Addressing the Needs of an Aging Population Through Health Professions Education: Proceedings of a Workshop (2023)

Chapter: 3 Supply and Demand: Is the Workforce Prepared to Meet the Needs of Older Adults?

3

Supply and Demand: Is the Workforce Prepared to Meet the Needs of Older Adults?

Key Messages Made by Presenters

- These numbers mean that the population will be more advanced in age and more racially diverse, with an older workforce, while Alzheimer’s is projected to increase by 116 percent. (George)

- Ageism itself may deter students from wanting to work in geriatrics or gerontology. Furthermore, implicit or explicit bias among faculty in health professions education programs can push students in other directions. (Hartley)

- The trainees left the clinic each day challenged by the complexity of the care and also with a high degree of satisfaction because they felt they were really helping the older adults. (Bradley, Mazzurco, Lawrence)

- Incentives—particularly financial incentives—are important to the efforts to increase the workforce and improve senior care. However, they are often seen as a panacea. (Moone)

Greg Hartley, an associate professor of clinical physical therapy and medical education at the University of Miami, moderated this session of the workshop, which focused on whether the supply (i.e., the health care workforce) is or will be adequate to meet the demand (i.e., the need for care of older adults). This session was divided into three parts, Hartley explained, beginning with a presentation detailing how the population of the United States is changing, what the health care needs of U.S. citizens will be, and who will be needed to provide care and in what settings. The second part

emphasized ageism within push and pull factors that draw people toward or away from working with older adults. Finally, Hartley said, part three of the session would gather input from individuals representing a variety of professional backgrounds to reflect and build upon what they heard in the previous presentations.

HEALTH CARE NEEDS AND CAREGIVER SUPPLY

Over the next roughly 40 years, said Rebecca George, an M.D. candidate at the University of California Davis, the U.S. population is expected to grow by 22 percent to 404 million (Vespa et al., 2020). There will be a 92 percent increase in the population of adults who are 65 and older and a nearly 618 percent increase in the number of centenarians (Vespa et al., 2020). The population will be increasingly diverse, with the majority of the population being people from ethnic and racial minorities. In addition to these general population demographic changes, the makeup of the labor force is also changing, George said. The proportion of younger workers will decrease, while the proportion of older workers will increase. Taken together, she said, these numbers mean that the population will be more advanced in age and more racially diverse, with an older workforce. This presents an opportunity, she added, for more cultural humility1 and understanding of the various intersections of identity of the patients when engaging with them. As a result of the aging population, the prevalence of conditions such as diabetes, stroke, heart failure, and hypertension will increase by around 33 percent, while Alzheimer’s is projected to increase by 126 percent (Alzheimer’s Association, 2023; Roth, 2022). Currently, the population of older adults who are providing formal and informal health care are overwhelmingly female (61 percent), mostly over 75 years old (74 percent), and around a quarter live alone (AARP, 2020). Care recipients primarily need care for long-term physical conditions, memory, short-term physical ailments, and mental health.

Those who care for older adults can be lay people or health care professionals. A 2020 study by AARP and the National Alliance for Caregiving found that almost 19 percent of adults are lay caregivers, George said, and this number is likely to increase as the population ages. Further noted in the report is that lay caregivers are primarily female and over 50 years old; 89 percent of caregivers are a relative of those they care for. About a quarter of caregivers are caring for multiple adults, and 14 percent have been caregiving for more than 10 years. COVID-19, with its impacts on

___________________

1 Cultural humility is a term used to describe personal relationships that honor another person’s beliefs, customs, and values; and requires continuous self-exploration and self-critique while learning from others (Stubbe, 2020).

mental and physical health, has changed the care landscape in ways that are still being accounted for, she added.

The health care workforce is projected to grow by 13 percent over the next 10 years, adding roughly 2 million jobs (BLS, 2022). This growth will vary greatly by discipline, George said. Disciplines that are projected to grow by at least 25 percent include nurse practitioners, physician assistants, home health aides, and occupational therapy assistants and aides. At the other end, the number of dentists, registered nurses, psychologists, and physicians is expected to grow by 6 percent or less. George emphasized that these data reflect the growth in the field and do not speak to whether this growth is adequate to meet the demand for care. The location of health care delivery is shifting as well, she said, with direct care worker projected job openings in home care expected to increase by 37 percent between 2020 and 2023 and by 22 percent in residential care homes during the same period (PHI, 2023).

The health care professions’ educational system is where these future professionals will be trained. At present, George said, the United States has almost 20,000 health care training programs at nearly 9,000 sites (not specific to geriatrics). More than 50 percent of these programs are graduate-level training programs, of which more than half are physician residencies. This number is at odds with the fact that physicians are one of the slowest growing groups of health care professionals, she noted. According to George, last year nearly 80,000 health care professionals pursued faculty development training; an adequate number of faculty is essential for training the next generation of health care workers. She further stated that almost 1.5 million health care professionals pursued continuing education; however, out of the nearly 9,000 continuing education courses that were offered, only 5 percent were specific to geriatric health care.

BARRIERS TO CARING FOR OLDER ADULTS

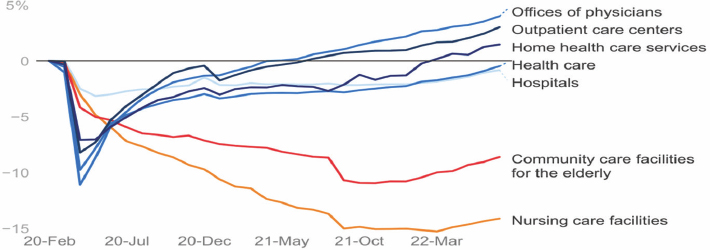

There are a number of barriers to increasing the supply of workers to care for the growing number of older adults, Hartley said. The pandemic had a dramatic impact on the workforce by exacerbating existing shortages. Pandemic-related employment losses in settings including hospitals and physicians’ offices have largely recovered, while the losses in nursing care facilities and community care facilities have persisted (Figure 3-1).

Financial barriers can prevent individuals from pursuing jobs that involve caretaking of older adults, Hartley said. For example, the income of geriatricians in medicine is at or near the bottom of 30 medical specialties. For some, the cost of education may not be worth the earning potential. This disparity reflects systemic ageism, he said; society pays for what it values. Ageism is pervasive, particularly in Western cultures, and begins

SOURCES: Hartley presentation, December 8, 2022; Wager, 2023, used with permission.

with “indoctrination” in early childhood that “aging is a bad thing.” Messages embedded in nursery rhymes and fairy tales form attitudes and beliefs that infiltrate everything, including health care. Ageism affects health in two ways. First, it affects an individual’s health outcomes and longevity; having a positive attitude about aging can extend life expectancy by as much as 7.5 years. Second, ageism among health care professionals can result in suboptimal care in a number of areas. For example, a patient’s pain may be attributed to age alone, which can lead to a patient receiving inadequate treatment. A physical therapist may believe an older adult cannot lift heavier weights or perform more repetitions, resulting in slower improvement and worse outcomes. Professionals may hold implicit beliefs about the value and potential of older adults and make decisions such as placing an older adult in long-term care (instead of an alternative non-institutional setting). Clinical researchers have historically excluded older adults entirely from research studies (in particular, drug studies), though this has changed recently, he said. The World Health Organization has recognized ageism as a problem and created a campaign in 2021 to combat ageism and mitigate its harmful impacts. The Campaign to Combat Ageism includes social media posts, information in multiple languages, and powerful images (WHO, 2021).

Finally, there are barriers within health professions education that prevent students from pursuing careers in geriatrics. Most programs do not require a dedicated course in geriatrics, even though almost every health professional will work with this group at some point in their career. In contrast, he said, pediatrics is usually a required course despite the fact that only a fraction of providers will practice in this area. Around 42 percent of physical therapy programs offer a dedicated course in geriatrics. About

76 percent of medical schools provide an optional clinical experience in geriatrics, and 45 percent of programs require a geriatric rotation for all students (Dawson et al., 2022). Hartley posited that this inadequate attention to older adults stems in part from a belief that older adults are “just adults with more years of experience,” instead of understanding that childhood, adulthood, and elderhood are three distinct phases of life (Aronson, 2019). He quoted a physician who said that most physicians graduate medical school lacking confidence in how to manage pain in a 90-year-old and that family practice doctors often know more about rare pediatric genetic diseases than they do about clearing an elderly patient for surgery.

Having grown up in a society full of messages that devalue older adults, students may be deterred from wanting to work in geriatrics or gerontology, Hartley said. Furthermore, implicit or explicit bias among faculty in health professions education programs can push students in other directions. For example, faculty may say or imply that caring for older adults is “boring,” “depressing,” or that “patients don’t improve.” Despite the growing population of older adults, the number of health care professionals focusing on geriatrics is actually declining, he said; for example, the number of first-year residents and fellows studying geriatrics declined by 14 percent between 2012 and 2017 (AAMC, 2018).

ROUNDTABLE DISCUSSION

With the presentations of George and Hartley in mind, the session turned to a roundtable discussion to explore the challenges of building an adequate workforce for older adults and to discuss potential solutions to these challenges. Hartley began by asking panelists what has inspired them, as well as the learners they work with, to pursue a career in working with older adults. Ryan Bradley, the director of research at the Helfgott Research Institute at the National University of Natural Medicine, responded that situational learning is vital to the clinical education experience. As a clinical educator of medical students and residents, he has observed that situational learning in primary care delivery to older adults has had a strong and positive impact on learners’ interest in working with older adults in their careers. Bradley served as an attending physician in an integrative primary care clinic nested within a community-based senior center. His previous employer, Bastyr University, was invited to develop a clinic in this setting because the senior center leaders recognized that their community members had unmet needs, including highly uncoordinated care and a lack of guidance on nutrition, physical activity, and other approaches for improving function. Fourth-year medical students and residents at the clinic found their care delivery experience to be highly rewarding, Bradley said. The patients were appreciative of having care providers listen to their stories,

coordinate their care, and give practical suggestions for improving their health. The trainees left the clinic each day challenged by the complexity of the care and also with a high degree of satisfaction because they felt they were really helping the older adults, he said.

He gave two examples of students whose experiences in the clinic influenced the direction of their careers. One student, after witnessing the need for dementia care, went on to operate a clinic that specializes exclusively in cognition care and also started a residential long-term care facility that incorporates many of the tenets of integrative medicine, including plant-based nutrition, combined cognitive and physical exercise, social support, and highly multidisciplinary care teams on site. Another student entered the clinic wanting to focus on traditional complementary medicine approaches (e.g., homeopathy, hydrotherapy). However, her experience in the senior care community clinic working with patients who had multiple chronic conditions and were taking multiple medicines, often without a provider managing their care, shifted her focus, and she now runs an integrative primary care clinic that focuses almost exclusively on older adults with multiple chronic conditions. Situational learning experiences like these are pivotal, Bradley said, both for students to learn about the considerable need that exists in this population and also to experience how rewarding it can be to work with “such an appreciative, responsive, and deserving group of people.”

Lauren Mazzurco, a professor of geriatrics at Eastern Virginia Medical School, said she has had opportunities to work with learners across the continuum, from premed students to residents, fellows, and practitioners, and has used these opportunities to find out why they are interested in working with older adults. Many have had close relationships with older adults in their own lives and saw the frustrations and challenges that these adults had with their health care experiences. Learners are also motivated by the fact that geriatrics has one of the highest satisfaction rates of any medical specialty as well as by the focus on well-being, self-care, and quality of life. In geriatrics, she said, it is essential to not “miss the forest for the trees”; providers must look at every element of a patient’s care and consider ways to improve function and independence. While taking care of an older adult can be “very overwhelming,” Mazzurco said, job satisfaction and the ability to make a big impact can be surprising and empowering for learners. They take these lessons back to other specialties when on rotation, she said; for example, a surgery patient may have delirium, and the learner is better able to understand that individual’s mental state and be more patient. The career paths for learners who wish to specialize in caring for older adults are currently quite limited, Mazzurco said, so she advocates for opening up more diverse specialty track pathways. However, regardless of what field learners pursue, their experiences with older adults can affect their future work and help to make health systems more age-friendly.

Working with older adults can be intimidating for new learners in health care, said Jeannine Lawrence, the senior associate dean in the Department of Human Nutrition at University of Alabama, particularly if the learner has not had any meaningful opportunities in his or her own life to interact with older adults in a positive manner. Learners often come into the profession with preconceived stereotypes about older adults; one of the challenges for educators is to break these stereotypes and show the diversity of the older adult population. Educators also need to enhance learners’ intentions to and enthusiasm for working with older adults and increase their confidence and skills in doing so. In nutrition—and other health fields—one significant predictor of intentions to work with older adults is attitudes toward older adults. Providing frequent and quality interactions with older adults in a variety of settings is very effective at positively affecting learner attitudes towards working with older adults, Lawrence said. She explained that this means that students need more than a single rotation in a long-term care facility; they also need other opportunities to engage with older adults, such as through partnerships with community agencies or working with seniors who live independently. Subjective norms provide another strong predictor of intentions to work with older adults. When faculty and other role models themselves work with and talk about older adults, it can create a perception that this is a valuable career path and inspire learners to follow such a path. Finally, Lawrence said, learners need interprofessional education and training to prepare themselves for geriatric practice; it can be a real deterrent to students who think they will be solely responsible for making decisions about the complex care of older adults.

Lawrence told workshop participants about a program she and her colleagues developed to address confidence and roles in a health care team. Nutrition, nursing, social work, and medical students sat together and discussed their scope of practice and perceived roles within the team; Lawrence said it was “pretty fun” because none of the students had any idea what training or skills the other students had. The teams then went out and worked with rural older adults over a period of 6 months to assess and address their health care and daily living needs. During this time, the students experienced a rapid upturn in confidence in both working and connecting with the older adult participants, as well as building reliance and trust in their own team. The students no longer felt unprepared to meet the needs of the 38 participants because they knew exactly who on the team to turn to when a need was identified. After this experience, the students reported feeling more confident working with older adults and with other health care professionals. Encouraging and inspiring learners to work with older adults requires a multi-pronged approach, Lawrence said, including providing high-quality interactions with older adults, varied and regular experiences, good role models, and interprofessional training.

Financial Barriers

Hartley next turned to financial barriers. He asked Rajean Moone, the faculty director for long-term care administration in the College of Continuing and Professional Studies at the University of Minnesota, to comment on incentive structures for encouraging health care students and professionals to work with older adults. “We don’t have long lines of students entering gerontological and geriatric practice,” Moone said, so incentives—particularly financial incentives—are important to the efforts to increase the workforce and improve senior care. However, he continued, they are often seen as a panacea that will magically solve all of the problems. In practice, the success of financial incentives is contingent upon other systemic factors and reform. Incentives are fairly straightforward and are not a new phenomenon; the basic principle is that humans are driven toward rewards and away from negative experiences. Incentives in the senior care workforce tend to be a patchwork of state and federal programs, and they are often under-resourced.

Financial incentives can fall into several categories. The first are incentives for students currently in school. These could include scholarship programs and paid internships working with older adults. The second is incentives for those who have already graduated. Loan forgiveness is paramount in this area, and many states have piloted and implemented loan-forgiveness programs for those who work in senior care, particularly in rural and other underserved areas. The third type of incentive is for those already working in senior care, such as increased wages or competitive benefits. Moone warned, however, that wages and benefits are part of a much larger and more complicated conversation about long-term care financing reform. The nursing home sector has suffered for decades from underinvestment and a lack of accountability in how resources are allocated. In Minnesota, he said, the average hourly wage for a direct-care staff member in senior care is around $16 per hour; in comparison, the starting hourly wage at a major retailer is $20 per hour with full benefits and tuition assistance. There were a few incentives that were implemented during COVID—primarily relaxing barriers to certifications and credentials—that are being phased out. These have provided a temporary boost to the senior care workforce, but the impact on the quality of care is unclear.

Unfortunately, there is not a great deal of longitudinal literature of the effectiveness of financial incentives aimed at students, recent graduates, or workers. It is clear that incentives can provide a temporary boost, but their long-term sustainability is not clear. Moone said that there are larger-scale, systemic changes that have the potential for increasing the workforce, such as immigration reform or increasing reimbursement rates, but these are not often considered in conversations about workforce incentives. There

is a need to explore long-term, proven strategies to ensure a vital, robust workforce, including financial incentives and other approaches.

Incentivizing Nurses

Hartley asked Barbara Resnick, a professor in the Department of Organizational Systems and Adult Health at the University of Maryland School of Nursing, for her perspective on non-financial incentives that could encourage people to choose careers working with older adults. Resnick responded that the conversation about a looming boom of older adults and the lack of an adequate health care workforce often “dances around what needs to be done.” She put it bluntly: “Change the law, and you change behavior.” All people working in health care are going to be dealing with older adults in some way, she said, and they should be required to learn about this population. In nursing, every adult nurse practitioner is required to be trained in geriatric care. This needs to be done across all health disciplines, Resnick said; this is the “number one way to change things.” Once exposed to working with older adults, there will be some learners who realize how much they enjoy the field. For others, they will simply be trained in how to better care for older adults across all settings. After all, she commented, even in pediatrics one has to care for and address the grandparents. A second way, as many other speakers have noted, is to expose students to older adults. However, educators have the responsibility to make these experiences fun and opportunities for learning critically important assessment, diagnosis, and management skills, rather than presenting long-term care as a “negative, horrible clinical experience.” The third approach for encouraging students to work with older adults is to focus on job opportunities and job security. Resnick said that she tells her students that the best positions are in long-term care because they will see diseases and have experiences they would not have otherwise, they will have a team to work with, and they will be able to change how care is provided. Resnick agreed with Moone that incentives are often a short-term fix and that structural changes are needed to truly improve the system.

Specialization Issues

In medicine, geriatrics is usually a sub-specialty of internal medicine or family medicine, Hartley said. Other professions have also created specialties or sub-specialties for working with older adults, but it can be a struggle to get people to choose these specialties. Hartley asked panelists to comment on this challenge. Mazzurco said that this is a big problem and that there need to be creative solutions. She noted that while there is “big G geriatrics” (highly trained board-certified geriatricians of which

the numbers are dwindling), there is also “little g geriatrics” (geriatric scholars who teach geriatrics principles to all health professions and to the public), and both are important (Callahan et al., 2017). The American Geriatric Society has made some innovative efforts in this area, such as integrated residencies and fellowships; this allows learners to gain experience in geriatrics from the very beginning of residency rather than waiting until the end to do specialty training. Some providers who are already practicing and have realized the gap in their own knowledge and skill set in caring for older adults may wish to pursue a geriatrics fellowship, Mazzurco said, but it is just not logistically possible for many people. There are innovative models evolving that offer fellowships that fit within providers’ lives, such as “interrupted fellowships” that allow providers to work in between rotations for the fellowship. Until geriatrics training is required for all health professions learners, these types of programs can bridge the gap and provide creative solutions for training people in geriatrics.

George added that in addition to the challenge of getting learners to specialize in geriatric care, primary care as a specialty is undervalued in medicine. This will have a big impact on the older adult population moving forward, she said. Learners come out of medical education with hundreds of thousands of dollars of debt, and they are not incentivized to enter a field that will make it challenging to pay off their debt.

Role of Families and Lay Caregivers

Given the likely inadequate workforce and the growing older adult population, Hartley said, much of the care of older adults will be provided by lay people and untrained individuals. Hartley asked panelists for thoughts on how these caregivers could potentially be trained or integrated into the health system. Resnick responded that there is a big initiative in nursing to conduct family trainings; she said that “the expectations now on families are mind boggling.” Nurses often are the ones who most closely interact with families, particularly during transitions of care. Nurses need training in cultural competence, communication, and other skills to help them reach these families. Resnick said there are opportunities to bring families into acute or subacute care environments to allow them to begin to practice the skills they will need at home, noting that as a mother of triplets in the neonatal intensive care unit, she insisted on providing as much care as she could to her babies. Another way to train lay people, she said, is with apprenticeship programs, which were historically very common in medicine and nursing.

Bradley said that while family members can play a very important role, “we need to be really careful to not redirect the responsibility of health care back to family members.” The responsibility of primary care is to help

patients navigate their care and develop coordinated care plans, and this should not be placed on the shoulders of family members. There are other professionals who could be used, such as health coaches, who could contribute to senior care if they were empowered to serve in this role. Family members are important for patient care, but the health care delivery system and community still holds primary responsibility in this regard. Maryam Tabrizi, a geriatric dentist at the University of Nevada Las Vegas agreed with Bradley, saying that care providers open the “door to neglect” when they pass the responsibility for care to family members. Caring for older adults is exhausting and can last years, she said, and the emotions involved can make it even more challenging.

Role of State Policy

Shirley Girouard, who is part of the nursing faculty at the State University of New York Downstate, asked about state policies that could be helpful in expanding and strengthening the workforce for older adult care. Moone replied that many incentives, particularly financial incentives, are the product of state legislation, and states can also choose to relax requirements for certification and credentials. In addition, states have key roles in broader workforce development. In Minnesota, for example, there is currently a huge number of open positions in senior care, and many senior care communities have to deny admission because they do not have enough workers to care for people. With record unemployment rates and competition from other employers, it is time to have a complex conversation about changing the way that long-term care is financed. In particular, he explained, a key issue is paying for the real value of nurses. Any conversation about this will require confronting difficult topics such as sexism and racism and the value that society places on different members of our communities.

Hartley pointed out the need for macro, meso, and micro levels of change. At the micro level, there is a need to advocate for changes in accreditation standards and require geriatrics for all learners. At the meso level, there is a need to advocate for state legislators to do their part to bolster the workforce. At the macro level, federal action on the financing of long-term care or long-term support services is needed, along with discussions about Medicare and Medicaid payments.

Defining Quality

Bradley noted that several speakers during the workshop had brought up the issue of not sacrificing quality when considering innovations in training and care delivery. Quality is of course essential, he said, but he

urged stakeholders to consider what quality means to the older adults themselves. Within the health professions, quality is sometimes defined by process metrics or processes, but patients are looking for things that improve their quality of life, function, and health. He emphasized the need to think outside the box about what really matters to the individual and to keep the focus on that.