The Role of Plant Agricultural Practices on Development of Antimicrobial Resistant Fungi Affecting Human Health: Proceedings of a Workshop Series (2023)

Chapter: 8 One Health Approach to Antimicrobial Resistance and Pathogen Surveillance

8

One Health Approach to Antimicrobial Resistance and Pathogen Surveillance

The seventh session of the workshop focused on surveillance studies and research investigating the association between the use of agricultural fungicides and the emergence of antifungal-resistant infections, factors contributing to the risk of cross-resistance, and mitigation efforts. Maryn McKenna, senior writer at WIRED and Senior Fellow in Health Narrative and Communication at the Emory University Center for the Study of Human Health, moderated the session. Paul Verweij, professor and chair of the Department of Medical Microbiology at Radboud University in the Netherlands, discussed the emergence of antifungal resistance in clinical settings, its association with agricultural use of fungicides, and potential risks for increased development of cross-resistance. Marin Talbot Brewer, associate professor of mycology and plant pathology at the University of Georgia, presented findings from U.S. surveillance studies of A. fumigatus in the environment and on consumer food and garden products. Multi-fungicide-resistant isolates have been identified in a variety of agricultural settings and garden and lawn products. Shawn Lockhart, senior clinical laboratory advisor for the Mycotic Disease Branch and senior advisor for antimicrobial resistance at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), described the limited efforts to detect resistant fungal infections in the United States, a lack of available antifungal susceptibility diagnostic products, and low capacity for laboratory processing of these tests. He discussed the value of expanded antifungal resistance surveillance and of greater communication and collaboration between various sectors. Jorge Pinto Ferreira, a veterinarian and food safety officer at the Food and Agricultural Organization (FAO) of the United Nations, described international

guidance and data platforms for antimicrobial resistance (AMR) surveillance efforts. Bas Zwaan, professor at Wageningen University & Research in the Netherlands, provided an overview of the One Health Aspects of Circularity project, the benefits and risks of a circular system of farming, and research efforts to identify interventions to mitigate the threat of agricultural antifungal resistance to clinical populations.

ONE HEALTH APPROACH TO ANTIMICROBIAL RESISTANCE SURVEILLANCE AND MITIGATION MEASURES

Verweij explored the necessity and benefits of adopting a One Health approach in conducting AMR surveillance and implementing mitigation measures. He described the emergence of azole-resistant A. fumigatus (ARAf) and research associating this emergence with the use of azole fungicides. He also discussed barriers to antifungal resistance research and interventions, as well as risk levels for various potential sources of cross-resistance.

Emergence of Azole-Resistant Aspergillus fumigatus in Humans

In 2007, several patients developed aspergillosis with azole-resistant isolates found in their clinical samples, said Verweij (Verweij et al., 2007). Four of these patients lacked prior history of azole treatment, indicating that the source of azole-resistance was not medical treatment of the host. Following this discovery, a large collection of A. fumigatus isolates was investigated for resistance (Snelders et al., 2008). Prior to 2000, no resistance was present; however, resistant isolates were found in patient samples collected every year thereafter. Furthermore, the majority of these isolates had the same mutation with tandem repeat (TR) insertions that are associated with environmental resistant isolates. This finding indicates the possibility that resistance is selected for in the environment. Verweij and colleagues investigated 35 fungicides for activity against A. fumigatus with a wild-type isolate and an isolate with the TR34/L98H resistance mutation (Snelders et al., 2012). Five fungicides from the triazole class were found to have high activity against the wild type and no activity against these TR34 isolates. Additionally, two fungicides from the diazole class were active against the wild type and not against TR34.

Modeling studies investigated cross reactivity and found that two of the fungicides—propiconazole and bromuconazole—had very similar core structures to two medical triazoles, itraconazole and posaconazole (Snelders et al., 2012). Moreover, fungicides tebuconazole and epoxiconazole were very similar to another medical triazole, voriconazole. A fifth fungicide, difenoconazole, demonstrated a strong interaction with three medical

antifungals itraconazole, posaconazole, and voriconazole. Thus, these five fungicides were suspected of driving the clinically observed resistance. The Netherlands first authorized use of these fungicides between 1990 and 1996 (Snelders et al., 2012) and the first resistant isolates detected via susceptibility testing were from clinical samples dating back to 1998. Verweij stated that the time span between the introduction of a fungicide and the appearance of resistance is typically about 10 years, which holds for A. fumigatus.

Research and Actions to Address Resistance in Aspergillus fumigatus

The emergence of resistant A. fumigatus necessitated (1) devising appropriate methods of detection, (2) developing better understanding of its effects on humans, and (3) identifying its source. Verweij noted that several research groups undertook the challenge of detecting resistance, resulting in a commercial polymerase chain reaction (PCR) test to detect TR34 and TR46 (Chong et al., 2015) and a simple agar-based screening assay that enabled straightforward detection of resistant colonies (Buil et al., 2017). A study compared patients with voriconazole-susceptible infections and voriconazole-resistant infections to determine the effects of resistance on human outcomes, finding that the survival rate decreased by 20 percent in individuals with a resistant isolate (Lestrade et al., 2019a). Verweij emphasized that the introduction of voriconazole initially led to a 15 percent increase in survival rate for patients with invasive aspergillosis (Denning, 1996); the emergence of resistance virtually eliminates this benefit. As more research indicated that resistance to antifungal compounds in the environment was driving resistance observed in clinical isolates, studies have focused on detecting environmental locations with selective pressure for azole resistance in A. fumigatus (Schoustra et al., 2019b). Resistance hotspots—which feature both a habitat for A. fumigatus and the presence of azole residues—have now been identified. Moreover, new preliminary population genomic analysis have provided more evidence for a link between environmental resistance and clinical resistance (Rhodes et al., 2021).

Verweij presented a timeline of major research and mitigation efforts undertaken to address ARAf in the Netherlands. The first case of a clinical resistant isolate was retrospectively identified and dated back to 1998. Between 2007–2015, research was published on the first case series of azole-resistant invasive aspergillosis (Verweij et al., 2007), the emergence of the TR34 mutation (Snelders et al., 2008), the hypothesis that resistant aspergillosis was associated with environmental fungicide use (Verweij et al., 2009), indication of triazole fungicides inducing cross-resistance to medical triazoles (Snelders et al., 2012), the emergence of the TR46 mutation (van der Linden et al., 2013), and PCR assays to detect resistance (Chong et al., 2015). In 2013, the Netherlands National Institute

for Public Health and the Environment instituted a surveillance network, and five medical centers and five teaching hospitals participate in annual surveyance reporting for this network. In 2015, the Netherlands Ministry of Health awarded Verweij and colleagues a grant to research the implications of resistance, and in 2017 the Netherlands issued a guideline that recommends combination antifungal therapy for all patients suspected of invasive aspergillosis. In 2019, research regarding the mortality of resistant invasive aspergillosis (Lestrade et al., 2019a) and identifying environmental hotspots (Schoustra et al., 2019b) was published. In 2021, a mitigation protocol was implemented in the Netherlands for the first time. Verweij emphasized that it took about 10 years for A. fumigatus to develop resistance, yet it took more than twice that time for targeted interventions to be implemented.

Challenges to Implementing Interventions to Address Resistant Aspergillosis

Several challenges contributed to the lengthy timeframe between the identification of azole-resistant invasive aspergillosis and the implementation of interventions, said Verweij. Initially, disbelief in the reports of resistance slowed the research response. He remarked that when he submitted his first research application on this issue, a grant reviewer expressed their incredulity at the possible link between clinical azole-resistance and environmental fungicide use. Additionally, the first time his group’s hypothesis was submitted to The Lancet Infectious Diseases journal, it was denied publication due to insufficient evidence (it was published 2 years later after resubmission) (Verweij et al., 2009). Furthermore, Verweij described general feedback that resistant cases were a local problem rather than a national or international issue.

Given that A. fumigatus is not a plant pathogen, it was difficult to locate a partner in the agriculture sector. Verweij stated his good fortune in finding collaborators at the Wageningen University who were researching A. fumigatus in the environment. Invasive mycosis is not generally perceived as a public health problem, which further complicates research efforts. Although patients with leukemia were initially identified as susceptible to developing mycosis, that susceptibility did not extend to the general public. Now that the risk of resistant infections have broadened to patients with influenza and COVID-19, the public health problem has become more apparent. Moreover, resistance has also developed in other pathogens. Verweij noted that with the exception of the U.S. CDC, most public health institutes do not have a mycotic branch or mycology expertise, and this contributes to the challenge of raising awareness about this public health issue.

Fungal resistance has not been prioritized, and many AMR programs exclude it. When fungal resistance is included in AMR programs,

it competes with bacterial resistance, an area with far more researchers. Verweij analyzed infectious disease grants awarded by the Dutch Medical Research Council between 2006–2023, and found that of the 129 projects funded for a total of $66 million, only four of these grants addressed AMR, and a single project addressed fungal resistance. He emphasized that the Netherlands has high fungal resistance rates and low bacterial resistance rates; yet only one project was dedicated to fungal resistance, indicating the challenges in prioritizing this area. Additionally, many stakeholders are involved in this problem, including the Ministries of Health, Agriculture, and Infrastructure; the fungicide authorization board; fungicide producers; fungicide users; medical researchers; and agricultural researchers. With so many stakeholders in this field, leadership can be difficult to establish to move initiatives forward, he remarked.

New Challenges in Research on Resistant Isolates

Verweij described his current research on resistant isolates. Of the nearly 12,000 clinical isolates collected since 1994, approximately 1,800 were azole-resistant, with significant increases since 2008. Moreover, the number of variants is also increasing, with 91 different resistant genotypes identified across the TR34, TR46, and F46Y groups, in addition to isolates with single resistance mutations. This high number of genotypes poses diagnostic challenges. He and colleagues found an isolate in 2021 with TR34/L98H mutations and several single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) in the cyp51A gene. There are published literature that describe each genetic component: The TR34 genotype is known to confer full resistance to itraconazole, a T289A mutation is known to indicate high resistance to voriconazole, and a G448S single point mutation is known to provide resistance to both itraconazole and voriconazole. However, susceptibility testing showed that the isolate was susceptible to itraconazole and resistant to voriconazole and esophogonazole. This example demonstrated how the variety of co-existing SNPs can complicate the process of determining an isolate’s resistance phenotype. Available PCR tests detected TR34 and TR46 mutations, but those diagnostics don’t detect SNPs and are likely unable to provide full information on the isolate’s resistance phenotype (Song et al., 2022).

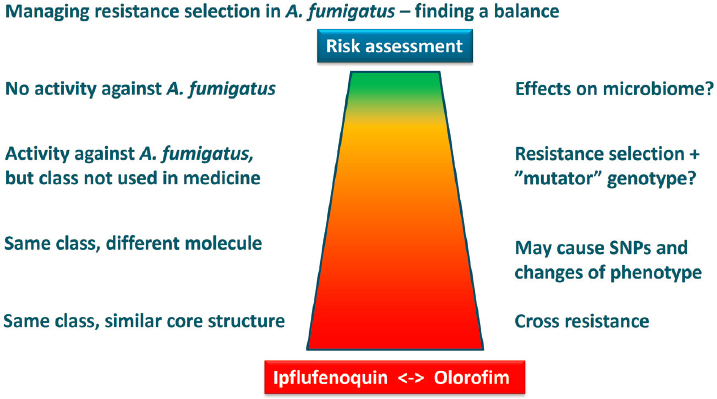

Managing resistance in A. fumigatus involves striking a balance between use and risk assessment, said Verweij. For instance, one might assume that a fungicide with no activity against A. fumigatus would be safe for use in the environment, though this fungicide might still have an indirect effect on human health through affecting the microbiome. A fungicide that has activity against A. fumigatus but belongs in a class not used in medicine may be problematic if A. fumigatus isolates develop resistance to this fungicide, and, as a result, acquire a mutator genotype that increases their probability

of developing more spontaneous mutations (e.g., SNPs that confer azole resistance). The risk for cross-resistance is higher still for a fungicide that features azole compounds but has a different molecular structure. The fungicide could potentially drive SNPs in the cyp51A gene, as is the case with imazalil (a diazole fungicide). Verweij remarked that fungicides from the same class as medical antifungal drugs and featuring a similar core structure pose the highest risk of cross-resistance. He added that this question of balance is relevant in regard to dihydroorotate dehydrogenase (DHODH) inhibitors (see Figure 8-1). Currently, olorofim is being developed for clinical use and ipflufenoquin simultaneously has been authorized for use in the environment. Given that both of these products are DHODH inhibitors, potential for the development of cross-resistance is present.

GENOMIC SURVEILLANCE AND EPIDEMIOLOGY

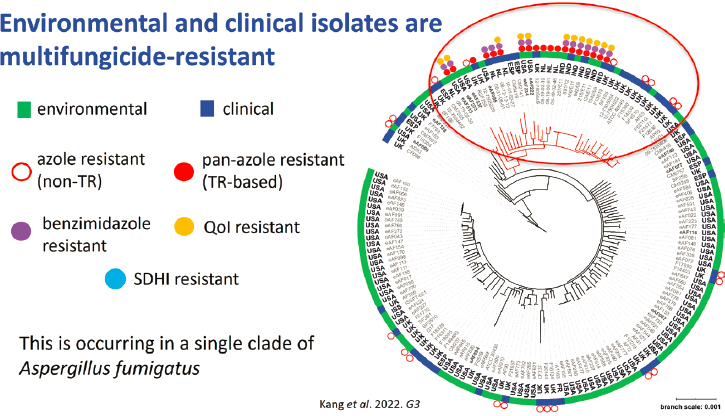

Brewer presented findings from U.S. surveillance studies of A. fumigatus in the environment. Conducted in settings where azoles are used, these studies aimed to identify hotspots—i.e., locations where resistance is likely to be developing or is already abundant—in order to target mitigation strategies. Multi-fungicide-resistant isolates were identified in a variety of agricultural settings. Genomics analysis was applied to isolates collected from different settings and uncovered genotypes that were present in both

NOTE: SNP = single nucleotide polymorphisms.

SOURCE: Verweij presentation, June 27, 2022.

the environment and in the clinic. Genomic surveillance is a tool for gaining a better understanding of ARAf transmission from their origin site to the patient, she explained.

Evidence Supporting the Agricultural Origin of Clinical Pan-Azole Resistance

Cases of azole-naïve patients acquiring pan-azole resistant infections indicate that ARAf infections in humans come from the environment, said Brewer. Isolates from the environment and isolates from the clinic share resistance mechanisms—the most common of which are TR34 and TR46 mutations—that have been detected around the world. Additionally, human and environmental ARAf isolates share multilocus genotypes and nearly identical whole-genome sequencing genotypes (Burks et al., 2021). Thus, evidence that these infections come from the environment is strong, but the patterns of ARAf movement are not yet known, Brewer remarked. In addition, questions remain about whether azoles used in wood preservation contribute to resistance. Likewise, the role of topical azole residues in resistance development remains unknown. After such residues enter waterways, they could become part of biosludge that is applied in the environment.

In an effort to determine the movement of ARAf isolates from agricultural environments into patients, Brewer and colleagues conducted surveillance in the United States. Prior to their work, the only identified azole-resistant isolates were found in peanut crop waste debris in Georgia. They collected over 700 isolates from 50 agricultural sites in Georgia and Florida where azoles are heavily used. These locations included soil and plant debris from fields and orchards growing peanut, grape, pecan, apple, strawberry, tomato, and orange crops, in addition to compost and pecan-processing debris. After screening, they conducted broth microdilution assays to determine the minimum inhibitory concentrations (MIC) of 172 of the 700 isolates, testing them against tebuconazole, itraconazole, voriconazole, and posaconazole. They found pan-azole resistance in 12 of the isolates. By sequencing the cyp51 gene, the TR46 allele was found in all 12 pan-azole resistant isolates. She noted that the samples came from compost or pecan debris, but the peanut production debris they anticipated would be a hotspot did not yield any pan-azole resistant samples.

Brewer sought to determine whether the resistant isolates found in patients featured a signature that could be found in isolates from agricultural sites. She posited that the presence of resistance to multiple fungicide classes would indicate that A. fumigatus are adapting in agricultural environments. To ascertain whether azole-resistant clinical and agricultural isolates are resistant to other classes of fungicides, these isolates were tested against quinone outside inhibitor (QoI) fungicides, also known as

strobilurins. This class of fungicides is not used to treat humans and the G143A mutation in cytochrome B is known to be associated with QoI resistance, making it easily identifiable in both plant pathogenic fungi and A. fumigatus. Genome sequencing was also performed on environmental isolates from the research team’s collected samples and on publicly available environmental and human isolates. Researchers scanned for QoI resistance and for resistance to additional fungicide classes, the benzimidazoles and the succinate dehydrogenase inhibitors (SDHI). She emphasized that a single gene can feature multiple signatures of resistance.

Multi-Fungicide Resistance

Using a representative wild-type isolate—which is sensitive to QoI, benzimidazole, and SDHI—for comparison, approximately 120 isolates containing either the TR34 or TR46 allele were sequenced. Derived from humans or from the environment in the United States, the Netherlands, and India, many of these isolates were found to have the G143A allele associated with QoI resistance. All of the isolates tested had the F219Y allele, indicating resistance to benzimidazoles. A minority of the isolates contained H270Y, the genomic signature of SDHI resistance. Furthermore, the phenotype of these isolates matched the genotype for resistance to these various fungicide classes. Thus, pan-azole resistant isolates were found to be multi-fungicide resistant, Brewer stated.

To determine how the A. fumigatus isolates were evolving, whole genome sequences of isolates were used to construct a phylogenetic tree. The isolates did not necessarily cluster according to their collection source (e.g., environmental or clinical) (Kang et al., 2022) (see Figure 8-2). Instead, the pan-azole resistant isolates with TR34 or TR46 alleles clustered together into a single clade. Moreover, all of the multi-fungicide-resistant isolates clustered within this same clade. Brewer described another pattern in the pan-azole resistant isolate phenotypes: Most of the pan-azole resistant isolates were resistant to benzimidazoles, many of them were resistant to QoIs, and a few were resistant to SDHI, a progression that follows the chronology of the introduction of these fungicide classes. The longer a class had been in use in the environment, the higher the proportion of resistant fungal isolates were detected. Thus, evidence supporting an agricultural origin of pan-azole resistance includes (1) the presence of multi-fungicide-resistant A. fumigatus in both the environment and the clinic, (2) the discovery of geographically widespread multi-fungicide-resistant isolates across the world, (3) the phylogenetic clustering of clinical and agricultural isolates to a single clade, and (4) the presence of isolates with fungicide resistance markers found in patients, said Brewer. She added that resistance to multiple classes of fungicides may complicate any efforts to preserve the azoles for clinical

NOTE: QoI = quinone outside inhibitor; SDHI = succinate dehydrogenase inhibitor; TR = tandem repeat.

SOURCE: Brewer presentation, June 27, 2022; adapted from Kang et al., 2022.

use. Minimizing the use of agricultural azoles by more exclusively using other fungicide classes may not successfully preserve azole therapies, as other classes may still indirectly select for azole-resistant isolates.

Broadened Surveillance Efforts

Brewer and colleagues extended surveillance efforts to additional regions and crops to determine whether hotspots can be found across the United States. In 2018 and 2019, soil and plant debris were sampled from 52 sites from 8 states along the East and West Coasts. Sampled crops included tulip, hemp, wheat, apple, grape, herbs, flowers, brassica, cucurbit, peanut, peach, corn, and soybean. Compost was also tested, with samples taken from an organic farm to compare with samples from farms using fungicides. The resulting 727 isolates were screened and MICs were determined using broth microdilution assays. A greater range of phenotypes was found compared with the previous surveillance study performed in Georgia and Florida. Additionally, they identified isolates with mid-range MICs that did not carry cyp51 mutations associated with resistance. Approximately 20 isolates were pan-azole resistant and contained the TR34 and TR46 alleles. These came from grape, wheat, herbs, peach, tulip, and compost, with the majority

coming from the latter two categories. As of June 2022, the phylogeny analyses are still in progress. Brewer noted that one of the tulip fields sampled was organic, but all bulbs were imported from the Netherlands, indicating a potential method of global movement of resistant isolates.

Azole Resistance in Food Supply and Plant-Based Retail Products

Another research effort investigated the possibility of human exposure to azoles used on crops via food and garden products by testing food and plant-based retail products for ARAf, said Brewer. Samples from grocery store produce included grapes, almonds, peanuts, pecans, and apples. Compost, soil, and flower bulbs were selected for home and garden product sampling due to the high amounts of azoles typically used on these elements. Most of the products sampled originated in the United States, with some of the gardening supplies coming from other countries. Over 500 A. fumigatus isolates were identified, with the majority found in peanuts, compost, flower bulbs, and soil. All A. fumigatus isolates were screened on selective media, and 130 isolates were tested for MIC levels. The majority of isolates from compost and flower bulbs were found to have pan-azole resistance. Approximately 47 percent of the 130 isolates were azole-sensitive, 18 percent were resistant only to tebuconazole (an azole fungicide), 6 percent were resistant to one type of medical azole, and 29 percent were resistant to tebuconazle and more than one medical azole.

Sequencing the cyp51A gene identified TR34 or TR46 alleles in nearly a quarter of these isolates, Brewer explained. However, the remainder of the 130 isolates featured a variety of cyp51A genotypes. Some isolates carried the wild-type version of the gene, while others had alleles not shared by any other isolates in the samples. The most common genotype—found in 40 percent of the isolates—contained Y46F/V172M/T248N/E2555D/K427E alleles. Brewer referred to this genotype as “type 3.” In investigating the association of resistant phenotypes and cyp51A genotypes, the majority of pan-azole-resistant isolates had the TR34 or TR46 allele. The “type 3” genotype was featured in just 5 of the pan-azole resistant isolates, but also in the majority of azole-sensitive isolates. Therefore, the “type 3” genotype on its own does not underlie resistance, and there must be another mechanism involved in conferring the azole resistance, Brewer remarked. She added that most of the pan-azole-resistant isolates with TR alleles were from compost or tulips, with a single such isolate obtained from raw peanuts. Very low levels of A. fumigatus were found on peanuts that had been roasted or salted.

Genotyping was used to compare isolates from retail products, field samples, and clinical samples. Brewer noted that none of the clinical isolates were azole-resistant. Multivariate analyses and k-mer analysis revealed six clusters of isolates, four of which were fairly similar to one another and the other two

being outliers. Azole-resistance was lowest in the four similar clusters, with 87 percent of these isolates indicating azole susceptibility. The clinical isolates were spread across the four similar clusters. One of the outlier clusters was comprised of isolates from retail products, 61 percent of which were azole-susceptible. The other outlier cluster was comprised of isolates from compost, flower bulbs, peanuts, and pecans. All of these isolates were azole-resistant or pan-azole-resistant, and they all featured the TR34 or TR46 allele.

Brewer reiterated that pan-azole resistance was found in commercial peanuts, soil, compost, and flower bulbs, primarily in compost and bulbs. Although most of the pan-resistant isolates had TR34 or TR46 alleles, other alleles were also identified that are not associated with azole resistance. Non-cyp51A-based mechanisms of resistance warrant further investigation. A. fumigatus populations in the United States appear to cluster genetically based on their pan-azole-resistant phenotype, not by whether they are derived from the clinic or environment. Of the food and garden supplies sampled, lawn and garden products contain the most pan-azole resistant isolates. Brewer remarked that these products thereby pose the greatest risk for people who are at risk of aspergillosis. Her current research involves azole residue profiling on substrates with high levels of ARAf to determine associations between azole residues and hotspots. Genotyping will be performed on fungal isolates from agricultural samples and on publicly available clinical samples (Etienne et al., 2021) to identify common genotypes present in both the environment and clinic in the United States. This research will aid in identifying hotspots for targeting mitigation efforts.

DIAGNOSTICS, RESISTANCE TESTING, AND SURVEILLANCE CAPABILITIES IN HEALTH CARE AND AGRICULTURAL SYSTEMS

Lockhart described the limited efforts to detect antifungal resistant infections in the United States and associated the country’s low rate of resistant Aspergillus infections with a lack of detection, rather than absence of ARAf in clinical settings. He outlined the lack of antifungal susceptibility diagnostic products and the low number of laboratory facilities that process these tests. He also discussed the need for more antifungal resistance surveillance and greater communication and collaboration between various sectors.

Fungal Infection Diagnostics

Lockhart remarked that aspergillosis is a serious problem that often goes unrecognized. Before addressing antifungal resistance, fungal infections must be detected in patients. Autopsy studies indicate that aspergillosis is among the most common missed diagnoses among patients in intensive care units (Winters et al., 2012), underscoring the need for better diagnostics to detect

fungal infections in general and Aspergillus infections specifically. Delays in diagnosing an Aspergillus infection can reduce the likelihood that antifungal treatment will be effective. Prompt diagnosis requires the development of point-of-care tests and affordable tests for use in resource-limited settings. He noted that some countries do not have a single laboratory with the capacity to diagnose fungal infections. Furthermore, the problem of resistant antifungal infections is expected to grow.

Since azole drugs came into use in the 1990s, resistance has been periodically observed in patients on long-term antifungal therapy, with rare cases observed in patients with severe acute illness (CDC, 2021b). Many different mutations have been identified in these infections, which are rarely transmissible. He added that repeated spraying of azole fungicides in agricultural fields leads to repeated selection for Aspergillus resistance, raising the likelihood that resistance rate will increase over time. Thus, the absence of resistance at this current point in time does not signify that resistance will not be detected 5-10 years later.

In contrast to Europe, where up to 20 percent of Aspergillus infections in hospitals are resistant (Fuhren et al., 2015), only a small number of cases have been detected in the United States. Lockhart associated this low case rate with the limited efforts to detect cases. In 2010, the first resistant A. fumigatus isolates with TR34 and TR46 mutations were identified in the United States (Wiederhold et al., 2016). In 2018, CDC published a report of TR34-carrying A. fumigatus isolates found in seven U.S. patients (Beer et al., 2018), leading the agency to include ARAf on the antibiotic resistance watch list (CDC, 2019). Lockhart highlighted a persisting general misconception that a low number of identified U.S. cases signifies that resistant A. fumigatus is not a pressing issue in this country. In reality, the 16 human cases of ARAf with TR34 or TR46 alleles identified in the United States to date likely reflects a small percentage of the true scope of the pathogen, he said.

Antifungal Susceptibility Testing

Lack of laboratory participation and susceptibility testing products are contributing to low levels of antifungal susceptibility testing (AFST) conducted in the United States, Lockhart remarked. In order for a laboratory to perform AFST, it must meet regulations that include demonstration of proficiency demonstration. The College of American Pathologists is the only U.S. group that evaluates commercial proficiency for AFST. Only a tenth of the approximately 4,000 laboratories in the United States participate in the proficiency demonstration. Moreover, the majority of AFST conducted by these 400 laboratories is on yeast, not on mold species such as Aspergillus. Currently, less than a dozen U.S. laboratories perform AFST on molds, with the

majority of isolates being sent to three commercial laboratories located in Minnesota, Utah, and Texas. As a result of the low number and proximity of laboratories, the turnaround time for AFST results is typically 2 weeks. Moreover, only one product is available in the United States for general mold susceptibility testing. This gradient diffusion product is sold commercially, but it is not licensed for mold susceptibility testing. Lockhart remarked that no licensed mold susceptibility test products approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration are available in the United States.

Lockhart stated that many medical professionals do not view this lack of diagnostics as a problem. Two mold-active antifungal classes—azoles and polyenes—are available for patient treatment; thus, a patient who does not respond to one of these drugs can be prescribed the other without waiting for AFST results. He remarked that the available therapies may soon widen to five different classes of mold-active antifungals. Both a DHODH inhibitor and a Gwt1 inhibitor have been developed,1 and tetrazoles have demonstrated some efficacy against ARAf. Particularly in the case of molds, AFST is required to determine the best antifungal therapy available to guide medical professionals in providing the best treatment options to their patients. Thus, expanded AFST capacity would better inform treatment options in a timely fashion.

A commercially available, agar-based screening assay enables detection of azole resistance in A. fumigatus. Lockhart described this product as an effective screening tool, but not a replacement for AFST. He noted that the European Commission for Antifungal Susceptibility Testing recommends the product for screening only, not for resistance testing (Guinea et al., 2019). The assay is being utilized in the United States and has been incorporated into CDC’s Antimicrobial Resistance Laboratory Network (ARLN), a group of seven participating laboratories across the country that screen for bacterial and fungal resistance. A. fumigatus samples can be sent to two of these laboratories, located in Tennessee and Maryland, where they are prescreened for antifungal resistance using agar plates, and broth microdilution can be performed.

Antifungal Resistance Surveillance

The screening conducted by ARLN is the only screening for molds currently taking place in the United States. Lockhart remarked that a problem cannot be solved without understanding it, so learning the extent of antifungal resistance will require more surveillance. ARAf has been identified in the United States (Hurst et al., 2017). While Brewer’s research demonstrated

___________________

1 For additional discussion on development of this new antifungal drug, an inhibitor of the Gwt1 enzyme, see Chapter 4 (page 47).

that ARAf is present in multiple types of crops in various parts of the country (Kang et al., 2022), environmental surveillance efforts to screen for resistance related to specific pathogens have thus far been limited, said Lockhart. He added that close collaboration between agricultural and clinical groups could enable progress toward shared environmental surveillance objectives by combining resources and sharing specimens. Highlighting Brewer’s research, he emphasized that azole-resistant strains indicating cross-resistance to other fungicide classes have been identified in humans (Kang et al., 2020). Similarly, in his own research, Lockhart found that azole-resistant yeast isolates taken from humans in 2010 were resistant to other fungicide classes (Pfaller et al., 2012). He pointed out earlier research that revealed an azole-resistant yeast isolate from the bloodstream is more likely to also be resistant to echinocandins and posited that a “mutator phenotype” could predispose an isolate to be resistant to both echinocandins and azoles.

Communication in the Mycology Research Community

The similarities in antifungal resistance in plants and in humans warrant communication between mycologists who study plants and those who study human fungal infections, said Lockhart. Findings from each of these communities are often published in journals typically only read by that group. Furthermore, most meetings invite members from the plant or human side of mycology, but not from both. However, these scientific communities are focusing on some of the same questions, and communication could foster deeper understanding. He highlighted the Journal of Fungi, which was launched in 2015 to help to address this need for communication by publishing articles on any fungal problem, be it related to human pathogenic fungi, plant pathogenic fungi, or environmental fungi. This journal draws an audience of various mycology specialties, helping readers access new findings they might otherwise be unaware of. However, further efforts are needed to connect the different branches of mycologists. CDC is working to enhance collaboration by engaging in bimonthly meetings with the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency and the U.S. Department of Agriculture. These meetings enable the agencies to identify shared problems and collectively work toward solutions. For example, ipflufenoquin—a DHODH inhibitor—has been approved for use as a fungicide on plants. Meanwhile, another DHODH inhibitor, olorofim, is in phase III clinical trials. No crosstalk has been taking place about the potential for development of resistance, Lockhart remarked. He added that the agricultural and human health communities should be discussing this potential problem now, before resistance emerges in the field. Likewise, communication and collaboration between plant and human health professionals can help generate solutions to the threat of antifungal resistance.

INTERNATIONAL ONE HEALTH APPROACH TO ANTIMICROBIAL RESISTANCE AND PATHOGEN SURVEILLANCE

Pinto Ferreira described international guidance and data platforms for AMR surveillance efforts. He outlined how the platforms address privacy considerations and the expected timeline for implementation.

International Surveillance Guidance

Pinto Ferreira highlighted World Health Organization (WHO) AMR surveillance guidelines for resistance in foodborne bacteria, noting that international guidance avoid being overly prescriptive to allow flexibility for different countries to meet their varying needs (WHO, 2017). He added that this guidance is focused on antibiotics and antibacterial products, with no mention of antifungals as part of the antimicrobial entities to be included in integrated surveillance efforts. Since 2021, FAO and WHO have issued additional guidance documents for the monitoring and surveillance of foodborne AMR (FAO and WHO, 2021, 2022). Given the recent nature of their release, implementation of this guidance is still taking shape. The Republic of Korea has funded an FAO initiative—the AMR Codex Texts (ACT) project—to support the implementation of these international integrated surveillance guidelines at the field level. The ACT project, which is currently being conducted in Bolivia, Cambodia, Columbia, Mongolia, Nepal, and Pakistan, will assess the use and impact of Codex standards related to AMR.2

Antimicrobial Use and Resistance Data Platforms

At the international level, the Tripartite Integrated Surveillance System for Antimicrobial Resistance and Antimicrobial Use (TISSA) platform is currently being developed for displaying AMR-related data. Pinto Ferreira noted that given that the former Tripartite Joint Secretariat on AMR officially became a quadripartite in March 2022, TISSA could potentially face a future name change. The TISSA platform will integrate data from WHO, FAO, and the World Organisation for Animal Health (WOAH). WHO will collect data on humans related to both AMR and antimicrobial use (AMU), as well as some environmental and food data. WOAH (formerly known as OIE until May 2022) will collect antimicrobial use data in animals. Pinto Ferreira remarked that with WOAH providing AMU in animals data and WHO providing data on human AMU and AMR, a data gap remains for AMR in animals and food and AMU in plant production and protection.

___________________

2 More information about the ACT project is available at https://www.fao.org/antimicrobial-resistance/projects/ongoing/project-10/en (accessed August 23, 2022).

To fill this data gap, FAO is simultaneously developing the International FAO Antimicrobial Resistance Monitoring (InFARM) platform, which will link with TISSA. Although concurrently developing two platforms provides challenges, Pinto Ferreira noted that the process has advantages and progress is well under way, with invitations to countries to participate in the platform’s pilot program forthcoming. Obtaining AMR and AMU data is part of FAO’s strategic framework (FAO, 2021b). The Monitoring and Evaluation of the Global Action Plan on Antimicrobial Resistance includes an indicator that countries use the FAO platform to report “levels and trends in sales or use of pesticides for the purpose of controlling bacterial or fungal disease in plant production” (WHO et al., 2019).

Privacy Considerations

The InFARM platform will collect AMR and AMU data from countries and report it via the annual FAO report and the TISSA platform. Pinto Ferreira stated that resistance reporting is highly sensitive, given that it can impact a nation’s trade activity. To help mitigate reservations governments may have about sharing resistance data, InFARM will include three reporting levels. The first level is private, and this data will only be viewable by the country it pertains to. Another level contains public data that are geographically aggregated and reported by region or subregion, rather than by country, to protect each country’s identity. A third level is fully transparent and public, with data identifiable by country. Governments may select from these three data reporting privacy levels. In addition, InFARM will automatically generate reports and graphics to aid countries in visualizing the data being collected.

Data Platform Timeline

Development of the InFARM platform will continue through 2022, with simultaneous collection of AMR data from animals and food. In 2023, a global rollout of InFARM will take place through annual open calls for data. Additionally, FAO will contribute data to TISSA. By 2024, data from additional AMR and AMU surveillance programs on plant production and protection will be included in InFARM. Pinto Ferreira highlighted that FAO is already collecting information regarding agricultural fungicide use reported by countries on a voluntary basis.3 He remarked that data contributions are inconsistent and can vary depending on a country’s economic, human, and technical resources. Furthermore, these data do not include the

___________________

3 Fungicide use data collected by FAO is available at https://www.fao.org/faostat/en/#search/fungicides (accessed August 23, 2022).

purpose for fungicide use. Although this database does not offer granularity, its data are public and can be downloaded and printed. He described the current website as a starting point for the development of the new platforms that will offer greater functionality.

ONE HEALTH ASPECTS OF CIRCULARITY

Zwaan provided an overview of the One Health Aspects of Circularity project. The use of chemicals to combat bacteria, insects, or fungi ultimately faces the development of resistance in the targeted population of organisms. He remarked that good stewardship and prudent use of these compounds are first and foremost in addressing potential emerging health risks from different organisms. In the Netherlands and in other countries in Europe and around the world, current agricultural practices involve high input of chemicals, wasted resources, and a fairly linear process. Creating a more circular system in which plant waste is composted and used in future crop cycles has benefits, but current chemical usage within this system poses risks.

Zwaan described this type of circular system within the context of the flower bulb industry. Azoles are used to combat fungal plant pathogens; the fungicide residue then accumulates in plant waste. A. fumigatus plays a role in the plant waste composting process, but the azole residue in the compost pile exerts selective pressure for the fungus to develop resistance in order to survive. Aspergillus produces plentiful spores that can cause disease when inhaled by humans. The similarities in the azoles used in agriculture and in medicine lead to treatment challenges because A. fumigatus with acquired resistance in the environment may not respond to medical therapy. Zwaan stated that combining the use of chemicals and microbes within the process of circular agriculture poses risk for the emergence of One Health problems.

Agricultural Antifungal Resistance

Multiple factors relevant to the development of AMR should be considered in research, including resistance mechanisms, ecological settings, biology of the species, and the nature of the selection pressure, Zwaan explained. The One Health Aspects of Circularity project is currently at its midway point. The project initially focused on the bulb industry in the Netherlands due to the established knowledge base about the growth of ARAf in bulb plant waste. Using the bulb industry as a case study, the project aims to identify (1) other sectors in which plant waste contributes to the development of resistance and (2) interventions to prevent the growth and spread of azole-resistant A. fumigatus. Zwaan highlighted recent research funded by the Netherlands Ministry of Health to

investigate potential resistance hotspots. A. fumigatus spores resistant to both itraconazole, a medical therapy, and tebuconazole, an agricultural product, were found in wood chips, strawberry, onion, potato, and other crops. A subset of samples was tested for resistance mechanism identification, and TR34 and TR46 mutations in combination with point mutations were detected similar to those reported in clinical azole-resistant isolates. These findings suggest that the issue of resistance extends beyond the bulb industry and the Netherlands, warranting collaborative efforts from multiple nations.

In an effort to better understand how resistant spores spread, Zwaan conducted air sampling around plant waste heaps. A machine that actively samples the air was used to collect samples before and after the turning of waste heaps. No spores were captured in samples taken before the heaps were turned. During the process of being turned, the heaps released profusive amounts of spores. After the turning, the spore count returned to very low levels. Zwaan stated that this finding indicates that avoiding disturbance to waste heaps could reduce the risk of ARAf spores being released into the air. He added that the concept of circularity offers benefits in reusing waste material to return nutrients to the soil, and different management techniques could decrease associated risks.

Noting inspiration from the community science research conducted by Jennifer Shelton and Matthew Fisher at Imperial College London, Zwaan described air sampling surveillance efforts his team is developing. They created a sampling method in which a PCR seal (i.e., a thin film with an adhesive side) is exposed to the air for a determined length of time at a sampling site, then collected, trimmed to fit inside a petri dish, covered with agar, and incubated to recover fungal isolates that grow from spores collected on the film. Zwaan noted they are in the process of determining the best approach to conducting systematic community science sampling throughout the Netherlands. Data on the presence and location of resistant spores will contribute to understanding their origin.

Linking the Environment to the Clinic

Zwaan emphasized that learning how long it takes for an ARAf spore to travel from its origin to a potential human host could contribute to understanding how to disrupt the spore’s route. He and colleagues have investigated samples collected from flower bulb waste heaps in three different locations from 2016–2019 that include both susceptible and resistant fungal isolates. They compared these with clinical samples collected from three medical facilities in Amsterdam during roughly the same time period. Zwaan noted the similarities in the genotypes identified from the clinical and environmental samples, suggesting a link between the fungal isolates

recovered in these two settings. Efforts to identify specific links between patients and environmental isolates are ongoing.

Research Considerations

Zwaan summarized that resistance hotspots exist outside of the flower bulb sector, and organic waste treatment affects the growth of A. fumigatus. He added that hotspots will continue to be a focus in understanding how resistance develops and pointed out that little is known about the ecological niches of A. fumigatus in settings where it has no contact with azoles and other chemicals. The community science approach could potentially contribute data to help answer this question. Whole genome sequencing analysis can then be used to explore whether there is a causal link between resistance in the environment and in clinical settings. Zwaan posited that the ability to prevent resistance from developing seems unlikely in light of the discovery that resistant A. fumigatus spores appear to be ubiquitously present. Therefore, his current research target is the prevention of transmission. Moreover, he believed that the necessary development of new drug treatments for fungal diseases in humans should be coupled with efforts to ensure that new chemicals used in medicine are not also used in agriculture.

DISCUSSION

Potential Interventions and Policy Changes

McKenna asked the participants to provide interventions or policy considerations they view as priorities in addressing antifungal resistance. Verweij replied that, like Zwaan, he too has come to the realization that preventing resistance from emerging is unlikely. Numerous experts have indicated that the same modes of action should not be used in the environment and in patients, and yet this practice continues. Therefore, efforts to identify hotspots and apply interventions to turn them into coldspots are needed to prevent transmission from occurring. Pinto Ferreira stated that the ideal scenario would be different sectors avoiding use of the same molecules; however, given that the ideal does not always transpire, collaborative surveillance data collection should be a focus. Varying recommendations from the human, animal, and plant perspectives can be difficult for governmental stakeholders to navigate. He remarked that collaboratively generating integrated One Health policy recommendations for managing molecules would facilitate policymaking at the country level.

Brewer remarked that an integrated disease management approach can minimize the overall amount of fungicide in the environment. This approach includes multiple strategies, such as using fungicides for disease

control but not for plant growth promotion. Additionally, crops can be bred for resistance to decrease reliance on chemical inputs. Lockhart commented that integrated crop management has not been a focus for addressing azole usage, and communication is needed between the clinical and agricultural sectors to encourage the prioritization of these approaches. Food security and disease management are equally important to public health, and threats to these areas are global problems requiring collaborative problem-solving, said Lockhart. Zwaan replied that the Dutch government is considering control measure protocols to address resistance, because having mechanisms in place to enforce protocols can be more impactful than mere recommendations. Stewardship practices to utilize alternative approaches and limit chemical use to specific circumstances can also be beneficial. Zwaan described how the Dutch government formerly ran a knowledge center that advised farmers on issues such as chemical use, providing them with an information source other than the companies selling the products and systems. Such consultation services, stewardship practices, and approaches to plant waste could be helpful in decreasing the spread of resistant fungi.

Resistance and Fitness Cost

Kent Kester, vice chair of the Forum on Microbial Threats, asked about the fitness of resistant environmental isolates. Often, antibiotic-resistant bacteria are not as fit as typical strains, and when antibiotics are withdrawn and selective pressure is reduced, the wild-type or susceptible strains repopulate. He questioned whether a similar phenomenon occurs in antifungal resistant organisms. Brewer replied that much is known about the fitness of plant pathogenic fungi resistant to antifungals. For instance, resistance to benzimidazoles or QoIs generally does not carry a fitness cost. Additionally, benzimidazole-resistant isolates from pecan pathogens have been found in locations where benzimidazoles are no longer used. A fitness cost has been seen in relation to triazole resistance. She remarked that she is currently investigating whether resistance to triazoles carries a fitness cost for A. fumigatus under different environmental conditions. Her team has considered whether a strategy of reducing azole use could have results similar to those Kester described in bacteria. However, multi-fungicide resistance may enable continued selection for azole-resistant isolates in the presence of other single site fungicides. Brewer added that this is yet to be determined, and that although current studies do not indicate fitness costs in isolates from humans or in mouse models, additional research is needed to determine fitness costs in various environmental settings. Zwaan remarked that he has found little evidence of fitness cost related to resistance, which may be related to compensatory mutations in the strains. He noted that

the fungi being investigated are in a food-rich environment that could prevent fitness cost. Researching fungi in stressful conditions is needed to determine whether this factors into fitness cost. His group is also examining whether A. fumigatus is more susceptible to pressure from competing fungi or bacteria.

Farmworker Safety

McKenna asked about farmworker safety issues related to resistant fungi. Verweij replied that it is not yet known whether a worker in a field is at a higher risk of developing a resistant infection than the general population. Researching the occupations or residence locations of patients who develop resistant infections is a potential method of assessing associated risk level, but privacy issues complicate this type of research.

Food Security Considerations

Given that agricultural triazoles provide high yield stabilization and food security, McKenna asked about the balance in preserving food security while monitoring resistance. Brewer replied that fungi can cause 20 percent yield losses in crop production, and therefore managing fungal diseases is important to food security. Furthermore, azoles can contribute to food safety by reducing mycotoxin production in wheat with Fusarium head blight, as noted by Pierce Paul in Chapter 5. Reducing the input of fungicides and utilizing integrated pest management are approaches to limiting use of these chemicals to situations where they are necessary to save crops, thus achieving balance between clinical issues and plant pathogen control. Brewer added that overuse of azoles can also lead to the development of resistance in plant pathogens. Awareness efforts are needed to inform growers that minimal, effective triazole practices can avoid resistance in plant pathogenic fungi as well as helping to reduce human pathogen risk. Pinto Ferreira noted that in the past, discussion of ending the use of growth promotion in animal production featured disputes that growth promotion was required to generate adequate animal protein. He remarked that economic data indicate that producing adequate animal protein is possible in the absence of growth promotion. He questioned whether economic data are available to indicate what effect ending azole usage in plant production could have on food security.

Addressing Potential Overlapping Use in Agriculture and Medicine

McKenna asked how the potential use of DHODH inhibitors in medicine and in agriculture should be approached to avoid repeating more resistant fungal pathogens. Verweij replied that risk assessment is the first step.

This involves determining whether the agricultural and clinical targets are the same, the binding affinity of the chemical compound to each target, and the spectrum of activity against A. fumigatus. Similar molecular structure of the targets will pose a high risk for resistance selection, thus the level of similarity needs to be determined. Additionally, the entrance of a new class into the fungicide arena increases the likelihood that other new compounds in this class will emerge, each of these may have a closer molecular structure to that of the human medication olorofim. The risk of such developments needs to be investigated, said Verweij. Zwaan added that microbes tend to eventually overcome the chemical. This dynamic drives the development of new chemicals for applications in agriculture and other fields. Lockhart added that this situation provides an opportunity for the fields of agriculture and medicine to collaboratively create a surveillance system and share samples to detect any resistance before it takes hold. Brewer remarked that ipflufenoquin will soon be used on crops in spite of the possibility that it shares the same target with olorofim. She suggested that, moving forward, a system should be put into place to avoid approval of chemicals that will be used in both agriculture and medicine. A system could be implemented for investigating the potential for cross-resistance in new compounds. When cross-resistance is likely, compounds could be regulated for use in food production, but not for ornamentals and landscaping.