Addressing the Needs of an Aging Population Through Health Professions Education: Proceedings of a Workshop (2023)

Chapter: 5 Making It Happen with Implementation Science

5

Making It Happen with Implementation Science

Key Messages Made by Presenters

- Adopting an implementation science strategy requires identifying the contextual factors that either facilitate or challenge improvement of outcomes as well as the strategies that could be used to take advantage the facilitators and address the challenges. (Binagwaho)

- Health professions education should rest on sound educational strategies and pedagogies, and implementation science can be used to ensure that evidence-based approaches are effectively implemented into educational strategies, considering the local context as well as facilitators and barriers to change. (Thomas)

- Although the results of the service-learning study were encouraging, what was absent was the use of an explicit implementation science lens from the beginning. (Douglas)

This workshop, said Zohray Talib, the senior associate dean of academic affairs at the California University of Science and Medicine, has brought the concept of design thinking into the space of health professions education. During this workshop, she continued, speakers and attendees have heard from older adults about their lives and their needs, have identified a mismatch between the care needs of older adults and the health care workforce that will serve them, and have explored a number of “fantastic examples” of innovative programs and models that are making a difference. The next step, she said, is to take these best practices and expand, scale, and adapt them in new contexts. Doing this successfully will require using implementation science.

In this session of the workshop, speakers described implementation science and how it can be used to promote the uptake of evidence-based practices to improve health professions education and training and, in turn, improve and strengthen the workforce to care for older adults.

THE IMPORTANCE OF IMPLEMENTATION SCIENCE

The process of translating research findings into health outcomes is not automatic, said Agnes Binagwaho, a former vice chancellor and co-founder of the University of Global Health Equity, Partners in Health, Rwanda. Using the example of medical products, she said the process starts with basic science discoveries. Once promising evidence has been found, funds—usually private—are allocated toward the development and manufacture of medical products that can improve health outcomes. However, if the products do not reach the population, health outcomes will not improve. For example, vaccines were quickly developed in response to the COVID-19 crisis, but vaccination rates are low in many parts of the world. In most areas, the well-educated and higher-income populations are more likely to be vaccinated, and those most vulnerable—including the elderly and health professionals—were not prioritized. In addition, thousands of vaccine doses expired in developed countries while people in developing countries could not access them. Implementation science is critical for making sure that research discoveries reach the intended target and have a positive impact, she said.

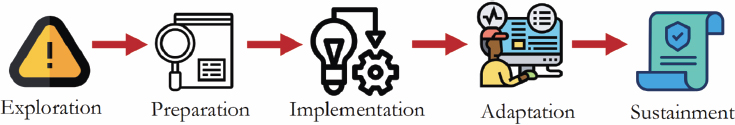

Binagwaho gave a formal definition of implementation research: “Implementation research is defined as the scientific study of the use of strategies to adopt and integrate evidence-based health interventions into clinical and community settings to improve individual outcomes and benefit population health.”1 There are various frameworks to describe implementation science, she said; the framework in Figure 5-1 describes it as taking place in five phases.

The first step is exploration, she said; in this phase, stakeholders explore the contextual factors and the problem at hand. The second phase, preparation, involves selecting evidence-based interventions that are appropriate for the local context. Collaboration with different stakeholders is essential to ensure a realistic approach as, Binagwaho said, no sector can solve the problem alone. In the third step, implementation, a strategy is selected to ensure coverage of the intervention. The adaptation phase requires monitoring and evaluation to understand when, how, and why to adapt the intervention and the strategy in order to get the expected results. Finally, in the sustainment phase, stakeholders decide how to ensure

___________________

1 https://grants.nih.gov/grants/guide/pa-files/PAR-19-274.html (accessed March 7, 2022).

SOURCE: Binagwaho presentation, November 17, 2022.

long-term implementation and sustainable outcomes through integrating the intervention into systems and policies.

Adopting an implementation science strategy requires identifying the contextual factors that either facilitate or challenge the improvement of outcomes as well as the strategies that could be used to take advantage of the facilitators and address the challenges. Taking the example of emerging health needs in an aging population, Binagwaho said that one challenging contextual factor is that longer lifespans decrease the incidence of deaths from communicable, maternal, neonatal, and nutritional diseases while increasing the incidence of deaths from non-communicable diseases. Strategies to address this challenge could include health awareness and prevention programs as well as long-term and end-of-life care. An implementation science approach also identifies facilitating contextual factors, Binagwaho said. For example, there is a strong community health worker program in Rwanda; strategies to take advantage of this strength could include having these workers conduct follow-ups for patients with chronic diseases or distributing drugs at the community level.

Once an intervention is implemented, its success must be evaluated across various dimensions. Binagwaho adapted Proctor et al.’s (2011) proposed implementation outcomes list to include:

- Appropriateness

- Acceptability

- Cost-effectiveness

- Coverage

- Effectiveness

- Equity

- Feasibility

- Fidelity

- Sustainability

She further emphasized that it is important to evaluate these outcomes in relation to each other. For example, a program that is cost-effective could be highly inequitable.

There is a need to build implementation science capacity at all levels of the health system, Binagwaho said. A country with a health workforce that is capable of doing research and implementing known evidence-based interventions will have a strong health system and will be ready to respond to new challenges, including the health needs of an aging population. Stakeholders who should be knowledgeable about implementation science include health care workers, systems managers, policy makers, and researchers. There is a strong economic argument for building implementation science capacity, she said: building capacity facilitates the use of all known evidence-based interventions and implementation strategies. This is key, she said, in strengthening health systems and ultimately contributes to economic development. In addition, there is a cyclical relationship between economic development, poverty reduction, and health. As the population becomes healthier, the production capacity of the country increases, which in turn promotes economic development and poverty reduction, leading to improved health.

THE ROLE OF IMPLEMENTATION SCIENCE IN HEALTH PROFESSIONS EDUCATION

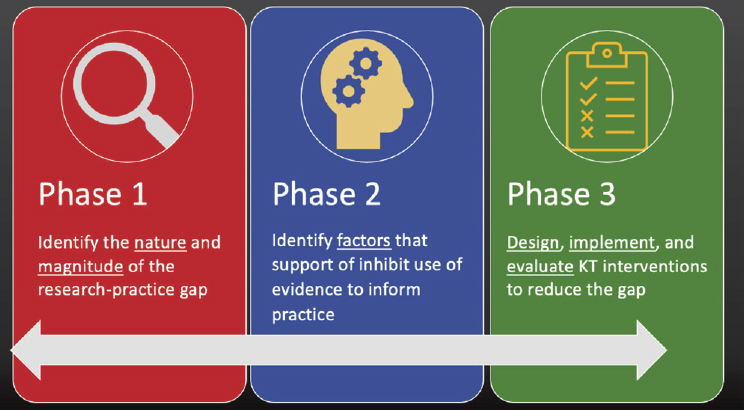

Aliki Thomas, an associate professor at the School of Physical and Occupational Therapy and an associate member of the Institute of Health Sciences Education, Faculty of Medicine and Health Sciences, McGill University, shared her perspective on implementation science and how it can be used to improve health professions education. Thomas described the process of translating research into practice as occurring in three phases (Figure 5-2). Phase 1 involves identifying the nature and the magnitude of the research–practice gap; that is, to what extent do current educational practices vary from best practices supported by evidence? Phase 2 identifies factors that support or inhibit the use of evidence to inform practice; these factors may be at the individual, organizational, or systems level. For example, individual factors could be attitudes towards best practices or the skills to offer them; organizational factors could be the resources available to implement best practices; and systems factors could be accreditation standards that either facilitate or present a barrier to evidence-based educational practice. In Phase 3, interventions to reduce the research-practice gap are designed, implemented, and evaluated. In this step, Thomas said, it is critical to consider a number of questions:

- What do you want your intervention to achieve and for whom?

- What constitutes the intervention?

- How do you propose the intervention will work?

- How will you deliver the intervention?

- How will the intervention be evaluated? What does success look like?

SOURCE: Thomas presentation, November 17, 2022.

Thomas described how implementation science could be applied specifically to the challenge of preparing the health professions workforce to meet the needs of an aging population. In Phase 1, the goal would be to document the current educational strategies used in health professions education and determine how these differ from what is recommended in the literature. This could be accomplished through examining accreditation reports, reviewing evidence on the learner outcomes of interest, and mapping current practices to the existing evidence on the specific educational strategy. Phase 2 would involve exploring the perceived facilitators and barriers in implementing a new educational strategy or pedagogy. Methods could include interviews, focus groups, or a survey of faculty; and the barriers and facilitators could include available resources, support from faculty or leadership, and community partnerships. Based on the first two steps, Phase 3 would involve designing interventions that take advantage of the facilitators and aim to overcome the barriers to the uptake of a new educational strategy. Designers could use frameworks such as the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research (CFIR) to guide this process. In the particular area of preparing the workforce to care for older adults, the barriers to address would likely include learner attitudes, the confidence of the faculty to teach the topic, and having limited time or resources to support teachers in their efforts to prepare learners. There are multiple strategies to address these barriers, she said, including faculty development, webinars, and stories or testimonials of successful implementation projects.

Health professions education should rest on sound educational strategies and pedagogies, Thomas said, and implementation science can be used to ensure that evidence-based approaches are effectively implemented into educational strategies, considering the local context as well as facilitators and barriers to change.

CASE STUDY: SERVICE LEARNING AS PEDAGOGY FOR CHANGING ATTITUDES

In this session, Natalie Douglas, a faculty member of communication sciences and disorders at Central Michigan University, presented her work measuring the impact of a service-learning project on students’ attitudes about working with older adults. This presentation was designed to frame the roundtable discussion taking place after Douglas’ remarks, said Thomas, who moderated the session. Douglas began by saying that she has long thought about implementation science from a research lens but had not considered how implementation science could be used to support the education she provides to her students. This service-learning project, she said, was not conducted with an implementation science lens; she expressed her hope that by the end of the workshop session, participants could help identify ways that implementation science would improve the implementation and outcomes of the project.

As other speakers have noted, students often have prejudiced and stereotypical attitudes about working with older people, Douglas said. She shared a quote from an undergraduate student:

Before arriving [to the nursing home], I pretty much thought I was going to a mental hospital. I thought the residents were going to be these hollow husks of a person, and I was going there to entertain them for a bit.

Ageist attitudes like this, she said, may steer students in health care professions away from working with older adults. To improve student attitudes in this area, Douglas and her colleagues developed a service-learning approach that combined classroom instruction with real-world experiences. Research demonstrates that these types of real-world experiences, designed to expose students to older adults, can have a positive impact on their attitudes. In addition, service learning is designed to be mutually beneficial to both the learner and the community or individuals the learner is serving and to provide opportunities for critical reflection.

The aims of Douglas’s study were to determine whether the attitudes of undergraduate students changed after a service-learning experience in which they engaged with older adults. Shifts in attitude were evaluated

using the Dementia Attitudes Scale and reflective journal entries. The study was rooted in the AAA framework (Mahendra et al., 2013), Douglas said. The first A stands for awareness; the experience was designed to emphasize the acquisition of knowledge and self-reflection on gaps in knowledge. The second A is application; during preparatory training, Douglas and her colleagues sought to develop interactional skills with older adults as well as develop reflective skills that could improve clinical practices in general. The third A stands for advocacy or attitude; researchers were interested in exploring whether and how attitudes shifted as students underwent these experiences.

This project involved 145 undergraduate students across two midwestern universities. The students were all majoring in communication sciences and disorders, and 23 percent reported having previous experience working with adults with dementia. The mean age of participants was 21.5 years, and 141 of the participants were female. Over the course of a semester, students spent between 15 and 30 hours interacting with individuals living with dementia in long-term care environments. Students engaged in a variety of activities, including conversation, activities related to the individual’s hobbies or interests, crafts, games, and sensory activities (e.g., holding a hand, combing hair). Students were trained in all of these activities prior to their interactions, including specific ways to communicate with patients with dementia, such as TimeSlips or using photos or gestures to communicate. Conducting the program required resources for classroom instruction, on-site coaching and support, partnerships with communities that wanted students to visit, and physical space for the students and older individuals to interact.

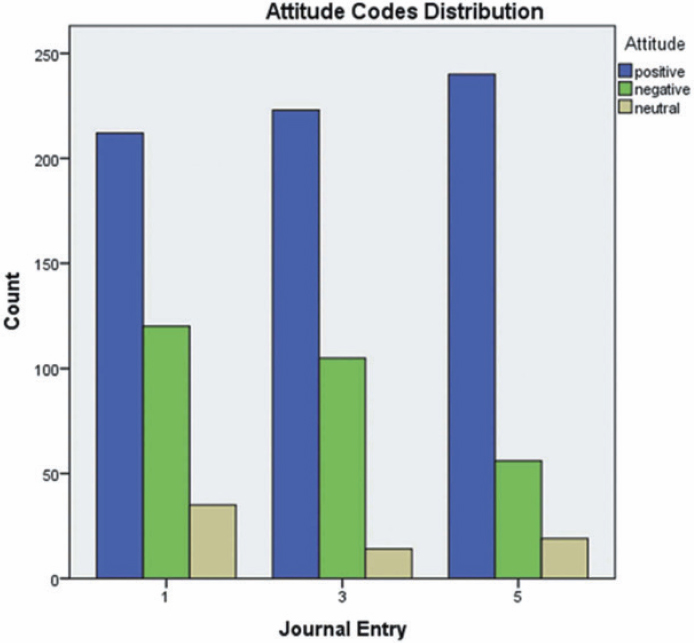

Douglas shared the results of the study. Students wrote journal entries over the course of the project, and the first, third, and fifth entries were coded for positive, negative, and neutral attitudes. As seen in Figure 5-3, the proportion of positive attitudes in journal entries increased as time went on, while the proportion of negative attitudes decreased. Results from the Dementia Attitudes Scale confirmed these attitude shifts, Douglas said.

In closing, Douglas again shared the earlier quote from a participating student, but this time included his final line:

Before arriving [to the nursing home], I pretty much thought I was going to a mental hospital. I thought the residents were going to be these hollow husks of a person, and I was going there to entertain them for a bit. I couldn’t have been more wrong.

SOURCE: Douglas presentation, November 17, 2022. Heuer et al. (2020), reprinted with permission.

Discussion

Although the results of the service-learning study were encouraging, Douglas said, what was absent was the use of an explicit implementation science lens from the beginning. Douglas and Thomas asked roundtable discussants to share their thoughts on using implementation science to systemically transform education, using both Douglas’s study as well as their own experiences as examples. Each panelist was asked to describe his or her own experiences with service-learning projects and to describe the facilitators and barriers that they encountered when implementing these projects.

Thomas began by asking Douglas to use an implementation science lens and describe any facilitators or barriers that were identified when implementing the project. Douglas replied that there were a number of logistical

barriers, including facility rules that required students to complete paperwork and medical testing before volunteering, finding the right point person in the care community, and finding times for visits that worked for both students and the care facility. An unexpected challenge, Douglas said, was the ethical difficulty of creating “beautiful relationships” that could only last for 15 weeks. A facilitator for both universities was the community engagement support each received from their institutions. The schools were applying for a community engagement classification, which created a high level of motivation to conduct this project. Another facilitator, Douglas said, was the relationships with the community care centers and the benefits that they saw from participating in the project. For example, some community care centers saw student participants as potential future employees.

Thomas asked other panelists to talk about their own projects and to describe the relevant facilitators and barriers. Toby Brooks, the assistant dean for faculty development at Texas Tech University Health Science within the Athletic Training Program, talked about his work in the graduate program on athletic training. Students in this program have the opportunity to work with patients across the age spectrum, and one challenge is educating the public and other health care professionals on their role in care. In recent years, he said, the program has focused on developing clinicians as educators and helping them acquire teaching skills at the same time as they acquire their clinical skills. Brooks divided facilitators and barriers into individual, organizational, and system-level determinants. Individual determinants include the formation and resilience of knowledge, skills, and abilities of individuals, and an individual and organizational determinant is the role of beliefs in the formation or development of practices. Brooks said that educating students with new knowledge and skills “doesn’t do any good” if their underlying beliefs remain unchanged. An organizational determinant is the impact of program culture on accountability and outcomes, and systems-level determinants are the factors specific to the profession of athletic training (e.g., third-party reimbursement and the job market). Brooks said that the practices of implementation science are a useful way to see if health professions educators are “moving the needle” and making a difference.

Kim Dunleavy of the Department of Physical Therapy at the University of Florida, who was also representing the American Council of Academic Physical Therapy, said there are a number of different service-learning opportunities at her institution. These include interprofessional home visits, a community walking program, low-income housing chair exercise classes, balance and falls activities at a senior center, adaptive gymnastics, and a pro bono clinic. Some of these activities focus on older adults, while others do not; as a result, not all students gain experience engaging with this population. Dunleavy considered the question of whether the service-learning

project model that Douglas described could be adapted for use in her community to improve learner attitudes toward working with older adults. Facilitators of this work would be the service-learning programs already in place, a number of existing classes related to the topic, and an established practice of encouraging reflective thinking in conjunction with service projects. Barriers might include the need for faculty supervision and faculty debriefing, challenges in integrating the model into existing coursework, and identifying a validated tool for capturing attitudes about working with older adults across the spectrum.

Dietitians work in a wide variety of settings and with a wide variety of populations, including many older adults, said Hannah Wilson, an assistant professor in the Department of Nutrition, Dietetics, and Exercise Science at Concordia College. At Concordia College, she said, it is a high priority to train students to be interested in working with this population and to be comfortable working in all types of settings. There are a variety of service-learning opportunities in both the undergraduate and graduate nutrition programs, including working with programs like Meals on Wheels. Facilitators of these kinds of opportunities, Wilson said, include a university-wide requirement for PEAKs (pivotal experiences in applied knowledge) and a graduate-level requirement for at least 1,200 supervised practice hours. There are also a number of barriers, she said, including a shortage of registered dieticians in older adult settings to serve as preceptors, a limited number of sites, the cost of testing and paperwork, and scheduling. The college has found creative solutions to overcome some of these barriers, such as using preceptors who are not dietitians and coordinating with nearby “competing” programs in order to find placements for all students.

CLOSING

In closing the workshop, Talib spoke on behalf of the Global Forum on Innovation in Health Professional Education’s co-chairs and members, saying the challenge of building a strong health professions workforce to meet the needs of a growing aging population is not a distant possibility. “It is already upon us,” he said, and it is time to use implementation science to take evidence-based approaches for strengthening the workforce and move them into day-to-day health professions education practice. Throughout this workshop, Talib said, he was reminded of a previous workshop that took a design thinking approach to explore stress and burnout in the health workforce. The idea was to bring design thinking—empathize, define, ideate, prototype and test—into the space of health professions education.

In reflecting upon that workshop, Talib said she believed that this workshop took a similar design thinking approach to the issues of educating learners and health professionals on caring for an aging population.

First, there was empathy. “We collectively brought a group of people together who are already naturally empathetic,” she said. “But also, we heard the voices of our older adults and the learners themselves to really empathize with the issue.” This is where the concept of design thinking begins, with the beneficiaries of our work front and center, she remarked. In the second part, the presenters defined quantitatively and qualitatively the status of the health workforce, the health system, and push and pull factors affecting the ability of health professionals to meet the needs of older adults. This led to then ideating and prototyping. “I think we’ve heard a great number of fantastic examples,” Talib said, which demonstrated the challenges facing health professionals trying to meet the needs of an aging population. The final step of a design thinking model is to test, but an additional element could be to disseminate.

There are a lot of available resources, Talib observed, and now is the time to access those resources or prototypes already in use in the educational health system and apply implementation science to establish best practices for moving forward in training health professionals to address the needs of an aging population through health professions education. With that final thought, Talib thanked speakers, panelists, and workshop participants and adjourned the workshop.

This page intentionally left blank.