Addressing the Needs of an Aging Population Through Health Professions Education: Proceedings of a Workshop (2023)

Chapter: 4 Addressing the Gap

4

Addressing the Gap

Key Messages Made by Presenters

- Opportunities for students are not available at all institutions, and students are not always inclined to voluntarily learn about older adults. (Brickman)

- The Dementia Friends program resulted in statistically improved attitudes among students about persons with dementia. (McCarthy)

- Age-friendly universities use a framework of ten principles that relate to the active engagement of older adults in campus life. (Moone)

- The Virtual Interprofessional Consultation Clinic sessions consist of an introduction to the process, multiple 5- to 8-minute patient assessments, and questions, followed by an interprofessional discussion and development of the clinical assessment note by the students/trainees without the patient present. (Hicks-Roof)

With a rapidly growing population of older adults, there is a pressing demand to expand and strengthen the workforce of health professionals caring for older adults. However, there are a number of challenges in doing so, including ageism, lack of opportunities to engage with older adults, and a lack of interest among many health professionals in working with older adult populations. In this workshop session, speakers presented details about innovative programs and initiatives that are addressing these challenges and building a strong health care workforce for older adults.

CHANGING ATTITUDES ABOUT WORKING WITH OLDER ADULTS

Lily Brickman, a recent graduate of the master’s program in food science and human nutrition at the University of Maine, spoke to workshop participants about her experience as a dietetic student working with older adults. Brickman said she had always wanted to be a dietitian and that after working in a nursing home she began to realize the importance of proper nutrition for older adults. In graduate school, she was given the opportunity to work as a graduate assistant under the Geriatric Workforce Enhancement Program. Part of her responsibilities was helping out with a course at the University of Maine on nutritional care for older adults. Brickman said that only four or five students enrolled in the course each semester that she worked on the course and that in the past semester no students were registered. After talking with her thesis advisor, Brickman decided to focus her masters’ thesis research on educating dietetic students about the nutritional concerns of older adults. The goals of her research were to examine the interest of dietetics students in working with older adults and to understand different academic programs’ needs for teaching dietetics students in this area. Brickman conducted two surveys, one of the food science and human nutrition students at University of Maine and another of the Nutrition and Dietetic Educators and Preceptors (NDEP) group, an organizational unit of the Academy of Nutrition Dietetics. NDEP consists of a wide variety of professionals, Brickman said, including educators, faculty, internship directors, internship preceptors, and program coordinators. The response rate to her surveys was low, she said, but there were still valuable insights gained.

Given the expected growth in the older adult population, the availability of opportunities for dietetics students to learn about older adults must be increased, Brickman said. Opportunities for students are not available at all institutions, and students are not always inclined to voluntarily learn about older adults. If offering full courses is not feasible, relevant content should be added into existing courses. It is also critical, she said, to educate credentialed dietitians and other nutrition professionals about nutrition in older adults and provide incentives such as continuing education credits. Registered dietitians need 15 continuing education credits each year; this is a great opportunity to reach these professionals, she said. Brickman expressed her hope that her research provides insight into student interest in learning and working with older adults as well as insight into the availability of older adult nutrition education at institutions across the United States. She emphasized that further research is needed regarding effective strategies for increasing student interest in working with older adults.

Jeannine Lawrence from the University of Alabama asked Brickman to reflect on her learning opportunities in the area of nutrition and older adults

and on what worked best for her as a learner. Brickman responded that in her nutrition/geriatrics classes, what was most beneficial were hands-on activities that allowed students to interview and speak with older adults about their health, their lifestyle, and what changes needed to be made. In the literature she reviewed for her thesis, Brickman said, research indicated that these types of hands-on experiences can improve health professions students’ interest in and attitude toward working with older adults; these experiences could include performing exams, using a simulation, or working with older adults on their mobility challenges. Such activities, Brickman said, are effective ways for students to gain an understanding of the challenges that older adults face and to change learner attitudes about working with this population. George, also a student, agreed that direct experience—with any population—is what often leads to interest in working in a particular area. Hazen said that as a nursing doctoral student, she had observed that Brickman herself became interested in working with older adults based on her personal experiences working in nursing homes. George said that older adults are often not particularly visible in our society, so opportunities to interact with older adults need to be made more readily available. Intergenerational relationships can be rich and meaningful, and not having the opportunity to build these relationships is a “huge loss” for everyone, George said. In addition, content about healthy aging needs to be integrated early and often into health professions education programs. George said that she is in her last year of medical school and has yet to take a course on healthy aging. She is currently developing a course herself; she said that it is essential for people who are passionate in this area to take actions that force changes. The course she is developing will be required, which she said is important because people often do not know what they are interested in until they learn more about it. Annette Greer, a researcher in interprofessional education at East Carolina University, noted that health professions curricula are often driven by what is on the licensing exam. If there are few or no questions about aging on an exam, the topic is unlikely to be covered in a curriculum. There is a need for national boards to value this population and to acknowledge that older adults are a population for which caregivers need specific education and training.

Katie Eliot of the Department of Nutritional Sciences at The University of Oklahoma Health Sciences Center asked Brickman and George to comment on the role of faculty and how they can serve as role models for students making decisions about career paths. Brickman responded that the faculty members at her school often share stories about their work—whether in community nutrition, clinical nutrition, or other areas—and about the impact their work has had on patients or community members. These stories, she said, are inspirational and have made her more certain about her career. George added that her focus is on palliative care and that

many of her early mentors were palliative care physicians who emphasized the humanity of patients and the importance of relationship. Once she began medical school, she said, she found that the focus was often on pathology rather than personhood. However, George said that she felt lucky to have found some faculty mentors centered on the human being rather than the disease. This is a major issue both in health professions education and in practice, she said, particularly among older adults who can feel that providers are focusing on their diseases rather than on them as individual people. Just as learners need exposure to older adults to know if they want to work in that area, George said, learners also need mentors to show them what is possible and to open their eyes to new perspectives.

ATTITUDES ABOUT MEMORY LOSS

Teresa McCarthy, a geriatrician and associate professor of medicine in the Department of Family Medicine at the University of Minnesota, and Teresa Schicker, a program manager of the Minnesota Northstar Geriatric Workforce Enhancement Program at the University of Minnesota, told workshop participants about a simple, effective intervention to increase awareness of dementia, and they explored how activities such as this could impact the future workforce. McCarthy said that as a clinical educator, she has been teaching geriatrics for many years to students from many health professions. Because more students have been required to participate in geriatrics rotations in recent years, she learned that many trainees have had absolutely no exposure to older people or dementia. She also uncovered a lot of misperceptions and ageism in the trainee group as well as a lack of empathy. McCarthy said she looked for a module or activity she could use to address this problem, and she came across the Dementia Friends program. This is a worldwide movement to develop age-friendly and dementia-friendly communities. The core component of the program, she said, is information sessions that use a “train the trainer” model; people who attend sessions can take a brief training and then take the content into their own communities. It is explicitly not an education session, McCarthy emphasized, but rather an information session by community members to community members. It consists of 60 minutes of scripted content that is proprietary but free to access. Sessions can be held in person or virtually, with up to 70 participants. The session focuses on five key messages about dementia:

- Dementia is not a normal part of aging;

- Dementia is caused by diseases of the brain;

- Dementia is not just about having memory problems;

- It is possible to have good quality of life with dementia;

- There is more to a person than his or her dementia.

Content is delivered in an “upbeat” and “comfortable” way, she said, with some individual activities to reflect on one’s perspectives on aging and dementia. Small group interactions and story telling allow the trainers to augment the content with their own life experiences, which really enhances the experience for learners. At the end, there are practical recommendations for effective communication with people with Alzheimer’s disease. McCarthy said that residents find the content interesting and helpful.

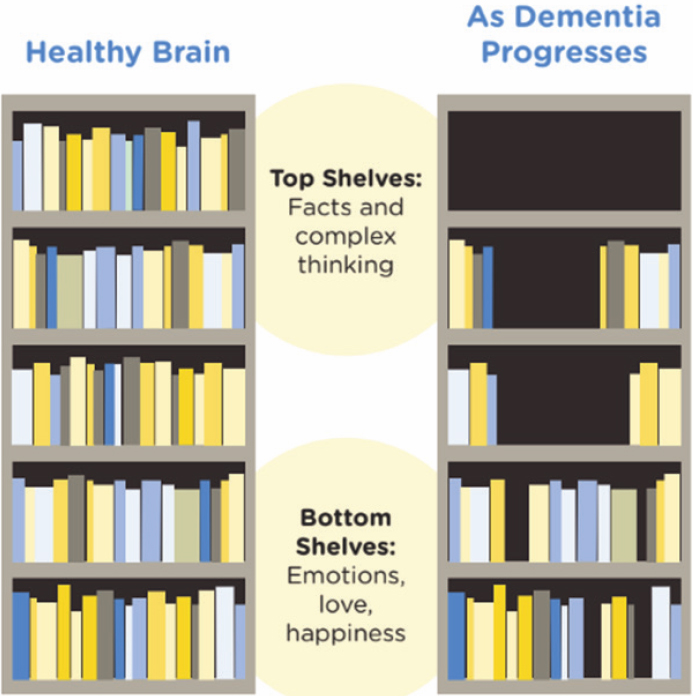

McCarthy showed an image that is used in the Dementia Friends training (Figure 4-1). The image is of two bookcases, one representing the healthy brain and one representing the brain of a person with progressing dementia. The bookshelf of the dementia patient has been “shaken,” which results in many of the books on the top falling off; these are analogous to facts and complex thinking. However, most of the books on the bottom stay

SOURCE: McCarthy presentation, December 8, 2022.

in place when shaken; these books are analogous to emotions, love, and sense of self. This is a great visual for understanding dementia, McCarthy said, and it provides context for how to interact with dementia patients.

McCarthy said that she used the Dementia Friends program with her students and wanted to evaluate what impact it was having on their attitudes and knowledge. She and her colleagues and students developed a study that surveyed around 100 students (medical, physical therapy, and pharmacy) before and after the program. The study used a validated 20-question scale called the Dementia Attitudes Scale (O’Connor and McFadden, 2010), which incorporates both knowledge about these diseases as well as a person’s comfort in interacting with dementia patients. The study found that the program resulted in statistically improved attitudes. The takeaway message, McCarthy said, is that a modest effort information session, delivered by students and lay people, increased knowledge and improved attitudes of health professional students towards those living with dementia.

Schicker provided details about how the Dementia Friends program was implemented at the University of Minnesota. She said that the program can be implemented in a variety of settings, including academic institutions, clinical settings, and community settings. Because of the train-the-trainer model, there have been several students who have “taken it and run with it,” she said. For example, a pharmacy student expanded it to the school of pharmacy, and several of that student’s colleagues have become trainers in turn. This is an excellent opportunity, Shicker said, for leadership development among health professions students. Thus far at the University of Minnesota, the program has trained 164 health professionals and community members and 825 health science students, with students coming from areas including nursing, physical therapy, mortuary science, education and human development, and public health. Next year, the program will be offered at primary care clinics around the state. Schicker stressed that Dementia Friends can be offered in informal settings such as student clubs, libraries, or classrooms and that it can be done online or in person. The program is proprietary, so it must be licensed through the U.S. or U.K. branch of Dementia Friends. Schicker urged stakeholders to hold sessions for interprofessional groups, although she noted that offering classes made up of a single profession is also an option.

The Dementia Friends program is a “pleasant experience for everybody involved,” Shicker said, and it is effective and building knowledge and empathy. Health professions students or practitioners can also recommend the program to their own patients or to caregivers of their patients. McCarthy commented on how Dementia Friends received some pushback early on from health professions faculty because the program presents very basic information and does not “dig deep” into pathology. However, the reason that the program resonates is its “gut impact,” which augments

the underlying content, as well as the way it provides an understanding of what it is like to live with dementia.

AGE-FRIENDLY UNIVERSITIES

There are a variety of age-friendly initiatives in a number of sectors, Rajean Moone said. For example, the World Health Organization and AARP have a framework for age-friendly communities, which allows people to assess a community and look for opportunities for a community to become more age-friendly. There are also efforts in the area of health systems, public health, businesses, creativity and the arts, and universities. All of these efforts come together under the umbrella of an age-friendly ecosystem; Moone said that institutions following age-friendly principles are making a commitment to the future and to moving the needle toward a more inclusive, supportive environment for an aging population. He also shared details about age-friendly universities and the principles that guide them. Age-friendly universities use a framework of 10 principles in areas that include online educational opportunities, a range of educational needs, health and wellness, research agenda, and second careers. All of these principles, he said, relate to the active engagement of older adults in campus life. One of the 10 principles, intergenerational learning, is aimed at facilitating the reciprocal sharing of expertise among learners of all ages. Intergenerational learning has a number of benefits, including exposing younger students to older adults and affecting their attitudes and beliefs about age and potential career paths.

To begin the process of helping the University of Minnesota (UMN) become an age-friendly university, a task force was created that was made up of individuals representing programs incentivized to work with older adults across campus. The task force started by sharing information. Moone explained that UMN is an enormous campus, so people are often siloed in their own areas. The task force enabled collaborative work across siloes. The task force conducted an assessment that looked at all departments and services, including arts, sports, enrollment, and employment. UMN used a tool created by the University of Massachusetts to inventory all programs and services and identify opportunities to build capacity. After the results of the assessment were presented to university leadership, the university president formed the Age-Friendly University of Minnesota Council and enrolled UMN in the global network.1 Enrollment in the network was the “easiest part” of the process, Moone said; the hardest part was finding the resources

___________________

1 The Age-Friendly University (AFU) global network is made up of institutions of higher education from around the world that have endorsed and acted upon the 10 AFU principles (Gerontological Society of America, 2023).

and time required to fully examine the university’s age-friendliness and making a commitment to change.

The UMN council is made up of a number of entities across campus, including the Alumni Association, the Women’s Club, the Office of Public Engagement, the Center for Healthy Aging and Innovation, the Osher Lifelong Learning Institution, the MN Northstar Geriatrics Workforce Enhancement Program, and the Retirees’ Association. Critical to the success of the program were community partnerships, Moone said. He is an appointed member of the Governor’s Council for an Age-Friendly Minnesota, which allows him to bring the university lens to the broader conversation about age-friendliness in the state. Community partnerships with UMN include partnerships with the state unit on aging health systems, area agencies on aging, home- and community-based service providers, AARP, senior housing, and the media. Moone said that one of the first major activities of the UMN Age-Friendly Council was establishing Age-Friendly University Day, which was dedicated to bringing life-long learners, retirees, and older Minnesotans to campus to converse about various topics relevant to their lives and to get them accustomed to coming to campus. There was a fireside chat with a former Minnesota Supreme Court justice and another with a former Minnesota Vikings player; these events excited and attracted older adults, Moone said. Media are a critical partner in these efforts, he said, for telling the story and getting the word out about the activities and initiatives at the university.

Moone asked breakout room participants to share questions or comments about their own experiences. Eliot commented that as a registered dietitian, she thinks about the way food systems and nutrition interact with the aging population. She asked Moone if the age-friendly initiatives at UMN involve this area. He responded that the Center for Nutrition Studies at UMN has largely been focused on nutrition in early life. However, the center has also been exploring the issue of food insecurity and older adults. UMN, in conjunction with the state, has been looking at rates of participation in the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program and has found that the rate of uptake in seniors is quite low compared with other populations. In response to this finding, the center has done targeted outreach to these communities. Moone said that his own lens on nutrition is quite different; he focuses on long-term care administrators and looks at innovations in nutrition (e.g., research on making food more appealing).

A workshop participant, Delfina Alvarez, asked Moone to comment on whether there is any collaboration or coordination between the age-friendly university network and the age-friendly community network. He responded by sharing one example of such collaboration. At the Age-Friendly University Day, AARP put on a presentation about age-friendly communities and gave people information about how they can get involved in these efforts.

Another way in which these two entities collaborate is by having a representative from the university help out when a community is undergoing the process of becoming age-friendly. For example, it can be helpful to have an academic voice present evidence to policy makers in discussions about allocating resources to age-friendly community initiatives.

Patrick DeLeon, a psychologist professor with the Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences, asked Moone how to institutionalize age-friendliness into universities rather than relying on the passion and dedication of individual faculty members. DeLeon noted that good ideas can easily come and go, depending on what the next generation of leaders wants to do. Moone responded that this is always a major consideration for him and that a key first step was getting the president to appoint an official council. This is now part of the university makeup, with bylaws to formalize the work. While bylaws can pigeonhole and restrain some efforts, they also contribute to stability and sustainability. The other consideration for sustainability, he said, is ensuring that there are resources available and processes in place to continue efforts when dedicated leaders leave. There is no magic answer, Moone said, but the most sustainable programs are those that rely on a collaborative of people rather than on a few individuals.

Kim Dunleavy with the Department of Physical Therapy at the University of Florida and representing the American Council of Academic Physical Therapy mentioned that her institution’s program pairs students with older adults in the community, which can lead to instances of ageism and mismatched expectations. Students are keen to help the adults with specific projects around their homes, she said, but they often do not see the social component as important. Jacqueline Kreinik, a nurse and subject matter expert at the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, said that the first stage of working with older adults is listening. Students need to set aside their expectations and focus on what matters most for the older adults. Health professions students, as well as practitioners, often want to jump in and make big changes to “be a hero,” but the older adult may want the person to simply listen or to lend a helping hand.

Maxwell described a program at her institution called Frailty-Focused Communication (Maxwell et al., 2022). Within this program, a workshop gives students a more in-depth understanding of the process of ageing, and there is a focus on communicating with older adults and using motivational interviewing skills to discuss issues deemed important by this population. Students are paired with an older adult in the community and then encouraged to develop a relationship and a friendship. A recent publication gives details on the program (Miller et al., 2022). Following up on Maxwell’s remarks, Jennifer Cabrera, a workshop participant, agreed that communication can be difficult between younger students or residents and older adults. She noted that older adults can get “left behind” because they

cannot keep up with the pace and that getting younger residents to sit and listen to an older patient for a few minutes can be a real challenge. Moone responded by saying that a pivotal part of his experience was going to undergraduate school on a campus with a nursing home. Most students volunteered or worked at the home at some point, and being able to build relationships, relate to other people, and build empathy are part of the critical “soft skills” of education. The pinnacle of geriatrics, Moone said, is helping health professions students build these types of critical skills so that they are able to listen to their patients and discover what matters.

VIRTUAL INTERPROFESSIONAL CONSULTATION CLINIC

Kristen Hicks-Roof, an associate professor in the Department of Nutrition and Dietetics at the University of North Florida, told participants about how she and her colleagues developed the Virtual Interprofessional (VIP) Consultation Clinic. It began, she said, with an interprofessional education series (IPES), which consisted of discussion and education sessions that focused on topics including communication, role responsibility, and team-based care. Participants included physical therapy residents, occupational therapy residents, family medicine residents, and dietetic interns; they met in a virtual environment in the years before this became common during COVID-19. IPES used hypothetical case examples to guide discussions, Hicks-Roof said, but numerous trainees participants requested real-life interactions with patients. Based on this and other feedback, the VIP Consultation Clinic was developed.

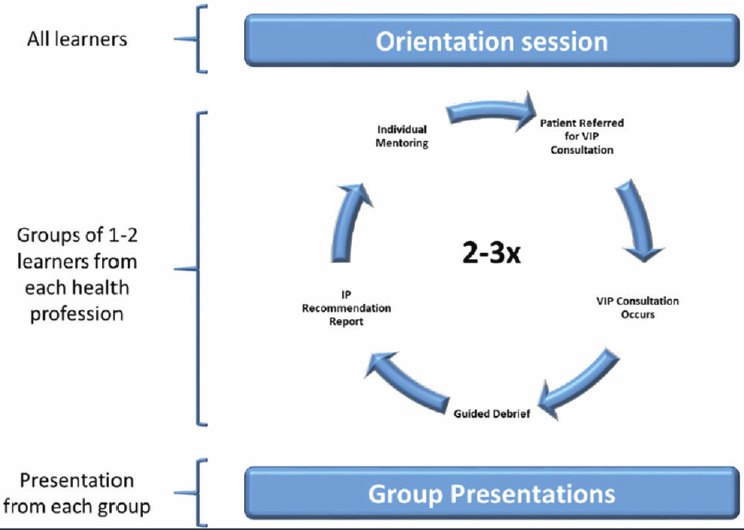

The VIP experience (Figure 4-2) begins with an orientation session focusing on roles and responsibilities. Hicks-Roof described research showing that if health professionals are not aware of what other health professionals actually do, they are less likely to refer patients to them or work together. In the orientation participants are taught about who other health professionals are, how they are educated, and where and how they work. This facilitates greater understanding and respect among the group, she said. After orientation, groups of learners participate in VIP sessions with patients. These sessions consist of an introduction to the process, multiple 5- to 8-minute patient assessments, and questions, followed by an interprofessional discussion and development of the clinical assessment notes without the patient present. Participating residents are from a range of disciplines, including physical therapy, occupational therapy, family medicine, nursing (D.N.P.), dietetics, and clinical mental health counseling. Patients are usually referred, and they are paid $75 for their participation. The program does not specifically recruit older adults as patients, but many participants are older, she said.

VIP participants are surveyed after the conclusion of the program, and Hicks-Roof presented several findings based on these surveys. First, there

SOURCE: Hicks-Roof presentation, December 8, 2022.

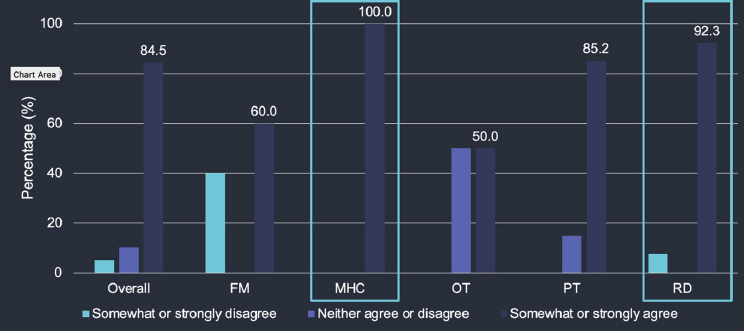

is a strong perceived positive impact on future interprofessional collaborative practice (Figure 4-3). This impact is particularly strong among mental health counselors and registered dietitians; Hicks-Roof noted that these two groups are newer to the world of interprofessional training. Second, most participants were more likely to refer to the other professions after the program than before. Again, the impact was greatest in the areas of nutrition and mental health, which Hicks-Roof noted are of critical importance for the health of older adults.

There were many advantages of the VIP clinic program, Hicks-Roof said. Learners have an opportunity to train on virtual technology and telehealth delivery and are exposed to older adults. Learners can participate in real patient assessments and are able to discuss and reflect on the assessments with an inclusive group of professionals. At the same time, the patients gain access to a wide variety of expertise in one clinic visit, which is quite uncommon. The program can be integrated into resident and intern schedules and competencies, Hicks-Roof said. The challenges associated with the program include recruitment of patients, scheduling VIP consults, ensuring continuous care for patients, and technical issues in the virtual

SOURCE: Hicks-Roof presentation, December 8, 2022.

environment. The technical issues are a particular problem when working with older adults, she said, who sometimes have more trouble navigating virtual visits.

Hicks-Roof asked breakout group participants to share their thoughts and questions. Greer asked how learner competencies and patient health outcomes are measured. Hicks-Roof responded that learners are given pre- and post-surveys with both quantitative and qualitative measures. Patients participate in only two VIP clinics, so there is less information gathered on them and their experience. Hicks-Roof said it would be helpful to follow patients over a longer period to see whether and how the experience affects their care. She posited that one benefit of participation for patients is simply exposure to other types of health professionals, and she suggested that patients may in the future ask their primary providers for referrals based on their experiences. Kolasa added that this exposure goes both ways—health professionals participating in the VIP clinic gain exposure to older adults and get experience caring for this population. Greer commented that the National Academies of Practice has developed interprofessional telehealth competencies; these would be useful for measuring the impact of the VIP program for learners, she said. In addition, she suggested that integrating the VIP clinic with a patient’s primary care provider could make it possible to track metrics and health outcomes (e.g., if a patient’s diabetes markers improve after participation). Hicks-Roof agreed with Greer’s concerns and said that a long-term vision is to create an embedded hybrid clinic within the family medicine residency program, which could address the concerns about measuring and tracking patient health outcomes.

Hartley noted that the VIP program is grant-funded and asked Hicks-Roof to comment on the value and sustainability of the program. Hicks-Roof responded that part of the reason for hoping to move to an embedded clinic in the family medicine program is to ensure the sustainability of the program. The idea, she said, would be for patients to be seen in person by family medicine practitioners in addition to participating in an interdisciplinary virtual session with other professionals. This could help with the continuity of care for patients as well as with sustainability. Hartley said that integrating the program into an existing care program could also potentially help with the reproducibility and scalability of the VIP program. Nina Tomasa, a workshop participant, closed the session by emphasizing that patients are an integral part of the care team and that the VIP model ideally welcomes patients in as part of the interprofessional collaboration.

CONTINUING PROFESSIONAL DEVELOPMENT IN GERIATRIC CARE

Josea Kramer, the associate director for education/evaluation of the geriatric research, education and clinical center (GRECC) at the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) Greater Los Angeles Healthcare System, said that GRECCs are congressionally mandated centers of excellence that were established in the mid 1970s to meet the emerging “age wave” of older veterans by advancing geriatrics and gerontology. Each of the 20 GRECCs has a wide portfolio of clinical and research activities; the education component includes clinical training and fellowships across a variety of health professions as well as continuing education.

Kramer began the Geriatric Scholars Program in 2008 in response to the IOM report Retooling for an Aging America, which emphasized the importance of training the workforce that is already in place (IOM, 2008). The program is grant-funded by the VA Office of Rural Health and VA Office of Geriatrics and Extended Care.

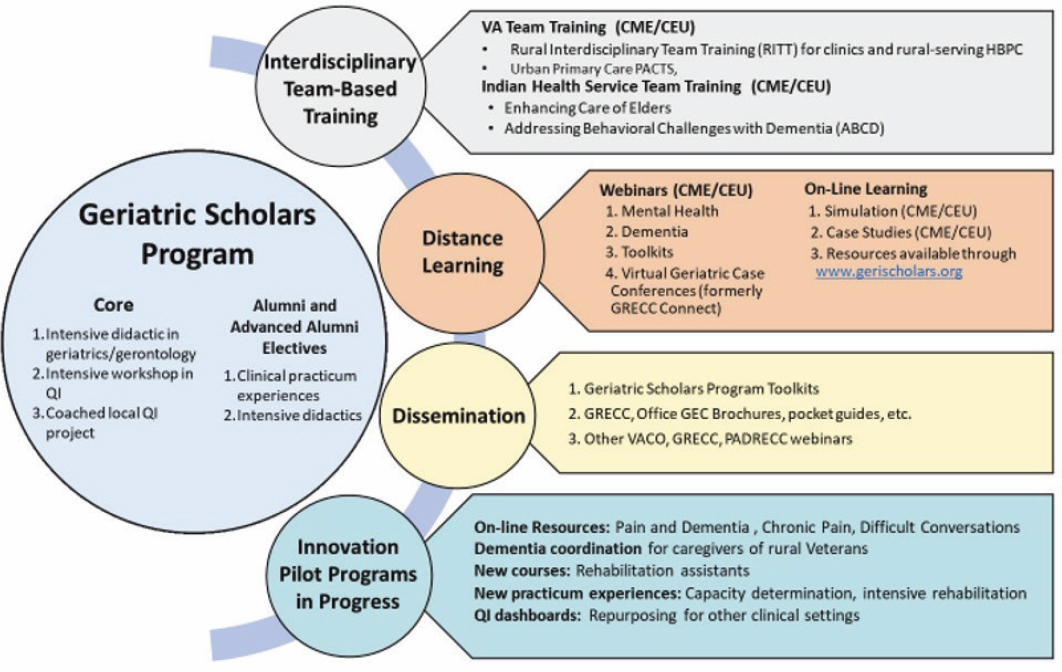

The Geriatric Scholars Program was developed with a focus on the general primary care setting where most older veterans receive health care. The pilot program enrolled only primary care providers and expanded to additional disciplines within the medical home model of primary care, including pharmacists, psychologists, social workers, rehabilitation therapists, and psychiatrists. This national workforce development program evolved over the years into its current structure (Figure 4-4) of five integrated components, Kramer said. The core component focuses on individual clinicians who receive an intensive didactic program in geriatrics and gerontology along with an intensive workshop in quality improvement. Each participant initiates a quality improvement project in his or her own local setting. The quality improvement component gives participants an opportunity to

SOURCE: Kramer presentation, December 8, 2022.

become “ambassadors for change,” Kramer said, and provides “stealth education” in teaching new knowledge to the local clinical team in implementing quality improvement. One unique aspect is the longitudinal design for continuing education. The program is a longitudinal effort; after completing this program, there are opportunities for alumni to continue additional training and improve their skills over time. Immediately following the training, at 6 months post-training, and then at intervals thereafter, program participants are asked to self-identify learning gaps and additional topics of interest for future training. Using this information, Kramer said, new continuing education programs are developed annually; about 50 continuing education programs are offered each year.

Other unique aspects are the range of continuing education training opportunities across a number of health care professions; most are accredited as continuing medical education (CME) for VA and for non-VA participants and are awarded continuing education units (CEUs). In addition to training individual scholars, this national training program is intended to improve geriatric care through interdisciplinary team-based training, distance learning, dissemination, and pilot programs. Team-based training teaches everyone in the clinic—lay and professional clinical staff—to recognize common problems among older adults that may require immediate attention during the clinical visit, to implement team-based solutions to care, and to improve clinic efficiency. This component supports each discipline’s critical role in patient interaction and making a difference in patients’ care. Team training is offered to rural VA and Indian Health Service clinics as well as to urban VA primary care teams. Distance learning efforts include webinars, on-line resources, and simulations on such topics as dementia and mental health; most of these programs are accredited for CME/CEU for VA and for non-VA participants. The program’s innovation arm develops and tests new educational programs; successful curricula are integrated into the regular program offerings and new resources, and tools that prove beneficial are disseminated. Around 1,400 scholars have completed the core Geriatric Scholars Program, and about 7,500 individuals have been reached through the team-based training and distance learning efforts, Kramer said.

Kramer described some lessons learned from the Geriatric Scholars Program. Being nimble and innovating quickly is critical, she said, and it is important to avoid mission drift. The longitudinal model can be adapted or adopted in other health systems. For example, the Indian Health Service is currently implementing its version of the Geriatric Scholars Program to meet a need to enhance geriatric expertise across its national health care system.

Martin MacDowell, a workshop participant, asked Kramer about how wellness and health promotion fit into the Geriatric Scholars Program. So many of the health issues of older adults, he said, are avoidable if people

receive accurate and timely information about improving their health. Kramer responded that the VA has a strong emphasis on whole health and integrated health and that while this is not a major focus of the Geriatric Scholars Program, it is part of the overall environment and is included in many aspects of the program. Another workshop participant, Jennifer Cabrera, followed up on this by saying that the physical therapy department is often underused in this population and that physical therapists can be a great resource for helping older adults stay active and healthy. Physical therapy is often an “afterthought” once someone is diagnosed and needs rehabilitation, she said, but it should be used earlier to prevent health problems and reduce the impact of disease on quality of life. Cathy Maxwell added that there is a need for more education so that adults understand the processes their bodies go through as they age and can take the proper steps to take care of their health. While most people know they should not smoke or be sedentary, they need a better understanding of why these behaviors lead to poor health and how they can make a change for healthier aging.