Charting a Path Toward New Treatments for Lyme Infection-Associated Chronic Illnesses (2025)

Chapter: 2 State of the Evidence

2

State of the Evidence

The committee was charged with reviewing the current gaps in knowledge regarding the etiology and treatment of Lyme infection-associated chronic illnesses (IACI). The committee addressed this charge in two components. First, to understand the link between Borrelia infection and Lyme IACI, the committee reviewed evidence on the prevalence of persistent, generalized symptoms (e.g., fatigue, pain, brain fog) among U.S. individuals who had Lyme disease compared with those without previous Lyme disease. This knowledge is foundational to the interpretation of findings on the disease’s etiology and to inform future study design. Second, the committee examined the evidence concerning treatment effectiveness and potential disease mechanisms, as well as diagnostic tools for Lyme IACI, given their critical role as part of disease treatment and etiology research. This was accomplished through a scoping review of the peer-reviewed literature. Both components were complicated by the absence of a consensus definition or diagnostic biomarkers for Lyme IACI. This chapter starts with describing an operational scope of the committee’s literature review, which is followed by an assessment of the published evidence.

OPERATIONAL SCOPE FOR LITERATURE REVIEW ON LYME IACI RESEARCH

For this literature review, the committee considered the scope of “Lyme IACI” to include an illness with otherwise unexplained symptoms that persist at least 6 months following antibiotic treatment for either proven or presumed infection with Borrelia spp. that cause Lyme disease. Due to the

lack of a gold standard diagnostic for Lyme IACI and the heterogeneity with which the population of interest has been reported in the existing literature, the committee’s consideration of Lyme IACI included both individuals with a known association with an initial infection by Borrelia spp. and those with an unproven but possible association to these infections. Inclusion under this operational scope was dependent on the study population as described in the research publications (i.e., studies of unexplained fatigue conducted in Lyme disease endemic areas but without a description of Lyme disease history or connection were not sought out or included).

The first group under the operational scope consists of individuals with confirmed Lyme disease based on a history of an erythema migrans (EM) or other clinical findings consistent with Lyme disease and positive two-tier Lyme disease serology, and persistent illness for 6 months following antibiotic treatment. This is similar to the case definition of post-treatment Lyme disease syndrome (PTLDS; Box 2-1) and the criteria for Group 1 from a recently proposed research classification for studying Lyme IACI (Fallon et al., 2025).

The second group comprises individuals who were treated for suspected Lyme disease but experience persistent symptoms without a confirmed previous Borrelia spp. infection (i.e., without a history of observed EM or documented confirmatory two-tier seropositivity), have possible epidemiologic exposure to infected ticks (i.e., reside, work, or visit in a Lyme disease endemic area), and for whom alternative diagnoses have been excluded. This group may include individuals with delayed Lyme disease diagnosis, such as those who may have limited knowledge of the disease and those who may not have had access to adequate tests or medical care (Gould et al., 2024; NCFH, 2023). This group may also capture individuals with similar symptoms whose illness is not directly related to prior Borrelia spp. infection, including other infectious or noninfectious etiologies. It is important that a comprehensive evaluation be undertaken to exclude alternative diagnoses and to minimize the improper inclusion of individuals with a known cause of their symptoms that is not Lyme IACI in this second group. Given the uncertain etiology in this group, the degree of comprehensiveness in clinical evaluation may vary significantly, contributing to the challenges in studying this heterogeneous group.

As many chronic illnesses with a potential infectious trigger share similar symptoms with Lyme IACI, attribution of an individual’s symptoms to a specific infectious agent may not always be possible. The nearly universal exposure to SARS-CoV-2 and the potential consequences of Long COVID further complicates this issue of attribution.1 Chapter 3 will explore con-

___________________

1 This challenge also highlights the critical role of biobanks, particularly the collection and maintenance of pre-COVID-19 samples that can serve as important experimental controls. See Chapter 4 for more discussion on biobanks.

nections between research on Lyme IACI and research on similar chronic conditions, including how the investigation of such similar conditions may identify common treatment approaches for Lyme IACI and these conditions.

EPIDEMIOLOGY OF LYME IACI

The association between Lyme disease and persistent, multisystem symptoms has been described in research publications and reaffirmed by the Tick-Borne Disease Working Group, a federal advisory committee of the Department of Health and Human Services (Aucott et al., 2013; TBDWG, 2018, 2020, 2022; Wormser et al., 2006).2,3 However, the prevalence of symptoms in individuals who have been infected by Borrelia spp. compared with those without infection is also important to establish. The risk for contracting Lyme disease fluctuates based on environmental and behavioral factors (e.g., where one lives or visits, what one does for work or recreation), and people are not routinely tested for Borrelia infections unless they exhibit symptoms. In addition, many conditions with similar symptoms are relatively common in the U.S. population—the prevalence of myalgic encephalomyelitis (ME/CFS) and fibromyalgia, two such conditions that may present the same symptoms as Lyme IACI, have been reported as 0.9 percent and 2 percent, respectively—potentially contributing to the misattribution of Lyme IACI in epidemiologic studies (American College of Rheumatology, 2023; Choutka et al., 2022; IOM, 2011).4

___________________

2 The Tick-borne Disease Workgroup is a federal advisory committee established from the 21st Century Cures Act and was active from 2016 to 2022. Its formation follows a federal advisory committee on ME/CSF, whose work spanned from 2002 to 2018. A federal advisory committee on Long COVID was established in August 2023 and disbanded by Executive Order in February 2025. See: Renewal of Charters for Certain Federal Advisory Committees, 81 Fed Reg. 74456. (October 26, 2016), Establishment of the Office of Long COVID Research and Practice, 88 Fed Reg. 50159. (August 1, 2023); Commencing the Reduction of the Federal Bureaucracy, 90 Fed Reg. 10577. (February 25, 2025), and “Chronic Fatigue Syndrome Advisory Committee,” U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, archived January 28, 2019, at https://wayback.archive-it.org/org-745/20190128204246/https:/www.hhs.gov/ash/advisory-committees/cfsac/index.html.

3 While this study was not conducted in response to the recommendation in the 2022 report of the Tick-borne Disease Working Group, which called on the National Academies to review the evidence for diagnosis and treatment to establish “what is definitely known, what is partially understood, and what remains unknown” for Lyme disease, with emphasis on early disease and the persistent symptoms, the current report includes a review of the scientific and clinical evidence on causes, disease mechanisms, diagnosis, and treatment of Lyme IACI. In addition, this report includes a review of the clinical evidence in treating other IACI to illuminate a path toward advancing new treatments for Lyme IACI.

4 Some cases of ME/CFS and fibromyalgia may stem from Lyme disease and would be considered as part of Lyme IACI (see Hu et al., 2025, and Gluckman et al., 2025).

Prospective Studies

The ideal method to accurately determine the incidence of Lyme IACI would be a prospective cohort study that tracks individuals from the time of Borrelia infection compared with control groups to compare the incidence of persistent symptoms that arise between infected and uninfected individuals. In a prospective cohort of 1,135 patients in The Netherlands with Lyme disease treated with recommended antibiotics as well as two control groups (Ursinus et al., 2021), the cumulative incidence of symptoms (fatigue, pain, or cognitive impairment) that persisted for at least 6 months was 27.2 percent in the Lyme disease group and 34.3 percent in the subgroup that had disseminated Lyme disease. However, these symptoms were quite common in the controls as well—21.2 percent in healthy controls and 23.3 percent in the tick bite only group. The relatively small difference in the frequency of symptoms between the Lyme disease group and the control groups demonstrates the importance of including appropriate comparator groups. The National Institutes of Health has committed funding for a similar prospective study to take place in the United States over the next 4.5 years (NIH Reporter, 2025).

PTLDS is a stringent but consistent research definition that allows for comparisons between studies. This definition has been used in small-scale prospective studies in the United States to estimate the rate of developing persistent symptoms associated with Lyme disease. These studies found that the portion of adults with confirmed Lyme disease who develop PTLDS ranges from 5 to 36 percent, leading to an often-cited figure of an average 10–20 percent (Aucott et al., 2013; Aucott et al., 2022; Weitzner et al., 2015; Wormser et al., 2015, 2020). This wide range can be explained by differences in inclusion criteria, study designs (e.g., clinical studies versus database studies), and data sources (e.g., health records, insurance claims, patient-led data registries). Table 2-1 summarizes the findings from studies that have measured the prevalence of PTLDS in various patient populations in the United States.

Retrospective Studies

Electronic health records and insurance claims can be used to assemble large cohorts. Their utility, however, is limited by a lack of patient-level information, including details of Lyme disease diagnosis, comorbidities, and symptoms. A study that analyzed records from 48,596 adults who sought medical attention and received the Lyme disease diagnostic code found that 3.1 percent had symptoms matching PTLDS criteria in the 2 years after the Lyme disease diagnosis (Chung et al., 2023).

There is limited evidence of the prevalence of persistent symptoms in children after Lyme disease. In the only published study of persistence of

TABLE 2-1 Summary of Prospective Studies Reviewing the Prevalence of PTLDS

| Study | PTLDS symptom(s) defined and assessed by study | Study groups | PTLDS prevalence (n) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lyme disease | Control (type) | Lyme disease group | Control group | ||

| Wormser et al. (2020) | At least one of the following symptoms through self-report: fatigue, headache, stiff neck, joint pain, muscle pain, decreased appetite, difficulty with concentration/memory, feeling feverish/chilly, dizziness, tingling/abnormal sensation, nausea or vomiting, cough | 52 | 104 (healthy, LD-negative, recruited from same primary care site as LD group) |

|

|

| Wormser et al. (2015) | Persistent fatigue (score ≥ 4.0 on the 11-Item Fatigue Severity Scale, FSS-11) coincident with onset of Lyme disease, lasted at least 6 months in the first year after treatment, had no other known explanation other than history of Lyme disease, and persisted at least intermittently until the time of the visit | 100 | N/A |

(based on clinical assessment, 3 may have post-Lyme disease fatigue despite FSS-11 score < 4 |

|

| Aucott et al. (2013) | Operationalized definition of PTLDS: self-reported presence of new-onset fatigue, widespread musculoskeletal pain, or neurocognitive difficulties | 71 | 14 (healthy, LD-negative, recruited from same primary care site as LD group, matched to LD cases based on age, sex, and time of enrollment) |

|

|

| Aucott et al. (2022) |

Operationalized definition of PTLD fulfills either symptoms or both criteria at least one of the two follow-ups (6-month, 12-month):

|

234 | 49 (no clinical or serologic history of Lyme disease, no overlapping symptoms with PTLDS, recruited from same primary care site as LD group) |

|

|

| Weitzner et al. (2015) | Symptoms that were otherwise unexplained within 6 months after diagnosis of Lyme disease and lasted for at least 6 months following the completion of antibiotic therapy | 128 | N/A |

|

N/A |

NOTE: LD = Lyme disease; N/A = not applicable; PTLDS = post-treatment Lyme disease syndrome.

symptoms after Lyme disease in the pediatric population is a retrospective survey. In it, 402 children and adolescents were identified for enrollment based on a review of the available electronic health records. Of these, 102 participants were confirmed as eligible for inclusion and consented to enroll in the study. Questionnaires were completed, on average (mean), 2 years after initial diagnosis. Among the respondents, 13 percent experienced persistent symptoms although most did not recall an impact on function (Monaghan et al., 2024). Prospective studies to further examine the frequency and severity of persistent symptoms after Lyme disease in the pediatric population are needed.

Modeling Studies

Simulation or other modeling studies can be a helpful adjunct to estimating disease prevalence, which does not require extensive coordination and data reporting from public health jurisdictions around the country. However, the accuracy of projections from simulations are highly dependent on the quality of data that define the parameters of the underlying model. A simulation of six scenarios based on different estimates of Lyme disease incidence and the likelihood of developing PTLDS (an assumption of either 10 percent or 20 percent) have reported estimated prevalent cases of PTLDS by 2020 to range widely from 69,011 to 1,944,189 (DeLong et al., 2019). However, this simulation had to make key assumptions to address the lack of available data. For example, the model does not include a rate of recovery from PTLDS. It also assumes, in the scenario with the highest prevalence estimate, a linear growth of Lyme disease incident cases from 329,000 cases in 2005 continuing until 2020. The need to use various assumptions in key parameters of this model underscores the need for data in this field. As more knowledge on the development and disease course of Lyme IACI emerges, simulations can be refined to provide more precise estimates on the disease prevalence.

Risk Factors for Developing Lyme IACI

Characteristics that have been associated with an increased likelihood of developing persistent symptoms following Lyme disease include previous traumatic life events (Aucott et al., 2022; Mustafiz et al., 2022; Solomon et al., 1998), female sex (Johnson et al., 2023), and delayed initial antibiotic treatment (Asch et al., 1994; Shadick et al., 1994). Notably, the association between persistent symptoms and female sex is based on data from a majority female patient registry (85 percent female, 15 percent male), and individuals who have persistent symptoms are likely to be overrepresented in a self-reported registry. Furthermore, associations with certain characteristics may not suggest causation or indicate that the characteristics

identified through association are indeed risk factors for developing Lyme IACI. However, sex-based differences in responses to infectious diseases as well as in diagnosis and care have been well documented (Klein and Flanagan, 2016; Mauvais-Jarvis et al., 2020; Sun et al., 2023), and females are also disproportionately affected in other similar chronic conditions with unknown etiology, such as ME/CFS (Bretherick et al., 2023; Faro et al., 2016).

Individual immunologic differences in the human host may predict the development of PTLDS (Aucott et al., 2016; Bouquet et al., 2016); on the other hand, no relationship has been found between B. burgdorferi genotype and the risk of developing PTLDS (Lemieux et al., 2023). While there may be certain occupations at higher risk for Lyme disease or tickborne diseases in general (Adjemian et al., 2012; Piacentino and Schwartz, 2002), no association between occupation and risk of Lyme IACI has been documented. Environmental risk factors or triggers including exposure to chemical contaminants have been associated with Gulf War illness, another chronic condition with multisystem symptoms overlapping with Lyme IACI, but they have not been reported in association with Lyme IACI (Elhaj and Reynolds, 2023; Haley et al., 2022).

Additional prospective studies are needed to determine the prevalence and likelihood of developing Lyme IACI in the United States, including in the pediatric population. Regardless, findings to date support the hypothesis that individuals with Lyme disease, even after antibiotics treatment, are more likely to develop persistent, multi-system symptoms. It is not possible to determine whether these symptoms stem from Lyme disease or another cause (e.g., Long COVID, ME/CFS, fibromyalgia).

Conclusion 2-1: A subset of individuals who are infected with and treated for Borrelia spp. subsequently develop persistent symptoms that can often be debilitating.

Conclusion 2-2: The lack of a consensus definition for Lyme IACI makes it difficult to accurately determine the population prevalence.

A SCOPING REVIEW OF THE LITERATURE

The committee arranged for a scoping review of the literature to be conducted in order to assess the breadth of the available published research on the treatment, mechanisms, and diagnosis of Lyme IACI. The scoping review included peer-reviewed research published between January 1970 and May 2024. The review exclusively covered studies that were conducted within or used samples from North America, based on previously described differences in Lyme disease by geographic region. A summary of this scoping review findings are provided below.

Scoping Review Methods

The methodology used for the scoping review is described in detail in Appendix C and summarized here. Search terms were chosen to be broadly descriptive and reflect the Lyme IACI operational scope. The preliminary literature search was conducted in PubMed, Medline (Ovid), Embase (Ovid), and Scopus databases by a research librarian at the National Academies. Two supplemental searches were conducted to identify articles that may not have been captured by the initial database searches. The first was a manual review of the references from the 10 most recent review articles addressing Lyme IACI. The second expanded the search terms used in the preliminary search to include older publications, which used index terms not initially considered (e.g., neuroborreliosis) in PubMed and Embase.

The initial screening of article titles and abstracts was performed by two reviewers (National Academies staff), and conflicts were adjudicated by a third National Academies staff member. Included abstracts were categorized as addressing research questions related to the treatment, diagnosis, or mechanisms (or some combination thereof) of Lyme IACI and subsequently screened for full-text review based on predefined inclusion and exclusion criteria. A final screening of full-text articles was conducted by two methodology consultants from PICO Portal and a National Academies staff member. Review of and data extraction from included full-text articles were performed by one consultant methodologist and verified by a second methodologist.

The diagnostic status (i.e., clinical or laboratory documentation of Lyme disease using approved test methods, or whether someone met the PTLDS definition) of participants in clinical studies or samples derived from volunteers that are used in basic science studies is a critical piece of information for interpretation of the research results. However, the degree of detail reported among the literature varies greatly. Most studies affirm that patients or study participants have clinical or laboratory documentation of Lyme disease as described in the PTLDS definition.

The Evidence Landscape

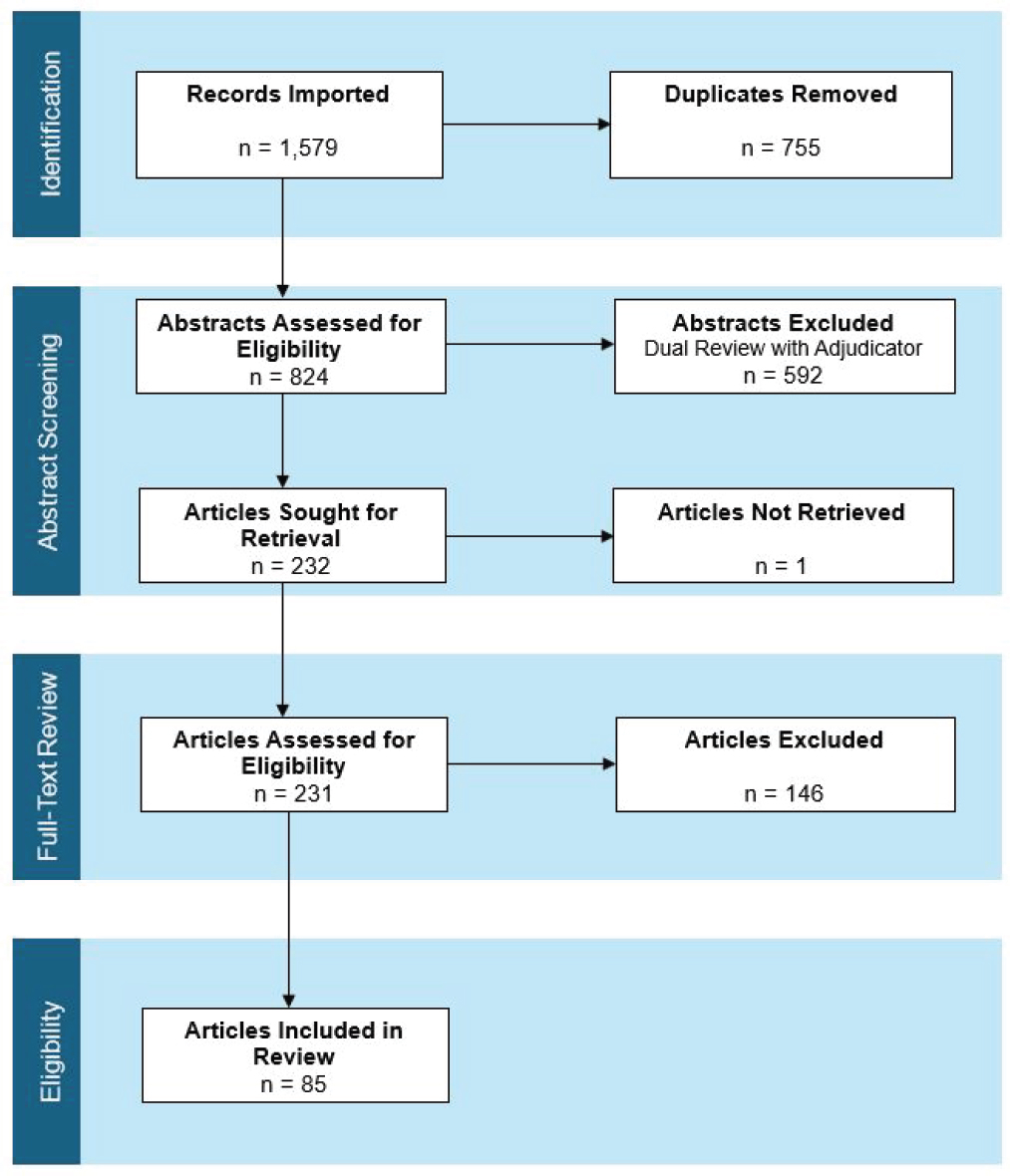

After de-duplication, the combined primary and supplemental literature search yielded 824 unique abstracts (Figure 2-1). Initial screening with the dual review resulted in 232 records for full-text retrieval. One publication could not be retrieved, and 146 articles were excluded after full-text review, resulting in 85 articles that were ultimately included in the scoping review. Notably, the publications used inconsistent definitions of Lyme IACI. Some of the terms used included post-treatment Lyme disease, persistent Lyme encephalopathy, chronic Lyme disease, and post-Lyme disease syndrome.

NOTE: n = number.

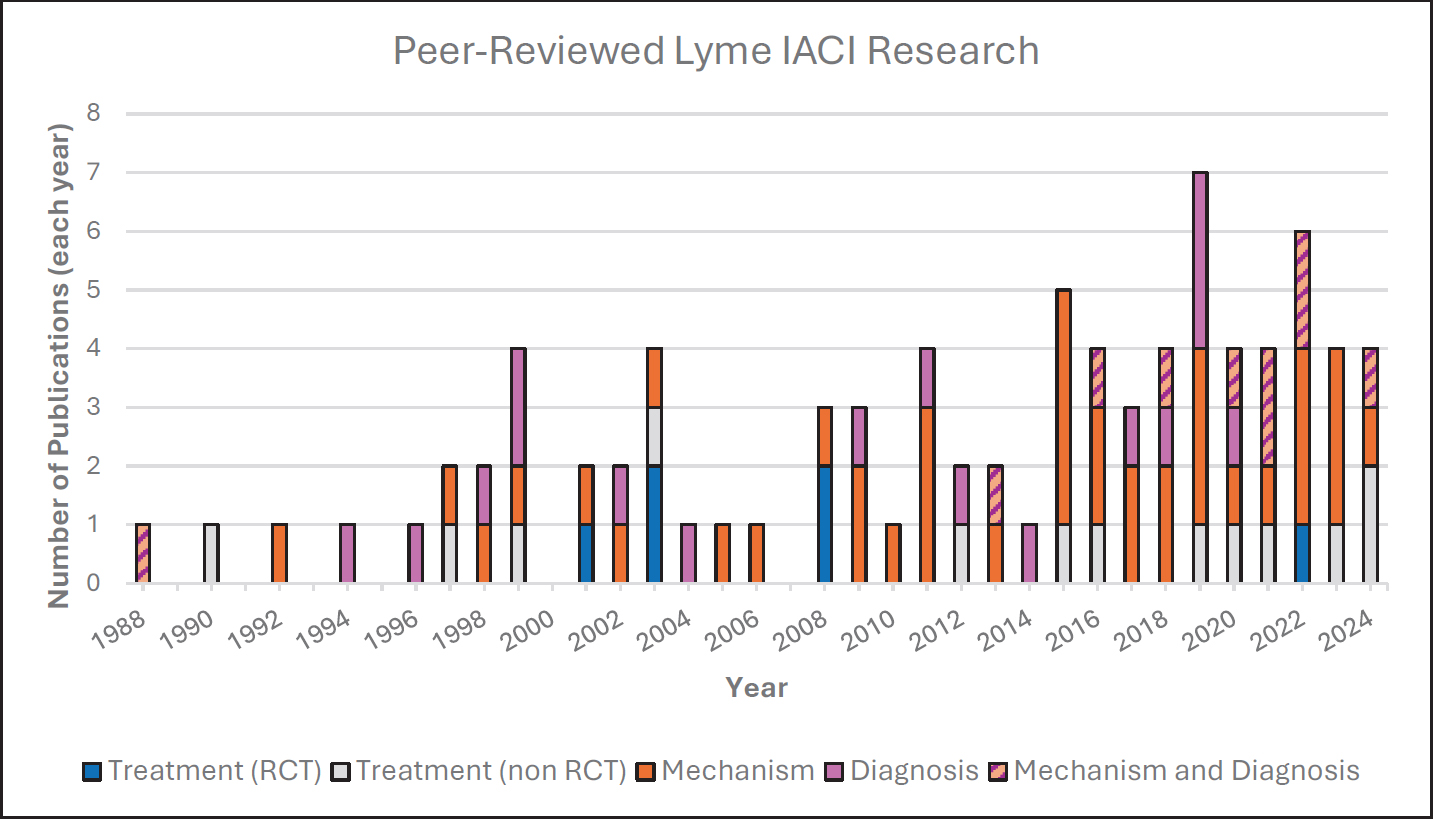

Of the 85 manuscripts included in the scoping review, 49 reported on concepts related to the potential disease mechanisms for Lyme IACI, 19 studies evaluated Lyme IACI treatments, and 27 addressed findings related to Lyme IACI diagnosis (Figure 2-2). Ten articles reported on more than one of the three categories. The majority of manuscripts reported findings from observational studies except when the goal was to evaluate treatments.

Next, the committee summarizes findings for the treatment, mechanisms, and diagnosis of Lyme IACI.

NOTES: IACI = infection-associated chronic illness; RCT = randomized controlled trial.

EVIDENCE ON THE TREATMENT OF LYME IACI

Randomized trials are the preferred design for determining the effectiveness of medical treatments. Well-designed randomized trials include clearly specified eligibility criteria, treatment strategies, and outcomes of interest. The population(s) eligible for a trial will depend on the study’s goals. In the case of Lyme IACI, eligibility for a trial could be narrow (e.g., PTLDS) or broad (e.g., persistent symptoms after a tick bite).

In randomized trials, participants are randomly assigned to one of several treatment strategies and followed for a prespecified time with periodic measures of the outcomes of interest. Outcome measures can include clinical findings evaluated by medical professionals, patient-reported outcomes (PROs) measured by validated tools, or changes in particular biomarkers determined through laboratory tests. Currently, clinical findings and some PROs are used in Lyme IACI studies, but there are no laboratory biomarkers that are validated for the measurement of Lyme IACI disease course or treatment response.

Selecting appropriate outcome measures is critical for randomized trials. Failing to measure outcomes that may be affected by the intervention being tested could lead to inaccurate results and incorrect conclusions. Studies may examine the effects of a treatment on many outcome measures or may be directed at specific symptoms with limited outcome measures. The choice for outcomes measures may be informed by what is known of the disease etiology and pathogenesis, the intervention’s mechanism of action, and patients’ lived experience. Due to the subjective aspects of several symptoms in Lyme IACI (e.g., pain, fatigue, and cognitive function), PROs are necessary to capture findings that are important to people living with Lyme IACI. Research funders and regulatory agencies have also increasingly supported the inclusion of PROs in clinical research and product development. For example: the National Institutes of Health (NIH) developed the Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System, a large, public reporting system of PROs (NIH, 2025), and the Food and Drug Administration has published guidance documents for industry (HHS et al., 2009).

Since many different existing tools are used to measure clinical outcomes in studies, it can complicate comparisons between studies (Mayo-Wilson et al., 2017). To measure outcomes that matter to people living with Lyme IACI, researchers need assessment instruments that are valid (i.e., accurately measure the intended construct), reliable (i.e., free of measurement error), responsive (i.e., can detect change in the outcome), and interpretable (i.e., can connect with clinically meaningful changes).

Another critical aspect of randomized trials is that they are informative when they provide effect estimates that are sufficiently precise. Take,

for example, a randomized trial testing the effect of a certain treatment on a specific outcome estimates a relative risk of 0.8 with a 95 percent confidence interval from 0.4 to 2.2 (a relative risk of 1 indicates no effect). The boundary of the confidence interval is interpreted to mean that any values between a 60 percent lower risk and more than twofold higher risk are compatible with the study data. Under this interpretation with conventional statistical criteria, the result is too imprecise to confidently determine that the treatment should not be further investigated. That is, this hypothetical trial does not provide adequate information to guide decisions. Given that randomized trials require a substantial investment of societal resources, trials must be properly designed to provide informative results, which requires that a sufficient number of participants be enrolled. In fact, in a functioning research system, small trials are infeasible for ethical reasons: institutional review boards would not approve human experimentations that are not expected to result in helpful findings, and potential participants might refuse to enroll when the expected imprecise results are disclosed during the informed consent process.

Studies based on observational data may be used in attempts to emulate randomized trials. Explicit target trial emulations, in which the concepts of clinical trials are applied to observational studies eliminate common biases in observational research (e.g., biases that arise from selection of participants or from attempting to recall past events). However, unlike in a randomized trial, the factors that determine the receipt of a particular treatment in the real world may themselves be prognostic factors. If these confounders are not appropriately measured and adjusted for, observational emulations of target trials may be subject to residual confounding bias.

The committee also considered the heterogeneity of the population of people living with Lyme IACI and the implications for assessing the efficacy and safety of potential treatments. Ideally, studies to evaluate efficacy and safety for new treatments would be designed and conducted with clearly defined patient populations to monitor beneficial or adverse effects of the intervention in patients. Therefore, studies assessing variably defined populations may be hard to compare, and results may not apply to the entire Lyme IACI population.

Summary of Current Evidence

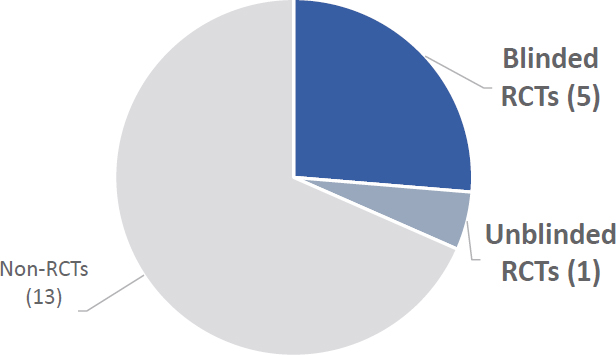

Of the 19 primary research studies with human participants assessing treatments for Lyme IACI, six were randomized controlled trials of variable methodological quality (Cameron, 2008; Fallon et al., 2008; Kaplan et al., 2003; Klempner et al., 2001; Krupp et al., 2003; Murray

NOTES: IACI = infection-associated chronic illnesses; RCT = randomized controlled trial.

et al., 2022).5 The remainder were observational studies or single-arm interventional studies enrolling people living with Lyme IACI at a single medical center (Figure 2-3).

The interventions in five of the six randomized trials were antibiotic treatments, and the remaining randomized trial evaluated yoga. Alternative medicine treatments that people with Lyme IACI have reported using (e.g., herbal therapies and acupuncture) have not been rigorously investigated in randomized trials. No randomized trials have been conducted in the pediatric population. Table 2-2 summarizes the design and outcomes of the six randomized trials.

Extended courses (up to 3 months) of antibiotics known to be effective for acute B. burgdorferi infection have been studied in five well-designed randomized trials. Two of these trials studied 30 days of intravenous ceftriaxone followed by 60 days of oral doxycycline, one study assessed 28 days of intravenous ceftriaxone, one study evaluated 3 months of oral amoxicillin, and the fifth study assessed 10 weeks of intravenous ceftriaxone. Taken together, these randomized controlled trials did not demonstrate a sustained benefit from treatment with extended courses of antibiotics. Furthermore, while one study did not report safety monitoring, the other four studies all reported adverse effects associated with the treatment. There remains ongoing debate over the trial designs and outcomes, as discussed through extensive reanalyses of the available data (Delong et al., 2012; Fallon et al., 2012; Klempner et al., 2013) and in summaries in the TBDWG reports (TBDWG, 2020, 2022).

___________________

5 Klempner et al. (2001) and Kaplan et al. (2003) review the same two randomized trials.

TABLE 2-2 Key Study Characteristics from Randomized Trials

| Study | Klempner et al. (2001)1 | Krupp et al. (2003) | Cameron (2008) | Fallon et al. (2008) | Murray et al. (2022) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Seropositive study | Seronegative study | |||||

| Sample size | 78 | 51 | 55 | 86 | 37 | 29 |

| Eligibility | Positive Western blot for IgG antibodies against B. burgdorferi; and at least 1 of the following symptoms that interfered with function: musculoskeletal pain, cognitive impairment, radicular pain, or abnormal burning or itching sensation | Documentation of EM rash and negative Western blot; and at least 1 of the following symptoms that interfered with function: musculoskeletal pain, cognitive impairment, radicular pain, or abnormal burning or itching sensation | Documented EM rash or CDC-defined late manifestation of Lyme validated by positive ELISA or Western blot, completion of standard antibiotic treatment at least 6 months prior to enrollment; and current severe fatigue | Recurrence of Lyme disease symptoms after initial successful treatment; no specific symptoms were reported as inclusion criteria, but fatigue, stiff or painful joints, headaches, poor concentration, muscle soreness, sleep disturbances were present in more than 80% of participants at baseline | Documented EM rash or CDC-defined manifestation of Lyme disease and positive or equivocal ELISA confirmed by Western blot, current positive IgG Western blot, at least 3 weeks IV ceftriaxone treatment for Lyme at least 4 months before enrollment; and subjective and objective memory impairment starting after Lyme onset | Clinician diagnosis of Lyme disease at least 6 months prior to enrollment, received IDSA-recommended antibiotic treatment for Lyme; have symptoms starting within 6 months after Lyme onset and persisting at least 6 months; pain or fatigue as primary symptom complaint |

| Intervention | Antibiotic (30 days of IV ceftriaxone [2g/day] followed by 60 days of oral doxycycline [100mg twice/day]) | Antibiotic (30 days of IV ceftriaxone [2g/day] followed by 60 days of oral doxycycline [100mg twice/day]) | Antibiotic (28 days of IV ceftriaxone [2g/day]) | Antibiotic (3 months of oral amoxicillin [3g/day]) | Antibiotic (10 weeks of IV ceftriaxone [2g/day]) | Kundalini yoga (8 weeks of a 90-min session once/week in groups of 4–6 participants) |

| Control | Placebo | Placebo | Placebo | Placebo | Placebo | Waitlist control |

| Blinding | Double blinded | Double blinded | Double blinded | Double blinded | Double blinded | Unblinded |

| Outcomes | Health-related quality of life at 180 days; cognitive function, pain, role functioning, neuropsych-ological test scores, and mood at 60 and 180 days | Health-related quality of life at 180 days; cognitive function, pain, role functioning, neuropsych-ological test scores, and mood at 60 and 180 days | Fatigue, mental speed, OspA antigen clearance at 6 months | Quality of life at 6 months | Neuro-psychological symptoms at 24 weeks | Pain, pain interference, fatigue, and global health at 8 weeks |

| Results | 13 participants (37%) assigned to the intervention showed improved quality of life compared with 14 participants (40%) in the placebo group. 12 participants (34%) in both the intervention and placebo groups had worsened quality of life. | 10 participants (45%) assigned to the intervention showed improved quality of life compared with 7 participants (30%) in the placebo group. 6 participants (27%) in the intervention group and 8 participants (35%) in the placebo group had worsened quality of life. | 18 participants (64%) in intervention group had reduced fatigue compared with 5 participants (19%) in the placebo group. Two participants in both the intervention and placebo arms had increased mental speed, reflecting 8% and 9%, respectively. OspA antigen was only present in 9 participants at baseline. At follow-up, all 4 participants that received the intervention were negative for OspA, and 3 of 4 participant in the placebo arm were negative. | 46% of participants randomized to intervention had improved quality of life compared with 18% of those assigned to placebo. In a subset of 48 participants who completed the trial, average improvement in the mental component of quality of life (measured by SF-36 score) was 14.4 in intervention arm vs. 6.2 in placebo arm. Average improvement in the physical component of quality of life was 8.5 in intervention arm vs. 7 in placebo arm. | According to predefined effect size cutoffs for small, moderate, and large improvement of 0.2, 0.5, and 0.8, respectively, the intervention group demonstrated a large improvement (effect size = 1.1) in cognitive index compared with a moderate improvement in the group receiving placebo (effect size = 0.72). | Pain decreased by an average of 1.37 points (on 10-point scale) in both the intervention and control arms. Pain interference decreased by 4.44 points in intervention group vs. 2.96 in control. Fatigue improved by 4.54 points in intervention arm and 0.41 points in control arm. And global health increased in the intervention arm by 0.72 points compared with 0.37 points in the control arm. |

1 The results from the Kaplan et al., 2003 are not included in this table because the data in that article are a combination of results from the seropositivity and seronegativity study together.

NOTE: EM = erythema migrans; CDC = Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; ELISA = enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay; IDSA = Infectious Diseases Society of America; IgG = immunoglobulin G; IV = intravenous; OspA = outer surface protein A.

Randomized controlled trials remain the preferred method to determine efficacy of an intervention, but even well-designed trials may be limited by the available methods or tools (Bauchner et al., 2019). Although the results of the antibiotic trials to date are disappointing, it is important to note that they address only one of a number of hypothesized mechanisms for persistent illness in persons with Lyme IACI. To date, there is only one randomized trial that addresses symptom relief through other potential disease mechanisms. There is currently insufficient evidence of benefit from a small study evaluating the effect of Kundalini yoga, but it is a generally safe intervention (Murray et al., 2022). The discovery of biomarkers or other more precise measures of efficacy could lead to additional trials of extended antibiotic treatment or to combinations of interventions targeting plausible mechanisms for persistent illness, as suggested in the 2022 TBDWG. It is important to build on the existing evidence and the incorporation of new findings as they become available through ongoing research into the pathogenesis of Lyme IACI and similar conditions to direct future research (see Chapters 3 and 4). The current evidence affirms that new approaches for treatment of persons suffering with Lyme IACI are needed.

In contrast to the results from the randomized controlled trials, 52 percent of the respondents in the MyLymeData patient registry reported taking antibiotics to manage their symptoms, and, of those, 38 percent self-reported the treatment as being moderately or very effective (MyLymeData, 2019). The reason for this discrepancy in reported effectiveness of antibiotic treatment between randomized trials and patient registry survey have not been explored, but there are generally limitations to using and interpreting retrospective registry data, including the need to control or account for bias in the data and, similar to randomized controlled trials, the challenges in controlling for placebo effects in the use and interpretation of the data. The choice of antibiotics as treatment is predicated on the assumption that persistent infection is the cause of Lyme IACI, although some antibiotics such as doxycycline and ceftriaxone also have anti-inflammatory activity that may have had a role in alleviating symptoms. However, as will be discussed later in this chapter, the pathogenesis of Lyme IACI remains poorly understood.

The methodological rigor of the 13 observational or single-arm studies was generally low. These studies, by design, do not include randomization or blinding but could include controls. However, none of the studies included a control or comparator group. In clinical studies, the use of controls, randomization, and blinding are important to increase the confidence in the results by accounting for the previously demonstrated placebo effect, in which individuals who received no active treatment reported improvement in their symptoms (Marques, 2008). These studies have evaluated a variety of interventions, including antibiotics, anti-infective agents,

electromagnetic radiation, exercise, immunosuppressants, dietary interventions, nutritional supplements, and mind–body interventions (D’Adamo et al., 2015; Derderian and Otenbaker, 2024; Donta, 1997, 2003; Fallon et al., 1999; Horowitz and Freeman, 2016, 2019; Horowitz et al., 2023; Jernigan et al., 2021; Logigian et al., 1990; Johnson et al., 2020; Nicolson et al., 2012; Shere-Wolfe et al., 2024). However, the methodological limitations of these studies prevented the committee from interpreting their outcomes.

Outcome measures varied between studies. The majority assessed fatigue, cognitive function, or musculoskeletal pain or some combination of those, while a few studies also assessed neuropathy, psychiatric, gastrointestinal, and cardiac symptoms. The 36-Item Short Form Survey (SF-36) was the most frequently used outcome measurement tool. However, there was a high degree of variability in the tools used in the studies, including general tools such as the SF-36 and disease-specific tools such as the General Symptom Questionnaire-30 (GSQ-30). Standardization of the outcome measurement tools used in Lyme IACI research is a prerequisite for reproducible research and comparability between studies.

Conclusion 2-3: Results from studies that are conducted without randomization, controls, or blinding provide insufficient evidence to guide patients and clinicians in treatment decisions.

Conclusion 2-4: Many studies in the Lyme IACI literature have small sample sizes that limit the accuracy of their results.

Conclusion 2-5: Patient-reported symptoms have not been consistently or always adequately addressed in published treatment trials for Lyme IACI.

Conclusion 2-6: No safe and effective therapies for the treatment of Lyme IACI have been identified through clinical research.

EVIDENCE ON THE MECHANISMS OF LYME IACI

An understanding of disease pathogenesis can help in identifying new targets for treatment or diagnosis, inform trials to evaluate treatments and diagnostics, and ultimately lead to effective interventions. Multiple mechanisms of Lyme IACI have been proposed, including immune dysregulation and autoimmunity, pathogen or antigen persistence, central nervous system dysfunction, metabolomic changes, and microbiome changes (Marques, 2022). Studies that contribute to the understanding of disease mechanisms range from in vitro research that generates evidence to explain observed phenotypes to prospective cohort studies that observe select characteristics

in participants over time. However, preclinical and observational studies may be insufficient for moving from hypothesis generation to establishing a clear understanding of the mechanistic processes that lead to disease. This is particularly true for Lyme IACI, which may present with different symptoms in different individuals and appears to affect various pathways or systems in the body, perhaps in overlapping ways that remain difficult to untangle (Rebman and Aucott, 2020). Existing knowledge gaps in how host, pathogen, and environmental factors may influence disease development and progression further hinder the understanding of mechanistic pathways and the development of treatments for Lyme IACI.

Understanding potential disease mechanisms is complicated by the challenge of diagnosing and classifying people living with Lyme IACI. Many of the symptoms reported by individuals with Lyme IACI are common to other IACI (Choutka et al., 2022; Rebman and Aucott, 2020). While the presence of antibodies to B. burgdorferi may indicate prior or current infection, they may persist for years and do not indicate active infection (Glatz et al., 2006).

There is no widely accepted animal model for Lyme IACI. Due to the subjective nature of Lyme IACI symptoms, no well-validated approaches currently exist to assess if animals experience these symptoms. Animal models can provide insights into immunologic interactions between host and pathogen and address the potential of pathogen or antigen persistence as well as the presence or absence of associated pathologic sequelae (Crossland et al., 2018; Hodzic et al., 2014; Pavia and Wormser, 2014). The heterogeneity of the population of people living with Lyme IACI, the lack of pathologic biomarkers, and the potential for several mechanistic pathways greatly complicate the interpretation of animal model studies for Lyme IACI (Verschoor et al., 2022). The extrapolation of findings from animal studies is further complicated by immunologic adaptations in animals that serve as natural reservoirs for B. burgdorferi (i.e., many small rodent species) (Brisson et al., 2008). However, animal models may provide additional insights if objective biomarkers are identified. Well-designed human studies have the highest likelihood of yielding new insights and are important for evaluating hypotheses generated in vitro or in animal models.

Large cohorts of people living with Lyme IACI are needed to identify patterns and correlations that can be examined for causal relationships. First, large prospective cohorts of adults and children with acute B. burgdorferi infection will allow researchers to identify patient and pathogen factors associated with the development of Lyme IACI. Second, data from individuals with Lyme IACI compared to individuals without Lyme IACI can allow “deep phenotyping.” This strategy has been employed to explore mechanisms behind ME/CFS (Walitt et al., 2024), which will be discussed in more detail in Chapter 3. These prospective approaches are better suited

than retrospective designs for identifying potential causative factors that can illuminate disease mechanisms. Ultimately, interventional studies can provide confirmatory evidence for mechanistic hypotheses.

Summary of Current Evidence

The committee reviewed the published, peer-reviewed evidence on the mechanisms of Lyme IACI to identify opportunities for future research that could advance treatments for people with Lyme IACI. In developing the scoping review methodology on mechanisms, the committee aimed to identify articles that could provide information on the possible causes, processes, and pathways of Lyme IACI.

The scoping review identified 49 publications relating to the potential mechanisms of Lyme IACI. Of these references, two publications exclusively examined Lyme IACI in children, while an additional three included both children and adults. Table 2-3 outlines the study designs of the included publications. The majority of the publications reported on the results of observational studies. Ten publications reported on prospective studies, consisting of the sole interventional study, seven cohort studies, and two case-control studies.

The 49 included articles cover various themes related to mechanisms of disease, including etiology, symptomology, biomarkers, risk factors, and patient subgroups. Many publications addressed multiple of these themes within a single paper.

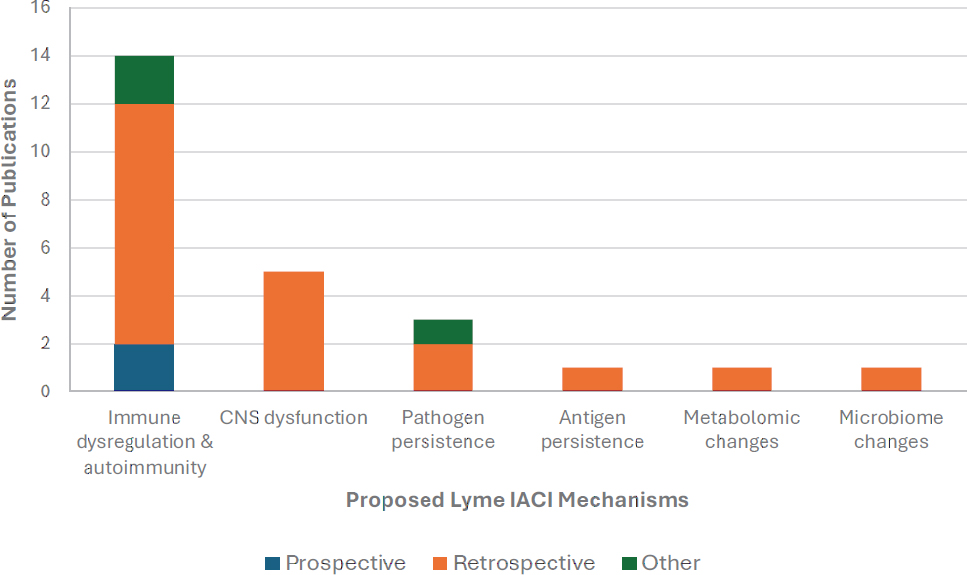

Twenty-three manuscripts addressed potential pathogenesis of Lyme IACI (Figure 2-4). These publications vary greatly in the degree to which they investigated potential etiologies, from studies with the express objective of observing particular characteristics related to a specific proposed mechanism to studies that discussed their findings in the context of several potential mechanisms. Most of the 23 studies narrowly focused their

TABLE 2-3 Study Designs of Publications in Scoping Review on Lyme IACI Mechanisms

| Interventional | |

|

Nonrandomized |

1 |

| Observational | |

|

Cohort |

10 |

|

Case–control |

37 |

|

Cross-sectional |

1 |

| TOTAL | 49 |

NOTE: IACI = infection-associated chronic illnesses.

NOTES: Some publications address multiple potential mechanisms and appear twice in the chart. “Other” includes studies that use a combination of prospective and retrospective data and studies that do not sufficiently describe their methodology. CNS = central nervous system; IACI = infection-associated chronic illnesses.

investigations on a specific characteristic or biomarker. This targeted approach to studying disease etiology may hinder the identification of potentially overlapping and interacting mechanisms. Likewise, the heterogeneity of people with Lyme IACI may complicate the interpretation of results from such studies, given that any particular characteristic or biomarker may only be present in a subset of individuals.

Two prospective studies exploring potential disease mechanisms included 149 people with Lyme disease of which at least 40 developed prolonged symptoms.6 One was a prospective cohort study of immune markers (Clarke et al., 2021), and one was a prospective case–control study of differential gene expression (Aucott et al., 2016). As demonstrated in Figure 2-4, many potential mechanisms of Lyme IACI have not been examined in prospective studies. Interventional studies—which are also inherently prospective studies—illuminate components of the disease mechanistic pathway by testing the effect of a small molecule, natural product, biologic, or medical device on observable symptoms or surrogate markers of disease pathogenesis. Additionally, well-designed and controlled prospective studies

___________________

6 One of the prospective studies did not identify the precise number of participants with Lyme IACI within the Lyme disease cohort (Clarke et al., 2021).

can provide strong evidence to support causation, unlike retrospective studies, which can only identify associations.7

Finally, while many interventional studies were summarized in the earlier section on treatments, these trials can also provide insight into disease mechanisms. As noted earlier, most of the treatment trials examine antibiotics, which presumes that the cause of Lyme IACI is the persistence of Borrelia in the body. Other potential mechanisms have rarely been evaluated through interventional studies. The lack of demonstrated effectiveness of various extended antibiotic regimens in these randomized trials suggests that pathogen persistence is not a primary driver of Lyme IACI. However, the current evidence is insufficient to entirely rule out the possibility that bacterial persistence might occur in a subset of people living with Lyme IACI. For example, case reports have suggested detection of the bacteria in postmortem human samples and in primate models that simulate the delayed treatment of Lyme disease. These and other work with uncontrolled, non-randomized studies in small cohorts or animal models cannot provide conclusive findings for Lyme IACI disease mechanisms due to their inherent methodologic limitations, but they could indicate potential future research directions.

Conclusion 2-7: Full understanding of Lyme IACI disease mechanisms remains elusive and is unlikely to be resolved in the next few years, while people living with Lyme IACI continue to suffer from chronic symptoms. Treatments trials that aim to mitigate Lyme IACI symptoms are needed while research on the disease mechanisms continues.

EVIDENCE ON THE DIAGNOSIS OF LYME IACI

Diagnostic or prognostic applications play a critical role in designing robust treatment studies to measure the effectiveness of interventions. Accurate diagnosis is essential to identify appropriate participants for enrollment (e.g., those with or without the disease). Diagnostic or prognostic tests could be used to differentiate or characterize in more detail potential subpopulations among study participants and to monitor their response to treatment. Stratifying the study population (e.g., by biomarkers, symptoms, or other phenotypes) could help reveal interventions that benefit different clusters or subgroups and build evidence for clinical tools that can be tailored for individualized care plans. This approach of using symptom clusters to manage the heterogeneity of clinical presentation and individual experience for research is being explored in Long COVID and ME/CFS (Asprusten et al.,

___________________

7 Causation is used in the statistical meaning here, and not in reference to the etiology or root cause of Lyme IACI.

2021; Vaes et al., 2023; Zhang et al., 2023a). However, while there are existing diagnostic methods and ongoing efforts to improve them for Lyme disease, there are no validated and approved diagnostic or prognostic tools for Lyme IACI. The lack of consensus definitions for Lyme IACI is a critical barrier in diagnosis. There are also no broadly accepted biomarkers for Lyme IACI. Though some candidates and associated preliminary data have been described in the research literature, there are many potential pitfalls in translation from discovery to the successful development of diagnostic assays that can be used for clinical care and research.

It is possible that there are no unique objective biomarkers or clinical features to distinguish Lyme from other IACI. It is also possible that future research will identify effective interventions for shared symptoms and mechanisms for Lyme and other IACI, bypassing the importance of differentiating each disease to guide treatment decisions. However, given the current knowledge gaps regarding these diseases, it is through efforts to achieve diagnostic certainty that discoveries will be made in identifying the shared and unique elements between Lyme and other IACI.

Diagnostic tests can be broadly categorized into non–laboratory-based and laboratory-based. The former can be administered without trained laboratorians, such as point-of-care tests given by a physician, at-home tests taken by an individual, or other over-the-counter tests sold at neighborhood pharmacies. While these tests are easy and rapid to perform outside the laboratory setting, they may lack the accuracy of traditional in vitro diagnostics. Laboratory-based tests are performed in certified clinical laboratories, with samples either collected by patients (e.g., natural secretions such as sputum or urine) or by health professionals (e.g., blood). Additionally, diagnostic tests can be categorized as in vitro diagnostics, which are required to go through rigorous review by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for approval, or laboratory-developed tests, which in most instances have only had the validation reviewed by the developer laboratories. Quality standards for testing human specimens in clinical laboratories are regulated through the Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments (CLIA). Ultimately, diagnostic tests used for Lyme IACI must be fit for purpose, whether it is for clinical diagnostics or research.

For some diseases or conditions, a diagnosis can be made through distinct clinical signs, observations, and other objective findings. Clinical diagnosis must rely on physician review of signs, symptoms, and available laboratory data. Symptom or health questionnaires can be used to collect self-reported information for screening (which may be part of the clinical diagnosis) or for research purposes, but they are rarely used on their own to make a diagnosis. In the research scenario, clinical trial participants may be enrolled using a set of symptom questionnaires and clinical evaluation scales that define the study inclusion criteria, and measure and track

outcomes as part of the study. Without a consensus definition for Lyme IACI, it is not possible to develop clinical diagnosis criteria or guidelines for the condition.

Diagnostic tests for Lyme IACI aim to discriminate this disease from other IACI with similar clinical presentations and possibly similar pathophysiology, a challenge compounded by the now near-universal exposure of humans to SARS-CoV-2. New approaches for Lyme IACI diagnosis that can achieve this differentiation will likely rely on identification of biomarkers that account for the potential impact of concurrent or sequential co-infections, such as markers of autoimmunity or immune dysfunction that may be unique to Lyme IACI and are altered by co-infections. Biomarkers are observable and measurable characteristics that can indicate pathology or response to an intervention (Califf, 2018). Biomarkers could have potential for diagnostic (identify cases) or prognostic (identify those individuals at highest risk) use and can sometimes be obtained from minimally invasive biological samples (e.g., serum, urine, oral, or nasal swabs) but may require more challenging and riskier samples (e.g., tissue biopsies, cerebrospinal fluid). Readily available and easily obtained specimens that do not require highly specialized personnel or equipment will be the most valuable in research to identify Lyme IACI biomarkers and also in the translation of these discoveries to practical diagnostic assays, as accessibility considerations can enable broader participation in research, especially in multi-center trials. Individuals with Lyme IACI also often seek care at primary care clinics and may not always have access to larger medical centers where complex tests are carried out. Development of an FDA-cleared in vitro diagnostic test can facilitate adoption of a standardized diagnostic. Laboratory-developed tests are not transferable from one study site to another without a complete re-validation at each new site. In addition, trial results will likely be more useful if the study participants were characterized using a single test for which clinical validity was endorsed by a neutral third party such as the FDA.

Researchers need to approach the development of diagnostic tests for Lyme IACI cautiously given the lack of knowledge on both the pathogenesis of these IACI and Lyme IACI-specific biomarkers, particularly with laboratory-developed tests that are not subject to the extensive regulatory oversight that the FDA exercises over in vitro diagnostic tests.8 Less oversight on

___________________

8 In 2024, the FDA finalized a new rule that would phase in laboratory-developed tests under a similar level of regulatory oversight as in vitro diagnostics, including requirements for quality compliance and pre-market review. However, this is a 4-year phase-in process where enforcement actions on quality and review begin in stage 3, and at the time of this report’s publication, there have been legal challenges to the regulatory authority of the FDA to enact and enforce the rule (Aaron et al., 2024). See Ass’n for Molecular Pathology v. U.S. Food & Drug Admin., Nos. 4:24-CV-479-SDJ & 4:24-CV-824-SDJ (E.D. Tex. Mar. 31, 2025).

laboratory-developed tests thus far opens the possibility that inadequately validated tests that produce unreliable results might be used, which would then become a confounding factor in the participant enrollment, stratification, and data analysis of clinical trials (e.g., uncertainty about whether a given participant actually had an initial Borrelia infection).

Summary of Current Evidence

From the scoping review, the committee highlighted opportunities for further investigation based on promising findings and gaps in the existing literature. The committee’s summary of current approaches reported from in vivo studies is summarized below. Some studies briefly mention examples of laboratory tests that have been used as part of the diagnosis without providing a comprehensive list of these tests. In the findings below, details on laboratory tests used in diagnosis are only noted if available.

Since there are no validated diagnostic tests or methods for identifying Lyme IACI, the committee broadened the inclusion criteria for full-text review of diagnosis-related research compared with that for the treatment- and mechanism-related publications in order to capture potentially promising observations that could be considered for future research directions. As a result, case studies and case reports related to potential diagnosis applications were included for review. The review included publications on the development of symptom surveys and clinical scoring models for categorizing the condition. Objective biomarkers can be an important component in the diagnosis of Lyme IACI, together with careful clinical assessment and patient history. Thus, the review also included studies that assessed and correlated objective findings with symptoms reported by study participants, with the acknowledgement that research on potential disease mechanisms may uncover promising diagnostic biomarkers, and vice versa.

In all, 27 full-text articles related to the diagnosis of Lyme IACI were included in the scoping review (Table 2-4). Of these, only one study was focused on the pediatric population, and three studies included both adults and children. The diagnosis approaches or methods are categorized into three groups: questionnaires or clinical evaluation scales, direct detection, and indirect detection.

There are five publications of symptom questionnaires: two of these evaluated the same Multiple Systemic Infectious Disease Syndrome questionnaire as a clinical diagnostic instrument (Citera et al., 2017; Horowitz and Freeman, 2018), one documented the use of the Post-Lyme Questionnaire of Symptoms as a research tool to differentiate between individuals who developed PTLDS and those who have not (Aucott et al., 2022), one assessed the General Symptom Questionnaire (GSQ-30) as a tool to reflect symptom burden and track changes over time (Fallon et al., 2019), and

| Study | Description | Study size | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sample type | Biomarker type | Test | Control | |

| Symptom Questionnaires or Clinical Evaluation Scales | ||||

| Questionnaire | ||||

| Not applicable (longitudinal prospective study for risk of developing PTLDS) | 243 adults with history of Lyme disease | 49 adults without history of Lyme disease | ||

| Not applicable Study 1: evaluate use of symptom questionnaire to identify symptoms reported by patients currently being treated for Lyme disease Study 2: validate use of symptom questionnaire in capturing health status of self-identified Lyme disease patients Study 3: validate use of symptoms questionnaire in distinguishing patients currently being treated for Lyme disease | Study 1: 537 individuals (mean age, 45) currently being treated for Lyme disease Study 2:2 782 individuals (mean age 50) self-identified with active symptoms of Lyme disease Study 3: 236 individuals (mean age 47) currently being treated for Lyme disease (subset from same cohort as Study 1)3 | Study 1: none Study 2:4 217 individuals (mean age 53) self-identified as healthy Study 3: 568 individuals (mean age 49) self-identified as healthy (did not reuse cohort from Study 2 control group) | ||

| Not applicable (use of existing objective treatment response measurement tools [Short Form 36 Functional Status Questionnaire, Zung Anxiety Scale, Beck Depression Inventory, Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale, Wechsler Memory Scale, Controlled Oral Word Association Test]) | 23 adults with previously diagnosed Lyme disease, treated between 4 to 16 weeks with intravenous antibiotics, and persistent cognitive symptoms | None | ||

| Not applicable (development of a patient-reported measure of symptom burden) | PTLDS: 124 adults Early Lyme disease: 94 adults | Depression: 36 adults Traumatic brain injury: 51 adults Healthy control: 37 adults | ||

| Study | Description | Study size | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sample type | Biomarker type | Test | Control | |

| Not applicable (patient symptom survey and retrospective chart review) | Medical records from 200 adults with history of Lyme disease based on clinical findings and/or laboratory testing, and experience persistent symptoms after prior antibiotic treatment5 | None | ||

| Clinical evaluation scale | ||||

| Not applicable (retrospective chart review) | Medical records from 100 patients (mean age 38, range 6–89) with history of Lyme disease based on CDC’s 2011 case definition and documented psychiatric findings | None | ||

| Not applicable (developing statistical model of objective outcome measures to characterize and monitor symptom severity, using existing tools [Short Form 36 version 2, Fatigue Severity Scale, Patient Self-report Survey for the Assessment of Fibromyalgia, Neuro-QoL Cognition Function SF v2.0, Neuro-QoL Fatigue SF v1.0, Neuro-QoL Sleep Disturbance SF v1.0, Neuro-QoL Anxiety SF v1.0, Neuro-QoL Ability to Participate in Social Roles and Activities SF v1.0, Neuro-QoL Emotional and Behavioral Dyscontrol SF v1.0, Neuro-QoL Positive Affect and Well-Being SF v1.0, Neuro-QoL Satisfaction with Social Roles and Activities SF v1.1]) | Development cohort: 15 adults with PTLD symptoms Validation cohort: 10 adults with PTLD symptoms | Development cohort: 14 adults recovered from Lyme disease Validation cohort: 13 adults recovered from Lyme disease | ||

| Study | Description | Study size | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sample type | Biomarker type | Test | Control | |

| Not applicable: analysis of a subset from previous published prospective study of adults with erythema migrans | 37 adults with EM | None | ||

| Direct Detection | ||||

| Molecular detection | ||||

| Autopsy tissues from brain, heart, kidney, liver | Whole cell pathogen, alginate exopolysaccharide | 1 adult (case report) with no history of EM or tick bite and negative on thorough evaluation for Lyme disease, received empirical treatment for Lyme disease6 | None | |

| Urine | DNA | 97 adults with documented EM, completed recommended antibiotics treatment, and have persistent symptoms | 62 healthy adults from same regions with no history of Lyme disease | |

| Culture | ||||

| Blood | Live pathogen | 47 individuals with prior diagnosis of Lyme disease, between 6 weeks to 6 months of intravenous antibiotics, and persistent symptoms7 | 23 individuals with unspecified chronic illnesses from regions not endemic for Lyme disease | |

| Study | Description | Study size | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sample type | Biomarker type | Test | Control | |

| Xenodiagnosis | ||||

| Skin | Live pathogen |

26 adults

|

10 adults with no history of Lyme disease and seronegative by commercially available C6 ELISA | |

| Indirect Detection | ||||

| Autoimmune markers | ||||

| Serum | Anti-annexin A2 antibody | 303 | 94 healthy individuals without history of autoimmune disease (not screened for prior history of Lyme disease) | |

| Serum | Antiphospholipid antibody |

106 individuals (mean age 43) with suspected, diagnosed, or treated persistent symptoms with history of positive Lyme disease immunoassay11 |

None | |

| Study | Description | Study size | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sample type | Biomarker type | Test | Control | |

| Serum | Anti-neural antibody |

19 individuals (mean age 42 ± 13.9) as a subset from a previously published study, with history of Lyme disease and objective memory impairment12

|

11 individuals previously treated for early Lyme disease (localized or disseminated) with no persistent symptoms after treatment 20 healthy individuals with no history or serologic evidence of Lyme disease | |

| Pathogen-specific markers | ||||

| Serum, cerebrospinal fluid | Anti-borrelial antibodies | 13 individuals with history of Lyme disease and persistent fatigue after antibiotic treatment | 12 individuals with unexplained persistent fatigue without history of B. burgdorferi infection or treatment for Lyme disease | |

| Serum | Anti-borrelial antibodies | See above. | See above. | |

| Serum | Anti-borrelial antibody |

129 adults with Lyme disease and persistent symptoms after antibiotics treatment, same cohort as previously published trials on extended antibiotics treatment13

|

None | |

| Study | Description | Study size | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sample type | Biomarker type | Test | Control | |

| Other immune markers | ||||

| Serum | C-reactive protein, serum amyloid A level |

90 individuals with early to late Lyme disease, same cohort as previously published trials on extended antibiotics treatment14

|

67 healthy individuals (mean age 47.6±12.1) without history or serologic evidence of Lyme disease from the same geographic regions. 68 individuals (mean age 53.0±14.9) with history of Lyme disease but no persistent symptoms after completion of treatment. |

|

| Study | Description | Study size | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sample type | Biomarker type | Test | Control | |

| Blood | T cell proliferation from B. burgdorferi whole cell stimulation | 17 individuals (age range 10–65) with clinical history consistent with Lyme disease (EM or history of tick bite preceding symptoms of Lyme disease), seronegative at time of initial diagnosis, persistent symptoms after antibiotics treatment. | 18 individuals (age range 16–72) with similar clinical history as the test group except seropositive by ELISA. 17 healthy individuals with no history of Lyme disease or other rheumatic or immune disorders. | |

| Serum | Interferon alpha | See above. | See above. | |

| Plasma | C3a and C4a complement protein | 445 individuals (mean age 45.1±15, range 7–86) with positive western blot and persistent symptoms lasting more than 3 months15 | 29 healthy controls (mean age 45.3±17, range 8–75)16 11 adults (mean age 43.3±19, range 18–68) with systemic lupus erythematosus 6 adults (mean age 57.2±8, range 51–72) with AIDS | |

| Blood | CD57 | 1 adult with history of tick bite, no recollection of EM, symptoms consistent with Lyme disease, and positive western blot. | None (case report) | |

| Study | Description | Study size | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sample type | Biomarker type | Test | Control | |

| Molecular biomarker | ||||

| Serum | Metabolite signature |

Cohort 1, archived serum samples from patients presenting with EM and skin culture positive for B. burgdorferi:17

|

Cohort 1, archived serum samples from patients presenting with EM and skin culture positive for B. burgdorferi:

|

|

| Study | Description | Study size | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sample type | Biomarker type | Test | Control | |

| Stool | Microbiome signature | 87 individuals with PTLDS (mean age 48.3±14.7) from an existing cohort19 |

292

|

|

| Neuroimaging | ||||

| In vivo | Translocator protein (TSPO) level using [11C]DPA-713 radiotracer and PET scan | 12 adults with history of probable or confirmed Lyme disease based on CDC’s 2011 case definition, completed recommended antibiotic treatment, and experience PTLD symptoms of any duration. Exclusion criteria for control group also apply to the test group. | 19 healthy adults (historic control from two prior studies) in stable health, without recent infections other than Lyme disease; history of neurological condition not associated with Lyme disease; clinical abnormality on blood, urine, or electrocardiogram screening; substance abuse; contraindication to imaging; or use of benzodiazepine, anti-inflammatory medication, or minocycline | |

| Study | Description | Study size | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sample type | Biomarker type | Test | Control | |

| In vivo | Brain structure and function using technetium-99m SPECT | 183 individuals with exposure or risk of exposure to deer ticks in a Lyme disease endemic region, and have at least two of the following symptoms: unexplained fatigue, musculoskeletal pain, neurocognitive dysfunction for at least 6 months20 | None | |

| In vivo | Brain structure and function using technetium-99m SPECT | 19 individuals with a diagnosis of chronic Lyme disease (mean age 35.6, standard error 2.8)21 | 14 individuals (mean age 46, range 29–47) with recent SPECT imaging in the same department and chief diagnosis was not Lyme disease22 | |

| In vivo | Brain structure and function with fMRI and diffusion tensor imaging | 12 adults with PTLD and no comorbidities having symptom overlap with PTLD (fibromyalgia, chronic fatigue syndrome, major psychiatric disease excepting non suicidal depression manifesting after Lym disease), malignancy, autoimmune disease) and no history of Lyme disease vaccine, sleep apnea, cirrhosis, hepatisis B/C, HIV, dementia, cancer (in the past 2 years), substance abuse (illici or prescription drugs, alcohol) | 18 healthy adults without comorbidities having symptom overlap with PTLD and no past diagnosis of Lyme disease e | |

| TOTAL = 27 | ||||

1 The three studies reported in this publication did not use the same symptom scales. Differences between the symptom scales used are detailed by the authors in the article.

2 84.1% of the self-identified Lyme disease patient group met or partially met the case definition for Lyme disease surveillance based on the 2011 CDC criteria.

3 This study reported some of participants have documented positive laboratory results as part of their Lyme disease diagnosis using tests that include immunofluorescent antibodies, polymerase chain reaction, and an IgG/IgM immunoblot. Not all these tests are FDA cleared, and accuracy likely varies among them.

4 30% of self-identified healthy cohort met or partially met the case definition for Lyme disease surveillance based on the 2011 CDC criteria.

5 This study reported some of participants have documented positive laboratory results as part of their Lyme disease diagnosis using tests that include immunofluorescent antibodies, polymerase chain reaction, IgG/IgM immunoblot, and enzyme linked immunospot assay. Not all these tests are FDA cleared, and accuracy likely varies among them.

6 See publication for thorough clinical history for this case report.

7 Lyme disease was diagnosed clinically, though ELISA and immunoblots with IgG and IgM were reported for some individuals.

8 High C6 antibody level defined as having C6 antibody index >3 for at least 6 months after completion of antibiotics treatment.

9 See Aucott et al., 2022.

10 See Rebman et al., 2017.

11 Referred to as ‘purported chronic Lyme disease’ in the publication. Immunoassays for Lyme disease included ELISA and immunoblots with IgG and IgM.

12 See Fallon et al., 2008.

13 See Klempner et al., 2001.

14 See Klempner et al., 2001.

15 See publication for detailed characterization of study participants and treatment.

16 Additional clinical history or characteristics for this control group were not described in the publication.

17 See Weitzner et al., 2015.

18 See Aucott et al., 2016.

19 Samples are from the SLICE cohort, see Rebman et al., 2017

20 Age of the study participants were not included in the publication.

21 Specific criteria for the chronic Lyme disease diagnosis were not described in the publication.

22 Past history or prior test results for Lyme disease, if performed, is unknown.

NOTE: AIDS = acquired immunodeficiency syndrome; CD = cluster of differentiation; ELISA = enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay; EM = erythema migrans; fMRI = functional magnetic resonance imaging; ICU = intensive care unit; PET = positron emission tomography; PTLD = post-treatment Lyme disease; PTLDS = post-treatment Lyme disease syndrome; QoL = quality of life; SPECT = single-photon emission computed tomography.

one examined the use of a modified Fibromyalgia Impact Questionnaire to evaluate the functional impairment in PTLDS (Fallon et al., 1999). The range of applications reported for the symptom questionnaires is notable. Validation assessment has been described for GSQ-30, a PTLDS-specific instrument that was able to detect significant change in symptom burden that correlated with changes in functional impairment in relation to antibiotic therapy, but rigorous assessments have not yet been reported for two other symptom questionnaires (Aucott et al., 2022; Citera et al., 2017). However, given the current uncertainty in knowledge of disease mechanism, risk factors, and defined sets of symptoms, symptom questionnaires and clinical evaluation scales cannot be used as standalone diagnostic tools, and these publications were not further examined.

Four publications reported on the direct detection of B. burgdorferi by identifying live cells from blood samples or through xenodiagnosis (Phillips et al., 1998; Marques et al., 2014), by amplification of bacterial DNA in urine samples (Bayer et al., 1996), or by immunohistochemical imaging of intact cells and bacterial-derived exopolysaccharide in tissue samples (Sapi et al., 2019). While the last study was not conducted as diagnostic research, as it was conducted on autopsy samples of organ tissues, it does shed light on the types of samples that may be considered for development of future Lyme IACI diagnosis if the goal is to detect persisting pathogens. Xenodiagnosis is a unique method that, though unlikely to be widely adopted for routine clinical use, may be a useful tool in research studies to assess treatment response and shed light on pathogenesis mechanisms. A second clinical trial is underway, but its results have not yet been reported (NIAID, 2024).

Fourteen studies explored indirect detection methods which examined a variety of biomarkers. The majority of these were immune markers, including autoimmune antibodies (Greco et al., 2011; Jacek et al., 2013; Miller et al., 2024), antibodies specific to B. burgdorferi (Coyle et al., 1994; Fleming et al., 2004; Jacek et al., 2013), and other indicators of inflammation or immune activation (Dattwyler et al., 1988; Jacek et al., 2013; Stricker et al., 2002, 2009; Uhde et al., 2016). With the exception of three publications focused on anti-borrelial antibodies, there was no overlap in the potential diagnostic targets (i.e., no two independent studies reported on the same target). Three studies used single-photon emission computed tomography, functional magnetic resonance imaging, and diffusion tensor imaging to assess structural and functional differences in the brain of those with Lyme IACI (Donta et al., 2012; Marvel et al., 2022; Plutchok et al., 1999).9 One study used positron emission tomography with radiotracer to reveal higher level of the mitochondrial translocator protein (TSPO), a

___________________

9 See Box 3-2 in Chapter 3 for additional comments related to neuroimaging and Lyme IACI.

marker for in vivo immune activation in the central nervous system, in specific brain regions of patients experiencing persistent symptoms compared with a set of historical healthy controls (Coughlin et al., 2018). The last two studies of indirect detection methods sought to identify changes in the gut microbiome or serum metabolites that are unique in those with Lyme IACI compared with control groups (healthy volunteers, individuals who recovered from Lyme disease without long-term symptoms, intensive care unit patients) and could be used as a diagnostic signature (Fitzgerald et al., 2021; Morrissette et al., 2020). Despite the breadth of potential biomarkers explored, most of the published research were one-off reports of promising but exploratory approaches.

Biomarkers for diagnosis should be universally present in individuals with Lyme IACI and absent or distinguishable in individuals without Lyme IACI. These disease indicators are often connected with the pathophysiologic processes of the illness. Given the heterogeneity of this condition and implications that there may be distinct subgroups of the Lyme IACI population defined by different disease mechanistic pathways, as well as the potential for interactions between these pathways, it is unknown whether there can be a single biomarker or one group of biomarkers that will be applicable for the entire Lyme IACI population. Consider, for example, the strength of the evidence for attributing persistent symptoms to a Borrelial infection may vary among different individuals even if that is the true root cause of their illness. These variables, such as factors that influence the host immune response (see Chapter 1) or other aspects of disease pathogenesis stemming from the original infection to cause these symptoms, likely also affect the production and level of these biomarkers. It is possible that there are different biomarkers that, together with detailed clinical characteristics, can identify and differentiate subgroups of Lyme IACI. Future research to build on the existing findings or explore new approaches for diagnostics need to consider stratification of study participants or defining the enrollment criteria for a more granular focus to examine potential subgroup-specific criteria.