID. https://www.covid.gov/sites/default/files/documents/National-ResearchAction-Plan-on-Long-COVID-08012022.pdf (accessed November 27, 2024).

HHS. 2025. The office of Long COVID research and practice OLC. https://www.hhs.gov/longcovid/index.html (accessed March 27, 2025).

Health Measures. 2025. Search & view measures. https://www.healthmeasures.net/searchview-measures?task=Search.search (accessed March 15, 2025).

Henningsson, A. J., S. Hellberg, M. Lerm, and S. Sayyab. 2024. Genome-wide DNA methylation profiling in Lyme neuroborreliosis reveals altered methylation patterns of HLA genes. Journal of Infectious Diseases 229(4):1209–1214.

Hermans, L., J. Nijs, P. Calders, L. De Clerck, G. Moorkens, G. Hans, S. Grosemans, T. Roman De Mettelinge, J. Tuynman, and M. Meeus. 2018. Influence of morphine and naloxone on pain modulation in rheumatoid arthritis, chronic fatigue syndrome/fibromyalgia, and controls: A double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled, cross-over study. Pain Practice 18(4):418–430.

Huanan, L., W. Jingui, Z. Wei, Z. Na, H. Xinhua, S. Shiquan, S. Qing, H. Yihao, Z. Runchen, and M. Fei. 2017. Chronic fatigue syndrome treated by the traditional Chinese procedure abdominal tuina: A randomized controlled clinical trial. Journal of Traditional Chinese Medicine 37(6):819–826.

Huang, Y. H., H. C. Chen, K. W. Huang, P. C. Chen, C. J. Hu, C. P. Tsai, K. W. Tam, and Y. C. Kuan. 2015. Intravenous immunoglobulin for postpolio syndrome: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Neurology 15:39.

IOM (Institute of Medicine). 2015. Beyond myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome: Redefining an illness. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

James, R. J. E., and E. Ferguson. 2020. The dynamic relationship between pain, depression and cognitive function in a sample of newly diagnosed arthritic adults: A cross-lagged panel model. Psychological Medicine 50(10):1663–1671.

Janse, A., M. Worm-Smeitink, G. Bleijenberg, R. Donders, and H. Knoop. 2018. Efficacy of web-based cognitive–behavioural therapy for chronic fatigue syndrome: Randomised controlled trial. British Journal of Psychiatry 212(2):112–118.

Jason, L. A., and M. Sunnquist. 2018. The development of the DePaul Symptom Questionnaire: Original, expanded, brief, and pediatric versions. Front Pediatr 6:330.

JHU (Johns Hopkins University). 2024. Effects of psilocybin in post-treatment lyme disease. In: ClinicalTrials.gov. Available from https://clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT05305105?cond=Post-Treatment%20Lyme%20Disease&rank=5 (accessed November 27, 2025).

Johns Hopkins Medicine. 2024. Psychiatry and behavioral sciences. https://www.hopkinsmedicine.org/psychiatry/research/psychedelics-research (accessed January 15, 2025).

Johnson, L., S. Wilcox, J. Mankoff, and R. B. Stricker. 2014. Severity of chronic Lyme disease compared to other chronic conditions: A quality of life survey. PeerJ 2:e322.

Johnson, L., M. Shapiro, and J. Mankoff. 2018. Removing the mask of average treatment effects in chronic Lyme disease research using big data and subgroup analysis. Healthcare (Basel) 6(4):124.

Kaplan, C. M., E. Kelleher, A. Irani, A. Schrepf, D. J. Clauw, and S. E. Harte. 2024. Deciphering nociplastic pain: Clinical features, risk factors and potential mechanisms. Nature Reviews Neurology 20(6):347–363.

Karosanidze, I., U. Kiladze, N. Kirtadze, M. Giorgadze, N. Amashukeli, N. Parulava, N. Iluridze, N. Kikabidze, N. Gudavadze, L. Gelashvili, V. Koberidze, E. Gigashvili, N. Jajanidze, N. Latsabidze, N. Mamageishvili, R. Shengelia, A. Hovhannisyan, and A. Panossian. 2022. Efficacy of adaptogens in patients with long COVID-19: A randomized, quadruple-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Pharmaceuticals 15(3):345.

Keijmel, S. P., C. E. Delsing, G. Bleijenberg, J. W. M. van der Meer, R. T. Donders, M. Leclercq, L. M. Kampschreur, M. van den Berg, T. Sprong, M. H. Nabuurs-Franssen, H. Knoop, and C. P. Bleeker-Rovers. 2017. Effectiveness of long-term doxycycline treatment and cognitive-behavioral therapy on fatigue severity in patients with Q fever fatigue syndrome (Qure study): A randomized controlled trial. Clinical Infectious Diseases 64(8):998–1005.

Kell, D. B., M. A. Khan, B. Kane, G. Y. H. Lip, and E. Pretorius. 2024. Possible role of fibrinaloid microclots in postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome (POTS): Focus on Long COVID. Journal of Personalized Medicine 14(2):170.

Khan, M. W. Z., M. Ahmad, S. Qudrat, F. Afridi, N. A. Khan, Z. Afridi, Fahad, T. Azeem, and J. Ikram. 2024. Vagal nerve stimulation for the management of long COVID symptoms. Infectious Medicine 3(4):100149.