The Role of Plant Agricultural Practices on Development of Antimicrobial Resistant Fungi Affecting Human Health: Proceedings of a Workshop Series (2023)

Chapter: 9 Antifungal Drug Development and Stewardship in Health Care

9

Antifungal Drug Development and Stewardship in Health Care

The eighth session of the workshop focused on the role of resistance in driving a continued need for new antifungal drugs featuring novel modes of action and challenges inherent in antifungal discovery and development. Maryn McKenna, senior writer at WIRED and Senior Fellow in Health Narrative and Communication at the Emory University Center for the Study of Human Health, moderated the session. David Andes, William A. Craig Professor and chief of the Division of Infectious Diseases and Medical Microbiology and Immunology at the University of Wisconsin, provided an overview of the current antifungal armamentarium, its gaps, and the status of development efforts under way for new antifungal treatments. John Rex, chief medical officer of F2G Ltd, discussed the challenges in developing new antifungal drugs—particularly in terms of the time and expense involved—and incentive funding structures to encourage antimicrobial development activity.

NEW ANTIFUNGAL DRUGS IN DEVELOPMENT

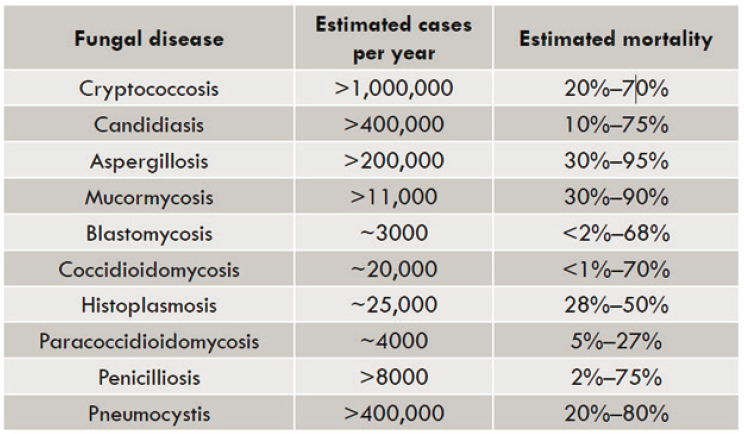

Andes discussed currently approved antifungals, gaps in the antifungal armamentarium, progress toward discovery and development of new antifungals, and the status of research on new antifungal treatments moving toward clinical use. Over 1 billion fungal infections occur annually around the world, resulting in 1.6 million deaths (Pianalto and Alspaugh, 2016). The fungal diseases with the greatest number of estimated cases per year worldwide are cryptococcosis, candidiasis, pneumocystis, and aspergillosis (see Figure 9-1).

SOURCE: Andes presentation, June 27, 2022; adapted from (Pianalto and Alspaugh, 2016).

Current Antifungal Therapies

The current armamentarium of antifungals to treat invasive fungal infections is limited to three classes: polyenes, triazoles, and echinocandins. Andes explained that these three classes primarily target two sites in the fungus. Polyenes and triazoles both target ergosterol: polyenes bind and sequester ergosterol, while triazoles inhibit a step in its synthesis. Echinocandins comprise the most recent mechanistic class to enter clinical use, and these drugs inhibit the production of a fungal-specific component of the cell wall, 1,3-ß-D-glucane.

Andes emphasized the difficulty in identifying compounds that kill fungi without hurting mammalian hosts. Polyenes target ergosterol, the primary sterol in fungi, which is structurally similar to cholesterol, the primary sterol in humans. This similarity can cause off-target toxicities including renal insufficiency that can become life-threatening. Likewise, triazoles bind to CYP51A, an enzyme that is structurally similar to mammalian metabolic enzymes. Triazoles can cause off-target toxicities, which can result in limited treatment options and drug interactions in hospital patients.

Antifungal Therapy Gaps

The emergence of resistance among Candida species is concerning, said Andes, given the high mortality rates associated with triazole-resistant invasive candidiasis and aspergillosis (Alexander et al., 2013; Wiederhold and Verweij, 2020). Moreover, mold pathogens are emerging that feature intrinsic resistance to the current treatments, including species of Fusarium, Scedosporium, and Mucorales. The current antifungal armamentarium has pharmacokinetic liabilities. Many of the fungi that affect human health can be disseminated to different parts of the body. Andes remarked that fungal infections commonly disseminate to the central nervous system (CNS) or inside the eye, and very few antifungals can penetrate those infection sites at therapeutic levels. Fluconazole can accumulate in the CNS or eye at 80 percent penetration, flucytosine can achieve 75 percent, and voriconazole can reach 60 percent (Nett and Andes, 2016). All other currently available antifungals have CNS or eye accumulation rates below 1 percent.

Antifungal Discovery and Development

All antifungals have shortcomings that the field of antifungal discovery is working to overcome, said Andes. For instance, the azoles have toxicity and drug interaction considerations. Echinocandins are only available in intravenous delivery formulations. Antifungals can have limited pharmacokinetic distribution and resistant pathogens are emerging. He remarked that the holy grail in antifungal discovery and development is a novel mechanism of action that avoids cross-resistance to existing agents. Short of developing novel targets, repurposing and medicinal chemistry approaches can be used (Pianalto and Alspaugh, 2016). Repurposing involves exploring drugs that are already approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) or European Medicines Agency for antifungal activity. Medicinal chemistry involves making improvements to existing drug classes.

Antifungals Developed Via Medicinal Chemistry

In the medicinal chemistry approach, a new drug’s target is similar to previous drugs, but it has improved features. Oteseconazole, an azole antifungal approved by the FDA in April 2022, is one of several recently developed antifungals. This drug is the first of the tetrazole class, so named for the four nitrogen atoms in the compound, in comparison to the three nitrogen atoms in triazoles. This new chemistry affects the compounds’ metal binding group that interacts with the CYP51 enzyme (Warrilow et al., 2014). This alteration improves drug potency against fungal pathogens and improves the stability of the molecules, making them less likely to

be metabolized by human CYP enzymes. This lengthens half-life of the drug and results in fewer off-target effects, both in terms of direct toxicities and drug interactions. In comparison to older azoles, the change of chemistry in oteseconazole causes a significant effect on the ratio of the binding constant to Candida drug targets relative to the human drug target ortholog (Warrilow et al., 2014). Clotrimazole and itraconazole demonstrated binding rates of less than 5, indicating a relatively low affinity to bind to Candida over the human CYP protein. The ratios were higher for voriconazole and fluconazole—two existing azoles used in systemic therapy—at 229 and 543, respectively. This signifies that these drugs are far more likely to bind to Candida than to human CYP. Oteseconazole had a ratio greater than 2,000, indicating a far greater affinity for the fungal target relative to the mammalian target. Andes explained that this results in oteseconazole achieving a much greater effect on Candida than triazoles used at similar concentrations.

Based on the results of two phase III treatment studies (NIH, 2021a), oteseconazole was recently approved by the FDA for the treatment of vulvovaginal candidiasis. The drug has been tested in phase II trials against onychomycosis (NIH, 2020), a fungal infection of the toenails, and tinea pedis (NIH, 2018), commonly referred to as “athlete’s foot.” The results of these treatment studies demonstrate a superiority over the standard of care—i.e., fluconazole—with fewer drug interactions and toxicity. Andes remarked that these findings hold promise for future generations of drugs developed using this technology.

Novel Modes of Action

Andes emphasized that a number of compounds featuring novel modes of action are in clinical development. Fosmanogepix is a compound that inhibits Gwt1, a glycosyl-phosphatidylinositol (GPI) acyl-transfer protein. Inhibition of this enzyme results in changes in the cell wall integrity and cell death. Fosmanogepix has little to no activity against a human ortholog. In the context of current antifungal gaps, this compound has an extremely broad spectrum of activity against yeast and mold, including triazole-resistant Aspergillus. Andes added that its pharmacologic properties are favorable. Both oral and intravenous formulations of fosmanogepix have been developed, with high oral absorption and bioavailability greater than 90 percent. He emphasized that fungal infections often require months of therapy, which poses challenges for intravenous delivery. Pharmacokinetically, fosmanogepix achieves penetration into the CNS and eye and holds promise of effective concentrations for these sites of dissemination. A completed phase II trial for fosmanogepix against invasive candidiasis demonstrated efficacy and did not identify a concerning safety signal, suggesting

further development is warranted (NIH, 2021b). Two phase II trials for fosmanogepix are ongoing, one for C. auris (NIH, 2022a) and another against aspergillosis and rare molds (NIH, 2022b). An expanded access study for the treatment of Fusarium is also under way. Andes emphasized that fosmanogepix addresses multiple antifungal gaps, including (1) efficacy against multidrug-resistant organisms, (2) a novel mechanism of action, (3) penetration into the CNS, (4) formulations allowing both intravenous and oral administration, and (5) no significant toxicity signal indicated thus far.

Olorofim also has a novel target, being the first compound from the orotamide class, Andes explained. This class inhibits dihydroorotate dehydrogenase (DHODH), causing depletion of pyrimidine and subsequent inhibition of DNA and RNA synthesis. DHODH has a human ortholog for which this compound has minimal binding (Oliver et al., 2016). Olorofim has a broad spectrum of activity, particularly against molds and endemic fungi. He noted the drug has not shown appreciable activity against Candida, Cryptococcus, or Zygomycetes. Based on its favorable pharmacologic features, olorofim has both intravenous and oral formulations, with oral bioavailability of 45–82 percent. Furthermore, the compound achieves CNS penetration. Olorofim does appear to be a substrate for CYP3A4 metabolism, which poses a risk for drug–drug interactions. A phase II trial is under way for patients with refractory fungal infections for which no other treatment options exist (NIH, 2022c). Andes stated that presentation from the results of this trial thus far have been promising. A phase III trial is also being conducted against Aspergillus and rare molds (NIH, 2022d). He remarked that, like fosmanogepix, olorofim appears to address several antifungal gaps, including a novel mode of action, spectrum of activity, safety, and pharmacokinetics.

Several additional drugs featuring unique mechanisms of action are in early clinical or preclinical studies. Andes highlighted the challenges in antifungal development in noting that three of the five drug studies in early clinical trials have been stalled. The reasons for the stalled status range from the science of the mechanism of action to treatment failure to finances. Thus, despite the appearance of safety and efficacy of these compounds during preclinical studies, they will not be moving forward within the near future. Currently, seven additional antifungals with novel modes of action are in the preclinical phases. These drugs target multidrug-resistant pathogens and are demonstrating safety and efficacy in preclinical models. Andes noted that at this early research phase, it remains unclear whether any of these compounds will eventually be used to treat patients. However, the number of novel targets being developed holds promise. He added that One Health stewardship is important for the management of new antifungal options.

ANTIFUNGAL RESEARCH AND DEVELOPMENT: CHALLENGES AND NEED FOR INCENTIVES

Rex discussed the challenges in developing new antifungal drugs, the time and expense involved in this process, and the value of having effective treatments available in the context of emerging resistance to current therapies. He highlighted financial incentives that could stimulate increased antimicrobial development activity.

Challenges in Antifungal Development

Inventing and delivering a new drug is difficult, slow, and costly, said Rex. The challenging nature of discovering and developing antifungals is reflected in the low number of novel mechanisms on the market and the limited antifungals available in oral formulation. Furthermore, antifungal resistance is increasing and spreading worldwide, affecting both plants and humans (Fisher et al., 2018). Rex explained that finding fungal targets is not difficult and numerous fungal genomes are fully sequenced. Although methods of killing fungi are readily available, identifying drugs that kill fungi and that are well tolerated in the human body is a formidable process. Prospective drugs can fail due to physical properties, pharmacology, and tolerability. The process for discovering a new molecule is lengthy, and bringing a molecule from discovery through development requires years of research. Rex noted that the compound for olorofim—a drug he is involved in developing—was discovered in 2010 and is still being developed 12 years later.

The time and effort required to develop new antifungal and antibiotic drugs drive up the expense of this process. The average research and development cost to bring a human medicine to approval is $1.3 billion (Wouters et al., 2020). Rex explained that this figure encompasses a process in which numerous compounds do not proceed to approval but contribute to the insights needed to generate an effective drug that is ultimately approved. Drug development can last a decade, with costs incurred throughout that timeframe. Once a drug is approved, funding is required to finance post-approval commitments, operational costs for manufacturing the drug, and surveillance and pharmacovigilance activities. During the first 10 years after approval, these costs average $350 million. Thus, costs to develop a drug and fund the first decade post-market can total $1.7 billion per molecule, but usage-based income will not recover these costs (Drakeman, 2014; Rex and Krause, 2021). Rex remarked that these costs cannot be substantially decreased, given the absence of discounts and regulatory shortcuts regardless of company size, for-profit or non-profit status, or the degree of novelty involved. Thus, each antifungal is incredibly valuable, the release of new

antifungal drugs is rare, and the importance of maintaining the efficacy of existing drugs is considerable, he added.

Evolving Payer Paradigms

Rex described the current economic model for antimicrobials as “broken.” When a new antibiotic is approved, its use is delayed and deferred in an effort to preserve it. He emphasized that such measures constitute necessary stewardship to avoid decreasing a new drug’s efficacy while existing drugs can still be used. However, the innovator faces tremendous financial loss—and in some cases bankruptcy and business closure—from the current pay-per-use model that only reimburses a portion of the value (Carr and Stringer, 2019). Rex drew an analogy between antimicrobials and fire extinguishers. A person might not regard a fire extinguisher stored in their home or office building as being used. Rex argued that these fire extinguishers are in fact being used in that they are immediately available in the event a fire breaks out. Similarly, an infection can emerge quickly and, if untreated, spread to other susceptible individuals. Therefore, the availability of an effective antimicrobial treatment holds value regardless of whether the drug is currently being administered to humans. This value is captured in the acronym STEDI: spectrum, transmission, enablement, diversity, and insurance. Rex exemplified the value of preventing transmission with a scenario in which a person contracts a serious infection from a highly resistant microbe. The availability of an effective treatment enables the microbe to be killed before it is passed to other people. Those prospective microbe hosts spared from being infected have benefited from the treatment, despite that they may never become aware that the microbe posed a threat to them.

Incentive models can encourage the development of new antifungals for inventory against future microbial threats.1 Incentives can be characterized as “push” and “pull” models. “Push” incentives include grants and grant coordination. Rex noted that a variety of groups—such as Combating Antibiotic-Resistant Bacteria (CARB-X), Replenishing and Enabling the Pipeline for Anti-Infective Resistance Impact Fund (REPAIR), the Biomedical Advanced Research and Development Authority (BARDA), and the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases—have coalesced to fund academic groups and small companies to develop new antibacterial and antifungal products.2 “Pull” incentives disrupt the current pay-per-use

___________________

1 More information about the rationale for economic incentives for the development of antimicrobials is available at http://drive-ab.eu, https://amr-review.org, and https://amr.solutions/incentives (accessed August 27, 2022).

2 More information about CARB-X is available at https://carb-x.org. More information about the REPAIR Impact Fund is available at https://www.repair-impact-fund.com (accessed August 27, 2022).

model. Rather than paying innovators for drug usage, and defining usage as the administration of a drug into a human, the pull model offers market entry reward (MER). The MER is a defined sum of money that is paid over time to the creator of a new antimicrobial independent of the volume of use. Rex noted that the United Kingdom recently announced plans to buy two antibacterial agents for £10 million per year for 10 years, for a total of £100 million paid to the innovator (NHS, 2022; NICE, 2022; Outterson and Rex, 2022). Irrespective of the amount of drug used, the innovator will be compensated for developing needed drugs. Stewardship and access requirements can be added to MER agreements to stipulate that the company should not actively market the compound. Thus, pull incentives can create alignment of all parties on stewardship, said Rex. He reflected that new antifungals for human use (1) will be limited due to the difficulty in creating them, (2) will be expensive to discover and develop, (3) need to be preserved via careful stewardship, and (4) can be encouraged via a different payer model.

DISCUSSION

Strategies to Avoid Antifungal Dual Use

McKenna asked about action steps or policy changes that can be taken to address problems associated with resistant fungal infections. Rex commented that a shift has occurred in the animal agricultural industry in response to concerns about the use of antibacterial compounds. Approaches that avoid overlap with human clinical products are being taken, including changing animal husbandry practices. Rex said that substantial use of an antifungal agent in plant or animal agriculture that shares the same class as a clinical product would be unfortunate. Andes noted the inevitability that some antifungals will fail because of toxicity or pharmacologic features. He remarked that failed clinical antifungal products could potentially be used in nonhuman health circumstances in order to avoid overlapping usage. Tim Widmer, national program leader for plant health at the U.S. Department of Agriculture Agricultural Research Service, asked whether developers of agricultural and plant products have access to antimicrobial products that have failed clinical trials in humans—i.e., whether a pipeline is established for this purpose or whether intellectual property rights and the exorbitant cost of drug development pose barriers to data sharing between companies. Andes replied that he is not aware of any systematic approach to sharing these data, and that methods to increase communication between the agricultural and human health are needed. Rex remarked that topical agents will not become systemic human medicinal products; this pathway could offer advantages in agricultural applications.

Communication Structures to Reduce Resistance Potential

Given that the FDA has a framework for assessing the potential of plant and animal agricultural antibiotic use to affect resistance in humans, McKenna asked whether a similar framework could be created for fungicides. Rex remarked that this issue is structural in nature, so it should be feasible to overcome the structural issue and set up such a framework. He added that the pragmatic approaches used to eliminate antibiotics used in animal agriculture are an example of success in changing processes. Recalling a visit to a facility applying these animal practices, Rex said that the workers preferred the new methods to the former status quo and that full implementation took place over a decade. McKenna asked how communication systems targeted to either health care or the environmental and agricultural sectors could be addressed to facilitate communication between these sectors. Andes replied that this workshop is a method of shifting those communications patterns. Rex stated that he sat on the U.S. Presidential Advisory Council for Antimicrobial Resistance, which was comprised of experts from both agriculture and medicine. Councils such as that and workshops such as this shift siloed communication patterns.

Lessons from Antibacterial Research

Jeff LeJeune, food safety officer in the Food Systems and Food Safety Division of the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, asked about whether phages are a potential avenue for treatment against fungal infections. Rex replied that he cannot speak to phages for fungal pathogens, but there are phages that clearly do kill bacteria. However, they tend to be highly specific in their target bacteria and require substantial effort to develop as therapeutics, he added.

McKenna asked whether the funding models in place for antibacterial development apply to antifungal development. Andes remarked that, until recently, antifungal research was not eligible for many funding programs. Rex stated that antifungal drugs need to be developed for problems anticipated to occur 10–15 years into the future. These compounds lose efficacy over time, thus new products need to be available to take their place once they are no longer effective. He emphasized that in situations where an effective tool against the most common varieties of fungal pathogens is already available, it is challenging to obtain approval for a new product that treats common varieties as well as less frequent types of infections. Moreover, successfully demonstrating superiority in efficacy trials is rare, especially given that serious infections require aggressive dosing. In the United States, a pull incentive to develop antimicrobial innovations established by the PASTEUR

Act is currently being considered by Congress.3 Although the bill’s first iteration did not include antifungals, advocacy efforts achieved inclusion of these products in the current version, which is expected to be voted on by the end of 2022. Rex stated that 2–4 new drugs are needed each decade to stay ahead of the resistance that continues to emerge against products after they are in use for several years.

___________________

3 PASTEUR Act of 2021, HR 3932, 117th Congress, 1st session (June 16, 2021).