Charting a Path Toward New Treatments for Lyme Infection-Associated Chronic Illnesses (2025)

Chapter: 1 Introduction

1

Introduction

Lyme disease, or Lyme borreliosis, is the most common vector-borne disease in the United States (Rosenberg et al., 2018). While limitations in diagnosis and reporting continue to make accurate surveillance for Lyme disease difficult, estimates suggest that an average of 476,000 cases of Lyme disease were diagnosed each year between 2010 and 2018 (Kugeler et al., 2021). This represented a significant increase in the number of cases over the previous decade, which had an estimated 329,000 cases per year from 2005 to 2010 (Nelson et al., 2015). With effective antibiotic treatment, most people with Lyme disease recover. However, some individuals who have Lyme disease and receive the recommended antibiotic treatment still experience prolonged symptoms, sometimes for years, limiting the individual’s function and quality of life (Aucott et al., 2022). The presence of these symptoms following Lyme disease and corresponding antibiotic treatment is referred to in this report as Lyme infection-associated chronic illnesses (IACI). There are no accepted, standardized, or proven treatments for Lyme IACI, despite the significant burden of the condition for those living with it.

STUDY CONTEXT AND CHARGE

To explore opportunities for new treatments that could address this unmet need, the Steven & Alexandra Cohen Foundation asked the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine to assess the evidence base for the etiology and treatment of Lyme IACI and to clarify a pathway toward identifying and developing interventions for this disease state. In accordance with standard procedures, the National Academies formed an

independent ad hoc committee of 14 volunteer experts with the requisite knowledge and experience to address the five aspects of this challenging issue outlined in the statement of task (Box 1-1). The Committee on the Evidence Base for Lyme Infection-Associated Chronic Illnesses Treatment consisted of individuals with expertise in treating persistent symptoms associated with Lyme disease or similar conditions, clinical trials design and methodology, public health and epidemiology, neuroscience and infectious diseases research, health policy, medical ethics, community engagement, and individuals with lived experience with lingering symptoms associated with Lyme disease. This committee conducted a careful review of the current evidence, considered the perspectives shared by people affected by Lyme IACI, and sought input from clinicians and researchers working to address

Lyme and other IACI. The recommendations in this report are focused on providing a research framework for timely advancement of new treatment options for Lyme IACI by learning from similar conditions, incorporating lived experience, and shifting the current paradigm to prioritize clinical trials for treatments.

BACKGROUND

Diagnosis and Epidemiology of Lyme Disease

Lyme disease is caused by members of the Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato species complex, a group of spirochetal bacteria found in arthropod and vertebrate reservoirs and transmitted to humans via arthropod bites.1 Lyme disease is endemic throughout many regions in Europe, Asia, and North America, with environmental factors expected to drive further expansion (Stone et al., 2017). In the United States, Borrelia burgdorferi sensu stricto (i.e., B. burgdorferi) is the most common causative pathogen, though a handful of cases have been attributed to Borrelia mayonii since 2013.2,3 Clinical manifestations may differ between Lyme disease acquired in Europe and in the United States (Marques et al., 2021). The primary vectors transmitting B. burgdorferi to humans in North America are the black-legged ticks, Ixodes scapularis and Ixodes pacificus (Brown and Lane, 1992; Kilpatrick et al., 2017). Notably, not all Ixodes spp. ticks are infected with the Borrelia spp. bacteria (Tokarz et al., 2019). Ixodes species that are infected can carry various genotypes of B. burgdorferi, which may contribute to heterogeneity in the clinical presentation of Lyme disease (Crowder et al., 2010; Lemieux et al., 2023; Tyler et al., 2018), and may carry multiple

___________________

1 There is controversy as to whether the existing Borrelia genus should be split into two genera: Borrelia and Borreliella (Winslow and Coburn, 2019). In the new classification, Lyme borreliosis-causing bacteria would fall into the latter. Given the unresolved controversy and historical association with Lyme disease and established literature, this report will use the Borrelia genus name throughout.

2 Borrelia burgdorferi sensu stricto will be referred to as simply as Borrelia burgdorferi or B. burgdorferi throughout this report.

3 Based on currently available epidemiology data, B. mayonii remains a rare cause of Lyme disease that appears to be limited to the upper Midwest. To date, eight cases of B. mayonii have been reported in the literature, and none have been associated with chronic sequelae (McGowan, 2023). Public health surveillance from Wisconsin and Minnesota have identified one to three cases each year since the pathogen was first identified in 2013 (Minnesota Department of Health, 2022; Wisconsin Department of Health Services, 2024). Reference to Borrelia spp. that cause Lyme disease throughout the report is based on data reported for B. burgdorferi unless otherwise specified. Furthermore, the report refers to findings, conclusions, and recommendations related to chronic sequelae associated with Lyme disease attributed to B. burgdorferi with the intention that they may also apply to Lyme IACI resulting from B. mayonii infections.

other pathogens that can cause human disease (e.g., Anaplasma phagocytophilum, Babesia spp., Borrelia miyamotoi, deer tick virus) (Caulfield and Pritt, 2015). Acknowledging the differences between Lyme disease outside of and originating in the United States, the committee focused its efforts primarily on reviewing the available evidence for B. burgdorferi sensu stricto while also considering important information from relevant non-U.S. studies when appropriate.

Lyme disease was first described in the United States in the late 1970s (Steere et al., 1977), the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention began surveillance of the disease by 1982, and it was designated as a nationally reportable disease in 1990 (Orloski et al., 2000). Despite the recognition of its public health importance and efforts to address its impact, the accuracy of the surveillance for Lyme disease continues to be challenged by several limitations in diagnosis and reporting.

Early Lyme disease often presents with a characteristic erythema migrans (EM) rash or lesion, which may be accompanied by general symptoms including fever, sweats and chills, headache, fatigue, muscle and joint pain, and swollen lymph nodes (Steere, 2001; Steere et al., 2003; Wormser, 2006). The presence of an EM can serve as a highly suggestive clinical diagnostic sign during early disease. In an endemic region, a clinical diagnosis may be made for individuals presenting with a characteristic EM and a possible tick exposure (Eldin et al., 2019; Lantos et al., 2021). However, 20–30 percent of people with Lyme disease who are seeking care may not present with a rash, and the EM lesion does not always appear in its typical form, leading to missed diagnoses and resulting in later manifestations such as Lyme arthritis, (Schwartz et al., 2017; Steere et al., 2003). When no EM is observed, diagnosis may be delayed or missed before the development of additional clinical symptoms or biomarkers (Lantos et al., 2021). Further complicating the clinical diagnosis, a similar rash is present in the southern tick-associated rash illness (STARI), which may follow bites by lone star ticks (Amblyomma americanum) but which is not caused by B. burgdorferi and not associated with Lyme IACI (Philipp et al., 2006; Wormser et al., 2005). While the geographic distribution of STARI and Lyme disease are generally separate, anthropogenic environmental changes have led to expansions in the range of these vectors that threaten to create increasing overlap between the two along the Atlantic coast and into the Midwestern states (Springer et al., 2015).

Laboratory evidence to support the diagnosis of infectious diseases can be categorized as direct or indirect detection. Direct detection assays determine the presence of a specific disease pathogen using methods such as detection of whole organisms (e.g., via culture or microscopy) or antigens or nucleic acids from the organism. Indirect detection assays measure different components of the host response to the pathogen or disease state (e.g., antibodies). While B. burgdorferi may be cultivated or detected by methods

such as poLymerase chain reaction, these methods are not sufficiently sensitive and reliable for clinical use. Other direct detection approaches, such as culturing bacteria from tissue biopsies, have also not yielded validated clinically assays, though readouts from a recent clinical trial for xenodiagnoses, a unique approach with proof-of-concept data, have not been released (Marques et al., 2014; NIAID, 2024). Support for the diagnosis of Lyme disease relies on testing for B. burgdorferi antibodies, an indirect diagnostic approach. Despite continued improvements to serologic assay methods, there are inherent limitations to serodiagnosis that affect clinical accuracy (see Glossary) (Branda and Steere, 2021). Because it takes a few weeks for the body to generate antibodies after infection, these tests have limited sensitivity during this early period of infection when people with EM typically seek medical evaluation. In addition, early antibiotic treatment may alter the kinetics and character of antibody response. People receiving antibiotics due to recognition of EM may produce overall lower levels of B. burgdorferi antibodies, may only produce antibodies against a limited repertoire of Borrelia antigens, and may have impeded IgM-to-IgG isotype switching. This may lead to false-negative serologic results during the acute clinical phase when the EM is apparent and occasionally even during the convalescent (post-treatment) phase of illness. Compared with individuals who received antibiotic treatment early in the disease course, those treated for late or disseminated Lyme disease typically mount a more robust antibody response and remain seropositive for longer despite a resolution of their symptoms. In such individuals the antibody response—even the IgM isotype—may persist, for up to 10–20 years after treatment. Thus, positive serologic tests, including for IgM, cannot reliably distinguish between a prior exposure to B. burgdorferi and an ongoing infection or determine the recency of an infection (Kalish et al., 2001). A number of active research efforts are underway to identify and develop new diagnostic approaches for Lyme disease, including detection of the host response through transcriptomics, proteomics, and metabolomics (Bockenstedt and Belperron, 2024; LymeX Innovation, 2025).

Treatment of Lyme Disease

Recommended antibiotic treatment for early Lyme disease typically includes the use of oral doxycycline or amoxicillin. For some patients with neurological involvement, intravenous ceftriaxone or oral doxycycline is recommended (Lantos et al., 2021). If untreated, early Lyme disease symptoms may resolve or may progress and later present with neurologic, cardiac, or joint involvement or some combination of the three (Steere et al., 2016). While neurologic or cardiac disease usually occurs relatively early in the course of Lyme disease, sometimes overlapping with the presence

of EM, Lyme arthritis typically occurs months to years after the untreated initial infection. Most people with either early or late Lyme disease recover after recommended antibiotic treatment, but a subset of individuals experience long-lasting and debilitating symptoms that may last months, years, or even decades.

Lyme Infection-Associated Chronic Illnesses

The estimated prevalence of Lyme IACI varies widely. It is challenging to estimate how many people are living with Lyme IACI without a consensus case definition for the syndrome, especially given the subjective symptoms that overlap with those of similar conditions. The commonly referenced estimate of the proportion of individuals experiencing protracted symptoms after standard antibiotic treatment of Lyme disease is 10–20 percent, a range that was drawn from prospective studies where the reported prevalence ranges from 0 to 36 percent (Aucott, 2013b; Aucott et al., 2022; Weitzner 2015; Wormser et al., 2020). On the other hand, 61 percent of participants in the MyLymeData patient registry self-reported as having chronic Lyme disease (Johnson, 2019).4 The wide range in prevalence estimated from the aforementioned studies and the patient may be attributed to a few reasons, including the inherent difference between the participants captured by prospective cohort studies and those from a retrospectively surveyed, patient-driven disease registry. For the pediatric population, one publication suggests that some children and adolescents experience persistent symptoms, but this was a retrospective survey study, and prospective studies are needed to further examine the prevalence in this population (Monaghan et al., 2024). Data from these studies are discussed in more detail in Chapter 2.

The most common long-term, unrelenting post-treatment symptoms that patients have reported include persistent fatigue, cognitive issues (so-called “brain fog,” which includes difficulties with concentration, memory, and word finding), sleep quality disturbances, and recurring pain, which may include headache, joint pain, and other musculoskeletal pain.5 Mood disturbances and orthostatic intolerance, which may be related to postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome (POTS) or other forms of autonomic dysfunction, have also been observed (Rebman and Aucott, 2020). All of these symptoms may occur alone or in combination and may fluctuate in intensity over time. For example, one randomized trial of individuals with

___________________

4 LymeDisease.org, the home organization of the MyLymeData registry, defines “chronic Lyme disease” as remaining ill for ≥ 6 months after treatment with antibiotics for 10–21 days.

5 Other symptoms have been reported in the MyLymeData patient registry and in peer-reviewed studies.

Lyme IACI found that commonly reported symptoms at baseline ranged in prevalence from less than half of individuals experiencing headache or dysesthesia (painful or burning sensation) to as high as 92 percent for arthralgia or myalgia (Klempner et al., 2001).

Controversy and disagreement remain over the terminology used to describe the collection of these debilitating symptoms. The terms “chronic Lyme disease” and “persistent Lyme disease,” which are adapted and preferred by various organizations, have evolved to take on implications of disease etiology, for which there is no scientific consensus (i.e., unsupported implications that chronic or persistent B. burgdorferi infection is the cause of these symptoms). Individuals experiencing persistent and debilitating symptoms may be characterized as having post-treatment Lyme disease syndrome (PTLDS) (Aucott et al., 2013a; Wormser et al., 2006). Developed for research purposes, PTLDS requires a well-documented diagnosis of Lyme disease, a set of subjective symptoms based on patient reports, and significant impact of the symptoms on daily activities for 6 or more months after completing recommended treatment for Lyme disease (see Chapter 2). There are clear advantages to having a precise definition of the study population in conducting research. The trade-off for this stringency is the exclusion of people with these symptoms who may not have clinical or serologic evidence to meet the PTLDS criteria but whose conditions still need understanding and treatment (Aucott et al., 2012, 2013a; Rebman and Aucott, 2020).

The recognition of Long COVID as “an infection-associated chronic condition that occurs after SARS-CoV-2 infection” (NASEM, 2024a) has focused attention on the legitimacy and importance of post-acute infection syndromes that have been documented following a number of viral, bacterial, and parasitic diseases (Choutka et al., 2022). In 2023, the National Academies held a public workshop on advancing a common research agenda for these post-infection syndromes, referred to as “infection-associated chronic illnesses” (NASEM, 2024b). Following the increasing acceptance and use of the terms “infection-associated chronic illnesses (or conditions)”6 to describe persistent symptoms with a potential infectious trigger, the committee adapted “Lyme IACI” as an umbrella term to, for the purposes of this study, encompass the broad group of illnesses that have been previously described under a variety of terminologies, including PTLDS, chronic Lyme disease, persistent Lyme disease, and others. As with Long COVID, the use of this term affirms the authenticity and impacts of the symptoms experienced by people but does not carry any proven implications with respect to disease etiology or pathogenesis.

___________________

6 See Key Terms below.

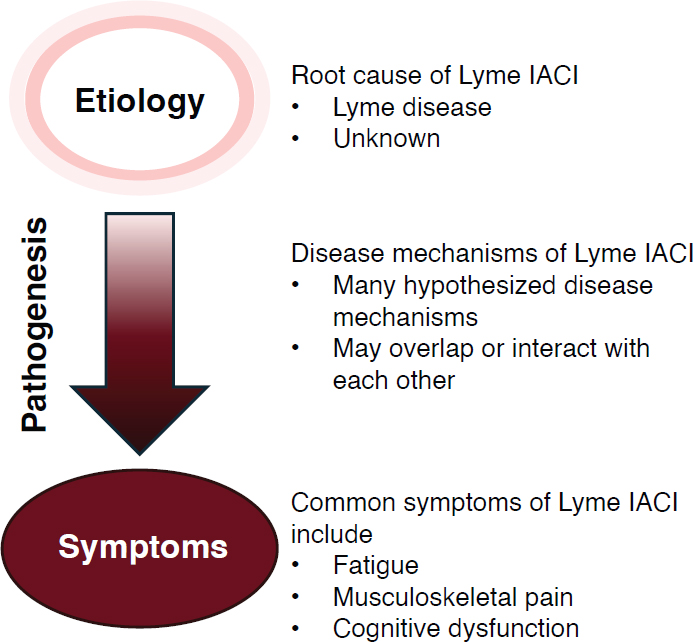

Unlike the case for Long COVID, a working definition of Lyme IACI has not yet been established, and this committee was not charged with defining the condition (Box 1-2). However, the committee has been asked to examine the current knowledge on the etiology and clinical trials for treatment of Lyme IACI. In the absence of a consensus definition of Lyme IACI, the committee developed an operational scope for the limited purpose of conducting the necessary literature review (Box 1-3). As with Long COVID and other infection-associated chronic illnesses, a full understanding of the pathogenesis of Lyme IACI remains elusive, and hypothesized disease mechanisms have ranged from the persistence of pathogens or antigens to host responses such as microbiome alterations, autoimmunity, or other immune dysregulation (Bobe et al., 2021; Marques et al., 2021). Similarly, while there are diagnostic procedures to detect the initial infection (i.e., B. burgdorferi infection in the case of Lyme IACI), there are currently no known or validated objective biomarkers, clinical examinations, or laboratory findings to define or diagnose Lyme IACI, monitor treatment

response, or indicate cure. No prognostic factors have been consistently shown to predict the risk of developing Lyme IACI after the initial disease, and no validated treatments are available, though research remains ongoing for future diagnosis and therapeutic options. Objective indicators and diagnostic procedures for Lyme IACI may yet be identified in the future, as exploratory research has reported potentially promising findings. Chapter 2 summarizes the committee’s review of the existing evidence from published literature on Lyme IACI etiology, diagnosis, and treatment.

Impact of Disease

It is clear that Lyme IACI, even when limited to the minority of individuals who meet the criteria for PTLDS, have significant health and economic impacts on society. Based on the current estimates of prevalence from prospective observational studies, tens of thousands of people may develop Lyme IACI in the United States each year,7 while a simulation model that assumes linear growth of Lyme disease diagnosis from year to year suggests that a cumulative count of nearly 2 million people in the United States may have experienced PTLDS at some point in their lifetime between 1980 and 2020 (DeLong et al., 2019). In Europe, cumulative or societal cost-of-illness has been reported to be over 170 million euros for PTLDS in Belgium and between 5.2 million and 6.3 million euros for persistent symptoms related to Lyme disease in the Netherlands (approximately 27 percent of the 19.3–23.5 million euro total societal cost associated with Lyme disease) (van den Wijngaard et al., 2017; Willems et al., 2023). While there have not been

___________________

7 Calculated based on the average estimated prevalence of PTLDS following Lyme disease diagnosis from the studies discussed earlier in the chapter (range between 14–20 percent depending on interpretation of Wormser et al., 2020) and the currently reported annual prevalence of Lyme disease of 476,000.

specific attempts to estimate the financial costs of Lyme IACI in the United States, the aggregated cost-of-illness for Lyme disease in the United States was estimated to range from $345 million to over $900 million dollars each year (in 2016) and projected to continue increasing (Hook et al., 2022).

Without specific diagnostic tools for Lyme IACI, patients and care providers rely on symptom reports coupled with diagnostics for the initial Borrelia spp. infection, some of which may be derived from methods or facilities whose performance has not been validated (Fallon et al., 2014; Waddell et al., 2016). The lack of diagnostic tools and the subjective nature of the persistent symptoms have often led to stigmatization and dismissal of people living with Lyme IACI by the health care system, as these individuals and their illnesses do not match well-established disease narratives besides “medically unexplained symptoms” (Ali et al., 2014). As with other complex chronic conditions of unclear cause (e.g., Long COVID), and absent well-documented effective interventions, the U.S. medical system is not geared to provide effective longitudinal—and perhaps multidisciplinary—care and support for these people.

Studies have shown that patient suffering is high, with health-related quality of life being lower compared with control populations and with individuals with some other chronic diseases (Johnson et al., 2014; Rebman et al., 2017). Further, depression rates in this group of patients are estimated as being between 8 and 45 percent, and these individuals are at increased risk for suicide (Doshi et al., 2018; Fallon et al., 2021). A study of individuals diagnosed with PTLDS found that they exhibited an increased prevalence of depression and sleep disturbance compared to healthy controls (Rebman et al., 2017). In another study of individuals reporting persistent symptoms after diagnosis and treatment of Lyme disease, this group was more likely to report concentration problems and receive a diagnosis of major depressive disorder and generalized anxiety disorder when compared to healthy controls and controls with other chronic conditions (Hassett et al., 2008).

Due to the physical and mental toll of living with Lyme IACI and the lack of available treatments, people living with Lyme IACI are in urgent need for therapies to alleviate their symptoms, improve quality of life, or cure the underlying disease state. As there are no therapies demonstrated to be safe and effective through clinical research, patients and their treating clinicians seek out approaches or treatments that are deemed to have the potential to address their symptoms based on clinical experience or experience in illnesses with similar symptoms. Since these treatments are not approved for this condition, patients often have to pay out of pocket for expensive care and treatments of unknown safety and effectiveness (Box 1-4). Among patients diagnosed with Lyme disease, those subsequently diagnosed with PTLDS-related conditions were found to have medical

costs that were nearly twice that of patients with Lyme disease but without persistent symptoms (Adrion et al., 2015).8 Up to half of the illness-related costs are borne out-of-pocket, as people living with Lyme IACI often sought complementary therapies to alleviate their symptoms that have not been

___________________

8 Since there is no standard clinical definition or medical record coding for PTLDS, this study used International Classifications of Diseases codes corresponding to symptoms covered under PTLDS and referred to these as “PTLDS-related conditions.” These include debility and undue fatigue, musculoskeletal signs and symptoms, peripheral neuropathy or neuritis, arthropathy, and nonspecific signs and symptoms.

validated in clinical research for Lyme IACI. The financial burden might be even higher for those without insurance, as the majority of participants in available studies had health insurance coverage (70 percent in Hook et al., 2022, and 100 percent in Adrion et al., 2015).

A robust patient community has developed to share resources and information, often based on their individual experiences navigating the medical system and trying various therapies. However, given the nature of protracted symptoms experienced by people living with Lyme IACI and the paucity of efficacious treatments supported by evidence generated through clinical studies, profiteering entities have also emerged to exploit this prolonged unmet needs by promoting products and procedures that are costly, may not work, and may cause harm (Sakizadeh et al., 2025).

Context of Other Infection-Associated Chronic Illnesses

Shortly after the start of the COVID-19 pandemic, some individuals started reporting persisting, often long-term, symptoms after acute SARSCoV-2 infection. This condition is now named Long COVID. The large scale of the COVID-19 pandemic has raised awareness in the medical and scientific world, as well as for the public, that acute infections can trigger chronic illness.

However, chronic illness after infections has been described for decades. Various viral pathogens have been associated with IACI, including not just SARS-CoV-2 but Ebola virus, dengue viruses, poliovirus, chikungunya virus, Epstein-Barr virus, enteroviruses, and West Nile virus as well as several non-viral pathogens, including Coxiella burnetti (the bacterial causative agent of Q fever) and Giardia lamblia (the protozoan causative agent of giardiasis) (Choutka et al., 2022). Also described as “post-acute infection syndromes,” these conditions are generally characterized by chronic, nonspecific symptoms that remain or develop following an acute infection and typically lack objective markers to aid in diagnosis. The committee uses the term “IACI” throughout this report to refer to chronic illnesses with a potential infectious trigger and encompass some conditions, like myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome (ME/CFS) or fibromyalgia, where the etiology remains unknown but have been documented to include infectious triggers (Hickie et al., 2006; Magnus et al., 2015; Hanson, 2023). ME/CFS is referenced throughout this report, although the committee does not intend to imply that infections are the only root cause of ME/CFS.

A clear overlap in symptoms can be identified among many IACI, including ME/CFS, Long COVID, and Lyme IACI (Bai and Richardson, 2023; Komaroff and Lipkin, 2023). The symptoms described in the literature that overlap for Lyme IACI, ME/CFS, and Long COVID include

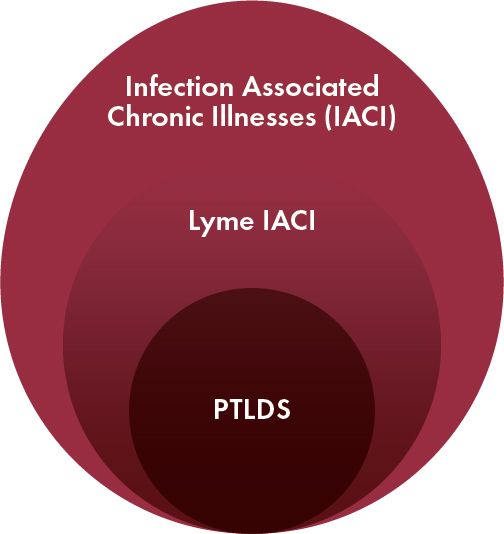

fatigue, musculoskeletal pain, sleep disorders, and cognitive issues.9 There are some symptoms associated frequently with ME/CFS but rarely in the other two conditions (painful lymph nodes, chemical sensitivities, and tinnitus) and others that are associated primarily with Long COVID but not ME/CFS or Lyme IACI (e.g., decreased smell and taste, rash, and hair loss) (Komaroff and Lipkin, 2023). However, the overlapping symptoms (fatigue, pain, cognitive dysfunction) are also the ones most commonly reported by those with Lyme IACI. The degree to which these symptoms overlap with other similar conditions, along with the lack of specific biomarkers for each condition, makes it difficult to diagnose the root cause of an individual’s symptoms, particularly with the near ubiquitous exposure to SARS-CoV-2 (Figure 1-1; see Chapter 3).

In addition to the similarities in symptoms and hypothesized underlying disease mechanisms, people living with these illnesses also often share the common experience of not being believed to be ill if diagnostic testing for general disease biomarkers are not able to substantiate the real, even if subjective, symptoms that they have. Taken together, Lyme IACI and at least two other similar conditions, Long COVID and ME/CFS, are connected in the lack of understanding by health care practitioners, the lack of effective interventions, and the marginalization and suffering of people living with these illnesses.

COMMITTEE APPROACH

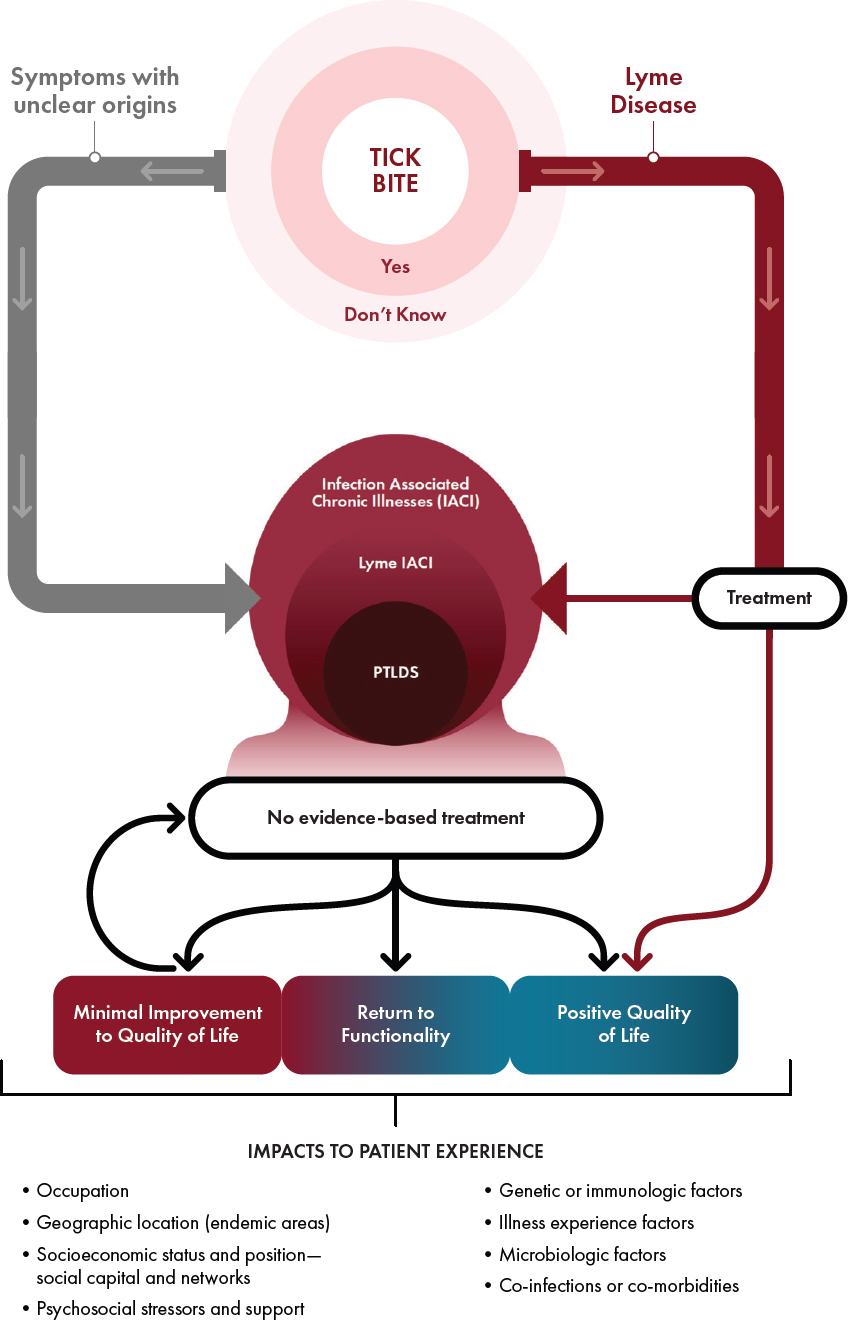

To reinforce a person-centered conceptualization of the nuanced and multifactorial components of Lyme disease and the development of Lyme IACI, the committee developed a conceptual framework to visualize the various elements and their potential interactions in the development and treatment of Lyme IACI. This conceptual framework (Figure 1-2) specifically highlights the individual factors that may affect one’s ability to navigate their illness trajectory. The framework does not purport to encompass a universal experience and instead serves as a general outline of the factors surrounding the development and experience of Lyme IACI.

Committee’s Interpretation of the Task and Approach

While the prevention of Lyme disease is the most straightforward way to reduce the burden of Lyme IACI, effective prevention likely requires sustained education initiatives directed at the public and clinicians, which are outside the purview of this committee but has been addressed in other

___________________

9 Post-exertional malaise is reported by some as a symptom of Lyme IACI but has not been evaluated separately from measures of fatigue in studies on Lyme IACI.

NOTES: The largest oval includes individuals with syndromes likely triggered by non-Lyme infections, including Long COVID, and other chronic conditions such as ME/CFS with potential infectious triggers, known and unknown. The two embedded ovals indicate a subset that includes people with a possible diagnosis of Lyme IACI (i.e., not meeting the criteria for PTLDS and may have a Lyme-related IACI or may have illness triggered by non-Lyme factors) and, within that group, those with well-documented prior B. burgdorferi infection (i.e., meeting criteria for PTLDS) and others. The blurring between Lyme IACI and larger IACI ovals represents the challenges in distinguishing etiology between the groups, given both uncertainties in diagnosis of Lyme IACI and the widespread presence of other IACI, including Long COVID. This figure is a general depiction of the relationship between the three populations and the difficulty in distinguishing between them.

NOTES: Not all individuals who are bitten by ticks will develop Lyme disease, and not all individuals with Lyme disease will develop Lyme IACI. This figure is focused on the trajectories and experiences of individuals with Lyme IACI. Scenarios in which Lyme IACI is absent are not depicted. IACI = infection-associated chronic illnesses; PTLDS = post-treatment Lyme disease syndrome.

reports (TBDWG, 2018, 2020). Preventive measures, including post-tick bite prophylaxis to prevent development of Lyme disease or progression to Lyme IACI, were also not considered to be within scope for this study. Clinical care and management guidelines or recommendations, explored in the aforementioned reports, do not fall within the committee’s charge to examine current scientific evidence and research priorities to advance new treatments. Identifying new treatments that are ready for clinical use and evaluating their integration into the practice of evidence-based medicine are also beyond the scope of this report. The focus of this report is on generation of research evidence on Lyme IACI treatments, which is part of an evidence-based medicine framework, but the other components of this framework (patient values and clinician judgment in the context of clinical decisions) are not within the charge to this committee.

In examining the evidence base, the committee determined that the study would focus on persistent symptoms associated with prior Lyme disease in the United States, while acknowledging that there may be findings from research in Europe that could inform the committee’s task. The committee decided that general findings from studies based in Europe that are relevant to the committee’s review could be incorporated into the report. The committee also interpreted the scope of literature review on treatments to include both curative interventions, if any are reported, and those that manage or improve symptoms, while excluding publications that solely comment on the provision of care. Similarly, the committee decided that while the report might include consideration of medical ethics in conducting future research, the role of medical ethics in clinical practice was out of scope for this study. The committee focused its efforts on the examining the uncertainties and knowledge gaps in the current evidence base, interpreted as limited to biomedical and clinical research. Aspects of implementation research (e.g., economics, health systems, or disability research) were considered out of scope for this study. Given that the overarching focus of the study is on treatments for Lyme IACI, the committee interpreted the statement of task (Box 1-1) such that the examination of diagnostics and etiology literature would be framed through its role in advancing new treatments that benefit people who are living with these chronic symptoms. Accordingly, the committee focused its literature search on the pathogenic mechanisms of Lyme IACI (Figure 1-3).

The committee also focused on Long COVID and ME/CFS as two conditions with similar symptoms and potential infectious triggers and, given the significant research efforts and available literature, as a basis for expanding the literature review for lessons learned that could inform future Lyme IACI research. However, the committee focused its efforts on identifying recommendations for future Lyme IACI research rather than on conducting an exhaustive review of the existing literature for Long COVID, ME/CFS, and other similar conditions.

NOTES: IACI = infection-associated chronic illnesses.

To address its task, the committee held three public, in-person or virtual information-gathering sessions with invited presentations from researchers, technology developers, regulators, people living with Lyme IACI, and patient-led research organizations. One hybrid (in-person and virtual) information-gathering session, held on July 11, 2024, was a public workshop, Research for Lyme Infection-Associated Chronic Illnesses Treatment: Broadening the Lens. Over the course of the study, the committee met eight times in closed session. Agendas for these meetings can be found in Appendix A.

In addition, the committee conducted a scoping review of the literature on the mechanisms, treatment, and diagnosis of Lyme IACI to gain insight into the research that has been conducted in understanding these aspects of the disease state and to identify potential knowledge gaps. While it was not within the scope of the study to put forth a consensus definition for Lyme IACI, the committee broadly considered Lyme IACI to be a condition in which an individual has persistent symptoms following Lyme disease with or without a prior Lyme disease diagnosis (see Chapter 2 for details). A detailed protocol and methodology for the scoping review is provided in Appendix C. The committee also commissioned a paper on potential artificial intelligence applications in Lyme IACI. The findings from that paper are summarized in Chapter 4.

Based on the evidence reviewed, the committee did not attempt to identify or rank specific treatments as future research priorities. However, key actions that need to be taken to advance Lyme IACI research were identified, and a framework to help enable stakeholders to assess and prioritize potential candidate interventions is presented.

Key Terms

A glossary of common scientific terminology that is used throughout the report is provided at the beginning of this report. The committee also considered and used additional key terms that the committee describes for the purposes of this report, which are detailed below.

Different terms have been used to describe the population or subpopulations living with nonspecific chronic symptoms associated with Lyme disease that share some similarities with other conditions. Some of these terms include long Lyme, chronic Lyme disease, persistent Lyme disease, and PTLDS. This study has adopted “Lyme infection-associated chronic illnesses” (Lyme IACI) to encompass these different terms. Coined at the June 2023 National Academies workshop (NASEM, 2024b), “infection-associated chronic illnesses” are characterized by similar sets of persistent, multisystem symptoms that may share common pathophysiology. This report refers to ME/CFS and Long COVID as part of this group of infection-associated chronic illnesses.

Alternatively, a related term, “infection-associated chronic conditions,” has been used, sometimes interchangeably with IACI, in the emerging research literature. In health care and medicine, the term “condition” often refers to a diagnosable, billable, or defined state of health (e.g., the International Classification of Diseases [ICD] is a catalog of codes for health conditions that is widely used for health records and medical billing). Thus, use of the term may inadvertently exclude infection-associated chronic syndromes that currently do not have a diagnostic test or definition and may not yet be included in coding systems for payers. To avoid this unintended exclusion, this report uses the term “illnesses” to recognize these collections of infection-associated chronic syndromes. In some instances, the report also applies the colloquial use of the term “diseases” to describe IACI.

The committee recognizes that a consensus definition for Lyme IACI does not exist. For the literature review, the committee described an intentionally inclusive operational scope of this condition to address the broader need for treatment and research, regardless of the certainty with which symptoms can be attributed to Lyme disease. Differences in patient subgroups—and the potential for resulting differences in response to therapies—can be subsequently addressed through appropriate stratification in research.

Organization of the Report

This report is divided into five chapters. Chapter 2 discusses the current evidence base on Lyme IACI, including its prevalence, treatment, mechanisms, and diagnosis. The chapter culminates with key research questions that require investigation to address the gaps in the evidence base. Chapter 3 draws on insights gleaned from research on conditions similar to Lyme IACI, such as Long COVID and ME/CFS, and assesses how lessons learned from these conditions could be used in Lyme IACI research. In Chapter 4, the committee proposes a framework to prioritize Lyme IACI treatment candidates for clinical research and highlights approaches to research infrastructure, data interpretation, and research implementation that can improve the efficiency of future Lyme IACI research. The report concludes with the committee’s six recommendations, which are described in Chapter 5.

REFERENCES

Adrion, E. R., J. Aucott, K. W. Lemke, and J. P. Weiner. 2015. Health care costs, utilization and patterns of care following Lyme disease. PLOS One 2(10):e0116767.

Ali, A., L. Vitulano, R. Lee, T. R. Weiss, and E. R. Colson. 2014. Experiences of patients identifying with chronic Lyme disease in the healthcare system: A qualitative study. BMC Family Practice 15(1):79.

Aucott, J. N., A. Seifter, and A. W. Rebman. 2012. Probable late Lyme disease: A variant manifestation of untreated Borrelia burgdorferi infection. BMC Infectious Diseases 12(1):173.

Aucott, J. N., L. A. Crowder, and K. B. Kortte. 2013a. Development of a foundation for a case definition of post-treatment Lyme disease syndrome. International Journal of Infectious Diseases 17(6):e443–e449.

Aucott, J. N., A. W. Rebman, L. A. Crowder, and K. B. Kortte. 2013b. Post-treatment Lyme disease syndrome symptomatology and the impact on life functioning: Is there something here? Quality of Life Research 22(1):75–84.

Aucott, J. N., T. Yang, I. Yoon, D. Powell, S. A. Geller, and A. W. Rebman. 2022. Risk of posttreatment Lyme disease in patients with ideally-treated early Lyme disease: A prospective cohort study. International Journal of Infectious Diseases 116:230–237.

Bai, N. A., and C. S. Richardson. 2023. Posttreatment Lyme disease syndrome and myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome: A systematic review and comparison of pathogenesis. Chronic Diseases and Translational Medicine 9(3):183–190.

Bockenstedt, L. K., and A. A. Belperron. 2024. Insights from omics in Lyme disease. Journal of Infectious Disease 230(Supplement_1):S18-s26.

Bobe, J. R., B. L. Jutras, E. J. Horn, M. E. Embers, A. Bailey, R. L. Moritz, Y. Zhang, M. J. Soloski, R. S. Ostfeld, R. T. Marconi, J. Aucott, A. Ma’ayan, F. Keesing, K. Lewis, C. Ben Mamoun, A. W. Rebman, M. E. McClune, E. B. Breitschwerdt, P. J. Reddy, R. Maggi, F. Yang, B. Nemser, A. Ozcan, O. Garner, D. Di Carlo, Z. Ballard, H. A. Joung, A. Garcia-Romeu, R. R. Griffiths, N. Baumgarth, and B. A. Fallon. 2021. Recent progress in Lyme disease and remaining challenges. Frontiers in Medicine (Lausanne) 8:666554.

Branda, J. A., and A. C. Steere. 2021. Laboratory diagnosis of Lyme borreliosis. Clinical Microbiology Reviews 34(2):e00018-19.

Brown, R. N., and R. S. Lane. 1992. Lyme disease in California: A novel enzootic transmission cycle of Borrelia burgdorferi. Science 256(5062):1439–1442.

Caulfield, A. J., and B. S. Pritt. 2015. Lyme disease coinfections in the United States. Clinics in Laboratory Medicine 35(4):827–846.

Choutka, J., V. Jansari, M. Hornig, and A. Iwasaki. 2022. Unexplained post-acute infection syndromes. Nature Medicine 28(5):911–923.

Crowder, C. D., H. E. Matthews, S. Schutzer, M. A. Rounds, B. J. Luft, O. Nolte, S. R. Campbell, C. A. Phillipson, F. Li, R. Sampath, D. J. Ecker, and M. W. Eshoo. 2010. Genotypic variation and mixtures of Lyme Borrelia in Ixodes ticks from North America and Europe. PLOS One 5(5):e10650.

DeLong, A., M. Hsu, and H. Kotsoris. 2019. Estimation of cumulative number of posttreatment Lyme disease cases in the U.S., 2016 and 2020. BMC Public Health 19(1):352.

Doshi, S., J. G. Keilp, B. Strobino, M. McElhiney, J. Rabkin, and B. A. Fallon. 2018. Depressive symptoms and suicidal ideation among symptomatic patients with a history of Lyme disease vs. two comparison groups. Psychosomatics 59(5):481–489.

Eldin, C., A. Raffetin, K. Bouiller, Y. Hansmann, F. Roblot, D. Raoult, and P. Parola. 2019. Review of European and American guidelines for the diagnosis of Lyme borreliosis. Médecine et Malaladies Infectieuses 49(2):121–132.

Fallon, B. A., M. Pavlicova, S. W. Coffino, and C. Brenner. 2014. A comparison of Lyme disease serologic test results from 4 laboratories in patients with persistent symptoms after antibiotic treatment. Clinical Infectious Diseases 59(12):1705–1710.

Fallon, B. A., T. Madsen, A. Erlangsen, and M. E. Benros. 2021. Lyme borreliosis and associations with mental disorders and suicidal behavior: A nationwide Danish cohort study. American Journal of Psychiatry 178(10):921–931.

Hanson, M. R. 2023. The viral origin of myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome. PLoS Pathogen 19(8):e1011523.

Hassett, A. L., D. C. Radvanski, S. Buyske, S. V. Savage, M. Gara, J. I. Escobar, and L. H. Sigal. 2008. Role of psychiatric comorbidity in chronic Lyme disease. Arthritis Rheumatism 59(12):1742-1749.

Hickie I., T. Davenport, D. Wakefield, U. Vollmer-Conna, B. Cameron, S. D. Vernon, W. C. Reeves, A. Lloyd, and Dubbo Infection Outcomes Study Group. 2006. Post-infective and chronic fatigue syndromes precipitated by viral and non-viral pathogens: prospective cohort study. BMJ 16;333(7568):575.

Hook, S. A., S. Jeon, S. A. Niesobecki, A. P. Hansen, J. I. Meek, J. K. H. Bjork, F. M. Dorr, H. J. Rutz, K. A. Feldman, J. L. White, P. B. Backenson, M. B. Shankar, M. I. Meltzer, and A. F. Hinckley. 2022. Economic burden of reported Lyme disease in high-incidence areas, United States, 2014–2016. Emerging Infectious Diseases 28(6):1170–1179.

Johnson, L. 2019. MyLymeData 2019 chart book: figshare. https://figshare.com/articles/book/MyLymeData_2019_Chart_Book/8063039/1?file=17413562 (accessed February 1, 2025).

Johnson, L., S. Wilcox, J. Mankoff, and R. B. Stricker. 2014. Severity of chronic Lyme disease compared to other chronic conditions: A quality of life survey. PeerJ 2:e322.

Kalish, R. A., G. McHugh, J. Granquist, B. Shea, R. Ruthazer, and A. C. Steere. 2001. Persistence of immunoglobulin M or immunoglobulin G antibody responses to Borrelia burgdorferi 10–20 years after active Lyme disease. Clinical Infectious Diseases 33(6):780–785.

Kilpatrick, A. M., A. D. M. Dobson, T. Levi, D. J. Salkeld, A. Swei, H. S. Ginsberg, A. Kjemtrup, K. A. Padgett, P. M. Jensen, D. Fish, N. H. Ogden, and M. A. Diuk-Wasser. 2017. Lyme disease ecology in a changing world: Consensus, uncertainty and critical gaps for improving control. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 372(1722):20160117.

Klempner, M. S., L. T. Hu, J. Evans, C. H. Schmid, G. M. Johnson, R. P. Trevino, D. Norton, L. Levy, D. Wall, J. McCall, M. Kosinski, and A. Weinstein. 2001. Two controlled trials of antibiotic treatment in patients with persistent symptoms and a history of Lyme disease. New England Journal of Medicine 345(2):85–92.

Komaroff, A. L., and W. I. Lipkin. 2023. ME/CFS and Long COVID share similar symptoms and biological abnormalities: Road map to the literature. Frontiers in Medicine (Lausanne) 10:1187163.

Kugeler, K. J., A. M. Schwartz, M. J. Delorey, P. S. Mead, and A. F. Hinckley. 2021. Estimating the frequency of Lyme disease diagnoses, United States, 2010–2018. Emerging Infectious Diseases 27(2):616–619.

Lantos, P. M., J. Rumbaugh, L. K. Bockenstedt, Y. T. Falck-Ytter, M. E. Aguero-Rosenfeld, P. G. Auwaerter, K. Baldwin, R. R. Bannuru, K. K. Belani, W. R. Bowie, J. A. Branda, D. B. Clifford, F. J. DiMario, J. J. Halperin, P. J. Krause, V. Lavergne, M. H. Liang, H. C. Meissner, L. E. Nigrovic, J. J. J. Nocton, M. C. Osani, A. A. Pruitt, J. Rips, L. E. Rosenfeld, M. L. Savoy, S. K. Sood, A. C. Steere, F. Strle, R. Sundel, J. Tsao, E. E. Vaysbrot, G. P. Wormser, and L. S. Zemel. 2021. Clinical practice guidelines by the Infectious Diseases Society of America, American Academy of Neurology, and American College of Rheumatology: 2020 guidelines for the prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of Lyme disease. Neurology 96(6):262–273.

Lemieux, J. E., W. Huang, N. Hill, T. Cerar, L. Freimark, S. Hernandez, M. Luban, V. Maraspin, P. Bogovic, K. Ogrinc, E. Ruzic-Sabljic, P. Lapierre, E. Lasek-Nesselquist, N. Singh, R. Iyer, D. Liveris, K. D. Reed, J. M. Leong, J. A. Branda, A. C. Steere, G. P. Wormser, F. Strle, P. C. Sabeti, I. Schwartz, and K. Strle. 2023. Whole genome sequencing of Borrelia burgdorferi isolates reveals linked clusters of plasmid-borne accessory genome elements associated with virulence. bioRxiv [Preprint]. Feb 27:2023.02.26.530159. Update in: PLOS Pathogens, 2023, 19(8):e1011243.

LymeX Innovation. 2025. Announcing the phase 3 winners. https://www.Lymexdiagnostic-sprize.com/announcing-the-phase-3-winners/ (accessed March 14, 2025).

Magnus, P., N. Gunnes, K. Tveito, I. J. Bakken, S. Ghaderi, C. Stoltenberg, M. Hornig, W. I. Lipkin, L. Trogstad, and S. E. Håberg. 2015. Chronic fatigue syndrome/myalgic encephalomyelitis (CFS/ME) is associated with pandemic influenza infection, but not with an adjuvanted pandemic influenza vaccine. Vaccine 17;33(46):6173-6177.

Marques, A., S. R. Telford, 3rd, S. P. Turk, E. Chung, C. Williams, K. Dardick, P. J. Krause, C. Brandeburg, C. D. Crowder, H. E. Carolan, M. W. Eshoo, P. A. Shaw, and L. T. Hu. 2014. Xenodiagnosis to detect Borrelia burgdorferi infection: A first-in-human study. Clinical Infectious Diseases 58(7):937–945.

Marques, A. R., F. Strle, and G. P. Wormser. 2021. Comparison of Lyme disease in the United States and Europe. Emerging Infectious Diseases 27(8):2017–2024.

McGowan, M. S., T. M. Kalinoski, and S. E. Hesse. 2023. Acute Lyme disease with atypical features due to Borrelia mayonii. Open Forum Infectious Diseases 10(11):ofad524.

Minnesota Department of Health. 2022. Borrelia mayonii disease statistics https://www.health.state.mn.us/diseases/bmayonii/statistics.html (accessed January 27, 2025).

Monaghan, M., S. Norman, M. Gierdalski, A. Marques, J. E. Bost, and R. L. DeBiasi. 2024. Pediatric Lyme disease: Systematic assessment of post-treatment symptoms and quality of life. Pediatric Research 95(1):174–181.

NASEM (National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine). 2024a. A Long COVID definition: A chronic, systemic disease state with profound consequences. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

NASEM. 2024b. Toward a common research agenda in infection-associated chronic illnesses: Proceedings of a workshop. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

Nelson, C. A., S. Saha, K. J. Kugeler, M. J. Delorey, M. B. Shankar, A. F. Hinckley, and P. S. Mead. 2015. Incidence of clinician-diagnosed Lyme disease, United States, 2005–2010. Emerging Infectious Diseases 21(9):1625–1631.

NIAID (National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases. 2024. Xenodiagnosis after antibiotic treatment for Lyme disease. https://www.clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT02446626 (accessed January 27, 2025).

Orloski, K. A., E. B. Hayes, G. L. Campbell, and D. T. Dennis. 2000. Surveillance for Lyme disease—United States, 1992-1998. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report 49(SS03):1-11.

Philipp, M. T., E. Masters, G. P. Wormser, W. Hogrefe, and D. Martin. 2006. Serologic evaluation of patients from Missouri with erythema migrans-like skin lesions with the C6 Lyme test. Clinical and Vaccine Immunolology 13(10):1170–1171.

Rebman, A. W., K. T. Bechtold, T. Yang, E. A. Mihm, M. J. Soloski, C. B. Novak, and J. N. Aucott. 2017. The clinical, symptom, and quality-of-life characterization of a well-defined group of patients with posttreatment Lyme disease syndrome. Frontiers in Medicine (Lausanne) 4:224.

Rebman, A. W., and J. N. Aucott. 2020. Post-treatment Lyme disease as a model for persistent symptoms in Lyme disease. Frontiers in Medicine (Lausanne) 7:57.

Rosenberg, R., N. P. Lindsey, M. Fischer, C. J. Gregory, A. F. Hinckley, P. S. Mead, G. Paz-Bailey, S. H. Waterman, N. A. Drexler, G. J. Kersh, H. Hooks, S. K. Partridge, S. N. Visser, and C. B. Beard. 2018. Vital signs: Trends in reported vectorborne disease cases — United States and territories, 2004–2016. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report 67(17):496-501.

Sakizadeh, J. R., M. K. Rothenberger, and J. D. Alpern. 2025. Characteristics of clinics offering nontraditional Lyme disease therapies in Lyme endemic states of the United States. Open Forum Infectious Diseases 12(3).

Schwartz, A. M., A. F. Hinckley, P. S. Mead, S. A. Hook, and K. J. Kugeler. 2017. Surveillance for Lyme disease—United States, 2008–2015. MMWR Surveillance Summaries 66(22):1–12.

Springer, Y. P., C. S. Jarnevich, D. T. Barnett, A. J. Monaghan, and R. J. Eisen. 2015. Modeling the present and future geographic distribution of the Lone Star tick, Amblyomma americanum (Ixodida: Ixodidae), in the Continental United States. American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene 93(4):875–890.

Steere, A. C. 2001. Lyme disease. New England Journal of Medicine 345(2):115–125.

Steere, A. C., S. E. Malawista, D. R. Snydman, R. E. Shope, W. A. Andiman, M. R. Ross, and F. M. Steele. 1977. Lyme arthritis: An epidemic of oligoarticular arthritis in children and adults in three Connecticut communities. Arthritis & Rheumatology 20(1):7–17.

Steere, A. C., A. Dhar, J. Hernandez, P. A. Fischer, V. K. Sikand, R. T. Schoen, J. Nowakowski, G. McHugh, and D. H. Persing. 2003. Systemic symptoms without erythema migrans as the presenting picture of early Lyme disease. American Journal of Medicine 114(1):58–62.

Steere, A. C., F. Strle, G. P. Wormser, L. T. Hu, J. A. Branda, J. W. R. Hovius, X. Li, and P. S. Mead. 2016. Lyme borreliosis. Nature Reviews Disease Primers 2(1):16090.

Stone, B. L., Y. Tourand, and C. A. Brissette. 2017. Brave new worlds: The expanding universe of Lyme disease. Vector Borne Zoonotic Diseases 17(9):619–629.

TBDWG (Tick-Borne Disease Working Group). 2018. Tick-Borne Disease Working Group 2018 report to Congress. https://www.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/tbdwg-report-to-congress-2018.pdf (accessed November 27, 2024).

TBDWG. 2020. Tick-Borne Disease Working Group 2020 report to Congress. https://www.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/tbdwg-2020-report_to-ongress-final.pdf (accessed November 27, 2024).

Tokarz, R., T. Tagliafierro, S. Sameroff, D. M. Cucura, A. Oleynik, X. Che, K. Jain, and W. I. Lipkin. 2019. Microbiome analysis of Ixodes scapularis ticks from New York and Connecticut. Ticks and Tick-Borne Diseases 10(4):894–900.

Tyler, S., S. Tyson, A. Dibernardo, M. Drebot, E. J. Feil, M. Graham, N. C. Knox, L. R. Lindsay, G. Margos, S. Mechai, G. Van Domselaar, H. A. Thorpe, and N. H. Ogden. 2018. Whole genome sequencing and phylogenetic analysis of strains of the agent of Lyme disease Borrelia burgdorferi from Canadian emergence zones. Science Reports 8(1):10552.

van den Wijngaard, C. C., A. Hofhuis, A. Wong, M. G. Harms, G. A. de Wit, A. K. Lugnér, A. W. M. Suijkerbuijk, M. J. Mangen, and W. van Pelt. 2017. The cost of Lyme borreliosis. European Journal of Public Health 27(3):538–547.

Waddell, L. A., J. Greig, M. Mascarenhas, S. Harding, R. Lindsay, and N. Ogden. 2016. The accuracy of diagnostic tests for Lyme disease in humans: A systematic review and meta-analysis of North American research. PLOS One 12(11):e0168613.

Weitzner, E., D. McKenna, J. Nowakowski, C. Scavarda, R. Dornbush, S. Bittker, D. Cooper, R. B. Nadelman, P. Visintainer, I. Schwartz, and G. P. Wormser. 2015. Long-term assessment of post-treatment symptoms in patients with culture-confirmed early Lyme disease. Clinical Infectious Diseases 61(12):1800–1806.

Willems, R., N. Verhaeghe, C. Perronne, L. Borgermans, and L. Annemans. 2023. Cost of illness in patients with post-treatment Lyme disease syndrome in Belgium. European Journal of Public Health 33(4):668–674.

Winslow, C., and J. Coburn. 2019. Recent discoveries and advancements in research on the Lyme disease spirochete Borrelia burgdorferi. F1000Res 8:F1000 Faculty Rev-763.

Wisconsin Department of Health Services. 2024. Lyme disease: Wisconsin data. https://www.dhs.wisconsin.gov/tick/Lyme-data.htm (accessed January 27, 2025).

Wormser, G. P. 2006. Early Lyme disease. New England Journal of Medicine 354(26):2794–2801.

Wormser, G. P., E. Masters, J. Nowakowski, D. McKenna, D. Holmgren, K. Ma, L. Ihde, L. F. Cavaliere, and R. B. Nadelman. 2005. Prospective clinical evaluation of patients from Missouri and New York with erythema migrans-like skin lesions. Clinical Infectious Diseases 41(7):958–965.

Wormser, G. P., R. J. Dattwyler, E. D. Shapiro, J. J. Halperin, A. C. Steere, M. S. Klempner, P. J. Krause, J. S. Bakken, F. Strle, G. Stanek, L. Bockenstedt, D. Fish, J. S. Dumler, and R. B. Nadelman. 2006. The clinical assessment, treatment, and prevention of Lyme disease, human granulocytic anaplasmosis, and babesiosis: Clinical practice guidelines by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clinical Infectious Diseases 43(9):1089–1134.

Wormser, G. P., D. McKenna, C. L. Karmen, K. D. Shaffer, J. H. Silverman, J. Nowakowski, C. Scavarda, E. D. Shapiro, and P. Visintainer. 2020. Prospective evaluation of the frequency and severity of symptoms in Lyme disease patients with erythema migrans compared with matched controls at baseline, 6 months, and 12 months. Clinical Infectious Diseases 71(12):3118–3124.

This page intentionally left blank.